ABSTRACT

This study offers an account of the coming out by Amy, a 20-year-old student of Japanese in Boston who has ‘been out to most’ as a cisgender lesbian woman, to Yoko, a 19-year-old student of English in Tokyo who experiences culture shock with Amy's revelation. The data originated from an exchange on Google Hangouts that was part of a US–Japan telecollaboration project. Our goal is to examine the impact of this coming-out event on the students’ experience of the virtual exchange and on their long-term cross-cultural understandings of LGBTQ+ issues and sexual diversity. We first analyze how Amy and Yoko managed the critical event discursively. We then examine the participants’ retrospections collected at the end of the project and again about 5 years later. We find that the two students co-constructed the coming-out event as one of transforming culture shock into a mutual opportunity for interpersonal bonding and intercultural learning. Nevertheless, they also reproduced stereotypical constructions of the US as a country that is open to sexual diversity and Japan as a country where queer lives are invisible. We call for the inclusion of LGBTQ+ identities and gender and sexuality diversity in language pedagogy and research.

1. Introduction

In the fields of TESOL and educational linguistics, a sizable body of scholarship has elaborated on the need and feasibility of a queer language pedagogy that places sexual diversity at the forefront of the educational endeavor (e.g. Banegas and Govender Citation2022; Coda Citation2017; Knisely and Paiz Citation2021). Heterosexism and cisgenderism (i.e. when heterosexual and binary identities, thinking, and norms are naturalized, and all other sexual personhoods are minoritized) are bad for language education. Sexual diversity must be centered in classrooms, Sauntson (Citation2019) among many has argued, because when students and teachers are imagined homogeneously cisgender, heterosexual, or even as ‘having no sexual identity’ at all (336), gender-diverse students are de facto excluded from the classroom community and denied equal opportunities for language learning. Moreover, the consequences of letting heteronormativity be ‘unruffled, untouched, and untroubled’ (Curran Citation2006, 94) are negative for all involved in language education – for the many language learners, teachers, and researchers who identify as nonbinary, gender non-conforming, gender-fluid, trans, or queer as much as for many others, including those who identify as cisgender and heterosexual allies, as we co-authors of this article do.

Yet, it is far from customary to see gender and sexuality included, theorized, and investigated in the field of second language acquisition (SLA). When it comes to research into the learning benefits of telecollaboration, defined as virtual exchanges that bring together language students from disparate geographical locations for linguistic and intercultural learning (O’Dowd Citation2021), neglect is also the norm. Indeed, to our knowledge, no telecollaboration study to date has investigated gender and sexuality as a topic for cultural learning or interpersonal negotiation. In the present study, sexual diversity serendipitously became the center of learning in a video-mediated virtual exchange that brought together thirty dyads of language students from Japan and the US (Akiyama Citation2018). During week 4 of the 9-week project, one student came out to her e-partner and self-identified as lesbian. Our analysis shows how the coming-out event was negotiated on the fly, over time cementing a personal bond and enhancing the students’ language and intercultural learning experiences – yet encouraging stereotypical constructions of the US as a country that is open to sexual diversity and Japan as a country where queer lives are invisible. We thus offer the present study as evidence of the importance to center critical thought about gender and sexuality in the intentional design of all language pedagogy and research.

2. Intercultural learning in telecollaboration

Telecollaborations have become widespread in the field of language education, and their benefits for linguistic and intercultural learning have been touted (Akiyama and Cunningham Citation2017). Of relevance for our present purposes is that most studies have reported that these virtual exchanges promote openness, empathy, and criticality when learning about other cultures (e.g. Helm and Acconcia Citation2019). Some degree of caution, however, has also been raised by Lee and Song (Citation2020) and O’Dowd (Citation2021). Both studies found that intercultural learning may be superficial, possibly because each student positions themselves as ‘ambassadors’ or ‘defenders’ of their native language and culture (O’Dowd, 10) and because no triangulation of cultural insights with multiple members of the same language community is possible (Lee and Song, 75–76).

Also relevant for our present study is that some telecollaboration scholars have captured flirting and the emergence of romantic relationships in their data (Belz and Kinginger Citation2002; González-Lloret Citation2008). However, these instances were noted by the researchers only in passing and both occurred within the confines of heteronormativity. Thus, if one reads the extensive literature on telecollaboration, one gets the impression that gender and sexuality fall outside the scope of what is learned, linguistically or interculturally, in virtual exchanges. This silencing is odd, since many other studies show that language students learn to manage their gendered and sexual identities in language education spaces, and they also actively seek the linguistic resources needed to perform their sexual identities and have them ratified in and through the new language.

3. Coming out (or not) in the language classroom

Coming out, or ‘the practice of revealing stigmatized sexual desire in a heteronormative cultural context’ (Zimman Citation2009, 54), has been the object of much multidisciplinary research. In language classrooms, both teachers and students who identify as sexual minorities must engage in often burdensome calculation about the risks and benefits of coming out.

