ABSTRACT

Networked approaches to professional learning have been shown to offer broad influence and unique benefits to teachers’ continuing development. However, despite decades of research into the professional learning community (PLC) approach within single schools, there is a paucity of research about network PLCs and a lack of models for effective practice in facilitating networks. The mixed methods study reported in this article involved a case study about a network PLC focused on visual arts in early childhood education (ECE) in New Zealand. The case study explored what elements of a network PLC were effective and found that the nexus between reflective and practical learning improved teacher efficacy. Both individual and collective learning were shown to be influential on pedagogy in the member ECE settings. Leadership practices supported participants to apply new learning in practice with children, and to share learning with colleagues for further effect and embedded change in pedagogy.

Introduction

Teachers are required to engage in ongoing learning throughout their careers, and lack of resourcing in the education sector puts enormous pressure on professional learning approaches when there is very little time or money (Cherrington and Thornton Citation2013). Therefore, professional learning research is critical to discover the most effective ways to improve pedagogy to make best use of teachers’ time and the limited available funding (Kelley Citation2021). Network professional learning communities (PLCs) offer unique strengths to teacher professional learning; for example, the sustained engagement of this approach supports teachers to repeat cycles of reflection and practice and to deepen and crystalise learning (Prenger, Poortman, and Handelzalts Citation2021). The network model draws teachers from multiple education settings, and this brings particular value to the professional learning, such as diversity of ideas, refreshing perspectives and a much wider impact for similar cost, time and effort than in a single organisation PLC (Azorín Citation2020). This article focuses on a network PLC approach, examining supportive conditions for engaging and developing teacher learners through intentional community building, reflection and practice.

Professional learning

Professional learning is a term broadly used to signify the ongoing development of pedagogical skills and knowledge for those in teaching workplaces (Bektaş, Kılınç, and Gümüş Citation2020). Current professional learning perspectives view teachers as active and engaged in constructing knowledge in real situations, instead of being passive recipients of knowledge and skills in order to fill a deficit (Imants and van Veen Citation2010). This constructivist view of learning is reflected in the shift away from ‘professional development’ towards ‘professional learning’ in research (Imants and van Veen Citation2010; Kelley Citation2021), and is also reflected in the term ‘Professional Learning Community’. This view of teacher professional learning highlights certain effective elements and strategies which have been incorporated in PLC approaches: collaboration (Durksen, Klassen, and Daniels Citation2017; Takahashi Citation2011); reflective learning (Lane et al. Citation2014; Pasternak and Rigoni Citation2015); practice-based learning (Imants and van Veen Citation2010); and professional dialogue (Healy Citation2012; Huang, Klein, and Beck Citation2020).

Professional learning research identifies factors central to adult learning: motivation; developing knowledge and skills; and maintaining and applying learning in practice (Cherrington and Thornton Citation2013, Timperley et al. Citation2007; Webster-Wright Citation2009). In a comprehensive review of international literature on ECE teacher professional learning, Siraj et al. (Citation2019) found that professional learning is most effective when it is ongoing and collaborative, incorporating meaningful issues and reflective learning in an authentic context, and when the learners have trust and confidence. Borko (Citation2004) and Webster-Wright (Citation2009) agree that effective professional learning is sustained over time, situated in context, incorporating reflective learning processes and based on co-construction of knowledge in a community of learners. Cherrington and Thornton’s Citation2013 review of research on effective professional learning in the New Zealand (NZ) ECE sector concluded that professional learning for ECE teachers was most effective when contextually relevant and connected in a social community of learners, and involving reflective learning over time. These highlighted attributes of effective professional learning are evident in the PLC approach.

Professional learning communities

‘Professional Learning Community’ is a term with broad meaning that can encompass a wide variety of professional learning practices in different situations (DuFour Citation2007). PLCs have been described using lists of important attributes (see for example, DuFour and Eaker Citation2009; Hord Citation2009) which vary depending on their context and scope. According to Hord (Citation2009), there are five dimensions of a PLC: supportive and shared leadership; shared values and vision; collective learning and application of learning; supportive conditions; and shared practice. Dufour and Eaker (Citation2009) describe six characteristics of PLCs, with noticeable parallels to Hord’s dimensions: shared mission, vision and values; collective inquiry; collaborative teams; action orientation and experimentation; continuous improvement; and results orientation. While Hord pays attention to leadership and an enabling context, Dufour and Eaker focus on the learning processes for members of the PLC. Despite these differences, researchers agree about the value of a group of teachers and others meeting to engage in critical dialogue and reflection, focused on professional learning for the benefit of improved education (DuFour and Eaker Citation2009; Stoll et al. Citation2006; Takahashi Citation2011).

