Abstract

Social science risk studies often begin with one of two starting points: a particular risk, such as that of natural or technical disasters, or, alternately, with the individual experiencing risk. But risk may not be the guiding concept for how people act in the social world. This article explores how social practice theory broadens the possible starting points for social science risk research and in turn improve our understanding of risk. It does so by drawing on existing empirical studies within risk research that make use of practice-oriented theories and outline three essential arguments for practice-based risk research. First, that risk is understood as embedded in socially shared practices, second, that risk is routinised, and third, that risk is present in both social and material relations. Together, these arguments make out an analytical starting point of ‘practices of interest and intersecting practices’, representing a methodological situationalism, where actions rather than actors are at the core of research. In conclusion, a sensibility for practice in risk research is suggested.

Introduction

Social science risk research explores our understandings of risk in the social world. Four main trajectories have produced a variety of definitions, theorisations, and analyses of risk; risk perception (Slovic Citation1987), the risk society thesis and reflexive modernisation (Beck Citation1992; Beck, Giddens, and Lash Citation1994; Giddens Citation1991), risk and governmentality (O'Malley Citation2009, Citation2013), and a socio-cultural risk perspective (Douglas and Wildavsky Citation1982; Tulloch and Lupton Citation2003). Empirical risk studies tend to position themselves within one (or more) of these trajectories, taking their starting point in risk (Reith Citation2004). This is no surprise, but it might be beneficial for empirical risk research to engage more with other social theories as well. In this article, I explore how ‘social practice theory’ (Schatzki Citation1996) can be utilized in a risk research context.

There has been some engagement with practice-oriented theories in risk research to date, across a variety of topics. Hennell (Citation2017) and Bengtsson and Ravn (Citation2018) use practice theory to understand risks related to alcohol consumption and partying among youth, Zinn (Citation2015, Citation2019) and Bunn (Citation2017) explores risk-taking and routines; Jacobsen (Citation2013), Blue et al. (Citation2016) and Wills et al. (Citation2015) engage with practice theory and food-related risks, and Corvellec (Citation2009), Boholm, Corvellec, and Karlsson (Citation2012) and Nicolini (Citation2012) use practice theory to study organisational risk management. Studies also engage with the predecessors of the type of practice theory presented here, including Bourdieu’s (Citation2013 [1984]) concept of ‘habitus’ that Crawshaw and Bunton (Citation2009) use to understand the disposition of young men to engage (or not) in risk-taking activities. Similarly, Nygren, Öhman, and Olofsson (Citation2015) use Butler’s (Citation1990) ‘doing gender’ concept to explore how LGBT people embody and perform risk in everyday life.

The field still lacks theoretical and conceptual discussions of what focusing on practice means to risk research, and how practice theory can be a useful toolbox in empirical studies. This article addresses this gap by discussing how practice theory can strengthen our knowledge about particular risk understandings as the outcome of the routinised performance of everyday life. How we deal with the uncertainty in everyday events like crossing the road, drinking alcohol, cutting a raw chicken, driving a car, or buying an apartment.

The article first outlines the basic principles of practice-oriented theories. I concentrate on what is now commonly referred to as ‘social practice theory’ or just ‘practice theory’, which is a synthesis of three phases of practice-oriented theories. In this form, practice theory represents a structured approach for empirical studies of everyday life. With this concept of practice in mind, I outline its benefits for risk research in three ways. First, by looking at the differences between studying individual risk behaviours and risk as embedded in social practices, second by emphasising routine performances, and third by incorporating materials in studies of risk. Insights from that exercise underpin the article’s conclusion that ‘practices of interest’ is a fruitful analytical starting point for social science studies of risk. A ‘sensibility for practice’ in risk research is recommended.

Social practice theory

Practice is a term used in a range of disciplines including philosophy, history, social and cultural anthropology, and sociology, to understand human activity in the social world. Practice encompasses issues such as ‘the nature of subjectivity, embodiment, rationality, meaning and normativity; the character of language, science and power; and the organisation, reproduction, and transformation of social life’ (Schatzki Citation2001, p. 1). The huge diversity of applications means that there is no such thing as one unified practice theory, but lines of thought that follow the same ontological basis: the fundamental unit of analysis for most practice theorists is the practice itself, and the social world is seen as composed of practices (Schatzki Citation1996).

At a general level, a practice can be defined as ‘arrays of human activity’ and what connects these activities (Schatzki Citation2001, p. 2). The analysis of practices must be concerned with practical activity as well as the representations of such activities (Warde Citation2016a, p. 82). Accordingly, practice theories question pure individualist explanations such as rational decision-making or individual motivations and behaviours. Instead it offers a processual ontology where the social world is constantly evolving through processes of activities and their representations (Warde Citation2016a). The social world is analysed through the interconnectedness of practices, and social constructions such as language, institutions, actions, roles, norms, emotions and so on are therefore always understood as part of practices that are performed by individuals. Everyday life is seen as made up of routinised performances of socially and culturally shared practices (Shove, Pantzar, and Watson Citation2012).

The individualism of proponent psychological and economic theories have increasingly come to dominate interpretations of human activity, most clearly demonstrated by the revival of ‘behaviourism’ (Warde Citation2016a). Behaviourism was largely discredited in the 1960s and 70 s, in an era where the social sciences had a strong focus on norms and values, then regained prominence in the 1990s, partly due to the processes and changes captured by theories of late modernity and reflexive modernisation, in which the reflexive individual takes centre stage (Beck, Giddens, and Lash Citation1994). A renewed interest in practice can be understood as a response to the revival of behaviourism. For Reckwitz (Citation2002b), the appeal of practice theories is the rejection of both ‘homo economicus’, where human action is explained as individual intentions and ‘homo sociologicus’, where human action is seen as a result of social norms and values (p. 245). Reckwitz places practice theories in the field of cultural theory, seeing action as the performance of symbolic structures of knowledge.

The long history of practice-based theories can be followed through three main phases (Lizardo Citation2009; Nicolini Citation2012; Postill Citation2010; Warde Citation2014). Finding a way to avoid methodological individualism (the social world consists of individual actions) and methodological holism (the social world consists of structures that produce actions) was the main concern in the first phase. Prominent social theories in this phase include Giddens’ (Citation1984) structuration theory and Bourdieu’s (Citation2013 [1984]) concept of habitus, used to explain how actions are produced by social structures and changed by individuals.

