ABTRACT

One particularly understudied aspect of the gendered division of work and care is paid leave to care for sick children (CSC). Even though fathers in Sweden take a relatively large share of CSC, fathers still use less leave than mothers. One potential explanation is gender differences in working conditions and income. This study uses high-quality survey data from the Swedish Level-of-Living Survey (LNU) 2000 and 2010 with linked register data to analyse, first, associations between working conditions and income on the one hand and CSC use on the other hand and second, the role working conditions and income play in the gender differences in CSC. The results from a two-part model show that the relatively large gender difference in the likelihood of using CSC is somewhat reduced when controlling for working conditions and income. The relatively small gender difference in the number of CSC days used by CSC users is diminished and rendered statistically non-significant when controlling for working conditions and income. Hence, gender differences in working conditions and income contribute to the gender difference in the number of CSC days used by CSC users, while other explanations need to be found for fathers’ lower likelihood of using any CSC.

Introduction

Sweden’s leave to care for sick children (CSC) is a social insurance that allows parents to take leave from work to care for a sick child with economic compensation for part of the income loss. CSC is mostly used for minor illnesses and shorter leave periods lasting a few days at a time. Since the introduction of CSC in 1974, the share of leave use among fathers has varied between 32 and 40 per cent (with lower levels in the late 1980s and the 1990s). Similar to standard parental leave, parents forgo market work to care for children when they use CSC. It is therefore likely that labour market factors have an impact on the use and the division of CSC. With a gender-segregated labour market, the gender difference in CSC use may be related to labour market differences between fathers and mothers. Previous studies have analysed the relationship between CSC and income from gainful employment and found that income does play a role but does not fully explain the gender difference in CSC (Amilon, Citation2007; Boye, Citation2015). Parents state that working conditions, i.e. circumstances and aspects of the job other than income that affect labour, such as flexibility and time constraints, influence the use and the division of CSC (Eek & Axmon, Citation2011; Unionen, Citation2018). Nevertheless, the associations between working conditions and CSC use are seldom studied (for exceptions, see Boye, Citation2015; Ichino et al., Citation2019, and the descriptive reports by Eek & Axmon, Citation2011 and Unionen, Citation2018). This study aims to increase the knowledge about the gender difference in CSC use and to investigate whether results of previous studies of CSC can be further understood with detailed information on parents’ working conditions and gender differences in working conditions (c.f., Antón et al., Citation2023).

Parents in Sweden use on average seven days of CSC in a year. Even though the yearly average per parent is modest, the use is to a large degree concentrated to the first 3–4 months each year (see, e.g. Swedish Social Insurance Agency, Citation2012). Hence, an average parent may use about one CSC day every other week during this period. As CSC is mostly unplanned and unpredictable, this may be quite disruptive for the parent’s work effort. This disruptiveness may be one reason that a negative association has been found between CSC use and long-term wage growth (Boye, Citation2019). Consequently, studies of CSC produce knowledge about an insurance and type of childcare that impact the lives and work of parents at the time of leave use and their career and financial resources during a long time period.

A significant group of parents chooses not to use the leave even though it is available to all working as well as unemployed parents. For example, the share of non-users among employed parents was 56 per cent in 2010 (Swedish Social Insurance Agency, Citation2013). Therefore, it is important to study not only the number of CSC days used but also the likelihood of leave use.

Similar to other forms of care, the use and division of CSC are likely to be influenced by gender construction in couples (Ichino et al., Citation2019; c.f. Fenstermaker Berk, Citation1985; West & Zimmerman, Citation1987). Fathers and mothers may use CSC in a gendered way, for example, due to the norms and ideals of motherhood and fatherhood or differences in how parents value the labour market work of mothers and fathers (Alsarve et al., Citation2016). Unlike standard parental leave, which is mainly used to care for infants, CSC is seldom used to care for children under one year of age (Statistics Sweden, Citation2022a). It is therefore unlikely that CSC use is influenced by physiological factors directly related to childbirth, and norms and ideals associated with such factors. Breastfeeding practices and ideals, for example, have in qualitative interview studies been shown to be important considerations when parents make decisions on the use and division of standard parental leave (e.g. Alsarve et al., Citation2016; Bergqvist & Saxonberg, Citation2017). The study of CSC use can contribute to the understanding of how division of care in the family relates to gender and to labour market factors, independent of the physiological factors linked to early (biological) parenthood and norms and ideals directly associated with these physiological factors.

Despite the potential benefits of studying CSC and the need for a greater understanding of the variation in its use, studies analysing CSC are few in number (for exceptions, see Amilon, Citation2007; Boye, Citation2015; Eriksson, Citation2011; Eriksson & Nermo, Citation2010; Ichino et al., Citation2019, see also the descriptive reports by Eek & Axmon, Citation2011 and Unionen, Citation2018). This study analyses variations in CSC use by working conditions and income and the role these factors play in explaining the gender differences in use of CSC. To this end, the study analyses survey data from the Swedish Level-of-Living Survey (LNU), with linked register data, for the years 2000 and 2010. In a two-part model, the first part uses a Linear Probability Model (LPM) to analyse the likelihood of taking any CSC. The second part includes parents who used some CSC and models the number of CSC days used using Ordinary Least Squares regression (OLS).

Leave to care for sick children and the Swedish labour market

CSC is part of Sweden’s temporary parental leave scheme. CSC comprises 120 days per child annually that parents can use to stay home from paid work to care for a sick child or to take a child to a health care provider (i.e. each child can be at home for up to 120 days per year). A parent is entitled to the leave if he or she is employed or receives unemployment benefits and does not receive other forms of benefits. CSC can be used for sick days when a child is absent from preschool or school and the parent stays home from work. The leave can be used for children aged 11 years or younger and the reimbursement level is about 78 per cent, up to an income ceiling. With the ceiling, the level of reimbursement is capped at a certain income level that is tied to the consumer price index. Hence, all parents with incomes above the income ceiling get a flat rate of 78 per cent of the ceiling. In the sample of parents eligible for CSC in 2000 or 2010 analysed here, a third of the parents have incomes above the ceiling. Among fathers, the share is 49 per cent and among mothers the share is 18 per cent.

In addition to CSC, Sweden’s temporary parental leave scheme includes temporary leave in connection with the birth of a child or adoption, often called paternity leave (‘pappadagar’). This leave comprises ten days that may be used by the non-birth parent, usually the father, to stay at home following the birth of a child. The reimbursement is the same as for CSC.

