ABSTRACT

Migration, global mobility and language learning are well established as independent and interrelated fields of study. With nearly one fifth of children in British primary schools classed as speakers of English as an Additional Language (EAL), there remains much to explore in the field of heritage language research. This paper reports on a survey of 212 heritage language families and ten family interviews with families who, though not living in isolation, are not part of large, well-established, local communities. The study reported here explores the families’ attitudes towards heritage language development, and their efforts to maintain, support or develop the heritage language in their families. The paper puts forward an original framework which can be used to conceptualise how different uses and perceptions of the heritage language use may be linked to identity, and concludes with recommendations on how relatively isolated heritage language families and their small community networks may be better supported to enable children more fully to benefit from the advantages of their multilingual, multicultural capital.

Introduction

Migration, global mobility and language learning are well established independent and interrelated fields of study (Blackledge and Creese Citation2010; Norton Citation2013). Nevertheless, current political and economic climates give new rise to concepts such as ‘super-diversity’ (Vertovec Citation2007), with, for example, the 2016 UK EU Referendum and the triggering of Article 50 further illuminating issues of belonging, heritage language, and identity. With nearly one in five (19.4%) children in the English primary school system being classed as a speaker of English as an additional language (Tinsley and Board Citation2016), heritage language research will need to grow in order to engage with new questions of a reshaped European Union and increasingly diverse multilingual communities. Whilst there exists a body of research focussing on heritage language speakers in comparatively large communities in the England (see e.g. Al-Azami et al. Citation2010; Kenner et al. Citation2008; Sneddon Citation2000), as well as on translanguaging and spatial multilingualism in specific public spaces (see e.g. Blackledge and Creese Citation2017; Blackledge, Creese, and Hu Citation2016), the experiences in the home of families who are not a part of identified languages communities are less well documented. In order to address this gap, this paper reports on a study which asked:

How do isolated heritage language families living in England experience heritage language development, both within the family, and in relation to their extended communities?

What resources and levels of support do heritage language families seek to provide for their young children?

Terminology

The terminology surrounding language learning is multi-faceted and often contested.

While the term ‘multilingualism’ is long-standing in the literature (see e.g. Blackledge and Creese Citation2010), authors such as Marshall and Moore (Citation2013) argue for a differentiation between the individual and the wider social context. They argue for the term ‘plurilingualism’ as ‘the distinct aspects of individual repertoires and agency’ (Marshall and Moore Citation2013, 474), a more appropriate definition that ‘multilingualism’, which they argue refers to ‘broader social contexts’ (ibid.). Similarly, the Council of Europe (Citation2001) refers to plurilingualism as part of a person’s ‘linguistic and cultural biography’ (p. 133), and furthermore links plurilingualism expressly to the formation of identity.

For the purposes of this paper, heritage language is defined as the ‘intergenerational transmission of a language’ (Baker Citation2011, 49), i.e. a language that filters through the family. Gollan, Starr, and Ferreira (Citation2015) point out that successful heritage language development may rely on more than just the immediate family, citing the importance of a community of speakers. Exploring the stories of families who do not necessarily have access to such a community is the purpose of this paper. Furthermore, Blackledge and Creese (Citation2010) problematise the notion of ‘heritage’, arguing that it is more complex than simply a ‘passing on’ of language or cultural values, and is instead linked to complex notions of identity as well as language, which fits well with the research presented here. In line with their argument, this paper critically reports original research involving parents and children, sharing their views and experiences, leading to a framework for conceptualising heritage language as linked to identity. While the various heritage languages in the study undoubtedly have a different status in society (Seals and Peyton Citation2016), the point of this exploratory research was to understand better the variety of emotional attachments to language and attempts and reasons for involving children in its learning, forming the basis for potential future research.

This paper discusses the literature around heritage language and identity before exploring previous studies of heritage language development in the home. To contextualise the socio-political context, the paper then briefly outlines the role of heritage language learning in the English state system. Literacy and policy documents form the background for a rigorous, empirical study with 212 heritage language families living in England, before suggesting an original conceptual framework of heritage language as linked to identity.

Heritage language and identity

The links between identity and language learning have been explored by numerous authors (Blackledge and Creese Citation2010; Block Citation2009; Norton Citation2013). Both Block and Norton approached the subject with first-generation language learners, Norton in particular addressed the notions of investment, identity and imagined communities (Norton, ibid). These notions centre around the concept of ‘becoming’ or ‘moving towards’ an identity that is envisaged by the language learner themselves. In second-language acquisition, Gardner and Lambert’s (Citation1959) notion of ‘integrativeness’ has long dominated the academic narrative around language learners’ selves and identity construction. In more recent years, however, researchers have problematised the notion of a language ‘belonging’ to one specific culture (see e.g. Davidson, Guénette, and Simard Citation2016). Czubinska (Citation2017) explores the psychological and psychoanalytical implications attached to maintaining one’s home language, and considers the development of ‘pre- and post-migration selves’. She describes the confusion in immigrant families, where children may not be aware of the emotional attachment and links to identity the home language may hold for the parent.

