ABSTRACT

It is well-established that firms leverage both internal and external resources for their innovation activities. Even though the role of agglomeration economies in shaping the external resources available to firms has been particularly well-studied it is still unclear whether it is diversity or specialisation within agglomerations that drives firm innovativeness. We suggest that both do but that their relations with firm innovativeness are moderated by managerial industry experience. Using data from four South-East Asian economies we find that managers with more industry experience are better able to make the most of where they are, leveraging the opportunities afforded by their geographic environment. This finding is most pronounced in rural areas where firms with inexperienced managers almost never innovate, whereas half of the firms with experienced managers do. This suggests that future agglomeration research should be attentive to firm-level idiosyncrasies.

1. Introduction

It is well-established that firms leverage both internal and external resources for their innovation activities (Breschi Citation2000; Wang et al. Citation2016; Hervas-Oliver et al. Citation2018). The role of geography in shaping the external resources available to firms has been particularly well-studied, and the consensus is that location affects long-term innovation capacity (Stern and Porter Citation2001; McCann and Folta Citation2008; Carlino and Kerr Citation2015). After all, firms tend to stay in their region of origin even when growing rapidly (Knoben Citation2011; Stam Citation2007), and these regions evolve slowly (Fritsch, Kudic, and Pyka Citation2019; Ooms et al. Citation2015). However, little is known about why some firms manage to make the most of their location in the pursuit of innovation and why others fail to do so (Frenken, Cefis, and Stam Citation2015; Zhang Citation2017; Funk Citation2014).

Much of the literature examining geographic benefits to innovation considers the effect of two types of co-location, namely the concentration or agglomeration of many dissimilar firms on the one hand and the concentration of many similar firms on the other (McCann and Folta Citation2008). Geographic diversity – such as occurs in urbanised environments – coincides with the presence of high-quality infrastructures and a diversity in services and labour (Jacobs Citation1969; Herstad, Solheim, and Engen Citation2019). Specialisation – also known as localisation – gives access to a labour pool and services of a particular kind (Frenken, Cefis, and Stam Citation2015; Marshall Citation1890/1920). Both increase knowledge circulation and potentially spur innovation, but can also lead to knowledge leakage to competitors and congestion effects (Grillitsch and Nilsson Citation2019; Richardson Citation1995). Hence, such externalities are not always positive (Martin Citation2015; Phelps, Atienza, and Arias Citation2018).

Crucially, there is controversy about the context under which net effects will be positive or negative even among studies investigating the same region and time period (Beaudry and Schiffauerova Citation2009). Headway has been made in resolving this confusion by investigating how the effects of geography are moderated by firms’ internal characteristics such as absorptive capacity and size, but the matter remains unresolved (Frenken, Cefis, and Stam Citation2015; Naz, Niebuhr, and Peters Citation2015). In this recent line of research disparate theoretical and empirical conclusions abound: from the firms with the weakest internal resources benefiting (Grillitsch and Nilsson Citation2017), to them instead losing out and the strongest firms profiting (McCann and Folta Citation2011; Grillitsch and Nilsson Citation2019). In the present paper, we suggest that this conflicting state-of-the-art has been enabled by a neglect for the idiosyncrasies of firms and their managers (Frenken, Cefis, and Stam Citation2015; Rutten Citation2014). In essence, firms have mostly been assumed to be passive recipients of geographic externalities. Yet, in the related field of organisation studies it is accepted that firms differ in their ability to leverage internal and external resources, with their managerial characteristics a strong predictor (Balsmeier and Czarnitzki Citation2014; Acquaah Citation2012). Managers matter. In agglomeration research, however, this knowledge only seems to have filtered through in Zhang’s (Citation2017) study of the extent to which top manager age and educational level affect agglomeration effects for firm profitability. To the authors’ knowledge, innovation, a core driver of firm competitiveness (Cainelli, Evangelista, and Savona Citation2006), has not yet been investigated in this light – nor has managerial industry experience directly been considered.

In this paper, we suggest that the relation between agglomeration and firm-level innovation can be clarified through the moderating impact of managerial industry experience. Our accompanying research question is: ‘To what extent are the relations between geographic diversity (urbanisation), specialisation (localisation) and firm-level innovation moderated by industry-specific managerial experience?’ At the core of our argument is the notion that throughout their careers, managers accumulate knowledge and skills that are particular to their industry, enabling them to successfully navigate and leverage the firm-external environment (Balsmeier and Czarnitzki Citation2014). Concretely, their specific skills and understanding of the firm context could help them make the most of region-specific advantages for innovation while at the same time diminishing negative region-specific effects (Barasa et al. Citation2017). This ability may be critically important for firms in emerging market contexts, which are characterised by high environmental uncertainty and complexity – and have, coincidentally, received relatively little attention (Duranton Citation2015; Cirera and Muzi Citation2020; Resbeut, Gugler, and Charoen Citation2019). They are at risk of organisational paralysis, where firms stop adjusting to external conditions and instead of innovating stick to routine behaviour (Van Uden, Vermeulen, and Knoben Citation2019) – a counterproductive reaction that may be circumvented by experienced managers.

In what follows, we build our theory on how geographic conditions and managerial industry experience affect innovation. We relay what is known about their direct impacts and hypothesise how the latter may moderate the influence of the former. In the data and methods section, we present our research setting: four developing South-East Asian economies – Cambodia, Vietnam, Timor-Leste and Thailand. We explain how we used firm-level data from the World Bank Enterprise Survey. Following this, we present our analyses that show that, in general, more experienced managers are better able to exploit the opportunities afforded by their environment while compensating for its weaknesses. In our discussion, we unpack the implications of our research, and suggest ways in which the literature could better incorporate the role of firm-level idiosyncrasies in debates on agglomeration. This can help elucidate the many points of contention that characterise the scholarship and opens possibilities to develop practically relevant insights for both for firm managers and policy makers. However, as our results show that the influence of more experienced managers is not uniformly positive there is a need for future work to provide deeper explanations for why industry-specific managerial experience sometimes increases and sometimes decreases innovation.

2. Theoretical background

Innovation is broadly defined as ‘the generation, acceptance and implementation of new ideas, processes, products or services’ (Thompson Citation1965, 2). Although it is an inherently costly and risky endeavour (Dodgson Citation2000; Shefer and Frenkel Citation2005), innovation allows firms to build the necessary capabilities to survive and grow in complex and competitive markets (Cainelli, Evangelista, and Savona Citation2006). It may, for instance, allow products and services to be produced at lower costs or to become qualitatively better than those offered by competitors (Cantwell Citation2005). Despite its unchanged importance, the nature of innovation differs between developed and developing contexts (Van Uden, Knoben, and Vermeulen Citation2017). The further the context in which a firm operates is from the technological frontier, the more often innovation is only new to the firm itself, or to the market, instead of to the world (Ayyagari, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Maksimovic Citation2011).Below, we unpack the impact of geography on innovation, before turning to the influence of managerial industry experience. We then consider to what extent these two types of conditions are interrelated, and how industry experience could allow managers to successfully navigate the opportunities and threats posed by their environment. A total of five hypotheses are formulated.

2.1. Regional advantages

Although firms’ internal characteristics such as its knowledge base and managerial experience are factors in innovation (Peteraf Citation1993), firms’ environments also act as a resource (Hervás-Oliver and Albors-Garrigós Citation2007). Firms can for instance forgo costly, lengthy, and risky R&D projects and instead rely on the competences and advantages offered by their location (Hervas-Oliver, Sempere-Ripoll, and Boronat-Moll Citation2014). Such an approach may be particularly useful for SMEs that have relatively few internal resources to devote to internal learning (McCann and Folta Citation2008), although there is evidence that firms with higher levels of internal resources also benefit. For them, these externalities can complement internal projects and know-how (Speldekamp, Knoben, and Saka-Helmhout Citation2020). In this vein, economically diverse and specialised geographic concentrations are established as a potential resource to firms (McCann and Folta Citation2011). Economic diversity is greatest in cities, coinciding with infrastructural and industry-related advantages that decrease transaction costs and offer access to workers with varied skillsets and knowledge (Florida, Adler, and Mellander Citation2017; Lorenzen and Frederiksen Citation2007; Glaeser et al. Citation1992; Jacobs Citation1969). This urbanisation also increases the odds of dissimilar knowledge spillovers that are generated when workers switch jobs and carry over their knowledge to their new employer (Feldman Citation1999), and through chance meetings (Bathelt, Malmberg, and Maskell Citation2004). In short, knowledge can be transferred between economic sectors, facilitating experimentation and the carrying over of practices and ideas (Van Der Panne Citation2004).

