?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The present study explored the bidirectional and reciprocal nature of work-family guilt by testing a non-recursive model that treats work-family guilt as the mediator connecting the work-family interface. The sample was composed of 627 Chinese employees. The findings confirmed the reciprocal nature of work-family guilt (work-to-family and family-to-work guilt), which indicated that employees would not only have one form of guilt in the work-family interface. In addition, the findings revealed that time spent on work/family domains is indirectly related to work-family guilt via the increased work-family conflict and that there was a positive relationship between work-to-family guilt and work performance. As the first study investigating the bidirectional nature of work-family guilt, this study has refined and enriched our understanding of work-family guilt as well as contributed to future work-family interface, emotion, and performance studies.

Introduction

The guilty feeling emerging from failing to balance work and family domains (work-family guilt) is quite a subject of interest in social media and organisational behaviour literature (Korabik, Citation2014). Its association with work-family conflict (a form of inter-role conflict between work and family domains, see Lu & Cooper, Citation2015) (Korabik et al., Citation2017) and negative impact on individuals such as, a decrease in job satisfaction (Zhang et al., Citation2019), life satisfaction (Gomez-Ortiz & Roldan-Barrios, Citation2021), work performance (Morgan & King, Citation2012), and work hours (Aarntzen et al., Citation2019), have informed the need to investigate such a phenomenon further.

According to Livingston and Judge (Citation2008), work-family guilt can be defined as the sense of guilt generated from employees believing they failed to fulfil their work/family roles due to the other role’s demands. Following this definition, several studies argued that work-family guilt might share similarities with the work-family conflict, being that work-family guilt might also have two dimensions: work-to-family guilt and family-to-work guilt, and that work-to-family conflict (work interference with family) is related to work-to-family guilt, whereas family-to-work conflict (family interference with work) is associated with family-to-work guilt (e.g., Livingston & Judge, Citation2008; Korabik, Citation2014; Korabik et al., Citation2017). For example, the overwhelming work demands might cause the employees to break promises to their family members (Work-to-family conflict), such as missing the child’s birthday, thereby creating a sense of work-to-family guilt.

Despite the acknowledgement of the similarity between the structural conceptualisation of work-family guilt and work-family conflict, most of the work-family guilt studies focused on the general guilt being the negative outcome of the work-family conflict (Korabik et al., Citation2017) and that only the predictive relation between work-family conflict and its within-domain guilt has been studied (e.g., work-to-family conflict predicts work-to-family guilt) (e.g., Livingston & Judge, Citation2008; Goncalves et al., Citation2018; Gomez-Ortiz & Roldan-Barrios, Citation2021). One question arises from this similar structure between work-family guilt and work-family conflict: hypothetically, if work-family guilt shares a similar theoretical structure with work-family conflict, does that mean similar to work-family conflict, work-family guilt is also reciprocal (work-to-family guilt influences the level of family-to-work guilt and vice versa), when considering it as the mediator connecting the work-family interface? Yet, in our literature review, no study has explored/investigated the bidirectional relationship between work-to-family guilt and family-to-work guilt, and only a few studies investigated the mediating effect of work-family guilt in the relationship between work-family conflict and its outcomes, such as work-family guilt mediating the relationships between work-family conflict and job/life satisfaction (e.g., Zhang et al., Citation2019; Sousa et al., Citation2020).

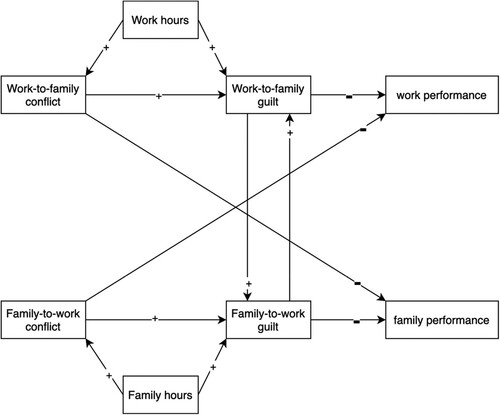

Hence, to confirm whether work-to-family and family-to-work guilt are reciprocal, this study aims to develop and test a non-recursive model that includes work-family conflict, work-family guilt, time spent on work/family domains, and work/family-related performance in a Chinese sample. This proposed model () is based on several theories and previous studies; due to the complexity of the work-family interface, this might not be simply explained by one single theory (Bellavia & Frone, Citation2005).

