Abstract

Encouraging people to wear a facemask in situations where social distance is not possible is a relatively low-cost and low-impact measure to protect people from infections with SARS-CoV-2. Thus, the present study investigated various barriers and drivers regarding people’s self-reported wearing of protective facemasks in mandatory and non-mandatory situations. Data from a longitudinal study with four waves in Switzerland was used (N = 728). The findings show that the compliance with “wearing a facemask” increased over the duration of the pandemic, particularly after the lockdown measures were lifted. More importantly, the study shows that perceived effectiveness of wearing a facemask are important drivers, while various perceived costs (e.g., financial, comfort) act as barriers. Risk communicators should be aware that the communicated effectiveness (self or others) is associated with people’s willingness to wear facemasks in public, independently of the involved and perceived costs or whether wearing a facemask is mandatory or not.

Supplemental data for this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2022.2038244 .

1. Introduction

Wearing a facemask has been identified as one of the measures to curtail the infection rate in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic (subsequently: Covid-19 pandemic) and most countries, including Switzerland, have recommendations or enforced rules on wearing facemasks in public spaces (World Health Organization Citation2021; Federal Office of Public Health Citation2021; Leung et al. Citation2020; Lyu and Wehby Citation2020). As the pandemic is ongoing, it gets increasingly difficult to enforce strict lockdown measures, such as the closing of shops and restaurants, the restriction of on-site teaching or working. These measures put a lot of strain on people’s physical and psychological well-being, the educational system, as well as the economy (e.g., Tang et al. Citation2021; Sibley et al. Citation2020; Nicola et al. Citation2020; Mukhtar Citation2020). In comparison, encouraging people to wear a facemask in situations where social distance is not possible, is a relatively low-cost and low-impact measure to protect people from infections. ‘Wearing a facemask’ is an interesting health behaviour for social scientific research for several reasons outlined below.

In Switzerland and many other countries, there existed a shortage, as facemask supplies were insufficient at the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic (Loser Citation2020). As SARS-CoV-2 emerged as a new virus, there existed substantial scientific uncertainty regarding transmission routes and effectiveness of the facemasks to protect against an infection (Setti et al. Citation2020; Scheid et al. Citation2020). Relevant from a cost-benefit perception, little was known about potential negative psychological effects of widespread facemask wearing or about potential lulling effects that lead to reduced social distancing while wearing a facemask (e.g., Carbon Citation2020; Cartaud, Quesque, and Coello Citation2020). Based on the shortage and the need to reserve facemasks for frontline workers, as well as scientific uncertainty, the Swiss government initially recommended that the public should not wear facemasks (February 2020) (Loser Citation2020). This communication strategy changed over the course of a few months, as facemasks became available and scientific evidence of their protective function emerged (April 2020) (Loser Citation2020). By July 2020, it was made compulsory to wear facemasks on public transportation in Switzerland. In many Western countries, Switzerland among them, the recommended wearing of facemasks sparked public controversy and was politicised (Thacker Citation2020; Scheid et al. Citation2020). For these reasons, the goal of the present study was to understand the barriers and drivers to wearing a facemask in a Western society, namely Switzerland. Moreover, this study presents longitudinal data on the health behaviour ‘wearing a facemask’ from the onset of the pandemic to the lifting of most lockdown measures in 2020.

As no pandemic after the Spanish flu had such a dramatic impact on Western societies, facemask wearing was highly uncommon in these cultures (Wang et al. Citation2020; Dryhurst et al. Citation2020). Thus, scientific literature on the barriers and drivers of wearing a facemask from before the Covid-19 pandemic mostly focuses on Asian societies, on other pathogens (i.e., influenza, H1N1 virus) or on hypothetical pandemics (Barr et al. Citation2008; Lau et al. Citation2009; Cowling et al. Citation2010; Lau et al. Citation2010; Van Cauteren et al. Citation2012). In these studies, the lack of risk awareness and risk perception regarding the likelihood or severity of an infection with the pathogen were found to be barriers to wearing a facemask (Barr et al. Citation2008; Cowling et al. Citation2010; Lau et al. Citation2010; Brug, Aro, and Richardus Citation2009; Leppin and Aro Citation2009). Furthermore, perceived costs (e.g., financial, physical, psychological, social) were found to reduce people’s willingness to wear a facemask (Lau et al. Citation2010; Lau et al. Citation2009). Oppositely, perceived effectiveness of the facemask to avoid infection or a further spread of the disease were investigated as drivers to wearing a facemask (Lau et al. Citation2009).

