ABSTRACT

Make-believe play (MBP) provides kindergarteners with an authentic form of engagement that is particularly favourable to the development of oral and written language. As part of an action research study, an activity-oriented professional development (PD) program incorporating video was established to provide kindergarten teachers with guidance on their teaching practices in MBP situations. The findings show changes in the participant’s PD trajectories. These findings provide direction as to how teachers who wish to implement more MBP practices in the classroom to promote language development in children can be supported within the framework of such a program. For instance, the results match those of previous research as regards whether a program that uses evidence such as videos would be more effective in leading a participant to effect changes in their PD. The results also indicate that PD programs cannot be exclusively collective or individual, but benefit from combining the two approaches.

Research problem and topic

Teachers’ practices to support oral and written language development in make-believe play

Several studies have found a positive link between make-believe play (MBP) and the development of children’s oral and written language skills (Germeroth et al. Citation2019; Hirsh-Pasek et al. Citation2009; Lillard et al. Citation2013; Montie, Xiang, and Schweinhart Citation2006; Pellegrini et al. Citation1991; Roskos and Christie Citation2001; Tamis-LeMonda and Bornstein Citation1990), making MBP the ideal backdrop for supporting the development of these skills in kindergarten classrooms.

Although there is growing evidence in the scientific literature of the benefits of MBP at the kindergarten level, there are still two competing pedagogical approaches to supporting oral and written language development: the developmental perspective, which focuses on developing language skills through play, and the systematic instruction perspective, which focuses on explicitly developing these skills through structured, directed activities (Bouchard et al. Citation2015; Brougère Citation2010; Chambers, Cheung, and Slavin Citation2016; Conseil supérieur de l’éducation Citation2012; Hall et al. Citation2015). As a result, the place that play occupies in kindergarten classes varies widely (Miller and Almon Citation2009; Nicolopoulou Citation2010; Stipek Citation2006; Trawick-Smith Citation2012; Zigler, Singer, and Bishop-Josef Citation2004). Furthermore, many teachers report having misconceptions about, and experiencing challenges in, supporting children’s learning and development in play situations (Pyle, Prioletta, and Poliszczuk Citation2017; Wood and Chesworth Citation2017).

One of the most common misconceptions is that play is often thought of as a reward for children who have finished a task or as an activity that is incompatible with the goals of the curriculum (Bodrova and Leong Citation2012; Brougère Citation2010; Marinova and Drainville Citation2019; Nilsson, Ferholt, and Lecusay Citation2018), and thus little time is devoted to it. In order to get a better understanding of their ideas about MBP and enhance their classroom practices, and ultimately promote oral and written language development in children, it seems relevant to provide teachers with guidance on their teaching practices in classroom MBP situations.

Professional development as a vector for changes in teachers’ oral and written language practices in MBP situations

Professional development (PD) programs are key to changing and improving teaching practices (Darling-Hammond et al. Citation2005; Desimone Citation2009), including practices to support children’s oral and written language development in MBP situations. Based on the growing literature on PD programs in teaching and other professions, we can identify which programs are the most effective for changing practices in order to guide this study.

In a meta-analysis, Blank and de las Alas (Citation2009) found many significant correlations between the effectiveness of PD programs and the engagement of teachers in learning, both their own and that of their students. Among other things, they found significant links with programs that were content focused, used collaborative participation, were consistent with the teachers’ needs and concerns, were of sufficient duration and frequency (lasted for several months) and encouraged the teachers to learn actively (Blank and de las Alas Citation2009).

Similarly, Desimone (Citation2009) determined that the most effective PD programs had five characteristics. They: 1) were content focused, 2) promoted active learning, 3) were coherent, 4) were of an extended duration, and 5) used collective participation. Wood and Stanulis (Citation2009) also propose six criteria for effective teacher PD that are consistent with the research of Blank and de las Alas (Citation2009) and Desimone (Citation2009): it should 1) focus on critical problems of practice, 2) occur often enough and be long enough to ensure knowledge and confidence are progressively acquired, 3) provide opportunities for teachers to reflect and engage in reflective problem solving to explore answers to their questions, 4) focus on student learning and the context in which it takes place, 5) encourage collaboration to create a community of practice where teachers can address issues of concern to all of them, and 6) emphasize learning as the centre of teaching by encouraging teachers to pursue PD so they can tackle problems that arise in class. Lastly, the greater the diversity of activities and approaches in a PD program, the more likely it is that the program will meet the needs of all participants (Gaudreau and Nadeau Citation2015). In the context of early childhood education, Markussen-Brown et al. (Citation2017) highlighted in a meta-analysis the fact that the intensity, duration and combination of components of PD programs are positively associated with changes in teaching practices and to a higher quality of educational environments, i.e. structural quality (e.g. classroom layout) and process quality (e.g. interactions with children, including the teacher–student bond). Although video use was not considered a category of format of PD employed per se in this meta-analysis, several studies among those included incorporated videos in their PD programs (Flowers et al. Citation2007; Fukkink and Tavecchio Citation2010; Girolametto, Weitzman, and Greenberg Citation2003, Citation2012; Piasta et al. Citation2012; Powell et al. Citation2010). One can therefore wonder what the precise contribution of this modality was regarding teaching practices and educational environments.

Ahead of these studies, interest in the engineering of PD programs based on in-depth knowledge of real-life work activities has also been on the rise (Durand, Ria, and Veyrunes Citation2010; Flandin, Leblanc, and Muller Citation2015; Hamel et al. Citation2018; Lussi Borer and Muller Citation2014, Citation2016; Ria and Leblanc Citation2011). Until recently, PD activities for teachers took a normative approach, meaning an approach that has participants acquire new knowledge by participating in one-off training workshops in an attempt to bring their practices in line with the most current established norms (Lussi Borer and Muller Citation2016). However, this kind of training does not lead to real change in teachers’ practices and seems to be ineffective in getting participants to pursue enduring PD and foster a high level of reflexivity (Lussi Borer and Muller Citation2016; OECD Citation2014; Ria and Leblanc Citation2011). Reflexivity is an important vector of learning that helps teachers find their own PD path, one that reflects their professional concerns and needs (Darling-Hammond et al. Citation2005; Desimone Citation2009; Lussi Borer and Muller Citation2016; OECD Citation2014). The current scientific literature on the topic suggests that activity-oriented programs incorporating video into the activities as part of a more developmental approach provide one way for practitioners to develop their reflexivity and engage in authentic PD (Flandin, Leblanc, and Muller Citation2015; Gaudin and Chaliès Citation2012; Rosaen et al. Citation2008; Yerrick, Ross, and Molebash Citation2005).

