ABSTRACT

In the present study, we combined the Focus on Multilingualism approach with the human capital theory to investigate multilingual profiles among first-generation adult immigrants in Germany and the relationship between immigrants’ multiliteracy and their employment status. We used data representative for Germany on the self-reported literacy skills in the majority, heritage, and foreign languages of first-generation immigrants (n = 451, age 18–64) gathered in the LEO 2018 study. To analyze multilingual literacy skills, we estimated adults’ multilingual profiles using LCA. In a second step, we conducted logistic regression models with multiliteracy and employment status. We found two multilingual profiles of first-generation immigrants: a profile with higher and a profile with lower literacy skills in all investigated languages. The profiles differed by the level of adults’ literacy skills in all investigated languages and showed a unique non-overlapping language ordering pattern. The results gained from the logistic regressions revealed that multiliteracy in first-generation immigrants may represent human capital in Germany. After controlling for additional variables (age, gender, education), the analysis showed that higher multiliteracy increases the probability of adult immigrants’ employment. Furthermore, our findings indicated independent positive effects of literacy in each language in multilingual repertoires on employment probability.

Introduction

In light of globalization, societal linguistic diversity increases, especially in urban areas. This process is accompanied by the emergence of the ‘new information economy’ (Grin, Sfreddo, and Vaillancourt Citation2010; Heller Citation2003; Citation2010), characterized by a shift from manual to language-intense work, with linguistically coded information and knowledge becoming crucial for productivity (Alarcón et al. Citation2014; Breton Citation1978). Alongside with oral communicative language skills, the ability to deal with written content in multiple languages and different modes, referred to as multiliteracies (New London Group Citation1996), contributes to the employees’ ‘multiskilling’ in the new economy workplace (Cope and Kalantzis Citation2009). In this context, the economic value of multilingual literacy skills becomes prominent (Gándara Citation2018).

In recent decades, diversity has constantly been increasing in Germany, with immigrants from about 190 countries contributing to the country's economic, social, linguistic, and cultural diversification (see Gogolin Citation2018; Gogolin, McMonagle, and Salem Citation2019). Based on a representative sample, the German large-scale ‘LEO Survey 2018 – Living with Low Literacy (LEO 2018)’ investigated the German-speaking adult population aged between 18 and 64 years. The results of the LEO 2018 study confirm the linguistic diversity in Germany and show that out of 55.5 million citizens, 13.4% are first-generation immigrants who grew up in a language other than German and learned German later in life as a foreign language (Heilmann and Grotlüschen Citation2020, 119). Remarkably, this group was overrepresented among adults with low literacy skills in German (47.4%) relative to their share in the general population (Heilmann and Grotlüschen Citation2020, 120). At the same time, 57.4% of first-generation immigrants show German test scores at higher literacy levels (Heilmann and Grotlüschen Citation2020, 121). Furthermore, 30.8% of first-generation immigrants report being highly literate in languages(s) other than German (Heilmann and Grotlüschen Citation2020, 128).

Overall, based on LEO 2018 data, higher literacy skills in German were reported to be associated with a higher employment rate (63.7% of adults with low literacy skills were employed vs. 79.7% of adults at higher literacy levels, see Stammer Citation2020, 170). Within the group of adults with low literacy skills, the absolute rates of employment (including full-time or part-time employment, or parental leave) were similar across the groups differing by language(es) of origin (61.5% employed among monolingual speakers of German, 66.5% among multilinguals who grew up with German and 64.9% among multilinguals who grew up without German, see Heilmann and Grotlüschen Citation2020, 123 f.). Whether and how the literacy skills in languages other than German relate to the adults’ literacy skills in German and whether multilingual literacy skills may contribute to the adults’ employment status was not further considered. Especially in those immigrants who learn German as a foreign language, literacy skills in the heritage language may provide a basis for acquiring German literacy skills (Schnoor and Usanova Citation2022) but also serve as a tool for accessing labor market opportunities available in specific languages within larger immigrant communities (Blake and Walter Citation2021).

The current study aims to explore the role of immigrant adults’ multiliteracy as human capital in the German labor market by conducting secondary analyses of the LEO 2018 data. Adopting a resource-oriented interdisciplinary approach, we bridge Focus on Multilingualism (FoM; Cenoz and Gorter Citation2011) with the human capital theory (Becker Citation1964) and integrate all languages from immigrant adults’ repertoire into the data analyses. The main contribution of this study is twofold. First, our study provides valuable information on immigrant adults’ multilingual profiles in Germany based on a representative sample. Second, our study clarifies the role of multiliteracy on employment in the German labor market. Specifically, we focus on both the effects of multiliteracy as a set of interrelated skills and the effects of each particular language in a person’s repertoire.

Approaching multilingual literacy skills as human capital

The Human Capital Theory (Becker Citation1964) assumes that investments in a person’s education and training increase productivity, which, in turn, generates economic benefits for this person in the labor market. Language skills meet the requirements for human capital: they are productive, costly to produce, and embodied in person (Chiswick and Miller Citation2014, 5). In linguistically diverse contexts, employees’ language repertoires may involve multiple languages: the majority, foreign, and heritage languages. Literacy skills in a person’s multilingual repertoire represent available cultural capital that may be drawn on depending on the demands of linguistic markets (Bourdieu Citation1977).

