ABSTRACT

Working part-time can potentially be a great means of reducing work-life conflict for parents of young children. However, research has not univocally found this attenuating relation, suggesting it may not be universal, but rather contingent on other factors. This study investigates whether the relation between part-time work and work-life conflict is contingent on workplace support and gender. Results show that short part-time work (<25 h) relates to lower levels of work-life conflict for both women and men. We find some evidence that workplace support affects this relation: short part-time working women in an organization with a family supportive organizational culture had lower levels of work-life conflict than short part-time working women in organizations with an unsupportive organizational culture. For men working short part-time we find tendencies in the same direction, although this falls short of conventional statistical significance. In addition, long part-time work (25–35 h) is not significantly related to (lower) work-life conflict for either women or men. In line with previous research, managerial support is found to be linked to lower levels of work-life conflict, irrespective of whether one works full-time or part-time. Notably, the relation between working part-time and work-life conflict does not differ for mothers and fathers, suggesting that this work-family policy could help both men and women reduce work-life conflict.

RÉSUMÉ

Travailler à temps partiel peut potentiellement être un excellent moyen de réduire les conflits entre le travail et la vie personnelle pour les parents de jeunes enfants. Toutefois, les recherches n’ont pas trouvé univoque cette relation atténuante, suggérant qu’elle ne peut pas être universelle, mais plutôt subordonnée à d’autres facteurs. Cette étude examine si la relation entre travail à temps partiel et le conflit entre travail et vie personnelle dépend de sexe et de soutien du milieu de travail. Les résultats montrent que le travail à temps partiel court (< 25 heures) est lié à la réductions des conflits entre le travail et la vie personnelle des hommes et des femmes. Nous trouvons des preuves que le soutien au travail affecte cette relation: quelques femmes qui travaillent à temps partiel dans une organisation avec une culture organisationnelle favorable familiale avaient des niveaux inférieurs du conflit travail-vie personnelle que les femmes qui travaillent à temps partiel court dans les organisations avec une culture organisationnelle insatisfaisantes. Pour les hommes qui travaillent en bref a temps partiel, nous trouvons des tendances dans la même direction, bien que cela ne soit pas d’une portée statistique conventionnelle. En outre, le travail à temps partiel (25 à 35 heures) n’a pas de lien significatif avec le conflit (moins grave) entre le travail et la vie personnelle des femmes et des hommes. Conformément aux recherches précédentes, il y a été établi que le soutien de la direction était lié à des conflits de niveau moindre entre le travail et la vie personnelle, que l’on travaille à plein temps ou à temps partiel. Notamment, la relation entre travail à temps partiel et conflit entre travail et vie personnelle ne diffère pas entre les mères et les pères, ce qui suggère que cette politique travail-famille pourrait aider les hommes et les femmes à réduire les confits entre le travail et la vie personnelle.

Introduction

With the rise of non-traditional families and the erosion of traditional gender norms, fewer people are living in a heterosexual, traditional breadwinner-homemaker household, where one spouse (the husband) specializes in work and the other (the wife) in childcare and domestic tasks. Instead, many people are living in dual-earning or single-parent households and need to combine having a paid job with family responsibilities (Eurostat, Citation2015; OECD, Citation2011). Combining the two can be challenging, and may lead to work-life conflict, which is associated with lower wellbeing, as well as lower performance at work (e.g. Amstad, Meier, Fasel, Elfering, & Semmer, Citation2011). In order to help people to be better able to combine work and family responsibilities, many countries as well as employers offer employees work-family policies, such as the option to work reduced hours (den Dulk, Peters, & Poutsma, Citation2012).

Working part-time has the potential to be a great means of reducing work-life conflict, because it enables the employee to continue to be active in the labor market, while freeing up time for family responsibilities (Booth & van Ours, Citation2009). Therefore, it is sometimes seen as a win-win solution for parents wanting to work (Hill, Märtinson, Ferris, & Baker, Citation2004). However, research has found mixed evidence regarding the relation between work-family policies (including part-time work) and work-life conflict, with some finding the expected negative relation, some finding no effect, and some even finding that work-family policies increase work-life conflict (as discussed by: Beauregard & Henry, Citation2009; Beham, Präg, & Drobnič, Citation2012; Kelly et al., Citation2008). This indicates that the relation between working hours and work-life conflict is not as clear-cut as was initially assumed, but may function differently under different conditions. One such condition, which has often been overlooked by previous research, is the workplace context. Employees are embedded in organizations, and their use of work-family policies may be welcomed by their employer, but might also be frowned upon. Hence, workplace factors, such as support from the organization, manager and colleagues, can affect people’s experiences of using these policies. Workplace support has rarely been included in research on part-time work and work-life conflict, and might potentially account for the mixed findings of previous research. Hence, there has been a call to ‘bring the organization back in’ in this type of research (Barley & Kunda, Citation2001; Kalleberg, Citation2009), to which we hope to contribute.

In this study, we also investigate whether the relation between part-time work and work-life conflict is different for mothers and fathers. Previous research on the relation between work-family policies and work-family outcomes has concentrated on women, and little is known about how these relationships work for men (Clark, Rudolph, Zhdanova, Michel, & Baltes, Citation2017; Haas & Hwang, Citation2016). As work-family policies are increasingly made available to and used by men, a better understanding of gender differences in the outcomes of work-family policies is essential (Munn & Greer, Citation2015). However, given that men work part-time much less often than women, we unfortunately cannot conduct the same in-depth analyses for men as we can for women.

One further contribution will be made. Following some recent studies (Beham et al., Citation2012; Roeters & Craig, Citation2014) we will not just compare part-time work to full-time work, but also distinguish between short part-time work and long part-time work. By looking at different categories of part-time work we contribute to a more detailed understanding of the relation between part-time work and work-life conflict.

We focus on three Western European countries: the Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom, where part-time work is relatively common. We do so using multilevel organization-data from the European Sustainable Workforce Survey (van der Lippe et al., Citation2016), which include 1712 employees with a child under age 14, nested in 303 teams in 102 organizations. A great advantage of this dataset is that it enables us to combine information provided by the employees with information provided by their manager and the organization. This allows us to limit possible common method bias (which occurs when the same respondent reports on numerous variables) and control for unobserved organizational characteristics that might affect employee outcomes (Podsakoff, MacKenzie, Lee, & Podsakoff, Citation2003).

