ABSTRACT

People often seek counsel from clergy before they seek help from mental health professionals. There is a need for clergy to have a way to make referrals to clinicians, and for clinicians to have a familiarity with the multiple roles of clergy and religion. Collaboration between clinicians and religious congregations provides a way to initiate and sustain continuities of mental health care. As a pilot study for a project on applying the Clergy Outreach and Professional Engagement (COPE) model in Sweden, a focus group with licenced psychologists and pastoral care givers was conducted. Transcript was analysed using inductive thematic analysis. Findings included a need for knowledge and a need for collaboration. Barriers for collaboration concerned ministers’ vow of silence and a lack of resources within primary care and psychiatry. There is a need to further discussion regarding confidentiality within the Church, and to address structural barriers within mental health care.

Introduction

Religion can be a powerful source of hope and affirmation, as well as of rejection and denigration (Beit-Hallahmi, Citation2015; Geertz, Citation1973, p. 2000; Milstein & Manierre, Citation2012; Pargament & Lomax, Citation2013). Some religious communities can increase the risk for mental and emotional distress, whereas others can be a protective foundation of support which may prevent the need for clinical care, serve as a bridge to care, and remain part of an individual’s sustained recovery (Gordon, Citation1987; Milstein, Manierre, & Yali, Citation2010; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Citation2004). People often seek counsel from clergy before seeking help from mental health professionals (Wang, Berglund, & Kessler, Citation2003) due to both a greater familiarity with clergy and because there is less stigma associated with pastoral counsel (World Health Organization, Citation2001, Citation2018). This is a concern if a person has a level of dysfunction that would best benefit from clinical assessment and mental health care. Therefore, it is necessary that clergy be able to make referrals to clinicians. In turn, clinicians need to be familiar with the multiple roles of clergy and the roles of religion in the lives of people who seek their care (Milstein et al., Citation2005; VanderWeele, Citation2017).

In contrast to psychotherapy, there is no formal limit to the number of sessions offered in pastoral care, and while psychotherapy can be expensive pastoral care is free of charge. The opportunities and outcomes of this “psychosocial intervention” by “non-specialized” professionals is an area identified by the World Health Organization (WHO) as necessary to acknowledge as well as to study (Patel et al., Citation2018, p. 1561). From a public health perspective, clinicians’ collaboration with religious congregations provides a robust way to initiate and sustain continuities of mental health care (Milstein, Manierre, Susman, & Bruce, Citation2008).

Religiousness in Sweden

Sweden is one of the most secular countries in the world (Kasselstrand, Citation2015). However, a majority of the Swedish population remain members of the Church of Sweden; in 2017, the Church of Sweden held approximately six million members. Although only 14.5% of the members regularly attended services, 42% of new-borns in Sweden are baptised, one-third of married couples are married in Church, and approximately three out of four of all deceased in Sweden are buried according to the Church of Sweden’s burial ritual (www.svenskakyrkan.se/statistik). Therefore, even in secular Sweden, with declining levels of religious beliefs and Church attendance, the Church maintains a robust role across people’s lifespans (Kasselstrand, Citation2015). One way the Church of Sweden continues to respond to Swedes’ needs is through its offer of pastoral care.

In Sweden, pastoral care is offered by both clerics and deacons in local churches as well as within institutional settings (i.e., hospital chaplaincy). There is no formal counselling education offered to pastoral caregivers in Sweden, although some educate themselves to become psychotherapists as well. A key consideration is that, in Sweden, clerics are bound by a vow of silence to keep information obtained during confession or individual pastoral care confidential. A cleric’s vow of silence is absolute; clerics cannot disclose what has been said in pastoral care regardless of the nature of information and whom it might hurt or help. Neither can the confidant absolve the cleric from the vow for any reason (Church of Sweden, Citation2010). The vow of silence puts restraints on the cleric’s ability to join collaborations, as well as to seek supervision (Rudolfsson & Tidefors, Citation2013). Deacons are also bound by a vow of silence, although not as strict. For example, a cleric’s vow of silence overrides the obligation to report knowledge of abuse even if the victim is a minor while deacons have an obligation to report such knowledge (Church of Sweden, Citation2010).