In a rare study of the coming out of a language teacher, Leal and Crookes (Citation2018) mapped the complex calculations that made Jackson, a white cis middle-class queer woman teacher, quit her job in Korea after experiencing discrimination coupled with the intensely felt pressure to keep her queer identity private. Jackson later came out to her international students in the US when she felt teaching English through the content of LGBTQ rights provided her with a safe space to do so. In stark contrast with Leal and Crookes, Liddicoat (Citation2009) poignantly documented how many language teachers routinely ask seemingly innocuous questions that confront queer-identifying students with the decision to come out or not. These are questions designed to elicit personal information for the sake of oral language practice, such as: Sam, ¿cómo es tu novia? (‘Sam, what's your girlfriend like?’) (193). In responding, students must weigh their options either to pass as heterosexual, by issuing an invented answer that is untrue to their self, or to implicitly come out, such as when Sam responded: Mi novio es alto y delgado (‘My boyfriend is tall and slim’). In the latter case, students often see their identity statement unheard as such and instead treated as a linguistic failure that warrants grammatical correction: ¿alta y delgada? (‘tall and slim?,’ corrected from masculine to feminine grammatical gender). Through these occurrences, the burden is always on students if they decide to resist and render their queer identity legible by challenging their teachers.

Events like the ones captured by Liddicoat (Citation2009) are common (e.g. Moore Citation2019, 437) but rarely studied because, as Liddicoat (Citation2009) noted, ‘the revelation is not plannable as a research phenomenon because of its very spontaneity’ (192). The online modality of the curricular virtual exchange in the present study made it possible to fully capture and analyze such a spontaneous, unplanned revelation as data.

4. Learners’ constructions of gender and sexuality within and across national cultures

Past research shows that learners actively construct understandings about how target-language speakers and their national cultures orient toward a diversity of genders and sexualities.

Moore (Citation2023) investigated Teodora and Marie, two learners of Japanese who had resided in Japan for several years. Genderqueer pansexual Teodora had grown up in Romania, where they experienced extreme cisgenderist violence. Teodora found Japan liberating: ‘for me Japan is an incredibly open place’ (272). On the other hand, US-born Marie constructed Japanese society as slowly walking on the path toward progress on issues of sexuality-gender diversity and LGBTQ+ rights: ‘as far as Japan goes I mean I just think it's a cultural thing that's gonna get worked out over time … it's not there yet’ (269). In a very different case, Britton and Austin (Citation2023) offer the case study of Wesheng, a cisgender male-identified international student from China, enrolled in a freshman composition class in the US. When he experienced a text discussing trans oppression, Wesheng responded enthusiastically by exploring gender-neutral pronouns ‘sie/hir’ (rather than she/her or he/him binary pronouns) in his own writing. But he also was convinced that ‘Chinese people simply “don't talk” about “the freedom of sex”’ (11). Thus, each learner's past personal experiences growing up in a very different native country may incline them to embrace a different imaginary of attitudes toward sexual diversity in their own and other countries.

Brown (Citation2016) offers a case study of Julie, a 50-year-old learner of Korean from the US. Preparing to study abroad, Julie feared her carefully produced dykeFootnote1 identity, which in the US she achieved through short hair and an androgynous dressing style, would be culturally inappropriate in Seoul. She decided she would feminize her dressing and stay closeted while in Korea. She was dejected when she realized that her sexual identity was illegible to locals: ‘My appearance is challenging for the folks here, regardless of the lengths I went to look more feminine’ (817). She also became convinced that in Korea nobody is familiar with LGBTQ+ issues: ‘the whole dyke message is not received here’ (820). In sum, constructions of the target-language speakers and their national cultures involve interpretations of nonlinguistic cues in sexed bodies (e.g. dress, hairstyle, mannerisms), and these cues may be (il)legible cross-culturally.

5. The present study

The data in this study originated in a telecollaboration project designed and led by the first author, comprising 30 dyads of college students from Japan and the US (Akiyama Citation2018; approved by the Georgetown University Institutional Review Board, IRB# 2014-0921). In the fall of 2014, they met on Google Hangouts over 9 weeks and completed a series of cultural comparison tasks, loosely structured as conversations about each other's cultures supported by visuals that each chose for the sessions. We focus on one dyad, Amy and Yoko (pseudonyms). On week 4, when it was Amy's turn to choose a topic for cross-cultural comparison, she suggested ‘dating,’ which she found in the list of sample topics included in the syllabus. During this Google Hangouts conversation, Amy came out to Yoko. We first analyze the event discursively, and then offer a content analysis of their retrospections spanning about 5 years. We seek to answer the following questions:

How did the language learners negotiate the virtual coming out?

What impact did the coming out have on these language learners’ remaining telecollaboration experience?

How did it change, if at all, their understandings of LGBTQ+ issues and sexual diversity?

We acknowledge that our own lives and experiences as cisgender and heterosexual women have impacted what we are able to present here. Overall, we share a great deal more with Yoko, while remaining outsiders to Amy's lesbian identity. The first author, who collected all the data, was also an instructor of Japanese and the former facilitator of the virtual exchange experience. This is something that both Amy and Yoko likely oriented to in the retrospections they produced for us. While analyzing and interpreting the discourse data and the retrospective interviews, and while writing up this study, we continuously and critically sought to queer our gaze and look for multiperspectival insights, as LGBTQ+ allies whose good intentions have obvious limits.

