ABSTRACT

The interaction between multilingualism and emotions has so far mostly been researched in Northern contexts. The findings obtained suggest that the first language is typically preferred for emotional and mental activities (i.e. ‘first language primacy’). In this article, we extend this area of investigation to Africa. We use the Bilingualism and Emotions Questionnaire to probe first language primacy in South Africa, employing a novel analytical approach – multiple correspondence analysis – that allows us to examine the relationship between particular languages and their order of acquisition. Our findings, in part, do reflect favouring of the L1, but with two important qualifications. First, English is also widely used for emotional expression in non-intimate domains. Second, L1 isiXhosa speakers prefer English for mental calculations, and isiXhosa is generally not associated with positive emotional characteristics. We explain these trends in relation to the multilingual context of South Africa, which, like many postcolonial countries, uses a former colonial language extensively in formal institutional spaces.

Introduction

Language plays an important role in the expression and construal of emotions (Besnier Citation1990; Martin Citation2000; Ochs and Schieffelin Citation1989), while emotions also affect people’s language learning trajectories and affinities to language (Kramsch Citation2006; Richards Citation2022; Swain Citation2013). Recently, the effects of multilingualism on how emotions are linguistically expressed, perceived, and experienced have been investigated (Dewaele Citation2011; Pavlenko Citation2005, Citation2006a, Citation2006b). The findings suggest that multilingualism may interact with emotions in various ways. The focus of the present paper is one particular finding: namely, the first language (L1) learned by a multilingual is often the preferred language for emotional expression and for inner speech (e.g. Pavlenko Citation2004; Dewaele Citation2004b). This phenomenon is known as ‘L1 primacy’.

Research on L1 primacy has, however, mostly been conducted in Western contexts and with European languages. Typically, multilingual participants resident in Africa are not included in such studies, and African languages rarely feature in the constellation of languages investigated in this paradigm. This is an important shortcoming, considering that multilingualism in Africa differs in some important respects from multilingualism in Europe and North America (see Banda Citation2009; Myers-Scotton Citation1993; Oostendorp Citation2012). In the latter regions, multilingualism is often treated as an individual characteristic that develops either out of choice (so-called ‘elective multilingualism’) or through migration. Multilingualism in Africa, on the other hand, often entails the use of the former colonial languages together with local African languages in multilingual settings by multilingual individuals (Banda Citation2009). Further, multilingualism is typically not elective but arises out of necessity. Another difference is that in African settings, additional languages are often learned informally, and thus multilingual language users might not display ‘standard’ writing practices in these additional languages but rather forms of ‘grassroots literacy’ (Blommaert Citation2008). These differences in both the development and everyday manifestation of multilingualism across African contexts and more commonly studied Western contexts may entail differences in the relationships between individual languages and the functions that they fulfil.

Presently, our knowledge about L1 primacy is confined to how this phenomenon manifests in contexts in the Global North.Footnote1 In both linguistics and other fields, the over-reliance on Northern contexts and subjects has been criticized, and researchers have been urged to expand their participant bases and to be more careful in making claims about universality (Bylund et al. Citation2023; Castro Torres and Alburez-Gutierrez Citation2022; Kidd and Garcia Citation2022). Furthermore, non-Western, or Southern contexts are increasingly recognized as spaces that provide not only raw data but also privileged theoretical insights, especially into issues such as diversity (Comaroff and Comaroff Citation2012; Connell Citation2017). This article investigates L1 primacy in South Africa to increase the ecological validity of the research paradigm and pursue some critical questions raised by researchers located in the Global North.

Pavlenko (Citation2004, 192) notes that L1 primacy may not be ‘a phenomenon that exists across the board but rather a reflection of [a] romantic ideology … associated with European languages’ (Pavlenko Citation2004, 192). In addition to questioning the universality of L1 primacy, Pavlenko (Citation2004, 192) asks ‘whether speakers of non-Western languages, or those who grew up speaking a dialect rather than a standard variety, feel the same way’. This latter question is of particular interest in settings such as South Africa, in which pronounced inequalities in language status are present across domains (e.g. business, education) and may be reflected in speakers’ own language perceptions and use.

Whether L1 primacy holds in non-Western contexts, and whether it is dependent on the L1 in question, has not yet been empirically investigated. This article presents such an investigation, conducted among a sample of multilingual participants in the Western Cape province of South Africa. The scope of the investigation encompasses participants’ language preferences for the expression of emotions, mental calculations, and inner speech, as well as their evaluation of their languages in terms of emotional characteristics. Specifically, the research questions the article addresses are.

Which language(s), both in terms of the language itself (e.g. English, isiXhosa) and order of acquisition, are preferred for expressing emotions?

Which language(s) are preferred for mental calculations and inner speech?

How do participants evaluate their languages in terms of their emotional characteristics (i.e. ‘useful’, ‘colourful’, ‘rich’, ‘poetic’, ‘emotional’, and ‘cold’)?

We investigate these questions using an existing research instrument – the Bilingualism and Emotions Questionnaire – and an analytic approach, multiple correspondence analysis, that preserves the complexity of our data (see e.g. Ortega Citation2020).Footnote2

The following sections provide an overview of the South African linguistic context and discuss relevant literature on emotions and multilingualism. The methodology, results, and discussion follow.

Multilingualism in South Africa

South Africa is commonly regarded as one of the most multilingual countries in the world in terms of legislation, with 12 languages declared as official (in alphabetical order, Afrikaans, English, isiNdebele, isiXhosa, isiZulu, South African Sign Language, Sepedi, Setswana, Sesotho, Siswati, Tshivenda, and Xitsonga), and several other languages receiving protection under the constitution. In addition, as, migration from other parts of Africa increased after 1994, languages such as Shona (mostly spoken in Zimbabwe) and Lingala (mostly spoken in the Congo) are also increasingly used as home languages in South Africa (Mayoma and Williams Citation2021; Siziba and Hill Citation2018). As the rich multilingual situation suggests, multilingualism is a fruitful research area in South Africa (Bylund Citation2014; Coetzee-Van Rooy Citation2014; Heugh Citation2013a; Makalela Citation2015; Makukule and Brookes Citation2021).