In the second phase, scholars were concerned with theorising performance. Here, we find important contributions from Butler (Citation1990), Ortner (Citation1984), and perhaps most dominating, Schatzki (Citation1996, Citation1997, Citation2002) and Cetina, Schatzki, and Von Savigny (Citation2001). They suggest that in the flow of activities we carry out in our everyday lives, we can identify sets of repertoires that are performed together as a coordinated entity, recognisable across time and space (Røpke Citation2009). Schatzki (Citation1996) defines this entity, a practice, as ‘a temporally unfolding and spatially dispersed nexus of doings and sayings’ (p. 89). Individuals are ‘carriers’ of these practices and also the performers of them. Individuals can adapt and change the practices they perform. They stop performing some and start performing others, and they have individual reasons for participating in certain practices (Warde Citation2016a). For practices to exist, they must be performed over and over again, and changes in performances change practices (Shove, Pantzar, and Watson Citation2012; Warde Citation2005).

In the third phase, efforts have been made to bring together insights from the first two phases and construct a set of concepts to be used in empirical studies, presented in more detail below.

Practice as an entity and practice as performance

Empirical studies look at practices in two main ways; (i) what constitutes a coordinated entity, and (ii) how it is performed. The widely used definition by Reckwitz (Citation2002b, p. 249) captures both of these aspects:

A ‘practice’ (Praktik) is a routinized type of behaviour which consists of several elements, interconnected to one other: forms of bodily activities, forms of mental activities, ‘things’ and their use, a background knowledge in the form of understanding, know-how, states of emotion and motivational knowledge.

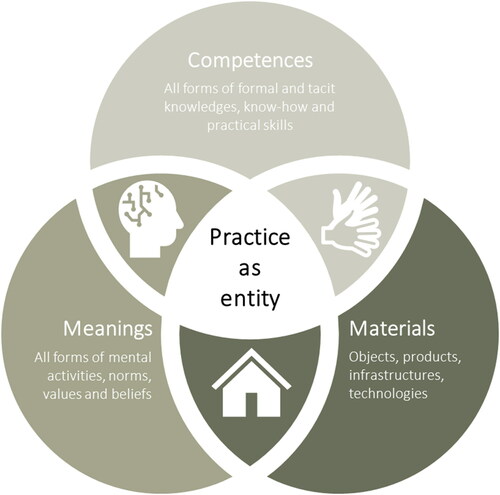

Using Reckwitz’s contribution, the elements of a practice as an entity are defined as:

Forms of bodily activities: the way the body learns and performs a practice, how it handles objects, as well as talks and moves.

Forms of mental activities: the social and symbolic significance of participating in a practice such as motivations to participate, beliefs, norms, engagements, and emotions.

Things and their use: all materials that are used to perform a practice such as objects, technologies and infrastructures, tools, products, and the body.

A background knowledge: socially and culturally shared understandings and skills that are needed to perform a practice appropriately, and practical understandings to perform a practice competently.

When we study practices as entities, we study the elements of a certain routinised behaviour (e.g. cooking), what elements it includes (e.g. a kitchen, food items, utensils, understandings of kitchen hygiene, and practical cooking skills), how the elements are interconnected (e.g. how our kitchen infrastructure affects the way we prepare a chicken) and how these connections are reproduced or changed (e.g. how everyday meal preparation is affected by knowledge about food risks and hygiene). Also, a practice is always connected to other (elements of) practices forming bundles and to the rhythm of everyday life (Shove Citation2009; Southerton Citation2013; Walker Citation2014). depicts the simplest version of a practice and its elements, developed by Shove, Pantzar, and Watson (Citation2012) and used extensively in empirical studies across research fields.

Figure 1. The elements of a practice. Based on Shove, Pantzar, and Watson (Citation2012).

Practices as entities cannot exist without being performed. Schatzki (Citation1996, p. 90) writes that a performance ‘actualizes and sustains practices in the sense of nexuses’. When we study performance, we study the understandings and meanings of practices that are unfolded by the individual carriers performing them. When individuals are recruited to a practice, they are enrolled in the socially shared way of understanding and carrying out that activity, including the emotions or desires that come with it.

Performance is not only about reproduction. Warde (Citation2005, p. 141) explains that practices ‘contain the seeds of constant change.. as people in myriad situations adapt, improvise and experiment’. Importantly, social practices do not represent patterns of actions that are simply adopted by the individual. Practitioners draw on their previous experiences, their learned knowledge and skills, and their available social, cultural, and economic resources when they perform practices, as well as considering how the practice is interlinked with other practices (Heidenstrøm and Rhiger Hansen Citation2020). Some people adopt certain practices and not others, and some are skilled while others are amateurs. We can follow practices over time through performance to identify their ‘careers’, as well as their disappearance.

Practices themselves can be the object of study as well as used as a lens to understand a specific issue. Schatzki (Citation1996) suggests differing between ‘integrative’ and ‘dispersed’ practices. Integrative practices are complex bundles of elements that together make up a practice to be performed by practitioners. Warde (Citation2016b, pp. 41–42) summarises the common criteria of integrative practices in the following way: (i) the entity is recognisable and makes sense to talk about; (ii) people perform the practice in more or less the same way within a social and cultural context, and correct performance can be identified; and (iii) the practice is something beyond the individual’s mind and goes beyond the sum of their doings and sayings.

Dispersed practices appear within many practices rather than as one integrative unit of elements. They are woven into other practices and nexuses of practices and follow the mental activities or meanings of the practices they are a part of. Schatzki uses questioning, ordering, greeting, and describing as examples of dispersed practices. They are dispersed because they only exist within other practices, and people are usually engaged in an integrative practice when they carry out a dispersed practice (Schatzki Citation1996, p. 99).

Individual and social explanatory frameworks

Practice theory proposes a shift away from an explanatory framework where individuals are the primary analytical unit for social analyses (methodological individualism) and toward that of the practice being the smallest analytical unit from which we can understand the social world (defined by Sedlačko (Citation2017) as methodological situationalism, or a processual understanding).

At its most instrumental individual explanatory frameworks are modelled after a positivist view of science, using cause and effect models to predict and explain human behaviours as reactions to a specific situation. The portfolio model can be used as a starting point for explaining the fundamental claims of behaviour-oriented understandings. A portfolio is a relatively stable set of individual beliefs that do not change between contexts (Markowitz Citation1952; Whitford Citation2002). The individual uses the portfolio in any given situation to determine how to act and acts upon the desire to support their pre-existing beliefs. According to this model, all actions have a purpose and are thus rational. To be rational entails having a knowledge base from which to choose alternatives, including knowledge about the consequences of each alternative.

Bounded rationality is introduced to move beyond the idea that behaviours are solely motivated by rational decision-making, to explain why people do not always act according to what experts define as the optimal decision (Jones Citation1999). When people deviate from their goal, they do so because systematic cognitive biases hinder them from acquiring the correct knowledge to make the right decision (Southerton Citation2013). Economic and psychological risk research, including psychometric analyses (Slovic Citation1987) and drawing from the cognitive modelling of Kahneman (Citation2011), behavioural economics – perhaps most known for the concept of ‘nudge’ –, has become central individually oriented explanatory models in risk research.

