ABSTRACT

Reporting on a mixed methods study carried out in China, this article explores the impact of an educational initiative some years after delivery. Taking data from a three staged longitudinal study, this paper facilitates debate about the nature of Continuing Professional Development (CPD) delivered in a transnational context. To promote such debate a typology of impact is proposed. Using initial evaluation data the researchers designed a comprehensive and detailed evaluation tool to measure the long- term impact of the training. The researchers were interested in identifying whether participation in the learning programmes, designed to encourage social constructivist approach to teaching, had a sustained impact on teachers’ and whether these changes transferred into classroom practice. In an attempt to enrich research into transnational interventions such as this, an index of impact was produced and developed to create a typology for the evaluation of educational CPD when offered in an international arena.

Introduction: the China context

The Chinese government is promoting changes to the way teaching and learning is presented in China in order to prepare more students for success in the global knowledge-based economy of the twenty-first century (OECD Citation2015). Reforms to the way teaching is delivered are being introduced in an attempt to transform current Chinese education into a more student-centred approach (Chen Citation2014CitationHughes and Yuan, 2005). The ambition for transformation was first initiated in 2001 by the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China (MOE) and described as part of a concept of ‘student-oriented quality education’ (in Chinese Su Zhi Jiao Yu) in antithesis to the dominance of ‘examination-oriented education’ and representing a new guiding principle for education policies in China (MOE Citation2001).

In an attempt to transform teaching in its region from teacher-centred to learner-centred education, one district in the capital city developed an ‘internationalisation’ plan (CEA District Education Authority Citation2011), the aim of which was to provide educators in the district with exposure to state-of-the-art education training from around the world:

CEA intends to foster international education thinking and ideology … … through ‘internationalisation’, educators will broaden their vision and know more about courses and teaching modes of the international education so as to change their educating and teaching ideology. (CEA District Education Authority Citation2011, 3)

The intention of the plan was that every teacher and leader in the state sector in the district (kindergarten, primary school, junior middle school and senior middle school) was to receive a minimum of five days’ training. Give the population of China, it is important to note here the size of the endeavour. This was not a small intervention. The District in question covers an area of over 475 square metres and has the largest population of any region in Beijing of more than 3.5 million at the last calculation (https://all-populations.com/en/cn/population-of-chaoyang.html).

CEA needs to ensure all teachers and officials are covered by the internationally educational training. They will spare no efforts to foster professional quality teachers with high-standard morality, excellent skills, international vision as well as great passion. (CEA District Education Authority Citation2011, 4)

This article reports on progress with the plan and attempts to measure the long-term impact of the training that has taken place.

Why in-service continuous professional development (CPD)?

In-service CPD has high credibility in the Western world, with the research literature identifying its role in driving the improvement culture in schools. Further, it is acknowledged for the role it plays in maintaining and enhancing the quality of teaching and learning (Craft Citation2000; Harland and Kinder Citation1997; Harris Citation2001). Research has shown that professional development is an essential component of successful school-level change and development (Day Citation1999; Hargreaves Citation2012) and has confirmed that where teachers are able to access new ideas and to share experiences more readily, there is greater potential for school and classroom improvement. Evidence also suggests that attention to teacher learning can impact directly upon improvements in student learning and achievement. Where teachers expand and develop their own teaching repertoires and are clear in their purposes, it is more likely that they will provide an increased range of learning opportunities for students (Joyce, Weil, and Calhoun Citation1999). Further, the research literature demonstrates that professional development can have a positive impact on curriculum and pedagogy, as well as teachers’ sense of commitment and their relationships with students (Talbert and McLaughlin Citation1994).

Participation in CPD has been found to support teachers to stay in role, giving them confidence in their practice and the opportunity to share concerns and learn from others (Priestley et al. Citation2015). The very act of meeting other teachers in the same predicament, in an environment away from the school, allows for in-confidence conversations that can support the failing or tired teacher (Sachs Citation2003). Allowing teachers to attend training, at a distance away from the pressure of everyday teaching, as an independent professional can be empowering. The quasi-anonymity this creates, to share experiences in confidence, has been identified as a key element of successful school improvement (Gray Citation2000; Harris, Citation2001; Maden and Hillman Citation1996).

Contrary to the positive picture raised above, Guskey (Citation2000, 32) reminds us that many teachers perceive CPD to be irrelevant to their needs. He argues that we still know relatively little about its impact. Hu (Citation2005) makes a similar point in relation to the impact of CPD for teachers in China. To counteract this criticism, this research adopts three of Guskey’s identified levels of impact by focusing on Participant Learning, Participant Use of New Knowledge and Participant Development of Skills (Guskey Citation2000, 19).

