Abstract

The present study considers whether parenthood has an impact on the worries that women and men have about climate change for the next generation and examines whether there are differences between the worries of mothers and fathers. The empirical material is based on a questionnaire-based survey that was administered in 2011 to a random selection of 3500 individuals in Sweden, with a response rate of 31%. The results indicate that parenthood, regardless of the parent’s gender, increases an individual’s worries about the impact of climate change on the next generation. Fathers are significantly more worried about climate change than men who are not parents; however, mothers do not worry significantly more than women who are not parents. In general, regardless of parenthood status, women worry about climate change more than men.

1. Introduction

Parents must consider many risks, and they face great uncertainty about countless subjects, from their young children’s diets and eating habits (Anving Citation2012; Löfmarck Citation2014) to their teenagers’ separation and transition to adult life (Anderegg Citation2003). Parenthood is therefore intimately associated with uncertainty about the future and with the fear that children will be exposed to injury or threat (Kelley, Hood, and Mayall Citation1998; Stjerna et al. Citation2014). According to Löfmarck (Citation2014), parenthood can also be associated with the risks that many individuals face at the fateful moment that they become parents. The present study assumes that the transition to parenthood is an overwhelming experience that affects an individual’s emotional responses to risks, which could influence parents’ worries about external risks such as climate change.

Parents face numerous worries about risks that are in many ways outside of their direct parental control, including children’s illnesses (Duran Citation2011; Stickler et al. Citation1991; Vandagriff et al. Citation1992), special needs (Caicedo Citation2014; Kotsopoulos and Matathia Citation1980), eating habits (Löfmarck Citation2014), and time spent at school (Barnett et al. Citation2010). These worries could also apply to climate change, which seems similarly uncontrollable and uncertain. Virtually no research has associated parenthood with worries about climate change. Although the relationship between parenthood and attitudes towards climate-related risks is a relevant topic, few quantitative studies have considered the issue (McCright and Dunlap Citation2013; Sundblad, Biel, and Gärling Citation2007; Whitmarsh Citation2011). However, in many parts of the world, climate change will primarily affect the next generations (see Ekholm and Olofsson 2017; Sundblad, Biel, and Gärling Citation2007).

Studies that examine questions similar to this issue include, for example, those that focus on the relationship between parenthood and willingness to pay as well as on parenthood and how one votes, both in relation to climate change (Dupont Citation2004; Milfont et al. Citation2012). However, these studies do not address issues of worry regarding the climate. The few surveys that have been conducted to investigate parental worries or scepticism about climate change reveal tendencies towards more climate worry and less climate scepticism among parents (McCright and Dunlap Citation2013; Sundblad, Biel, and Gärling Citation2007; Whitmarsh Citation2011). However, Ekholm and Olofsson’s (2017) study demonstrates that parents are significantly more worried about the consequences of climate change than non-parents, but that difference is not related to the parents’ risk perception of climate change.

Research on attitudes towards or worries about various environmental and climate-related risks finds that women are generally more worried about climate change than men, and they generally consider the associated risks to be greater than men do (Sundblad, Biel, and Gärling Citation2007). It would be interesting to examine if that gendered difference in degree of worry about climate change also prevails among parents. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to determine whether parenthood affects the degree to which men and women worry about climate change for the next generation, and specifically whether parenthood affects an individual’s emotional experience of a risk, such as climate change, and whether this experience differs between mothers and fathers.

2. Theory and previous research

Zinn (Citation2010) merged the biographical perspective and sociological risk research, maintaining that both fields stand to gain from exchanging approaches. The biographical perspective addresses biographical decisions, people’s ability to cope with earlier life experiences, and reflections on their own lives ‒ that is, identity-creating processes and changes. This merged perspective also combines discussions that encompass a more unified approach to handling risk and uncertainty in many types of situations and on different levels. Zinn (Citation2010) contends that ‘the biographical approach would allow reconstructing the complex links between individualised and socio-culturally as well as socio-structurally mediated experiences in everyday life’ (paragraph 18); the individual can integrate new experiences and expectations and change his or her worldview. Thus, the individual’s responses and attitudes to various risks and uncertainties are deeply rooted in both individual and institutional constructions of risk (Zinn Citation2010; Murgia Citation2012).

