ABSTRACT

Gender inequality in infant caregiving contributes to gender inequality in paid work, especially since workers often become parents during pivotal career stages. Whether women and men have equal access to paid leave for infant care can meaningfully shape patterns of caregiving in ways that have long-term economic impacts. We used a longitudinal database of paid leave policies in 193 countries to examine how the availability of paid leave for infant caregiving for each parent, the duration of leave reserved for each parent, and the existence of any incentives to encourage gender equity in leave-taking changed globally from 1995 to 2022. We find that the share of countries globally providing paid paternity leave increased four-fold from 13% to 56%, while the share providing paid maternity leave increased from 89% to 96%. Nevertheless, substantial gender disparities in leave duration persist: only 6% of the total paid leave available to families was reserved for fathers and an additional 11% of paid leave was available to either parent. Building on the global progress in providing paid leave to fathers over the past three decades will be critical to advancing gender equality at home and at work.

Introduction

Around the world, women continue to bear disproportionate responsibility for caregiving and household work (UN Women, Citation2020). According to the ILO, women spend 3 more hours per day on unpaid care work than men; in households with infants and young children, these gaps typically grow even wider (Charmes, Citation2019). Unequal unpaid caregiving responsibilities in turn shape inequalities in paid work. For example, in high-income countries, women with children ages 0–5 are 8 percentage points less likely than women the same age who do not have children to be in the labor force, whereas men with young children are 2.8 percentage points more likely (Addati et al., Citation2018). Globally, women with children ages 0–5 have the lowest employment rate (47.6%) when compared to fathers of children the same age (87.9%) as well as men and women without young children (Addati et al., Citation2018).

Longstanding restrictive gender norms contribute to these inequalities. Although surveys show that many fathers want to spend more time with their young children, gendered expectations around paid work and family caregiving often limit their engagement (Birkett & Forbes, Citation2019; Eerola et al., Citation2019; Kim & Kim, Citation2020; Petts et al., Citation2020). At the same time, laws and policies contribute to these norms – and measuring the extent to which gender inequality is directly embedded in caregiving policies is critical to understanding whether and how governments are playing a role in creating and maintaining gender disparities in the economy more broadly. Paid leave for infant caregiving is among the most consequential. Guaranteeing that both parents have adequate and equal access to paid leave following the birth or adoption of a child can meaningfully shape patterns of caregiving in ways that have long-term impacts, especially since workers often start their families during career stages that can be pivotal to long-term trajectories. At the current rate of progress, recent estimates suggest that achieving gender parity in the economy globally could take well over a century (World Economic Forum, Citation2022). Increasing gender equality in caregiving, particularly for infants, could markedly accelerate this timeline.

Past studies have examined the gendered nature of paid parental leave policies across a subset of high-income countries using different definitions of gender equal policy design. For example, (Ray et al., Citation2010) measured the extent to which 21 high-income countries provided ‘gender-egalitarian’ leave, defined as having gender-specific individual rights to paid leave and at least one-third of a family’s leave for reserved for fathers, while (Dearing, Citation2016) analyzed how 27 European countries’ paid leave policies compared to an ‘ideal’ policy for supporting gender equality at work, 14 months of well-paid leave of which half is reserved for fathers. Some research has also examined changes in leave policies over time in Europe. For example, Dobrotić and Blum (Citation2020) examine changes in provision of Ray et al. (Citation2010)’s gender-egalitarian leave and eligibility requirements for paid parental leaves across gender and employment status in 21 European countries at two points in time, 2006 and 2017.

Research on the gendered provision of paid leave for infant caregiving globally – distinguishing rights for mothers, fathers, and parents – was first available nearly two decades ago (Heymann, Citation2006; Heymann et al., Citation2004, Citation2006). While past global studies have either looked at the gendered nature of leave at a point of time (Addati et al., Citation2014; Heymann, Citation2013; Heymann et al., Citation2017; Heymann & Earle, Citation2010) or the evolution of paid maternity leave over time (Son & Böger, Citation2021), no previous studies have looked in all 193 UN countries at the evolution over time of more gender equal paid leave.

This article provides the most comprehensive longitudinal, global analysis to date of the gendered dimensions of national policies guaranteeing paid leave for infant caregiving. We first review the evidence on the relationship between gender equality in leave-taking and women’s earnings and employment, as well as which features of paid leave policies have been shown to boost men’s take-up of leave, increase gender-equitable division of leave, and improve women’s economic outcomes. Using a unique database built by the authors and members of our center that covers leave policies in all 193 UN member states, this study then examines the extent to which leave policies around the world incorporate these features, thus enabling and encouraging gender equality in infant caregiving. Further, to understand whether – and how quickly – leave policies are becoming more gender-equitable, this study measures how the availability of paid leave by gender has evolved from 1995 to 2022.

Background

The role of equal leave-taking for infant caregiving in shaping women’s economic outcomes

Men’s greater access to and use of paternal leave has been shown to have a direct relationship to women’s economic success in research from high-income countries. For example, a study from Sweden found that mothers’ earned income increased by nearly seven percent in the four years after the child’s birth for each additional month that her spouse took leave (Johansson, Citation2010). Studies have also found that parents share child care responsibilities more equally when fathers take paternal leave (Koslowski & O’Brien, Citation2022; Schober & Zoch, Citation2019; Tamm, Citation2019), which is likely to indirectly support women’s employment outcomes, particularly since fathers’ use of leave and longer leave-taking has been associated with both increased involvement with infants and greater participation in child care even well after leave has ended (Bünning, Citation2015; Huerta et al., Citation2014; Knoester et al., Citation2019; Nepomnyaschy & Waldfogel, Citation2007; Pilkauskas & Schneider, Citation2020; Pragg & Knoester, Citation2017; Tamm, Citation2019; Wray, Citation2020). In Germany, a 2015 study showed that fathers who took leave reduced their working hours and increased their involvement in childcare even after a short period of leave; those who took longer or solo leaves (while their partner was working) also subsequently increased their participation in housework (Bünning, Citation2015). A 2019 study confirmed these findings but also found that fathers who took leave spent more time on housework and child care measured 5 years following leave-taking (Tamm, Citation2019). The effect of leave-taking on engagement with children, as well as on maternal reports of co-parenting and responsibility for children, was also found for non-resident fathers in two U.S. studies of low-income families (Knoester et al., Citation2019; Pilkauskas & Schneider, Citation2020)

Moreover, the benefits of more equal leave-taking also extend to the broader wellbeing of mothers and children. In Norway, one study found that fathers’ longer leave-taking reduced mothers’ sick days from work by 5–10 percent (Bratberg & Naz, Citation2014), which could reflect a higher likelihood of shared caregiving when a child is ill. Fathers who take leave also report lower parenting stress (Lidbeck et al., Citation2018), greater satisfaction with their relationships with their children (Haas & Hwang, Citation2008) and spouses (Petts & Knoester, Citation2019), and lower rates of union dissolution (Lappegård et al., Citation2020).