The intervention

To facilitate its ambition for transformation to the way teachers teach in one specific region of China, one local authority region commissioned the Institute of Education in China’s capital city to manage the training. As a result, educationalists from around the world (Australia, Belgium, Canada, Finland, Germany, Ireland, Japan, New Zealand, UK, USA) delivered over 2205 training courses in a range of subjects: managing a school choir, stage management, leadership, developing literacy for kindergarten teachers, alongside specific training in subjects such as Science, Technology, Engineering, Art and Maths (STEAM), Physical Education and more generic training (for example, thinking skills), to more than 10,000 teachers and leaders. The requirement was that all training be delivered using Western teaching approaches as shaped by the social constructivist theoretical model (Vygotsky Citation1978). In making this explicit, those commissioning the teaching clearly identified a need for the visiting academics to model non-didactic and interactive teaching approaches.

Quantitative data were collected at the end of each training period along with data from focus group discussions. These data were used for quality assurance purposes in terms of future commissioning of the training and to feed back to the trainer. During the training period, a quality audit visit was carried out by a member of staff from the Institute of Education to ensure that the training was meeting the commissioned requirements. At the close of the five-year training period, all evaluation data were collated using a thematic approach and key issues were identified. However, as these data provided an immediate response to the training rather than providing a more considered evaluation of impact, more research was proposed. An impact study was mandated to identify whether there had been any transformation in the participants’ teaching strategies towards a commitment to learner-centred education. The extent of the data collected for this research is set out in . The ambition was to create a typology of impact in relation to international CPD provision. The aim was to confirm whether expressions of approval for the constructivist thrust of Western teaching, as evidenced in the QA evaluation mentioned above, translated into changed practice.

Table 1. Number of research participants by research method

Research design

A phenomenological approach was adopted as the approach generally used to investigate subjects’ perceptions of a phenomenon and is thus ideal for creating typologies based on opinion or attitude (Netolicky and Barnes Citation2017; Punch Citation2016; Robson Citation2015). Clearly, the research project did not lend itself to a quantitative methodology; rather, an ethnographic approach was appropriate. Phenomenological approaches, as part of the ethnographic school of research, seek to describe the ‘essences’ of objects (Arthur, Citation2012) and, within the field of phenomenology, the area of phenomenography is particularly of interest. Phenomenography is less interested in ‘essences’ and instead is focused on the perceptions of reality ‘in a limited number of qualitatively different ways’. It is thus a ‘second order’ perspective of the world. It was our view that phenomenography, a methodology which is useful in identifying differences and categories resulting from subjects’ varying perceptions, would produce a rich range of responses, and so enrich any typology under construction (Willis Citation2017).

Marton (Citation1986) developed phenomenography as a qualitative research theoretical framework, and this framework has since been used to investigate thinking and learning in education. Research of this kind is generally carried out through semi-structured, individual, oral interviews, although other forms of discourse may also be used. Marton’s idea of phenomenography is essentially realist with interviewees’ accounts taken as interpretations of reality. The perspective of the interviewee is part of a complex relationship between that which is experienced and those who have participated in the experience.

As the research was carried out by staff from the Institute which commissioned the training, and indeed had sight of the initial evaluations, it is important to see the research as a dialogue based on professional trust between the researcher and those being researched. The approach adopted was an ideal way of allowing learner voice and reflection to come to the fore and is a model way for supporting the creation of a typology such as the one proposed here (Bradbury-Jones, Herber, and Taylor Citation2014; Thomas Citation2004). Prior to commencement of the research, a detailed proposal was submitted to the Institute of Education research committee and the research project given full approval to proceed.

Research method

This research set out to design, develop and propose a typology to identify the impact of internationally focused CPD. The research was carried out by one lead researcher and three support interviewers who were trained in interviewing techniques. Prior to the commencement of the research, a comprehensive document outlining the research design and protocols was approved by the ethics committee of the commissioning institute in China.

The research design was framed in the interpretative domain as the intention was to understand better the impact of the training on the individuals who had participated in it (Arthur et al. Citation2012). This article reports on a four-stage evaluation process as set out in . Firstly, the initial evaluation of the extensive training intervention coupled with the audit reports from the quality assurance activities carried out by Institute staff were analysed. The collated data were used to inform the design of the second research tool (a questionnaire) followed by an extensive interview with 14 course participants. This interview was broadly unstructured to avoid imposing researchers’ preconceived ideas on the resulting typology (Wilson Citation1981) with the ambition of counteracting the potential critique of subjectivity as often levelled at research which adopts a phenomenological frame (Thomson and Palermo Citation2014).

