Abstract

A high percentage of current news media covers topics relevant to the public such as wars, crime, and terrorist attacks, making threat perceptions and fears in public spaces (TPF-PS) more salient. Due to the unique challenges involved with current media landscapes, research examining how news consumption (NC) is related TPF-PS is still attracting scholarly interest. Therefore, we conducted a scoping review of N = 72 empirical studies since the advent of the smartphone era. The review detects cultivation theory as the main theoretical approach as well as a prevalence of quantitative methods and cross-sectional surveys. Furthermore, most empirical studies are carried out in North America and draw on non-probability sampling methods. Moreover, the review detects (region-based) research trends by breaking down N = 307 identified operationalizations into main classifications of TPF-PS and NC. Additionally, the review indicates a predominance of no associations between NC and TPF-PS. Implications for future research are discussed.

In current times, endless streams of graphic images and media reports about terrorist organizations and committed violent crimes are broadcasted around the world (Wessler et al. Citation2022). Arguably, this permanent awareness of the latest events, as well as past crime incidents or terrorist attacks, are making society’s fear of threats more salient. Threat perceptions and fears in public spaces (TPF-PS) (including, e.g. generalized fears of victimization and feelings of insecurity within the general public) are typically regarded as a robust indicator of people’s political mood with meaningful links to outgroup prejudice and support for authoritarian policies (e.g. Osborne et al. Citation2023). Naturally, intrinsic and extrinsic conditions influencing TPF-PS have been investigated extensively over the past decades. In this light, mass media has long been singled out as responsible for exaggerated TPF-PS following cultivation theory (Gerbner Citation1998) and other prominent theoretical approaches on media effects such as agenda-setting theory, reinforcing spirals theory, or framing theory (for a general theoretical overview, see Valkenburg, Peter, and Walther Citation2016). Research examining how news consumption (NC) is related to TPF-PS is still attracting substantial scholarly interest (Potter Citation2022). This academic interest is growing particularly due to the unique challenges involved with current media landscapes (Morgan, Shanahan, and Signorielli Citation2014).

In participatory democracies, news reporting serves the crucial function to inform the public about significant events in order to facilitate their involvement in political discourses. Institutionalized actors (e.g. editorial staffs, journalists, news anchors) across traditional media like newspapers, radio, and TV have fulfilled this function for many decades. However, social media, together with the widespread prevalence of smartphones, has changed people’s NC fundamentally (Kümpel Citation2022). That is, the widespread adoption of smartphones has facilitated unprecedented access to news content, enabling users to stay continuously connected to information sources throughout the day. This following shift in NC behavior, characterized by constant connectivity and on-the-go access, has significant implications for how individuals perceive and respond to threats in their environment.

A scoping review (see Munn et al. Citation2018) can be a suitable way to gain a systematic overview of certain research efforts in order to identify current mainstream trends and, more importantly, diagnose deficits that may bias the field and impair its societal utility. There are systematic reviews that address the role of (social) media for risk and crisis communication (Rasmussen and Ihlen Citation2017; Wahlberg and Sjoberg Citation2000) and also meta-analyses that test links between overall media consumption and public risk perception (Niu et al. Citation2022)—a particularly challenging task given that the body of literature exhibits many heterogeneous phenomena. What is currently lacking, however, is a methodologically sound systematization concerning the features of empirical studies that deal with NC and TPF-PS.

For this purpose, we conducted a scoping review focusing on empirical literature about links between people’s NC and TPF-PS since the advent of the smartphone era (starting with the introduction of the iPhone in 2007). The advent of the smartphone era serves as a significant milestone for investigating NC in modern media landscapes and its link to TPF-PS for two reasons. First, it represents a significant inflection point in the history of media technology, marking the beginning of a mobile era characterized by ubiquitous connectivity. Second, through a clear temporal boundary around the smartphone era, we can ensure that our review focuses on the most relevant and contemporary empirical literature.

Our review contributes to existing research by pursuing a threefold objective: First, the review identifies both prevalent theoretical and methodological approaches, as well as sample characteristics and sampling methods in this research field. Second, it outlines previous operational approaches of the two primary concepts (i.e. TPF-PS and NC). Third, in line with methodological approaches of recent scoping reviews on other topics [e.g. incidental news exposure (Schäfer Citation2023) or social media effects on well-being (Valkenburg, van Driel, and Beyens Citation2022)], the present study aims to categorize the identified operationalizations of NC and TPF-PS into two main classifications and examine their types of association while also considering region-based differences.

Objectives of the present study

Theories, methodologies, and samples

Since its beginnings, media effects research has developed several micro-level theories that withstood the test of time (or rather evolved during it) and remained highly relevant today (see Valkenburg, Peter, and Walther Citation2016). For NC effects in particular, and arguably even more so concerning people’s TPF-PS, some of these well-established theories have also been applied heavily. Most notably, explorative adaptations of cultivation theory (Gerbner Citation1998) that argue for a socializing impact of repeated exposure to sensationalist (local) news reporting, alongside framing theory (Entman Citation1993), which posits that any news content can influence audience perceptions by presenting information in a certain way, have been commonly used as a theoretical background (e.g. Chadee, Smith, and Ferguson Citation2019; De Coninck et al. Citation2021). Other popular approaches like information processing theories [e.g. adaptions of the elaboration likelihood model (Petty and Cacioppo Citation1986) or the limited capacity model (Lang Citation2000)], uses-and-gratification theory (Ruggiero Citation2000), or the reinforcing spiral model (Slater Citation2007) also appear promising to predict and explain nuanced effects on threat perceptions (see, e.g. Matthes, Schmuck, and von Sikorski Citation2019; Williamson, Fay, and Miles-Johnson Citation2019). Beyond these major theories, domain-specific approaches which may have originated in related disciplines [e.g. social identity theory (Tajfel and Turner Citation2004) and intergroup threat theory (Stephan and Stephan Citation2000)], may play an important role in current theoretical thinking (e.g. Lissitsa, Kushnirovich, and Steinfeld Citation2023). By systematically determining the theoretical state-of-the-art, it may be possible to identify dominant lenses through which NC is empirically approached as well as peripheral viewpoints that might allow for unique (maybe even disruptive) predictions to expand our understanding of the phenomenon in question. Accordingly, we asked:

RQ1: What theoretical approaches are prevalent in the sampled literature?