Policy background

Although part-time work is not a work-family policy per se – people can work part-time for reasons other than childcare (Eurostat, Citation2018) – it is in practice strongly intertwined with the labor force participation of mothers; by working part-time they are (better) able to combine their family life with work. In the 1950s organizations in the Netherlands started offering part-time jobs to mothers who otherwise would not have been in the workforce at all (Portegijs, Cloïn, Keuzenkamp, Merens, & Steenvoorden, Citation2008). Sweden was in 1978 the first country where access to reduced hours was introduced as a governmental work-family policy, aimed specifically at parents (in practice mothers), which was very successful in increasing female labor participation (Hegewisch & Gornick, Citation2008, Citation2011). However, although the popularity of part-time jobs increased in many European countries, they tended to be precarious and associated with lower job quality (e.g. regarding pay or training and promotion opportunities)(Warren & Lyonette, Citation2018). The European Union adopted its first directive on part-time work in 1997, with the aim to increase the quality of part-time work (part-time work directive 97/81/EC), yet to this day this remains a problem, especially for short part-time jobs. The right for parents to reduce their working hours is currently not included in European Union directives and many European countries do not offer this on their own account (Hegewisch & Gornick, Citation2008, Citation2011.

In this study we analyze the Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom. These three countries were purposely selected for this study, as they are high-users of part-time employment (Eurostat, Citation2017), and all have legislation in place that allows parents (and also non-parents in the Netherlands) to – under certain conditions – request a reduction of working hours (Hegewisch & Gornick, Citation2008, Citation2011).Footnote1 Still, the three countries differ from one another in their policies regarding gender equality and female labor force participation, and can be seen as belonging to three different clusters in Korpi’s (Citation2000; Korpi, Ferrarini, & Englund, Citation2013) typology of gendered policy models in modern welfare states: the Netherlands belonging to the traditional-family group, Sweden to the earner-carer regime, and the United Kingdom to the market-oriented, liberal group.

The Netherlands has relatively few policies aimed at supporting gender equality and more policies facilitating the traditional male breadwinner family (Korpi, Citation2000; Korpi et al., Citation2013). In the Netherlands a ‘one-and-a-half earners model’ has become dominant, with the majority of couples consisting out of a full-time working man and a part-time working woman – regardless of whether they have (young) children (Portegijs & van den Brakel, Citation2016; Visser, Citation2002). Although in recent years the Dutch government has focussed on increasing the (hourly) labor force participation of women in order to reduce women’s financial dependency and increase their professional opportunities, this has mainly led to a shift from short part-time hours to long part-time hours among women, and consequently the gender imbalance in working hours and (financial) rewards remains (Portegijs & van den Brakel, Citation2016). Although part-time work is much less common among men than among women, men’s part-time work is higher in the Netherlands than in any other EU-member state (Eurostat, Citation2017). In 2016 83% of mothers worked part-time, compared to 16% of fathers (EU Labour Force Survey, Citation2016).

Sweden is seen as belonging to the earner-carer regime because it actively supports dual-earner families and has many formal policies designed to support equality between the sexes, such as the parental leave insurance (introduced in 1974) and the use-it-or-lose-it (so called ‘daddy’) months, as well as high quality, heavily subsidized public childcare (Korpi, Citation2000; Korpi et al., Citation2013). This has contributed to high female labor force participation which to a large extent is full-time or long part-time (Swedish Labour Force Survey, Citation2016). The availability of work-family policies have made short part-time work less attractive as a solution for combining work and family (Lyonette, Citation2015). Even though Sweden scores high on (policies supporting) gender equality, there is still considerable occupational sex segregation, as well as gender inequalities in housework and childcare (Evertsson, Citation2014; Grönlund & Magnusson, Citation2016). In 2016, 34% of the Swedish mothers and nine percent of fathers worked part-time (EU Labour Force Survey, Citation2016).

Lastly, the United Kingdom can be seen as a market-oriented, liberal country. It neither actively supports gender equality, nor supports traditional gender roles, but leaves it up to market forces to shape gender relations (Korpi, Citation2000; Korpi et al., Citation2013). Working part-time is common among mothers in the UK, not least due to the costs of childcare, which are higher than in any other European country (Lyonette, Citation2015; Verhoef, Tammelin, May, Rönkä, & Roeters, Citation2016). If employees have worked for the same employer for over 26 weeks, they can request a reduction of working hours, however, there are more ‘opt out’ possibilities for employers than in the other two countries (EurWORK, Citation2014). Despite the EU directive, the level of protection for part-time employees and quality of part-time work in the UK lags behind other European countries, meaning that many part-time jobs are of low quality and are often found in occupations with lower occupational status (Lyonette, Citation2015; Warren & Lyonette, Citation2018). It should be noted that during the recession in the UK male part-time work has increased, but that this partially stems from an inability to find full-time employment (Lyonette, Citation2015). In 2016, 51% of mothers and nine percent of fathers worked part-time (EU Labour Force Survey, Citation2016).

Theory and hypotheses

Conceptual approach

Numerous conceptual approaches are employed when the interplay between work and life is studied. First, a distinction tends to be made between ‘work-life’ and ‘work-family’, with the latter referring more narrowly to engagement with children, while the former is seen as a broader concept that also encompasses other non-work aspects of one’s life (Chang, McDonald, & Burton, Citation2010). Some studies examine work-life balance while others focus on work-family conflict, and some uncertainty remains regarding their relation vis-á-vis one another. Many studies and actors (e.g. the European Union) treat balance and conflict as existing on opposite ends of a continuum, but as shown by Carlson, Grzywacz, and Zivnuska (Citation2009) they are theoretically distinct concepts, i.e. ‘balance’ is more than the absence of conflict. In our study we refer to work-life conflict, because even though some parents might be able to protect engagement in childcare against any spillover (and thus have low work-family conflict), they may still experience work-life conflict in that no time for other aspects of one’s life, such as leisure, remains. When we refer to work-life conflict we specifically mean ‘work-to-life conflict’ as we are interested in the central role of the workplace on employees’ experienced conflict, yet we are aware that the directionality might also be reversed (Mesmer-Magnus & Viswesvaran, Citation2005).

Work-life conflict

Work-family policies, including part-time work, are often made available to employees with the explicit intention of helping them increase work-life balance or reduce work-life conflict (Crompton & Lyonette, Citation2006). The construct of work-life conflict has its origins in role theory and the idea that having multiple responsibilities (i.e. work and family) can cause strain by competing for one’s time, energy and attention (Greenhaus & Beutell, Citation1985; Grönlund & Öun, Citation2010). Thus, reducing the responsibilities in one aspect of one’s life would lead to less strain and therefore less work-life conflict. Therefore, when employees work part-time this strain ought to be lower, as their work hours are shortened and fewer responsibilities are competing. Although research into the relation between part-time work and work-life conflict has hypothesized that employees working part-time have lower levels of work-life conflict, the findings so far are inconsistent (see: Beauregard & Henry, Citation2009; Beham et al., Citation2012; Kelly et al., Citation2008). In this article, we also hypothesize that employees who work part-time have lower levels of work-life conflict (Hypothesis 1), and study to what extent the relationship is modified by workplace support and gender.

