ABSTRACT

Collective labour agreements are an understudied yet key aspect of flexible work policies, which are crucial resources for workers in combining work, family and other life domains. Despite a rich comparative work-family literature on flexible work arrangements at the company and national levels, little attention has been given to those negotiated collectively. Evidence on this topic is needed because such agreements can complement low levels of provision or even compensate the absence of company or national-level arrangements, ultimately defining their access. We contribute in filling this gap by conducting a cross-sectoral comparative exploration of collectively bargained provisions of flexible work arrangements in Spain and the Netherlands. We examine the clauses of 209 agreements using unique collective bargaining data from WageIndicator (2021). The analyses illustrate two important aspects of collectively bargained ‘family-friendly’ provisions. First, how differences in national baseline legislation shape opportunity structures for collective innovation around flexible work arrangements. Second, how sectoral variations appear to be primarily influenced by the representation of workers in high-skilled jobs, particularly when supported by high union density, rather than the share of female workers. We discuss the implications of these findings for workers’ work-family reconciliation and future work-family research.

1. Introduction

Flexible work arrangements (FWAs; e.g. telework and flexible working hours) have become widely available under the growing complexity of labour markets and the pluralization of working time patterns (i.e. deviating from the ‘standard working time’ of eight-hour work days in a five-day workweek (Hildebrandt, Citation2006)). Such arrangements can help employees adapt their (paid) work in order to combine it with other activities and responsibilities, such as leisure and caring for others (Chung & van der Lippe, Citation2018). As family life courses continue to become more complex and unpredictable (Van Winkle, Citation2020), the need for flexibility in combining work and family is likely to grow. FWAs have paradoxical effects, however (Chung, Citation2022), leading to increased self-exploitation by blurring the boundaries of work and private life that can amplify gender and class inequalities. Gendered effects of FWAs include the reinforcement of traditional gender roles (Chung, Citation2022): Among men, the use of FWAs tends to increase self-exploitation because they are more inclined to work long hours in order to fulfil traditional ideas of being an ideal worker. Among women, it increases because they are subject to use FWAs to fulfil societal expectations that presume them to be the main responsible for housework and childcare independently of their employment situation. Class effects are evidenced in the worsened labour market positions for workers in lower socio-economic positions, which can exacerbate class-based inequalities in health and wellbeing (Kossek & Lautsch, Citation2018; Perry-Jenkins & Gerstel, Citation2020).

Current work-family studies of FWAs focus primarily on cross-national and organizational-level inequalities in individual access to FWAs. Extant literature shows significant cross-country differences in FWA access, often attributed to the generosity of family policies (Chung, Citation2018; Korpi et al., Citation2013) and cultural factors (Kassinis & Stavrou, Citation2013). FWA provision at the company level can vary due to firm size (den Dulk et al., Citation2013), managerial discretion (Brescoll et al., Citation2013; Kelly & Kalev, Citation2006), and the proportion of women in the company (Chung, Citation2022). FWA access is also stratified across occupations (Kossek & Lautsch, Citation2018), and is usually higher among highly-educated employees, managers and professionals (Fuller & Hirsh, Citation2019; Glass & Noonan, Citation2016). With rare exceptions (e.g. den Dulk, Citation2001; Yerkes & Tijdens, Citation2010), however, there is no information about the extent to which collective agreements impact FWA provision and access and what this means for work-family reconciliation.

Although individual-level data provides evidence of potential inequalities in access to FWAs, these findings have yet to be supported by analyses of FWAs agreed upon in collective agreements. This absence is problematic because we have an incomplete empirical picture of FWAs and their (potential) paradoxical effects. Alongside statutory and company provision of FWAs, collective agreements can expand FWA provisions, ultimately defining their access (Chung & Tijdens, Citation2013) and thus the ability of workers to use such arrangements to reconcile work and family. A clearer overview of FWAs in collective agreements can also provide better empirical understanding of sectoral differences that otherwise remain masked by national level, flexible work policy classifications or employer-based analyses. Moreover, such analysis can potentially shed new light on gender and class differences in FWA access, generating an understanding of the gap between FWA statutory provision and actual usage in practice (Cooper & Baird, Citation2015; Kelly & Kalev, Citation2006).

This study sets out to provide much-needed initial evidence on this topic by answering the following questions: To what extent do countries differ in the provision of FWAs in collective agreements? To what extent do such provisions vary across sectors? The contribution to the work-family literature is twofold. Using the WageIndicator Collective Bargaining Agreement Database (Ceccon & Medas, Citation2022), a unique, comprehensive database on collective agreements, this article provides an in-depth exploratory analysis of collectively bargained FWAs in Spain and the Netherlands, including unprecedented detailed sectoral information on the availability and type of FWAs. It further makes a theoretical contribution by considering potential mechanisms behind the provision of FWAs, developing these arguments for hypothesis testing in future work-family research. Drawing on the work-family flexibility literature and the equality bargaining literature (i.e. the study of labour unions’ influence on work-life rights and policies that favour gender equality (Baird et al., Citation2014; Heery, Citation2006; Kirton, Citation2021)), it offers theoretical insights on potential opportunity structures favouring collectively bargained FWAs across countries and sectors. We account for the structure of collective bargaining systems and sector-specific employee characteristics, namely gender and job skill-level. These insights are used to inform the debate on FWAs as a key work-family resource for employees.

The analysis compares two countries where access to formal work-family resources for many employees is heavily influenced by collective agreements (Brega et al., Citation2023): Spain and the Netherlands. The Netherlands relies greatly on collective bargaining practices for social arrangements, in particular given wide-scale extension of such agreements in many sectors (Trampusch, Citation2006). FWAs are characterized by detailed national statutes regulating the basic provision of and access to flexible working, while mandating social partners to amend such regulations via collective agreements (Boehmer & Cabrita, Citation2016). Spain similarly relies heavily on collective bargaining agreements, also for FWAs, but in contrast to the Netherlands, Spanish national-level legislation is mostly absent, leaving FWAs to be agreed upon in collective bargaining processes. The country-level and cross-sectoral descriptive analysis therefore provides empirical insights needed for further theorizing on FWA provision and future empirical research on the paradoxical effects of flexible working.

2. Flexible work arrangements: a matter of contention

FWAs are often a key work-family resource for many employees. Nonetheless, what precisely constitutes FWAs varies widely across the literature (Chung & van der Lippe, Citation2018). We follow the literature in broadly defining flexibility as encompassing a diverse set of arrangements, namely (1) flexible working hours (i.e. the ability to choose from a pre-defined set of schedules or to vary start/end times); (2) telework (working from a location different to the usual workplace, including the home); (3) extending leave provisions in a flexible manner (e.g. returning to work following maternity leave on a part-time basis); and (4) changes in work-status (from full-time to part-time and vice versa). We purposely exclude part-time work from the analysis as the definition of this non-standard working time arrangement varies extensively in terms of working hours, its level of social protection, and its (in)voluntary nature (Nicolaisen et al., Citation2019).

Collectively bargained FWAs must necessarily be understood within a multi-level framework due to their provision at different and often simultaneous levels. At the national level, legislation typically establishes baseline statutory arrangements, at least in the form of a right to request (Hegewisch, Citation2009). Subsequently, companies can facilitate or restrict access to such arrangements, as well as supplement them (Chung & Tijdens, Citation2013). Furthermore, collective agreements play a crucial role by potentially transposing national FWA statutory provisions to specific workplace contexts, enhancing mandated policies, or negotiating arrangements where no national legislative framework exists (Dickens, Citation2000; Ollier-Malaterre, Citation2009). In short, collective agreements can complement or even compensate for insufficient public and organizational FWA provisions (Trampusch, Citation2006).

Some consider that although collectively provided FWAs can help employees balance different spheres of life (i.e. be employee-friendly), this balance is continuously at risk from employer-driven flexibilization (Hildebrandt, Citation2006).Footnote1 Employees’ interest in improving their work-family reconciliation is generally at odds with employers’ interests in discretionally organizing production processes to keep up with a so-called on-demand economy (e.g. through the adjustment of working hours to meet market demands or the flexibilization and extension of service and operating times (Fleetwood, Citation2007)). When FWAs are driven by employer interest, the negative consequences for employees (e.g. fluctuating schedules and increased overtime) tend to intensify, particularly for low-wage workers (Crocker & Clawson, Citation2012; Gregory & Milner, Citation2009a), with the potential to increase the tension between responsibilities at home and at the workplace (Kim et al., Citation2019).

