ABSTRACT

A great interest was devoted to the rise of the Industry 4.0 production model and its impacts. Far less is known about the so-called digital service economy, a multifaceted phenomenon made of a sprawling range of businesses based on digital platforms and redesigning the boundaries of manufacturing towards services. The net socio-economic effects of the digital service economy at the local level are not yet known and difficult to be measured unless the different value creation models it entails are not identified. This paper fills such a gap by separating out, on conceptual grounds, specific value creation models within the digital service economy, each presenting distinctive growth opportunities and threats, and, empirically, measuring their spatial diffusion and coexistence in each European region. The taxonomy of European regions obtained serves future research purposes to assess the expected heterogeneous regional socio-economic effects of the digital service economy and its value creation models.

JEL:

1. Introduction

Radical and complex transformations are taking place in contemporary economies and society because of the exponential evolution and global adoption of the new technologies, such as artificial intelligence, smart automation, and Internet of things just to quote some of them. A new technological era has begun, and drastic structural changes are under way in businesses and society.

These statements are supported not only by scholarly work but also by influential commentators. Individuals’ daily life is, in fact, exposed to revolutionary changes in working practices, entertainment experiences, lifestyles in general, up to the ways of doing business. Optimism about the growth and productivity potential offered by 4.0 technologies diffusion is widespread even if the risks of possible social threats cannot be ignored and are increasingly highlighted (Frey and Osborne Citation2017; Schwab Citation2017; Brynjolfsson and A Citation2014; McAfee and Brynjolfsson Citation2017; Rullani and Rullani Citation2018).

The role of the new technologies in the transformation of industrial production processes, known as Industry 4.0, has received great attention in the literature also from a spatial perspective and has highlighted the important consequences of the increasing automation and digitalisation of the manufacturing environment (Acemoglu and Restrepo Citation2020; Büchi, Cugno, and Castagnoli Citation2020). Digitalisation, in fact, enriches value chains and the exchange of inputs with business partners, suppliers and customers (Lasi et al. Citation2014). The integration of physical objects in the information network represents a deep revolution in the traditional industry and pushes towards a paradigm shift in production processes and business models, setting a new level of development and management for organisations (Paiva Santos, Charrua-Santos, and Lima Citation2018; Ciffolilli and Muscio Citation2018). The progressive evolution and embeddedness of digitalisation within firms also led to a substantial transformation of the products themselves that become smart, intelligent and connected. As highlighted in Porter and Heppelmann (Citation2015), the evolution of products into technologically enabled smart devices has radically changed internal and external firms’ logics and structures. In fact, besides being fundamentally different and digitally advanced products, they require a whole new supporting technology infrastructure. Industries are therefore forced to, and at the same time they can take benefit from, profound redefinition of production cycles, marketing and sales strategies, greater customer orientation, changes in employee roles and skills, and availability of data. Products have in fact become complex systems that incorporate hardware, sensors, software and connectivity leading to modified industry structures and generating new ways of competing. As put forward by Porter and Heppelmann (Citation2014),

smart, connected products are changing how value is created for customers, how companies compete and the boundaries of competition itself […]. They will affect the trajectory of the overall economy, giving rise to the next era of IT-driven productivity growth for companies, their customers, and the global economy […]. (p.23)

Digital technologies represent a source of disruption within the manufacturing sector as they enable new and altered consumer behaviours and expectations, different competitive scenarios and especially greater availability of data (Vial Citation2019). On the one hand, the very same idea behind the concept of Industry 4.0 relies on the integration of digital technologies to add value to both the product and the product lifecycle opening up new business potentials and opportunities (Hofmann and Rüsch Citation2017; Frank, Dalenogare, and Ayala Citation2019; Wang et al. Citation2016); on the other hand, the rapid and relentless technological progress has set up new competition challenges. Companies have therefore been forced and stimulated to put in place transformative strategies to cope with these trends (e.g. changes in organisational structure and culture, use of digital distribution and sales channels; see Vial Citation2019 for a detailed review). Among these transformative actions, the creation of new value propositions stands out. In fact, enabled by digital technologies, companies started to sell physical products together with services as integral part of their value proposition with the dual purpose of satisfying consumers’ needs with innovative and customised solutions and gathering data on the products and services themselves (Porter and Heppelmann Citation2014; Barrett et al. Citation2015; Wulf, Mettler, and Brenner Citation2017).

In particular, the relevance of digital technologies in the renewal and transformation of manufacturing activities has been soon acknowledged in the literature on servitisation. Scholars in this field have richly documented the shift in manufacturing business models towards the provision of bundles of product and (digital) services turning into a symbiotic recoupling between manufacturing and service activities (Rabetino et al. Citation2021; Gebauer et al. Citation2021; Kohtamäki et al. Citation2021a). Importantly, digitalisation enables expanding the range of hybrid/integrated offerings (products and services) towards digital offerings. Since customers increasingly show preferences for receiving only the value inherently offered by the product use and consuming it as a service, this strategy looks more and more attractive (Cusumano, Kahl, and Suarez Citation2015; Tukker Citation2004). As highlighted in Opazo-Basáez et al. (Citation2022), the servitisation phenomenon consisting in a progressively increasing offer of complementary services together with physical products answers to specific competitive needs and has gradually become more technology-intensive and digitalised. Companies have modified and adapted their business models accordingly, moving towards more customised solutions and digitally driven service orientation. It can be argued that companies have started to sell not only products but integrated, and digitally based, solutions. As Storbacka (Citation2011) points out, the concept of integrated solution refers to the integration of goods, service and knowledge into unique combinations that answer specific customers’ needs. New challenges open up for companies as servitisation requires new capabilities, expertise, and management practices (Brax and Jonsson Citation2009; Cornet et al. Citation2000). Furthermore, as smart and connected products and solutions interact with product-service-software systems of other firms, digital servitisation requires collaboration across firms’ boundaries and the creation of smart ecosystems (Kohtamäki et al. Citation2019; Bustinza et al. Citation2015).

The servitisation literature is rich and well developed, conversely, far less is known about what we define in this work as the digital service economy, an economy encompassing a sprawling range of businesses, enabled by digital platforms, redesigning the boundaries of products towards services. The idea of digital service economy differs from and enriches the concepts of service economy proposed by Buera and Kaboski (Citation2012) as well as alternative labels introduced in the literature and in the policy debate to describe the application of digital technologies in products and services creation and provision, such as the digital economy (OECD Citation2020; EC Citation2021).Footnote1 In our understanding, in fact, the digital service economy does not simply refer to the expansion of service sectors over manufacturing in terms of both value added and employment, as the service economy would imply (Buera and Kaboski Citation2012). Nor it simply relates to the deployment of digital technologies in the provision of products and services through on-line channels, as implicit in the notion of digital economy. The digital service economy, instead, refers to the idea that the full-scale digitalisation trend characterising modern economies and society is redesigning the boundaries between product and services. The servitisation literature has amply highlighted the increasing complementarity, integration and bundling of products and services, giving rise to the offer of products as a service and integrated solutions. The capacity to target and to satisfy customer needs and requirements, largely amplified by the possibilities opened by data analytics, is in fact a distinctive trait of digital servitisation business models centred on customised oriented solution providers (Kohtamäki et al. Citation2019). The digital service economy stretches further the boundaries between products and services, with the latter not only complementing and/or enriching the former (as proposed in the case of servitisation and its literature) but also, and increasingly, substituting them, with dramatic consequences for competitive dynamics and value creation and distribution models. The dematerialisation of the product (e.g. a CD) into its own content (e.g. music) allows the last one to be sold on-line in the form of a digital service (e.g. a subscription to Spotify), destroying the market for the original product in favour of the service.