The moderating role of workplace support

Following previous studies (Dikkers, Geurts, den Dulk, Peper, & Kompier, Citation2004; Thompson & Prottas, Citation2006) we identify three ways in which employees can experience (lack of) workplace support: through the organizational culture, through managerial support, and through collegial support. Organizations have a distinct organizational culture, which entails ‘the shared assumptions, beliefs, and values regarding the extent to which an organization supports and values the integration of employees’ work and family lives’ (Thompson, Beauvais, & Lyness, Citation1999). The organizational culture also entails norms determining what constitutes behavior of an ‘ideal worker’ (Acker, Citation1990), and through its organizational culture organizations convey to their employees whether working part-time is acceptable behavior. Managers may adhere to these organizational (ideal worker) norms, but they are independent actors who can also convey a different message (Darcy, McCarthy, Hill, & Grady, Citation2012; Hochschild, Citation1997; Thompson et al., Citation1999). Similarly, colleagues can be supportive or unsupportive towards employee’s family responsibilities (Berdahl & Moon, Citation2013; Kirby & Krone, Citation2002). Although all three forms of support influence each other – colleagues and especially managers influence the organizational culture, the culture influences managers and employees, and managers and colleagues influence each other – they can independently withhold or provide support for work-family issues.

Organizational culture

According to Acker’s (Citation1990) ideal worker-theory, gendered assumptions prevail in many organizations. Acker claims that organizational structures are not gender neutral, but rather centralize around a notion of an ‘ideal worker’ which is based on a traditional male breadwinner stereotype. This ideal worker exists only for the job, with no other (family) responsibilities. With nothing interfering, this employee can focus fully on work-related duties (Acker, Citation1990; Haas & Hwang, Citation2016; Munn & Greer, Citation2015). Organizations that value the ideal worker norm convey the message that employees should be highly committed to work, and that family responsibilities should not intervene. Workers who deviate from this norm, for example by working fewer hours or in other ways prioritizing one’s family, are not ideal workers and are therefore seen as less committed to their job. Commitment is implicitly assumed to be linked to productivity, and consequently, employers’ assumptions of employees’ work commitment may have consequences for their career progression (Hill, Märtinson, & Ferris, Citation2004; Lyonette, Citation2015). It follows that in these organizations part-time employees may feel the need to work harder during working hours or work overtime, in order to prove that they are still committed (Anttila, Nätti, & Väisänen, Citation2005; Larsson & Björk, Citation2017; Lyonette, Citation2015). However, in organizations that adhere less to the ideal worker norm and that have a more family supportive organizational culture, employees should feel less pressure to prove their commitment, and should therefore be better able to experience the positive effects of work-family policies such as part-time work. Therefore we hypothesize that the alleviating relation between part-time work and work-life conflict is larger for employees who work in an organization that has a more family supportive organizational culture (Hypothesis 2).

Managerial support

In addition to the general organizational culture, employees’ closest managers are important agents in creating a climate in which using work-family policies is either normalized or frowned upon. Managers hold a key position in shaping the future career of an employee, and employees are likely to want to impress their managers and live up to their expectations. Managers have their own norms which may or may not be in line with the general organizational (ideal worker) culture, and they signal these norms through providing or withholding support for employees’ family responsibilities (Darcy et al., Citation2012; Hochschild, Citation1997; Thompson et al., Citation1999). Through these different managerial views towards family responsibilities, employees might be more or less able to enjoy the benefits of working part-time. Therefore, we expect that the alleviating relation between part-time work and work-life conflict is larger for employees who have a more supportive manager (Hypothesis 3).

Collegial support

In many jobs employees spend a lot of time with their colleagues and are likely to value having a positive relationship with them. However, co-workers can vary in their supportiveness for an employee’s engagement in family responsibilities. Some co-workers are supportive, either because they believe this to be important, or because they experience similar work-life struggles themselves. However, others can feel resentful, for example if they work full-time and feel that their part-time working peers require them to pick up the slack and take over tasks when the part-timers are absent (Kirby & Krone, Citation2002). In addition, co-workers may also respond mockingly, especially towards male colleagues who deviate from the traditional ‘ideal worker’ expectation that men should be providers but not caretakers (Berdahl & Moon, Citation2013). Thus, we maintain that also the supportiveness of direct colleagues may affect whether employees feel the need to compensate for working part-time, or whether they are able to enjoy the benefits of reductions in work-life conflict. Therefore we expect that the alleviating relation between part-time work and work-life conflict is larger for employees who have more supportive colleagues (Hypothesis 4).

The moderating role of gender

Does working part-time relate differently to work-life conflict for men and women? Prevailing gender ideologies continue to assign the work role primarily to men, and the main responsibility for children to women (Kanji & Samuel, Citation2017). When mothers work part-time they conform to gender norms that still oppose full-time maternal employment (Booth & van Ours, Citation2009; Roeters & Craig, Citation2014). This might enable women to enjoy the benefits of working part-time without feeling a need to compensate for violating social norms of appropriate behavior (Akerlof & Kranton, Citation2000; West & Zimmerman, Citation1987). Men, however, might be less able to enjoy the positive benefits of working part-time, as prevailing gender ideologies and ideal worker norms expect them to be full-time workers. Part-time working fathers are thus more likely than part-time working mothers to feel a need to compensate for working part-time, in an attempt to prove their commitment to work and their manliness (Acker, Citation1990; Akerlof & Kranton, Citation2000; Kanji & Samuel, Citation2017; West & Zimmerman, Citation1987). Little research has studied the extent to which part-time work affects work-life conflict differently for men and women, and of the studies that did, neither Beham et al. (Citation2012) nor Eurofound (Citation2011) found any gender differences in work-life balance satisfaction. Worth noting, though, is that both focused on men and women generally, not only on parents. Based on the theories described above we do expect that any alleviating relationship between part-time work and work-life conflict is stronger for women than for men (Hypothesis 5). Moreover, given these gendered norms and expectations especially men would suffer from not having workplace support, and benefit from having this support, as working part-time for them is a greater deviation from the ideal worker norm than it is for women (Acker, Citation1990; Munn & Greer, Citation2015). Thus, we hypothesize that for men who have organizational (Hypothesis 6a), managerial (Hypothesis 6b) or collegial support (Hypothesis 6c), the alleviating relation between part-time work and work-life conflict is stronger than for women who experience these types of support.