In the Western Cape province, where the data for the current study were collected, three languages are official: Afrikaans, isiXhosa, and English. Although Afrikaans and isiXhosa have more L1 speakers, English is dominant in the public space (Posel and Zeller Citation2016; Rudwick Citation2021). Indeed, while official government communication must be conducted in all three of these official languages, a hierarchy of languages exists, with English being the most dominant, followed by Afrikaans. In education, mother-tongue schooling is available from Grades 1–3, but beyond this point only English and Afrikaans are extensively used as media of instruction. Thus, L1 isiXhosa speakers typically learn in English from Grade 4 onwards. IsiXhosa’s lower status is also reflected in its reduced use on public signage, where even when it is used, it is often riddled with mistakes and mistranslations (Dowling Citation2012).

The primacy of English in South African public life has generated some concern about a language shift to English in South Africa (e.g. Anthonissen Citation2013; Dyers Citation2008). However, several quantitative studies indicate that the mother tongue is typically maintained alongside English (Berghoff Citation2024; Coetzee-Van Rooy Citation2014; Posel, Hunter, and Rudwick Citation2022). The South African situation, then, is one in which the colonial languages exist and are widely used alongside the indigenous languages regardless of distinctions in language status. As such, it is an interesting context for investigating L1 primacy.

Emotions and multilingualism

Although emotions in linguistic expression have been investigated under various paradigms, such as language socialization (Ochs and Schieffelin Citation1989), systemic functional linguistics (Martin Citation2000), and from cross-cultural and cross-linguistic perspectives (Wierzbicka Citation1999), it has been less than 20 years since multilingualism has been put on the agenda as a serious area of investigation (see the 2004 special issue in Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development as the first demarcation of the topic). Research in this area varies both methodologically – ranging from experimental studies (Harris, Aycicegi, and Gleason Citation2003; Pavlenko Citation2008) to first-person-centred approaches (Besemeres Citation2004; Kramsch Citation2006; Prior Citation2015) – and theoretically, with some scholars opting to use not ‘emotion’ but the broader term ‘affect’, which includes emotions as well as moods, dispositions, and attitudes associated with specific people or situations (Ochs and Schieffelin Citation1989, 7).

Variation aside, this research shares a focus on speakers who use more than one language in their everyday lives and the influence of the use of multiple languages on how they express, experience, and construe emotions. Here, we focus primarily on sociolinguistic studies on multilingualism and emotions, and particularly studies that focus on L1 primacy, as this is the tradition on which this article builds.

Like the present study, most of the studies discussed here use the Bilingualism and Emotions Questionnaire (BEQ) as a data collection instrument (Dewaele Citation2004b). The original BEQ consists of 34 questions related to bilingualism and emotions, some of which are Likert-scale items and some of which are open-ended. It collects demographic information, language background information (e.g. age of acquisition, self-rated proficiency), questions regarding language choice for several emotion-related activities and mental activities, questions regarding the perceived emotional force of swearwords and taboo words in participants’ various language, and questions regarding participants’ perceptions of their languages’ characteristics (Dewaele Citation2004b). Data collected using this instrument have yielded several influential publications (e.g. Pavlenko Citation2005, with over 1,300 citations). The BEQ has been used since 2001 to investigate specific emotions or, more generally, to gather information on how linguistic trajectories and other background variables interact with how multilingual speakers express their emotions and perceive the emotionality of their languages. The original database consisted of 1,309 responses to the questionnaire. Although the sample featured 75 different L1s, African languages were absent (languages with fewer than 10 speakers were not explicitly named).

Many studies using the BEQ have found that multilingual speakers’ L1 is perceived as more emotional than their later-acquired languages and is the preferred language in which to express emotions. This L1 primacy was observed by, for example, Dewaele (Citation2004a), although he also states that rather than being universal, the extent of L1 primacy is likely to be influenced ‘by several independent variables, all related to the individual’s linguistic history’ (Dewaele Citation2004a, 94). In a subsequent study (Dewaele Citation2011), an L1 preference for swearing and communicating emotions was observed even in individuals who described themselves as ‘maximally proficient’ in the L2. Notably, however, follow-up interviews revealed that participants who had been extensively socialized in the L2 culture and had less contact with the L1 felt that their L2 had taken on the more emotional role due to the contexts in which they used it (Dewaele Citation2011, 45). This observation is particularly relevant for the current study, conducted in a setting in which people with different cultures live side by side and where socialization into an L2 culture does not necessarily entail distance from the L1 culture.

The BEQ has also been used to explore specific emotions. Dewaele (Citation2006) investigated the effects of L2 socialization on language preferences for the expression of anger and found that a language other than the L1 ‘can become the preferred language for anger expression, once emotion repertoires and scripts have been acquired in the process of language socialization’ (Dewaele Citation2006, 143). Similar findings were obtained with respect to context of acquisition and self-rated proficiency, as participants who had learned a language in an instructed environment were less likely to use that language for expressing anger (Dewaele Citation2006, 143), and those with high self-rated L2 proficiency were more likely to use the L2 for expressing anger (Dewaele Citation2006, 144). Once again, the findings from this study identify interesting aspects for consideration in the South African context. English is very often learned in instructed settings, but its pervasiveness raises the question of whether L2 speakers of the language would use it to express anger.

In more recent work with BEQ data, Dewaele focused on inner speech (i.e. the language individuals use for talking to themselves, whether out loud or silently) and found that multilinguals preferred the L1 for inner speech and for emotional inner speech, while later-learned languages were used much less frequently for these tasks. Subsequently learned languages were also used more frequently for non-emotional inner speech.

Studies using the BEQ suggest that there is a strong L1 preference for the expression of emotions. However, these studies are relatively homogenous in that they were all conducted in Northern settings. Research conducted in Africa using a different methodological approach hints that L1 primacy may not hold to the same extent in other kinds of multilingual contexts. For example, Spernes and Ruto-Korir (Citation2021) investigated language choice for emotional expression among multilingual Grade 8 pupils in rural Kenya. The pupils spoke English, Swahili, and Nandi (an indigenous Kenyan language), with Swahili and English but not Nandi being used in education. The researchers observed that learners preferred to use Swahili and English for emotional expression, with Nandi being little used. They attribute this finding to the exclusion of Nandi from educational settings.