Anthropological or cultural risk researchers have been critical of these (bounded) rationality-approaches (Douglas Citation2002; Douglas and Wildavsky Citation1982; Tulloch and Lupton Citation2003). Tulloch and Lupton (Citation2003) contend that bounded rationality would imply that there exists a rational way of responding to a definable risk out there, and that risk experts can define this rational way. It forms a hierarchical relationship between expert and lay knowledge and reduces all actors to rational individuals with the intention of avoiding risk. Tulloch and Lupton (Citation2003, p. 8) claim that:

Sociocultural meanings tend to be reduced to ‘bias’, contrasted with the supposedly ‘neutral’ stance taken by experts in the field of risk assessment, against whose judgements lay opinions are compared and found wanting. Risk avoidance in this literature is typically portrayed as rational behaviour, while risk-taking is represented as irrational or stemming from lack of knowledge or faulty perception.

There are two core points to be followed in their critique. Firstly, Tulloch and Lupton claim that risk perception research unknowingly reproduces a realist perspective on risk where expert knowledge surpasses lay knowledge. This also affects the types of risks that are studied, as well as which individuals are seen to act on a particular risk. There is thus a need to be much more aware of what a study defines as a risk to avoid reproducing a particular rationality a priori (Henwood et al. Citation2008; Jasanoff Citation1998; Lupton Citation2013). I return to the forms of knowledge below.

Secondly, rationality-based risk research takes its starting point in the individual, who is seen to behave in a certain way to manage a predefined risk. A first major problem with this view is that it does not acknowledge that behaviours are bound up within social and material structures and that individuals are positioned in a social world where sociodemographic factors such as class, ethnicity, gender, age, occupation, geographic location, or intersectional factors produce inequalities and significantly affect how people act when facing the same situation (Nygren, Öhman, and Olofsson Citation2015; Olofsson et al. Citation2014). A second problem is that people do not deal with one risk at a time. This is particularly important to acknowledge in studies based on experiments, where people are removed from the complexities of their social lives and placed in unrealistically simple settings. A third problem is that many studies presuppose that people make some sort of choice about risk and that their goal is to minimise the risks that researchers have defined as being important to minimise.

Individually oriented understandings and particularly behaviouristic models have had an enormous influence on risk research in the social sciences, as well as in policymaking (Jasanoff Citation1998, Citation1999). One possible reason for this might be that they offer causal or correlative models based on mechanisms for human action that can be applied to almost any situation (e.g. attitude-behaviour models (Ajzen and Fishbein Citation1977)). Their results can easily be translated to concrete policy measures such as to provide people with more information encouraging them to reduce high-risk behaviours (Shove Citation2010). Information and awareness campaigns are easy to design and implement, visual and tangible, however, proven to have little effect, particularly over time (Hargreaves Citation2011; Strengers and Maller Citation2014).

Whereas behaviour-oriented studies are most pronounced in economy and social psychology, sociological studies of risk orient their analyses much more towards the social and cultural processes in which risks are interpreted, such as those going on in everyday life. However, Olofsson and Zinn (Citation2018, p. 11) write that ‘sociological approaches themselves have struggled to do justice over the multi-layered social reality through which risk and uncertainty are experienced, produced, and managed’. Methodological orientations towards meaning-making, sense-making, narratives, biographies, experiences and so on in risk research (discussed extensively in Olofsson and Zinn Citation2018), tend to follow methodological individualism in the sense that the social is understood through the individual, such as through different subjectivities (Brown Citation2016, p. 338). These studies give important insights into the micro-level processes of everyday experiences, reasonings, choices, emotions, values and how they develop over time over between situations. However, there is still a lack of connecting these individual experiences to larger and organised constellations of everyday activities that are performed in more or less the same way by multiple people, and that consist of artefacts and the embodied as well as what can be expressed through language.

Practice theory has the analytical capacity – in decentring the individual and centring the practice – to avoid individualising social processes. Centring practices means that behaviours are understood not as the expression of individuals’ values, meanings, or attitudes, rather, behaviours are expressions of social and cultural conventions, shared ways of acting in each situation, and socially learned competences to act in a certain way. The way we act is also based on a social history that involves much larger systems and representations (Spurling et al. Citation2013). It is therefore essential to practice theory that the social world is routinely produced, reproduced, and changed through practices and not through individuals (Nicolini Citation2017).

Hennell (Citation2017) captures the difference between individual and social explanatory frameworks in a study of young people’s alcohol consumption in the UK. The current national risk management policy understands youth drinking culture as irresponsible individuals that drink excessively and that need more information about safe alcohol consumption. This understanding has resulted in information campaigns like ‘Know your limits’, from the UK National Health Service. The problem with such campaigns is that they direct attention towards the individual that behaves, makes choices, and are responsible or at risk. To break through this one-sided focus on the individual, Hennell argues that we must make explicit the complexities of everyday life, its texture of heterogeneous sets of actions that are framed within a larger social context. Drinking practices are constituted as part of young people’s wider social life and the implications of alcohol consumption are situated within the social, temporal, economic and cultural organisation of young people's everyday life.

Hennell finds that young people do not narrate their drinking practices in terms of risk, as the information campaign had (implicitly) assumed. Hazards, vulnerabilities, and threats were accepted as ever-present and routinised part of their drinking practices. The risk of intoxication, for example, was managed through adaptations made to the performance of the drinking practice, such as having a ‘cut off point’ where they would stop drinking. However, this management strategy was not necessarily done just to reduce primary health risks such as harming one's body by drinking too much alcohol. Secondary risks, which are the issues that might affect completely different practices outside the context of drinking, such as friendship relations and other social activities, played a significant part in their risk management. Consequently, risk management at a party cannot be seen detached from the other practices of youth everyday life. It is coordinated with school and family life in the sense that extensive partying could harm school efforts and family relations, yet no partying at all could similarly harm friend relations, hinder social inclusion and cause a lack of belonging. Young people also had a shared understanding of what an acceptable performance of a drinking practice meant, as well as the place it holds in youth culture. The adaptations they did were variations of this drinking practice. Simply asking the youth to stop drinking would have undesired effects for many interlinked practices.

A practice-based social explanatory framework implies that the actions of social groups are shaped by wider cultural and social structures that determine actions in implicit and inconspicuous ways, normalising certain responses to situations and events, emphasising some and ignoring others (Meier, Warde, and Holmes Citation2018). Practice theory shift analyses away from the individual level and on to the practice as consisting of interconnected elements and routinized performances, and does so without relating them to the individual again by studying individual experiences.