The FoM (Cenoz and Gorter Citation2011) provides a theoretical framework for investigating multilingual skills within linguistically diverse contexts. The FoM suggests that languages in multilingual repertoires should be investigated in their whole complexity rather than in isolation. Thus, the research on multilinguals needs to account for (1) whole multilingual repertoires with languages acquired in the family and learned at school, (2) the interrelations between the languages in the repertoires, and (3) the social contexts where multilingual development takes place (Cenoz and Gorter Citation2011). The empirical research that followed the FoM provided evidence for the interrelation of literacy skills in multilingual repertoires (e.g. Arias-Hermoso and Imaz Agirre Citation2023; Orcasitas-Vicandi Citation2022; Riehl Citation2021; Soltero-González, Escamilla, and Hopewell Citation2012). While simultaneously analyzing students writing skills in the majority language (German), heritage languages (Russian or Turkish) and the foreign language (English), Usanova and Schnoor (Citation2021) found different profiles of multilingual writing skills in second-generation immigrant adolescents in Germany and revealed that writing skills within the profiles are positively interrelated between the languages. In a further study, Usanova and Schnoor (Citation2022) proposed that multiliterate skills may be considered within an integrated model of multiliteracy at two levels: (1) the language-specific proficiencies and (2) the unified competence built by interrelations between language-specific proficiencies.

The relationship between language skills and labor-market outcomes has been addressed concerning different languages and from the two contrasting theoretical perspectives (for an overview, see Agirdag Citation2014a; Citation2014b; Aldashev, Gernandt, and Thomsen Citation2009).

The deficit perspective presumes that the majority language has the major economic value and that migration-related deficits in this language hamper productivity (e.g. Chiswick and Miller Citation2014; Shin and Alba Citation2009). Furthermore, the level of literacy skills in the majority language is crucial for successful placement in the labor market. Studies conducted for different national contexts have shown that elaborated writing skills in the majority language are associated with significant income effects (Chiswick and Repetto Citation2001; Dustmann Citation1994). However, according to Agirdag (Citation2014a; Citation2014b), the deficit perspective neglects the economic value of the other languages in immigrants’ language repertoires.

The strength perspective considers that heritage or foreign language literacy skills may also have a significant economic value in the migration context. Concerning heritage language skills, the research on employment and earnings showed that well-developed literacy skills are associated with higher earnings in biliterate bilinguals compared to linguistically assimilated bilinguals (Agirdag Citation2014a; Citation2014b), as well as higher occupational status and long-term earnings compared to monolinguals (Rumbaut Citation2014). However, the mentioned studies investigated only the regional bilingual population in specific US regions, i.e. the bilingual advantage in Hispanic residents in southern California and South Florida. Thus, further research is needed to clarify whether these results can be extended to other contexts. In terms of foreign language skills, Gazzola and Mazzacani (Citation2019) show that very good skills in English as a foreign language are associated with a higher probability of employment for natives in Germany, Italy, and Spain. Since only natives were considered within this study, it is unclear whether these results are also valid for the immigrant population.

Despite the underlying diversity in study designs, methods, and implemented theoretical approaches, empirical research agrees that literacy skills within the specific languages may positively influence labor market outcomes. Thus far, no study simultaneously considers the immigrants’ literacy skills in the majority, heritage, and foreign languages, as suggested by FoM, in relation to the labor market outcomes. Therefore, the economic value of multiliteracy as human capital remains undiscovered.

Research questions

The current study investigates the interrelation between multilingual literacy skills in first-generation adult immigrants in Germany and their employment status. We draw on the data of the LEO 2018 study that has a sample representative for the German-speaking, working-age population in Germany. In the theoretical foundation of the current study, we bridge the FoM (Cenoz and Gorter Citation2011) and the human capital theory (Becker Citation1964) to provide a resources-oriented perspective on multiliteracy as human capital. While taking the resource-oriented lens on immigrants’ multilingual literacy skills, our study aimed to answer the following research questions:

What multilingual profiles can be distinguished among adult immigrants in Germany, and how do they differ by the level of multiliteracy?

What is the relationship between adult immigrants’ level of multiliteracy and their employment status?

Project

The current study conducts secondary data analyses of the German large-scale literacy assessment ‘LEO Survey 2018 – Living with Low Literacy’ (LEO 2018), funded by the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (Grotlüschen and Buddeberg Citation2020). The overall sample consists of 7,192 cases. It is a representative study for the German-speaking population living in private households aged between 18 and 64 years. The study focuses on literacy assessment in the majority language – German, supplemented by an extensive questionnaire covering four domains of practices and competences: health, politics, financial, and digital (Buddeberg et al. Citation2021).

Measures

Multiliteracy skills

Self-assessment scales were used as a proxy for literacy skills. These scales were only administered for heritage and foreign languages and are based on the following descriptors of competence: ‘I understand and speak only single words and phrases (1)’, ‘I understand common expressions and can communicate in everyday situations (2)’, ‘I can understand most things, actively participate in conversations and write simple texts (3)’, and ‘I can read and write demanding texts. I have almost complete command of the language (4)’. This scale thus refers both to the mastery of the oral language and to mastery of the oral and written language as a higher literacy level. The questionnaire was presented in the German language. For those who have not learned/acquired the respective language, the values were set to ‘not acquired (0)’. The scale represents a short version of the scales developed by Klinger (Citation2022) based on the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (Council of Europe Citation2020) which proved to produce a highly reliable assessment of language skills in immigrant populations. Although self-assessments are only ad hoc subjective estimates provided by the participants, they are widely used in large-scale research designs and were reported to show high correlations with objective language data gathered by language tests (Edele et al. Citation2015; Gazzola and Mazzacani Citation2019; Klinger Citation2022).

Employment status

Participants were asked about their employment status. We computed a binary variable with the category ‘employed (1)’ comprised of participants who are full-time or part-time employed or on parental leave and the category ‘unemployed (0)’ comprised of unemployed participants who are capable of working as well as participants who take care of their household in full time. We excluded participants who were incapacitated or retired, in vocational training or internship, and participants with another, no further described, status (about 20% of the sample).

Educational background

The participants were asked about their highest school degree. We deployed the ordinal variable about the participants’ educational level with the categories ‘no degree (0)’, ‘low (1)’, ‘medium (2)’, and ‘high (4)’ provided by the authors of the LEO 2018 study. For participants still in the school system, we set a missing value.