Methodology

Sample

To test our hypotheses, we use multilevel organization data from the European Sustainable Workforce Survey (van der Lippe et al., Citation2016), collected in 2015/2016. Data include information on employees, their department or team (as reported by the department or team manager) and the organization (as reported by the HR-manager). We employed stratified purposeful sampling to include organizations varying on two preselected parameters: sector and size, in order to ensure that our sample is ‘informationally representative,’ building on the plausible assumption that job characteristics, human resource investments, and organizational challenges will meaningfully vary across organizational industry and size (Sandelowski, Citation2000). Organizations were sampled based on their representation of six different sectors (manufacturing, health care, higher education, transportation, financial services and telecommunication) and three different sizes (1–99 employees; 100–249; 250 or bigger) using a random sample of business lists of organizations, which was complemented by a convenience sample from alternative sources (e.g. personal connections and web searches). After organizations agreed to participate, employees and department-managers were addressed at work and asked to participate in an online survey or to answer a paper-and-pencil questionnaire. The total response rate was 61% among employees, 81% among managers, and 98% among the HR-managers. For our purposes we used a sub-sample of only parents with a child under 14 years of age living at home from the Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom. People with a missing value on gender were dropped from the analyses (n = 78), other missing variables were imputed using multiple imputations with regression switching (van Buuren & Oudshoorn, Citation1999), with the Multiple Imputations command from STATA. This led to a total sample of 1391 employees, nested in 291 teams in 101 organizations.

Measures

Work-life conflict

Our dependent variable is based on the work-to-home interference scale from SWING (Wagena & Geurts, Citation2000), and was constructed by taking the mean of three items: ‘How often does it happen that you do not have the energy to engage in leisure activities with your family or friends because of your job?’ ‘How often does it happen that you have to work so hard that you do not have time for any of your hobbies?’ and ‘How often does it happen that your work obligations make it difficult for you to feel relaxed at home.’ All statements are measured on a five-point Likert scale with the options ‘never’, ‘sometimes’, ‘regularly’, ‘often’, and ‘always’. All items clearly loaded on one item with an Eigenvalue of 2.23. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.84, indicating good reliability. A higher score on this variable indicates more work-life conflict.

Part-time work

As recent studies on the impact of part-time work on work-life conflict found that this relation was more substantial for people working short part-time than for those working long part-time (Beham et al., Citation2012; Roeters & Craig, Citation2014), we differentiate between 1 = short part-time work (24 h or less), 2 = long part-time work (25–35 h) and 3 = full-time work (36 h or more).

Workplace support

Organizational culture

The variable organizational culture represents the department or team manager’s answer to the question ‘Higher management encourages me to be sensitive to employees’ family concerns’ on a five-point Likert scale with the options ‘strongly disagree’, ‘disagree’, ‘neither agree nor disagree’, ‘agree’, and ‘strongly agree.’ By asking this question to the manager instead of to the employee, we limit common method bias; the bias that occurs when the same respondent reports on numerous variables (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003).

Managerial support

Managerial support is measured as the experienced managerial support as reported by the employee. The scale used is based on Thompson et al.’s (Citation1999) scale of work-family culture. A factor-analysis clearly identified one factor on which three items loaded strongly (0.64 and higher), and these three items had a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.72. The statements are ‘My manager is understanding when I have to put my family first,’ ‘Employees are regularly expected to put their jobs before their families’ (reverse coded) and ‘My manager is very accommodating of family-friendly needs,’ which are all asked on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree.’ The resulting variable is the mean of these three items and thus ranges from 1 to 5, where a higher value represents more managerial support for work-family issues. This question was asked to employees rather than to the managers themselves, as we deemed it more likely that social desirability bias would occur when the managers reported about themselves.

Collegial support

Collegial support is measured by the manager’s answer to the question ‘Many employees in my department are resentful when colleagues take extended leave to care for their newborns’ on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree.’ Again, this question was asked to managers rather than employees themselves to limit possible common method bias.

Respondent characteristics

Gender of the respondent is coded as 0 = female, 1 = male. We also controlled for the respondent’s age, whether the respondent has a partner (0 = no, 1 = yes), the respondent’s level of education in years (2–20), as well as the respondent’s occupational status (ISEI-code).

Department characteristics

We included a number of characteristics of the department where the employee works, and its manger, namely gender of the manager (0 = female, 1 = male), whether the manager has children (0 = no, 1 = yes), and the size of the department (i.e. number of employees; log of the continuous variable).

Organizational characteristics

Lastly, we controlled for a number of organizational characteristics, such as size of the organization (i.e. number of employees; log of the continuous variable), whether the organization is public or private/mixed (0 = public or charity, 1 = private or mixed) and the sector, which is included as six dummies (1 = manufacturing, 2 = health care, 3 = higher education, 4 = transportation, 5 = financial services, 6 = telecommunication). Finally, the country in which the organization was based was added as a control variable (1 = NL, 2 = Sweden, 3 = UK) in order to include country fixed effects. provides descriptive statistics of all variables.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics (SD).

Analytical strategy

The relation between working part-time and the experienced work-life conflict was analyzed using an OLS linear regression. To account for the fact that our observations are not independent (as employees are nested within their department), standard errors are adjusted by clustering on the department level.Footnote2 Separate analyses were run for men and women. In the first model, we include an indicator of part-time work, respondent, department, organizational and country control variables, and workplace support predictors. In the second model we include the interactions between part-time work and the workplace support predictors. Wald-tests are used to test whether the effects for men and women differ significantly.

Results

shows the results of the linear regression of working part-time and work-life conflict. For both women and men we find a significant relationship between short part-time work and work-life conflict (Model 1), indicating that people who work short part-time experience less work-life conflict than those who have a full-time job. No significant difference was found between employees with a long part-time job and those who work full-time. This thus partially supports Hypothesis 1, which states that working part-time relates to lower levels of work-life conflict. Few of the control variables are significant, but we find that for women work-life conflict is greater as years of education increases, and the larger the department in which she works. For men none of the control variables are significant. When it comes to workplace support, having a supportive manager is linked to lower work-life conflict for both women and men. In order to check if there is variation in employees’ experiences of part-time work based on the workplace context, interactions were included for family supportive organizational culture, managerial support and collegial support (Model 2). For women we find a negative interaction between short part-time work and family supportive organizational culture. In other words, working short part-time relates more strongly to work-life conflict for women in an organization with a family supportive organizational culture than in organizations where the culture is less supportive. For men the effect is in the same direction, but fails to reach significance. However, we do not find the same relationship for long part-time work for either women or men, and this thus only partially supports Hypothesis 2. Our analyses do not support Hypotheses 3 and 4 regarding the interaction between part-time work and managerial support and part-time work and collegial support, indicating that part-time work reduces employee’s work-life conflict independent of the degree to which the manager or colleagues are supportive.

Table 2. The relationship between part-time work and work-life conflict, for women and men.