Network PLCs

Much of the PLC literature is concerned with PLCs situated within a single education setting (e.g. Hord Citation2009; Stoll Citation2011). However, international researchers such Azorín et al. (Citation2020), Jackson and Temperley (Citation2007), Prenger, Poortman, and Handelzalts (Citation2021) and Stoll et al. (Citation2006) argue the potential value of network PLCs, where the professional learning can make a difference to the educational experience of a much wider group of children across more settings. A network PLC lacks clear definition in the literature but can be loosely described as teachers from different education settings coming together on a regular basis to talk about teaching and learning and to reflect on practice over time (Jackson and Temperley Citation2007). Fullan (Citation2004) suggests that networks of professional learning across multiple schools may be more effective and sustainable than PLCs within a single organisation:

When best ideas are freely available and cultivated, and when collective identity prospers, we have a change in the very context of the local system. The context or system will change in a way that benefits all schools. And system change is the kind of change that keeps on giving. (9)

Prenger, Poortman, and Handelzalts’ (Citation2017) mixed methods study of 23 network PLCs in the Netherlands school sector identified factors that enabled their development and sustainability, including motivation of individual learners, shared goals and leadership, and a collective focus on student outcomes. The study clarified some of the unique strengths and challenges of the network PLC approach compared to in-school PLCs, for example diversity of ideas and the level of support in each of the connected schools. Prenger et al. suggest that consideration of the structure of a network PLC and its roles and participation are key to successful development.

Issues and tensions in PLCs

Empirical research about the PLC approach has uncovered some unique tensions and challenges, stemming from features which can also be seen as strengths. Critically reflective learning in a group requires a certain level of trust and harmony which may prove hard to achieve (Stoll et al. Citation2006; Thornton and Cherrington Citation2014). The long-term nature of PLCs means that issues such as staff turnover and changes to leadership and policies may occur (Bolam et al. Citation2005). In a broad literature review on PLCs, Bolam et al. (Citation2005) identified several key factors that can inhibit the effectiveness of PLCs: participants’ resistance to change; turnover of members of the PLC; policies at a local and governmental level affecting budget and resourcing; and changes in leadership. In their study on network PLCs, Prenger, Poortman, and Handelzalts (Citation2017) identified limited social support from colleagues as a barrier to the application and sharing of learning from the network PLC back to the school setting, resulting in the suggestion that schools should send multiple delegates. In a study investigating four PLCs, two within single ECE organisations and two in network formation, Thornton and Cherrington (Citation2019) found that key barriers to embedding the PLC included changes in membership and a lack of strong induction processes into the PLC, a lack of clarity around roles and responsibilities, and differing views within a context of low relational trust. Additionally, the network PLCs in their study had unique challenges in terms of needing to establish trust amongst people who did not know each other or work together, and yet they also benefited from being in these new groups because the network context ‘created space for paying deliberate, careful attention to these issues without having to attend to “baggage” that an existing team may carry’ (Thornton and Cherrington Citation2019, 323). Despite these cautions, research about PLCs has demonstrated their potential for transformative professional learning in education settings, and further development of guidance to avoid the issues highlighted above is likely to be worthwhile. Supportive and shared leadership has been shown to be a strong mitigating factor in many of the issues outlined here (Azorín, Harris, and Jones Citation2020; Stoll Citation2011; Thornton and Cherrington Citation2014, Citation2019), and was a focus of the study reported in this article.

Methodology

This qualitative mixed-methods study involved a national survey and a single embedded case study (Yin Citation2017) investigating visual arts teaching in ECE contexts. The methodology was informed by a bricolage theoretical framework (Tobin Citation2018), incorporating four theories with importance for professional learning and visual arts pedagogy: situated cognitive theory (Lave and Wenger Citation1991); social cognitive theory (Bandura Citation1986); socio-cultural theory (Vygotsky Citation1978); and transformative learning theory (Mezirow Citation1978). The survey was designed to capture a picture of sector practices and perceptions about visual arts in the ECE sector; however, the survey findings are not reported in this article because the survey focused on visual arts pedagogy and did not focus on professional learning. The case study was focused on a network PLC, designed to explore effective professional learning strategies to improve visual arts pedagogy.

Case study, as a qualitative method, explores a bounded case through multiple data sources and analysis (Merriam Citation1998). From these data sources, the researcher produces a case description and case themes (Creswell Citation2013). In this study, the bounded case was the phenomenon of the use of networked PLCs to support teacher learning about visual arts in ECE. The case study component in this research can be described as single embedded (Yin Citation2017), because a single PLC was studied through a variety of units of analysis. The embedded case study allows for a complex range of data and can accommodate multiple disciplinary perspectives (Scholz and Tietje Citation2002). A professional learning intervention was planned and implemented, with the intent to provide benefit to the participants and their centre communities, and to explore the potential benefits and limitations of such an approach for developing ECE visual arts teaching practice.

The PLC at the centre of the case study involved a total of nine meetings, four of which included practical art workshops. Meetings always started with reflective dialogue about the participants’ experimentation and practice between PLC meetings, and finished with reflective dialogue about the practical art workshop and what it might mean for teaching and learning in their contexts. Alternating with these were shorter meetings based around reflective discussion about teaching practice. The final meeting included a semi-structured focus group interview, in a similar vein to the previous reflective dialogue we had become used to as a group. The focus group interview included the seven PLC participants and lasted for one hour. The main prompts were through four questions: What did you notice about the group learning processes during the PLC? What specific factors did you notice which supported individual or group learning through the PLC? What challenges or barriers to learning did you notice during the PLC? What did you notice about the facilitator’s role in supporting learning throughout the PLC?

