ABSTRACT

This article describes how some Swedish compulsory schools work to achieve collective development of practices in mathematics and science. The overall aim is to increase knowledge about factors influencing progression to professional learning in different school contexts. Data were collected through four case studies by interviews with teacher teams and principals and were analysed in a meta-perspective by using the components of the Collaborative Action Research model. The findings showed that the schools had reached different phases concerning progression to professional learning. Changes aiming to improve teaching and learning are context-bound. Therefore the authors suggest some crucial questions to support professional learning in the prevailing school culture.

Introduction

Teacher professional development (PD) refers to the growth and development of teacher knowledge leading to changes in practices and positive learning outcome for students (Avalos Citation2011; Opfer and Pedder Citation2011). Many factors are found to influence the PD of teachers. The review by Hauge and Wan (Citation2019) shows that an environment dominated by trust is vital in learning communities and highlights the importance of teachers having influence on initiation and planning of their professional activities. The findings also show that external support has an impact on teacher PD. Research indicates that PD must be contextualized in teachers’ practices if changes are to take place (Darling-Hammond and Richardson Citation2009; Olsson Citation2019; Stoll et al. Citation2006) and when opportunities for collective development are created it can support teacher PD and improve their practices (Darling-Hammond and Richardson Citation2009; Little Citation2012; Postholm Citation2012).

There is an increasing amount of research stressing the role teachers play in changing their knowledge bases and practices with the aim of promoting student achievement (Bleicher Citation2014; Borko, Jacobs, and Koellner Citation2010; Stoll et al. Citation2006; Timperley Citation2011; Vescio, Ross, and Adams Citation2008). It is concluded that teacher communities are most stimulating and effective when they focus on student learning (Bolam et al. Citation2005; Vescio, Ross, and Adams Citation2008). The research field on teacher PD is moving towards the notion of teacher professional learning (PL). Timperley (Citation2011, 5) states that: ‘One of the critical differences between the two terms is that professional learning requires teachers to be seriously engaged in their learning whereas professional development is often seen as merely participation’, and the crucial goal of teacher PL is to promote changes in teaching practices with the intention to increase student achievement.

A recent study in a Swedish school context has shown that teachers in compulsory and upper secondary schools generally do not perceive they have enough organized opportunities to work on systematic planning and revisions in relation to pupil learning (Nordgren et al. Citation2019; Olsson Citation2019). Data were collected through a questionnaire surveying almost 2300 teachers. The findings indicate that when there is organized collaboration, teachers are more positive about their opportunities to develop their lessons and about their working environment. Opfer and Pedder (Citation2011) address the need for formulating explanations for why teacher learning may or may not occur as a result of development activities. In the light of these findings, we have studied teachers’ and principals’ views on how to organize and develop teaching and learning in some Swedish schools that apply a collective way of working.

Aim and research questions

The aim of this study is to describe how some Swedish schools work to achieve collective development of practices in mathematics and science, and to analyse and discuss the expressed benefits of and barriers to collective work. The overall aim is to increase knowledge about factors influencing collective professional development in different school contexts. The study was guided by the following questions:

How do teacher teams and principals work collectively to develop teaching and learning in science and mathematics?

Which benefits of and barriers to collective work do teachers and principals perceive?

Theoretical framework

Teacher collaboration within schools includes different arrangements and levels of intensity. Gräsel, Fußangel, and Pröbstel (Citation2006) have established a collaboration model described by Muckenthaler et al. (Citation2020) that differentiates between three levels of collaboration, based on their intensities as well as dependency and independency: Level 1: Exchanging information and material with colleagues; Level 2: Sharing work with colleagues; and Level 3: Co-construction. The last form of collaboration is more intensive and describes the development of common knowledge and solutions to problems.

Through collaboration a collective PD has the potential to occur. The factors found to impact teachers’ collective PD in schools are described in a review study by Hauge and Wan (Citation2019) and include three main categories of factors (Structural and cultural matters, Design and influence, and Teachers as agents), referring to the ways teachers’ collective development and learning take place in schools. It is found that time and resources are important, but not decisive for professional development to occur. Louws et al. (Citation2017) highlight that cultural matters and leadership are more important than structural matters (time and resources) in relation to PD. This agrees with the findings in an Irish study (King Citation2016) which shows that time must be allocated for collaboration to support PD and changes in teaching practice. But time itself is not enough; the teachers must be given support in how to use this meeting time in a focused and efficient way. A Finnish survey study (Soini, Pietarinen, and Pyhältö Citation2016) highlights the importance of investing time in creating a collaborative learning culture. It is crucial that teachers perceive themselves as professional agents in their own learning process (Andresen Citation2015; Kellner and Attorps Citation2015; King Citation2016; Soini, Pietarinen, and Pyhältö Citation2016; Timperley Citation2011).

The engagement of school leaders is important for teacher PD, and King (Citation2016) states that trust is a key factor in this process. Research emphasizes that openness to expressing disagreements is important for creating a constructive dialogue and for learning to occur in teacher collaboration (Dobie and Anderson Citation2015; King and Stevenson Citation2017). If the principal clearly communicates enthusiasm to the teachers and to others in the leadership team, it will contribute positively to the trust between teachers and leadership team (Takahashi and McDougal Citation2016). Also, the trust the principal has in the teachers is positively linked to the trust teachers have between themselves (Hallam et al. Citation2015), and trust between teachers is a strong supportive resource that stimulates reflective dialogues and allows critical statements (Andresen Citation2015; Hallam et al. Citation2015). Furthermore, teachers’ reflections and discussions become more exploratory in a context dominated by trust (Andresen Citation2015).