6. Participants and data sources

Amy was learning Japanese in the US, and Yoko was learning English in Japan. They met on Google Hangouts on their own scheduled time and each from home, for about an hour each week, half of the session devoted to English and half to Japanese, always in this order. At the time, Amy was 20 years old, double-majoring in cultural anthropology and Japanese at her university in Boston. Yoko was 19, majoring in commerce at her university in Tokyo. Amy had studied Japanese for 2 years in her college in Boston. Yoko had studied English in Japan for 7 years, as part of regular compulsory education. Both self-described their proficiency as intermediate (and this was confirmed independently, see Akiyama and Saito Citation2016).

Amy and Yoko had much in common, including shared privileges conferred in their respective societies by their identities as young, educated, able-bodied females. Both were from upper-middle-class backgrounds, judging from the elite universities where they studied and the white-collar jobs they eventually held after college graduation. But they were also quite different people. In terms of ethno-racial identities, Amy was Caucasian and Yoko Asian. Amy seemed more cosmopolitan. For example, she had a brief but formative visit to Japan during high school and had kept in touch with her host family since then. By comparison, Yoko had never been abroad when the virtual exchange started. In fact, she had never spoken English outside the classroom. Nevertheless, she seemed to be interested in languages and cultures. For instance, she took 3 years of Spanish in college. As for their sexual identities, Amy was an out gay woman: ‘I’ve been out to most since I was 13, and fully FULLY out since I was 18’ (2019, interview). She believed her lesbian identity has always been visible (‘obvious’) to all since high school. Now in college, she often dyed her hair rainbow. Yoko was a cisgender heterosexual woman and, at the time of the virtual exchange, she positioned herself as wholly unfamiliar with LGBTQ+ issues and never having met a gay person.

We draw from four sources of data. Three were collected in 2014: (1) Yoko and Amy's video-recorded interactions on Google Hangouts, (2) weekly reflective journal entries written immediately after each session, and (3) 20-minute-long interviews in English (with Amy) and Japanese (with Yoko) conducted by the first author immediately after the completion of the project. The fourth data point comes from Zoom interviews conducted also by the first author in 2019, about 5 years later, for 90 min with Amy (in English) and 45 min with Yoko (in Japanese). Following the interactional sociolinguistic tradition of playback, in 2019 we had Amy and Yoko each watch the video clip of the coming-out event to refresh their memories (see the Supplementary Material for the interview questions).

7. How did the language learners negotiate the virtual coming out?

This section examines the discourse evidence by analyzing two excerpts from Session 4. Our transcription uses multimodal discourse analysis conventions in the column style (see Appendix A). This resembles the camera configuration of Google Hangouts recordings, where only one speaker was captured via automatic voice detection. Multimodal moves that seemed particularly important for the analysis, such as gaze, hand gestures, head tilts, and facial expressions, have been captured via screenshots and inserted into each line. Japanese utterances are given together with the English translation in italics.

7.1. I live with my GIRLfriend (彼女)

Amy's coming out revelation is shown in Excerpt 1. Having chosen dating, at Amy's suggestion, as their theme for cultural comparison on week 4, the dyad had spent the first 34 min in English, talking about activities that couples often do on a date. Excerpt 1 begins at the closing of the English half, as Amy and Yoko are transitioning into Japanese.

Amy casually asks Yoko if she has a boyfriend (line 1). Yoko stalls a bit, but in line 4 intimates to Amy that she broke up with her boyfriend 3 months ago. This is the kind of empathic moment (Heritage Citation2011) that obligates an interlocutor to affirm the experiencer's revelation. Over the next ten turns, this is exactly the kind of affiliative work we see in Amy. In line 5, she displays warm sympathy toward Yoko by switching momentarily to English (Oh oh that's sad) while covering her mouth with her right hand, a gesture that can potentially be read as Japanese. The coupling of a codeswitched English utterance with a Japanese-like gesture evinces translanguaging as a resource that intensifies the empathic moment. Amy then returns to Japanese to show her concern in line 7 (悲しい? Are you sad?). The revelation of Yoko's breakup concludes in line 13 with a half-laughing, half-embarrassed wish by Yoko that she might find somebody new soon, and in line 14, Amy supports the wish.

In line 15, Yoko acknowledges the supportive comment but also closes the revelation of her breakup by redirecting the same question to Amy: Amy は?(What about you, Amy?). In doing so, Yoko fulfills the shared expectation of mutual revelation (Tannen Citation2005), when a statement of personal experience by one interlocutor is responded with another statement of personal experience by the other. Yoko's question triggers Amy's declaration that she is in a same-sex relationship: 彼女と住んでいる (I live with my girlfriend) (line 16). Amy accomplishes this using various multimodal resources. She points her finger up to show where her girlfriend Katie is (they lived in a two-story townhouse and Amy was chatting from the common area on the first floor) (line 16). She also emphasizes the second part of the word 彼女 (GIRLfriend), which means ‘woman’ in Japanese, through stress and a head thrust (line 17). Yoko, however, shows confusion at Amy's declaration in lines 17 and 18, as indicated by her repetition of the word 彼女 (girlfriend), hesitation markers (e.g. ‘uh,’ ‘eh’), widening of her eyes, deep nodding, and gaze aversion. In response, Amy provides additional evidence for her statement by saying it has always been a girlfriend since high school (line 19). In line 20, Yoko ponders on the word 彼女 (girlfriend) for 3.4 s, looking up while scratching her face, as if momentarily forgetting that she was talking with Amy, but later comes back to the conversation as shown by the Japanese change-of-state token ‘Ah.’ In line 21, Amy laughs at Yoko's surprised face and changes the topic back to talking about Yoko's ex-boyfriend, asking how long they dated (Yoko's response, not shown in the transcript, was ‘7 months’).

Excerpt 1. I live with my girlfriend (彼女).

For reasons of space, we summarize here what happened approximately 30 min after the coming-out event just shown. With the virtual meeting of the week completed and their usual leave-taking routine initiated, Yoko suddenly asked Amy: あともう一個、質問。(One more question), and she reintroduced the topic of dating by asking Amy in English if it is common for ‘women to date women’ in the US. Amy explained that people's perception of gay persons often varies depending on which part of the US they are from, although it does seem that people across the country are becoming more understanding of same-sex relationships these days. This was followed by Excerpt 2, analyzed in the next section.

7.2. Culture shock

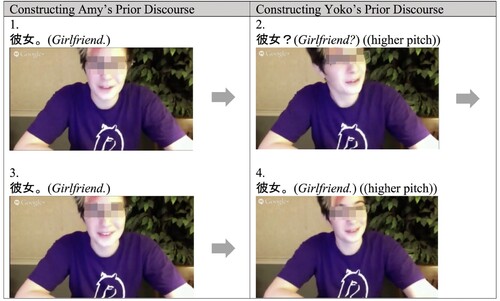

Excerpt 2 begins when Amy redirects Yoko's question of how common it is for ‘women to date women’ in the US and asks her: ‘How about Japan.’ Yoko states that ‘it is not not common? yet?’ (line 2) but adds her own supportive opinion: ‘I think it is ok’ (line 6), positioning herself as a transcultural individual who disavows the heteronormative ideology prevalent in Japan. Overlapping with Amy expression of gratitude to Yoko for her support for sexual diversity (‘Thank you,’ line 8), Yoko goes on to share with Amy her feelings when Amy came out earlier in the session, explaining with a smile that she was ‘a little surprised’ (line 8). Amy is startled to hear Yoko was surprised, as indicated by ‘AH’ (line 9), and asks why (line 11). Yoko says that she experienced culture shock (line 12). The ascription of her surprise to a cultural difference helps mitigate what might be seen as a homophobic reaction. In response, Amy both normalizes her gay identity and combats heteronormativity by saying, animated with laughter, ‘There are a LOT of gay people in Boston’ (line 16) and adding ‘So it's really really normal here’ (line 17). She, however, immediately shows empathy toward Yoko and reissues her acceptance of Yoko's culture shock explanation by laughingly adding, ‘But I can see uh I can see that it would be surprising’ (line 18). She apologizes for not having thought of warning Yoko (lines 19 and 21). Her repetition of ‘warning,’ in addition to their extended laughing together, suggests a change in the tone of the interaction and that Amy is in a play frame and is feeling amused. In line 22, Amy starts waving her left hand as if fanning to cool down the face heat caused by embarrassment, and almost simultaneously Yoko joins her in mirroring the same fanning gesture with her right hand, in the same rhythm, both laughing in what may be an affective peak achieved through co-gesturing (Katila and Philipsen Citation2019). In line 23, Amy then launches into an aside episode of reported speech of the word 彼女 (girlfriend). Here, as shown in , she re-enacts her own production of the word and Yoko's reaction to it, as well as Yoko's gestures, based on their prior discourse of coming out in Excerpt 1, lines 17–20. She uses the higher pitch and head tilts with a confused look to represent Yoko, while using the lower pitch and a straight head position to represent herself. This is a reported speech event achieved through what Tannen (Citation2005) calls constructed dialogue – not a verbatim quote but resembling Yoko and Amy's prior exchange enough to let them access the shared memory and give them a big laugh (lines 23–24). As such, the word 彼女 (girlfriend) became the token for their interactive achievement of coming out and contributed to repairing Yoko's lack of uptake and affiliation after Amy came out 38 min earlier. By Amy concluding the session with a humorous comment in ironic intonation (‘What a fun morning,’ line 24), amidst extended joint laughter, the two co-aligned to doing friends, also ratifying Amy's acceptance of Yoko's cultural shock explanation and deflection of homophobic attribution.

Figure 1. Amy's reconstructing the coming-out episode.

Excerpt 2. Culture shock.

Table

The conclusion that Amy's coming out was negotiated on the fly in ways that can be considered successful is further supported in the respective journal entries written by both students immediately after Session 4. Amy wrote:

Today's session was […] a really good learning atmosphere, and we both felt comfortable, which I could tell because at the end of our session, Yoko felt comfortable enough to ask me about how common gay relationships are here, and even told me she was surprised (though not bothered) when I said I had a girlfriend. It's entertaining and sweet because I think this was the first time she had a culture shock from these communications because I suppose she wasn't expecting that. (Amy, journal entry, week 4)

I noticed there are so many cultural differences about ‘love.’ I felt culture shock, but I want to understand American culture more. I enjoyed today's topic more than any other topics! (Yoko, journal entry, week 4)

8. What impact did the coming out have on the remaining telecollaboration experience?

In the remaining five interactions on Hangouts and the corresponding journal entries, we found no mention of the critical event, nor of gender and sexuality as a topic. However, we traced some lasting changes that suggest the coming out episode became a personal and learning turning point for the dyad.

In their interactions after week 4, Amy and Yoko focused on personal topics and frequently deployed resources for intersubjectivity that had rarely been observed prior to Session 4, such as code-switching, translanguaging, and jointly looking up online dictionaries. Their journal entries changed, too. Those written for Sessions 1–3 had been filled with notations about struggles in speaking the target-language and correcting their partner's errors. After Sessions 5 through 9, the reflective journals instead contained many comments about cultural differences and similarities. Drawing from Goffman’s (Citation1974) notion of frame or people's sense of what they are doing in a given interaction, we interpret these combined changes as evidence that, up until Session 3, Yoko and Amy had co-oriented to a ‘doing language teaching and learning’ frame, and after Session 4 they foregrounded the interactive frame of ‘doing cultural exchange.’

In the 2014 interviews immediately after the completion of the 9-week project, both students – independently and without being prompted – brought up the coming-out event. They both noted that sharing ‘such a private matter’ (Yoko) and ‘something so personal’ (Amy) built closeness and trust between them from that point onwards: ‘We’d gone beyond some of the superficial stuff, you know? Actually getting to know each other’ (Amy 2014, interview). The personal bond they described carried Yoko and Amy beyond the curricular sphere of Google Hangouts. After week 4, they began exchanging frequent messages via Facebook Messenger. After the project ended, they continued meeting on Google Hangouts, now for their own non-school sponsored learning purposes, for an extra five sessions. Later we also learned that in the summer of 2015, while Amy was studying in Kyoto and traveled to Tokyo for sightseeing, the two made plans and met in person over lunch.

In sum, Amy's coming out and their mutually empathic negotiation impacted the rest of the virtual exchange experience in positive ways. It enhanced the learning goals for intercultural engagement and strengthened interpersonal bonds well beyond the curricular boundaries.

9. How did the virtual coming out change Yoko and Amy's understandings of LGBTQ+ issues and sexual diversity?

We interviewed Amy and Yoko again in 2019, about 5 years after the telecollaboration project ended. Yoko told us that, inspired by the telecollaboration project, she had finally gone abroad for the first time, spending a semester at a university on the US East Coast in 2015. Upon her return and graduation, she took up a job at an electricity company in the western part of Japan. She was in a long-distance, heterosexual relationship with a former college friend who lived in Tokyo. On her part, we learned from Amy that she had spent a summer abroad in Kyoto in 2015 (when she met Yoko in person), and she also went on to graduate. She became an instructional support staff at a university language center. She had married her long-time girlfriend Katie, with whom she was living in Boston during the virtual exchange. We learned that neither Yoko nor Amy had kept up with their languages due to their busy lifestyles. Both also reported they had lost touch with each other, although both said they think fondly of the other, and they are still friends on Facebook, where they have exchanged friendly, casual messages once or twice.

Although 5 years had passed, each former student cheerfully reminisced over the coming-out event and had a lot to say about their understandings of sexual and gender diversity in a cross-cultural perspective. We present the evidence here for each student separately. The source for these data is the 2019 interviews, and Yoko's excerpts have been translated from Japanese into English by the first author.

9.1. Yoko

Five years after the virtual exchange project, Yoko reissued for the interviewer the same explanations of surprise and culture shock she had offered to Amy in Excerpt 2 at the time:

Probably, there were people like her around me, but I had never experienced someone coming out to me … So, I was really surprised. But, I thought, “Well, it's just a cultural difference.” I figured things were probably different in America. (Yoko 2019, interview)

As a freshman, my knowledge about same-sex relationships was quite limited. But, after this Hangouts [experience], I began to meet people like this, even among my friends. I also started to hear more about it at my university. So, this made me realize that maybe I just hadn't been aware of it before. I thought it was becoming more common in Japan, too. Like one of my college friends – a girl, but she is not a lesbian. She can go both-either way? (Yoko 2019, interview)

I'm not sure if it [the number of LGBTQ people] actually increased or if I became more interested and cared more about it. I don't know which is the case. (Yoko 2019, interview)

9.2. Amy

In 2019, Amy explained her approach in the self-revelation to Yoko on week 4 was ‘natural’: ‘It was more, “I’m living with my partner who happens to be a girl, by the way” […] It's yeah. It was natural.’ This narrativization of her coming out for us is consonant with her overall portrayal of her native US as a place where, overall, being queer is ‘completely fine’ and ‘not a big deal.’ This can be interpreted as her wanting to ‘normalize her nonheteronormative identity and emphasize her own agency’ for the researcher, as Moore (Citation2019, 439) noted. Be that as it may, when asked if it had been difficult to come out using Japanese rather than English, Amy remembered no difficulty. To the contrary, she seemed to have been highly practiced in it, telling us that early in her experience of Japanese classes in the US she had learned ‘how to indicate that my partner was a female,’ precisely in the context of practicing question–answers during pair work. Amy felt confident that she could negotiate her sexuality in Japan and in Japanese.

