Abstract

Risk studies have shown that many people rather than following rational means of managing risk refer to non-rational (hope, faith) and in-between rationales (trust, intuition), which are not irrational but reasonable and based on subjective experiences, which are difficult to overcome by the communication of mere expert knowledge. We suggest that the problem of analyzing subjective risk management can be itemized as a result of the tension between subjective and objectified forms of certitudes. To clarify this distinction, the article turns to the New Phenomenology of Hermann Schmitz for outlining the different epistemological foundations of rational, non-rational and in-between rationales. We then develop a model of three different forms of knowledge that are involved in subjective risk management and elaborate the basic neo-phenomenological distinction of subjective and objective facts by differentiating the latter ones into rational and non-rational ones. We conclude with considering consequences of these epistemological challenges for risk communication.

1. Introduction

Interdisciplinary risk studies aim to improve social management and individual responses to risk. Issues such as pregnant women smoking or drinking, people not protecting their houses despite of repeating flooding, migrants engaging with people smugglers in high-risk journeys or people rejecting vaccination during the coronavirus crisis are all issues, which result in preventable loss, harm, or death. What is characteristic for such examples is that we always find a relatively wide and sometimes insuperable gap between the subjective and the objectified evaluation of risk situations. When explaining such behavior, risk studies has referred to the limits of the human brain for rational decision-making, and social factors influencing the experiences of risk and uncertainty such as one’s values and social positioning (Slovic, Citation2000b). The assumption of the superiority of expert knowledge over lay-people’s emotional perceptions has been challenged by science and technology studies highlighting the reasonable rationales of lay people (Wynne, Citation1996a, Citation1996b) and research on practical reasoning (Horlick-Jones, Citation2005a, Citation2005b) and individual engagement with risk (Zinn, Citation2008, Citation2016) which have highlighted a variety of reasonable ways to engage with risk and uncertainty such as trust, intuition, hope and faith. These observations are supported by neurological research that has shown that subjectively sensed emotional and objectifying rational spheres of the brain always work together when processing information (Damasio, Citation1996). However, overcoming Descartes’ view of the division between body and mind, comes with fundamental epistemological questions about people’s knowledge and engagement with risk. To explore the epistemological differences of the ways how ‘body and mind’ work together when people engage with risk and uncertainty we turn to the ideal-typical distinction between ‘rational’, ‘non-rational’ (e.g. hope, faith) and ‘in-between’ (e.g. trust, intuition) rationales (Zinn, Citation2008, Citation2016) and draw on insights from New Phenomenology (Schmitz, Citation2019) to argue for the fundamental rooting of knowledge and facts in subjectively sensibleFootnote1 certitudes. This has also ramifications for risk communication. We conclude that the shift of risk communication to deliberative, participative and procedural legitimacy to manage risk reasonably (Renn, Citation2008) is most successful when taking the subjective, embodied, and experience-based reality of risk into account.

In the following section we summarize central insights from risk studies and the different risk rationales introduced by Zinn (Citation2008) to suggest that New Phenomenology could help to systematize epistemological variations of these kinds of knowledges. We then move on to section three with introducing the concept of a two-dimensional subjectivity, elaborated by New Phenomenology, to prepare the analytical ground for the epistemologically important distinction between ‘subjective facts’ and ‘objective facts’ (section four). The fifth step of argumentation consists in two parts: firstly, we elaborate the model of subjective and objective facts by differentiating the latter ones into two ways of reflecting the respective life circumstances, namely empirical objectivations (rationality) and metaphysical objectivations (hope and faith). Secondly, we apply this distinction to the results of risk research and combine it with the model of risk rationales. Finally, we finish in section six with discussing what acting reasonably means in situations of uncertainty and the implications for risk communication.

2. Risk studies and new phenomenology

Typically, subjective risk perception and the objective knowledge about these risks often differ. For example, many people are concerned about relatively low risks such as being killed by an airplane disaster or nuclear power failure while underestimating comparatively high risks of activities such as smoking, drinking, cycling, riding a motor bike, lack of exercising, or unhealthy nutrition (Slovic, Citation2000b). More than 50 years of interdisciplinary risk research has proven the importance of best evidence and modelling for managing risky uncertainties while a growing body of research showed that subjective and social factors are crucial to understand how people perceive and make decisions about risk. Consequently, risk analysis focusses on the provision of best available evidence. The efforts to communicate risk knowledge in a way that best decisions are fostered has shown that differences in values and interests are central to public risk conflicts and different perceptions and responses to risk (Renn, Citation2008). Approaches to risk communication and risk governance therefore focused on deliberative approaches and public engagement emphasizing the need for legitimacy in risky decision making (Rosa et al., Citation2014). While there is still a knowledge component involved, these approaches also showed that social factors such as the building of trust (Fischhoff, Citation1995; Renn & Levine, Citation1991) is at least as important to successful risk management as is communicating knowledge in an accessible way (Gigerenzer, Citation2007). Furthermore, cognitive psychologists and behavioral economists have argued that people refer to ‘short cuts’, which relieve them from the burden of rationally exploring evidence in an increasingly complex life (Tversky & Kahneman, Citation1974) and even experts develop an intuitive sense for risk through a cumulation of experiences (Klein, Citation1998) often referred to as ‘gut feelings’. Additionally, the psychometric paradigm showed that people’s risk perception is dominated by mainly two factors, the familiarity of a risk or the unknown risk factor and the expected awfulness of a risk or the dread factor with affect becoming increasingly acknowledged in their role of influencing responses to risk (Slovic, Citation2010). At the same time, they brought back the question of how people acquire the knowledge for their decisions about risk. This became even more an issue since research showed that not only knowledge about risks and knowledge about the trustworthiness of others but anti-enlightenment approaches such as hope or faith play a role when people engage with unknown, uncertain, or highly complex but risky futures.