The co-location of firms and organisations that are active in the same or similar economic activities affords different advantages: access to specialised services, infrastructure, potential collaborators, and a pool of specialised labour that facilitates industry-specific knowledge spillovers (Krugman Citation1991; Marshall Citation1890/1920; McCann and Folta Citation2008). Such localisation elevates industry-specific human capital, increasing workers’ productivity and capacity to do knowledge work (Rotemberg and Saloner Citation2000; Mayer, Somaya, and Williamson Citation2012). Further, the type of knowledge that spills over between firms will often closely match existing knowledge bases, and is therefore more easily assimilated (Boschma, Eriksson, and Lindgren Citation2009; Wixe Citation2015; Van Der Panne Citation2004). Finally, in addition to increasing the potential for innovation there is a heightened drive to pursue it as competition is heightened by co-location with similar firms (Porter Citation2000).

2.2. Regional disadvantages

Increasingly, scholars are aware that agglomerations can have adverse effects on firms. In urbanised regions, there is the potential for increased input costs (Richardson Citation1995), lowering profit margins and, indirectly, investments in innovation. Moreover, as the concentration of economic activity becomes denser real estate costs will rise (McCann and Folta Citation2008), as will transportation costs due to congestion (Louf and Barthelemy Citation2014). It has therefore been suggested that as the total size of an agglomeration increases beyond a critical threshold, pecuniary diseconomies can outweigh positive externalities and decrease the rate of firm-level innovation (Folta, Cooper, and Baik Citation2006). Similarly, localisation can negatively affect firms. In addition to the aforementioned diseconomies, such regions and their firms are vulnerable to becoming locked-in. This means that they become slow to adapt to changing industry conditions, and are less likely to generate and adopt innovation (Menzel and Fornahl Citation2010). Learning effects from co-location with firms and organisations in similar economic activities may initially support growth, but become a detriment as the knowledge diversity in the environment diminishes over time (Boschma, Eriksson, and Lindgren Citation2009; Pouder and St. John Citation1996). Notable examples of agglomerations where this has happened include Detroit’s automotive cluster and the Ruhr area’s coal and steel district (Menzel and Fornahl Citation2010). Finally, firms risk leaking their knowledge to nearby competitors, empowering them in the process, and endangering their own competitive advantage (Frenken, Cefis, and Stam Citation2015; Rigby and Brown Citation2015). As signalled in our introduction, there is no agreement on how the positive and negatives of urbanisation and localisation balance each other out (Beaudry and Schiffauerova Citation2009). This is true even in the recent stream of studies suggesting that firms’ level of internal resources shape the effects of agglomeration (Frenken, Cefis, and Stam Citation2015). There are studies showing that the net effects are mainly positive for weak (Grillitsch and Nilsson Citation2017), moderately strong (Hervas-Oliver et al. Citation2018; Knoben et al. Citation2016), and strong firms (Grillitsch and Nilsson Citation2019; McCann and Folta Citation2011). As Frenken, Cefis, and Stam (Citation2015, p. 19) conclude, ‘[o]ne of the main challenges in future research lies in reconciling [these] contradictory empirical findings’.

The confusion on the effects of agglomeration notwithstanding, the total number of studies evidencing positive results outweigh those with negative pecuniary and knowledge effects (Beaudry and Schiffauerova Citation2009). We take this into account in our two baseline hypotheses below. Nevertheless, we argue that a more interesting question than the net effects of external economies is what firms can do to maximise the benefits they derive from their environment while minimising its negative effects.

H1:

The higher the level of urbanisation in a region the higher the likelihood that a firm will become innovative.

H2:

The higher the level of localisation in a region the higher the likelihood that a firm will become innovative.

2.3. Managerial industry experience

Although the above has focused on firm-external resources, innovation is similarly affected by firm-internal characteristics such as the level of R&D and physical capital investments (Love and Roper Citation2015; Eisenhardt and Martin Citation2000; Naz, Niebuhr, and Peters Citation2015). Research has further pointed to the pivotal role of the general human capital that is embodied in a firm’s employees and determined by their education (Naz, Niebuhr, and Peters Citation2015), and to the specific human capital that is built through experience (Becker Citation1993; Capozza and Divella Citation2019). Regarding the former, more highly educated employees are better capable of knowledge work requiring the recognition, assimilation, and utilisation of disparate types of information – i.e. they have a higher absorptive capacity (ibid.; Cohen and Levinthal Citation1990). This applies to top managers as well, whose educational level elevates firms’ ability to adopt and develop innovations (Bantel and Jackson Citation1989). Regarding specific human capital, experience built at the team, firm, and industry level elevates employees’ insight into innovation possibilities and constraints – both within their firm and its competitive environment (Rulke, Zaheer, and Anderson Citation2000; Barasa et al. Citation2017). The effect of industry experience is especially well-established, and while it likely has a positive effects among all employees, its importance is elevated among managers who are at the helm of innovation efforts and act as firms’ ‘change agents’ (Rogers Citation1995; Crowley and Bourke Citation2018). As firm managers become more experienced overall, they pursue innovation more often, through more varied projects, and become better at selecting the most promising efforts (Barasa et al. Citation2017; Custódio, Ferreira, and Matosc Citation2019).

Managerial industry experience seems to be especially important for innovation in less developed contexts that are subject to rapid (technological) change (Ettlie Citation1990; Kim and Lee Citation1987; Balsmeier and Czarnitzki Citation2014). Here, general human capital is expected to be less developed and R&D endeavours less common (Hadjimanolis Citation2000; Van Uden, Knoben, and Vermeulen Citation2017). Experienced managers are also a scarcer resource compared to developed economies (Acquaah Citation2012), and thereby a more pivotal source of competitive disparity between firms. This leads to our following hypothesis:

H3:

The higher the level of industry-specific managerial experience the higher the likelihood that a firm will become innovative.

2.4. Managing where you are

In line with the above, we suggest that the effects of geographic conditions are moderated by managerial industry experience. There are risks to being in an agglomeration that could be magnified by low levels of such experience, and others that may be circumvented in part or entirely by experienced managers.

In terms of urbanisation, the challenge lies in effectively utilising the diverse, locally available knowledge, with previous research suggesting that high levels of absorptive capacity generated by strong internal resources help firms to do so (Hussler, Lorentz, and Rondé Citation2007; Cohen and Levinthal Citation1990). As managers gain industry experience, they will not only become more knowledgeable, but also enlarge and diversify their social networks, e.g. through chance meetings (Bell and Zaheer Citation2007). This can help them select relevant collaboration partners (Baum, Calabrese, and Silverman Citation2000), and to receive signals that allow them to hire job seekers with useful abilities and knowledge (Herstad, Sandven, and Ebersberger Citation2015). A similar argument could be made for localisation effects, although the absorption of external knowledge is less challenging when incumbent firms are active in similar industries (Speldekamp, Knoben, and Saka-Helmhout Citation2020). Instead, the core challenges likely lie in both breaking from the ‘strategic myopia’ that these environments foster, and selecting the right innovation partners (Pouder and St. John Citation1996; Knoben and Oerlemans Citation2012; Boschma, Eriksson, and Lindgren Citation2009). Regarding the first challenge, it is well-understood that firm managers’ image of their competitive environment is not only informed by their industry experience, but also by nearby competitors (McCann and Folta Citation2008). This increases the risk of isomorphism between firms, and with it the chance of lock-in (Martin and Sunley Citation2003). Past studies hint at ways in which firms can break from this. For instance, managers can spur the internal creation of knowledge (Visser and Atzema Citation2008), e.g. by restructuring project teams to foster information inefficiencies and with it knowledge heterogeneity (Funk Citation2014). It is similarly possible to engage in networks to access complementary knowledge (Knoben and Oerlemans Citation2012). However, this creates the challenge of selecting the right partners. There is the risk of opportunistic exploitation by collaborators, especially when they are competitors (Baum, Calabrese, and Silverman Citation2000) – a risk that is elevated under localisation (McCann and Folta Citation2008). Furthermore, building networks with co-located partners in the same industry may result in knowledge redundancy, and fail to boost innovation (ibid.; Huggins and Thompson Citation2014). Managers with extensive industry experience are likely better at handling these challenges. All in all, we hypothesise:

H4:

The level of industry-specific managerial experience amplifies the innovation-enhancing effect of urbanisation on firms.

