ABSTRACT

In this Voices article, we use emerging evidence to reflect on the consequences of Covid-19 for various aspects of workers' wellbeing. This brief review emphasises how COVID-19 exacerbates existing, well-understood inequalities, along the intersections of community, work, and family. Workers on the periphery of the labour market, including non-standard workers and the self-employed, but also women and low-paid workers, are experiencing significant losses in relation to work, working hours and/or wages. Even once the pandemic is contained, its impact will continue to be felt by many communities, workers, and families for months and years to come.

In April 2020, the editorial board of Community, Work & Family wrote a Voices article, in which we identified a number of areas in which inequalities could be exacerbated in times of the COVID-19 pandemic alongside areas where potentially positive change could be achieved (Fisher et al., Citation2020). At the time of writing, 1 million individuals worldwide had been infected with COVID-19. By the time we received the page proofs, this number had increased to 2 million. As we reviewed the proofs for this piece in January of 2021, the number of infected persons worldwide is over 100 million. Our editorial insights of April 2020 were formulated as educated concerns based on theory, existing empirical knowledge from earlier crises, and early anecdotal and journalistic evidence. Now, almost one year later, significant amounts of empirical research on COVID-19 are emerging. In this follow-up Voices article, we use this emerging evidence to reflect on, and scrutinize, some of the issues raised in our earlier Voices article as it pertains to workers’ wellbeing, the topic of this special issue honouring former Community, Work & Family editors Laura den Dulk and Jennifer Swanberg.

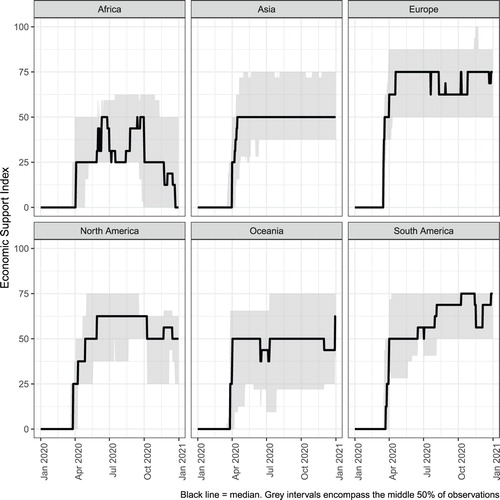

In what has been approximately the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, governments across the world have responded to contain or slow the spread of the virus, as well as to protect workers from the economic consequences of these measures. Our reflection starts by looking at a global overview of such economic efforts. , based on data from the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker (Hale et al., Citation2020), shows the levels of economic support provided by all countries in the world in their protection of workers, classified by continent. These scores are based on an index summarizing four economic support measures standardized to range from 0 (lowest effort) to 100 (highest effort): income support to workers, debt/contract relief (including the freezing of financial obligations) for households, economic stimuli in the form of fiscal measures, and providing support for international development. As the index is based on a number of categorical indicators of a different nature, it is not possible to interpret which level of economic support would be adequate to protect workers against (for instance) income poverty or other adverse economic outcomes. Nonetheless, the index provides a comparative, albeit broad, indicator of government effort.

Figure 1. Global levels of economic support to workers affected by COVID-19, January 2020 to January 2021.

The black lines indicate the median level of economic support from January 2020 to January 2021. Globally, economic support was geared up just before April 2020 and the median level of support remained relatively constant since then in most regions (the exception being Africa). The median level of support reached a relatively high level early on, in the spring of 2020, with support in South America catching up over the summer. Support in Africa tended to be lower, and diminished during the last months of 2020. The grey intervals around the median indicate the range covered by the middle 50% of countries, showing that on all continents, clear differences exist in the level of economic support governments offer workers. Taken together, these data suggest that governments across the world provided economic support for workers affected by the economic consequences of COVID-19, but also that global and regional differences matter. There is substantial variation in the level of economic support between countries on different continents, as well as among countries in the same global region.