A range of schools, including primary, junior middle and senior middle schools, which had participated in the training programme were identified and head teachers were approached for permission to contact participants for feedback on the impact of the training on their professional lives. Five schools responded positively, and questionnaires were sent to the schools for completion (Appendix 1). The questionnaires provided the respondents with the rationale for the research. Open-ended questions focused on three broad areas: knowledge, skills and competence (see ). This categorisation was determined following the models proposed by the Commission on Higher Education (Citation2014) when designing a typology for outcome-based education. Further, the researchers felt justified in applying these themes to the research design as all training sessions had focused, in varying degrees, on theoretical knowledge associated with learner-centred teaching, the skills required for planning such approaches and the personal competence and confidence of the teachers (see ). Further, these broad categories form the basis of the typology of interventions proposed in a study carried out by the Teacher Development Agency in England (TDA Citation2010) and also echo Guskey’s impact levels, as previously referenced (Guskey Citation2000).

This broad categorisation provided an initial set of general types, although the likelihood that additional categories which might arise was not excluded. The questionnaire included text assuring participants of confidentiality. A copy of the questionnaire is included at Appendix 1.

One hundred and twenty-five questionnaires were returned from the five schools which had agreed to participate. However, the returned questionnaires varied considerably in quality; some providing very little information and others rich in reflection. The most fully completed were identified as a good source of feedback on impact, although a few who did not fully complete, but made critical comments, were also included in order to get as broad a range as possible. Fourteen respondents identified an interest in taking part in further research and these were identified and contacted in order to arrange interview appointments. Data collected from the questionnaires were analysed and coded to enrich the design of the interview schedule. Here the interviewees were asked questions about their use of the teaching strategies they had seen modelled in the training.

The data from the questionnaires were thoroughly analysed and coded according to the criteria set out in . What became apparent during this process was that the respondents felt moved to record the benefits of their engagement with frequent references to their personal development such that the researchers felt it important to add another category of interest, namely personal development (see ).

The addition of the focus on ‘Personal Enrichment’ implies that, as intended by the District who sponsored this research (see previous quote from CEA), there has been a shift in ideology, and increase in passion and inner belief in education in the District. It was important to test this out during the interview process.

The research interview

Up to this point, the research had been led by an English national living in China, with experience of working in the Chinese language, with support from her native-speaking colleagues to translate the questionnaire into Chinese. To carry out 14 in-depth interviews, support from colleagues was sought through a process of identifying Chinese-speaking staff members of the Institute of Education who felt confident to carry out research interviews. These interviewers then attended a training session on carrying out non-intrusive interviews of the kind used for grounded theory/phenomenological research (Arthur, Coe, and Hedges Citation2017). The training included input on questioning techniques as well as role play activities focusing on avoiding leading questions. In addition, a protocol for interviews was developed by the team to ensure standardisation of interviews.

The objective of the interview was to bring informants to a state of meta-awareness. This has clear ethical implications which were discussed during the training given to those who carried out the interviews (Punch Citation2016). In addition, it was recognised that an approach was needed which takes into account the social relationship between the researchers and their informants and the constructed nature of the research interview (Avis Citation2012). With this in mind, respondents were assured that all conversations would be confidential.

Interviews were carried out in schools in private rooms, with a strong emphasis on making interviewees feel at ease and creating an atmosphere where they could express any ideas they wanted to. Three interviewers visited five schools over the period of a month. They introduced themselves as members of the International Department of the Institute of Education and asked permission to record the interview whilst at the same time assuring participants that records would be confidential. Interviews lasted from 15 to 30 minutes and were carried out in Chinese.

Interview recordings were then listened to by two analysts (one a native Chinese speaker, the other a native English speaker with intermediate-level Mandarin Chinese), and all references to impact of any kind were identified and noted. A table was produced after the first recording was analysed, and this was extended through an iterative process. Once all mentions of impact had been noted, the responses were reorganised into new categories – these arose from the interviews and were different from the original categories used in the initial questionnaires (knowledge, skills, competences, personal development). These new categories formed the basis of the emerging typology.

