?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Financial, knowledge and market obstacles can restrict firm-level research and innovation (R&I). Public financial support for R&I can clearly help firms that face financial obstacles to invest in R&I. Building on the literature concerning the learning effects of public financial support for R&I, and using a novel combination of administrative and innovation-survey data, we demonstrate for the first time, that such public financial support also results in more R&I in firms that face knowledge and market obstacles. Despite this, however, public financial support for R&I does not reduce the importance that firms attach to their financial and knowledge obstacles. Moreover, it increases the importance that firms attach to their market obstacles. This suggests that while effective at helping firms to increase their R&I activities, addressing firms’ financial and non-financial obstacles may require additional policy interventions, alongside public financial support for R&I. Our study offers novel insights for theory and policy.

1. Introduction

Firms typically face financial and non-financial obstacles which can hinder their research and innovation (R&I) activities (Pellegrino and Savona Citation2017; Zahler, Goya, and Caamaño Citation2022). Public financial support for R&I is a key innovation policy intervention to encourage R&I activities in firms that face financial obstacles associated with limited internal funding, and/or limited access to finance for R&I (Busom, Corchuelo, and Martinez-Ros Citation2014; Chiappini et al. Citation2022). However, firms can also face non-financial obstacles related to a lack of knowledge and resources, and/or a lack of demand for innovation (D’Este, Rentocchini, and Vega-Jurado Citation2014; Stucki Citation2019). While important for firms’ R&I activities, our understanding of how to help firms with such non-financial obstacles remains limited (de Faria, Noseleit, and Los Citation2020; Moraes Silva, Lucas, and Vonortas Citation2020; Pellegrino and Savona Citation2017; Stucki Citation2019). A key reason for this is that, as Szambelan et al. (Citation2020, 425) highlight, ‘while the types of innovation barrier[s] have already been identified, we know relatively little about how firms can overcome these barriers’. Pellegrino and Savona (Citation2017) and Stucki (Citation2019) also note that numerous studies continue to focus on financial obstacles. Therefore, ‘it is more important for policy to extend analysis to non-financial obstacles’ (Pellegrino and Savona Citation2017, 511). Addressing this imbalance is crucial for driving more R&I in firms (Arza and López Citation2021; Moraes Silva, Lucas, and Vonortas Citation2020; Zahler, Goya, and Caamaño Citation2022).

In this paper, we investigate whether public financial support for R&I can help firms to address their financial and non-financial obstacles to R&I. We achieve this by focusing on two key inter-related issues: (1) The extent to which public financial support for R&I enables firms that face financial and non-financial obstacles to engage more in R&I activities; and, (2) Whether public financial support for R&I reduces the importance that firms attach to such obstacles. As several studies demonstrate, public financial support for R&I can lead to firms intensifying their internal and external knowledge search activities, and result in superior innovation performance (Clarysse, Wright, and Mustar Citation2009; Lee Citation2011, Afcha and Lucena Citation2022). This, in turn, can help firms to address non-financial obstacles associated with a lack of knowledge resources (Antonioli, Marzucchi, and Savona Citation2017; Arza and López Citation2021; D’Este, Rentocchini, and Vega-Jurado Citation2014; Moraes Silva, Lucas, and Vonortas Citation2020; Stucki Citation2019). By improving their innovative performance, firms can also potentially address market obstacles related to competition or consumer responses (Szambelan, Jiang, and Mauer Citation2020; Zahler, Goya, and Caamaño Citation2022). However, to the best of our knowledge, ours is the first paper to specifically investigate the extent to which public financial support for R&I impacts firms’ financial and non-financial obstacles to R&I.Footnote1 We do this by addressing the following research questions: Does public financial support for R&I enable firms facing financial, knowledge, and market obstacles to engage more in R&I? Does public financial support for R&I reduce the importance that firms attach to such obstacles?

Our paper makes three novel contributions which intersect the literature regarding the firm-level impacts of public financial support for R&I, and the literature on firms’ obstacles to R&I. Our first contribution is to empirically analyse whether public financial support for R&I enables firms that face financial and non-financial obstacles, to engage more in R&I activities. Previous studies in this vein posit that encouraging R&I in firms facing non-financial obstacles requires ‘selective, deliberate and systematic intervention to address systemic failure’ (Antonioli, Marzucchi, and Savona Citation2017, 861). Policy recommendations arising from earlier studies, therefore, focus primarily on improving the system in which firms operate, by: (1) Enhancing the quality of human capital available to firms (D’Este, Rentocchini, and Vega-Jurado Citation2014; Pellegrino Citation2018); and, (2) Encouraging collaboration between firms and universities and research centres (Antonioli, Marzucchi, and Savona Citation2017; Mulligan et al. Citation2022). As Szambelan et al. (Citation2020) and Moraes Silva et al. (Citation2020) note, however, a sole focus on improving the systems in which firms operate is insufficient. In their view, helping firms that face such non-financial obstacles requires targeted interventions which enable firms to develop knowledge and demand for R&I. Our study advances the understanding of whether public financial support for R&I can act as a key policy intervention to achieve these goals (Afcha and Lucena Citation2022; Lee Citation2011). Our focus is also potentially very insightful for policymakers, who may usefully consider using public financial support for R&I to simultaneously boost R&D investments, while also stimulating knowledge and market capabilities in firms.

Our second contribution is to investigate if public financial support for R&I reduces the importance that firms attach to the financial and non-financial obstacles influencing their R&I decisions. As noted above, public financial support for R&I can enable firms to build capacity and resources, which can help firms to address their financial and non-financial obstacles. However, previous studies demonstrate that public financial support for R&I can increase the likelihood of firms experiencing financial and non-financial obstacles, which can deter future R&I activities (D’Este, Rentocchini, and Vega-Jurado Citation2014; Pellegrino Citation2018; Silva and Carreira Citation2012). According to D’Este et al. (Citation2014) and Pellegrino (Citation2018), this relates to firms being more likely to face obstacles as they intensify their innovative efforts. We shed new light on this issue, by focusing on how public financial support for R&I impacts the importance that firms attach to their financial and non-financial obstacles. This is important for theory and for policy, given that we provide novel insights regarding whether public financial support for R&I can reduce the importance that financial and non-financial obstacles have on firms’ R&I decisions.

Finally, our third contribution is that we distinguish between three key public financial instruments for supporting firm-level R&I. These are: (1) R&D grants; (2) R&D tax credits; and, (3) Funding for academic-industry collaborations. Our focus on these three types of public financial support instruments is vital. While these public financial support instruments to support firm-level R&I share similar goals, their delivery mechanisms are substantially different (Garcia-Quevedo, Martinez-Ros, and Tchorzewska Citation2022; Lenihan et al. Citation2024). This, in turn, can determine the extent to which firms seek to obtain such public financial support instruments (Busom, Corchuelo, and Martinez-Ros Citation2014; Huergo and Moreno Citation2017; Vanino, Roper, and Becker Citation2019). Moreover, it can affect the types of R&I activities that firms perform when they obtain different types of public financial support instruments (Jugend et al. Citation2020; Lee Citation2011; Lenihan et al. Citation2023).Footnote2 The insights emanating from this analysis are potentially very informative for policymakers, regarding the specific public financial support instruments to encourage firm-level R&I that are most effective for addressing firms’ financial and non-financial obstacles to R&I.

Our analysis uses questions regarding obstacles to R&I from the Innovation in Irish Enterprises Survey (IIE, formerly known as the Community Innovation Survey [CIS]).Footnote3 We specifically focus on the 2010 and 2016 IIE survey waves, that include questions on obstacles to R&I. We merge this survey data with administrative data on public financial support for R&I available to firms in Ireland, covering the intervening period from 2011 to 2015. Our data capture the full spectrum of public financial support for R&I from Ireland’s three main funding agencies (Enterprise Ireland, IDA Ireland, and Science Foundation Ireland). The data also capture R&D tax credits, from the Irish Revenue Commissioners. Our sample comprises 1,296 firms, including a total of 223 firms that received public financial support for R&I in the period from 2011 to 2015. Of these, 186 firms encountered obstacles affecting their R&I activities in 2010. For the analysis, we employ a propensity score matching methodology which considers issues of endogeneity affecting the probability of obtaining public financial support for R&I, and the probability of firms facing financial and non-financial obstacles to R&I.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 reviews the relevant literature and formulates the hypotheses. Section 3 describes the data and the empirical approach. Section 4 presents the empirical findings. Section 5 discusses the findings in the context of the literature and concludes with implications for R&D and innovation policy interventions.