The currently available literature on the barriers and drivers of people’s willingness to wear protective facemasks against an infection and spread of Covid-19 looked at this issue from a variety of perspectives. Frequently the focus was on people’s perceptions of risk and likelihood of exposure (Svenson et al. Citation2020). Furthermore, personal values, public and political discourse were of interest. In this line, Prichard and Christman (Citation2020) investigated the relationship between authoritarianism and conspiracy beliefs and wearing a facemask. People with higher levels of authoritarianism (i.e., rejection of political plurality, demand for a strong central power) and more expressed conspiracy beliefs were less likely to wear a facemask and were also less concerned about the virus. Similarly, other studies suggested connections between personal values, social and political conservatism and wearing a facemask (Ike et al. Citation2020; Cassino and Besen-Cassino Citation2020; Palmer and Peterson Citation2020; Dryhurst et al. Citation2020). From a (health) psychology perspective, theoretical approaches (e.g., health behaviour models and behaviour change models) were used to understand the health behaviour “wearing a facemask.” These models combine various psychological factors and theories, such as emotions, stigma, or social norms, to predict the intention or actual behaviour (van der Linden and Savoie Citation2020; Pfattheicher et al. Citation2020; van Bavel et al. Citation2020; Kowalski and Black Citation2021). For example, Pfattheicher et al. (Citation2020) found that empathy towards people that are part of the risk group of infection with Covid-19 increased people’s willingness to wear a facemask. In a similar vein, the study by Nakayachi et al. (Citation2020) raised the question, why people wear facemasks despite the fact that they mostly protect others from getting infected. The authors found that risk reduction expectations did not predict facemask wearing, while the perception of this behaviour as an accepted social norm did (Nakayachi et al. Citation2020).

A model that combines the psychological variables summarised in this section is the Protection Motivation Theory (Kowalski and Black Citation2021; Rogers Citation1975; Rogers and Prentice-Dunn Citation1997). It comprises measures of risk perception (Threat Appraisal), personal and social barriers and drivers of wearing a facemask (Coping Appraisal), and perceptions about the effectiveness of protective measures (Response Efficacy). These three major predictive factors, along with sociodemographic and contextual factors, are hypothesised to impact protection motivation. Applied to the health behaviour of interest, facemask wearing, the Protection Motivation Theory hypothesises that people are willing to wear a protective facemask if a) they perceive a threat of infection with Covid-19, b) the barriers are less impactful than driver of this behaviour and c) they perceive facemasks as effective to protect themselves and others.

2. Study goals and research questions

In this longitudinal study, people’s perceptions of and willingness to wear a protective facemask during the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic in Switzerland were investigated with a focus on comparing various barriers and drivers. This article presents novel results, as the drivers and barriers of wearing a protective facemask were mostly investigated in isolation in prior studies. This article represents a more comprehensive approach by integrating several different barriers and drivers, and their underlying mechanisms as suggested in the Protection Motivation Theory (Rogers Citation1975; Rogers and Prentice-Dunn Citation1997). The research period of interest ranged from the onset of the pandemic, during the lockdown and during the easing of it, to after the lockdown. After the lockdown, it became mandatory to wear a facemask on public transport in Switzerland. The following research questions (RQ) were of interest:

RQ1: How did the number of people wearing a facemask change over time? In what situations did people wear a facemask?

RQ2: To what degree are the facemasks perceived to protect the own health or protect the health of other people?

RQ3: What variables discriminate between people that wear a facemask in a mandatory (i.e., public transport) and a non-mandatory situation (i.e., supermarket)?

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Study design and sample

This article is based on data from a longitudinal research project that was realised in the German-speaking part of Switzerland during the 2020 Covid-19 pandemic.Footnote1 The participants were recruited with the support of a professional market research company (respondi, Koeln, DE) and offered informed consent prior to participation. The same participants were invited to participate in a total of four data collection waves and were incentivised financially for participation. Data was collected within an online questionnaire distributed via email by the market research company. To ensure a heterogenous sample, quota sampling for age and gender was applied (i.e., equal gender distribution, five equally distributed age groups between 20 and 69 years of age). The first wave (w1, collected between March 27th and April 4th 2020) coincided with the announcement of a national lockdown due to the rapidly growing number of cases (e.g., closure of restaurants and shops, urgent call to remain at home if possible). The second (w2, April 16th to 26th 2020) and the third wave (w3, May 20th to 29th 2020) coincided with the announcement of and the gradual lifting of the lockdown measures respectively (e.g., opening of restaurants and shops). The fourth and final wave (w4, July 9th to July 17th 2020) coincided with the lifting of almost all restrictions and the introduction of the compulsory facemask wearing on public transport (from July 6th 2020 onwards). For the final sample, solely the participants were retained that took part in all four waves (more information on the sample structure and drop-out can be found in [references removed for peer review]). This resulted in an overall sample size of N = 728 with n = 386 male participants (53%) and an average age of M = 48 (SD = 13, range 20-69 years of age).

3.2. Materials

Subsequently, the materials for this study are presented. Some of the material was assessed in all four waves (w1-w4), whereas at w4, participants were asked more diverse questions regarding their willingness to wear a facemask, as facemask availability was higher and there existed more situations where people encountered other people outside of their homes.