According to the biographical perspective, one aspect of risk is the biographical transitions that individually or collectively affect the course of an individual’s life (see Levy Citation1991). These transitions often constitute upheavals for the individual, or, as variously expressed in the literature, they are experienced as critical moments, turning points (see Holland and Thomson Citation2009), or fateful moments (Giddens Citation1991). When individuals undergo a life transition for the first time, they access a new social world, in terms of new roles and a new ‘sense of living’. In certain cases, this creates anxiety, if, for example, one is confronted with risks and an inability to predict what will happen (see Levy Citation1991). Parenthood is an example of such a transition to ‘a new world’, with changed roles and, in many people’s experiences, a new stance towards various risks. Parenthood is also strongly associated with worry, responsibility, and, for the rest of the person’s life, changing experiences according to the successive new stages of parenthood that can, in turn, give rise to new emotional experiences of risks. These changes that the individual undergoes are not only affected by his or her own biographical experiences, but they only occur when interacting with others (Murgia Citation2012; Zinn Citation2010), namely ‘different others’ (Douglas Citation1992; Lupton Citation2013), and they can lead to changed identity, self-image, and behaviours (Ezzy Citation1993; Fenwick, Holloway, and Alexander Citation2009; Murgia Citation2012). According to Knoester and Eggebeen (Citation2006), who studied men’s transition to parenthood, these changes can affect parents’ values, prioritisations, and emotional experiences (see also Daly, Ashbourne, and Brown Citation2013).

Additionally, Löfmarck (Citation2014) argues that parents have a special relationship to risk, which becomes particularly complicated if we also consider the gender aspect of parenthood and risk. Previous studies have demonstrated that mothers and fathers experience parenthood differently, regarding, for example, expectations, values, and emotional experiences (Daly, Ashbourne, and Brown Citation2013; Sheeran, Jones, and Rowe Citation2016); and the individual’s own expectations and those of society differ based on gender (Bailey Citation1999; Rehel, Citation2014). As a result, mothers and fathers possibly respond differently to risk discourses and have differing emotional experiences of various risks, such as the uncertain and hard-to-grasp risks of climate change. Rehel (Citation2014) stressed the significance of work and parental leave, contending that when the structure of fatherhood is similar to the typical structure of motherhood, opportunities will arise for fathers to develop a more active and responsible style of parenthood. According to Bailey (Citation1999), the dominant societal view of parenthood is that women have a primary responsibility to be mothers, and women are defined in relation to that role.

The transition to motherhood has been relatively well-researched, with studies finding that women experience the transition as overwhelming (Löfmarck Citation2014). With motherhood, they also experience improved self-image, growth of their own resources, and a greater sense of meaning in life (Sheeran, Jones, and Rowe Citation2016). The responsibility of being a good mother also involves self-reflection and the ability to cope with fears, demands, and commitments (Akerjordet and Severinsson Citation2010). In studies on the transition to fatherhood, men describe these experiences as something of a jolt ‒ a critical step in life (Palkovitz, Copes, and Woolfolk Citation2001) that is accompanied by a greater sense of responsibility (Rehel, Citation2014), as well as the emergence of changed attitudes, values, and priorities (Daly, Ashbourne, and Brown Citation2013; see also Knoester and Eggebeen Citation2006) regarding care and emotional experiences (Johansson Citation2011). This can be considered in relation to the major changes that have occurred in society, such as re-evaluated gender identities, family models, and intergenerational relations. Crespi and Ruspini (Citation2015) also highlight the two prominent yet contradictory societal discourses on fathers: the discourse claiming that the father’s role is to provide for the family, and the discourse advocating for involved and caring fathers. These discourses or expectations are manifested differently in different social contexts. For example, the distribution of parental leave or of care time between mothers and fathers differs by country.