Participating in a PD program that meets the criteria for effectiveness listed above and reflects the needs and concerns of kindergarten teachers may help those teachers refine their practices for supporting children’s oral and written language development in MBP situations and tackle the challenges they face in doing so. It therefore seems that focusing on the real experiences of participants in such a program is a promising avenue for understanding the changes that occur in teaching practices to support oral and written language development in MBP situations.

Theoretical framework

Using the semiological framework of course of action to understand changes in the practices of teachers in the PD program

The semiological framework of course of action proposed by Theureau (Citation2004, Citation2006) can be used to analyze human activity in close detail, including PD activities such as the one in the PD program set up in this study. The activity was designed using an enactive perspective (Maturana and Varela Citation1992). In concrete terms, the ‘enactive’ perspective argues that all living organisms, including human beings, are autonomous. Other premises must be taken into consideration in order to properly understand the semiological framework of course of action: 1) the premise of pre-reflective consciousness, which states that at any given moment during an activity, the actor is aware of the experience of themselves acting (Poizat, Salini, and Durand Citation2013; Theureau Citation2006), and 2) the premise of semiotic mediation, which states that because action is based on the construction of meaning of and by the actor, course of action can be understood as a sequence of signs (Peirce Citation1978). We will therefore specifically focus, from an intrinsic perspective, on how the practices of teachers who participated in the PD program to support oral and written language development in MBP situations changed.

In order to do so, we must identify the meaning given by an actor to their own activity – in this case, the meaning given by teachers to their PD activity – with a verbalization of the actor’s pre-reflective consciousness (Vermersch Citation2006). Verbalization can be obtained under certain favourable conditions, namely if actual evidence of the activity exists (observations, audiovisual recordings, logs, etc.). This evidence must be rich enough to trigger recall, and it must also be close in space and time to the activity (Theureau Citation2006; Vermersch Citation2006). The use of videos as evidence of the actual activities is therefore recommended (Theureau Citation2006).

More concretely, based on the verbalizations of pre-reflective consciousness by the teachers participating in the PD program, the timeline of their PD activity can be reconstructed into a sequence of units of experience. Each unit of experience can be an action, emotion, communication or private or public discourse (that is, a thought that may or may not be spoken out loud), as long as it is meaningful to the actor (Durand, Ria, and Veyrunes Citation2010; Hamel et al. Citation2018; Viau-Guay Citation2010). In order to differentiate the types of units that characterize a given person’s course of action, if the unit is an action or a communication (whether or not it is accompanied by private or public discourse), we will refer to it as an executory sign (in which the person does or says something). If this action or communication is made to seek information or perform an inquiry, we will refer to it as an informatory sign. If the unit is merely public or private discourse, we will refer to it as an interpretive sign (Theureau Citation2004). To go into further detail, each of these units can be described as being a hexadic sign, meaning they comprise five components in addition to the unit of experience. illustrates the hexadic sign and its components. These components reflect the fact that the action does not take place only at instant t, but that it is preceded by the actor’s state of preparation and may eventually result in appropriation, which itself will become the actor’s future state of preparation.

Thus, if we apply the content of and the foregoing to this study, we can first observe that before the PD activity is even conducted, the state of preparation of the teachers participating in the program is characterized by a set of concerns and objectives (S), their expectations about the PD activity (E), and their existing knowledge and the elements of the referential (K) that they can call on in the PD activity. During the activity, certain elements are meaningful to them at a given moment (instant t); these are external or internal cues, that is, the focus on a determined possibility based on an entrenched perceptive, proprioceptive or mnemonic judgment, which will be the basis for the units of experience (U). Lastly, the teacher’s experience is incorporated through an interpretant (I), that is, the learning that results from the experience and that will contribute to the next potential action in their PD activity.

Furthermore, the signs can be grouped into larger structures to represent how they change over time (Gérin-Lajoie Citation2018; Sève et al. Citation2002; Theureau Citation2004). We therefore propose that within a given practice, such as practices to support oral and written language development in MBP situations in kindergarten classroom, PD trajectories (Gérin-Lajoie Citation2018) can be identified. Diagramming development trajectories would make it possible to identify similar set of concerns and objectives for a recurring theme within the time span under consideration and uncover larger concerns and objectives as practices evolve. The different phases of change in practices can also be identified based on the type of signs or groups of signs included in the PD trajectories. An executory phase of a person’s PD trajectory would primarily consist of executory signs, whereas an exploratory phase would consist of informatory or interpretive signs (Sève et al. Citation2002; Theureau Citation2004). In so doing, we will be able to better understand changes in the practices of teachers in the PD program to support oral and written language development in MBP situations.

Given the research problem and the semiological framework of course of action that we have presented, our research questions are:

What PD trajectories emerge within the activity of a teacher participating in a activity-oriented PD program incorporating video on practices to support oral and written language development in MBP situations?

What kind of changes occur in each PD trajectory with respect to practices to support oral and written language development in MBP situations?

What are the cues induced by the program that prompt these changes in the participant’s PD trajectories?