2. Conceptual framework and hypotheses

Our paper investigates whether public financial support for research and innovation (R&I) enables firms to address their financial and non-financial obstacles to R&I. We achieve this by considering two critical issues: (1) Whether public financial support for R&I enables firms that face financial and non-financial obstacles to engage more in R&I activities; and, (2) If public financial support for R&I reduces the importance that firms attach to such obstacles. Financial obstacles relate to firms having low levels of internal financial resources, the high cost of R&I activities, and firms having limited access to external finance (Hall et al. Citation2016; Savignac Citation2008). The most critical non-financial obstacles pertain to knowledge and market dynamics (Arza and López Citation2021; D’Este et al. Citation2012; Galia and Legros Citation2004; Mohnen et al. Citation2008; Pellegrino Citation2018; Zahler, Goya, and Caamaño Citation2022).Footnote4 Knowledge obstacles relate to firms having low and/or inadequate levels of human capital resources (D’Este, Rentocchini, and Vega-Jurado Citation2014), limited access to information on technologies and markets (Pellegrino Citation2018), and facing difficulties in finding partners for R&I (Antonioli, Marzucchi, and Savona Citation2017). Market obstacles primarily relate to uncertain demand for innovation (Zahler, Goya, and Caamaño Citation2022).

Most of the evidence regarding the impact of firms’ obstacles to R&I pertains to financial obstacles (see, for example, amongst many others, Hall et al. Citation2016; Lahr and Mina Citation2021; Montresor and Vezzani Citation2016; Perez-Alaniz et al. Citation2023; Savignac Citation2008; Silva and Carreira Citation2012). Only a small number of studies consider non-financial obstacles, but the literature on this topic is growing in significance (see Antonioli, Marzucchi, and Savona Citation2017; Arza and López Citation2021; Pellegrino Citation2018; Pellegrino and Savona Citation2017; Szambelan, Jiang, and Mauer Citation2020; Zahler, Goya, and Caamaño Citation2022). The available evidence suggests that both financial and non-financial obstacles reduce firms’ likelihood of engaging in R&I activities, and increase their likelihood to delay and/or discontinue existing R&I (Arza and López Citation2021; Blanchard et al. Citation2013; Galia and Legros Citation2004; Radicic Citation2021; Zahler, Goya, and Caamaño Citation2022).

Public financial support for R&I focuses on addressing market and systemic failures, such as asymmetric information and disincentives, that hinder firms’ abilities to finance and benefit from R&I activities (Haapanen, Lenihan, and Mariani Citation2014). Academics and policymakers also increasingly recognise that, by encouraging firm-level R&I, public financial support for R&I can also result in organisational learning effects in firms (Afcha and Lucena Citation2022, Chapman and Hewitt-Dundas Citation2018, Clarysse, Wright, and Mustar Citation2009; Wanzenböck, Scherngell, and Fischer Citation2013). Therefore, firms facing knowledge and market obstacles may seek such public financial support to engage in R&I activities, in view of developing additional R&I and market knowledge. This, in turn, can affect the importance that firms attach to their obstacles. To the best of our knowledge, however, ours is the first paper to specifically analyse whether this is indeed the case. This section identifies some critical mechanisms through which public financial support for R&I can affect firms’ financial and non-financial obstacles. This is followed by the formulation of the hypotheses driving the empirical analyses. Finally, we discuss potential differences in the expected effects of different types of public financial support instruments to support firm-level R&I, on firms’ obstacles to R&I.

2.1. Public financial support and the R&I activities of firms facing financial and non-financial obstacles

Public financial support for R&I is a key policy instrument used by policymakers in many countries to help firms facing financial obstacles to invest in R&I. This can take place through three main mechanisms. The first mechanism is by providing firms with liquidity for R&I (Becker Citation2015). The second mechanism is by alleviating information asymmetries in capital markets hindering firms’ abilities to access external finance for R&I (Hall et al. Citation2016). Information asymmetries occur when firms do not disclose information on innovative projects (to protect proprietary knowledge), and lenders, therefore, cannot assess the viability and value of these projects (Akerlof Citation1970; Carboni Citation2017; Mina et al. Citation2021). As a result, lenders may refrain from lending for R&I activities and/or require higher risk premiums (Hall et al. Citation2016). Public financial support for R&I can signal promising R&I projects, and reduce information asymmetries (Feldman and Kelley Citation2006; Kleer Citation2010). This can improve firms’ access to external finance for R&I projects (Carboni Citation2017; Hottenrott, Lins, and Lutz Citation2018). The third mechanism consists of firms using some liquidity from public financial support for R&I to acquire physical capital, which can serve as collateral when seeking external finance (Colombo, Croce, and Guerini Citation2013).

A key novelty of this paper, is that we focus on whether public financial support for R&I can also enable firms that face non-financial obstacles (related to knowledge and market dynamics) to engage more in R&I. This is important because knowledge obstacles relate to firm-level knowledge and capabilities which, as Dosi et al. (Citation2021) note, are the result of firms’ routines, are slowly accumulated, and exhibit a high degree of persistence in terms of their strengths and weaknesses. Importantly, firms develop knowledge by increasing their internal and external knowledge sourcing activities (Roper, Du, and Love Citation2008; Uhlaner et al. Citation2013). As noted by Moraes Silva et al. (Citation2020), in turn, market obstacles arise from conditions that are external to firms (i.e. the market). However, as demonstrated by Szambelan et al. (Citation2020) and Zahler et al. (Citation2022), R&I can enable firms to develop capabilities and resources to address such obstacles, especially if firms engage in developing innovations with high levels of novelty. Public financial support for R&I can thus encourage firms facing knowledge and market obstacles to engage in R&I, as a means to build R&I capabilities and resources. This can take place via at least two key inter-related mechanisms, as detailed in the discussion that follows.

The first mechanism comprises firms using public financial support for R&I to accelerate organisation learning, by increasing their internal and external knowledge search activities (Clarysse, Wright, and Mustar Citation2009). As noted above, public financial support for R&I can enable firms to increase their internal R&I expenditure. In turn, firms may engage in generating new knowledge, and in identifying novel combinations of new and old knowledge for innovation (Kim Citation1998; Radas et al. Citation2015). As a result, public financial support for R&I can encourage learning-by-doing (Levinthal and March Citation1993; Teece Citation2007), and increase firm-level absorptive capacity (Cohen and Levinthal Citation1990).Footnote5 Such learning effects can be especially large if firms use public financial support for R&I to increase the breadth of their R&I activities, as this can unravel complementarities and learning effects across firms’ R&I portfolios (Leiponen Citation2012; Klingebiel and Rammer Citation2014). Moreover, public financial support for R&I can prompt firms to engage with external sources of knowledge, by encouraging firms to carry out collaborative R&I, and/or increasing the breadth of collaborators with which firms engage (Hottenrott and Lopes-Bento Citation2014; Okamuro and Nishimura Citation2015; Kim et al. Citation2021). This can accelerate inter-organisational learning, which results from spillovers that arise when collaborating with external partners (Clarysse, Wright, and Mustar Citation2009). Engaging in new collaborative R&I efforts can also compensate for firms’ lack of internal knowledge resources (Antonioli, Marzucchi, and Savona Citation2017; de Faria, Noseleit, and Los Citation2020; Moraes Silva, Lucas, and Vonortas Citation2020). Based on this, therefore, firms that face knowledge obstacles may use public financial support for R&I as a key mechanism to build capacity and resources for R&I.