Measuring impact

Most impact studies investigate whether an intervention of some kind has an effect. A common type is an environmental impact study. Such studies often use a range of data and look at a variety of aspects. The study could indicate whether a project has been successful, complete or requires additional funding. It is common for funding agencies to carry out impact studies to justify expenditure, either retrospectively or for future activities. This is often the case for education initiatives, both for aid-funded projects and for government-funded activity. Guidelines are often produced to ensure that impact is assessed in an appropriate way, although these are often strongly influenced by institutional agendas.

In the UK, the aid agency, OECD and the TDA carry out and encourage large- and small-scale impact studies to evaluate education development projects. The OECD has published stringent guidelines on carrying out impact studies:

Impact evaluation serves both objectives of evaluation: lesson-learning and accountability.

(OECD Citation2015, 1–2)

An example of such an OECD project is ‘The Role of Teachers in Improving Learning in Burundi, Malawi, Senegal and Uganda (Akankshay Citation2010). This research, however, is based on a clear and specific outcome, the improvement of learning outcomes, something which is not specifically stated in the CEA District training programme, with the ambitions for the programme described in terms of changes to teachers rather than improved outcomes for learners (see previous quotations from CEA documentation). This also makes it difficult to decide which bits work and which do not, and almost impossible to evaluate why and how the programme works.

The Teacher Development Agency (TDA) in the UK provides guidelines for carrying out impact studies (TDA Citation2010). In this case, it is an impact study model. According to their guidelines, the impact evaluation model is designed to help schools build up a picture of how they expect a project, initiative or service to work.

Working through the model will clearly demonstrate the links between the various stages of service delivery, from planning all the way through to the impact on individual service users (for example, boosting their confidence and self-esteem) and on the overall project aims. (TDA Citation2010, 3)

The model is made up of guidance, a set of practical team exercises and ongoing TDA support. Again, this model is of little relevance to the investigation as an impact study was not built into the overall design of the project.

Further, academic studies have investigated the effects of teacher training. For example, Impact of Training on Teachers Competencies at Higher Education Level in Pakistan (Aziz and Akhtar Citation2014). A number of graduate students also use impact as the focus of research: a Korean graduate student at Warwick University wrote the following thesis: The Impact of In-Service Teacher Training: A Case Study of Teachers’ Classroom Practice and Perception Change (Sim Citation2011), in which the author makes suggestions about the desired impacts of in-service teacher training: increasing teacher knowledge, build positive attitudes and beliefs, improve teaching practices.

Privately funded activity is often evaluated by means of impact study. In China, Cambridge English Language Assessment carried out a collaborative study on the impact of exams for schoolchildren in China. Working with researchers led by Professor Xiangdong Gu of Chongqing University, the Cambridge team focused on the perceptions held by parents of the impact on Chinese students of two qualifications, namely the Cambridge English: Key (KET) for Schools and Cambridge English: Preliminary (PET) for Schools (Edwards and Daguo Citation2011).

The Cambridge Assessment Impact study was based on classroom observation and interviews with over 140 parents, mainly mothers, who were waiting for their child to sit an exam at a test centre. The results of the research were published in University of Cambridge Research Notes 50 (CitationGu and Saville, 2012). The main conclusions were that the two qualifications mentioned above both encourage the early acquisition of English language skills and that parents prefer their children to attend training centres but are concerned about the inconsistent quality of such institutions. Again, this type of research has little to offer the context under examination in this study, as a clear idea of expected impact had been identified from the outset.

So, what best practice can be ascertained to help with the carrying out of the current investigation of impact from these studies? The OECD guidelines recommend a comparative study using a control group which has not been exposed to the intervention. Such impact studies often use quantitative data to measure a closely defined effect. In the following research, teacher competences are defined and measured in teachers who have received training and those who have not, allowing for comparative analysis. Aziz and Akhtar’s research, mentioned previously, on the impact of training on teacher competences uses similar research methods which also allow for the measurement of differences (Aziz and Akhtar Citation2014).

The TDA model (TDA Citation2010), as previously mentioned, gives more user-friendly guidelines for those who are essentially not engaged in research as a matter of course. These encourage a more inclusive approach to carrying out the research:

Using the impact evaluation model will give you a holistic view of how an intervention is working and will enable you to build a persuasive case for its impact, based on both qualitative and quantitative evidence. (TDA Citation2010, 3)

The problem with both of these guidelines is that they leave little or no room for the incidental impact, the unexpected impact, the negative impact, all of which may be of considerable importance to the individuals and institutions involved in a particular project.

Even where expected outcomes have not been specified at the beginning of a project and assessment looks for possible impact, the design of the impact study usually reflects the expectations of the researchers. The result is that many potential areas of impact are overlooked. This research aims at overcoming these problems by doing an initial investigation of the range of different impacts which are possible, including the unexpected and the negative. Once this typology of impacts is complete, further research into the extent of particular types of impact can be discovered.