Sweden is an interesting case for studying gender differences between parents, among other matters, because of the country’s gender-neutral parental leave insurance, whereby mothers and fathers are insured on equal terms for the opportunity to take paid parental leave. For the past few years, this insurance has been supplemented with an equality bonus for parent couples who share parental leave more equally, in addition to several ‘earmarked’ days that cannot be transferred to the other parent.

3. Materials, design, and method

The data used in this study are based on the 2011 survey, ‘Samhälle och Risk’ [Society and Risk], the questions of which were based on earlier studies and qualitative interviews (Öhman and Olofsson Citation2009). The survey, comprising 50 questions, was distributed by mail to 3500 people, who were randomly selected from individuals 16–75 years-old residing in Sweden. In addition, 1000 participants were randomly selected from three parishes1 to obtain a more representative selection of the Swedish population with respect to Swedes born in countries other than Sweden. The total number of participants in the study was 1078, thus yielding a response rate of 30.8%, of whom 45.8% were men and 54.2% women. Since the relatively high non-response rate constitutes a limitation of the results, a non-response analysis was carried out on a small group of individuals to determine how it may have affected the data. This was done by calling 110 randomly selected individuals among those who did not respond to the survey, asking them why they did not respond, along with a control question. Of the 110 individuals who could be reached, 20 (approximately 18%) elected to answer the control question. The non-response analysis did not find any notable difference between the non-response group and those who had responded to the survey.

The measures used for this study, namely, to evaluate the worries that mothers and fathers have about climate change for the next generation, are presented below. Additional variables are included to ensure that these other phenomena do not explain the connection between parenthood and climate worries. The survey measured parenthood with only two questions, one of which was selected here: Do you have children? This inclusive question has the advantage of not limiting parenthood to anything biological, instead including the possibility of everything from biological parents, adoptive parents and foster parents to other care providers in the children’s proximity.

Parents’ climate worries were investigated using the question: Are you worried that climate change will affect the next generation? The question has five reply options, ranging from ‘Not at all worried’ (1) to ‘Very worried’ (5). Earlier research demonstrates that perceptions of environmental and climate risks covary with a number of other variables. Apart from parenthood and gender, some of these variables are included in the regression analyses to control for their effects, including political ideology (measured on a ten-point scale ranging from right-wing, 1, to left-wing, 10), place of origin (specified as Sweden, the Nordic region, Europe/North America, and rest of the world), and highest completed level of education (specified as elementary school, high school, university or college, and other education, for which the comparison category is high school). Previous research shows a pattern, whereby individuals who are sceptical or who do not believe climate change is created by human activity are over-represented among white people, men, seniors, and people with politically conservative views, among several other variables (Leiserowitz Citation2005; McCright and Dunlap Citation2011; Whitmarsh Citation2011).

The source material in this study was processed using variance analysis (mean test) and ordinary least squares (OLS) multiple regression analysis.2 The regression analysis applies both to the overall differences in worries about climate change between parents and those who are not parents, regardless of gender, and also to the differences between women and men, using two separate models (split file) to study any differences between mothers’ and fathers’ climate worries and to control for the other selected variables, namely, education, political affiliation, and country of origin. The mean values are calculated to compare the worries that mothers and fathers, respectively men and women without children, have about the climate for the next generation.

4. Results

Initially, worries about the effects of climate change on the next generation are presented based on the groupings of parents versus non-parents (). Next, we consider the mean value () of climate worries for the next generation among mothers and fathers, as well as women and men who are not parents, making a comparison based on gender and in relation to parenthood. Finally, we present separate regression analyses of women’s and men’s climate worries (), presenting these two separate models to discern any significant differences in climate worries between mothers and fathers, as well as women and men who are not parents. Regression analyses also controlling for the remaining selected variables apart from parenthood, i.e. education, political views, and place of origin, are performed to ensure that these other phenomena cannot explain the climate worries of mothers and fathers.