In a previous study (Rudolfsson & Tidefors, Citation2009) on clerical readiness to care for victims of sexual abuse, 23% of the responding ministers in the Church of Sweden reported that they had low levels of knowledge about authorities and organisations outside Church where they could turn to for support and help. To our knowledge, no study has investigated the level of clinicians’ knowledge about religiousness in Sweden. However, in the US, psychologists and psychiatrists have been found to be less likely than other occupational groups to regard religion as important to the individual (Shafranske, Citation2013).

The need to understand the cultural meaning of distress, as well as how cultural communities can provide a continuity of emotional support has increased greatly as Sweden has welcomed refugees. Because religious communities are key organisers of social relationships, it is necessary for mental health professionals to understand the support and social resources offered by congregations in refugee communities.

The Clergy Outreach & Professional Engagement (COPE) model

When helping persons who seek counsel, clergy and clinicians have shared work attributes. In many other ways they are different, providing opportunities for complementary collaboration. Clergy and religious communities can provide a sense of context, support, and continuity before, during, and after treatment: to both individuals and their families (Govig, Citation1999; Milstein & Ferrari, Citation2017; Shifrin, Citation1998). Unlike clinicians, clergy may know multiple generations within a single-family. They at times follow the lives of individuals from birth, to marriage, and until death. In collaboration with clinicians, the clergy’s personal familiarity and experience can be invaluable to facilitate appropriate and continuous mental health care for their parishioners by contextualising the patient’s illness and life history (Ware, Tugenberg, Dickey, & McHorney, Citation1999). Furthermore, the WHO has acknowledged that social support from one’s community can prevent more serious dysfunction that would otherwise require clinical care.

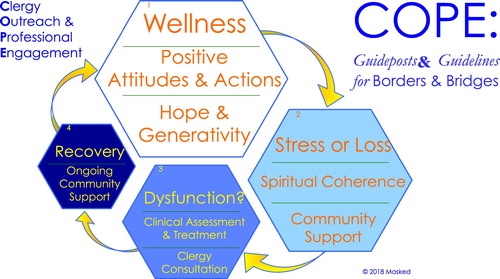

One model that demonstrates guidelines to acknowledge borders, as well as build bridges between religious communities and mental health professionals is the prevention science-based programme of Clergy Outreach & Professional Engagement (COPE; Milstein et al., Citation2010; Milstein, Middel, & Espinosa, Citation2017). COPE is derived from the National Institute of Mental Health four-part taxonomy of mental illness prevention: (1) Universal, (2) Selective, (3) Integrated, and (4) Relapse (Gordon, Citation1987; Milstein et al., Citation2008; Mrazek & Haggerty, Citation1994; National Advisory Mental Health Council Workgroup on Mental Disorders Prevention Research, Citation2001). The COPE model is an analogous four-category pathway of a cycle of care, leading from (1) Wellness to (2) Significant Stress through (3) Dysfunction to (4) Recovery and back to Wellness (). The model provides guidelines for collaboration, from clergy to clinicians, as well as from clinicians to clergy.

The COPE model acknowledges that wellness arises through community affiliation. COPE elucidates when it is recommended that clergy seek consultation from clinicians to assess if a congregant’s level of dysfunction would benefit from clinical care. COPE also describes when it is recommended that a clinician consult with clergy to engage the breadth of an individual’s social, community and spiritual support, in order to facilitate and strengthen the person’s recovery. The effectiveness of social support, treatment, and recovery also requires that the individual consumer of care be able to guide the process along the continuum (Corin & Harnois, Citation1991; Davidson, Ridgway, Wieland, & O'Connell, Citation2009).

Aim

While the COPE model has been developed and applied in the US, no form for collaboration between clergy and clinicians has been adopted in Sweden. Therefore, an interest arose to apply the COPE model in Sweden. As a pilot study for such a project, we gathered information about professionals’ views on different professions in Sweden, as well as on their views on barriers, borders and bridges to collaboration between psychologists and pastoral caregivers.