Method

Contextualizing the PD program

The findings in this article are based on an action research project funded under Programme d’actions concertées [the Concerted Actions program] (Fonds de recherche du Québec – Société et culture). The objective of the program was to set up an activity-oriented PD program incorporating video and involving kindergarten teachers in order to promote their support for children’s oral and written language development in MBP situations. The project was carried out in phases from 2016 to 2019. In the first phase (2016–17), the participants took part in four traditional-format training sessions covering basic knowledge (e.g. about language development). In the second phase (2017–18), a laboratory was set up for video analysis of teaching activities. In the laboratory, participants took part in one-on-one self-confrontation interviews about their activity and three half-day group self-confrontation meetings about their activity, i.e. video analysis laboratories. Self-confrontation interviews as proposed by Theureau (Citation2010) aim to trigger pre-reflective consciousness in a given period of time and to obtain its verbalization. It can be distinguished from other interview techniques by the nature of the evidence used, i.e. videos of actual activities, and the premises that are underlying them (Poizat and San Martin Citation2020).

The participant

In this article, we have selected one kindergarten teacher (Julie) to serve as a case study. We chose to focus on a single case study so we could comprehensively document one person’s experience of a program of this kind and what they learned. Our sampling is therefore purposive (Miles and Huberman Citation2003). Julie has 10 years of teaching experience, including five years in kindergarten education. She has a bachelor’s degree in early childhood and elementary education and had not completed any specific training on oral and written language development or MBP prior to participating in the project.

Materials

With this case study, we put in place an observatory of course of action involving self-confrontation using evidence of actual activities in order to have Julie verbalize her pre-reflective consciousness through various guided activities. The materials used to recall the activities during the self-confrontation interviews were primarily videos, but also included notes and summaries with photos of the professional activities in which Julie took part in the laboratory (Flandin, Leblanc, and Muller Citation2015; Theureau Citation2006).

Four self-confrontation interviews were conducted with Julie between October 2017 and April 2018 in order to cover all of the laboratory activities and points between group meetings and self-confrontation meetings. shows the timeline of all the activities in the program.

Each interview lasted for approximately 90 minutes and was recorded for transcription. The basic interview structure was the same for all of the self-confrontation interviews and can be summarized as follows: 1) explain the purpose of the interview, 2) resituate the participant in the activity, 3) view clips and describe and analyze observable actions together. lists the activity evidence used for each interview.

Table 1. Evidence of actual activities used in self-confrontation interviews.

Analysis procedures

In order to answer our research questions, we analyzed the verbalizations obtained in the four self-confrontation interviews. The interviews were first transcribed verbatim, and the participant’s course of action was then reconstructed in chronological order in a table, in the form of a column divided into different time spans. We entered the verbalizations of the teacher’s pre-reflective consciousness associated with the different units of meaningful experience and then identified the components of the hexadic sign for each of those units. Once all the signs were reconstructed (n = 262), we used a coding software program (MaxQDA) to sort the data into emergent categories and identify similar concerns and objectives that are sustained over time for recurring themes, that is, themes revolving around oral and written language development in MBP situations. A total of 100 signs with concerns and objectives of this type, i.e. revolving around the recurring themes, were selected from among all of the signs, leading us to then form larger groups of units of meaningful experience in order to diagram changes to them over time (Sève et al. Citation2002; Theureau Citation2004), that is, represent their trajectories. Throughout the process, a negotiation of meaning was ensured between two project researchers. These trajectories are presented in . Signs with unidentified concerns and objectives or other, more general concerns and objectives not having to do with oral and written language development and/or MBP were not used. Within the 100 selected signs, we distinguished cues (either external or internal) that were program induced from those that were not. In other words, program-induced cues are certain elements or activities from the program (e.g. video analysis laboratories) that were meaningful to Julie at a given moment and that led to a unit of experience.

Table 2. Trajectories of similar concerns and objectives in Julie’s PD activity.

Lastly, we categorized the signs forming these trajectories by type (executory, informatory or interpretive) so we could identify the different phases of change in the PD trajectories within the PD program. To do this, we coded the 100 signs selected in the first step of the data analysis using the three sign types put forth in the theoretical framework: ‘interpretive,’ ‘informatory’ and ‘executory.’ Categorizing the signs made it possible to see whether the participant was more focused on being active (in the sense of taking action or communicating with others), seeking information or interpreting the information provided (talking to herself or discussing with the research team) and what were the program-induced cues that were associated with these changes. The coding of 20% of the signs was validated for inter-rater reliability and the obtained kappa was satisfactory (k = 0.75).

Results

PD trajectories that emerge within the activity of the teacher in the PD program with respect to oral and written language development in MBP situations

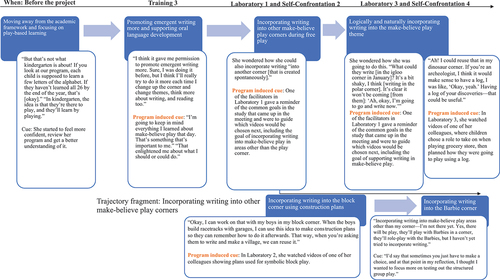

In order to answer our first question, we used the 100 signs selected for the recurring themes to identify similar concerns and objectives sustained over time in Julie’s PD activity. We were able to group these concerns and objectives into larger structures, revealing three trajectories in which Julie’s concerns and objectives in her PD activity changed over time. These trajectories are presented in . For each trajectory, we have provided a timeline of the changes in similar concerns and objectives sustained over time, as well with their associated cues, either program induced or not.

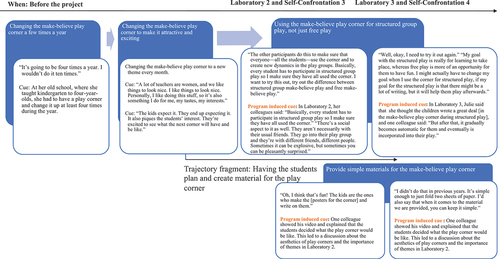

To start, (the Planning and setting up a MBP corner trajectory) shows that prior to the project, Julie’s set of concerns or objectives followed a more technical approach, meaning that the planning and setup of the MBP corner was initially focused on materials and organization over time (e.g. changing the corner four times a year), and progressed to an increasingly pedagogical approach in Laboratories 3 and 4. At the beginning of the project, Julie still tended to take a technical approach that focused on the play corner’s materials and aesthetics. MBP was considered a means to an end rather than an end in itself, but centred the children more (e.g. getting the students excited), until Julie completely reassessed how she should organize MBP in her planning structure (structured group play versus free play) in Laboratory 2. After that, the primary goal of her set of concerns or objectives in planning and organizing the MBP corner was to provide the conditions for her to more effectively intervene in the play, as seen in both the following trajectory and . A new trajectory fragment in also shows that in Laboratory 2, she started to consider having the children plan and organize the MBP corner themselves and shifting away from the aesthetic component that had been her focus up to that point, but did not formally engage with this idea during the course of the program.