The role of leave policy design in shaping equal leave-taking

A range of policy choices matter to whether parents regardless of gender can and will take leave following the birth of a child – and thus whether the benefits of equal leave-taking will be broadly experienced. Most fundamentally, equal and adequate amounts of paid leave must be available to each parent. As long as countries’ leave policies continue to provide a far longer duration of leave to mothers than to fathers – presuming they provide any leave to fathers at all – they will continue to reinforce the expectation that women will bear the primary responsibility for caregiving during infancy and early childhood (Baird et al., Citation2021). Substantial evidence has found that this presumption leads to discrimination against not only mothers in the workforce, but also all married women regardless of whether they have children (Arceo-Gomez & Campos-Vazquez, Citation2014; Becker et al., Citation2019; Kim et al., Citation2020; Muradova & Seitz, Citation2021); it can also contribute to retaliation against men who do take leave.

At the same time, past research has shown that simply making gender-neutral leave available to men is insufficient to substantially increase gender equality in leave-taking. Indeed, studies of high-income countries with varying paid parental leave policies show that men are most likely to take leave when it is specifically allocated to them (Bergqvist & Saxonberg, Citation2017; Duvander & Johansson, Citation2012; Escot et al., Citation2014; Mayer & Le Bourdais, Citation2019; Tremblay, Citation2014). For example, the enactment of ‘use it or lose it’ father’s quotas in Iceland, Norway, Denmark, and Sweden was followed by a marked increase in both the share of men taking leave and the length of leave taken (Cools et al., Citation2015; Duvander & Andersson, Citation2006; Jónsdóttir & Aðalsteinsson, Citation2008; Kluve & Tamm, Citation2009; Moss, Citation2015), and a 2011 study focused on the Nordic countries found that the father’s quota had the greatest effect of all the policy design elements intended to increase male uptake (Haas & Rostgaard, Citation2011). According to the most recent OECD data available, the gender gap in take-up in the five Nordic countries – all of which provide father-specific leave – is smaller than in other OECD countries without father-specific leave, although women’s use remains substantially higher than men’s (OECD, Citation2016).

Evidence also suggests that incentivizing or even requiring fathers to take an equal amount of shared parental leave can be effective, though the latter approach is rare. In Germany, for example, following the introduction of two additional months of shareable paid parental leave if the father took at least two of the ten months of shareable parental leave, take-up of parental leave by fathers rose from less than 3 percent before 2007 to 15 percent immediately after the reform to 36 percent in 2015 (Samtleben et al., Citation2019). In Portugal, the number of fathers taking leave rose from 596 in 2008 to 17,066 in 2010 after a ‘sharing bonus’ of an extra 30 days leave was adopted in 2009 (Correia et al., Citation2021). Incentives had a more modest effect in Japan, where fathers’ take-up increased incrementally each year from about 2% in 2012–13 to 7.5% in 2019 after a 2014 reform providing two extra months of leave if both parents take some of their shared entitlement (Koslowski et al., Citation2021; Nakazato, Citation2019). In Italy, one of the few countries to make a portion of paid paternity leave compulsory, nearly 10 times as many men took the two-day mandatory leave as took the two-day voluntary leave in 2016 (Cannito, Citation2020).

The role of leave policy design in advancing gender equality at work and at home

While most studies on paternal leave to date have examined either the impacts of men taking leave or the impact of leave policy design on men’s take-up, some have also looked directly at the relationship between the availability of paternal leave policies and economic outcomes for women. Likewise, some studies have examined whether reforms to paternal leave policies have any bearing on the division of household labor. In both cases, the presumed mechanism for achieving more equal outcomes is men’s greater take-up of leave; however, examining the effects of the policies themselves, regardless of take-up, can provide valuable insights into the nationwide impacts even with imperfect implementation.

Associational studies covering dozens of countries and a range of socioeconomic contexts have documented a positive relationship between paid leave for fathers and female labor force participation. In one study based on data from 53 developing countries, the female employment rate (in the private sector) was 7 percentage points higher in countries with paternity leave than countries without (Amin et al., Citation2016). Similarly, a recent study of paid leave policies in 34 OECD countries found that a majority of those providing at least 2 weeks of paid leave reserved for fathers were ranked among the top 40% of OECD countries in terms of female labor force participation rates. Countries that provided 2 weeks of reserved leave for fathers and countries providing incentives for fathers’ take-up also tended to have smaller gender gaps in labor force participation rates during the following years than other OECD countries (Raub et al., Citation2018).

Longitudinal studies assessing the impacts of policy changes at the country- and province-level including Quebec (Patnaik, Citation2019), Spain (Farré & González, Citation2012), Germany (Frodermann et al., Citation2020) and Denmark (Andersen, Citation2018) have yielded similar findings for women’s employment and earnings. A study of Quebec’s introduction of 5 weeks of a father’s quota found an increase in short-term maternal employment (Patnaik, Citation2019), as did the introduction of a two-week father’s quota in Spain (Farré & González, Citation2012). In Germany, one study found that the reform introducing two bonus months if both parents took leave led to an increase in mothers’ long-term earnings (Frodermann et al., Citation2020). Lastly, a study examining the relative length of fathers’ leave compared to mothers’ using a series of reforms in Denmark found that greater leave for fathers reduced the within-household gender wage gap by raising mothers’ wages. Moreover, more equal fathers’ leave also increased total household income from wages (Andersen, Citation2018).

Studies have also assessed the implications for caregiving and relationships within the home (Omidakhsh et al., Citation2020). Parents with children born after Norway established the ‘daddy quota’ reported 11 percent less conflict over domestic work 20 years later compared to adults who became parents prior to the quota (Kotsadam & Finseraas, Citation2011). Studies examining the introduction or expansion of paid leave for fathers in Canada (Patnaik, Citation2019; Wray, Citation2020) and Norway (Kotsadam & Finseraas, Citation2011; Rege & Solli, Citation2013) have found positive effects on men’s contribution to child care in families with different-sex married parents. A study of two reforms in Sweden, which reserved one month of parental leave for fathers in 1995 and a second month in 2002, found a significant impact on the study’s indicator of gender equality at home (use of leave to care for a sick child), based on over 10 years of follow-up data for each reform (Duvander & Johansson, Citation2019).

All together, these findings suggest that to the extent that leave policies for fathers lead to increased leave-taking among men generally, these policies have the potential to yield short- and long-run benefits for women’s economic equality, as well as fathers’ ability to fully engage at home. Greater equality in the duration of leave taken by men and women can help shift gender norms, alter employers’ expectations, and reduce gender discrimination at work. Meanwhile, greater leave-taking by fathers is likely to increase men’s participation in childcare, while simultaneously improving health and economic outcomes at the household level.

Methods

To understand the extent to which countries globally provide adequate and equitable leave for infant caregiving, we examined the original laws and policies of all 193 U.N. member states from 1995 to 2022 to capture the availability of paid leave for infant caregiving for each parent, the duration of leave available and/or reserved for each parent, and the existence of any incentives to encourage gender equity in leave-taking. To understand whether countries are increasingly providing more gender-equitable leave, we measured how the share of countries reserving leave for mothers and fathers, respectively, changed between 1995 and 2022, as well as how the total duration of leave available to each parent has evolved over this time period.