Anyone who needs to stay home for an extended period to care for a family member or relative is entitled to care allowance. This is an alternative to CSC for parents of children with serious illnesses or disabilities. Hence, parents with seriously ill or disabled children are likely to make up a small share of the CSC-using parents in this study.

CSC was introduced in 1974, at the same time the gender-neutral parental leave scheme replaced the old maternity leave scheme. In stark contrast to the share of standard parental leave taken by fathers in the first decades of the new scheme (just a few per cent), the fathers’ share of all CSC days was 40 per cent in 1974 (Statistics Sweden, Citation2022a). This number decreased somewhat in the following decades, reaching its lowest point (32 per cent) in 1995, after which it started to increase slowly. In 2000, the first data point in the present study, fathers took 34 per cent of all CSC days. In 2010, the second data point in this study, this number had increased to 36 per cent and has since continued to increase, reaching 40 per cent in 2021.

During the period studied here (2000–2010), parents who used CSC took, on average, seven days per year. The average was six days per year for fathers and eight days per year for mothers. These numbers remained fairly consistent for many years and have only recently changed, with an increase in CSC use among fathers and mothers during the COVID-19 pandemic (Swedish Social Insurance Agency, Citation2012, Citation2023).

A large share of parents does not use CSC; for example, in 2010, almost 60 per cent of all parents of 0-11-year-olds did not use CSC (Swedish Social Insurance Agency, Citation2013). This number includes parents who may not need to use CSC, for example, parents whose partner used CSC, parents on parental leave and unemployed parents. Among employed parents, 56 per cent did not use any CSC, and this was more common among fathers (61 per cent) than mothers (51 per cent).

Although the female labour force participation rate in Sweden is almost as high as that for men, the labour market is structured in such a way that the need and ability to use CSC, and the consequences of leave use, likely differ between fathers and mothers. During the period studied here, about a third of all working women and about ten per cent of all working men worked part-time (Statistics Sweden, Citation2012, Citation2022a). Most of the part-time working men and women work long part-time hours (20–34 h per week). The share of working women who work part-time has since decreased to about 20 per cent in 2021 (Statistics Sweden, Citation2022a).

In terms of gender segregation, the Swedish labour market ranks in the middle in comparison to other European countries (Halldén, Citation2014). At the beginning of the period studied here, about half of all working women worked in the public sector. At the end of the period, a somewhat larger share worked in the private sector, and this share has since increased. During the entire period, a large majority of working men worked in the private sector. The most common industries among women are health care, welfare services and education and among men, financial activities, business services and production (Statistics Sweden, Citation2022b).

The unadjusted gender wage gap was 18 per cent in 2000 and decreased to about 14 per cent in 2010. By 2021, it had decreased further to 10 per cent (Swedish National Mediation Office, Citation2002, Citation2011, Citation2022). The gender wage gap adjusted for gender differences according to sector, work experience, seniority and occupational qualifications was about 13 per cent in 2000 and 11.5 per cent in 2010 (Boye et al., Citation2017).

Variation in CSC use by factors related to labour market work

In a descriptive survey of parents in the south of Sweden, parents cited their situation at work as an important factor in determining who will stay home when a child falls ill (Eek & Axmon, Citation2011). The situation on the day in question seemed to be the most important factor: the parent with the least pressing work tasks that day tended to take CSC (see also Unionen, Citation2018). The parent with the most flexible work and the one that was most easily replaced during the absence also tended to stay at home.

Even though parents say that working conditions are important (e.g. Eek & Axmon, Citation2011), analyses of CSC use have not studied specific working conditions. A couple of studies have used occupation as a proxy for working conditions. Boye (Citation2015) found that parents who worked in the same occupation shared CSC more equally than other couples, but that the similarity in occupations may not necessarily be the cause. Instead, it was likely unmeasured, time-invariant characteristics of these couples that accounted for equitable CSC use. Ichino et al. (Citation2019) found that (different-sex) couples adjusted the division of CSC according to a change in the opportunity cost of using leave. This adjustment differed depending on whether the change occurred for the man or the woman, and this result did not change when controlling for occupation. The results of these studies suggest that differences in occupations within couples do not explain gender differences in CSC use. The reason could either be that factors represented by occupation are not important, or that occupation does not work well as a proxy for working conditions in these studies.

There is variation in CSC use by wage, income and education, factors that correlate with working conditions (Magnusson, Citation2021). It is more common for parents with very low incomes and parents with incomes above the income ceiling to completely forego CSC (Swedish Social Insurance Agency, Citation2013). Often, the division of CSC between parents is analysed rather than the number of leave days each parent takes. The higher the wage of the father, the smaller the father’s share of CSC days (Boye, Citation2015). The reason for this may be something other than economic incentives related to wages, as the association between fathers’ wages and the share of CSC was not observed in a couple fixed effects regression. Eriksson (Citation2011) found that a change in the income ceiling did not result in the changes in CSC use among fathers and mothers that would have been expected if economic considerations were the most important factor in leave use. Furthermore, the father’s share of leave increases with an increase in the mother’s economic position in the couple, which is presumed to be associated with bargaining power (Amilon, Citation2007; Boye, Citation2015). Still, even in couples where the partners have the same annual income, mothers take a larger share of leave than fathers (Amilon, Citation2007).

The lower the parents’ level of education, the less likely they are to use any CSC in a year (Swedish Social Insurance Agency, Citation2013). Education may partly offset any influence of economic resources on CSC use, as the father’s share of CSC use increases with the father’s and the mother’s level of education (Eriksson & Nermo, Citation2010). Gender attitudes may be one reason that highly educated couples share CSC more equally (ibid.). The fathers’ share of leave tends to be larger if their level of education is lower than that of their partner (Amilon, Citation2007) and smaller if their level of education is higher than that of their partner (Amilon, Citation2007; Boye, Citation2015). Again, Boye (Citation2015) found that the association between relative education and fathers share of CSC use disappeared with couple fixed effects, so this association may be caused by other characteristics than relative educational level.

The present study fills an important gap in the literature by analysing survey data containing parents’ actual direct reports of working conditions and, using register data on income and use of CSC, the role working conditions and income play in explaining gender differences in whether and how many days are taken (for details, see Study purpose and analytical strategy and Data and analyses). Previous research suggests at least three types of working conditions could be important to CSC use: flexibility, time consuming work, and dependence between employer and employee. These are discussed below.

Flexibility

The ability to decide when and where to work could either facilitate the use of CSC, as the employer is not very dependent on the employee being present at specific times, or enable parents to care for a sick child without using formal leave. Parents state that job flexibility (Eek & Axmon, Citation2011) and the option to work from home (Unionen, Citation2018) are important considerations when choosing who will stay at home with a sick child. Unionen (Citation2018) showed that half of the white-collar employees in the private sector in Sweden who had the option to work from home usually did so instead of using formal CSC. Staying at home without taking CSC was even more common among employees with subordinates. Consequently, the most likely scenario may be that work flexibility in terms of time and space reduces the need to use formal leave.

There is a gender difference in access to flexible working conditions, either broadly defined (e.g. Magnusson, Citation2021) or defined as schedule flexibility (e.g. Chung, Citation2019). Female-dominated job posts, occupations and sectors (i.e. where more than 80 per cent of the work force is female) are the least flexible and gender-integrated job posts, occupations and sectors (i.e. with a roughly equal number of males and females) are the most flexible (e.g. Chung, Citation2019; Magnusson, Citation2021). Hence, the lower flexibility in female-dominated jobs may be one reason that mothers use more CSC than fathers.

Time-consuming work

Some positions in the labour market demand a high level of loyalty and availability (e.g. Acker, Citation1990). They are often qualified positions that come with expectations to work long hours, provide “face time”, go on frequent business trips, etc. These demands may be difficult to meet when employees also have childcare responsibilities, or employers may assume such difficulties and act by this assumption in organizational decisions (Goldin, Citation2014; Magnusson, Citation2010). Parents with such time-consuming working conditions may be less willing, or feel less able, to use CSC because of the difficulties it may cause at the workplace for themselves or others. When asked about the factors behind the use and division of CSC, it is common for parents to state that workload, the urgency of work tasks and the option to call in a replacement at work are important (Eek & Axmon, Citation2011; Unionen, Citation2018). When taking CSC, parents worry about the tasks that are not being done at work, and some feel that they are letting their work colleagues down by being absent (Eek & Axmon, Citation2011). A large proportion of white-collar workers report that they feel the need to work during CSC to decrease their workload when they return to work (Unionen, Citation2018).

The distribution of time-consuming working conditions is gendered. Studies from Sweden and elsewhere have shown that men go on more business trips (Borowski et al., Citation2018; Gustafson, Citation2006; Magnusson & Nermo, Citation2017), work more overtime, are more likely to have subordinates and have more subordinates compared to women (Magnusson & Nermo, Citation2017). Even within the same occupation (Grönlund & Öun, Citation2018), or occupations with similar prestige levels (Magnusson & Nermo, Citation2017), men’s jobs demand more in terms of constant availability and overtime. In Sweden, time-consuming work is least common in female-dominated occupations and most common in gender-integrated occupations (Magnusson, Citation2021). Fathers, in particular, are more likely than women and childless men to have jobs with time-consuming working conditions (Magnusson & Nermo, Citation2017). The fact that fathers are more likely to have time-consuming work could be one explanation for the lower use of CSC among fathers compared to mothers.

Dependence between employer and employee

In the early 2000s, Tåhlin (Citation2007) showed that a majority of employer-employee relations in Sweden are asymmetrical. About a quarter of employees see themselves as being dependent on their employer, and hence in a weak position, and about a third see themselves as being in a stronger position than their employer. Being in a strong position in relation to one’s employer could decrease a parent’s fear of negative repercussions when using CSC. The present study includes measures of the level of difficulty for employers to replace employees who leave their positions (i.e. employee replaceability) and the level of difficulty for employees to find another position that is comparable to their current position (c.f. Tåhlin, Citation2007).

Employee replaceability is influenced by the supply of job-relevant skills by other potential employees in the labour market (Tåhlin, Citation2007). On-the-job training is a more direct measure of the employee’s job-relevant skills that are likely to increase employee independence (Leuven, Citation2005; OECD, Citation2004; Tåhlin, Citation2007). Skills gained through on-the-job training are often transferable to other employers, while employer investment in the skills of the employee increases employer dependence on the employee. Long initial training periods are also indicative of a job’s complexity, and employees who are very familiar with a complex job may be hard to replace. A study of professionals in Sweden showed that employees in jobs with long initial training periods were more likely than other employees in the same occupation to perceive themselves as difficult to replace (Boye & Grönlund, Citation2018). Men were more likely than women to report a long initial training period and to perceive themselves as difficult to replace. The current study includes the initial training period required in the parent’s job as an additional measure of employee independence.

On the other end of the spectrum of employer-employee dependence, the employee is highly dependent on the employer. Parents who perceive themselves as easily replaced may be hesitant to use CSC for fear of being seen as unengaged or difficult, which could increase their risk of being replaced or passed over for promotions and salary increases. Temporary employment, a particularly clear case of employee dependence, is included in this study. This type of employment is more common among women than men (Statistics Sweden, Citation2022a).

In sum, men appear to have a generally stronger position in relation to their employer than women. If a strong position facilitates the use of CSC, this may offset any negative effects of other working conditions on fathers’ CSC use.

Study purpose and analytical strategy

The present study asks five questions. Based on previous research, it is suggested that different working conditions create different needs, opportunities and consequences in relation to CSC use and are associated with the likelihood of using CSC and the number of days used. A consequence of the gender-segregated labour market is that fathers and mothers often have different working conditions, and this may be one explanation for the gender difference in CSC use. On the one hand, the fact that fathers tend to have more flexible jobs may allow them to care for sick children without taking CSC (i.e. formal leave), and their more time-consuming work may make fathers less willing, or make them feel less able, to take leave. On the other hand, the stronger position among fathers in relation to employers may facilitate the use of CSC. This stronger position may partly offset any negative effects of other working conditions on leave use among fathers. It is also possible that working conditions have different effects on CSC use for fathers and mothers, i.e. working conditions and gender may interact. The first three research questions are:

Are there associations between CSC use and working conditions related to flexibility, time-consuming work and employer-employee dependence?

Are gender differences in CSC use related to gender differences in these working conditions?

Are associations between these working conditions and CSC use different for fathers and mothers?

To answer these questions, different types of working conditions are first included in regression analyses in a stepwise approach in order to analyse their associations with CSC use and to reveal the influence on the association between gender and CSC use. Second, interactions between working conditions and gender are analysed.