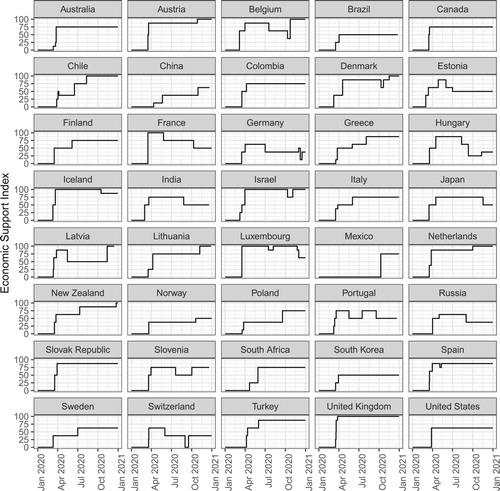

A closer look at individual countries helps to illustrate these variations. As shown in , most governments initiated their economic support around or just before April 2020, with Mexico being noticeably later. Beyond that similarity, however, substantial differences exist that may be relevant to workers’ (economic) well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. In particular, the maximum level of support provided to workers varies substantially, with for instance Austria, Chile, Iceland, and the United Kingdom (among other countries) reaching the highest scores on the index, with Norway, Sweden and Switzerland peaking at much more moderate levels. Moreover, the levels of government support vary across time, gradually increasing in for instance Greece, New Zealand, and Poland, but also showing declines in countries such as France, Estonia, and Hungary. Whether and how these varying levels of economic support affect workers’ wellbeing during this unprecedented pandemic remains an important empirical question for future research.

Figure 2. Economic support to workers affected by COVID-19, OECD and selected additional countries, January 2020 to January 2021.

While the economic support index in and offers key comparable information across countries, as the index was developed for cross-national comparability, it naturally leaves out country-specific details. Countries implemented measures specifically for parents, such as increased paid leave to parents whose young children cannot go to school (e.g. in the Czech Republic, Germany, Lithuania, Italy and Slovenia), or government guarantees on child support payments during the pandemic (e.g. in Austria and Belgium) (for an overview, see: Nieuwenhuis, Citation2020). Such economic support is just one factor of a complex set of community, work, and family structures in which workers are embedded.

Community

In the spring of 2020, we noted the significant risks facing vulnerable communities during the COVID-19 pandemic and warned against the potential increase in social inequality due to the scaling back of local services due to lockdown and social distancing measures. We noted particular vulnerabilities related to homelessness, disability, older age, or poor mental health. Local services in these areas play a crucial role in many communities. Access to disability and mental health services are of particular importance to workers’ wellbeing, yet to date, we know little about the impact of the pandemic on these services. Peer-reviewed evidence on what is happening with these services at the local level is only just emerging. Evidence from China suggests mental health services face challenges of addressing problems specifically related to the pandemic (e.g. psychosocial support for COVID patients and their families), but also opportunities, such as a growth in online psychological crisis interventions (Peng et al., Citation2020). Changes to communities and local service provision resulting from the pandemic also affect the professionals providing these services. A recent study on social services in Spain suggests community professionals, in particular social workers, feel overwhelmed by the context of the crisis and trying to adapt to this situation while offering effective services, leading to a worsening in their wellbeing (Muñoz-Moreno et al., Citation2020).

We also noted the potential for positive community developments in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. Volunteerism appears to be on the rise, with various efforts from civil society groups to help others within their community (see, e.g. Spear et al., Citation2020). On a larger scale, much of the support provided by the World Bank to counter COVID-19, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, was in the form of Community-driven development (CDD) programs. In contexts as varied as Indonesia,Footnote1 the Horn of Africa, and the Solomon Islands,Footnote2 such programs actively involve communities, local civic leaders, and local governments to provide large-scale assistance in ways that align with local needs.Footnote3 A critical voice was raised, however, that this approach overly favours the private sector in performing public functions (Dimakou et al., Citation2020). Similarly, Spear et al. (Citation2020) suggest that the rise in volunteerism goes hand-in-hand with the failure and/or inability of some governments to respond quickly or adequately enough to the current situation.