New development ideas must have a strong focus, be highly structured and applicable and be surrounded with a clear framework in order to be lasting and become a part of the school culture (King Citation2016). One explanation why intervention projects like Learning Studies (LS) are often unsuccessful outside Japan seems to be that the teachers have not thoroughly studied the LS method (Takahashi and McDougal Citation2016). This corresponds with findings by Owen (Citation2015) which show the importance of teachers being involved in both designing and planning of interventions.

Visnovska and Cobb (Citation2015) have shown that although teachers are participating in development projects, it can be difficult to understand student thinking and learning. Their suggestion is to consider teacher practices on two levels. The first level, online activities, refers to the actions in the classroom. The second, offline level, refers to activities outside the classroom – for example, collective or individual planning of lessons and assessments. The researchers found that the teachers lacked efficient methods for discussing student prior knowledge and learning, and this tallies with findings by Wilson et al. (Citation2017). Using scaffolding support, such as a theoretical framework for collective reflection, is found to improve teaching and pupil learning (Attorps and Kellner Citation2017; Takahashi and McDougal Citation2016). Many studies also stress the importance of external support through intervention studies to scaffold teacher PD and changes in practice, where researchers induce processes led and owned by the teachers (Engeström and Sannino Citation2010; González, Deal, and Skultety Citation2016; Kellner and Attorps Citation2020; Takahashi and McDougal Citation2016).

Research highlights the benefits of collaboration in professional learning communities (PLCs). The concept of a PLC rests on the idea of improving student learning by improving teaching practice (Vescio, Ross, and Adams Citation2008). In these communities, teachers collaborate towards continued improvement in meeting student needs through a common curriculum-focused vision. In that sense the collaboration in PLC can be positioned on the third level (Co-construction) in the collaboration model by Gräsel, Fußangel, and Pröbstel (Citation2006). Research has shown that well-developed PLCs have positive impacts on both teaching practices and student achievements (Attorps and Kellner Citation2017; Darling–Hammond and McLaughlin Citation2011; Fishman et al. Citation2003; Hauge and Wan Citation2019; Lomos, Hofman, and Bosker Citation2011a, Citation2011b; Olsson Citation2019; Timperley Citation2011; Vescio, Ross, and Adams Citation2008). In a Swedish context, Olsson (Citation2019) has identified different types of partially overlapping measures that, in combination, could contribute to the development of PLCs. These include adapting to each specific school context, promoting university–school collaboration and establishing a supportive school leadership.

There is a danger that teachers in PLCs may be trapped by an existing school discourse framing their actions (Philpott and Oates Citation2017). Researchers argue that PLCs must stimulate teachers to pose questions and dare to think themselves and to escape habits and routines, in order to promote alternative discourses (Dobie and Anderson Citation2015; Grossman, Wineburg, and Woolworth Citation2001; Philpott and Oates Citation2017).

According to Bleicher (Citation2014), motivation is the decisive factor for a successful PL process. Motivation includes both teacher self-efficacy and teacher dispositions (the amalgam of attitudes and values, beliefs about teaching and learning, personality traits and prior experiences). Motivation is conceived as supporting the quest for more knowledge, and more knowledge increases self-efficacy in a feedback process. Bleicher (Citation2014) states that the Collaborative Action Research (CAR) model, consisting of four components (Motivation, Knowledge, Action and Reflection), can provide a useful framework for projects aiming to develop teaching practices. The CAR model is founded on a collaborative way of working and has student learning in focus, and thus there is a similarity to Timperley’s Citation2011 theoretical framework. Timperley’s framework also highlights the importance of the engagement of the entire organization in the development process. We applied the CAR model (described in more detail in the method section) and Timperley’s framework, which makes visible the difference between PD and PL, when we compared and discussed the findings in a meta-perspective.

Research design

Context and participants

Invitation to participate in the project was sent to schools through the university and a national network for principals. It was clarified that we were interested in doing research only with schools applying a collective approach when developing teaching in mathematics and science. In Sweden, it is relatively common that teachers are teaching mathematics as well as science, and therefore this study focused on these teacher groups and their principals. They were informed that participation was voluntary, and they were to withdraw at any time. Seven schools accepted our invitation, but after the first research meeting one of them withdrew from the project. The remaining six schools constituted four separate cases (). Three of the schools were in the same municipality with close cooperation and therefore constituted one case (Case 2).

Table 1. Background information about the participating schools.

Research method and procedure

Our study was a collective case study including four cases (). Yin (Citation1984, 23) defines the case study research method ‘as an empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context; when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident; and in which multiple sources of evidence are used.’ Stake (Citation1995) distinguishes three types of case studies: the intrinsic, the instrumental and the collective. One of the most frequent objections to the case study as a method is its low generalizability, because of only one or very few cases being studied. Regarding collective case study, the researcher brings together data from several different sources, such as schools or individuals, so collective case studies may allow for generalization of findings to a bigger population (Stake Citation1995). Our aim was, however, not to generalize but to find patterns in teachers’ collective work in different school contexts.