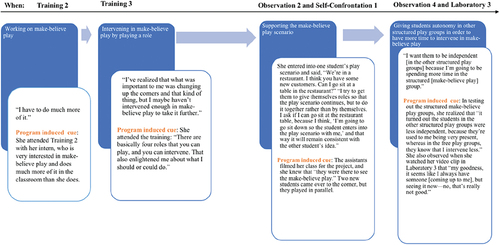

Accordingly, in (the Intervening in MBP trajectory), we can see that Julie’s set of concerns or objectives in intervening in MBP were initially very general. During the second training session, on oral and written language development, which she attended with her intern, who ‘does much more MBP than she does,’ Julie said she wanted to ‘work on MBP’ but did not identify what exactly she wanted to ‘work on.’ However, she clarified her goals during the third training session, which focused on the levels of MBP and how teachers can intervene (e.g. taking on a role), and was even more specific in the first self-confrontation interview (e.g. supporting the play scenario). At this point, MBP was not just a means anymore, but an end in itself, and the level of maturity could be increased in ways such as supporting the play scenario. Finally, in the last laboratory, Julie’s set of concerns or objectives in terms of intervening in MBP was tied to her pedagogical objectives and intersected with her set of concerns or objectives in the previous trajectory. The solution she arrived at, in order to give the children autonomy and give herself opportunities to intervene more in MBP, was to have MBP time in a structured group play setting, which gives her more time to intervene in MBP.

(the Supporting oral and written language development in MBP trajectory) shows that again, Julie’s concerns before the project about learning in MBP were rather general (e.g. learning while playing). At the beginning, she wanted to move away from the academic framework once she started to feel more confident about her interpretation of the program. However, in the third training session, her set of concerns or objectives became more nuanced, as she found she could not only intervene more by playing a role in the MBP (in connection with the previous trajectory), but she could also use MBP as a means to support children’s oral language development and promote emergent writing. As the project progressed, the more she realized that her MBP themes posed something of a challenge (e.g. in terms of how rich the polar corner is for writing). Thus, in Laboratory 3, she adopted one of her colleague’s ideas, which is to have students write in a log, and hoped that this would help her incorporate writing into MBP in a more natural way. We also found that she expressed openness to incorporating writing into an avenue other than the official MBP corner, but did not formally engage with this notion during the program.

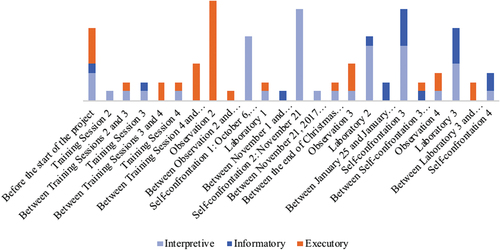

Changes operated in the participant’s PD trajectories

In order to answer our second research question, we identified the activity’s executory, informatory and interpretive phases to illustrate the changes operated in Julie’s PD activity within the program. Among other things, this allowed us to cross reference them with the changes in set of concerns or objectives shown in prior trajectories. shows the changes in phases of Julie’s PD activity according to the activity’s time spans. We note that Julie’s PD activity within the program’s recurrent themes is primarily interpretive (46%). Self-confrontations and laboratories are generally times when Julie ‘interprets’ and, inversely, in-class observations and periods between the program’s activities are generally times when Julie ‘acts’ in her PD activity. These results indicate that the fact that a person ‘does not act’ in a program’s activities (for example, does not speak during laboratories) does not mean that nothing happens in their PD. We also note that before the project started and during its first year, the PD activity is more executory and, beginning with the first self-confrontation, interpretive and informatory activities are increasingly present. We see the first transformation of the nature of the activity at that point. However, it must be noted that self-confrontation 1 focuses primarily on the video footage of Observation 2, which is likely why Observation 2 shows more executory signs than the other time signs.

Further consideration of the periods primarily resulting in changes in Julie’s concerns and objectives, i.e. Laboratories 2 and 3 and their associated self-confrontation, shows that informatory PD activity is much more present than before Laboratory 1. At those times, Julie acts with the aim of seeking information or performing an inquiry that leads her to taking subsequent action. Specifically, we note from the Planning and setting up a MBP corner trajectory () that during Laboratories 2 and 3, Julie continued her intention of incorporating MBP into workshops and not only into free play time, to observe the effects on children’s dynamics and use of writing in play.

In the Supporting oral and written language development in MBP trajectory (), we observe that in Laboratory 3, Julie wonders how to integrate writing in a logical and natural way into the theme of the MBP, after which she retains the idea of the log for the dinosaur-themed MBP corner that she wanted to try out after Self-confrontation 4. Training Session 3, which coincided with the start of the Intervening in MBP trajectory, also led Julie to embark on a search for information and to take multiple steps in that sense in her subsequent PD activity.

Cues induced by the program that prompt changes in the participant’s PD trajectories

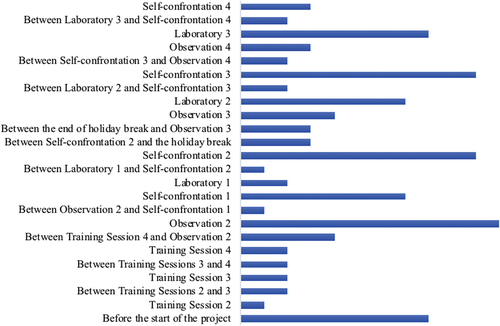

Lastly, in order to answer our third research question, we attempted to identify the cues induced by the program that prompt changes in Julie’s PD trajectories, in connection with the subject of the program’s training. For context, shows how the selected signs were distributed among 24 time spans, tracing the chronology of Julie’s PD activity from ‘before the start of the project’ (including all activities carried out before the first training, in October 2016) to the last ‘self-confrontation’ (April 2018). Note that four of the time spans initially listed extrinsically by the research team are not included in this figure, since no significant unit of experience was associated with them.