Work

The economic consequences of COVID-19 are widely expected to be the most detrimental to those who already had a more precarious position in (or outside) the labour market before the crisis hit. For instance, the OECD identifies ‘low-income households, children and young people, women, low-skilled workers, part-time or temporary workers, and the self-employed’Footnote4 as vulnerable groups in this context. In reviewing early empirical evidence below, we make a distinction between whether people from different vulnerable groups work, and if so, under which conditions people work – this includes wages, being able to work from home, but also the risk of exposure to COVID-19 while working.

The OECD estimates that the magnitude of job loss in relation to COVID-19 will far exceed that of the Great Recession of 2008 (OECD, Citation2020). Already at the onset of the crisis, large differences between countries were observed in the rates at which people lost their jobs. Relatively few people lost their jobs in countries that relied on job retention schemes (e.g. support to employers to cover wage costs), such as New Zealand, France, and the Czech Republic. Yet, these job retention schemes were found to offer less effective protection for workers on temporary contracts. Higher rates of job loss were found in countries that resorted to unemployment benefits to protect (former) workers’ incomes, such as Australia, Finland, Great Britain, and the United States. For those who lost their jobs, unemployment benefits provided the most important safety net, but this was found to be less effective for non-standard workers who typically did not have the contribution history necessary to be eligible for unemployment benefits.

Based on data that broadly covered the first wave of COVID-19, the OECD (Citation2020) observed that non-standard workers and self-employed workers were at the greatest risk to lose their job. This includes many young people who had yet to secure a stable position in, or had not yet entered, the labour market. In contrast to the Great Recession (at least with respect to its early phases: Karamessini & Rubery, Citation2014; Rubery, Citation2015), women were more likely to face economic consequences related to COVID-19 (Alon et al., Citation2020; OECD, Citation2020) – a finding we will nuance below. Low-paid workers on the one hand were more likely to lose their job (or part of their income). Single mothers were more likely to lose their job or income, as they are overrepresented in sectors that closed down (Blundell et al., Citation2020).

The economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic for workers in the Global South is particularly worrisome. In a December 2020 report, the International Labour Organisation (ILO) collated the sparse empirical evidence available from Least Developed Countries (LDC), estimating that upwards of 80–90 per cent of respondents in countries such as Bangladesh, Uganda, and Yemen have suffered significant losses to income and earnings (Parisotto & Elsheikhi, Citation2020). Current statistics tend to underestimate the effect of the pandemic in these areas given that some workers are forced to continue working, given high rates of informal work. The authors warn of potential scarring effects, with workers in LDC countries facing a greater risk of increased informality and long-lasting poverty.

While workers who lost their job (or part of their income) often faced financial challenges, others were required to work on location if they maintained their job – with the consequence that they faced greater risks of exposure to the COVID-19 virus. The related health risks were found to show a clear socio-economic gradient. Even in the relatively egalitarian Sweden, the lower educated, people with a low income, and people with a migration background from low- and middle-income countries (as well as men and people not married) were found to have a higher mortality risk from COVID-19 (Drefahl et al., Citation2020). People over the age of 70 were also found to have an increased risk of dying from COVID-19 if they lived together with someone of working age (<66 years) (Brandén et al., Citation2020), suggesting spill-over risks from exposure among workers. Focusing on specific frontline occupations, Billingsley et al. (Citation2020) found that bus and taxi drivers had a higher mortality-risk related to COVID-19, as did older individuals living with service workers, and that those differences in mortality were due to differences in socio-economic background. Migrants’ excess mortality risk is due in part to their disadvantaged socio-economic status, number of working-age household members and neighbourhood population density (Rostila et al., Citation2020), but appears to be unrelated to different levels of acculturation (Aradhya et al., Citation2020).

Family

The potential complexities for families raised by the COVID-19 pandemic are multiple: shifting and/or increasing inequalities related to gender and class, a potential for increases in domestic violence, food insecurity for children, increased risk of poverty (particularly for families affected by job loss), and problems resulting from unemployment (such as homelessness or negative family relationships). Due to space limitations, we focus here on gender inequality related to work and family, and the impact of school closures on children and families.