Over all four waves, the participants were asked whether they had worn a facemask in the past seven days (response format: yes, no or do not know). As the importance of wearing a facemask is dependent on the situation, the participants were further asked to indicate whether a) they had been on public transport in the past seven days, b) went shopping in the past seven days or c) had gone to work outside of their homes (response format for each of the three items: yes, no, do not know). ‘Do not know’ responses were coded as missing values.

As the main variable of interest at w4, the participants were questioned about the frequency of wearing a facemask in a mandatory (i.e., public transport) and in a non-mandatory situation (i.e., supermarket). The following response format was offered: ‘always’ ‘mostly’ ‘every so often’ ‘rarely’ and ‘never’ (the response ‘do not know’ was treated as missing value). Due to the skewed distribution, this variable was recoded for mandatory situation into people that always wear a facemask (1) and people that do not always wear a mask on public transport (0). For non-mandatory situation, the variable was also recoded into people that always or mostly wear a facemask (1) and people that every so often, rarely, or never wear a facemask in the supermarket (0), based on the skewed distribution of responses. Participants were also asked to provide other situations in an open response field.

Several variables were assessed that were hypothesised to act as barriers or drivers of wearing a facemask in mandatory and non-mandatory situations.

First, sex (response format: female, male), age (response format: open response field) and education (response format: none, mandatory schooling, apprenticeship, social year/vocational preparation school, vocational training/apprenticeship, middle school, university of applied sciences, university) were assessed. Sex was coded as female (0) and male (1). Education was recoded into low (0) and high education (1; above middle school). Participants were also asked whether they had any pre-existing conditions that might be associated with a severe progression of infection with Covid-19 (e.g., high blood pressure, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus type II). Pre-existing condition was coded as no pre-existing condition (0) and at least one pre-existing condition (1).

Second, participants’ risk perception was measured with three items. Participants were asked to think of an average adult in their community and compare themselves to that person. Next, they were asked, whether a) it was less or more likely that they got infected with the new coronavirus than that person, b) they were less or more susceptible to the new coronavirus than that person and c) an infection with the new coronavirus would be less or more severe for them than for that person. Response options ranged from 1 to 7 (e.g., 1: ‘less likely’ to 4: ‘equally likely’ to 7: ‘more likely’). The three measures were composed into a risk perception measure by taking the mean over all three items for each participant (α = .79).

Third, the participants were asked to indicate in two separate items whether they disagreed or agreed that the facemask protected a) themselves and b) others (response format: 1 ‘do not agree at all’ to 7 ‘strongly agree’).

Fourth, the participants were presented with a list of different reasons against wearing a facemask. These reasons were collected from previous literature (Lau et al. Citation2010; Barr et al. Citation2008; Van Cauteren et al. Citation2012; Lau et al. Citation2009; Cowling et al. Citation2010) and various sources representing the public discourse (e.g., social media, commentary newspaper articles, reader comments). The included items relate to various psychological mechanisms established in theoretical models from health psychology (e.g., self-efficacy, outcome expectancies, coping appraisal) (Rogers Citation1975; Rogers and Prentice-Dunn Citation1997; Zhang et al. Citation2019). The barriers were introduced with the following sentence: ‘People have various reasons why they do not want to wear a facemask in public despite the recommendations (when you cannot keep your distance, on a crowded train or bus, in a crowded store)’ and were asked to respond on a scale from 1 ‘do not agree at all’ to 7 ‘fully agree.’ presents the 12 included items with means and standard deviations. The 12 items were subjected to a principal component analysis. According to the Kaiser’s criterium and an inspection of the scree plot, a two-dimensional solution was chosen (dimension 1: Eigenvalue: 4.98, 41.49%; dimension 2: Eigenvalue: 1.15, 9.56%). Oblique rotation was applied to account for the likely inter-dependence of factors. A content screening of the items with the highest factor loadings suggested that the first dimension represents the ‘Cost of wearing a facemask’ (e.g., hassle, discomfort, low gain due to low numbers; α = .81) and the second dimension represents ‘Stigma of wearing a facemask’ (e.g., isolation, stigma, lack of social norm, shame; α = .78). One item was removed from the second scale, as it did not fit well into the scale’s topic of stigma (‘It is difficult to put on, wear or take off and dispose of a facemask properly’). The two final scales were built by taking the mean over all items for each person.

Table 1. Reasons against wearing a facemask (range 1 ‘do not agree at all’-7 ‘agree fully’, N = 728).

3.3. Data analysis

All descriptive and multivariate analyses were conducted in SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp Citation2017). The analyses for RQ1 comprised descriptive analysis (i.e., frequencies) and the coding of open responses according to a pre-determined coding scheme (i.e., locations where people wear a facemask). These analyses were based on the data gathered longitudinally from w1 to w4. The analyse for RQ2 comprised a Wilcoxon signed-rank test to assess whether participants agreed more strongly that the facemask protects themselves or protects other from infection. The data for this analysis was assessed at w4. The analyses for RQ3 comprised bivariate correlations (Pearson’s correlations) and logistic regression analyses. The data for this analysis was assessed at w3 (prior facemask wearing) and at w4.

