ABSTRACT

This study aims to rethink the integration of spiritual care into healthcare in spiritually plural societies. Based on a systematic review of the theoretical literature, we analysed 74 studies and distinguish four positions regarding the integration of spiritual care into healthcare: generalist-particularists who see the spiritual domain as a field to be addressed by all professional caregivers and in which caregivers’ own spiritual orientations play a vital role; generalist-universalists who advocate for all caregivers to provide spiritual care regardless of their spiritual orientations; specialist-particularists who argue that experts should address the spiritual domain in light of their own spiritual orientations; and specialist-universalists who call for experts to provide spiritual care regardless of their spiritual orientations. We argue that these four positions give different weight to the professional, personal, and confessional roles of the spiritual caregiver. Acknowledging these positions is a prerequisite for future scenarios of integrating spiritual care into healthcare.

Introduction

Religion and spirituality play an important role in healthcare, both in the personal lives of many patients and professionals as well as an inspiration and motivational source for the delivery of healthcare (Jones & Pattison, Citation2013; Pattison, Citation2013). Over the past decade or two, several authors have argued for adjusting and extending the biopsychosocial model—which is an established model in healthcare that involves providing care for patients’ physical, psychological, and social lives (Engel, Citation1977)—to include the spiritual or existential domain (Chuengsatiansup, Citation2003; de Haan, Citation2017; Huber et al., Citation2016; Puchalski, Vitillo, Hull, & Reller, Citation2014; Sulmasy, Citation2002; WHO, Citation2002). In such a model, healthcare practitioners are to address the spiritual or existential domain as part of their patient-centred or whole-person-care, e.g., by focusing on answering questions like “to what extent do you find meaning in life?” or “how much are you able to feel peaceful when you need to?” or “how hopeful do you feel?” (WHOQOL SRPB Group, Citation2006, p. 1489).

The integration of the spiritual domain into healthcare raises questions concerning the proper profession responsible for this domain (Harding, Flannelly, Galek, & Tannenbaum, Citation2008, p. 116; Puchalski, Lunsford, Harris, & Miller, Citation2006; VandeCreek, Citation1999) and concerning the role of professional caregivers’ own orientation in addressing it (Fawcett & Noble, Citation2004; Pesut & Thorne, Citation2007). In addressing these questions, the spiritual and religious landscape plays a vital role. In the past decades Western societies have become pluralised. Processes of secularisation have led to a decrease of institutionalised religion, and, at the same time, processes of migration, globalisation, and the upsurge of new forms of spirituality and hybridity have led to a diversity of religious or spiritual positions (McGuire, Citation2008; Taylor, Citation2007; Vertovec, Citation2007; Woodhead, Partridge, & Kawanami, Citation2016). Consequently, professional caregivers increasingly care for patients and clients with a spirituality different from their own.

Whereas some see such encounters as possibilities for forming a “wonderful connection” or seeing the “beauty of multi-faith prayer” (Silton, Flannelly, Galek, & Fleenor, Citation2013), many others frame dealing with spiritual diversity as difficult or at least challenging. It may cause difficulties in decision-making processes in end-of-life care (Ai & McCormick, Citation2010), and conflict may arise between medical recommendations and patients’ religious beliefs (Bjarnason, Citation2009). Also, it may hinder adequate spiritual caregiving because of the risk of imposing one's own beliefs on patients (Silton et al., Citation2013), and because language and gender issues may be at stake (Anderson, Citation2004; Chaplin, Citation2003; Isgandarova & O’Connor, Citation2012). Additionally, spiritual diversity challenges the performance of rituals (Chaplin, Citation2003; Flatt, Citation2015) and prayer (Bueckert, Citation2009; Dijoseph & Cavendish, Citation2005; French & Narayanasamy, Citation2011; Grefe, Citation2011). Notwithstanding these critical views, the role of spiritual diversity in the integration of spiritual care into healthcare has hardly been examined.

The objective of this study is to describe the different perspectives on integrating spiritual care into healthcare in spiritually diverse societies. Understanding the implications of these plural contexts is necessary for the full integration of spiritual care into healthcare and medicine. This study therefore provides a framework useful for scholars investigating spiritual care in healthcare settings. In addition, it will support healthcare professionals, both generalists and specialists in spiritual care, to reflect on the role of spiritually diverse encounters in healthcare, and it will support policy makers to make informed decisions regarding organising and implementing spiritual care in healthcare.

In the following sections we will first describe the method and data-analysis used for this study, and then describe the field of spiritual care by looking at two central questions: (a) Who should provide spiritual care? and (b) What is the role of caregivers’ spirituality when providing spiritual care? We will identify four possible positions based on responses to these questions, and we will argue that each of these positions implies a different normative stance and has different implications for integrating spiritual care into healthcare and medicine.

Method

The basis for this study was formed by theoretical and conceptual literature published between 1 January 2000, and 18 January 2016, and identified via a systematic search, of which the empirical studies have been reviewed elsewhere (Liefbroer, Olsman, Ganzevoort, & Van Etten-Jamaludin, Citation2017). This systematic search focused on literature in which the terms “spiritual”, “care” and “interfaith” were used, and synonyms and closely related terms were used in the search as well (see Liefbroer et al., [Citation2017] for search strategy). Consequently, all forms of spiritual care by all disciplines are taken together in the analysis, even though their definitions of spiritual care may differ. Our objective was not to provide a systematic overview of this theoretical and conceptual literature but to use this theoretically, that is, in order to describe the different perspectives on integrating spiritual care into healthcare in a spiritually diverse landscape. Therefore, in addition to a total of 74 journal articles and book (chapters) identified via the systematic search, related literature found through snowball methods (e.g., by checking reference lists of identified literature [Greenhalgh & Peacock, Citation2005]) was included.