Spernes and Ruto-Korir (Citation2021) is an important first examination of language and emotion in a multilingual African context. However, the authors themselves acknowledge some shortcomings of the study, specifically that they could not definitively determine the pupils’ L1 and that their data collection procedure may have led to the participants favouring some languages over others. The present study builds on this first African contribution while avoiding such limitations by employing the BEQ, a now-standard method for gathering data on multilingualism and emotion.

Method

Participants

170 participants (43.5% male; average age 35 years; range 15–78 years) provided complete responses to the questionnaire. 73.6% of the participants had a university degree (31.2% undergraduate only and 42.4% postgraduate). All participants reported knowing at least two languages, and 88.2% claimed to be functionally bilingual, that is, they reported using more than one language on a daily basis. Further, 52.9% of participants reported knowing three languages, 28.8% four languages, and 10.6% five languages.

Participants reported having some proficiency in 48 different languages.Footnote3 The languages most commonly spoken were English (spoken by 100% of participants), Afrikaans (74.12%), isiXhosa (21.76%), isiZulu (13.53%), French (18.24%), German (12.94%), and Shona (6.47%). Afrikaans (30%) and English (37.65%) were the languages most commonly selected as L1 (note that participants could select more than one language as their L1), followed by isiXhosa (12.94%). The order of acquisition of the most commonly used languages is presented in . Here, ‘Other African’ is an umbrella category for African languages other than isiXhosa; ‘Other European’ comprises languages spoken extensively in (Western) Europe that more than 5% of participants reported knowledge of; and ‘Other’ comprises languages not included in the previous categories.

Table 1. Order of Acquisition by Language Groups.

Age of acquisition data was collected in a broad fashion: participants indicated, for each of their additional languages, whether they had learned it between ages 0 and 6, ages 7 and 12, ages 13 and 18, or age 19 and above. Both English and Afrikaans, when acquired as additional languages, were most commonly acquired from age 0–6 (47.2% and 46.7%, respectively), with the second most common age of onset reported being age 7–12 (38.7% and 36%, respectively). For isiXhosa, 40% of additional-language speakers reported an age of acquisition of 19 years and above, with the remaining participants being equally divided (20% each) between the other age categories.

We also collected self-rated proficiency data for each of participants’ languages. Speakers of English as an additional language rated their proficiency as 13.5/15, on average (SD = 2.21). For Afrikaans, this figure was 9.79/15 (SD = 2.92); and for isiXhosa, it was 7.73/15 (SD = 3.97).

Materials

Data were collected using a slightly modified BEQ (for information on the original and the use of web questionnaires in general, see Wilson and Dewaele Citation2010). The modification entailed adding an additional response option – ‘I use more than one language in this situation’ – to some of the questions in the original BEQ version. This addition was motivated by the context of the study, in which people commonly use more than one language in their everyday lives. The survey was created and hosted on the SurveyMonkey website and was available for six months. The survey link was distributed via email and Facebook to potential participants. The first part of the survey collected demographic information, while the second part asked questions about participants’ linguistic background. The third part of the questionnaire comprised Likert-scale questions that elicited information about participants’ language use and language choices in various situations, with particular emphasis on emotional language use. The fourth and final part of the questionnaire comprised questions about emotional perceptions and language choice and asked participants to indicate, for a set of characteristics (‘useful’, ‘colourful’, ‘rich’, ‘poetic’, ‘emotional’, and ‘cold’), whether each of their languages possessed these characteristics.

Analysis

We used multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) to explore the associations between participants’ languages, their order of acquisition, and the numerous language-related variables included in the questionnaire. MCA is a statistical technique that allows for the graphical representation of the structure of multivariate categorical data (Yelland Citation2010, 1). Such data would typically be represented in a frequency table. However, when the number of variables (i.e. rows and columns) is large, the frequency table format makes it difficult to identify patterns in the relationships between and within rows and columns. In such cases, the plots created via MCA facilitate the representation and interpretation of the data (Durbach Citation2014, 14).

MCA represents variables or categories of variables as coordinate points on a correspondence plot. The maximum number of dimensions of such a correspondence plot is calculated by subtracting 1 from the number of rows or columns (whichever is highest) in the frequency table of the data. Visualizing this maximum number of dimensions is, however, impractical and does not facilitate the interpretation of the data. As such, a process of dimensionality reduction is undertaken so that the data can be represented in fewer dimensions, typically two.

We analysed only the data relevant to our research questions, namely that on language use (which included scores for feelings, anger, mental calculations, inner speech, and memory recall) and language perception (which included rating scores of languages as useful, colourful, rich, poetic, emotional, and cold). These data were simultaneously cross-tabulated against language group and order of acquisition, with language group and order of acquisition (e.g. L1 English, L2 isiXhosa) represented as rows and the various language features or characteristics represented as columns.

We then generated several MCA plots to represent the associations in these high-dimensional tables between language group and order of acquisition on the one hand and the different measures of language use and language perception on the other. A dimensionality reduction process was employed to allow for the illustration of these many associations in two dimensions.

In the resulting two-dimensional plots, weighted row and column averages (termed ‘profiles’) are represented as points, with the distance between row points indicating the extent of their similarity. Here, rows with similar profiles are positioned in greater relative proximity than rows with dissimilar profiles, with the same being true for columns. Further, the distance between a point and the origin of the plot (i.e. the 0,0 point) is referred to as the point’s ‘inertia’, where a higher inertia value reflects a greater difference of the point’s profile from the average distribution of the data (Greenacre Citation2017, 38). Thus, a particular category is more distinct from the average when it lies further from the plot’s origin.

The two axes (horizontal and vertical) of these plots each explain some proportion of the variance in the data. The sum of these two values indicates the total amount of variance that is captured in the plot and reflects the extent to which the plot is able to reflect the data structure.