Participants

Seven ECE teachers were the principal participants in the PLC. The PLC project was originally designed to accommodate 8–12 teachers, two or three from each of four ECE settings. The leaders and whole teams at each service were also asked to engage in the research as participants, particularly in the pre- and post-PLC data-gathering phases; therefore, a requirement of volunteer participants in the PLC was that their leaders and teams were also willing to engage in the study. Merriam (Citation1998) states that in qualitative case study research in education, the most appropriate sampling strategy is non-probabilistic because a narrower sample is needed to gain depth of understanding about a few rather than a broad sample representative of the population. She suggests that the most common form of non-probabilistic sampling is purposeful sampling, ‘based on the assumption that the researcher wants to discover, understand, and gain insight and therefore must select a sample from which the most can be learned’ (Merriam Citation1998, 61). In order to learn the most possible from this case study, participants’ willingness to engage in the PLC was an essential requirement along with the other requirements previously outlined, and so the type of sampling used was purposeful.

The sample of participants in the PLC project were recruited from the larger sample of 193 survey participants. At the end of the survey, survey participants had the opportunity to provide contact details if interested in joining the PLC. This resulted in 35 teachers volunteering to be contacted. However, 27 were from outside of the specified geographical region, leaving 8 potential participants. The researcher contacted the participants on the list in order from the first volunteer onwards, in an effort to choose randomly and without bias. Two kindergartens and two early learning centres agreed to being involved in the research, providing a balanced sample of teachers from the two main ECE service types in NZ. Different attributes of the four participating ECE settings are described in , with minimal detail to preserve participant anonymity.

Table 1. Attributes of the four participating ECE settings.

At the beginning of the PLC, 10 teacher participants were engaged in the project from four ECE settings: three from each of two settings, and two from each of the other two settings. Over time, three participants withdrew from the project because they left their workplaces (one for maternity leave and two for other jobs). I attempted to recruit another PLC participant from those services where someone had left, with the help of the remaining participant in those services, but this was not successful. The prospect of joining a PLC group where relationships were already established may have been off-putting. The pre-PLC individual interviews with the teachers who ultimately left the study were removed from the data, but their contributions to group dialogue (team focus groups and PLC reflective dialogue recordings) were retained as it would be difficult to analyse these group transcripts with certain voices deleted from exchanges. This approach to dealing with data from withdrawn participants was agreed to by participants in the information and consent forms. See for an outline of the participation of teachers over time in the PLC project.

Table 2. Participation in PLC over time.

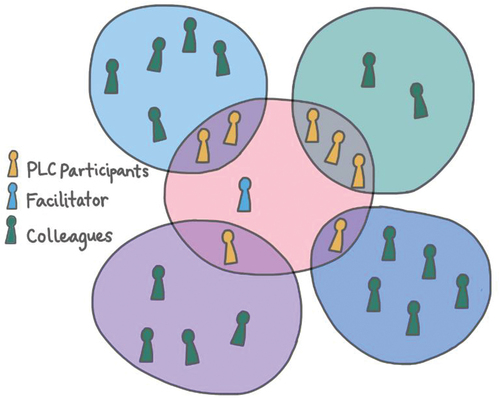

The PLC group included seven teachers from four ECE settings for the majority of the study. The positional leaders, the rest of the teams, and the researcher as PLC facilitator, also participated in interviews and focus groups. illustrates the relationship between the different participants and contexts within the PLC project (units of analysis). The central circle represents the PLC context, and the four shapes surrounding it represent the four ECE settings. The one to three teachers from each ECE service who participated in the PLC are shown here in yellow, their colleagues who did not attend the PLC are shown in green (indicative only, not representing the true number of colleagues in each team), and the PLC facilitator is shown in blue.

Data collection

The pre-PLC and post-PLC data collection included photographs of classroom environments, assessment documentation, and individual and focus-group interviews with the participants, positional leaders and teams. I conducted pre- and post-PLC interviews in order to collect data on participants’ perspectives before and after the intervention. During the PLC, data collection included photographs of art workshops, recorded meeting dialogue, a PLC focus group interview and participants’ reflective journal entries. Drawing on this range of data collection strategies enabled the study to respond to key issues from earlier research. Firstly, Bolam et al. (Citation2005) argue transfer of learning is an under-developed aspect of PLCs, so the data collection was designed to consider what happened in the early childhood settings and what influence the PLC participants had on their teams’ shared pedagogy. Second, Vescio et al.‘s (Citation2008) call for research focused more on the effects of PLCs on teaching practice and outcomes for students; this study included qualitative data collection about the participants’ changes in teaching practice in relation to the professional learning, and analysis of assessment documents before and after the intervention. The photographs and child assessment document analysis have not been included in this article to manage scope, as these were focused more on visual arts pedagogy; this article focuses on interviews, focus groups and reflective journal data about the professional learning approach and outcomes for teachers.