H5:

The level of industry-specific managerial experience amplifies the innovation-enhancing effect of localisation on firms.

3. Data and methods

We tested our hypotheses using firm-level data derived from the World Bank (Citation2020) Enterprise Survey (ES), covering four South-East Asian countries: Cambodia, Vietnam, Timor-Leste and Thailand. For these countries data was collected in different years. Specifically, data was collected for Vietnam and Timor-Leste in 2014–2015 and for Thailand and Cambodia in 2016. All of these countries have been subject to rapid economic growth and technological change in the last decades (Chongvilaivan Citation2020), likely elevating the importance of managerial industry experience (Ettlie Citation1990; Kim and Lee Citation1987), and making them the ideal context for our study.

The World Bank (Citation2020) is experienced in conducting firm-level surveys, with its collection efforts having begun in the 1990s, and being standardised and centralised since 2005, ensuring data comparability across countries. Its ES contains representative data for firms in the manufacturing, retail, and service sector, and is stratified according to the geographic location, economic sector, and size of firms. The data is collected through private contractors who engage in face-to-face interviews with firm managers and business owners. The data used contains a total of 2,495 firms of which 2,123 firms report all data which we use in our analysis. Of these 2,123 firms, 302 were in Cambodia, 818 in Vietnam, 72 in Timor-Leste, and 931 in Thailand. This geographic imbalance occurs due to the World Bank typically interviewing 1,200 respondents in larger economies, around 360 in medium-sized economies, and about 150 in smaller economies.

3.1. Dependent variable

This study follows the OECD’s definition and measures firms’ innovative output in terms of product, service, and process innovation (OECD/Eurostat Citation2005). More precisely, respondents were asked whether a) their firm had introduced new or significantly improved products or services during the last three years, and b) whether this held true for processes (including methods of manufacturing, logistics, delivery or supporting activities). We combined the answers to these two questions, creating a dummy taking the value of ‘1’ when firms had innovated, and a ‘0’in all other cases – an approach shared by e.g. Ayyagari, Demirgüç-Kunt, and Maksimovic (Citation2011) and Barasa et al. (Citation2017). This measure is most suitable in our emerging market research context, where traditional measures such as patents are largely irrelevant, and relatively few firms, some 29% in our sample, innovate (Cirera and Muzi Citation2020). We conducted a robustness test to ensure that combining information regarding product and process innovation in one measure of firm innovativeness does not bias our results (see section 4.1).

3.2. Independent variables

3.2.1. Urbanisation

Since urbanisation is defined as the ‘sheer numbers and varieties of divisions of labour’ (Jacobs Citation1969, p. 59), we measured it through the size of the locality a firm is located in. This information is included in the ES data, which distinguishes between four categories: 1) cities with a population below 50,000, 2) between 50,000 and 250,000, 3) between 250,000 and 1 million, and 4) over 1 million.

Even though the relatively coarse measurement and categorical nature of this variable is a limitation for our analyses it also brings advantages. The size of the city a firm is located in is a commonly used operationalisation of urbanisation effects (Beaudry and Schiffauerova Citation2009). City size is often operationalised with the help of administrative data based on zoning systems. A downside of this method is that multiple zoning systems exist with cities often spanning multiple zones (Bosker, Park, and Roberts Citation2021). The choice of zoning system, and the level of aggregation thereof, can greatly influence the effects of agglomerations (Briant, Combes, and Lafourcade Citation2010). Because our firms answer this question directly, we do not have to rely on administrative units of measurement. On the other hand, differences in the interpretation of this question between respondents could introduce response bias. All in all, we believe the adopted measure is a good approximation of the local degree of urbanisation.

3.2.2. Localisation

To capture localisation, we used the fraction of industry employment in a region relative to the combined average across the four countries included in our study (e.g. a location quotient). The ES clarifies what region firms are in, their industry (over a total of 32 sectors), the total number of firms in each region and industry, and how many employees firms have.

For this measurement we rely on the sampling regions of the ES. For the four countries we study, the ES distinguishes 15 regions (5 in Cambodia, 5 in Thailand, 4 in Vietnam, and 1 in Timor-Leste). Importantly, these sampling regions are not administrative regions in the respective countries. Instead, the World Bank states that: ‘Geographic regions within a country are selected based on which cities/regions collectively contain the majority of economic activity’.Footnote1 In practice this implies that most regions are centred around a major city and incorporate the surrounding suburban and rural areas. This operationalisation actually comes very close to the best practice of measuring localisation effects at the level of the labour market region (Beaudry and Schiffauerova Citation2009).Footnote2 We would like to note that this measurement implies that urbanisation and localisation are measured at different spatial scales.

3.2.3. Managerial industry experience

Our measurement of managerial experience is industry-specific and defined as the number of years the top manager has worked in the firm’s sector. This information is contained within the ES data. As this variable was strongly skewed to the right, it was log-transformed.

3.3. Control variables

3.3.1. Firm size

As past research suggests that firm size positively affects innovation, we controlled for this (Vaona and Pianta Citation2008). Our measurement is the number of permanent full-time workers in the firm. As was the case for managerial industry experience, this variable was log-transformed due to right skewness.

3.3.2. Firm age

We also controlled for firm age, as it is generally negatively associated with innovation (Huergo and Jaumandreu Citation2004). The ES asks respondents in which year their firm was established, which we subtracted from the year 2020. The resulting variable was right-skewed and therefore log-transformed.

3.3.3. Formal R&D

With formal R&D being a well-established method of both pursuing innovation and enhancing the absorption of external knowledge (Cohen and Levinthal Citation1989; Griffith, Redding, and Van Reenen Citation2004; Carlino and Kerr Citation2015), we accounted for its presence in our analysis through a dummy variable. The ES asks respondents if, during the last three years, the establishment has spent resources on formal R&D activities. If this was true, a value of ‘1’ was assigned. If this was false, this was ‘0’.

3.3.4. Formal training

When firms invest in training their employees, it increases their general skills and abilities, and promotes learning and innovation (Van Uden, Knoben, and Vermeulen Citation2017). We therefore controlled for the presence of formal training programs via a dummy. In the ES, respondents are asked whether such programs exist for permanent, full-time employees in the last fiscal year.

3.3.5. Informal competition

When firms compete with informal organisations, this can have a negative effect on their performance by increasing environmental uncertainty and complexity (Van Uden, Vermeulen, and Knoben Citation2019). Such informal organisations are not registered, do not pay taxes, often employ undocumented workers, and do not face the same regulatory constraints (Webb et al. Citation2013). As the ES asks respondents whether ‘practices of competitors in the informal sector were an obstacle to the current operations of this establishment,’ we were able to construct a dummy variable. A value of ‘1’ indicated that there was informal competition impeding a firm, and ‘0’ denoted that this was not the case.

3.3.6. Employee schooling

To further capture firm-level differences in human capital beyond formal training we also control for the level of schooling of the employees of a firm. Following Van Uden, Knoben, and Vermeulen (Citation2017) we used the measure in the ES that captures the percentage of employees that has finished at least high school.

3.3.7. Female manager

Earlier research has shown the relevance of a manager’s gender for firm-level innovation in developing countries (Ritter-Hayashi, Vermeulen, and Knoben Citation2019), and it is likely that gender also influences the industry experience of managers. Therefore, we control for the gender of the manager with a dummy variable that takes the value ‘1’ in case the manager is female and ‘0’ otherwise.

3.3.8. Managerial firm experience

To ensure that our managerial industry experience truly captures industry experience, we control for the firm-level experience of the manager. We do so by utilising the information in the ES regarding the respondent. In total, a maximum of three respondents to the survey can be listed. For each, their position in the firm and the time that the respondent has been with the firm is provided. From the respondents we identified the most senior manager (e.g. CEO, owner/manager) and took the time that respondent has been with the firm as our measure of managerial firm experience.

3.3.9. Country effects

Finally, country-level differences were controlled with dummy variables. These pertained to each country, with Vietnam being used as the reference.

3.4. Estimation technique

Given the binary nature of our dependent variable, we used logistic regressions to analyse our data. As these regressions combined region and firm-level measures, we clustered the standard errors at the regional level, thus accounting for the violated assumption of independence in our observations – an approach commonly used in this type of analysis (Barasa et al. Citation2017). This approach was chosen over a multilevel estimation, given the relatively small number of regions under study (15) to which multilevel regression is rather sensitive. However, we did conduct such an analysis as a robustness test (see section 4.1).