In order to test whether the relation between part-time work and work-life conflict is different for men and women, as hypothesized in Hypothesis 5, we performed a Wald-test (Paternoster, Brame, Mazerolle, & Piquero, Citation1998) comparing the regression coefficients for the effects of part-time work in Models 1 for women and men. Results show no significant difference between either the coefficients for short part-time work (z = −.86, p = 0.196) or the coefficients for long part-time work (z = 0.55, p = 0.291), indicating that there is no statistically significant difference in the effect of part-time work between men and women. Thus, we find no support for Hypothesis 5. Moreover, Hypotheses 6a-c posed a three-way interaction between gender, the various forms of workplace support and part-time work. Considering most of the two-way interactions are neither significant for women nor for men, it follows that the three-way interactions cannot be significant either. We did a Wald-test to see whether the positive interaction effect of family supportive organizational culture that was found for women differed significantly from the coefficient for men. This was not the case (z = −0.19, p = 0.423). Thus, even though the coefficient for men fails to reach statistical significance, the tendency for men is also that working in an organization with a family supportive organizational culture positively interacts with the relation between part-time work and work-life conflict. Most likely this fails to reach statistical significance because the number of men working short part-time is very low. We reject Hypothesis 6a, 6b and 6c.

Country analyses

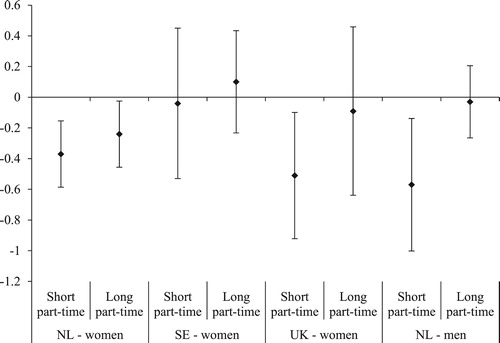

We ran our analyses separately per country in order to see whether the results differed or were driven mainly by one country. Results of the relation between part-time work and work-life conflict are presented in , and the full models can be found in Table A1. Unfortunately we had to exclude men in Sweden and the UK in the country specific analyses, as too few men worked part-time in these countries. shows the coefficients of work-life conflict for short and long part-time work and their confidence intervals. When confidence intervals do not include zero this means the coefficients are significantly different from zero. We see that short part-time work relates to lower levels of work-life conflict for all groups except Swedish women. For none of the groups does long part-time work relate to significantly different levels of work-life conflict than full-time work. As all the confidence intervals overlap, no country differs significantly from the others. Moreover, as can be seen in , for each of the four groups managerial support shows up as relating to lower levels of work-life conflict, but no interaction between part-time work and workplace support is found. For Dutch women we also find a relation between collegial support and work-life conflict, though in the opposite direction than we would have expected: women with supportive colleagues experienced more work-life conflict. It should, however, be kept in mind that there might be some power issues related to these analyses. The samples for Sweden and the UK are not very big, and some cells contain few people, most notably short part-time work, which is used by 11 Swedish women, 32 English women, and 13 Dutch men, and long part-time, which is used by 34 Swedish women and 18 English women.

Figure 1. Relation between working part-time and work-life conflict, for women in the Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom and men in the Netherlands, coefficients and confidence intervals. Note: presented coefficients result from the final models (without interactions), which are presented as model 1 in .

Additional analyses

As our workplace support factors might be multicollinear, we also ran our models including only one interaction at a time. Results were very similar, indicating that the results presented above do not suffer from multicollinearity. Additionally, we ran our analyses using multilevel modeling, which also led to similar results. Lastly, to check whether the analyses for men were driven by Dutch men only we conducted additional analyses where we use a dichotomous variable of full-time vs. part-time) for all six groups, as presented in . When interpreting this table it should be kept in mind that there are still very few men in Sweden and the UK who work part-time. The results show that in all six groups the relationships are as expected, i.e. the point estimates are in the same direction yet smaller and the coefficients are less often significant than for the more detailed part-time analyses, suggesting that the relation between part-time work and work-life conflict mainly exists for the short part-time jobs. The point estimates for all groups, except Swedish women, are in the same direction, suggesting that while the effects of English and Swedish men fall short of conventional statistical significance, the effect for men is not only driven by Dutch men.

Discussion

In this paper we have examined the relation between working part-time and work-life conflict for men and women in the Netherlands, Sweden and the United Kingdom. In addition, we studied whether this relationship is contingent on workplace support. Working part-time can potentially be a great means of reducing work-life conflict (Booth & van Ours, Citation2009) and is often offered and used for that particular reason, yet research has found mixed effects regarding the relation between part-time work and work-life conflict (Beauregard & Henry, Citation2009; Beham et al., Citation2012; Kelly et al., Citation2008). In this article we added to existing knowledge in three ways. First, contrary to most previous research we focused on workplace factors, and thereby contribute to a better understanding of how workplace support relates to the outcomes of work-family policies. Second, we examined both fathers and mothers. Previous research has mainly focused on women (Clark et al., Citation2017; Haas & Hwang, Citation2016), however, as work-family policies are increasingly made available to and used by men, it is important to include men in studies on work-family policy outcomes. Third, following recent studies (i.e. Beham et al., Citation2012; Roeters & Craig, Citation2014), we distinguished between short and long part-time work to get a more detailed understanding of how part-time work relates to work-life conflict.

Our findings suggest that especially short part-time work is associated with lower levels of work-life conflict, for both men and women. Thus, people who work in a short part-time job have lower levels of work-life conflict. After all, people who work part-time have fewer work responsibilities, and would thus have more time available for other activities, such as their family, hobbies, and leisure – and therefore experience less work-life conflict. However, although this relation seems intuitive, it had not always been found by previous studies (Beauregard & Henry, Citation2009; Beham et al., Citation2012; Kelly et al., Citation2008), nor was it clear whether this relation was contingent on gender and workplace support. It is noteworthy that no difference between men and women was found. Theoretically we expected men to experience fewer positive benefits from working part-time than women, because prevailing gender ideologies and ideal worker norms impose greater expectations on men to be full-time workers (Acker, Citation1990; Akerlof & Kranton, Citation2000; Kanji & Samuel, Citation2017; West & Zimmerman, Citation1987). Thus, when men work part-time this violate gender norms, and to compensate they might want to prove their commitment to work by working harder, meaning they would be less able to enjoy the positive benefits of working part-time than their female counterparts. This was not found to be the case, being in short part-time work was found to be a useful means of reducing work-life conflict, regardless of gender. This finding is in line with the work of Beham et al. (Citation2012) and Eurofound (Citation2011), who also did not find any gender differences in the relation between working part-time and work-life balance satisfaction for all employees (not only parents).

When it comes to long part-time hours, we did not find it to relate to lower levels of work-life conflict, for neither men nor women. This suggest that a possible explanation for the inconclusive findings of other studies regarding the relation between part-time work and work-life conflict may be that they do not distinguish between short and long part-time jobs. Our finding that only short part-time work relates to lower levels of work-life conflict is in line with the findings of two recent studies that also looked at the countries included in this study. Roeters and Craig (Citation2014) consistently found a significant difference in work-life conflict between women working short part-time and women working full-time, but only in some countries did this relationship also prevail for those in long part-time work. Moreover, Beham et al. (Citation2012) found that the relationship between part-time work and satisfaction with work-family balance was stronger for those working short part-time than for those in long part-time work.