Data and sample

Data from a longitudinal policy database created by the authors were used in this study. This longitudinal database was built through a systematic review of workplace legislation in 193 United Nations (UN) member states available between 1995 and 2022.Footnote1

The primary source of policy data was original, full-text national-level labor and social security laws covering the private sector. Full-text copies of laws, in addition to the corresponding information on their history of amendment and repeal, were primarily identified through the International Labour Organization (ILO)'s NATLEX database, supplemented with legislation available through government websites and laws libraries. When legislation was unavailable and to corroborate existing legislation, analysts reviewed country reports from the Social Security Programs throughout the World database, which is compiled jointly by the U.S. Social Security Administration and the International Social Security Association, and the ILO Working Conditions Laws Database for historical information. To supplement and clarify information in available legislation, researchers consulted secondary sources such as the International Review of Leave Policies and Related Research (Koslowski et al., Citation2021), Mutual Information System on Social Protection (MISSOC), and Mutual Information System on Social Protection of the Council of Europe (MISSCEO).

Data was constructed by a team of multidisciplinary, multilingual team of policy analysts. For each country, two analysts coded each variable independently using a common framework and then discussed and reconciled their coding decisions to ensure accuracy in the final data entered into the database. When policies varied sub-nationally, analysts coded for the lowest level of paid leave available. Occasionally, analysts were unable to reach an agreement based on the common framework due to the complexity of legislation or the unique approach a country took. In these cases, countries were discussed with the full coding team to arrive at a consistent approach. Once coding was complete, researchers undertook systematic quality checks and reviews of outliers.

Measures

Policy indicators

To assess the extent to which policies have changed over time to support gender equality at work and at home, we constructed a series of indicators measuring the availability and duration of paid leave for mothers and fathers of infants. We considered three measures of adequacy of paid leave. First, whether leave was designed in a way to encourage fathers to take leave, such as by reserving leave for fathers or providing incentives for fathers to take shared leave. Second, whether differences in the duration of paid leave available to biological parents were limited to differences needed to support maternal health and establish breastfeeding. Third, whether there was no gender disparity in paid leave available for adoptive parents when there is no biological reason for gender differences in paid leave. While leave available for adoption presents a more straightforward analysis for assessing gender equality in paid leave, only a minority of countries globally guarantee paid leave for adoptive parents (Heymann et al., Citation2023). Throughout, paid leave includes all leave periods during which the employee receives some pay and includes a range of approaches to pay type (a percentage of earnings, or a flat amount, or a combination of both), source (employer or government) and timing (prorated throughout the leave period or as a lump sum).

Types of leave

‘Maternity’ and ‘paternity’ leave refer to leave reserved for mothers and fathers respectively. ‘Shared paid parental leave’ is paid leave for parents that can be used by mothers or fathers. When one or both parents have an individual entitlement to paid leave that they can choose to transfer to the other parent, leave is considered to be reserved for the parent with the original entitlement as evidence suggests that this parent, most often the mother, rarely transfers their leave (Walsh, Citation2019). We separately assess availability of paid leave for taking custody of an adopted infant,Footnote2 regardless of the terminology used in legislation for this leave. For example, Vietnam provides employees who are adopting an infant with what translates as ‘maternity’ leave until the child reaches 6 months. The legislation further specifies that if both parents meet the eligibility requirements, only one of them can take the leave. For our analyses, we treat this paid adoption leave as leave that can be taken by either parent. ‘Incentives for fathers’ take-up of leave’ are policies in which parents receive additional weeks or payment of leave if they both take a specified minimum amount of leave.

Duration of leave

In assessing duration of paid leave available to fathers, we consider whether countries have taken an important first step towards gender equality by ensuring fathers have at least two weeks of paid leave reserved for them given research evidence that this can support more gender egalitarian norms (Omidakhsh et al., Citation2020). We then assess whether countries have made a more substantial step towards gender equality by assessing whether men have access to at least 14 weeks of paid leave, which is the minimum ILO standard for paid maternity leave.

When assessing gender disparities of paid leave, we limit our analysis to countries that have met the minimum ILO standard of ensuring women have access to at least 14 weeks of paid leave. We then consider whether the gender disparity in access to paid leave for biological parents is 12 weeks or less. While individual experiences vary greatly, for an uncomplicated pregnancy, prior research suggests that 12 weeks is adequate to support most women’s prepartum health (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Citation2008, Citation2011; Sibai & Frangieh, Citation1995), physical recovery from birth (Chatterji & Markowitz, Citation2012; Dagher et al., Citation2014; McGovern et al., Citation1997), and establishment of breastfeeding (Ogbuanu et al., Citation2011; Skafida, Citation2012), and thus up to a 12-week differential in leave for men and women would be reasonable to account for the health-related aspects of birth. Nevertheless, given that some women need access to greater leave both before and after birth due to high-risk pregnancies, multiple births, and/or medical complications following delivery, it is important for countries to ensure women have access to additional medical leave when needed for health reasons.

For comparability, we calculate the duration of paid leave for births and adoption in weeks using a consistent conversion formula of 4.3 weeks per month, 7 days per week when legislation appeared to be referring to calendar days, and country-specific lengths of the work week (or 5.5 days if unspecified) if legislation was referring to working days.

Stratification measures

Income level

Countries in our sample are grouped according to the World Bank income classifications. The most recently available classifications based on per capita gross national income in 2021 were used.

Region

Countries in our sample are grouped into regions using the World Bank’s regional classifications.Footnote3

Analysis

For each year from 1995 to 2022 for all countries for which legislative sources were available, we calculate the percentage that have each type of paid leave policy and then examine changes in provision over the 28-year time period. As some current countries were not independent countries in earlier years, and it was not possible to determine policy availability in all years for all countries due to lack of available legislation or inconsistent secondary sources, we calculate the number of countries with a national policy in place as a percentage of the countries for which there is data for a given year. Data was always available for at least 97% of currently existing countries in any given year.

To measure progress in reducing the disparity in the length of leaves reserved for mothers and fathers, we calculate the portion of total weeks of parental leave available in each country for each type of leave and average this proportion across countries with available data to examine whether this distribution has changed over time such that men and women have more equal access to leave. Secondly, we calculate the difference in the number of weeks of leaves reserved for fathers and for mothers in the case of births as of 2022. We separately assess gender differences in the availability of paid adoption leave as of 2022. To measure progress in terms of the availability of policies with incentives for male take-up, we provide a count and description of the policies that have been enacted as of 2022.

Differences are assessed by region and income level. All data analyses were carried out using Stata version 14.

Results

Changes in the availability of paid leave reserved for fathers

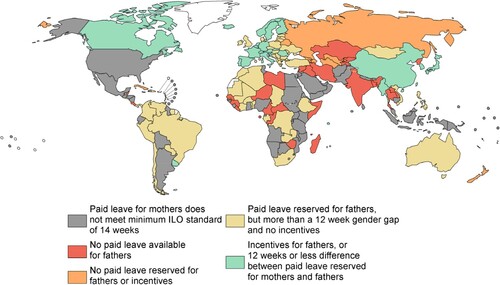

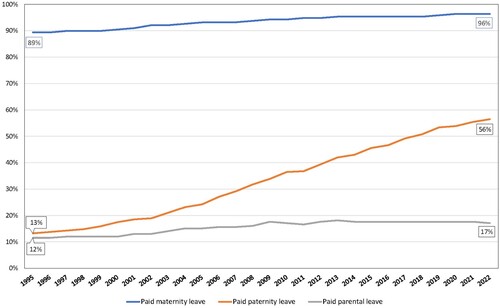

Since 1995, the number of countries guaranteeing paid paternity leave has increased dramatically (). Whereas, in 1995, just 13% of nations for which we had data had paid paternity leave, the proportion rose steadily reaching 56% in 2022, representing a four-fold increase (). Over the time period studied, 84 countries enacted paid paternity leave legislation. These countries come from all regions and income levels. By comparison, fewer countries enacted new paid maternity leave (p < 0.001) and parental leave policies (p < 0.001).