The second mechanism arises where firms that face market obstacles use public financial support for R&I as a means to produce more novel forms of innovation, to enter new markets, and generate new demand. Public financial support for R&I lowers the risk-reward ratio of R&I activities, and can increase firms’ tolerance for riskier innovative projects (Becker Citation2015). Therefore, public financial support for R&I can encourage firms to engage in riskier R&I activities, and to innovate outside of their existing knowledge base (Beck, Lopes-Bento, and Schenker-Wicki Citation2016; Chiappini et al. Citation2022; Perez-Alaniz et al. Citation2024). Because of this, firms can engage in projects previously deemed ‘too expensive’ and/or ‘too risky’ (Colombo, Croce, and Guerini Citation2013; Takalo, Tanayama, and Toivanen Citation2012). Consequently, firms can enhance their ability to develop more novel types of innovative processes, products, and services, target new markets, and/or generate new demand (Lee Citation2011; Leten, Kelchtermans, and Belderbos Citation2022). This is because novel forms of innovation, such as products and services that are new to the market (i.e. radical innovations), have the potential to disrupt existing markets and shape new ones (Grashof and Kopka Citation2022; Yang, Chou, and Chiu Citation2014). Therefore, firms that face market obstacles may seek public financial support for R&I to innovate more, and produce more novel types of innovations.

It is important to note that the above mechanisms are likely to be highly inter-dependent. For example, improvement in firms’ abilities to generate knowledge can translate into firms generating additional sales from innovation (Hewitt-Dundas, Gkypali, and Roper Citation2019). This, in turn, can result in firms having higher levels of internal financial resources for R&I (Perez-Alaniz et al. Citation2023). In addition, as several studies note, firms that have high levels of specialised knowledge for R&I can circumvent financial obstacles, by using existing resources in new ways (Baker and Nelson Citation2005; D’Este, Rentocchini, and Vega-Jurado Citation2014; Hoegl, Gibbert, and Mazursky Citation2008). In this context, public financial support for R&I can not only enable firms to invest more in R&I, but also help firms facing non-financial obstacles to engage more in R&I activities. Based on this, our first hypothesis is as follows:

H1:

Public financial support for R&I enables firms that experience financial, knowledge and market obstacles to engage more in R&I.

2.2. Public financial support and the importance that firms attach to their financial and non-financial obstacles

We now focus on how public financial support for R&I affects the importance that firms attach to their financial and non-financial obstacles. This is important because there are two contrasting views in this regard. In line with our discussion in Section 2.1, the first view suggests that public financial support for R&I will reduce the importance that firms attach to their financial and non-financial obstacles. This is because, as discussed earlier, public financial support for R&I can help firms that face financial and non-financial obstacles to engage more in R&I. This, in turn, can enable such firms to develop additional knowledge for R&I, and generate new revenue from innovation. As a result, firms become more able to cope with the obstacles that they face. As Amore (Citation2015) shows, for example, firms that can address financial obstacles and innovate during a recession, can build on such past experiences when facing financial difficulties during new recessions. Firms that face new knowledge obstacles may also ‘share the pain’, by engaging in collaborations with other firms and/or universities (Antonioli, Marzucchi, and Savona Citation2017, 343). Finally, firms that increase their market share through innovation, as a result of public financial support for R&I, will be more likely to regard innovation as a key avenue to overcome market obstacles (Szambelan, Jiang, and Mauer Citation2020; Zahler, Goya, and Caamaño Citation2022). Based on this, public financial support for R&I can potentially reduce the importance that firms attach to their financial, knowledge and market obstacles. Therefore, our next hypothesis is as follows:

H2a:

Public financial support for R&I reduces the importance that firms attach to their financial, knowledge and market obstacles.

In contrast to the above, the second view relates to previous studies on this topic highlighting that, as firms become more innovative, they are typically more likely to face financial and non-financial obstacles (D’Este et al. Citation2012; Hottenrott and Peters Citation2012, Coad et al. Citation2016; Zahler, Goya, and Caamaño Citation2022). Such firms are also more likely to report financial and non-financial obstacles as highly important factors for their R&I activities (D’Este et al. Citation2012; Galia and Legros Citation2004; Pellegrino Citation2018). Moreover, and importantly, firms’ financial and non-financial obstacles can persist over time, even if firms improve their levels of resources and capabilities for R&I. D’Este et al. (Citation2014), for example, show that firms in Spain continue to attach high levels of importance to their knowledge obstacles, despite improving their human capital resources (as measured by the proportion of employees with a third level education). Hewitt-Dundas (Citation2006) reports similar findings, in the context of manufacturing plants in Ireland. More specifically, the study reports that firms continue to attach a high level of importance to their financial and non-financial obstacles, despite showing clear evidence of ‘capability building’, in the sense of increasing their R&D expenditure, and their innovation outputs. Based on this, public financial support for R&I may not reduce the importance that firms attach to their obstacles. In fact, by enabling firms to engage more in R&I, public financial support for R&I may even result in firms increasing the importance that they attach to their financial and non-financial obstacles. Therefore, our hypothesis is as follows:

H2b:

Public financial support increases the importance that firms attach to their financial, knowledge and market obstacles.

2.3. The impact of different types of public financial support instruments on firms’ financial and non-financial obstacles

Sections 2.1 and 2.2 conceptualise public financial support for R&I as one overarching policy instrument. In reality, there are three main types of financial instruments to support firm-level R&I, as observed in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and European Union (EU) countries (Busom, Corchuelo, and Martinez-Ros Citation2014; Lenihan, Mulligan, and O’Driscoll Citation2020; Vanino, Roper, and Becker Citation2019). These are: (1) R&D grants; (2) R&D tax credits; and (3) Funding for academic-industry collaborations.

R&D tax credits focus on reducing the cost of firms’ R&I activities, as firms can claim a percentage of their eligible R&I expenditure as tax credits (Chang Citation2018; Lenihan et al. Citation2024). Moreover, R&D tax credits are not competitive, meaning that all R&D performing firms can claim them (Lenihan et al. Citation2024). Labeaga et al. (Citation2021) demonstrate that once firms claim R&D tax credits for the first time, they are likely to continue claiming R&D tax credits on a recurring basis. In their view, the predictable nature of R&D tax credits can encourage firms to increase their R&I spending, safe in the knowledge that they will be subsidised. As a result, firms may engage in R&I activities with high levels of sunk costs, such as hiring new talent (Lenihan et al. Citation2023; Petrin and Radicic Citation2023). However, Busom et al. (Citation2014) note that some firms, especially smaller-sized firms, may face difficulties in claiming R&D tax credits due to the application process representing a heavy administrative burden. Furthermore, R&D spending needs to occur before firms can claim R&D tax credits. This means that R&D tax credits can be less attractive for resource constrained firms, and firms that do not carry out R&D on a persistent basis (Busom, Corchuelo, and Martinez-Ros Citation2014; Lenihan et al. Citation2024). Another potential drawback of R&D tax credits is that firms may use this public financial support to carry out routine R&I activities (Labeaga et al. Citation2021; Lenihan et al. Citation2023; Thomson Citation2017). In cases such as this, R&D tax credits may result in limited additional learning and innovative performance effects.

R&D grants and funding for academic-industry collaborations are competitive in nature, and typically focus on specific R&I projects with potentially high rates of socio-economic returns (Lenihan et al. Citation2023; Mulligan et al. Citation2022; Vanino, Roper, and Becker Citation2019). Targeted R&I projects tend to focus on R&I activities that require the generation of new knowledge, and that have the potential to result in innovations with high levels of novelty (Hünermund and Czarnitzki Citation2019; Lenihan et al. Citation2023). Firms may thus prefer R&D grants and funding for academic-industry collaborations to perform core R&D projects which, a priori, can result in high levels of additional learning and market outcomes (Lenihan et al. Citation2023; Vanino, Roper, and Becker Citation2019). As Mina et al. (Citation2021) demonstrate, however, R&D grants tend to be allocated to firms with already high levels of R&I performance (as measured by previous patenting activity). This can reduce the likelihood of R&D grants resulting in learning effects, as recipient firms may be already highly R&I capable (Nilsen, Raknerud, and Iancu Citation2020; Wanzenböck, Scherngell, and Fischer Citation2013). Engaging in collaborations with academics, in turn, may bring about new challenges for firms. This is because academics may have very different expectations, timelines, and desired outputs when compared to firms (Cassiman, Veugelers, and Arts Citation2018, Ryan et al. Citation2018; Hewitt-Dundas, Gkypali, and Roper Citation2019; Lenihan et al. Citation2023). Moreover, knowledge transfer between academics and firms is not seamless; it requires firms to already have high levels of R&I capabilities (Scandura Citation2016).