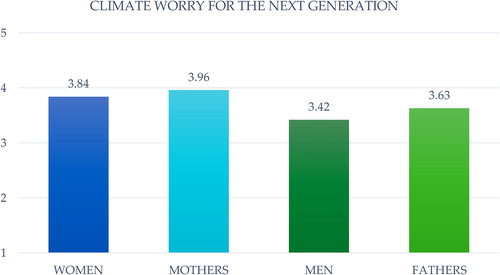

Figure 1. The mean values (scale 1–5) for mothers and fathers respectively women and men’s worries about climate change for the next generation. n = 1066.

Table 1. Multiple regression analysis (OLS) of parents’ worries about climate change for the next generation. A Beta value with an asterisk indicates that the difference is verifiably significant: * p < .05, ** p < .01.

Table 2. Multiple regression analysis (OLS) of women’s and men’s worries about climate change for the next generation. A Beta value with an asterisk indicate that the difference is verifiably significant: *p < .05, **p < .01.

The first analysis () presents parents’ worries about climate change for the next generation, controlling for the other selected variables, including gender, education, political ideology, and country of origin. There is a significant correlation between the individual’s parent or non-parent status and his or her response to the question, Are you worried that climate change will affect the next generation?, as well as gender and political views, but not education or place of origin (). This confirms that parents have more climate worries than those who are not parents, but generally, women are more worried than men, and those with more left-leaning political views are more worried about climate change than those with more right-leaning views. The model explains (adj R2) 5.7% of the variance in the dependent variable.

4.1. Mothers’ and fathers’ climate worries

In addition to demonstrating that parents have more climate worries than those who are not parents, the first model () also shows that women, regardless of parenthood status, generally worry about the effects of climate change for the next generation more than men. Hereafter, when studying women and men separately, the mean climate worry values () for mothers and fathers, and for women and men who are not parents, indicate that mothers (M = 3.96) worry more about climate than women (M = 3.84) who are not parents. This tells us that, regardless of parenthood, women’s worries about climate change are quite high, with an average of almost 4 out of 5. Among men, the same pattern prevails: fathers (M = 3.63) worry more about climate change than men (M = 3.42) who are not parents. However, men have a lower mean value than women, and furthermore, fathers worry less than women who are not mothers, despite the fact that parenthood increases the degree of worry about climate change for the next generation.

The mean values cannot discern any significant differences in climate worry. However, the two separate regression models, one for women (, model 1) and one for men (, model 2), controlling for the impact of other variables on women’s and men’s worries about climate change for the next generation, indicate whether parenthood has an effect on mothers’ and fathers’ climate worry. Regarding women’s climate worries, there is no significant association with parenthood. Mothers are not significantly more worried about the effects of climate change than women who are not parents. Rather, political views, university education, and Nordic origin are significant in this model. Women with a more left-leaning political ideology worry significantly more about climate change than those with more right-wing views, and women with a university education are more worried about climate change than those without such an education. Women from the other Nordic countries are less worried than women born in Sweden. However, the degree of explanation (adj R2) is very low at 2.4% (see , model 1).

Men’s level of worry about the effects of climate change on the next generation, however, is significantly associated with parenthood, implying that fathers worry significantly more about climate change than men who are not parents (, model 2). Apart from parenthood, it is only political views that are a significant factor among men: a more left-leaning ideology, as opposed to right-leaning, increases men’s climate worries. The degree of explanation (adj R2) for this model is 5.3%, which, though not particularly high, is not insignificant.

5. Analysis and discussion

Parenthood is strongly associated with worries and responsibility. A parent’s emotional ties to a child interact with the individual’s perception and understanding of various risks, such as climate change. Despite extensive research on parents’ worries about or assessment of various risks directly related to their children, such as diseases and their children’s school environment (e.g. Duran Citation2011; Kelley, Hood, and Mayall Citation1998), few studies examine parents’ worries about uncertain and abstract risks, such as climate change (Ekholm and Olofsson 2017), which, in many parts of the world, will primarily affect the next generations.