Figure 1. Change in the percentage of countries with paid paternity leave, maternity leave and parental leave, 1995–2022.

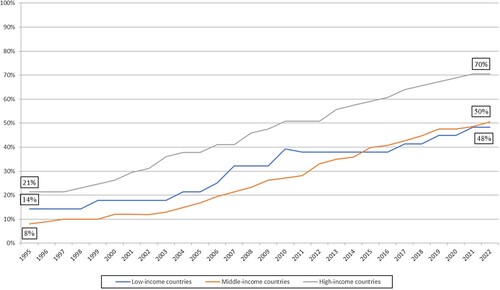

Across countries of all income levels, the availability of paid paternity leave rose dramatically between 1995 and 2022. The percentage of high-income and low-income countries with paid paternity leave more than tripled while in middle-income countries, it increased more than six-fold. However, high-income countries were more likely to guarantee paid paternity leave in both 1995 and 2022 compared to middle-income countries (p < 0.05 for both years) and in 2022 compared to low-income countries (p < 0.05) ().

Figure 2. Change in the percentage of countries that provide paid paternity leave, by national income, 1995–2022.

Availability of paternity leave in 2022 varies significantly across regions (p < 0.05). In 2022, countries in East Asia & the Pacific and in the Middle East & North Africa are least likely to have leave reserved for fathers. Paid paternity leave is most common in Europe & Central Asia; 75% of countries in this region have leave specifically for fathers. The pattern of growth in the availability of paternity leave across regions also varied markedly. Europe & Central Asia also experienced among the largest percentage point increases in guarantees of paid paternity leave between 1995 and 2022, rising from 20% to 75% (10 to 40 countries). In South Asia, 4 of 8 countries enacted paid paternity leave between 1995 and 2022, increasing from 0% to 50% of countries.

Change in the duration of paid leave for infant care

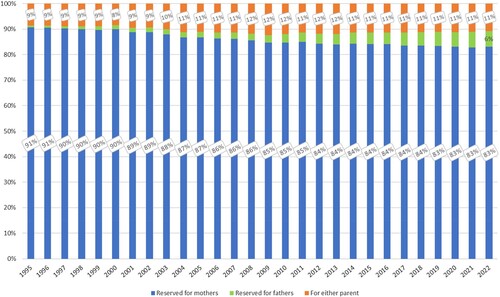

While the percentage of countries reserving paid leave for fathers more than quadrupled from 1995 to 2022, there was only modest progress in the duration of paid leave that fathers could use compared to mothers (see ). In 2022, only 6% of the total duration of paid leave available to families was reserved for fathers and an additional 11% of paid leave available to either parent, a modest increase from 1% reserved and 9% shared in 1995.

Figure 3. Change in the share of parental leave reserved for mothers, reserved for fathers and available to both parents, 1995–2022.

The length of leave reserved for fathers was short in 1995 and has generally remained so. Among countries providing paid paternity leave, the median duration was just two days in 1995. By 2022, the median duration was only 1.3 weeks. However, while only four countries (Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden) reserved at two weeks of paid leave for fathers in 1995, by 2022, 47 countries did, including 4 low-income countries and 14 middle-income countries While reserving at least two weeks of paid leave for fathers is most common in Europe and Central Asia (49% of countries), this approach is found in all other regions except the Middle East in North Africa, including 8 countries in East Asia and Pacific, 6 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, 5 countries in the Americas, and 2 countries in South Asia. However, only 13 countries (all high-income countries) have reserved 14 weeks or more of paid leave for fathers.

Policies incentivizing fathers’ take-up

Since the early 2000s, a handful of countries have amended their parental leave policies with the specific aim of increasing fathers’ take-up of leave and gender equality by offering families access to additional leave or a bonus payment if both parents take some of the leave. Eight countries have these incentives as part of current policy as of 2022 (). The most common approach is to provide additional leave (six countries). Just two countries, Austria and the Republic of Korea, offer bonus payments. In Austria, parents are only eligible for the bonus if leave is shared relatively equally. In contrast, Canada, Japan and Portugal have no minimum requirement for the family to receive a leave duration bonus. In addition to incentives, one country (Romania) has a disincentive that reduces the amount of paid leave available if fathers fail to take paid leave.

Table 1. Countries that have financial or leave duration bonuses to incentivize fathers’ take-up of shared parental leave

Gender differences in paid leave for biological parents

Even among countries that have taken the steps of passing paid leave reserved for fathers or incentives and ensuring women have access to at least the minimum ILO recommendation of 14 weeks of paid leave, the majority continue to have large gender gaps in paid leave. Globally, 29% of countries have more than a 12 week gender disparity between paid leave reserved for mothers and fathers and no incentives for fathers to take shared parental leave (). Just 12% of countries have a smaller gender disparity in leave reserved for mothers and fathers than might be justified based on biological reasons or incentives for fathers to take shared parental leave. High-income countries are more likely than middle- or low-income countries to have this smaller disparity (36% compared to 2% and 0%, p < 0.01 respectively for both).

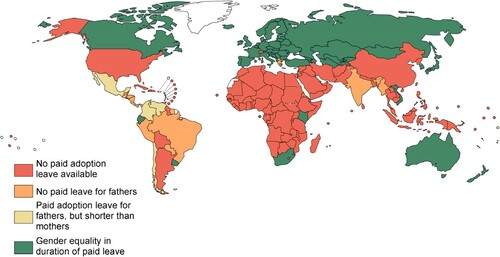

Gender differences in caregiving leave for adoption

Despite global progress in increasing leave availability for fathers of infants, legislation in many countries continues to reinforce women’s role as caregivers even in cases where there is no biological reason for women to provide caregiving instead of men, as is the case for adoption. In 8% of countries only adopting mothers can take paid leave when a different-sex couple adopts. In an additional 4% of countries, both parents can take paid adoption leave, but women are entitled to more paid leave than men. These disparities are more common in the Americas than in Europe and Central Asia and more common in middle-income than high-income countries. High-income countries are significantly more likely to provide adoption leave of equal length to men and women compared to middle-income countries (59% vs. 23%, p < 0.001) (See ). In three countries, women have access to longer paid adoption leave than men.

Discussion

Ensuring that mothers and fathers have equal access to sufficient leave following the birth or adoption of a child is fundamental to achieving gender equality in the home and at work. Globally, between 1995 and 2022, the percentage of countries with paid leave reserved for fathers more than quadrupled from 13% to 56%, while paid leave for mothers has become nearly universal, increasing from 89% to 96% of countries globally. Gender gaps in the provision of paid leave have also decreased markedly. Whereas in 1995, 143 countries reserved paid leave for mothers but not fathers of infants, by 2022, that number had dropped to 77. In addition, by 2022, 8 countries had introduced incentives for fathers to take shared leave. These provisions matter not only to providing men with opportunities to be more involved caregivers, but also for shifting norms that matter to women’s economic opportunities (Omidakhsh et al., Citation2020).