The literature was thematically analysed (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006), steered by our research objective. For each article or book (chapter) the first author (AIL) listed problems that were identified in the literature in relation to spiritual diversity in spiritual care, and/or solutions that were provided to those problems (see for an example of the data-analysis). The three authors together discussed the findings in order to identify central themes or questions that emerged in the data. They noticed that the problems and solutions often centred around two key questions, each one typically answered in two ways.

Table 1. Example of data-analysis.

Results

Spiritual care: two central questions

Who should provide spiritual care?

With the upsurge of biopsychosocio-spiritual (Pargament, Citation2007, p. x; Sulmasy, Citation2002) and holistic models (Rumbold, Citation2012), many advocate that all professional caregivers—i.e., nurses, psychologists, social workers, and doctors—should function as generalists and address the spiritual domain. Spirituality within this discourse is understood in universal terms, and often independent from (or even in negative terms in relation to) religion (Galashan, Citation2015, p. 105). Following terms of Swinton (Citation2010), Rumbold (Citation2012, p. 179) writes:

Spirituality is identified as a universal human characteristic, stripped of any particularities of content, class, culture, and religion. Just as psychological and social needs should be attended to in healthcare, so should spiritual needs be included. Spiritual care becomes something that should be available for all, for people of all faiths or none.

What is the role of caregivers’ spirituality when providing spiritual care?

The second question regards the professional caregiver's spirituality. Several authors take a particularist stance, highlighting the importance of caregivers’ own spiritual orientation in spiritual caregiving (Liefbroer et al., Citation2017). Historically, spiritual care in Western societies used to be provided by priests and clergy (men and women) visiting their parishioners (e.g., when hospitalised or in prison), and over the past decades chaplains were employed by organisations like healthcare institutions, the military, and prisons to provide spiritual care (Doolaard, Citation2006; de Groot, Citation2018, p. 115; Merchant & Wilson, Citation2010). Many chaplains were and continue to be trained at theological seminaries and faculties to provide spiritual care from the perspective of a particular tradition (Ganzevoort, Ajouaou, van der Braak, de Jongh, & Minnema, Citation2014); after being ordained by a specific religious (or Humanistic) institution, they often function as formal representatives of that tradition (de Groot, Citation2018, p. 115; Swift, Citation2013). Consequently, some chaplains emphasise the importance of their own spiritual orientation for spiritual caregiving (Abu-Ras & Laird, Citation2011; Liefbroer et al., Citation2017; Sinclair, Mysak, & Hagen, Citation2009). Meanwhile, other professional caregivers sometimes take this particularist stance as well. For instance, for some Christian nurses (Fawcett & Noble, Citation2004; Fraley, Theissen, & Jiwanlal, Citation2014) the caregiver's own spiritual orientation plays an important role for spiritual care provision.

Others take a universalist stance, characterised by a tendency to focus on generic, universal aspects of spiritual care provision and underlining the importance of caring for all patients regardless of the professional caregiver's or receiver's particular spiritual background (Liefbroer et al., Citation2017). For instance, many hospital chaplains are trained to provide spiritual care in a generic manner for patients of all spiritualities (Gatrad, Sadiq, & Sheikh, Citation2003), and strategies are used by these chaplains that facilitate a “broad approach to meaning making” (Cadge & Sigalow, Citation2013, pp. 156-157). This universalist stance is not limited to chaplains, as others argue psychologists and other healthcare providers to similarly address the spiritual needs of patients from a broad range of spiritualities—irrespective of the caregivers’ spiritual orientations (Pargament, Citation2007; Plante & Thoresen, Citation2012).

Central questions combined: a matrix

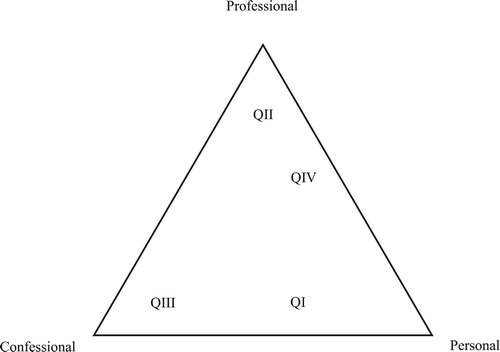

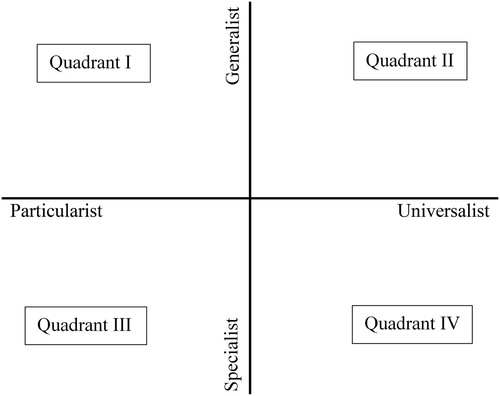

The answers to these two questions can be thought of as a continuum, with generalists and specialists on the ends of the continuum regarding the first question, and particularists and universalists regarding the second question. When combined in a matrix, four quadrants are distinguished ().

Figure 1. Schematic overview of quadrants in response to the question: Who should provide spiritual care? (vertical axis) and: What is the role of caregivers’ spirituality when providing spiritual care? (horizontal axis).

Quadrant I regards authors who view caregivers as generalist as well as particularist. Authors in this quadrant claim that all professional caregivers ought to provide some form of spiritual care and attend to the spiritual needs of spiritually diverse patient populations. Concerning the particularist position, they state that the caregiver's spirituality plays an important role in spiritual caregiving. For instance, when Fraley et al. (Citation2014, pp. 163-164) wonder to what extent nurses’ spiritual orientation should influence the way in which they provide spiritual care, they argue that telling the person “God loves you” (“but nothing more, unless the patient asked for more”) and prayer (either silent or out loud when a patient consents) are appropriate spiritual interventions.