4. Results

4.1. Rq1: wearing a facemask at the start and during the pandemic - change over time

Participants that had neither been on public transport nor went shopping nor went to work outside of their homes in the past seven days were excluded for the following descriptive analysis (excluded: w1: n = 75, w2: n = 69, w3: n = 28, w4: n = 20). This decision was made, because people who stayed at home had no reason to wear a protective facemask. Overall, the number of participants wearing a facemask outside of their homes (on public transport, in shops, at work) increased from w1 to w4. At w1, n = 76 of the participants (11.6%) wore a facemask in the past seven days. At w2 and w3, this number increased to n = 94 (14.3%) and n = 231 (33.0%) respectively. At w4, the majority, namely n = 477 of the participants (67.9%) wore a facemask in the past seven days.

When asked at w4, in what situations – other than when shopping in supermarkets, on public transport – they would wear a facemask, n = 370 participants provided valid responses that were coded into nine categories. Most participants indicated that they also had to wear a facemask at their workplaces (n = 88, 23.8%), followed by visits to service providers (e.g., hairdressers, massage therapy; n = 72, 19.5%), in crowds or other situations where the distance among people cannot be kept (n = 53, 14.3%) and at the doctor, pharmacy or hospital (n = 51, 13.8%). Participants also mentioned travelling abroad (e.g., for shopping in Germany, holidays; n = 34, 9.2%) and visits to family and friends (n = 23, 6.2%). Small numbers of participants mentioned that they only wore a facemask if they are forced to (n = 21, 5.7%), that they avoided situations, where they must wear a facemask (n = 10, 2.7%) or that they put on a facemask as soon as they left their home (n = 10, 2.7%).

4.2. Rq2: perception of the protection offered by the facemask

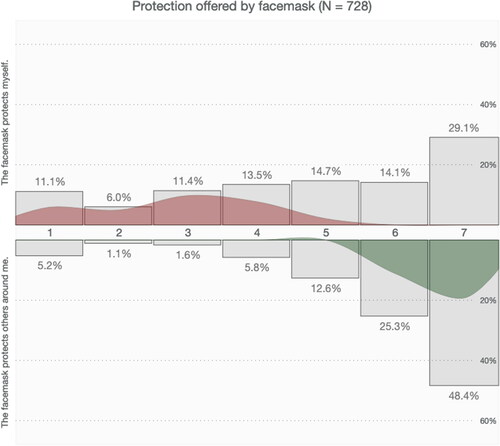

shows the distribution of responses regarding whether the facemask protects the participants themselves and whether it protects others in the environment. Participants agreed more strongly that the facemask protects others in the environment (Median: 6.0) than themselves (Median: 5.0), z = −14.50, p < .001, r = −.54.

Figure 1. V-Plot of the perceived protection offered by the facemask (upper distribution: “The facemask protects myself; lower distribution: The facemask protects others around me; 1: do not agree at all to 7: fully agree; Blumenschein et al. (Citation2020)). Grey bar-chart: relative distribution of responses; coloured distribution: difference distribution of responses).

4.3. Rq3: what differentiates facemask wearers and non-facemask wearers in mandatory and voluntary situations?

shows the bivariate correlations between the continuous independent variables that were included in the logistic regressions. shows the results of the logistic regression analyses for wearing a facemask in mandatory and non-mandatory situations. For the logistic regression with wearing a facemask in mandatory situations (i.e., on public transport) as dependent variable, participants that had not been on public transport in the past 7 days were excluded (n = 373). Of the n = 352 that had been on public transport in the past 7 days, n = 284 (81.4%) indicated to always wear a facemask on public transport, while n = 65 (18.6%) indicated to not always wear a facemask on public transport (n = 2 indicated that they did not know and thus, were excluded from the analysis). For the logistic regression with wearing a facemask in non-mandatory situations (i.e., in shops) as dependent variable, participants that had not gone to the shops were excluded (n = 24). Of the n = 702 that had been in a shop in the past 7 days, n = 125 (17.9%) indicated to wear a facemask mostly or always in shops, while n = 575 (82.1%) indicated to every so often, rarely or never wear a facemask in shops (n = 2 indicated that they did not know and thus, were excluded from the analysis).

Table 2. Bivariate correlations between continuous independent variables included in the logistic regression analyses (N = 728).

Table 3. Logistic regression for wearing a facemask in mandatory (always (1) vs. not always (0; n = 3461) and non-mandatory situations (always or mostly (1) vs. every so often, rarely, never (0; n = 6962).

Participants that perceived more costs and stigma associated with wearing a facemask were less likely to wear a facemask on public transport (mandatory situation), while the perception that facemasks protect others acted as drivers of this behaviour. All other variables, including sociodemographics, having a pre-existing condition, facemask wearing at w3 and risk perception, were not significantly related to whether participants wore a facemask on public transport or not. Moreover, the perception that the facemask protects oneself was not significantly related to wearing a facemask on public transport.