While Amy reproduced for us the same account she had issued to Yoko during Session 4 of a ‘queer-friendly’ country where large cities like Boston are ‘extremely accepting,’ after the playback of the critical event in 2019, she seemed to worry about what she had told Yoko, orienting to the danger to convey an untrue image of the US:

Like I didn't want her to get the impression that everywhere in America, like, women going out with women is typical. […] Compared to even other cities, Boston is very queer-friendly. Um, but and any city will be usually better than pretty much any not city. I think what I was getting at is that there are sub-parts in America that were like much more accepting of it, and some that maybe weren't. (Amy 2019, interview)

I think what was most surprising to me was that even looking as I do, she was like, “What do you mean?” So the, the way that I’m read here is not how I was gonna be read in Japan – which wasn't innately a good or a bad thing. It was just a thing. […] it did teach me that it wouldn't be an assumption about me there. (Amy 2019, interview)

The telecollaboration experience and Yoko's performance of culture shock seem to have contributed to Amy's construction of LGBTQ+ attitudes in Japan. Her own construction of how Japan fares in terms of gay-friendliness versus hostility was cautiously positive: ‘my understanding is that Japan is not extremely homophobic.’ She explicitly associated change with the US and stasis with Japan, when she recalled hearing the news of the historic striking down of all state bans on same-sex marriage by the US Supreme Court in June 2015: ‘It was like, wow. I was in Japan that summer. Um, so things do change [in the US]. Japan, I haven't heard of much changing.’ She immediately admitted: ‘but I also I haven't been keeping track of it.’ She described LGBTQ+ news around the world as being ‘on the periphery of my awareness.’ Amy is more invested in LGBTQ+ developments in the country where she lives, the US, rather than any other country. Nevertheless, even 5 years later, and after having lived in Kyoto for one summer, Amy continued to accept Yoko's claim that same-sex relationships are unfamiliar to Japanese people, when Yoko had said ‘in Japan it is not not common? yet?’ (Excerpt 2, line 2).

10. Implications and concluding thoughts

Having presented our analyses of the evidence, let us summarize the lessons learned. We found that when gender and sexuality serendipitously arose in the sponsored language learning activity, the coming-out revelation turned into a ‘safe, positive, and queering moment’ (Goldstein, Russell, and Daley Citation2007). It opened up the curricular space for Amy and Yoko to make sexual diversity visible, legible, speakable, and accepted. It amplified interpersonal bonding and intercultural engagement for the two students, enhancing the remaining of their telecollaboration experience. However, rather than together challenging heteronormativity, Amy and Yoko reproduced stereotypical constructions of the US as a country that is open to sexual diversity and Japan as a country where queer lives are invisible. In terms of long-term cross-cultural understanding of LGBTQ+ issues and sexual diversity, we found some evidence in Yoko of awakening toward the visibility and thus existence of sexual diversities in her native Japan. Other than that, 5 years later both Yoko and Amy seemed content with the co-construction that emerged from their critical virtual interaction of a progressive West that is for the most part ‘extremely accepting’ of nonnormative sexualities and an East that is ‘not extremely homophobic’ and is slowly on the path to progress but is not there ‘yet.’ Thus, despite the successful resolution of the coming out event and the positive emotions it brought into Yoko's and Amy's telecollaboration experience, a lesson these students did not learn is that cultural differences in how gender diversity is approached by nation-states and the individuals in them cannot be reduced to fixed dichotomies of progressivity versus backwardness, or visibility and tolerance versus invisibility and hostility.

What can language educators do when designing and implementing virtual exchanges in order to make deep cross-cultural learning more likely? We feel queering telecollaboration projects is the answer. Two key strategies for queering telecollaborations stand out as eminently feasible. One strategy is an audit of all pedagogical decisions at the point of designing the virtual exchange – from how to match partners, to suggestions for topics for discussion, to choice of texts and tasks – to ascertain that they support all-gender inclusive and affirming pedagogy. Does partner matching either reify or help students challenge the elevation of binary and cisgender experiences as universal? How will topics, texts, and tasks help students experience gender-expansive representations of the two target languages and cultures? How will such choices foster an understanding of gender diversity as intersectional with other identities (e.g. race, religion) and fluid? Ensuring that in intercultural projects like telecollaboration diverse sexual orientations and gender identities are included in topics, texts, and tasks in both target languages can go a long way in skirting cultural essentialism while making sexual minority students feel seen and included and making sexual majority students aware of sexual and gender diversity.

The second strategy for queering virtual exchanges pertains to pedagogical mentoring by teachers or project coordinators, an element of well-designed telecollaborations (O’Dowd, Sauro, and Spector-Cohen Citation2020). In the present curricular experience, we implemented pedagogical mentoring through a pre-project training module in which students in both sites were given tips for how to interact in ways that support each other's learning of language (e.g. by issuing recasts or asking their partner for new words). We neglected to include any pre-training on how to be effective intercultural communicators. Yet, as our findings show, pre-training should include some explicit learning of language for talking about gender diversity and gendering one's language, and some explicit awareness raising of the use and tensions surrounding nonbinary pronouns and of the ways in which language and body together are implicating in fashioning and negotiating gender identities through cues that may be transculturally (il)legible (e.g. Amy's rainbow-dyed hair). Ensuring that in telecollaboration this training for gender diversity is done bilingually, for both languages, in both sites, can greatly support this work since, as we have shown, it is important to be able to disrupt essentializing notions of ‘cultural differences’ and to avoid reducing gender diversity to something that is welcome in some languages, cultures, and nation-states, and alien in others. Moreover, learners need to be mentored in their understanding that contradictions abound. In so-called progressive countries, thriving LGBTQ+ activism and legal victories coexist with persistent systemic discrimination (e.g. in the UK vs. Brazil, Sauntson et al. Citation2022) and, conversely, in so-called traditional countries, heteronormativity is visibly dominant while also actively challenged (e.g. according to the nation-presentative LGBT surveys that Dentsu Inc. has been conducting in Japan since 2012, an estimated 8.9% of the Japanese population identifies as a sexual minority and another 29% are active LGBTQ+ supporters because they have ‘members of social minorities in their lives’ and/or have access to ‘information outside Japan’; Dentsu Citation2020, no page). We caution that the queering of telecollaboration projects can only happen if the virtual exchange is co-constructed as a safe place, where students are welcomed to explore sexual diversity as a topic and as a language learning issue.