Method

A focus group with three pastoral caregivers and two licensed psychologists was conducted.

Participants

Three women and two men, from 35 to just over 60 years old, participated in the study. Two participants were working as licensed psychologists: one within an adult psychosis service and one in private practice. Two were ordained deacons and one was an ordained minister within the Church of Sweden. Participants work experience ranged from 10 to over 30 years.

Procedure

Four participants were recruited by the first author making contact through e-mail, and one participant was recruited through another participant forwarding the inquiry. The inquiry briefly described the COPE model and that the aim of the focus group was to learn more about possibilities and hindrances in adopting such a model for collaboration in Sweden. No compensation was offered for participation.

The first author moderated the focus group and the questions included how the participants went about referrals, their thoughts on their own and on the other profession, benefits and barriers of collaboration. Participants were encouraged to present new subjects for discussion and asked to describe their experiences.

The focus group lasted for two hours and was conducted at the [University of Gothenburg]. The focus group was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by the first author. A synopsis of the transcription was translated into English and sent to the second author.

Analysis

The transcript was analysed according to inductive thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). The synopsis was read by both authors separately and codes were noted, shared and discussed. The initial codes were then used in re-coding, with no attempt to fit data into pre-existing framework. Ideas that arose for a possible structure were noted. These ideas were discussed by both authors and new ideas were noted. Codes were first organised in eight different sections, e.g., the role of pastoral caregivers/psychologists, differences and bridges between professions, experiences of collaborations, actions taken instead of collaboration. The coded data extracts were reviewed to investigate whether the themes captured and fit the dataset. The codes where then re-organised under three main themes found to capture the material: a need for knowledge; the role of different professionals; barriers and benefits of collaboration. Subthemes were created to structure the material. All data extracts were reviewed to find the quotations that best captured the essence of each main- and subtheme.

Findings

The licensed psychologists (LP) talked about how faith could come into play in work with patients with trauma, obsessive-compulsive disorder, depression, and psychosis. They described how it was quite common that patients from non-Swedish cultures raised issues of faith. The pastoral caregivers (PC) described that many of the people they met had nowhere else to turn as they could neither get a public psychiatry appointment nor afford to see a private-practicing psychologist. The pastoral caregivers also described how people came to them because the pre-determined number of sessions offered in public psychiatry was not sufficient.

A need for knowledge

The participants talked about the need for knowledge within their own profession, within the other profession, and within the general population. They described what they perceived as problems within professions and specified areas of special importance.

Lack of knowledge and its consequences

The psychologists described a fear of engaging in a patient's faith, as they felt they did not have the knowledge needed and feared exacerbating their patients’ problems.

When a patient is psychotic, I think there’s a tendency to view faith-related issues as a symptom rather than as a need … there’s a fear of encouraging the patient’s psychosis if I were to engage in these issues. (LP)

It’s hard to talk about faith, as I’m afraid to make my patient feel like they aren’t met with respect. It could also become apparent how little I actually know about religiousness and that might destroy our therapeutic alliance. (LP)

Religiousness has become more prominent in Sweden today, but oftentimes the destructive aspects of religiousness is what is talked about. We seldom talk about religion as a personal thing. (PC)

Knowledge priorities

The psychologists described their need to know more about faith-related issues for proper diagnosis.

I sometimes find it hard to distinguish what is mental illness and what is culture, religion, or other things. (LP)

When you say you lack knowledge about faith-related issues, what is it you think you lack knowledge about? I think of faith as a relation [to God] and you do know relations, you can talk about that! (PC)

I know too little about what pastoral care actually is. (LP)

I do need more knowledge about for example trauma. However, as many of my confidants have no one else to turn to my work is still important and better than nothing at all. (PC)

The role of different professionals

When discussing the role of their different professions, the participants described the pastoral caregiver as engaging in their confidants’ lives more broadly. Psychologists were described as focused on treating symptoms and being more skilled at adjusting treatment to the patient’s specific needs. Borders and bridges between the professions were discussed and the participants agreed that, although the techniques differed, the goal of both pastoral care and psychotherapy is to improve their confidants/patients quality of life.