Specifically, the scarcity theory, which explains that using too many personal resources in one role would affect the available resources for the other role (Chen et al., Citation2020), is used to explain the time-conflict and time-guilt relationships. The source attribution and emotional exhaustion perspectives are used to explain the mediating effect of work-family guilt in the relationships between work-family conflict and within-domain performance. Attribution theory posits that a specific event can determine emotions and thereby influence behaviours (O'Shea et al., Citation2021). This is because individuals might attribute blame to a specific event that causes the negative emotion, and managing the negative emotion might exhaust the individual, thereby affecting their behaviours (e.g., Zhang et al., Citation2019; Zheng et al., Citation2021); for example, Morgan and King found that work-family guilt (an emotion) mediated the relationship between work-family conflict (a specific event) and work performance (work behaviours), and Chen et al. (Citation2022) found that the guilty feeling generated from work-family conflict would affect individuals’ family engagement (family behaviours). Last, the spillover theory, which explains that involvement in one domain might negatively impact participation in the other domain and argues that negative feelings (e.g., guilt) in one role would spill over to the other role (Li & Ilies, Citation2018), is used to explore the reciprocal nature of work-family guilt.

There are several reasons why this study chooses to be conducted in China. First, Chinese samples are fitting for exploring work/family-related issues due to the workplace conditions, such as long working hours, greater performance pressure, and substantial workload (e.g., Zhang et al., Citation2019; Zhao et al., Citation2019). Second, as the country with the most working population in the world, it would be informative and beneficial to conduct work-family research by using Chinese samples, to extend our understanding of the phenomenon of interest outside the overwhelming Western perspective in the field of work-family research (e.g., Tang et al., Citation2014; Lu & Cooper, Citation2015).

Lastly, the conflict between work/family values in China; for example, prioritising work because it creates wealth for the family (Zhang et al., Citation2012) meanwhile also highly value the importance of family, such as sacrificing job opportunities to fulfil family needs (Zhang et al., Citation2020), have contributed to a more substantial level of work-family guilt experienced in China. This was evident in a project that involved over 3,000 participants across ten different countries (Korabik et al., Citation2017); this project found that the mean level of work-family guilt was different between countries in that the collectivistic Asian (i.e., Chinese) showed a greater level of both work-to-family guilt and family-to-work guilt than the individualistic Anglo (Korabik et al., Citation2017). Thus, China provides a great platform for studying work-family guilt, and it is hoped to provide valuable information for future work-family interface studies.

Hypothesises development

Time spent on work/family domains, work-family conflict, and work-family guilt

The relationship between time spent on work/family domains and work-family conflict has been well studied; for example, the scarcity theory posits that individuals only have a finite amount of time and energy; therefore, more time spent on one domain might decrease the time available in the other domain, thereby leading to the experience of work-family conflict (Burch, Citation2020). Following the scarcity theory and Livingston and Judge’s (2008) definition of work-family guilt, we expect that more time spent in one domain may increase its corresponding sense of guilt. For example, working long hours might simply mean that the employee has less available time with their family members, thereby creating/increasing work-to-family guilt directly (Gomez-Ortiz & Roldan-Barrios, Citation2021). Thus, we propose:

Hypothesis 1: Work hours are positively related to work-to-family conflict (H1a) and work-to-family guilt (H1b).

Hypothesis 2: Time spent on family responsibilities is positively related to family-to-work conflict (H2a) and family-to-work guilt (H2b).

The Mediating role of work-family guilt

Previous studies found that work-family conflict is positively related to guilt (emotional distress), and that the conflict-guilt situation might influence employees’ performance (e.g., Livingston & Judge, Citation2008; Zhang et al., Citation2019; Morgan & King, Citation2012). This can be explained by the source attribution and emotional exhaustion perspectives, which argue that the experience of work-family conflict might affect the within-domain individual’s outcomes since the individual might psychologically/cognitively attribute blame to the domain that causes the conflict-based experience, and that managing negative emotion (e.g., guilt) could burnout the individual due to emotional exhaustion, thereby affecting their performance (e.g., Zhang et al., Citation2019; Zheng et al., Citation2021). For example, missing children’s birthdays due to work demands (work-to-family conflict) might make the parents feel work-to-family guilt, thereby blaming the sources that created the conflict-guilt experience; simultaneously, feeling of work-to-family guilt might exhaust the individual and affect their work performance. This also applies to the other direction; for example, slowing down the process of a group project due to family emergencies (family-to-work conflict) might cause employees to feel family-to-work guilt, and affect employees’ family performance due to emotional exhaustion. Thus, we propose:

Hypothesis 3: Work-family guilt mediates the relationship between work-family conflict and within-domain performance in which work-to-family conflict is negatively related to work performance via increased work-to-family guilt (H3a), whereas family-to-work conflict is negatively related to family performance via increased family-to-work guilt (H3b).