In order to take the sphere of subjective experience seriously and to systematize these different approaches to the world when engaging with risk, Zinn developed a three-dimensional scheme of rationales people utilize. He started with the modern orthodoxy of rational (evidence based) and non-rational (hope, faith) approaches and proposed a third category of in-between rationales (Zinn, Citation2008, Citation2016). Even though the latter ones, such as trust and intuition, are not rational in the strong sense, they can be quite reasonable in some circumstances. Due to the fact that situations of uncertainty are inherently characterized by the lack of relevant information, the ideal of fully rationalizing the respective setting in order to control the outcome falls theoretically and empirically short (Tversky & Kahneman, Citation1974, Citation1987). Local, situational, and intuitive knowledge arising from subjective lifeworld is therefore often more efficient as well as trusting others considered knowing better. Furthermore, the non-rational, which is hardly considered in risk analysis but social sciences such as hope and faith are valuable in face of risk by providing a positive attitude towards the future, which may result in better outcomes or allow to engage in high-risk activities without performance being negatively affected by fear and anxiety.

Zinn’s assumption that lay people as well as experts refer to a mix of different rationales is also supported by neurological and behavioral research. As Damasio has shown, all decisions require both, rationality and emotions engaging both parts of the brain (Damasio, Citation1996) while Kahneman has described two ways of thinking, the faster intuitive and the slower reflexive way of thinking (Kahneman, Citation2011). Thus, it is not merely a question of one’s values, interests, or experiences but there are deeper epistemological issues at work in the different rationales underpinning engagement with risk. Clarifying the epistemological issues can help to better understand and respond to the sometimes-counterintuitive rejection of empirically proven certitudes. In contrast to these dimensions of rational knowledge, our daily experience shows that there is this additional sphere of subjectively relevant certitudes, namely such ones like trust, intuition, emotion, love etc. that opposes to the subject in a pathic way. Such sensible certitudes are highly subjective and do not derive from reflection but happens to us evidently on the level of self-sensing.

Hence the analysis of dealing with risk and uncertainty faces an epistemological problem: these tacit forms of knowledge are ‘merely’ subjectively sensible, but at the same time they are highly evident to the self. It is precisely this categorially hardly tangible form of certainties that, in situations of risk, could either enable a person acting adequate, or could also get in opposition to rationally objectified facts. Considering this, the question comes into account how to itemize such sensible certitudes subject-theoretically? And, furthermore, to which degree this distinction can help to categorially sharpen the analysis of acting in situations of uncertainty?

In order to epistemologically elaborate the in-between and non-rational engagement with risk, the following sections develop a scheme of categorization that posits three relevant forms of knowledge. To this end, we shortly introduce some key arguments of the New Phenomenology before applying it to the findings of risk research. The mentioned approach, which was introduced by the German philosopher Hermann Schmitz (1928 – 2021), refers to the tradition of the philosophy of bodiliness or corporeality (in German ‘Leiblichkeit’). By refining the research of Edmund Husserl (Husserl, Citation1976), Maurice Merleau-Ponty (Merleau-Ponty, Citation1962) and especially Martin Heidegger (Heidegger, Citation1967), Schmitz profoundly investigated the subjective dimension of sensible certitudes as they obviously play a crucial role in risk management. Thus, he unfolds an innovative and empirically based way of understanding the experiences of our daily life. Dealing reasonably with situations of risk and uncertainty, as we will argue in our conclusions, depends on being in touch with the sensible sphere of self-givenness instead of merely trying to rationally dominate or overcome it.

3. The new phenomenology and its two-dimensional understanding of subjectivity

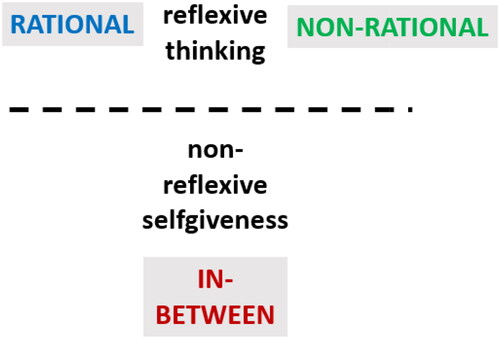

In order to develop an analytical model for risk research by using the neo-phenomenological epistemology, it is worth to initially distinguish two basic classes of knowledge, namely the reflexive and the non-reflexive. In this first rather rough differentiationFootnote2 the reflexive knowledge denotes all forms of creating objectivations by symbol-mediated thinking, whereas the category of non-reflexive represents that what undoubtedly occurs to the subject on the level of involuntary sensations. Though New Phenomenology does not refer to phenomenological sociology, it nevertheless seems to be helpful to shortly turn towards the early writings of Alfred Schütz to clarify the proposed distinction.

Before finally turning to the (classical) phenomenology of Edmund Husserl, Schütz (Citation2013) started an attempt to work out his ideas in the early 1920s by using the time-theoretical investigations of Henri Bergson (Schütz, Citation1981). The key issue for Schütz at the time was the analytical problem that, in order to generate meaning structure by symbolic thinking, there logically needs to be a prior level of subjective experience. Otherwise, the process of unfolding meaning structure by symbolic representations would simply not have any content to reflect on. Schütz (Citation2013, p. 31) hence speaks of the ‘basic difference between experiences as such and the reflection about experiences - a difference important for many reasons’ which, following Schütz, was firstly acknowledged by Henri Bergson. However, as Schütz in accordance with Bergson highlights, the non-reflexive sphere of experience, understood as the pure duration of the I, can hardly be grasped by symbolic representations. Schütz stresses:

Our experiencing is almost ever coupled with reflection about the experience. We control ourselves by our thinking; often we are unable to see the image on account of the concepts. Our consciousness of the stream of duration holds on only timidly to the unambiguous ‘now’ and ‘thus’, using them as rigid boundaries between which we squeeze our experiences-turned-into-concepts (Schütz, 2013, pp. 31).