Data were collected by focus-group interviews with teacher teams and individual semi-structured interviews with principals. Individual semi-structured interviews with principals were done to reduce the possible impacts of a power imbalance between teachers and principal. The focus-group interview is a collectivistic research method (Madriz Citation2000) where a small group of people with similar background is interviewed by a researcher/moderator for one to two hours (Patton Citation2002). The participants’ perceptions and ideas about selected topics are explored in a non-threatening environment. Group interactions are encouraged and utilized, and this is an important criterion as it distinguishes focus groups from other types of interviews (Patton Citation2002; Rabiee Citation2004).

The participants were informed by letter that the project would involve two visits from researchers, one interview and one follow-up meeting. The letter explained that during the interview the teachers would be asked to describe how they work together to develop teaching and learning in science and mathematics. Correspondingly, the principal would be interviewed about how she/he works to stimulate development of teaching and learning. The letter also explained that during a follow-up meeting, the researchers’ interpretation of the interviews would be discussed with teachers and principal so that any misinterpretations could be adjusted.

Before the interviews the 11 open-ended topics were sent to teacher teams and principals in the participating schools, in order to have time to reflect on them in advance. They were: Organization of and time for teacher team meetings, Subject progression, Intentions of curriculum and syllabuses, Teacher continuing education, Teaching methods, Assessment, Pupil pre-understanding and learning, Documentation of teaching experiences and pupil learning, Collaboration within teacher teams and within the school, Other important factors influencing subject teaching, Benefits of and barriers to collective work. During the focus-group interview in the different cases the open-ended topics were discussed one by one by the teacher teams. The researchers interrupted only to ask participants to clarify statements or to find out whether there was consensus within the teacher group. The school principals were interviewed (individual semi-structured interview) using the same open-ended topics one by one and with interruptions only to clarify statements. The written analysis of the interviews was sent to principals and teachers to enable adjustment of any misinterpretations. This was done to reduce the possible impacts of a power imbalance between researchers and participants. The written analysis was also discussed in a follow-up meeting.

Data analysis

The data from the cases were first analysed, one by one, by using pattern coding (Miles and Huberman Citation1994). To reduce the potential bias when analysing and interpreting data from focus-group interviews, Krueger (Citation2014) stresses that the analysis should be systematic, sequential, verifiable and continuous. In the first step, we summarized interview segments in the 11 selected open-ended topics and then presented and discussed the interpretations of the data with the participants in order to establish validity (McNiff Citation2002). In the second step of coding, segments related to the first research question (How do teacher teams and principals work to develop teaching and learning in science and mathematics?) were analysed. The theoretical framework on PL that focuses on pupil learning and highlights the importance of the involvement of the entire organization was used for analysis (Timperley Citation2011). All statements concerning pupil learning and the organization of work to improve teaching and learning were marked with different colours and these coded segments resulted in four qualitatively different categories. Segments related to the second research question (Which benefits of and barriers to collective work do teachers and principals perceive?) were first marked with different colours. Segments concerning benefits resulted in six qualitatively different main categories divided in sub-categories. Statements about the barriers were relatively few and they are all described in the result section without categories. To establish the reliability of data analysis the two researchers coded the transcriptions independently. The different categories were then compared and discussed until consensus was reached.

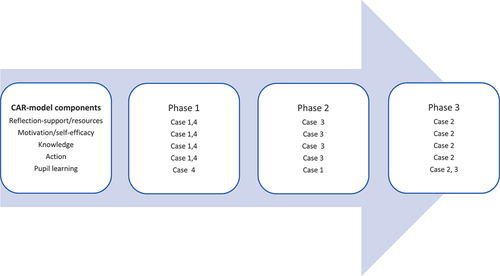

In the discussion we have made comparisons between the cases in a meta-perspective, using both Timperley’s Citation2011 framework of PL and the CAR model of Bleicher (Citation2014) consisting of four central components: Motivation, Knowledge, Action and Reflection. Motivation includes both teacher orientation in terms of teacher disposition (for example, the amalgam of ideas about teaching and learning) and self-efficacy to develop teaching practices. Knowledge refers to new subject matter knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge and resources in order to improve practices of teaching. Action relates to a teacher’s enactment of new teaching strategies and resources. The last component is Reflection, a fundamental aspect for sustainable change in practice; a mental activity that allows careful consideration of personal ideas and new knowledge. Timperley’s framework highlights the importance of the engagement and support of the entire organization in the development process. In the CAR model, as well as in Timperley’s theoretical framework on PL, pupil learning is central and therefore we made pupil learning explicit as a fifth component in the CAR model when we analysed and discussed our findings in a meta-perspective.

Findings

How to work collectively to develop teaching and learning

The analysis of the data related to the first research question resulted in four categories: Collaboration, Knowledge about pupil learning in praxis, Continuing education and Language skills.

Collaboration

This category describes how different schools organized their collaboration. In all the schools the teachers in mathematics, science and technology were organized in common subject teams. They had weekly meetings with a chair, who in case 2 is a trained teacher in subject didactics. In cases 1 and 4, principals were informed about discussions during meetings through written protocols. In cases 2 and 3, the principals attended the meetings: ‘I schedule myself. I can’t attend every meeting but I try to participate at least a few times a month’ (Principal case 3). The principals were also more involved in the development work. The principal in case 2 stated:

If something does not work in the classroom, I must support. The team chairs and I supervise together; we conduct one lesson each. In this way we support, and the teacher also gets his/her subject colleagues’ point of view on subject teaching.