RQ2: What methodological approaches are prevalent in the sampled literature?

Concerning sample populations, communication scholars have noted a predominance of samples including people from so-called WEIRD (i.e. western, educated, industrialized, rich, democratic) societies that do not represent the vast majority of the world population and thus put the generalizability and transferability of evidence into question (Bates Citation2021). What is more (and closely related to some non-probability sampling methods) is that samples often do not resemble existing heterogeneity within WEIRD societies but instead tend to draw from a higher educated, racially less diverse, and more socio-economically advantaged subpopulation that is university students.

Given their potential relevance, these well-known challenges concerning sampling methods and sample populations may arguably be even more pressing for empirical inquiries into people’s TPF-PS. It is therefore imperative to obtain an overview of the state of the field, which is why we asked:

RQ3: What a) sample characteristics and b) sampling methods are prevalent in the sampled literature?

Operationalizations of TPF-PS and NC

Threat perception is often considered an ambiguous construct in terms of available operationalizations because its phenomenological and conceptual vicinity to fear responses (toward perceived threats) have troubled researchers across different disciplines (see, e.g. LeDoux Citation2014; LaTour and Rotfeld Citation1997). Concerning research on TPF-PS, this ambiguity can be observed for common construct pairings (e.g. crime perception and fear of crime, perceived victimization risk and fear of victimization, or terrorism threat perceptions, and fear of terrorism) where the former represent people’s varying awareness about undesirable circumstances and the latter describe their emotional response to these circumstances. Although this distinction might appear to be conceptually reasonable, it is not self-evident that it is also strictly followed through in standard self-report items, such that threat perceptions and self-perceived fears may occasionally be used (close to) synonymously. To account for this, we opted for accepting operationalizations of both threat perceptions and related fears in this scoping review.

When it comes to public threat domains, researchers typically have to decide between holistic and domain-specific operationalizations (e.g. crime perception vs. violent crime perception) that can differ in terms of their reference, for instance, to broad or more narrow geographical locations (e.g. national vs. regional crime perception; e.g. Ramírez-Álvarez Citation2021) or different groups of actors (e.g. perceived threat of distinct immigrant populations; e.g. Theorin Citation2022) and patients (e.g. fear for oneself vs. fear for one’s family or friends; e.g. Nellis and Savage Citation2012). It is therefore essential to obtain a comprehensive overview on what operational approaches may be predominant (or even overrepresented, perhaps so much so that additional work might only incrementally advance our knowledge) and which ones might be promising but neglected (such that a stronger emphasis might be worthwhile). Thus, we asked:

RQ4a: How is TPF-PS operationalized in the sampled literature?

Accordingly, research is forced to adapt to these modern (and further dynamically changing) landscapes in order to still be able to address people’s lived NC routines without leaving significant portions in the dark. Besides that (and similar to TPF-PS), NC operationalizations may also differ substantially with respect to their granularity (e.g. private vs. public TV channels, or local vs. national vs. international newspapers, or internet vs. social media vs. Twitter/X) or their topical specificity (e.g. general news coverage vs. news about terrorism vs. news about particular events). Furthermore, the nature of modern media landscapes illustrates that properties of media that are otherwise separated into individual devices are combined into one medium (e.g. NC on smartphones). As discussed in other scoping reviews (e.g. on incidental news exposure; Schäfer Citation2023), this further emphasizes the role of end-user devices.

Against this background, a scoping review affords an opportunity to explore whether current research is keeping up with current developments and uncover latest trends as well as crucial blind spots in how NC is operationalized when it comes to studying its link to TPF-PS.

RQ4b: How is NC operationalized in the sampled literature?

Association trends and region-based differences

Scoping reviews are viewed as a useful approach to systematically analyzing quantitative empirical evidence on a topic. As outlined above, it is very likely that previous research on NC and TPF-PS includes different, more or less overlapping, or otherwise vaguely defined construct operationalizations. Hence, in line with the methodological approaches of prior scoping reviews (Schäfer Citation2023; Valkenburg, van Driel, and Beyens Citation2022), we intend to test whether their associations differ across traditional and digital/online & multichannel NC as well as across fear-related and not fear-related concepts of TPF-PS. In addition, this review aims to identify region-based differences by categorizing the identified operationalizations of NC and TPF-PS into two primary classifications.

RQ5: What a) types of association and b) region-based differences can be identified in the sampled literature in relation to the two main concepts?

Method

Eligibility criteria

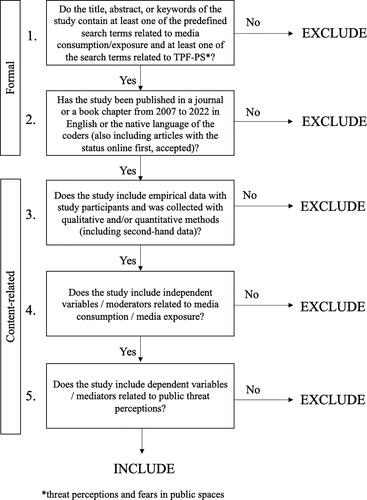

All empirical papers must fulfill several criteria in order to be included. First, papers must involve data collections with human participants, regardless of whether they use quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods (referred to as empirical study). Hence, the present scoping review does not cover other publication forms such as reviews, meta-analyses, or only theory-based studies. Second, at least one term related to media consumption/exposure and at least one term related to TPF-PS must appear in the respective title, abstract, or keywords. Third, papers either have to be published in academic journals or book chapters (including online-first publishing formats). Fourth, they must be written in English or German (i.e. languages that the authors understand proficiently). Fifth, records must be published between 2007 and 2023. As the first iPhone generation was available in 2007, we decided to set this time frame as it best marks the beginning of the smartphone era. Sixth, papers must address the relation between NC and TPF-PS. Accordingly, we exclude threat perceptions that are not triggered by humans (e.g. natural emergencies; Gutteling, Terpstra, and Kerstholt Citation2018) and personal safety evaluations in non-public (e.g. violence against women or misogyny in private areas) or virtual (e.g. cybercrime) settings, as well as fear-related concepts related to individual concerns about sanitary or health safety (e.g. individual fear of Covid-19 risk; Dryhurst et al. Citation2020). visualizes our inclusion criteria by differentiating and partially summarizing both formal and content-related criteria.