With every positing of a symbol, the I steps more [and more] Footnote3 out of pure duration and into an objective world. To symbolize an experience means to rob it of its [character as a highly personal experience and its] belonging to a specific Now and Thus and, instead, to endow it with general validity. (Schütz, 2013, pp. 70)

Though Schmitz, as mentioned, does not refer to the work of Alfred Schütz, the basic tension between reflexive and non-reflexive knowledge plays a key role in New Phenomenology. In particular, by criticizing classical approaches of self-consciousness, Schmitz develops a two-dimensional understanding of subjectivity. The key argument is that there are phenomenologically two forms of self-consciousness, or in other words ‘two sources of my access to acquaintance with myself’ (Schmitz, Citation2018) (pp. 72) [translated by one of the authors]. While the definite description of other phenomena, as Schmitz (Schmitz et al., Citation2011)(pp. 248) argues, does indeed work by means of ascription this does not work related to self-consciousness. That which is to be identified in the latter case, Schmitz argues similar to Schütz, must already be known to avoid an infinite regress. Schmitz highlights (Schmitz, Citation2010):

Why should I be just Hermann Schmitz and not, for example, Alexander the Great? All objective facts, which one can state about Hermann Schmitz, carry no trace of the information that this man of all men is what I am. I know it only through my affective involvement, in that something comes close to me, which I can pursue with prudence, with the result that I find a range of circumstances in which I am entangled or, as Heidegger would say, in which I am thrown. This applies to every conscious entity, even to the one who, like an animal or an infant, cannot even say ‘I’ or even speak. (Schmitz Citation2010, pp. 22) [translated by one of the authors]

Eventually, the fruitful contribution of New Phenomenology in the context of this article is the empirically based itemization of the non-reflexive knowledge. While this sphere of subjective experience in Schütz’ early writings remained a logically necessary but epistemologically problematic dimension, with New Phenomenology, it becomes conceptually itemizable and empirically verifiable.

To summarize this argument, self-consciousness without self-ascription occurs to us by bodily sensations like pain, fear, hunger, tiredness, shame or by being seized by feelings (Schmitz, Citation1996)(pp. 23). The fact that this non-ascriptive self-consciousness has been neglected so long in philosophy and in other disciplines is certainly connected with its epistemologically problematic status. So bodily sensations are in the moment of affectedness as evident as possible. On the other part it is at the same time as subjective as something could be which makes it epistemologically suspicious. However, the whole sphere of pathic self-givenness is, neo-phenomenologically taken, the most evident and ultimately the most relevant level of our lived experience.

In this context it should be mentioned that the neo-phenomenological concept of non-reflexive self-givenness by bodily sensations is not merely a logical deduction by a philosopher sitting in his armchair, doing philosophy of consciousness. In contrary, the insights of Schmitz have already been fruitfully applicated in various fields of research, e.g. in medicine (Burger, Citation2008; Danzer, Citation1993; Langewitz, Citation2008), in clinical psychology (Moldzio, Citation2006; Wendt, 2015) or developmental psychology (Fuchs, Citation2000, Citation2008).

Finally, the neo-phenomenological model of a two-dimensional subjectivity exhibits an empirically founded understanding of subjective experience that can help to conceptualize non-reflexive but undoubtedly sensible forms of certitudes like intuition or trust. Hence, we have an analytical tool to investigate the relevant levels of knowledge as they play a crucial role in the process of decision making in situations of risk and uncertainty. Beside the different forms of objectified knowledge (we go deeper into that in chapter 5), there are sensible certitudes which occurs to the self on the level of bodily sensations. Since such sensible certitudes are as evident as they are subjective, Schmitz terms it a dimension of ‘subjective facts’.

4. The neo-phenomenological distinction of subjective and objective facts

According to these insights of New Phenomenology and its relevance for dealing with uncertainty, the whole sphere of non-reflexive certitudes moves to the center of the considerations. As the phenomenological and psychological research evidently shows, we are primarily sensing entities that, only on the base of such sensible self-consciousness, are able to unfold the sphere of reflexive thinking. The latter one constitutes the mean of objectivation which can be either empirically founded (rationality), or rather metaphysical in the sense of an imaginative extension of one’s horizon (faith and hope). Both of these two levels of knowledge, reflexive (rationality, hope and faith) and non-reflexive (intuition and trust) forms of certitudes (see ), as the risk-sociological research shows, are highly relevant for decision making. Following the epistemology of New Phenomenology, these two levels of certainties can be considered as subjective and objective, or more specifically, objectified facts.Footnote4 The rather contradictorily seeming term of ‘subjective facts’ is closely linked to the theory of self-consciousness presented above and is defined by Schmitz as following:

Such self-consciousness without self-ascription is made possible by the subjective facts peculiar to affective involvement. In their plain factuality, they already contain reference to oneself, respectively to the experiencer. As a result, they can be predicated by, at most, one person under their own name. This stands in contrast to objective or neutral facts, which can be predicated by anyone, granted they know enough and are sufficiently articulate. The facts that are subjective for someone are richer in containing this subjectivity than the pale and neutral ones that result from the former by grinding down subjectivity. (Schmitz et al., Citation2011)(p. 248f.)