In much research, findings are mapped to an existing typology or to a typology produced by researcher analysis of a situation or set of data. A typology may not result from research; it may simply be a system devised according to conceptual categories to perform some kind of competence as in ‘A Typology of Teaching for Use in Teacher Education’ by Wilson (Citation1981). This typology is a series of teaching strategies placed on a continuum based on interaction patterns, control of content and control of pace. The range of strategies was reached, not through research, rather through a logical analysis of variables. However, this type of typology is subject to the expectations and perceptions of the designer and may miss important categories.

An alternative to this is a typology based on research to identify the areas of potential interest. In ‘Science Teachers’ Typology of CPD Activities: A Socio-constructivist Perspective’, EL-Deghaidy, Al-Shamrani, and Mansour (Citation2015) identified themes and patterns, using thematic analysis to find repeated patterns of meaning. The study was carried out in two stages: the first through open-ended questionnaires followed up by structured interviews. The various types of teacher training activity were subject to an evaluation of teacher preferences – how much they liked the different types identified (EL-Deghaidy, Al-Shamrani, and Mansour Citation2015).

Given the problems identified above in locating a typology to frame this research which was research informed, located in practice, linked to the impact of CPD and with an international world view, the researchers decided to propose a typology for use in future research.

Research outcomes

Following the systematic and themed analysis of all the data collected for this research project the researchers identified eight broad categories of impact, namely: teaching activity; attitude to teacher/learner centredness; personal CPD; department CPD; school CPD; school administration; personal life; impediments to impact. Some of these categories were further broken down into more specific areas (see Appendix 2). These areas did not fall easily within the predicted areas of ‘knowledge’, ‘skills’ and ‘competences’, which had been used to structure the initial written questionnaires. New general categories of ‘attitude to and practice of teaching/learning’, ‘involvement/engagement in continuing professional development’ and ‘personal relationships’ represent the three broad areas of interest which developed as a result of the data analysis.

Respondents talked passionately about changes made to the way they teach with the adoption of strategies used in the training. They identified a greater focus on experiential learning, application of teaching tools such as games, role play (coffee shop for language teaching) and cooperative learning techniques. In terms of their development, they were using improved questioning techniques and offering learners more self-help tools to increase their engagement in learning. One interesting comment was that the ‘teacher–student relationship was more equal’, while other teachers talked about improved relationships in the classroom, an ability to see things more from the perspective of the learner and allowing students to talk more.

Mention was made of the use of learning outcomes to frame periods of learning and changes in lesson design to give greater focus to individual learning needs. The teachers showed an interest in educational theory reporting a new focus in teaching methods and a desire to engage in additional training courses. A number of teachers expressed an interest in improving their level of English. This may be because all training was delivered in English with support from a qualified translator.

Impact on team working was noted, with improved relationships at a departmental and organisational level. Mention was made of a more collegial atmosphere with senior management being more open and interested in providing better resources. It is important to note here that senior managers were required to attend leadership training, and those engaged in leadership training were included in the sample of teachers who were sent the questionnaire, with two school leaders represented in the sample of candidates selected for interview.

In the category of ‘knowledge’, there was an interesting and somewhat mysterious lack of comment. It may be that an increase in knowledge from training in China is a given, so participants did not talk much about this. On the other hand, it may be that knowledge is not so impactful. It is feasible that because the training mirrored interactive teaching approaches and aimed at an innovative, experiential design, the recipients did not perceive their CPD as being of the traditional knowledge-based variety usually presented, and so did not consider their experience as falling within any epistemological categorisation. Before drawing any conclusions in this area, further investigation is required to achieve clarity. This does highlight one of the problems of researching international activities such as these where the CPD programme and also the research data are subject to translation and may well be impacted by cultural differences and understandings.

The most interesting impact identified was probably the effect of attending a training course on family life. A number of teachers mentioned that they had changed the way they were bringing up their own children. This, we maintain, represents a strong commitment and belief in the Western approaches which were demonstrated. Further research on whether or not this correlates to a change in teaching activity may shed light on whether constraints from the education system (as identified below) are inhibiting the effects of training.