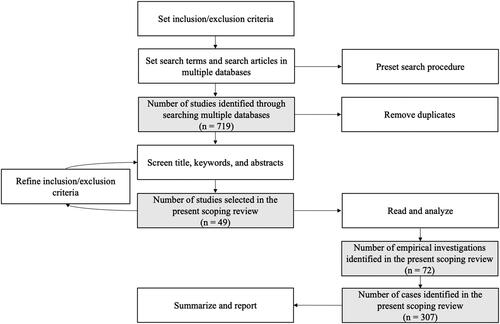

Search procedure

To identify relevant papers, we utilized Web of Science and Scopus as two well-established academic databases (see Appendix A for search items). We preset our search by only including a) papers from 2007 to 2023, b) articles, book chapters, early access, and conference papers, c) relevant research areas, and d) articles in English and German. On May 18, 2023, a total of N = 719 papers was identified (Web of Science: 315; Scopus: 404). Based on subsequent (iterative) screening of titles, abstracts, and full texts, N = 49 papers were included (see Appendix B).

Coding procedure

Coding was performed by the first and second authors. During initial coding, which in total consisted of 15 randomly selected papers, we went through three coding rounds to arrive at acceptable inter-coder reliability across each category (i.e. Krippendorf’s α > 0.80). Afterward, we randomly assigned the 34 remaining papers to one of both coders. Each operational definition of NC and TPF-PS constituted a separate case. Since we are interested in sample characteristics and sampling methods, additional coding units represented a) subsamples for different countries and b) each empirical study conducted within a single paper (e.g. two-study papers). Overall, this led to N = 72 empirical studies as well as N = 307 operational definitions of NC and TPF-PS (see for an overview).

Collected data items

Measures for meta information

Unrelated to any RQs, we first retrieved titles, author names, publication year, and the name of the journal/book. For answering RQ1 and RQ2, we determined the main theory related to our variables of interest (α = 0.84) by examining whether specific theories or theoretical keywords were referred to (see Appendix C) using both an open category and an a priori categorization. Based on previous scoping reviews (e.g. Schäfer Citation2023), we also coded methodology (quantitative, qualitative, or mixed; α = 1.00), method (cross-sectional survey, longitudinal survey, experiment, eye tracking, focus group interviews, individual interviews, observation, or mixed methods by applying two or more different methods; α = 1.00), and study setting (online, offline; α = 1.00).

For answering RQ3, we first indicated whether a probability or non-probability sampling method was used (α = 1.00). Based on Rasmussen and Ihlen (Citation2017), we also coded the sample region (α = 1.00). Moreover, information on studied populations (α = 0.97) and sample gender distribution (α = 1.00) was investigated. Finally, we recorded if ethnicity or race (α = 1.00) was taken into account for analyses and what kind of socioeconomic factors (including education, financial situation, employment status, and area of residence) were reported (α = 0.95).

Measures for subject matter information

For answering RQ4, we first determined what kind of operational definitions of TPF-PS a paper included (RQ4a). Based on previous research, coding categories included a) fear of (violent) crime, b) threat/crime (trend) perceptions, c) fear of terror, and d) fear of victimization. Additionally, we included a category that indicated the topical specificity of the given operationalizations (α = 1.00). Regarding RQ4b, we coded whether operational definitions of NC of a paper assessed a) media use in general or, more specifically, b) NC [online/digital (online news articles, internet NC, and NC on websites) vs. offline/traditional (e.g. TV, newspaper, radio)], c) NC on social media, or d) NC with regard to a specific topic (e.g. terrorist attacks). We further coded for mixed measurements and thus multichannel NC (i.e. mergers of offline and online NC, for instance, combined operationalizations of NC via TV, Facebook, print and online news) (α = 0.95).

In two open categories, we recorded the given names of all operational definitions of NC and TPF-PS. Furthermore, for getting a detailed picture, we assessed the type of end-user device (smartphones, tablets/laptops/PCs, television, radio, or print; α = 0.89). Additionally, once the role of social media was investigated, we also recorded whether studies focused on specific networks or generic social media use.

Finally, concerning RQ5, we assessed the type of association (i.e. none, positive, negative, or mixed) between NC and TPF-PS (α = 0.99). For exploratory purposes (not reported here), we also wrote a brief report of the qualitative studies’ main findings.

Results

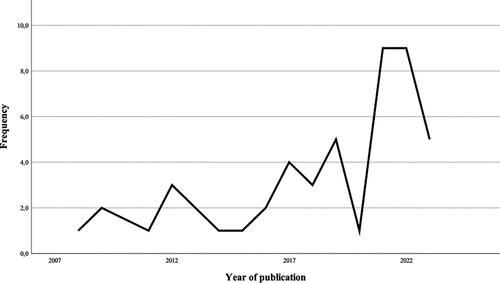

Out of the total of 49 papers, only two were published as book chapters. The remaining papers were journal articles. illustrates a timeline for publication years, revealing that empirical research on the relationship between NC and TPF-PS peaked after 2020.

Theoretical and methodological approaches

RQ1 asked for the prevalence of theories across sampled papers. While 22.4% (n = 11) did not refer to any specific theory, a majority applied cultivation theory (44.9%, n = 22). Apart from that, several investigations referred to the theoretical premises of framing and priming (14.3%, n = 7) or involved other media-related theories with a focus on the individual and the topic [e.g. intergroup threat theory, hostile media effect; 14.3% (n = 7)]. None of the included studies referred to news value theory and only one study each referred to information processing theories or uses and gratification approaches (2%, n = 1 for each).

Concerning the methodological approaches (RQ2), most empirical studies (N = 72) applied a quantitative methodology (93.1%, n = 67), with cross-sectional surveys (63.9%, n = 46), experiments (18.1%, n = 13), and longitudinal surveys (11.1%, n = 8) being the most prevalent methods. The remaining studies with qualitative methodology (6.9%, n = 5) either engaged in individual interviews (4.2%, n = 3) or focus group discussions (2.8%, n = 2). Regarding the setting, more than half of the sampled empirical studies took place online (56.3%, n = 40, 1 missing value). While most of the remaining studies preferred an offline setting (40.8%, n = 29), two studies (2.8%) combined online and offline settings.

Sample characteristics and sampling methods

Concerning sample characteristics (RQ3a), most empirical studies were carried out in North America (34.7%, n = 25), Northern/Western Europe (26.4%, n = 19), South/Eastern Europe (13.9%, n = 10), and Central America (11.1%, n = 8). Samples from Western Asia (5.6%, n = 4), Eastern/Southeastern Asia (2.8%, n = 2), South America (1.4%, n = 1), Oceania (1.4%, n = 1), or multinational samples (2.8%, n = 2) were rare.