Schmitz uses the scientifically provocative term of ‘subjective facts’ in order to emphasize, contrary to positivist transfigurations, that a fact, epistemologically, is first of all always a fact for someone. In this context it is crucial to understand that the aim of Schmitz’ distinction of subjective and objective facts is definitely not to neglect or overplay the crucial difference of subjectivity and intersubjectivity. On the contrary, the way from subjective experience to intersubjective traceability, and hence to objectified knowledge can be adequately clarified by this conceptional improvement of New Phenomenology. Hence, this approach shows that our lived experience, as Alfred Schütz already assumed, is characterized by a kind of ontological gap that could not be epistemologically suspended. Though positivist science pretends to neglect the sphere of subjectivity, it remains the epistemological ground even for science as e.g. Bruno Latour illustratively reconstructed (Latour, Citation1993). In order to get to the level of objectifications, one could say that the initially subjective facts must be deprived of their subjectivity by the means of symbolic representation; they have to reduce as much as possible the inherent subjective bias of any facticity.

However, this practice of objectification is an ambivalent capability of human subjects. As the philosopher and psychiatrist Thomas Fuchs argues in this context, depreciating or even completely ignoring the non-reflexive but sensible sphere of subjective certitudes provokes a highly problematic and potentially pathological self- and world-relation. Fuchs highlights:

Without affective contact the world gets ‘on the other side’ and freezes in empty existence, in dead facticity. This emptying falls back on the subject and contradicts Descartes’ cogito: A human being who only thinks, who is not bodily-feelingly connected with the world, no longer ‘lives’, namely in the sense of the living existence that underlies all cognitions. The complete subject-object-separation, the stripping of all own from the alien, would therefore not produce the certainty of pure selfhood, but a nightmare of alienation. (Fuchs, Citation2008, S. 272) [translated by one of the authors]

Finally, to come back to the topic of this article, this ontological gap is the reason why situations of risk and uncertainty necessarily requires strategies of in-between. It is the eventful openness of the respective situation itself that epistemologically commands us into a dialogue between the sensed and the objectified forms of certitudes. This of course becomes as problematic as possible in questions of existential threats. In situations of life-threatening circumstances, the objective fact that e.g. half of the population survives a medical treatment or dies of lung cancer due to the consumption of tobacco is not quite helpful. Due to the problem that even the most sophisticated statistic does not response to the ultimately relevant question ‘what does this say about my very concrete case?’, the self continuously has to step into a dialogue between sensible and objectified facts, between reflexive and non-reflexive certainties.

To summarize this, the three-dimensional model of non-rational, in-between, and rational strategies of dealing with risk and uncertainty could be reformulated: While any subjective self is sensibly exposed to its own existence, as humans we are additionally able to emancipate from this situational structured entanglement by reflection. The result of this reflection can take the form of rational thinking, as well as constructing hope, beliefs and so on. We are thus analytically confronted with three forms of certainty, one of which belongs to the sensed (trust and intuition) and two to the reflexive (rationality on the one hand, and non-rational hope and faith on the other). In the next step we will sharpen this latter distinction and apply it to the empirical data of risk research.

5. Characterize different risk rationales by three forms of certainty

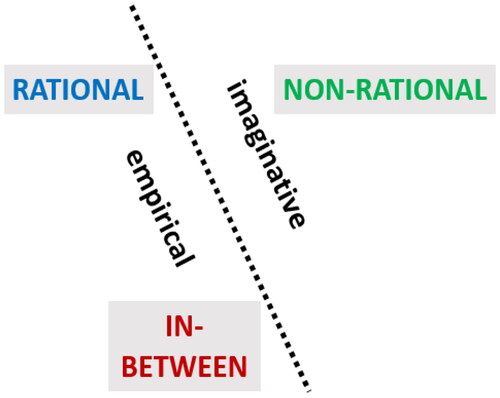

In situations of risk and uncertainty, as the previous sections have suggested, we are analytically confronted with three dimensions of relevant knowledge. Beyond the highly subjective experience of bodily sensations (subjective facts), we find two additional forms of objectified certainties: rational and non-rational knowledge. We call the latter ones also ‘objectified knowledge’ because they are result of the human capability of reflexive thinking as well. Due to this categorial overlap, we now propose a scheme to categorially distinguish these three forms (sensed, rational and non-rational) and, subsequently, apply it to empirical examples. The two crucial dimensions for our distinction are the level of being anchored in subjective lifeworld and the degree of empirical foundation of the respective knowledge.

We start with the aspect of being anchored in subjective lifeworld. It is clear that, for example, the objective insight that half of the participants of a medical treatment survives the illness (rational knowledge) and the subjective faith that I as an affected person will belong to this half (non-rational knowledge) are, phenomenologically, crucially different forms of certainties. Though both are ultimately result of our capability of reflexive thinking and hence belong to the category ‘objectified forms of knowledge’, they obviously must be analytically distinguished. The crucial difference between such statistical data and other forms of reflexive thinking like faith and hope comprises in the level of being anchored in the respective lifeworld. That means that a fully rationalized fact like e.g. the survival probability of a medical treatment, phenomenologically, appears to the self as something that ‘comes across’ in the respective situation. Such highly abstract forms of certitudes are primarily alien and detached from the subjective lifeworld and hence need to be re-entangled to the self. A person that is confronted in a situation of risk with statistical evidence, at the first step, faces a cold factuality which needs to be re-entangled to him or her sphere of meaningfulness.

Contrary to this, the other forms of objectified knowledge, namely the metaphysical ones like hope or faith, arise from the subjective lifeworld. Though they are objectivations as well, generated by reflexive thinking, they are in the first place subjective. They are what we call forms of imaginative extensions of one’s horizon towards a desired future. Hope and faith help the self to cope with a subjectively experienced situation of risk and uncertainty. However, these forms of reflexive generated knowledge, obviously, can unfold a collective sense as well as other objectivations do. Insofar as they achieve a power of conviction, jumping from one subjective lifeworld to another, they proliferate their capability of collective sense-making.