This encompassing view on the complex relationship between products and services admittedly finds its origins in the vast literature on servitisation and the reflections on product-service (innovation) systems (see for reviews Rabetino et al. Citation2021; Baines et al. Citation2017 on servitisation; Baines et al. (Citation2007) on product-service systems). Over time, however, additional digital market transactions enabled by the operation of digital platforms have come to the fore, including phenomena like the sharing economy (e.g. BlaBlaCar), the on-line service economy (e.g. Uber) up to the digital content economy (e.g. Spotify and Netflix). All these forms go under the notion of digital service economy. In short, the digital service economy can be defined as an economy characterised by the redesign of the boundaries between products and services in favour of the latter, enabled by the increasing dematerialisation or unbundling of resources and products (e.g. a car) from the service they may provide (e.g. a ride). Consequently, the digital service economy expands the opportunities and choices of consumers to get a product and/or a service. For example, if a person needs a car, ‘he can buy a second-hand car using a website (e.g. Ebay), he can rent a car on a car-rental company website (e.g. Herzt or Car2Go), he can hire on-demand an individual to drive on his place using a site (e.g. Uber), he can rent a car from a private individual (e.g. Relayrides)’ (Frenken et al. Citation2015, p. 5).

An in-depth analysis of the digital service economy from a territorial perspective is particularly crucial at least for two reasons. First, typifying the different modes through which the digital service economy can take place (and, thus, redesign the boundaries between products and services) enables identifying the actors involved in market exchanges and, thus, how economic value is created and distributed among them. This effort is warranted as digitalisation is expanding the ways of doing business, opening to new formal and informal rules in the ways markets operate. The awareness of the plurality of actors and sources of value creation involved in the different types of digital service economy is crucial in order to understand, anticipate and, if needed, mitigate the socio-economic consequences the digital service economy may generate. In fact, its expansion opens opportunities for business activities and on-call contingent work, but it is also feared for the potential instability and low quality of jobs being created, and for the possibly unequal income distribution generated. The measurement of such positive and negative effects and their final balance in different economies requires a clear identification of the different value creation and distribution models, and their respective actors, involved in the digital service economy. In this respect, several studies have investigated both the impact of computerisation, robotisation and, more generally, technical change on labour force and wage inequalities (see for instance Acemoglu, Citation2000; Calvino and Virgillito Citation2017; Santarelli, Staccioli, and Vivarelli Citation2021). However, scarce interest has been devoted to the spatial dimension of such relationships, and there is still limited understanding of which territories are most affected and why by the new diffusion of specific technologies. Moreover, even if the literature on platforms has warned against the potentially detrimental effects of digitalisation on labour force conditions (Koutsimpogiorgos et al. Citation2020; Kenney and Zysman Citation2016; Kornberger, Pflueger, and Mouritsen Citation2017), the spatial implications of such phenomenon have not yet been fully elaborated and developed. Overall, therefore, the territorial dimension of the digital service economy, as intended in this work, has been somewhat neglected in the literature. This is particularly unfortunate given the important debate on territorial servitisation and knowledge-intensive business services (KIBS) flourished in the last years (Capello and Lenzi, Citation2021a; De Propris and Bailey Citation2020; Barzotto et al. Citation2019; Vaillant et al. Citation2021; Sisti and Goena Citation2020; Gomes et al. Citation2019; Sforzi and Boix Citation2019; Vendrell-Herrero and Bustinza Citation2020). Yet, there is an urgent need for deeper knowledge and understanding of which value creation model prevails in a local economy so as to be able to anticipate its socio-economic impacts. Even though regional studies increasingly examined the spatial consequences of digital technology adoption in manufacturing (De Propris and Bailey Citation2020), less is known about the territorial implications of the more general and pervasive digital service economy, which does not just involve the manufacturing sector. As long as digital platforms enable the large-scale, ubiquitous diffusion of technologies, the digital service economy can generate widespread benefits for users and (independent) service providers located not only in advanced regions but also in more remote and peripheral ones.

This paper, then, aims at replying to these needs by offering an encompassing view on and a thorough analysis of the digital service economy from a territorial perspective. It does so by conceptually distinguishing three main forms of value creation models that involve different actors, sources of value creation and value distribution (sec. 2). On empirical grounds, the paper proposes a methodology to identify the prevailing digital service economy value creation model in each European region (sec. 3). The geographical distribution of each single digital service economy value creation model is obtained as the first step for the identification of a taxonomy of European regions based on their prevailing digital service economy model (sec. 4). The identification of the spatial diffusion of the digital service economy in Europe, in all its different forms and combinations, serves future research purposes to measure its expected heterogeneous effects across regions (sec. 5).

2. The digital service economy

2.1. The Vlaue Creation Models

Digitalisation is revolutionising market transaction mechanisms, and thus value creation models, and is increasingly pushing businesses to sell services, products or contents on on-line markets, frequently managed by platforms. Digital platforms replace bilateral with trilateral relationships, involving a producer (a worker, a content producer, a service producer), a requester, and the platform (Koutsimpogiorgos et al. Citation2020). A digital platform can therefore be defined as a ‘matchmaker’ between producers who offer a production capacity and recipients interested to use, buy, or enjoy it (Kornberger, Pflueger, and Mouritsen Citation2017).

The complexity of the phenomenon has pushed a vast literature to interpret it by distinguishing between different types of digital platforms on which these services are offered. Some authors developed such distinction according to the service offered (e.g. platforms for platforms, platforms mediating work, retail platforms, etc.) (Kenney and Zysman Citation2016), others using the function played by the platform (e.g. platforms facilitating durable goods to be exploited more efficiently, platforms to share assets, etc.) (Schor Citation2016). This gave rise to a wide range of labels to indicate the radical changes in place: from platform capitalism (Srnicek Citation2016) to sharing economy (Schor Citation2016), collaborative consumption (Botsman and Rogers Citation2010), multi-sided markets (Evans and Schmalensee Citation2016), or common-based peer production (Benkler Citation2002). Despite the interest in attempts to classify digital platforms, and their validity within the specific studies undertaken, they hardly fulfil the need to separate out the value creation models developed within the digital service economy, a necessary effort in order to understand their positive and negative effects in different territorial contexts.

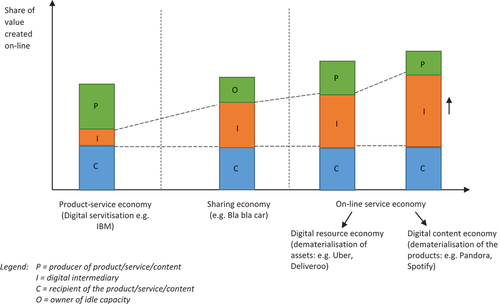

A way to distinguish between different value creation models within the digital service economy is through the identification of the different actors involved and the distinct sources of value creation and distribution. Specifically, digital platforms can perform their role of ‘matchmaking’ in different (and increasingly complex) ways. Firstly, they can purely serve as a technical basis to generate digital value chains to enable inputs from suppliers and customers. Secondly, they can facilitate transactions by easing the matching of buyers and sellers’ needs. Thirdly, they can enrich the role of pure intermediaries by selling their own services, products and contents competing with those offered by the providers hosted on the platform itself. In the same vein, producers of the service, goods or contents offered can be manufacturing firms, as well as an owner of a resource with idle capacity, or of spare time. Finally, recipients are users of the services or goods offered, being consumers or firms. sketches the main value creation models identified in the frame of the digital service economy, which are presented hereafter.

2.2. Product-service economy: from servitisation to digital servitisation.

The first value creation model is the product-service economy. This model refers to the original definition of servitisation. In the 1980s, when it was coined, servitisation was defined as ‘the increased offering of fuller market packages or “bundles” of customer-focused combinations of goods, services, support, self-service and knowledge in order to add value to core corporate offerings’ (Vandermerwe and Randa Citation1988, p. 319), facilitated by information and communication technologies (ICT). In short, servitisation represents a strategy put in place by manufacturing firms to offer services together with the product, in order to boost firm survival and competitiveness, more generally (Dachs et al. Citation2014). Large companies, such as IBM and Rolls Royce, pioneered this strategy by offering services linked to their products (Neely Citation2007; Bryson Citation2009).