Early in 2020, we noted the challenges for work-family balance brought about by measures to slow the spread of COVID-19. On the one hand, scholars warned the pandemic would exacerbate gender inequalities, leading to an increase in women’s share of domestic labour (Landivar et al., Citation2020), and disproportionally challenging vulnerable families such as those headed by single mothers (Van Lancker & Nieuwenhuis, Citation2020). Empirical evidence suggests that mothers have generally seen a greater reduction in working hours and indeed have taken on a greater share of care tasks during lockdowns in countries across the globe (Collins et al., Citation2020; Craig & Churchill, Citation2020; Hipp & Bünning, Citation2020; Hjálmsdóttir & Bjarnadóttir, Citation2020; Kristal & Yaish, Citation2020; Yerkes et al., Citation2020). These shifts go hand-in-hand with an increase in women’s experienced ‘mental load’, stress, and perceived work pressure. Even in gender egalitarian countries like Iceland, mothers expressed being confronted with gender inequality in the private sphere, highlighted and exacerbated by the pandemic (Hjálmsdóttir & Bjarnadóttir, Citation2020). On the other hand, drawing on research suggesting men increasingly desire egalitarian relationships and greater involvement in their children’s lives (Petts et al., Citation2021), we suggested in April 2020 that the pandemic might provide an opportunity for fathers to be more involved in their children’s lives. The emerging evidence suggests that the impact of the pandemic on gender inequality within families has not been unequivocally negative. In countries like the Netherlands and the US, while mothers have taken on additional care and household tasks, some fathers have too (Petts et al., Citation2021; Yerkes et al., Citation2020). Thus, the potential for a decrease in gender inequality within families remains.

The impact of the pandemic on children within families is particularly worrisome. Already at an early stage during the pandemic, serious concerns were raised about the possible consequences of school closures for children and inequality. Evidence is now emerging that these concerns were very much warranted. The World Bank estimated in June 2020 that globally, more than one billion children could lose out on 30% to 90% of a full year of (quality adjusted) learning, and that groups vulnerable for more detrimental effects included girls, ethnic minorities and children with disabilities (Azevedo et al., Citation2020). Even in the Netherlands, which had a relatively short period of 8 weeks of school closures and a high level of digital preparedness, students in primary school on average experienced a learning loss equivalent to about 20% of a regular year of learning (Engzell et al., Citation2020). This was despite all efforts by parents, teachers and schools to provide home schooling. The learning loss was found to be 55% higher among children living in lower-educated families.

A sample of parents in the United States indicated to struggle with learner motivation, accessibility, and learning outcomes while home-schooling during school closures, as well as with balancing responsibilities – particularly among essential workers (Garbe et al., Citation2020). Single parents in particular struggle to combine paid work with unpaid care (Power, Citation2020), were found less likely to not have access to (adequate) internet and computers in the home (Mikolai et al., Citation2020), and are unable to spend more time on home schooling (Bayrakdar & Guveli, Citation2020). These struggles have contributed to reduced labor force participation, particularly for mothers (Petts et al., Citation2021). These findings clearly link the well-being and situation of workers during Covid-19 to that of their children.

Conclusion

When writing the Voices article last April 2020, we hoped, and maybe even assumed, that by now the pandemic would be over and the world would be back to normal. Clearly this was wishful thinking. Even once the pandemic is contained, its impact will continue to be felt by many communities, workers, and families for months and years to come. In particular, new inequalities are arising in the provision of local services within communities, affecting individuals dependent on these services and the professionals who provide them. By and large, the situation seems to evolve along the lines of the theory-informed concerns we raised before, emphasizing how COVID-19 exacerbates existing, well-understood inequalities. Those workers on the periphery of the labour market, including non-standard workers and the self-employed, but also women and low-paid workers, are experiencing significant losses in relation to work, working hours and/or wages. Workers in the informal economy are also being deeply affected in ways that often remain invisible. While opportunities exist in some countries for a decrease in gender inequality within families, in many countries, mothers are bearing the highest burden of school and childcare closures. Children, particularly those from low-income and/or lower-educated families, are facing the detrimental effects of school closures.