4. Results

depicts the descriptive statistics of the variables included in our analysis. It details that 29% of the firms in our sample innovated in the period under study. There is significant variation across all our measures, and their correlations are relatively low – evidencing there are no collinearity issues.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

4.1. Main findings

presents the results of our four main regression models. It reports the odds-ratios, where numbers larger than 1 imply positive relations with the likelihood of firm innovation whereas numbers smaller than 1 imply negative ones. The first model includes only the control variables and serves as a benchmark to compare the other models against. The second model incorporates the main effects of urbanisation, localisation, and managerial industry experience. The third and final model adds the interaction effects of localisation and urbanisation with managerial industry experience and forms the focus of our analysis. Comparing the model fit across shows clear evidence that the inclusion of our main and moderation effects improves the models (increased LR Chi2 test values) and their explanatory power (increased McFadden’s pseudo R-squared). Sensitivity and specificity tests reveal that the increase in model fit is mostly due to increases in the correct prediction of innovative firms.

Table 2. Binary logistic regression models of a firm’s innovative output.

Most of the control variables have the expected, positive relation with firm innovation. Larger firms have higher likelihoods of being innovative. The same holds true for firms that perform formal R&D, face more informal competition, offer formal training to their staff, have a female CEO, and have a manager with more firm-level experience.

Above and beyond the influence of our control variables, the first and second hypotheses predict a positive relation between the level of urbanisation (H1) and localisation (H2), and firms’ innovative output. We find strong evidence for hypothesis 1. Urbanisation has a relatively large and positive relation with innovation in all models. Marginal effect analyses show that the magnitude of the relation is such that while in an area of the lowest level of urbanisation the likelihood that firms are innovative is 20.2%, this increases to respectively 27.4%, 30.4% and 30.8% for the subsequent categories of urbanisation.

However, our results contradict hypothesis 2. Localisation (geographic specialisation) has a negative relation with a firms’ innovative output in all models. Marginal effect analyses show that whereas the likelihood of a firm being innovative is 32.4% in the least localised region, every one unit increase in localisation decreases this likelihood with approximately 1.4%-points.

The third hypothesis predicts that managerial industry experience has a positive relation with firm-level innovation. We confirm this relation in model 2, though the statistical significance is relatively weak. Marginal effect analyses show that a one standard deviation increase in a top manager’s industry experience leads to a 3.5%-point increase in the likelihood that a firm is innovative. Beyond its direct effect, the strong moderation effects of managerial industry experience with both urbanisation and localisation underlines that industry experience is very important for firm innovativeness. However, in some contexts there is a positive relation with firm innovation, whereas it is negative one in others.

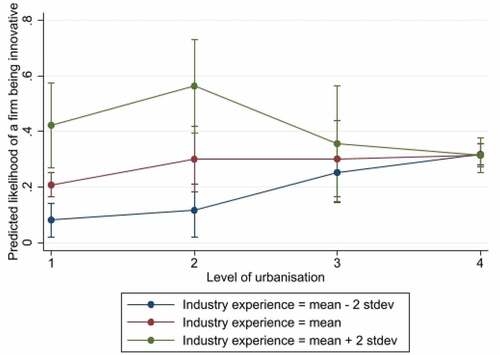

In hypothesis 4 we suggested that managerial industry experience positively moderates the relation between urbanisation and firm innovation. Contrary to this expectation, we find a large and highly statistically significant negative moderation effect. This negative effect implies that the relation between urbanisation and firm innovation diminishes as managerial industry experience increases. To provide further insights into the magnitude of this moderation, we plot the relation between the degree of urbanisation and the predicted likelihood of a firm being innovative at three different levels of managerial industry experience in . In this graph we follow the best-practice of depicting the mean predicted likelihood of a firm being innovative across the relevant combinations of independent variables (Bowen and Wiersema Citation2004).

shows that firms located in the most rural areas (i.e. population less than 50.000), and with relatively inexperienced managers (i.e. 5 years of industry experience), are innovative in under 10% of the cases. However, when firms in such areas have relatively experienced managers, their likelihood of being innovative increases sharply. For firms with a top manager whose industry experience is more than two standard deviations above the mean (i.e. 38 years of industry experience), this increases to almost 45%. In other words, being in a rural area is very detrimental to a firm’s likelihood of being innovative unless they have an industry experienced manager. We find a very similar pattern for firms in the second category of urbanisation (i.e. located in a city with a population between 50.000 and 250.000).

As we move to more urbanised areas (i.e. urbanisation category 3 and 4), the base likelihood of a firm being innovative goes up but the benefits of having a manager with high levels of industry experience diminishes. In both urbanisation categories, the likelihood of firms innovating is statistically the same for firms with managers with high, medium, or low industry experience. Taken together with the results discussed in the previous paragraph, this suggests that a firm’s location (being either highly urbanised or not) affects the importance of managerial experience. Firms located in urbanised areas could maintain an inexperienced manager with seemingly a minimal impact on innovation, while having an inexperienced manager can be detrimental for firms located in rural areas.

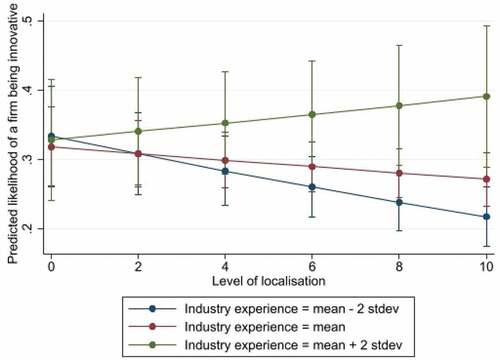

The fifth hypothesis proposes that managerial experience positively moderates localisation’s impact on innovation. This hypothesis is confirmed. Taken together with our finding that, by itself, localisation has a negative influence on firm innovation, this means that industry experienced managers can exploit the external benefits that localisation provides while sufficiently dampening its concomitant negative effects. In other words, such managers can identify environmental opportunities, improving firms’ innovative capacity. They may, for instance, be able to identify potential partnerships with local firms. At the same time, they could be better able to cope with high levels of local competition and the risks associated with knowledge leakage.

To gain further insight into the magnitude of this moderation, plots the relation between the degree of localisation and the predicted likelihood of a firm being innovative at three different levels of managerial industry experience. For areas characterised by very low localisation scores, the level of managerial industry experience has little to no impact. However, the more specialised a region becomes, the greater the association. For low and medium levels of managerial industry experience the relation between localisation and firm innovation is negative. A high level of managerial industry experience, on the other hand, can turn this negative relation into a positive one. The relation between localisation and innovation transitions from negative to positive at approximately 29 years. Even though this is a very high level of industry experience, 10% of our observations are above this threshold making it an empirically relevant finding.

4.2. Robustness tests and endogeneity concerns

We performed several robustness tests to assess the sensitivity of our results to different model specifications and to address potential endogeneity concerns. First, as with most observational studies, potential endogeneity concerns loom in our study. We expect the potential bias due to endogeneity to be relatively small with regard to both urbanisation and localisation effects. Firms mostly select their initial location based on the place of residence of the founder and subsequently tend to stay in their region of origin, even when growing rapidly (Knoben Citation2011; Stam Citation2007). Endogeneity is still likely to play some role, for example due to spin-off dynamics (Niebuhr, Peters, and Schmidke Citation2020), but given that the majority of our firms are low-tech SMEs we expect such effects to be minor. Endogeneity is more likely to be an issue, however, with regard to managerial industry experience. For example, it seems plausible that more innovative firms are able to attract more experienced managers. On the other hand, young and innovative start-ups are more likely to be characterised by relatively young and inexperienced managers. Given the cross-sectional nature of our data and the lack of suitable exogenous instrumental variables for managerial industry experience in our dataset, the capacity to deal with such concerns is limited. To account for endogeneity to the extent possible, we estimated several propensity score matched models. These techniques aim to extract ‘treatment effects’ from observational data (Guo and Fraser Citation2015). In our case, the treatment we constructed is captured by a dummy variable that reflects whether a firm has an above-average industry experienced manager (i.e. >18 years). Every firm receiving this ‘treatment’ was matched to 4 other firms that are as similar as possible on all observed covariates (including regional and industry characteristics), but that did not ‘receive’ the treatment (Caliendo and Kopeinig Citation2008). To assess whether the effect of the treatment depended on the level of urbanisation and localisation we used a median-split sample approach for both regional level variables.

