ABSTRACT

Bilingual education that incorporates a local language alongside the official language has become an increasingly common approach in sub-Saharan Africa for improving literacy rates and learning outcomes. Evidence suggests that bilingual instruction is largely associated with positive learning and literacy outcomes globally. However, the adoption of bilingual education does not guarantee positive learning outcomes. This paper reviews bilingual programs in sub-Saharan Africa, with a particular focus on programs in six Francophone West African countries (Niger, Senegal, Mali, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Cameroon). We identified factors critical to high-quality and effective bilingual programs. Implementation factors, such as teacher training and classroom resources, and socio-cultural factors, such as perceptions of local languages in education, constrain and contribute to the quality of bilingual education. These insights may help inform policy-makers and other stakeholders seeking to improve bilingual education programs in Francophone West Africa and other contexts.

Introduction

In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), where only 66% of adults aged 15 + are literate (UNESCO Institute for Statistics Citation2020), many children learn to read in an official language that is not spoken in their community or home (Heugh Citation2011). The mismatch between the language of instruction (LoI) and community language can create learning challenges for children in multilingual communities. For example, hindering literacy development, or participation in classroom discussions, thus impacting children’s persistence in school, contributing to reduced literacy rates and poor learning outcomes. With the global push to improve education quality and learning outcomes for all children, formalized as the United Nations Sustainable Development Goal 4, bilingual education has generated interest as a potential tool to improve children’s learning outcomes.

Bilingualism and bilingual education are associated with positive language, literacy, and academic outcomes: children exposed to two languages at an early age, whether at home or school, demonstrate better outcomes than their monolingual peers in SSA and beyond (Ball et al. Citation2022; Benson Citation2020; Bühmann and Trudell Citation2007; Jasińska and Petitto Citation2018; Jasińska et al. Citation2017; Jasińska et al. Citation2019; Takam and Fassé Citation2020). In SSA multilingual communities, bilingual education programs that incorporate a child’s first language (L1) place value on children’s language and culture, supporting confidence, self-esteem, and academic achievement (Brock-Utne Citation2012; Dutcher Citation1982). Bilingual education may also reduce grade repetition and attrition rates (World Bank Citation2005).

While evidence from SSA increasingly suggests positive associations between bilingual education and learning outcomes, the benefits of bilingual education vis-a-vis learning outcomes are not universal. Learning outcomes in bilingual education programs can be highly context-dependent, and a range of factors may constrain the quality of bilingual education, limiting its potential benefits to children’s learning outcomes in different contexts. Existing bilingual education research, much of which has been conducted in Western contexts, should not be assumed to apply broadly.

Some bilingual education challenges may be similar across Western and SSA contexts (e.g. resources, teacher professional development; Baker Citation2011). However, the linguistic and socioeconomic contexts of Francophone West Africa, specifically Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Guinea, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Senegal, and Togo, may contribute to these challenges differently. French is typically the language of prestige and socioeconomic mobility, yet the region is highly multilingual, with many West African languages spoken throughout (Eberhard, Simons, and Fennig Citation2022; Jasińska, Ball, and Guei Citation2023). These contextual factors are reflected in resource constraints such as teacher shortages (e.g. lack of teachers who speak all LoIs; teacher absenteeism; Jasińska and Guei Citation2021; Traoré, Kaboré, and Rouamba Citation2008), inadequate teacher training and/or professional support (e.g. teachers hiring based solely on cultural background), and insufficient teaching materials in local languages (Ball et al. Citation2022; Sanogo Citation2007; Traoré, Kaboré, and Rouamba Citation2008). These constraints may shape program implementation in West Africa: bilingual education may be low quality or educators may abandon the local LoI altogether (Akyeampong et al. Citation2013; Piper and Miksic Citation2011). Parents may also ascribe more value to education in an official language (e.g. French, English), which opens doors for socioeconomic mobility. This may influence whether they send their children to a traditional single-language or bilingual school (Bühmann and Trudell Citation2007; Cleghorn, Merritt, and Abagi Citation1989; Muthwii Citation2004).

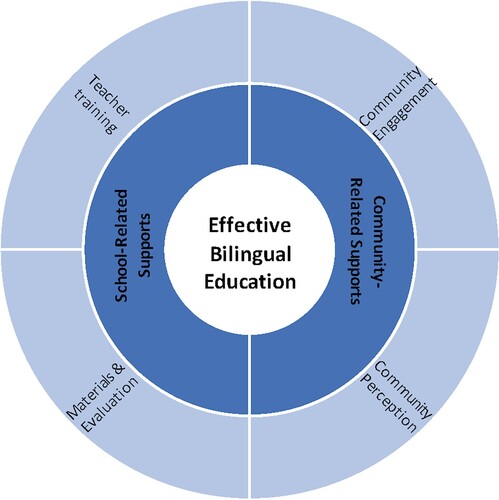

In this review, we explore key elements of nine bilingual education programs in Francophone West Africa. To the best of our knowledge, this review provides the first synthesis of common challenges and successes of bilingual education programs in the Francophone West African region, where bilingual education programs remain understudied. Our review is not exhaustive of all bilingual programs in this region and does not compare programs. Instead, we aim to surface factors that may constrain and facilitate these programs within their contexts to inform planning and implementation of new and existing bilingual education initiatives. Our analysis proposes that a high-quality and effective bilingual program addresses two broad categories of challenges: school-based and community-based challenges that include implementation and socio-cultural barriers (see ).

Bilingual education programs

In the context of our review, bilingual education is not ‘the use of two languages as the media of instruction’ (Ruiz Citation1997) but rather an umbrella housing a range of programs with varying structural and contextual characteristics. Structural characteristics of the program may include the languages used in the curriculum (i.e. official language [e.g. French, English]; local language [e.g. Baoulé in Côte d’Ivoire]), proportion of instruction in each language (e.g. 90:10 or 50:50 local language:French), order in which languages are introduced in the curriculum, and duration of instruction in a given language (i.e. early-exit or late-exit; Hornberger Citation1991). Contextual characteristics include elements such as the student population (e.g. numbers, socioeconomic status [SES], language background) and teacher characteristics (e.g. teacher training, degree of bilingualism, and ethnic background).