The purpose of this study was to examine whether, based on gender, parents worry differently about the effects of climate change on the next generation. The results demonstrate that fathers worry significantly more about climate change than do men who are not parents; however, these increased climate worries do not apply to women who are parents. Rather, regardless of parenthood status, women are generally more worried about climate change than men. However, parents generally worry significantly more about climate change than non-parents, which was also shown by Ekholm and Olofsson (2017).

The fact that men, in their transition to fatherhood, develop greater worries about an abstract risk such as climate change may be attributable to several factors, including the impact of external social expectations of fatherhood that fathers experience in relation to their social context (see Rehel, Citation2014; Murgia Citation2012). This may involve the two overarching discourses discussed by Crespi and Ruspini (Citation2015), namely, that of the father as provider and that of the father as involved caregiver, as well as the changed social expectation that fathers should be both simultaneously. Sweden’s gender-neutral national parental insurance, featuring a gender-equality bonus and a certain number of days that may not be transferred to the other parent, has affected parents in Sweden in terms of the distribution of parental leave between the sexes. This insurance points to the societal expectation that fathers should take a more active role, as measured by time spent with their children. Therefore, in Sweden, many fathers on parental leave have stayed at home and taken most of the responsibility for their children, while the mothers have worked for a significant length of time. Rehel (Citation2014) contends that the distribution of time spent at home with children versus at work greatly affects the individual’s experience of parenthood. Fathers on parental leave participate in their children’s daily activities and the ‘daily realities of responsibility’ that accompany child care on the same terms as mothers on parental leave (Rehel Citation2014). Johansson’s (Citation2011) case study of fathers in Sweden strengthens this conception of fathers who prioritise caring and emotional experiences. Daly, Ashbourne, and Brown (Citation2013) elaborate on this concept by describing fathers’ changed experience as an attitude shift in the form of increased care for their children (see also Knoester and Eggebeen Citation2006).

When Swedish fathers have more extensive parental responsibility and spend more time caring for their children, their emotional experiences could be affected, resulting in increased worries about their children’s future and, in this case, worries that their children may suffer the consequences of climate change. That mothers do not have significantly different worries about climate change from women who are not parents may be due to their already high level of climate change worry before becoming parents, among other factors. Generally, from their earliest years, women are expected to take responsibility for those close to them, particularly children; indeed, women are defined by this role (see Bailey Citation1999). This socialisation process may affect women’s worries about various risks, such as climate change, through a caring practice that does not seem equally accessible to men before they become parents.

One possible objection to the conclusions of this study could be the low degree of explanation of the analyses. However, the primary focus of this study is to determine whether parenthood in a Swedish context has any impact on the worry men and women have about the effects of climate change on the next generation, which, in an earlier study, was demonstrated to be the case within a different survey sample from a smaller region of Sweden (Ekholm and Olofsson 2017). We might not expect parenthood per se to have a high degree of explanatory power with respect to climate worries, as there should be a number of other explanations. The purpose of this study was not to explain climate worries in such terms. Rather, it was to reveal any differences between the climate worries of mothers and fathers. In this study, I therefore analysed whether the same pattern noted in earlier studies regarding sex differences in climate attitudes (see, e.g. Sundblad, Biel, and Gärling Citation2007) is also influenced by parenthood and found that this was the case.

There are multiple differences between countries, including family structures, discourses about the father’s role in the family, and societal values and expectations regarding parental care. Therefore, to determine whether it is the Swedish context that creates this pattern of differences in climate worries between mothers and fathers, further research should be undertaken in other social contexts, examining, for example, the policy on the distribution of parental leave between the sexes and the prevailing discourse in Sweden regarding men’s care practice.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 Namely, Västra Skrävlinge, Spånga, and Bergsjön.

2 As the dependent variable, climate worry, is measured using an ordinal scale, the analysis was repeated using a logistic regression. The result was the same in the two different types of regression, but a minor deviation applies to the significance of fathers in the logistic regression that was below 1.0 (p = .067) but significant in the OLS regression (, model 2).