A large majority of studies (70%, n = 49, 2 missing values) only included adults (i.e. starting from 18 years), whereas some studies combined adults and participants younger than 18 years (18.6%, n = 13). Only a small proportion of studies focused specifically on children and teenagers (2.9%, n = 2) and 8.6% (n = 6) exclusively examined students.

Most empirical studies achieved a balanced gender distribution for their samples (maximum 40/60; 84.1%, n = 58, 3 missing values). Unbalanced gender distributions only included a higher proportion of female (versus male) participants (15.9%, n = 11). Concerning other sociodemographic indicators, many studies considered both participants’ education levels (80.6%, n = 58) and indicators for participants’ socioeconomic status based on their area of residence (44.4%, n = 32). Participants’ financial situation (37.5%, n = 27) and their current employment status (25%, n = 18) were rarely included in the analysis. A total of 41.7% (n = 30) studies addressed participants’ ethnicity or race in their analyses.

Regarding sampling methods (RQ4b), n = 8 empirical studies provided no further information. The remaining 64 cases predominantly showcased non-probability (67.2%, n = 43) compared to probability sampling (32.8%, n = 21).

Operational definitions for main concepts

To obtain a comprehensive overview of the operational approaches of TPF-PS (RQ4a) and NC (RQ4b), we take a closer look at all coded operationalizations of NC and TPF-PS (N = 307). Concerning TPF-PS (RQ4a), many empirical studies conceptualized TPF-PS as a fear-related concept (i.e. 46.6%, n = 143). Other studies measured general threat perceptions related to specific actor groups (40.4%, n = 124) or determined people’s general crime (trend) perceptions (6.8%, n = 21). Few exceptions (6.2%, n = 19) addressed concepts related to people’s coping or, more specifically, avoidance behavior (e.g. perceived likelihood of future self-protective action).

Three fears were predominant: a) fear of (violent) crimes (25.7%, n = 79), b) fear of terror/terrorism (13.4%, n = 41), and c) fear of victimization (7.5%, n = 23). Interestingly, a large majority of fear measures were related to people’s fear for oneself (88.1%, n = 126), hardly asking for peoples’ fears for others (2.8%, n = 4), except for some composite measures of fear for another’s and one’s own safety (9.1%, n = 13). Studies also rarely differentiated narrow geographical locations (18.9%, n = 58). That is, only 7.2% (n = 22) of operationalizations referred to broad geographical areas (e.g. national, country, state) and another 9.4% (n = 29) to more narrow locations (e.g. urban, community, neighborhood, rural, municipality). However, some studies made use of combined measurement of national and regional fears (2.3%, n = 7).

Concerning the operational definition of NC (RQ4b), sampled operationalizations manifested a preference for traditional NC/exposure in general (41.0%, n = 126) as well as NC with respect to specific topics (29.3%, n = 90). Among these topics, three emerged as most notable: a) news about terrorism/terrorists (45.6%, n = 41), b) news about immigrants, refugees, or asylum seekers (36.7%, n = 33), and c) news involving (violent) crime scenarios (17.8%, n = 16). Less prevalent but still noteworthy, several studies operationalized NC by merging offline and online exposures (15%, n = 46). Empirical studies that measured people’s NC on social media (without referring to specific topics and merging offline and online NC/exposure) constitute a rarity (5.5%, n = 17), just as it is the case for overall media consumption/exposure (3.9%, n = 12), online-only NC (3.3%, n = 10), and general internet use (2%, n = 6). Of the empirical studies that somehow included NC on social media (i.e. additionally including those empirical studies that either referred to social media within a merged operationalization of NC or to social media news on specific topics) , most did not specify specific platforms (n = 25). If platforms were specified, Twitter n = 8) and Facebook n = 10) were most commonly investigated, alongside a weaker emphasis on WhatsApp n = 2), WeChat n = 1), and other platforms (n = 2).

Looking at end-user devices, roughly 1 out of 4 operationalizations did not mention the specific end-user device at all (25.4%, n = 78). When end-user devices were specified for traditional NC, TV (39.4%, n = 121) and print media emerged as most relevant (10.7%, n = 33), dominating radio (3.9%, n = 12). When it comes to online media, not a single study clearly indicated the specific end-user device (smartphones, tablets/laptops/PCs). Most commonly, operationalizations combined several end-user devices in a composite measure (20.5%, n = 63).

Type of association differentiated by main concepts

To determine general association trends between our variables of interests (RQ5a), we coded quantitative investigations (per operationalization) for whether they identified no significant (57%, n = 171), a positive (28.0%, n = 84), or a negative association (9.7%, n = 29). Mixed findings (i.e. where non-significant, positive, and negative associations came up for different analytical techniques or when including additional control variables; 5.3%, n = 16) were disregarded here.

We first recoded TPF-PS operationalizations, creating a nominal variable (concept type) that distinguishes between fear-related concepts (i.e. fear of crime, fear of terror, and fear of victimization) and general threat and crime (trend) perceptions as the primary research foci (excluding seldom examined variables like coping/avoidance behaviors). A Pearson chi-square test showed a small-sized significant relationship between association type and concept type (χ2(2, n = 265) = 9.41, p < 0.01, Cramer’s V = 0.19). As displays, empirical studies most often found no significant associations between NC and TPF-PS. When only counting significant associations, positive links (i.e. higher NC comes with increased TPF-PS, and vice versa) occurred more often than negative ones (i.e. higher NC comes with decreased TPF-PS, and vice versa). Compared to general threat and crime (trend) perceptions, negative links were less common for fear-related concepts.

Table 1. Crosstabulation for the link between type of association and concept type.

Secondly, we also recoded NC operationalizations, again creating a nominal variable named NC type where we differentiated between traditional/offline NC (i.e. receiving news from traditional media institutions such as newspapers) and digital/online & multichannel NC (including online NC, social media NC, and the combined consumption of offline and online news) as theoretically most interesting focus points (excluding generic measures like overall media consumption and internet use not news-related). Another Pearson chi-square test pointed toward a medium-sized significant relationship between association type and NC type (χ2(2; n = 243) = 14.53, p < 0.01, V = 0.25). As can be observed in , significant differences across NC types again occurred only for negative associations, which were significantly less often identified for digital/online & multichannel NC.