Previous studies have shown links between CSC use and economic resources but the patterns of associations have not always been what would be expected if economic considerations were the cause of the associations (see, e.g. Eriksson, Citation2011). This means that economic resources may (partly) act as a proxy for some other factors that are associated with CSC use. Working conditions may be among those factors. The fourth research question is:

| (4) | Do working conditions mediate an association between income and CSC use? | ||||

To answer this question, this study analyses the association between CSC use and annual income in order to reveal how much of this association remains with control for working conditions. Annual income is selected as the measure of economic resources because the reimbursement for CSC is based on income. Income may also be a proxy for other factors that are not controlled for in the present analyses, for example, gender norms and the norms and ideals of fatherhood and motherhood. As mentioned above, however, an advantage of analysing CSC is that the associations found are unlikely to reflect physiological aspects of early biological parenthood and norms and ideals connected to these specific aspects.

As many parents use no CSC in a year, the fifth research question is:

| (5) | Are there different patterns of associations between CSC, working conditions, income and gender for, on the one hand, the likelihood of using CSC and, on the other hand, the number of CSC days used among CSC-using parents? | ||||

To discriminate between the likelihood of using CSC and the number of CSC days used among CSC-users, a two-part model is used. The first part analyses the likelihood of using any leave among eligible parents. In the second part, the number of CSC days used by CSC-using parents is analysed. The first and second part follow the same analytical strategy, adding the same variables in a stepwise approach as described above.

Data and analyses are described in detail below.

Data and analyses

Data from the Swedish Level-of-Living Survey (LNU) enable a detailed study of how CSC use relates to working conditions and income. Data from 2000 and 2010 are pooled to get a sufficient sample size. Register data on the number of CSC days, annual income, etc. are linked to the survey data for the years studied. The studied sample includes men and women with children 11 years of age or younger in the household, i.e. children for whom parents can take CSC. All women and men included in the study were employed the week before the interview and received income from work or unemployment benefits during the year, hence, they were eligible for CSC. The measure of CSC use includes the ten days fathers usually use after the birth of a child. This significantly inflates CSC use among fathers in the year that a child is born. A total of 113 households where a child was born during the year are therefore excluded. One mother had used more than five times as many CSC days as the maximum number of days used by other parents (281 days as compared to 50). This case skews the results for women and is therefore excluded from the analysis. Respondents with missing information were also excluded, resulting in a sample size of 1,504 of which 747 (49.7 per cent) are men.

In the analysed sample, 43.8 per cent used no CSC in the year studied (). CSC use in the previous year can be analysed for the part of the sample that participated in 2010. This analysis (not shown but available on request) showed that among the parents who were eligible for CSC in both years but did not use any leave in 2010, 70 per cent did not use any leave in 2009 either. Among the CSC users in 2010, about 22 per cent did not use CSC in 2009. A total of 25 per cent used CSC in only one of the two years. The group of eligible non-users appears to be quite stable and a two-part model is therefore applied. The first part uses a Linear Probability Model, LPM, (the participation equation) to examine the likelihood of taking any CSC during the year. LPM is chosen over logistic regression, which is often used when the dependent variable is binary. LPM enables comparisons across groups as well as across models that include different independent variables, whereas such comparisons are problematic with logistic regression (Mood, Citation2010). The second part only includes parents who used CSC during the year and uses Ordinary Least Squares regression, OLS, (the level equation) to model the number of CSC days used. The first and the second part include the same steps, described below.

Table 1. Variable descriptions and descriptive statistics.

First, the associations between working conditions and CSC use and the gender difference in CSC use are analysed. To a model including gender and control variables, each group of working conditions was added in separate models, after which all working conditions were added simultaneously. As the separate models for groups of working conditions added very little to the understanding of the associations between gender, working conditions and CSC, only the models with gender and control variables and with the full set of working conditions are shown. The separate models for groups of working conditions are available as online supplementary material.

Second, the association between income and CSC use and the gender difference in CSC use are analysed in a model including income, gender and control variables, and then in a model adding all working conditions.

Third, gender differences in the associations between working conditions and income, respectively, and CSC are analysed by adding interaction terms between gender and working conditions, on the one hand, and income, on the other. Interactions were tested for the working conditions that were significantly associated with CSC in separate analyses of fathers and mothers (separate analyses available on request). Each interaction was analysed in a separate model. Only one interaction was statistically significant in each part of the two-part model, therefore, only the models that include these interaction terms are shown. In the first part, the analysis of interactions showed that the income-CSC association is curvilinear for mothers. Therefore, a quadratic term for income is added to a model before the interaction terms.

As LNU is a panel study, a part of the sample participated in both 2000 and 2010. Standard errors are therefore clustered at the individual level.

The response rate was 76.6 per cent in 2000 and 61.5 per cent in 2010. Weights are applied in all regressions to correct for non-response bias.

Variables

Descriptions of all variables included in the analyses can be found in .

The dependent variable in the first part (participation) of the two-part model is a dichotomous variable showing whether or not a parent used CSC during the year (2000 or 2010). The dependent variable in the second part (level) of the two-part model is the number of CSC days used during the year. Parents can use CSC for part of a day, and the measure captures net days, which means that a parent may have used, for example, 1.25 CSC days in a year.

Four different types of working conditions are measured. The three first are the types discussed above, i.e. working conditions related to flexibility, time-consuming work and dependence between employer and employee. The fourth type is practical circumstances that may enable or obstruct CSC use or make it unnecessary. The practical circumstances included are inconvenient working hours (e.g. working mainly evenings) and commuting time. Practical circumstances are included as they correlate with other working conditions and with CSC.

Apart from the measure of working hours flexibility included in the analysis, three more flexibility measures were tested: whether the respondent can run a private errand during the workday, whether it is important to keep time at the workplace and whether the respondent’s working time is logged by a time clock. These measures showed no association with CSC and were therefore excluded.

A measure of attitudes towards gender equality in childcare and housework was tested as an explanatory variable. It did not show any association with CSC use or influence associations between working conditions, income and CSC use. It was therefore not included in the final analyses. (These tests are available on request.)

The control variables were chosen to reflect the characteristics of the children in the household and the labour market-related characteristics of the respondents. There may be a correlation between illness in children and parents and to account for this, a control was included for parental sick leave absence in the initial analyses. As it did not show any association with CSC, it was excluded from the analyses presented here.