Queer language pedagogy scholars have warned how ‘heteronormativity, or the presentation of cisgender, White, monogamous, reproductive, able-bodied, straightness as natural, normal, and desirable, perpetuates marginalization and violence both in and out of the language classroom’ (Knisely and Paiz Citation2021, 30). They have also fleshed out how all-gender affirming education can become a reality in every language classroom (e.g. Banegas and Govender Citation2022; Coda Citation2017; Knisely and Paiz Citation2021). It is therefore incumbent upon all language educators to strive to create inclusive curricular environments by design. Further, when teaching for intercultural competence, the dangers of cultural essentialism and even nationalistic retrenchment are real, because we can expect that without pedagogical guidance students will miss the fraught complexity that characterizes – regardless of nation, culture, or language configurations – the ‘relations among gender, sexuality, modernity, construction of national identity and queer activisms’ (Kawasaka Citation2018, 594). In particular, designers of virtual exchanges, which seek to engender language and intercultural learning through semi-supervised, autonomous peer interaction, must guard against these dangers, making visible that sexual and gender identities are nonbinary, and helping all students to positively affirm this reality by engaging them in critical cross-cultural work. The study of Amy and Yoko is a cautionary tale. We hope their story offers convincing evidence for many more language educators and SLA researchers to take action and center critical thought about gender and sexuality in the intentional design of not only all virtual exchanges but all language pedagogy and research.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (26.1 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our heartfelt thanks to Professor Kazuya Saito, our partner in the telecollaboration project, for his continuous and unwavering support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yuka Akiyama

Yuka Akiyama is Lecturer (Assistant Professor with tenure) at the University of Tokyo. Her research focuses on the use of technology for language teaching and learning and in support of intercultural communication, particularly in the context of telecollaboration, also commonly referred to as virtual exchange or COIL (Collaborative Online International Learning). She has used various theoretical and methodological frameworks to uncover the complexities of telecollaboration. Notably, in collaboration with Kazuya Saito, she has conducted a series of studies showcasing how video-medicated telecollaborative interactions foster the development of second language comprehensibility (published in Modern Language Journal, 2016; Language Learning, 2017; TESOL Quarterly, 2018). She has also highlighted the social aspects of error correction behavior in telecollaborative interactions (published in System, 2017), synthesized two decades of telecollaborative practices (published in CALICO Journal, 2018), and employed interactional sociolinguistics concepts and multimodal discourse analysis techniques to examine telecollaborative participants’ social actions (published in Language and Intercultural Communication, 2017). Her recent and on-going projects include a study investigating the relationship between task engagement and L2 comprehensibility development and a study on the role of eTandem in promoting awareness of linguistic and cultural diversity. Email: [email protected].

Lourdes Ortega

Lourdes Ortega is Professor of Linguistics at Georgetown University. Her research focuses on usage-based, multilingual, and social justice dimensions of second language acquisition, particularly in adult classroom settings. She has published widely, including in CALICO Journal (2017), Modern Language Journal (2019), Language Learning (2020), and Studies in Second Language Acquisition (2022). Recent and on-going projects include a 2023 special issue in the journal Applied Linguistics on decolonial and southern theories, guest co-edited with Anna De Fina and Marcelyn Oostendorp, and a study of critical language awareness and professional identity among teachers of Arabic in k-12 schools in the US, carried out with Hina Ashraf, Rima Elabdali, and Saurav Goswami.

Notes

1 In choosing to use ‘dyke’ to refer to herself, Julie was reclaiming a slur that some readers may find offensive.

References

- Akiyama, Y. 2018. “Reciprocity in Online Social Interactions: Three Longitudinal Case Studies of a Video-Mediated Japanese-English ETandem Exchange.” Doctoral diss., Georgetown University. DigitalGeorgetown. https://repository.library.georgetown.edu/handle/10822/1050805.

- Akiyama, Y., and J. D. Cunningham. 2017. “Synthesizing the Practice of SCMC-Based Telecollaboration: A Scoping Review.” CALICO Journal 35 (1): 49–76. https://doi.org/10.1558/cj.33156.

- Akiyama, Y., and K. Saito. 2016. “Development of Comprehensibility and Its Linguistic Correlates: A Longitudinal Study of Video-Mediated Telecollaboration.” The Modern Language Journal 100 (3): 585–609. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12338.

- Banegas, D. L., and N. Govender, eds. 2022. Gender Diversity and Sexuality in English Language Education: New Transnational Voices. London: Bloomsbury.