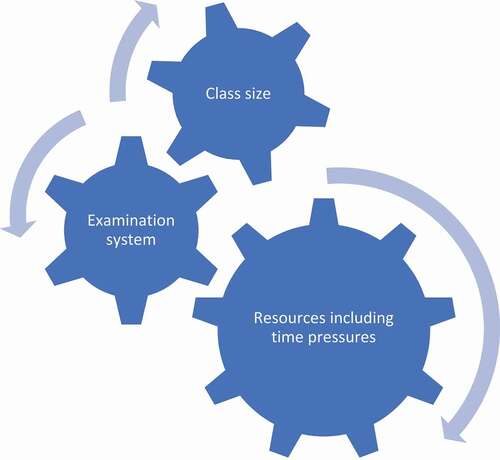

Within the area of impediments to impact, the teachers mentioned class size, the prevalence of examinations, time pressures, the demands of the curriculum and lack of facilities. Interestingly, this list of issues is very similar to those recorded in research carried out in the UK which reported on a large-scale project aimed at transforming teaching and learning in the college sector (Browne, Sargeant, and Kelly Citation2008). As in the UK, the researchers feel that any project designed to achieve transformational change cannot just target teachers and their teaching approaches. If CPD is to be impactful, it needs to be designed alongside other interventions such as changes in examination policies, and with the addition of new funding models to purchase resources to support the implementation of the desired change.

The interview data revealed some interesting insights and indeed provided for the broadening of categories in the design of the typology. illustrates the development of the typology from three, then four initial categories to the identification, with four localities of interest, to eight domains of positive impact, remembering that any typology provides an interpretative framework to stimulate reflection, discussion and further research (Avis Citation2012). then identifies the areas raised that might inhibit the change process and restrict the potential for impact.

illustrates the impediments to change as identified by the respondents in the research.

The categories identified in alongside the identified ‘blockers’ as shown in form the basis for the proposed immerging typology to be refined and applied to further research interested in evaluating the impact of international CPD.

Recommendations

Further research should be carried out in two broad areas. Firstly, the typology requires further testing in an international context other than China. This is specifically as teachers failed to identify negative impact to teaching and learning during the interviews, focusing only on organisational issues such as exams, probably because they identified the researchers as having ‘ownership’ of the project and did not want to cause offence. This may be an issue that is culturally embedded in the psyche of Chinese educationalists, and so requires additional investigation. There will certainly be some negative impact so this needs to be investigated systematically. Another gap in the typology is the role of increased knowledge. The reasons why teachers failed to identify knowledge when talking about impact could be because they take it as read, but, nevertheless, more research in this area would be of value.

The second broad area for further investigation is to produce more focused research on specific areas of the typology. In addition, other players not included in the CPD provision such as schools or education authority administrators may find areas of interest within the typology. The identified areas may offer a framework for the production of school plans. Where problem areas have been highlighted here as blockers (see ), future planning, classroom design and resource allocations may be enhanced by consideration of the views represented here. Further, where teachers find that training has impacted on the way they treat their own children, it would be interesting to know how widespread this is and whether, in the long term, they had the confidence to translate these practices into their teaching, and if not, why not?

Conclusion

The rationale for this research was to carry out in-depth impact research into an extensive programme of CPD delivered with an international flavour. As a result, a typology was created which could be used as a starting point for further research into the impact of current and future internationally focused teacher training programmes. To this extent, the research was successful in finding a range of impacts from participants’ perspectives. Further investigation of impact from the perspective of other stakeholders would, however, add to the depth of the typology. Local education authority staff, head teachers, administrators and other partners in continuing professional development as well as learners could also provide valuable insight into impact.

In addition, although informants did mention impediments to impact experienced once they were back in school, an important omission from the final typology created out of this research is the lack of negative impacts in classroom practice. This is probably because of a general reluctance by informants to criticise upwards in a hierarchical structure in China (Chen Citation2014). It would be useful to carry out a further piece of research focusing on negative impact in order to get a broader spread of impact types.

In general, impacts identified related less to teacher skill and competence, which was an initial expectation, and more to the way in which colleagues work together in school. This perhaps indicates that teachers’ involvement in the school community is a high priority and therefore, something that they value more highly than individual development. However, there were some interesting impacts at an individual level. For example, the way in which the experience of taking part in the internationalisation training not only stimulated interest in education methodology but also added to the value of other local training.

As mentioned earlier in this article, personal impact was also identified although the study had originally focused on the impact on teacher’ professional lives. Some teachers said that they were now bringing up their own children differently, which indicates a change in ideology. It would be of value to investigate this further and find out whether teachers who experience this change in belief also change the way in which they teach and if not, what the impediments to doing this are.

The typology stands as a starting point to identify and frame indicators of success for those planning professional learning experiences and wanting to achieve a comprehensive and meaningful evaluation so that future professional learning provision can generate quality instructional practice and improved student learning.