Gender

The participants were categorized as either ‘male (1)’ or ‘female (2)’. Age. Participants were asked about their year and month of birth.

Sample

In order to analyze multiliteracy in adult immigrants’ multilingual skills, we used data from the LEO 2018 study (Grotlüschen and Buddeberg Citation2020). The sample under study consists of n = 451 German-speaking first-generation adult immigrants from age 18 to 64. The LEO-study was designed to provide a reliable empirical estimator for the number of functional analphabets in the German population aged between 18 and 64 (Bilger and Strauß Citation2020). The sample’s representativeness was achieved through the a priori sample design and a posteriori sample’s weighting and calibration. For the current study, we used weighted case counts provided by the authors of the LEO study to ensure our models provide unbiased estimations of the population parameters for first-generation immigrants in Germany. To ensure the samples’ representativeness for Germany, we used the weighted case counts, as provided by the authors of the LEO study (Bilger and Strauß Citation2020). reveals the sample’s descriptive statistics without case weighting. Due to the ordinal nature and non-normality of the self-assessment scales for language skills, we rely on non-parametric statistics for all variables under study. Within the sample, the proportion of females is 60.3%, the median age is 39 with a range of 46 years, the median educational level is ‘medium’, and 60.5% of the participants are considered ‘employed’. All participants reported to have a heritage language other than German and learned German as a foreign language to some degree. Approximately fifty-eight percent (57.8%) of them also learned English as a foreign language. A small share of participants reported having even more extensive language repertoires with a second heritage language (22.3%) and a foreign language other than English (30.4%). Regarding participants’ median language proficiency, first-generation adult immigrants in Germany have high literate skills in their first heritage language (‘can read and write demanding texts’) and low literate skills in German as a foreign language (‘can understand most things, actively participate in conversations and write simple texts’). The median for English as a foreign language is at the oral proficiency level (‘can understand and speak only single words and phrases’). Regarding a second heritage language or a foreign language other than English, the median proficiency level is ‘not skilled’ due to the small share of participants with such extensive language repertories.

Table 1. Sample statistics (n = 451).

Analytic strategy

The conducted data analysis consists of two parts. In the first step, we analyzed the level of multilingual skills in first-generation immigrant adults in Germany. We estimated multilingual profiles based on participants’ answer patterns on the self-assessment scales of language skills using latent class analysis (LCA). LCA is a model-based latent clustering approach to detect unobserved homogeneous subgroups of people based on observed indicator variables (Lazarsfeld and Henry Citation1968). This approach is particularly suitable for analyzing multilingual skills as suggested by FoM since it considers multilingual skills in their complexity and takes account of all languages in a multilingual repertoire. In order to deal with missing data in the LCA, we used full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML; Muthén, Kaplan, and Hollis Citation1987) in Mplus 8.2 for model parameter estimation, and a maximum likelihood algorithm producing robust standard errors (MLR) even under normal distribution deviation of the observed variables. This approach allowed us to use the overall sample of 451 participants for model estimation.

In the second step, we analyzed the effect of immigrants’ multiliteracy on their probability of employment in the German labor market. We estimated a series of logistic regression models with employment status as the binary dependent variable and multiliteracy as the independent variable accompanied by other covariates using SPSS 28. We used the multiple imputations approach to deal with missing values on the independent variables (Schafer and Graham Citation2002). We report the pooled results of n = 30 imputed datasets (Rubin Citation1987). We did not impute missing values on the dependent variable because we generated them ourselves during construction to exclude them from analysis (see measures section). Therefore, the sample for this analysis was reduced to n = 361 cases. In order to ensure the sample representativeness, we used the weighted case counts, as provided by the authors of the LEO study (Bilger and Strauß Citation2020).

Results

In the following, we report results on multilingual profiles in first-generation adult immigrants in Germany and their role in predicting the immigrants’ employment status.

Multiliteracy in multilingual profiles

The first aim of our study was to explore substantial subgroups in the population of first-generation adult immigrant adults in Germany regarding different multiliteracy profiles of multilingual skills. To this end, a latent class analysis (LCA) clustering approach was applied. We estimated a series of models with k = 1 to k = 5 classes and compared them by their model fit statistics (see ; Collins and Lanza Citation2010).

Table 2. Model fit indices.

According to the criteria revealed in , we favor the 2-class model. Therefore, we distinguished between two subgroups of first-generation adult immigrants in Germany concerning their multilingual profiles. Regarding the profiles’ prevalence in the population, i.e. probability of latent class membership, 40.6% of the adults are assigned to Profile A, and 59.4% are assigned to profile B. Thus, first-generation adult immigrants in Germany are more likely to have multilingual proficiency according to Profile B as compared to Profile A.

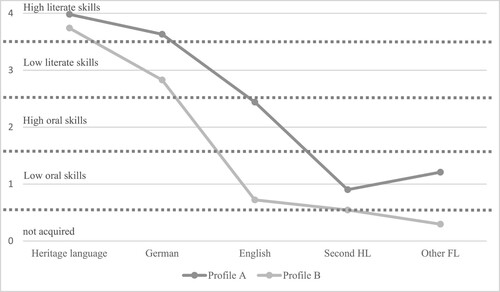

plots the two estimated multilingual proficiency profiles based on the expected values within each profile. These class-specific expected values are calculated from the class-specific item-response probabilities and represent the most likely response within the profiles on the original item scale. However, since the expected values are derivates from item-response probabilities, they are not restricted to integers and could take values between the original scale categories. The horizontal axis contains the languages in the adults’ language repertoire: first heritage language, German, English, second heritage language, and another foreign language. The vertical axis shows the language ability level plotted based on the categories of the self-assessment scales.

Figure 1. Expected values for the indicator variables conditional to class membership.