Specifically, servitisation indicates a transition process through which firms increasingly offer a variety of services to users (frequently customers): technological training, consultancies, repair and maintenance as well as cyber-physical systems-related services. Manufacturers redesign their business models from product-only offers to service-oriented offers, shifting the business perspective from a product-based business model to a demand-oriented one (Müller, Buliga, and Voigt Citation2018). Consequently, the boundaries between manufacturing and services are increasingly blurred, and manufacturing is becoming a hybrid production system made up of a combination of goods and services (Sforzi and Boix Citation2019; Lafuente, Vaillant, and Vendrell-Herrero Citation2019).

It is not a simple process since manufacturing firms need to access competences that would naturally reside outside a manufacturing production process. The capacity to re-orient and evolve manufacturing activities to offer services – such as customised design, repair and maintenance, consultancy of different kinds – as complements to, or substitutes for, the produced goods is typical of large firms. SMEs instead tend to buy such services from external service providers in order to offer them with the product itself. They can buy them on an international market or from local service providers. When the local market is characterised by a strong local interdependence between manufacturing firms and KIBS, especially those dedicated to technical services (T-KIBS), a territorial servitisation is identified (Sforzi and Boix Citation2019; Lafuente, Vaillant, and Vendrell-Herrero Citation2017, Citation2019; Sisti and Goena Citation2020).

Digitalisation is boosting and enriching this traditional idea of servitisation, although the transition to digital servitisation is neither automatic nor simple (Opazo-Basáez, Vendrell-Herrero, and Bustinza Citation2022; Gebauer et al. Citation2021; Kohtamäki et al. Citation2019, Citation2020, Citation2021). Specifically, digital servitisation refers to the deployment of digital technologies to create and seize value from product-service offerings, i.e. value creation stems from the supply of tangible products supported by additional digital or digitally enabled services, such as on-line support and remote monitoring (Tian et al. Citation2022). In this respect, digital platforms can facilitate this transition by improving relationships with customers (front-end platforms) as well as with suppliers (back-end platforms), and manufacturers may rely on outsourced platforms as well as develop their own ones up to provide platforms as a service.

In the past, the role played by digital intermediaries was merely that of enabling an efficient information exchange through ICTs (). The value created was mainly split between producers and recipients, the former enjoying an increase in market shares, the latter enjoying a greater product differentiation, and quality increase, with the ICT providers gaining from the service provision. The recent digitalisation trends, however, are suggesting more complex configurations, with manufacturing firms expanding their role and establishing their own platforms if not offering platform services (Eloranta and Turunen Citation2016; Kohtamäki et al. Citation2019; Cenamor et al., Citation2017). In fact, digitalisation transforms companies’ business models, reshapes the firm's boundaries and redefines the interactions and relationships across actors, extending operations beyond the boundaries of single firms (Kohtamäki et al. Citation2019). These trends have been thoroughly analysed by the strategy and management literature that proposed conceptualisations of the digital servitisation business models. As Baden-Fuller and Morgan (Citation2010) pointed out, investigating business models is fundamental to understanding the functioning of firms’ behaviours and transformation as they are based on both observation and theorising. In the context of digital servitisation, several business model typologies have been identified based on solution customisation, solution pricing and solution digitalisation (see Kohtamäki et al. Citation2019 for a detailed description and categorisation). Furthermore, several studies recognise and put forward the idea that the evolution of digitalisation and technology advancement urge companies looking beyond their boundaries and being integrated in a value ecosystem (Bustinza et al. Citation2019; Hedvall, Jagstedt, and Dubois Citation2019).

Table 1. Value creation models in the digital service economy: actors, value creation and distribution.

2.3. Sharing economy: on-line markets of idle capacity

The advent of digital platforms and the possibility to create on-line markets have widened the opportunities and choices of consumers to get a product and/or a service, further enlarging the boundaries and scope of the digital service economy.

One of such additional possibility generated by the digital service economy for the supply of products offered on on-line markets via a website, or via digital intermediaries, is the so-called sharing economy. The sharing economy involves trilateral transactions, characterised by the exchange of products, services or contents through digital intermediaries (Schor Citation2016).

Specifically, in this work, the label sharing economy is associated with the creation of new markets for underutilised, idle, assets (Frenken and Schor Citation2017). The sharing economy can therefore be defined as an economy that generates ‘value in taking under-utilised assets and making them accessible on-line to a community, leading to a reduced need for ownership’ (Stephany Citation2015, p. 205), or as that of ‘on-line platforms that help people share access to assets, resources, time and skills’ (Wosskow Citation2014, p. 13).

The sharing economy is in fact a situation in which idle resources (e.g. a spare seat in a car, a spare bedroom and spare time) are made temporarily accessible to other users upon payment, on the basis of a peer-to-peer exchange. The owner of the resource can exchange its excess capacity, which in an offline situation would have had no value. New product and service exchanges take place by exploiting existing resources, i.e. the volume of transactions, and thus value creation, increases keeping assets and resources constant.

Sharing idle capacity is a practice that has not been invented in the digital era. People are used to lending or renting products from others (Frenken Citation2017). However, this takes place among trusted people, among relatives or friends, and in any case among people who know each other very well. In most cases, this sharing takes place for free. What is new in this modern form of sharing economy is that this activity creates value by sharing idle capacity among people who do not know each other at all, what has been called ‘stranger sharing’ (Schor Citation2016).

Influenced by a misconception of the word sharing, wrongly interpreted as sharing with others because of the social and altruistic nature of mankind and not for financial remuneration (Belk Citation2007), the identification of the sharing economy as a no value exchange is self-propelled by digital platforms because of the positive symbolic message and effects it generates (Frenken and Schor Citation2017). Instead, everything ‘shared’ in the sharing economy has a value. As Frenken and Schor (Citation2017, p. 4) claim, ‘a good definition of sharing economy is an economy where consumers grant each other temporary access to under-utilized physical assets (“idle capacity”), possibly for money’.

The value created on-line is much higher than the one of the product-service economy in that idle resources existing in the economy assume an exchange value (). A free place in a car or a second house, for example, are resources that obtain an economic value, allowing this value creation model to be interpreted as a remedy for a hyper-consumerist culture and a possible way to activate circular economy models (Schor et al. Citation2015).

The platform plays the role of pure intermediary, creating the market and playing the role of matchmaking. Intermediaries own the data on suppliers and customers, enabling them to match demand and supply rapidly with low transaction and search costs. Moreover, intermediary platforms can open new markets for new services and enlarge their market shares through users’ subscriptions and selling advertisement space. Digital platforms also rely on the high speed, low transactions and search costs, i.e. on selling an efficient and reliable intermediary service. This cost abatement is achieved by guaranteeing speed in finding the customised service, reliability in third parties, and efficiency in contractual arrangements.

The value is distributed among the three players. Providers obtain extra earnings and users lower prices, with a very low risk of free riding behaviours, because of fear of social sanctions such as bad rating (even if known as being inflated and not very accurate) or loss of reputation on the platform (Frenken and Schor Citation2017) (). The advantages obtained for owners and recipients of the resources enormously amplify the volume of transactions favouring disproportionate gains for digital intermediaries. The last ones for sure gain the largest profit share through the creation of a two-sided market, defined as a market in which intermediaries make possible exchanges that would not occur without them and create value for both sides. Intermediaries can generate value by simplifying and accelerating transactions, as well as by lowering the costs for the parties they connect. As the two sides of the network grow, successful platforms can scale up. Users, seeing a larger potential marketplace, will then pay a higher price to access the platform, increasing the intermediaries’ profits.