Pastoral caregivers engage in confidant’s lives; psychologists treat psychiatric symptoms

The pastoral caregivers talked about pastoral care as caring rather than curing and described the support in a religious community as potentially healing, and as a prevention intervention.

Pastoral care is a way to stay healthy, if people came to us earlier they might not end up needing specialized care. (PC)

I am good at not viewing life stories as pathological. I’m not afraid to stay in what hurts and walk with my confidants in their darkness, not rushing them. (PC)

Pastoral care givers are good at separating between spirituality, relation to God, and social religiousness. We are good at detecting if, for example, an individual has an arrested developmental image of God and in such cases address that. (PC)

We work according to manuals at a time-pressured schedule; the time to talk about existential questions just isn’t there. (LP)

I think that I could do that, but I also think that I’m not the most suited for it. Generally, I think that you [pastoral care givers] are better at that, to stay put. (LP)

I’m good at making sure that my patient gets the best treatment for their symptoms. (LP)

It is important to measure results! It’s important for the work that I do. I work strictly according to cognitive behavioral therapy, that doesn’t mean that I don’t think that other things can be helpful for my patients as well. But it’s not what I’m offering, and it’s important to make that clear to the patient. (LP)

Different techniques that share the same goals

The participants talked about psychotherapy and pastoral care as potentially complementary. One pastoral caregiver talked about how each profession was about the process of conversation, and helping their patients’/confidants’ relationships. Pastoral caregivers described confidants who were in both.

I think it has become more common for people to be in, for example, cognitive behavioral therapy and pastoral care at the same time. Many of my confidants say “I want to be in pastoral care as well, because I need to talk about my life and not just about my symptoms”. (PC)

It’s important to make clear to the patient what I can do. The bigger problem is with psychologists, and perhaps pastoral care givers, that think they can do everything themselves. Such an approach is doomed to fail. (LP)

We have the same goals, but we use different techniques. We need help to find the forms of a collaboration. (LP)

Barriers and benefits of collaboration

One pastoral giver had experienced collaboration with a local health care centre, making referrals between them. However, other participants lacked any similar experience. The participants discussed needs for collaboration, barriers to collaborations, and potential ways to bridge these barriers.

Need for collaboration

The psychologists described a need to find clearer paths to religious representatives from different communities. They talked about a need for collaboration as a way to help patients overcome stigma and to find their way back or, alternatively, to find a new religious community.

When I have felt a need to engage in collaboration, it is most commonly because a patient has been excluded from the religious community due to mental illness, and need help to get back in. (LP)

With national crises, such as the Tsunami or the fire in Backa, we have always worked together. Spirituality seems to have a more natural place with national trauma, than with personal … (LP)

I have probably handled questions of faith quite “lazy” and as secondary to the problems I address in treatment. Probably, I most commonly say “who in your social community can you talk to about this?” without engaging further. (LP)

There really is a need for collaboration, and we need more conversations about our different professions. (PC)

Barriers to collaboration and ways to overcome them

When discussing the possibilities for a collaboration, the minister’s vow of silence was discussed as a barrier. The pastoral caregivers agreed that the vow of silence had to be worked around. One suggestion was to formulate a project where the minister only acted as a pastoral caregiver, not as a cleric. If the Bishopric were to approve of such project, the vow of silence could temporarily be excused.

When I act as a contact person for that project [people who have been sexually abused within the Church] I do not have the same strict vow of silence. (PC)

Some ministers have a much stricter view than I do. There’s uncertainty about how the vow of silence should be practiced. I think that some pastoral care givers “hide” behind their vow, and there’s a lack of discussion about it in Church. (PC)

In theory, it should be easy to refer clients from pastoral care to us and vice versa, but I think we’ll need to get to know each other to make it happen. (LP)

They referred at least one patient a week to me, not because of the patient’s need for pastoral care, but because their psychologist was on long-term sick leave. (PC)

If a collaboration between the health care system and the Church is to work we need to find a way to get more psychologists in primary care to begin with. (LP)