In order to distinguish the two forms of objectified knowledge, as mentioned, there is a second aspect that is analytically helpful. Rational facts on the one hand and hope and faith on the other are characterized by a different degree of empirical foundation. To clarify this, one could once again refer to the example of medical treatment and the probability of subjective survival: While the statistical knowledge about the effectiveness of a treatment is based on empirical data from the past, the hope that I, as a concrete and affected person will survive, is a kind of imaginative extension of one’s horizon. Thus, both forms, rational and non-rational knowledge, are indeed result of the human capability of reflexive thinking. However, they have to be distinguished by the level of experience saturation. Rational facts result from former observations and hence are empirically founded. In contrary to this, non-rational results of reflexive thinking like hope and faith are less based in former experience but are focused on a desired and imagined future ().

In summary, there are two categories by which the objectified forms of knowledge can be distinguished. Due to its level of abstraction, in the first place, rational knowledge often is experienced as something that is detached from the subjective lifeworld. These facts arise to the subject firstly as a potentially meaningless factuality that has to be re-entangled with the subjective living conditions of a concrete person. The other forms of abstract thinking, namely hope and faith, in contrast, are subjective from their origin. They arise from the lifeworld of the affected person but are less empirically grounded. They are rather a practice of constructing desired futures .

The third form of certainties that are relevant for managing risk situations are the sensible ones, like trust and intuition. We call them subjective facts because they are experienced involuntarily on the level of bodily sensations and can be hardly objectified. However, they share some categorial similarities with both of the former mentioned categories of objectified knowledge: On the one hand intuition and trust arise to the self as something that is sensible and non-reflexive, and consequently, is of course part of the subjective lifeworld as faith and hope are. On the other hand, intuition and trust are founded in former experience and thus are empirically grounded as rational knowledge. To summarize this, one could say that in particular rational and in-between strategies of managing risk are empirically grounded. The difference of such forms of acting is merely whether the relevant knowledge appears to the self on the level of reflection (rational) or on the level of bodily sensations (in between). Although non-rational knowledge, finally, is undoubtedly result of objectifying the respective situation as well as rational forms, it nevertheless is characterized by a low degree of empirical saturation ().

5.1. Intuition, trust, hope and faith

The conceptual considerations provide the basis for exploring the differences between the non-rational and in-between rationales to be outlined in the following by empirical examples. Still, it has to be kept in mind that all these ideal type constructs usually mix in different ways and degrees using the specific advantages of each for managing risk. For example, when people from Senegal engaged in high risk boat journeys to the Canary Islands, they did not only refer to faith and hope but some also made sure that an experienced fishermen was steering the boat they entered (Hernández-Carretero & Carling, Citation2012). Rational knowledge might be too complex or difficult to understand that people replace it by trust in experts or significant others. Own expertise can only provide some degree of certainty and there is always a little bit of hope involved that things turn out as calculated. Concepts themselves such as blind trust might increasingly be replaced by reflexive evaluation of who to trust as Anthony Giddens suggested. Still, each ideal type comes with specific characteristics we discuss in the following.

5.2. In-between: intuition and trust

There is a large body of research on intuitive engagement with risk. As Gary Klein has famously shown by many examples, people develop tacit knowledge on the basis of experience accumulated over time to manage risky situations (Klein, Citation1998). Examples of professionals show how these learn to recognize intuitively typical situational patterns that inform their decision making. In one example he showed that nurses at a neonatal intensive care unit of a large hospital (1998, pp. 39–40) developed experience-based intuitive skills when caring for newly born infants who were premature or otherwise at risk. One of the difficult decisions these nurses had to make was to judge when a baby was developing a septic condition which becomes almost immediately life threatening. These nurses could intuitively sense the on-set of a sepsis and that they had to start the antibiotics (Crandall & Getchell-Reiter, Citation1993). Even though the nurses found it difficult to identify the signs and symptoms that enabled them to identify the early on-set of sepsis, in most cases their initial judgement was subsequently confirmed by tests. In other words, the intuitive knowledge, as we stressed above, is hardly objectifiable by reflexive thinking. In another example, a lieutenant with his firefighting crew came to a burning house and entered the building. They sprayed water on the fire in the kitchen area of the back of the building, but the fire just roared back to them. The lieutenant thought that this is odd, the water should have had more of an impact and started to feel that something wasn’t right. He hadn’t a clue what that was but when he and his crew left the building, the floor they had just been standing on collapsed. The lieutenant had no idea that the source of the fire was in the basement since such houses usually don’t have a basement (Klein Citation1998: 32). These examples are characterized by people developing a sense for a situation they have experienced repeatedly. They have an immediate embodied sensation about the situation, a subjective certitude that manifests before they can reflect about it. Even after the decision they find it difficult to put the finger on the concrete aspects that informed their decision. Still, their decisions were deeply rooted in their experience.

For most risks, people are lacking this kind of direct personal knowledge but have to rely on others, such as experts (doctors, scientists, technicians) and the media reporting and explaining expert knowledge. Their subjective certainty refers therefore to their relationship to others. As research has shown, perceived trustworthiness bases on at least two dimensions. First, trust builds over time and is experience based, judging one’s competence reflexively. Second, people can also experience more immediate trust in others when perceiving similar values and interests and other dimensions characterising social relationships, thereby referring to more general social experiences (Barbalet, Citation2009; Lewis & Weigert, Citation1985). Most of the studies struggled to characterise trust well with the opposition of knowledge (rational) and faith (non-rational) focussing on reflexive objectifications (Möllering, Citation2006). In contrast, we suggest that trust is rooted phenomenologically in subjectively experienced certainties rooted in tacit knowledge and subjective facts. The knowledge gap to be bridged by a ‘leap of faith’ characterising trust, as Guido Möllering suggested, overlooks the subjective experience of trustworthiness in between.

In summary, trust and intuition sharply differ by the connection to knowledge. Intuition as an embodied experience refers to an immediate embodied experience of a risky situation while trust refers to the risky reality mediated through the experience with others. The subjective certitudes refer to the sensed and experienced trustworthiness of others.