Considering the above, there are numerous factors influencing the extent to which different types of public financial support instruments to support firm-level R&D can affect firms’ obstacles to R&I. Therefore, it is likely that there is significant heterogeneity in the effectiveness of the various public financial support instruments at helping firms to address their financial and non-financial obstacles to R&I. Our analysis sheds light on this issue, by analysing the relative impact of each of these three individual types of public financial instruments to support firm-level R&I. This is in terms of helping firms facing financial and non-financial obstacles to engage more in R&I activities, and the importance that firms attach to such obstacles.

3. Data and empirical approach

In this paper, we investigate whether public financial support for Research and Innovation (R&I) enables firms facing financial and non-financial obstacles to engage more in R&I activities. Moreover, we investigate if public financial support for R&I reduces the importance that firms attach to these obstacles. Our analysis uses information on firms’ obstacles to R&I included in the 2010 and 2016 waves of the Innovation in Irish Enterprises survey (IIE, formerly known as Community Innovation Survey [CIS]). Appendix A shows the framing of the questions relevant to our study in each IIE survey wave considered. The IIE is a biennial survey with information on firms’ internal characteristics, their research and innovation activities, and their obstacles to R&I. The IIE dataset includes information on firms with at least 10 employees (i.e. it does not include micro-firms).Footnote6 We specifically focus on the 2010 and 2016 IIE survey waves, that include questions on obstacles to R&I.

Our analysis requires observing firms’ R&I activities before, during and after the receipt of public financial support for R&I. This is to control for: (1) Potential bias arising from firm-level heterogeneity affecting firms’ likelihood of facing obstacles (D’Este et al. Citation2012; Pellegrino Citation2018); and (2) Firms’ likelihood of obtaining public financial support for R&I (Hottenrott and Lopes-Bento Citation2014; Nilsen, Raknerud, and Iancu Citation2020). Therefore, we limit our sample to firms present in both the 2010 and 2016 IIE survey waves. Using a sub-sample of a representative survey, such as the IIE, can induce bias in our analysis. However, as Appendix B demonstrates, our effective sample largely maintains the representativeness of the IIE survey.

We merge the IIE survey data with administrative data containing the full range of public financial support for R&I instruments available to firms in Ireland, during the intervening period between the two IIE survey waves, from 2011 to 2015.Footnote7 This is obtained from Ireland’s three main funding agencies (Enterprise Ireland, IDA Ireland, and Science Foundation Ireland), with the R&D tax credit data coming from the Irish Revenue Commissioners, which oversee all tax-related matters in Ireland. Enterprise Ireland (EI) provides a comprehensive suite of supports for Irish-owned firms from start-up to maturity, with a particular focus on innovation and exporting (Enterprise Ireland Citation2022). The Industrial Development Agency (IDA) Ireland focuses on attracting and supporting investments into Ireland by foreign-owned companies (IDA Ireland Citation2021). We only consider public financial support instruments from EI and IDA Ireland that focus on firm-level R&I. Science Foundation Ireland (SFI) primarily funds scientific research in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs). This is a vital pillar of the innovation policy system in Ireland, as SFI funded institutions can provide cutting edge knowledge to firms through co-funded collaborative research projects (Science Foundation Ireland Citation2022). Our data capture whether firms engaged in these co-funded collaborative research projects. Appendix C lists all public financial support for R&I instruments included in the analysis. Using administrative data is an important advantage of our analysis because it permits a detailed understanding of the public financial for R&I support instruments considered (Hottenrott, Lins, and Lutz Citation2018; Nilsen, Raknerud, and Iancu Citation2020). It enables us to distinguish between: (1) R&D tax credits; (2) R&D grants; and (3) Funding for academic-industry collaborations, as detailed in Section 3.2.

The final dataset comprises two repeated cross-sections from the IIE (2010 and 2016) for 1,296 firms which are present in both surveys. A total of 223 firms claimed/received at least one public financial support for R&I instrument in the period from 2011 to 2015, but only 186 of these firms encountered obstacles to R&I in 2010.Footnote8

3.1. Obstacles to research and innovation

To identify firms that experience financial and non-financial obstacles to R&I, we use information from a module of the IIE survey pertaining to the factors hampering firms’ R&I activities. As Appendix A shows, the IIE 2010 survey includes data on nine obstacles. The 2016 survey includes data on eight obstacles, but only six obstacles matched those included in the 2010 survey. Our analysis focuses on these six obstacles. In both survey waves, firms specify the importance of each of these six obstacles, as follows: 1=high importance; 2=medium importance; 3=low importance; and 4=not important.

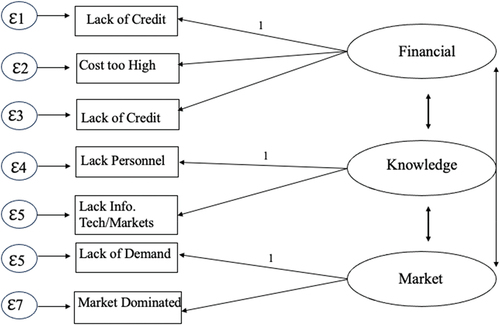

To construct our measures of financial and non-financial obstacles in 2010 (i.e. our initial period), we combine the above six categorical variables into three binary variables, corresponding to three headline obstacles (i.e. financial, knowledge and market), at any level of importance. For example, Financial Obstacle is a headline measure, and takes the value of 1 if a firm experienced a lack of internal finance, a lack of credit, or if it considered the cost of R&I being too high, in the last three years (at any level of importance, such as low, medium, or high). Otherwise, the value is 0. Appendix D explains these variables, with a summary presented in . The headline indicators used here are commonly used measures of firms’ obstacles to R&I, as evidenced by a number of earlier studies (see, for example, D’Este et al. Citation2012, Citation2014; Pellegrino and Savona Citation2017; Zahler, Goya, and Caamaño Citation2022). For robustness and completeness, we follow Galia and Legros (Citation2004) and use a second set of measures of firms’ obstacles to R&I, generated by means of a confirmatory factor analysis. We explain the construction of these variables in Section 4.3.

Table 1. Firms facing obstacles in 2010 (percentage)

3.2. Dependent variables

In our analysis, we focus on whether public financial support for R&I enables firms that experience financial and non-financial obstacles, to engage more in R&I activities (Hypothesis 1). Furthermore, we focus on whether public financial support for R&I reduces the importance that firms attach to such obstacles (Hypothesis 2a and 2b).

To test Hypothesis 1, we consider the extent to which public financial support for R&I results in firms that experience financial obstacles, to increase their R&I investments. We focus on this specific R&I activity because, as Becker (Citation2015) notes, financial obstacles negatively affect firms’ R&I investments. To measure this, we use the natural logarithm of firms’ total investment in R&I (Marino et al. Citation2016). We obtain firms’ total R&I investments from the IIE survey, as the sum of the following R&I investment categories: (1) In-house R&D; (2) External R&D; (3) Acquisition of machinery, equipment, software, and buildings for R&I; (4) Acquisition of knowledge from other enterprises or institutions; and (5) All other innovation activities (including design, marketing, and other relevant activities).

Moreover, we consider the extent to which public financial support for R&I enables firms experiencing knowledge obstacles to: (1) Increase their breadth of collaborators, measured as a count variable ranging from 0 to 4 to account for suppliers, clients, other firms and public knowledge providers (Laursen and Salter Citation2014); and, (2) Enhance their breadth of innovations introduced to the market, as measured by a count variable ranging from 0 to 4, depending on whether firms innovated in processes, products, services and forms of organisation (D’Este et al. Citation2012). We focus on these R&I activities because, as discussed in Section 2.1, these are two key avenues through which firms can increase their knowledge resources. Engaging in additional collaborations can help firms to obtain external knowledge for R&I, and requires firms to develop skills for absorbing such knowledge (Antonioli, Marzucchi, and Savona Citation2017; Hewitt-Dundas, Gkypali, and Roper Citation2019). For Klingebiel and Rammer (Citation2014), increasing the breadth of R&I activities requires firms to learn how to manage multiple R&I projects at the same time, and can result in knowledge complementarities across R&I portfolios (Hullova et al. Citation2019).