The way in which company initiatives for FWAs and collective bargaining complement each other depends, among others, on the specific country context and dynamics between employers and trade union representatives. While in some cases, companies can proactively design and implement FWAs and unions subsequently complement them through collective bargaining agreements, in other cases, unions can be the driver for innovation on such issues. In any case, unions play a significant role in ensuring that FWA policies adequately meet the needs and preferences of the workers they represent, with union presence mattering for the adoption of family-friendly policies, including FWAs (Hogarth et al., Citation2003; MacGillvary & Firestein, Citation2009; Ravenswood & Markey, Citation2011). The presence of recognized unions also reduces the likelihood of employers attributing sole responsibility to employees for managing their work-life balance (Bryson & Forth, Citation2011). Disentangling whether employers or unions are the prime driver of FWA provisions is beyond the exploratory nature of this paper. Rather, in the following section, we discuss potential drivers associated with cross-country and cross-sectoral variation in collective bargaining provision of FWAs.

3. Drivers of collectively bargained flexible work provisions

Collective bargaining is the policy arena that is most sensitive to the concrete requirements of workers and employers. In that context, FWAs constitute a space for dispute of conflicting (but not necessarily misaligned) interests between workers’ wellbeing and employers’ discretion in the organization of production processes. A priori it is unclear whether one might expect the presence on FWAs to be higher or lower in relation to the proportion of organized labour (union density). On the one hand, a higher proportion of union-represented workers can increase bargaining power; that is, higher leverage to affect the incidence and value of benefits through collective bargaining (Budd & Mumford, Citation2004). On the other hand, higher bargaining power might not be reflected in greater initiatives to negotiate work-life reconciliation arrangements, as unions have traditionally focused such power on pay bargaining over other aspects of job quality (Bryson & Green, Citation2015) and FWAs have not traditionally been part of collective bargaining agendas (Gregory & Milner, Citation2009b). Yet previous research has shed light on relevant mechanisms that may drive differences in collective provision across countries and between sectors. For the current analysis, we can categorize them respectively into two theoretical concerns: opportunity structures and collective voice. We further divide the voice issue into two principles identified in the literature, namely need and equity (Lambert & Haley-Lock, Citation2004). Often, the principle of need is related to employees’ interest, and the equity principle is equated to FWAs implemented for performance-oriented goals, thus employer-driven (Chung, Citation2022).

First, scholars have identified that legislation (state intervention) can produce opportunity structures that promote union innovation in policies and practices through collective bargaining agreements (Heery, Citation2006; Kirton, Citation2021). Opportunities for the negotiation of complementary or additional FWA provisions can be facilitated or hindered by baseline statutory provision and the room collective bargaining relationships give for further negotiation (Berg et al., Citation2013; Gregory & Milner, Citation2009b; Ravenswood & Markey, Citation2011). Public policy in the form of FWA legislation provides the foundation from which complementary or additional provisions can be negotiated, as minimum entitlements offer a lever for collective bargaining (Brochard & Letablier, Citation2017; Dickens, Citation2000). Yet minimal statutory legislation is not necessarily disadvantageous, as previous research has found more provisions in collective agreements when there is weak legislation for family-friendly policy (Budd & Mumford, Citation2004). National statutory regulations may matter in different ways for the public and private sector. The landmark study by den Dulk (Citation2001) showed, for example, that even in the private sector, national legislation can stimulate union interest and encourage some employers to lead by good practice. Thus FWAs may be negotiated in the private sector just as often as in the public sector, despite the reputation of the public sector as ‘family-friendly’ (Heery, Citation2006).Footnote2 The collective bargaining systems in which these collective agreements are conducted is also relevant, as collective bargaining taking place at levels higher than the company can be advantageous for including FWAs (den Dulk et al., Citation2013). In contrast to company-level bargaining, sectoral negotiations provide capacity for a broad comparison of employment conditions across workplaces (Heery, Citation2006), and to counter strong pressure from employers towards unfavourable conditions (Grimshaw et al., Citation2017; Seeleib-Kaiser & Fleckenstein, Citation2009). Moreover, if the FWAs under negotiation are costly, sectoral bargaining can provide a financial buffer, as the costs would be borne by all employers rather than an individual employer put at a cost disadvantage compared to its competitors. Notwithstanding, (additional) collective agreements at the company level could facilitate the tailoring of sector-specific FWAs, as the workplace is where employees and their managers bring negotiated arrangements to life (Cooper & Baird, Citation2015).Footnote3

Second, inclusion of FWA policies in collective bargaining agreements can vary depending on the characteristics of the workforce such agreements represent. According to the representational role of unions, voicing members’ interests, policies must be needed or considered beneficial by a critical number of workers in order to be pursued (Berg et al., Citation2013; Brochard & Letablier, Citation2017). Hence, the feminization and the skill level of the labour force are decisive. From a principle of need (Gregory & Milner, Citation2009b), FWAs would more likely be important for female workers because women shoulder most of the responsibility for household and childcare tasks and face severe constraints in balancing work, care and private life (Gerstel & Clawson, Citation2014). Hence, female employees may be willing to trade off monetary benefits for benefits that are family-friendly (Harbridge & Thickett, Citation2003), such as FWAs. The representation of female workers has proven to be important in the pursuit of this type of provisions in collective agreements (Gregory & Milner, Citation2009b; Ravenswood & Markey, Citation2011; Rigby & O’Brien-Smith, Citation2010), but not always definitory (Brochard & Letablier, Citation2017).Footnote4 Recent empirical evidence suggests that gender diversity in the workforce is most favourable to collective bargaining on work-life balance issues (Bruno et al., Citation2021). However, some have suggested that collective bargaining agendas are not always receptive to their members’ work-family concerns (Gregory & Milner, Citation2009a). As trade unions have been historically male-dominated organizations that endorsed a gender-based division of roles related to earning income and childcare (Brochard & Letablier, Citation2017; Haas & Hwang, Citation2013), provisions related to work-life balance are often associated with ‘women’s issues’ and de-prioritized compared to wages under a ‘male norm’ of employment (Gerstel & Clawson, Citation2001; Kirton, Citation2021). Another issue that might explain a marginal presence of FWA clauses in collective agreements is that this agenda is often driven by business concerns (Fleetwood, Citation2007), thus seen by unions as a removing protective rights through employer-led flexibility (Kirton & Greene, Citation2006). Additionally, employers might resist negotiating FWAs in feminized sectors due to financial concerns, as a large share of their employees are likely to make use of them.

From an equity principle (i.e. compensations are unequally distributed, but based on the level of contributions; Lambert & Haley-Lock, Citation2004), FWAs would more likely be available to those employees who will bring the greatest benefit to the firm through improved performance results, such as employees in positions requiring high skill levels whose increase in productivity is more profitable (Brescoll et al., Citation2013; Chung, Citation2018; Chung & Tijdens, Citation2013; Ortega, Citation2009). Likewise, sectors that rely heavily on skilled labour may have higher bargaining power than others, because the difficulty of replacing employees in high-skilled jobs might lead employers to favour work-family policies to accommodate their demands to ensure retention (Chung & van der Lippe, Citation2018), especially after life-changing events like childbirth (Skorge & Rasmussen, Citation2021). Moreover, employers may expect take-up rates to be limited to a select group of employees, and thus see FWAs as relatively inexpensive. Previous research found that the inclusion of FWAs in collective agreements varies depending on the occupation of the workforce (Budd & Mumford, Citation2004), and is heavily influenced by the receptiveness of employers who are persuaded that FWAs are profitable (Berg et al., Citation2013). In contrast, it could be argued that unions from labour intensive sectors (where most workers do low-skilled jobs) have reason to actively resist flexible working practices in collective agreements (Fleetwood, Citation2007). In such sectors, working from a location other than the usual workplace is rare, but opening and operating times often exceed standard work weeks, shift work is common, and costs are often cut by operating lean core crews of workers and relying on on-call workers when needed. Hence, FWAs might further reduce the plannability and reliability of working time.