5.3. Non-rational but reasonable: hope and faith

Hope helps people to cope with the risky uncertainties of the future. Even when one rationally calculates the odds there is regularly a place for hope that nothing has been overlooked and no unexpected events happen. Hope comes with a positive attitude, which might have positive effects itself, such as staying calm in high-risk situations. As well as rational thinking, it is a form of emancipating from the concrete situation by reflection. However, as we showed above, hope and faith are hardly empirically grounded but are oriented towards a desired future. Also, the positive effects of hope for healing have been recognized (Snyder et al., Citation1991; Yıldırım & Arslan, Citation2020). Therefore, one might argue that hope can similarly be experience-based than the other concepts. However, the advantage of hope in contrast to mainly empirically based concepts such as intuition and trust is the imaginative extension of one’s horizon that is based not on external conditions but primarily on subjective certitudes. The proverb, ‘hope dies last’, expresses the empirically detached reality of hope that can be maintained even against all odds. Hope is therefore particularly powerful for engaging with high-risk activities to overcome undesired realities such as illegal migration to escape poverty or political prosecution or even to initiate revolution (Bloch, Citation1986; Hayenhjelm, Citation2006; Hernández-Carretero & Carling, Citation2012). Bloch emphasizes the importance of an imagined positive future state, as a basis of hoping, to questioning and overcoming an undesired present.

Similarly to hope, in risk studies faith has often been interpreted in contrast to rationality. The focus on faith in managing risks would prevent efficient risk management. Instead, the felt certitude that one’s future is in the hand of God or supernatural powers, would support passivity and lack of precaution (Renn, Citation2008). For example, the attribution of road accidents to superstitious sources is often seen as a reason for lacking engagement in road-safety measures (Kayani et al., Citation2017). Thus, faith is detached from empirical reality but is strongly connected with the subjective lifeworld. Its intensity does less rely on empirical facts but one’s mental state. For example, the religious conversion or satori is less based on empirical realities but subjective experience. Faith in God is a highly personal and subjective experience and people enjoy the positive feelings and direction coming with their faith even when empirically or logically unjustified. The subjectively experienced certitudes of faith do, however, not mean that there is no active engagement with the world possible. Instead, Lois Bastide (Bastide, Citation2015) argued in a study on Indonesian migrant workers that these are well aware of the risks of abuse or even death but the ‘dangerous journey, was [interpreted as] a powerful way of proving the depth of their religious commitment … quite paradoxically, taking risks was thus perceived as a means of avoiding risks; proving one’s fate in the Almighty was understood as a way of seeking God’s shelter’ (Bastide Citation2015: 235-6). As Bastide explains (2015: 239): ‘It is true that the individuals perceive themselves as being dominated by destiny. However, they experience their power of action elsewhere: through their capacity of attention and their aptitude to decipher and decrypt the signs disseminated on their path, but also in their ability to take advantage of the elusive openings of a destiny according to these clues.’ The subjectively experienced certitudes remain and adapt to an ever-changing empirical reality providing a feeling of security in face of an in principle uncertain future. It is the personal sensation of a strong faith and the careful reading of the cues given in one’s life rather than personal skills or control of a risky situation, which shapes one’s engagement and coping with risk.

In summary, hope is less institutionalized than faith, but both are (contrary to highly abstract forms of rational knowledge) strongly anchored in people’s subjective lifeworld. Even though we stressed that these non-rational forms of objectifying the current life conditions are less empirically grounded, this could be indeed the case when in the long run one might have made the experience that it is better to hope or turn to one’s faith to manage the risks and uncertainties of everyday life. It is important to keep in mind that hope as well as faith can be encouraged by social institutions but are typically not based on evidence (Brown, Citation2007; Brown et al., Citation2015; Cook, Citation2017).

6. Conclusions: from the subjective lifeworld to reasonable risk management

As both the former neo-phenomenologically founded analysis as well as the shift in risk studies indicate, it is worthwhile to engage with the variety of subjectively relevant forms of knowledge. Instead of deprecating all that is not result of rational thinking, our approach allowed us to itemize the subjectively experienced situations of risk and uncertainty. Hence, it becomes possible to categorize the relevant forms of knowledge by an epistemologically coherent and empirically grounded theory. Applied to typical examples of the sphere of risk, we argued that sensible certitudes like trust and intuition have, as typical for non-reflexive knowledge, a deeper rooting in one’s experience of the life world. In contrast, scientific expertise as provided by experts requires a re-attachment to become subjectively meaningful, for example, mediated through trust in others. In addition to the rational forms of itemizing current life circumstances, there are other ways of objectifying subjective reality, namely the metaphysical objectivations like hope and faith. As we argued, the latter ones are of course less empirically grounded than rational thinking, they are non-rational, but however, could be quite helpful and also reasonable in situations of high risk and uncertainty.

The subjective certitudes challenge risk communication. Intuitive evaluation of trustworthiness might be misleading, when the trusted others relate well to one’s lifeworld but not to the more empirically based interpretation of risk. It then requires people to challenge deeper social certainties of their lived experiences which go beyond specific risks but are based on intuitive knowledge. Evidence-based risk communication becomes even more difficult when addressing empirically detached subjective certitudes, which people adhere to because of their advantages in managing risk and uncertainty cognitively and emotionally. Having an important function in coping with everyday life, it fundamentally challenges risk communication, which bases on the communication of scientific expertise. As a result, risk communication shifted towards a stronger focus on managing the relationship between involved parties and should thereby be understood as a social process that takes place in the public sphere rather than merely a performance of communicators. Experts in risk communication such as Ortwin Renn have emphasized the need for participative and deliberative approaches with high procedural legitimacy (Renn, Citation2008), which, when well applied, increases the likelihood of high compliance with and support for risky decisions. Others have also emphasized the importance of reducing practical hurdles, for example, for coronavirus vaccination and nudging people into compliance with desired behavior (Evans & French, Citation2021; French, Citation2017). Still, in practice, many insights from risk communication research are not well considered in cases of crisis such as during the management of Covid-19 (Wardman, Citation2020). Since public responses to risk are not only informed by expert knowledge, different values and competing interests but subjective certainties, there are epistemological hurdles which are difficult to overcome. It is extremely unlikely that people give up on deeply rooted certainties connected to the embodied experienced truths of one’s life world for the sake of successful risk management. Confrontational strategies and coercion, such as with compulsory vaccination, would even increase resistance if not accompanied by extensive efforts of risk communication. When social risk communication is done well, obligatory measures might not even be necessary (Vanderslott & Marks, Citation2021).