Despite this recent progress, however, gender disparities in paid leave coverage remain vast, reinforcing restrictive norms around unpaid caregiving and paid work. Nearly twice as many countries specifically reserve infant caregiving leave for women as do for men (186 vs. 109). The gender inequalities in duration are even greater. In 145 countries, fathers have less than 2 weeks of paid leave reserved for this use. No country reserves less than 2 weeks of paid leave for mothers. Just 24 countries have ensured women have access to the minimum 14 weeks of paid leave recommended by the ILO, while also ensuring that paid leave is reserved for fathers with a gender disparity of 12 weeks or less or that there are incentives for fathers to take share leave. Gender inequalities are even embedded in leave duration following adoption, despite the absence of any plausible biological rationale related to childbirth or breastfeeding: in 22 countries adoptive fathers have access to less paid leave than adoptive mothers. Specifically, 15 countries guarantee adoptive mothers but not fathers paid leave in two-parent families, while another 7 guarantee adoptive fathers less paid leave than adoptive mothers.

Still, there are also examples of policies to support greater gender equality in infant caregiving, both immediately following birth and longer-term. For example, leave for fathers in Sweden includes both 10 days (2 weeks) of paternity leave that must be taken right after the child’s birth, thereby encouraging fathers’ support during the mother’s recovery from childbirth and allowing both parents to be on leave at the same time initially, followed by a much longer individual leave when fathers can be the sole care provider. Further, some countries that are passing paid leave for infant caregiving for the first time are including leave for both women and men, signaling a growing recognition among policymakers that greater gender equity in leave is important. Suriname, for example, which just adopted its first national policy guaranteeing paid leave for infant caregiving in 2019, reserved 8 working days of leave for fathers, designated for use at specific times during the first four months of a child’s life. While a modest allotment, eight days positions Suriname as a leader on paternity leave among low- and middle-income countries. As this progress on gender equity in leave continues, the potential benefits for both families and countries are significant, given the strong research evidence that ensuring men have access to paid leave around the birth or adoption can help establish a pattern of paternal involvement and facilitate women’s recovery or return to and sustained participation at work.

Changing laws to enable and encourage fathers to take paid leave is only a first step; improving other aspects of leave policy design and addressing normative barriers to gender-equal caregiving more directly and comprehensively are also important interventions. Previous research highlights a wage replacement rate of at least 80% is a critical determinant of parents’ take-up, particularly fathers’ (Karu & Tremblay, Citation2018; Koslowski & O’Brien, Citation2022; O’Brien, Citation2009; Raub et al., Citation2018). Studies also make clear the importance of including flexibility (Marynissen et al., Citation2019; Mussino et al., Citation2019) in how the leave can be taken and addressing institutional and cultural barriers that prevent fathers, as well as mothers, from using their leave (Haas & Hwang, Citation2019; Koslowski & Kadar-Satat, Citation2019; Lucia-Casademunt et al., Citation2018). Legal provisions that prohibit retaliation for taking paid leave and protect caregivers of all genders from discrimination are also essential (Bose et al., Citation2020; Heymann et al., Citation2023).

Numerous high-income countries have demonstrated that providing leave is compatible with maintaining high levels of competitiveness and employment (Earle & Heymann, Citation2006; Heymann & Earle, Citation2010). Even when using generous duration and high-end take-up of benefits, the cost of paid parental leave even at full wage replacement is relatively small. For example, guaranteeing 26 weeks of paid leave for infant care to both mothers and fathers, assuming the parents had two children, would require the provision of income equal to 4% of earnings. This is a small investment to make for companies when weighed against lower job turnover, lower associated recruitment and training costs, and higher productivity. For countries, the investment case is even clearer when factoring in the benefits of paid leave for infant health, maternal health, and increased competitiveness from higher labor force participation and lower dependency ratios (Folbre, Citation2010).

Areas for future research

This study analyzes the availability and duration of paid leave policies that cover workers in the formal economy, with a focus on assessing gender gaps in policies. Future research focused on paid leave design should also examine leave accessibility across economic sectors. In particular, policies need to be designed to address the needs of workers in the informal economy globally. Importantly, however, past research suggests that paid leave policies – even if not explicitly structured to reach the informal workforce – have impacts beyond the formal economy. For example, studies focused on LMICs have found that extending the duration of paid maternity leave significantly reduces infant mortality and diarrheal disease and increases breastfeeding and immunizations (Chai et al., Citation2018, Citation2020; Hajizadeh et al., Citation2015; Nandi et al., Citation2016). These impacts may be because policies governing the formal economy have spillover effects for informal workplaces, as other research has documented for the minimum wage (Ponce et al., Citation2018). Nevertheless, explicitly covering informal workers has both practical and normative value, and should be the focus of further study. Future studies should also examine the extent to which national paid leave policies adequately address the needs of all family types including single parents, same-sex couples, and grandparent-headed households, among others. In addition, while this study focuses on the availability and duration of paid leave across gender because those are the largest gaps globally, more research is needed to understand the incentives for unequal leave uptake. Wage replacement rates can impact which families and which parents within families can afford to take leave. It will be valuable to assess whether reserving leave for fathers is more effective in raising uptake as compared to implementing a financial or leave duration bonus for sharing family entitlements to paid leave.

Paid parental leave alone is not enough on its own to achieve gender equality in employment and caregiving, and many other policies are complementary to paid leave (Gornick & Meyers, Citation2003; Nieuwenhuis, Citation2022). For example, paid breastfeeding breaks support mothers’ return to work while infants are young, and may help enable fathers to provide care during this time while allowing for continued breastfeeding. Affordable, accessible, quality childcare and early childhood education is critically important to children’s development (Ansari & Winsler, Citation2012; Yamaguchi et al., Citation2018) and enables mothers to return to work (Hook & Paek, Citation2020; Morrissey, Citation2017; Müller & Wrohlich, Citation2020). Future studies should consider how these policies work alongside parental leave policies to support gender equality at work and home.

In sum, examining policy changes over more than 25 years indicates that progress on adopting paid leave for fathers and closing gender gaps in access to leave for infant caregiving is accelerating. Nevertheless, the gender disparities that remain embedded in national leave policies are substantial. These inequalities directly contradict the realization of all 193 UN member states’ commitments through the Sustainable Development Goals to end gender discrimination in the law by 2030 and will impede achieving gender equality broadly (SDG 5). Achieving these aims and addressing one of the greatest persisting barriers to gender equality at work and in caregiving will require improving paid leave policies in all countries where gaps remain.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Alison Earle

Alison Earle is Senior Work-Family Policy Research Analyst at the WORLD Policy Analysis Center in the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health. Her research focuses on the availability and inclusiveness of paid family leave policies in the United States and globally, and their impact on gender and economic inequalities.