Authors who position themselves in Quadrant II—holding both generalist and universalist views—often closely associate with terms such as holistic and whole-person care. As champions of the generalist position, they start from the assumption that all professional caregivers are expected to address the spiritual domain, and as proponents of the universalist view they argue that they have to do so regardless of their own spirituality. Advocates of this quadrant often provide guidelines for various caregivers on how to provide spiritual care and on how to discuss spiritual issues with a diverse patient population. Mathisen et al. (Citation2015), for example, describe strategies for speech-language pathologists to address spirituality in practice, no matter what the spiritual orientation of the caregiver is.

Quadrant III (specialist-particularist) implies that the spiritual domain is a field in which chaplains are experts (specialists), and in which the caregiver's spirituality relates to the way in which spiritual care provision takes place. Although this quadrant appears most frequently in chaplaincy literature (e.g., Bueckert, Citation2009; Flatt, Citation2015; Schipani, Citation2009, Citation2013), other professional caregivers sometimes take this perspective as well. Fleming (Citation2004, p. 57), for instance, describes how some argue to avoid the topic of spiritualty altogether because of “the danger of misunderstanding and offensiveness should physicians attempt to become spiritually involved with patients of a different belief system”.

Authors in Quadrant IV (specialist-generalist) see chaplains as experts in the field of spiritual caregiving. In contrast to those in Quadrant III, however, they argue that chaplains are expected to provide spiritual care to all clients regardless of the caregiver's spiritual orientation. Although not a radical universalist, the response by Monnett (Citation2005, p. 59) to the question whether a non-Christian, Buddhist chaplain can provide spiritual care for a Christian population, exemplifies this position:

… the role of the professional chaplain is not to proselytize a particular dogma but to stand with the patient[s] where they are and to help the patient[s] utilize their own spiritual views and beliefs as a resource for their own healing … they might find themselves ministering to a Wiccan, a Muslim, or a Native American as well as a Christian. Having some knowledge of the basic tenets of each of these traditions is a necessary prerequisite to helping the patient[s] to utilize their own resources in the healing process, whatever the chaplain's own personal beliefs might be. (italics original)

Professional, personal, and confessional roles in spiritual care

The ways in which caregivers respond to the challenge of integrating spiritual care in healthcare in a spiritually diverse landscape differ according to the position taken in the matrix (). In this section, we argue that these four positions are linked to regularly described roles in spiritual caregiving: the professional, the personal, and the confessional role (confessional here means in relation to a particular religious or world view tradition and community). These roles help to understand not only the interaction between patient and caregiver, but also the interaction between the caregiver and other professions, institutions, and communities.

In spiritual caregiving, caregivers constantly negotiate their role as professional caregiver, as person, and—especially for those ordained by a religious or Humanistic institution and/or working in religious organisations—as confessional caregiver (Bidwell & Marshall, Citation2006; Ganzevoort & Visser, Citation2007; Heitink, Citation2001). Each role reflects different relationships, respectively the relationship with the professional standards, the relationship with oneself, and the relationship with religious and non-religious institutions and/or the accompanying theological assumptions. Each role also assumes a different style and source of authority (following the distinction between traditional, rational-legal, and charismatic authority [Bacon & Borthwick, Citation2013; Weber, Citation1958]). The professional role relates to colleagues with the same profession, the professional codes and standards, and it says something about a position within the organisation, which means that authority of the caregiver is based on functional competence. Taking a personal role means that the caregiver builds on the connection with his or her own identity and private life and values personal authenticity, which may include feelings and private experiences. The confessional role implies the relationship with communities that confess the same values, like faith communities. This role stresses religious legitimation and the authority of the tradition.

The three roles and relations are given different weight within each of the quadrants. Every quadrant emphasises one or two roles and minimises the importance of the other role(s), and sometimes the other role(s) may even seem irrelevant (). Each quadrant thus takes a different normative stance in how they perceive the spiritual caregiver's identity. We will first describe for each quadrant which role or roles are given most weight, and then describe the critiques to those positions. Evidently, this is a theoretical model and in reality the quadrants, roles, and relationships may overlap. Nevertheless, for conceptual clarity they are distinguished now, helping to describe the different perspectives on integrating spiritual care into healthcare in spiritually diverse societies.

Generalist-particularists (QI): normative stance and critique

In this quadrant a caregiver's personal role is highly valued, as authors emphasise—for instance for nurses—“the value of the nurse's own spiritual resources and the importance of the whole nurse in giving spiritual care” (Fawcett & Noble, Citation2004, p. 140). The caregiver's integrity is central in this regard: “This attitude gives more freedom for nurses [to] relate to their patients with integrity instead of feeling duty bound, like the metaphorical chameleon, to change their colours for every patient” (Fawcett & Noble, Citation2004, p. 140). Sometimes the confessional role is given importance as well, in some healthcare settings care is provided by institutions with a confessional background. For instance, the Covenant Health, a Catholic healthcare organisation in Canada, describes its mission as follows: “We are called to continue the healing ministry of Jesus by serving with compassion, upholding the sacredness of life in all stages, and caring for the whole person—body, mind and soul” (Covenant Health, Citation2018).

In emphasising the personal and sometimes also the confessional role, the caregiver's professional role is downplayed, as conflict may arise between the former roles and the caregiver's professional role. Conflict may arise between loyalties to professional standards on the one hand and one's own spiritual beliefs on the other (Fawcett & Noble, Citation2004), or in cases when someone's professional authority is used to promote someone's personal convictions and force these onto the patient (French & Narayanasamy, Citation2011; Lyon et al., Citation2001). Authenticity and integrity on the part of the caregiver may thus compromise the professional role or the freedom and integrity of the receiver of care. Whereas some argue that too little is yet known about the implications of caregivers’ spiritual orientation for spiritual caregiving (Bjarnason, Citation2009, p. 523), others suggest that for certain caregivers, like those holding “inflexible” and “literal” positions, such conflict may become more pronounced than for others (Kevern, Citation2012, p. 986-987).