Note. The x axis represents immigrants’ languages. The y axis shows immigrants’ proficiency in each of the languages.

Within the two profiles, the results reveal the same ranking of languages by proficiency in three languages: adults show the highest language skills in the first heritage language, followed by German and English.

Profile A (‘higher multiliteracy’)

Members of this profile are expected to have high literacy in their first heritage language and German and high oral skills in English (acquired by 77.5% of the first-generation adult immigrants). Language skills in the second heritage language (acquired by 27.7%) and another foreign language (acquired by 48.9%) are only expected to be on a low oral proficiency level. Therefore, the multiliteracy of this profile encompasses two languages, the first heritage language and German, both on a high level.

However, with an increasing share of first-generation adult immigrants who never acquired an additional language, the proficiency level estimated by the model for the population could severely underestimate the actual skills’ level of those who learned additional languages: For the 77.5% of first-generation adult immigrants who learned English, the median is ‘low literate skills (3)’, with 71.9% of immigrants being literate in this language. For the 27.7% of first-generation adult immigrants who learned a second heritage language, the median is ‘high literate skills (4)’, with 97.9% of immigrants within this category. For the 48.9% of first-generation adult immigrants who learned another foreign language, the median is ‘low literate skills’, with 55.2% being at the literate skills levels. Thus, the actual multiliteracy may be higher than estimated by the model.

Profile B (‘lower multiliteracy’)

Members of this multilingual proficiency profile are expected to have high literacy in their first heritage language and low literacy in German. In English (acquired by 33.3%) and another foreign language (acquired by 12.0%), they are expected to have low oral skills, and a second heritage language is not expected to be acquired (acquired by 15.5%). Therefore, the multiliteracy of this profile encompasses two languages, the first heritage language, and German, on a high and a low level, respectively.

Again, the model might have underestimated the proficiency level of those who actually acquired an additional language: The median for that 33.3% who learned English is ‘high oral skills (2)’, with 29.7% being literate in this language. The median for that 12.0% who learned another foreign language is ‘low oral skills (1)’, with 43.5% being literate in this language. The median for that 15.5% who acquired a second heritage language is ‘low literate skills (3)’, with 63.8% being literate in this language.

Comparison between Profiles A and B

Between the profiles, there is a non-overlapping ordering of language skills. This pattern indicates that first-generation adult immigrants differ by their overall language skills’ level and that language skills within the profiles are positively correlated. The differences between the profile are all significant, with a small difference (Cohen Citation1988) for the first heritage language (MRang,ProfileA = 479.86, MRang,ProfileB = 399.81, U = 72917.00, Z = −8.227, p < 0.001, η = 0.280) a large difference for German (MRang,ProfileA = 590.15, MRang,ProfileB = 323.55, U = 33558.50, Z = −16.586, p < 0.001, η = 0.566), a large difference for English (MRang,ProfileA = 583.82, MRang,ProfileB = 293.33, U = 21825.00, Z = −18.180, p < 0.001, η = 0.639), a small difference for the second heritage language (MRang,ProfileA = 470.54, MRang,ProfileB = 406.09, U = 71154.00, Z = −5.306, p < 0.001, η = 0.181), and a large difference for another foreign language (MRang,ProfileA = 530.07, MRang,ProfileB = 357.48, U = 51230.50, Z = −12.703, p < 0.001, η = 0.436).

Concerning between-profile differences in background characteristics, 93.0% of the first-generation adult immigrants in Profile A are employed compared to 74.9% in Profile B which corresponds to a small difference (χ2 [1, n = 764] = 40.506, p < 0.001, φ = 0.230). The gender ratio does not significantly differ between the profiles with 60.8% females in Profile A and 60.0 females in Profile B (χ2 [1, n = 868]= 3.252, p = 0.071, φ = 0.061. The median age of 38.3 in Profile A and 41.6 years in Profile B differ significantly, corresponding to a small difference (MRang,ProfileA = 370.31, MRang,ProfileB = 473.49, U = 68118.00, Z = −5.965, p < 0.001, η = 0.203). The difference in the educational level of a median of ‘high (3)’ in Profile A and ‘low (1)’ in Profile B is significant and corresponds to a large difference (MRang,ProfileA = 559.54, MRang,ProfileB = 337.29, U = 41710.50, Z = −13.714, p < 0.001, η = 0.470).

Multiliteracy and the probability of being employed

The second research question of the current study aimed at clarifying the relation between multiliteracy in first-generation adult immigrants and their employment status. shows the results of four logistic regression models.

Table 3. Logistic regression (odds ratios). Pooled weighted results for n = 30 imputed datasets.

Model 1 serves as a baseline model in which we account for characteristics assumed to affect a persons’ employment probability. We account for gender, age, and educational level. The model is statistically significant, χ2(4, n = 361) = 35.938, p = <.001, explains 7.8% of the (pseudo) variance (Nagelkerke Pseudo-R2 = .078). First-generation immigrant females show a 60.1% decreased probability (odds ratio = .399, p = <.001) of being employed than their male counterparts of the same age and education, reflecting the known gender inequality in labor market participation. Concerning age, there is a tendency for older age groups to have an increased employment probability than the youngest group of 18–29 years old. However, the effects are not significant. High-educated first-generation immigrant adults have a 164% increased employment probability (odds ratio = 2.635, p = <.001) than their low-educated counterparts. Persons with medium education also tend to have such an advantage, but small and insignificant.

Model 2 contains immigrants’ multiliteracy as a predictor for employment. The model is statistically significant, χ2(1, n = 361) = 47.139, p = <.001, and explains 10.1% of the (pseudo) variance. The odds ratio of .205 (p = <.001) means that immigrants with higher multiliteracy (Profile B) have a 79.5% increased probability of being employed than immigrants with lower multiliteracy (Profile A).