The typology can also be used to identify the optimal impact of future training and incorporate the means of measuring the quality of impact, thereby identifying the success and failure and indeed the causes of success or failure of future internationally focused training provision.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Liz Browne

Dr Liz Browne is a Professor of Education working in the Centre for Educational Consultancy and Development (CECD). As an educationalist she has held senior posts in a number of secondary schools and in the Further Education sector. Liz is an active researcher having articles published in prestigious journals on issues such as data management, the early years standards, ICT and student voice. Her work is now focused on international partnership, delivering training in China and to visiting academics from China, Saudi Arabia and Russia.

Chris Defty

Chris Defty is a retired education specialist working on training for Chinese teachers.

Na Guo

Na Guo, Kai Hou, Dan Wang and Lu Zhuang are all faculty members at Teacher Development, Beijing Institute of Education, Beijing, China.

Kai Hou

Na Guo, Kai Hou, Dan Wang and Lu Zhuang are all faculty members at Teacher Development, Beijing Institute of Education, Beijing, China.

Dan Wang

Na Guo, Kai Hou, Dan Wang and Lu Zhuang are all faculty members at Teacher Development, Beijing Institute of Education, Beijing, China.

Lu Zhuang

Na Guo, Kai Hou, Dan Wang and Lu Zhuang are all faculty members at Teacher Development, Beijing Institute of Education, Beijing, China.

References

- Akankshay, K. 2010. “The Role of Teachers in Improving Learning in Burundi, Malawi, Senegal and Uganda: Great Expectations, Little Support – The Improving Learning Outcomes in Primary Schools (ILOPS) Project.” Research Report on Teacher Quality, ActionAid.

- Arthur et al. et al. 2012. Unpublished research presented at internal teaching and learning conference 2012 Oxford, Oxford Brookes University.

- Arthur, J. M., W. R. Coe, and L. Hedges. 2017. Research Methods and Methodologies in Education. London: Routledge.

- Avis, J. 2012. Research and Research Methods in Education. London: Sage.

- Aziz, F., and M. Akhtar. 2014. “Impact of Training on Teachers Competencies at Higher Education Level in Pakistan.” Researchers World 5 (1): 222–234.

- Bradbury-Jones, C., O. Herber, and J. Taylor. 2014. “How Theory Is Used and Articulated in Qualitative Research: Development of a New Typology.” Social Science & Medicine 120C: 135–141. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.09.014.

- Browne, E., M. Sargeant, and J. Kelly. 2008. “Change or Transformation? A Critique of A Nationally Funded Programme of Continuous Professional Development for the Further Education System.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 324 (November): 427–439. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03098770802538145.

- CEA District Education Authority. 2011. “Education Development Scheme during the Twelfth Five-Year Period in CEA District, Beijing.” CEA District Commission of Development and Reform of Beijing Municipality. Vol. 12. CEA District Education Authority .

- Chen, S.-H. 2014. The Confluence of Academia and Industry: A Case Study of Innovation Systems. Review of Policy Research. New York: Fulton.

- Commission on Higher Education. 2014. Handbook on Typology for Outcome Based Education. London: Department for Education.

- Craft, A. 2000. Continuing Professional Development: A Practical Guide for Teachers and Schools. 2nd ed. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

- Day, C. 1999. “Professional Development and Reflective Practice: Purposes, Processes and Partnerships.” Pedagogy, Culture and Society 72: 221–233. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14681369900200057.

- Edwards, V., and L. Daguo. 2011. Confucius, Constructivisim and the Impact of Continuing Professional Development on Teachers of English in China. London: British Council.

- EL-Deghaidy, H., S. Al-Shamrani, and N. Mansour. 2015. “Science Teachers’ Typology of CPD Activities: A Socio-Constructivist Perspective.” International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education 5: 245–252.

- Gray, J. 2000. Causing Concern but Improving: A Review of Schools’ Experience. London: Department for Education and Employment.

- Gu, X., and N. Saville. 2012.” Impact of Cambridge English: Key for Schools and Preliminary for Schools – Parents’ Perspectives in China.” University of Cambridge Research Notes 50: 48–56.

- Guskey, T. 2000. Evaluating Professional Development. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Hargreaves, D. H. 2012. A Self-Improving School System in International Context. Nottingham: National College for School Leadership.

- Harland, J., and K. Kinder. 1997. “Teachers’ Continuing Professional Development: Framing a Model of Outcomes.” British Journal of In-service Education 231: 71–84. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13674589700200005.