Results

Descriptive results

shows basic descriptive statistics for the full sample and for fathers and mothers. Results of significance tests of gender differences are shown in the last column. Among parents eligible for CSC who did not have another child during the year, 56 per cent used some CSC. This conceals a sizeable (and statistically significant) gender difference: 47 per cent of fathers and 65 per cent of mothers used some leave. The gender difference in the number of leave days used among those who used any leave is less pronounced, although still statistically significant: fathers used 6 days and mothers 7 days. It appears that the main gender difference in CSC use is not the number of leave days used, but the likelihood of using any leave.

It is apparent that fathers and mothers face significantly different conditions in a variety of aspects related to the labour market. As countless studies have shown, mothers, on average, receive a lower annual income than fathers. Mothers also tend to hold jobs with less flexibility: fewer mothers than fathers can decide when to start and end their workday.

Fathers tend to have more time-consuming work than mothers: they work more overtime, spend more nights away from home on business trips, and are more likely to have subordinates and have more subordinates. However, mothers and fathers are equally likely to be expected to work unpaid overtime.

Fathers appear to be less dependent on their employers than mothers. Fathers are more likely to state that it takes at least a year to learn to do their job reasonably well. This indicates that fathers are more likely than mothers to perceive that their jobs are complex and they may therefore be more likely to see themselves as valuable to the employer. Mothers are less likely than fathers to perceive that they are difficult to replace in the workplace. More mothers than fathers have temporary employment and hence a weak position in relation to the employer. Mothers are more likely to hold firm-specific human capital, but the gender difference is statistically uncertain (reaching the ten per cent significance level). No gender difference was observed in the ability to find a comparable position with another employer.

As for the practical circumstances, mothers are more likely to work inconvenient hours, but there is no noteworthy gender difference in commuting time.

Some differences were observed between fathers and mothers in the control variables. The youngest child in the households of mothers is somewhat older than the youngest child in the households of fathers. As expected, mothers have a higher level of education than fathers, are more likely to be employed in the public sector, work shorter hours and take more parental leave.

The variation in CSC by working conditions, income and gender

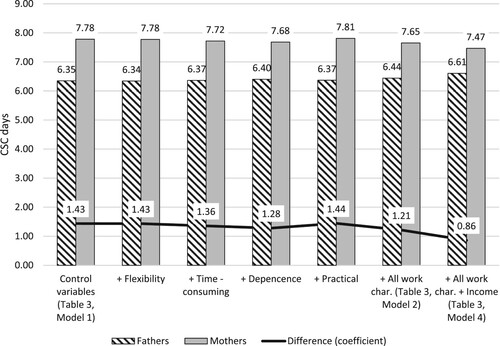

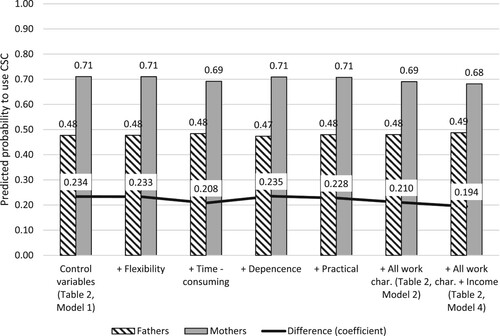

shows the results of the first part of the two-part model and shows the results of the second part. Results are shown for gender, working conditions and income. Full models including results for control variables and with all steps where groups of working conditions are added separately can be found in the online supplementary material. The results for gender differences shown in models that include different groups of working conditions are included in and . The bars in show the predicted probabilities for CSC use for fathers and mothers at the mean of all included variables. The bars in show the predicted number of CSC days for fathers and mothers who use any CSC at the mean of all included variables. The lines in and show the difference between fathers and mothers, i.e. the coefficient for the variable Woman.

Figure 1. Predicted probabilities to use CSC at the mean of included variables, first part (participation).

Table 2. The likelihood of using any CSC among eligible parents (first part) regressed on working conditions and income, LPM. Robust standard errors in parentheses.

Table 3. The number of CSC days used among CSC users (second part) regressed on working conditions and income, OLS. Robust standard errors in parentheses.

Gender differences in the way working conditions and income relate to CSC were analysed with interaction terms. Each interaction term was included separately (i.e. one interaction term per model). In and , models with significant interaction terms are shown (tables with non-significant interactions are available on request).

Looking first at the results of the first (participation) part in , Model 1, which includes gender and control variables only, the likelihood that a mother will use any CSC during the year is 23 percentage points higher than the likelihood that a father will use any CSC. As seen in , the predicted probability that a parent will use CSC is 71 per cent for mothers and 48 per cent for fathers. This is a larger gender difference than the uncontrolled difference (see ) and the reason is primarily the controls for working hours and parental leave: mothers have shorter working hours and a larger number of parental leave days, which are associated with a reduced likelihood of using CSC.

When working conditions are added in Model 2, no association is seen between flexible working hours and the likelihood of using CSC (this is also true if no other working conditions are included in the model; see online supplementary material). Associations are observed between CSC use and variables that measure different aspects of time-consuming work. Parents who frequently work overtime, have unpaid overtime, go on many overnight business trips or have subordinates are less likely to use CSC. Among the measures of employer-employee dependence, temporary employment, indicating a high dependence on the employer, is negatively related to CSC use. When examining practical circumstances, , Model 2 shows a lower likelihood of using CSC among parents who work inconvenient hours compared to standard working hours.

Model 3 includes gender, income and control variables and shows that the likelihood of using CSC decreases with income. With control for working conditions in Model 4, the income association is reduced by about a third but still significant. The association between income and the likelihood to use CSC is to some extent but not entirely caused by income acting as a proxy for working conditions. The associations between working conditions and CSC are largely unchanged with control for income. However, high income among parents who frequently work overtime may be one explanation for their lower likelihood to use CSC as this association is weakened in Model 4 compared to Model 2.

In Model 5, a quadratic term for income is added, and the model shows that the association between income and CSC use is not curvilinear. However, when interactions between gender and income and its quadratic term are added in Model 5, the picture changes. Among fathers, the likelihood of using CSC decreases with income. Among mothers, the likelihood to use CSC increases with income, but at a decreasing rate.

Looking once more at the gender difference in the likelihood of using CSC, this difference decreases by 2.4 percentage points (or 10.0 per cent) when working conditions are added in , Model 2 (compare the coefficient for Woman in Models 1 and 2). shows that adding only the measures for time-consuming work is enough to result in this kind of reduction and that gender differences in other working conditions do not contribute to the gender difference in the likelihood of using CSC. Adding income instead of working conditions in Model 3 results in a somewhat greater reduction of the gender difference compared to Model 1, 3.4 percentage points (14.6 per cent).