Admittedly, it should be noted that within sectors, the type of FWA included in collective agreements is likely to vary according to their adequacy and feasibility (e.g. in sectors where remote work may not be feasible due to the nature of the work, their collective agreements may have fewer clauses related to teleworking). While we include a description of the different type of FWAs included per sector, thoroughly explaining within-sector differences is beyond the scope of this paper. Prior to delving into the analysis, the following section provides an overview of the Dutch and Spanish institutional contexts, highlighting their respective baseline FWA statutory provisions and collective bargaining structures.

4. The Netherlands and Spain: statutory provision and room for collective bargaining of flexible work arrangements

Baseline statutory FWA provisions differ between Spain and the Netherlands. At the national level, FWAs are typically provided as a procedural right to ask for alternative working arrangements, or a ‘right to request’ (ILO, Citation2019). This is visible in Dutch legislation, which has regulated the provision and encouraged employers to make FWAs available for about two decades (Arbeidstijdenwet, Citation2010; Wet flexibel werken, Citation2016). National-level legislation covers multiple arrangements, such as schedule flexibility, the temporary reduction of working hours, and teleworking. Going beyond typical right to request legislation, virtually all workers in the Netherlands have the right to adjust their working hours if employers cannot show it is against business interests. However, these arrangements can only be accessed by employees with a tenure of at least 26 weeks (with the same employer), within firms who employ 10 or more workers. In smaller firms, employers and employees are expected to make individual arrangements. In contrast, broad guidelines for limited FWAs in Spain are offered in legislation only since the last decade. The adjustment of working time is not covered by national legislation as a set of arrangements for workers to reconcile work with other spheres of life, but is tied to different types of leave for childbirth, adoption, care for children or ill family members, or breastfeeding (Real Decreto Legislativo Citation2/Citation2015). More recent legislation declared that workers have the right to request FWAs for work-life balance (Real Decreto-Ley Citation6/Citation2019; Art. 34). However, such legislation only marginally improves existing Spanish leave schemes to care for dependents, emphasizing that they are an individual and non-transferable right. Moreover, important sectoral differences are evident in Spain. In contrast to private sector employees, public sector employees are guaranteed some working time flexibility to adapt their working schedule to parenting needs (e.g. to school hours) (Meil et al., Citation2020). Legislation on telework, passed in 2012, is limited to jobs related to the intensive use of new technologies (Ley Citation3/Citation2012). Following the COVID-19 pandemic, additional legislation stipulates when workers who carry out remote work on a regular basis can demand that their employers provide the necessary conditions for remote work (Ley Citation10/Citation2021).

Both the Dutch and Spanish approaches to FWA legislation foresee that statutory provisions will be subject to further negotiation between employer and employee representatives (Boehmer & Cabrita, Citation2016). They are thus classified as ‘negotiated working time regimes’ (OECD, Citation2019). But the application of these approaches differs in reality. Detailed national statutory provision of FWAs in the Netherlands mandates social partners to amend such regulations via collective agreements (Wet flexibel werken, Citation2016; Art. 2.15). In the Dutch case, existing statutory standards are, in principle, supported by workers’ and employers’ associations because the social partners are consulted on national legislation through the Social and Economic Council (i.e. a tripartite institution that is decisive in nearly all labour market related legislation).Footnote5 In contrast, Spanish national-level FWA legislation is minimal, leaving FWAs to be (voluntarily) agreed upon in collective bargaining processes. If the schedule, place and distribution of work deviate from the guidelines established by the Spanish legislation, they should be agreed upon in collective bargaining processes (with either single or multiple employers) (Real Decreto-Ley 6/2019; Real Decreto Legislativo 2/2015, Art. 34.8). In both countries, when collective agreements or employee representation are absent, the terms of FWAs are relegated to individual negotiations between the company and the employee who requests them.

As FWA regulations are to be negotiated via collective agreements, it is relevant that collective bargaining predominantly takes place at the sectoral level in both the Netherlands and Spain, but they differ in other aspects of their bargaining systems. First, Spain allows less room for firm-level agreements than the Netherlands. Sectoral agreements in Spain predominantly set framework conditions and coverage is extended by default to all employees (i.e. under the erga omnes principle). Although firm-level agreements can apply less favourable terms for employees than those negotiated in higher-level agreements since a reform in 2012 inverted the favourability principle, exemptions remain limited (OECD, Citation2019).Footnote6 Dutch sector-level agreements also set broad framework conditions but leave ample room for the negotiation of detailed provisions at the firm-level, complementing or deviating from higher-level minimum or standard terms.Footnote7 Simultaneously, the extension of sectoral collective agreements to entire sectors (including employees/firms not affiliated with or having signed the agreement) is common in the Netherlands, and exemptions are rare outside large firms (Hijzen et al., Citation2019).Footnote8 Second, coordination between bargaining units is strong in the Netherlands but weak in Spain. In the Netherlands, the metal sector sets the targets and others follow (i.e. pattern bargaining). In Spain, peak level organizations either set some guidelines or define intra-associational goals to be followed when bargaining at lower levels, and agreements tend to deal with complementary issues at different levels. Consequently, Dutch workers are often covered by non-nested collective agreements (sector or firm) (Jansen, Citation2021), whereas Spanish workers are often covered by agreements at simultaneous levels.

In sum, national legislation sets the statutory level of FWA provision that collective agreements can specify or complement in collective bargaining processes, where workforce key characteristics are likely to make a difference.Footnote9 However, without detailed data on the negotiation processes behind collective agreements, the direction of these drivers is unclear, meaning it is not possible to establish causality in the current paper. We focus instead on exploring the potential of these drivers given the absence of detailed comparative empirical evidence to date.

5. Data and methods

5.1. Data

The article uses data from the 2021 version of the WageIndicator Collective Bargaining Agreement Database (Ceccon & Medas, Citation2022). The dataset contains a total of 1,546 coded collective agreements from 62 countries and 40 Transnational Company Agreements. The agreements are classified as multi-employer (for simplicity, treated as sector-level agreements) or single-employer (company level collective agreements).Footnote10 The complete text of the collective agreements is annotated and coded in a web-based platform by trained coders following a structured coding scheme, aided by natural language processing techniques that flag relevant clauses in the agreements (Tijdens et al., Citation2022). The WageIndicator data collection strategy consists of completing its database retroactively over time, so that as the full texts of agreements become available through corresponding labour authorities and/or social partners, they are collected and coded. Hence, data are not necessarily representative of all countries in the dataset. The 2021 version of the dataset contains in total 108 Spanish and 101 Dutch collective agreements (see ), covering 46% of the 173 regular (legally recognized) sectoral agreements active in the Netherlands in 2020 (CAO-afspraken, Citation2022),Footnote11 and 28% of the 171 collective agreements with a scope higher than the company level active in Spain in 2020 (Estadísticas de Convenios Colectivos del Trabajo, Citation2023).Footnote12 The coverage of company level varies in the dataset from 4% in the Netherlands to 8% in Spain. This data is sufficiently robust to allow for robust sector-level analyses in the two countries (see Table A1 in Annex for a detailed calculation of margins of error). The Spanish full text collective agreements were collected through the State Archives of Collective Bargaining Agreements (Published in the Official State Gazette), and the Spanish trade union Confederation of Workers (CC.OO.) (Medas & Ceccon, Citation2021). The Dutch full text collective agreements in the dataset were acquired through the Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment and with the help of the social partners (Jansen, Citation2021).Footnote13

Table 1. Sample characteristics.

The 209 agreements in the analytic sample were mostly signed between 2017 and 2019. The Spanish agreements coverage ranged from 2008 up to 2025, with an average duration of 3.2 years. The coverage of the Dutch collective agreements included varied from 2013 up to 2023, with an average duration of 1.9 years, except for 4 agreements without an operative end date (indefinite duration).Footnote14 Although some agreements are valid until 2025, they were all negotiated prior to the COVID-19 pandemic (up to April 2020).