Sequential and simultaneous bilingual education programs

Bilingual programs vary on a continuum from sequential to simultaneous. Sequential programs include (1) early-exit programs, which transition to second language (L2) instruction within grades 1–3, and (2) late-exit programs, which transition to L2 instruction in grades 4–6 (Heugh Citation2011). While early-exit programs transition children to L2 instruction to build their proficiency quickly (Ochoa and Rhodes Citation2005), late-exit programs aim to develop children’s L1 language and literacy skills before transitioning to L2 (Baker Citation2011; Kim, Hutchison, and Winsler Citation2015). Sequential programs gradually introduce the target language (e.g. French) until reaching 100% instruction, or maintain bilingual instruction by gradually introducing the target language until reaching a 50:50 proportion of instruction in each language (e.g. Fulfuldé:French in Mali). Simultaneous bilingual programs incorporate equal proportions of instruction in each language (e.g. 50:50 Baoulé:French) within a designated period (day, week, school year) in each grade. Simultaneous programs may combine children’s L1 with French (e.g. in Burkina Faso; Hanemann Citation2018) or incorporate both of a country’s official languages (e.g. English and French in Cameroon; Takam and Fassé Citation2020). These programs aim to enrich children’s language and literacy skills while they learn the country’s official language. Finally, in addition to bilingual models, one language may be taught as a subject (Heugh Citation2011).

Bilingual education programs in Francophone West Africa: context and outcomes

This section overviews nine bilingual education programs in nations in, or bordering, West Africa (Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Côte d'Ivoire, Mali, Niger, Senegal). We present contextual information for each program and program outcomes (e.g. child, teacher, and parent experiences) – both successes and constraints.

Literature search method

These education program case studies were selected from a survey of both academic and gray literature for French bilingual education primary school programs in Francophone West African countries (i.e. Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Côte d'Ivoire, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Togo, Benin, Mauritania, Guinea). We searched for literature in both English and French in the following databases from October-December 2022: APA PsycInfo (Ovid), Education Source, ERIC, Child Development and Education Studies, Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts, sur EDUCI (Edition Universitaire de Côte d’Ivoire), and Google Scholar. The databases were chosen based on relevant subject matter; we specifically searched for literature that discussed program implementation, measures of learning outcomes (e.g. language, literacy, math skills), and/or schooling outcomes (e.g. grade repetition, school completion, standardized test scores, etc.). The search was agnostic to program origin – it included governmental, non-governmental, and private programs. We found no literature matching our search criteria for Togo, Benin, Mauritania, or Guinea; this review did not include these countries. See Supplemental Table 1 for the search terms. This paper is a literature review, not a scoping or systematic review. Therefore, our aim was not to be exhaustive of all bilingual education programs in the region; our goal was to highlight common successes and constraints of the bilingual program case studies in Francophone West Africa. In , we include additional information on all Francophone West African countries in this review. summarizes the review below.

Table 1. Demographic information for countries included in this review.

Table 2. Bilingual education programs included in this review.

Niger

In Niger, French remains the LoI in primary school programs (Hovens Citation2002). In 1973, the Ministry of Education began an experimental bilingual school program (Ecole Experimentale, EE); a late-exit sequential program. Children learned in a Nigerien language (i.e. Hausa, Zarma/Songhay, Fulfulde/Peul/Fula, Tamajaq, Kanouri) in grades 1–3. French was gradually introduced midway through grade two. Full transition to French instruction occurred in grade four and the Nigerien language was maintained as a subject (Hovens Citation2002).

Children attending EE schools outperformed their peers at traditional schools on literacy tests in both languages (i.e. Nigerien language and French), and all children performed better on the math test when administered in the Nigerien language (Hovens Citation2002). These results emphasize the importance of evaluating children’s learning in all of their languages, as a more comprehensive indicator of children’s true language abilities (Jasińska et al. Citation2022).

In contrast, Alidou and colleagues (Citation1997) found that children attending EE schools performed similarly to their peers in traditional French schools on French language, literacy, math, and social studies tests. However, children in both schools performed below average (Alidou Citation1997). These results suggest that language and content area teaching in both school systems was inadequate, and instruction in a Nigerien language alone was insufficient to remedy poor quality education. Although Hovens (Citation2002) found favorable outcomes for children in EE schools, teachers lacked adequate training and teaching materials in both traditional and EE schools. While EE schools had lower student:teacher ratios with more student-centered instruction, parents from higher SES families hesitated to send their children to EE schools because they believed their children would not learn French sufficiently (Hovens Citation2002). These factors may have contributed to the poorer outcomes found by Alidou and colleagues (Citation1997).

Senegal

The NGO-led ‘Support Program for Quality Education in Mother Tongues for Primary Schools in Senegal’ (Benson Citation2020), created by Associates in Research and Education for Development (ARED), was integrated into public school classrooms in 2010–2011. The program featured simultaneous 50:50 Senegalese language (i.e. Wolof or Pulaar):French instruction for science, math, and literacy. The goal of this late-exit program, where children received bilingual instruction from grades 1–4 (Benson Citation2020), was to enrich children’s literacy and math skills through Senegalese language instruction (ARED Citation2014).

Children in ARED’s program outperformed traditional French programs in all subjects. Several program aspects reflected coordinated efforts to implement high-quality bilingual education. An evaluation system to monitor children’s progress and academic performance was embedded in the program (Benson Citation2020). School officials and teachers received training and teaching materials in Senegalese languages. ARED also raised awareness about the value of Senegalese languages in education through consciousness-raising workshops, gaining support for Senegalese language instruction. Families became more involved in their children’s schooling as children taught their family members to read and write in both languages. Parents, school officials, teachers, and government officials responded overwhelmingly positively to ARED’s program; all stakeholders wanted to extend and expand the program (Benson Citation2020).