Data analysis

This interpretivist mixed-methods study required multiple types of qualitative data to be thematically analysed, both separately and in combination (Braun et al. Citation2019; Schwandt Citation1994). Interview and focus group transcripts were coded thematically in an iterative coding process, using NVivo software. Reflexive thematic analysis acknowledges and accounts for the inevitable subjectivity of the researcher in thematic analysis, whereby, ‘themes are built, molded, and given meaning at the intersection of data, researcher experience and subjectivity, and research question(s)’ (Braun et al. Citation2019, 854). The data was thematically analysed according to Braun et al.’s (Citation2019) sequence of six phases, which gives structure to an otherwise amorphous method: familiarisation with data; generating codes; constructing themes; revising themes; defining themes; producing the report. Within the context of this article, findings relevant to the network PLC approach and to the individual and collective learning experiences of the participants are presented and discussed below.

Findings

Data from the network PLC at the centre of this case study offers insights about how teachers learn effectively through a network PLC approach. The following sub-sections report findings about how the group became a community, the reflective learning strategies in the PLC and the impact of the practical workshops on teachers’ confidence and practice. The thematic analysis of qualitative data is illustrated by examples of quotes from participant interviews, focus groups and reflective journals.

Becoming a community

The development of the community began before the first PLC meeting, as relationships with the participants were established in the first phone calls, visits and interviews. The participants reported feeling both nervous and excited by the time we met for the first meeting.

As trust developed, participants reported that they felt more confident to participate in the learning activities of the group including the group dialogue and the practical workshops. None of the participants knew anyone except their own team members, so there was a challenge from the outset to build trust within the bounds of a monthly meeting. Participants were surprised by how quickly relational trust was built. Both the opportunity to engage in reflective dialogue and the practical workshops were highlighted by participants as being vulnerable experiences, and the growing trust within the group enabled the members to become more comfortable engaging in new experiences and taking risks such as sharing their ideas and creating art in front of others.

Reflective dialogue and journals

In this network PLC, reflective learning was encouraged and supported in two main ways: reflective group dialogue and individual reflective journals.

The group reflective dialogue was a central element of the professional learning design in the PLC and emerged as a powerful factor in individual and group learning. Dialogue allowed the group to: develop knowledge together with combined knowledge and experiences; contest and refine ideas through discussion and debate; and test theories and raise questions for feedback. Participants valued the diversity of ideas coming from different ECE services.

From the post-PLC interview and focus group data, a set of enabling factors for effective group reflective dialogue were revealed: trust, time, group size and shared practice. An example quote is given after each point to illustrate the way participants talked about these ideas in the interview data:

Trust

The PLC participants reported that the development of relational trust in the group was critical for allowing them to share in group reflective dialogue in authentic and honest ways. The participants felt that the group dialogue became increasingly effective for their professional learning as relationships strengthened. ‘I think as we became more comfortable with each other, the sharing and the confidence to talk about what was happening grew, which was really good.’

Time

The length of time allowed for reflective dialogue at each meeting had an impact on whether everyone felt able to speak, and over the length of the PLC it became clear that it was essential to plan a generous amount of time to enable equitable participation – reflective group discussions ranged from 30 to 80 minutes. Further, the cycle of returning to the dialogue at consistent intervals over many months also supported knowledge building and depth of reflective learning.

I think one thing I’ve enjoyed about the network is having discussions one month and then coming back and doing the feedback on the discussions … one time we were talking about doing papermaking and then I went away and did it, and then we came back and then we talked about it more.

Group size

Participants raised the number of members of the group as an enabling factor for reflective dialogue. The PLC group shifted between 10 and 7 members over its duration, and participants reported that they felt this was the ideal range to allow everyone to participate, while also having enough members to offer the richness of diverse perspectives.

I felt very comfortable, and so I was able to listen and also talk, and not have an insecurity about where I was because the group was too big, the group size I think was good … If it had much bigger than 10, I probably, being how I am, would have retreated a bit more.

Shared practice

The PLC participants emphasised the value of talking about real teaching practice, sharing their own experiences, and hearing about others’ experiences in real ECE contexts. Participants reported that the professional learning from the group reflective dialogue was meaningful to them and trustworthy because it was located within genuine teaching contexts.

I think it was really good that we all came from quite different centres … that was really important, because we all have a different lens, or came with different experiences and different skills, and I think we had an opportunity to see that.

The PLC participants were encouraged to keep an online reflective journal folder throughout the PLC, primarily for written reflections and also including artefacts such as assessment documentation, photographs and other professional teaching materials. According to the participants, the process of reflective journal writing helped individual learners to establish and maintain threads of connection between ideas and between different contexts, thereby facilitating the construction of knowledge. The participants’ reflective journal data show regular examples of questioning of assumptions, analysis and criticality, research, risk-taking and self-assessment.

Reflective learning was a critical factor in supporting participants to reconsider their assumptions and biases, and allowed the group in turn to act as disruptors for each other; one participant explained, ‘you might think one thing, and you talk to someone else, and they say something different, and actually, there is another way of looking at it’. Between meetings, the readings sent to participants worked to remind and further provoke thinking.