- Belz, J., and C. Kinginger. 2002. “The Cross-Linguistic Development of Address Form Use in Telecollaborative Language Learning: Two Case Studies.” The Canadian Modern Language Review 59 (2): 189–214. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.59.2.189.

- Britton, E. R., and T. Y. Austin. 2023. “Learning and Teaching Trans-Inclusive Language and Register Hybridity for Multilingual Writers.” Language Awareness. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2023.2211803.

- Brown, L. 2016. “An Activity-Theoretic Study of Agency and Identity in the Study Abroad Experiences of a Lesbian Nontraditional Learner of Korean.” Applied Linguistics 37 (6): 808–827. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amu075.

- Coda, J. 2017. “Disrupting Standard Practice: Queering the World Language Classroom.” Dimension 53: 74–89.

- Curran, G. 2006. “Responding to Students’ Normative Questions about Gays: Putting Queer Theory into Practice in an Australian ESL Class.” Journal of Language, Identity & Education 5 (1): 85–96. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327701jlie0501_6.

- Dentsu Inc. 2020. “2020 LGBTQ+ Survey.” Retrieved September 5, 2022, from https://www.dentsu.co.jp/en/news/release/2021/0408-010371.html.

- Goffman, E. 1974. Frame Analysis. New York: Harper & Row.

- Goldstein, T., V. Russell, and A. Daley. 2007. “Safe, Positive and Queering Moments in Teaching Education and Schooling: A Conceptual Framework.” Teaching Education 18 (3): 183–199. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210701533035.

- González-Lloret, M. 2008. “Computer-Mediated Learning of L2 Pragmatics.” In Vol. 30 of Investigating Pragmatics in Foreign Language Learning, Teaching and Testing, edited by E. A. Soler and A. Martínez-Flor, 114–132. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

- Helm, F., and G. Acconcia. 2019. “Interculturality and Language in Erasmus+ Virtual Exchange.” European Journal of Language Policy 11 (2): 211–233. https://doi.org/10.3828/ejlp.2019.13.

- Heritage, J. 2011. “Territories of Knowledge, Territories of Experience: Empathic Moments in Interaction.” In The Morality of Knowing in Conversation, edited by T. Stivers, M. Lorenza, and J. Steesing, 159–183. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Katila, J., and J. S. Philipsen. 2019. “The Intercorporeality of Closing a Curtain: Sharing Similar Past Experiences in Interaction.” Pragmatics & Cognition 26 (2–3): 167–196. https://doi.org/10.1075/pc.19030.kat.

- Kawasaka, K. 2018. “Contradictory Discourses on Sexual Normality and National Identity in Japanese Modernity.” Sexuality & Culture 22 (2): 593–613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-017-9485-z.

- Knisely, K. A., and J. M. Paiz. 2021. “Bringing Trans, Non-Binary, and Queer Understandings to Bear in Language Education.” Critical Multilingualism Studies 9 (1): 23–45.

- Leal, P., and G. V. Crookes. 2018. ““Most of My Students Kept Saying, ‘I Never Met a Gay Person’”: A Queer English Language Teacher’s Agency for Social Justice.” System 79: 38–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2018.06.005.

- Lee, J., and J. Song. 2020. “The Impact of Group Composition and Task Design on Foreign Language Learners’ Interactions in Mobile-Based Intercultural Exchanges.” ReCALL 32 (1): 63–84. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344019000119.

- Liddicoat, A. J. 2009. “Sexual Identity as Linguistic Failure: Trajectories of Interaction in the Heteronormative Language Classroom.” Journal of Language, Identity & Education 8 (2–3): 191–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348450902848825.

- Moore, A. R. 2019. “Interpersonal Factors Affecting Queer Second or Foreign Language Learners’ Identity Management in Class.” The Modern Language Journal 103 (2): 428–442. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12558.

- Moore, A. R. 2023. ““[It] Changed Everything”: The Effect of Shifting Social Structures on Queer L2 Learners’ Identity Management.” Journal of Language, Identity & Education 22 (3): 262–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2021.1874383.

- O’Dowd, R. 2021. “What Do Students Learn in Virtual Exchange? A Qualitative Content Analysis of Learning Outcomes across Multiple Exchanges.” International Journal of Educational Research 109: 101804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2021.101804.

- O’Dowd, R., S. Sauro, and E. Spector-Cohen. 2020. “The Role of Pedagogical Mentoring in Virtual Exchange.” TESOL Quarterly 54 (1): 146–172. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.543.

- Sauntson, H. 2019. “Language, Sexuality and Inclusive Pedagogy.” International Journal of Applied Linguistics 29 (3): 322–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijal.12239.

- Sauntson, H., R. Borba, C. Sink, and W. Ping Ho. 2022. “Silence and Sexuality in School Settings: A Transnational Perspective.” In The Bloomsbury Handbook of Solitude, Silence and Loneliness, edited by J. Stern and M. Walejko, 174–188. London: Bloomsbury.

- Tannen, D. 2005. Conversational Style: Analyzing Talk among Friends. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Zimman, L. 2009. “‘The Other Kind of Coming Out’: Transgender People and the Coming Out Narrative Genre.” Gender and Language 3 (1): 53–80. https://doi.org/10.1558/genl.v3i1.53.