Mali

In 1987, the government of Mali implemented Pédagogie convergente with the goal of encouraging functional bilingualism. This program featured instruction in a Malian language (i.e. Bamanankan, Fulfuldé, Songhay, Tamasheq, Dogon, Soninké, Bomu, Syenara, Tyeyaxo, Mamara, Khassonké; UNESCO Citation2006). Children start primary school learning in a Malian language, then reach simultaneous 50:50 Malian language:French instruction by grade 3–4. French becomes the primary LoI in grade five with the Malian language taught as a subject (Sanogo Citation2007). Students attending Pédagogie convergente schools outperformed their peers attending traditional French schools on the seventh-grade entrance exam, and language (Bamanankan and French) and math tests. Third-grade children attending Pédagogie convergente schools, who had only begun learning French in second grade, scored higher on French language and mathematics tests (Bühmann and Trudell Citation2007). Bühmann and Trudell (Citation2007) attribute these successes to the development of a student-centered bilingual curriculum and teaching materials and methods, ensuring that teachers have the resources to implement quality bilingual instruction successfully. Mali’s assessment regimen also legitimized bilingual education to the community: Mali’s primary school exit exam includes a Malian language and French and may have improved community perceptions of bilingual education (Bühmann and Trudell Citation2007).

In contrast, Sanogo (Citation2007) found that third and sixth-grade children from a traditional French school performed better than children from a Pédagogie convergente school on a writing task. Although the teachers were trained on the Pédagogie convergente curriculum, and the curriculum provided freedom for adaptation, teachers placed less emphasis on the Malian language in the classroom. Materials were also not available in the classrooms studied, and writing skills were not emphasized, possibly preventing children from establishing proficient literacy in both the Malian language and French (Sanogo Citation2007). These factors may have contributed to children’s poorer writing performance. However, Sanogo (Citation2007) noted positive student-teacher relationships and student interactions using the Malian language; suggesting important social benefits.

Another bilingual education program, the Community School (CS) program, was developed by Save the Children (US-based NGO) and Mali’s Ministry of Education. The program was originally designed to include 3–4 years of schooling in Bambara for children who may not continue to secondary education (Muskin Citation1999). Later, it was extended to a six-year program with the first three years of instruction in Bambara and the last three years of instruction in French applying the same national curriculums as the traditional school (Dutcher Citation2001; Muskin Citation1999). A 1996 evaluation demonstrated that CS students in grades 1–3 performed better on language and literacy tests in Bambara than their traditional school counterparts performed in French, and just as well on arithmetic tests (Dutcher Citation2001; Muskin Citation1997; Muskin Citation1999). Further, CS had lower dropout and grade repetition rates (Muskin Citation1999). This success may be partially attributed to the availability of teaching materials and support for teachers, culturally-appropriate curriculum, smaller class sizes, and student-centered classrooms (Dutcher Citation2001; Muskin Citation1997; Citation1999). Third graders in CS, however, had relatively low scores overall, suggesting that the initial plan of a three-year cycle was not enough to achieve long-lasting academic abilities (Muskin Citation1999), supporting the expansion of the program to six years of primary school.

Burkina Faso

In 1994, the government’s Ministry of Basic Education and Literacy and partners (see Hanemann Citation2018) initiated the programme d’éducation bilingue (PEB) in public primary schools, with the goal of improving education quality and literacy outcomes, and developing and promoting national languages (Hanemann Citation2018). PEB schools provided instruction in a Burkinabe language (i.e. Dagara, Dioula, Fulfulde, Gulmancéma, Lyélé, Mooré, Bissa, Nuni; Korgho Citation2001), where instruction gradually reaches 50:50 Burkinabe language:French in grade three (Ilboudo Citation2010; Lavoie Citation2008). During grades 3–5, there is a gradual shift towards French instruction, while the Burkinabe languages are used for explanation and teaching new concepts. (Lavoie Citation2008). In grade five, 90% of instruction is in French (Ilboudo Citation2010).

Children attending PEB schools demonstrated higher pass rates on the primary school exit exam (i.e. certificat d'études primaires, CEP) compared to the national average, notably after only 4–5 years of primary school, rather than the typical six years in traditional programs; potentially attributable to the transfer of knowledge and concepts from their L1 to French (Hanemann Citation2018; Lavoie Citation2008; Zoungrana Citation2014). Moreover, PEB schools demonstrated better promotion, lower dropout, and repetition rates than traditional schools (Zoungrana Citation2014). PEB ensures that teachers have access to materials in Burkinabe languages and are trained in Burkinabe language instruction. Interestingly, PEB also includes adult literacy training so that improved parent literacy skills can support their child’s education (Hanemann Citation2018).

Despite these positive results, PEB still faces challenges. Teachers may feel pressured to teach in French since national exams are conducted in French. Trained teachers and teaching materials in Burkinabe languages are also not always available (Traoré, Kaboré, and Rouamba Citation2008). A lack of community buy-in may also constrain the PEB’s success. The PEB’s goal is to value the child’s L1, community, and culture through programming and involving the community in program evaluation and improvement (Hanemann Citation2018). However, some bilingual schools punished children for using the Burkinabe language, implementing the program in name only. David-Erb’s (Citation2021) interviews with education professionals and teachers conducted in 2013–2014 indicated little support for Burkinabe language instruction at the community level: secondary schools teach in French, Burkinabe language skills (i.e. writing) are infrequently used in formal settings outside of school, and Burkinabe languages were perceived as less prestigious (Ilboudo Citation2010). Many PEB graduates supposedly enter agricultural or vocational work/training rather than secondary school. This may feed negative parental perceptions of PEB graduates having lower French proficiency – a barrier to secondary school – and bilingual schools as better for children unlikely to continue to secondary education (e.g. girls, children with learning difficulties). While it is unclear whether these beliefs are evidence-based or misconceptions held by the community, many parents prefer to send their children to traditional French schools (David-Erb Citation2021).