In cases 2 and 3 the collaboration between teachers had a specific scaffolding framework. The collaboration model in case 2 is called ÄmnesDidaktisktKollegium, ÄDK (Pedagogical Content Knowledge Collegium, PCK-C). The teachers were using the Learning Study model and variation theory as a theoretical framework (Marton and Pang Citation2006); content analysis of the object of learning and making the critical aspects visible are fundamental components in developing teaching and pupil learning. Teachers in case 2 also collaborated about so-called frame lessons, which increase lesson structure where, e.g. image support is included to improve language skills and thereby pupil learning. The overall disposition of a frame lesson is: purpose, goals, flashbacks, agenda and summary. The principal in case 2 stated: ‘We also work with image support and frame lessons, aiming to support the pupils’.

In case 3, the collaboration in the teacher team was supported by using assessment matrices. They were used by the teachers, e.g. to get a common view of what it means to have knowledge in a specific content area. The working method in case 3 was initiated by the teachers themselves and in case 2 by a successful pilot study in a teacher team.

In conclusion, the collaboration in cases 2 and 3 was more developed and had a stronger focus on pupil learning than in cases 1 and 4.

Knowledge about pupil learning in praxis

This category describes how knowledge about pupil learning is used to develop teaching and pupil learning. In cases 1 and 4, a systematic development of teaching by analysing pupil achievements was essentially missing. Individual teachers used different types of formative and summative assessments, but there was no uniform system for making pupil learning visible and how to use this knowledge to develop teaching.

T2 case 1: We see, in some parts, for example in algebra, the pupils have weak mathematical understanding every year. We analyse the results of the national tests, what kind of difficulties do pupils have.

R: How do you use this knowledge?

T1 case 1: I cannot say that we have any systematic work on this. You may discuss it more with a colleague, but we have no systematic approach.

In cases 2 and 3, the systematic development of teaching had a focus on pupil learning. Pre- and post-tests (entrance and exit tickets) were used to make learning visible and to develop teaching. The principal in case 2 stated: ‘Through exit tickets, pupils can see their own learning process and then it becomes much more fun’. A teacher described how they work:

T1 case 2: We use entrance tickets, pre-test to see pupil pre-knowledge. What is critical? And we plan together how to teach. How should we achieve the learning? And then we teach and the following week we analyse and evaluate the results.

R: Post-test?

T1 case 2: Yes, and has there been any learning, yes, or no? Do we see new critical aspects? What are we going to develop to improve teaching? And this goes on.

In case 3, the teaching was developed by using matrices. Learning matrices are intended to help pupils to see learning goals and their own learning process, and were used by teachers for developing teaching.

T2 case 3: Learning matrices make the learning visible to pupils.

R: How do you work with this?

T4 case 3: We have developed the learning matrices together with the pupils … The idea is that you should construct the matrices together with the pupils … . It should be their words and interpretation of what is demanded to achieve learning outcomes.

Our conclusion is that the schools in cases 2 and 3 had more developed systems for making pupil learning visible and they worked more systematically with development of teaching based on pupil achievements.

Continuing education

This category describes the continuing education in the schools. In case 1, continuing education has had a different focus every year. The main idea was that everyone should have the same basic competences; for example, all the teachers had taken a course in leadership and in information and communications technology. In case 4, the principal stated: ‘If we look at the overall competence development, it has focused very much on reading in recent years’.

In case 2, principals and all staff in the schools received education mainly through the work in the PCK Collegium. Principals and teachers prioritized this because it had direct effects on teaching and pupil learning.

T1 case 2: The meetings in PCK-C are scheduled. The principals have pointed out the importance of these meetings and nothing else can disturb them.

T2 case 2: We follow a template. We reflect on the pupil achievements. What they have learned or not learned and how do we make sure that they learn next time? Pupil learning is in focus. PCK-C is our professional development, and we also have an external education in PCK-C. Pupil learning is the most important aspect in our work. Our development is not the most interesting, but the pupil learning.

R: But you develop as well?

Everyone case 2: Yes, we do!

T1 case 2: But it is not a short-term project for the teachers; the main goal is to increase pupil learning. That is what is important.

External educators were occasionally involved in these PCK Collegiums. The chair of the teams received training from external educators every year. Other shorter training efforts were avoided in case 2, as they were found to have minimal impact on pupil learning.

Principal case 2: The teachers’ view is that they gain professional development through PCK-C. We are reflecting about why we should do this. What does it give us? Not so many one-day events that are fun for the moment; they do not influence the teaching (and pupil learning). We are restrictive with such kinds of one-day educations. But that’s not a problem; there are not many requests for such short educations. We have education about PCK-C and variation theory for all staff. New employees are always introduced in PCK-C. We always talk about our way of working as early as during job interviews.

In case 3, the teachers systematically used assessment and learning matrices. The assessment matrix was a tool used by teachers, and a learning matrix mainly by pupils. Both the principal and the teachers prioritized the use of these matrices, and the meetings had a strong focus on how to develop their use.

T3 case 3: During our weekly meetings we work with learning matrices for all grades and all subjects.

T2 case 3: And our principal is also very involved in this work.

T1 case 3: Assessment matrices are well known but learning matrices are more useful for pupils.

T2 case 3: Because they are used in a formative purpose.

Principal case 3: The teachers develop learning matrices together with the pupils to enable pupils to understand the aim of the subject teaching. They reflect and analyse together. Learning matrices, they are a part of our quality work. We also strive for fair examination, that we use assessment matrices in the same way.

In conclusion, in cases 2 and 3 the continuing education included principals as well as teachers and had a strong focus on pupil learning.