Reflexivity and forms of knowledge

So far, I have positioned practice theory within a social explanatory framework oriented towards methodological situationalism and social processes. In the following, I position practice theory as focussing on routine performances and embodied knowledge rather than reflexive actions and instrumental or expert knowledge. The practice-oriented understanding of risk thus stands in sharp contrast to theorisations of risk in late modernity, such as those proposed by Beck (Citation1992) and Giddens (Citation1991). Everyday life is, as Beck and Giddens understand it, dominated by reflexive concerns about risk in late-modern societies. The individual has been released from the strict class norms of the industrial society and into a world of continuous choice and reflexivity, also about risk – a state of ontological insecurity. As a result, individuals must deal with risks themselves in their everyday lives by continuously evaluating the validity of expert knowledge (Beck, Giddens, and Lash Citation1994).

Interestingly, Giddens’ writings on reflexivity in the 1990s contradicts his earlier theorising on the duality of agency and structure, a predecessor of practice theory. Whilst structuration entails an agent acting according to routine and rules, reflexive modernisation implies constant non-routine, reflexive monitoring of action (Bagguley Citation2003). Although it is beyond the scope of this article to discuss internal contradictions in Giddens’ social theory, it is important to note this shift and that practice theory positions itself with that of socially shared and routinised action (Schatzki Citation1997 details how current theorisations of practice, based on Wittgenstein, deviate from Giddens' account of structures).

Reflexive modernisation has been widely criticised for overemphasising expert knowledge and rational choice, as well as using anecdotal empirical evidence for how people live their everyday lives (see Dawson Citation2012 for an extensive review). In risk research, these criticisms have laid grounds for problematising the relationship between instrumental rationality underpinned by expert knowledge and irrationality underpinned by subjective and practical knowledge (Horlick-Jones Citation2005; Horlick-Jones and Prades Citation2009; Horlick‐Jones Citation2005; Welsh and Wynne Citation2013; Wynne Citation1996), and between rationality and intuition and emotion (Zinn Citation2008, Citation2016). It has also resulted in comprehensive empirical studies and discussions of risk and everyday life (such as Alaszewski and Coxon Citation2008; Henwood et al. Citation2008; Parkhill et al. Citation2010; Tulloch and Lupton Citation2003).

Wynne (Citation1996) points to Beck and Giddens’ overly focus on the role of institutions and expert knowledge, neglecting the many social and cultural interactions of everyday life. He demonstrates how risk analyses tend to treat expert knowledge as natural and objective, giving it legitimacy and primacy in science and policy (Benadusi Citation2014). From the position of Science and Technology Studies (STS), Wynne traces the roots of expert knowledge, demonstrating under which social conditions it is produced and thus its subjectivity. In line with how practice theory understands the element of ‘competences’ presented above, the lay knowledge of the Cumbrian sheep farmers is likewise subjective, however, it is different in that it is experiential, not formalised through education, embodied, and geographically contextualised.

While Wynne engages in breaking down the dichotomy between expert and lay knowledge, Horlick-Jones (Citation2005); Horlick-Jones, Walls, and Kitzinger (Citation2007); Horlick‐Jones (Citation2005) suggest a ‘bricolage’ of knowledges people draw on when dealing with risk in their everyday lives and for empirical studies to examine the processes to combine multiple knowledges in modes of reasoning. Zinn (Citation2008, Citation2016) continues Wynne, Kitzinger and Horlick-Jones’ argument by including so-called ‘in-between strategies’ of trust, intuition, and emotion as important knowledges for everyday reasoning by both laypeople and experts. Drawing on Weber’s typology of actions, Zinn argues that in-between strategies have their own logic as reasonable practices that combine with instrumental practices (Zinn Citation2016, p. 358). He broadens the rational – irrational dichotomy (no actor acts on one reasoning alone and there is not a scale of reasonings) by adding trust, intuition and emotion to the social and cultural bricolage for reasoning (all actor acts with different reasonings in different contexts and moments in time).

I argue that practice theory adds significantly to the above work of theorising forms of knowledge, by claiming that the practical activities that make up everyday life are part of the shared practices and not the individual mind and that they are predominantly routinised and embodied. From a practice perspective, risk is always understood as parts of practices performed as routine and without much, if any, conscious evaluation at all. Dealing with risk (e.g. by trust in institutions, by doing what feels right) is seen as woven into the practices carried out often automatically, as they are integrated seamlessly with past and present experience. Routines are seen as carriers of cultural logics and work as guidelines for how to navigate through everyday life. They can then be understood as procedures of tacit knowledge and embodied skills that are associated with the performance of a practice. When the practitioner engages in a practice, these procedures are learned and used to accomplish the practice (Schatzki Citation1996; Southerton Citation2013).

On the topic of risk-taking and routine, Bunn (Citation2017) argues that the most common view is that people involve themselves in high-risk activities by the sheer attraction of taking risks (Lyng’s (Citation2004) concept of edgework, for example). Using high-altitude mountain climbing as his case in point, Bunn shows that climbers gradually embody the practical understandings of climbing through related outdoor practices that were less risky yet built up skills to be used in climbing. The practitioners were navigating through the trajectories of a climbing practice, and progressively managing the risks related to high-altitude climbing. Gradually, the climbers performed actions that were oriented towards the goals of the field of climbing, a process that might never be reflexive (Bunn Citation2017, p. 588). People are then not predisposed risk-takers, or in the pursuit of risk, instead, they are partaking in a gradual routinisation through learning and mastering the practice by performing interrelated practices. This does not mean that high-altitude climbing is not risky, but it shows how people take on that risk. Risk is made ordinary through the routinisation of practices that involve some kind of risk (see also Zinn Citation2019; Citation2020 on the key dimensions of risk-taking).

Socio-materiality

The previous sections discussed ‘the social’ in terms of actions and knowledges. However, materialities are as important in practice-oriented studies. The ‘material turn’ or ‘new materialism’ in social theory has since the 1990s aimed to break through dichotomies of mind and matter, culture and nature, as well as to understand the world through symmetrical material and semiotic assemblages or networks, rather than casual structures (Healy Citation2004; Van der Tuin and Dolphijn Citation2010). With inspiration from STS (Asdal, Brenna, and Moser Citation2001) and Actor Network Theory (ANT) (Latour Citation2005), practice theory brings forth different forms of materialities, ranging from spatial site to infrastructures and technologies, objects and products, and the human body, acting as intrinsic parts of all social practices (Reckwitz Citation2002b; Shove, Pantzar, and Watson Citation2012). In practice theory, the social world cannot be understood without connecting it to the material world. It does not form a mere background for where the social is performed, rather it is actively shaping the social (Reckwitz Citation2002a). Materials are understood and used by practitioners according to shared norms of how to skillfully use them, and materials themselves can be said to come with predefined scripts that are performed or challenged by practitioners (Akrich Citation1992).