The results of these analyses are fully in-line with our main findings. The effect of having a highly industry experienced manager is positive in low urbanisation areas (average treatment effect (ATE) of 0.14, p < 0.05) and negative in high urbanisation areas (ATE = −0.09, p < 0.05). Conversely, the effect of having a highly industry experienced manager is negative but statistically insignificant in low localisation areas (ATE = −0.03, p > 0.10) and positive and statistically significant in high localisation areas (ATE = 0.21, p < 0.05). Even though we acknowledge that such analyses do not allow for a clean identification of a causal effect, they help ameliorate concerns about endogeneity driving our results.

Second, an important limitation of our paper is that omitted variables at the level of the manager (like managerial education or age) could drive the moderation effects we have uncovered. Of these, managerial age is of primary concern because age directly drives managerial industry experience. Fortunately, controlling for managerial firm experience also allows us to (partially) control for manager’s age. If age is the critical component of managerial industry experience, we would expect to find similar (moderation) effects for managerial firm experience as we did for managerial industry experience. We test for this in an additional analysis and find no significant moderation for managerial firm experience, thereby reducing concerns that our effects are driven by the omission of managerial age.Footnote3

With regard to the more general robustness of our results, estimating multilevel models (i.e. hierarchical linear models) with cross-level interaction terms is a viable alternative to our main model specification (see section 3.4). We estimated such models, and the results thereof are reported in (model R1). The results reported in model R1 are nearly identical to those reported in (model 3).

Table 3. Results of robustness tests.

To rule out that our results are driven by the inclusion of observations capturing specific ‘outlier’ firm/region observations, we re-ran our models using a bootstrapping method. Specifically, we ran 100 iterations of our model with each randomly sampling roughly 50% of our observations. Again, we found near-identical results as in our main regression models (cf. model R2 in and model 3 in ).

Finally, as discussed in section 3.1, we combine information regarding product and process innovation in our dependent variable. In ’s model R3 and R4 we re-run our analyses separately for these two types of innovation. These analyses yield results that are very similar to those reported for our combined measure of firm innovativeness (, model 3). Overall, the relations between urbanisation, localisation and firm innovation are more pronounced for process innovation than for product innovation. Specifically, model R4 does reveal that the relation between localisation and innovation is mostly driven by process innovation, but the direction of the relation is the same for product innovation.

5. Discussion

Our paper investigated the relations that urbanisation, localisation, and managerial industry experience have with firm-level innovation, as well as their interactions. We confirm that the impact of agglomeration economies is strongly shaped by managerial industry experience, although the interaction is not always as we anticipated in our theoretical framework. Interestingly, managerial industry experience negatively moderates the relation between urbanisation and innovation. However, this effect is small, and overshadowed by our finding that in less urbanised environments firms with an experienced top manager are far more likely to innovate. In the most rural localities over 40% of these firms innovate, whereas those with an inexperienced manager almost never do. For localisation the interaction is positive, turning a negative effect into a beneficial one when managers have been in the industry for at least 29 years. About one-tenth of the firms in our sample meet this criterion and it is therefore highly relevant. For such firms, innovative output increases as agglomerations become more specialised. All in all, these findings point to the critical role of firm-level idiosyncrasies – a matter which most of the agglomeration literature has ignored (Rutten Citation2014). Put differently, firm location matters, but given that the same location can be beneficial and detrimental to firm innovativeness it is critical for firms to manage where they are.

5.1. Theoretical implications

With these results, our paper sheds light on the contentious findings of agglomeration economies (Frenken, Cefis, and Stam Citation2015; Beaudry and Schiffauerova Citation2009). When firm-level characteristics such as the experience of top managers are not considered only a partial understanding of how agglomerations affect firm-level innovation is possible. This, for instance, leaves firms able to benefit from localisation due to having experienced managers bunched together with those who suffer negative consequences. Depending on how balanced the sample under study is, this can skew the results for localisation to being negative, positive, or insignificant. This is not to say that our study definitively resolves the enduring contention in the literature, but rather that considering firm-level idiosyncrasies, and more specifically managerial industry experience, is a piece of the puzzle that helps solve it. We thereby answer calls from e.g. Frenken, Cefis, and Stam (Citation2015) to further our understanding of firm-level heterogeneity and establish the need to uncover the mechanisms by which knowledge is transferred within agglomerations.

Furthermore, with few studies investigating the effects of agglomeration outside the developed economies (Duranton Citation2015; Resbeut, Gugler, and Charoen Citation2019), our paper opens a window to understanding how these differ from emerging market contexts. It is of note that, independently, localisation had a negative effect on innovation in our research context of four South-East Asian countries, whereas this has generally been positive in more developed economies (Beaudry and Schiffauerova Citation2009). A straightforward explanation is that, due to fewer intellectual property protections than in developed countries (Kanwar and Evenson Citation2009), and a lower rate at which South-East Asian firms legally protect their knowledge (MacDonald and Turpin Citation2007, Citation2008), firms suffer more from leaking their know-how to competitors. That this also creates opportunities to use external knowledge should be clear, as firm-level innovation increases with localisation when managers are experienced in their industry.

5.2. Practical implications

Our findings carry practical implications for firms in South-East Asian countries. Most importantly, for innovation firms may want to match their top management to environmental characteristics. Under most environmental conditions it matters greatly how industry experienced top managers are. For instance, firms in rural areas, i.e. with the lowest level of urbanisation, almost never innovate unless their managers are very industry experienced. This importance diminishes as the level of urbanisation increases, disappearing almost entirely for firms in the most urbanised regions. This is mirrored in localised regions where the association between industry experience and innovation becomes noticeably stronger as regions become more localised. Although our analyses do not allow for causal inference in this regard, we conjecture that this relation corresponds to more experienced managers generally better leveraging the opportunities afforded by highly localised regions while circumventing or otherwise diminishing their negative effects such as knowledge leakage. In other words, we expect that for firms wanting to innovate in rural or highly specialised regions having highly industry experienced top managers matters, while it matters little if their environment is highly urbanised or unspecialised.

In addition, our study carries policy relevance. To enable innovation and economic growth governments frequently stimulate regional specialisation, for example by establishing and supporting business incubators and science parks to facilitate high-potential entrepreneurship (Bradley et al. Citation2021). Our paper casts doubt on whether such specialisation-based policies are universally beneficial. Given that the geographic concentration of firms in the same industry can have negative innovation impacts for firms with relatively inexperienced managers, policy makers should be cautious about stimulating such localisation. This especially holds when these policies rely heavily on stimulating entrepreneurship as such firms often have relatively inexperienced managers.

5.3. Directions for future research

These contributions notwithstanding, there still is a great need to further unpick the mechanisms by which firms source knowledge and other resources from their environment. For example, although our work elucidates the influence of agglomeration economies and managerial industry experience in the developing world, this leaves the question of how our findings translate to firms in developed countries. We have already given hints as to how we expect results to differ, with localisation, in general, carrying fewer risks the more developed a regional context and its institutions are. However, the opposite may also hold true, with the role of intellectual property being limited further away from the technological frontier (Cirera and Muzi Citation2020), and firms in developed contexts facing significant challenges due to rapid technological change (Mullins and Sutherland Citation1998). Similarly, the overall level of development likely alters both the independent and indirect effects of managerial industry experience. Past research demonstrates that the stronger institutions are, the less managerial industry experience elevates innovation performance (Balsmeier and Czarnitzki Citation2014). Yet, knowledge is by definition non-rival, imperfectly excludable, and not fully appropriable (Samaniego Citation2013). Hence, risks of knowledge leakage remain even in developed contexts (Ritala et al. Citation2015), and some managers may be better able to navigate or even use them to benefit their firm (Hannah, McCarthy, and Kietzmann Citation2015). Future research may elucidate which of these arguments holds true, and under what conditions.

Second, our study has not investigated how different types of innovation, ranging from incremental to radical, and frugal to value-oriented, are generated – this despite the fact that they have different antecedents and carry different risks (e.g. Agnihotri Citation2015). To illustrate, when firms in developing contexts are pushed to innovate due to internal resource constraints, and seek to enhance the efficiency by which their products and services are produced, managerial experience is greatly beneficial (Ploeg et al. Citation2020). However, there are indications that when the goal is offering affordable and resource-efficient products and services for customers, experience becomes detrimental as such managers tend to be less entrepreneurial (ibid.). Future studies could seek to verify and extend this and relate its effects to those of agglomeration economies that may exacerbate both the threats and opportunities firms face in their innovation efforts.