While the aim of the study was not to conduct statistical testing of particular hypotheses, we also report on the results of chi-square tests run to follow up on patterns related to L1 primacy that were identified in the MCA plots. In interpreting the chi-square results, categories with residuals (i.e. discrepancies between the actual values and the expected values) over 2 are understood to be strong contributors to the significant chi-square value (Sharpe Citation2015). Where chi-square results are not significant but there are clear trends in the plots, we report response percentages.

R (version 4.2; R Core Team Citation2022) was used to analyse the data and produce the plots. We used the ca (version 0.71.1; Nenadic and Greenacre Citation2007) and ggplot2 (version 3.3.6; Wickham Citation2016) packages. The tables containing the raw data and the accompanying R scripts are available at https://osf.io/g392j/?view_only = feedec9a096f4af49360ba0bd7efb95f.

Results

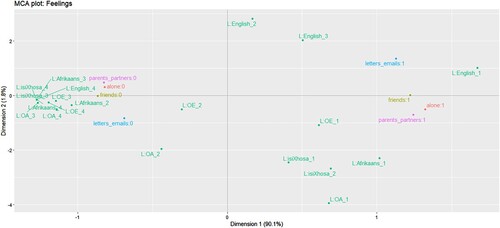

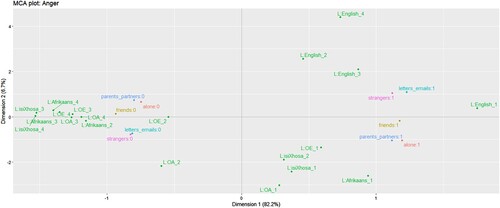

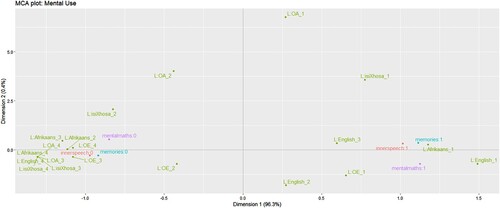

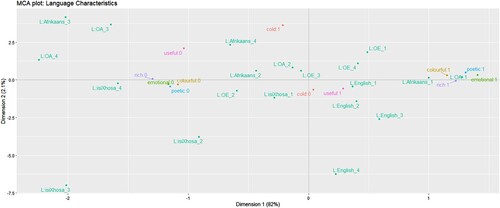

Language use and perception patterns are illustrated in four MCA plots: one for the expression of feelings, one for the expression of anger, one that reflects mental activities (mental calculations, inner speech, and memory recall), and one that reflects participants’ perceptions of their languages’ characteristics.

illustrates the associations between each language group and language use patterns when communicating feelings in a variety of situations (when alone, with friends, with family, and in written correspondence), where participants indicated whether they did or did not use each of their languages in each situation. Cumulatively, the plot captures 92% of the variance in the data; indicating that the plot accurately illustrates the data’s structure. The horizontal dimension shows the contrast between use and non-use of languages for the given situations, with non-use on the left side and use on the right side. As shown by the greater spread of the points along this axis, it is the contrast between use and non-use that explains most of the variance in the data. In the vertical dimension, there is a contrast between English, which appears in the upper half of the dimension, and all other languages, which appear in the lower half. In addition, written correspondence (letters) contrasts with other situations.

Figure 1. Language Use Patterns for Feelings. Language point labels are in green and follow the format of L:LanguageName_OrderofAcquistion, such that ‘L:isiXhosa_1’ is the point for L1 isiXhosa. In the language point labels, ‘OE’ and ‘OA’ denote ‘Other European’ and ‘Other African’, respectively. Each language use situation appears on the plot as two points: one reflecting use (e.g. ‘letters_emails:1’) and one reflecting non-use (e.g. ‘letters_emails_0’).

Overall, there seems to be a clear preference for using the L1 to communicate feelings in any situation, as can be seen by the appearance of the L1 points on the right of the plot. This general preference for the L1 is reflected in the fact that a chi-square test conducted on the L1 data is not statistically significant (X2 (12, N = 170) = 18.85, p = .09). It is only L2 and L3 English, as well as L2 isiXhosa, that are also associated with use for communicating feelings. Indeed, a chi-square test conducted on the L2 data is statistically significant (X2 (12, N = 170) = 21.25, p = .04), suggesting differences in the use patterns of the different L2s. An examination of the residuals indicates that this difference is driven by preferences for the expression of feelings in writing, where English is strongly preferred (residual = 3.77). The residuals for L2 isiXhosa are not large, likely because only four respondents had isiXhosa as an L2, and only three of these individuals responded to the relevant question. However, 2–3 of these respondents indicated that they used isiXhosa to communicate feelings in all situations except written correspondence.

All other languages appear on the left of the plot and are associated with non-use. The clustering of language points here indicates similar profiles for all participants’ additional languages, suggesting that for languages other than English, it is primarily language status (L1 vs. non-L1) that matters here rather than the particular language in question.

In terms of the column profiles, language use with family and when alone follow similar patterns, as can be seen by their proximity on the plot, while language use for written correspondence follows a different pattern: as discussed above, English is generally preferred here, regardless of its order of acquisition.

illustrates the associations between the language groups and their use for expressing anger in various situations, with the added situation of communicating with strangers. Cumulatively, the horizontal and vertical dimensions of the plot explain 89% of the variance in the data, with the horizontal dimension again contributing most in this regard.

Figure 2. Language Use Patterns for Anger.

As in , the horizontal dimension shows the contrast between the use versus non-use of specific languages for expressing anger, with non-use on the left and use on the right. The arrangement of language groups in is largely identical to that in , where it is generally the L1 that is used to communicate anger, with English also being used regardless of its order of acquisition (i.e. L1, L2, L3, L4). L2 isiXhosa is again the only non-L1 that is associated with use versus non-use to communicate anger.