Improving language skills

This category describes that language skills are a prerequisite for pupil learning. All the schools emphasized the importance of improving pupil reading and writing because it influences learning in all subjects. In cases 1 and 3, all teachers had received external education (through the Swedish National Agency for Education) to support pupil learning in the Swedish language (e.g. through image support). In case 2, the whole school had taken a holistic approach without external help. The teachers in all subjects read aloud with the pupils several times every week in all grades, and they also used aids such as image support in their teaching.

Principal case 2: Many pupils who started in grade 4 still could not read. We said, this is unsustainable; we must do something about it. And we cannot blame [teachers in] earlier grades. Those who cannot read will never get a chance to learn. … and the years go by and pupils are still very weak in reading. You teach them all the time and they do not understand. We must close the gap concerning reading skills. Teachers’ reading efforts started in January in grades 1 to 3, and already after 6 months, the pupils who started in grade 4 could read better than pupils in grade 5. Then we decided that we must continue this effort for all three schools. Today all the teachers are reading with their pupils. Pupils in grades 4 to 6 have scheduled time for reading half an hour four times a week. Pupils in grades 7 to 9 have reading 20 minutes three times a week. We also employed two school librarians who visit lessons and provide teachers and pupils with inspiration. We have ordered many new books. Nobody says that reading is boring. Everyone thinks it is fun.

In case 4, the teachers in all subjects had been trained by a special pedagogue to be able to make general adjustments in the classroom concerning reading and writing.

Principal case 4: We have a very talented special pedagogue who has engaged all the teachers in making general adjustments in the classes, and therefore no plan of action concerning reading and writing difficulties has been written for individual pupils in the school last year.

We conclude that all the schools emphasized the importance of improving pupil reading and writing skills, but they were using different strategies.

Benefits and barriers

Benefits of collective work

shows the main benefits of collective work that were expressed in six categories (Pupil learning, Teacher peer learning, Self-efficacy, Systematic development work, Theoretical grounding, Change in school culture) and their sub-categories. The patterns of benefits illustrate differences between the cases. Most benefits verified by both teachers and principal were found in case 2.

Table 2. Expressed benefits of collective work in the different cases. T (Teacher), P (Principal). Bold text illustrates that both teachers and principal expressed this benefit.

In case 2, the benefits of collective work were the strong focus on pupil learning, increased teacher peer learning, and increased teacher and pupil self-efficacy. One of the teachers expressed their thoughts about pupil self-efficacy: ‘Pupils see their own learning process and it increases the motivation to learn. They become more active during the lessons and in their own learning’. Furthermore, their way of working was systematic and theoretical grounded, and had resulted in changes in school culture.

T3 case 2: In the beginning, we talked a lot about PCK lessons [with pupils], but then it has become like a culture. … now we no longer say [to pupils] that we have PCK lessons. Now the pupils are used to them.

T2 case 2: And the way of thinking about planning [the lessons] – to start from critical aspects. … It’s about how to approach teaching, the pupils’ need for learning and what is critical in the object of learning. We also apply this approach in other subjects.

In case 4, the way of working increased teacher peer learning (). However, statements about increased pupil learning, self-efficacy, systematic development, theoretical grounding of their work and change in school culture were not expressed.

Barriers to collective work

Different barriers were described by the schools. Time, continuity and deficiencies in teacher collaboration could be barriers to collective work. In case 1 it was lack of time for meetings and in case 3 lack of time for studying other teachers’ ways of teaching. Case 2 highlighted the problem of how to create continuity in work when new teachers join the teacher teams.

T2 case 2: A problem is how to deepen both the work and the learning process in the PCK-C at the same time as new staff are to be involved in the working model, e.g. to be introduced to new theoretical concepts such as critical aspects and content structure.

In case 4 the barriers were about deficiencies in teacher collaboration. T3 in case 4 states: ‘If there are interpersonal conflicts in the group it creates stress’. The principal describes the problem as follows: ‘Lack of trust and willingness to compromise in the teacher group is a problem’.

Discussion

The findings showed how the collective work was organized in the different schools and the perceived benefits and barriers expressed by teachers and principals. As a framework for further analysis, we have combined the theoretical framework on PL by Timperley (Citation2011) and the CAR model of Bleicher (Citation2014). The components of the CAR model were used to compare the cases in a meta-perspective and to illustrate the different phases of PD to PL among the participating schools ().

Bleicher (Citation2014) argues that reflection is often included in PL models, yet the support and resources to create conditions for it are frequently missing. The starting point in our meta-discussion is to describe how the schools have created conditions for reflection. All the schools had teacher teams aiming to increase reflection on teaching practices. However, the engagement of principals was stronger in cases 2 and 3. In case 2 there was also a trained team leader, and the work was research grounded through a theoretical model and external resource persons. The findings indicated that the support and resources for reflection were most developed in case 2 (, phase 3).

In cases 2 and 3 the collective way of working increased teacher self-efficacy, an important component of motivation (Bleicher Citation2014). Participants in case 2 stated that their work also improved the communication with pupils and increased their self-efficacy (, phase 3).