Textbook examples in this respect are BlaBlaCar, TaskRabbit, AirBnB, as far as their role remains that of a pure intermediary.

2.4. On-line service economy

The on-line service economy represents an even more complex form of digital service economy model. This takes place in two forms. The first one is when digital platforms provide services and products (e.g. mobility solutions, food and beverage services, and payment systems) without owning the assets necessary to produce and/or deliver such services or goods, i.e. when resources are dematerialised. The second one is when the products are dematerialised, and the digital platform sells the contents.

The digital resource economy presents some characteristics that make this business model unique with respect to the previous ones. First, the digital resource economy relies on the dematerialisation of assets (). Such dematerialisation rests on the unbundling of products from the service a product can offer, thus enabling an important shift from purchasing goods to using goods and paying for the utilisation, the function or the utility consumers may extract from the product, e.g. by renting or leasing it. In the case of Uber, the asset (a car) is unbundled from the service it may provide (a ride). It is dematerialised into a service (a ride); the intermediate service becomes the primary source of value creation. ‘[…] users actually pay for the utilisation, the function or the utility they extract from the product – without owning it. Indeed, without owning the product, users in fact access and pay for a service […] they do not buy a car but pay for a mobility solution’ (De Propris and Storai Citation2019, p. 390). Even if some of the new on-line services have their analogue counterparts, the on-line service economy helps not only to expand the customer base but also the range of possibilities to use a service.

Digital platforms play a specific role in the digital resource economy. They are service market makers and provide service or goods, without owning the assets. Uber does not possess a fleet of cars, as much as Foodora or Justeat operates without having restaurant facilities, or Stripe is active without owning nor managing any payment system. What intermediaries own is the data on suppliers and customers, enabling them to match demand and supply rapidly with low transaction and search costs.

The value created on-line is high and greater than in the case of the sharing economy since digital platforms do not only ‘match’ producers and recipients. Digital platforms enable new business and job opportunities (). In the case of Uber, the user of the service creates new capacity by ordering a ride on demand. Without such a demand, the service would not be created. By contrast, in carpooling, the capacity of transport is created by the driver in any case, and the service user only occupies a seat that would otherwise remain empty. This distinction led to the definition of the services offered by platforms like Uber ride-hailing companies instead of ride-sharing as in the case of BlablaCar (Frenken and Schor Citation2017).

The digital resource economy relies primarily on on-call contingent workers, frequently using their own tools and equipment to perform the productive work associated with the supplied service (Stanford Citation2017). Service providers (e.g. Uber drivers or Deliveroo riders) are often temporary or part-time workers, if not freelancers, who are willing to participate in the market to obtain some earnings by offering their spare time and skills since it is relatively fast, frictionless and cheap. These workers are commonly known in the literature and in the press as gig workers. Even if associated with the creation of business and job opportunities, the digital resource economy is feared primarily because of the unequal income distribution they create, favouring digital platforms (Rahman and Thelen Citation2019). Moreover, platforms creating on-demand work are open to huge problems in terms of low quality and stability of new jobs created. In general, the gig economy is destined to provide little incentive for platforms to address market failures that affect workers (Kornberger, Pflueger, and Mouritsen Citation2017; Koutsimpogiorgos et al. Citation2020; Stanford Citation2017). Many platforms set prices and standards for task delivery, monitor workers' performance and establish discipline, exerting a degree of control (Drahokoupil and Piasna Citation2017), at a level that it has been claimed that the ‘Uberification of the economy is resulting in a deterioration of living standards’ (Kornberger, Pflueger, and Mouritsen Citation2017, p. 80).

This type of services is very attractive for final users because of their low prices, and the lower the prices, the larger the customer base and the demand, leading to consumer surplus gains. The more demand increases, the more appealing the platform becomes for additional service providers willing to satisfy the new, yet unmet, demand. Therefore, for each price cut, both final consumers and service providers can obtain gains, leading to an expansion of the market.

Similar considerations apply to the case of the digital content economy, with an important distinction. The value created is possibly larger when the intermediaries create a market for contents, like music and video rather than services (right hand-side histogram in ). Instead of offering an existing service through different and complementary (digital) channels as in the digital resource economy, digital platforms replace existing products and services with new services. For example, instead of selling CD or DVD, they sell on-demand contents (a song, a specific video), which are subject to replicative and infinite sales without any additional production costs (Rullani and Rullani, Citation2018). At the same time, some contents, like a football match, are subject to infinite sales when streamed on-line.

The content re-use multiplier and the infinite markets are sources of extraordinary profits for digital intermediaries, who gain most of the value created. In the case of digital content economy (right-hand side histogram in ), the share of value gained by intermediaries increases more than in the case of the digital resource economy. Digital content platforms connect directly content producers (e.g. musicians if not the platform itself) to final recipients, thus replacing traditional off-line content distributors (i.e. majors) as well as the manufacturers of content physical support. The creation and sharing of on-line content are expected to enlarge business and job opportunities in the near future. Digital platforms, like TikTok or YouTube, are increasingly amplifying such possibilities, in some cases enabling superstar compensations for contributors (e.g. influencers).

As in the case of the digital resource economy, intermediary platforms operate in a two-sided market and produce value for both groups of users connected to the platform. Producers and recipients grasp part of the value created. The former enjoy new business and job opportunities as well as enlarged markets. The latter obtain utility gains like mass customised services, low opportunity costs and high speed in purchase. While for recipients the value grasped is the same in both cases, for producers the value created is higher in the case of digital resource economy than in digital content economy. The former value creation model produces new business and job opportunities, while the second business model attributes to platforms the value previously obtained by off-line business activities (e.g. record majors and manufacturers of content physical support), often no longer active. In fact, a fierce competition is generated between on-line and off-line activities. Record majors, publishing and printing companies are examples of businesses put under severe competition by on-line platforms, selling digital contents replacing traditional products (e.g. CD and physical books).

Separating out the different value creation models (i.e. agents involved, sources of value creation and value distribution) entailed by the digital service economy and detecting them in reality, in their possible mutual combinations, is a fundamental and preliminary effort necessary to measure the net effects of the digital service economy in regional economies. An effort like this has never been tackled before and is presented in the next part of the paper.

3. The identification of the digital service economy value creation models: methodology and indicators

3.1. Identification of single value creation models in European regions

The complex and multifaceted nature of the digital service economy makes extremely difficult the mapping of the spatial distribution of its different value creation models. In fact, it is substantially impossible, given their nature, to define a specific location for digital platforms. The present work overcomes such a limit by focusing on the more traditional players (i.e. producers and recipients) involved in the different value creation models, whose location is easily identifiable and their transition to on-line markets measured through their intensity of adoption of digital technologies. The different value creation models can be distinguished, on the basis of the regional specialisation and adoption of digital technologies in different specific and representative sectors:

manufacturing has been chosen as the main sector involved in the product service economy. Regions with a stronger manufacturing profile, therefore, represent the best setting for the product service economy. Accordingly, the higher the pervasiveness of manufacturing activities in a region, the higher the probability to shift towards the product service economy and to develop new technology-led services within the sector. On the other hand, the regional share of on-line sales in the manufacturing sector has been used to measure the intensity of adoption and to account for capacity of delivering additional services to users;

food and beverage and retail are considered as the most representative sectors for the on-line service economy.Footnote2 More specifically, the food and beverage sector accounts for sectors with a short-range delivery system whilst retail for those with a long-range delivery system. The latter can produce disruptive effects on off-line activities, both local and extra-regional ones, whereas the former stimulates competition only between on-line and off-line local activities. Specifically, the on-line service economy has been identified by looking at the regional specialisation and the regional share of on-line sales in each of the two sectors.