A parent’s first language (the heritage language) may play a different role for the children. As Blackledge and Creese (Citation2010) point out, ‘heritage’ may become a site at which identities are contested, rather than imposed unproblematically’ (p. 166). Such contestation can invite friction. Some parents expect their children to learn the heritage language to ‘maintain’ a cultural or ethnic identity, or ‘connect’ with certain cultural values (Lee Citation2002). Mu (Citation2014) links heritage language learning to both Norton’s investment theory (Norton Citation2013) and Bourdieu’s concept of capital (Bourdieu Citation1986). Bourdieu (Citation2000) argues that ‘only when the heritage has taken over the inheritor can the inheritor take over the inheritance’ (p. 152), and that there is ‘nothing inevitable about it’ (p. 152). Although language and cultural values may be inextricably linked, they are experienced individually and separately by different family members, and need to be explored as relational, rather than individually distinct, aspects of identity formation.

Chinese families in Mu’s (Citation2014) study expressed their view that the maintenance of the Chinese language was something which maintained cultural and social links, and had potential financial impact, in job prospects and enhanced mobility. Thus, the heritage language learners find themselves with an inherited multicultural identity through birth, yet they may experience a monolingual, monocultural identity. Their efforts – or their parents’ efforts, are less about ‘becoming’, and more about ‘remaining’ or ‘returning’– holding on to language, culture and customs. However, not all young heritage language learners appreciate the heritage language while they are learning it, and only consider it part of their identity retrospectively (Mu and Dooley Citation2015). Similarly, not all parents attach the same value to their own language, as evidenced by Gogonas and Kirsch (Citation2016), whose participants had varying views regarding the maintenance of Greek within a trilingual (German, French, English) community context in Luxembourg.

In the field of heritage language education, younger children’s perceptions remain a gap in the literature. Melo-Pfeifer (Citation2015) suggests that this may be because of difficulties in data collection from younger age groups, something this study seeks to address.

Supporting heritage languages at home

For over a century, researchers have been interested in how families seek to support multiple languages (Ronjat Citation1913). Who speaks which language at home can have emotional consequences, where the heritage language parent may feel obliged to take on the role of a language teacher, rather than a parent (Okita Citation2002). Several families in the study adopted a strategy where one parent might use both the heritage language and English (De Houwer Citation2006; Yamamoto Citation2001). Song (Citation2016) describes how families use both Korean and American to facilitate children’s meaning-making process, and how children may prefer certain words in one language, even though they know them in both. Gregory (Citation1998), in the context of literacy development, points to the important role siblings may have in brokering development, although, in a heritage language context, siblings are often responsible for facilitating the environmental or school language, rather than the heritage language (see e.g. Guardado Citation2002).

Families utilise multiple resources to support heritage language development, including books (Cho and Krashen Citation2000), technology, such as television, DVDs, social networking (Szecsi and Szilagyi Citation2012), and community schools (Mu and Dooley Citation2015). The use of such resources both facilitates heritage language and literacy development, and, depending on the resources, helps to maintain links with family abroad, or assists in exploring cultural roots.

Supporting heritage language speakers in primary schools

The annual review of language education trends in UK by Tinsley and Board (Citation2016) focused on home languages for the first time in 2016. While some school staff spoke a community language, most focused on encouraging a multicultural school community (rather than providing specific lessons or support for community languages). Some schools cited lack of resources and expertise, or did not see supporting the home language as the school’s responsibility. Tinsley and Board (ibid) found ‘three quarters of schools with high levels of EAL pupils having no involvement in [the teaching of community languages] at all’ (p. 67). Tinsley and Board’s study illuminates the fragmented, unstable provision and support for heritage languages in England, which relies on enthusiastic and informed individuals. For children and their families, home and school may occupy distinct language spheres.

Kenner et al. (Citation2008) describe a study of primary school-aged children from a Bangladeshi background, some of whom accessed the curriculum in Bengali and English, with after-school lessons in Bengali. Some children came to view Bengali as part of their identity, and their learning, understanding, and knowledge were enhanced as a result. Such opportunities are missed when bilingual children are viewed through a deficit-lens, focusing only on increasing the level of English to the point where curriculum learning criteria are met. As in Kenner’s study, the children of the families interviewed for this study spoke fluent English, working at the national curriculum’s expected level or ahead of it. They are often invisible as heritage language speakers who do not necessarily showcase their heritage language skills at school, thus risking a negative influence on their constructed identities as plurilingual, pluricultural individuals.

Methodology

This study, although not necessarily small-scale, is nevertheless intended as exploratory, as heritage language families’ lives are particularly complex. As such, the families are not intended to be representative of their respective country, language, or family composition; however, gathering views from a wide variety of cultural and linguistic contexts drew out different views and ideas. The research design therefore remains interpretive, despite the quantitative element of the study, which was used to explore key themes and ideas as the basis for family interviews.

Buckingham (Citation2008) states that ‘identity is an ambiguous and slippery term’ (p. 1). In a ‘super-diverse’ society (Vertovec Citation2007), a study on identity therefore needs to acknowledge a complexity of contexts. However, while Goffman (Citation1990) suggests that this may lead to a fragmented identity or multiple selves, Giddens (Citation1991) argues that people have a ‘distinctive self-identity which positively incorporates elements from different settings into an integrated narrative’ (p. 190). This study explores how family narratives around language, and attitudes towards language, may link to identity. Caduri (Citation2013) considers the importance of ‘truth’ in qualitative research which is largely dependent on narratives, and argues that there is an epistemic entitlement to a claim to knowledge, since, even though it may be impossible to verify the ‘truth’ of statements that are part of a subjective experience, the way people remember and choose to recount these experiences is nevertheless of interest. This study therefore acknowledges that families may have chosen – either consciously or subconsciously – what to share in interviews (Caduri Citation2013); however, the interviews were designed to explore experiences from the viewpoint of numerous family members, allowing for triangulation and lending credibility to the data.

The study gathered questionnaire data from 212 families and in depth interviews with ten families. The questionnaire was developed online, and piloted with two heritage language parents who were personal contacts. Subsequently, the questionnaire was initially shared via online fora and social media groups focusing on bilingual or multilingual parenting, and from there shared freely by some of the group’s participants within their own contexts. These shares were out of my control, and, independently of data collected, shed some light on the ways in which heritage language families use social media to connect to other like-minded people. The online shares were responsible, for example, for the strong representation of Swedish families (13 out of 212), since a participant shared the questionnaire in a group aimed at Swedish parents in Britain. For this exploratory study, it was deemed important to identify a sample group of participants who were motivated and interested in sharing their views and experiences in detail in long, text-based comments in the questionnaire, which ensured the data were rich and meaningful.

Questionnaire

The study adopted a mixed-method approach, an online questionnaire which gathered qualitative and quantitative data on families’ ideas, ideals, perceptions and practices surrounding their heritage languages at home and school, several of which linked back to identity construction. Some questions were answered by a Likert Scale or multiple choice, others were open-ended, encouraging families to share more detail about their situation, outlining language skills, how language is used in the home, who speaks which language with whom, etc. A specific sub-set of questions on technology use forms the basis for a different paper (Little, in preparation). The majority of respondents lived in England, with a small number from other countries. To reduce ambiguity in the findings, responses from families outside England were excluded, since participants living in England would share the same geo-political context and the children experience a similar education system. Therefore, children in the study would have started school aged 5, with many having undergone the ‘Reception’ year from age 4, in accordance with the English school system. Overall, 268 questionnaire responses were submitted, removal of double entries, empty entries and responses from other countries left 212 responses available for analysis.

Interviews

The online questionnaire included the option to volunteer to be interviewed. For the purposes of this study, volunteers with children of primary school age (age 5–11) were selected. The thirteen families fitting these criteria were contacted, resulting in ten interviews, all conducted via Skype, recorded, and transcribed in full. Seitz (Citation2016) points out that in-depth connections may be difficult to achieve via Skype, especially in relation to complex or emotional questions. This is not necessarily true for heritage language families, who may well be familiar with the technology. For nine out of ten families interviewed, Skype was familiar to both adults and children, typically used to maintain contact with family members living abroad. In all interviews, the mother was present, in seven interviews, children were present, and in two interviews, fathers were present. The actual interviews lasted approximately 45 min per family, although discussion sometimes continued beyond the official interview schedule, particularly where parents asked for further details about research in the field, or asked for resource ideas. These conversations have not been included in the analysis, but were viewed as an ethical way to recognise the time participants spent on the study (Bagley, Reynolds, and Nelson Citation2007).

Data analysis

The data comprise quantitative responses from 212 questionnaires, text responses from open-ended questionnaire items, and ten family interviews. Analytical tools were designed to support a structured coding framework, adding rigour through a systematic approach, while remaining open to unanticipated findings from qualitative data. Developing a robust coding framework can be the most time consuming part of a study (Adair and Pastori Citation2011), but is especially important when the study is large-scale, or, in this case, intended to form the basis for further studies. Data collection mirrored the areas of the literature review, exploring the families’ experiences of heritage language learning at home and at school, focusing on resources and the interrelationship of these factors in relation to identity. Emotional and pragmatic attitudes were identified. Likert scales in the questionnaire allowed for ranking, where families indicated how important certain aspects were to them. This facilitated coding onto a scale, ranging from essential to peripheral. Text-based comments allowed for detailed responses to explain family choices, and identify additional sub-themes within the areas of home, school and identity. In the discussion of findings below, quantitative questionnaire data are given in percentages as a means to provide background information, and to plot the qualitative responses against the larger overall sample, thus triangulating the findings. Quotes are provided verbatim, leaving intact any minor grammatical or vocabulary-related inconsistencies, so as to accurately represent the level of English among participants, and maintain their original voice in the research. Any names provided are pseudonyms.

Ethical considerations

An explanatory paragraph introduced the web-based questionnaire by outlining the research and intended publication outcomes. It was clearly stated that completion of the questionnaire implied consent for data to be used in the study. Information sheets and consent forms, using language and imagery appropriate for young children and non-native speakers were used for family interviews. Participants were encouraged to ask further questions and discuss any concerns when interviewed. The youngest child actively participating in interviews was seven years old, although some younger children were present but did not actively participate.

Parents and children were actively encouraged to engage in a dialogue where each other’s perceptions and attitudes might be challenged, presenting a particular ethical concern. Beauchamp and Childress (Citation2001) suggest that autonomy, ‘free from both controlling interference by others and from limitations’ (p. 58), is a vital ethical principle to be observed. This presents a challenge when parents may exert an influence; parents in two families suggested prior to the interviews that their children might not ‘say what you want to hear’. The importance of free discussion was stressed in the information sheet which highlighted the importance of genuine and non-fabricated experiences, and actively encouraged parents to give their children the space to share their views.

Discussion of findings

Family composition

Of the 212 families, 85% were in households with two parents present. In 38% of all families, both parents had a first language other than English – in 12% of all families, this was the same language, in 26%, both parents spoke different first languages. Forty-three percent of all families had two parents, one of whom was an English native speaker – the largest group of respondents. In 4% of the families, both parents spoke English as their first language – a number equal to the single parent households with English as a first language (4%). In both these groups, the heritage language was supported to communicate with grandparents. In 9% of families, a single parent spoke a first language other than English, whereas in 6% of families, a single parent identified as speaking English as a first language, but still supported a heritage language with the children.

The languages spoken by the participating families in this exploratory study were diverse, with over 40 languages spoken across 212 families. Seventy families (33%) spoke two or more non-English languages in the home, to varying degrees. The largest language groups represented Western European languages (e.g. 13 Swedish-speaking families, 20 German-speaking families), with a robust representation of Eastern European languages (e.g. 6 Polish-speaking families, 4 Hungarian, 4 Czech). Mandarin Chinese (6 families), Cantonese (3 families) and Urdu (4 families) were the largest Asian language groups represented. Some families resisted identifying as being part of a certain ‘language group’, especially French-speaking families, which ranged in origin from several African countries to the Caribbean, Canada, and France. This is important when we consider links between language and identity, and ties in with criticism of Gardner and Lambert’s (Citation1959) concept of ‘integrativeness’ in migration and language learning (Davidson, Guénette, and Simard Citation2016).

Parental descriptions of their heritage-language speaking children

While the ages of children varied from two months to 21 years, the vast majority of families had at least one child of compulsory education age for England (age 5–18), and most had at least one child aged between 5 and 11 years (the age of compulsory primary schooling in England). In a free-text response, parents shared information about the children in their household, and their knowledge of, or attitude towards, the heritage language(s) across listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Oral/aural skills were considered better developed in most children than reading and writing, and listening, reading (i.e. receptive skills) were considered better developed than speaking and writing:

Son, 10 confident speaker although makes grammatical errors. Slow but confident in reading and writing. Son, 8 understands the language but avoids using it if he can. Finnish spelling follows English pattern. Does not want to read Finnish. Daughter,3 speaks English only to all the family members but happily speaks basic Finnish to an aupair and wider family members.

Son, 14 years old, fluent Urdu speaker. Listening is good but struggle in reading and writing. Love to speak Urdu with family and grandparents. Daughter, 10 years old, fluent Urdu speaker, listening is good but struggle in reading and writing. Love to speak Urdu with family and grandparents. Son 5 years old. Can speak short sentences and can read Roman Urdu. Listening is good but struggle with Urdu writing. (Free-text questionnaire responses)

Parents’ desired language outcomes for children

Parents were asked how proficient they were hoping their child would become in the heritage language – since the children in the study were still rather young, this was viewed as an indicator of parental attitude and determination in relation to the heritage language. Responses were rated on a Likert Scale, with options (see ) decreasing in levels of control. The final option ‘I will be led by my child in this’, was included to gauge whether parents were willing to completely place the choice of heritage language development in their children’s hands – and at what level of language development this would occur (Mu Citation2014). All four skills were presented at several levels, ranging from basic/minimum, to advanced, with a final option suggesting fully equal status of both (or all) languages.

Table 1. Parents’ desired language outcomes for their children.

Parents’ expectations and desires largely triangulated and confirmed the descriptions they had already given of their children. Basic verbal communication skills were marked as ‘absolute minimum’ by 58% of families, with only 3% stating that this would be child-led. The higher the skills set, the more parents were willing to relinquish control – while 12% of parents stated it as an ‘absolute minimum’ that their child will have advanced writing skills in the heritage language, 18% stated that they would be led by their children. Of particular interest is the final category – fully equal status of both languages. This notion of balanced bilingualism is problematised by Baker (Citation2011), who refers to it as an ‘idealised concept’ (p. 8) and points out that this may mean a low equal status of both languages. Nevertheless, 10.3% of parents view this as the ‘absolute minimum’ for their children. However, the category did also feature the highest child-led percentage (30.6%). Since each individual language had only a small number of representatives, the data were not compared across groups – this may form the basis for a larger and more fully quantitative study at a later date.

The impact of compulsory (English) schooling on the heritage language

The question of schooling was originally intended to be picked up in interviews only, to explore fully the relationship between home and school. Therefore, no questionnaire items specifically asked about school. However, fifteen questionnaire respondents mentioned school as part of an invitation to submit additional comments; six highlighted school as a way to differentiate spheres of language use, and the remaining nine focused specifically on the influence school had on their children’s language development, both in English and the heritage language. In all cases, the use of English had increased greatly, with some parents reporting their children’s reluctance to use the heritage language after a few months at school.

since starting school, she speaks less German than she used to do (About daughter, 7)

After entering school, she is dominant in English and began to lose conversation skills in Chinese. (About daughter, 13)

He [3 years old] started preschool a few weeks ago and his level of proficiency increased immediately. We do not use English at home but he speaks in sentences now maybe at a level of a 2 years old. He understands much more than he speaks, although he says he does not want to learn and speak English more because he has nothing more to tell to his teachers and peers. While he is happy to chat in Hungarian with us.

The school’s attitude towards the heritage language was discussed in all family interviews. Overall, families echoed Tinsley and Board’s (Citation2016) findings, reporting that schools either encouraged a generic interest in multiculturalism, or were ambivalent, with the heritage language not featuring at all in communications with the school. One mother commented

They [the school] mainly focus on English. My daughter just speaks and tries to teach them […] how to count in Japanese and they don’t stop her doing things like that. But at the same time they don’t encourage her. Japanese Mother of 5-year-old girl, interview

Since this study focuses explicitly on more isolated heritage language families, only one mother stated that there were children speaking the same heritage language at her child’s school, and English remained the language of communication, again supporting Tinsley and Board’s (ibid) notion that children may develop distinct spheres of language in home and school:

And even at […] his current state school, there are some Chinese kids too that I know they speak Chinese at home but when they’re playing together I’ll encourage them ‘speak Chinese, speak Chinese’ but no, they just switch back to English because that’s what they’re used to, it’s the playground language. Malaysian mother of 5-year-old boy, interview

Family efforts to support the heritage language

The study focused explicitly on families with no strong specific language community, in order to find out the lengths to which these mostly isolated families went to in order to support the heritage language, and to address this gap in the literature. One mother explained:

I was always keen to meet other Germans [for my son to talk to] and I never did, I even asked people in the street and it usually ended up being a tourist! German mother, interview

Over 20% of families in the questionnaire reported making particular efforts to support the heritage language, including: self-organised playgroups, get-togethers with other families, a language-specific football club, evening classes, Saturday schools, au pairs, parent-taught lessons, scheduled Skype sessions, websites, apps and online games, resources purchased both online and in-country, long holidays and trips to the heritage-language country. This paints a picture already familiar from other studies (Guardado Citation2002), but expanding on the use of technology, which will be specifically explored in a separate paper (Little, in preparation).

Use of heritage language resources

Resources used by families can be described as belonging to three categories

Entertainment resources for native speakers of the heritage language

Learning resources for native speakers of the heritage language (e.g. early learning activity books, school-start books, etc.)

Foreign language learning materials (mainly websites and YouTube videos)

Resources used by families varied, but followed a similar pattern overall. Books were used on a daily or nearly daily basis by 64% of families, with participants describing favourite finds, bulk-buying during trips, or ordering online.

My husband, and parents, and friends, when they go to Russia, we ask them to bring Russian books. Even when they exist in English, we ask for Russian translations. Russian-speaking mother of 6-year-old boy, interview

Many parents said they used all three types of resources to facilitate the heritage language, with foreign language learning materials being largely in the form of websites and YouTube videos (Szecsi and Szilagyi Citation2012), although at least one family highlighted a specific category of resources: ‘I buy [books] from China, they are targeted to overseas children who are obviously learning Chinese as a second language’ (Malaysian mother who has chosen Chinese as the heritage language for her 5-year-old boy). Some resources (such as certain computer games or apps) were used mainly for motivational reasons. One mother explained:

[S]he’s quite tech savvy […], if there’s any way I can hook her interest, word recognition in Hindi you know, learning the alphabet, I’ll definitely do my best. Indian mother of 6-year-old girl, interview

I do always encourage him, like he currently got into Minecraft and he wanted You Tube videos about it and I said ‘let’s have a look if there are some German You Tube videos’. But I think if left alone he would naturally go more for the English ones. German mother of 8-year-old boy, interview

Inter-family tensions

Some families reported tensions in relation to the heritage language, and rifts existed between parents and between parents and children, as this interview extract between a Mother and son illustrates:.

But when he was 6 or 7 I forced him to speak French, I would tell him ‘I’m not speaking English to you’. ‘Of course you can, I know you can speak English’, and there’s been a little rebellion and even every so often it happens as well when I just refuse to speak to Lucas in English – and I don’t know whether it’s good or not. And I think, yeah, it’s me who wants Lucas to speak French, I don’t think Lucas really wants to.

Here we go again!

Yes, here we go.French mother and 9-year-old Lucas, interview

This exchange is illustrative of the attitude described by Mu and Dooley (Citation2015), with heritage language learners perceiving that they had to work harder than their monolingual peers. Lucas is, effectively, contesting the notion of a ‘heritage identity’ (Blackledge and Creese Citation2010). As Bourdieu (Citation2000) points out, heritage is not inevitable, it is a complex cycle of interaction between the heritage and the inheritor, which may or may not lead to identification with that heritage, absorbing it into the multifaceted identity proposed by Giddens (Citation1991). Asked how he felt about growing up with two languages, Lucas responded: ‘I don’t like it at all because I’m always getting angry when I don’t know how to say something. And one day I’m like AARGH and I get into a rage’. Another boy (aged 8) differentiated between himself (growing up bilingual English/German) and ‘proper German children’. All interviewed parents were very competent English speakers. In such circumstances, especially when the other parent does not speak the heritage language, the need to maintain the heritage language moves from pragmatic to emotional, and may be linked with the notion of a pre- and post-migration self, as explored by Czubinska (Citation2017), with parents seeking to create links to they consider a vital part of their own identity (Norton Citation2013). Eighty-one percent of parents responding to the questionnaire considered it as ‘very important’ or ‘essential’ for their children to learn the heritage language ‘because [they] cannot imagine [their] children not speaking the heritage language’. While other reasons given were career-related (increased job prospects, 55%) and family oriented (communicating with family members abroad, 86%), the innate expressed desire for the child to speak the language of the parent shows a close emotional link to identity formation.

Not all families, however, subscribed to emotional links to the heritage identity, mirroring findings by Gogonas and Kirsch (Citation2016). In families who spoke multiple languages at home, the question as to which languages are passed on to the children was decided through a complex interrelationship between access to the language, parental language skills, links to identity construction, and perceived usefulness. One mother explained why she chose to teach her son Chinese (which only she speaks), rather than Malay (which both parents speak):

So our first language, so Malay is the national language in Malaysia […], but basically we find that it’s not a very useful language out of Malaysia. So English, being a good language, I think that’s my … actually that’s my husband’s primary language [at home], whereas for me at home I speak both Chinese and English. Malaysian mother of 5-year-old boy, interview

In this case, English is the family language when both parents are present, with Chinese spoken between mother and son. Malay, though spoken by both parents, is not used at all in the family, a decision followed through by the mother, but not fully supported by the father, as became clear in the interview, when the father made derogatory comments about Chinese. This is reminiscent of Norton’s (Citation2013) notion of investment – although in this case, it is a lack of investment for the heritage language, in favour of a language spoken by just one parent, but promising greater ‘capital’ (Bourdieu Citation1986). This is a pragmatic attitude in an area where emotion often reigns, inhibiting the affective engagement with identity development (Venables et al. Citation2014).

Four parents explained that ‘life got in the way’ of good intentions, with either the children, or the parents (or both) finding that there simply was not enough time to dedicate to the heritage language. One mother said of her English-native husband

When we first got together, bless him, he even went out and bought a Hindi-English phrase book and he had a little notebook and he was making notes and I was actively helping him. But you know, then I don’t know what happening, life gets in the way and he does get busy and you have to consciously allow time for that to develop and build, and, yes, it just got lost in the system. Indian mother of 6-year-old girl, interview

Well because we lived together for a long time before having the kids English was our language, and changing that now to something else is really, really strange. German mother of 8-year-old son, interview

It is possible that the sudden introduction of the heritage language was confusing for partners, too, changing the perception they had of their partners, an area worthy of further exploration.

Conclusion – a conceptual framework of heritage language identities

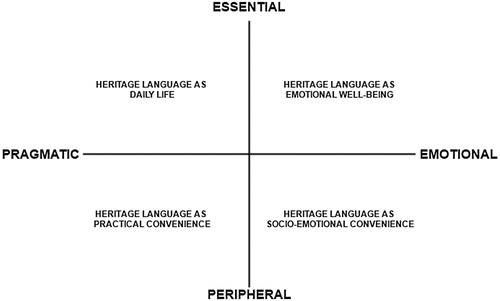

This study highlights the complex motivations for heritage language learning in which can be considered in terms of a conceptual framework of heritage language identities (see ).

Engagement with the heritage language is often influenced by how each parent perceives their place – and those of their children – within the conceptual framework. None of the families in this study fell into the essential/pragmatic category, where the heritage language is necessary for survival, such as children translating for parents. Each learner’s and family’s position on the framework will influence their investment (Norton Citation2013), and will further be influenced by their social, academic and cultural capital (Bourdieu Citation1986).

Throughout their journey, family members may move from one place to another depending on their relationship with and use of the heritage language; and it is important that members of the family are able to communicate their concerns and expectations. Norton’s (Citation2013) first-generation immigrants were moving towards the target language as an investment, in a unilateral pull that combined societal expectations, job prospects, and personal desire. This is also the case for some parents in this study. All but one of the parents interviewed moved to the UK as an education or economic migrant (one mother was 15 when she arrived in the UK with her parents). Therefore, the parents in the study had a vested interest in studying, working and living in England. Isolated from large heritage language communities, their interest coincided with a societal pull of outside influences, all moving in the same direction, with firm anchors (i.e. language competence in the first language) in place.

For heritage language learners, this ‘pull’ is not unidirectional – while society draws them heavily towards English language and culture, through school, access to media, environmental print, etc., Families in the study went to extraordinary lengths to maintain and develop the heritage language against, or in spite of, this ‘pull’. However, at primary age, children may struggle to identify with a pragmatic need to learn the heritage language (e.g. future employment opportunities), and if both parents speak very good English, they may not feel an emotional need either, even if the parent does.

Therefore, friction can occur when family members view their position on the framework separately – a child in the PP quadrant (peripheral/pragmatic) who views the heritage language as only peripherally convenient for practical reasons (such as a fuzzy notion of potential future travel) will struggle to understand the deep emotional need of a parent in the EE quadrant (essential/emotional). Their position will be further influenced by external circumstances – school, access to resources, work pressures and family finances. This may mean that heritage language families occupy two spaces on the spectrum at once – an ‘idealistic’ space – in relation to their attitudes and motivations, and a ‘realistic’ space in relation to finance, support, school, resources and time. A family might have an ‘essential/emotional’ attitude to their heritage language(s), yet due to circumstance may adopt a ‘pragmatic/peripheral’ one in terms of actual engagement, a friction which may, long-term, lead to emotional distress and in children forming an identity based on the ‘realistic’ space, unaware of and unable to engage with the ‘idealistic’ space parents may try to hold on to.

Several mothers interviewed in this study occupied the EE quadrant (essential/emotional) of the framework. For them, the heritage language presents an essential aspect of their identity, which they seek to pass on to their children, and which impacts on emotional health and well-being. However, examples of friction shared in this article illustrate that neither children nor partners necessarily share the same quadrant, once again echoing Bourdieu’s (Citation2000) warning that links between heritage and identity are not straightforward, and not uncontested (Blackledge and Creese Citation2010). Examples of peripheral/emotional families may support the heritage language to connect with extended family, allowing their children to feel more comfortable during visits to the country where the heritage language is spoken, or for other emotional reasons, which do not necessarily link directly to their well-being. Peripheral/pragmatic families are more likely to support the heritage language for reasons such as career prospects or social mobility, without strong emotional ties to the language itself. If there are no strong emotional or pragmatic needs present, this quadrant may particularly come into play where families combine multiple languages, and relate directly to the choices they make in relation to which language to support in the home, although further research is needed to fully understand these complexities.

Limitations of the study

The study achieved a good level of response from the target participant group, yet no study can claim to provide a comprehensive picture of the situation of heritage language families in an entire country. Due to the open distribution of the questionnaire, it is not possible to claim that the study sample is representative across the full socio-economic spectrum. The sample was self-selective, and all participants had both the relevant English language skills and the technical skills to navigate the questionnaire. Future research, exploring views of specific language or cultural groups, including those of families where English is not spoken to a high level, and with a broader spread across socio-economic groups, would help augment the picture of heritage language families in the UK. Such studies may need to be conducted using face-to-face methods, to ensure a representative spread. Despite these limitations, the study provides original and detailed insights into the question of how isolated heritage language families living in England experience heritage language development, and these are significant to the field both in terms of policy and practice.

Recommendations and future research

Families’ motives and emotions around their heritage languages

Families reported that they actively facilitated their children’s heritage language learning, although parents’ reasons for wanting their children to inherit their languages were rarely discussed within families. While Essential Pragmatic reasons for supporting and maintaining the heritage language will be apparent to children whose parents have a limited command of English, Essential Emotional reasons may be less well understood by children, especially is parents are highly competent users of English. This may make them more likely to question why the heritage language is important. At the age most participating children were at (early primary), economic advantages were not relevant to children, the only child who mentioned it (9-year-old French/British Lucas) acknowledged the potential advantages, but was also the most outspoken in his dislike of the heritage language. In this case, actively discussing emotions and motivations may help parents and children understand their attitudes towards the heritage language, and may also help professionals working with heritage language families to gain a better understanding of the issues and emotions involved. Three families reported that participation in the research had opened up new avenues for communication about the heritage language among the family members.

The conceptual framework is derived from the study reported here and as such is an original contribution to the field. A further study is now needed, with a sample of languages, parental language skills, education background, and socio-economic background, to explore all four quadrants of the framework.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes on contributor

Sabine Little is a lecturer in languages education at the University of Sheffield. Her main research interests lie in the socio-cultural and socio-political complexities surrounding constructs of identity in heritage language families.

ORCID

Sabine Little http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9902-0217

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adair, J. Keys, and G. Pastori. 2011. “Developing Qualitative Coding Frameworks for Educational Research: Immigration, Education and the Children Crossing Borders Project.” International Journal of Research & Method in Education 34 (1): 31–47. doi:10.1080/1743727X.2011.552310.

- Al-Azami, S., C. Kenner, M. Ruby, and E. Gregory. 2010. “Transliteration as a Bridge to Learning for Bilingual Children.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 13 (6): 683–700. doi:10.1080/13670050903406335.

- Bagley, S. J., W. W. Reynolds, and R. M. Nelson. 2007. “Is a ‘Wage-payment’ Model for Research Participation Appropriate for Children?” Pediatrics 119 (1): 46–51. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1813

- Baker, C. 2011. Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. 5th ed. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Beauchamp, T., and J. Childress. 2001. Principles of Biomedical Ethics. 5th edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Blackledge, A., and A. Creese. 2010. Multilingualism: A Critical Perspective. London: Continuum.

- Blackledge, A., and A. Creese. 2017. “Translanguaging and the Body.” International Journal of Multilingualism. doi:10.1080/14790718.2017.1315809.

- Blackledge, A., A. Creese, and R. Hu. 2016. “The Structure of Everyday Narrative in a City Market: An Ethnopoetics Approach.” Journal of Sociolinguistics 20 (5): 654–676. doi:10.1111/josl.12213.

- Block, D. 2009. Second Language Identities. London: Bloomsbury.

- Bourdieu, P. 1986. “Forms of Capital.” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by John G. Richardson, 241–258. New York: Greenwood Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 2000. Pascalian Meditations. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Buckingham, D. 2008. The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning, 1–24. Cambridge, Massachussetts: MIT Press. doi:10.1162/dmal.9780262524834.001.

- Caduri, G. 2013. “On the Epistemology of Narrative Research in Education.” Journal of Philosophy of Education 47 (1): 37–52. doi:10.1111/1467-9752.12011.

- Cho, G., and S. D. Krashen. 2000. “The Role of Voluntary Factors in Heritage Language Development: How Speakers can Develop the Heritage Language on their Own.” ITL – International Journal of Applied Linguistics 127-128: 127–140. doi: 10.1075/itl.127-128.06cho

- Council of Europe. 2001. A Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Czubinska, G. 2017. “Migration as an Unconscious Search for Identity: Some Reflections on Language, Difference and Belonging.” British Journal of Psychotherapy 33 (2): 159–176. doi:10.1111/bjp.12286.

- Davidson, T., D. Guénette, and D. Simard. 2016. “Beyond Integrativeness: A Validation of the L2 Self Model among Francophone Learners of ESL.” The Canadian Modern Language Review / Louisiana Revue Canadienne Design Langues Vivantes 72 (3): 287–311. doi: 10.3138/cmlr.2319

- De Houwer, A. 2006. “Bilingual Development in the Early Years.” In Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics, edited by K. Brown, 2nd ed., 781–787. Oxford: Elsevier.

- Gardner, R. C., and W. E. Lambert. 1959. “Motivational Variables in Second-language Acquisition.” Canadian Journal of Psychology/Revue Canadienne de Psychologie 13 (4): 266–272. http://doi.org/10.1037/h0083787.

- Giddens, A. 1991. Modernity and Self-Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

- Goffman, E. 1990. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. London: Penguin.

- Gogonas, N., and C. Kirsch. 2016. “‘In This Country My Children are Learning Two of the Most Important Languages in Europe’: Ideologies of Language as a Commodity among Greek Migrant Families in Luxembourg.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. doi:10.1080/13670050.2016.1181602.

- Gollan, T. H., J. Starr, and V. S. Ferreira. 2015. “More than Use it or Lose It: The Number-of-Speakers Effect on Heritage Language Proficiency.” Psychonomic Bulletin & Review 22 (1): 147–155. doi:10.3758/s13423-014-0649-7.

- Gregory, E. 1998. “Siblings as Mediators of Literacy in Linguistic Minority Communities.” Language and Education 12 (1): 33–54. doi:10.1080/09500789808666738.

- Guardado, M. 2002. “Loss and Maintenance of First Language Skills: Case Studies of Hispanic Families in Vancouver.” Canadian Modern Language Review/La Revue canadienne des langues vivantes 58 (3): 341–363. doi:10.3138/cmlr.58.3.341.

- Kenner, C., E. Gregory, M. Ruby, and S. Al-Azami. 2008. “Bilingual Learning for Second and Third Generation Children.” Language, Culture and Curriculum 21 (2): 120–137. doi: 10.1080/07908310802287483

- Lee, J. S. 2002. “The Korean Language in America: The Role of Cultural Identity in Heritage Language Learning.” Language, Culture and Curriculum 15 (2): 117–133. doi:10.1080/07908310208666638.

- Marshall, S., and D. Moore. 2013. “2B or Not 2B Plurilingual? Navigating Languages Literacies, and Plurilingual Competence in Postsecondary Education in Canada.” TESOL Quarterly 47 (3): 472–499. doi:10.1002/tesq.111.

- Melo-Pfeifer, S. 2015. “The Role of the Family in Heritage Language Use and Learning: Impact on Heritage Language Policies.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 18 (1): 26–44. doi:10.1080/13670050.2013.868400.

- Mu, G. M. 2014. “Learning Chinese as a Heritage Language in Australia and Beyond: The Role of Capital.” Language and Education 28 (5): 477–492. doi:10.1080/09500782.2014.908905.

- Mu, G. M., and K. Dooley. 2015. “Coming into an Inheritance: Family Support and Chinese Heritage Language Learning.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 18 (4): 501–515. doi:10.1080/13670050.2014.928258.

- Norton, B. 2013. Identity and Language Learning: Extending the Conversation. 2nd ed. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Okita, T. 2002. Invisible Work: Bilingualism, Language Choice, and Childrearing in Intermarried Families. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Ronjat, J. 1913. Le Développement du Langage Observé chez un Enfant Bilingue [The Observed Development of Language in a Bilingual Child]. Paris: H. Champion. https://archive.org/details/ledveloppement00ronjuoft.

- Seals, C. A., and J. K. Peyton. 2016. “Heritage Language Education: Valuing the Languages, Literacies, and Cultural Competencies of Immigrant Youth.” Current Issues in Language Planning 18 (1): 87–101. doi:10.1080/14664208.2016.1168690.

- Seitz, S. 2016. “Pixilated Partnerships, Overcoming Obstacles in Qualitative Interviews via Skype: a Research Note.” Qualitative Research 16 (2): 229–235. doi:10.1177/1468794115577011.

- Sneddon, R. 2000. “Language and Literacy: Children’s Experiences in Multilingual Environments.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 3 (4): 265–282. doi:10.1080/13670050008667711.

- Song, K. 2016. “‘Okay, I will Say in Korean and then in American’: Translanguaging Practices in Bilingual Homes.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy 16 (1): 84–106. doi:10.1177/1468798414566705.

- Szecsi, T., and J. Szilagyi. 2012. “Immigrant Hungarian Families’ Perceptions of New Media Technologies in the Transmission of Heritage Language and Culture.” Language, Culture and Curriculum 25 (3): 265–281. doi:10.1080/07908318.2012.722105.

- Tinsley, T., and K. Board. 2016. Language Trends 2015/16: The State of Language Learning in Primary and Secondary Schools in England. London: British Council/Education Development Trust.

- Venables, E., S. A. Eisenchlas, and A. C. Schalley. 2014. “One-Parent- One-Language (OPOL) Families: Is the Majority Language-speaking Parent Instrumental in the Minority Language Development?” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 17 (4): 429–448. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2013.816263

- Vertovec, S. 2007. “Super-diversity and its Implications.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 30 (6): 1024–1054. doi:10.1080/01419870701599465.

- Yamamoto, M. 2001. Language use in Interlingual Families: A Japanese–English Sociolinguistic Study. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.