Côte d’Ivoire

We focus on studies of two bilingual education programs: Le Centre Scolaire Intégré du Niéné (CSIN) and Projet École Intégrée (PEI). CSIN was a non-governmental preprimary program that extended into primary school. CSIN was a late-exit sequential program that featured instruction in Jula or Senoufo from preschool through grade 3. French was taught as a subject in grades 2–3 and became the main LoI in grade four. Children who started the CSIN program in preschool demonstrated proficiency in French very early in primary school. They also performed better than their peers who were not in CSIN on math, attributed to the time they spent learning in Jula or Senoufo. However, the program faced difficulties in recruiting, training, and retaining teachers and with negative community and parent perceptions of local languages in education (Dutcher Citation2001).

Another bilingual education program, PEI, was created in 2001 as a government initiative (Amani-Allaba Citation2016). PEI was a late-exit sequential program where children began preschool in an Ivorian language while gradually being introduced to French. The goal was full integration into monolingual French instruction at the end of primary school. The proportions of Ivorian language to French instruction were as follows: first grade (CP1): 90:10, second grade (CP2): 80:20, third and fourth grades (CE1, CE2) 50:50, fifth grade (CM1): 10:90, sixth grade (CM2) 0:100 (Brou-Diallo Citation2011; Kouame Citation2007). PEI originally included ten Ivorian languages: Attié, Abidji, Agni, Baoulé, Bété, Guéré, Koulango, Mahou, Sénoufo, and Yacouba (Amani-Allaba Citation2016; Brou-Diallo Citation2011). Despite learning in their L1, children attending PEI schools had poorer Ivorian and French language skills and French literacy skills than French monolingual school peers. Yet, children in bilingual schools had lower rates of grade repetition, indicating that they may still have benefitted from learning in a language they already speak (Ball et al. Citation2022).

Overall, the PEI program was not implemented consistently across schools, and no entity ensured PEI schools received the necessary resources. Teachers expressed that they felt unprepared to teach in the Ivorian language and often minimized teaching time in that language. Teacher shortages contributed to less Ivorian language use, with some teachers combining French-only and bilingual classes when another teacher was absent, favoring French instruction instead. Most notably, teachers reported insufficient teaching materials in Ivorian languages. Teacher interviews also indicated socio-cultural challenges. Teachers reported that children from bilingual schools were less prepared for school each day than children in French-only schools vis-a-vis not arriving to school on time, in uniform, and with adequate supplies (Ball et al. Citation2022).

Recently, Côte d’Ivoire has transitioned to the école et langues nationales en Afrique (ELAN) bilingual education program; an initiative that has expanded throughout Francophone West Africa since 2012 and aims to improve the quality and effectiveness of bilingual education in Côte d’Ivoire (Jasińska, Ball, and Guei Citation2023; Organisation internationale de la Francophonie Citation2016).

Cameroon

We focus on dual curriculum bilingual education (DCBE) schools (Takam and Fassé Citation2020) and the Projet de Recherche Opérationnelle pour l’Enseignement des Langues au Cameroun (PROPELCA; Gfeller and Robinson Citation1998).

Cameroon lies at the border of West and Central Africa and has two official languages: English and French. The mainstream education system includes two separate programs, replicating the education systems of France and England. Each system (French, English) includes the other official language as an L2. DCBE schools combine the French and the English curricula; children essentially attend both education programs in one school. The program is simultaneous; each day is equally split between French and English instruction. In grade six, children exit the program to either the mainstream French or English program. DCBE schools do not feature Cameroonian language instruction. Rather, bilingual education aims to achieve bilingualism in Cameroon’s two official languages at the population level. Indeed, parents’ desire for children to become bilingual and biliterate in both official languages contributed to the rise of DCBE schools, despite a lack of official recognition from the government of Cameroon (Takam and Fassé Citation2020).

Children in DCBE schools outperform their peers in mainstream programs on English, French, and math as well as the French CEP and the English First School Leaving Certificate (FSLC) examinations at the end of primary school (Mafomene Citation1996; Takam and Fassé Citation2020). However, these positive outcomes may reflect higher household SES among students attending DCBE programs, rather than the DCBE program itself. The DCBE program has been criticized as elitist; families must purchase costly books and materials in both languages and children spend more time in the classroom each week since the nature of the dual language program involves longer instruction time (Takam and Fassé Citation2020). These features may create barriers for low-income families and families whose children work or help around the home; the benefits of bilingual education are not accessible to all children.

Projet de Recherche Opérationnelle pour l’Enseignement des Langues au Cameroun (PROPELCA) is a bilingual education program that began in the 1980s and featured local languages (i.e. Ewondo, Duala, Fe’efe’e, and Lamnso’) alongside one of the official languages in primary school. PROPELCA was a partnership between the University of Yaounde, the Summer Institute of Linguistics, Institute of Human Sciences, and the Protestant and Roman Catholic education systems and aimed to promote literacy skills through an identity-based bilingual model (Tadadjeu Citation2005). PROPELCA is an early-exit program where children begin primary school learning 75% of the time in the local language and 25% in the official language, and the proportion of official language to local language instruction increases each year until instruction occurs primarily in the official language at the end of primary school (i.e. 15% local language, 85% official language; Chiatoh Citation2014). In grade four, the local language is used only to teach specific subject areas (e.g. geography, history). Children in PROPELCA performed similarly on all final subject-matter exams compared to their peers in a traditional monolingual program but slightly outperformed their peers in math. They also became proficient in using the written form of the local language, and teachers reported that children were better able to express themselves in both languages and preferred using the local language in the classroom, promoting their cultural identity (Gfeller and Robinson Citation1998). Further, the local communities also became more open to local languages in education. Importantly, PROPELCA ensured that teaching materials and training were available for teachers (Chiatoh Citation2014; Gfeller and Robinson Citation1998; Tadadjeu Citation2005). However, the expansion of the program was constrained due to the linguistic diversity of Cameroon and funding difficulties (Chiatoh Citation2014; Tadadjeu Citation2005).