Practical workshops

The value of the practical workshops in this case can be viewed from two different angles: teachers benefit from hands-on experiences with art materials and processes to increase confidence for teaching; and practical experiences and outside experts can strengthen reflective learning processes in the PLC context. Participants reported that group relationships were strengthened through the shared experience of the workshops, reflecting on the way conversation flowed while hands were busy making and what this might mean for children engaging in group art-making in an ECE environment. One participant said:

We got some really good tips for modelling art, and how to actually do it as adult learners, which then transferred into what we could do with children. I think having a toolbox of skills also means you can take that experience back to working with children. So, if you wanted to do pencil – we’d already had a turn, so then we can go back and actually feel okay using it with the children. I think vocabulary, as well; I’m thinking back to the clay. There was a lot of vocabulary in that, that I immediately came back and worked with the children with it.

Participants described the direct impact from the practical experience on their teaching practice with children, as they developed skills, knowledge and language for use during visual arts teaching interactions. Further, participants reported that the artists as outside experts provided them with different perspectives on visual arts learning, challenging assumptions common in the ECE sector.

Individual and group learning

The seven individual participants each experienced a different learning journey through the PLC, influenced by widely varying experiences, lives, presumptions and levels of confidence in visual arts. The findings of this study suggest that individuals can be motivated to engage in professional learning by a personal strength or interest, or they can conversely be motivated by a self-perceived area of weakness in teaching practice. The PLC participants each took responsibility for their own learning through engaging with various readings, seeking visual arts experiences between meetings and addressing real teaching issues in their own practice. For the participants in this PLC, a variety of professional learning strategies and structures fostered their individual professional learning. One participant summarised the various benefits of the PLC for the participants’ individual learning:

You ended up with a huge amount of input, for not a lot of time. Yeah, so you had your own learning in the centre, your own reflections, the learning that you got from other people that they were doing in their centre, the learning you got from [the facilitator] and the learning you got from the visiting artists, all in one.

In the early stages, the exercises to establish shared goals and direction of learning were valuable, not only to make the learning more focused but also in terms of developing trust and collegiality. The prioritising of plenty of time for reflective dialogue at every meeting meant that group members were regularly sharing excitement and interest in new ideas, and then trying some of the same ideas in practice. This would then lead to more complex analysis and knowledge building at the following meeting because there were often several people with similar experiences but in different contexts, which added rigour to the PLC group’s research into effective visual arts practices. The group members developed a level of interdependence where they would share resources and techniques, and through such support they developed collective confidence and understanding.

Discussion

This discussion explores how teachers in this study learned individually and collectively in a professional learning group over an extended period, within the context of previous research and literature, and suggests that there are some unique strengths in a network PLC approach.

The network PLC

The effective and challenging nature of the network PLC model and how this relates to PLC and professional learning literature more broadly will now be considered. A point of difference in this PLC was the pre-determined focus on visual arts in ECE. As explained in the literature review, the focus across most PLC research has been on the process and relationships within the PLC, whereas this study was designed with a particular interest in improving visual arts teaching practice. This may have acted as somewhat of a fast track to the ‘Shared vision’ which has been identified by some of PLC researchers as a vital element of effective and sustainable PLCs (for example, Bolam et al. Citation2005; Hipp et al. Citation2008; Hord Citation2009). The trajectory of this network PLC over a relatively short period compared to other studies, many occurring over years (for example, Hipp et al. Citation2008; Prenger, Poortman, and Handelzalts Citation2021), indicates that starting with a clearly defined focus on an aspect of teaching and learning has the potential to support PLC effectiveness.

Teachers work and learn within the pedagogical culture and patterns of behaviour embedded in their workplace (Imants and van Veen Citation2010). Interview, reflective journal and learning story data all indicate that the network PLC model has the potential to have an ongoing and meaningful effect on teachers’ practice and on team pedagogy. Additionally, the impact of this network PLC can be presumed to have been experienced by far more children than a single-organisation PLC model would have, supporting Fullan’s (Citation2004) assertion that learning communities across a network group are likely to be more efficient at improving the educational experience of more children and more likely to contribute to system change.

Relational trust

The findings from this study support previous research emphasising the importance of relational trust for effective learning in PLCs within organisations (Hord Citation2009; Stoll Citation2011; Thornton and Cherrington Citation2019), and demonstrate that the development of relational trust is different but also important in the network PLC model. Community-building in a network PLC is not necessarily a process of striving for agreement or even harmony (Prenger, Poortman, and Handelzalts Citation2021). According to interviews and reflections, the PLC participants highly valued the diversity of opinions and experiences in the group and appreciated the challenges and disruption to thinking even when they remained in disagreement. Trust and enjoyment of each other developed at the same time as acknowledgement of the differences between them, rather than by seeking to be homogenous or to think the same. The stimulation of different perspectives turned out to be a catalyst for professional learning, and the participants were all cognisant of the benefits for their own learning in hearing differing opinions and philosophies of practice. This suggests that the network PLC model has the potential to counter a common tendency in ECE teams ‘to value harmony over critique and to avoid conflict and difficult conversations’ (Thornton and Wansbrough Citation2012, 53). The network PLC allowed participants to engage in debate and professional dialogue without the pressure to ultimately come to an agreed shared pedagogy, removing some of the risk. As Wenger et al. (Citation2002, 10) suggest, ‘controversy is part of what makes a community vital, effective, and productive’. The findings from this study indicate that the network PLC approach offers teachers the empowerment, challenge and diversity of ideas needed to question existing practice, and to make way for new evidence-based ways of teaching.