In summary, this article argues that it would be fruitful to empirically and theoretically acknowledge the variety of certitudes which are involved in subjective risk management. Only by empowering the subjects to step into a dialogue to him- or herself, namely in order to find a solution for the not rationalizable openness of the respective presence and its inherent uncertainty, can reason be practically realized by human subjects.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 „Sensible” means here and elsewhere „capable of being sensed”.

2 As initially mentioned, we will expand this analytical distinction in section 5 further into a three-dimensional model. In order to do so, we will differentiate the objectified knowledge, resulting from reflexive thinking, into rational and non-rational forms by using the categories of being anchored in subjective lifeworld and the level of empirical foundation.

3 Unfortunately, the English translation of this passage is incomplete. We added the missing parts in square brackets because they are crucial for our argument. Compare Schütz Citation1981, pp. 140.

4 In the coming section we will sharpen the distinction between the two forms of objectivations generated by reflection, namely rationality on the one hand, and hope and faith on the other. The two crucial differences are the degree of empirical foundation and the level of being anchored in the subjective lifeworld.

References

- Barbalet, J. 2009. “A Characterization of Trust, and Its Consequences.” Theory and Society 38 (4): 367–382. doi: 10.1007/s11186-009-9087-3

- Bastide, L. 2015. “Faith and Uncertainty: migrants’ Journeys between Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore.” Health, Risk & Society 17 (3–4): 226–245. doi:10.1080/13698575.2015.1071786.

- Bloch, E. 1986. The Principle of Hope. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Brown, N. 2007. “Shifting Tenses: Reconnecting Regimes of Truth and Hope.” Configurations 13 (3): 331–355. doi:10.1353/con.2007.0019.

- Brown, P., S. de Graaf, and M. Hillen. 2015. “The Inherent Tensions and Ambiguities of Hope: Towards a Post-Formal Analysis of Experiences of Advanced-Cancer Patients.” Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine 19 (2): 207–225. doi:10.1177/1363459314555241.

- Burger, W. 2008. “Wozu braucht man in der Medizin Philosophie? Die Bedeutung der Neuen Phänomenologie von Hermann Schmitz für die Medizin.” In Neue Phänomenologie zwischen Praxis und Theorie. Festschrift für Hermann Schmitz, edited by M. Großheim, 141–150. Freiburg, München: Karl Alber.

- Cook, J. 2017. Imagined Futures: Hope, Risk and Uncertainty. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-65325-9.

- Crandall, B., and K. Getchell-Reiter. 1993. “Critical Decision Method: A Technique for Eliciting Concrete Assessment Indicators from the Intuition of NICU Nurses.” Advances in Nursing Science 16 (1): 42–51. https://journals.lww.com/advancesinnursingscience/Fulltext/1993/09000/Critical_decision_method__A_technique_for.6.aspx. doi:10.1097/00012272-199309000-00006.

- Damasio, A. 1996. Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason and the Human Brain. London: Macmillan Press Ltd.

- Danzer, G. 1993. “Philosophische Fragen im Bereich psychosomatischer Medizin.” In Rehabilitierung des Subjektiven. Festschrift für Hermann Schmitz, edited by M. e. a. Großheim, 209–223. Freiburg, München: Karl Alber.

- Evans, W. D., and J. French. 2021. “Demand Creation for COVID-19 Vaccination: Overcoming Vaccine Hesitancy through Social Marketing.” Vaccines 9 (4): 319. https://www.mdpi.com/2076-393X/9/4/319. doi:10.3390/vaccines9040319.

- Fischhoff, B. 1995. “Risk Perception and Communication Unplugged: Twenty Years of Process.” Risk Analysis: An Official Publication of the Society for Risk Analysis 15 (2): 137–145. doi:10.1111/j.1539-6924.1995.tb00308.x.

- French, J. (Ed.). 2017. Social Marketing and Public Health. Theory and Practice (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fuchs, T. 2000. Leib, Raum, Person. Entwurf einer phänomenologischen Anthropologie. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta.

- Fuchs, T. 2008. Leib und Lebenswelt. Neue philosophisch-psychiatrische Essays. Kusterdingen: Graue Edition.

- Gigerenzer, G. 2007. Gut Feelings. New York: Viking.

- Hayenhjelm, M. 2006. “Out of the Ashes: Hope and Vulnerability as Explanatory Factors in Individual Risk Taking.” Journal of Risk Research 9 (3): 189–204. doi:10.1080/13669870500419537.

- Heidegger, M. 1967. Sein und Zeit. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer.

- Hernández-Carretero, M., and J. Carling. 2012. “Beyond ‘Kamikaze Migrants’: Risk Taking in West African Boat Migration to Europe.” Human Organization 71 (4): 407–416. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44148674. doi:10.17730/humo.71.4.n52709742v2637t1.

- Horlick-Jones, T. 2005. “Informal Logics of Risk: contignency and Modes of Practical Reasoning.” Journal of Risk Research 8 (3): 253–272.