, Model 4 includes both working conditions and income. This reduces the gender difference by 3.9 percentage points (16.8 per cent) compared to Model 1 which includes only gender and control variables. The predicted probability of using CSC with working conditions and income controlled is 68 per cent for mothers and 49 per cent for fathers ().

shows the results of the second part of the two-part model, which models the number of CSC days used in a year by parents who used any leave. As is clear from the first part, there is selection on working conditions and income into using CSC. Compared to parents who are not included in the second part, parents who are included work less overtime, are less likely to have unpaid overtime, spend fewer nights away from home on business trips, and are less likely to have subordinates, temporary employment, to work inconvenient hours and to have a short or no commuting time. The fathers also have a lower average income (analyses of these differences are available on request). Consequently, the variation in these factors is lower in the group of CSC users compared to the full sample.

, Model 1 shows that when holding the control variables constant, mothers use 1.4 more CSC days than fathers in a year. The predicted number of days used by mothers with average values for all included variables is 7.8 days, while the corresponding number for fathers is 6.4 days (see ). This is a larger gender difference than what is observed without control variables (see ). The main reasons are the higher education level of mothers and the greater number of parental leave days mothers take compared to fathers, which are associated with a reduced number of CSC days.

, Model 2, which adds working conditions, shows no associations between CSC days and flexible working hours or time-consuming work. Parents in jobs that require long initial training, who are likely to have relatively complex jobs and a strong position in relation to the employer, use fewer CSC days than others and hence do not appear to use any leverage they may have to take more (formal) leave. Parents with firm-specific human capital, who may have difficulties applying their skills with another employer, use more leave. This may seem counterintuitive, but this association is weakened when controlling for income in Model 4 and hence may reflect the fact that parents with firm-specific human capital receive lower incomes. As for the practical circumstances, parents who work inconvenient hours are not only less likely to use any leave, as was shown in , they also use fewer leave days. The same is seen for parents with a short commute or no commute, whereas parents with very long commuting times use more leave days (however, the latter association only reaches the ten per cent significance level).

Model 3 includes income without control for working conditions and shows that the number of CSC days decreases with income. Control for working conditions in Model 4 does very little to the size of the income coefficient (it is reduced by 13 per cent). Hence, the association between income and CSC days cannot be attributed to income acting as a proxy for working conditions. Furthermore, controlling for income does not change the associations between working conditions and CSC days apart from the influence on the association between firm-specific human capital and CSC days mentioned above.

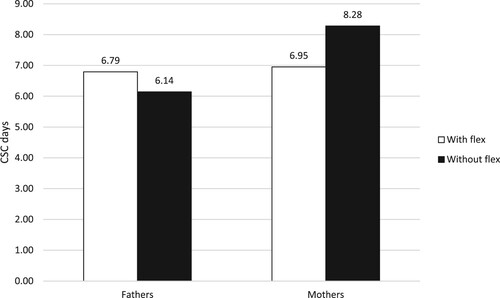

Model 5 adds an interaction between gender and flexible working hours, the one interaction that was statistically significant when interactions were tested. shows the predicted number of CSC days for fathers and mothers with and without flexible working hours at the mean of the rest of the included variables. There is no difference in CSC days between fathers according to working hours flexibility. In contrast, whereas mothers with flexible working hours use roughly the same number of CSC days as fathers, mothers without flexible working hours use significantly more days.

Figure 3. Predicted number of CSC days at the mean of included variables, second part (level); interaction between gender and working hours flexibility. Estimations based on , Model 5.

When differences between working conditions for mothers and fathers are considered in , Model 2, the gender difference in the number of CSC days is reduced by 0.2 days (15.5 per cent) (compare the coefficient for Woman in , Models 1 and 2). As can be seen in , the group of measures of employer-employee dependence is the biggest contributor to this reduction. Adding income instead of working conditions in Model 3 results in a greater reduction of the gender difference, 0,48 days (33.5 per cent) and the gender difference is significant only at the ten per cent significance level. The gender difference in income appears to contribute a great deal to the gender difference in CSC days.

When working conditions and income are added together in Model 4, the gender difference in CSC days is reduced by almost 0.6 days (40.1 per cent) compared to Model 1, and the gender difference is no longer statistically significant. The predicted number of days is 7.5 for mothers and 6.6 for fathers (). Gender differences in employer-employee dependence, specifically job complexity, and perhaps even more the gender income gap appear to be key factors in the gender difference in CSC days.

To summarize, first, the gender difference in CSC use appears to be caused in large part by a difference between fathers’ and mothers’ likelihood to use the leave, and to a smaller extent by a gender difference in the number of days used among CSC-using parents. Second, whereas differences between mothers and fathers in working conditions and income account for a small part of the gender difference in the likelihood to use any CSC, they appear to account for a large part, or even all, of the gender difference in the number of CSC days used by CSC users.

Discussion

Parents who stay home on CSC forgo market work to care for a sick child. This may have consequences for their wage development (Boye, Citation2019) and it may also have consequences in the workplace (e.g. Eek & Axmon, Citation2011; Unionen, Citation2018). Parents with different working conditions may therefore have different opportunities and needs when it comes to CSC use. As the labour market is structured by gender, gender differences in working conditions as well as in income may contribute to the gender difference in CSC use. This study shows that fathers are considerably less likely than mothers to use any CSC in a given year. Among parents who use CSC, fathers use fewer days than mothers, but this difference is less striking than the difference in the likelihood of using the leave at all. Both the likelihood of using CSC and the number of CSC days used among CSC-using parents are related to working conditions, but this relationship varies. The answer to the first and second research question is hence yes, there are associations between CSC use and working conditions, and the gender differences in CSC use are related to gender differences in working conditions. The answer to the fifth research question is also yes, the patterns of associations between CSC on the one hand and working conditions and income on the other hand differ depending on whether the likelihood of using CSC or the number of CSC days used is studied. The patterns of associations between CSC, working conditions, income and gender are discussed below.

The fact that fathers are more likely than mothers to be employed in time-consuming work positions, with more overtime, overnight business travel and supervisory responsibilities, accounts for part of fathers’ lower likelihood of using CSC. These working conditions may be hard to combine with childcare responsibilities without consequences either for the parents themselves or for their colleagues and managers in the workplace (c.f., Eek & Axmon, Citation2011; Goldin, Citation2014; Magnusson, Citation2010; Unionen, Citation2018). Fathers with these working conditions are more likely than other fathers to have found ways to never stay at home on formal leave, and the explanation is not working hours flexibility (because this is controlled for in the analysis). They may use other forms of flexibility such as the possibility to work from home, or other persons such as the children’s mother may take care of children who are sick. Notably, with time-consuming work, other working conditions, income, education and other family and labour market factors controlled, a large gender difference in the likelihood of using CSC remains.