Model 3 combines the previous models to investigate the effects’ stability, mainly whether multiliteracy retains the independent effect on employment probability when controlling for the other predictors. The model is statistically significant, χ2(7, n = 361) = 73.828, p = <.001, and explains 15.6% of the (pseudo) variance. As a result, the effect increases to 80.9% (odds ratio = .191, p = <.001) better chance of employment for higher multiliterate persons when controlling for their gender, age, and education. Accounting for the multiliteracy of the first immigration adults also affects the sizes of the employment odds ratios of the other model variables. Whereas females’ lower chance of employment does not change when controlling for multiliteracy, the positive age effect strengthens and becomes partly significant. The groups of 30–39 years old and 50–64 years old having a 94.3% (odds ratio = 1.943, p = .030) and a 112.5% (odds ratio = 2.125, p = .022) increased employment probability, respectively, compared to the group of 18–29 years old. Accounting for multiliteracy also considerably affects the odds ratios of education on employment probability. The advantage of a high level of education renders in half and becomes insignificant compared to a low level of education. However, this change does not mean that the level of education does not affect employment probability when controlling for a person’s multiliteracy. It rather shows that the effect is indirect: education influences multiliteracy, which, in turn, has an effect on adults’ occupations.

Model 4 investigates the independent (partial) effects of literacy in each language in multilingual repertoires on employment probability. This analytic strategy seeks to isolate the net effects of each language statistically rather than to model the holistic effects of the multilingual profiles prevalent in the population under study. The model is statistically significant, χ2(9, n = 361) = 103.879, p = <.001, and explains 21.6% of the (pseudo) variance. As a result, we found independent positive effects of being literate for each language. First-generation immigrant adults show an increased probability of employment when they are literate in German (456% increased probability, odds ratio = 5.560, p < .001), English (125% increased probability, odds ratio = 2.252, p = .010), and the first heritage language (284% increased probability, odds ratio = 3.845, p = .014).

Discussion

The current study investigated the relationship between multilingual literacy skills and the employment status of first-generation adult immigrants in Germany. In the theoretical framework, we combined the FoM (Cenoz and Gorter Citation2011) with the human capital theory (Becker Citation1964). This interdisciplinary approach served as the rationale for our resource-oriented perspective on immigrants’ multilingual skills as human capital in Germany: Both, multiliteracy as a set of interrelated skills and skills in the individual languages of a person’s multilingual repertoire may bring incentives for the individuals in terms of labor market outcomes.

While taking the resource-oriented lens on immigrants’ multilingual literacy skills, our study aimed to answer the two research questions:

What multilingual profiles can be distinguished among adult immigrants in Germany, and how do they differ by the level of multiliteracy?

What is the relationship between immigrant adults’ multiliteracy and their employment status?

We used data from the German LEO 2018 study (Grotlüschen and Buddeberg Citation2020) for first-generation immigrants (n = 451, age 18–64). To analyze the level of multilingual literacy skills in first-generation adult immigrants in Germany, we estimated multilingual profiles based on participants’ answer patterns on the self-assessment scales of language skills using LCA analysis. In a second step, we analyzed the effect of immigrants’ multiliteracy on their probability of employment in the German labor market. We conducted series of logistic regression models with employment status as the binary dependent variable and multiliteracy as the independent variable accompanied by other covariates (age, gender, and education).

Regarding the first research question, we found two multilingual profiles with different levels of multilingual literacy skills in first-generation adult immigrants in Germany. Profile A (‘higher multiliteracy’) and Profile B (‘lower multiliteracy’). Both profiles show that within the adult German-speaking population in Germany, first-generation adult immigrants may possess up to 5 languages developed to different skills level. The higher multiliteracy skills were found within Profile A, whereas Profile B showed lower multiliteracy. The profiles differed by the level of literacy skills in all investigated languages, and the language skills within the profiles were positively correlated, thereby showing a remarkable non-overlapping language ordering pattern. These findings are in line with the results of a previous study (Usanova and Schnoor Citation2021) that, based on the actually measured language data, has found non-overlapping high and low-literacy profiles of multilingual writing skills in second-generation immigrants in Germany. Both studies provide evidence that literacy skills within multilingual repertoires may represent an interrelated entity: better-developed skills in one language go side by side with better-developed skills in all other languages of immigrants’ multilingual repertoires. Considering the combined results from the current study on first-generation immigrants and the results by Usanova and Schnoor (Citation2021) on second-generation immigrants, these patterns may persist across generations. All more attention should be paid to exploring the potential of literacy skills in multilingual repertoires to represent shared resources that may strengthen a person's overall multiliteracy (Agirdag Citation2014a; Citation2014b; Gándara Citation2018). However, good language skills in the heritage language do not per se guarantee good language skills in the other languages (Profile B). Since first-generation immigrants still make up the largest share of the low-literate group in Germany compared to second-generation immigrants and natives (Heilmann and Grotlüschen Citation2020), and, as our study shows, this trend is not attributable to heritage language skills, further research should focus more on the social background factors that may lead immigrants to this disadvantage (Nauck & Schnoor Citation2015). Notably, studies on adults with low literacy skills usually explore native speakers of the language of testing, or adults who grew up with this language, in addition to other languages (e.g. Bar-Kochva et al. Citation2021; Braze et al. Citation2016). Hence, further studies characterizing factors associated with low literacy among first-generation immigrant are essential in order to have a better representation of the population of adults with poor literacy skills.