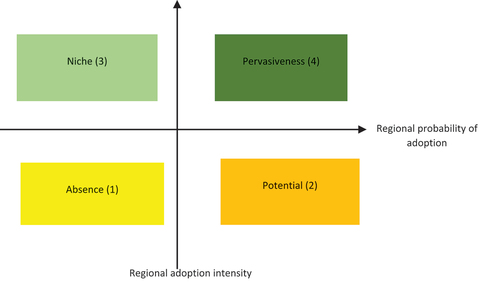

By crossing the regional sectoral specialisation and the regional sectoral adoption intensity, four possible situations arise ():

absence of a specific value creation model, when both regional sectoral adoption intensity and sectoral specialisation are below the national mean;

potential value creation model, when regional sectoral adoption intensity is below the national mean in sectors of specialisation;

niche value creation model, when adoption intensity is high in sectors that are not those of specialisation;

pervasive value creation model, when both indicators are above the national average.

For what concerns the sharing economy, the regional adoption is measured through the share of population exchanging goods and services on-line. The diffusion of digital technologies in the local population instead accounts for the probability of the phenomenon to occur and is measured with the regional share of population using the Internet daily. Crossing the two indicators, the same four situations highlighted above (and presented in ) arise.

summarises the indicators used to measure the regional probability of adoption and the regional adoption intensity for the three identified value creation models. The reference year for the variables used to compute the four categorical variables (i.e. probability and intensity of adoption) is 2010. All data used for the computation of the indicators described above have been sourced from EUROSTAT. Specifically, regional sectoral specialisation in the different sectors is analysed on the basis of EUROSTAT Structural Business Statistics for the period 2008–2016. Data on regional intensity of on-line sales is sourced from EUROSTAT at the sectoral national level, next apportioned at the regional level, as proposed by Capello and Lenzi (Citation2021b). Importantly, each indicator has been standardised with respect to the national value to mitigate strong country effects.Footnote3

Table 2. Value creation models in the digital service economy and their respective indicators.

3.2. Identification of the prevailing value creation model in European regions

The characteristics and the distribution in space of each specific value creation model are interesting and informative per se; importantly, however, the different value creation models may co-exist in regional economies and may spatially combine. Although with different intensities, more than one value creation model might occur in each regional economy. In fact, the digital service economy is a complex and radical phenomenon that can simultaneously involve different sectors, actors and markets. The co-presence of multiple and continuously evolving value creation models differently distributed across European regions might generate great opportunities and challenges related to productivity growth and social threats.

To empirically detect the potential different combinations, a k-means cluster analysis has been used to group European regions according to their predominant digital service economy value creation model. More in detail, the four classification variables described in the previous section, each capturing a specific value creation model, i.e. product service economy, sharing economy, on-line service economy in food and beverage services and on-line service economy in retail, have been considered. All these variables range from 1 to 4 following the taxonomy presented in (i.e. 1 stands for absent; 2 for potential; 3 for niche; 4 for pervasive value creation model). Various statistical criteria have been considered to identify the appropriate number of clusters to be retained, such as the relationship between within-cluster and between-cluster variance, but also the number of regions per se. The balance between the information advantages provided by expanding the number of clusters and the interpretability of the results supported the extraction of five clusters. These five clusters were overall highly stable. Repeating the extraction with different similarity measures and specifying different k random initial group centres yielded highly consistent results. In fact, only a minor portion of regions was assigned to a different group. In conclusion, the five groups of regions can be plausibly interpreted as regional patterns of digital service economy, each characterised by different combinations and intensity of the alternative value creation models.

4. The digital service economy in European regions

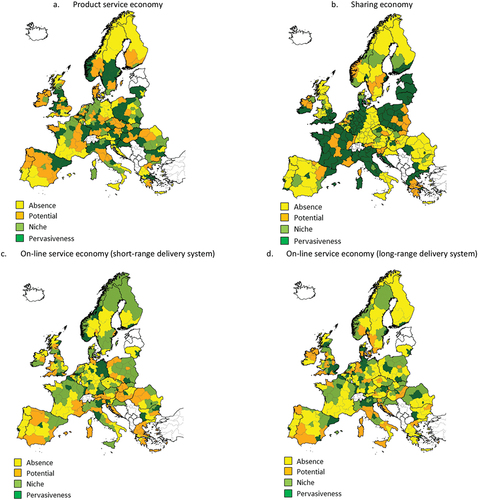

maps the different digital service economy value creation models in European regions. For each map, yellow-coloured regions represent the cases in which value creation models are absent, orange-coloured regions the cases in which value creation models are still potential; light green regions are in a niche stage and, finally, dark green-coloured regions are those regions in which value creation models are pervasive.

As evident from , only some of the most industrialised European regions (e.g. north-eastern Spain, Rhine-Rhur Valley, Northern Italy, Silesia) have adopted pervasively the new value creation model associated with the product service economy. This geography is relatively consistent with existing literature (Lafuente, Vaillant, and Vendrell-Herrero Citation2017, Citation2019; Sforzi and Boix Citation2019; Vendrell-Herrero and Bustinza Citation2020). For what concerns the sharing economy (), most of the countries display a clear divide between regions shifting towards this value creation model and those that have not made this transition yet. This distinction reflects the division between more developed and less developed regions (e.g. Northern and Southern Italy, richest regions of Portugal and the rest of the Country; Northern and Southern England). Other countries, notably France and Poland, are instead characterised by overall high levels of Internet use, and the distinction is exclusively based on the use of the Internet to buy and sell on-line.

The on-line service economy with a short-range delivery system (i.e. food and beverage services) is clearly an urban phenomenon. It is highly pervasive in almost all the capital city regions (). Finally, the on-line service economy in the form of e-commerce (i.e. retail) is instead heterogeneously spread across different types of regions in Europe and includes several intermediate areas (see ).

Even though the results of are of interest per se, each of them is somewhat partial since the different digital service economy value creation models can coexist and combine heterogeneously across regions.

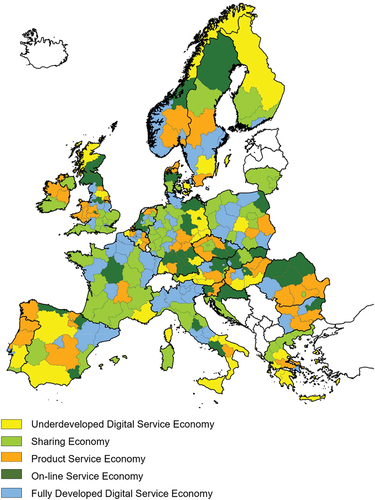

In fact, the cluster analysis highlights the existence of five digital service economy patterns, namely:

underdeveloped digital service economy: regions in this cluster are characterised by the lack of any digital service value creation model and are generally weak regions from the technological and economic point of view. This pattern includes 39 regions in which no type of digital service economy is particularly developed (Table A1);

sharing economy: the distinctive trait of regions in this cluster is the predominant presence of a pervasive sharing economy. Other digital service economy value creation models are instead less developed and remain either potential or not at all occurring. 72 regions belong to this cluster (Table A1);

product-service economy: regions in this cluster predominantly show a strong industrial profile and are characterised by a digital service value creation model either pervasive or potential. A remarkable trait of this cluster is the absence of all the other types of value creation models. The geography of this group of regions aligns with studies conducted at the national level (Vendrell-Herrero and Bustinza Citation2020). This pattern includes 49 regions (Table A1);

on-line service economy: regions in this cluster show a pervasive on-line service economy in both its forms, i.e. with short- and long-range delivery systems (Table A1);

fully developed digital service economy: regions in this cluster score high in terms of all digital service economy value creation models and are characterised by a favourable environment to technology adoption and use in businesses and society.

presents the five digital service economy patterns in Europe. As evident from the map, a first interesting result is that there are different patterns of digital service economy within countries. The most advanced areas of Europe and most of the regions hosting capital cities present a fully developed digital service economy. Some exceptions to this common trend can be found in Eastern countries capital city regions that instead present an advanced sharing economy. This same pattern characterises several regions without specific common traits; the sharing economy in fact involves both advanced and relatively marginal regions. The product-service economy is widely diffused in regions with a strong industrial specialisation profile, whilst the on-line service economy is well distributed across European countries and includes several intermediate areas. Marginal and less-developed regions are not at all affected by the new value creation models, thus presenting an underdeveloped digital service economy.