Finally, there is the need to further research the transfer processes and mechanisms by which knowledge is shared between agglomerated firms for innovation, and how, exactly, managers intervene. As with other agglomeration research, we do not trace these processes and only imply their presence, as we lack the detailed within-case knowledge necessary to do so. Qualitative research could investigate how managers change their actions under certain environmental conditions, e.g. by changing who they hire, how they engage with collaborative partners and at what geographic distance. Such research may additionally be able to disentangle the effects of further types of experience, e.g. at the regional level (Barasa et al. Citation2017). Intimate knowledge about firms’ development and hiring procedures could similarly give closure regarding the possible endogeneity problems underlying our analyses, most crucially whether more innovative firms attract more experienced managers. All in all, future research with more detailed case knowledge could elucidate why, under certain conditions, managerial industry experience matters more for innovation than in others and provide a clearer picture of the causal mechanisms and idiosyncrasies at play.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

2 The most common way of operationalising localisation compares the share of industry employment in a region against the national share (Beaudry and Schiffauerova Citation2009, p. 322). However, as Timor-Leste consists of just one region, we deviated from this practice and instead compared to the share across our four countries of study. We performed an additional (robustness) analysis with a measure based on national shares (and therefore excluding Timor-Leste) and obtained nearly identical results. We are therefore confident that this choice did not influence or bias our results.

3 Results available from the authors on request.

References

- Acquaah, M. 2012. “Social Networking Relationships, Firm-Specific Managerial Experience and Firm Performance in a Transition Economy: A Comparative Analysis of Family Owned and Nonfamily Firms.” Strategic Management Journal 33 (10): 1215–1228. doi:10.1002/smj.

- Agnihotri, A. 2015. “Low-Cost Innovation in Emerging Markets.” Journal of Strategic Marketing 23 (5): 399–411. doi:10.1080/0965254X.2014.970215.

- Ayyagari, M., A. Demirgüç-Kunt, and V. Maksimovic. 2011. “Firm Innovation in Emerging Markets: The Role of Finance, Governance, and Competition.” The Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 46 (6): 1545–1580. doi:10.1017/S0022109011000378.

- Balsmeier, B., and D. Czarnitzki. 2014. “How Important is Industry-Specific Managerial Experience for Innovative Firm Performance?” ZEW-Centre for European Economic Research Discussion Paper 14-011. 10.2139/ssrn.2387549.

- Bantel, K. A., and S. E. Jackson. 1989. “Top Management and Innovations in Banking: Does the Composition of the Top Team Make a Difference?” Strategic Management Journal 10: 107–124. doi:10.1002/smj.4250100709.

- Barasa, L., J. Knoben, P. A. M. Vermeulen, P. Kimuyu, and B. Kinyanjui. 2017. “Institutions, Resources and Innovation in East Africa: A Firm Level Approach.” Research Policy 46 (1): 280–291. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2016.11.008.

- Bathelt, H., A. Malmberg, and P. Maskell. 2004. “Clusters and Knowledge: Local Buzz, Global Pipelines and the Process of Knowledge Creation.” Progress in Human Geography 28 (1): 31–56. doi:10.1191/0309132504ph469oa.

- Baum, J. A. C., T. Calabrese, and B. S. Silverman. 2000. “Don’t Go It Alone: Alliance Network Composition and Startups’ Performance in Canadian Biotechnology.” Strategic Management Journal 21 (3): 267–294. doi:10.1002/smj.233.

- Beaudry, C., and A. Schiffauerova. 2009. “Who’s Right, Marshall or Jacobs? The Localization versus Urbanization Debate.” Research Policy 38 (2): 318–337. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2008.11.010.

- Becker, G. S. 1993. Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education. 3rd ed. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Bell, G. G., and A. Zaheer. 2007. “Geography, Networks, and Knowledge Flow.” Organization Science 18 (6): 955–972. doi:10.1287/orsc.1070.0308.

- Boschma, R., R. Eriksson, and U. Lindgren. 2009. “How Does Labour Mobility Affect the Performance of Plants? The Importance of Relatedness and Geographical Proximity.” Journal of Economic Geography 9 (2): 169–190. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbn041.

- Bosker, M., J. Park, and M. Roberts. 2021. “Definition Matters. Metropolitan Areas and Agglomeration Economies in a Large-Developing Country.” Journal of Urban Economics 125: 103275. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2020.103275.

- Bowen, H. P., and M. F. Wiersema. 2004. “Modeling Limited Dependent Variables: Methods and Guidelines for Researchers in Strategic Management.” Research Methodology in Strategy and Management 1: 87–134.

- Bradley, S. W., P. H. Kim, P. G. Klein, J. S. McMullen, and K. Wennberg. 2021. “Policy for Innovative Entrepreneurship: Institutions, Interventions, and Societal Challenges.” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 15 (2): 167–184. doi:10.1002/sej.1395.

- Breschi, S. 2000. “The Geography of Innovation: A Cross-Sector Analysis.” Regional Studies 34 (3): 213–229. doi:10.1080/00343400050015069.

- Briant, A., P. P. Combes, and M. Lafourcade. 2010. “Dots to Boxes: Do the Size and Shape of Spatial Units Jeopardize Economic Geography Estimations?” Journal of Urban Economics 67: 287–302. doi:10.1016/j.jue.2009.09.014.

- Cainelli, G., R. Evangelista, and M. Savona. 2006. “Innovation and Economic Performance in Services: A Firm-Level Analysis.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 30 (3): 435–458. doi:10.1093/cje/bei067.

- Caliendo, M., and S. Kopeinig. 2008. “Some Practical Guidance for the Implementation of Propensity Score Matching.” Journal of Economic Surveys 22 (1): 31–72. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6419.2007.00527.x.

- Cantwell, J. 2005. “Innovation and Competitiveness.” In The Oxford Handbook of Innovation, edited by J. Fagerberg, D. C. Mowery, and R. R. Nelson, 543–567. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Capozza, C., and M. Divella. 2019. “Human Capital and Firms’ Innovation: Evidence from Emerging Economies.” Economics of Innovation and New Technology 28 (7): 741–757. doi:10.1080/10438599.2018.1557426.

- Carlino, G., and W. R. Kerr. 2015. ”Agglomeration and Innovation.” In Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics, edited by G. Duranton, J. V. Henderson, W. C. Strange, G. Duranton, J. V. Henderson, and W. C. Strange 349–404. Amsterdam: Elsevier. DOI:10.1016/B978-0-444-59517-1.00006-4.

- Chongvilaivan, A. 2020. “Openness and Inclusive Growth in South-East Asia.” In Achieving Inclusive Growth in the Asia Pacific, edited by A. Triggs and S. Urata, 87–102. Canberra: Australian National University Press.

- Cirera, X., and S. Muzi. 2020. “Measuring Innovation Using Firm-Level Surveys: Evidence from Developing Countries.” Research Policy 49 (3): 103912. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2019.103912.

- Cohen, W. M., and D. A. Levinthal. 1989. “Innovation and Learning: The Two Faces of R&D.” The Economic Journal 99 (397): 569–596. doi:10.2307/2233763.

- Cohen, W. M., and D. A. Levinthal. 1990. “Absorptive Capacity: A New Perspective on Learning and Innovation.” Administrative Science Quarterly 35 (1): 128–152. doi:10.2307/2393553.

- Crowley, F., and J. Bourke. 2018. “The Influence of the Manager on Firm Innovation in Emerging Economies.” International Journal of Innovation Management 22 (3): 1203–1221. doi:10.1080/00036846.2017.1355543.

- Custódio, C., M. A. Ferreira, and P. Matosc. 2019. “Do General Managerial Skills Spur Innovation?” Management Science 65 (2): 459–476. doi:10.1287/mnsc.2017.2828.

- Dodgson, M. 2000. “Innovation: Why We Need to Risk It.” R & D Enterprise: Asia Pacific 3 (1–2): 33–36. doi:10.5172/impp.2000.3.1-2.33.

- Duranton, G. 2015. “Growing Through Cities in Developing Countries.” The World Bank Research Observer 30 (1): 39–73. doi:10.1093/wbro/lku006.

- Eisenhardt, K. M., and J. A. Martin. 2000. “Dynamic Capabilities.” Strategic Management Journal 21: 1105–1121. doi:10.1108/ebr-03-2018-0060.