Generalist-universalists (QII): normative stance and critique

Authors in this quadrant highlight caregivers’ professional roles, and argue that this implies for all caregivers the task to provide spiritual care to all patients regardless of one's personal or confessional role. To do so, strategies and guidelines are provided for dealing with patients or clients with various spiritualities (Aten, Mangis, & Campbell, Citation2010; Keeling et al., Citation2010; Lyon et al., Citation2001), and knowledge is provided on specific religious or spiritual traditions (e.g., Islam (Miklancie, Citation2007), Catholicism (Narayan, Citation2006), or Hinduism (Hodge, Citation2004)), on spirituality in death and dying related topics (Chaplin, Citation2003; Dein, Swinton, & Abbas, Citation2013), and on prayer from diverse traditions (Dijoseph & Cavendish, Citation2005).

In focusing on the professional role, a caregiver's personal role and, though less frequently addressed in the literature, one's confessional role are contested. Many authors note difficulties when working with those who have other spiritualities than their own, e.g., when working with non-Western patients (Hodge, Citation2004, p. 27), “Christian rural religious fundamentalist” clients (Aten et al., Citation2010), or when one is religious or spiritual and the other is not (Bjarnason, Citation2009; Plante & Thoresen, Citation2012). Such difficulty may be due to a lack of knowledge, but also to questions of personal authenticity: given the “multiplicity of faith positions”, how can a therapist or pastoral counsellor be authentic without being authoritarian in the sense of directing/dictating the client's faith (Jensen, Citation2003)? Moreover, the relationship with oneself, one's own beliefs, and one's religious background is questioned, as the universal approach may become dominant over others:

… a disturbing trend has developed within the healthcare literature on spirituality. Rather than recognizing a variety of worldview approaches to spirituality, which include religious approaches, there has been a tendency to adopt a generic, universal approach that paradoxically marginalizes difference (McSherry & Cash 2004; Swinton 2006; Traphagan 2005). A significant outcome of this approach is that it allows for the uncritical adoption of particular worldviews for healthcare practice (Henery 2003). This leads us to the question of how, in a liberal society, we should be negotiating personal values and beliefs about spirituality within a discipline that has a public trust. (Pesut & Thorne, Citation2007, p. 398)

Specialist-particularists (QIII): normative stance and critique

For authors who hold both specialist and particularist views, the caregiver's or chaplain's confessional role is very important for spiritual caregiving. The caregiver in this quadrant is often presented explicitly as Protestant, Muslim, or Buddhist chaplains, and—commonly trained at theological seminaries and ordained by a religious or Humanistic institution—they associate closely with a particular tradition (Schipani, Citation2013).

However, in a society that is spiritually diverse, this confessional role is contested, both in relation to professional standards as well as in relation to religious institutions and their theological assumptions. In relation to the professional standards, the caregiver's (i.e., chaplain's) identity and performance as a “religiously authorized health worker” is questioned (Swift, Citation2013). As society becomes more secular, there is a need to “help articulate the language of spirituality” (Flatt, Citation2015, p. 45). Here lies a challenge in combining one's confessional role with one's professional role, and using language that other caregivers are able to understand: “A central challenge resides in finding relevant, current language, in reflecting meaningfully on the chaplain's evolving clinical role, and in integrating the deep intent of theological and religious traditions” (Thorstenson, Citation2012, p. 5).

In relation to religious institutions and the accompanying theological assumptions, a lack of chaplaincy models is observed that

theologically embrace different understandings of the purpose and place of God in health and healing and with which the adherents of different faiths and those of no faith at all can identify (whilst maintaining the distinctiveness and integrity of each). (Flatt, Citation2015, p. 38)

Specialist-universalists (QIV): normative stance and critique

Just as authors in QII, authors in QIV (specialist-universalist) greatly value the caregiver's professional role. As professionals, caregivers (chaplains) have to be(come) able to care for clients from a diversity of spiritualities regardless of the caregiver's personal or confessional orientation. To bolster their competences and knowledge resources have been developed for working with non-religious clients (Galashan, Citation2015, p. 117), a five steps model for “multi-spiritual/cultural competency” (Anderson, Citation2004), a “Cross-Cultural Module” for “authentic Christian hospitality” (De Neui & Penny, Citation2013), a framework for “Multicultural Competency” (Fukuyama & Sevig, Citation2004), attitudes for “cultural competency” (Grefe, Citation2011), and/or seven “multicultural-multifaith dance steps” (Flohr, Citation2009). Meanwhile, however, authors in QIV also seem to underline their personal role, as many emphasise the importance of knowing and clarifying one's own spiritual position (Anderson, Citation2004) and/or engaging in “self-awareness” or “personal awareness” (De Neui & Penny, Citation2013; Flohr, Citation2009; Fukuyama & Sevig, Citation2004; Grefe, Citation2011).

This normative stance in which the focus is on caregivers’ professional and (to a lesser extent) personal role, the caregiver's confessional role and relationship with religious institutions and their theological underpinnings is contested. Questions arise concerning the peculiarity and position of chaplains’ confessional roles:

Rather than filling their chapels, prayer, and meditation rooms with the widest possible range of religious and spiritual symbols and visibly naming religion in its multiple forms, chaplains seem to be doing the opposite. Seemingly neutral, symbol-free chapels, interfaith prayer services that one chaplain in training described as “so watered down you could find it in the phone book,” and descriptions of their work that emphasize hope and wholeness make the visible ways that religion and spirituality are present in hospitals seem almost devoid of content and conspicuously absent. (Cadge, Citation2012, p. 15)