- Harris, A. 2001. “Building the Capacity for School Improvement.” School Leadership and Management 213: 261–270. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13632430120074419.

- Hu, G. 2005. “Professional Development of Secondary EFL Teachers: Lessons from China.” Teachers College Record 107 (4): 654–705.

- Hughes, I., and Yuan, L. 2005.“The status of action research in the People’s Republic of China.“ Action Research 3 (4): 383–402.

- Joyce, B., and E. Calhoun, et al. 1999. Models of Teaching: Tools for Learning. Phoenix: The Phoenix Alliance.

- Maden, M., and J. Hillman. 1996. Success against the Odds. London: Routledge.

- Marton, F. 1986. “Phenomenography – A Research Approach Investigating Different Understandings of Reality.” Journal of Thought 2 (212): 28–49.

- MOE (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China). 2001. “Student-Oriented Quality Education.” Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China 5 .

- Netolicky, D., and N. Barnes. 2017. “Method as A Journey: A Narrative Dialogic Partnership Illuminating Decision-Making in Qualitative Educational Research.” International Journal of Research and Method in Education 6 (2): 235–246.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2015. Education in China – A Snap Shot. Brussels: OECD Publications.

- Priestley, M., G. J. J. Biesta, S. Philippou, and S. Robinson. 2015. “The Teacher and the Curriculum: Exploring Teacher Agency.” In The SAGE Handbook of Curriculum, Pedagogy and Assessment, edited by D. Wyse, L. Hayward, and J. Pandya. London: SAGE Publications p 122 .

- Punch, R. 2016. “Doing Your Research Project: A Guide for First-Time Researchers.” UK Higher Education OUP Humanities & Social Sciences Study.

- Robson, C. 2015. Real World Research. London: Sage.

- Sachs, J. 2003. The Activist Teaching Professional. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Sim, J. Y. 2011. “The Impact of In-Service Teacher Training: A Case Study of Teachers’ Classroom Practice and Perception Change.” Thesis, University of Warwick.

- Talbert, J. E., and M. W. McLaughlin. 1994. “Teacher Professionalism in Local School Contexts.” American Journal of Education 102 (2): 123–153. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/444062.

- TDA (Training Development Agency for Schools). 2010. “Impact Evaluation – A Model, Guidance and Practical Examples.” Training and Development Agency for Schools 12: 230 .

- Thomas, G. 2004. “A Typology of Approaches to Facilitator Education.” Journal of Experiential Education 2 (5): 345–357.

- Thomson, M., and C. Palermo. 2014. “Preservice Teachers‘ Understanding of Their Professional Goals: Case Studies from Three Different Typologies.” Teaching and Teacher Education 44: 56–68. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.08.002.

- Vygotsky, L. 1978. Mind in Society. London: Harvard University Press.

- Willis, A. 2017. “The Efficacy of Phenomenography as a Cross-Cultural Methodology for Educational Research.” International Journal of Research and Method in Education 5 (1): 483–499.

- Wilson, L. 1981. “A Typology of Teaching for Use in Teacher Education.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 6 (2): 345–351. doi:https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.1981v6n2.1.

Appendix 1. Impact questionnaire

As part of the local Institute of Education’s work, we are conducting research into the impact of the Chaoyang District Internationalisation Programme. The research will identify the types of impact that teachers and schools are experiencing following internationalisation training. This will enable us to focus attention on areas which need further research and/or support in future training.

Thank you very much for your contribution to this research. Your response to this questionnaire is completely confidential.

What were your expectations of this training?

Do you know why you were chosen to attend this training? Yes/No If ‘Yes’, why?

Can you identify any teaching strategies you gained from attending the training?

Yes/No. If ‘Yes’ please list below

Do you consider that the training met your needs?

Did participating in the training affect the way you think about teaching and learning in any way? If ‘Yes’, how?

Has the training had a permanent effect on the way you teach – Yes/No.

If ‘No’ then please explain why not. If ‘Yes’, please give details on the way your approach has changed.

Have you been required to disseminate aspects of the training to your colleagues? If ‘Yes’, how?

Has your attendance at the training benefitted your school and/or learners other than those you teach? Yes/No. If ‘Yes’ please give examples.

Thank you for participating in this survey. It will help us to understand how the internationalisation program has affected teaching and learning in Chaoyang District schools. We will be carrying out follow-up interviews and hope very much that you will be willing to participate. Again, your responses will be in complete confidence. Please give us your contact details so that we can contact you.

Wechat:

Mobile: