ABSTRACT

Informed by the conceptual-analytical framework of LPP and bilingual education policy, this study addresses a unique and under-researched case of heritage language education policy for complementary Polish State Schools abroad. These are Polish governmental educational offering aimed at Polish migrants and their descendants. Data consist of two policy documents issued by Polish parliamentary and governmental authorities and are analyzed through qualitative content analysis. The specific research question is: What ideological and implementational spaces can be identified in the policy documents regarding the following six areas: academic goal; language ideology; linguistic goal; language orientation; bilingualism orientation; cultural orientation? The findings show that the policy opens up implementational and ideological spaces not only for language maintenance but also for various epistemic goals and literacy forms that create opportunities for a multifaceted personal and societal development of the students. Polish language and culture are positioned both as right and as resource, and spaces for cultural pluralism and plurilingualism emerge. Even if bilingualism and biliteracy are not explicitly expressed as goals, the policy recognizes the multiple linguistic realities of the students by assuming bilingualism, the orientation that is here called bilingualism as default. Future research directions are suggested in the conclusion.

Introduction

Heritage language education policy has received relatively little attention in the field of heritage language studies (Chik, Carreira, and Kagan Citation2017; Seals and Shah Citation2018). According to Seals and Shah (Citation2018), given the recursive relationship between planning and practice, it is crucial ‘to have an accurate understanding of the current state of affairs regarding heritage language policy around the world’ (4). The present study attempts to respond to this call.

This study is part of a project on different layers of language education policy for complementary Polish State Schools abroad (henceforth PSS)Footnote1 and focuses on two policy documents. As an educational offering from the Polish state, PSS are a defined and specific case amongst different Polish language based educational solutions aimed at Polish migrants and their descendants. PSS operate on the principle of extraterritoriality and are intended as a supplementary educational opportunity for Polish-speaking children outside Poland who are educated in the majority language in the country of residence. As a complementary or supplementary educational offer, PSS teach two subjects: (i) Polish Language (including literature) as well as Knowledge of Poland (ORPEG, January 2023), a subject that covers Polish culture, geography and history. PSS were created by the Polish state in the mid-1960s under the influence of Polish diplomats and government-contracted employees abroad who until the mid-1960s were forced to educate their children within the Soviet educational system by Russian teachers and in Russian (Kusztelak Citation2004, Citation2011). Thus, originally PSS were a way of escaping from Soviet indoctrination. PSS are a rather understudied phenomenon, even in Polish national research, compared to other forms of Polish (language) education outside Poland (e.g. Lipińska and Seretny Citation2012; Dubisz Citation2015; Łączek Citation2018). PSS are mentioned in Polish scientific publications in passing and are seldom the focus of studies (see, however, Gajdzica, Piechaczek-Ogierman, and Hruzd-Matuszczyk Citation2014; Ogrodzka-Mazur Citation2017).

Defining heritage language speakers

Heritage language (HL) speakers are people who have a recent or ancestral connection to a language that is not the dominant societal language in their current region of residence (Seals and Shah Citation2018, 3). HL speakers use their agency to identify with the HL(s) and they may be at any level of proficiency to include not actually having proficiency in the language(s) (Seals and Shah Citation2018).

Conceptual-analytical framework

My analysis of the policy documents combines heuristics and concepts from LPP and bilingual education policy. Much critical research on language education policy has righteously perceived policy as oppression, (Johnson Citation2010, Citation2013; Johnson and Freeman Citation2010; Tollefson Citation2013), but language education planning does not always mean subjugation (Hornberger and Johnson Citation2007; García Citation2009; Johnson Citation2011; Baker and Wright Citation2017); policies involve also overt active governmental planning aimed at the empowerment of a language and allocate resources to this aim (Tsui and Tollefson Citation2004; Wiley Citation2015).

For studying policy openings, Hornberger (Citation2002) introduced the concepts of implementational and ideological spaces that were clarified in additional publications (Hornberger Citation2005, Citation2020; Hornberger and Johnson Citation2007). These concepts, together with an analytical tool presented later in , are central to the present study. Hornberger (Citation2002) says that ‘multilingual language policies are essentially about opening up ideological and implementational space in the environment for as many languages as possible […] to evolve and flourish rather than dwindle and disappear’ (30). Hornberger (Citation2002, Citation2005, Citation2020) points out that, for instance, in post-apartheid South Africa, explicit language education policy might offer ideological and implementational spaces for multilingualism and bilingual education (cf. also Chick Citation2002; Alexander Citation2003). Ideological spaces created by language and education policies can be seen as opening implementational spaces at classroom and community levels, but implementational spaces can also promote the opening of ideological ones regarding also other aspects than multilingualism and bilingual education (Hornberger Citation2002, Citation2005, Citation2020). As Hornberger (Citation2005) explains, ‘Implementational spaces can be understood as practices, although implementational spaces encompass spaces beyond the classroom as well, at every level from face-to-face interaction in communities to national educational policies and to globalized economic relations’ (606).

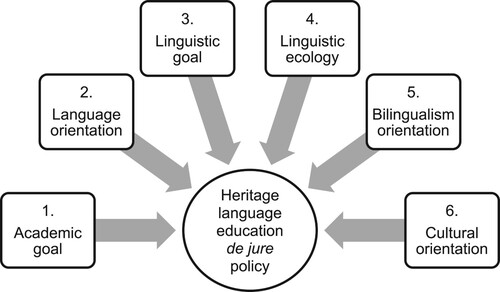

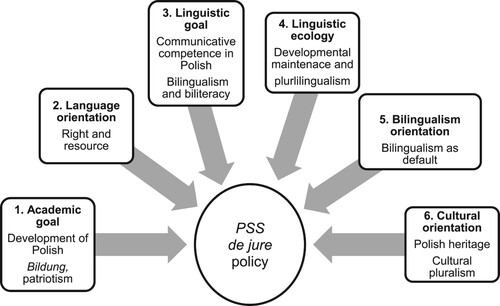

Inspired by several sources (Spolsky, Green, and Read Citation1974; Hornberger Citation1991; Baker Citation2006; Baetens Beardsmore Citation2009; García Citation2009), I created an analytical tool () for exploring more precisely the nature of ideological and implementational spaces, or in McCarty’s (Citation2011) words ‘spaces of hope and possibility’ (119), which the studied policy opens up. The tool is a selection of variables from the sources that suits a policy document analysis.

illustrates the areas that are broached to provide a closer elucidation of the ideological and implementational spaces. Baker’s (Citation2006) operationalization of academic goal comprises many aspects (goals and orientations) that are included in other areas of the analytical tool in . Baker (Citation2006) operationalizes academic goal for HLE as (i) maintenance, (ii) cultural pluralism, (iii) enrichment, and (iv) additive bilingualism. Here, I have allocated them in the following way: maintenance falls under linguistic ecology, cultural pluralism – under cultural orientation and additive bilingualism – under linguistic goal. I will elaborate on each one under corresponding goal and orientation. In sum, academic goal is operationalized as enrichment, which is understood as aiming to ‘extend the individual and group use of minority languages’ (Baker Citation2006, 214).

With respect to language orientation, I draw from Ruíz’ (Citation1984) orientations to language planning: (i) language-as-problem, (ii) language-as-right, and (iii) language-as-resource. Hult and Hornberger (Citation2016) discuss the usefulness of this analytical heuristic and present an extensive list with the fundamental characteristics of each orientation (see Table 1 in Hult and Hornberger Citation2016, 44).

Linguistic goal is operationalized either as (i) monolingualism or as (ii) bilingualism and biliteracy (Baker Citation2006; García Citation2009). According to García (Citation2009), HLE where only HL is taught ‘cannot be considered bilingual education programs per se’ (234), while at the same time pointing out that ‘the esteem in which the language is held by the school community […] is high enough that children develop bilingual and even biliterate proficiencies’ (235). Similarly, Hornberger (Citation2005) says that HLE, by definition, develops HL biliteracy (p.102). The form of bilingualism that is referred to here is additive bilingualism (cf. Baker Citation2006). There are several contrasting viewpoints on literacy and biliteracy for bilingual students, and I analyze the documents from the following angles: the skills approach (Baker Citation2006, 321–322), the construction of meaning approach (Baker Citation2006, 323), the sociocultural literacy approach (Baker Citation2006, 323–324), the critical literacy approach (Baker Citation2006, 324–332), and biliteracy (Baker Citation2006, 327–333).

Linguistic ecology pertains to (i) language shift, (ii) language maintenance, (iii) revitalization, and (iv) plurilingualism (Baker Citation2006; García Citation2009). In the context of HLE, linguistic ecology has usually been defined as the maintenance of HL (e.g. Chik, Carreira, and Kagan Citation2017; Seals and Shah Citation2018; cf. Fishman Citation2013). Baker (Citation2006) refers to Otheguy and Otto (Citation1980) and differentiates between static and developmental maintenance. Static maintenance might prevent HL loss, but does not improve language skills. Developmental maintenance aims at developing full proficiency in a student’s HL and full biliteracy (Baker Citation2006). The notion of plurilingualism is not elaborated on by Baker (Citation2006) and García (Citation2009), and therefore I lean on Moore and Gajo (Citation2009) who observe that ‘Plurilingualism is a fundamental principle of language education policies in Europe, as defined by the Council of Europe […]’ (145). The European documents usually distinguish between plurilingual education and education for plurilingualism, and connect plurilingualism to plurilingual competence (Moore and Gajo Citation2009). Thus, plurilingualism in the linguistic ecology here indicates two important interrelated aspects of (i) two or more languages used separately or together for different purposes, in different domains of life, with different people; and (ii) the view that plurilingual speakers are rarely equally or entirely fluent in their languages, because they use and need different languages for different purposes. Plurilingualism also involves the promotion of respect for languages, cultures, and their diversity, mutual understanding, social cohesion, and participation in democratic citizenship (Moore and Gajo Citation2009).

Regarding bilingualism orientation in policy, García (Citation2009, 121) draws partially upon Ruíz (Citation1984) and describes the orientation as one of the following: (i) bilingualism as problem, (ii) bilingualism as enrichment, (iii) bilingualism as right, or (iv) bilingualism as resource. Definitions of the different types of orientations are based on the types of children who are educated (García Citation2009). Bilingualism as a problem occurs, according to García (Citation2009, 122), when powerless language-minority students are educated in isolation. Bilingualism as enrichment is perceived as privilege and occurs in elite education. When language-minority students have agency based on gained power and rights, bilingualism is considered a right. Finally, bilingualism is seen as a resource when language-minority and language-majority students are educated jointly or when all students are educated bilingually in a given area (García Citation2009).

With respect to cultural orientation, García (Citation2009) proposes the following orientations: (i) monoculturalism, (ii) biculturalism, or (iii) transculturalism. Monoculturalism, according to García (Citation2009, 251) is the ability to function in one culture. Biculturalism, the ability to function in two separate cultures (García Citation2009, 251), is here equated with cultural pluralism or pluriculturalism (Schachner Citation2019; see also Craft Citation1984; cf. cultural goal in Hornberger Citation1991, 223). Schachner (Citation2019) points out that education embracing cultural pluralism ‘may provide a climate that welcomes and appreciates cultural diversity […]’ (4) and that cultural pluralism ‘may also be manifested in a more multicultural curriculum’ (4) that teaches, for instance, customs and traditions in other cultures. How HLE responds to the children’s multiple worlds of heritage and mainstream languages and cultures has also been invoked by Hornberger and Wang (Citation2008): ‘The challenge of finding an alternative way of living with both the heritage and mainstream languages and cultures is the heart of the whole HLE issue’ (17). This line of thinking also exists, however peripherally, in the local Polish research context; Jasiński (Citation2010) emphasizes that while it is important to organize schools and programs abroad with Polish as a language of instruction, the teaching of and in Polish outside Poland should also mean functioning together with the receiving society. Jasiński (Citation2010) intends these schools to be a bridge between Polish culture and the culture of the receiving country. These two functions should be balanced in appropriate proportions so that the heritage language and culture obtain the space they need without at the same time closing themselves off from the world outside (Jasiński Citation2010). Finally, transculturalism refers to different cultural experiences and contexts that are merged and result in ‘a new and hybrid cultural experience’ (García Citation2009, 119).

Research question

Against the conceptual-analytical framework presented above, the specific research question guiding this study is: What ideological and implementational spaces can be identified in the policy documents regarding the following six areas: academic goal, language orientation, linguistic goal, linguistic ecology, bilingualism orientation, and cultural orientation?

The historical context of the Polish State Schools abroad

The Polish State Schools abroad (PSS) submit to the Centre for the Development of Polish Education Abroad, which is a part of the Polish Ministry of National Education.Footnote2 In total, there are 70 schools in 36 countries; during the school year 2022/2023, PSS provided education to approximately 16,000 pupils via about 600 teachers (ORPEG Citation2023). The education covers both elementary school and high school, and includes two subjects: (i) Polish Language (including literature) and (ii) Knowledge of Poland, a subject that contains Polish culture, geography and history, with four teaching hours per week on average (see ).

The origins and development of PSS can be retraced to the geopolitical changes in Poland in the aftermath of the Second World War (Kusztelak Citation2004, Citation2011; Frączek Citation2018). Here; I demarcate and describe in more detail the three turning points of these changes, namely (i) the Iron Curtain era; (ii) the system transformation in Poland from communism and Soviet domination in 1989/1990; and (iii) Poland's accession to the European Union in 2004.

From 1945 until the mid-1960s, the children of Polish diplomatic and military representatives outside Poland were educated within the Soviet educational system by Russian teachers and in Russian (Kusztelak Citation2004, Citation2011). In the mid-1960s, the Polish People’s Republic intensified its economic contacts with Arab-Asian, African, and Western European countries. As a consequence, many Polish specialists received employment in these countries through work agencies controlled by the Polish state. Unlike other citizens, these specialists were allowed to go abroad with their families (Kusztelak Citation2004, Citation2011). The families found the education offered by the Soviet system highly unsatisfactory and aimed for Polish education. Supported by the work agencies, they convinced the government of the Polish People’s Republic to create opportunities for Polish education in host countries. The first ‘Polish State School abroad’ was established in Moscow in 1967 (Kusztelak Citation2004, Citation2011). At this time, the name ‘school’ was not used officially; the official label was school consultation unit, and the units were connected to Polish diplomatic missions. Importantly, the units were not meant to serve Polish migrants and their descendants; their activities were aimed at the children of diplomats and government-contracted employees temporarily residing outside Poland (cf. Hruzd-Matuszczyk Citation2019). It is not hard to imagine that the units – run by the communist regime of the Polish People’s Republic – did not enjoy the trust of the migrants and their descendants, given the political reasons for much of the Polish migration from 1939 to 1989, and a rather adverse attitude of the Polish People’s Republic towards Polish communities abroad (cf. Kraszewski Citation2011; Nowosielski and Nowak Citation2022).

The second turning point was 1989/1990; the system transformation in Poland from communism and Soviet domination began with the Round Table negotiations in 1989 between the governmental party and the opposition groupings united under the Solidarność movement. In an analysis of discourses from the political transformation initiated by the 1989 elections until 2015, Lesińska (Citation2015) found that both right-wing and left-wing parties addressed the issues of migration and diaspora, but that these issues occupied a rather secondary place in Polish foreign policy. Nevertheless, the different governments since 1991, independently of their political orientation, have undertaken specific actions aimed at migration and diaspora, e.g. in the form of developing legal acts (Lesińska Citation2015) or opening, in 1992, the Polish State Schools abroad to groups other than Polish diplomats and government-contracted employees (Hruzd-Matuszczyk Citation2019).

The third turning point was Poland's accession to the European Union in 2004 and the mass post-accession migration (Lesińska Citation2015; Rabiej Citation2015). This migration led to a new situation: statistically every Polish family has at least one family member outside Poland (Lesińska Citation2015; cf. also White Citation2015). Since 2005, the content of the political messages concerning Polish migrants and their descendants has expanded to include new issues; among them, Polish education abroad started receiving even greater attention than it did from 1989 to 2004 (Miodunka Citation2012; Lesińska Citation2015; Rabiej Citation2015). Interestingly, until 2004 Polish scholars were quite convinced that PSS would disappear as a form of Polish-language education outside Poland and anticipated a decline of Polish education abroad more generally; the recent history of Polish education outside Poland, primarily European, turned out to be different than expected – Polish education has instead flourished (e.g. Rabiej Citation2015). Most likely, the post-EU-accession migration from Poland contributed to this development. For instance, the latest PSS was established in 2020 in Iceland (MEN Citation2020). Recently, the Polish government commissioned a report on strategies for teaching and promoting the Polish language globally; this visionary document was written by 18 experts and was published in 2018 (Tambor and Niesporek-Szamburska Citation2018).

Method

Data

The data consists of two legal documents, LSE and Regulation (see ). These documents are available online in Polish and form the official basis of PS activity; they are published in the Official Journal of Laws of the Republic of Poland (Dziennik Ustaw Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej). LSE is a statue adopted by the Sejm (the lower house of the Polish parliament). Regulation is issued by the authority that is expressly stated in LSE, i.e. the minister of national education. LSE is thus a superior document to Regulation; the part regarding Polish education abroad in LSE is rather short (198 words). Regulation comprises (i) a main text (seven pages) and (ii) two appendices, including the core curriculum (60 pages) and outlines (one page), respectively (see ).

Table 1. Summary of the analyzed documents.

Both LSE and Regulation cover areas other than PSS (see Appendix); in this study, I foregrounded areas relevant to PSS. Curriculum presents the curricular content for PS. Outlines state the maximum amount of teaching time per semester.

Analytical approach

The study uses qualitative content analysis (cf. Drisko and Maschi Citation2015). In qualitative content analysis, both manifest and latent content are considered and analyzed (Drisko and Maschi Citation2015, 4). Manifest content or denotative meanings are literal, common-sense, or obvious meanings; latent content or connotative meanings refer to meaning that is not overtly evident in a communication, but rather, is implicit or implied, often spanning several sentences or paragraphs (Drisko and Maschi Citation2015). Ahuvia (2001, 142; referred to in Drisko and Maschi Citation2015) states that ‘connotative meanings – drawn from the latent content – are arrived at by combining individual elements in a text to understand the meaning of the whole.’ Context is a vital component of understanding the meaning of messages, especially latent content (Drisko and Maschi Citation2015).

The data was analyzed both inductively and deductively, and the readings were both sequential and overlapping. In step 1, the data were inductively grouped in key content areas in the documents, see Appendix. In step 2, I looked for words, sentences, and stretches of text that could be connected to the analytical concepts of spaces and the areas presented in (the deductive analysis), and this analysis mainly focused on Curriculum. As Outlines chiefly present the number of teaching hours for PSS, I did not analyze them further.

Meeting Polonia’s educational needs

LSE (The Law on School Education) uses a specific Polish word Polonia that I want to introduce here; after the system transformation in 1989, the scientific community defined the term Polonia based on ‘awareness of ethnic origin’ (Dubisz Citation1990, 165). Thus, it follows that everyone who lives outside Poland and feels affiliated with her/his Polish roots is counted as Polonia, and is thus a potential addressee of LSE. According to LSE (cf. Appendix), Polish citizens living temporarily abroad (henceforth, Polish citizens) have the right to governmentally organized schooling, while citizens permanently living abroad and non-citizens, i.e. Polonia, have to take local educational initiatives in order to receive support from Poland’s government. The implementational space for Polish education in LSE is, thus, conditioned by type of citizenship and non-citizenship. On the contrary, Regulation opens the educational (implementational) space to Polonia; PSS are made accessible not only to children of Polish citizens, but, in principle to all Polonia children: ‘Children of Polish citizens permanently residing abroad and children of non-Polish citizens may also be admitted to the schools, provided the school has vacancies and adequate staffing as well as organizational and financial conditions’ (Regulation, § 5.1, 1, my translation). This formulation can be seen as an essential implementational opening for Polish language education for children to parents who feel an affiliation with Polish language and culture, thus, not only to those who by citizenship have a right to be supported and protected by their state. As mentioned, PSS were opened to Polish migrants and their descendants in 1992, i.e. after the system transformation in Poland when the different governments, independently of their political orientation, had undertaken specific actions addressing Polonia. This step can be understood as an ideological opening in the post-communist era towards those who were often forced to emigrate from the communist Poland, in some cases being deprived of their citizenship (e.g. Polish Jews after the political crisis of 1968 – see e.g. Górniok Citation2016); different Polish governments after the democratic turn in 1989 undertook specific actions addressing Polonia to repair their strained relationships with them, after the over 40-year period of adverse propaganda spread by the communist regime (Kraszewski Citation2011; Nowosielski and Nowak Citation2022).

Importantly, education at PSS is free of charge (Regulation, § 5.2, 1). In order to admit a student to PSS, parents must, however, provide the head of the school with an official or personally issued certificate confirming the attendance at a school in the education system of the receiving country (Regulation, § 5.3, 2). A specific constraint on the PSS is their localization as they are placed close to Polish diplomatic units, usually present in capital cities. While the free-of-charge schooling makes PSS accessible to every Polonia child independently of the economic background of the parents, the location of PSS might limit access to them.

Exploring the specific nature of spaces

In , I summarize the outcome of analysis with the help of .

Academic goal

Academic goal has been operationalized here as enrichment, i.e. an extended opportunity to use a heritage language (cf. Baker Citation2006). No doubt, PSS offer an extended opportunity to use and develop Polish; as Excerpt 1 shows.

Excerpt 1

a) One of the most important tasks of elementary school is the development of Polish language skills, including the enrichment of the vocabulary in the native language. (9)Footnote3

b) One of the most important tasks of high school is the development of communicative and linguistic competence in Polish. (45)

In addition, there are two other academic goals stated in Curriculum that I have termed patriotic and Bildung goal, respectively. Excerpts 2 and 3 illustrate that the patriotic goal is expressed in Curriculum as identification with Polish culture and tradition and as understanding of the value of the Polish language for the development of Polish identity, on the one hand. On the other, patriotism involves respect for the cultural expressions of the receiving society.

Excerpt 2

[The student] receives basic information about Polish culture and society, and identifies with Polish culture and tradition, while respecting the cultural differences and traditions of the country of residence. (10)

Excerpt 3

a) [development of] an understanding of the value of the Polish language and its function in building national and cultural identity. (15)

b) The acquired knowledge will allow [the student] to identify with Polish culture and tradition. (33)

In Excerpt 4, the word patriotism encourages students’ self-reflection on forms and conditions of belonging. The students are expected to develop an awareness of diverse expressions of hostility against ‘Others’ and an awareness of means to stand up against these expressions. Excerpt 4 also illustrates an attempt to address the issue of multiple identities that PSS students most probably have; the possible identities are being ‘a Pole, a European, and a member of the world community’. Remarkably, the identity as a member of the receiving country is not highlighted, perhaps being covered by being ‘a member of the world community’.

Excerpt 4

[The student] explains what connects a human with the great and the small homeland; discusses these ties using him/herself as example; explains, referring to selected examples, what, according to her/him, patriotism is; compares patriotism with nationalism, chauvinism and cosmopolitanism; recognizes the manifestations of xenophobia, including racism, chauvinism, and anti-Semitism; explains the need to oppose such phenomena; considers how stereotypes and prejudices hinder relations between nations today; motivates that one can be a Pole, a European, and a member of the world community at the same time. (43)

Another academic goal is Bildung. The two excerpts (5 and 6) that illustrate this are taken from the high school part of Curriculum, but Bildung is also – to some extent – present in the elementary school part, grades 4–8 (age 10–14).Footnote4 Bildung is a rich and complex concept (Sander Citation2015; Sjöström and Eilks Citation2021), and this complexity cannot be dwelled upon here. Briefly, to define the core of Bildung, I recall Hopmann (Citation1999), who explains Bildung as education that is about neither content nor skills, but is a stance of mind that makes a child able to develop more complex, more profound, and more extensive meanings of events and phenomena (cf. also Westbury, Hopmann, and Riquarts Citation2000). As Excerpts 5 and 6 show, the idea of Curriculum is that literary, cultural, and historical instruction can contribute to developing the state of mind embracing a ‘lifelong education’, ‘a creative and dynamic attitude to life and culture’ and moral virtues.

Excerpt 5

Literary and cultural education […] should emphasize the existential aspects of experiencing oneself, others, and the world, opening up interesting spaces for thinking and evaluating through contact with valuable literature and other cultural texts. It should also introduce traditions as a guardian of collective memory, a link between the past and the present. (55)

Excerpt 6

a) An important role in Polish language education should be fulfilled by self-education understood as preparation for lifelong education, i.e. education of a person characterized by a creative and dynamic attitude to life and culture (55)

b) [The education aims at] the shaping of understanding for values such as truth, goodness, justice, beauty, and developing moral and esthetic sensitivity. (34)

Language orientation

For exploring language orientation, I draw upon Ruíz’ (Citation1984) orientations to language specified further by Hult and Hornberger (Citation2016). Historically, PSS were created as a reaction against the coercion of Russian education on children of Polish diplomats, the military, and government-contracted employees temporarily staying outside Poland. In this way, PSS became an expression of the right to Polish language and Polish education. I also claim that even if not implicitly expressed in LSE, Regulation, and Curriculum, Polish is perceived as a right by the sole existence of the policy (cf. Table 1 in Hult and Hornberger Citation2016, 44, Language-as-right). Also, specific formulations in Curriculum can be found that might be attributed to the language-as-right orientation. For instance, Polish is expected to mediate access to Polish society (cf. Table 1 in Hult and Hornberger Citation2016, 44, Language-as-right) as illustrated by Excerpt 7a. In Excerpt 7b, Polish is related to personal freedom (cf. Table 1 in Hult and Hornberger Citation2016, 44, Language-as-right).

Excerpt 7

a) [The student]

– knows the national symbols […], the most important national holidays and can explain their meaning. (35)

– [develops] an attitude of active participation in Polish culture in the place of residence, especially in its symbolic and axiological dimensions. (p.15)

b) [The student] develops the ability to communicate in various private and public situations. (p.14)

The content of Curriculum includes also evidence of the language-as-resource orientation. Excerpt 8a illustrates how ‘societal multilingualism and cultural diversity are valued’ (Table 1 in Hult and Hornberger Citation2016, 44, Language-as-resource), and Excerpt 8b shows that Polish has intrinsic value for cultural reproduction and identity construction (Table 1 in Hult and Hornberger Citation2016, 44, Language-as-resource).

Excerpt 8

a) [The student]

– justifies that it is possible to reconcile different social and cultural identities (regional, national, ethnic, national, civic, European). (42)

– lists the national and ethnic minorities living in Poland, describes their culture and traditions based on selected examples. (44)

b) [The student] develops an understanding of the value of the Polish language and its function in building national and cultural identity. (15)

Linguistic goal

The manifest linguistic goal is communicative competence in Polish expressed as ‘language skills’ (Excerpt 9a) and ‘communicative competence’ (Excerpt 9b), with a special focus on the development and enrichment of vocabulary. Interestingly, the responsibility for achieving the linguistic goal is not solely appointed to teachers of the subject Polish Language but also to teachers of the subject Knowledge of Poland, or ‘all teachers’/’every teacher’ (Excerpt 9), a call that is frequently done in contexts of teaching in culturally and linguistically diverse contexts (cf. Cummins Citation2000).

Excerpt 9

a) One of the most important tasks of elementary school is the development of Polish language skills, including the enrichment of the vocabulary in the native language. The students acquire these skills with support from all teachers. (9)

b) One of the most important tasks of high school is the development of communicative and linguistic competence in Polish. It is therefore essential to combine theory and practice. Expanding vocabulary, including development of terminology that is specific to each of the subjects, serves the intellectual development of the student, and support and caring for this development is the responsibility of every teacher. (45)

The latent, i.e. not explicitly expressed, linguistic goal of PSS is additive bilingualism and biliteracy. Even if HLE is not considered as bilingual education (García Citation2009), the role of HLE as an important factor in bilingual and biliterate development has been emphasized by different researchers (e.g. Hornberger Citation2005; García Citation2009).

An analysis of the literacy directions in Curriculum shows that already in the elementary school (Excerpt 10), the skills that are supposed to be developed by the students can be related to other literacy approaches than the skill approach (reading, writing and vocabulary). In Excerpt 10a, interpretations of text – a central characteristic of the construction of meaning approach to literacy (Baker Citation2006) – are made explicit. Excerpt 10b and 10c illustrates the sociocultural literacy approach when the students have possibility to engage with texts of different types and become socialized and enlightened in the heritage culture through reading (cf. Baker Citation2006). The critical literacy approach plays an empowering role and ‘must make people aware of their sociocultural context and their political environment’ (Baker Citation2006, 325), thus, it invites the students to interpret and evaluate texts; this is visible in Excerpt 10d. In the analyzed documents, there is also a progression of literacy demands adjusted to the students’ different ages.

Excerpt 10

a) reading – understood both as a simple activity and as the ability to understand, use and process texts to the extent that they can provide knowledge, emotional, intellectual and moral development, and participation in society life, including the life of the Polish community in the place of residence (9)

b) [The student] can see the differences between fiction, scientific literature, popular science and journalism. (p.21)

c) Knowledge about Poland: national symbols; famous Poles; holidays and traditions; polonicaFootnote5 in the place of residence (14)

d) [The student]

– searches for and analyzes messages on the Internet, in Polish media (if possible): press, radio, television;

– critically and consciously perceives the content.

– perceives and determines the differences between information and other messages, including opinions, evaluation, criticism; (21)

Linguistic ecology

The academic goal of PSS is the development of Polish, and their linguistic goals are communicative competence in Polish, additive bilingualism, and biliteracy. Thus, it is obvious that the linguistic ecology of Curriculum is developmental maintenance (cf. Baker Citation2006). However, there are also some traces of plurilingualism, especially regarding the promotion of respect for different languages, cultures, and diversity (cf. Moore and Gajo Citation2009) as, for instance, expressed in the content for elementary school grades 4–8: ‘[the student] recognizes the diversity of cultural traditions and respects differences between nations’ (12).

Bilingualism orientation

None of the orientations mentioned by García can be successfully applied to how bilingualism is positioned in the analyzed documents. The types of the bilingualism orientations proposed by García (Citation2009, 120) – bilingualism as problem, as enrichment, as right, or as resource – are based on the types of children for which the education is addressed: powerless; elite; with agency; minority and majority together (García Citation2009). The students that PSS address are viewed as having different types of proficiency in Polish: ‘the content of teaching should be adjusted to the language levels of the students’ (Curriculum, 27); the levels are A – basic, B – medium, and C – advanced and are described for three age groups: 5–9, 10–13, and 14 + . In addition, as stated earlier, parents must provide the head of the school with a certificate of attendance at a school in the education system of the receiving country. In the analyzed documents, bilingualism is either contested (problem), celebrated (enrichment, resource), or struggled for (right). Additive bilingualism is just assumed, and therefore I would like to add a new bilingualism orientation to those proposed by García (Citation2009), namely bilingualism as default. I intend that this type might be especially useful for HLE. The bilingualism as default orientation means that policy actors expect that the children will come to the school with language(s) other than the HL and with different communicative competences in HL. The recognition of different HL levels might be understood as a way of opening up implementational spaces for meeting the linguistic reality of the targeted children.

Cultural orientation

Hornberger and Wang (Citation2008) as well Jasiński (Citation2010) highlight the challenge for HLE regarding how to organize HL schools and programs to successfully meet children’s multiple worlds of heritage and mainstream languages, and how to balance these worlds. In other words, there is an issue here of what cultural orientation to take within HLE. For PSS, there is evidence that they are, in part, oriented towards cultural pluralism, e.g. ‘[the aim is to develop] respect for other people and achievements of other nations’ (Curriculum, 33) and ‘[the student] compares Polish holidays with holidays in the country of residence’ (Curriculum, 12). PSS seem to create an environment where cultural diversity is welcomed and appreciated (cf. Schachner Citation2019). Remarkably, this orientation appears to fade away in high school, where Bildung becomes more prominent.

Conclusions

The research question asked here has been what ideological and implementational spaces could be identified in the official policy documents for the complementary Polish State Schools abroad (PSS) regarding the following six areas: academic goal; language orientation; linguistic goal; linguistic ecology; bilingualism orientation; cultural orientation. The analyzed de jure policy opens up implementational spaces for a free educational opportunity for those in the Polish diaspora who want to offer their children a meaningful educational experience in Polish, in addition to mainstream education in the receiving country.

No doubt, the development of communicative competence in Polish is a primary goal of PSS thus creating both an ideological and an implementational space for the development of proficiency in Polish; but the policy aims even higher. It opens up implementational epistemic spaces by advocating literary, cultural, and historical instruction designed for developing a habit of lifelong learning (cf. Bildung), thus, going beyond Polish language maintenance alone. Given the patriotism goal there is space for development and cultivation of the Polish cultural heritage. Both patriotism and Bildung as academic goals are a reasonable consequence of the documents’ language orientation that includes two dispositions: language-as-right and language-as-resource. Thus, HLE might not only be about language maintenance and ‘esteem’ for HL, but can also have epistemic goals that provide opportunities for a multifaceted personal and societal development of the students. This insight is an important contribution to the fields of HLE and bilingual education.

Another important contribution of this study to the fields of HLE and bilingual education is the proposal to add a fifth bilingualism orientation – bilingualism as default – to García’s (Citation2009) four current orientations; this fifth orientation might be a specific characteristic of HLE. Alongside communicative competence in Polish as a primary linguistic goal, additive bilingualism and biliteracy are two other linguistic goals in the policy, albeit not explicitly manifested in the analyzed documents. The policy recognizes the multiple linguistic reality of the students by expecting three different levels of Polish proficiency upon enrollment and accepting only those students who are already enrolled in the school system of the receiving country. In this way, the policy assumes bilingualism, thereof the construct and the label bilingualism as default.

Similar to additive bilingualism, the policy offers a space for additive biliteracy because it enables an extensive development of literacy in Polish, ranging from pure skill development to critical literacy. Due to space limitations, it was possible to extract a rather general idea of the literacy directions, but an in-depth tracing of the various literacy approaches is a promising area for future research.

One of the challenges for HLE pointed out by researchers is how to successfully meet up children’s multiple worlds of heritage and mainstream languages and cultures, and how to balance these worlds so that the heritage part receives enough attention without becoming too self-centered. The analyzed policy remains mainly culturally oriented towards Polish heritage, and at the same time includes aspects of cultural pluralism and plurilingualism, e.g. respect for the achievements of other nations; awareness of differences and similarities between various traditions (cf. cultural orientation); and respect for different languages, cultures, and their diversity (cf. linguistic ecology). An intriguing empirical question for future research is if cultural pluralism and plurilingualism as positioned in the policy create satisfactory ideological and implementational spaces for teachers, parents, and children, and if they are sufficient to meet the challenge of HLE and contribute to an ideological and implementational balance between the heritage and the mainstream environment.

In closing, language policy happens as much at the macro-level of government as at the micro-level of the classroom (e.g. Spolsky Citation2017). To further corroborate how the textual expressions of the documents actually relate to the organization of educational practices, it is necessary to examine language practices at the schools as well as the orientations and goals of teachers, parents, and children (cf. Hornberger Citation2020).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Dorota Lubińska

Dorota Lubińska is an assistant professor in language education and Swedish as a second language at Stockholm University. Her research interests include linguistic, sociolinguistic and educational perspectives on migrant languages. She has written about Polish language attrition and family language policy. Currently, she is working on a project focusing on Polish language education abroad.

Notes

1 In Polish, the schools are called ‘Polish schools’, while the schools run by the Polish communities are called ‘Polish Community schools’ or ‘Polonia schools’ (cf. ORPEG Citation2023; see also p. 11 for the explanation of the term Polonia).

2 The name of this ministry heavily fluctuated and was recently changed; I use the name that appears in the analyzed documents.

3 All translations are mine.

4 The part for elementary school grades 1–3 is instead concerned with Erziehung, which I do not develop more in this paper. My impression is that there is also a progression in the Curriculum (2019) from Erziehung to Bildung; this impression might or might not be confirmed in a study focused on the educational origins of the Curriculum.

5 Polonica = Polish prints and prints about Poland as well as artifacts and places related to Poland available in the receiving country.