Participants that had worn a facemask at w3 more frequently wore a facemask in shops (non-mandatory situation). Above and beyond prior behaviour, ‘Cost of wearing a facemask’ was a significant barrier, and age, as well as the perception that facemasks protect oneself significant drivers. The perception that facemasks protect others, sex, education, having a pre-existing condition and risk perception were not significantly related to wearing a facemask in shops. To further understand the role of various reasons against wearing a facemask, the Supplementary Material comprises four spider diagrams that present the differences in mean agreement for people wearing and not wearing a facemask in these two situations for each individual item.

5. Discussion

The literature on people’s perceptions and behaviour regarding the current Covid-19 pandemic, and specifically, their willingness to wear protective facemasks, is growing. This study adds three aspects to the current literature: 1) the development of the health behaviour ‘wearing a facemask’ over time, 2) the perceived effectiveness of wearing a facemask, and 3) the importance of various costs and stigma as barriers.

Facemask wearing increased from the onset of the pandemic in March 2020 to the lifting of most lockdown measures after the first pandemic wave in Switzerland. At the onset of the pandemic during w1 and w2, facemasks were difficult to get by, as national facemask supplies were low. Moreover, it was officially not recommended to wear a facemask. The number of people wearing a facemask increased in w3 and more substantially in w4. As it had become mandatory to wear a facemask on public transport during the last wave, most participants had worn a facemask in the past seven days. These findings match the findings of other longitudinal studies that tracked people’s self-reported behaviour over the first wave of the pandemic (Gibson Miller et al. Citation2020; Hornik et al. Citation2021). The Germany Covid-19 Snapshot Monitoring (COSMO Germany) (Betsch, Wieler, and Habersaat Citation2020) found similar increases in the wearing facemasks in public. The varying number of people that do not wear a facemask - despite the increasing scientific evidence that public facemask wearing could reduce the impact of Covid-19 on our society - raises the question of what drives and inhibits this behaviour (Leung et al. Citation2020).

In line with the theoretical prediction of threat and coping appraisals and response efficacy (Rogers Citation1975; Rogers and Prentice-Dunn Citation1997), our results suggest that people weigh the potential effectiveness or benefits of wearing a facemask (e.g., protecting the health of self or others) against the potential costs of wearing it (e.g., discomfort, price, stigma). There exist different barriers and drivers of wearing a facemask in mandatory and non-mandatory situations. On public transport, which in Switzerland represents a mandatory situation, wearing a facemask was driven by the perception that it protects others. To put it differently, the people that do not wear a facemask consistently even though it is prescribed by law, agree to a lesser degree that facemasks protect others compared to people that consistently wear a facemask on public transport. In shops, where wearing a facemask is voluntary, the most relevant driver was the perception that wearing one would protect oneself. Generally, participants agreed more strongly that the facemask protects others instead of themselves, as had been widely discussed in public discourse. Furthermore, older participants reported more frequently to wear a facemask in shops than the other participants. Thus, this study offers further insights into the impact of perceived protection offered by the facemasks is an important driver of wearing one.

Various costs are perceived when wearing a facemask and these costs determine willingness-to-wear a facemask in both mandatory and non-mandatory situations. Participants that did not wear a facemask consistently in a mandatory situation also perceived more stigma compared to participants that always wear a facemask in a mandatory situation. However, the results regarding stigma are not as clear as the results regarding costs of wearing a facemask. This suggests that perhaps the measure for ‘stigma of wearing a facemask’ could be improved in the future. It is possible that the items of the ‘Stigma of wearing a facemask’ scale measure experiences made while wearing a facemask in non-mandatory situations, as well as reasons against wearing a facemask. Particularly, we would recommend separating the behaviour (wearing a facemask) from the perception of this behaviour (communicated to be ineffective) as was done in the recently developed Face Mask Perceptions Scale (FMPS) (Howard Citation2020). The dimensions of the FMPS comprise the sub-dimensions comfort, efficacy doubts, access, compensation, inconvenience, appearance, attention, and independence, which are all aspects included in our scales.

An important limitation of our study is the small number of participants that did not wear a facemask in the mandatory situation all the time. Thus, the results should be interpreted with some caution. Another limitation that should be mentioned regarding our study is the use of self-report to measure facemask wearing. Self-reported measures are associated with some degree of bias, particularly for behaviour that is socially or normatively desirable. Thus, it is possible that we overestimate the number of people that wore a facemask, particularly at wave 3 and 4, where wearing a facemask was recommended. However, we do not think that this bias had a large impact on our findings, as participation was anonymous and people exhibited varying degrees of adhering to social distancing and hygiene measures (Siegrist, Luchsinger, and Bearth Citation2021). Lastly, the results of the logistic regression analyses should be interpreted cautiously, as they are primarily based on cross-sectional data from w4. As infection rates and public recommendations evolves dynamically at the onset of the pandemic, it is assumed that different factors are relevant for the willingness to wear a facemask, as has for example been suggested for the role of risk perception and adherence to protective measures in other European studies (Siegrist, Luchsinger, and Bearth Citation2021; Giritli Nygren and Olofsson Citation2020; Dryhurst et al. Citation2020; Scholz and Freund Citation2021). Future studies should investigate long-term willingness to wear a facemask dynamically in relation to the pandemic situation and public recommendations.