Knowledge refers to both new subject knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge and makes teachers feel empowered to change their practices (Bleicher Citation2014). The collective work facilitated teachers in all cases in considering each other’s perspectives of teaching and learning and created an increased sense of collegiality. All schools emphasized the importance of working together to increase pupils’ language skills. In case 1 the continuing education was changed every year, and in case 4 the focus had been on language skills. The continuing education in cases 2 and 3 was founded on a theoretically grounded model and different matrices to improve teaching and learning of the subject. In case 3, learning and assessment matrices included perspectives on subject knowledge and pedagogical content knowledge. Principals in case 2 participated together with teachers in the continuing education, and hence the new knowledge base was shared throughout the entire organization (, phase 3). In the PCK Collegium (case 2) teachers analysed and discussed critical aspects of the object of learning and subject knowledge as well as pedagogical content knowledge. They also systematically used the outcomes from pre- and post-tests to develop their teaching and pupil learning.

The component of teacher action is central to the CAR model, and in which teachers are leaders of their own PL. According to Bleicher (Citation2014), two elements are required to allow teachers to take action. Firstly, teachers define their own PL needs in relation to school improvements and learning. Secondly, to effect changes in practices, support and resources must be given. In cases 1, 2 and 3 a benefit of collective work was that pupil learning and achievement were in focus. In contrast to case 1, cases 2 and 3 had scaffolding frames – the theoretical framework used in the PCK Collegium and the learning and assessment matrices. The new knowledge actively engaged teachers in case 2 in planning and implementation of new ideas, and they highlighted increased teacher as well as pupil self-efficacy (, phase 3).

The notion of PL emphasizes the importance of pupil learning. Therefore, the core in the CAR model, pupil learning, is made explicit in our meta-discussion. Participants in cases 1–3 considered that a benefit of a collective way of working was that pupil learning is central. However, considering all the components in the model we argue that cases 2 and 3 have pupil learning more actively in focus; improving pupil learning and making learning processes visible are emphasized (, phase 3).

Theoretical consideration

Our findings indicated that case 2 was in development phase 3 where professional learning is pronounced (). According to Timperley (Citation2011), the involvement of the entire organization is important in the process from PD to PL. In case 2 both teachers and principals verified most benefits with their collective work, and this supported our conclusion. Case 4, on the other hand, was mainly in the first development phase (), where the clear focus on pupil learning was missing and where teachers and principal expressed few benefits of collective work. This can be also discussed in the light of the collaboration model, which differentiates three levels (Gräsel, Fußangel, and Pröbstel Citation2006) described by Muckenthaler et al. (Citation2020). We found that the development phase in case 2 correlated to the third level of collaboration, Co-construction, where collaboration is more intensive and includes the development of common knowledge and solutions to problems. One danger on this level is that teacher autonomy decreases, and this may lead to conflicts (Muckenthaler et al. Citation2020). In case 2, however, the whole school was involved in the developing process, with a robust commitment and a strong collaboration between teachers, and between teachers and principals. The important role of leaders in creating trust and motivation is highlighted by several researchers (Hallam et al. Citation2015; King Citation2016; Louws et al. Citation2017; Takahashi and McDougal Citation2016). The participants in case 4 (, phase 1) stated that a lack of trust and personal conflicts were barriers that prevented collective development.

Participants in case 2 pointed out the importance of increased knowledge that leads to both teacher and pupil increased self-efficacy, and this corresponds with findings that professional growth should be adjusted to the teachers’ needs in order to improve teaching and pupil learning (Kellner and Attorps Citation2015; King Citation2016). Research highlights the connection between work identities (personal and collective) and health issues among Swedish teachers (Nordhall et al. Citation2020; Nordhall, Knez, and Saboonchi Citation2018). It was found that when teachers thought more and felt less regarding their collective work identity, they felt mentally better and less exhausted. This can be compared with findings by Owen (Citation2015) indicating that the key impacts from well-functioning PLCs, where collegial work is a prerequisite, seem to be increased well-being of teachers and students.

The participants in all the cases were agents with authority and ability to change their practices. However, researchers (Visnovska and Cobb Citation2015; Wilson et al. Citation2017), have found that teachers often lack efficient methods, such as a scaffolding framework, for reflecting on student prior knowledge and learning, which is consistent with our findings in cases 1 and 4. In contrast, teachers in case 3 were reflecting by using learning and assessment matrices and in case 2 they focused on the object of learning and systematically analysed pupil learning using pre- and post-tests. Using a scaffolding support, for example a theoretical framework for collective reflection or/and external support, has been found to improve teaching and pupil learning (Attorps and Kellner Citation2017; Kellner and Attorps Citation2020; King Citation2016; Takahashi and McDougal Citation2016). The supporting framework in cases 2 and 3 influenced the two levels of practice (Visnovska and Cobb Citation2015) – the offline activities of teachers as well as online activities in the classroom. Moreover, the findings from case 2 were in line with earlier intervention studies stressing the importance of external support that initiates processes led and owned by the teachers (Engeström and Sannino Citation2010, Gonzales, Deal, and Skultety Citation2016; Kellner and Attorps Citation2020; Takahashi and McDougal Citation2016).

Conclusions and limitations

The overall aim in our study was to increase knowledge about factors influencing collective development of teaching and learning in different school contexts. By using the CAR model (Bleicher Citation2014) and the theoretical framework on PL by Timperley (Citation2011), we found that the schools in our study revealed different patterns of collective work and had reached different phases concerning PD to PL. We accept that the findings are context bound and should not be generalized without reflection. They may, however, contribute with knowledge about factors influencing collective development of practices in mathematics and science in different school contexts.