Common challenges to effective bilingual education programs

The nine programs we reviewed differed in goals, structure and implementation, and community buy-in. Many studies reported favorable learning outcomes. For example, children attending EE schools in Niger, Pédagogie convergente and Community schools in Mali, PEB schools in Burkina Faso, DCBE schools in Cameroon, CSIN in Côte d’Ivoire, and ARED’s program in Senegal outperformed their peers in traditional, monolingual schools on various school subjects and exams (Benson Citation2020; Bühmann and Trudell Citation2007; Dutcher Citation2001; Hanemann Citation2018; Hovens Citation2002; Lavoie Citation2008; Muskin Citation1999; Takam and Fassé Citation2020; Zoungrana Citation2014). Our review suggests that these programs appeared to recognize and target similar school-based and community-based challenges to bilingual education in their contexts: teacher training, teaching/learning resources, and community buy-in.

School-related challenges

A common challenge faced by education programs in West Africa, and SSA more generally, is inadequate physical and human resources to support children's learning (e.g. World Bank Citation2021). Among the school-based barriers surfaced in our review were insufficient teacher training and resources available for local languages, which constrained teachers’ ability to implement high-quality bilingual instruction consistently.

Adequate human resources in terms of quantity and quality of trained teachers are crucial for bilingual programs to result in consistent, high-quality instruction and positive learning outcomes. In multilingual communities, teachers may not have sufficient language skills in all LoIs. When teacher training occurs in the country’s official language, teachers may not feel confident teaching in a local language (Akyeampong et al. Citation2013; Cleghorn, Merritt, and Abagi Citation1989) and may revert to the official language in which teacher instruction occurred. For example, in our review, some programs where children demonstrated positive learning outcomes (e.g. Senegal, Burkina Faso) featured teacher training in the local language. In contrast, children in bilingual classes in Côte d’Ivoire did not receive consistent bilingual instruction; teachers favored French instruction when classes were combined as a result of a shortage of trained teachers (Ball et al. Citation2022).

Another theme in the programs we profiled was physical teaching/learning pedagogical materials in the local LoI as an element of a high-quality bilingual education program. Programs in our review faced challenges regarding classroom resources, especially sufficient teaching materials in local languages. Appropriate and adequate learning resources allow students to interact with classroom content. The evidence from Côte d’Ivoire demonstrates the importance of resources for favorable learning outcomes; traditional French schools did not face the same resource challenges as bilingual schools, and this was associated with better literacy skills among their pupils (Ball et al. Citation2022). In contrast, programs in our review that provided materials in both languages of instruction demonstrated positive outcomes (i.e. Senegal, Mali).

Community-related challenges

Community buy-in emerged as a significant challenge for bilingual education across the program profiles. In Niger, the student population of EE schools were from lower SES families. Higher SES families were apprehensive of bilingual education hampering their children’s French proficiency, compromising their entry into secondary school (Ilboudo Citation2010) and economic future (David-Erb Citation2021; Hovens Citation2002). Parents’ perceptions of local language instruction may not align with learning science evidence; they may not be aware of the benefits of bilingual instruction that includes a local language. Even when parents understand the benefits of a local LoI, they may consider the official language optimal because it opens the door to secondary school and the opportunity for socioeconomic mobility later in life (Bühmann and Trudell Citation2007; Cleghorn, Merritt, and Abagi Citation1989).

Senegal and Burkina Faso’s programs both included community engagement elements to change the negative perceptions of local languages in education. ARED actively educated families about the benefits of bilingual instruction (Benson Citation2020). Burkina Faso’s PEB program included adult literacy to engage parents in their child’s learning (Hanemann Citation2018). Mali does not directly target proximate community buy-in with program elements, but rather nudges this through the systemic intervention of the school exit exam being in both a Malian language and French (Bühmann and Trudell Citation2007). Of note is that PEB’s community engagement efforts do not appear as successful as ARED’s (Benson Citation2020; David-Erb Citation2021). There are critical community-level factors that differ between the communities in which these programs operated, which contributed to differences in the persistence of negative perceptions of local languages in education. These community-level factors should be considered when implementing a bilingual program.

Imagining effective bilingual education programs: implementation and socio-cultural supports are key

The studies in this review suggest that effective bilingual programs in and around Francophone West Africa are not limited to a specific immersion style. Children may benefit from learning in two languages regardless of the combination of languages (i.e. two official languages, one official/one local language) and the order in which the languages are presented (i.e. simultaneous or sequential; Benson Citation2020; Bühmann and Trudell Citation2007; Hanemann Citation2018; Takam and Fassé Citation2020). However, merely providing access to bilingual instruction does not guarantee learning benefits; engaging the community and addressing contextual factors that impede the availability of resources is critical for closing the gap between the written and enacted curriculum and delivering effective programs in this region. Therefore we forward two key elements for effective bilingual education in Francophone West Africa based on these nine case studies: implementation supports and sociocultural supports (). Crucial implementation supports include adequate teacher training and teaching/learning materials in all LoIs. Socio-cultural supports include initiatives to foster positive community perceptions of bilingual education, and community engagement in the programs.

In our review, a minimum of 20 languages were actively used throughout each country (see ). In highly multilingual contexts such as West Africa, it may be administratively-challenging to provide education in multiple languages to ensure children learn in their L1. Multilingual countries would need to (1) decide which languages to include in bilingual programs, (2) produce materials and a curriculum in each language, and (3) train teachers in multiple languages or specific local languages. Sans resources within the highly multilingual context of West Africa, teachers may resort to the official language, undermining the importance of bilingual instruction.