For the purposes of our analysis, collective agreements were aggregated into five sectors following the industry-standard classification system (NACE revision 2.0, 1 digit), with a further classification of the service sector following Eurostat’s definition of knowledge-intensive services (OECD, Citation2021): Manufacturing; Construction (including water supply, sewerage and waste); Knowledge-intensive services (including a variety of financial, professional, technical and scientific activities); Commerce & other services (including retail, hospitality and transport); and Education, healthcare services and public administration (see Table A2 in Annex for a detailed classification).

Our analysis of FWA clauses in each agreement is based on the previous identification of FWAs in the database (through the coding process outlined above). FWA data are classified by the options are provided: 1 ‘Extended leave’ (extending leave provisions in a flexible manner); 2 ‘Telework’; 3 ‘Work from home;’ 4 ‘Flexible hours’; 5 ‘Change work-status’ (between full-time and part-time) (Ceccon & Medas, Citation2022). Despite existing conceptual differences between telework and working from home (Kurowska, Citation2018), these two categories are combined for simplicity in the interpretation of the results. Thus, telework refers to working from a location different to the usual workplace, including the home.

5.2. Analytical strategy

We conducted an exploratory analysis in order to describe and summarize the data, using contingency tables and appropriate nonparametric statistical tests according to the nature of the variables and the lack of a normal distribution. Chi-Square Tests of Independence were performed to assess the association between categorical variables (e.g. country and the presence of FWA clauses in a collective agreement). When a category was expected to have values lower than 5, Fisher’s exact tests were performed to assess the relationship between categorical variables. Kruskal–Wallis tests were conducted to determine significant differences between groups on a continuous variable (e.g. sectors and union density). The purpose of these tests was to consistently evaluate which country and sector differences were substantial, thus they do not offer proof of causality. The analysis was divided into two parts. First, it examined cross-country differences in the inclusion of FWA clauses in collective agreements between Spain and the Netherlands. The second part focused on cross-sectoral differences in the inclusion of FWA clauses in collective agreements within each country. Both parts explored differences between the level of bargaining (single or multi-employer) and the type of FWAs included in the collective bargaining agreement (flexible working hours; telework; and change in work status).

6. Results

6.1. Flexible work arrangements in collective agreements: between-country differences

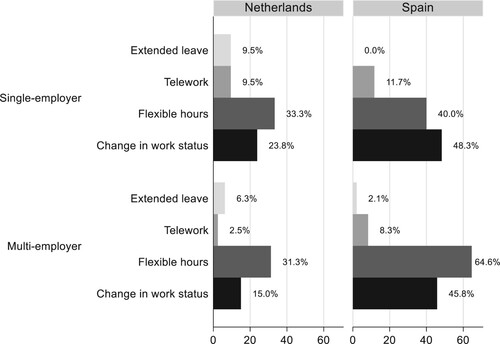

The Spanish and Dutch collective agreements in the sample differed in the inclusion of FWA clauses, the level of negotiation of such clauses, and the type of arrangement covered. A statistically significant association between country and the presence of FWA clauses in a collective agreement (X2(1, 201) = 8.833 (p = .003)) corroborated that FWA clauses were more likely to be found in Spanish collective agreements than in Dutch ones. Of the 108 Spanish agreements, more than 70 per cent had clauses on FWAs, compared to 50 per cent of the 101 Dutch agreements. suggests that multi-employer agreements were more likely to include FWA clauses than single-employer agreements only in Spain (X2(1, 105) = 8.699 (p = .003)). In the Netherlands, FWAs were equally included across levels of bargaining (X2(1, 96) = 0.001 (p = .975)).

Table 2. Collective agreements with clauses on flexible work arrangements, by level of bargaining.

Not all types of FWAs were equally included in Spanish and Dutch collective agreements.Footnote15 Flexible working hours and the (protected) possibility to make changes in work status (from full-time to part-time and vice versa) were by far the most common type of FWA included in collective agreements. A significant association between country and the presence of clauses on flexible working hours (X2(1, 201) = 7.412 (p = .006)), and between country and the presence of clauses on changes in work status in a collective agreement (X2(1, 201) = 21.339 (p = .000)), showed that both flexible working hours and changes in work status were significantly more likely to be present in Spanish than in Dutch collective agreements. Changes in work status are part of the statutory provision on flexibility in both countries (see section 2 above). However, the ability to change one’s work status from full to part-time and vice versa might be a matter for collective bargaining because requests for an increase in working hours are more often rejected by employers than requests for a decrease in hours (den Dulk & Yerkes, Citation2020). A significant association between country and the presence of clauses on telework in a collective agreement at a 10% CI level (X2(1, 201) = 2.891 (p = .089)) showed that telework clauses were also significantly more likely to be present in Spanish agreements. Telework is hardly regulated by Spanish legislation. This differs from the Netherlands, where legislation encourages telework, and a relatively high share of workers use telework arrangements, which could help explain cross-country differences in the presence of such clauses.Footnote16 The extension of leave provisions to be taken in a flexible manner were among the less common FWAs included in collective agreements, and significantly more likely to be present in Dutch than in Spanish collective agreements (X2(1, 201) = 5.273 (p = .022)). Low prevalence of such FWAs is likely related to high costs. Cost-sharing mechanisms are generally established in statutory leave provision, and extending leave provisions through flexible take-up often has to do with more weeks of paid leave or higher wage replacement, both of which come at a direct cost to the employer.

The type of FWAs included in an agreement () was independent of the level of negotiation in both countries, except for the presence of flexible working hours clauses in Spain, which was significantly more likely to be present in multi-employer agreements (X2(1, 105) = 7.395 (p = .007)), but not so in the Netherlands (X2(1, 96) = 0.000 (p = .999)). These results suggest that the same types of FWAs tend to be negotiated at both levels of negotiation.

Figure 1. Collective agreements with clauses on flexible work arrangements, by type of arrangement and level of bargaining.

In sum, Spain and the Netherlands show significant differences in the inclusion of FWA clauses in collective agreements negotiated pre-COVID covering the period 2008–2025. These differences could reflect varying opportunity structures for collective-based innovation in work-life balance issues that existing public policy and state intervention provide. Higher provision of FWAs through collective agreements in the Spanish case could be levered by the minimum entitlements provided by legislation (Dickens, Citation2000).

6.2. Flexible work arrangements in collective agreements: sectoral differences

As a first step in the cross-sector analysis, we examined the sectoral composition of the workforce in Spain and the Netherlands (). In both countries, the gender composition, job-skill composition and union density is significantly different across sectors. Kruskal–Wallis tests indicate significant differences across sectors in the share of female workers in the Netherlands (X2(4, 101) = 78.681 (p = .000)) and in Spain (X2(4, 108) = 51.291 (p = .000)); in the share of workers in high-skilled jobs in the Netherlands (X2(4, 101) = 67.132 (p = .000)) and in Spain (X2(4, 108) = 64.210 (p = .000)); and in trade union density in the Netherlands (X2(4, 101) = 40.707 (p = .000)) and in Spain (X2(4, 108) = 77.106 (p = .000)).

Table 3. Sectoral workforce composition and trade union density.

The manufacturing and construction sectors represent just over 20 per cent of the labour force in each country. Although they are both male-dominated industries (with more than three-quarters of male workers) with relatively high unionization rates, manufacturing has a higher proportion of workers in high-skilled jobs. Knowledge-intensive services account for about a quarter of the labour force, while commerce and other services represent over one-third. Across the sectors analysed here, knowledge-intensive services and commerce and other services are the sectors with the lowest trade union density. With nearly the same share of male and female workers, these are gender-balanced sectors. Contrary to knowledge-intensive services, commerce and other services have the lowest share of workers in high-skilled jobs across sectors. The education, healthcare and public administration sector is marginally larger in the Netherlands than in Spain, representing approximately 30 per cent of the labour force. With around 70 per cent female workers, this sector is female-dominated and has a large proportion of workers in high-skilled jobs, as well as high union density.