Reflective and practical learning

In the post-PLC interviews and reflections, the PLC participants were clear that the interaction between reflective and practical learning was a major factor in shifting their thinking and in making changes to teaching practice. These findings support the idea that reflective learning is a critical aspect of the PLC learning process to achieve professional growth in teachers (Hipp and Huffman Citation2010; Prenger, Poortman, and Handelzalts Citation2017; Thornton and Cherrington Citation2019). Through the network PLC journey, teachers reported that reflective learning challenged their prior thinking about visual arts and visual arts pedagogy. The combination of reflection and practice then supported the construction of new schemata about visual arts in general and in teaching and learning. The process of changing thinking leading to changes in behaviour or practice can be viewed through a transformative learning theoretical view. Mezirow (Citation1997) proposed that adults who experienced significant disruption of prior thinking would then usually change their behaviour according to their new perspective. Mezirow highlighted critical reflection and experiential learning as central to this process of learning, indicating relevance to the network PLC design.

The findings regarding group reflective dialogue in the network PLC are in line with Huang et al.’s (Citation2020, 4) Vygotskian socio-cultural view of professional dialogue, suggesting that ‘professional dialogue may play a pivotal role in enhancing teachers’ instructional practices and in transforming professional learning through the (co-)construction and (re)negotiation of meaning’. Group reflective dialogue appears to be a central force in the network PLC approach, and worthy of considerable planning and attention if professional growth and improved teaching practice are desired.

The case study data indicated that written reflective journals can enhance reflective learning in a network PLC. In this PLC project, the reflective journals provided participants with a tangible record of reflection which they were able to return to over time. This reflection can act as a catalyst for shifting thinking, as by its nature a document is easier to re-consider than dialogue, which is fleeting. These findings suggest that reflective journals are an effective way for ECE teachers to make connections between what is discussed in professional learning and their own work environment and practices, aligning with previous research on primary and secondary school teachers’ reflective writing (Lane et al. Citation2014; Pasternak and Rigoni Citation2015). In these ways, the design of and support for teachers to engage deeply in their reflective journals in this PLC answer Webster-Wright’s (Citation2009) call to turn workplace experience into professional learning through critical reflection.

The practical art workshops in this study were shown to be a major factor in progressing teachers’ professional learning about visual arts, according to participant interviews and reflections. The inclusion of practical workshops and outside experts is not commonly discussed in empirical research about PLCs but has been suggested as a useful component, for example, in the research by Prenger, Poortman, and Handelzalts (Citation2017) on influential factors in network PLCs. The experiences of this group of teachers suggest that practical workshops are a valuable inclusion in company with reflective learning modes such as reflective dialogue and reflective writing, and further research is needed to explore the potential of this approach in a network PLC model.

Professional learning dynamics

The findings of this study signal the importance of considering individual and group learning dynamics in a network PLC. Here, individual reflection appeared to be enhanced by social connection, and group learning was ameliorated by individual successes. This indicates that it is worthwhile to address effective conditions for both individual and group learning when planning and facilitating a network PLC. While the community structure is central to any study on a PLC approach (Stoll Citation2011), it is crucial to also consider the teachers as individual learners within the PLC (Hord Citation2009), as they will individually carry the new ideas and improved practices into future teaching and learning. The outcomes and effects of this network PLC project suggest that a purposeful collection of professionals can create synergy, where the collective learning equals more than the sum of individual learners. The participants were consistent and repetitive in their assertion that they had learned more because of the dynamic nature of the group and the richly diverse perspectives. The participants also pointed to the collaborative way of learning as motivating them as individual learners, in accordance with Durksen et al.’s (Citation2017) framework of motivation and professional learning, where engagement, collaboration and reciprocal relationships lead to teacher professional growth. The findings from this study suggest that there are certain strategies which encourage and enrich the group learning dynamic in a network PLC. Takahashi (Citation2011) argues that teachers can build self-efficacy collectively, and that attention should be given to communities of practice as a way to increase self-efficacy amongst teachers to improve teaching practice, overlaying a social constructivist view of the collective with a social cognitive view of individual self-efficacy. The experiences and outcomes of this network PLC support such an argument.

The whole group engaged with these different elements, but not always together. Some authors have highlighted the need to attend to individual as well as group learning in PLCs (Bolam et al. Citation2005; Hord Citation2009); however, there appears to have been very little analysis of individual learning processes in PLC research where collaboration and community learning have rightly demanded attention. The data about the seven participants’ learning journeys in this study have demonstrated that individuals within the PLC experienced unique strengths and challenges, and that the conditions to support individual learning are worthy of attention in PLC design alongside conditions for collaborative learning.

Limitations of the study

The PLC project was a single case study, not run as a comparison or including a control group. However, the intentional study of a single embedded case (Yin Citation2017) allowed time to incorporate rich data on each participant, and the multiple data sources provided strength to the findings.

Those who volunteered for the PLC were required to have the support of their positional leader because they needed to give permission and also participate. Therefore, the supportive leadership in these cases is not indicative of general trends in the sector.