Turning to the moderating effect of the workplace context, we found that women who work short part-time have lower levels of work-life conflict when they work in an organization with a family supportive organizational culture. For men we found a similar, although not significant relationship. Even so, we cannot rule out that such an effect exists due to the small number of men in short part-time work in our sample. We did not find an interaction between short part-time work and managerial or collegial support. These findings do not match our expectations: we expected that people who work part-time would feel the need to work harder, due to potential feelings of guilt about deviating from workplace norms that value physical presence and high commitment to the job (Acker, Citation1990; Anttila et al., Citation2005; Haas & Hwang, Citation2016; Lyonette, Citation2015; Munn & Greer, Citation2015). This would not fully enable them to experience the benefits from working part-time unless they experienced workplace support. Given gendered norms and expectations we expected that especially men would suffer from not having workplace support, as working part-time for them is a greater deviation from the ideal worker norm than it is for women (Acker, Citation1990; Munn & Greer, Citation2015). Our findings do not support this, also women who work short part-time experience higher work-life conflict if the organizational culture is unsupportive than when it is supportive. Moreover, the fact that we find this for short but not long part-time could be due to the deviation from ideal worker norms being more pronounced when one works short part-time compared to long part-time (Acker, Citation1990; Haas & Hwang, Citation2016; Munn & Greer, Citation2015). Additionally, our results showed that higher educated women and women in a larger department had slightly higher levels of work-life conflict than their counterparts with lower education and in smaller departments.

Although we found no evidence that the relation between part-time work and work-life conflict was contingent on managerial support, we did find that employees with a more supportive manager experienced lower levels of work-life conflict, irrespective of whether they worked part-time or full-time. This is perhaps not very surprising, after all, people who have a more supportive manager are probably capable of making ad-hoc arrangements with their manager, resulting in lower levels of work-life conflict (Abendroth & Pausch, Citation2018). It does, however, underline the importance of managers in the experience of work-life conflict of employees.

Due to power issues we cannot draw any strong conclusions regarding country differences. Our results showed that short part-time work relates to lower levels of work-life conflict for English and Dutch women and Dutch men, but not for Swedish women – but this difference was not statistically significant. More research into country differences is necessary to be able to make solid claims regarding whether the relation between part-time work and work-life conflict functions differently in different countries. However, such studies might be complicated by the relatively low levels of part-time work, and especially short part-time work, not least among men.

Limitations

The European Sustainable Workforce Survey was conducted with the aim of collecting detailed multilevel data within organizations. Its main strength is that it combines data provided by the employee, manager and organization, and thereby enables the investigation of the relation between workplace factors and employees, while also limiting common method bias (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003). However, there are also some limitations with our data that should be considered when thinking of the implications of this study, most notably that we cannot rule out a selection effect where people who experience more work-life conflict are the ones who start working part-time. Relatedly, workplace support may influence employees’ decision whether or not to work part-time – especially for men (Fernandez-Lozano, Citation2017; Larsson & Björk, Citation2017; van Breeschoten, Roeters, & van der Lippe, Citation2018). This would mean that men in unsupportive organizations are likely to select into full-time employment instead of part-time employment – even though they might want to work part-time. Moreover, people who value family supportiveness (in practice often women) are known to self-select into organizations that are family supportive and where it may be more common to work part-time, which further leads to gender-segregation in workplaces (Cortes & Pan, Citation2017). This should be kept in mind when interpreting our results, as well as when designing future research. Although this does not solve the issue completely, we recommend future studies to, as we did, include indicators that might capture organizational gender-segregation, such as sex of the manager and sector in which the organization operates.

Implications

On the basis of our findings we would like to underline two issues as main implications. First, part-time work, and especially short part-time work, can be a useful means for people to experience less work-life conflict. High levels of work-life conflict can relate to lower individual well-being (Amstad et al., Citation2011), higher societal healthcare costs (Higgins, Duxbury, & Johnson, Citation2004) and lower fertility rates (Begall & Mills, Citation2011; Soohyun, Citation2014). It is therefore important to provide parents with means to reduce work-life conflict. Thus (national) policy-makers would do well to give many employees the option to request a reduction in working hours, considering this more frequently ensures the maintenance of job quality than switching to a part-time job (Lyonette, Citation2015). Second, we found that working part-time is equally related to lower levels of work-life conflict for women and for men. This suggests the value of making part-time work – and perhaps work-life policies more broadly — available to men as well. Lastly, although not the focus of this paper, we found that employees with more supportive managers experienced less work-life conflict. Considering that high levels of work-life conflict are also associated with negative consequences for the organization, such as lower organizational productivity, higher absence and higher turnover (Amstad et al., Citation2011; Kossek & Ozeki, Citation1999) it should be in the interest of organizations to encourage managers to be supportive to all employees.

Conclusion

With this paper we extend the burgeoning knowledge about the sometimes ambiguous relationship of part-time work and work-life conflict among parents of young children, by including two moderators: workplace support and gender. Results show that short part-time work (<25 h) relates to lower levels of work-life conflict, but we did not find this for long part-time work (25–35 h). We find limited evidence that workplace support moderates this relation; short part-time working women in an organization with a family supportive organizational culture had lower levels of work-life conflict than short part-time working women in organizations with an unsupportive organizational culture. For men working short part-time we find an effect in the same direction, although this falls short of significance. We do not find a corresponding moderating effect of managerial support or collegial support. Notably, the relation between working part-time and work-life conflict does not differ for fathers and mothers, suggesting that this work-family policy could help both men and women reduce work-life conflict.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the European Research Council under Grant [number 340045]; the European Consortium for Sociological Research [internship grant to Leonie van Breeschoten].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Leonie van Breeschoten is currently doing her PhD at the Department of Sociology/ICS at Utrecht University, the Netherlands. She does research into questions regarding the combination of work and family life in European countries

Marie Evertsson is a Professor of Sociology in Social Policy at the Swedish Institute for Social Research (SOFI), Stockholm University. Her main research focus on the transition to parenthood and its career related consequences in an internationally comparative perspective among various types of couples.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For information on the specific conditions applying to the right to request, see for example Hegewisch (Citation2009).

2 Note that we also ran our analyses using multilevel modeling. Results are very similar. Considering the low intraclass correlation coefficient (.04 at the organization and .08 at the department), we decided to refrain from presenting the multilevel models here, but instead present the linear regression with cluster-adjusted standard errors.