To better understand the context conditions that characterise each of the five patterns of digital service economy, an ANOVA analysis has been conducted on some specific regional socio-economic characteristics and the main variables used for the clustering exercise, i.e. adoption intensity and probability to adopt ().Footnote4 Importantly, the significance of the ANOVA test performed on each dimension is an indication of how well the respective dimension discriminates between clusters.

Table 3. Digital service economy patterns and their socio-economic context conditions (results from ANOVA).

The five digital service economy patterns present statistically significant differences concerning most of the several socio-economic territorial aspects. Description and sources of these variables are presented in Table A2 in the Appendix. The highest prosperity in terms of economic conditions, human capital and innovation characterises both the sharing economy and the fully developed digital service economy patterns. These two patterns are also similar in the high use of Internet for social, banking and political purposes. However, as expected, the sharing economy pattern does not occur in metropolitan contexts, which is instead the case for the fully developed digital service economy one.

Noticeably, two are the predominantly urban phenomena: the fully developed digital service economy and on-line service economy patterns. Nevertheless, they differ in terms of socio-economic conditions and, mostly, entrepreneurial spirit and economic dynamics. Concerning these conditions, the fully developed digital service economy pattern displays higher values. Differently, the on-line service economy pattern is characterised by a greater share of low-skill occupation and a lower Internet use for social, banking or political purposes.

As for the remaining two patterns, the underdeveloped digital service economy and the product service economy, they are characterised by the highest median age of the regional population and by the largest share of low-skill occupations. They both occur mainly in non-metropolitan areas (especially the product service economy) and present low levels of innovativeness, entrepreneurial impulse and economic dynamism.

Interestingly, and in line with the literature on territorial servitisation (see for instance Lafuente, Vaillant, and Vendrell-Herrero Citation2017; Sforzi and Boix Citation2019), the regional presence and embeddedness of knowledge-intensive services is extremely important for the development of any model entailed by the digital service economy. In fact, the underdeveloped digital service economy is the pattern that significantly differs from the others, presenting the lowest share of people employed in knowledge-intensive services.

5. Conclusions

The work has presented a first attempt, to our knowledge, of conceptualising and detecting empirically the different value creation models within the complex phenomenon of the digital service economy, and identifying the prevailing digital service economy value creation model in European regional economies.

Building on the rich literature on servitisation and, especially, territorial servitisation, the paper has proposed an encompassing view on how digitalisation is affecting the complex relationship between product and service offerings, further blurring the boundaries between manufacturing and services, in favour of the latter.

Specifically, the paper has complemented existing literature by separating out on conceptual and empirical grounds the different value creation models entailed by the digital service economy. Each model, in fact, involves different actors, different configurations of on-line transactions, associated with different sources of on-line value creation, and different distributive channels of such value. As widely explained in the paper, the identification of each digital service economy value creation model is fundamental to anticipate the different socio-economic impacts that it generates.

The result obtained in the work has highlighted a rather spatially heterogeneous situation in terms of pervasiveness of each model in the different European regions. When the empirical analysis looked for the co-presence of the different value creation models, it clearly came out that in most regions a specific one is emerging, leaving to the largest urban areas the co-presence of all forms of digital service economy, and to a few regions the non-existence of such a phenomenon. In most European regions, one value creation model clearly prevails over the others, thus enabling to anticipate the potential impacts that may derive. This large effort is in fact preliminary for the study and measurement of the impacts of the digital service economy.

The identification and assessment of the effects of the different digital service economy value creation models is extremely relevant from the policy perspective. Regions most exposed to the digital service economy are more likely to face important trade-offs between the economic opportunities it may open and its costs, in terms of raising inequalities, especially in the labour markets. For these regions, the rise in inequalities can represent an urgent and immediate issue requiring timely policy reply and intervention. Differently, in other regions not yet similarly exposed to these risks, anticipatory policy interventions could be appropriate to avoid a widening of disparities in the future once the digital service economy will become fully developed.

A few final cautionary word should be made about the limits of this study. Two aspects in particular deserve some attention. First, the empirical analysis did not consider digital platforms. Even if the localisation of digital platforms is particularly hard and their presence in the European territory is particularly scant, the inclusion of digital platforms would represent an important advancement. Second, the empirical analysis was unable to account for the digital content economy, due to incomplete data on adoption intensity and probability to adopt in the sectors most likely affected by these new value creation models, e.g. entertainment, publishing, video and television programme production, sound recording and music publishing activities. We hope to overcome these limitations in our future works.

Acknowledgement

This research has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (project “UNTANGLED”) under grant agreement No. 101004776.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

2 We are aware that the on-line service economy is in this way underestimated. Due to incomplete data on adoption intensity and probability to adopt in the sectors most likely affected by these new value creation models, e.g. entertainment, publishing, video and television programme production, sound recording and music publishing activities, the digital content economy is overlooked.

3 This choice leads to exclude from the analysis those countries composed of a single NUTS2 region (i.e. Malta, Luxembourg, Cyprus, Estonia, Latvia).

4 All the variables presented in have been calculated as location quotient, i.e. the relative regional value with respect to the national one. The reference year for these variables is 2010.

References

- Acemoglu (2000), “Technical Change, Inequality, and the Labor Market, NBER” Working Paper Series No. 7800.

- Acemoglu, D., and P. Restrepo. 2020. “Robots and Jobs: Evidence from US Labor Markets.” Journal of Political Economy 128 (6): 2188–2244.

- Baden-Fuller, C., and M. S. Morgan. 2010. “Business Models as Models.” Long Range Planning 43 (2–3): 156–171. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2010.02.005.

- Baines, T. S., H. W. Lightfoot, S. Evans, A. Neely, R. Greenough, J. Peppard, and J. R. Alcock. 2007. “State-of-the-art in Product-service Systems.” Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part B: Journal of Engineering Manufacture 221 (10): 1543–1552. doi:10.1243/09544054JEM858.

- Baines, T., A. Z. Bigdeli, O. F. Bustinza, V. Guang, J. Baldwin, and K. Ridgway. 2017. “Servitization: Revisiting the State-of-the-art and Research Priorities.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 37 (2): 256–278. doi:10.1108/IJOPM-06-2015-0312.

- Barrett, M., E. Davidson, J. Prabhu, and S. L. Vargo. 2015. “Service Innovation in the Digital Age: Key Contributions and Future Directions.” MIS Quart 39 (1): 135–154. doi:10.25300/MISQ/2015/39:1.03.

- Barzotto, M., C. Corradini, F. Fai, S. Labory, and T. P.r, eds. 2019. Revitalising Lagging Regions: Smart Specialisation and Industry 4.0. Oxford: Routledge.

- Belk, R. 2007. “Why Not Share Rather than Own?” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 611 (1): 126–140. doi:10.1177/0002716206298483.

- Benkler, Y. 2002. “Intellectual Property and the Organization of Information Production.” International Review of Law and Economics 22 (1): 81–107. doi:10.1016/S0144-8188(02)00070-4.

- Botsman, R., and R. Rogers, eds. 2010. What’s Mine Is Yours – The Rise of Collaborative Consumption. New York: HarperCollins Publishers.