It appears that even before the project began, Julie was already interested in oral and written language development in MBP situations in her PD activity. The time spans when the greatest number of signs from these recurring themes were reconstructed were Observation 2 (11%), Self-confrontation 2 (10%) and Self-confrontation 3 (10%). The next greatest numbers were in Laboratory 3 (8%), Laboratory 2 (7%) and Self-confrontation 1 (7%). In light of the previous figures, it appears that the cues induced by the program are primarily associated with the laboratories and self-confrontations, that is, moments when Julie analysed her clips or clips of colleagues and discussed with those colleagues in the program.

In order to better understand how the cues induced by the program allowed Julie’s set of concerns and objectives to change over time, particularly during laboratories and self-confrontations, and thus to document how they shifted the participant’s PD trajectories as they related to practices that support oral and written language development in MBP situations, we indexed the cues induced by the program within the trajectories detailed in the previous sections. We note that the trajectory Intervening in MBP emerged in the second training, and is thus a cue induced by the program. The trajectories Planning and setting up a MBP corner and Supporting oral and written language development in MBP both emerged as cues that did not result from the program. These concerns and objectives were already present for Julie, as also shows. In , however, we see that the cues induced by the program allowed her concerns and objectives, which were initially more general, to change and become more specific. It can be inferred, therefore, that when a pre-existing set of concerns or objectives becomes more specific within one of the trajectories, it is connected to a cue induced by the program. Moreover, it appears that many of the cues that the program induced in Julie’s PD activity resulted primarily from the laboratories and self-confrontations with which they were associated, particularly Laboratories 2 and 3 and self-confrontation 2 and 3. This fits the results presented in . We also noted two trajectory fragments, Planning and creating corner materials for students and Integrating writing into other MBP corners, which both resulted from cues induced by the program. These trajectory fragments indicate that that the potentialities of PD remain present after the program ends.

Discussion

In light of the results presented above, we can draw a number of conclusions regarding our three initial questions: 1) What PD trajectories with respect to practices to support oral and written language development in MBP situations emerge within the activity of a teacher in the program, 2) What kind of changes occur in each PD trajectory, and 3) What are the cues induced by the program that prompt these changes in the participant’s PD trajectories?

Firstly, larger ongoing sets of concerns or objectives structures allowed us to identify three PD trajectories and two trajectory fragments in connection with Julie’s concerns and objectives in her PD activity within the program. These reveal that Julie signed up for the project with pre-existing concerns and objectives about ‘changing up the theme of her MBP corner throughout the year’ and ‘moving away from the academic framework through learning via play.’ These could also have spurred her to participate in the project, as a training topic that seemed to fit in with her prior interests. Beginning with the first training sessions, a new set of concerns or objectives appeared in Julie’s PD activity: ‘working on MBP.’ These trajectories also indicate that at the end of the project, these concerns and objectives had significantly changed and grown more complex; at the end of the project they were ‘incorporate MBP into workshops and not only in free play,’ ‘foster students’ independence in other workshops to carve out more time to intervene in MBP,’ and ‘integrate writing in a logical and natural way into the theme of the MBP.’ What explains these changes? The changes in the nature of the activity and the cues induced by the program in Julie’s activity allow us to better understand the effects of the PD program on her practices.

At several points in the program, various situational elements were significant for Julie because they allowed her to embark upon a process of inquiry and to transition from executory or interpretive activities to an informatory activity, as can be seen in the evolution of the phases of change in Julie’s practices. Thus, our results match those of Blank and de las Alas (Citation2009) and of Desimone (Citation2009) as regards whether a program that responds to and fits well with pre-existing authentic questioning would be more effective in leading a participant to effect changes in their PD. Laboratory 2, Self-confrontation 3 and Laboratory 3 are among the points when important program-induced cues were located and associated with changes in concerns and objectives that grew more complex. More specifically, it appears that videos of colleagues and discussions with those colleagues led Julie to ask herself questions and to begin seeking information, continue to reflect on her questions in self-confrontation interviews and subsequently act in class, driven by her questions. This result therefore indicates that, in order to be effective, PD programs cannot be exclusively collective or individual, but benefit from combining the two approaches. This finding is in line with the meta-analysis by Markussen-Brown et al. (Citation2017), who found that a combination of components of PD programs are associated with better outcomes. The loop between the exploratory and executory phases in her PD trajectories is reminiscent of the concept of inquiry proposed by Dewey (Citation1993) and paraphrased by Lussi Borer and Muller (Citation2016) as collaborative inquiry. Dewey (Citation1993) considers that all living phenomena arise from an organism’s relationship with its environment (Lussi Borer and Muller Citation2016). This relationship, also called a situation, is considered as a reciprocal engagement subject to constant change, which occurs through a continual rhythm of imbalance (indeterminate situations) and restoration of balance (determinate situations). When the balance of an organism–environment relationship is disturbed and the situation becomes confused or contradictory, the organism must problematize the situation and seek balance, which leads specifically to inquiry. However, when multiple individuals work together in a process of transforming situations, Lussi Borer and Muller (Citation2016) suggest that the inquiry becomes collaborative, and provide a model of natural development that can be transposed into training programs. Our results bear out their proposition, since Julie began a process of inquiry in the program without being urged to do so. It appears that it was precisely when the cues induced by the program led her to experience imbalance and to seek to restore the condition of balance that her concerns and objectives and her activity changed.