In risk research, the material turn has been evident particularly in environmental and health risk studies (Nygren, Olofsson, and Öhman Citation2019). In geography, the spatial specificity of risk is researched as ‘risk scapes’, defined by Müller-Mahn, Everts, and Stephan (Citation2018) as landscapes of risk that exist in relation to practice or as socially produced temporal-spatial phenomena. Their key point is that place should not be treated as an external entity of material objects and infrastructures, but something that is experienced and made sense of through a plurality of practices, making the place itself plural. Depending on which practices are performed within a certain place, what is perceived as risky differs. November (Citation2008), for example, studies fire risk management and demonstrates that the risk of fire in a city is perceived differently depending on which type of expert practices that are performed; those of firefighters, city planners and architects, or inhabitants in the area.

Jacobsen (Citation2013) study health risks through hygiene practices in domestic kitchens and how the materialities of these practices produce or prevent food risks. Materialities of kitchen hygiene practices include the kitchen itself (a spatial site), which comes with a script of positioning its parts (forming an infrastructure); the sink, oven, fridge, cabinets and so on (products), that have a cultural history and that give us a certain way of performing food handling practices, such as how cooking is done and done safely. Moreover, Jacobsen frames single products as ‘ordering devices’. These devices help practitioners in managing food safety in the kitchen. Using a cutting board to place and cut chicken on, that can easily be washed, is one way of minimising the risk of food-related illness. Hebrok and Heidenstrøm (Citation2019) found that date labelling on products can function as an ordering device, indicating when a food item might be less safe to eat. However, the label confuses as much as it orders. Consumers use their experiential competences, as well as their senses – seeing, smelling, and tasting – to assess whether the product is too risky to consume. This creates a problem when the label does not match the information given by using their competences. What often ends up happening is that the product is left in the fridge until it produces certain signs of inedibility such as mould or a bad smell. Then, it is a risk and can be thrown away ().

In sum, these examples show that food safety is, as Jacobsen (Citation2013) phrases it:

Taken care of, not necessarily adequately, but nevertheless taken care of. In other words; people realize the potential dangers of cooking but act as if they are taken care of by means of routines, machines and various external agencies. These precautions may be one reason why people are so calm on these issues. They may function as an excuse in the sense that it becomes possible and convenient, even necessary, not to think about food safety at every turn.

Understanding risk as part of socio-material relationships makes risk a 'dynamic entity', according to Healy (Citation2004). By that, he means that the world should be understood as dynamic interactions of both human and non-human actors. Risk is then not a property on its own, it only exists because of these dynamic interactions. A practice theory toolbox of competences, meanings, and materials provides a comprehensible framework for studying these dynamic interactions empirically.

Analytical starting point: Practices of interest and intersecting practices

Practices are routinised types of social activity that are made up of interconnected elements (materials, meanings, competences), and that are further interconnected with other practices in time or place. Applying this understanding to risk research means that risk is understood as an outcome of the types of practices people engage in and the way they engage in them. Studying how practices emerge, endure and disappear over time, how they relate to other practices and make up larger bundles of interlinked practices, is the core of practice-oriented analyses (Meier, Warde, and Holmes Citation2018).

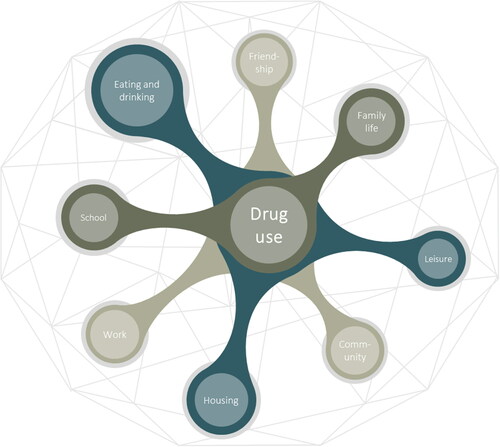

According to Maller and Strengers (Citation2011; Citation2012), we can take our analytical starting point in what they define as ‘practices of interest’ and the practices that intersect with those when we orient our empirical studies towards practices. shows an example of some practices of interest and intersecting practices in the study of drug use, drawing on the findings of Hennell (Citation2017), Bengtsson and Ravn (Citation2018) and Crawshaw and Bunton (Citation2009).

The interplay between different practices that might occur at the same time, or depend on others, must be considered as important as the primary action of drug intake. A practice approach to drug use would encourage accounts of how these different practices work together and how elements within these practices are configured and reconfigured through performances over time. With an understanding of drug use practices, one could also study a risk of interest, such as the risk of drug addiction, and discuss how intersecting practices relate to that risk. Cetina, Schatzki, and Von Savigny (Citation2001) argue for looking at ‘bundles of practices’ that are interwoven and sustained through habitual temporal sequences that are performed by practitioners within a social context. Sequences relevant for drug use might be the weekend party, which must be understood in relation to work-life and the organization of work hours and leisure hours.

Corvellec (Citation2009) makes a further important point by arguing that most risk management studies are conducted in institutions that explicitly deal with risk and in contexts where risk considerations are expected to be present. Corvellec studied risk management in Skånetrafiken, a regional transport company in the southern part of Sweden, based on an absence of risk vocabulary in their official documents. The study shows that risk management was deeply embedded in managerial practices, including how the company designed contracts, engaged in dialogue, and performed its responsibilities towards employees and customers. Risk management can thus be non-explicit and without any reference to risk. We might also ask whether traditional risk management is necessary when existing organisational practices already deal with the main risks.

Associated areas including disaster studies (Andersen Citation2008; Silvast Citation2017), crisis management studies (Danielsson Citation2016; Oscarsson and Danielsson Citation2018), and preparedness studies, have perhaps to a larger extent than risk research oriented empirical studies towards practices and intersecting practices. Preparedness studies, for example, have hitherto been dominated by what Heidenstrøm (Citation2020) refers to as ‘formal preparedness’. Here, preparedness is defined a priori according to risk and crisis management policies in a top-down and normative manner, claiming readiness as the ideal preparedness. Readiness is then operationalised pragmatically in the form of concrete attributes that individuals hold to varying degrees. Utilizing a practice-oriented framework, forms of embodied competences, such as previous experience, local geographical knowledge, and skills to use objects and technologies are highlighted as important everyday preparedness resources (Heidenstrøm and Rhiger Hansen Citation2020). Often, these competences are seemingly unrelated to preparedness and formed by routinised practices such as leisure activities and local place-based mobility patterns (Heidenstrøm and Kvarnlöf Citation2017). The scope of preparedness is thus expanded to include ‘informal resources’, making the argument that even though people do not think about or engage in explicit preparedness activities, they can be quite well-prepared (Heidenstrøm and Throne-Holst Citation2020). In crisis management studies, the practice perspective has been used to highlight the routinised work professionals are doing by improvising, adapting, and normalising crisis management to fit a wider social and cultural context, and how these practices deviate from traditional crisis management (Oscarsson and Danielsson Citation2018).