- Brax, S., and K. Jonsson. 2009. “Developing Integrated Solution Offerings for Remote Diagnostics: A Comparative Case Study of Two Manufacturers.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 29 (5): 359–560. doi:10.1108/01443570910953621.

- Brynjolfsson, E., and M. A, eds. 2014. The Second machine Age: Work, Progress, and Prosperity in a Time of Brilliant Technologies. London and New York: W W Norton & Co.

- Bryson, J. R. , ed. 2009. Hybrid Manufacturing Systems and Hybrid Products: Services, Production and Industrialisation. Aachen: University of Aachen.

- Büchi, G., M. Cugno, and R. Castagnoli. 2020. “Smart Factory Performance and Industry 4.0.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 150: 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2019.119790.

- Buera, F. J., and J. P. Kaboski. 2012. “The Rise of the Service Economy.” American Economic Review 102 (6): 2540–2569. doi:10.1257/aer.102.6.2540.

- Bustinza, O. F., A. Z. Bigdeli, T. S. Baines, and C. Elliot. 2015. “Servitization and Competitive Advantage: The Importance of Organizational Structure and Value Chain Position.” Research-Technology Management 58 (5): 53–60. doi:10.5437/08956308X5805354.

- Bustinza, O. F., E. Lafuente, R. Rabetino, Y. Vaillant, and F. Vendrell-Herrero. 2019. “Make-or-buy Configurational Approaches in product-service Ecosystems and Performance.” Journal of Business Research 104 (C): 393–401. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.01.035.

- Calvino, F., and M. E. Virgillito. 2017. “The Innovation-employment Nexus: A Critical Survey of Theory and Empirics.” Journal of Economic Surveys 32 (1): 83–117. doi:10.1111/joes.12190.

- Capello, R., and C. Lenzi. 2021a. The Regional Economics of Technological Transformations – Industry 4.0 and Servitisation in European Regions. London: Routledge.

- Capello, R., and C. Lenzi. 2021b. “Industry 4.0 and Servitisation: Regional Patterns of 4.0 Technological Transformations in Europe.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 173: 1–14. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2021.121164.

- Cenamor, J., D. R. Sjodin, and V. Parida. 2017. “Adopting a Platform Approach in Servitization: Leveraging the Value of Digitalization.” International Journal of Production Economics 192: 54–65. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2016.12.033.

- Ciffolilli, A., and A. Muscio. 2018. “Industry 4.0: National and Regional Comparative Advantages in Key Enabling Technologies.” European Planning Studies 26 (12): 2323–2343. doi:10.1080/09654313.2018.1529145.

- Cornet, E., R. Katz, R. Molloy, J. Schadler, D. Sharma, and A. Tipping. 2000. Customer Solutions: From Pilots to Profits. Tyson Corner, VA: Booz Allen & Hamilton.

- Cusumano, M. A., S. J. Kahl, and F. F. Suarez. 2015. “Services, Industry Evolution, and the Competitive Strategies of Product Firms.” Strategic Management Journal 36 (4): 559–575. doi:10.1002/smj.2235.

- Dachs, B., S. Biege, M. Borowiecki, G. Lay, A. Jäger, and D. Schartinger. 2014. “Servitisation of European Manufacturing: Evidence from a Large Scale Database.” Service Industries Journal 34 (1): 5–23. doi:10.1080/02642069.2013.776543.

- De Propris, L., and D. Storai. 2019. “Servitizing Industrial Regions.” Regional Studies 53 (3): 388–397. doi:10.1080/00343404.2018.1538553.

- De Propris, L., and D. Bailey, Eds. 2020. Industry 4.0 and Regional Transformations. London: Routledge.

- Drahokoupil, J., and A. Piasna (2017), “Work in the Platform Economy: Beyond Lower Transaction Costs”, Intereconomics – Review of European Economic Policy, https://www.intereconomics.eu/contents/year/2017/number/6/article/work-in-the-platform-economy-beyond-lower-transaction-costs.html ( Retrieved 16/11/2021).

- EC (2021), The Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) 2021, available at https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/digital-economy-and-society-index-desi-2021, last accessed 03/02/2022

- Eloranta, V., and T. Turunen. 2016. “Platforms in Service-driven Manufacturing: Leveraging Complexity by Connecting, Sharing, and Integrating.” Industrial Marketing Management 55: 178–186. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2015.10.003.

- Evans, S., and R. Schmalensee, eds. 2016. Matchmakers – The New Economics of Multisided Platforms. Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Press.

- Frank, A. G., L. S. Dalenogare, and N. F. Ayala. 2019. “Industry 4.0 Technologies: Implementation Patterns in Manufacturing Companies.” International Journal of Production Economics 210: 15–26. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2019.01.004.

- Frenken, K., T. Meelen, M. Arets, and P. Van de Glind (2015), “Smarter Regulation for the Sharing Economy”, The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/science/political-science/2015/may/20/smarter-regulation-for-the-sharing-economy ( Retrieved 16/11/2021).

- Frenken, K. 2017. “Political Economies and Environmental Futures for the Sharing Economy.” Philosophical Transaction A 375: 1–15.

- Frenken, K., and J. Schor. 2017. “Putting the Sharing Economy into Perspective.” Environmental Innovation and Societal Transition 23: 3–10. doi:10.1016/j.eist.2017.01.003.

- Frey, C. B., and M. A. Osborne. 2017. “The Future of Employment: How Susceptible Are Jobs to Computerisation?” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 114: 254–280. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2016.08.019.

- Gebauer, H., M. Paiola, N. Saccani, and M. Rapaccini. 2021. “Digital Servitization: Crossing the Perspectives of Digitization and Servitization.” Industrial Marketing Management 93: 382–388. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2020.05.011.

- Gomes, E., O. F. Bustinza, S. Tarba, Z. Khan, and M. Ahammad. 2019. “Antecedents and Implications of Territorial Servitization.” Regional Studies 53 (3): 410–423. doi:10.1080/00343404.2018.1468076.

- Hedvall, K., S. Jagstedt, and A. Dubois. 2019. “Solutions in Business Networks: Implications of an Interorganizational Perspective.” Journal of Business Research 104 (C): 411–421. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.02.035.

- Hofmann, E., and M. Rüsch. 2017. “Industry 4.0 and the Current Status as well as Future Prospects on Logistics.” Computers in Industry 89: 23–34. doi:10.1016/j.compind.2017.04.002.

- Kenney, M., and J. Zysman. 2016. “The Rise of the Platform Economy.” Issues in Science and Technology 32 (3): 61–69.

- Kohtamäki, M., V. Parida, P. Oghazi, H. Gebauer, and T. Baines. 2019. “Digital Servitization Business Models in Ecosystems: A Theory of the Firm.” Journal of Business Research 104: 380–392. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.06.027.

- Kohtamäki, M., V. Parida, P. C. Patel, and H. Gebauer. 2020. “The Relationship between Digitalization and Servitization: The Role of Servitization in Capturing the Financial Potential of Digitalization.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 151: 119804. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2019.119804.

- Kohtamäki, M., T. Baines, R. Rabetino, A. Z. Bigdeli, C. Kowalkowski, R. Oliva, and V. Parida. 2021. The Palgrave Handbook of Servitization. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Kornberger, M., D. Pflueger, and J. Mouritsen. 2017. “Evaluative Infrastructures: Accounting for Platform Organization.” Accounting, Organization and Society 60: 79–95. doi:10.1016/j.aos.2017.05.002.

- Koutsimpogiorgos, N., J. van Slageren, A. M. Herrmann, and K. Frenken. 2020. “Conceptualizing the Gig Economy and Its Regulatory Problems.” Policy & Internet 12 (4): 525–545. doi:10.1002/poi3.237.