Hypothesis 4: Work-to-family and family-to-work guilt are bidirectional and reciprocal in that work-to-family conflict are positively related to family-to-work guilt via increased work-to-family guilt (H4a), whereas family-to-work conflict is positively related to work-to-family guilt via increased family-to-work guilt (H4b).

Hypothesis 5: Work-family conflict is related to domain-specific performance in which work-to-family conflict is negatively related to family performance (H5a), whereas family-to-work conflict is negatively related to work performance (H5b).

Methods

Participants and procedure

All participants met the following 4 recruitment requirements: 1) Over 18 years old; 2) Chinese nationality, i.e., grew up and currently living in China; 3) Have a job; 4) Have a family (i.e., spouse, partner, children, relatives, or/have parents). A total of 696 Chinese employees voluntarily participated in this study, sixty-nine participants were deleted due to missing data and providing unrealistic answers (e.g., spending more than 24 hours on family responsibilities per day). The participants are not limited to any industries or business sectors in order to generate a broad representation of the working population of China. Moreover, the mean age of the remaining 627 participants (male = 320, female = 307) was 33.90 years old, ranging from 18 to 74 years old (SD = 9.21); on average, they worked 40.04 (SD = 16.39) hours per week and spent 1.15 hours (SD = 5.80) on eldercare and 36.16 (SD = 38.21) minutes on domestic chores per day. Furthermore, among the 392 parent participants, 292 parent participants have one child, ninety-one parent participants have 2 children, and 9 parent participants have 3 or more children; the parent participants in this study reported that they on average, spent 2.09 (SD = 2.67) hours on childcare per day.

An online questionnaire via Wenjuanxing, a well-known Chinese online questionnaire survey tool, was used to collect the data. A snowball sampling technique was used to recruit the participants for this study. After receiving the ethics approval from the host institution’s ethics committee, the researcher posted and shared the recruitment letter with the online questionnaire link on WeChat, Weibo, and QQ, which are all mainstream social media platforms in China. The data collection period lasted for three months from Jun 2021 to Sep 2021.

Measures

All measures used in this study were translated into Chinese by the researcher and back-translated by professional translators who speak both languages fluently.

Work-family conflict. A 5-point Likert scale measured work-family conflict ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) developed by Matthews et al. (Citation2010). This scale has 6 items, of which 3 items were used to measure work-to-family conflict (e.g., ‘I have to miss family activities due to the amount of time I must spend on work responsibilities’) and 3 items for family-to-work conflict (e.g., ‘because I am often stressed from family responsibilities, I have a hard time concentrating on my work’). The Cronbach’s Alpha of this measure was .75 for work-to-family conflict and .67 for family-to-work conflict.

Work-Family guilt. A 5-point Likert scale measuring work-family guilt ranges from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), adopted from Morgan and King (Citation2012). A total of 10 items, of which 5 items were used to measure work-to-family guilt (e.g., ‘I feel guilty when the demands of my work interfere with my home and family life’), whereas 5 items were used for measuring family-to-work guilt (e.g., ‘I feel guilty when things I want to do at work don’t get done because of the demands of my family or spouse/partner’). The Cronbach’s Alpha of this measure was .90 for both work-to-family guilt and family-to-work guilt.

Work hours. The participants were asked to write down their work hours per week.

Time spent on family responsibilities. The participants were asked to write down how many hours they spent on childcare and eldercare per day, and how many minutes they spent on domestic chores per day, respectively. Moreover, minutes spent on domestic chores per day were converted into hours spent on domestic chores per day. Furthermore, hours spent on childcare, eldercare, and domestic chores were summed up to represent the total time spent on family responsibilities.

Work performance. Andrade et al.’s (Citation2020) Self-Assessment Scale of Job Performance measured work performance. A total of 10 items (e.g., ‘I work hard to do the tasks designated to me’.) were rated on a 5-points Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). The Cronbach’s Alpha of this measure was .88.

Family performance. Family performance was measured by Chen et al.’s (Citation2014) Family Role Performance Scale. This scale has 8 items (e.g., Complete household responsibilities’) ranging from 1 (do not fulfil expectation at all) to 5 (fulfil expectation completely). The Cronbach’s Alpha of this measure was .86.

Ethical considerations

The present study has been approved by the host institution’s ethics committee. To ensure anonymity, participants were given an ID code instead of their names, and no identifiable information (e.g., IP address, contact number, company name, etc.) was collected during questionnaire completion. In addition, the researcher adhered to the British Psychological Society (BPS) Code of Human Research Ethics (British Psychological Society, Citation2014), the BPS code of Ethics and Conduct (British Psychological Society, Citation2018), and the BPS Ethics Guidelines for Internet-Mediated Research (British Psychological Society, Citation2017).