References

- Akerjordet, K., and E. Severinsson. 2010. “Being in Charge - New Mothers' Perceptions of Reflective Leadership and Motherhood.” Journal of Nursing Management 18 (4):409–417. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01108.x.

- Anderegg, D. 2003. Worried All the Time: Overparenting in an Age of Anxiety and How to Stop It. New York, NY: Free Press.

- Anving, T. 2012. “Måltidens Paradoxer. Om Klass Och Kön I Vardagens Familjepraktiker. Lund Dissertations in Sociology.” Doctoral diss., Lunds Universitet.

- Bailey, L. 1999. “Refracted Selves? A Study of Changes in Self-Identity in the Transition to Motherhood.” Sociology 33 (2):335–352. doi:10.1177/S0038038599000206.

- Barnett, R., K. Gareis, L. Sabattini, and N. Carter. 2010. “Parental Concerns about after-School Time: Antecedents and Correlates among Dual-Earner Parents.” Journal of Family Issues 31 (5):606–625. doi:10.1177/0192513X09353019.

- Caicedo, C. 2014. “Families with Special Needs Children: Family Health, Functioning, and Care Burden.” Journal of the American Psychiatric Nurses Association 20 (6):1–10. doi:10.1177/1078390314561326.

- Crespi, I., and E. Ruspini. 2015. “Transition to Fatherhood: New Perspectives in the Global Context of Changing Men's Identities.” International Review of Sociology 25 (3):353–358. doi:10.1080/03906701.2015.1078529.

- Daly, K. J., L. Ashbourne, and J. L. Brown. 2013. “A Reorientation of Worldview: Children’s Influence on Fathers.” Journal of Family Issues 34 (10):1401–24. doi:10.1177/0192513X12459016.

- Douglas, M. 1992. Risk and Blame: Essays in Cultural Theory. London: Routledge.

- Dupont, D. P. 2004. “Do Children Matter? An Examination of Gender Differences in Environmental Valuation.” Ecological Economics 49 (3):273–86. doi:10.1016/j.ecolecon.2004.01.013.

- Duran, B. 2011. “Developing a Scale to Measure Parental Worry and Their Attitudes toward Childhood Cancer after Successful Completion of Treatment: A Pilot Study.” Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing 28 (3):154–168. doi:10.1177/1043454210397755.

- Ekholm, S., and A. Olofsson. 2017. “Parenthood and Worrying about Climate Change: The Limitations of Previous Approaches.” Risk Analysis 37 (2):305–314. doi:10.1111/risa.12626.

- Ezzy, D. 1993. “Unemployment and Mental Health: A Critical Review.” Social Science Medicine 37 (1):41–52. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(93)90316-V.

- Fenwick, S., I. Holloway, and J. Alexander. 2009. “Achieving Normality: The Key to Status Passage to Motherhood after a Caesarean Section.” Midwifery 25 (5):554–563. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2007.10.002.

- Giddens, A. 1991. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Holland, J., and R. Thomson. 2009. “Gaining Perspective on Choice and Fate: Revisiting Critical Moments.” European Societies 11 (3):451–469. doi:10.1080/14616690902764799.

- Johansson, T. 2011. “Fatherhood in Transition: Paternity Leave and Changing Masculinities.” Journal of Family Communication 11 (3):165–180. doi:10.1080/15267431.2011.561137.

- Kelley, P., S. Hood, and B. Mayall. 1998. “Children, Parents and Risk.” Health and Social Care in the Community 6 (1):16–24. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2524.1998.00094.x.

- Knoester, C., and D. J. Eggebeen. 2006. “The Effects of the Transition to Parenthood and Subsequent Children on Men’s Well-Being and Social Participation.” Journal of Family Issues 27 (11):1532–1560. doi:10.1177/0192513X06290802.

- Kotsopoulos, S., and P. Matathia. 1980. “Worries of Parents regarding the Future of Their Mentally Retarded Adolescent Children.” International Journal of Social Psychiatry 26 (1):53–57. doi:10.1177/002076408002600107.