5.1. Conclusion and implications for practice

Broadly, our findings can be summarised as follows. Facemask wearing increased over the course of the Covid-19 pandemic in Switzerland. Despite this increase, some people were not willing to wear a facemask, even when facemask wearing is dictated by law. Our study suggests that people not wearing a facemask do not perceived it as effective and thus, the utility of facemasks does not justify the various costs of wearing a facemask. Hence, we would recommend increasing people’s perceptions of effectiveness to promote the wearing of facemasks in situations where social distancing is not an option. In mandatory situations, facemask wearing is mostly driven by the altruistic desire to protect others, while facemask wearing in non-mandatory situations is only driven by the perception that the mask protects oneself from infection and the personal risk perception (e.g., based on age or pre-existing condition). Risk communicators should be aware that the communicated effectiveness might be associated with people’s willingness to wear facemasks in public, independently of the involved and perceived costs. Particularly, during times when infection rates are high (during acute waves), people will likely be more willing to tolerate the costs of wearing a facemask compared to times where infection rates are low (in between acute waves). Generally, we recommend that people’s reactions to the current epidemiological situation should be considered when communicating protective measures, as people are willing to protect themselves when they see a reason for protection. Thus, entering a dialogue with the public about unwanted public health measures (e.g., facemask wearing in public) is one avenue that should be followed. Doubtlessly though, educational efforts need to be supplemented with rules and regulations that – over time – change the social norms in a country (e.g., on public transport).

Ethical approval

Ethics approval was received for this study by the Ethics Commission of ETH Zurich.

Funding statement

The study was financed with internal funds of the Consumer Behavior group at ETH Zurich.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Larissa Luchsinger for her valuable support in data acquisition and data cleaning.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data is available upon request to the corresponding author.

Notes

1 This article focuses on the included items and scales regarding facemasks. All other data from this project will be presented elsewhere.

References

- Barr, M., B. Raphael, M. Taylor, G. Stevens, L. Jorm, M. Giffin, and S. Lujic. 2008. “Pandemic Influenza in Australia: Using Telephone Surveys to Measure Perceptions of Threat and Willingness to Comply.” BMC Infectious Diseases 8 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-8-117.

- Betsch, Cornelia, Lothar H. Wieler, and Katrine Habersaat. 2020. “Monitoring Behavioural Insights Related to COVID-19.” The Lancet 395 (10232): 1255–1256. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30729-7.

- Blumenschein, Michael, Luka J. Debbeler, Nadine C. Lages, B. Renner, D. A. Keim, and Mennatallah El-Assady. 2020. “v-Plots: Designing Hybrid Charts for the Comparative Analysis of Data Distributions.” Eurographics Conference on Visualization (EuroVis) 39 (3): 1–13.

- Brug, J., A. R. Aro, and J. H. Richardus. 2009. “Risk Perceptions and Behaviour: Towards Pandemic Control of Emerging Infectious Diseases : International research on risk perception in the control of emerging infectious diseases.” International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 16 (1): 3–6. doi:10.1007/s12529-008-9000-x.

- Carbon, C. C. 2020. “Wearing Face Masks Strongly Confuses Counterparts in Reading Emotions.” Frontiers in Psychology 11: 1–8. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.566886.

- Cartaud, Alice, François Quesque, and Yann Coello. 2020. “Wearing a Face Mask against Covid-19 Results in a Reduction of Social Distancing.” Plos One 15 (12): e0243023. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0243023.

- Cassino, D., and Y. Besen-Cassino. 2020. “Of Masks and Men? Gender, Sex, and Protective Measures during COVID-19.” Politics & Gender 16 (4): 1052–1062. doi:10.1017/S1743923X20000616.

- Cowling, B. J., D. M. W. Ng, D. K. M. Ip, Q. Y. Liao, W. W. T. Lam, J. T. Wu, J. T. F. Lau, S. M. Griffiths, and R. Fielding. 2010. “Community Psychological and Behavioral Responses through the First Wave of the 2009 Influenza A(H1N1) Pandemic in Hong Kong.” The Journal of Infectious Diseases 202 (6): 867–876. doi:10.1086/655811.

- Dryhurst, Sarah, Claudia R. Schneider, John Kerr, Alexandra L. J. Freeman, Gabriel Recchia, Anne Marthe van der Bles, David Spiegelhalter, and Sander van der Linden. 2020. “Risk Perceptions of COVID-19 around the World.” Journal of Risk Research 23 (7-8): 994–1006. doi:10.1080/13669877.2020.1758193.

- Federal Office of Public Health. 2021. “Coronavirus: Masks.” Accessed 3 February 2021. https://www.bag.admin.ch/bag/en/home/krankheiten/ausbrueche-epidemien-pandemien/aktuelle-ausbrueche-epidemien/novel-cov/masken.html.