Our overview of the emerging evidence in relation to workers’ wellbeing suggests that many governments worldwide, although not all, are going to great lengths to contain a public health crisis and provide economic support to mitigate the effects of these public health measures. At the same time, such measures seem unable to prevent the critical shifts in inequalities across communities, at work, within families, and their intersections.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes on contributors

Rense Nieuwenhuis is associate professor in sociology at the Swedish Institute for Social Research (SOFI) at Stockholm University, and associated editor of Community, Work & Family.

Mara Yerkes is Associate Professor of Interdisciplinary Social Science at Utrecht University and joint editor of Community, Work & Family.

Notes

1 https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2020/06/01/community-led-responses-to-COVID-19-the-resilience-of-indonesia (last accessed 12 January 2021).

2 https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2020/05/19/community-responses-to-COVID-19-from-the-horn-of-africa-to-the-solomon-islands (last accessed 12 January 2021).

3 https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/communitydrivendevelopment (last accessed 12 January 2021).

4 https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/en/themes/social-challenges (last visited: 11 January 2021).

References

- Alon, T., Doepke, M., Olmstead-Rumsey, J., & Tertilt, M. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on gender equality. w26947. National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Aradhya, S., Brandén, M., Drefahl, S., Obućina, O., Andersson, G., Rostila, M., Mussino, E., & Juárez, S. P. (2020). Lack of acculturation does not explain excess COVID-19 mortality among immigrants. A population-based cohort study. 44. Department of Sociology - Demography Unit.

- Azevedo, J. P., Hasan, A., Goldemberg, D., Iqbal, S. A., & Geven, K. (2020). Simulating the potential impacts of COVID-19 school closures on schooling and learning outcomes: A set of global estimates. 9284. World Bank.

- Bayrakdar, S., & Guveli, A. (2020). Inequalities in home learning and schools’ provision of distance teaching during school closure of COVID-19 lockdown in the UK. Institute for social & economic research.

- Billingsley, S., Brandén, M., Aradhya, S., Drefahl, S., Andersson, G., & Mussino, E. (2020). Deaths in the frontline: Occupation-specific COVID-19 mortality risks in Sweden, 28.

- Blundell, R., Dias, M. C., Joyce, R., & Xu, X. (2020). COVID-19 and inequalities. Fiscal Studies, 41(2), 291–319. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-5890.12232

- Brandén, M., Aradhya, S., Kolk, M., Härkönen, J., Drefahl, S., Malmberg, B., Rostila, M., Cederström, A., Andersson, G., & Mussino, E. (2020). Residential context and COVID-19 mortality among adults aged 70 years and older in Stockholm: A population-based, observational study using individual-level data. The Lancet Healthy Longevity, 1(2), e80–e88. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2666-7568(20)30016-7

- Collins, C., Landivar, L. C., Ruppanner, L., & Scarborough, W. J. (2020). COVID-19 and the gender gap in work hours. Gender, Work & Organization. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12506.

- Craig, L., & Churchill, B. (2020). Dual-earner parent couples’ work and care during COVID-19. Gender, Work & Organization. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12497.

- Dimakou, O., Romero, M. J., & Van Waeyenberge, E. (2020). Never let a pandemic go to waste: Turbocharging the private sector for development at the world bank. Canadian Journal of Development Studies / Revue Canadienne d’études Du Développement, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/02255189.2020.1839394

- Drefahl, S., Wallace, M., Mussino, E., Aradhya, S., Kolk, M., Brandén, M., Malmberg, B., & Andersson, G. (2020). A population-based cohort study of socio-demographic risk factors for COVID-19 deaths in Sweden. Nature Communications, 11(1), 5097. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-18926-3 doi:10.1038/s41467-020-18926-3

- Engzell, P., Frey, A., & Verhagen, M. D. (2020). Learning inequality during the Covid-19 pandemic. Preprint. SocArXiv.

- Fisher, J., Languilaire, J.-C., Lawthom, R., Nieuwenhuis, R., Petts, R. J., Runswick-Cole, K., & Yerkes, M. A. (2020). Community, work, and family in times of COVID-19. Community, Work & Family, 23(3), 247–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2020.1756568

- Garbe, A., Ogurlu, U., Logan, N., & Cook, P. (2020). Parents’ experiences with remote education during COVID-19 school closures. American Journal of Qualitative Research, 4(3). https://doi.org/10.29333/ajqr/8471

- Hale, T., Webster, S., Petherick, A., Philips, T., & Kira, B. (2020). Oxford COVID-19 government response tracker. Blavatnik School of Government.