Path analysis

The proposed model in this study was tested using Lavaan, an R package for structural equation modelling in R software (Rosseel, Citation2012). Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was first used to evaluate the measurement construct. In addition, identification highlights whether there is enough information to generate the parameter estimate; therefore, the model needs to be identified before estimating a structural equation model (Byrne, Citation2016). The results from Lavaan indicated that the proposed model is identified.

Moreover, Byrne (Citation2016) argued that model evaluation should at least use two different fit indices. Hence, the present study used the comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and the standardised root mean square residual (SRMR) to evaluate the model fit. The criterion for a good-fitting model is CFI greater than .90; RMSEA less than .05; and SRMR less than .08, respectively (Byrne, Citation2016).

Results

Descriptive statistics

The mean, standard deviation and correlation of the variables are shown in . In general, almost all hypothesised relationships were significantly correlated.

Table 1. Mean, standard deviation, and correlation of the variables (n = 627).

Confirmatory factor analysis and overall model fit

A confirmatory measurement model of 6 constructs and 34 items (excluding the construct of time spent on work/family domains) was tested using Lavaan. The results of the CFA fitting index (CFI = .94; RMSEA = .04; SRMR = .04) indicated that the measurement model was good-fitting to the data (see ). Moreover, all factor loadings were significant at p < .001 and positively ranging from .377 to .995. Hence, no factors needed to be removed (Brown & Moore, Citation2012).

Table 2. Goodness-of-fit of the measurement of the proposed model.

Furthermore, the model fit indices (CFI = .91; RMSEA = .05; SRMR = .07) indicated that the proposed model was good-fitting to the data (see ).

Table 3. Goodness-of-fit of the proposed model.

Parameter estimates

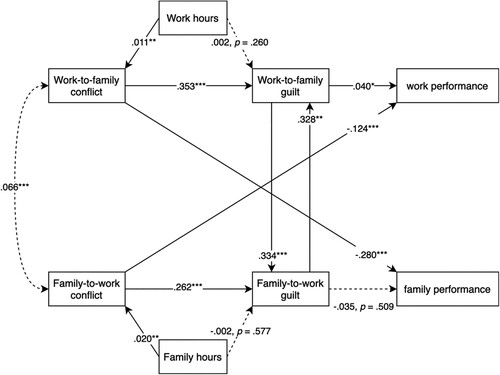

The final model with the parameter estimates and significance level is presented in . summarises the parameter estimates and covariance between latent variables to facilitate reading.

Figure 2. Final model with the regression coefficients labelled for each path.

Note. Broken lines represent non-significant paths, the curved line represents the covariance, * p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

Table 4. Summary of the parameter estimates and covariance of the latent variables.

Both H1 and H2 are partially supported; work hours are positively related to work-to-family conflict (H1a) (β = .01, p < .01), and time spent on family responsibilities is positively related to family-to-work conflict (H2a) (β = .02, p < .01), respectively. Nevertheless, the broken lines (see ) between work hours and work-to-family guilt (H1b) and between time spent on family responsibilities and family-to-work guilt (H2b) indicated that there were no significant relationships between these variables, respectively.

Moreover, H3 is not supported; the results indicated that work-to-family conflict is positively related to work-to-family guilt (β = .4, p < .01) and work-to-family guilt is positively related to work performance (β = .04, p = .04), showing a positive indirect effect from work-to-family conflict to work performance via work-to-family guilt. In addition, the broken link between family-to-work guilt and family performance indicated that family-to-work guilt is not related to family performance; thus, no mediation is found between family-to-work conflict and family performance via family-to-work guilt.

Furthermore, H4 is supported; the results indicated that work-to-family conflict is positively related to work-to-family guilt (β = .4, p < .01) and work-to-family guilt is positively related to family-to-work guilt (β = .3, p < .01), showing a positive indirect effect from work-to-family conflict to family-to-work guilt via work-to-family guilt (H4a). In addition, the results indicated that family-to-work conflict is positively related to family-to-work guilt (β = .3, p < .01) and family-to-work guilt is positively related to work-to-family guilt (β = .3, p < .01), showing a positive indirect effect from family-to-work conflict to work-to-family guilt via family-to-work guilt (H4b).

Lastly, as expected, H5 is supported; work-to-family conflict is negatively related to family performance (β = −.28, p < .01) and family-to-work conflict is negatively related to work performance (β = −.12, p < .01).

Discussion

The priority of this study is to explore the reciprocal nature of work-family guilt and the results supported this hypothesis (H4). Specifically, similar to the bidirectional and reciprocal nature of work-family conflict (Lu & Cooper, Citation2015), the bidirectional nature of work-family guilt indicates that work-family guilt comes in two directional dimensions: work-to-family and family-to-work guilt. In addition, the reciprocal nature of work-family guilt demonstrated that employees would not only feel one form of work-family guilt; for example, the feeling of work-to-family guilt would spill over to the family role, eliciting and/or stimulating family-to-work guilt and vice versa.