Bilingual education is typically more expensive at the start due to the cost of teacher training and developing teaching materials (Heugh Citation2011; Trudell Citation2016). These higher implementation costs may discourage widespread bilingual programs. On the one hand, in any context, high-quality bilingual education requires sufficient funding to be implemented effectively in schools. On the other hand, grade repetition is costly. Research suggests that grade repetition may be lower for children attending bilingual schools in West Africa (Ball et al. Citation2022; World Bank Citation2005; Zoungrana Citation2014); research from SSA and other low- and middle-income countries suggests that reducing the number of years it takes for children to complete primary school may lower a country’s long-term education costs, and the extra implementation costs for bilingual education may be recovered within a few years (Grin Citation2005; Patrinos and Velez Citation2009; World Bank Citation2005).

The locus of extra implementation costs matters. If the extra costs associated with bilingual education, such as books and materials (e.g. Cameroon; Takam and Fassé Citation2020), are borne by the children and their families, then poverty and low community SES may prevent children from accessing quality bilingual education. Nevertheless in West Africa, the ability for a child to learn in a language they already speak, and the potential learning benefits afforded to children through bilingual instruction, suggest bilingual education may be most beneficial for children who experience disadvantages in education due to their low SES (Hovens Citation2002). Therefore, bilingual education in West Africa must not be cost-prohibitive for low-SES families to ensure equitable learning opportunities, particularly for economically-vulnerable ethnolinguistic groups (Jasińska and Guei Citation2021).

Limitations

For some of the programs, we reviewed multiple studies that seemed to report contradictory findings. For example, Bühmann and Trudell (Citation2007) found that children in Pédagogie convergente schools outperformed their peers in traditional French schools on French language and literacy tests, while Sanogo (Citation2007) found that they performed worse on a writing task. Many of the studies assessed different educational metrics (e.g. primary school exit exam scores versus writing assessments) and pulled from different samples (e.g. national average exam scores versus children attending specific schools). Probing these details was outside of the scope of this paper. However, these seemingly contradictory findings further emphasize the need to consider the context of the bilingual education program; the same program might experience a range of successes and constraints depending on specific contextual and environmental factors across different communities or schools. Additionally, these results highlight the importance of considering educational metrics when evaluating bilingual education programs. Future research should clearly report the metrics used to assess the outcomes of bilingual programs. Thus, we recommend caution when considering how the successes and constraints of a program may generalize. Finally, we did not find literature fitting the inclusion criteria for all Francophone countries in the West African region, and the literature we did find was limited. It is important to continue to conduct research on bilingual education in Francophone West Africa to better understand how to improve education quality and learning outcomes in the region.

Conclusion

Bilingual education may indeed improve learning outcomes in Francophone West Africa, and beyond. However, bilingual programs do not universally produce favorable outcomes in challenging educational contexts; outcomes are highly context-dependent. What works in one country or community may not work in another, and bilingual programs may have similar features but different outcomes. To fully realize the benefits of bilingual education and improve children’s learning outcomes, it is essential to consider a broad range of factors including, but not limited to, those we forward in this review.

Social, cultural, and political factors and resource availability may shape the types of bilingual programs implemented, how programs are implemented, community perceptions, and ultimately, program outcomes. Community contexts, including community perceptions of the legitimacy of bilingual education and program accessibility, can significantly contribute to program effectiveness. Efforts should be made to reduce resource, participation, and community buy-in barriers that limit high-quality and accessible bilingual education.

Effective and high-quality bilingual programs require coordinated and comprehensive implementation efforts to provide teachers with training and materials, and reduce sociocultural barriers that threaten the legitimacy of bilingual education (e.g. exams in local languages; educating communities on benefits; involving communities in program design and evaluation). The instructional quality, consistency of language use, and resources to support learning play a significant role (Trudell Citation2016). If the quality and delivery of bilingual instruction are poor, then children’s language, literacy, and learning outcomes may not reflect the advantages expected from bilingual education. It is therefore essential to understand the factors that constrain and contribute to the success of bilingual programs if the goal of improving learning outcomes is to be realized.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (13.3 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank all of the members of the BOLD Lab team for their support and for providing thoughtful feedback on early versions of this manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mary-Claire Ball

Mary-Claire Ball is a PhD student in the Developmental Psychology and Education program at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education at the University of Toronto.

Jasodhara Bhattacharya

Jasodhara Bhattacharya is an EdD student in International Education Leadership and Policy at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education at the University of Toronto, and formerly a policy analyst at the Brookings Institution in Washington DC.

Hui Zhao

Hui Zhao is an MEd student in the Developmental Psychology and Education program at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education at the University of Toronto.

Hermann Akpé

Hermann Akpé is a professor at l'Institut des Sciences Anthropologique de Développement (ISAD) at l'Université Félix Houphouët-Boigny in Côte d'Ivoire (UFHB). He is responsible for the Education axis of the Science Society and Development laboratory of the Human and Social Science Training and Research Unit.

Stephanie Brogno

Stephanie Brogno is an undergraduate student in Psychology and Education at York University.

Kaja K. Jasińska

Kaja Jasińska is a developmental cognitive neuroscientist, Assistant Professor in Applied Psychology and Human Development at the University of Toronto, and Scientific Director of the Brain Organization for Language and Literacy Development (BOLD) Laboratory.

References

- AfCFTA Secretariat. 2022. “Republic of Côte d'Ivoire.” February 23. https://afcfta.au.int/en/member-states/cote-divoire.

- Akyeampong, K., K. Lussier, J. Pryor, and J. Westbrook. 2013. “Improving Teaching and Learning of Basic Maths and Reading in Africa: Does Teacher Preparation Count?” International Journal of Educational Development 33 (3): 272–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2012.09.006.

- Alidou, H. 1997. “Education Language Policy and Bilingual Education: The Impact of French Language Policy in Primary Education in Niger.” Doctoral diss., University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Amani-Allaba, A. S. 2016. Quand des Ivoiriens bouleversent et défient le français en Côte d'Ivoire. London: Éditions Universitaires Européennes.

- ARED. 2014. Dubai Cares Pro-Forma Proposal Outline: Support Project for Quality Education in Mother Tongues for Primary Schools in Senegal (Phase III: 2013–2018). Dakar: ARED.

- Baker, C. 2011. Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Ball, M.-C., E. Curran, F. Tanoh, H. Akpé, S. Nematova, and K. K. Jasińska. 2022. “Learning to Read in Environments with High Risk of Illiteracy: The Role of Bilingualism and Bilingual Education in Supporting Reading.” Journal of Educational Psychology 114 (5): 1156–1177. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000723.

- Benson, C. 2020. “An Innovative ‘Simultaneous’ Bilingual Approach in Senegal: Promoting Interlinguistic Transfer While Contributing to Policy Change.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 25 (4): 1399–1416. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2020.1765968.

- Brock-Utne, B. 2012. “Language Policy and Science: Could Some African Countries Learn from Some Asian Countries?” International Review of Education 58 (4): 481–503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-012-9308-2.

- Brou-Diallo, C. 2011. “Le Projet Ecole Intégrée (PEI), un embryon de l’enseignement du Français Langue Seconde (FLS) en Côte d’Ivoire.” Revue Électronique Internationale de Sciences du Langage Sud-langues 12: 40–51.

- Bühmann, D., and B. Trudell. 2007. Mother Tongue Matters: Local Language as a Key to Effective Learning (Report No.ED.2007/WS/56 REV). UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000161121.

- Chiatoh, B. A. 2014. “Community Language Promotion in Remote Contexts: Case Study on Cameroon.” International Journal of Multilingualism 11 (3): 320–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790718.2014.921178.

- Cleghorn, A., M. Merritt, and J. O. Abagi. 1989. “Language Policy and Science Instruction in Kenyan Primary Schools.” Comparative Education Review 33 (1): 21–39. https://doi.org/10.1086/446810.

- David-Erb, M. 2021. “Language of Instruction: Concerning Its Choice and Social Prestige in Burkina Faso.” International Review of Education 67: 435–449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-021-09885-y.

- Dutcher, N. 1982. The Use of First and Second Languages in Primary Education: Selected Case Studies (English) (Report No. SWP504). The World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/979911468780271883/The-use-of-first-and-second-languages-in-primary-education-selected-case-studies.

- Dutcher, N. 2001. Expanding Educational Opportunity in Linguistically Diverse Societies. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics.

- Eberhard, D. M., G. F. Simons, and C. D. Fennig. 2022. Ethnologue: Languages of the World. 25th ed. Dallas, Texas: SIL International. http://www.ethnologue.com.myaccess.library.utoronto.ca.

- Gfeller, E., and C. Robinson. 1998. “Which Language for Teaching? The Cultural Messages Transmitted by the Languages Used in Education.” Language and Education 12 (1): 18–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500789808666737.

- Grin, F. 2005. “The Economics of Language Policy Implementation: Identifying and Measuring Costs.” In Mother Tongue-Based Bilingual Education in Southern Africa: The Dynamics of Implementation, edited by A. Neville. Symposium Proceedings, University of Cape Town, 16–19 October 2003.

- Hanemann, U. 2018. Programme d’éducation bilingue, Burkina Faso. UNESCO Institute for Lifelong Learning. https://uil.unesco.org/fr/etude-de-cas/effective-practices-database-litbase-0/programme-deducation-bilingue-burkina-faso.

- Heugh, K. 2011. “Theory and Practice – Language Education Models in Africa: Research, Design, Decision-Making and Outcomes.” In Optimising Learning, Education and Publishing in Africa: The Language Factor. A Review and Analysis of Theory and Practice in Mother-Tongue and Bilingual Education in Sub-Saharan Africa, edited by A. Ouane and C. Glanz, 105–156. Hamburg: UNESCO Institute of Lifelong Learning.

- Hornberger, N. H. 1991. “Extending Enrichment Bilingual Education: Revisiting Typologies and Redirecting Policy.” In Bilingual Education: Focusschrift in Honor of Joshua A. Fishman on the Occasion of his 65th Birthday, edited by O. Garcia, 215–234. Vol. 1. Amsterdam/ Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/z.fishfest1.19hor

- Hovens, M. 2002. “Bilingual Education in West Africa: Does It Work?” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 5 (5): 249–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050208667760.

- Ilboudo, P. T. 2010. Bilingual Education in Burkina Faso: An Alternative Approach for Quality Basic Education. Case Studies Series No 11. Tunis: Association for the Development of Education in Africa (ADEA).

- Jasińska, K. K., Y. H. Akpé, A. B. Seri, B. Zinszer, R. Yoffo, K. Mulford, E. Curran, M.-C. Ball, and F. Tanoh. 2022. “Evaluating Bilingual Children’s Native Language Abilities in Côte D’Ivoire: Introducing the Ivorian Children’s Language Assessment Toolkit for Attié, Abidji, and Baoulé.” Applied Linguistics 43 (6): 1116–1142. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amac025.

- Jasińska, K., M.-C. Ball, and S. Guei. 2023. “Literacy in Côte d’Ivoire.” In Handbook of Literacy in Africa, edited by R. M. Joshi, C. A. McBride, B. Kaani, and G. Elbeheri, 235–254. Cham: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-26250-0_12.

- Jasińska, K. K., M. Berens, I. Kovelman, and L. Petitto. 2017. “Bilingualism Yields Language-Specific Plasticity in Left Hemisphere's Circuitry for Learning to Read in Young Children.” Neuropsychologia 98: 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2016.11.018.

- Jasińska, K., and S. Guei. 2021. “Ivory Coast: Promoting Learning Outcomes at the Bottom of the Pyramid.” In Learning, Marginalization, and Improving the Quality of Education in Low-Income Countries, edited by D. A. Wagner and N. M. Castillo, 343–360. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers.