- Hipp, L., & Bünning, M. (2020). Parenthood as a driver of increased gender inequality during COVID-19? Exploratory evidence from Germany. European Societies, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2020.1833229

- Hjálmsdóttir, A., & Bjarnadóttir, V. S. (2020). “‘I have turned into a Foreman here at home’: Families and work–life balance in times of COVID-19 in a gender equality paradise. Gender, Work & Organization. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12552.

- Karamessini, M., & Rubery, J. (Eds.). (2014). Women and Austerity: The economic crisis and the future for gender equality. Routledge.

- Kristal, T., & Yaish, M. (2020). Does the coronavirus pandemic level the gender inequality curve? (It doesn’t). Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 68, 100520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2020.100520

- Landivar, L. C., Ruppanner, L., Scarborough, W. J., & Collins, C. (2020). Early signs indicate that COVID-19 is exacerbating gender inequality in the labor force. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 6, 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023120947997

- Mikolai, J., Keenan, K., & Kulu, H. (2020). Intersecting household level health and socio-economic vulnerabilities and the COVID-19 crisis: An analysis from the UK. SSM - Population Health, 12, 100628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100628 doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2020.100628

- Muñoz-Moreno, R., Chaves-Montero, A., Morilla-Luchena, A., & Vázquez-Aguado, O. (2020). “COVID-19 and social services in Spain” edited by A. M. Samy. PLOS ONE, 15(11), e0241538. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241538

- Nieuwenhuis, R. (2020). The situation of single parents in the EU. Study. PE 659.870. European Parliament’s Policy Department for Citizens’ Rights and Constitutional Affairs at the request of the FEMM Committee.

- OECD. (2020). OECD employment outlook 2020: Worker security and the COVID-19 crisis. OECD Publishing; Éditions OCDE.

- Parisotto, A., & Elsheikhi, A. (2020). COVID-19, jobs and the future of work in the LDCs: A (disheartening) preliminary account. 20. International Labour Organization.

- Peng, D., Wang, Z., & Xu, Y. (2020). Challenges and opportunities in mental health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. General Psychiatry, 33(5), e100275. https://doi.org/10.1136/gpsych-2020-100275

- Petts, R. J., Carlson, D. L., & Pepin, J. R. (2021). A gendered pandemic: Childcare, homeschooling, and parents’ employment during COVID-19. Gender, Work & Organization. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12614

- Power, K. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the care burden of women and families. Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy, 16(1), 67–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487733.2020.1776561

- Rostila, M., Cederström, A., Wallace, M., Brandén, M., Malmberg, B., & Andersson, G. (2020). Disparities in Covid-19 deaths by country of birth in Stockholm, Sweden: A total population based cohort study. 39. Department of Sociology - Demography Unit.

- Rubery, J. (2015). Austerity and the future for gender equality in Europe. ILR Review, 68(4), 715–741. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793915588892

- Spear, R., Erdi, G., Parker, M. A., & Anastasiadis, M. (2020). Innovations in citizen response to crises: Volunteerism & social mobilization during COVID-19, 9.

- Van Lancker, W., & Nieuwenhuis, R. (2020). Conclusion: The next decade of family policy research. In R. Nieuwenhuis, & W. Van Lancker (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of family policy (pp. 683–706). Springer International Publishing.

- Yerkes, M. A., André, S. C. H., Besamusca, J. W., Kruyen, P. M., Remery, C. L. H. S., van der Zwan, R., Beckers, D. G. J., & Geurts, S. A. E. (2020). “‘Intelligent’ lockdown, intelligent effects? Results from a survey on gender (in)equality in paid work, the division of childcare and household work, and quality of life among parents in the Netherlands during the Covid-19 lockdown” edited by S. Goli. PLOS ONE, 15(11), e0242249. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0242249