- Gibson Miller, Jilly, Todd K. Hartman, Liat Levita, Anton P. Martinez, Liam Mason, Orla McBride, Ryan McKay, et al. 2020. “Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation to Enact Hygienic Practices in the Early Stages of the COVID-19 Outbreak in the United Kingdom.” British Journal of Health Psychology 25 (4): 856–864. doi:10.1111/bjhp.12426.

- Giritli Nygren, Katarina, and Anna Olofsson. 2020. “Managing the Covid-19 Pandemic through Individual Responsibility: The Consequences of a World Risk Society and Enhanced Ethopolitics.” Journal of Risk Research 23 (7–8): 1031–1035. doi:10.1080/13669877.2020.1756382.

- Hornik, R., A. Kikut, E. Jesch, C. Woko, L. Siegel, and K. Kim. 2021. “Association of COVID-19 Misinformation with Face Mask Wearing and Social Distancing in a Nationally Representative US Sample.” Health Communication 36 (1): 6–14. doi:10.1080/10410236.2020.1847437.

- Howard, Matt C. 2020. “Understanding Face Mask Use to Prevent Coronavirus and Other Illnesses: Development of a Multidimensional Face Mask Perceptions Scale.” British Journal of Health Psychology 25 (4): 912–924. doi:10.1111/bjhp.12453.

- IBM Corp. 2017. IBM Statistics for Macintosh, Version 26.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

- Ike, J. D., H. Bayerle, R. A. Logan, and R. M. Parker. 2020. “Face Masks: Their History and the Values They Communicate.” Journal of Health Communication 25 (12): 990–995. doi:10.1080/10810730.2020.1867257.

- Kowalski, Robin M., and Kelly J. Black. 2021. “Protection Motivation and the COVID-19 Virus.” Health Communication 36 (1): 15–22. doi:10.1080/10410236.2020.1847448.

- Lau, J. T. F., S. Griffiths, K. C. Choi, and C. Q. Lin. 2010. “Prevalence of Preventive Behaviors and Associated Factors during Early Phase of the H1N1 Influenza Epidemic.” American Journal of Infection Control 38 (5): 374–380. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2010.03.002.

- Lau, J. T. F., S. Griffiths, K. C. Choi, and H. Y. Tsui. 2009. “Widespread Public Misconception in the Early Phase of the H1N1 Influenza Epidemic.” The Journal of Infection 59 (2): 122–127. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2009.06.004.

- Leppin, A., and A. R. Aro. 2009. “Risk Perceptions Related to SARS and Avian Influenza: Theoretical Foundations of Current Empirical Research.” International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 16 (1): 7–29. doi:10.1007/s12529-008-9002-8.

- Leung, Nancy H. L., Daniel K. W. Chu, Eunice Y. C. Shiu, Kwok-Hung Chan, James J. McDevitt, Benien J. P. Hau, Hui-Ling Yen, et al. 2020. “Respiratory Virus Shedding in Exhaled Breath and Efficacy of Face Masks.” Nature Medicine 26 (5): 676–680. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0843-2.

- Loser, Philipp. 2020. “Von «Sie nützen nichts» bis zur Pflicht – der grosse Maskenknorz des Bundes [From "They Are of No Use" to Mandatory Wearing - the Great Mask Snag of the Confederation].” In Tagesanzeiger.

- Lyu, Wei, and G. L. Wehby. 2020. “Community Use of Face Masks and COVID-19: Evidence from a Natural Experiment of State Mandates in the US.” Health Affairs (Project Hope) 39 (8): 1419–1425. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00818.

- Mukhtar, S. 2020. “Psychological Health during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic Outbreak.” The International Journal of Social Psychiatry 66 (5): 512–516. doi:10.1177/0020764020925835.

- Nakayachi, K., T. Ozaki, Y. Shibata, and R. Yokoi. 2020. “Why Do Japanese People Use Masks against COVID-19, Even Though Masks Are Unlikely to Offer Protection from Infection?” Frontiers in Psychology 11: 1–15. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01918.

- Nicola, Maria, Zaid Alsafi, Catrin Sohrabi, Ahmed Kerwan, Ahmed Al-Jabir, Christos Iosifidis, Maliha Agha, and Riaz Agha. 2020. “The Socio-Economic Implications of the Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19): A Review.” International Journal of Surgery (London, England) 78: 185–193. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.04.018.

- Palmer, C. L., and R. D. Peterson. 2020. “Toxic Mask-Ulinity: The Link between Masculine Toughness and Affective Reactions to Mask Wearing in the COVID-19 Era.” Politics & Gender 16 (4): 1044–1051. doi:10.1017/S1743923X20000422.

- Pfattheicher, S., L. Nockur, R. Bohm, C. Sassenrath, and M. B. Petersen. 2020. “The Emotional Path to Action: Empathy Promotes Physical Distancing and Wearing of Face Masks during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Psychological Science 31 (11): 1363–1373. doi:10.1177/0956797620964422.