Amy Raub

Amy Raub is a Principal Research Analyst at the WORLD Policy Analysis Center in the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health. Her work focuses on the development of quantitative measures of laws and policies in all 193 UN countries and how these measures can be used to advance monitoring and accountability.

Aleta Sprague

Aleta Sprague is a senior legal analyst at the WORLD Policy Analysis Center in the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health and an attorney whose career has focused on advancing public policies and laws that address inequality. She has co-authored a range of publications examining how laws and policies shape racial, gender, and socio-economic disparities.

Jody Heymann

Jody Heymann is Distinguished Professor at the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health, Luskin School of Public Affairs, and Geffen School of Medicine, and the Founding Director of the WORLD Policy Analysis Center. Her work addresses how social policy can advance equality across populations globally.

Notes

1 Information was collected on legislation applicable to the national population. Subnational policies and policies based on collective agreements available to subgroups of employees were not coded.

2 Paid leave for fostering an infant or for fostering to adopt an infant is not included unless the same policy applies to adoption leave. In some countries, paid leave for adoption is only available for infants or the duration is longer.

3 One exception is the classification of Malta as ‘Europe and Central Asia’ instead of ‘Middle East and North Africa’. Geographically, Malta falls between Italy and Libya, however, Malta has been a member of the EU since 2004 and generally has had an affiliation with Europe.

References

- Addati, L., Cassirer, N., & Gilchrist, K. (2014). Maternity and paternity at work: Law and practice across the world. International Labour Office.

- Addati, L., Cattaneo, U., Esquivel, V., & Valarino, I. (2018). Care work and care jobs for the future of decent work. International Labour Organization. https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_633135/lang–en/index.htm.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2008). ACOG practice bulletin no. 95: Anemia in pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 112(1), 201. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181809c0d

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2011). ACOG practice bulletin no. 123: Thromboembolism in pregnancy. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 118(3), 718–729. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182310c4c

- Amin, M., Islam, A., & Sakhonchik, A. (2016). Does paternity leave matter for female employment in developing economies? Evidence from firm-level data. Applied Economics Letters, 23(16), 1145–1148. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-7588

- Andersen, S. H. (2018). Paternity leave and the motherhood penalty: New causal evidence. Journal of Marriage and Family, 80(5), 1125–1143. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12507

- Ansari, A., & Winsler, A. (2012). School readiness among low-income, Latino children attending family childcare versus centre-based care. Early Child Development and Care, 182(11), 1165–1185. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2011.622755

- Arceo-Gomez, E. O., & Campos-Vazquez, R. M. (2014). Race and marriage in the labor market: A discrimination correspondence study in a developing country. American Economic Review, 104(5), 376–380. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.104.5.376

- Baird, M., Hamilton, M., & Constantin, A. (2021). Gender equality and paid parental leave in Australia: A decade of giant leaps or baby steps? Journal of Industrial Relations, 63(4), 546–567. https://doi.org/10.1177/00221856211008219

- Becker, S. O., Fernandes, A., & Weichselbaumer, D. (2019). Discrimination in hiring based on potential and realized fertility: Evidence from a large-scale field experiment. Labour Economics, 59, 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2019.04.009

- Bergqvist, C., & Saxonberg, S. (2017). The state as a norm-builder? The take-up of parental leave in Norway and Sweden. Social Policy & Administration, 51(7), 1470–1487. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12251

- Birkett, H., & Forbes, S. (2019). Where’s dad? Exploring the low take-up of inclusive parenting policies in the UK. Policy Studies, 40(2), 205–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2019.1581160

- Bose, B., Quinones, J., Moreno, G., Raub, A., Huh, K., & Heymann, J. (2020). Protecting adults with caregiving responsibilities from workplace discrimination: Analysis of national legislation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(3), 953–964. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12660

- Bratberg, E., & Naz, G. (2014). Does paternity leave affect mothers’ sickness absence? European Sociological Review, 30(4), 500–511. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcu058

- Bünning, M. (2015). What happens after the ‘daddy months’? Fathers’ involvement in paid work, childcare, and housework after taking parental leave in Germany. European Sociological Review, 31(6), 738–748. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcv072

- Cannito, M. (2020). The influence of partners on fathers’ decision-making about parental leave in Italy: Rethinking maternal gatekeeping. Current Sociology, 68(6), 832–849. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011392120902231

- Chai, Y., Nandi, A., & Heymann, J. (2018). Does extending the duration of legislated paid maternity leave improve breastfeeding practices? Evidence from 38 low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Global Health, 3(5), e001032. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2018-001032

- Chai, Y., Nandi, A., & Heymann, J. (2020). Association of increased duration of legislated paid maternity leave with childhood diarrhoea prevalence in low-income and middle-income countries: Difference-in-differences analysis. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 74(5), 437–444. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2019-212127

- Charmes, J. (2019). The unpaid care work and the labour market. An analysis of time use data based on the latest world compilation of time-use surveys. International Labour Office. https://www.ilo.org/gender/Informationresources/Publications/WCMS_732791/lang–en/index.htm.

- Chatterji, P., & Markowitz, S. (2012). Family leave after childbirth and the mental health of new mothers. Journal of Mental Health Policy Economics, 15(2), 61–76. PMID: 22813939.

- Cools, S., Fiva, J. H., & Kirkebøen, L. J. (2015). Causal effects of paternity leave on children and parents. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 117(3), 801–828. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjoe.12113

- Correia, R. B., Wall, K., & Leitão, M. (2021). Portugal country note. In A. Koslowski, I. Dobrotić, G. Kaufman, & P. Moss (Eds.), International review of leave policies and research 2021 (pp. 641). International Network on Leave Policies and Research. https://www.leavenetwork.org/annual-review-reports/.

- Dagher, R. K., McGovern, P. M., & Dowd, B. E. (2014). Maternity leave duration and postpartum mental and physical health: Implications for leave policies. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 39(2), 369–416. https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-2416247

- Dearing, H. (2016). Gender equality in the division of work: How to assess European leave policies regarding their compliance with an ideal leave model. Journal of European Social Policy, 26(3), 234–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928716642951

- Dobrotić, I., & Blum, S. (2020). Inclusiveness of parental-leave benefits in twenty-one European countries: Measuring social and gender inequalities in leave eligibility. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 27(3), 588–614. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxz023

- Duvander, A.-Z., & Andersson, G. (2006). Gender equality and fertility in Sweden. Marriage & Family Review, 39(1-2), 121–142. https://doi.org/10.1300/J002v39n01_07

- Duvander, A.-Z., & Johansson, M. (2012). What are the effects of reforms promoting fathers’ parental leave use? Journal of European Social Policy, 22(3), 319–330. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928712440201

- Duvander, A.-Z., & Johansson, M. (2019). Does fathers’ care spill over? Evaluating reforms in the Swedish parental leave program. Feminist Economics, 25(2), 67–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2018.1474240

- Earle, A., & Heymann, J. (2006). A comparative analysis of paid leave for the health needs of workers and their families around the world. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 8(3), 241–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876980600858465

- Eerola, P., Lammi-Taskula, J., O’Brien, M., Hietamäki, J., & Räikkönen, E. (2019). Fathers’ leave take-up in Finland: Motivations and barriers in a complex Nordic leave scheme. SAGE Open, 9(4), 215824401988538. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019885389

- Escot, L., Fernández-Cornejo, J. A., & Poza, C. (2014). Fathers’ use of childbirth leave in Spain. The effects of the 13-day paternity leave. Population Research and Policy Review, 33, 419–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-013-9304-7

- Farré, L., & González, L. (2012). Perforated peptic ulcer in an adolescent girl. Pediatric Emergency Care, 28, 709–711. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0b013e31825d21c3

- Folbre, N. (2010). Valuing children: Rethinking the economics of the family. Harvard University Press.