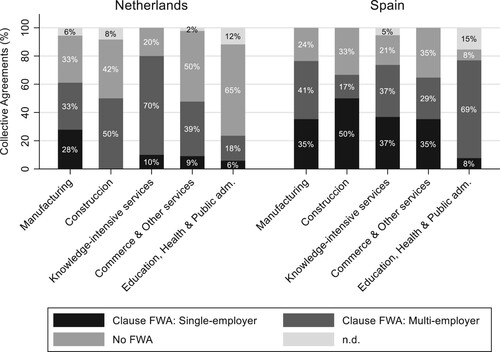

This distinct sectoral composition is partially reflected in our exploratory analysis. All sectors contained FWA clauses, but sectoral differences were substantial only in the Netherlands. Fisher’s exact tests showed a statistically significant association between sector and the presence of FWA clauses in a collective agreement in the Netherlands at a 10% CI (two-tailed p = .085) and a non-significant one in Spain (two-tailed p = .459).

In the Netherlands, agreements from knowledge intensive services were the most likely to include FWA clauses, followed by agreements from manufacturing (80% and 61% respectively, ). In the former, FWAs were mostly based in multi-employer agreements, and in the latter they were equally based on single and multi-employer agreements (). Collective agreements in construction and commerce and other services included a very similar proportion of clauses on FWAs (58% and 48% respectively, ). In the construction sector, all collective agreements containing FWA clauses were multi-employer agreements, but they were similarly based on single and multi-employer agreements in commerce (). Agreements from the education, healthcare and public administration sector were least likely to include FWA clauses (23%, ), and FWAs were mostly based in multi-employer agreements ().

Figure 2. Collective agreements with clauses on flexible work arrangements, by sector and level of bargaining.

Table 4. Collective agreements with FWA clauses, by sector.

These results imply that FWAs might be comparatively easier to negotiate in sectors that combine a large proportion of workers in high-skilled jobs with either a male-dominated or gender-balanced composition. Although the inclusion of FWA clauses was not significantly different across sectors in Spain, we observe the same tendencies as in the Netherlands with the exception of the sector aggregating education, health and public administration. In contrast to the Netherlands, in Spain, this sector appears very likely to include FWA clauses.

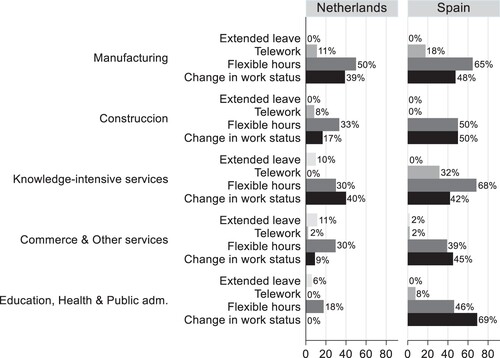

We also found differences in both countries regarding the type of FWA clauses included in collective agreements across sectors (), but only for two types of arrangements. In the Netherlands, the inclusion of clauses on changes in work status (from full – to part-time and vice versa) was significantly different across sectors at a 10% CI level (two-tailed Fisher’s exact p = .075), and again most likely to be found in the knowledge intensive services and manufacturing sectors. The presence of clauses on changes in work status in a collective agreement was not significantly associated with the sectors in Spain (two-tailed p = .153). In Spain, the inclusion of clauses on telework was significantly different across sectors (two-tailed Fisher’s exact p = .003), with the highest likelihood observed in knowledge-intensive services, followed at a distance by the manufacturing sector. The inclusion of clauses on telework was not different across sectors in the Netherlands (two-tailed Fisher’s exact p = .254).

Figure 3. Collective agreements with clauses on flexible work arrangements, by sector and type of arrangement.

We note that collective agreements in the Dutch education, healthcare and public administration sector only contained clauses on flexible working hours and extending leaves in a flexible manner (). Moreover, commerce and other services is the only sector in both countries to have agreements with clauses on all four types of FWAs (). It could be argued that companies in the commerce sector would be especially interested in negotiating FWAs (e.g. benefiting from extended opening times during the evenings/weekend). However, since this type of practice tends to reduce plannability and working time reliability, it would also make sense for workers to actively resist such flexible working practices.

The cross-sectoral variation found in the Netherlands in relation to the FWA clauses included in collective agreements as well as the type of FWA likely to be included suggests that in the Dutch case, a high proportion of female workers in a sector is in and of itself insufficient to drive FWA inclusion in collective agreements. Rather, the skill composition of the sector appears to play a vital role.

7. Conclusion

Despite the great number of work-family studies analysing FWAs, most comparative analyses focus on how company-level provisions complement national-level policies, without sufficiently recognizing the role of collective agreements. Their role is also often disregarded when providing evidence of gender and class inequalities in access to FWAs, with research mainly based on individual level data. This article attempts to fill these gaps and contribute to the work-family literature by comparing the inclusion of clauses on FWAs and their type (i.e. flexible working hours, telework, changes in work status from full-time to part-time, and flexibility in returning from leave), in over 200 collective agreements from Spain and the Netherlands. The article examines whether the inclusion of FWAs in collective agreements varies between countries in relation to the opportunity structures that legislation produce for union innovation in policies and practices (Heery, Citation2006; Kirton, Citation2021); and across sectors according to the role of unions in voicing workers’ interests (Berg et al., Citation2013; Brochard & Letablier, Citation2017) ─the expectation that the collective provision of FWAs will depend on how needed and/or useful they are according to sectoral workforce composition (the so-called principles of need and equity).

At the country level, results show that Spain and the Netherlands differ in the provision of FWAs in collective agreements. FWA clauses are more often found in Spanish than in Dutch collective agreements. These results are in line with previous research finding fewer provisions in collective agreements when there is strong legislation for family-friendly policy (Budd & Mumford, Citation2004; Gregory & Milner, Citation2009b). The limited baseline statutory provision of FWAs in Spain may suggest an emerging opportunity structure for their collective innovation. Additionally, Spanish multi-employer agreements more often include FWAs than single-employer agreements, a difference not identifiable in the Dutch case. However, there is an indication that similar types of arrangements are negotiated at both levels. Given that collective bargaining predominantly takes place at the sector level in both countries but additional negotiation at the firm level varies, this finding could be reflecting different scenarios. For example, employers with company-level agreements who have opted out from sectoral agreements in the Netherlands might be negotiating similar topics to those forgone at the sector level. In Spain, a country known to suffer from disorganized and overlapping bargaining structures, with a labour reform (in 2012) that allowed for inverse favourability (Sánchez-Mira et al., Citation2021), the negotiation of similar topics could reflect the struggle of company level collective agreements to prevent the deterioration of arrangements (previously) negotiated at the sectoral level.

Across sectors, results show significant variation in the inclusion of FWA clauses (and their type) in collective agreements only in the Netherlands. Agreements from knowledge intensive services (a gender-balanced sector with a large share of workers in high-skilled jobs and low union density) and manufacturing (a male-dominated sector with a medium share of workers in high-skilled jobs and high union density) were the most likely to include FWAs (over 60% of the agreements). FWA clauses were least likely to be found in the education, health and public administration sector (a female-dominated sector with a large share of workers in high-skilled jobs and high union density). Commerce and other services is the only sector with collective agreement covering all four types of FWAs.

These results indicate little support for a needs-driven provision of FWAs in collective agreements, whereby FWA clauses would be most expected in sectors representing a large proportion of female workers, as women more often use such arrangements to shoulder the double-burden of care and paid work (Gerstel & Clawson, Citation2014). The share of female workers in a sector appears to be insufficient for making a difference in the collective provision of FWAs, even with relatively high union density. Unions could be operating under a traditional male employment model and disregarding FWAs relevance (Kirton, Citation2021). Moreover, even if FWAs are perceived as helpful for female participation in employment, their negotiation might be resisted by employers due to high costs. However, it should be noted that most of education, healthcare and public administration falls within the public sector in the Netherlands. The public sector traditionally provides work-life balance arrangements more than other sectors, reinforcing the idea of the ‘ideal employer’ (Heery, Citation2006). Moreover, the Netherlands has been known for offering very high support for FWAs through state regulations in the last decades (den Dulk & Groeneveld, Citation2013). In this regard, it could be argued that since FWA provision is somehow covered in this sector, the remaining needs that collectively bargained arrangements could address are low, giving more credit to a needs-based explanation. These findings might help to understand contrasting individual level results, whereby some suggest that there are no substantial differences between men and women in their access to flexible working schedules and telework (Chung, Citation2019a; Ortega, Citation2009; Swanberg et al., Citation2005), and others suggest limited access in female-dominated workplaces (Chung, Citation2019b; Magnusson, Citation2021). Our results also support recent conclusions of gender diversity in the workforce being advantageous for the collective negotiation of a variety of FWAs (Bruno et al., Citation2021).