Those who volunteered for the PLC can be presumed as more likely to already have some motivation and interest in developing visual arts education, whereas it would probably be more challenging and less successful to develop individuals who were less engaged.

The length of the PLC was limited by the time available for the research.

Conclusion

The findings from this study demonstrate the value of network PLCs for teacher professional learning, where opportunities to share practice and reflection with colleagues from other settings can offer new insights and ideas. Teacher professional learning has been shown through this study to be effective when it includes the time to build relational trust, a shared pedagogical focus, opportunities for collaboration and dialogue, and modes of reflective as well as practical learning. The network PLC model developed in this study offers these strengths. A key finding from this research was the value of an established curriculum focus at the outset – in this case visual arts pedagogy – to develop shared professional expertise and experience through collaborative professional learning. This research also raises the importance of professional learning happening within teams and within ECE settings, including practical and reflective work-based learning, which could be incorporated into professional learning models. There is an opportunity for future research to develop effective and replicable structures or models for network PLCs, including experimentation of the effectiveness of this model for different curriculum or focus areas.

This research has considered the potential for network PLCs to influence a number of education settings and therefore reach a wider range of children with improved teaching practice compared to PLCs operating within a single organisation. In this case, the PLC participants took learning from the PLC and applied it in practice with children, and disseminated their learning with their centre colleagues to influence shared pedagogy for visual arts. The outcomes for the teachers in this study support Prenger, Poortman, and Handelzalts’ (Citation2021) argument that professional learning networks may have certain advantages over PLCs in single schools, such as opportunities to reflect on practice in relation to the practices happening in other settings and the wider range of expertise and strengths existing in a more diverse group. Although the research involved a single collective case study, overall, this study has highlighted the network PLC as a powerful mode of professional learning that can be adopted and adapted to suit different contexts by teachers and leaders, professional learning facilitators and educational researchers.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Rachel Denee

Dr Rachel Denee has undertaken research in leadership, professional learning, early childhood pedagogy and visual arts education. Rachel is a Lecturer in Early Childhood Education at Victoria University of Wellington. She also has a role as pedagogical leader at Daisies Early Education and Care Centre, Wellington, New Zealand, and as an international educational consultant.

References

- Azorín, C. 2020. “Leading Networks.” School Leadership & Management 40 (2–3): 105–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2020.1745396.

- Azorín, C., A. Harris, and M. Jones. 2020. “Taking a Distributed Perspective on Leading Professional Learning Networks.” School Leadership & Management 40 (2–3): 111–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2019.1647418.

- Bandura, A. 1986. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Bektaş, F., A. Ç. Kılınç, and S. Gümüş. 2020. “The Effects of Distributed Leadership on Teacher Professional Learning: Mediating Roles of Teacher Trust in Principal and Teacher Motivation.” Educational Studies 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2020.1793301.

- Bolam, R., A. McMahon, L. Stoll, S. Thomas, M. Wallace, A. Greenwood, K. Hawkey, M. Ingram, A. Atkinson, and M. Smith. 2005. Creating and Sustaining Effective Professional Learning Communities. Bristol: University of Bristol.

- Borko, H. 2004. “Professional Development and Teacher Learning: Mapping the Terrain.” Educational Researcher 33 (8): 3–15. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X033008003.

- Braun, V.V. Clarke, N. Hayfield, and G. Terry. 2019. “Thematic Analysis.” In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences, edited by P. Liamputtong, 843–860. Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- Cherrington, S., and K. Thornton. 2013. “Continuing Professional Development in Early Childhood Education in New Zealand.” Early Years 33 (2): 119–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2013.763770.

- Creswell, J. 2013. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing Among Five Approaches. London: Sage.

- DuFour, R. 2007. “Professional Learning Communities: A Bandwagon, an Idea Worth Considering, or Our Best Hope for High Levels of Learning?” Middle School Journal 39 (1): 4–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/00940771.2007.11461607.

- DuFour, R., and R. Eaker. 2009. Professional Learning Communities at Work: Best Practices for Enhancing Students Achievement. Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree Press.

- Durksen, T. L., R. M. Klassen, and L. M. Daniels. 2017. “Motivation and Collaboration: The Keys to a Developmental Framework for Teachers’ Professional Learning.” Teaching & Teacher Education 67:53–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.05.011.

- Fullan, M. 2004. Systems Thinkers in Action: Moving Beyond the Standards Plateau: Teachers Transforming Teaching. Nottingham, UK: Department for Education and Skills.

- Healy, C. 2012. “Overlapping Realities: Exploring How the Culture and Management of an Early Childhood Education Centre Provides Teachers with Opportunities for Professional Dialogue.” Master of Education Master’s thesis, Victoria University of Wellington.

- Hipp, K., and J. Huffman. 2010. “Demystifying the Concept of Professional Learning Communities.” In Demystifying Professional Learning Communities: School Leadership at Its Best, edited by K. Hipp and J. Huffman, 11–21. Plymouth: Rowman & Littlefield Education.

- Hipp, K., J. Huffman, A. Pankake, and D. Olivier. 2008. “Sustaining Professional Learning Communities: Case Studies.” Journal of Educational Change 9 (2): 173–195. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-007-9060-8.