While Training Session 3 of the program, focusing on basic knowledge concerning MBP, including the roles an instructor could take, led Julie to briefly begin an inquiry process on the possibility of intervening in MBP by taking a role, it appears that the video analysis laboratories and self-confrontation interviews on activity evidence (e.g. videos) more frequently spurred her to such a process. Therefore, the results presented in the next article align with those of many other studies on PD that show the necessity of using programs that focus on active and collaborative learning (Blank and de las Alas Citation2009; Desimone Citation2009; Wood and Stanulis Citation2009) and use evidence such as video in the instructors’ real activities to encourage changes in their practices (Flandin, Leblanc, and Muller Citation2015; Fukkink and Tavecchio Citation2010; Gaudin and Chaliès Citation2012; Lussi Borer and Muller Citation2016; Rosaen et al. Citation2008; Yerrick, Ross, and Molebash Citation2005). Indeed, on their own the program’s basic training sessions, rooted in a more traditional and normative training model, would clearly not have allowed Julie to begin such a fruitful process of inquiry that allowed her concerns and objectives to change over time and her activity to complete several loops between interpretive, informatory and executory phases.

Limitations and areas for research

Notwithstanding the rigour of our analysis, certain limitations must be taken into account when interpreting our results and the conclusions detailed above. First, selection bias is possible, since the selection of the participant was not random in this study. In fact, even before we carried out the analysis to precisely discern the changes in Julie’s concerns and objectives in the program, we had already seen that they had progressed further than those of the other participants who volunteered for the multiple-case study. However, this study shows that Julie’s concerns and objectives had not progressed further than others at the time she signed up for the project, and it has allowed us to better understand why they changed as much as they did within the framework of the program. In light of this new understanding, it appears that a comparative analysis of the changes in study participants’ concerns and objectives and phases of PD trajectories would allow us to learn whether the others have similarly situated themselves in a process of inquiry and to determine the effects of such a process on their own PD activities. Since this case study does not aim to draw generalizable conclusions nor can allow it, the results from a comparative analysis would also give us a better understanding of the role Julie’s individual development profile might have played in the pattern of change observed in her PD trajectories.

A second limitation in the analysis of our study’s results should be pointed out. It appears that the first self-confrontation, which focused primarily on the instructor’s real in-class activity and not on the PD activity in the laboratories, could have introduced instrument bias into our data collection. The evidence used in this first interview, i.e. the video of Observation 2, necessarily led the participant to describe and analyze her inclass activity rather than her PD activity in the program. However, since the speaker revisited several of the program’s activities, particularly the basic training sessions, and since Observation 2 is itself one of the program’s activities, we had no choice but to retain the verbalizations obtained in this interview for our analysis, even if they were less rich than those from other interviews.

Conclusion

We will conclude by laying out some areas for future research in light of our results. First, since it appears that a combined collective and individual approach is beneficial to the effectiveness of PD programs, it would be interesting to more clearly distinguish the respective roles of the individual and collective components, in order to more precisely determine each component’s contributions within the program. Likewise, as using evidence of the real activity seems to be a favorable factor, it would be interesting to specifically observe the value that video adds to the program, since it was not evident from our results whether that made a notable difference to the participant. In fact, many of the ideas that Julie retained from the laboratories could have been shared verbally by her peers. Would that have been equally significant for her? That question remains to be answered. We hypothesize that video may be more significant for individuals who are not already in the process of an inquiry to lead them to identify their own questions and achieve awareness. Lastly, knowing that sustaining these programs in the long term is a significant challenge, it would have been interesting to conduct a more longitudinal follow-up with the participant, for example over six months or a year after the end of the program. By doing so, we would also have been able to confirm whether the changes we observed had truly effected a change in the participant’s practices.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Amélie Desmeules

Amélie Desmeules is an assistant professor at the Faculty of Education at Université Laval (Quebec, Canada) where she is also completing a doctorate degree. She is interested in pre-service and in-service training as well as induction in teaching, particularly in kindergarten and primary education. Her current work focuses on professional development programs and supports offered to new teachers beginning their careers.

Christine Hamel

Christine Hamel, PhD, is a full professor at the Faculty of Education at Université Laval (Quebec, Canada). Her research focuses on the analysis of the activity of the person in its professional practice. She aims to design professional development programs in initial and continuous training that mobilize active participation, proximal support, activity analysis and collaboration to lead to lasting changes in practice.

Anabelle Viau-Guay

Anabelle Viau-Guay, PhD, is a full professor at the Faculty of Education at Université Laval (Quebec, Canada). Her research program focuses on educational practices that contribute to workplace integration and professional development, as well as on learners’ activity, including learning and reflection. She is particularly interested in teacher education.

Caroline Bouchard

Caroline Bouchard, PhD, is a full professor at the Faculty of Education at Université Laval (Quebec, Canada). Her work focuses on child development and the quality of interactions in nature-based early childhood education. She is also interested in the professional development of adults working with young children in that context. She is the director of UMR Petite enfance, grandeur nature, a structuring research entity.

References

- Blank, R. K., and N. de las Alas. 2009. “The Effects of Teacher Professional Development on Gains in Student Achievement.” www.ccsso.org.

- Bodrova, E., and D. Leong. 2012. Les outils de la pensée. Québec City: PUQ.

- Bouchard, C., A. Charron, N. Bigras, L. Lemay, and S. Landry. 2015. “Conclusion. Le jeu en jeu et ses enjeux en contextes éducatifs pendant la petite enfance.” In Actes de colloque: Le jeu en contextes éducatifs pendant la petite enfance. Colloque présenté au 81e congrès de l’ACFAS, edited by C. Bouchard, A. Charron, and N. Bigras. Québec: Livre en ligne du CRIRES. http://lel.crires.ulaval.ca/public/bouchard_charron_bigras_2015.pdf.

- Brougère, G. 2010. “Formes ludiques et formes éducatives.” In Jeu et apprentissage : quelles relations ?, edited by J. Bédard and G. Brougère, 43–62. Sherbrooke: Éditions du CRP.

- Chambers, B., A. C. Cheung, and R. E. Slavin. 2016. “Literacy and Language Outcomes of Comprehensive and Developmental-Constructivist Approaches to Early Childhood Education: A Systematic Review.” Educational Research Review 18: 88–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2016.03.003

- Conseil supérieur de l’éducation (CSÉ). 2012. Mieux accueillir et éduquer les enfants d’âge préscolaire, une triple question d’accès, de qualité et de continuité des services. Québec, QC: Conseil supérieur de l’éducation.