In the vertical dimension, we see differentiation between language use with family and when alone, on the one hand, and language use in written communication and with strangers. In the latter situations, which are more public in nature, English is primarily used, whereas the other L1s are used in the intimate domains. The significant result of a chi-square test conducted on the L1 data (X2 (16, N = 170) = 37.37, p = .002) supports the interpretation that the L1s differ with respect to their use for the expression of anger. Specifically, of all the L1s, the preference for English when expressing anger in writing is especially strong (residual = 3.84), and isiXhosa and other African languages are dispreferred for this use (residuals = −2.33, and – 2.37, respectively).

illustrates the associations between the language groups and their patterns of use for mental operations: mental calculations, inner speech, and memory recall. Cumulatively, the two dimensions explain 96.7% of the variance in the data. The horizontal dimension, which accounts for most of the variance, again shows the contrast between language non-use (left) versus use (right) for the various activities.

Figure 3. Language Use Patterns for Mental Use.

This distribution of points along this dimension shows that the L1 is generally associated with use for these activities, while the L2, L3, and L4 are not strongly associated with use in these cases. Exceptions arise in the cases of L1 isiXhosa and other African-language L1s, which are positioned far away from the mental mathematics point in the vertical dimension, reflecting that although these L1s are used for inner speech and memory recall, they are less used for mental calculation. While a chi-square test on the entirety of the L1 data is not statistically significant (X2 (8, N = 170) = 13.68, p = .09), this difference in L1 use for mental mathematics is reflected in the percentages: 45% and 6% of L1 isiXhosa and other L1 African-language speakers, respectively, reported using their L1 for this task. These percentages are markedly lower than those for the other L1s (Afrikaans 82%, English 100%, and Other European 75%).

Lastly, once again, English seems to be used for these activities even when it is an L2 or L3, with L2 English especially being associated with use for mental mathematics: 65% of L2 English speakers use English in this domain, but other L2s are hardly used (Afrikaans 4%, isiXhosa 0%, Other African 0%, and Other European 33%).

illustrates the characteristics attributed to each of the language groups. Cumulatively, the plot captures 84.1% of the variance in the data. The horizontal dimension contrasts the absence versus presence of language characteristics, with the exception of ‘cold’, which is the only negative characteristic. All the L1s except isiXhosa were associated with the more positive language characteristics (rich, emotional, colourful, etc.). A chi-square test conducted on the L1 data was not statistically significant (X2 (20, N = 170) = 10.7, p = .9), but in terms of percentages, isiXhosa scored lowest on all positive characteristics, with particularly few respondents reporting that this language was ‘colourful’ (27%) and ‘poetic’ (36%). English, in contrast, was always associated strongly with positive characteristics, regardless of whether it was the L1 or a later acquired language (note the positions of L:English_1, L:English_2, and L:English_3). Indeed, in terms of percentages, English scored highest of all L2s and L3s on all the positive characteristics. Other European L4s were also positively perceived.

Figure 4. Perceptions of Language Characteristics.

The second dimension, although it captures only a small amount of variation in the data, contrasts usefulness (in the upper dimension) with non-usefulness (in the lower dimension). English is concentrated around the ‘useful’ point.

Discussion and conclusion

The impetus for this paper was to investigate Pavlenko’s (Citation2004) question about whether the idea of L1 primacy (i.e. that the L1 is always the preferred language and carries the strongest emotional weight) holds outside of Northern settings. In doing so, the paper went beyond previous research, which has focused on order of acquisition without considering specific L1s, L2s, and so forth. Tailoring our approach to suit our multilingual setting, in which indigenous languages exist alongside societally dominant English, we employed a data analysis method that allowed for the investigation of order of acquisition in combination with specific languages. Also relevant here is the fact that our questionnaire allowed participants to report use of more than one language in a specific situation, in keeping with the fluid multilingual contexts found in South Africa.

The results reveal some patterns that warrant further discussion. These patterns speak to the debate regarding the universality of L1 primacy while also shedding new light on the emotional aspects of South African multilinguals’ linguistic repertoires.

Beginning with the communication of feelings and anger: here, we observed a preference for use of the L1, regardless of what language it was. The exceptional situation was the communication of feelings and anger in written correspondence (letters, emails) and the expression of anger towards strangers. For these uses, English was the preferred language, regardless of order of acquisition. This finding makes sense in light of the more public-facing nature of these activities, where it perhaps cannot be assumed that the recipient of communication shares the same L1 as the speaker. In such situations, English may serve as a lingua franca.

We again observe a general L1 preference for the mental activities of inner speech and memory recall, with all L1s being associated with use for these activities. Mental mathematics, a less personal mental activity than inner speech and memory recall, patterned distinctly, where L1 isiXhosa and other African-language L1s tended not to be used for mental calculations, and L2 and L3 English were associated with use for this purpose. This pattern may relate to the preference for English in the teaching of mathematics even to learners with another mother tongue (e.g. Cekiso, Meyiwa, and Mashige Citation2019). More generally, English terms for numbers and numerical concepts have been widely integrated into the isiXhosa lexicon, such that many speakers use these terms rather than the ‘pure’ isiXhosa equivalents, which tend to be much more complex (e.g. the isiXhosa equivalent of ‘seventeen’ is ishumi elinesixhenxe, literally ‘ten that has seven’). Some language and education researchers have also claimed that mathematical curricula are currently not ‘responsive to the character of African languages’ (Lepota Citation2023, 26). As such, L1 African language speakers’ use of L2 and L3 English to perform mental calculations makes sense.

Lastly, we examined respondents’ emotional evaluations of their various languages in terms of the characteristics of ‘useful’, ‘rich’, ‘emotional’, ‘poetic’, ‘colourful’, and ‘cold’. Here, all L1s except isiXhosa were associated with the positive characteristics. Languages that were also positively perceived even when they were additional languages were English and other European languages. English in particular was more strongly associated with the characteristic of ‘usefulness’ than the other languages.