Table 2. Crosstabulation for the link between type of association and news consumption type.

Region-based differences between main concepts

For investigating region-based differences (RQ5b), we created a nominal variable differentiating between North America (44.0%, n = 135) and other regions (56.0%, n = 172). Pearson chi-square testing demonstrated a medium-sized significant relationship between region and concept type (χ2(1; n = 288) = 20.41, p < 0.001, V = 0.27). More specifically, general threat and crime (trend) perceptions are more commonly researched outside North America (see ). Pearson chi-square testing also showed a small-sized significant relationship between region and NC type (χ2(1; n = 263) = 4.52, p < 0.05, V = 0.13), revealing that digital/online & multichannel NC is also more commonly researched in other regions than North America (see ).

Table 3. Crosstabulation for the link between region and concept type.

Table 4. Crosstabulation for the link between region and news consumption type.

Discussion

This scoping review investigates the empirical literature about links between people’s NC and TPF-PS since the advent of the smartphone era. Our findings provide several valuable insights. First, when looking at the theoretical state-of-the-art, cultivation theory (Gerbner Citation1998) and media-related theories with a focus on the individual are the dominant lenses through which NC is empirically approached. Besides these main theoretical approaches, it is also noteworthy that many studies lack any kind of clear theoretical foundation, indicating that exploratory perspectives are co-existing next to theory-driven research (Levine and Markowitz Citation2023).

While research most commonly applied explorative adaptations of cultivation theory (Gerbner Citation1998) and framing theory (Entman Citation1993) as their theoretical background (e.g. Chadee, Smith, and Ferguson Citation2019; De Coninck et al. Citation2021), theoretical reconsiderations are visible following the proposition of more deeply involved media users (e.g. Lissitsa, Kushnirovich, and Steinfeld Citation2023). As a prime example of this trend, Williamson, Fay, and Miles-Johnson (Citation2019) revealed that receiving information about terrorism from multiple media sources increases fear of terrorism, but media sources accessed passively (e.g. TV, radio) are not as influential as media sources accessed more actively (e.g. internet). Indeed, particularly when focusing on digital/online & multichannel NC, studies only found partial support for cultivation theory (e.g. Intravia et al. Citation2017), suggesting that it may be somewhat outdated and cannot be transferred straightforwardly to contemporary media and NC. However, given that similar issues with lacking empirical support are also occasionally raised for traditional NC, it might also be that cultivation theory in itself is in need of a conceptual update (see Potter Citation2022).

Furthermore, our results further indicate that researchers’ theoretical choices are not one-dimensional, but instead often contingent upon whatever topic is investigated. For instance, some studies examined NC and TPF-PS with regard to specific actors, such as refugees. Due to this topical focus, these studies were more likely to draw on more concrete theories that are specifically suited for it (e.g. intergroup threat theory or hostile media effects). Additionally, in the absence of prolonged exposures, one-off-exposure experiments typically do not argue with cultivation effects (but rather rely on domain-specific approaches which may have originated in related disciplines (see, e.g. Matthes, Schmuck, and von Sikorski Citation2019).

Second, our scoping review emphasizes several methodical shortcomings. Most obviously, qualitative methods (and, by that, social-constructivist and interpretative perspectives) constitute a rarity in this research field. However, quantitative methods are not without issues. Here, we identified a dearth of longitudinal and experimental methods, especially those involving behavioral indicators. In fact, long-term studies and experiments only made up a small part of our sampled empirical studies, resulting in a lack of insights into temporality and causality. Proper experimental designs in particular might provide us with much-needed insights into idiosyncratic communication experiences triggered by news articles about public safety topics. On an operational level, it also needs to be noted that most research focuses primarily on people’s awareness about undesirable circumstances (e.g. crime perception) and/or the extent of their emotional response to these circumstances (e.g. fear of crime), thus neglecting behavioral responses (e.g. whether and how NC affects coping and avoidance strategies). Crucially, most of these issues may be best addressed via mixed-method approaches; however, here we have to point toward yet another, perhaps even more profound shortage as our sampled studies were either quantitative or qualitative without attempting to embrace strengths and overcome weaknesses by combining both methodologies.

Third, we systematically determined prevalences across different sample characteristics and sampling methods. Regarding sample populations, communication scholars (similar to other disciplines) have put into question the generalizability of evidence given samples predominantly include people from so-called WEIRD societies (Bates Citation2021). In a majority of cases, the same can be said to be true for empirical inquiries into people’s NC and TPF-PS where non-probability samples from North America or Northern/Western Europe are predominant. This corresponds with the results of other communication sciences reviews (Erba et al. Citation2018) and questions the generalizability of available quantitative evidence. Interestingly, many studies control for educational differences among their participants as well as, somewhat exceptionally, various residential indicators (e.g. urban vs. rule, region, place of origin, neighborhood). However, a stronger focus on other socioeconomic factors (e.g. participants’ current employment status or financial situation) might increase adjustment to existing heterogeneity within WEIRD societies.

Fourth, our review provides a comprehensive overview on what operational approaches of TPF-PS and NC are predominant in the literature. For the former, it became clear that previous operationalizations almost equally in numbers represent either people’s varying awareness about undesirable circumstances (i.e. sense-of operationalizations) or their emotional response to these circumstances (i.e. fear-of operationalizations). This finding therefore underlines the assumptions of TPF-PS as an ambiguous construct. Notably, in the case of fear-of operationalizations, fear for (significant) others’ safety is hardly researched, even though other-directed fears may be as important as (or perhaps sometimes even more important) than fear for one’s own safety.

Concerning NC operationalizations, it can be considered alarming that only a small proportion of the empirical studies explicitly considered digital/online & multichannel NC. That is, despite the worldwide advent of smartphones during the past 15 years, digital/online NC and social media NC in particular is hardy researched in relation to TPF-PS. It is further surprising that examinations of online or/and social media NC often makes no reference to end-user devices, meaning that existing research in this field largely neglects specific characteristics of online and social media (Intravia et al. Citation2017).

Lastly, when breaking down operationalizations into a) fear-related concepts and general threat and crime (trend) perceptions and b) traditional/offline and digital/online & multichannel NC, it appears that significant differences between these main operationalization types are primarily found for negative associations. Moreover, both concepts related to general threat and crime (trend) perceptions as well as digital/online & multichannel NC are understudied in North America (i.e. where the majority of empirical research has been conducted).