Implications for practice and future research

We argue that if planning to make changes aiming to improve teaching and learning it may be valuable to reflect on what the key questions are in the specific school context. Is there a scaffolding frame? Is there not just time, but trust and support for constructive reflections? Is there a need for increased subject knowledge as well as pedagogical content knowledge to stimulate self-efficacy and motivation? To what extent is the knowledge about pupil learning used to improve teaching? Is pupil learning central and visible in the school culture? In addition, in a Swedish context the question ‘Do pupils have enough language skills?’ may also be relevant. All these questions relate to cognitive aspects that can be discussed collegially at schools. Our findings indicate that these issues should be considered and discussed to a greater extent when the aim is to develop teaching and learning. We suggest more research on how these types of discussions may or may not develop the collective work in different school contexts, and thereby influence teaching and learning as well as teacher and pupil well-being.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Eva Kellner

Eva Kellner has a PhD in Plant Physiology and is a university lecturer in Biology at the University of Gävle, Sweden. She is experienced in the teaching of biology in teacher education, and her current research focus is teacher professional learning in biology.

Iiris Attorps

Iiris Attorps is a university lecturer and professor in Mathematics Education at the University of Gävle, Sweden. She is experienced in the teaching of mathematics for prospective teachers and engineers. Her research interest is teaching and learning of mathematics in compulsory school as well as at university level.

References

- Andresen, B. B. 2015. “Development of Analytical Competencies and Professional Identities Through School-Based Learning in Denmark.” International Review of Education 61 (6): 761–778. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-015-9525-6.

- Attorps, I., and E. Kellner. 2017. “School–University Action Research: Impacts on Teaching Practices and Pupil Learning.” International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education 15 (2): 313–330. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10763-015-9686-6.

- Avalos, B. 2011. “Teacher Professional Development in Teaching and Teacher Education Over Ten Years.” Teaching and Teacher Education 27 (1): 10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.08.007.

- Bleicher, R. E. 2014. “A Collaborative Action Research Approach to Professional Learning.” Professional Development in Education 40 (5): 802–821. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2013.842183.

- Bolam, R., A. McMahon, L. Stoll, S. Thomas, M. Wallace, and A. Greenwood . 2005. “Creating and Sustaining Effective Learning Communities.” In Research Report Number 637. London: General Teaching Council for England, Department for Education and Skills.

- Borko, H., J. Jacobs, and K. Koellner. 2010. “Contemporary Approaches to Teacher Professional Development.” In Third International Encyclopedia of Education, edited by P. L. Peterson, E. Baker, and B. McGaw, 548–556. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier.

- Darling–Hammond, L., and M. W. McLaughlin. 2011. “Policies That Support Professional Development in an Era of Reform; Policies Must Keep Pace with New Ideas About What, When, and How Teachers Learn and Must Focus on Developing Schools’ and Teachers’ Capacities to Be Responsible for Student Learning.” Phi Delta Kappan 92 (6): 81–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172171109200622.

- Darling-Hammond, L., and N. Richardson. 2009. “Research Review/Teacher Learning: What Matters?” Educational Leadership 66 (5): 46–53.

- Dobie, T. E., and E. R. Anderson. 2015. “Interaction in Teacher Communities: Three Forms Teachers Use to Express Contrasting Ideas in Video Clubs.” Teaching and Teacher Education 47: 230–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.01.003.

- Engeström, Y., and A. Sannino. 2010. “Studies of Expansive Learning: Foundations, Findings and Future Challenges.” Educational Research Review 5 (1): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2009.12.002.

- Fishman, B. J., R. W. Marx, S. Best, and R. T. Tal. 2003. “Linking Teacher and Student Learning to Improve Professional Development in Systemic Reform.” Teaching and Teacher Education 19 (16): 643–658. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(03)00059-3.

- González, G., J. T. Deal, and L. Skultety. 2016. “Facilitating Teacher Learning When Using Different Representations of Practice.” Journal of Teacher Education 67 (5): 447–466. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487116669573.

- Gräsel, C., K. Fußangel, and C. Pröbstel. 2006. “Lehrkräfte zur Kooperation anregen-eine Aufgabe für Sisyphos? [Encouraging Teachers to Cooperate – A Task for Sisyphus?” Zeitschrift für Pädagogik 52 (2): 205–219. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:4453.

- Grossman, P., S. Wineburg, and S. Woolworth. 2001. “Toward a Theory of Teacher Community.” Teachers College Record 103 (6): 942–1012. https://doi.org/10.1111/0161-4681.00140.

- Hallam, P. R., H. R. Smith, J. M. Hite, S. J. Hite, and B. R. Wilcox. 2015. “Trust and Collaboration in PLC Teams: Teacher Relationships, Principal Support, and Collaborative Benefits.” NASSP Bulletin 99 (3): 193–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192636515602330.

- Hauge, K., and P. Wan. 2019. “Teachers’ Collective Professional Development in School: A Review Study.” Cogent Education 6 (1): 1619223. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2019.1619223.

- Kellner, E., and I. Attorps. 2015. “Primary School Teachers’ Concerns and Needs in Biology and Mathematics Teaching.” Nordic Studies in Science Education 13 (3): 282–292. https://doi.org/10.5617/nordina.964.

- Kellner, E., and I. Attorps. 2020. “The School–University Intersection as a Professional Learning Arena: Evaluation of a Two-Year Action Research Project.” Teacher Development 24 (3): 366–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2020.1773522.

- King, F. 2016. “Teacher Professional Development to Support Teacher Professional Learning: Systemic Factors from Irish Case Studies.” Teacher Development 20 (4): 574–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2016.1161661.