Regarding the second research question, the results gained from the logistic regressions show that multiliteracy in first-generation immigrants may represent human capital in Germany. After controlling for the additional variables (age, gender, education), the analysis shows that higher multiliteracy, as found in Profile A, increases the probability of adult immigrants’ employment. Furthermore, our analysis shows independent positive effects of literacy in each language in multilingual repertoires on employment probability. Overall, these findings reveal the valuable potential of the actual multilingual profiles to serve as an economic resource for first-generation immigrants in Germany. Thus, our results support previous research that has shown positive evidence for the bilingual heritage and majority languages (Agirdag Citation2014a; Citation2014b; Rumbaut Citation2014) and foreign languages (Gazzola and Mazzacani Citation2019; Hahm and Gazzola Citation2022) representing human capital. While combining FoM (Cenoz and Gorter Citation2011) with the human capital theory (Becker Citation1964), our study enhances previous findings by showing that, with higher literacy skills, the whole multilingual language repertoire may represent human capital to first-generation immigrants in Germany. This finding highlights the need for genuinely multilingual language policies that aim at fostering the majority, heritage, and foreign language skills (Van der Worp, Cenoz, and Gorter Citation2018).

Overall, while considering language as human capital in immigrants, further research should take into account skills in particular languages as well as language-overarching skills provided by the whole multilingual repertoires. The most prominent finding of our study suggests that alongside the majority and the foreign languages, literacy skills in heritage languages need to be considered as an important determinant of first-generation immigrants’ employability. Further research needs to address how the valuable potential of these skills can be flexibly used as a direct response to labor market demands across or within specific job sectors contributing to productivity through multiskilling.

Limitations

It is important to mention the following limitations of our study. First, we could only use data from self-assessments to approximate adults’ multiliterate skills. Since the LEO study’s primary research interest was literacy in German as the majority language, tests were only conducted for German. Information about additional language skills was gathered in the questionnaire. Although fine-graded self-assessments based on specific linguistic actions (‘can-do’-indicators) provide reliable estimates for foreign language skills (Hahm and Gazzola Citation2022), the present results are probably affected by an overestimation of heritage language skills, as a large proportion of participants self-reported their heritage language skills as being on the highest literacy level. Klinger (Citation2022) has already reported this ceiling effect for monolingual German adults overestimating their German skills. Thus, ‘can-do’ self-assessments seem not to provide enough variance in the languages where participants develop high proficiency levels and, therefore, need to be adjusted by integrating additional items that allow more differentiation of skills at higher proficiency levels. Regarding the effect of multiliteracy on employment probability investigated in our study, it has to be expected that a finer-graded assessment of high literacy skills would sharpen the effect size because of decreased measurement error due to the more efficient allocation of participants to literacy levels. Therefore, it will be beneficial for further research to investigate the role of language skills as human capital by analyzing language test data instead of self-assessments.

Second, due to filtering in the questionnaire, the self-assessments on German (as a foreign language) were only presented to first-generation immigrants. Hence, we could not extend our analyses to second-generation immigrants.

Third, the instruments (‘can-do’ self-assessments) used in the LEO study that we draw on to capture multiliteracy were originally designed to measure skills in each language separately, which contradicts the holistic view of multiliteracy as suggested by FOM. However, we tried to leverage this disadvantage at the level of data analysis. The latent class analysis (LCA) allowed us to analyze literacy skills in all languages holistically by modeling them simultaneously. This approach is particularly suitable for analyzing multilingual skills since it approximates FOM requirements for large-scale survey data. However, this approach is rather heuristic, and future research should find ways to develop tests that measure multiliteracy holistically in large-scale designs. The challenge to move away from a decontextualized and simplified view of multiliteracy to find the approaches to capture the contextualized situated multilingual literacy practices in large-scale services is a desideratum for future research.

Fourth, our study focused only on multiliteracy. The found ‘high’ and ‘low’ multiliteracy profiles may differ in terms of many characteristics besides multiliteracy (e.g. identities, migration history, work experience, job branches, income level, etc.), which may influence multiliteracy but were not addressed in the current study. Future research should investigate the effects of social background characteristics on multiliteracy, zooming into the complex identities and conditions of the individuals behind the profiles.

Fifth, analyzing employment status only covers one aspect of a person’s employability. However, it is also essential to investigate whether better-developed multiliteracy, alongside higher occupational chances, may bring benefits to immigrants in terms of earnings or whether these skills are just taken for granted by their employers (Civico and Grin Citation2020; Grin, Sfreddo, and Vaillancourt Citation2010). This desideratum will be addressed in our further research.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Ethics approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Irina Usanova

Irina Usanova is a post-doc researcher at the Institute of General, Intercultural and International Comparative Education at the University of Hamburg, Germany. She is the project leader of the junior research group ‘Multiliteracy as a resource for the labor market. Social conditions and transformability into economic capital (MARE)’ funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. Her research focuses on multilingual reading and writing skills, human capital, and heritage language maintenance.

Birger Schnoor

Birger Schnoor is a post-doc researcher at the Institute of General, Intercultural and International Comparative Education at the University of Hamburg, Germany. He is member of the junior research group ‘Multiliteracy as a resource for the labor market. Social conditions and transformability into economic capital (MARE)’ funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research. His research interests include multiliteracies in adolescence, educational investments, and economic returns on education.

Irit Bar-Kochva

Irit Bar-Kochva is a professor for language basic education and literacy skills at the German Institute for Adult Education (DIE) – Leibniz Centre for Lifelong Learning and the University of Cologne. Her academic training is in psychology, with a focus on learning and learning disabilities (Goethe University and DIPF- Leibniz-Institute for Research and Information in Education, Germany; University of Haifa and Ben-Gurion University, Israel). In her research, she addresses the following subjects: Developmental aspects of literacy acquisition, cognitive skills related to reading and writing proficiencies and diagnostic and intervention in learning difficulties. She applies a lifelong perspective, while exploring the literacy skills of various age groups – from kindergarten and school children to adolescents and adults. Another research interest is the study of orthography-general and orthography-specific aspects of reading and writing skills. In the recent years, she has been focusing on the study of adults with low literacy skills. Current research interest relates to the characteristics of these adults, their needs as adult learners, and how effective intervention aimed at improving their literacy skills could be provided. She applies quantitative research methods using mainly behavioral measures from the field of psycholinguistics and skill-evaluation.