- Frodermann, C., Wrohlich, K., & Zucco, A. (2020). Parental leave reform and long-run earnings of mothers (center for economic policy analysis discussion papers). University of Potsdam. https://econpapers.repec.org/paper/potcepadp/16.htm.

- Gornick, J. C., & Meyers, M. (2003). Families that work: Policies for reconciling parenthood and employment. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Haas, L., & Hwang, C. P. (2008). The impact of taking parental leave on fathers’ participation in childcare and relationships with children: Lessons from Sweden. Community, Work & Family, 11(1), 85–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668800701785346

- Haas, L., & Hwang, C. P. (2019). Workplace support and European fathers’ use of state policies promoting shared childcare. Community, Work & Family, 22(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2018.1556204

- Haas, L., & Rostgaard, T. (2011). Fathers’ rights to paid parental leave in the Nordic countries: Consequences for the gendered division of leave. Community, Work & Family, 14(2), 177–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2011.571398

- Hajizadeh, M., Heymann, J., Strumpf, E., Harper, S., & Nandi, A. (2015). Paid maternity leave and childhood vaccination uptake: Longitudinal evidence from 20 low-and-middle-income countries. Social Science & Medicine, 140, 104–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.07.008

- Heymann, J. (2006). Forgotten families: Ending the growing crisis confronting children and working parents in the global economy. Oxford University Press.

- Heymann, J. (2013). Children’s chances. Harvard University Press.

- Heymann, J., & Earle, A. (2010). Raising the global floor: Dismantling the myth that we can’t afford good working conditions for everyone. Stanford University Press.

- Heymann, J., Earle, A., Simmons, S., & Kuehnhoff, A. (2004). The work, family and equity index: Where does the United States stand globally. Harvard School of Public Health, Project on Global Working Families.

- Heymann, J., Simmons, S., & Earle, A. (2006). Global transformations in work and family. In S. Bianchi, L. Casper, & R. King (Eds.), Work, Family, Health, and Well-Being (pp. 507–526). New York City: Routledge.

- Heymann, J., Sprague, A., Nandi, A., Earle, A., Batra, P., Schickedanz, A., Chung, P. J., & Raub, A. (2017). Paid parental leave and family wellbeing in the sustainable development era. Public Health Reviews, 38(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-017-0067-2

- Heymann, J., Sprague, A., & Raub, A. (2023). Equality within our lifetimes: How laws and policies can close—or widen—gender gaps in economies worldwide. University of California Press.

- Hook, J. L., & Paek, E. (2020). National family policies and mothers’ employment: How earnings inequality shapes policy effects across and within countries. American Sociological Review, 85(3), 381–416. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122420922505

- Huerta, M. C., Adema, W., Baxter, J., Han, W.-J., Lausten, M., Lee, R., & Waldfogel, J. (2014). Fathers’ leave and fathers’ involvement: Evidence from four OECD countries. European Journal of Social Security, 16(4), 308–346. https://doi.org/10.1177/138826271401600403

- Johansson, E.-A. (2010). The effect of own and spousal parental leave on earnings. IFAU - Institute for Labour Market Policy Evaluation Working Paper, 4, 1–32.

- Jónsdóttir, B., & Aðalsteinsson, G. (2008). Icelandic parents' perception of parental leave. In G. B. Eydal, & I. V. Gíslason (Eds.), Equal rights to earn and care: Parental leave in Iceland (pp. 65–85). Reykjavík: Félagsvísindastofnun Háskóla Íslands.

- Karu, M., & Tremblay, D.-G. (2018). Fathers on parental leave: An analysis of rights and take-up in 29 countries. Community, Work and Family, 21(3), 344–362. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2017.1346586

- Kim, M., Lyu, J., Nedelescu, D., & Shen, L. (2020). Do marriage and children deprive women’s hiring opportunities-a field experiment. SSRN, 3766405. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3766405

- Kim, Y., & Kim, S. (2020). Relational ethics as a cultural constraint on fathers’ parental leave in a Confucian welfare state, South Korea. Social Policy & Administration, 54(5), 684–698. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12565

- Kluve, J., & Tamm, M. (2009). Now Daddy’s Changing Diapers and Mommy’s Making Her Career: Evaluating a Generous Parental Leave Regulation Using a Natural Experiment.

- Knoester, C., Petts, R. J., & Pragg, B. (2019). Paternity leave-taking and father involvement among socioeconomically disadvantaged U.S. Fathers. Sex Roles, 81(5-6), 257–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0994-5

- Koslowski, A., Blum, S., Dobrotić, I., Kaufman, G., & Moss, P. (2021). 17th International Review of Leave Policies and Related Research 2021 [Annual Review]. https://www.leavenetwork.org/fileadmin/user_upload/k_leavenetwork/annual_reviews/2021/002_Koslowski_et_al_Leave_Review_2021_full.pdf.

- Koslowski, A., & Kadar-Satat, G. (2019). Fathers at work: Explaining the gaps between entitlement to leave policies and uptake. Community, Work & Family, 22(2), 129–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2018.1428174

- Koslowski, A., & O’Brien, M. (2022). Fathers and family leave policies: What public policy can do to support families. In M. Grau Grau, M. las Heras Maestro, & H. Riley Bowles (Eds.), Engaged fatherhood for men, families and gender equality (pp. 141–152). Springer.

- Kotsadam, A., & Finseraas, H. (2011). The state intervenes in the battle of the sexes: Causal effects of paternity leave. Social Science Research, 40(6), 1611–1622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2011.06.011

- Lappegård, T., Duvander, A. Z., Neyer, G., Viklund, I., Andersen, S. N., & Garðarsdóttir, Ó. (2020). Fathers’ use of parental leave and union dissolution. European Journal of Population, 36(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-019-09518-z

- Lidbeck, M., Bernhardsson, S., & Tjus, T. (2018). Division of parental leave and perceived parenting stress among mothers and fathers. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 36(4), 406–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2018.1468557

- Lucia-Casademunt, A. M., García-Cabrera, A. M., Padilla-Angulo, L., & Cuéllar-Molina, D. (2018). Returning to work after childbirth in Europe: Well-being, work-life balance, and the interplay of supervisor support. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00068

- Marynissen, L., Mussino, E., Wood, J., & Duvander, A. Z. (2019). Fathers’ parental leave uptake in Belgium and Sweden: Self-evident or subject to employment characteristics? Social Sciences, 8(11), 312. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8110312

- Mayer, M., & Le Bourdais, C. (2019). Sharing parental leave among dual-earner couples in Canada: Does reserved paternity leave make a difference? Population Research and Policy Review, 38(2), 215–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-018-9497-x

- McGovern, P., Dowd, B., Gjerdingen, D., Moscovice, I., Kochevar, L., & Lohman, W. (1997). Time off work and the postpartum health of employed women. Medical Care, 35(5), 507–521. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005650-199705000-00007

- Morrissey, T. W. (2017). Child care and parent labor force participation: A review of the research literature. Review of Economics of the Household, 15(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-016-9331-3

- Moss, P. (2015). 11th International Review of Leave Policies and Related Research 2015 [Annual Review]. https://www.leavenetwork.org/fileadmin/user_upload/k_leavenetwork/annual_reviews/2015_full_review3_final_8july.pdf.