Conclusion: a sensibility for practice

Sedlačko (Citation2017) proposes a ‘sensibility for practice’ in empirical studies. It involves focussing on actions rather than actors, on everydayness, on structuring and ordering of practices, and doings as well as sayings. In this article, I have presented a sensibility for practice within the context of risk research, exploring how studies of risk might look through the lens of practices.

A first main point is that individually oriented models draw our attention to the individual actor’s more or less reflexive thoughts and decisions about risk concerning certain subjects, such as the risk of contracting a disease from a kitchen cutting board. Social practice theory draws our attention to how individuals through their everyday practices also deal with many risks, often unreflexively, with the use of tacit knowledge and materials, and without any reference to risk.

Second, using social practice theory to study risk means that risk is understood as the outcome of participating in practices and thus embedded in the practices themselves, and never external to them. In a research context, it would mean that rather than look at individuals as risky subjects or researching individuals' risk behaviours, understandings, emotions, sense-makings and so on, we must see individuals as carriers of socially and culturally shared practices that involve risk.

Third, seeing risk as the outcome of participating in practices means that in a social practice perspective, risk is researched in the context of the mundanity and ordinariness of day-to-day life. Researching risk as mundane will imply digging deeper into the sort of risks that we take for granted in performing our practices, that are there, performed by us without any reflection.

Finally, to account for the materialities that partake in these practices means to acknowledge the places the practices are situated in, and the materials, things, objects, and technologies that are actively partaking in shaping practices, and how they are filled with risk in different ways.

It is important to note that the headings used to structure this article do not represent mutually exclusive categories. It is for example, as Archer (Citation2010) points to, possible to explore both reflexivity and routinisation, and according to Tharaldsen and Haukelid (Citation2009), it is even possible to integrate behaviourism and cultural studies in risk analyses. However, I believe the structure is fruitful for highlighting what direction social practice theory would draw social science risk research in.

Nonetheless, practice theory has some significant limitations, particularly when used in empirical studies. It is predominantly used to stress the habitual and tends to understate reflexivity, and it is more preoccupied with doings than sayings. Moreover, few practice-oriented studies have engaged with power relations (Watson Citation2017). A practice-orientation would indeed benefit from being used in combination with concepts such as governmentality and intersectionality that are at the core of risk research (Nygren, Öhman, and Olofsson Citation2015).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Ajzen, I., and M. Fishbein. 1977. “Attitude-Behavior Relations: A Theoretical Analysis and Review of Empirical Research.” Psychological Bulletin 84 (5): 888–918. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.84.5.888.

- Akrich, M. 1992. “The de-Scription of Technical Objects.” In Shaping Technology/Building Society, edited by W. E. Bijker & J. Law, 205–224. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Alaszewski, A., and K. Coxon. 2008. “The Everyday Experience of Living with Risk and Uncertainty.” Health, Risk & Society 10 (5): 413–420. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13698570802383952.

- Andersen, N. B. 2008. Risici og ramthed. Vedtagelser, performance og definitionsmagt. Et studie af kommunikationsprocesser mellem myndigheder, borgere og medier i forbindelse med ulykken på N.P. Johnsens Fyrvaerkerifabrik i Kolding i 2004 samt orkan og højvandsvarslet i Skive i 2005. Roskilde.

- Archer, M. S. 2010. “Routine, Reflexivity, and Realism.” Sociological Theory 28 (3): 272–303. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9558.2010.01375.x.

- Asdal, K., B. Brenna, and I. Moser. 2001. Teknovitenskapelige Kulturer [Techno Scientific Cultures]. Oslo: Spartacus.

- Bagguley, P. 2003. “Reflexivity Contra Structuration.” Canadian Journal of Sociology / Cahiers Canadiens de Sociologie 28 (2): 133–152. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/3341456.

- Beck, U. 1992. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. London: Sage Publications.

- Beck, U., A. Giddens, and S. Lash. 1994. Reflexive Modernization: Politics, Tradition and Aesthetics in the Modern Social Order. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Benadusi, M. 2014. “Pedagogies of the Unknown: Unpacking ‘Culture’in Disaster Risk Reduction Education.” Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 22 (3): 174–183. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12050.

- Bengtsson, T. T., and S. Ravn. 2018. Youth, Risk, Routine: A New Perspective on Risk-Taking in Young Lives. London: Routledge.

- Blue, S., E. Shove, C. Carmona, and M. P. Kelly. 2016. “Theories of Practice and Public Health: understanding (un) Healthy Practices.” Critical Public Health 26 (1): 36–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09581596.2014.980396.

- Boholm, Å., H. Corvellec, and M. Karlsson. 2012. “The Practice of Risk Governance: lessons from the Field.” Journal of Risk Research 15 (1): 1–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2011.587886.

- Bourdieu, P. 2013 [1984]. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. London: Routledge.

- Brown, P. 2016. “From Rationalities to Lifeworlds: Analysing the Everyday Handling of Uncertainty and Risk in Terms of Culture, Society and Identity.” Health, Risk & Society 18 (7–8): 335–347. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13698575.2016.1271866.

- Bunn, M. 2017. “I’m Gonna Do This over and over and over Forever!’: Overlapping Fields and Climbing Practice.” International Review for the Sociology of Sport 52 (5): 584–597. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690215609785.

- Butler, J. 1990. Gender Trouble and the Subversion of Identity. New York: Routledge.

- Cetina, K. K., T. R. Schatzki, and E. Von Savigny. 2001. The Practice Turn in Contemporary Theory. London: Routledge.

- Corvellec, H. 2009. “The Practice of Risk Management: Silence is Not Absence.” Risk Management 11 (3–4): 285–304. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/rm.2009.12.

- Crawshaw, P., and R. Bunton. 2009. “Logics of Practice in the ‘Risk Environment’.” Health, Risk & Society 11 (3): 269–282. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13698570902906447.

- Danielsson, E. 2016. “Following Routines: A Challenge in Cross‐Sectorial Collaboration.” Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 24 (1): 36–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12093.

- Dawson, M. 2012. “Reviewing the Critique of Individualization:The Disembedded and Embedded Theses.” Acta Sociologica 55 (4): 305–319. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699312447634.

- Douglas, M. 2002. Risk and Blame. New York: Springer.

- Douglas, M., and A. Wildavsky. 1982. Risk and Culture: An Essay on the Selection of Technical and Environmental Dangers. California: University of California Press.

- Giddens, A. 1984. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration. California: University of California Press.

- Giddens, A. 1991. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. California: Stanford University Press.

- Hargreaves, T. 2011. “Practice-Ing Behaviour Change: Applying Social Practice Theory to Pro-Environmental Behaviour Change.” Journal of Consumer Culture 11 (1): 79–99. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540510390500.