Limitations and implications for future research

The findings of this scoping review are subject to several limitations, which come with clear implications for future work. First, each scoping review addresses their topics by selecting specific search terms. Even though this review has indeed defined a large number of word combinations in order to cover available research (see Appendix A), these search terms can never be complete, such that empirical studies that could be relevant may not be included in our sample. A second limitation concerns the use of significance levels instead of effect sizes (following Valkenburg, van Driel, and Beyens Citation2022) when exploring association types. Third, it needs to be mentioned that we only considered empirical papers written in English and German which might have led us to miss relevant findings written in other languages.

Based on the findings of our scoping review (and the continuing scholarly interest in links between NC and TPF-PS), we also have to discuss implications for future research. From a methodological point of view, future research needs to make better use of mixed-method designs as combining paradigms is the way to maximize validity. Furthermore, as cross-sectional quantitative research does not allow for solid insights into causal mechanisms (see Grosz, Rohrer, and Thoemmes Citation2020), researchers should be encouraged to conduct longitudinal and experimental studies. In line with other authors (e.g. Intravia et al. Citation2017), we also argue the need for more specific and nuanced operationalizations, particularly for digital/online and social media NC that take into account idiosyncrasies of different platforms and end devices, that meet current NC practices. For that our knowledge in this research field gets expanded, examining dependent variables related to coping or avoidance behaviors might be a promising focus that is distinct from fear-related and threat perception constructs. For instance, novel insights could be obtained when adverse feelings such as fear that are directly related to a particular crime are investigated alongside individuals’ behavioral actions (e.g. avoiding going out at night).

Our results for association types beg the question whether greater digital/online & multichannel NC can also reduce TPF-PS. In line with cultivation theory, previous research has focused primarily on the extent to which NC increases TPF-PS, that is, negative outcomes. A reconsideration of possible positive outcomes of NC might be promising here to understand how NC relates to TPF-PS in modern media landscapes. Finally, it is clear that future research needs to focus on other regions than the United States and Northern/Western Europe.

Conclusion

This scoping review of empirical research examining how people’s NC is related to their TPF-PS offers a systematic overview of current mainstream trends and, most importantly, diagnoses deficits that may bias the field and impair its societal utility. First and foremost, future research is nothing less than forced to adapt to dynamically changing landscapes in order to stay relevant. Against this background, the findings of the present scoping review suggest a pressing need for more qualitative studies, experiments, and longitudinal studies, as well as a better approach to digital/online & multichannel NC. Only when creating more specific and nuanced operationalizations for contemporary online and social media NC, researchers will be able to understand people’s lived NC routines, so that they can better inform public discourse and political decision-making.

Funding details

Funded by the Austrian Research Promotion Agency (Grant number: FO999895140)

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Excluding Transplanation, Physiology, Physical Geography, Obstretrics Gynecology, Neurosciences, Microbiology, Mathematics, Mathematical Methods in Social Sciences, Materials Science, Literature, Linguistics, History Philosophy Of Science, History, Evolutionary Biology, Development Studies, Arts Humanities Other Topics, Art, Water Resources, Surgery, Religion, Pediatrics, Meterology Atmospheric Sciences, Geology, Geography, General Internal Medicine, Food Science Technology, Energy Fuels, Emergency Medicine, Biodiversity Conservation, Agriculture, Social Work, Research Experimental Medicine, Oncology, Infectious Diseases, Zoology, Transportation, Substance Abuse, Rehabilitation, Immunology, Biomedical Social Sciences, International Relations, Geriatrics Gerontology, Nursing, Medical Informatics, Engineering, Environmental Sciences Ecology.

2 Excluding Chemical Enginerring, Chemistry, Veterinary, Neuroscience, Materials Science, Health Professions. Earth and Planetary Sciences, Immunology and Microbiology, Physics and Astronomy, Biochemistry, Genetics, and Molecular Bilology, Pharmacology, Toxiology and Pharmaceutics, Energy, Agricultural and Biological Sciences, Mathematics, Medicine, Nursing.

References

- Bates, Benjamin R. 2021. “Making Communication Scholarship Less WEIRD.” Southern Communication Journal 86 (1): 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1080/1041794X.2020.1861078.

- Chadee, Derek, Sven Smith, and Christopher J. Ferguson. 2019. “Murder She Watched: Does Watching News or Fictional Media Cultivate Fear of Crime?” Psychology of Popular Media Culture 8 (2): 125–133. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000158.

- Cornesse, Carina, Annelies G. Blom, David Dutwin, Jon A. Krosnick, Edith D. De Leeuw, Stéphane Legleye, Josh Pasek, et al. 2020. “A Review of Conceptual Approaches and Empirical Evidence on Probability and Nonprobability Sample Survey Research.” Journal of Survey Statistics and Methodology 8 (1): 4–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/jssam/smz041.

- De Coninck, David, Christine Ogan, Lars Willnat, and Leen d’Haenens. 2021. “Mediatized Realities of Migrants in a Comparative Perspective: Media Use, Deservingness, and Threat Perceptions in the United States and Western Europe.” International Journal of Communication 15: 2506–2527.

- Dryhurst, Sarah, Claudia R. Schneider, John Kerr, Alexandra L. J. Freeman, Gabriel Recchia, Anne Marthe van der Bles, David Spiegelhalter, and Sander van der Linden. 2020. “Risk Perceptions of COVID-19 Around the World.” Journal of Risk Research 23 (7–8): 994–1006. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2020.1758193.

- Entman, Robert M. 1993. “Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm.” Journal of Communication 43 (4): 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1993.tb01304.x.

- Erba, Joseph, Brock Ternes, Piotr Bobkowski, Tara Logan, and Yuchen Liu. 2018. “Sampling Methods and Sample Populations in Quantitative Mass Communication Research Studies: A 15-Year Census of Six Journals.” Communication Research Reports 35 (1): 42–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2017.1362632.

- Gerbner, George. 1998. “Cultivation Analysis: An Overview.” Mass Communication and Society 1 (3–4): 175–194. https://doi.org/10.1080/15205436.1998.9677855.

- Grosz, Michael P., Julia M. Rohrer, and Felix Thoemmes. 2020. “The Taboo Against Explicit Causal Inference in Nonexperimental Psychology.” Perspectives on Psychological Science: A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science 15 (5): 1243–1255. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620921521.