- Ettlie, J. E. 1990. “What Makes a Manufacturing Firm Innovative?” Academy of Management Perspectives 4 (4): 7–20. doi:10.5465/ame.1990.4277195.

- Feldman, M. P. 1999. “The New Economics of Innovation, Spillovers and Agglomeration: A Review of Empirical Studies.” Economics of Innovation and New Technology 8 (1–2): 5–25. doi:10.1080/10438599900000002.

- Florida, R., P. Adler, and C. Mellander. 2017. “The City as Innovation Machine.” Regional Studies 51 (1): 86–96. doi:10.1080/00343404.2016.1255324.

- Folta, T. B., A. C. Cooper, and Y. S. Baik. 2006. “Geographic Cluster Size and Firm Performance.” Journal of Business Venturing 21 (2): 217–242. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.04.005.

- Frenken, K., E. Cefis, and E. Stam. 2015. “Industrial Dynamics and Clusters: A Survey.” Regional Studies 49 (1): 10–27. doi:10.1080/00343404.2014.904505.

- Fritsch, M., M. Kudic, and A. Pyka. 2019. “Evolution and Co-Evolution of Regional Innovation Processes.” Regional Studies 53 (9): 1235–1239. doi:10.1080/00343404.2019.1627306.

- Funk, R. J. 2014. “Making the Most of Where You Are: Geography, Networks, and Innovation in Organizations.” Academy of Management Journal 57 (1): 193–222. doi:10.5465/amj.2012.0585.

- Glaeser, E. L., H. D. Kallal, J. A. Scheinkman, and A. Shleifer. 1992. “Growth in Cities.” The Journal of Political Economy 100 (6): 1126–1152. doi:10.1086/261856.

- Griffith, R., S. Redding, and J. Van Reenen. 2004. “Mapping the Two Faces of R&D: Productivity Growth in a Panel of OECD Industries.” The Review of Economics and Statistics 86 (4): 883–895. doi:10.1162/0034653043125194.

- Grillitsch, M., and M. Nilsson. 2017. “Firm Performance in the Periphery: On the Relation Between Firm-Internal Knowledge and Local Knowledge Spillovers.” Regional Studies 51 (8): 1219–1231. doi:10.1080/00343404.2016.1175554.

- Grillitsch, M., and M. Nilsson. 2019. “Knowledge Externalities and Firm Heterogeneity: Effects on High and Low Growth Firms.” Papers in Regional Science, Papers in Innovation Studies, Papers in Innovation Studies 98 (1): 93–114. doi:10.1111/pirs.12342.

- Guo, S., and M. W. Fraser. 2015. Propensity Score Analysis: Statistical Methods and Applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

- Hadjimanolis, A. 2000. “An Investigation of Innovation Antecedents in Small Firms in the Context of a Small Developing Country.” R & D Management 30 (3): 235–246. doi:10.1111/1467-9310.00174.

- Hannah, D. R., I. P. McCarthy, and J. Kietzmann. 2015. “We’re Leaking, and Everything’s Fine: How and Why Companies Deliberately Leak Secrets.” Business Horizons 58 (6): 659–667. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2015.07.003.

- Herstad, S. J., T. Sandven, and B. Ebersberger. 2015. “Recruitment, Knowledge Integration and Modes of Innovation.” Research Policy 44 (1): 138–153. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2014.06.007.

- Herstad, S. J., M. C. W. Solheim, and M. Engen. 2019. “Learning Through Urban Labour Pools: Collected Worker Experiences and Innovation in Services.” Environment & Planning A 51 (8): 1720–1740. doi:10.1177/0308518X19865550.

- Hervás-Oliver, J. L., and J. Albors-Garrigós. 2007. “Do Clusters Capabilities Matter? An Empirical Application of the Resource-Based View in Clusters.” Entrepreneurship and Regional Development 19 (2): 113–136. doi:10.1080/08985620601137554.

- Hervas-Oliver, J. L., F. Sempere-Ripoll, and C. Boronat-Moll. 2014. “Process Innovation Strategy in SMEs, Organizational Innovation and Performance: A Misleading Debate?” Small Business Economics 43 (4): 873–886. doi:10.1007/s11187-014-9567-3.

- Hervas-Oliver, J. L., F. Sempere-Ripoll, R. Rojas Alvarado, and S. Estelles-Miguel. 2018. “Agglomerations and Firm Performance: Who Benefits and How Much?” Regional Studies 52 (3): 338–349. doi:10.1080/00343404.2017.1297895.

- Huergo, E., and J. Jaumandreu. 2004. “How Does Probability of Innovation Change with Firm Age?” Small Business Economics 22 (3–4): 193–207. doi:10.1023/b:sbej.0000022220.07366.b5.

- Huggins, R., and P. Thompson. 2014. “A Network-Based View of Regional Growth.” Journal of Economic Geography 14 (3): 511–545. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbt012.

- Hussler, C., A. Lorentz, and P. Rondé. 2007. “Agglomeration and Endogenous Absorptive Capacities: Hotelling Revisited.” Jena Economic Research Papers No. 2007.102. Friedrich Schiller University Jena and Max Planck Institute of Economics, Jena.

- Jacobs, J. 1969. The Economy of Cities. New York: Random House.

- Kanwar, S., and R. Evenson. 2009. “On the Strength of Intellectual Property Protection That Nations Provide.” Journal of Development Economics 90 (1): 50–56. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2008.11.006.

- Kim, L., and H. Lee. 1987. “Patterns of Technological Change in a Rapidly Developing Country: A Synthesis.” Technovation 6 (4): 261–276. doi:10.1016/0166-4972(87)90074-5.

- Knoben, J. 2011. “The Geographic Distance of Relocation Search: An Extended Resource-Based Perspective.” Economic Geography 87 (4): 371–392. doi:10.1111/j.1944-8287.2011.01123.x.

- Knoben, J., A. T. Arikan, F. Van Oort, and O. Raspe. 2016. “Agglomeration and Firm Performance: One Firm’s Medicine is Another Firm’s Poison.” Environment & Planning A 48 (1): 132–153. doi:10.1177/0308518X15602898.

- Knoben, J., and L. A. G. Oerlemans. 2012. “Configurations of Inter-Organizational Knowledge Links: Does Spatial Embeddedness Still Matter?” Regional Studies 46 (8): 1005–1021. doi:10.1080/00343404.2011.600302.

- Krugman, P. 1991. “Increasing Returns and Economic Geography.” The Journal of Political Economy 99 (3): 483–499. doi:10.1086/261763.

- Lorenzen, M., and L. Frederiksen. 2007. “Why Do Cultural Industries Cluster? Localization, Urbanization, Products and Projects.” Creative Cities, Cultural Clusters and Local Economic Development 2 (3): 155–179. doi:10.4337/9781847209948.00015.

- Louf, R., and M. Barthelemy. 2014. “How Congestion Shapes Cities: From Mobility Patterns to Scaling.” Scientific Reports 4 (1): 1–9. doi:10.1038/srep05561.

- Love, J. H., and S. Roper. 2015. “SME Innovation, Exporting and Growth: A Review of Existing Evidence.” International Small Business Journal 33 (1): 28–48. doi:10.1177/0266242614550190.

- MacDonald, S., and T. Turpin. 2007. “Technology Transfer and IPR Policy for Small and Medium Firms in South-East Asia.” Prometheus (United Kingdom) 25 (4): 363–372. doi:10.1080/08109020701689201.

- MacDonald, S., and T. Turpin. 2008. “Intellectual Property Rights and SMEs in South-East Asia: Innovation Policy and Innovation Practice.” International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management 5 (2): 233–246. doi:10.1142/S0219877008001357.

- Marshall, A. 18901920. Principles of Economics. 8th ed. London: Macmillan and Co. doi:10.1007/s13398-014-0173-7.2.

- Martin, R. 2015. “Rebalancing the Spatial Economy: The Challenge for Regional Theory.” Territory, Politics, Governance 3 (3): 235–272. doi:10.1080/21622671.2015.1064825.

- Martin, R., and P. Sunley. 2003. “Deconstructing Clusters: Chaotic Concept or Policy Panacea?” Journal of Economic Geography 3: 5–35. doi:10.1093/jeg/3.1.5.

- Mayer, K. J., D. Somaya, and I. O. Williamson. 2012. “Firm-Specific, Industry-Specific, and Occupational Human Capital and the Sourcing of Knowledge Work.” Organization Science 23 (5): 1311–1329. doi:10.1287/orsc.1110.0722.