Discussion

This study was designed to describe the different perspectives on integrating the spiritual domain in a spiritually diverse context. Our analysis suggested that two questions are central in addressing this domain: (a) Who should provide spiritual care? and (b) What is the role of caregivers’ spirituality when providing spiritual care? In response to these questions four quadrants are distinguished: generalist-particularists (QI) who see the spiritual domain as a domain to be addressed by all caregivers and in which a caregiver's own spirituality plays a vital role; generalist-universalists (QII) who opt for all caregivers to address the spiritual domain as well, yet irrespective of one's own spirituality; specialist-particularists (QIII) who argue that addressing the spiritual domain ought to be done by experts and highlight the relevance of an expert's spirituality; and specialist-universalists (QIV) who call for experts to provide spiritual care regardless of their personal spirituality. We have argued that the four positions are normative, because they give different weight to the professional, personal, and confessional roles of the spiritual caregiver. This theoretical framework aims to provide an overview of the various ways in which the spiritual domain can be integrated into healthcare. Since we have already woven theory into the previous sections, our focus in this section will be on the strengths and limitations of our approach, helping to understand its potential for future research, healthcare practices, and spiritual care policies.

Firstly, we underscore that the four quadrants represent theoretical positions whereas in reality many authors, caregivers, and organisations position themselves somewhere in between. This is important to bear in mind when healthcare professionals and policy makers seek to draw future scenarios for integrating spiritual care into healthcare. For instance, in the Dutch guidelines for spiritual care in palliative care all caregivers are (as generalists) expected to provide spiritual care at a basic level by paying attention to spiritual needs, but chaplains are (as specialists) seen as experts in the field of spiritual caregiving (Leget et al., Citation2010). A similar position is proposed in the “Generalist Specialist Model” by Balboni, Puchalski, and Peteet (Citation2014, p. 1587), in which every team member is a specialist in his/her own expertise (e.g., in spiritual care), while being a generalist in other aspects of care (e.g., in psychological or physical care). Also, the implications of QIV show that some authors seem to be on the universalist side of the continuum when arguing for general competences and strategies that prepare caregivers to address patients’ spiritual needs irrespective of their own spirituality, yet for most of these strategies awareness of the caregivers’ personal spiritual orientation still plays a vital role. Instead of being pure universalists, they thus seem to be somewhat in between the universalist and particularist position.

Secondly, the models developed in this paper may appear, at first sight, as a matrix and a triangle with equal options. However, in real life the positions in these models are normative and contested, and they contest each other. For example, when a Protestant hospital chaplain loses her Christian faith and ordination, can she still work as a chaplain in that hospital? When the hospital management takes a generalist-universalist (QII) position, and regards the chaplain as a professional who should provide spiritual care to everyone, regardless of her own spiritual orientation, the answer may be, ‘Yes, of course!’. If the hospital management takes a specialist-particularist (QIII) point of view, though, and greatly values the chaplain's confessional identity, her position is under critique. Another example may occur when a patient is about to die, asks for the sacrament of the anointing to the sick, and finds that the Roman-Catholic priest will not be there in time. Should a nurse, for instance a Muslim or a secular nurse, then administer this sacrament? Again, the answer depends on the position one takes in the quadrants. Roman-Catholics in QIII (specialist-particularists) may defend the view that the sacraments are the prerogative of their church, and consequently can only be administered by the ones appointed by the church to do so. Spiritual caregivers in QI (generalist-particularists) emphasising their personal role, by contrast, may defend the position that it depends on one's personal beliefs and values and one's authenticity as a caregiver whether such a ritual can be performed.

Obviously, this is not only a matter of normative (ideological) convictions, it is also an issue of power and vested interests. The hospital management taking a generalist-universalist (QII) position, for instance, relates to Weber (Citation1958) rational-legal style of authority, in which emphasis is placed on the caregiver's functionality, whereas the Roman-Catholics in QIII (specialist-particularists) reflect the traditional style of authority in which hierarchy plays an important role, and spiritual caregivers in QI (specialist-particularists) relate to the charismatic style of authority, emphasising caregivers’ personal characteristics. As these examples show, when these styles of authority encounter they may clash with one another, because the legitimacy of spiritual care is structured along completely different lines of rationality. While one considers functionality to be the most important criteria, someone else may find functional performance irrelevant, but ecclesial authority crucial.

Thirdly, the framework provided in this study raises questions concerning the future scenarios for each of the quadrants. Which of the quadrants will become dominant in which settings? Which has the best potential to function in a plural society, for instance with regard to practical issues such as training programmes for practitioners, or with regard to financial aspects of spiritual care provision? Future research may explore the practical implications of each of the positions more in-depth, which includes ethical considerations, such as practices of rituals and prayer. And what happens when caregivers or organisations change from one quadrant to another? In Western society, several organisations are rooted (historically) in a specific religious tradition and oftentimes have caregivers working from that spiritual orientation (as particularists) within their institution. However, in a plural society these organisations may switch to becoming a more universalist organisation, explicitly focusing on all caregivers to provide spiritual care in a universalist manner. Future studies may scrutinise these changes, describing what they entail and what consequences they have for healthcare professionals, patients, and family members.

Lastly, this study focused on implication of spiritual diversity for spiritual care. In spite of the various definitions of and approaches to spiritual care (Ganzevoort et al., Citation2014; Saad, De Medeiros, & Mosini, Citation2017), this study has not answered the question “what is spiritual care?” Rather, all forms of spiritual care by all disciplines were taken together in the analysis and many of studies focus on the perspectives of caregivers instead of care receivers. Gaining knowledge and understanding of what precisely is meant by spiritual care and what the exact requirements are when caregivers are expected to provide this type of care is part of ongoing discussions, and needs further exploration, in which patients’ and patients’ family members’ perspectives should be considered as well. Nevertheless, our study highlights that sooner or later the questions posed in this study will be part of the discussions not only among researchers on spirituality, but also between patients and their healthcare professionals, like nurses, doctors, and chaplains, and among policy makers in the field of spiritual care in healthcare. Our study may support these discussions by making a first step in categorising some central questions and answers.