Moreover, inconsistent with Gomez-Ortiz and Roldan-Barrios’s (Citation2021) study which found that time allocation between work and family domains is directly related to the sense of guilt. This study found that work hours and time spent on family responsibilities are only related to work-to-family and family-to-work guilt when spending time in one domain creates a conflict experience (e.g., work hours are indirectly related to work-to-family guilt via work-to-family conflict).

However, this finding might be influenced by the work value and family collectivism orientation in China. When employees believe that work is for the family benefit (work value), they might deem hard work (e.g., working long hours) is being beneficial for their family (e.g., Zhang et al., Citation2019; Holt & Keats, Citation1992); hence, no direct relationship between work hours and a sense of guilt towards family was found. On the other hand, the family collectivism orientation emphasises the importance of family and fulfilling the family obligation (e.g., Adams, Citation2005; Zhang et al., Citation2020), which could make the employees not feel family-to-work guilt when spending more time on the family because it is considered as fulfilling their obligation towards family members.

Furthermore, the present study found that work-family conflict was negatively related to domain-specific performance (e.g., work-to-family conflict is negatively related to family performance) (e.g., Ahmad, Citation2008; Efeoglu & Ozcan, Citation2013). Nevertheless, the present study found that work-to-family guilt is positively related to work performance, and no relationship between family-to-work guilt and family performance is found. Though inconsistent with the hypothesises, it is reasonable when considering that a sense of guilt might also have a pro-social effect (Morgan & King, Citation2012) as well as the cultural background in China.

Morgan and King (Citation2012) found that the feeling of family-to-work guilt might motivate employees to perform organisational citizenship behaviours as compensation (work behaviours that are beneficial to the organisation, see Organ, Citation1997). For example, when an employee comes to work late due to the need of family (e.g., taking care of an ill child), the guilty feeling of having wronged the organisation (family-to-work guilt) might motivate the employee to comply with the demand of the organisation/supervisor, resulting in positive work outcomes (e.g., increase work performance). Following this standpoint and with the cultural background in China, such as the need of the group should be prioritised over the self (e.g., Adams, Citation2005; Billing et al., Citation2014), and the Chinese work value emphasises that hardworking should be honoured (Huang & Jin, Citation2019). It is plausible that when experiencing work-to-family guilt, instead of performing counterproductive work behaviours, the employee might try to complete the work task quicker by increasing work performance (e.g., increasing work productivity), so that they can make time for their family, without wronging the need of the organisation.

Nevertheless, we cannot omit that the positive relationship between work-to-family guilt and work performance might be influenced by the linkage between work-to-family and family-to-work guilt in the proposed model. In other words, similar to the findings of Morgan and King (Citation2012), the present study found that family-to-work guilt motivated employees to perform better at work, and that the effect of family-to-work guilt on work performance is not straightforward but via the increased work-to-family guilt, due to the reciprocal nature of work-family guilt. However, more studies are needed to verify these relations further.

Implications of this study

Previous work-family research almost exclusively focused on work-family conflict and work-family enrichment as the mediators between work and family domains. Our findings explain how work-family guilt acts as the mediator that connects the work-family interface, providing a different angle to help better understand the complicated work-family interface. In addition, similar to the development of the concept of work-family conflict (from being only defined as a role conflict, to discovering the bidirectional and reciprocal nature, see Lu & Cooper, Citation2015), as the first study to examine the reciprocal nature of work-family guilt, confirming the reciprocal nature of work-family guilt enriched our understanding by improving its structural conceptualisation, which will help inform future work-family guilt research, and provides research direction for future work-family guilt scholars.

The findings also have practical implications since our model demonstrates the association between work-family conflict and work-family guilt, the negative impact of work-family conflict on both work and family performance, and previous studies have found that both work-family conflict and guilt would affect employees’ wellbeing, such as a decrease in job satisfaction (Zhang et al., Citation2019; Sousa et al., Citation2020).

Thus, based on the findings of our model, it could be helpful to prevent the decrease in work/family-related performance by minimising the experience of time-related work-family conflict (e.g., work hours lead to work-to-family conflict). Organisations could promote access to flexibility, such as providing employees with flexible work hours and places of work, since previous studies have repeatedly confirmed the beneficial effect of work flexibility in managing time-related work-family conflict (e.g., Piszczek & Pimputkar, Citation2020; Choo et al., Citation2016).