- King, F., and H. Stevenson. 2017. “Generating Change from Below: What Role for Leadership from Above?” Journal of Educational Administration 55 (6): 657–670. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-07-2016-0074.

- Krueger, R. A. 2014. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research. London: Sage Publications.

- Little, J. W. 2012. “Professional Community and Professional Development in the Learning-Centered School.” In Teaching Learning That Matters: International Perspectives, edited by M. Kooy and K. van Veen, 22–46. London: Routledge.

- Lomos, C., R. H. Hofman, and R. J. Bosker. 2011a. “Professional Communities and Student Achievement – A Meta-Analysis.” School Effectiveness and School Improvement 22 (2): 121–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2010.550467.

- Lomos, C., R. H. Hofman, and R. J. Bosker. 2011b. “The Relationship Between Departments as Professional Communities and Student Achievement in Secondary Schools.” Teaching and Teacher Education 27 (4): 722–731. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.12.003.

- Louws, M. L., J. A. Meirink, K. van Veen, and J. H. van Driel. 2017. “Exploring the Relation Between Teachers’ Perceptions of Workplace Conditions and Their Professional Learning Goals.” Professional Development in Education 43 (5): 770–788. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2016.1251486.

- Madriz, P. 2000. “Focus Groups in Feminist Research.” In Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by N. K. Denzin and Y. S. Lincoln, 835–850. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Marton, F., and M. P. Pang. 2006. “On Some Necessary Conditions of Learning.” Journal of the Learning Sciences 15 (2): 193–220. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls1502_2.

- McNiff, J. 2002. Action Research: Principles & Practice. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Miles, B., and A. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Muckenthaler, M., T. Tillmann, S. Weiß, and E. Kiel. 2020. “Teacher Collaboration as a Core Objective of School Development.” School Effectiveness and School Improvement 31 (3): 486–504. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2020.1747501.

- Nordgren, K., M. Kristiansson, Y. Liljekvist, and D. Bergh. 2019. Lärares planering och efterarbete av lektioner-Infrastrukturer för kollegialt samarbete och forskningssamverkan[Teacher Planning of Lessons and Follow-up Work: Infrastructures for Collegial Collaboration and Research Cooperation]. Research Report. Karlstad: Karlstad University Studies, 11.

- Nordhall, O., I. Knez, and F. Saboonchi. 2018. “Predicting General Mental Health and Exhaustion: The Role of Emotion and Cognition Components of Personal and Collective Work-Identity.” Heliyon 4 (8). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2018.e00735.

- Nordhall, O., I. Knez, F. Saboonchi, and J. Willander. 2020. “Teachers’ Personal and Collective Work-Identity Predicts Exhaustion and Work Motivation: Mediating Roles of Psychological Job Demands and Resources.” Frontiers in Psychology 11: 1538. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01538.

- Olsson, D. 2019. Improving Teaching and Learning Together: A Literature Review of Professional Learning Communities. Research Report. Karlstad: Karlstad University Studies, 23.

- Opfer, V. D., and D. Pedder. 2011. “Conceptualizing Teacher Professional Learning.” Review of Educational Research 81 (3): 376–407. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654311413609.

- Owen, S. M. 2015. “Teacher Professional Learning Communities in Innovative Contexts: Ah Hah Moments, Passion and Making a Difference for Student Learning.” Professional Development in Education 41 (1): 57–74. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2013.869504.

- Patton, M. Q. 2002. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Philpott, C., and C. Oates. 2017. “Teacher Agency and Professional Learning Communities; What Can Learning Rounds in Scotland Teach Us?” Professional Development in Education 43 (3): 318–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/19415257.2016.1180316.

- Postholm, M. B. 2012. “Teachers’ Professional Development: A Theoretical Review.” Educational Research 54 (4): 405–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2012.734725.

- Rabiee, F. 2004. “Focus-Group Interview and Data Analysis.” Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 63 (4): 655–660. https://doi.org/10.1079/PNS2004399.

- Soini, T., J. Pietarinen, and K. Pyhältö. 2016. “What if Teachers Learn in the Classroom?” Teacher Development 20 (3): 380–397. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2016.1149511.

- Stake, R. E. 1995. The Art of Case Study Research: Perspective in Practice. London: Sage.

- Stoll, L., R. Bolam, A. McMahon, M. Wallace, and S. Thomas. 2006. “Professional Learning Communities: A Review of the Literature.” Journal of Educational Change 7 (4): 221–258. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-006-0001-8.

- Takahashi, A., and T. McDougal. 2016. “Collaborative Lesson Research: Maximizing the Impact of Lesson Study.” ZDM Mathematics Education 48 (4): 513–526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-015-0752-x.

- Timperley, H. 2011. Realizing the Power of Professional Learning. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Vescio, V., D. Ross, and A. Adams. 2008. “A Review of Research on the Impact of Professional Learning Communities on Teaching Practice and Student Learning.” Teaching and Teacher Education 24 (1): 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2007.01.004.

- Visnovska, J., and P. Cobb. 2015. “Learning About Whole-Class Scaffolding from a Teacher Professional Development Study.” ZDM Mathematics Education 47 (7): 1133–1145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-015-0739-7.

- Wilson, P. H., P. Sztajn, C. Edgington, J. Webb, and M. Myers. 2017. “Changes in Teachers’ Discourse About Students in a Professional Development on Learning Trajectories.” American Educational Research Journal 54 (3): 568–604. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831217693801.

- Yin, R. K. 1984. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.