Hannes Schröter

Hannes Schröter is head of the research department ‘Teaching, Learning, Counselling’ at the German Institute for Adult Education – Leibniz Centre for Lifelong Learning (DIE) and professor for ‘Adult Cognition and Learning’ at the FernUniversität in Hagen, Germany. The cognitive psychologist's work focuses on the basic language education of adults, the professional competencies of (language) teachers and the development of digital teaching/learning tools.

References

- Agirdag, O. 2014a. “The Long-Term Effects of Bilingualism on Children of Immigration: Student Bilingualism and Future Earnings.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 17 (4): 449–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2013.816264.

- Agirdag, O. 2014b. “The Literal Cost of Language Assimilation for the Children of Immigration: The Effects of Bilingualism on Labor Market Outcomes.” In The Bilingual Advantage: Language, Literacy and the US Labor Market, edited by M. C. Rebecca and C. G. Patricia, 160–181. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781783092437-008.

- Alarcón, A., A. Di Paolo, J. Heyman, and M. C. Morales. 2014. “The Occupational Location of Spanish-English Bilinguals in the New Information Economy: The Health and Criminal Justice Sector in the US Borderlands with Mexico.” In The Bilingual Advantage: Language, Literacy and the US Labor Market, edited by R. M. Callahan and P. C. Gándara, 112–139. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781783092437-006.

- Aldashev, A., J. Gernandt, and S. L. Thomsen. 2009. “Language Usage, Participation, Employment and Earnings: Evidence for Foreigners in West Germany with Multiple Sources of Selection.” Labour Economics 16 (3): 330–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2008.11.004.

- Arias-Hermoso, R., and A. Imaz Agirre. 2023. “Exploring Multilingual Writers in Secondary Education: Insights from a Trilingual Corpus.” European Journal of Applied Linguistics. https://doi.org/10.1515/eujal-2023-0022.

- Bar-Kochva, I., R. Vágvölgyi, T. Dresler, B. Nagengast, H. Schröter, J. Schrader, and H.-C. Nuerk. 2021. “Basic Reading and Reading-Related Language Skills in Adults with Deficient Reading Comprehension who Read a Transparent Orthography.” Reading and Writing 34 (9): 2357–2379. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-021-10147-4.

- Becker, G. S. 1964. Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, with Special Reference to Education. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Bilger, F., and A. Strauß. 2020. “Studiendesign, Durchführung und Methodik der LEO-Studie 2018.” In LEO 2018: Leben mit geringer Literalität, edited by A. Grotlüschen and K. Buddeberg, 79–114. Bielefeld: WBV.

- Blake, C. D., and D. R. Walter. 2021. “Heritage Language Labor Market Returns: The Importance of Speaker Density at the State Level.” Journal of Economics, Race, and Policy 4 (4): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41996-020-00060-3.

- Bourdieu, P. 1977. “The Economics of Linguistic Exchanges.” Social Science Information 16 (6): 645–668. https://doi.org/10.1177/053901847701600601.

- Braze, D., L. Katz, J. S. Magnuson, W. E. Mencl, W. Tabor, J. A. Van Dyke, and D. P. Shankweiler. 2016. “Vocabulary Does not Complicate the Simple View of Reading.” Reading and Writing 29 (3): 435–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-015-9608-6.

- Breton, A. 1978. “Nationalism and Language Policies.” The Canadian Journal of Economics / Revue Canadienne D'Economique 11 (4): 656–668. https://doi.org/10.2307/134371.

- Buddeberg, K., G. Dutz, L. Heilmann, C. Stammer, and A. Grotluschen. 2021. “Participation and Independence with Low Literacy: Selected Findings of the LEO 2018 Survey on Low Literacy in Germany.” Adult Literacy Education: The International Journal of Literacy, Language, and Numeracy 3 (3): 19–34. https://doi.org/10.35847/KBuddeberg.GDutz.LHeilmann.CStammer.AGrotluschen.3.3.19.

- Cenoz, J., and D. Gorter. 2011. “Focus on Multilingualism: A Study of Trilingual Writing.” The Modern Language Journal 95 (3): 356–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2011.01206.x.

- Chiswick, B. R., and P. W. Miller. 2014. “International Migration and the Economics of Language.” IZA Discussion Paper No. 7880. Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA).

- Chiswick, B. R., and G. Repetto. 2001. “Immigrant Adjustment in Israel: The Determinants of Literacy and Fluency in Hebrew and Their Effects on Earnings.” In International Migration: Trends, Policies and Economic Impact, edited by S. Djajic, 204–228. Bonn: Routledge.

- Civico, M., and F. Grin. 2020. “Language Economics: Overview, Applications and Recent Methodological Developments.” In Language and Economy: Language Industries in a Multilingual Europe, edited by Tõnu Tender, and L. M. Eichinge, 73–87. http://archive-ouverte.unige.ch/unige:142439.

- Cohen, J. 1988. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. New York: Routledge.

- Collins, L. M., and S. T. Lanza. 2010. Latent Class and Latent Transition Analysis: With Applications in the Social, Behavioral, and Health Sciences. Hoboken: Wiley.

- Cope, B., and M. Kalantzis. 2009. ““Multiliteracies”: New Literacies, New Learning.” Pedagogies: An International Journal 4 (3): 164–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/15544800903076044.

- Council of Europe. 2020. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

- Dustmann, C. 1994. “Speaking Fluency, Writing Fluency and Earnings of Migrants.” Journal of Population Economics 7 (2): 133–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00173616. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20007428.

- Edele, A., J. Seuring, C. Kristen, and P. Stanat. 2015. “Why Bother with Testing? The Validity of Immigrants’ Self-Assessed Language Proficiency.” Social Science Research 52: 99–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.12.017.