Rather than supporting the idea of needs-based collective provision, the cross-sectoral results mostly support the idea of equity-driven provision of FWAs. With the exception of the aforementioned public sector in the Netherlands, our results show that the higher the share of workers with a high-skilled job in a sector, the more likely FWA clauses are to be included, particularly if combined with high union density. This could indicate that skill level confers higher bargaining power in negotiating FWAs. Notwithstanding, it can be argued that employers may be inclined to accommodate the demands of workers in high-skilled jobs due to the scarcity of their skills, ensuring retention and productivity levels. In other words, employers may be more willing to negotiate FWAs because they expect to benefit from them. These results are in line with individual level studies showing that FWA access is usually higher among highly-educated employees, managers and professionals (Fuller & Hirsh, Citation2019; Glass & Noonan, Citation2016); and that workers in a high-skilled job are more likely to have access to flexible working schedules and telework (Chung, Citation2019a, Citation2022). The evidence further supports the idea that the gap observed in microdata might not be due to lower awareness of FWA provision among workers in a low-skilled job, but rather lack of access. Although country level provisions may exist, such provisions do not seem to be operationalized in collective agreements covering these workers.

Our results point to potentially important avenues for further research, providing nuance to existing evidence on gender and class inequalities in access to FWAs based on individual level data. But given their exploratory nature, this analysis of which collective agreements include FWAs and cross-national and cross-sectoral differences between Spain and the Netherlands is only a first step. Future research could, for example, delve into the content of FWA clauses, helping to highlight potential ambiguity in FWAs clauses and whether they are employer – or employee-friendly and what these differences mean for workers’ abilities to reconcile work with family or other spheres of life. Detailed content analysis could also expand our knowledge of how collective agreements potentially improve statutory provisions, providing greater insights into the extent to which collective agreements truly provide employees with protective resources for reconciling work and family. A further limitation of this study is the restricted number of cases given the data available, which meant a reliance on descriptive analysis and non-parametric tests to assess between and within-country differences. The ongoing inclusion and coding of more agreements in the WageIndicator dataset (Ceccon & Medas, Citation2022) will offer future work-family researchers opportunities for additional statistical analysis and increase the representativeness of such studies. The greater availability of data, in particular across time, would also allow for greater attention in unpacking causality to increase our understanding of the drivers of flexible work provisions in collective bargaining.

Notwithstanding these limitations, our findings provide much-needed initial cross-national and cross-sectoral evidence on the potential of FWAs to complement statutory or organizational flexibility arrangements, or compensate for their absence (den Dulk, Citation2001; Trampusch, Citation2006; Yerkes & Tijdens, Citation2010). On their own, the presence of FWA clauses in collective bargaining agreements does not ensure positive outcomes for workers’ wellbeing. However, embedding FWAs within collective agreements uniquely has the potential to develop provisions that protect employment conditions while expanding opportunities to combine work and caregiving responsibilities for a diverse array of workers.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (28.2 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the participants of the paper session ‘Collective Approaches to Work and Family: The Role of Unions and Associations’ at the Work, Family Researcher’s Network conference in New York (June 2022) and the participants of the online international workshop organized by Minerva: Laboratory on Diversity and Gender Inequality (November 2022). We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions that contributed to improve the quality of the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Carla Brega

Carla Brega is a doctoral researcher in Interdisciplinary Social Sciences at Utrecht University. Her research focuses on gender and class inequalities in the reconciliation of paid work and care responsibilities, and the impact of industrial relations and labour market policies on these inequalities in a comparative perspective.

Janna Besamusca

Janna Besamusca is Assistant Professor of Interdisciplinary Social Science at Utrecht University. She is a labour sociologist interested in work and family issues, (minimum) wages and working hours. She has conducted research into decent work in low wage sectors, wages in collective bargaining, self-employment and motherhood, and the effects of work-family policies on mothers’ labour market position.

Mara Yerkes

Mara Yerkes is Full Professor of Comparative Social Policy in relation to Social Inequalities at Utrecht University, the Netherlands, and Research Associate at the Center for Social Development in Africa at the University of Johannesburg, South Africa. Her research centres on comparative social policy (including national and local welfare state policy and industrial relations), social inequalities (related to work, care, communities and families, in particular relating to gender, generations, and sexual orientation) and their interplays. Yerkes is PI of the European Research Council (ERC) project CAPABLE, a comparative study on gender inequalities in work-life balance in eight European countries.

Notes

1 Hence, distinctions between external flexibility (i.e., related to the organization of production, including employment and hiring practices like outsourcing) and internal flexibility (i.e., related to labour organization in the workplace, such as the organization of the working day and schedule adjustability) are common.

2 A detailed public/private sector comparison is beyond the scope of this paper. See, for example, Yerkes and Tijdens (Citation2010), for a comparison using the Dutch case.

3 Sectoral collective bargaining might allow for additional firm level negotiations that modify higher-level agreements. Further negotiations at the firm level could favour FWAs that complement standards reached at the sector level, especially if the so called ‘favourability principle’ applies (i.e., lower level bargaining can only improve upon the terms and conditions concluded for employees at a higher level of bargaining (OECD, Citation2019)). However, there might be mechanisms for lower-level agreements to be (totally or partially) exempted from higher-level agreements, thus making them mutually exclusive.

4 The presence of female union office-holders and negotiators has also been proven important to promote gender equality in collective agreements (Dickens, Citation2000). However, there is no available data on the gender of the negotiating parties of each collective agreement analysed in this paper, therefore outside the scope of this study.

5 As a result of such consultations, statutory provisions often include a standard division of the costs of FWAs (e.g., leave paid at 70 per cent wage replacement where 30 per cent of the cost is borne by employees, 30 per cent by employers, and 40 per cent by the state).

6 Employers may opt out of collective agreements with the consent of employee representatives, or they may submit the issue to arbitration before a public, tripartite body. Since the 2012 reform, limited (large) firms have opted out from sectoral agreements (OECD, Citation2019).

7 The application of the favourability principle in the Netherlands is decided between bargaining parties (OECD, Citation2019).

8 However, exemptions from the corresponding sectoral agreement are common for firms that negotiate at the firm level, since a company-level agreement constitutes grounds for exemption.

9 It is possible that the proportion of highly-skilled and female workers within each sector would bring about differences in the inclusion of FWA clauses that could remain masked at the sector level (e.g., by occupation).

10 The distinction between company and sectoral level agreements, which is straightforward in the Netherlands, is more complex in Spain. In Spain, it is possible to find company-level agreements and agreements ‘with a scope higher than the company’ (Estadísticas de Convenios Colectivos del Trabajo, Citation2023). These agreements include regional, provincial and interprovincial agreements (meaning that they affect an autonomous community, province or group of provinces in a certain sector of activity). While this regional bargaining also plays a role in Spain, the issues negotiated tend to be harmonized across regions in the same sector, thus not affecting the predominant sectoral level of bargaining (OECD, Citation2019).

11 In 2020, the Netherlands had 658 regular (legally recognized) collective agreements, of which 485 were company-level and 173 sectoral agreements. Regarding the coverage of the registered agreements, of the 5.9 million employees covered by a collective agreement, only 500,000 were covered by a company agreement and around 5.2 million by a sectoral collective agreement (CAO-afspraken, Citation2022).

12 In Spain, there were 928 regular collective agreements in 2020, of which 757 were company agreements and 171 with a scope higher than the company (Estadísticas de Convenios Colectivos del Trabajo, Citation2023). Regarding the coverage of the registered agreements, of the more than 1.6 million workers directly affected by a collective agreement, only around 163,000 were covered by a company agreement and around 1.5 million by a higher level agreement (Estadísticas de Convenios Colectivos del Trabajo, Citation2023). Due to the extension of the latter type of agreement, all employees in a given sector would be covered by the corresponding agreement.