Moreover, given that our model finds the relationship between work-family conflict and guilt, and the reciprocal nature of work-family guilt, it could be helpful to introduce and promote cognitive emotion regulation intervention, such as the cognitive reappraisal approach, to help workers adjust their negative emotional responses (e.g., work-family guilt) to stressful events (e.g., work-family conflict) (Wu et al., Citation2019). In addition, emotional support from supervisors and/or organisations, as one type of job resource, might be effective in managing the reciprocal nature of work-family guilt by increasing workers’ personal resources, if the reciprocal nature of work-family guilt is due to the depletion mechanism in the work-family interface (managing work-to-family guilt depleted the limited personal resource to manage family-related emotion, thereby increasing the risk of feeling family-to-work guilt). However, more studies are needed to test the reciprocal nature of work-family guilt and the effect of emotional support on managing the spillover effect of work-family guilt.

Limitations and recommendations

Although structural equation models are able to support causal inference (e.g., Przybyla et al., Citation2018; Maydeu-Olivares et al., Citation2020), the cross-sectional design of this study impedes causal assumption. Thus, a longitudinal study is recommended. In addition, the use of online questionnaires might also limit the sample to a sub-group of people who have access to the internet, thereby increasing the self-selection bias and affecting the generalisability of the findings (Andrade et al., Citation2020). Moreover, the use of self-reported data could also increase the response and measure bias (Parry et al., Citation2021).

Moreover, China provides a great platform to conduct work-family research due to the workplace's intensity and the working population’s size (e.g., Zhao et al., Citation2019; Lu & Cooper, Citation2015). However, as discussed, the Chinese cultural background, such as the family collectivism orientation, might influence this study’s findings; hence, the findings of this study might be only applicable to China or other Confucian heritage countries in Asia (e.g., Korea, Singapore, Japan) since these countries share similar work/family values (Phuong-Mai et al., Citation2005). Thus, it is recommended that future studies can adopt the present study’s proposed model and test it in other individualistic countries, by comparing the difference in the findings to further enrich our understanding of the process of work-family guilt and how culture might impact the sense of work-family guilt.

Furthermore, our study responds to the call from Zhang et al. (Citation2019), which encouraged future studies to investigate how work-family guilt may impact employees’ behavioural outcomes. However, this study did not investigate how work-family guilt might influence employees’ psychological well-being. Thus, it is recommended that future research should examine if work-family guilt influences other individuals’ outcomes, such as how work-family guilt may affect the level of work or family strain. In addition, other variables that might create a sense of guilt should also be explored, considered, and tested as the antecedents of work-family guilt to extend our understanding of the experience of work-family guilt.

Conclusion

The present study explored the reciprocal relationship between work-to-family and family-to-work guilt by using work-family guilt as the mediator connecting the work-family interface. The findings suggest that work-family guilt could be reciprocal, guilty feeling in one domain (e.g., work-to-family guilt) would elicit and/or stimulate the guilty feeling in the other domain (e.g., family-to-work guilt). In addition, time spent in work/family domains is only related to work-family guilt, when it creates the work-family conflict experience, and that work-family guilt might potentially increase work performance. This study enriches and refines our understanding of work-family guilt and provides a different perspective for future work-family researchers investigating the work-family interface.

Statements and declarations

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Shujie Chen

Shujie Chen is a PhD candidate majoring in occupational psychology at De Montfort University. His research has included work-life balance, especially in work-family conflict and work-family guilt. He has one publication titled “Developing and testing an integrative model of work-family conflict in a Chinese context”, one paper in the revision process, and two papers in the reviewing process.

Mei-I Cheng

Dr Mei-I Cheng has researched widely in the field of competency and behavioural change within project and organizational contexts. Her research has included collaborative work with a range of construction and aerospace firms exploring innovative ways of enhancing individual and team performance amongst professional and managerial workers. Her research papers have won awards, including a special ‘Citation of Excellence’ award, the highest award that Emerald bestows and Gold Medal – Winner of Innovation Award by The Chartered Institute of Building.

References

- Aarntzen, L., Derks, B., van Steenbergen, E., Ryan, M., & van der Lippe, T. (2019). Work-family guilt as a straightjacket. An interview and diary study on consequences of mothers’ work-family guilt. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 115, 103336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.103336

- Adams, G. (2005). The cultural grounding of personal relationship: Enemyship in North American and West African worlds. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(6), 948–968. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.6.948

- Ahmad, A. (2008). Direct and indirect effects of work-family conflict on job performance. The Journal of International Management Studies, 3(2), 176–180. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260294197_Direct_and_Indirect_Effects_of_Work-Family_Conflict_on_Job_Performance.