- Gutteling, Jan M., Teun Terpstra, and José H. Kerstholt. 2018. “Citizens’ Adaptive or Avoiding Behavioral Response to an Emergency Message on Their Mobile Phone.” Journal of Risk Research 21 (12): 1579–1591. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2017.1351477.

- Intravia, Jonathan, Kevin T. Wolff, Rocio Paez, and Benjamin R. Gibbs. 2017. “Investigating the Relationship Between Social Media Consumption and Fear of Crime: A Partial Analysis of Mostly Young Adults.” Computers in Human Behavior 77: 158–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.08.047.

- Kümpel, Anna S. 2022. “Social Media Information Environments and Their Implications for the Uses and Effects of News: The PINGS Framework.” Communication Theory 32 (2): 223–242. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtab012.

- Lang, Annie. 2000. “The Limited Capacity Model of Mediated Message Processing.” Journal of Communication 50 (1): 46–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2000.tb02833.x.

- LaTour, Michael S., and Herbert J. Rotfeld. 1997. “There Are Threats and (Maybe) Fear-Caused Arousal: Theory and Confusions of Appeals to Fear and Fear Arousal Itself.” Journal of Advertising 26 (3): 45–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1997.10673528.

- LeDoux, Joseph E. 2014. “Coming to Terms with Fear.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 111 (8): 2871–2878. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1400335111.

- Lehdonvirta, Vili, Atte Oksanen, Pekka Räsänen, and Grant Blank. 2021. “Social Media, Web, and Panel Surveys: Using Non‐Probability Samples in Social and Policy Research.” Policy & Internet 13 (1): 134–155. https://doi.org/10.1002/poi3.238.

- Levine, Timothy R., and David M. Markowitz. 2023. “The Role of Theory in Researching and Understanding Human Communication.” Human Communication Research 50 (2): 154–161. https://doi.org/10.1093/hcr/hqad037.

- Lissitsa, Sabina, Nonna Kushnirovich, and Nili Steinfeld. 2023. “Carry‐over Effect of Single Media Exposure and Mass‐Mediated Contact with Remote Outgroups: From Asylum Seekers in Europe to an Israeli Local Outgroup.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 53 (8): 752–769. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12965.

- Matthes, Jörg, Desirée Schmuck, and Christian von Sikorski. 2019. “Terror, Terror Everywhere? How Terrorism News Shape Support for Anti‐Muslim Policies as a Function of Perceived Threat Severity and Controllability.” Political Psychology 40 (5): 935–951. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12576.

- Meltzer, Christine E., Thorsten Naab, and Gregor Daschmann. 2012. “All Student Samples Differ: On Participant Selection in Communication Science.” Communication Methods and Measures 6 (4): 251–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2012.732625.

- Morgan, Michael, James Shanahan, and Nancy Signorielli. 2014. “Cultivation Theory in the Twenty‐First Century.” In The Handbook of Media and Mass Communication Theory, edited by Robert S. Fortner and P. Mark Fackler, 480–497. Newark, NJ: Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118591178.ch26.

- Munn, Zachary, Micah D. J. Peters, Cindy Stern, Catalin Tufanaru, Alexa McArthur, and Edoardo Aromataris. 2018. “Systematic Review or Scoping Review? Guidance for Authors When Choosing between a Systematic or Scoping Review Approach.” BMC Medical Research Methodology 18 (1): 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x.

- Nellis, Ashley Marie, and Joanne Savage. 2012. “Does Watching the News Affect Fear of Terrorism? The Importance of Media Exposure on Terrorism Fear.” Crime & Delinquency 58 (5): 748–768. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128712452961.

- Niu, Chunhua, Zhixin Jiang, Hongbing Liu, Kehu Yang, Xuping Song, and Zhihong Li. 2022. “The Influence of Media Consumption on Public Risk Perception: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Risk Research 25 (1): 21–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2020.1819385.

- Osborne, Danny, Thomas H. Costello, John Duckitt, and Chris G. Sibley. 2023. “The Psychological Causes and Societal Consequences of Authoritarianism.” Nature Reviews Psychology 2 (4): 220–232. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44159-023-00161-4.

- Parry, Douglas A., Jacob T. Fisher, Hannah Mieczkowski, Craig J. R. Sewall, and Brittany I. Davidson. 2022. “Social Media and Well-Being: A Methodological Perspective.” Current Opinion in Psychology 45: 101285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.11.005.

- Petty, Richard E., and John T. Cacioppo. 1986. “The Elaboration Likelihood Model of Persuasion.” In Communication and Persuasion, edited by Richard E. Patty and John T. Cacioppo, 1–24. New York: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-4964-1_1.

- Potter, W. James. 2022. “What Does the Idea of Media Cultivation Mean?” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 66 (4): 540–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2022.2131788.

- Ramírez-Álvarez, Aurora A. 2021. “Media and Crime Perceptions: Evidence from Mexico.” The Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 37 (1): 68–133. https://doi.org/10.1093/jleo/ewaa010.

- Rasmussen, Joel, and Øyvind Ihlen. 2017. “Risk, Crisis, and Social Media: A Systematic Review of Seven Years’ Research.” Nordicom Review 38 (2): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1515/nor-2017-0393.

- Rohrer, Julia M. 2018. “Thinking Clearly About Correlations and Causation: Graphical Causal Models for Observational Data.” Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science 1 (1): 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245917745629.

- Ruggiero, Thomas E. 2000. “Uses and Gratifications Theory in the 21st Century.” Mass Communication and Society 3 (1): 3–37. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327825MCS0301_02.

- Schäfer, Svenja. 2023. “Incidental News Exposure in a Digital Media Environment: A Scoping Review of Recent Research.” Annals of the International Communication Association 47 (2): 242–260. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2023.2169953.

- Slater, Michael D. 2007. “Reinforcing Spirals: The Mutual Influence of Media Selectivity and Media Effects and Their Impact on Individual Behavior and Social Identity.” Communication Theory 17 (3): 281–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00296.x.

- Stephan, Walter G., and Cookie White Stephan. 2000. “An Integrated Threat Theory of Prejudice.” In Reducing Prejudice and Discrimination, edited by Stuart Oskamp, 23–45. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Tajfel, Henri, and John C. Turner. 2004. “The Social Identity Theory of Intergroup Behavior.” In Political Psychology, edited by John T. Jost and Jim Sidanius, 276–293. New York: Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203505984-16.