- Horlick-Jones, T. 2005b, 2005/09/01. “On ‘Risk Work’: Professional Discourse, Accountability, and Everyday Action.” Health, Risk & Society 7 (3): 293–307. doi:10.1080/13698570500229820.

- Husserl, E. 1976. Ideen zu einer reinen Phänomenologie und phänomenologischen Philosophie, Buch 1, Aus Husserliana Gesammelte Werke, Band 3. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

- Kahneman, D. 2011. Thinking, Fast and Slow. London: Allen Lane.

- Kayani, A., J. Fleiter, and M. King. 2017. “Superstitious Beliefs and Practices in Pakistan: Implications for Road Safety.” Journal of the Australasian College of Road Safety 28 (3): 22–29. https://search.informit.org/ doi: 10.3316/informit.325436234031184.

- Klein, G. A. 1998. Sources of Power: How People Make Decisions. Cambridge, Mass., London: MIT Press.

- Langewitz, W. 2008. “Der Ertrag der Neuen Phänomenologie für die Psychosomatische Medizin.” In Neue Phänomenologie zwischen Praxis und Theorie. Festschrift für Hermann Schmitz, edited by M. Großheim, 126–141. Freiburg, München: Karl Alber.

- Latour, B. 1993. We Have Never Been Modern. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

- Lewis, J. D., and A. Weigert. 1985. “Trust as a Social Reality.” Social Forces 63 (4): 967–985. doi:10.2307/2578601.

- Merleau-Ponty, M. 1962. Phenomenology of Perception. London: Routledge and Kegan.

- Möllering, G. 2006. Trust: Reason, Routine, Reflexivity. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Moldzio, A. 2006. Zur schizophrenen Entfremdung auf der Grundlage der Neuen Phänomenologie. In Symptom und Phänomen, edited by D. Schmoll & A. Kuhlmann, 185–203. Freiburg, München: Karl Alber.

- Renn, O. 2008. Risk Governance. Coping with Uncertainty in a Complex World. London, Sterling, VA: Earthscan.

- Renn, O., and D. Levine. 1991. Credibility and Trust in Risk Communication. In Communicating Risks to the Public, edited by R. E. Kasperson & P. J. M. Stallen, 175–217. Dordrecht, Boston, London: Kluwer.

- Rosa, E. A., O. Renn, and A. M. McCright. 2014. The Risk Society Revisited. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

- Schmitz, H. 1996. Husserl Und Heidegger. Bonn: Bouvier.

- Schmitz, H. 2010. “Bewusstseinixtheode.” https://ixtheo.de/Record/626504465

- Schmitz, H. 2018. Wozu Philosophieren? Freiburg, München: Karl Alber.

- Schmitz, H. 2019. New Phenomenology: A Brief Introduction. Milano, Udine: Mimesis International.

- Schmitz, H., R. O. Müllan, and J. Slaby. 2011. “Emotions outside the Box-the New Phenomenology of Feeling and Corporeality.” Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 10 (2): 241–259. doi:10.1007/s11097-011-9195-1.

- Schutz, A. 2013. Life Forms and Meaning Structure. London: Routledge.

- Schütz, A. 1981. Theorie Der Lebensform. Manuskripte Aus Der Bergson-Periode. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

- Slovic, P. 2000. The Perception of Risk. London, Sterling, VA: Earthscan.

- Slovic, P. 2010. The Feeling of Risk. New Perspectives on Risk Perception. London, Washington, DC: Earthscan.

- Snyder, C. R., L. M. Irving, and J. R. Anderson. 1991. “Hope and Health.” In Handbook of Social and Clinical Psychology: The Health Perspective, edited by C. R. Snyder & D. R. Forsyth, 285–305. Elmsford, NY: Pergamon Press.

- Tversky, A., and D. Kahneman. 1974. “Judgement under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases.” Science 185: 1127–1131.

- Tversky, A., and D. Kahneman. 1987. Rational Choice and the Framing of Decisions. In Rational Choice: The Contrast beween Economics and Psychology, edited by R. Hogarth & M. Reder, 67–84. University of Chicago Press.

- Vanderslott, S., and T. Marks. 2021. “Charting Mandatory Childhood Vaccination Policies Worldwide.” Vaccine 39 (30): 4054–4062. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.04.065.

- Wardman, J. K. 2020. “Recalibrating Pandemic Risk Leadership: Thirteen Crisis Ready Strategies for COVID-19.” Journal of Risk Research 23 (7-8): 1092–1120. doi:10.1080/13669877.2020.1842989.

- Wynne, B. 1996a. May the Sheep Safely Graze? A Reflexive View of the Expert-Lay Knowledge Divide. In Risk, environment and modernity: towards a new ecology, edited by S. Lash, B. Szerszynski, & B. Wynne, 44–83. Sage.

- Wynne, B. 1996b. Misunderstood misunderstandings: social identitites and public uptake of science. In Misunderstood Misunderstandings: Social Identities and Public Uptake of Science, edited by A. Irwin & B. Wynne, (pp. 19–46). Cambridge University Press.

- Yıldırım, M., and G. Arslan. 2020. “(2020). Exploring the Associations between Resilience, Dispositional Hope, Preventive Behaviours, Subjective Well-Being, and Psychological Health among Adults during Early Stage of COVID-19.” Current Psychology 41 (8): 5712–5722. doi:10.1007/s12144-020-01177-2.

- Zinn, J. O. 2008. “Heading into the Unknown – Everyday Strategies for Managing Risk and Uncertainty.” Health, Risk & Society 10 (5): 439–450. doi:10.1080/13698570802380891.

- Zinn, J. O. 2016. “In-Between’ and Other Reasonable Ways to Deal with Risk and Uncertainty: A Review Article.” Health, Risk & Society 18 (7–8): 348–366. doi:10.1080/13698575.2016.1269879.