Conclusion

This study shows that integrating spiritual care into healthcare in a highly pluralised, spiritually diverse context is challenging, and that there is no single way to deal with these challenges. There are different perspectives on integrating the spiritual domain into healthcare and medicine, and two questions play a central role: (a) Who should provide spiritual care? and (b) What is the role of caregivers’ spirituality when providing spiritual care? The framework provided will help scholars consider which questions to take into account when conducting research on spiritual care in healthcare settings. It will stimulate caregivers to reflect upon their own position in providing spiritual care to a diverse patient population. Furthermore, it will help policy makers to make informed decisions on how to organise and implement spiritual care provision in healthcare institutions in plural societies. In this way our analysis will contribute to an integration of spiritual care in healthcare that recognises the spiritual diversity of both patients and healthcare professionals.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Anke I. Liefbroer http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4356-3981

R. Ruard Ganzevoort http://orcid.org/0000-0003-3395-1497

References

- Note: Theoretical and conceptual literature identified via the systematic search are marked with an asterisk.

- Abu-Ras, W., & Laird, L. (2011). How Muslim and non-Muslim chaplains serve Muslim patients? Does the interfaith chaplaincy model have room for Muslims’ experiences? Journal of Religion and Health, 50(1), 46–61. doi: 10.1007/s10943-010-9357-4

- *Ai, A. L., & McCormick, T. R. (2010). Increasing diversity of Americans’ faiths alongside baby boomers’ aging: Implications for chaplain intervention in health settings. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 16(1-2), 24–41. doi: 10.1080/08854720903496126

- *Anandarajah, G. (2008). The 3 H and BMSEST models for spirituality in multicultural whole-person medicine. Annals of Family Medicine, 6(5), 448–458. doi: 10.1370/afm.864

- *Anderson, R. G. (2004). The search for spiritual/cultural competency in chaplaincy practice: Five steps that mark the path. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 13(2), 1–24. doi: 10.1300/J080v13n02_01

- *Aten, J. D., Mangis, M. W., & Campbell, C. (2010). Psychotherapy with rural religious fundamentalist clients. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 66(5), 513–523. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20677

- Bacon, D., & Borthwick, A. M. (2013). Charismatic authority in modern healthcare: The case of the “diabetes specialist podiatrist”. Sociology of Health & Illness, 35(7), 1080–1094. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12024

- Balboni, M. J., Puchalski, C. M., & Peteet, J. R. (2014). The relationship between medicine, spirituality and religion: Three models for integration. Journal of Religion and Health, 53(5), 1586–1598. doi: 10.1007/s10943-014-9901-8

- Bidwell, D. R., & Marshall, J. L. (2006). Formation: Content, context, models and practices. American Journal of Pastoral Counseling, 8(3-4), 1–7. doi: 10.1300/J062v08n03_01

- *Bjarnason, D. (2009). Nursing, religiosity, and end-of-life care: Interconnections and implications. Nursing Clinics of North America, 44(4), 517–525. doi: 10.1016/j.cnur.2009.07.010

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- *Bueckert, L. D. (2009). Stepping into the borderlands: Prayer with people of different faiths. In D. S. Schipani & L. D. Bueckert (Eds.), Interfaith spiritual care: Understandings and practices (pp. 29–49). Kitchener, ON: Pandora Press.

- Cadge, W. (2012). Paging God: Religion in the halls of medicine. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press.

- Cadge, W., & Sigalow, E. (2013). Negotiating religious differences: The strategies of interfaith chaplains in healthcare. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 52(1), 146–158. doi: 10.1111/jssr.12008

- *Chaplin, D. (2003, September 30). A bereavement care service to address multicultural user needs. Nursing Times. Retrieved from https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/public-health/a-bereavement-care-service-to-address-multicultural-user-needs/205287.article

- Chuengsatiansup, K. (2003). Spirituality and health: An initial proposal to incorporate spiritual health in health impact assessment. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 23, 3–15. doi: 10.1016/S0195-9255(02)00037-9

- Covenant Health. (2018). Mission. Retrieved from https://www.covenanthealth.ca/living-our-mission/mission

- *Cox, T. (2003). Theory and exemplars of advanced practice spiritual intervention. Complementary Therapies in Nursing and Midwifery, 9(1), 30–34. doi: 10.1016/S1353-6117(02)00103-8

- *De Neui, P. H., & Penny, D. (2013). Developing a cultural competency module to facilitate Christian hospitality and promote pastoral practices in a multifaith society. Theological Education, 47(2), 57–60. Retrieved from https://www.ats.edu/uploads/resources/publications-presentations/theological-education/2013-theological-education-v47-n2.pdf

- *Dein, S., Swinton, J., & Abbas, S. Q. (2013). Theodicy and end-of-life care. Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life & Palliative Care, 9(2-3), 191–208. doi: 10.1080/15524256.2013.794056

- *Dijoseph, J., & Cavendish, R. (2005). Expanding the dialogue on prayer relevant to holistic care. Holistic Nursing Practice, 19(4), 147–154. doi: 10.1097/00004650-200507000-00004

- Doolaard, J. (2006). Nieuw handboek geestelijke verzorging [New handbook of spiritual caregiving]. Kampen: Kok.

- Engel, G. L. (1977). The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science, 196(4286), 129–136. doi: 10.1126/science.847460

- *Fawcett, T. N., & Noble, A. (2004). The challenge of spiritual care in a multi-faith society experienced as a Christian nurse. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 13(2), 136–142. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00870.x

- *Flatt, S. (2015). Making use of models of healthcare chaplaincy. In J. H. Pye, P. H. Sedgwick, & A. Todd (Eds.), Critical care: Delivering spiritual care in healthcare contexts (pp. 37–49). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- *Fleming, D. A. (2004). Making difficult choices at the end of life: A personal challenge for all participants. Missouri Medicine, 101(6), 53–58. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15822366

- *Flohr, A. (2009). Competences for pastoral work in multicultural and multifaith societies. In D. S. Schipani & L. D. Bueckert (Eds.), Interfaith spiritual care: Understandings and practices (pp. 143–169). Kitchener, ON: Pandora Press.