References

- Alexander, N. 2003. Language Education Policy, National and Sub-national Identities in South Africa. Strasbourg: Council of Europe.

- Baetens Beardsmore, H. 2009. “Bilingual Education: Factors and Variables.” In O. García, Bilingual Education in the 21st Century: A Global Perspective, 137–158. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Baker, C. 2006. Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Baker, C., and W. E. Wright. 2017. Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Chick, J. K. 2002. “Constructing a Multicultural National Identity: South African Classrooms as Sites of Struggle Between Competing Discourses.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 23: 462–478. doi:10.1080/01434630208666480.

- Chik, C. H., M. Carreira, and O. Kagan. 2017. “Introduction.” In The Routledge Handbook of Heritage Language Education, edited by O. Kagan, M. M. Carreira, and C. H. Chik, 1–7. New York and London: Routledge.

- Craft, M., ed. 1984. Education and Cultural Pluralism. New York and London: Routledge.

- Cummins, J. 2000. Language, Power and Pedagogy: Bilingual Children in the Crossfire. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Drisko, J. W., and T. Maschi. 2015. Content Analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dubisz, S. 1990. “Polonia – pojęcie, historia, język.” Polonistyka 4: 164–169.

- Dubisz, S. 2015. “Dwadzieścia lat później – język polski poza granicami kraju– historia badań i ich perspektywy.” Poradnik Językowy 8: 7–11. https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=298842.

- Fishman, J. 2013. “Language Maintenance, Language Shift, and Reversing Language Shift.” In The Handbook of Bilingualism and Multilingualism, edited by T. K. Bhatia, and W. C. Ritchie, 466–494. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Frączek, A. 2018. “Kształtowanie się kultury edukacyjnej francuskiej Polonii.” Cywilizacja i Polityka 16 (16): 13–30. doi:10.5604/01.3001.0012.7591.

- Gajdzica, A., G. Piechaczek-Ogierman, and A. Hruzd-Matuszczyk. 2014. Edukacja postrzegana z perspektywy uczniów, rodziców i nauczycieli ze szkół z polskim językiem nauczania w wybranych krajach europejskich. Toruń: Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek.

- García, O. 2009. Bilingual Education in the 21st Century: A Global Perspective. Malden: Blackwell.

- Górniok, Ł. 2016. “Swedish Refugee Policymaking in Transition? Czechoslovaks and Polish Jews in Sweden, 1968-1972.” Doctoral thesis, Umeå University. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn%3Anbn%3Ase%3Aumu%3Adiva-119532.

- Hopmann, S. 1999. “The Curriculum as a Standard of Public Education.” Studies in Philosophy and Education 18: 89–105. doi:10.1023/A:1005139405296.

- Hornberger, N. H. 1991. “Extending Enrichment Bilingual Education: Revisiting Typologies and Redirecting Policy.” In Focus on Bilingual Education, edited by O. García, 215–234. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Hornberger, N. H. 2002. “Multilingual Language Policies and the Continua of Biliteracy: An Ecological Approach.” Language Policy 1 (1): 27–51. doi:10.1023/A:1014548611951.

- Hornberger, N. H. 2005. “Opening and Filling up Implementational and Ideological Spaces in Heritage Language Education.” Modern Language Journal 89 (4): 605–609. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2005.00331.x.

- Hornberger, N. H. 2020. “Reflect, Revisit, Reimagine: Ethnography of Language Policy and Planning.” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 40: 119–127. doi:10.1017/S026719052000001X.

- Hornberger, N. H., and D. C. Johnson. 2007. “Slicing the Onion Ethnographically: Layers and Spaces in Multilingual Language Education Policy and Practice.” TESOL Quarterly 41 (3): 509–532. doi:10.1002/j.1545-7249.2007.tb00083.x.

- Hornberger, N. H., and S. Wang. 2008. “Who are our Heritage Language Learners? Identity and Biliteracy in Heritage Language Education in the United States.” In Heritage Language Education: A new Field Emerging, edited by D. Brinton, O. Kagan, and S. Bauckus, 3–35. New York and London: Routledge.

- Hruzd-Matuszczyk, A. 2019. “Szkoły z polskim językiem nauczania wyzwaniem dla edukacji XXI wieku - wybrane zagadnienia.” Edukacja Międzykulturowa 2 (11): 235–254. doi:10.15804/em.2019.02.16.

- Hult, F. M., and N. H. Hornberger. 2016. “Revisiting Orientations in Language Planning: Problem, Right, and Resource as an Analytical Heuristic.” The Bilingual Review/La Revista Bilingüe 33 (3): 30–49. https://repository.upenn.edu/gse_pubs/476.

- Jasiński, Z. 2010. “Oświata i kultura polonijna a koncepcja wielokulturowości.” Studia Migracyjne- Przegląd Polonijny 3: 35–48.

- Johnson, D. C. 2010. “Implementational and Ideological Spaces in Bilingual Education Language Policy.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 13 (1): 61–79. doi:10.1080/13670050902780706.

- Johnson, D. C. 2011. “Implementational and Ideological Spaces in Bilingual Education Policy, Practice, and Research.” In Educational Linguistics in Practice: Applying the Global Locally and the Local Globally, edited by F. M. Hult, and K. A. King, 126–139. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Johnson, D. C. 2013. Language Policy. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Johnson, D. C., and R. Freeman. 2010. “Appropriating Language Policy on the Local Level: Working the Spaces for Bilingual Education.” In Negotiating Language Policies in Schools: Educators as Policymakers, edited by K. Menken, and O. García, 13–31. New York and London: Routledge.

- Kraszewski, P. 2011. “Polityka PRL wobec Polonii.” Przegląd Polsko-Polonijny 1 (3): 41–58. https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=108639.

- Kusztelak, A. 2004. “Szkoła polska poza granicami kraju animatorem integracji społeczności polskiej.” Kultura i Edukacja 4: 99–106. https://bazhum.muzhp.pl/media/files/Kultura_i_Edukacja/Kultura_i_Edukacja-r2004-t-n4/Kultura_i_Edukacja-r2004-t-n4-s99-106/Kultura_i_Edukacja-r2004-t-n4-s99-106.pdf.