- Lafuente, E., Y. Vaillant, and F. Vendrell-Herrero. 2017. “Territorial Servitization: Exploring the Virtuous Circle Connecting Knowledge-intensive Services and New Manufacturing Businesses.” International Journal of Production Economics 192: 19–28. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2016.12.006.

- Lafuente, E., Y. Vaillant, and F. Vendrell-Herrero. 2019. “Territorial Servitization and the Manufacturing Renaissance in Knowledge-based Economies.” Regional Studies 53 (3): 313–319. doi:10.1080/00343404.2018.1542670.

- Lasi, H., P. Fettke, K. H-G, T. Feld, and M. Hoffmann. 2014. “Application-Pull and Technology-Push as Driving Forces for the Fourth Industrial Revolution.” Business & Information Systems Engineering 6: 239–242. doi:10.1007/s12599-014-0334-4.

- McAfee, A., and E. Brynjolfsson, eds. 2017. Machine, Platform, Crowd: Harnessing Our Digital Future. London and New York: W W Norton & Co.

- Müller, J. M., O. Buliga, and K. I. Voigt. 2018. “Fortune Favours the Prepared: How SMEs Approach Business Model Innovations in Industry 4.0.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 132 (7): 2–17. doi:10.1016/j.techfore.2017.12.019.

- Neely, A. (2007), “The Servitization of Manufacturing: An Analysis of Global Trends”, Paper presented at the 14th European Operations Management Association Conference, Ankara, Turkey, 17-19 June.

- OECD. 2020. OECD Digital Economy Outlook 2020. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/bb167041-en.

- Opazo-Basáez, M., F. Vendrell-Herrero, and O. F. Bustinza. 2022. “Digital Service Innovation: A Paradigm Shift in Technological Innovation.” Journal of Service Management 33 (1): - 97–133. doi:10.1108/JOSM-11-2020-0427.

- Paiva Santos, B., F. Charrua-Santos, and T. M. Lima (2018), “Industry 4.0: An Overview”, Proceedings of the World Congress on Engineering, Vol II, July 4-6, London, U.K.

- Porter, Michael E., and James E. Heppelmann. “How Smart, Connected Products Are Transforming Competition.” Harvard Business Review 92, no. 11 (November 2014): 64–88.

- Porter, Michael E., and James E. Heppelmann. “How Smart, Connected Products Are Transforming Companies.” Harvard Business Review 93, no 10 (October 2015): 97–114.

- Rabetino, R., M. Kohtamäki, S. A. Brax, and J. Sihvonen. 2021. “The Tribes in the Field of Servitization: Discovering Latent Streams across 30 Years of Research.” Industrial Marketing Management 95: 70–84. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2021.04.005.

- Rahman, K. S., and K. Thelen. 2019. “The Rise of the Platform Business Model and the Transformation of Twenty-First-Century Capitalism.” Politics & Society 42 (2): 177–204. doi:10.1177/0032329219838932.

- Rullani, E., and F. Rullani, eds. 2018. Dentro la rivoluzione digitale. Giappicchelli: Torino.

- Santarelli, E., J. Staccioli, and M. Vivarelli (2021), “Robots, AI, and Related Technologies: A Mapping of the Knowledge Base”, LEM Working Paper Series.

- Schor, J. B., E. T. Walker, C. W. Lee, P. Parigi, and K. Cook. 2015. “On the Sharing Economy.” Contexts 14: 12–19.

- Schor, J. 2016. “Debating the Sharing Economy.” Journal of Self-Governance and Management Economics 4 (3): 7–22.

- Schwab, K., ed. 2017. The Fourth Industrial Revolution. New York: Crown Publishing Group.

- Sforzi, F., and R. Boix. 2019. “Territorial Servitization in Marshallian Industrial Districts: The Industrial Districts as a Place-based Form of Servitization.” Regional Studies 53 (3): 398–409. doi:10.1080/00343404.2018.1524134.

- Sisti, E., and A. Z. Goena. 2020. “Panel Analysis of the Creation of New KIBS in Spain: The Role of Manufacturing and Regional Innovation Systems (RIS.” Investigaciones Regionales-Journal of Regional Research 48: 37–50. doi:10.38191/iirr-jorr.20.019.

- Srnicek, N., ed. 2016. Platform Capitalism. Cambridge and Malden: Polity Press.

- Stanford, J. 2017. “The Resurgence of Gig Work: Historical and Theoretical Perspectives.” The Economic and Labour Relations Review 28 (3): 382–401. doi:10.1177/1035304617724303.

- Stephany, A., ed. 2015. The Business of Sharing: Collaborative Consumption and Making It in the New Sharing Economy. Basingstoke, Hampshire, New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan, Houndmills.

- Storbacka, K. 2011. “A Solution Business Model: Capabilities and Management Practices for Integrated Solutions.” Industrial Marketing Management 40: 699–711. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2011.05.003.

- Tian, J., W. Coreynen, P. Matthyssens, and L. Shen. 2022. “Platform-based Servitization and Business Model Adaptation by Established Manufacturers.” Technovation. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2021.102222.

- Tukker, A. 2004. “Eight Types of Product–service System: Eight Ways to Sustainability? Experiences from SusProNet.” Business Strategy and the Environment 13 (4): 246–260. doi:10.1002/bse.414.

- Vaillant, Y., E. Lafuente, K. Horváth, and F. Vendrell-Herrero. 2021. “Regions on Course for the Fourth Industrial Revolution: The Role of a Strong Indigenous T-KIBS Sector.” Regional Studies 55 (10–11): 1816–1828. doi:10.1080/00343404.2021.1899157.

- Vandermerwe, S., and J. Randa. 1988. “Servitization of Business: Adding Value by Adding Services.” European Management Journal 6 (4): 314–324. doi:10.1016/0263-2373(88)90033-3.

- Vendrell-Herrero, F., and O. F. Bustinza. 2020. “Servitization in Europe.” In Industry 4.0 and Regional Transformations, edited by L. De Propris and D. Bailey, 24–41. London: Routledge.

- Vial, G. 2019. “Understanding Digital Transformation: A Review and a Research Agenda.” The Journal of Strategic Information Systems 28 (2): 118–144.

- Wang, S., J. Wan, D. Zhang, D. Li, and C. Zhang. 2016. “Towards Smart Factory for Industry 4.0: A self-organized multi-agent System with Big Data Based Feedback and Coordination.” Comput. Network 101: 158–168. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2015.12.017.

- Wosskow, D. (2014), “Unlocking the Sharing Economy: An Independent Review, Department for Business”, Innovation and Skills, London. Available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/unlocking-the-sharing-economy-independent-review ( Retrieved 16/11/2021).

- Wulf, J., T. Mettler, and W. Brenner. 2017. “Using a Digital Services Capability Model to Assess Readiness for the Digital Consumer.” MIS Quart. Exec 16 (3): 171–195.

Appendix

The following Table () shows the results of the k-means cluster analysis used to group European regions according to their predominant digital service economy value creation model described in Section 3.2. More in detail, the rows report the digital service economy value creation models (i.e., Product service economy, Sharing economy and On-line service economy) while the columns indicate the different intensity of adoption of new technologies (i.e. absence, potential, niche, pervasiveness). Five groups of regions have been identified through the cluster analysis that can be plausibly interpreted as regional patterns of digital service economy (i.e. underdeveloped digital service economy, sharing economy, product service economy, on-line service economy, fully developed digital service economy), each characterised by different combinations and intensity of the alternative digital service economy value creation models. below shows the number of regions belonging to each pattern of digital service economy and, for each of them, cells highlight the percentage of regions characterized by different degrees of adoption intensity in each specific digital service economy value creation model.

Table A1. – Regional patterns of digital service economy: results from the k-means cluster analysis.

Table A2. – Description and sources of the variables used in the ANOVA.