- Gándara, P. 2018. “The Economic Value of Bilingualism in the United States.” Bilingual Research Journal 41 (4): 334–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/15235882.2018.1532469.

- Gazzola, M., and D. Mazzacani. 2019. “Foreign Language Skills and Employment Status of European Natives: Evidence from Germany, Italy and Spain.” Empirica 46 (4): 713–740. https://doi.org/10.1007/s1f0663-019-09460-7.

- Gogolin, I. 2018. “Literacy and Language Diversity: Challenges for Education Research and Pracitce in the 21st Century.” In Global Perspectives on Education Research, edited by L. D. Hill and F. J. Levine, 3–25. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351128421-1.

- Gogolin, I., S. McMonagle, and T. Salem. 2019. “Germany: Systemic, Sociocultural and Linguistic Perspectives on Educational Inequality.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Race and Ethnic Inequalities in Education, edited by P. A. J. Stevens and A. G. Dworkin, 557–602. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-94724-2_14.

- Grin, F., C. Sfreddo, and F. Vaillancourt. 2010. The Economics of the Multilingual Workplace. New York: Routledge.

- Grotlüschen, A., and K. Buddeberg. 2020. LEO 2018 – Leben mit Geringer Literalität. WBV Media GmbH & Co. KG. https://doi.org/10.3278/6004740w.

- Hahm, S., and M. Gazzola. 2022. “The Value of Foreign Language Skills in the German Labor Market.” Labour Economics 76: 102150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2022.102150.

- Heilmann, L., and A. Grotlüschen. 2020. “Literalität, Migration und Mehrsprachigkeit.” In LEO 2018. Leben mit geringer Literalität, edited by G. Anke and K. Buddeberg, 115–143. Bielefeld: WBV Media GmbH & Co. KG.

- Heller, M. 2003. “Globalization, the new Economy, and the Commodification of Language and Identity.” Journal of Sociolinguistics 7 (4): 473–492. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9841.2003.00238.x.

- Heller, M. 2010. “The Commodification of Language.” Annual Review of Anthropology 39 (1): 101–114. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.012809.104951.

- Klinger, T. 2022. “Die Selbsteinschätzung von Sprachfähigkeiten: Eine Skala zur differenzierten Erfassung.” In Sprachentwicklung im Kontext von Mehrsprachigkeit: Hypothesen, Methoden, Forschungsperspektiven, 1st ed., edited by T. Klinger, I. Gogolin, and B. Schnoor, 79–112. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden GmbH; Springer VS.

- Lazarsfeld, P. F., and N. W. Henry. 1968. Latent Structure Analysis. New York: Houghton Mifflin.

- Muthén, B. O., D. Kaplan, and M. Hollis. 1987. “On Structural Equation Modeling with Data That are not Missing Completely at Random.” Psychometrika 52 (3): 431–462. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02294365.

- Nauck, B, and B Schnoor. 2015. “Against all odds? Bildungserfolg in vietnamesischen und türkischen Familien in Deutschland.” KZfSS Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 67 (4): 633–657. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11577-015-0345-2.

- The New London Group. 1996. “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures.” Harvard Educational Review 66 (1): 60–92. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.66.1.17370n67v22j160u.

- Orcasitas-Vicandi, M. 2022. “Towards a Multilingual Approach in Assessing Writing: Holistic, Analytic and Cross-Linguistic Perspectives.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 25 (6): 2186–2207. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2021.1894089.

- Riehl, C. M. 2021. “The Interplay of Language Awareness and Bilingual Writing Abilities in Heritage Language Speakers.” Languages 6 (2): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages6020094.

- Rubin, D. B. 1987. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: Wiley.

- Rumbaut, R. G. 2014. “English Plus: Exploring the Socioeconomic Benefits of Bilingualism in Southern California.” In The Bilingual Advantage: Language, Literacy and the US Labor Market, edited by M. C. Rebecca and C. G. Patricia, 182–208. Multilingual Matters. https://doi.org/10.21832/9781783092437-009.

- Schafer, J. L., and J. W. Graham. 2002. “Missing Data: Our View of the State of the Art.” Psychological Methods 7 (2): 147–177. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147.

- Schnoor, B., and I. Usanova. 2022. “Multilingual Writing Development: Relationships Between Writing Proficiencies in German, Heritage Language and English.” Reading and Writing. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-022-10276-4.

- Shin, H.-J., and R. Alba. 2009. “The Economic Value of Bilingualism for Asians and Hispanics.” Sociological Forum 24 (2): 254–275. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40210401.

- Soltero-González, L., K. Escamilla, and S. Hopewell. 2012. “Changing Teachers’ Perceptions About the Writing Abilities of Emerging Bilingual Students: Towards a Holistic Bilingual Perspective on Writing Assessment.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 15 (1): 71–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2011.604712.

- Stammer, C. 2020. “Literalität und Arbeit.” In LEO 2018. Leben mit geringer Literalität, edited by G. Anke, and K. Buddeberg, 167–195. Bielefeld: WBV Media GmbH & Co. KG.

- Usanova, I., and B. Schnoor. 2021. “Exploring Multiliteracies in Multilingual Students: Profiles of Multilingual Writing Skills.” Bilingual Research Journal 44 (1): 56–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/15235882.2021.1890649.

- Usanova, I., and B. Schnoor. 2022. “Approaching the Concept of Multiliteracies: Multilingual Writing Competence as an Integrated Model.” Canadian Journal of Applied Linguistics 25 (3): 144–165. https://doi.org/10.37213/cjal.2022.32598.

- Van der Worp, K., J. Cenoz, and D. Gorter. 2018. “Multilingual Professionals in Internationally Operating Companies: Tensions in Their Linguistic Repertoire?” Multilingua 37 (4): 353–375. https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2017-0074.