References

- Abendroth, A. K., & Pausch, S. (2018). German fathers and their preferences for shorter working hours for family reasons. Community, Work and Family, 21(4), 463–481. doi: 10.1080/13668803.2017.1356805

- Acker, J. (1990). Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: A theory of gendered organizations. Gender and Society, 4(2), 139–158. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/189609

- Akerlof, G. A., & Kranton, R. E. (2000). Economics and identity. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(3), 715–753. doi: 10.1162/003355300554881

- Amstad, F. T., Meier, L. L., Fasel, U., Elfering, A., & Semmer, N. K. (2011). A meta-analysis of work–family conflict and various outcomes with a special emphasis on cross-domain versus matching-domain relations. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 16(2), 151–169. doi: 10.1037/a0022170

- Anttila, T., Nätti, J., & Väisänen, M. (2005). The experiments of reduced working hours in Finland: Impact on work-family interaction and the importance of the sociocultural setting. Community, Work and Family, 8(2), 187–209. doi: 10.1080/13668800500049704

- Barley, S. R., & Kunda, G. (2001). Bringing work back in. Organization Science, 12(1), 76–95. doi: 10.1287/orsc.12.1.76.10122

- Beauregard, T. A., & Henry, L. C. (2009). Making the link between work-life balance practices and organizational performance. Human Resource Management Review, 19(1), 9–22. doi: 10.1016/j.hrmr.2008.09.001

- Begall, K., & Mills, M. (2011). The impact of subjective work control, job strain and work–family conflict on fertility intentions: A European comparison. European Journal of Population / Revue Européenne de Démographie, 27(4), 433–456. doi: 10.1007/s10680-011-9244-z

- Beham, B., Präg, P., & Drobnič, S. (2012). Who’s got the balance? A study of satisfaction with the work–family balance among part-time service sector employees in five Western European countries. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(18), 3725–3741. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2012.654808

- Berdahl, J. L., & Moon, S. H. (2013). Workplace mistreatment of middle class workers based on sex, parenthood, and caregiving. Journal of Social Issues, 69(2), 341–366. doi: 10.1111/josi.12018

- Booth, A. L., & van Ours, J. C. (2009). Hours of work and gender identity: Does part-time work make the family happier? Economica, 76(301), 176–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0335.2007.00670.x

- Carlson, D. S., Grzywacz, J. G., & Zivnuska, S. (2009). Is work-family balance more than conflict and enrichment? Human Relations, 62(10), 1459–1486. doi: 10.1177/0018726709336500

- Chang, A., McDonald, P., & Burton, P. (2010). Methodological choices in work-life balance research 1987 to 2006: A critical review. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(13), 2381–2413. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2010.516592

- Clark, M. A., Rudolph, C. W., Zhdanova, L., Michel, J. S., & Baltes, B. B. (2017). Organizational support factors and work–family outcomes: Exploring gender differences. Journal of Family Issues, 38(11), 1520–1545. doi: 10.1177/0192513X15585809

- Cortes, P., & Pan, J. (2017). Occupation and gender. IZA Discussion Paper, 10672. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190628963.013.12.

- Crompton, R., & Lyonette, C. (2006). Work-life “balance” in Europe. Acta Sociologica, 49(4), 379–393. doi: 10.1177/0001699306071680

- Darcy, C., McCarthy, A., Hill, J., & Grady, G. (2012). Work–life balance: One size fits all? An exploratory analysis of the differential effects of career stage. European Management Journal, 30(2), 111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.emj.2011.11.001

- den Dulk, L., Peters, P., & Poutsma, E. (2012). Variations in adoption of workplace work–family arrangements in Europe: The influence of welfare-state regime and organizational characteristics. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 23(13), 2785–2808. doi: 10.1080/09585192.2012.676925

- Dikkers, J. S. E., Geurts, S. a. E., den Dulk, L., Peper, B., & Kompier, M. (2004). Relations among work-home culture, the utilization of work-home arrangements, and work-home interference. International Journal of Stress Management, 11(4), 323–345. doi: 10.1037/1072-5245.11.4.323

- EU Labour Force Survey. (2016). Retrieved from http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/lfs/data/database

- Eurofound. (2011). Part-time work in Europe. Employee relations (Vol. 19). Dublin: European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. doi: 10.1108/01425459710193108

- Eurostat. (2015). People in the EU: who are we and how do we live?. doi: 978-92-79-50328-3

- Eurostat. (2017). Part-time employment as percentage of the total employment, by sex and age. Retrieved from http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=lfsa_eppga&lang=en

- Eurostat. (2018). Main reason for part-time employment. Retrieved from http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=lfsa_epgar&lang=en

- EurWORK. (2014). UK: Right to request “flexible working” comes into operation. Retrieved from https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/observatories/eurwork/articles/working-conditions-industrial-relations-law-and-regulation/uk-right-to-request-flexible-working-comes-into-operation

- Evertsson, M. (2014). Gender ideology and the sharing of housework and child care in Sweden. Journal of Family Issues, 35(7), 927–949. doi: 10.1177/0192513X14522239

- Fernandez-Lozano, I. (2017). If you dare to ask: Self-perceived possibilities of Spanish fathers to reduce work hours. Community, Work and Family, 21(4), 1–17. doi: 10.1080/13668803.2017.1365692

- Greenhaus, J. H., & Beutell, N. J. (1985). Sources of conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 76–88.

- Grönlund, A., & Magnusson, C. (2016). Family-friendly policies and women’s wages – is there a trade-off? Skill investments, occupational segregation and the gender pay gap in Germany, Sweden and the UK. European Societies, 18(1), 91–113. doi: 10.1080/14616696.2015.1124904

- Grönlund, A., & Öun, I. (2010). Rethinking work-family conflict: Dual-earner policies, role conflict and role expansion in Western Europe. Journal of European Social Policy, 20(3), 179–195. doi: 10.1177/0958928710364431

- Haas, L., & Hwang, C. P. (2016). “It’s about time!”: Company support for fathers’ entitlement to reduced work hours in Sweden. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 23(1), 142–167. doi: 10.1093/sp/jxv033

- Hegewisch, A. (2009). Flexible working policies: A comparative review. Arndale House, Manchester: Institute for Women’s Policy Research, 1–96. Retrieved from https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/sites/default/files/research-report-16-flexible-working-policies-comparative-review.pdf

- Hegewisch, A., & Gornick, J. C. (2008). Statutory routes to workplace flexibility in cross-national perspective. Policy. Retrieved from www.iwpr.org

- Hegewisch, A., & Gornick, J. C. (2011). The impact of work-family policies on women’s employment: A review of research from OECD countries. Community, Work and Family, 14(2), 119–138. doi: 10.1080/13668803.2011.571395

- Higgins, C., Duxbury, L., & Johnson, K. (2004). Exploring the link between work-life conflict and demands on Canada’s health care system. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada. Retrieved from http://publications.gc.ca/collections/Collection/H72-21-192-2004E.pdf

- Hill, E. J., Märtinson, V., & Ferris, M. (2004). New-concept part-time employment as a work-family adaptive strategy for women professionals with small children. Family Relations, 53(3), 282–292. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.0004.x

- Hill, E. J., Märtinson, V. K., Ferris, M., & Baker, R. Z. (2004). Beyond the mommy track: The influence of new-concept part-time work for professional women on work and family. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 25(1), 121–136. doi: 10.1023/B:JEEI.0000016726.06264.91

- Hochschild, A. R. (1997). The time bind: When work becomes home and home becomes work (2nd ed.). New York: Metropolitan Books.