13 Both in Spain and in the Netherlands, (multi-employer) collective agreements must be submitted to the labour authority for registration and implementation. Company-level collective agreements, however, are not always freely accessible to third parties.

14 All agreements included in the WageIndicator dataset were of varying duration. This means that the negotiated period of time for which the collective agreement regulates (some aspects of) employment conditions differed from one agreement to another. It also means that collective agreements may have been agreed upon in different years, and that they did not necessarily cover sectors or firms uninterruptedly over time (as agreements are not necessarily consecutive).

15 Table not shown for space purposes, available from the authors upon request.

16 A recent draft bill from the House of Representatives in the Netherlands, known as the ‘Work where you want’ act (‘Wet werken waar je wilt’) intended to amend the Flexible Working Act to guarantee employees’ right to work from home or a different place than the usual workplace by treating these requests the same as, for example, the request to reduce or expand working hours. The bill was, however, rejected by the Senate in September 2023.

References

- Ley 3/2012, de 6 de julio de medidas urgentes para la reforma del mercado laboral. BOE-A-2012-9110. https://www.boe.es/eli/es/l/2012/07/06/3/con.

- Ley 10/2021, de 9 de julio, de trabajo a distancia. BOE-A-2021-11472.

- Real Decreto Legislativo 2/2015, de 23 de octubre, del texto refundido de la Ley del Estatuto de los Trabajadores. BOE-A-2015-11430. https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rdlg/2015/10/23/2/con.

- Real Decreto-Ley 6/2019, de 1 de marzo, de medidas urgentes para garantía de la igualdad de trato y de oportunidades entre mujeres y hombres en el empleo y la ocupación. BOE-A-2019-3244. https://www.boe.es/eli/es/rdl/2019/03/01/6/con.

- Arbeidstijdenwet. (2010). Ministerie van Sociale Zaken en Werkgelegenheid. https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0007671/2010-10-01

- Baird, M., McFerran, L., & Wright, I. (2014). An equality bargaining breakthrough: Paid domestic violence leave. Journal of Industrial Relations, 56(2), 190–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185613517471

- Berg, P., Kossek, E. E., Baird, M., & Block, R. N. (2013). Collective bargaining and public policy: Pathways to work-family policy adoption in Australia and the United States. European Management Journal, 31(5), 495–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2013.04.008

- Boehmer, S., & Cabrita, J. (2016). Working time developments in the 21st century: Work duration and its regulation in the EU European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. https://doi.org/10.2806/888566

- Brega, C., Briones, S., Javornik, J., León, M., & Yerkes, M. (2023). Flexible work arrangements for work-life balance: A cross-national policy evaluation from a capabilities perspective. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 43(13/14), 278–294. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-03-2023-0077

- Brescoll, V. L., Glass, J., & Sedlovskaya, A. (2013). Ask and ye shall receive? The dynamics of employer-provided flexible work options and the need for public policy. Journal of Social Issues, 69(2), 367–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12019

- Brochard, D., & Letablier, M. T. (2017). Trade union involvement in work–family life balance: Lessons from France. Work, Employment and Society, 31(4), 657–674. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017016680316

- Bruno, A. S., Greenan, N., & Tanguy, J. (2021). Does the gender mix influence collective bargaining on gender equality? Evidence from France. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 60(4), 479–520. https://doi.org/10.1111/irel.12290

- Bryson, A., & Forth, J. (2011). Work/life balance and trade unions. Evidence from the Workplace Employment Relations Survey 2011, Trades Union Congress, Congress House, London.

- Bryson, A., & Green, F. (2015). Unions and job quality. In A. Felstead, D. Gallie, & F. Green (Eds.), Unequal Britain At work. The evolution and distribution of job quality (pp. 130–146). Oxford University Press.

- Budd, J. W., & Mumford, K. (2004). Trade unions and family-friendly policies in Britain. Industrial and Labor Relations Review, 57(2), 204–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/001979390405700203

- Cao-Afspraken 2022. (2022). Ministerie van Sociale Zaken en Werkgelegenheid, Nederlands.

- Ceccon, D., & Medas, G. (2022). Codebook wageindicator collective agreements database – version 5.

- Chung, H. (2018). Dualization and the access to occupational family-friendly working-time arrangements across Europe. Social Policy and Administration, 52(2), 491–507. https://doi.org/10.1111/spol.12379

- Chung, H. (2019a). National-Level family policies and workers’ access to schedule control in a European comparative perspective: Crowding out or in, and for whom? Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 21(1), 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2017.1353745

- Chung, H. (2019b). Women’s work penalty’ in access to flexible working arrangements across Europe. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 25(1), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959680117752829

- Chung, H. (2022). The flexibility paradox: Why flexible working leads to (self-) exploitation. Bristol University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv2c3k1n8.9

- Chung, H., & Tijdens, K. (2013). Working time flexibility components and working time regimes in Europe: Using company-level data across 21 countries. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 24(7), 1418–1434. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2012.712544

- Chung, H., & van der Lippe, T. (2018). Flexible working, work–life balance, and gender equality: Introduction. Social Indicators Research, 151, 365–381. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-2025-x

- Cooper, R., & Baird, M. (2015). Bringing the ‘right to request’ flexible working arrangements to life: From policies to practices. Employee Relations, 37(5), 568–581. https://doi.org/10.1108/ER-07-2014-0085

- Crocker, J., & Clawson, D. (2012). Buying time: Gendered patterns in union contracts. Social Problems, 59(4), 459–480. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2012.59.4.459

- den Dulk, L. (2001). Work – family arrangements in organisations: A cross-national study in The Netherlands, Italy, the United Kingdom and Sweden. Rozenberg Publishers.

- den Dulk, L., & Groeneveld, S. (2013). Work-Life balance support in the public sector in Europe. Review of Public Personnel Administration, 33(4), 384–405. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734371X12449024

- den Dulk, L., Groeneveld, S., Ollier-Malaterre, A., & Valcour, M. (2013). National context in work-life research: A multi-level cross-national analysis of the adoption of workplace work-life arrangements in Europe. European Management Journal, 31(5), 478–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2013.04.010

- den Dulk, L., & Yerkes, M. (2020). Netherlands country note. In A. Koslowski, S. Blum, I. Dobrotić, G. Kaufman, & P. Moss (Eds.), International review of leave policies and research 2020 (pp. 422–434). http://www.leavenetwork.org/lp_and_r_reports/

- Dickens, L. (2000). Collective bargaining and the promotion of gender equality at work: Opportunities and challenges for trade unions. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 6(2), 193–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/102425890000600205

- ECTV. (2010). Encuesta de calidad de vida en el trabajo. Ministerio de Trabajo e Inmigración, Madrid.

- Estadísticas de Convenios Colectivos del Trabajo. (2023). Ministerio del Trabajo y Economía Social, España.

- EUROSTAT. (2018). Earnings and labour costs - annual data. Eurostat. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/product/page/EARN_SES18_04__custom_2938116

- Fleetwood, S. (2007). Why work-life balance now? The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 18(3), 387–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585190601167441

- Fuller, S., & Hirsh, C. E. (2019). “Family-Friendly” jobs and motherhood Pay penalties: The impact of flexible work arrangements across the educational spectrum. Work and Occupations 46(1), 3–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888418771116

- Gerstel, N., & Clawson, D. (2001). Unions’ responses to family concerns. Social Problems, 48(2), 277–297. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2001.48.2.277

- Gerstel, N., & Clawson, D. (2014). Class advantage and the gender divide: Flexibility on the job and at home. American Journal of Sociology, 120(2), 395–431. https://doi.org/10.1086/678270

- Glass, J. L., & Noonan, M. C. (2016). Telecommuting and earnings trajectories among American women and men 1989-2008. Social Forces, 95(1), 217–250. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sow034

- Gregory, A., & Milner, S. (2009a). Editorial: Work life balance: A matter of choice ? Gender, Work and Organization, 16(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2008.00429.x

- Gregory, A., & Milner, S. (2009b). Trade unions and work-life balance: Changing times in France and the UK? British Journal of Industrial Relations, 47(1), 122–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8543.2008.00710.x

- Grimshaw, D., Fagan, C., Hebson, G., & Tavora, I. (2017). Making work more equal: A New labour market segmentation approach. Manchester University Press. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2006.00754.x

- Haas, L., & Hwang, P. C. (2013). Trade union support for fathers’ use of work–family benefits: Lessons from Sweden. Community, Work & Family, 16(1), 46–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2012.724272

- Harbridge, R., & Thickett, G. (2003). Gender and enterprise bargaining in New Zealand: Revisiting the equity issue. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 28(1), 75–89.