- Andrade, E. G. S. D. A., Queiroga, F., & Valentini, F. (2020). Short version of self-assessment scale of job performance. Annals of Psychology, 36(3), 543–552. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.402661

- Andrade, E. G. S. D. A., Queiroga, F., & Valentini, F. (2020). Short version of self-assessment scale of job performance. Annals of Psychology, 36(3), 543–552. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.402661

- Bellavia, G., & Frone, M. (2005). Work-family conflict. In J. Barling, E. K. Kelloway, & M. Frone (Eds.), Handbook of Work Stress (pp. 185–221). Sage Publications.

- Billing, T. K., Bhagat, R., Babakus, E., Srivastatva, B. N., Shin, M., & Brew, F. (2014). Work-family conflict in four national contexts: A closer look at the role of individualism-collectivism. International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management, 14(2), 139–159. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595813502780

- British Psychological Society. (2014). BPS code of Human Research Ethics. https://www.bps.org.uk/news-and-policy/bps-code-human-research-ethics-2nd-edition-2014.

- British Psychological Society. (2017). BPS Ethics Guidelines for Internet-Mediated Research. https://www.bps.org.uk/sites/beta.bps.org.uk/files/Policy%20-%20Files/Ethics%20Guidelines%20for%20Internet-mediated%20Research%20%282017%29.pdf.

- British Psychological Society. (2018). BPS code of Ethics and Conduct. https://www.bps.org.uk/node/1714.

- Brown, T. A., & Moore, M. T. (2012). Confirmatory factor analysis. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Handbook of structural equation modeling (pp. 361–379). The Guilford Press.

- Burch, T. (2020). All in the family: the link between couple-level work-family conflict and family satisfaction and its impact on the composition of the family over time. Journal of Business and Psychology, 35(5), 593–607. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-019-09641-y

- Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural Equation Modelling with Amos: Basic Concepts, Applications, and Programming (3rd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315757421

- Chen, C., Zhang, Z., & Jia, M. (2020). Effect of stretch goals on work-family conflict: Role of resource scarcity and employee paradox mindset. Chinese Management Studies, 14(3), 737–749. https://doi.org/10.1108/CMS-06-2019-0240

- Chen, Y. P., Shaffer, M., Westman, M., Chen, S., Lazarova, M., & Reiche, S. (2014). Family role performance: Scale development and validation. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 63(1), 190–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12005

- Chen, Z., Promislo, M. D., Powell, G. N., & Allen, T. D. (2022). Examining the aftermath of work-family conflict episodes: Internal attributions, self-conscious emotions, family engagement, and well-being. Psychological Reports, https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941221144609

- Choo, J. L. M., Desa, N. M., & Asaari, M. H. A. H. (2016). Flexible working arrangement toward organizational commitment and work-family conflict. Studies in Asian Social Science, 3(1), 21–36. https://doi.org/10.5430/sass.v3n1p21

- Efeoglu, I. E., & Ozcan, S. (2013). Work-family conflict and its association with job performance and family satisfaction among physicians. Australian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences, 7(7), 43–48. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277476459_Work-Family_Conflict_and_Its_Association_with_Job_Performance_and_Family_Satisfaction_among_Physicians.

- Frone, M. R., Russell, M., & Cooper, M. L. (1992). Antecedents and outcomes of work-family conflict: Testing a model of the work-family interface. Journal of Applied Psychology, 77(1), 65–78. https://doi.org/10.1037//0021-9010.77.1.65

- Gomez-Ortiz, O., & Roldan-Barrios, A. (2021). Work-family guilt in Spanish parents: Analysis of the measurement, antecedents and outcomes from a gender perspective. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(15), 8229. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18158229

- Goncalves, G., Sousa, C., Santos, J., Silva, T., & Korabik, K. (2018). Portuguese mothers and fathers share similar levels of work-family guilt according to a newly validated measure. Sex Roles, 78(3-4), 194–207. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0782-7

- Holt, J., & Keats, D. M. (1992). Work cognitions in multicultural interaction. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 23(4), 421. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022192234001

- Huang, S. Y., & Jin, Z. H. (2019). Research on the management of enterprises’ overtime culture and employee’s wellbeing. Commercial Science Research, 6, 102–114.

- Korabik, K. (2014). The intersection of gender and work-family guilt. In M. Mills (Ed.), Gender and the Work-Family Experience (pp. 141–157). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-08891-4_8

- Korabik, K., Aycan, Z., & Ayman, R.2017). The work-family interface in global context. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Li, X., & Ilies, R. (2018). Affective processes in the work-family interface: Global considerations. In K. M. Shockley, W. Shen, & R. C. Johnson (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of the global work–family interface (pp. 661–680). Cambridge University Press.