Finally, we focus on the extent to which firms that experience knowledge obstacles are able to increase their turnover from innovation. We specifically consider whether such turnover is generated from: (1) New to the firm goods and services; and/or (2) New-to-market goods and services (both measured as the percentage of turnover), individually. We focus on these variables because they are widely used in the literature to analyse whether firms are indeed able to successfully commercialise their innovations (Hewitt-Dundas, Gkypali, and Roper Citation2019). We obtain these variables from two specific questions in the IIE survey, where firms indicate the percentage of turnover that was derived from (1) New to the firm goods and services, and (2) New to the market goods and services. presents the descriptive statistics for our unmatched (i.e. raw) dependent variables between treated and untreated firms, with treated firms being those firms receiving public financial support for R&I from 2011 to 2015. The table shows that firms that received public financial support for R&I during 2011 to 2015 (i.e. treated firms) performed better, on average, across all of the indicators considered, when compared to untreated firms.

Table 2. Dependent variables (step 1).

To test Hypothesis 2a and 2b, we create three variables, measuring the changes in the levels of importance that firms attached to their financial and non-financial obstacles, between 2010 and 2016. As discussed in Section 3.1, firms are required to declare the levels of importance they attach to each of the hampering factors in Appendix A, as follows: 1 = high importance; 2 = medium importance; 3 = low importance; and 4 = not important. Therefore, in a similar way to the headline indicators as discussed in Section 3.1, we combine the hampering factors in Appendix A into three headline indicators (i.e. financial, knowledge and market obstacles). In these cases, however, the headline indicators take the value of 1 if the importance that firms attached to their hampering factors for the financial, knowledge and market categories in 2016 has been reduced by at least one level of importance, when compared to 2010. For example, the variable Firms reducing the importance attached to Financial Obstacles is a headline measure. The variable takes the value of 1 if the level of importance that firms attached to any of the financial hampering factors (i.e. a lack of internal finance, a lack of credit, or the cost of R&I being too high) was lower in 2016. This is in comparison to the level of importance that firms attached to the same hampering factors in 2010 (e.g. from high in 2010 to medium, low, or not important in 2016). This resulted in three variables (i.e. one each for financial, knowledge and market obstacles), as presented in .

Table 3. Dependent variables (step 2).

Using the above variables, Hypothesis 2a is supported if the treatment effects show that these variables are positive and significantly affected by public financial support for R&I. This would suggest that, on average, firms reduced the importance that they attached to their obstacles, following the receipt of public financial support for R&I. This is in comparison to untreated firms that also experienced obstacles in 2010. In contrast to this, we consider negative and significant coefficients to support Hypothesis 2b.

3.3. Public financial support for R&I

Most previous studies concerned with public financial support for R&I in the context of obstacles to R&I mainly focused on financial obstacles using survey data, which do not allow for an analysis of different forms of public financial instruments (Silva and Carreira Citation2012). Our administrative data permit analysing different public financial support instruments for R&I.

Appendix C lists all of the public financial instruments for R&I considered in the analysis, and classifies them as: (1) R&D tax credits; (2) R&D grants; and (3) Funding for academic-industry collaborations (Busom, Corchuelo, and Martinez-Ros Citation2014; Lenihan, Mulligan, and O’Driscoll Citation2020; Zúñiga-Vicente et al. Citation2014). R&D tax credits are available to all firms in Ireland which are liable for corporation tax, and that undertake R&D activities involving systemic, investigative, and experimental research activities in the field of science and technology (Irish Revenue Commissioners Citation2020). R&D grants are allocated directly to firms through a competitive process. Firms are required to demonstrate the importance of the proposed projects, their expected outcomes, and their abilities to complete such projects (Enterprise Ireland Citation2022; IDA Ireland Citation2021). Funding for academic-industry collaborations is also competitive in nature. However, firms do not receive any direct financial incentives. This funding is allocated to academics in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) to engage in co-funded collaborative R&D activities with firms. Therefore, the applications need to be submitted by the HEIs (Enterprise Ireland Citation2022; IDA Ireland Citation2021; Science Foundation Ireland Citation2022).Footnote9

In our analysis, we combine the instruments in Appendix C into four binary variables. Public Financial Support for R&I is our main variable of interest. This variable is equal to 1 if firms received any of the financial instruments for R&I featured in Appendix C, from 2011 to 2015; otherwise, the value is 0. The remaining three variables follow the same methodology for each type of instrument. summarises these variables.

Table 4. Public financial support instruments for R&I used in the analysis (Step 3).

3.4. Empirical approach

We structure our analysis in three steps. In the first step, we analyse whether public financial support for R&I enables firms that face financial and non-financial obstacles to engage more in R&I (i.e. Hypothesis 1). In line with studies focussed on the additionality of public financial support for R&I, we control for selection bias in the use of public financial support for R&I by employing a propensity score matching (PSM) methodology (Czarnitzki and Lopes-Bento Citation2013; Vanino, Roper, and Becker Citation2019). The PSM approach relies on the conditional independence assumption (CIA), where treatment and outcome are assumed to be statistically independent for firms with the same set of observable characteristics (Rubin Citation1977). Assuming that the matching is performed correctly, the average treatment effect of public financial support for R&I on firms’ R&I activities can be obtained as follows:

In EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) , aTT denotes the average treatment effect of public financial support for R&I i (i=Public Financial Support for R&I, which pertains to any type of public financial support for R&I instrument) on several outcome variables (j), which are the five variables in . YTi|S = 1 is the outcome variable j for firms that received public financial support for R&I i, which is observable. YTi|S = 0 is the outcome variable j for the counterfactual scenario if treated firms had not received such public financial support for R&I (S = 0). YTij|S = 0 needs to be estimated, and consists of firms that did not receive public financial support for R&I, but that are statistically similar across observable characteristics to those firms receiving such public financial support before treatment took place (Czarnitzki and Lopes-Bento Citation2013; Radas et al. Citation2015). Following Czarnitzki and Lopes-Bento (Citation2013), Radas et al. (Citation2015) and Vanino et al. (Citation2019), we perform the PSM routine for EquationEquation (1)

(1)

(1) by estimating firms’ propensity to receive public financial support for R&I conditionally upon a set of exogenous variables (X), before the treatment takes place (i.e. in 2010). The predicted probabilities are compiled into a single index (i.e. the propensity score), and firms are matched according to this index. describes the observable variables used in the matching process, with presenting the associated summary statistics. As explained below in more detail, the variables for NACE Rev 2 categories and for firms’ sizes are not included as matching variables in . This is because these variables are used in the matching process by multiplying the propensity score by the categorical variables Size (Small = 1, Medium = 2, and Large = 3) and NACE Rev. 2 classifications. This is similar to the process described as ‘Exact Matching’ by Vanino et al. (Citation2019).

Table 5. Variables used in the matching process.

Table 6. Summary statistics of variables used in the matching process.

As shows (in Panel A), a set of binary variables measure whether: (1) Firms are Irish owned (Doran and Ryan Citation2014); (2) Firms are part of an enterprise group (Jissink , Schweitzer and Rohrbeck Citation2019); and, (3) Firms are exporters (Love and Roper Citation2015). We also control for firms’ age, where age is measured by the difference between 2010 and firms’ registration years. In addition, we control for firms’ innovative efforts and outcomes in 2010, with: (1) A binary variable measuring whether firms introduced radical innovations in 2010; (2) A continuous variable measuring the logarithm of firms’ total investments in R&I in 2010; (3) A count variable ranging from 0 to 4, measuring the breadth of innovation partners in 2010 (i.e. clients, customers, other firms, and public knowledge providers); (4) Firms’ percentage of turnover from innovation in 2010; and, (5) A count variable measuring firms’ breadth of innovation activities ranging from 0 to 4 (i.e. process, product, service, and organisational innovation). Matching according to firms’ R&I efforts before the treatment takes place is important, as such efforts can influence firms’ likelihood to obtain public financial support (Busom, Corchuelo, and Martinez-Ros Citation2014; Mina et al. Citation2021). Also, as noted in Section 2.2, firms’ R&I efforts can influence their likelihood to face financial and non-financial obstacles.