- Leiserowitz, A. A. 2005. “American Risk Perceptions: Is Climate Change Dangerous?” Risk Analysis 25 (6):1433–1442. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.2005.00690.x.

- Levy, R. 1991. “Status Passages as Critical Life Course Transitions. A Theoretical Sketch.” In Theoretical Advances in Life Course Research, 87–114.

- Löfmarck, E. 2014. "Den Hand Som Föder Dig, En Studie Av Risk, Mat Och Moderskap I Sverige Och Polen. [The Hand that Feeds You: A Study on Risk, Food and Motherhood, in Sweden and Poland.]." Doctoral diss., Uppsala University.

- Lupton, D. 2013. “Risk and Emotion: Towards an Alternative Theoretical Perspective.” Health, Risk and Society 15 (8):634–647. doi:10.1080/13698575.2013.848847.

- McCright, A. M., and R. E. Dunlap. 2011. “Cool Dudes: The Denial of Climate Change among Conservative White Males in the United States.” Global Environmental Change 21 (4):1163–1172. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.06.003.

- McCright, A., and R. Dunlap. 2013. “Bringing Ideology in: The Conservative White Male Effect on Worry about Environmental Problems in the USA.” Journal of Risk Research 16 (2):211–226. doi:10.1080/13669877.2012.726242.

- Milfont, T. L., N. Harré, C. G. Sibley, and J. Duckitt. 2012. “The Climate-Change Dilemma: Examining the Association between Parental Status and Political Party Support.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 42 (10):2386–2410. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2012.00946.x.

- Murgia, A. 2012. “Between Work and Nonwork: Precarious Transitions through Life Stories and Everyday Life.” Narrative Works 2 (2):41–61.

- Öhman, S., and A. Olofsson. 2009. Kris Och Risk I Det Heterogena Samhället. Sweden: Mid Sweden University.

- Palkovitz, R., M. A. Copes, T. N. Woolfolk. 2001. “It's like… You Discover a New Sense of Being” Involved Fathering.” As an Evoker of Adult Development.” Men and Masculinities 4 (1):49–69. doi:10.1177/1097184X01004001003.

- Rehel, E. M. 2014. “When Dad Stays Home Too: Paternity Leave, Gender and Parenting.” Women’s Studies 28 (1):110–132. doi:10.1177/0891243213503900.

- Sheeran, N., L. Jones, and J. Rowe. 2016. “Motherhood as the Vehicle for Change in Australian Adolescent Women of Preterm and Full-Term Infants.” Journal of Adolescent Research 31 (6):700–724. doi:10.1177/0743558415615942.

- Stickler, G. B., M. Salter, D. D. Broughton, and A. Alario. 1991. “Parents' Worries about Children Compared to Actual Risks.” Clinical Pediatrics 30 (9):522–528. doi:10.1177/000992289103000901.

- Stjerna, M. L., M. Vetander, M. Wickman, and S. O. Lauritzen. 2014. “The Management of Situated Risk: A Parental Perspective on Child Food Allergy.” Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine 18 (2):130–145. doi:10.1177/1363459313481234.

- Sundblad, E.-L., A. Biel, and T. Gärling. 2007. “Cognitive and Affective Risk Judgements Related to Climate Change.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 27 (2):97–106. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2007.01.003.

- Vandagriff, J. L., D. G. Marrero, G. M. Ingersoll, and N. S. Fineberg. 1992. “Parents of Children with Diabetes: What Are They Worried about?” The Diabetes Educator 18 (4):299–302. doi:10.1177/014572179201800407.

- Whitmarsh, L. 2011. “Scepticism and Uncertainty about Climate Change: Dimensions, Determinants and Change over Time.” Global Environmental Change 21 (2):690–700. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2011.01.016.

- Zinn, J. 2010. “Biography, Risk and Uncertainty-Is There Common Ground for Biographical Research and Risk Research?” Forum: Qualitative Social Research 11 (1):Art. 15.