- *Fraley, H., Theissen, E. J., & Jiwanlal, S. (2014). Spiritual care in a crisis: What is enough? Journal of Christian Nursing, 31(3), 161–165. doi: 10.1097/CNJ.0000000000000079

- *French, C., & Narayanasamy, A. (2011). To pray or not to pray: A question of ethics. British Journal of Nursing, 20(18), 1198–1204. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2011.20.18.1198

- *Fukuyama, M. A., & Sevig, T. D. (2004). Cultural diversity in pastoral care. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 13(2), 25–42. doi: 10.1300/J080v13n02_02

- Galashan, M. (2015). From Atheist to Zoroastrians … What are the implications for professional healthcare chaplaincy of the requirement to provide spiritual care to people of all faiths and none? In J. H. Pye, P. H. Sedgwick, & A. Todd (Eds.), Critical care: Delivering spiritual care in healthcare contexts (pp. 102–120). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Galek, K., Flannelly, K. J., Koenig, H. G., & Fogg, S. L. (2007). Referrals to chaplains: The role of religion and spirituality in healthcare settings. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 10(4), 363–377. doi: 10.1080/13674670600757064

- *Ganzevoort, R. R., Ajouaou, M., van der Braak, A., de Jongh, E., & Minnema, L. (2014). Teaching spiritual care in an interfaith context. Journal for the Academic Study of Religion, 27(2), 178–197. doi: 10.1558/jasr.v27i2.178

- Ganzevoort, R. R., & Visser, J. (2007). Zorg voor het verhaal: Achtergrond, methode en inhoud van pastorale begeleiding [To care for the story: Background, method and content of pastoral counseling]. Zoetermeer, The Netherlands: Meinema.

- *Gatrad, A. R., Sadiq, R., & Sheikh, A. (2003). Multifaith chaplaincy. Lancet, 362(9385), 748. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14219-5

- Greenhalgh, T., & Peacock, R. (2005). Effectiveness and efficiency of search methods in systematic reviews of complex evidence: Audit of primary sources. BMJ, 331, 1064–1065. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38636.593461.68

- *Grefe, D. (2011). Encounters for change: Interreligious cooperation in the care of individuals and communities. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock.

- de Groot, K. (2018). The liquidation of the church. Abingdon: Routledge.

- de Haan, S. (2017). The existential dimension in psychiatry: An enactive framework. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 20(6), 528–535. doi: 10.1080/13674676.2017.1378326

- Harding, S. R., Flannelly, K. J., Galek, K., & Tannenbaum, H. P. (2008). Spiritual care, pastoral care, and chaplains: Trends in the health care literature. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 14(2), 99–117. doi: 10.1080/08854720802129067

- Heitink, G. (2001). Biografie van de dominee [Biography of the pastor]. Baarn, The Netherlands: Ten Have.

- *Hodge, D. R. (2004). Working with Hindu clients in a spiritually sensitive manner. Social Work, 49(1), 27–38. doi: 10.1093/sw/49.1.27

- Huber, M., van Vliet, M., Giezenberg, M., Winkens, B., Heerkens, Y., Dagnelie, P. C., & Knottnerus, J. A. (2016). Towards a “patient-centred” operationalisation of the new dynamic concept of health: A mixed methods study. BMJ Open, 6(1), e010091. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010091

- *Isgandarova, N., & O’Connor, T. S. (2012). A redefinition and model of Canadian Islamic spiritual care. The Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling, 66(2), 1–8. doi: 10.1177/154230501206600207

- *Jensen, C. A. (2003). Toward pastoral counseling integration: One Bowen oriented approach. The Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling, 57(2), 117–129. doi: 10.1177/154230500305700203

- Jones, J., & Pattison, S. (2013). Editorial: Religion and health. Health Care Analysis, 21(3), 189–192. doi: 10.1007/s10728-013-0246-3

- *Keeling, M. L., Dolbin-MacNab, M. L., Ford, J., & Perkins, S. N. (2010). Partners in the spiritual dance: Learning clients’ steps while minding all our toes. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 36(2), 229–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2009.00161.x

- *Kemper, K. J., & Barnes, L. (2003). Considering culture, complementary medicine, and spirituality in pediatrics. Clinical pediatrics, 42(3), 205–208. doi: 10.1177/000992280304200303

- *Kevern, P. (2012). Who can give ‘spiritual care’? The management of spiritually sensitive interactions between nurses and patients. Journal of Nursing Management, 20(8), 981–989. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2834.2012.01428.x

- Leget, C., Staps, T., van de Geer, J., Mur-Arnoldi, C., Wulp, M., & Jochemsen, H. (2010). Richtlijn spirituele zorg [Guideline spiritual care]. Retrieved from https://www.oncoline.nl/spirituele-zorg

- *Liechty, D. (2013). Sacred content, secular context: A generative theory of religion and spirituality for social work. Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life & Palliative Care, 9(2-3), 123–143. doi: 10.1080/15524256.2013.794011

- Liefbroer, A. I., Olsman, E., Ganzevoort, R. R., & Van Etten-Jamaludin, F. S. (2017). Interfaith spiritual care: A systematic review. Journal of Religion and Health, 56(5), 1776–1793. doi: 10.1007/s10943-017-0369-1

- *Lyon, M. E., Townsend-Akpan, C., & Thompson, A. (2001). Spirituality and end-of-life care for an adolescent with AIDS. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 15(11), 555–560. doi: 10.1089/108729101753287630