Among parents who use CSC, the group of working conditions related to the employer-employee relationship accounts for a part of the gender difference in CSC days. Fathers tend to experience a relatively strong position in relation to their employer, but they do not seem to use any of the leverage that they may have due to a strong position in the employer-employee relationship to be able to use more CSC days; in fact, the opposite is true. The working condition that is related to CSC days and the gender difference in CSC is initial training, which indicates job complexity. More direct measures of the employer-employee relationship, such as employee replaceability and the possibility to find an equivalent job with another employer, are unrelated to CSC use. Hence, the reason that fathers in jobs with long initial training use fewer leave days may not be a strong position in relation to the employer but other factors related to the experience of having a complex job. Note that these fathers do use CSC, but they seem to either stay at home without using formal leave or forgo caring for a sick child more often than other fathers.

The ability to decide when to start and end the working day either facilitates the use of CSC or makes the use of formal leave unnecessary. The latter seems to be the case in the group of CSC-using parents, but there is a gender difference. Fathers and mothers with flexible working hours use the same number of CSC days, all else being equal. Among parents who do not have flexible working hours that allow them to stay at home with a sick child without using CSC, mothers are more likely than fathers to make caring for a sick child possible by staying at home using CSC, thereby taking the consequences such as a reduced income. More mothers than fathers lack flexible working hours, still, a majority of mothers and fathers have this flexibility. The gender difference in flexibility is not substantial enough to contribute significantly to the average gender difference in number of CSC days. The answer to the third research question, whether the associations between working conditions and CSC are different for fathers and mothers, is that they almost never are, with flexible working hours being the one exception.

One reason that fathers use less CSC than mothers may be related to financial aspects, as fathers earn more on average than mothers, and the parent and/or family may face a bigger financial loss when they take CSC. Previous studies of the gender difference in CSC use in Sweden have shown that CSC is associated with the absolute and relative economic resources of the parents, but this does not fully explain the gender difference (e.g. Amilon, Citation2007; Boye, Citation2015). Some of the results of previous studies suggest that economic considerations may not be the only cause behind the associations between income and CSC use (Amilon, Citation2007; Boye, Citation2015; Eriksson, Citation2011). Income may act as a proxy for other factors, and the present study tests whether working conditions are among these factors. The results corroborate previous findings by showing that the number of CSC days used by parents decreases with increasing income. In addition, the results show that the likelihood of using any leave decreases with income for fathers and increases with income for mothers. One reason for this gender difference may be that mothers are more likely to be found in the lower part of the income distribution and fathers are more likely to be in the higher part. This means that the general tendency among parents with low incomes not to use any leave (Swedish Social Insurance Agency, Citation2013) influences the results for mothers more than fathers, and the tendency among high-income parents not to use leave (ibid.) influences the results for fathers more than mothers.

The fact that fathers earn higher incomes than mothers explains a part of the gender difference in the likelihood of using any CSC and appears to be particularly important for the gender difference in the number of CSC days used. Importantly, when working conditions are considered, the association between income and the likelihood of using CSC is partly reduced whereas the association between income and CSC days is marginally influenced. Hence, the associations are not fully caused by income acting as a proxy for working conditions. On the contrary, income differences between fathers and mothers appear to be important for the gender difference in CSC. The answer to the fourth research question, whether working conditions mediate an association between income and CSC use, is hence that it partly does when it comes to the likelihood of using CSC but not when it comes to the number of CSC days used. Furthermore, the associations between working conditions and CSC use are affected to a very small extent when income is considered; Income and working conditions appear to a large extent to relate to CSC independently of each other.

All in all, the results of this study show that working conditions and income explain a small part of the rather large gender difference in the likelihood of using any CSC, while they explain a large part of the rather small gender difference in the number of CSC days used among all CSC-using parents. Hence, something other than labour market factors such as working conditions and income appears to contribute to the gender difference in the likelihood of using any leave. For example, gender construction may operate first and foremost through the likelihood of using any CSC, rather than through the number of CSC days used by parents who use the leave. A measure of attitudes towards gender equality was tested here but had no explanatory power and this may be because it does not measure gendered norms and ideals related to fatherhood and motherhood specifically.

The lack of information on the ideals of fatherhood and motherhood among the studied parents is a limitation in this study. However, the fact that CSC use is the target of the study means that norms and ideals connected to early biological parenthood, such as breastfeeding practices, which may influence studies of standard parental leave, are unlikely to influence the results of this study. In other words, the results may be influenced by norms and ideals on gender, motherhood and fatherhood but they are not likely to be influenced by physiological aspects of early parenthood and norms and ideals directly linked to these physiological aspects. Another limitation is that individual fathers and mothers, not couples, are analysed due to limitations in both available information and sample sizes. Information on couples would enable the analysis of the division of CSC use, as well as the interplay between fathers’ and mothers’ working conditions and income.

Despite the above limitations, the results of the present study advance the knowledge of the mechanisms behind gender differences in childcare. Working conditions and income appear to be important explanations for why CSC-using fathers forgo market work to care for children for fewer days in a year compared to mothers. However, neither working conditions nor income to any great extent explain why fathers are much less likely than mothers to use any leave. These results indicate that labour market factors such as working conditions and income play an important role in the degree of involvement among fathers who opt in to participating in these types of care tasks, but we need to identify other explanations than gender differences in the analysed labour market factors to explain why some fathers opt out.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (43.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Katarina Boye

Katarina Boye is an associate professor of sociology at the Swedish Institute for Social Research (SOFI), Stockholm University, Sweden, and director of the Swedish Level-of-Living Survey. She studies paid and unpaid work and gender with a special focus on gainful employment, parental leave, childcare and housework, and the consequences for men and women in different types of households.

Notes

1 SEK 1= Euro 0.09, USD 0.10 (December, 2023). Annual income is measured in SEK 10,000 in the multivariate analyses. A quadratic term is added to models where this specification best fits the data.