L1 isiXhosa speakers’ non-positive evaluation of their mother tongue stands out in the data and may be attributable to the language’s position on the hierarchies of language status and power in South Africa. Notably, Afrikaans, the other well represented language in the Western Cape, was associated with all the positive characteristics. Afrikaans, like isiXhosa, is less societally prominent than English; however, it is more powerful than isiXhosa, in that Afrikaans remains a medium of instruction throughout secondary schooling and even to some extent in tertiary education, and Afrikaans media is strong and well-funded (Steyn Citation2016). The relative accessibility and prominence of Afrikaans in education, literature, and entertainment may contribute to its perception as ‘rich’, ‘poetic’, and ‘colourful’ despite the even greater prominence of English.

We note further that although L1 isiXhosa was not associated with the positive characteristics, other African-language L1s were. This finding is somewhat difficult to interpret because the ‘Other African Language’ category encompasses several languages – some indigenous to South Africa, some not – all of which may be differently perceived. One possible explanation for this finding may be that non-indigenous languages, and L1 speakers’ perceptions of them, are to some extent unaffected by the language hierarchies in South Africa.

While our results partly support previous findings in multilingualism and emotions research, they also contribute a new perspective on the topic. Like the findings of Spernes and Ruto-Korir (Citation2021) and other studies using qualitative autobiographical data (Bristowe et al. Citation2014; Mashazi and Oostendorp Citation2022), our results suggest that the relationship between language and emotion might differ across Global North and African multilingual contexts. Specifically, our findings prompt a rethinking of the widely accepted ideology of L1 primacy and suggest that more can be discovered when examining the characteristics of particular languages rather than focusing solely on order of acquisition, which has previously been the trend in this area of study.

The findings also suggest that more research is needed on the effect of language of education, and specifically literacy in the L1, on perceptions of language use for and in emotional contexts. Spernes and Ruto-Korir (Citation2021) attribute their participants’ non-use of Nandi for the expression of emotions to this language’s exclusion from the school system. In other words, they propose that learners do not use their indigenous language to tell emotion-related stories because their expressive abilities in this language are comparatively underdeveloped. Indeed, many African language speakers have only limited literacy in their L1 (see for example Williams and Cooke Citation2002); regarding the South African context specifically, Heugh (Citation2013b) reports a decline in the number of students who study African languages at university and a neglect of teacher training in reading and writing in the home language. Thus, in our data, language preferences for written correspondence and mental calculations – activities for which L2 English was favoured over L1 isiXhosa and other African-language L1s – may have less to do with emotionality and choice and more to do with the individual’s schooling experience and/or their ability to express themselves in their L1 in writing. In fact, our background data suggests that very few of the L1 isiXhosa speakers had any exposure to isiXhosa in educational settings (either as medium of instruction or language subject).

Finally, our findings also speak to the ongoing debate regarding language shift to English in South Africa. Like other studies examining South African multilinguals’ language use and preferences (Berghoff Citation2024; Coetzee-Van Rooy Citation2014; Posel, Hunter, and Rudwick Citation2022), our results do not support the idea that English is displacing the indigenous South African languages. Rather, despite preferences for English in certain situations, we observe a prioritization of the L1 for more personal uses, such as inner speech and the communication of emotions and anger to loved ones. Notably, this preference for the L1 persists even though our participants report high proficiency in English as a second language, which aligns with Dewaele’s (Citation2011) finding of an L1 preference for emotional expression even among participants who reported maximal proficiency in the L2.

The study is subject to a few limitations. Firstly, our participants were drawn from one province in South Africa – the Western Cape – and were, on average, highly educated. Multilingual individuals from different regions and of different socio-economic backgrounds may have different language use preferences and different perceptions of the emotionality of their various languages. In addition, our sample of L1 isiXhosa speakers is relatively small. Further research might seek to replicate our findings with a larger sample of native speakers of this language.

Overall, the present study hints that the language(s) of the heart may be considerably more complex than what current literature suggests and raises the possibility that the type of multilingual context in which languages are acquired may be as important as multilingualism per se in the construal and expression of emotions. The patterns we have identified will hopefully invite more research on language and emotion in Southern contexts. Future research might, like the present study, pursue approaches to the analysis of large-scale data that aim to preserve its complexity. Another avenue for exploration would be to develop new tools for collecting data on multilingualism and emotions that are grounded in the realities of language learning and use in non-Western settings. Here, it may be particularly useful to think in terms of repertoires rather than named languages (e.g. Wei and García Citation2022). Such endeavours can contribute to building ‘a richer and more complete understanding’ of our species (Apicella, Norenzayan, and Henrich Citation2020, 326) and the languages we use to make sense of our worlds.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marcelyn Oostendorp

Marcelyn Oostendorp is an Associate Professor in the Department of General Linguistics at Stellenbosch University, South Africa. Her research is primarily concerned with multilingual and multimodal forms of meaning-making in contexts such as education, the media, and the workplace. Her research has appeared in outlets such as Applied Linguistics, Text and Talk, Critical Discourse Studies, and Social Semiotics.

Tanya Little

Tanya Little completed her MA in General linguistics at the Department of General Linguistics at Stellenbosch University.

Robyn Berghoff

Robyn Berghoff (Stellenbosch University) is a psycholinguist interested in language acquisition as well as bilingual language representation and processing. She is currently leading a project investigating morphosyntactic representation and processing in second language learners of isiXhosa. Her work has appeared in outlets such as Applied Linguistics, Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, Second Language Research and Studies in Second Language Acquisition.

Notes

1 In much of the social sciences and humanities, the distinction between Western and non-Western contexts is not used, and reference is instead made to the ‘Global North’ and ‘Global South’. According to Dados and Connell (Citation2012, 13), ‘Global South functions as more than a metaphor for underdevelopment. It references an entire history of colonialism, neo-imperialism, and differential economic and social change through which large inequalities in living standards, life expectancy, and access to resources are maintained’. These authors also acknowledge that the Global South is entangled with the Global North, in that pockets of the North can be found in the South and vice versa.

2 Correspondence analysis, while not widely used in multilingualism research, is frequently employed in other subdomains of linguistics, such as corpus linguistics (e.g., Deshors Citation2017) and cognitive linguistics (e.g., Janda Citation2019).