- McCann, B. T., and T. B. Folta. 2008. “Location Matters: Where We Have Been and Where We Might Go in Agglomeration Research.” Journal of Management 34 (3): 532–565. doi:10.1177/0149206308316057.

- McCann, B. T., and T. B. Folta. 2011. “Performance Differentials Within Geographic Clusters.” Journal of Business Venturing 26 (1): 104–123. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.04.004.

- Menzel, M. P., and D. Fornahl. 2010. “Cluster Life Cycles-Dimensions and Rationales of Cluster Evolution.” Industrial and Corporate Change 19 (1): 205–238. doi:10.1093/icc/dtp036.

- Mullins, J. W., and D. J. Sutherland. 1998. “New Product Development in Rapidly Changing Markets: An Exploratory Study.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 15 (3): 224–236. doi:10.1111/1540-5885.1530224.

- Naz, A., A. Niebuhr, and J. C. Peters. 2015. “What’s Behind the Disparities in Firm Innovation Rates Across Regions? Evidence on Composition and Context Effects.” The Annals of Regional Science 55 (1): 131–156. doi:10.1007/s00168-015-0694-9.

- Niebuhr, A., J. C. Peters, and A. Schmidke. 2020. “Spatial Sorting of Innovative Firms and Heterogeneous Effects of Agglomeration on Innovation in Germany.” The Journal of Technology Transfer 45: 1343–1375. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-019-09755-8.

- OECD/Eurostat. 2005. Oslo Manual: The Measurement of Scientific and Technological Activities - Proposed Guideline for Collecting and Interpreting Technological Innovation Data. 3rd ed. Paris: Organisation for Economic Cooporation and Development.

- Ooms, W., C. Werker, M. C. J. Caniëls, and H. Van Den Bosch. 2015. “Research Orientation and Agglomeration: Can Every Region Become a Silicon Valley?” Technovation 45–46: 78–92. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2015.08.001.

- Peteraf, M. A. 1993. “The Cornerstones of Competitive Advantage: A Resource-Based View.” Strategic Management Journal 14 (3): 179–191. doi:10.1002/smj.4250140303.

- Phelps, N. A., M. Atienza, and M. Arias. 2018. “An Invitation to the Dark Side of Economic Geography.” Environment & Planning A 50 (1): 236–244. doi:10.1177/0308518X17739007.

- Ploeg, M., J. Knoben, P. A. M. Vermeulen, and C. van Beers. 2020. “Rare Gems or Mundane Practice? Resource Constraints as Drivers of Frugal Innovation.” Innovation: Organization and Management 00 (00): 1–34. doi:10.1080/14479338.2020.1825089.

- Porter, M. E. 2000. “Location, Competition, and Economic Development: Local Clusters in a Global Economy.” Economic Development Quarterly 14 (1): 15–34. doi:10.1177/089124240001400105.

- Pouder, R., and C. H. John St. 1996. “Hot Spots and Blind Spots: Geographical Clusters of Firms and Innovation Source.” The Academy of Management Review 21 (4): 1192–1225. doi:10.2307/259168.

- Resbeut, M., P. Gugler, and D. Charoen. 2019. “Spatial Agglomeration and Specialization in Emerging Markets: Economic Efficiency of Clusters in Thai Industries.” Competitiveness Review 29 (3): 236–252. doi:10.1108/CR-10-2018-0065.

- Richardson, H. W. 1995. “Economies and Diseconomies of Agglomeration.” In Urban Agglomeration and Economic Growth, edited by H. Giersch, 123–155. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-79397-4_6.

- Rigby, D. L., and W. M. Brown. 2015. “Who Benefits from Agglomeration?” Regional Studies 49 (1): 28–43. doi:10.1080/00343404.2012.753141.

- Ritala, P., H. Olander, S. Michailova, and K. Husted. 2015. “Knowledge Sharing, Knowledge Leaking and Relative Innovation Performance: An Empirical Study.” Technovation 35: 22–31. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2014.07.011.

- Ritter-Hayashi, D., P. A. M. Vermeulen, and J. Knoben. 2019. “Is This a Man’s World? The Effect of Gender Diversity and Gender Equality on Firm Innovativeness.” PLoS ONE 14 (9): 1–19. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0222443.

- Rogers, E. M. 1995. Diffusion of Innovations. 4th ed. New York: The Free Press.

- Rotemberg, J. J., and G. Saloner. 2000. “Competition and Human Capital Accumulation: A Theory of Interregional Specialization and Trade.” Regional Science and Urban Economics 30 (4): 373–404. doi:10.1016/S0166-0462(99)00044-7.

- Rulke, D. L., S. Zaheer, and M. H. Anderson. 2000. “Sources of Managers’ Knowledge of Organizational Capabilities.” Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 82 (1): 134–149. doi:10.1006/obhd.2000.2892.

- Rutten, R. 2014. “Learning in Socio-Spatial Context: An Individual Perspective.” Prometheus 32 (1): 67–74. doi:10.1080/08109028.2014.945291.

- Samaniego, R. M. 2013. “Knowledge Spillovers and Intellectual Property Rights.” International Journal of Industrial Organization 31 (1): 50–63. doi:10.1016/j.ijindorg.2012.11.001.

- Shefer, D., and A. Frenkel. 2005. “R&D, Firm Size and Innovation: An Empirical Analysis.” Technovation 25 (1): 25–32. doi:10.1016/S0166-4972(03)00152-4.

- Speldekamp, D., J. Knoben, and A. Saka-Helmhout. 2020. “Clusters and Firm-Level Innovation: A Configurational Analysis of Agglomeration, Network and Institutional Advantages in European Aerospace.” Research Policy 49 (3): 103921. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2020.103921.

- Stam, E. 2007. “Why Butterflies Don‘t Leave: Locational Behavior of Entrepreneurial Firms.” Economic Geography 83 (1): 27–50. doi:10.1111/j.1944-8287.2007.tb00332.x.

- Stern, S., and M. E. Porter. 2001. “Innovation: Location Matters.” MIT Sloan Management Review 42 (4): 28–36.

- Thompson, V. A. 1965. “Bureaucracy and Innovation.” Administrative Science Quarterly 10 (1): 1–20. doi:10.2307/2391646.

- Van Der Panne, G. 2004. “Agglomeration Externalities: Marshall versus Jacobs.” Journal of Evolutionary Economics 14 (5): 593–604. doi:10.1007/s00191-004-0232-x.

- Van Uden, A., J. Knoben, and P. A. M. Vermeulen. 2017. “Human Capital and Innovation in Sub-Saharan Countries: A Firm-Level Study.” Innovation 19 (2): 103–124. doi:10.1080/14479338.2016.1237303.

- Van Uden, A., P. A. M. Vermeulen, and J. Knoben. 2019. “Paralyzed by the Dashboard Light: Environmental Characteristics and Firm’s Scanning Capabilities in East Africa.” Strategic Organization 17 (2): 241–265. doi:10.1177/1476127018755320.

- Vaona, A., and M. Pianta. 2008. “Firm Size and Innovation in European Manufacturing.” Small Business Economics 30 (3): 283–299. doi:10.1007/s11187-006-9043-9.

- Visser, E. J., and O. Atzema. 2008. “With or Without Clusters: Facilitating Innovation Through a Differentiated and Combined Network Approach.” European Planning Studies 16 (9): 1169–1188. doi:10.1080/09654310802401573.

- Wang, Y., L. Ning, J. Li, and M. Prevezer. 2016. “Foreign Direct Investment Spillovers and the Geography of Innovation in Chinese Regions: The Role of Regional Industrial Specialization and Diversity.” Regional Studies 50 (5): 805–822. doi:10.1080/00343404.2014.933800.

- Webb, J. W., G. D. Bruton, L. Tihanyi, and R. D. Ireland. 2013. “Research on Entrepreneurship in the Informal Economy: Framing a Research Agenda.” Journal of Business Venturing 28 (5): 598–614. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2012.05.003.

- Wixe, S. 2015. “The Impact of Spatial Externalities: Skills, Education and Plant Productivity.” Regional Studies 49 (12): 2053–2069. doi:10.1080/00343404.2014.891729.

- World Bank. 2020. “Survey Methodology.” https://www.enterprisesurveys.org/en/methodology.

- Zhang, C. 2017. “Top Manager Characteristics, Agglomeration Economies and Firm Performance.” Small Business Economics 48 (3): 543–558. doi:10.1007/s11187-016-9805-y.