2 This indicates a high expectation of employee availability that is compensated for by the normal salary.

3 A quadratic term for working hours is included in the multivariate analyses.

References

- Acker, J. (1990). Hierarchies, jobs, bodies: A theory of gendered organizations. Gender & Society, 4(2), 139–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124390004002002

- Alsarve, J., Boye, K., & Roman, C. (2016). The crossroads of equality and biology. The child’s best interests and constructions of motherhood and fatherhood in Sweden. In D. Grunow & M. Evertsson (Eds.), Couples’ transitions to parenthood: Analysing gender and work in Europe (pp. 79–100). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Amilon, A. (2007). On the sharing of temporary parental leave: The case of Sweden. Review of Economics of the Household, 5(4), 385–404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-007-9015-0

- Antón, J.-I., Grande, R., Muñoz de Bustillo, R., & Pinto, F. (2023). Gender gaps in working conditions. Social Indicators Research, 166(1), 53–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-03035-z

- Bergqvist, C., & Saxonberg, S. (2017). The state as a norm-builder? The take-up of parental leave in Norway and Sweden. Social Policy & Administration, 51(7), 1470–1487. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12251

- Borowski, S. C., Naar, J. J., Zvonkovic, A. M., & Swenson, A. R. (2018). A literature review of overnight work travel within individual, family and social contexts. Community, Work & Family, 22(3), 357–383. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2018.1463970.

- Boye, K. (2015). Can you stay home today? Parents’ occupations, relative resources and division of care leave for sick children. Acta Sociologica, 58(4), 357–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699315605161

- Boye, K. (2019). Care more, earn less? The association between taking paid leave to care for sick children and wages among Swedish parents. Work, Employment and Society, 33(6), 983–1001. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017019868138

- Boye, K., & Grönlund, A. (2018). Workplace skill investments – An early career glass ceiling? Job complexity and wages among young professionals in Sweden. Work, Employment and Society, 32(2), 368–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017017744514

- Boye, K., Halldén, K., & Magnusson, C. (2017). Stagnation only on the surface? The implications of skill and family responsibilities for the gender wage gap in Sweden, 1974–2010. The British Journal of Sociology, 68(4), 595–619. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12252

- Chung, H. (2019). ‘Women’s work penalty’ in access to flexible working arrangements across Europe. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 25(1), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959680117752829

- Eek, F., & Axmon, A. (2011). Yrkesarbetande småbarnsföräldrar – arbetsförhållanden, arbetsplatsklimat och ansvarsfördelning i hemmet. Report no. 13/2011. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, Lund University.

- Eriksson, H. (2011). The gendering effects of Sweden’s gender-neutral care leave policy. Population Review, 50(1), 156–169. https://doi.org/10.1353/prv.2011.a433541

- Eriksson, R., & Nermo, M. (2010). Care for sick children as a proxy for gender equality in the family. Social Indicators Research, 97(3), 341–356. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9505-y

- Fenstermaker Berk, S. (1985). The gender factory. The apportionment of work in American households. Plenum Press.

- Goldin, C. (2014). A grand gender convergence: Its last chapter. American Economic Review, 104(4), 1091–1119. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.104.4.1091

- Grönlund, A., & Öun, I. (2018). In search of family-friendly careers? Professional strategies, work conditions and gender differences in work-family conflict. Community, Work & Family, 21(1), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2017.1375460

- Gustafson, P. (2006). Work-related travel, gender and family obligations. Work, Employment and Society, 20(3), 513–530. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017006066999

- Halldén, K. (2014). Könssegregering efter yrke på den svenska arbetsmarknaden 2000-2010. In A. Kunze & K. Thorborn (Eds.), Yrke, karriär och lön – kvinnors och mäns olika villkor på den svenska arbetsmarknaden. Forskningsantologi till Delegationen för jämställdhet i arbetslivet, SOU 2014:81 (pp. 49–75). Fritzes.

- Ichino, A., Olsson, M., Petrongolo, B., & Skogman Thoursie, P. (2019). Economic incentives, home production and gender identity norms. IZA Discussion Paper, 12391.

- Leuven, E. (2005). The economics of private sector training: A survey of the literature. Journal of Economic Surveys, 19(1), 91–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0950-0804.2005.00240.x

- Magnusson, C. (2010). Why is there a gender wage gap according to occupational prestige? An analysis of the gender wage gap by occupational prestige and family obligations in Sweden. Acta Sociologica, 53(2), 99–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699310365627

- Magnusson, C. (2021). Flexible time – but is the time owned? Family friendly and family unfriendly work arrangements, occupational gender composition and wages: a test of the mother-friendly job hypothesis in Sweden. Community, Work & Family, 24(3), 291–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2019.1697644

- Magnusson, C., & Nermo, M. (2017). Gender, parenthood and wage differences: The importance of time-consuming Job characteristics. Social Indicators Research, 131(2), 797–816. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-016-1271-z

- Mood, C. (2010). Logistic Regression: Why we cannot do what we think we can do, and what we can do about it. European Sociological Review, 26(1), 67–82. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcp006

- OECD. (2004). Employment outlook.

- Statistics Sweden. (2012). På tal om kvinnor och män. Lathund om jämställdhet 2012. Statistics Sweden, Population Statistics Unit.

- Statistics Sweden. (2022a). På tal om kvinnor och män. Lathund om jämställdhet 2022. Statistics Sweden, Population Statistics Unit.

- Statistics Sweden. (2022b). Arbetsmarknadssituationen för befolkningen 15-74 år. AKU 2022. Statistics Sweden, Social Statistics and Analysis.

- Swedish National Mediation Office. (2002). Avtalsrörelsen och lönebildningen 2021. Medlingsinstitutets årsrapport.

- Swedish National Mediation Office. (2011). Vad säger den officiella lönestatistiken om löneskillnaden mellan kvinnor och män 2010?.

- Swedish National Mediation Office. (2022). Löneskillnaden mellan kvinnor och män 2021.

- Swedish Social Insurance Agency. (2012). Utvecklingen av tillfällig föräldrapenning. Svar på regeringsuppdrag, 2012-06-05, Dnr. 005510-2012.

- Swedish Social Insurance Agency. (2013). Föräldrar som inte vabbar. Social Insurance Report, 2013:6), Försäkringskassan Analys och prognos.

- Swedish Social Insurance Agency. (2023). Socialförsäkringen i siffror. Försäkringskassan.

- Tåhlin, M. (2007). Class clues. European Sociological Review, 23(5), 557–572. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcm019

- Unionen. (2018). Vobba 2018. Totalrapport hela riket. Novus.

- West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H. (1987). Doing gender. Gender & Society, 1(2), 125–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243287001002002