- Livingston, B. A., & Judge, T. A. (2008). Emotional responses to work-family conflict: An examination of gender role orientation among working men and women. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93(1), 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.93.1.207

- Lu, L., & Cooper, C. L. (2015). Handbook of research on work-life balance in Asia. Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781783475094

- Matthews, R. A., Kath, L. M., & Barnes-Farrell, J. (2010). A short, valid, predictive measure of work–family conflict: Item selection and scale validation. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15(1), 75–90. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017443

- Maydeu-Olivares, A., Shi, D., & Fairchild, A. J. (2020). Estimating causal effects in linear regression models with observational data: The instrumental variables regression model. Psychological methods, 25(2), 243–258. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000226

- Morgan, W. B., & King, E. B. (2012). The association between work-family guilt and pro- and anti-social work behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 68(4), 684–703. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2012.01771.x

- Organ, D. W. (1997). Organizational citizenship behavior: It's construct clean-up time. Human Performance, 10(2), 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327043hup1002_2

- O'Shea, D., Barkoukis, V., McIntyre, T., Loukovitis, A., Gomez, C., Moritzer, S., Michaelides, M., & Theodorou, N. (2021). Who's to blame? The role of power and attributions in susceptibility to match-fixing. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 55, 101955. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2021.101955

- Parry, D. A., Davidson, B. I., Sewall, C. J. R., Fisher, J. T., Mieczkowski, H., & Quintana, D. S. (2021). A systematic review and meta-analysis of discrepancies between logged and self-reported digital media use. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(11), 1535–1547. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01117-5

- Phuong-Mai, N., Terlouw, C., & Pilot, A. (2005). Cooperative learning vs Confucian heritage culture’s collectivism: Confrontation to reveal some cultural conflicts and mismatch. Asian Europe Journal, 3(3), 403–419. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10308-005-0008-4

- Piszczek, M. M., & Pimputkar, A. S. (2020). Flexible schedules across working lives: Age-specific effects on well-being and work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 106, 12. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000844

- Przybyla, J., Geldhof, G. J., Smit, E., & Kile, M. L. (2018). A cross sectional study of urinary phthalates, phenols and perchlorate on thyroid hormones in US adults using structural equation models (NHANES 2007-2008). Environmental research, 163, 26–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2018.01.039

- Rastogi, R., Agarwal, S., & Garg, P. (2019). Testing the reciprocal relationship between quality of work life and subjective well-being: a path analysis model. International Journal of Project Organisation and Management, 11(2), 140–153. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPOM.2019.10022103

- Riana, I. G., Wiagustini, N. L. P., Dwijayanti, K. I., & Rihayana, I. G. (2018). Managing work-family conflict and work stress through job satisfaction and impact on employee performance. Journal Teknik Industri, 20(2), 127–134. https://doi.org/10.9744/jti.20.2.127-134

- Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

- Roth, L., & David, E. M. (2009). Work-family conflicts and work performance. Psychological Reports, 105(1), 80–86. https://doi.org/10.2466/PR0.105.1.80-86

- Sousa, C., Pinto, E., Santos, J., & Goncalves, G. (2020). Effects of work-family and family-work conflict and guilt on job and life satisfaction. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 51(4), 305–314. https://doi.org/10.24425/ppb.2020.135463

- Tang, S., Siu, O-L, & Cheung, F. (2014). A study of work–family enrichment among Chinese employees: The mediating role between work support and job satisfaction. Applied Psychology: An International Review, 63(1), 130–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2012.00519.x

- Wu, T.-J., Yuan, K.-S., Yen, D. C., & Xu, T. (2019). Building up resources in the relationship between work-family conflict and burnout among firefighters: Moderators of guanxi and emotion regulation strategies. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 28(3), 430–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2019.1596081

- Zhang, M., Griffeth, R. W., & Fried, D. D. (2012). Work-family conflict and individual consequences. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 27(7), 696–713. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941211259520

- Zhang, M., Zhao, K., & Korabik, K. (2019). Does work-to-family guilt mediate the relationship between work-to-family conflict and job satisfaction? Testing the moderating roles of segmentation preference and family collectivism orientation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 115, 103321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2019.103321

- Zhang, M. Y., Lin, T., Wang, D. H., & Jiao, W. (2020). Filial piety dilemma solutions in Chinese adult children: The role of contextual theme, filial piety beliefs, and generation. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 23(2), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12395

- Zhao, K., Zhang, M., & Foley, S. (2019). Testing two mechanisms linking work-to-family conflict to individual consequences: Do gender and gender role orientation make a difference? The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(6), 988–1009. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2017.1282534

- Zheng, J., Gou, X., Li, H., Xia, N., & Wu, G. (2021). Linking work-family conflict and burnout from the emotional resource perspective for construction professionals. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 14(5), 1093–1115. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMPB-06-2020-0181