- Hord, S. 2009. “Professional Learning Communities.” Journal of Staff Development 30 (1): 40–43.

- Huang, A., M. Klein, and A. Beck. 2020. “An Exploration of Teacher Learning Through Reflection from a Sociocultural and Dialogical Perspective: Professional Dialogue or Professional Monologue?” Professional Development in Education 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2020.1787192.

- Imants, J., and K. van Veen. 2010. “Teacher Learning as Workplace Learning.” International Encyclopedia of Education 7:569–574. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-044894-7.00657-6.

- Jackson, D., and J. Temperley. 2007. “From Professional Learning Community to Networked Learning Community.” In Professional Learning Communities: Divergence, Depth and Dilemmas, edited by L. Stoll and K. Louis, 45–62. Maidenhead, UK: Open University Press.

- Kelley, A. 2021. “Improving Teacher Professional Learning: Inquiry Cycles and the Whole Teacher. In Supporting Early Career Teachers with Research-Based Practices, edited by L. Wellner, and K. Pierce-Friedman, 147–166. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Lane, R., H. McMaster, J. Adnum, and M. Cavanagh. 2014. “Quality Reflective Practice in Teacher Education: A Journey Towards Shared Understanding.” Reflective Practice 15 (4): 481–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2014.900022.

- Lave, J., and E. Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge university press.

- Merriam, S. 1998. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Mezirow, J. 1978. “Perspective Transformation.” Adult Education 28 (2): 100–110.

- Mezirow, J. 1997. “Transformative Learning: Theory to Practice.” New Directions for Adult & Continuing Education 74:5–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.7401.

- Pasternak, D. L., and K. K. Rigoni. 2015. “Teaching Reflective Writing: Thoughts on Developing a Reflective Writing Framework to Support Teacher Candidates.” Teaching/Writing: The Journal of Writing Teacher Education 4 (1): 5.

- Prenger, R., C. L. Poortman, and A. Handelzalts. 2017. “Factors Influencing Teachers’ Professional Development in Networked Professional Learning Communities.” Teaching & Teacher Education 68:77–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.08.014.

- Prenger, R., C. L. Poortman, and A. Handelzalts. 2021. “Professional Learning Networks: From Teacher Learning to School Improvement?” Journal of Educational Change 22:13–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-020-09383-2.

- Scholz, R. W., and O. Tietje. 2002. Embedded Case Study Methods: Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Knowledge. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Schwandt, T. A. 1994. “Constructivist, Interpretivist Approaches to Human Inquiry.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. Denzin and Y. Lincoln, 118–137. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Siraj, I., D. Kingston, and C. Neilsen-Hewett. 2019. “The Role of Professional Development in Improving Quality and Supporting Child Outcomes in Early Education and Care.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Research in Early Childhood Education 13 (2): 49–68.

- Stoll, L. 2011. “Leading Professional Learning Communities.” In Leadership and Learning, edited by J. Roberston and H. Timperley, 103–117. Los Angeles: Sage.

- Stoll, L., R. Bolam, A. McMahon, M. Wallace, and S. Thomas. 2006. “Professional Learning Communities: A Review of the Literature.” Journal of Educational Change 7 (4): 221–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-006-0001-8.

- Takahashi, S. 2011. “Co-Constructing Efficacy: A “Communities of Practice” Perspective on Teachers’ Efficacy Beliefs.” Teaching & Teacher Education 27 (4): 732–741. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.12.002.

- Thornton, K., and S. Cherrington. 2014. “Leadership in Professional Learning Communities.” Australasian Journal of Early Childhood 39 (3): 94. https://doi.org/10.1177/183693911403900312.

- Thornton, K., and S. Cherrington. 2019. “Professional Learning Communities in Early Childhood Education: A Vehicle for Professional Growth.” Professional Development in Education 45 (3): 418–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2018.1529609.

- Thornton, K., and D. Wansbrough. 2012. “Professional Learning Communities in Early Childhood Education.” Journal of Educational Leadership, Policy and Practice 27 (2): 51.

- Timperley, H., A. Wilson, H. Barrar, and I. Fung. 2007. Teacher Professional Learning and Development: Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration. Wellington: Ministry of Education.

- Tobin, K. 2018. “Methodological Bricolage.” In Eventful Learning: Learner Emotions, edited by S. M. Ritchie and K. Tobin, 31–55. Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill NV.

- Vescio, V., D. Ross, and A. Adams. 2008. “A Review of Research on the Impact of Professional Learning Communities on Teaching Practice and Student Learning.” Teaching & Teacher Education 24 (1): 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2007.01.004.

- Vygotsky, L. 1978. “Interaction Between Learning and Development.” Readings on the Development of Children 23 (3): 34–41.

- Webster-Wright, A. 2009. “Reframing Professional Development Through Understanding Authentic Professional Learning.” Review of Educational Research 79 (2): 702–739. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308330970.

- Wenger, E., R. A. McDermott, and W. Snyder. 2002. Cultivating Communities of Practice: A Guide to Managing Knowledge. Boston, MA: Harvard Business Press.

- Yin, R. K. 2017. Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods. London: SAGE Publishing.