- *MacLaren, J. (2004). A kaleidoscope of understandings: Spiritual nursing in a multi-faith society. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 45(5), 457–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.2929_1.x

- *Mathisen, B., Carey, L. B., Carey-Sargeant, C. L., Webb, G., Millar, C., & Krikheli, L. (2015). Religion, spirituality and speech-language pathology: A viewpoint for ensuring patient-centred holistic care. Journal of Religion and Health, 54(6), 2309–2323. doi: 10.1007/s10943-015-0001-1

- McGuire, M. B. (2008). Lived religion: Faith and practice in everyday life. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Merchant, R., & Wilson, A. (2010). Mental health chaplaincy in the NHS: Current challenges and future practice. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 13(6), 595–604. doi: 10.1080/13674676.2010.488431

- *Miklancie, M. A. (2007). Caring for patients of diverse religious traditions: Islam, a way of life for Muslims. Home Healthcare Nurse: The Journal for the Home Care and Hospice Professional, 25(6), 413–417. doi: 10.1097/01.NHH.0000277692.11916.f3

- *Monnett, M. (2005). Developing a Buddhist approach to pastoral care: A peacemaker’s view. The Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling, 59(1-2), 57–61. doi: 10.1177/154230500505900106

- *Narayan, M. C. (2006). Caring for patients of diverse religious traditions: Catholicism. Home Healthcare Nurse: The Journal for the Home Care and Hospice Professional, 24(3), 183–186. doi: 10.1097/00004045-200603000-00013

- *Nash, P. (2015). Five key values and objectives for multifaith care. In P. Nash, M. Parkes, & Z. Hussain (Eds.), Multifaith care for sick and dying children and their families: A multidisciplinary guide (pp. 15–31). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Pargament, K. I. (2007). Spiritually integrated psychotherapy: Understanding and addressing the sacred. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Pattison, S. (2013). Religion, spirituality and health care: Confusions, tensions, opportunities. Health Care Analysis, 21(3), 193–207. doi: 10.1007/s10728-013-0245-4

- *Pesut, B., & Thorne, S. (2007). From private to public: Negotiating professional and personal identities in spiritual care. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 58(4), 396–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04254.x

- *Plante, T. G., & Thoresen, C. E. (2012). Spirituality, religion, and psychological counseling. In L. J. Miller (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of psychology and spirituality (pp. 388–409). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Puchalski, C. M., Lunsford, B., Harris, M. H., & Miller, R. T. (2006). Interdisciplinary spiritual care for seriously ill and dying patients: A collaborative model. Cancer Journal, 12(5), 398–416. doi: 10.1097/00130404-200609000-00009

- Puchalski, C. M., Vitillo, R., Hull, S. K., & Reller, N. (2014). Improving the spiritual dimension of whole person care: Reaching national and international consensus. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 17(6), 642–656. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2014.9427

- Rumbold, B. D. (2012). Models of spiritual care. In M. R. Cobb, C. M. Puchalski, & B. D. Rumbold (Eds.), Oxford textbook of spirituality in healthcare (pp. 177–183). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Saad, M., De Medeiros, R., & Mosini, A. C. (2017). Are we ready for a true biopsychosocial-spiritual model? The many meanings of “spiritual”. Medicines, 4(4), 79. doi: 10.3390/medicines4040079

- *Schipani, D. S. (2009). Biblical foundations: Challenges and possibilities of interfaith caregiving. In D. S. Schipani & L. D. Bueckert (Eds.), Interfaith spiritual care: Understandings and practices (pp. 51–67). Kitchener, ON: Pandora Press.

- *Schipani, D. S. (2013). Multifaith views in spiritual care. Kitchener, ON: Pandora Press.

- Silton, N. R., Flannelly, K. J., Galek, K., & Fleenor, D. (2013). Pray tell: The who, what, why, and how of prayer across multiple faiths. Pastoral Psychology, 62(1), 41–52. doi: 10.1007/s11089-012-0481-9

- Sinclair, S., Mysak, M., & Hagen, N. A. (2009). What are the core elements of oncology spiritual care programs? Palliative and Supportive Care, 7(4), 415–422. doi: 10.1017/S1478951509990423

- Sulmasy, D. P. (2002). A biopsychosocial-spiritual model for the care of patients at the end of life. Gerontologist, 42(3), 24–33. doi: 10.1093/geront/42.suppl_3.24

- *Swift, C. (2013). A state health service and funded religious care. Health Care Analysis, 21(3), 248–258. doi: 10.1007/s10728-013-0252-5

- Swinton, J. (2010). The meanings of spirituality: A multiperspective approach to “the spiritual.” In W. McSherry & L. Ross (Eds), Spiritual assessment in healthcare practice (pp. 17–35). Keswick: M&K Publishing.

- Taylor, C. (2007). A secular age. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Thorstenson, T. A. (2012). The emergence of the new chaplaincy: Re-defining pastoral care for the postmodern age. Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling, 66(2), 1–7. doi: 10.1177/154230501206600203

- VandeCreek, L. (1999). Professional chaplaincy: An absent profession? Journal of Pastoral Care, 53(4), 417–432. doi: 10.1177/002234099905300405

- Vertovec, S. (2007). Super-diversity and its implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 30(6), 1024–1054. doi: 10.1080/01419870701599465

- Weber, M. (1958). The three types of legitimate rule. Berkeley Publications in Society and Institutions, 4(1), 1–11.

- WHO. (2002). WHO definition of palliative care. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/

- WHOQOL SRPB Group. (2006). A cross-cultural study of spirituality, religion, and personal beliefs as components of quality of life. Social Science & Medicine, 62(6), 1486–1497. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.001

- Woodhead, L., Partridge, C. H., & Kawanami, H. (2016). Religions in the modern world: Traditions and transformations. New York, NY: Routledge.