- Müller, K. U., & Wrohlich, K. (2020). Does subsidized care for toddlers increase maternal labor supply? Evidence from a large-scale expansion of early childcare. Labour Economics, 62(C). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2019.101776

- Muradova, S., & Seitz, W. (2021). Gender discrimination in hiring: Evidence from an audit experiment in Uzbekistan. The World Bank.

- Mussino, E., Tervola, J., & Duvander, A.-Z. (2019). Decomposing the determinants of fathers’ parental leave use: Evidence from migration between Finland and Sweden. Journal of European Social Policy, 29(2), 197–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928718792129

- Nakazato, H. (2019). Japan: Leave policies and attempts to increase fathers’ take-up. Figure 6.4. Proportion of eligible fathers taking parental leave: 1996-2016. In P. Moss, A.-Z. Duvander, & A. Koslowski (Eds.), Parental leave and beyond: Recent international developments, current issues and future directions (p. 105). Policy Press.

- Nandi, A., Hajizadeh, M., Harper, S., Koski, A., Strumpf, E. C., & Heymann, J. (2016). Increased duration of paid maternity leave lowers infant mortality in Low- and middle-income countries: A quasi-experimental study. PLoS Medicine, 13(3), e1001985–18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001985

- Nepomnyaschy, L., & Waldfogel, J. (2007). Paternity leave and fathers’ involvement with their young children. Community, Work & Family, 10(4), 427–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668800701575077

- Nieuwenhuis, R. (2022). No activation without reconciliation? The interplay between ALMP and ECEC in relation to women’s employment, unemployment and inactivity in 30 OECD countries, 1985–2018. Social Policy & Administration, 56(5), 808–826. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12806

- O’Brien, M. (2009). Fathers, parental leave policies, and infant quality of life: International perspectives and policy impact. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 624, 190–213. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40375960.

- OECD. (2016). OECD family database—PF2.2: Use of childbirth-related leave by mothers and fathers. OECD.

- Ogbuanu, C., Glover, S., Probst, J., Hussey, J., & Liu, J. (2011, August). Balancing work and family: Effect of employment characteristics on breastfeeding. Journal of Human Lactation, 27(3), 225–238. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334410394860

- Omidakhsh, N., Sprague, A., & Heymann, J. (2020). Dismantling restrictive gender norms: Can better designed paternal leave policies help? Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 20(1), 382–396. https://doi.org/10.1111/asap.12205

- Patnaik, A. (2019). Reserving time for daddy: The consequences of fathers’ quotas. Journal of Labor Economics, 37(4), 1009–1059. https://doi.org/10.1086/703115

- Petts, R. J., & Knoester, C. (2019). Paternity leave and parental relationships: Variations by gender and mothers’ work statuses. Journal of Marriage and Family, 81(2), 468–486. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12545

- Petts, R. J., Knoester, C., & Li, Q. (2020). Paid paternity leave-taking in the United States. Community, Work & Family, 23(2), 162–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2018.1471589

- Pilkauskas, N. V., & Schneider, W. J. (2020). Father involvement among nonresident dads: Does paternity leave matter? Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(5), 1606–1624. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12677

- Ponce, N., Shimkhada, R., Raub, A., Daoud, A., Nandi, A., Richter, L., & Heymann, J. (2018). The association of minimum wage change on child nutritional status in LMICs: A quasi-experimental multi-country study. Global Public Health, 13(9), 1307–1321. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2017.1359327

- Pragg, B., & Knoester, C. (2017). Parental leave use among disadvantaged fathers. Journal of Family Issues, 38(8), 1157–1185. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X15623585

- Raub, A., Nandi, A., Earle, A., Guzman, N. D. C., Wong, E., Chung, P., Batra, P., Schickedanz, A., Bose, B., Jou, J., Franken, D., & Heymann, J. (2018). Paid parental leave: A detailed look at approaches across OECD countries. WORLD Policy Analysis Center.

- Ray, R., Gornick, J. C., & Schmitt, J. (2010). Who cares? assessing generosity and gender equality in parental leave policy designs in 21 countries. Journal of European Social Policy, 20(3), 196–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928710364434

- Rege, M., & Solli, I. F. (2013). The impact of paternity leave on fathers’ future earnings. Demography, 50(6), 2255–2277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-013-0233-1

- Samtleben, C., Schaeper, C., & Wrohlich, K. (2019). Elterngeld und ElterngeldPlus: Nutzung durch Vater gestiegen, Aufteilung zwischen Muttern und Vatern aber nochsehr ungleich [Parental Allowance and Parental Allowance Plus: Increased use by fathers, but distribution between mothers and fathers is still very unequal] (86(35); DIW Wochenbericht, pp. 607-613.). German Institute for Economic Research. https://ideas.repec.org/a/diw/diwwob/86-35-1.html.

- Schober, P. S., & Zoch, G. (2019). Change in the gender division of domestic work after mothers or fathers took leave: Exploring alternative explanations. European Societies, 21(1), 158–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2018.1465989

- Sibai, B., & Frangieh, A. (1995). Maternal adaptation to pregnancy. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 7(6), 420–426. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001703-199512000-00003

- Skafida, V. (2012). Juggling work and motherhood: The impact of employment and maternity leave on breastfeeding duration: A survival analysis on growing up in Scotland data. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 16, 519–527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-011-0743-7

- Son, K., & Böger, T. (2021). The inclusiveness of maternity leave rights over 120 years and across five continents. Social Inclusion, 9(2), 275–287. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v9i2.3785

- Tamm, M. (2019). Fathers’ parental leave-taking, childcare involvement and labor market participation. Labour Economics, 59, 184–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2019.04.007

- Tremblay, D. G. (2014). Quebec’s policies for work-family balance: A model for Canada? In B. J. Fox (Ed.), Family patterns, gender relations (pp. 271–290). Oxford University Press.

- UN Women. (2020). Progress of the world’s women: 2019-2020 (p. 228). Geneva: UN Women.

- Walsh, E. (2019). Fathers and Parental Leave (Parents at Work) [Short article]. Australian Institute of Family Studies. https://aifs.gov.au/resources/short-articles/fathers-and-parental-leave.

- World Economic Forum. (2022). Global Gender Gap Report 2022 (p. 374) [Insight Report]. World Economic Forum. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2022.pdf.

- Wray, D. (2020). Paternity leave and fathers’ responsibility: Evidence from a natural experiment in Canada. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(2), 534–549. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12661

- Yamaguchi, S., Asai, Y., & Kambayashi, R. (2018). How does early childcare enrollment affect children, parents, and their interactions? Labour Economics, 55, 56–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2018.08.006