- Healy, S. 2004. “A ‘Post‐Foundational’interpretation of Risk: Risk as ‘Performance.” Journal of Risk Research 7 (3): 277–296. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1366987042000176235.

- Hebrok, M., and N. Heidenstrøm. 2019. “Contextualising Food Waste Prevention. Decisive Moments within Everyday Practices.” Journal of Cleaner Production 210: 1435–1448. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.11.141.

- Heidenstrøm, N. 2020. “Preapredness in Everyday Life: A Social Practice Perspective.” PhD diss., University of Oslo, Oslo.

- Heidenstrøm, N., and L. Kvarnlöf. 2017. “Coping with Blackouts. A Practice Theory Approach to Household Preparedness.” Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 26 (2): 272–282. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12191.

- Heidenstrøm, N., and A. Rhiger Hansen. 2020. “Embodied Competences in Household Preparedness: A Mixed Methods Research.” Energy Research & Social Science 66: 101498. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101498.

- Heidenstrøm, N., and H. Throne-Holst. 2020. “‘Someone Will Take Care of It.’ Households’ Understanding of Their Responsibility to Prepare for and Cope with Electricity and ICT Infrastructure Breakdowns.” Energy Policy 144:111676.

- Hennell, K. 2017. A Proper Night Out': Alcohol and Risk among Young People in Deprived Areas in North West England. Lancaster: Lancaster University.

- Henwood, K., N. Pidgeon, S. Sarre, P. Simmons, and N. Smith. 2008. “Risk, Framing and Everyday Life: Epistemological and Methodological Reflections from Three Socio-Cultural Projects.” Health, Risk & Society 10 (5): 421–438. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13698570802381451.

- Horlick-Jones, T. 2005. “On ‘Risk Work’: Professional Discourse, Accountability, and Everyday Action.” Health, Risk & Society 7 (3): 293–307. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13698570500229820.

- Horlick-Jones, T., and A. Prades. 2009. “On Interpretative Risk Perception Research: Some Reflections on Its Origins; Its Nature; and Its Possible Applications in Risk Communication Practice.” Health, Risk & Society 11 (5): 409–430. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13698570903180448.

- Horlick-Jones, T., J. Walls, and J. Kitzinger. 2007. “Bricolage in Action: learning about, Making Sense of, and Discussing, Issues about Genetically Modified Crops and Food.” Health, Risk & Society 9 (1): 83–103. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13698570601181623.

- Horlick‐Jones. T. 2005. “Informal Logics of Risk: Contingency and Modes of Practical Reasoning.” Journal of Risk Research 8 (3): 253–272. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1366987042000270735.

- Jacobsen, E. 2013. Dangerous Liaisons. Domestic Food Safety Practices. Oslo: Centre of technology, Innovation and Culture. Faculty of Social Sciences. University of Oslo.

- Jasanoff, S. 1998. “The Political Science of Risk Perception.” Reliability Engineering & System Safety 59 (1): 91–99. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0951-8320(97)00129-4.

- Jasanoff, S. 1999. “The Songlines of Risk.” Environmental Values 8 (2): 135–152. doi:https://doi.org/10.3197/096327199129341761.

- Jones, B. D. 1999. “Bounded Rationality.” Annual Review of Political Science 2 (1): 297–321. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.2.1.297.

- Kahneman, D. 2011. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Latour, B. 2005. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lizardo, O. 2009. “Is a “Special Psychology” of Practice Possible? From Values and Attitudes to Embodied Dispositions.” Theory & Psychology 19 (6): 713–727. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354309345891.

- Lupton, D. 2013. Risk. New York: Routledge.

- Lyng, S. 2004. Edgework: The Sociology of Risk-Taking. New York: Routledge.

- Maller, C. J., and Y. Strengers. 2011. “Housing, Heat Stress and Health in a Changing Climate: promoting the Adaptive Capacity of Vulnerable Households, a Suggested Way Forward.” Health Promotion International 26 (4): 492–498. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dar003.

- Maller, C. 2012. “Using Social Practice Theory to Understand Everyday Life in a Master-Planned Estate: outcomes for Health and Wellbeing.” Paper Presented at the Annual Conference of the Australian Sociological Association: Emerging and Enduring Inequalities.

- Markowitz, H. 1952. “Portfolio Selection.” The Journal of Finance 7 (1): 77–91.

- Meier, P. S., A. Warde, and J. Holmes. 2018. “All Drinking is Not Equal: how a Social Practice Theory Lens Could Enhance Public Health Research on Alcohol and Other Health Behaviours.” Addiction 113 (2): 206–213. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13895.

- Müller-Mahn, D., J. Everts, and C. Stephan. 2018. “Riskscapes revisited-Exploring the Relationship between Risk, Space and Practice.” Erdkunde 72 (3): 197–214. doi:https://doi.org/10.3112/erdkunde.2018.02.09.

- Nicolini, D. 2012. Practice Theory, Work, and Organization: An Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nicolini, D. 2017. “Practice Theory as a Package of Theory, Method and Vocabulary: Affordances and Limitations.” In Methodological Reflections on Practice Oriented Theories, edited by M. Jonas, B. Littig, & A. Wroblewski, 19–34. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- November, V. 2008. “Spatiality of Risk.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 40 (7): 1523–1527. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/a4194.

- Nygren, K. G., S. Öhman, and A. Olofsson. 2015. “Doing and Undoing Risk: The Mutual Constitution of Risk and Heteronormativity in Contemporary Society.” Journal of Risk Research 20 (3): 418–432. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2015.1088056.

- Nygren, K. G., A. Olofsson, and S. Öhman. 2019. A Framework of Intersectional Risk Theory in the Age of Ambivalence. Cham: Springer.

- Olofsson, A., and J. O. Zinn. 2018. Researching Risk and Uncertainty. Methodologies, Methods and Research Strategies. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Olofsson, A., J. O. Zinn, G. Griffin, K. G. Nygren, A. Cebulla, and K. Hannah-Moffat. 2014. “The Mutual Constitution of Risk and Inequalities: Intersectional Risk Theory.” Health, Risk & Society 16 (5): 417–430. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13698575.2014.942258.

- O'Malley, P. 2009. “Governmentality and Risk.” In Social Theories of Risk and Uncertainty: An Introduction, edited by J. O. Zinn, 52–75. London: Blackwell.

- O'Malley, P. 2013. “Uncertain Governance and Resilient Subjects in the Risk Society.” Oñati Socio-Legal Series 3 (2):16.

- Ortner, S. B. 1984. “Theory in Anthropology since the Sixties.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 26 (1): 126–166. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0010417500010811.

- Oscarsson, O., and E. Danielsson. 2018. “Unrecognized Crisis Management—Normalizing Everyday Work: The Work Practice of Crisis Management in a Refugee Situation.” Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management 26 (2): 225–236. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5973.12176.