3 The 48 languages listed by participants were, in alphabetical order: Afrikaans, Arabic, Catalan, Chichewa, Croatian, Dutch, English, Fang, French, German, Greek, Gujarati, Hebrew, Hindi, Italian, Japanese, Kikongo, Kimbala, Kurdish, Latin, Lingala, Malay, Mandarin Chinese, isiNdebele, isiXhosa, isiZulu, Ngemba, Norwegian, Norwegian Sign Language, Sepedi, Persian, Polish, Portuguese, Russian, Sesotho, Setswana, Shanghainese, Shona, Siswati, Spanish, Swahili, Swedish, Tamil, Tshangana, Tshivenda, Upper Ngemba, Yoruba, and Xitsonga. Note that here we list languages as they were listed by participants without attempting to distinguish between languages, dialects, and varieties.

References

- Anthonissen, C. 2013. “‘With English the World is More Open to You’–Language Shift as Marker of Social Transformation: An Account of Ongoing Language Shift from Afrikaans to English in the Western Cape.” English Today 29 (1): 28–35. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266078412000545

- Apicella, C., A. Norenzayan, and J. Henrich. 2020. “Beyond WEIRD: A Review of the Last Decade and a Look Ahead to the Global Laboratory of the Future.” Evolution and Human Behavior 41 (5): 319–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2020.07.015

- Banda, F. 2009. “Critical Perspectives on Language Planning and Policy in Africa: Accounting for the Notion of Multilingualism.” Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics PLUS 38: 1–11.

- Berghoff, R. 2024. “The role of English in South African multilinguals’ linguistic repertoires: A cluster-analytic study.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 45 (4): 1082–1096.

- Besemeres, M. 2004. “Different Languages, Different Emotions? Perspectives from Autobiographical Literature.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 25 (2-3): 140–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434630408666526

- Besnier, N. 1990. “Language and Affect.” Annual Review of Anthropology 19 (1): 419–451. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.an.19.100190.002223

- Blommaert, J. 2008. Grassroots Literacy: Writing, Identity and Voice in Central Africa. London: Routledge.

- Bristowe, A, M Oostendorp, and C Anthonissen. 2014. “Language and youth identity in a multilingual setting: A multimodal repertoire approach..” Southern African linguistics and applied language studies 32: 229–245.

- Bylund, E. 2014. “Unomathotholo or i-radio? Factors Predicting the use of English Loanwords among L1 isiXhosa-L2 English Bilinguals.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 35 (2): 105–120.

- Bylund, E, Z Khafif, and R Berghoff. 2023. “Linguistic and geographic diversity in research on second language acquisition and multilingualism: An analysis of selected journals.” Applied Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amad022.

- Castro Torres, A. F., and D. Alburez-Gutierrez. 2022. “North and South: Naming Practices and the Hidden Dimension of Global Disparities in Knowledge Production.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 119 (10): e2119373119. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2119373119

- Cekiso, M., T. Meyiwa, and M. Mashige. 2019. “Foundation Phase Teachers’ Experiences with Instruction in the Mother Tongue in the Eastern Cape.” South African Journal of Childhood Education 9 (1): 67. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajce.v9i1.658.

- Coetzee-Van Rooy, S. 2014. “Explaining the Ordinary Magic of Stable African Multilingualism in the Vaal Triangle Region in South Africa.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 35 (2): 121–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2013.818678

- Comaroff, J., and J. L. Comaroff. 2012. “Theory from the South: Or, how Euro-America is Evolving Toward Africa.” Anthropological Forum 22 (2): 113–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.2012.694169

- Connell, R. 2017. “Southern Theory and World Universities.” Higher Education Research & Development 36 (1): 4–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1252311

- Dados, N., and R. Connell. 2012. “The Global South.” Contexts 11 (1): 12–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536504212436479

- Deshors, S. C. 2017. “Zooming in on Verbs in the Progressive: A Collostructional and Correspondence Analysis Approach.” Journal of English Linguistics 45 (3): 260–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/0075424217717589.

- Dewaele, J.-M. 2004a. “Blistering Barnacles! What Language do Multilinguals Swear in?!.” Estudios de Sociolingüística 5 (1): 83–105.

- Dewaele, J.-M. 2004b. “The Emotional Force of Swearwords and Taboo Words in the Speech of Multilinguals.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 25 (2-3): 204–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434630408666529

- Dewaele, J.-M. 2006. Expressing Anger in Multiple Languages. In Bilingual Minds: Emotional Experience, Expression and Representation, edited by A. Pavlenko, 118–149. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Dewaele, J.-M. 2011. “Self-reported use and Perception of the L1 and L2 among Maximally Proficient bi- and Multilinguals: A Quantitative and Qualitative Investigation.” International Journal of the Sociology of Language 208: 25–51.

- Dowling, T. 2012. “Translated for the Dogs: Language use in Cape Town Signage.” Language Matters 43 (2): 240–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/10228195.2012.688763

- Durbach, I. 2014. “Chapter 2: Correspondence Analysis.” In Applied Multivariate Data Analysis Course Notes for STA3022F: Research and Survey Statistics. Cape Town: Department of Statistical Sciences University of Cape Town.

- Dyers, C. 2008. “Truncated Multilingualism or Language Shift? An Examination of Language use in Intimate Domains in a new non-Racial Working Class Township in South Africa.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 29 (2): 110–126. https://doi.org/10.2167/jmmd533.0

- Greenacre, M. 2017. Correspondence analysis in practice. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC.

- Harris, C. L., A. Aycicegi, and J. B. Gleason. 2003. “Taboo Words and Reprimands Elicit Greater Autonomic Reactivity in a First Language Than in a Second Language.” Applied Psycholinguistics 24 (4): 561–579. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716403000286

- Heugh, K. 2013a. “Multilingual Education Policy in South Africa Constrained by Theoretical and Historical Disconnections.” Annual Review of Applied Linguistics 33: 215–237. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190513000135

- Heugh, K. 2013b. “Literacy and Language/s in School Education in South Africa.” In Towards a 20 Year Review: Basic and Post School Education, edited by V. Reddy, A. Juan, and T. Meyiwa, 18–33. Pretoria: Human Sciences Research Council.