- Heery, E. (2006). Equality bargaining: Where, who, why? Gender, Work and Organization, 13(6), 522–542. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2006.00321.x

- Hegewisch, A. (2009). Flexible working policies: A comparative review. Research Report #16. Manchester, UK: Equality and Human Rights Commission.

- Hijzen, A., Martins, P. S., & Parlevliet, J. (2019). Frontal assault versus incremental change: A comparison of collective bargaining in Portugal and The Netherlands. IZA Journal of Labor Policy, 9(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.2478/izajolp-2019-0008

- Hildebrandt, E. (2006). Balance between work and life - new corporate impositions through flexible working time or opportunity for time sovereignty? European Societies, 8(2), 251–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616690600645001

- Hogarth, T., Daniel, W. W., Dickerson, A. P., Campbell, D., Winterbotham, M., & Vivian, D. (2003). The Business Context to Long Hours Working. Sheffield: DTI. (Employment Relations Research Series No. 23). ISBN 0856053732 https://www.boe.es/eli/es/l/2021/07/09/10.

- ILO. (2019). Guide to developing balanced working time arrangements. Publications of the International Labour Office.

- Jansen, N. (2021). COLBAR-EUROPE Report 4: Collective bargainin in the Netherlands (pp. 1–34). COLBAR-EUROPE - WageIndicator Foundation and University of Amsterdam.

- Kassinis, G. I., & Stavrou, E. T. (2013). Non-standard work arrangements and national context. European Management Journal, 31(5), 464–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2013.04.005

- Kelly, E. L., & Kalev, A. (2006). Managing flexible work arrangements in US organizations: Formalized discretion or ‘a right to ask’. Socio-Economic Review, 4(3), 379–416. https://doi.org/10.1093/ser/mwl001

- Kim, J., Henly, J. R., Golden, L. M., & Lambert, S. J. (2019). Workplace flexibility and worker well-being by gender. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82 (3), 892–910. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12633

- Kirton, G. (2021). Union framing of gender equality and the elusive potential of equality bargaining in a difficult climate. Journal of Industrial Relations, 63(4), 591–613. https://doi.org/10.1177/00221856211003604

- Kirton, G., & Greene, A. (2006). The discourse of diversity in unionised contexts: Views from trade union equality officers. Personnel Review, 35(4), 431–448. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480610670599

- Korpi, W., Ferrarini, T., & Englund, S. (2013). Women’s opportunities under different family policy constellations: Gender, class, and inequality tradeoffs in western countries re-examined. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender, State & Society, 20(1), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxs028

- Kossek, E. E., & Lautsch, B. A. (2018). Work–life flexibility for whom? Occupational status and work–life inequality in upper, middle, and lower level jobs. Academy of Management Annals, 12(1), 5–36. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2016.0059

- Kurowska, A. (2018). Gendered effects of home-based work on parents’ capability to balance work with Non-work: Two countries with different models of division of labour compared. Social Indicators Research, 151, 405–425. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-2034-9

- Lambert, S. J., & Haley-Lock, A. (2004). The organizational stratification of opportunities for work-life balance: Addressing issues of equality and social justice in the workplace. Community, Work and Family, 7(2), 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/1366880042000245461

- MacGillvary, J., & Firestein, N. (2009). Family-Friendly workplaces: Do unions make a difference? Center for Labor Research and Education. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/50h115xq

- Magnusson, C. (2021). Flexible time–but is the time owned? Family friendly and family unfriendly work arrangements, occupational gender composition and wages: A test of the mother-friendly job hypothesis in Sweden. Community, Work and Family, 24(3), 291–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2019.1697644

- Medas, G., & Ceccon, D. (2021). COLBAR-EUROPE Report 6: Contents and characteristics of the Spanish collective bargaining agreements. COLBAR-EUROPE - WageIndicator Foundation and University of Amsterdam.

- Meil, G., Lapuerta, I., & Escobedo, A. (2020). Spain country note. International Review of Leave Policies and Research 2020, 537–554. http://www.leavenetwork.org/lp_and_r_reports/.

- Nicolaisen, H., Kavli, H. C., & Steen Jensen, R. (Eds.). (2019). Dualisation of part-time work. Policy Press. https://doi.org/10.47674/9781447364221

- OECD. (2019). Negotiating our way up. In negotiating our way up. https://doi.org/10.1787/1fd2da34-en

- OECD (2021). Methodological notes. In Understanding firm growth: Helping SMEs scale Up. OECD Publishing, 121–126. Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/b42bbdff-en

- Ollier-Malaterre, A. (2009). Organizational work–life initiatives: Context matters. Community, Work & Family, 12(2), 159–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668800902778942

- Ortega, J. (2009). Why do employers give discretion? Family versus performance concerns. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 48(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-232X.2008.00543.x

- Perry-Jenkins, M., & Gerstel, N. (2020). Work and family in the second decade of the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 420–453. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12636

- Ravenswood, K., & Markey, R. (2011). The role of unions in achieving a family-friendly workplace. Journal of Industrial Relations, 53(4), 486–503. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022185611409113

- Rigby, M., & O’Brien-Smith, F. (2010). Trade union interventions in work-life balance. Work, Employment and Society, 24(2), 203–220. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017010362145

- Sánchez-Mira, N., Olivares, R. S., & Oto, P. C. (2021). A matter of fragmentation? Challenges for collective bargaining and employment conditions in the Spanish long-term care sector. Transfer: European Review of Labour and Research, 27(3), 319–335. https://doi.org/10.1177/10242589211028098

- Seeleib-Kaiser, M., & Fleckenstein, T. (2009). The political economy of occupational family policies: Comparing workplaces in Britain and Germany. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 47(4), 741–764. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8543.2009.00741.x

- Skorge, Ø.S., & Rasmussen, M.B. (2021). Volte-Face on the welfare state: Social partners, knowledge economies, and the expansion of work-family policies. Politics and Society, 50(2), 222–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/00323292211014371

- Swanberg, J., Pitt-Catsouphes, M., & Drescher-Burke, K. (2005). A question of justice: Disparities in employees’ access to flexible schedule arrangements. Journal of Family Issues, 26(6), 866–895. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X05277554

- Ter Steege, D., Van Groenigen, E., Kuijpers, R., & Van Cruchten, J. (2012). Vakbeweging en organisatiegraad van werknemers. Sociaaleconomische Trends, 9–25.

- Tijdens, K., Besamusca, J., Ceccon, D., Cetrulo, A., Van Klaveren, M., Medas, G., & Szüdi, G. (2022). Comparing the content of collective agreements across the European Union: Is Europe-wide data collection feasible? E-Journal of International and Comparative Labour Studies, 11(2), 61–84.

- Trampusch, C. (2006). Industrial relations and welfare states: The different dynamics of retrenchment in Germany and The Netherlands. Journal of European Social Policy, 16(2), 121–133. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928706062502

- Van Winkle, Z. (2020). Family policies and family life course complexity across 20th-century Europe. Journal of European Social Policy, 30(3), 320–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928719880508

- WageIndicator Collective Bargaining Agreements Database. (2021, January). https://zenodo.org/records/4475583#.YflXburMK3A.

- Wet flexibel werken (2016). Ministerie van Sociale Zaken en Werkgelegenheid. http://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0018989/2016-01-01.

- Yerkes, M., & Tijdens, K. (2010). Social risk protection in collective agreements: Evidence from the Netherlands. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 16(4), 369–383. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959680110384608