Finally, we use three dummy variables to measure whether firms encountered financial, knowledge and/or market obstacles in 2010 (as described in Section 3.1). Given that firms typically face more than one obstacle, the inclusion of these three variables permits matching firms that experienced the same combination of obstacles in 2010.

It is important to outline that, in performing our analysis, we focus on each of the three obstacles individually. This is because our focus is on understanding whether firms that experience a given obstacle and receive public financial support for R&I, engage in specific R&I activities associated with that obstacle. For example, when focusing on financial obstacles, we specifically focus on firms that experience these obstacles, regardless of whether they also experience other obstacles (e.g. when considering financial obstacles, the binary variable measuring financial obstacles needs to have the value of 1). Our analysis thus focuses on the extent to which these firms are able to increase their R&I investments, following the receipt of public financial support for R&I. The same applies for firms experiencing knowledge and market obstacles, in which cases, we focus on the specific variables associated with each of these obstacles, as presented in . This approach enables us to compare treated firms that face a given obstacle, with a control group of firms that also experience the same specific obstacle. As the only difference between these two groups of firms is whether they receive public financial support for R&I, we can attribute the changes in their R&I activities to the support. Therefore, our analysis requires repeating the matching process three times. As described in Section 3.2, for these three obstacles, a total of five outcomes variables are investigated (see ). This requires the estimation of EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) a total of five times.

Following Hottenrott and Lopes-Bento (Citation2014), in each of the above cases, we use a nearest neighbour approach, matching treated firms with up to three comparator firms. In doing so, we use the recommended caliper of 0.2 points of the standard deviation of the propensity score (Austin Citation2011). Furthermore, as noted above, we only allow matches between: (1) Firms of the same size, as measured by the categorical variables denoting 1=small, 2=medium and 3= large-sized firms, according to their number of employees; and, (2) Firms within the same sector, using one-digit NACE Rev. 2 classifications (Vanino, Roper, and Becker Citation2019). To achieve this, we multiply the propensity scores by the categorical variables Size (i.e. Small = 1, Medium = 2, and Large = 3) and NACE Rev. 2 classifications. In this way, we ensure that the propensity scores for each of the size-sector combinations are sufficiently different from each other, to the extent that different firms in different size-sector categories cannot be matched (i.e. Exact Matching).Footnote10 Standard tests in Panel A of confirm that no significant differences exist between the treatment and control groups across all variables used (for the specific case of financial obstacles).Footnote11

Table 7. Balance check stage 1 and 2 (financial obstacles).

The second step of our analysis focuses on whether public financial support for R&I reduces/increases the importance that firms attach to the obstacles they face (i.e. Hypotheses 2a and 2b). Here, we follow a similar approach as above. However, in addition to controlling for selection bias in the allocation of public financial support, we consider issues of reverse causality (i.e. endogeneity) between firms’ R&I efforts and their obstacles (Savignac Citation2008). This is carried out as follows:

EquationEquation (2)(2)

(2) is similar to EquationEquation (1)

(1)

(1) , but now j corresponds to the variables capturing the changes in the importance that firms attach to their obstacles (j= Financial, Knowledge and Market obstacles). Moreover, the equation includes an additional matching restriction (denoted as P) to account for firms’ R&I efforts and outcomes in 2016 (i.e. the outcome period). Panel B of explains these variables, with a summary of these variables presented in Panel B of . We include: (1) The natural logarithm of firms’ total R&I investments in 2016; (2) Firms’ percentage of turnover from innovation in 2016; and, (3) Whether firms introduced radical innovations in 2016. The matching routine is performed in the same way as described above. Also, similarly to our first step, we repeat the matching routine three times, once each for financial, knowledge, and market obstacles. In this case, we only have three outcome variables. Therefore, we estimate EquationEquation (2)

(2)

(2) a total of three times. Panel B of shows the standard tests performed, which ensure comparability between the treated and (constructed) control group (for the specific case of financial obstacles).

Previous studies control for potential reverse causality between firms’ R&I efforts and their obstacles by: (1) Jointly modelling firms’ R&I efforts, and their likelihood to face obstacles (Blanchard et al. Citation2013; Mohnen et al. Citation2008); or, (2) Focussing their analysis on firms which intended to innovate (Pellegrino Citation2018; Pellegrino and Savona Citation2017; Zahler, Goya, and Caamaño Citation2022). Our approach extends such studies, by not only controlling for firms’ decisions to innovate, but also controlling for their innovative performance before, during and after the period of intervention. We achieve this by constructing a counterfactual of firms that: (1) Are statistically similar across the observable characteristics in 2010; (2) Experienced the same set of financial, knowledge and market obstacles in 2010; (3) Engaged in R&I similarly to treated firms both in 2010 and 2016; and, (4) Only differ in the treatment variable (i.e. S = 1 and S = 0). As a result, our approach represents a more detailed way of dealing with potential unobserved heterogeneities driving firms’ obstacles to R&I.

Finally, the third step of our analysis focuses on identifying potential differences in the results obtained from estimating EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) and EquationEquation (2)

(2)

(2) , when considering different types of public financial support for R&I instruments. To operationalise this, we first obtain the probabilities of firms receiving each of the three types of public financial support instruments to support firm-level R&I considered (i.e. R&D tax credits, R&D grants, and Funding for academic-industry collaborations), individually. We then use the propensity scores obtained from these estimations, and perform the matching routine for each of the above types of instruments. Here, we have three obstacles and three public financial support for R&I instruments. Therefore, we repeat the matching routine nine times. Finally, we estimate EquationEquation (1)

(1)

(1) 15 times (i.e. five outcome variables for three public financial support for R&I instruments), and EquationEquation (2)

(2)

(2) nine times (i.e. three outcome variables for three public financial support for R&I instruments).

4. Empirical results

We now proceed to present our main results, which are presented as average treatment effects on the treated firms.

4.1. The impact of public financial support on the R&I activities of firms facing obstacles

We begin by presenting the results obtained by using the aggregated measure of public financial support for Research and Innovation (R&I). In terms of financial obstacles, Panel A of indicates that public financial support for R&I helped firms facing such obstacles to invest more in R&I. The average treatment effect captured by the variable Ln Total R&D Investments shows that public financial support for R&I enabled firms that faced financial obstacles to invest, on average, circa 15.4 percent more in R&I (p < 0.05). This is relative to untreated firms that also faced financial obstacles.Footnote12 This finding is in line with previous studies that focused on public financial support for R&I, as a means to enabling firms to address their financial obstacles to R&I (Carboni Citation2017; Colombo, Croce, and Guerini Citation2013).

Table 8. Impact of public financial support for R&I on the R&I activities of firms facing obstacles.

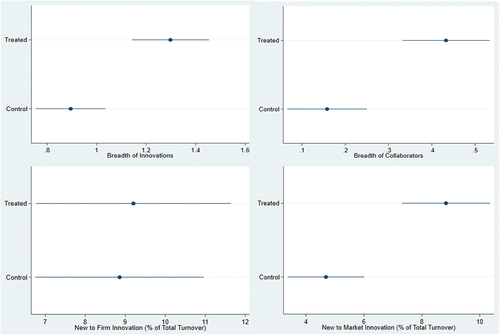

Turning next to treated firms facing knowledge and market obstacles, our results presented in Panel A (), and illustrated in , indicate that public financial support for R&I is also highly effective at helping firms facing such obstacles to carry out more R&I activities. A larger breadth of external partners for R&I collaborations can enable firms to benefit from external knowledge, which is critical for building knowledge resources (Antonioli, Marzucchi, and Savona Citation2017). From (Panel A), we find that public financial support for R&I enabled firms that faced knowledge obstacles, to increase their breadth of R&I collaborators, by 0.22 (p < 0.05). Moreover, a wider breadth of R&I activities indicates firms’ abilities to increase the number of R&I projects that they can manage at the same time, which can translate into superior learning effects (Leiponen Citation2012; Klingebiel and Rammer Citation2014). Here, our results suggest that public financial support for R&I resulted in an increase, on average, of 0.21 in the breadth of R&I activities undertaken by firms facing knowledge obstacles (Column 1, p < 0.05).