- Darling-Hammond, L., D. J. Holtzman, S. J. Gatlin, and J. V. Heilig. 2005. “Does Teacher Preparation Matter? Evidence About Teacher Certification, Teach for America, and Teacher Effectiveness.” Education Policy Analysis Archives/Archivos Analíticos de Políticas Educativas 13: 42–48. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.v13n42.2005.

- Desimone, L. M. 2009. “Improving Impact Studies of Teachers’ Professional Development: Toward Better Conceptualizations and Measures.” Educational Researcher 38 (3): 181–199. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X08331140.

- Dewey, J. 1993. Logique: La théorie de l’enquête. Paris: PUF.

- Durand, M., L. Ria, and P. Veyrunes. 2010. “Analyse du travail et formation: un programme de recherche empirique et technologique portant sur la signification et l’organisation de l’activité des enseignants.” In Analyser l’activité enseignante : des outils méthodologiques et théoriques pour l’intervention et la formation, edited by F. Yvon and F. Saussez, 17–40. Québec, QC: Presses de l’Université de Laval.

- Flandin, S., S. Leblanc, and A. Muller. 2015. “Vidéoformation « orientée-activité » : quelles utilisations pour quels effets sur les enseignants?” Raisons éducatives 2015 (19): 179–198.

- Flowers, H., L. Girolametto, E. Weitzman, and J. Greenberg. 2007. “Promoting Early Literacy Skills: Effects of In-Service Education for Early Childhood Educators.” Canadian Journal of Speech Language Pathology and Audiology 31 (1): 6–18.

- Fukkink, R. G., and L. W. Tavecchio. 2010. “Effects of Video Interaction Guidance on Early Childhood Teachers.” Teaching and Teacher Education 26 (8): 1652–1659. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.06.016.

- Gaudin, C., and S. Chaliès. 2012. “Video Use in Beginning Teachers’ Professional Development | L’utilisation de la vidéo dans la formation professionnelle des enseignants novices.” Revue Francaise de Pedagogie 178 (1): 115–130.

- Gaudreau, N., and M.-F. Nadeau. 2015. “Enseigner aux élèves présentant des difficultés comportementales : dispositifs pour favoriser le développement des compétences des enseignants.” La nouvelle revue de l’adaptation et de la scolarisation 72 (4): 27–45. https://doi.org/10.3917/nras.072.0027.

- Gérin-Lajoie, S. 2018. Analyse du cours de vie relatif aux pratiques d’enseignement des nouveaux professeurs. Thèse de doctorat, Université Laval, Canada.

- Germeroth, C., E. Bodrova, C. Day-Hess, D. H. Clements, and C. Layzer. 2019. “Play It High, Play It Low: Examining the Reliability and Validity of a New Observation Tool to Measure Children’s Make-Believe Play.” American Journal of Play 11 (2): 183–221.

- Girolametto, L., E. Weitzman, and J. Greenberg. 2003. “Training Day Care Staff to Facilitate Children’s Language.” American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 12 (3): 299–311. https://doi.org/10.1044/1058-0360(2003/076).

- Girolametto, L., E. Weitzman, and J. Greenberg. 2012. “Facilitating Emergent Literacy: Efficacy of a Model That Partners Speech-Language Pathologists and Educators.” American Journal of Speech Language Pathology 21 (1): 47–63. https://doi.org/10.1044/1058-0360(2011/11-0002).

- Hall, A. H., A. Simpson, Y. Guo, and S. Wang. 2015. “Examining the Effects of Preschool Writing Instruction on Emergent Literacy Skills: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Literacy Research and Instruction 54 (2): 115–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388071.2014.991883.

- Hamel, C., A. Viau-Guay, L. Ria, and J. Dion-Routhier. 2018. “Video-Enhanced Training to Support Professional Development in Elementary Science Teaching: A Beginning Teacher’s Experience.” Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education 18 (1): 102–124.

- Hirsh-Pasek, K., R. M. Golinkoff, L. E. Berk, and D. Singer. 2009. A Mandate for Playful Learning in Preschool: Applying the Scientific Evidence. New York: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195382716.001.0001.

- Lillard, A., M. D. Lerner, E. J. Hopkins, R. A. Dore, E. S. Smith, and C. M. Palmquist. 2013. “The Impact of Pretend Play on Children’s Development: A Review of the Evidence.” Psychological Bulletin 139 (1): 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029321.

- Lussi Borer, V., and A. Muller. 2014. “L’enquête collaborative comme démarche de transformation de l’activité d’enseignement : de la formation initiale à la formation continuée.” In Apprendre à enseigner, edited by V. L. Borer and L. Ria, 193–207. Paris: PUF. https://doi.org/10.3917/puf.borer.2016.01.0193.

- Lussi Borer, V., and A. Muller. 2016. “Designing a Collaborative Video Learning Lab to Transform Teachers’ Work Practices.” In Integrating Video into Pre-Service and In-Service Teacher Training, edited by P. G. Rossi and L. Fedeli, 68–89. Hershey, PA: IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-0711-6.ch004

- Marinova, K., and R. Drainville. 2019. “La pression ressentie par les enseignantes à adopter des pratiques scolarisantes pour les apprentissages du langage écrit à l’éducation préscolaire.” Canadian Journal of Education 3 (42): 606–634.

- Markussen-Brown, J., C. B. Juhl, S. B. Piasta, D. Bleses, A. Højen, and L. M. Justice. 2017. “The Effects of Language-And Literacy-Focused Professional Development on Early Educators and Children: A Best-Evidence Meta-Analysis.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 38: 97–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2016.07.002.

- Maturana, H. R., and F. J. Varela. 1992. The Tree of Knowledge: The Biological Roots of Human Understanding, translated by Robert Paolucci, 1998. Boston: Shambhala.

- Miles, M. B., and A. M. Huberman. 2003. Analyse des données qualitatives. Paris: De Boeck Supérieur.