- Kalleberg, A. L. (2009). Precarious work, insecure workers: Employment relations in transition. American Sociological Review, 74(1), 1–22. doi: 10.1177/000312240907400101

- Kanji, S., & Samuel, R. (2017). Male breadwinning revisited: How specialisation, gender role attitudes and work characteristics affect overwork and underwork in Europe. Sociology, 51(2), 339–356.

- Kelly, E. L., Kossek, E. E., Hammer, L. B., Durham, M., Bray, J., Chermack, K., … Kaskubar, D. (2008). Getting there from here: Research on the effects of work-family initiatives on work-family conflict and business outcomes. The Academy of Management Annals, 2(1), 305–349. doi: 10.1080/19416520802211610

- Kirby, E., & Krone, K. (2002). “The policy exists but you can’t really use it”: Communication and the structuration of work-family policies. Journal of Applied Communication Research. doi: 10.1080/00909880216577

- Korpi, W. (2000). Faces of inequality: Gender, class, and patterns of inequality in different types of welfare states. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 7(2), 127–191.

- Korpi, W., Ferrarini, T., & Englund, S. (2013). Women’s opportunities under different family policy constellations: Gender, class, and inequality tradeoffs in western countries re-examined. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 20(1), 1–40. doi: 10.1093/sp/jxs028

- Kossek, E. E., & Ozeki, C. (1999). Bridging the work-family policy and productivity gap: A literature review. Community, Work and Family, 2(1), 7–32. doi: 10.1080/13668809908414247

- Larsson, J., & Björk, S. (2017). Swedish fathers choosing part-time work. Community, Work and Family, 20(2), 142–161. doi: 10.1080/13668803.2015.1089839

- Lyonette, C. (2015). Part-time work, work–life balance and gender equality. Journal of Social Welfare and Family Law, 37(3), 321–333. doi: 10.1080/09649069.2015.1081225

- Mesmer-Magnus, J. R., & Viswesvaran, C. (2005). Convergence between measures of work-to-family and family-to-work conflict: A meta-analytic examination. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67(2), 215–232. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2004.05.004

- Munn, S. L., & Greer, T. W. (2015). Beyond the “ideal” worker: Including men in work–family discussions. In M. J. Mills (Ed.), Gender and the work-family experience: An intersection of two domains (pp. 1–38). Springer International Publishing. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-08891-4

- OECD. (2011). Families are changing. Doing Better For Families, 17–53. doi: 10.1787/9789264098732-en

- Paternoster, R., Brame, R., Mazerolle, P., & Piquero, A. (1998). Using the correct statistical test for the equality of regression coefficients. Criminology; An interdisciplinary Journal, 36(4), 859–866. doi: 10.3366/ajicl.2011.0005

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879

- Portegijs, W., Cloïn, M., Keuzenkamp, S., Merens, A., & Steenvoorden, E. (2008). Verdeelde tijd: waarom vrouwen in deeltijd werken. Den Haag: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau.

- Portegijs, W., & van den Brakel, M. (2016). Emancipatiemonitor 2016. The Hague: Sociaal en Cultureel Planbureau/Centraal Bureau voor de Statistiek.

- Roeters, A., & Craig, L. (2014). Part-time work, women’s work-life conflict, and job satisfaction: A cross-national comparison of Australia, the Netherlands, Germany, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 55(3), 185–203. doi: 10.1177/0020715214543541

- Sandelowski, M. (2000). Combining qualitative and quantitative sampling, data collection, and analysis techniques in mixed-method studies. Research in Nursing & Health, 23(3), 246–255. doi:10.1002/1098-240X(200006)23:3<246::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-H

- Soohyun, K. (2014). The effects of work-family conflict and marital satisfaction on fertility intentions of married working women. Seoul: Seoul National University.

- Swedish Labour Force Survey. (2016). Swedish Labour Force Survey. Retrieved from https://www.scb.se/contentassets/5a6d6bf5609f42b3ba5d4f02bc255dc2/am0401_2016a01_sm_am12sm1701.pdf

- Thompson, C. A., Beauvais, L. L., & Lyness, K. S. (1999). When work–family benefits are not enough: The influence of work–family culture on benefit utilization, organizational attachment, and work–family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54, 392–415.

- Thompson, C. A., & Prottas, D. J. (2006). Relationships among organizational family support, job autonomy, perceived control, and employee well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 11(1), 100–118. doi: 10.1037/1076-8998.10.4.100

- van Breeschoten, L., Roeters, A., & van der Lippe, T. (2018). Reasons to reduce: A vignette-experiment examining men and women’s considerations to scale back following childbirth. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 25(2), 169–200. doi: 10.1093/sp/jxy003

- van der Lippe, T., Lippényi, Z., Lössbroek, J., van Breeschoten, L., van Gerwen, N., & Martens, T. (2016). European sustainable workforce survey [ESWS]. Utrecht: Utrecht University.

- van Buuren, S., & Oudshoorn, K. (1999). Flexible multivariate imputation by MICE. Leiden: TNO Prevention Center.

- Verhoef, M., Tammelin, M., May, V., Rönkä, A., & Roeters, A. (2016). Childcare and parental work schedules: A comparison of childcare arrangements among Finnish, British and Dutch dual-earner families. Community, Work and Family, 19(3), 261–280. doi: 10.1080/13668803.2015.1024609

- Visser, J. (2002). The first part-time economy in the world: A model to be followed? Journal of European Social Policy, 12(1), 23–42. doi: 10.1177/0952872002012001561

- Wagena, E., & Geurts, S. A. E. (2000). Swing: Ontwikkeling en validering van de ‘Survey Werk-thuis Interferentie-Nijmegen’ [SWING: Development and validation of the ‘Survey work-home interference- Nijmegen’]. Gedrag & Gezondheid, 28, 138–158.

- Warren, T., & Lyonette, C. (2018). Good, bad and very bad part-time jobs for women? Re-examining the importance of occupational Class for job quality since the ‘great recession’ in Britain. Work, Employment and Society. doi: 10.1177/0950017018762289

- West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H. (1987). Doing gender. Gender and Society, 1(2), 125–151.