Figure 1. Impact of public financial support for R&I on the R&I activities of firms experiencing knowledge and market obstacles.

Regarding firms facing market obstacles, (Panel A) shows that public financial support for R&I has had a positive and significant effect on such firms’ new-to-market innovations (i.e. radical innovations). In this case, firms facing market obstacles increased their turnover from new-to-market innovations, by almost 3.5 percent (p < 0.01). These findings are in line with several studies that report public financial support for R&I to enable firms to expand their knowledge search activities, and achieve superior innovation performance (Clarysse, Wright, and Mustar Citation2009; Lee Citation2011, Wanzenböck, Scherngell, and Fischer Citation2013, Lenihan et al. Citation2023). Our combined findings thus strongly support Hypothesis 1, which stated that public financial support for R&I enables firms that face financial, knowledge and market obstacles, to engage more in R&I activities.

4.2. Public financial support and the importance that firms attach to their obstacles to R&I

We now turn our attention to whether public financial support for R&I impacts the importance that firms attach to their financial, knowledge and market obstacles. Our findings in Panel B of indicate that, as the treatment effects are not significant in most cases, firms that received public financial support for R&I attached similar levels of importance to their financial and knowledge obstacles. This is in comparison to firms who also faced obstacles, but who did not receive public financial support for R&I. Moreover, we find evidence which indicates that treated firms experiencing market obstacles in 2010, have increased the level of importance that they attached to these obstacles in 2016 (p < 0.05). Based on this, our findings do not support Hypothesis 2a, which stated that public financial support for R&I reduces the importance that firms attach to their obstacles. Our results provide some support for Hypothesis 2b, which stated that public financial support for R&I increases the importance attached to obstacles, in the case of market obstacles.

As discussed in Section 2.2, Hewitt-Dundas (Citation2006, 267) finds in a sample of manufacturing plants in Ireland that firms continue to experience financial and non-financial obstacles despite showing clear signs of ‘capability building’. This is in the sense of firms becoming more innovative, in terms of their probabilities to innovate, and the turnover that they generate from innovation. Hewitt-Dundas (Citation2006) concludes that this indicates that firms’ obstacles to R&I are likely to persist, despite firms reconfiguring their R&I resources and capabilities. Our findings support this view in the context of financial and knowledge obstacles. In the context of market obstacles, our findings are in line with D’Este et al. (Citation2012) and Coad et al. (Citation2016). These studies show that as firms become more innovative and productive, they tend to attach higher levels of importance to their obstacles to R&I. Our findings, therefore, indicate that public financial support for R&I enables firms to engage in R&I activities, despite their financial and non-financial obstacles. However, this does not translate into firms reducing the importance that they attach to their financial, knowledge and market obstacles.Footnote13

4.3. Heterogenous effects of different types of public financial support instruments on firms’ financial and non-financial obstacles

We now present the results of our analysis, when repeated for the three types of public financial support for R&I instruments, individually. More specifically, our analysis considers: (1) R&D grants; (2) R&D tax credits; and (3) Funding for academic-industry collaborations. From Panel A of , we observe that the positive and significant impact on firms’ levels of R&I investments, as reported in , only pertain to R&D tax credits and R&D grants (i.e. with impacts of 24.2 and 26.8 percent, respectively). A Wald test elucidates that R&D grants resulted in a larger impact on firms’ R&I investments in comparison to R&D tax credits, by around 3 percent (p < 0.05). In line with previous research on this topic (Becker Citation2015; Busom, Corchuelo, and Martinez-Ros Citation2014), this is likely to be because R&D grants increase firms’ levels of internal financial resources for R&I. In contrast to this, firms claim R&D tax credits to reduce the costs of R&I, after they perform these activities (i.e. R&D tax credits do not result in more financial resources for R&I ex-ante).

Table 9. Heterogenous effects of public financial support for R&I instruments.

Moreover, we find funding for academic-industry collaborations to have had no impact on the R&D investments of firms experiencing financial obstacles. This concurs with Bellucci, Pennacchio, and Zazzaro (Citation2016), who reported no input additionality effects of funding for academic-industry collaborations amongst firms in Italy. However, these findings differ from those of Scandura (Citation2016), who found that public funding for academic-industry collaborations increased R&D investments by firms in the UK. As noted by Cassiman et al. (Citation2018), firms may collaborate with academics in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) by outsourcing R&D activities that cannot be carried out internally. Therefore, funding for academic-industry collaborations may not necessarily increase firms’ R&D investments levels, but re-orient investments to specific research activities, such as applied research (Mulligan et al. Citation2022). Moreover, as noted in Section 3.2, R&D tax credits and R&D grants are targeted directly at firms, while funding for academic-industry collaborations does not provide a direct financial incentive to firms (Lenihan et al. Citation2023). Instead, the funding is allocated to academics in Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) to engage in co-funded collaborative R&D activities with firms. Based on this, our results indicate that public financial support for R&I can help firms facing financial obstacles to invest more in R&I, but only when targeted directly at firms.

In terms of knowledge obstacles, Panel A of provides evidence of R&D tax credits and R&D grants enabling firms experiencing such obstacles to increase their breadth of R&I activities (p < 0.10 and p < 0.05, respectively). Moreover, we find that R&D tax credits and R&D grants resulted in firms facing knowledge obstacles increasing their breadth of R&I collaborators, by an average of 0.3 and 0.2 collaborators, respectively (p < 0.05). In both cases, we do not find that funding for academic-industry collaborations enabled firms experiencing knowledge obstacles to engage in these R&I activities. Some previous studies have found that collaborating with academics in HEIs can bring important benefits to firms (Mulligan et al. Citation2022; Scandura Citation2016; Vanino, Roper, and Becker Citation2019). According to Hewitt-Dundas et al. (Citation2019), however, benefiting from such collaborations requires an initial learning process, by both firms and academics. Mulligan et al. (Citation2022) also demonstrate that the firm-level effects arising from such types of collaboration may take time to occur. This may help to explain why we do not find funding for industry-academic collaborations to help firms to engage in more R&I activities.

Finally, firms that experienced market obstacles and obtained R&D grants, have increased their turnover from new-to-market innovations (as a percentage of total turnover), by approximately 3.5 percent (p < 0.05). Our findings are consistent with Lee (Citation2011) and Beck et al. (Citation2016), who reported that R&D grants can encourage radical innovation in firms, which they define as new-to-market products and services. As noted earlier, this likely relates to R&D grants being typically focused on specific R&I activities that can result in more novel products and services (Afcha and Lucena Citation2022; Becker Citation2015; Neicu, Teirlinck, and Kelchtermans Citation2016). This is not the case for R&D tax credits. As discussed in Section 2.2, this may relate to firms using R&D tax credits for routine R&I activities, which may not translate into additional innovations in firms. Moreover, as noted above, funding for academic-industry collaborations may require a longer time horizon to result in innovation, which our data do not permit exploring.

The findings as outlined above, suggest that R&D tax credits and R&D grants have similar impacts in terms of enabling firms to engage in R&I activities, when experiencing financial and knowledge obstacles. Moreover, we also find R&D grants to be particularly effective at enabling firms that experienced market-related obstacles, to generate higher levels of turnover from innovation. In all cases, however, we do not find funding for academic-industry collaborations to have helped firms experiencing financial, knowledge and market obstacles to engage more in R&I

Finally, Panel B of adds further support to our findings in Panel B of . These findings show that treated firms continued to attach similar levels of importance to their obstacles, despite receiving public financial support for R&I. This happens regardless of the type of public financial support for R&I instrument that firms received. Furthermore, we find, on average, that firms facing market obstacles in 2010, and that engaged in publicly funded academic-industry collaborations, have increased the level of importance that they attached to such obstacles in 2016. We do not find that this was the case for R&D tax credits and R&D grants. This may relate to firms seeking to collaborate with academics in HEIs to explore potential R&I ideas at the early stages of the R&I process (Hewitt-Dundas, Gkypali, and Roper Citation2019; Mulligan et al. Citation2022). In doing so, firms may become more aware of their market obstacles (D’Este et al. Citation2012; Zahler, Goya, and Caamaño Citation2022).

4.4. Additional analysis (robustness tests)

To test the robustness of our findings, we repeat our analysis presented in , by using an alternative measure of firms’ obstacles to R&I in our matching process. More specifically, in a similar way to Galia and Legros (Citation2004), we construct a wholly new set of variables to measure firms’ obstacles to R&I, by means of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). Unlike explorative factor analysis, which is typically carried out by means of Principal Component Analysis (PCA), CFA seeks to ascertain whether the measures used correspond to the conceptual construct that we aim to measure (Gatignon Citation2014; Hurley et al. Citation1997; Koran Citation2020). As Mueller and Hancock (Citation2001, p. 1) specifically note, CFA ‘belongs to the family of structural equation modeling techniques that allow for the investigation of causal relations among latent and observed variables in a priori specified, theory-derived models’.

In the specific context of our study, CFA permits assessing whether the hampering factors in Appendix A map out to the headline variables used in our main analysis. To do this, we estimate the structural theoretical model presented in Appendix E. The results of this estimation are presented in Appendix F, showing that the sub-obstacles used (as obtained from the hampering factors in Appendix A), map out to our three main headline variables. This is because all factor loading coefficients, which indicate the correlation between the factors and the latent variables, are well above 0.85. This indicates a high level of correlation between the factors and the headline variables used (Cheung et al. Citation2023; Tavakol and Wetzel Citation2020). Following this, we use the predicted factor scores for the hampering factors in our matching routines. In other words, we replace the binary variables measuring firms’ obstacles to R&I as used in our main matching approach, with seven continuous measures of firms’ hampering factors (all in natural logarithm).Footnote14 Using continuous measures of firms’ hampering factors to R&I in 2010 improves the quality of our matching process. A limitation of this approach is that fewer firms can be successfully matched, given the additional precision required in the matching process.

Column 1 in presents the findings obtained with this alternative approach, when replicating the analysis presented in (i.e. measuring whether firms received any type of public financial support). Columns 2 and 3 do the same for the analysis presented in (i.e. for each type of public financial support instrument). Panel A of shows that the findings obtained with this alternative approach are very similar to the findings reported in Panel A of . Here, however, we observe two important differences. The first difference is that the impacts reported in Panel A of are larger, and in some cases more significant, in comparison to the same findings in (Panel A). We attribute this to an improvement in the quality of the matching process. The second difference is that funding for academic-industry collaborations now appears to have a positive and significant effect on firms’ breadth of collaborative partners (although only at the 10 percent levels of significance). We attribute this finding to the sample of treated firms being smaller (due to the additional matching restrictions) than the sample used for the analysis in . Upon more detailed investigation of this issue, we note that the composition of the matched sample is predominantly comprised of small-sized firms, who did not engage in academic-industry collaborations before receiving public financial support for R&I. This indicates that funding for academic-industry collaborations can potentially enable such firms to expand their breadth of collaborative partners. An investigation of the latter is however, beyond the scope of the current study. In terms of Panel B of , our results here are also very similar to our main findings as reported in Panel B of . Based on this, we conclude that the results from our additional analysis support the robustness of our findings of our main approach.

Table 10. Additional analysis with alternative obstacles variables.

5. Discussion and conclusion

Our paper analysed the impact of public financial support for Research and Innovation (R&I) on firms’ abilities to address their financial and non-financial obstacles to R&I. We achieved this by focusing on two key inter-related issues: (1) The extent to which public financial support for R&I enables firms that face financial, knowledge and market obstacles, to engage more in R&I; and (2) Whether public financial support for R&I reduces the importance that firms attach to such obstacles. Finally, we considered whether different types of public financial support for R&I instruments have similar or different effects in this regard. Using survey data from the Innovation in Irish Enterprises Survey (IIE, formerly Community Innovation Survey [CIS]), combined with novel administrative data on public financial support for R&I, our paper connects two highly related bodies of literature, that heretofore have remained highly separated (Mateut Citation2018). These are the literature concerning the effects that public financial support for R&I can have in firms, and the literature on firms’ obstacles to R&I. By boundary-spanning these literature strands, our paper sheds light on two issues which remain largely unexplored in such literatures.

The first issue pertains to identifying potential policy interventions to help firms with their non-financial obstacles to R&I. The use of public financial support for R&I as a means of helping firms with their financial obstacles to R&I is well established in the literature (Busom, Corchuelo, and Martinez-Ros Citation2014; Carboni Citation2017; Mateut Citation2018). To our knowledge, however, this is the first paper to analyse the impact of public financial support for R&I on the R&I activities of firms facing knowledge and market obstacles. In doing so, our paper demonstrates that public financial support for R&I can help firms that face financial obstacles to increase their R&I investments. Importantly, public financial support for R&I also prompts firms that face knowledge obstacles to engage in R&I activities that enable them to build R&I capabilities and resources. More specifically, we identified that public financial support for R&I can help firms that face knowledge related obstacles, to increase their internal knowledge sourcing activities (Autio, Kanninen, and Gustafsson Citation2008; Clarysse, Wright, and Mustar Citation2009; Yigitcanlar et al. Citation2019). Moreover, in a similar vein to Hottenrott and Lopes-Bento (Citation2014) and Antonioli et al. (Citation2017), public financial support for R&I can enable such firms to increase their breadth of collaborators. In terms of firms experiencing market obstacles, we find that public financial support for R&I can also enable such firms to generate higher levels of turnover from innovation (Beck, Lopes-Bento, and Schenker-Wicki Citation2016; Hewitt-Dundas and Roper Citation2010). Finally, based on our results, we identify R&D grants as the most appropriate form of public financial support for R&I instrument to achieve these goals. Drawing on earlier studies on this topic, this may be due to R&D grants enabling firms to perform more R&I activities internally, which they may not perform without this public financial support for R&I instrument.

The second issue pertains to investigating whether public financial support for R&I reduces the importance that firms attach to their financial and non-financial obstacles. In this case, our results suggest that despite amplifying firms’ R&I activities, public financial support for R&I does not reduce the importance that firms attach to the obstacles they face. In fact, it may result in firms being more likely to attach a high level of importance to their market obstacles. We attribute these findings to public financial support for R&I prompting firms to intensify their R&I activities (Radas and Bozic Citation2012; D’Este et al. Citation2014). This is in line with some previous studies, such as those of Galia and Legros (Citation2004), Hottenrott and Peters (Citation2012), and Lahr and Mina (Citation2021), which propose that as firms become more innovative, they are more likely to face financial and non-financial obstacles. We extend these earlier studies, by demonstrating that despite becoming more innovative, as a result of receiving public financial support for R&I, firms continue to attach similar levels of importance to their financial and non-financial obstacles. Therefore, based on our results, public financial support for R&I alone is insufficient to fully address firms’ financial and non-financial obstacles to R&I.

The above insights extend previous studies concerned with obstacles to R&I, including those of D’Este et al. (Citation2012), D’Este et al. (Citation2014), Antonioli et al. (Citation2017), Pellegrino (Citation2018), and Moraes Silva et al. (Citation2020), which posited that addressing firms’ non-financial obstacles requires a combination of micro and macro-level policies to target systemic failures. In addition, they extend the work of Mohnen et al. (Citation2008) and Pellegrino and Savona (Citation2017), who highlighted that public financial support may not necessarily lead to more R&I, if firms also face non-financial obstacles. This is because they demonstrate that firms may be able to develop additional knowledge for R&I and innovating more, when receiving public support for R&I, regardless of their knowledge and market obstacles. However, public financial support for R&I alone may be insufficient in terms reducing the importance that firms attach to their obstacles. Therefore, while important for helping firms facing financial and non-financial obstacles to engage in R&I activities, public financial support for R&I is not a silver bullet to fully alleviate such obstacles.