- Kusztelak, A. 2011. “Organizacja i zarządzanie instytucjami oświatowymi przy przedstawicielstwach dyplomatycznych RP.” Zeszyty Naukowe WSHiU Poznań 21: 101–123. https://wshiu.pl/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/ZN_21.pdf#page=102.

- Łączek, M. 2018. Szkolnictwo polonijne w kontekście egzolingwalnym. Roczniki Humanistyczne, LXVI (10), 73–89.

- Lesińska, M. 2015. Emigracja i diaspora w dyskursie politycznym w Polsce w latach 1991-2015. CMR Working Papers No. 83/141.

- Lipińska, E., and A. Seretny. 2012. “Szkoła polonijna czy językowa? Szkolnictwo polonijne w perspektywie dydaktycznej.” Studia Migracyjne - Przegląd Polonijny 38 (4): 23–38. http://cejsh.icm.edu.pl/cejsh/element/bwmeta1.element.desklight-091d5280-0afe-4f65-ae04-700ef34f6eb4.

- McCarty, T. 2011. “Thematic Overview III: Unpeeling, Slicing and Stirring the Onion – Questions and Certitudes in Policy and Planning for Linguistic Diversity in Education.” In Educational Linguistics in Practice: Applying the Local Globally and the Global Locally, edited by F. Hult, and K. King, 109–125. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- MEN [The Polish Ministry of National Education]. 2020. “Współpraca Polski i Islandii w dziedzinie oświaty – deklaracja podpisana, March.” https://www.gov.pl/web/edukacja-i-nauka/wspolpraca-polski-i-islandii-w-dziedzinie-oswiaty–deklaracja-podpisana.

- Miodunka, W. T. 2012. “Polszczyzna w programach edukacyjnych.” In Wyzwania polskiej polityki językowej za granicą: kontekst, cele, środki i grupy odbiorcze, edited by A. Dąbrowska, W. Miodunka, and A. Pawłowski, 27–45. Warszawa: Ministerstwo Spraw Zagranicznych.

- Moore, D., and L. Gajo. 2009. “Introduction—French Voices on Plurilingualism and Pluriculturalism: Theory, Significance and Perspectives.” International Journal of Multilingualism 6: 137–153. doi:10.1080/14790710902846707.

- Nowosielski, M., and W. Nowak. 2022. “‘We are not Just Asking What Poland Can do for the Polish Diaspora but Mainly What the Polish Diaspora Can do for Poland’: The Influence of New Public Management on the Polish Diaspora Policy in the Years 2011–2015.” Central and Eastern European Migration Review 11 (1): 109–124. doi:10.54667/ceemr.2022.04.

- Ogrodzka-Mazur, E. 2017. “Między etnicznością a integracją. Strategie kulturalizacyjne przyjmowane przez społeczności szkół z polskim językiem nauczania.” Lubelski Rocznik Pedagogiczny 36 (3): 61–79. doi:10.17951/lrp.2017.36.3.61.

- ORPEG. 2023. Szkoły polskie, January. https://www.orpeg.pl/szkoly/szkoly-polskie/.

- Otheguy, R., and R. Otto. 1980. “The Myth of Static Maintenance in Bilingual Education.” The Modern Language Journal 64 (3): 350–356. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4781.1980.tb05205.x.

- Rabiej, A. 2015. “Nowa krajowa polityka edukacyjna wobec Polonii.” Poradnik Językowy 8: 117–131.

- Ruíz, R. 1984. “Orientations in Language Planning.” NABE Journal 8 (2): 15–34. doi:10.1080/08855072.1984.10668464.

- Sander, W. 2015. “Was heißt “Renaissance der Bildung”?” Zeitschrift für Pädagogik 61 (4): 517–526. doi:10.25656/01:15375.

- Schachner, M. K. 2019. “From Equality and Inclusion to Cultural Pluralism – Evolution and Effects of Cultural Diversity Perspectives in Schools.” European Journal of Developmental Psychology 16 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1080/17405629.2017.1326378.

- Seals, C. A., and S. Shah, eds. 2018. Heritage Language Policies Around the World. New York and London: Routledge.

- Sjöström, J., and I. Eilks. 2021. “The Bildung Theory- from von Humboldt to Klafki and Beyond.” In Science Education in Theory and Practice: An Introductory Guide to Learning Theory, edited by B. Akpan, and T. Kennedy, 55–67. Cham: Springer.

- Spolsky, B. 2017. “Investigating Language Education Policy.” In Research Methods in Language and Education. Encyclopedia of Language and Education, edited by K. King, Y. J. Lai, and S. May, 39–52. Cham: Springer.

- Spolsky, B., J. B. Green, and J. Read. 1974. “A Model for the Description, Analysis, and Perhaps Evaluation of Bilingual Education.” Navajo Reading Study Progress Report No. 23.

- Tambor, J., and B. Niesporek-Szamburska, ed. 2018. Nauczanie i promocja języka polskiego w świecie: Diagnoza - stan - perspektywy. Katowice: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego. http://wydawnictwo.us.edu.pl/sites/wydawnictwo.us.edu.pl/files/wus_2018_nauczanie_i_promocja_jezyka_polskiego_ebook_interaktywny.pdf.

- Tollefson, J. W., ed. 2013. Language Policies in Education: Critical Issues. New York and London: Routledge.

- Tsui, A. B. M., and J. W. Tollefson. 2004. “The Centrality of Medium-of-Instruction Policy in Sociopolitical Process.” In Medium of Instruction Policies: Which Agenda? Whose Agenda?, edited by J. W. Tollefson, and A. B. M. Tsui, 1–18. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Westbury, I., S. Hopmann, and K. Riquarts, eds. 2000. Teaching as a Reflective Practice: The German Didaktik Tradition. New York and London: Routledge.

- White, A. 2015. “Polish Migration to the UK Compared with Migration Elsewhere in Europe: A Review of the Literature.” Social Identities 22 (1): 10–25. doi:10.1080/13504630.2015.1110352.

- Wiley, T. G. 2015. “Language Policy and Planning in Education.” In The Handbook of Bilingual and Multilingual Education, edited by W. E. Wright, S. Boun, and O. García, 164–184. Malden: Wiley-Blackwell.

Appendix

Key content areas in the analyzed documents.