- Jasińska, K. K., and L. A. Petitto. 2018. “Age of Bilingual Exposure is Related to the Contribution of Phonological and Semantic Knowledge to Successful Reading Development.” Child Development 89 (1): 310–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12745.

- Jasińska, K. K., S. Wolf, M. C. H. Jukes, and M. M. Dubeck. 2019. “Literacy Acquisition in Multilingual Educational Contexts: Evidence from Coastal Kenya.” Developmental Science 22 (5): e12828. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12828.

- Kim, Y. K., L. A. Hutchison, and A. Winsler. 2015. “Bilingual Education in the United States: An Historical Overview and Examination of Two-Way Immersion.” Educational Review 67 (2): 236–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2013.865593.

- Korgho, A. 2001. Etude comparative des coûts de formation entre les écoles classique et bilingue de Nomgana dans le département de Loumbila. Ouagadougou: OSEO.

- Kouame, K. J. M. 2007. “Les langues ivoiriennes entrent en classe.” Intertext 3–4: 99–106.

- Lavoie, C. 2008. “‘Hey, Teacher, Speak Black Please’: The Educational Effectiveness of Bilingual Education in Burkina Faso.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 11 (6): 661–677. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050802149275.

- Mafomene, M. B. 1996. “L’Impact de l’Ecole Bilingue sur les Performances Scolaires des El ves.” Unpublished doctoral diss., ENS. University of Yaound.

- Muskin, J. A. 1997. An Evaluation of Save the Children's Community Schools Project in Kolondieba, Mali. Washington, DC: Institute for Policy Reform.

- Muskin, J. A. 1999. “Including Local Priorities to Assess School Quality: The Case of Save the Children Community Schools in Mali.” Comparative Education Review 43 (1): 36–63. https://doi.org/10.1086/447544.

- Muthwii, M. J. 2004. “Language of Instruction: A Qualitative Analysis of the Perceptions of Parents, Pupils and Teachers among the Kalenjin in Kenya.” Language, Culture and Curriculum 17 (1): 15–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908310408666679.

- Ochoa, S. H., and R. L. Rhodes. 2005. “Assisting Parents of Bilingual Students to Achieve Equity in Public Schools.” Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation 16 (1–2): 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/10474412.2005.9669528.

- Organisation Internationale de la Francophonie. 2016. L’initiative ELAN-Afrique: de la vision à la salle de classe! http://observatoire.francophonie.org/qui-apprend-le-francais-dans-le-monde/reseaux-outils-formation-certificationdiffusion-francais/linitiative-elan-afrique/.

- Patrinos, H. A., and E. Velez. 2009. “Costs and Benefits of Bilingual Education in Guatemala: A Partial Analysis.” International Journal of Educational Development 29 (6): 594–598. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2009.02.001.

- Piper, B., and E. Miksic. 2011. “Mother Tongue and Reading: Using Early Grade Reading Assessments to Investigate Language-of-Instruction Policy in East Africa.” In The Early Grade Reading Assessment: Applications and Interventions to Improve Basic Literacy, edited by A. K. Gove, and A. Wetterberg, 139–182. RTI Press. https://doi.org/10.3768/rtipress.2011.bk.0007.1109

- Ruiz, R. 1997. “Bilingual Education.” In Honoring Richard Ruiz and his Work on Language Planning and Bilingual Education (2016), edited by N. H. Hornberger, 179–181. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Sanogo, K. 2007. “Patterns of French Literacy Development among Elementary Students in Mali.” Doctoral diss., Northern Arizona University. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- Tadadjeu, M. 2005. Language, Literacy and Education in African Development: A Perspective from Cameroon (Working Paper No. 7871). https://www.silcam.org/resources/archives/7871.

- Takam, A. F., and I. M. Fassé. 2020. “English and French Bilingual Education and Language Policy in Cameroon: The Bottom-up Approach or the Policy of No Policy?” Language Policy 19 (1): 61–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-019-09510-7.

- Traoré, C., C. Kaboré, and D. Rouamba. 2008. “The Continuum of Bilingual Education in Burkina Faso: An Educational Innovation Aimed at Improving the Quality of Basic Education for all.” PROSPECTS 38 (2): 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-008-9075-9.

- Trudell, B. 2016. The Impact of Language Policy and Practice on Children’s Learning: Evidence from Eastern and Southern Africa. Nairobi: UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/esa/sites/unicef.org.esa/files/2018-09/UNICEF-2016-Language-and-Learning-FullReport.pdf.

- UNESCO. 2006. Stratégie de Formation des Enseignants en Enseignement Bilingue Additif Pour les Pays du Sahel (doc. ED/2007/WS/45.). Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. 2020. Literacy Rate, Adult Total (% of People Ages 15 and Above) – Sub-Saharan Africa. UNESCO. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.ADT.LITR.ZS?locations=ZG.

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. 2021a, September. Literacy Rate, Adult Total (% of People Ages 15 and Above) – Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Côte D’Ivoire, Kenya, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Uganda. UNESCO. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.ADT.LITR.ZS?locations=BF-CM-CI-KE-ML-NE-SN-UG.

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. 2021b, September. Literacy Rate, Youth Total (% of People Ages 15–24) – Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Côte D’Ivoire, Kenya, Mali, Niger, Senegal, Uganda. UNESCO. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SE.ADT.1524.LT.ZS?locations=BF-CM-CI-KE-ML-NE-SN-UG.

- World Bank. 2005. In Their Own Language … Education for All. Education Notes. World Bank. http://hdl.handle.net/10986/10331.

- World Bank. 2021. The Wealth of Today and Tomorrow: Sahel Education White Paper Overview Report (English). Washington, DC: World Bank Group. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/099435112132125755/P17575201f11ec0070b02601176da5c497e.

- Zoungrana, B. W. 2014. “The Relationship of Teachers to National Languages, as Teaching Mediums and Subjects, in Bilingual Education in Burkina Faso.” Unpublished masters thesis. University of Human and Social Sciences.