- Parkhill, K. A., N. F. Pidgeon, K. L. Henwood, P. Simmons, and D. Venables. 2010. “From the Familiar to the Extraordinary: local Residents’ Perceptions of Risk When Living with Nuclear Power in the UK.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 35 (1): 39–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-5661.2009.00364.x.

- Postill, J. 2010. “Introduction.” In Theorising Media and Practice, edited by B. Bräuchler & J. Postill, Vol. 4, 1–32. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Reckwitz, A. 2002a. “The Status of the “Material” in Theories of Culture: From “Social Structure” to “Artefacts.” Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 32 (2): 195–217. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5914.00183.

- Reckwitz, A. 2002b. “Toward a Theory of Social Practices. A Development in Culturalist Theorizing.” European Journal of Social Theory 5 (2): 243–263. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/13684310222225432.

- Reith, G. 2004. “Uncertain Times: The Notion of ‘Risk’and the Development of Modernity.” Time & Society 13 (2–3): 383–402. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X04045672.

- Røpke, I. 2009. “Theories of Practice—New Inspiration for Ecological Economic Studies on Consumption.” Ecological Economics 68 (10): 2490–2497. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2009.05.015.

- Schatzki, T. 1996. Social Practices: A Wittgensteinian Approach to Human Activity and the Social. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schatzki, T. 1997. “Practices and Actions: A Wittgensteinian Critique of Bourdieu and Giddens.” Philosophy of the Social Sciences 27 (3): 283–308. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/004839319702700301.

- Schatzki, T. 2001. “Introduction: Practice Theory.” In The Practice Turn in Contemporary Theory, edited by T. Schatzki, K. K. Cetina, and E. Savigny, 10–23. London: Routledge.

- Schatzki, T. 2002. The Site of the Social. A Philosophical account of the Constitution of Social Life and Change. Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press.

- Sedlačko, M. 2017. “Conducting Ethnography with a Sensibility for Practice.” In Methodological Reflections on Practice Oriented Theories, edited by M. Jonas, B. Littig, & A. Wroblewski, 47–60. New York: Springer.

- Shove, E. 2009. “Everyday Practice and the Production and Consumption of Time.” In Time, Consumption, and Everyday Life. Practice, Materiality and Culture, edited by E. Shove, F. Trentmann, and G. Walker, 17–33. Oxford: Berg.

- Shove, E. 2010. “Beyond the ABC: climate Change Policy and Theories of Social Change.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 42 (6): 1273–1285. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/a42282.

- Shove, E., M. Pantzar, and M. Watson. 2012. The Dynamics of Social Practice: Everyday Life and How It Changes. London: Sage Publications.

- Silvast, A. 2017. Making Electricity Resilient: Risk and Security in a Liberalized Infrastructure. London: Routledge.

- Slovic, P. 1987. “Perception of Risk.” Science (New York, N.Y.) 236 (4799): 280–285. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.3563507.

- Southerton, D. 2013. “Habits, Routines and Temporalities of Consumption: From Individual Behaviours to the Reproduction of Everyday Practices.” Time & Society 22 (3): 335–355. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0961463X12464228.

- Spurling, N. J., A. McMeekin, D. Southerton, E. Shove, and D. Welch. 2013. “Interventions in practice: reframing policy approaches to consumer behaviour.” http://www.sprg.ac.uk/uploads/sprg-report-sept-2013.pdf

- Strengers, Y., and C. Maller. 2014. Social Practices, Intervention and Sustainability: Beyond Behaviour Change. London: Routledge.

- Tharaldsen, J. E., and K. Haukelid. 2009. “Culture and Behavioural Perspectives on Safety–towards a Balanced Approach.” Journal of Risk Research 12 (3–4): 375–388. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13669870902757252.

- Tulloch, J., and D. Lupton. 2003. Risk and Everyday Life. Thousand Oakes: Sage Publications.

- Van der Tuin, I., and R. Dolphijn. 2010. “The Transversality of New Materialism.” Women: a Cultural Review 21 (2): 153–171.

- Walker, G. 2014. “The Dynamics of Energy Demand: Change, Rhythm and Synchronicity.” Energy Research & Social Science 1: 49–55. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2014.03.012.

- Warde, A. 2005. “Consumption and Theories of Practice.” Journal of Consumer Culture 5 (2): 131–153. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540505053090.

- Warde, A. 2014. “After Taste: Culture, Consumption and Theories of Practice.” Journal of Consumer Culture 14 (3): 279–303. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1469540514547828.

- Warde, A. 2016a. Consumption: A Sociological Analysis. New York: Springer.

- Warde, A. 2016b. The Practice of Eating. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Watson, M. 2017. “Placing Power in Practice Theory.” In The Nexus of Practices: Connections, Constellations, Practitioners, edited by A. Hui, T. Schatzki, E. Shove, 169–182. Boca Raton: CRC Press.

- Welsh, I., and B. Wynne. 2013. “Science, Scientism and Imaginaries of Publics in the UK: Passive Objects, Incipient Threats.” Science as Culture 22 (4): 540–566. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14636778.2013.764072.

- Whitford, J. 2002. “Pragmatism and the Untenable Dualism of Means and Ends: Why Rational Choice Theory Does Not Deserve Paradigmatic Privilege.” Theory and Society 31 (3): 325–363. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1016232404279.

- Wills, W. J., A. Meah, A. M. Dickinson, and F. Short. 2015. “I Don’t Think I Ever Had Food Poisoning’. A Practice-Based Approach to Understanding Foodborne Disease That Originates in the Home.” Appetite 85: 118–125. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2014.11.022.

- Wynne, B. 1996. “May the Sheep Safely Graze? A Reflexive View of the Expert-Lay Knowledge Divide.” In Risk, Environment and Modernity: Towards a New Ecology, edited by S. Lash, B. Szerszynski, & B. Wynne, 44–83. London: Sage Publications.

- Zinn, J. O. 2008. “Heading into the Unknown: Everyday Strategies for Managing Risk and Uncertainty.” Health, Risk & Society 10 (5): 439–450. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13698570802380891.

- Zinn, J. O. 2015. “Towards a Better Understanding of Risk-Taking: Key Concepts, Dimensions and Perspectives.” Health, Risk & Society 17 (2): 99–114.

- Zinn, J. O. 2016. “‘In-between’ and other reasonable ways to deal with risk and uncertainty: A review article.” Health, Risk & Society 18 (7–8): 348–366. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13698575.2016.1269879.

- Zinn, J. O. 2019. “The Meaning of Risk-Taking–Key Concepts and Dimensions.” Journal of Risk Research 22 (1): 1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2017.1351465.

- Zinn, J. O. 2020. Understanding Risk-Taking. London: Springer.