- Miller, E., and J. Almon. 2009. Crisis in the Kindergarten: Why Children Need to Play in School. College Park, MD: Alliance for Childhood.

- Montie, J. E., Z. Xiang, and L. J. Schweinhart. 2006. “Preschool Experience in 10 Countries: Cognitive and Language Performance at Age 7.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 21 (3): 313–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2006.07.007.

- Nicolopoulou, A. 2010. “The Alarming Disappearance of Play from Early Childhood Education.” Human Development 53 (1): 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1159/000268135.

- Nilsson, M., B. Ferholt, and R. Lecusay. 2018. “‘The Playing-Exploring Child’: Reconceptualizing the Relationship Between Play and Learning in Early Childhood Education.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood 19 (3): 231–245. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463949117710800.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2014. “Education at a Glance 2014.” http://www.oecd.org/edu/Education-at-a-Glance-2014.pdf.

- Peirce, C. S. 1978. Écrits sur le signe. Paris: Seuil.

- Pellegrini, A. D., L. Galda, J. Dresden, and S. Cox. 1991. “A Longitudinal Study of the Predictive Relations Among Symbolic Play, Linguistic Verbs, and Early Literacy.” Research in the Teaching of English 25 (2): 219–235.

- Piasta, S. B., L. M. Justice, S. Q. Cabell, A. K. Wiggins, K. P. Turnbull, and S. M. Curenton. 2012. “Impact of Professional Development on Preschool Teachers’ Conversational Responsivity and Children’s Linguistic Productivity and Complexity.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 27 (3): 387–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2012.01.001.

- Poizat, G., D. Salini, and M. Durand. 2013. “Approche énactive de l’activité humaine, simplexité et conception de formations professionnelles.” Education Sciences & Society 4 (1): 97–112.

- Poizat, G., and J. San Martin. 2020. “The Course-Of-Action Research Program: Historical and Conceptual Landmarks.” Activités 17 (2): 1–31. https://doi.org/10.4000/activites.5277.

- Powell, D. R., K. E. Diamond, M. R. Burchinal, and M. J. Koehler. 2010. “Effects of an Early Literacy Professional Development Intervention on Head Start Teachers and Children.” Journal of Educational Psychology 102 (2): 299. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017763.

- Pyle, A., J. Prioletta, and D. Poliszczuk. 2017. “The Play-Literacy Interface in Full-Day Kindergarten Classrooms.” Early Childhood Education Journal 46 (1): 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-017-0852-z.

- Ria, L., and S. Leblanc. 2011. “Conception de la plateforme de formation Néopass@ction à partir d’un observatoire de l’activité des enseignants débutants : enjeux et processus.” @Ctivités 8 (2): 150–172.

- Rosaen, C. L., M. Lundeberg, M. Cooper, A. Fritzen, and M. Terpstra. 2008. “Noticing Noticing: How Does Investigation of Video Records Change How Teachers Reflect on Their Experiences?” Journal of Teacher Education 59 (4): 347–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487108322128.

- Roskos, K., and J. Christie. 2001. “Examining the Play–Literacy Interface: A Critical Review and Future Directions.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 1 (1): 59–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/14687984010011004.

- Sève, C., J. Saury, J. Theureau, and M. Durand. 2002. “La construction de connaissances chez des sportifs de haut niveau lors d’une interaction compétitive.” Le Travail humain 65 (2): 159–190. https://doi.org/10.3917/th.652.0159.

- Stipek, D. 2006. “No Child Left Behind Comes to Preschool.” The Elementary School Journal 106 (5): 455–466. https://doi.org/10.1086/505440.

- Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., and M. H. Bornstein. 1990. “Language, Play, and Attention at One Year.” Infant Behavior and Development 13 (1): 85–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/0163-6383(90)90007-U.

- Theureau, J. 2004. Le cours d’action : méthode élémentaire. Toulouse: Octares Éditions.

- Theureau, J. 2006. Le cours d’action : méthode développée. Toulouse: Octares Éditions.

- Theureau, J. 2010. “Les entretiens d’autoconfrontation et de remise en situation par les traces matérielles et le programme de recherche « cours d’action ».” Revue d’Anthropologie des Connaissances 4 (2): 287–322.

- Trawick-Smith, J. 2012. “Teacher-Child Play Interactions to Achieve Learning Outcomes: Risks and Opportunities.” In Handbook of Early Childhood Education, edited by R. C. Pianta, W. S. Barnett, L. M. Justice, and S. M. Sheridan (ass. eds), 259–277. New York: Guilford Press.

- Vermersch, P. 2006. L’entretien d’explicitation. 4th ed. Issy-les-Moulineaux: ESF.

- Viau-Guay, A. 2010. “Le cadre sémiologique du cours d’action : des outils théoriques et méthodologiques pour l’analyse de l’activité enseignante.” In Analyser l’activité enseignante : des outils méthodologiques et théoriques pour l’intervention et la formation, edited by F. Yvon and F. Saussez, 117–139. Québec City: PUL.

- Wood, A. L., and R. N. Stanulis. 2009. “Quality Teacher Induction: “Fourth-Wave” (1997–2006) Induction Programs.” The New Educator 5 (1): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/1547688X.2009.10399561.

- Wood, E., and C. Chesworth. 2017. ”Play and Pedagogy.” In BERA/TACTYC Academic Review of Early Childhood Education 2003–2017, edited by J. Payler, J. Georgeson, and E. Wood, 49–60. https://www.bera.ac.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2017/05/BERA-TACTYC-Full-Report.pdf

- Yerrick, R., D. Ross, and P. Molebash. 2005. “Too Close for Comfort: Real-Time Science Teaching Reflections via Digital Video Editing.” Journal of Science Teacher Education 16 (4): 351–375. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-005-1105-3.

- Zigler, E. F., D. G. Singer, and S. J. Bishop-Josef. 2004. Children’s Play: The Roots of Reading. Washington, DC, US: ZERO TO THREE/National Center for Infants, Toddlers and Families.