- Janda, L. A. 2019. “Corpus Approaches to Language, Thought and Communication.” Review of Cognitive Linguistics 17 (1): 7–28. https://doi.org/10.1075/rcl.00024.jan.

- Kidd, E., and R. Garcia. 2022. “How Diverse is Child Language Acquisition Research?” First Language 42 (6): 703–735. https://doi.org/10.1177/01427237211066405

- Kramsch, C. 2006. “The Multilingual Subject.” International Journal of Applied Linguistics 16 (1): 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-4192.2006.00109.x

- Lepota, B. 2023. “(Mis) Versioning as a Quality Assurance Compromise in the Development of Numeracy Curriculum in African Languages.” Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 41 (1): 16–28. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073614.2023.2185978

- Makalela, L. 2015. “Moving out of Linguistic Boxes: The Effects of Translanguaging Strategies for Multilingual Classrooms.” Language and Education 29 (3): 200–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500782.2014.994524

- Makukule, I., and H. Brookes. 2021. “English in the Identity Practices of Black Male Township Youth in South Africa.” World Englishes 40 (1): 52–62. https://doi.org/10.1111/weng.12472

- Martin, J. R. 2000. Beyond Exchange: Appraisal Systems in English. In Evaluation in Text: Authorial Stance and the Construction of Discourse, edited by S. Hunston, and G. Thompson. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mashazi, S, and M Oostendorp. 2022. “Belonging: The interplay of linguistic repertoires, bodies, and space in an educational context..” In Speaking Subjects in Multilingualism Research: Biographical and Speaker-centred Approach , edited by Judith Purkarthofer and Mi-Cha Flubacher, 139–162. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Mayoma, J., and Q. Williams. 2021. “Fitting in: Stylizing and (re) Negotiating Congolese Youth Identity and Multilingualism in Cape Town.” Lingua. International Review of General Linguistics. Revue Internationale De Linguistique Generale 263: 102854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2020.102854

- Myers-Scotton, C. 1993. Social Motivations for Codeswitching: Evidence from Africa. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Nenadic, O., and M. Greenacre. 2007. “Correspondence Analysis in R with Two- and Three-Dimensional Graphics: The ca Package.” Journal of Statistical Software 20 (3), https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v020.i03.

- Ochs, E., and B. Schieffelin. 1989. “Language has a Heart.” Text 9 (1): 7–25.

- Oostendorp, Marcelyn. 2012. “New perspectives on cross-linguistic influence: Language and cognition.” Language Teaching 45 (3): 389–398. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0261444812000080.

- Ortega, L. 2020. “The Study of Heritage Language Development from a Bilingualism and Social Justice Perspective.” Language Learning 70 (S1): 15–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12347

- Pavlenko, A. 2004. “‘Stop Doing That, Ia Komu Skazala!’: Language Choice and Emotions in Parent-Child Communication.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 25 (2-3): 179–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434630408666528

- Pavlenko, A. 2005. Emotions and Multilingualism. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Pavlenko, A. 2006a. Bilingual Selves. In Bilingual Minds: Emotional Experience, Expression and Representation. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Pavlenko, A. 2006b. “Emotion and Emotion-Laden Words in the Bilingual Lexicon.” Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 11 (2): 147–164. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728908003283

- Pavlenko, A. 2008. “Emotion and Emotion-Laden Words in the Bilingual Lexicon.” Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 11 (2): 147–164. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728908003283

- Posel, D., M. Hunter, and S. Rudwick. 2022. “Revisiting the Prevalence of English: Language use Outside the Home in South Africa.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 43 (8): 774–786. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2020.1778707.

- Posel, D., and J. Zeller. 2016. “Language Shift or Increased Bilingualism in South Africa: Evidence from Census Data.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 37 (4): 357–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2015.1072206

- Prior, M. T., 2015. Emotion and Discourse in L2 Narrative Research. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- R Core Team. 2022. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Retrieved from https://www.R-project.org/.

- Richards, J. C. 2022. “Exploring Emotions in Language Teaching.” RELC Journal 53 (1): 225–239. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688220927531

- Rudwick, S. 2021. The Ambiguity of English as a Lingua Franca: Politics of Language and Race in South Africa. London: Routledge.

- Sharpe, D. 2015. “Chi-square Test is Statistically Significant: Now What?” Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation 20 (1): 8.

- Siziba, G., and L. Hill. 2018. “Language and the Geopolitics of (dis) Location: A Study of Zimbabwean Shona and Ndebele Speakers in Johannesburg.” Language in Society 47 (1): 115–139. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047404517000793

- Spernes, K. I., and R. Ruto-Korir. 2021. “Multilingualism and Curriculum: A Study of how Multilingual Learners in Rural Kenya use Their Languages to Express Emotions.” International Journal of Educational Development 81: 102328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2020.102328

- Steyn, A. S. 2016. “Afrikaans, Inc.: The Afrikaans Culture Industry After Apartheid.” Social Dynamics 42 (3): 481–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/02533952.2016.1259792.

- Swain, M. 2013. “The Inseparability of Cognition and Emotion in Second Language Learning.” Language Teaching 46 (2): 195–207. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444811000486

- Wei, L., and O. García. 2022. “Not a First Language but one Repertoire: Translanguaging as a Decolonizing Project.” RELC Journal 53 (2): 313–324. https://doi.org/10.1177/00336882221092841.

- Wickham, H. 2016. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. 2nd ed. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Wierzbicka, A. 1999. Emotions Across Languages and Cultures: Diversity and Universals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Williams, E., and J. Cooke. 2002. “Pathways and Labyrinths: Language and Education in Development.” TESOL Quarterly 36 (3): 297–322. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588415

- Wilson, R., and J. M. Dewaele. 2010. “The use of web Questionnaires in Second Language Acquisition and Bilingualism Research.” Second Language Research 26 (1): 103–123. https://doi.org/10.1177/0267658309337640

- Yelland, P. M. 2010. “An Introduction to Correspondence Analysis.” The Mathematica Journal 12 (1): 86–109.