- Prichard, E. C., and S. D. Christman. 2020. “Authoritarianism, Conspiracy Beliefs, Gender and COVID-19: Links between Individual Differences and Concern about COVID-19, Mask Wearing Behaviors, and the Tendency to Blame China for the Virus.” Frontiers in Psychology 11: 1–7. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.597671.

- Rogers, Ronald W. 1975. “A Protection Motivation Theory of Fear Appeals and Attitude Change.” The Journal of Psychology 91 (1): 93–114. doi:10.1080/00223980.1975.9915803.

- Rogers, Ronald W., and Steven Prentice-Dunn. 1997. “Protection Motivation Theory.” In Handbook of health behavior research 1: Personal and social determinants, edited by D. S. Gochman, 113–132. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

- Scheid, J. L., S. P. Lupien, G. S. Ford, and S. L. West. 2020. “Commentary: Physiological and Psychological Impact of Face Mask Usage during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (18): 6655. doi:10.3390/ijerph17186655.

- Scholz, Urte, and Alexandra M. Freund. 2021. “Determinants of Protective Behaviours during a Nationwide Lockdown in the Wake of the COVID-19 Pandemic.” British Journal of Health Psychology 26 (3): 935–957. doi:10.1111/bjhp.12513.

- Setti, L., F. Passarini, G. De Gennaro, P. Barbieri, M. G. Perrone, M. Borelli, J. Palmisani, A. Di Gilio, P. Piscitelli, and A. Miani. 2020. “Airborne Transmission Route of COVID-19: Why 2 Meters/6 Feet of Inter-Personal Distance Could Not Be Enough.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17 (8): 1–6. doi:10.3390/ijerph17082932.

- Sibley, C. G., L. M. Greaves, N. Satherley, M. S. Wilson, N. C. Overall, C. H. J. Lee, P. Milojev, et al. 2020. “Effects of the COVID-19 Pandemic and Nationwide Lockdown on Trust, Attitudes toward Government, and Well-Being.” The American Psychologist 75 (5): 618–630. doi:10.1037/amp0000662.

- Siegrist, Michael, Luchsinger Luchsinger, and Angela Bearth. 2021. “The Impact of Trust and Risk Perception on the Acceptance of Measures Fighting against Covid-19.” Risk Analysis 41 (5): 787–800. early view. doi:10.1111/risa.13675.

- Svenson, O., S. Appelbom, M. Mayorga, and T. L. Ojmyr. 2020. “Without a Mask: Judgments of Corona Virus Exposure as a Function of Inter Personal Distance.” Judgment and Decision Making 15 (6): 881–888.

- Tang, Fang, Jing Liang, Hai Zhang, Mohammedhamid Mohammedosman Kelifa, Qiqiang He, and Peigang Wang. 2021. “COVID-19 Related Depression and Anxiety among Quarantined Respondents.” Psychology & Health 36 (2): 164–115. doi:10.1080/08870446.2020.1782410.

- Thacker, Paul D. 2020. “The US Politicisation of the Pandemic: Raul Grijalva on Masks, BAME, and Covid-19.” BMJ (Clinical Research ed.) 370: m3430 doi:10.1136/bmj.m3430.

- van Bavel, Jay J., Katherine Baicker, Paulo S. Boggio, Valerio Capraro, Aleksandra Cichocka, Mina Cikara, Molly J. Crockett, et al. 2020. “Using Social and Behavioural Science to Support COVID-19 Pandemic response.” Nature Human Behaviour 4 (5): 460–471. doi:10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z.

- Van Cauteren, D., S. Vaux, H. de Valk, Y. Le Strat, V. Vaillant, and D. Levy-Bruhl. 2012. “Burden of Influenza, Healthcare Seeking Behaviour and Hygiene Measures during the A (H1N1)2009 Pandemic in France: A Population Based Study.” Bmc Public Health 12 (1): 947. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-947.

- van der Linden, C., and J. Savoie. 2020. “Does Collective Interest or Self-Interest Motivate Mask Usage as a Preventive Measure against COVID-19?” Canadian Journal of Political Science 53 (2): 391–397. doi:10.1017/S0008423920000475.

- Wang, Cuiyan, Agata Chudzicka-Czupała, Damian Grabowski, Riyu Pan, Katarzyna Adamus, Xiaoyang Wan, Mateusz Hetnał, et al. 2020. “The Association between Physical and Mental Health and Face Mask Use during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Comparison of Two Countries with Different Views and Practices.” Frontiers in Psychiatry 11 (901): 1–13. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.569981.

- World Health Organization. 2021. "Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Advice for the Public: When and How to Use Masks." Accessed 03 February 2021. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public/when-and-how-to-use-masks.

- Zhang, Chun-Qing, Ru Zhang, Ralf Schwarzer, and Martin S. Hagger. 2019. “A Meta-Analysis of the Health Action Process Approach.” Health Psychology : Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association 38 (7): 623–637. doi:10.1037/hea0000728.