- Theorin, Nora. 2022. “Different Effects on Different Immigrant Groups: Testing the Media’s Role in Triggering Perceptions of Economic, Cultural, and Security Threats From Immigration.” International Journal of Communication 16: 2477–2497.

- Valkenburg, Patti M., Irene I. van Driel, and Ine Beyens. 2022. “The Associations of Active and Passive Social Media Use with Well-Being: A Critical Scoping Review.” New Media & Society 24 (2): 530–549. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211065425.

- Valkenburg, Patti M., Jochen Peter, and Joseph B. Walther. 2016. “Media Effects: Theory and Research.” Annual Review of Psychology 67 (1): 315–338. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122414-033608.

- Wahlberg, Anders A. F., and Lennart Sjoberg. 2000. “Risk Perception and the Media.” Journal of Risk Research 3 (1): 31–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/136698700376699.

- Wei, Ran., Jichen Fan, and Jindong Leo-Liu. 2023. “Mobile Communication Research in 15 Top-Tier Journals, 2006–2020: An Updated Review of Trends, Advances, and Characteristics.” Mobile Media & Communication 11 (3): 341–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/20501579221110324.

- Wessler, Hartmut, Scott L Althaus, Chung-hong Chan, Marc Jungblut, Kasper Welbers, and Wouter van Atteveldt. 2022. “Multiperspectival Normative Assessment: The Case of Mediated Reactions to Terrorism.” Communication Theory 32 (3): 363–386. https://doi.org/10.1093/ct/qtab007

- Williamson, Harley, Suzanna Fay, and Toby Miles-Johnson. 2019. “Fear of Terrorism: Media Exposure and Subjective Fear of Attack.” Global Crime 20 (1): 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/17440572.2019.1569519.

Appendix A

Web of Science: in total, 526 results.

488 results if only including studies from 2007 to 2023.

476 results if only including articles, book chapters, early access, and proceeding papers.

459 results if only including articles in English.

315 results if only including relevant research areas.Footnote1

((TI=(‘media use’ OR ‘media consumption’ OR ‘news consumption’ OR ‘media exposure’ OR ‘news exposure’ OR ‘news media’ OR ‘news report*’ OR ‘media platform’ OR ‘social media ‘OR ‘social network*’ OR ‘online media ‘OR ‘internet’ OR ‘mobile phone*’ OR ‘social sharing’)) OR (AB=(‘media use’ OR ‘media consumption ‘OR ‘news consumption’ OR ‘media exposure’ OR ‘news exposure’ OR ‘news media’ OR ‘news report*’ OR ‘media platform’ OR ‘social media ‘OR ‘social network*’ OR ‘online media ‘OR ‘internet’ OR ‘mobile phone*’ OR ‘social sharing’)) OR (AK=(‘media use’ OR ‘media consumption ‘OR ‘news consumption’ OR ‘media exposure’ OR ‘news exposure’ OR ‘news media’ OR ‘news report*’ OR ‘social media ‘OR ‘social network*’ OR ‘online media ‘OR ‘internet’ OR ‘mobile phone*’ OR ‘social sharing’))) AND ((TI=(‘fear of crime’ OR ‘crime perception*’ OR ‘crime trend perception*’ OR ‘fear of violent crime* ‘OR ‘fear of war ‘OR ‘fear of terror’ OR ‘fear of attack*’ OR ‘fear of violence’ OR ‘fear of victimization’ OR ‘reaction* of fear’ OR ‘perceived vulnerability’ OR ‘perceived threat*’ OR ‘sense of security’ OR ‘feelings of security’)) OR (AB=(‘fear of crime’ OR ‘crime perception*’ OR ‘crime trend perception*’ OR ‘fear of violent crime* ‘OR ‘fear of war ‘OR ‘fear of terror’ OR ‘fear of attack*’ OR ‘fear of violence’ OR ‘fear of victimization’ OR ‘reaction* of fear’ OR ‘perceived vulnerability’ OR ‘perceived threat*’ OR ‘sense of security’ OR ‘feelings of security’)) OR (AK=(‘fear of crime’ OR ‘crime perception*’ OR ‘crime trend perception*’ OR ‘fear of violent crime* ‘OR ‘fear of war ‘OR ‘fear of terror’ OR ‘fear of attack*’ OR ‘fear of violence’ OR ‘fear of victimization’ OR ‘reaction* of fear’ OR ‘perceived vulnerability’ OR ‘perceived threat*’ OR ‘sense of security’ OR ‘feelings of security’)))

Scopus: in total, 784 results.

713 results if only including studies from 2007 to 2023.

684 results if only including articles, book chapters, and conference papers.

414 results if only including relevant research areas.Footnote2

404 results if only including articles in English.

TITLE-ABS-KEY(‘media consumption’ OR ‘news consumption’ OR ‘media exposure’ OR ‘news exposure’ OR ‘news media’ OR ‘news report*’ OR ‘media use’ OR ‘social media’ OR ‘social network*’ OR ‘online media’ OR ‘internet’ OR ‘mobile phone*’ OR ‘social sharing’) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(‘fear of crime’ OR ‘crime perception*’ OR ‘crime trend perception*’ OR ‘fear of violent crime*’ OR ‘fear of war’ OR ‘fear of terror’ OR ‘fear of attack*’ OR ‘fear of violence’ OR ‘fear of victimization’ OR ‘reaction* of fear’ OR ‘perceived vulnerability’ OR ‘perceived threat*’ OR ‘sense of security’ OR ‘feelings of security’) AND PUBYEAR < 2024 AND PUBYEAR > 2006 AND PUBYEAR < 2024 AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, ‘ar’) OR LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, ‘cp’) OR LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE, ‘ch’)) AND (EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, ‘MEDI’) OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, ‘NURS’) OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, ‘MATH’) OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, ‘AGRI’) OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, ‘ENER’) OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, ‘PHAR’) OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, ‘BIOC’) OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, ‘PHYS’) OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, ‘IMMU’) OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, ‘EART’) OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, ‘HEAL’) OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, ‘MATE’) OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, ‘NEUR’) OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, ‘VETE’) OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, ‘CHEM’) OR EXCLUDE (SUBJAREA, ‘CENG’)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE, ‘English’)