It has felt really good to meet with you, and to have had such good conversation. It fills me with hope for the future; I feel strengthened in my own profession, and I’m glad that the psychologists have theirs. (PC)

All participants stressed the potential benefits of collaboration to be able to offer the best care possible to the people who sought their help. One psychologist said that, in the future, she will ask more:

I think I will be more courageous in asking about faith. I will try to trust in that I’m good at meeting people, and I will have faith that I can meet the spiritual dimensions of my patients as well. (LP)

Discussion

This was a productive conversation. The participants demonstrated an awareness of borders between their professions, as well as how they could interact to benefit persons seeking care. New insights concern the need to address structural barriers amid government bureaucracies of mental health care.

Insight within each profession, concerns and hopes across professions

Members of each profession described the differences between their professions and their satisfaction with these differences. Clinicians spoke of the time and technique limitations of their profession as strengths. They were trained to deliver manualised treatments within time constraints that limited talk about “life in general”. They focused on identifying problems and working toward measurable interventions for measurable results. The clergy emphasised the more open-ended nature of their work. They spoke of listening to stories and accompanying the people who seek their counsel. Along with their comfort within the borders of their professions, clergy and clinicians acknowledged that the other profession had insight and expertise that would be helpful to their work.

Acknowledging their differences also led participants to describe how they would like to expand the content from the other profession, as well as have more interaction. Clergy and clinicians acknowledged how individuals who sought help saw the two areas as separate, yet complementary. They acknowledged the need to share their expertise, which could come in the form of education, dialogue and collaboration.

Psychologists acknowledged their insufficient knowledge about religion. They did not feel equipped to differentiate religion as resource from religion as a risk factor. This paradoxically led clinicians to ask patients less about religion, sometimes being afraid to enhance their patients’ problems if they were to address faith. A similar feature was the fear that they might say the wrong thing, harming the therapeutic alliance. Clergy pointed out how the key to understanding people is through inquiry about their relationships. A bridge they offered was for clinicians to ask people about their relationship with God. As with any relationship that is the focus of psychotherapy, there could be positive and negative attributes that then become the focus of therapy (Abu-Raiya, Pargament, & Krause, Citation2016). A developmental approach could encourage the possibilities for collaboration between the two professions on the nuances of religious themes (Fowler, Citation1981).

Clergy spoke of their need to understand the psychological effects of trauma. Along with co-professional conversation, they might try to work collaboratively with persons who want/need both pastoral care and psychotherapy. This is in line with the wishes of confidants (Rudolfsson & Tidefors, Citation2015).

The vow of silence and public resource impediments

The issue of confidentiality for clergy is paramount. Bergstrand (Citation2005) has previously discussed that the vow of silence needs to be adjusted so that clergy can seek supervision and are able to collaborate with other professionals. The ability for clergy to seek counsel is important to assure that the person seeking help receives optimum care (Rudolfsson & Tidefors, Citation2013, Citation2015). In recent years, there has been a growing awareness of the harmful effects on professionals working with traumatised individuals, and the risk for professionals to develop similar trauma symptoms. Lack of supervision is a significant risk factor (Hendron, Irving, & Taylor, Citation2012) for this secondary traumatisation (Pearlman & Saakvitne, Citation1995). This is a discussion that needs to be pursued more within the Church of Sweden. We suggest that the Church acknowledge the trauma to ministers who are not able to communicate with clinicians who could help persons who come to clergy for counsel.

A second significant barrier concerned the effects of the under-resourced public health service. One profound example involved a local health care centre that tried to use local to provide care, to make up for a lack of psychologists. Rather than as collaborators, the clergy was seen as free care providers. This disregard reinforces tensions within the Church over collaboration with health services. When persons complete their limited number of pre-determined open-psychiatric sessions, they also turn to clergy (Rudolfsson & Tidefors, Citation2015). Immigrants and refugees for whom religion is an important source of support might suffer more than necessary, when their only access to counsel is from their clergy.

The Church can be a collaborator; it cannot be a substitute. There is a need for more resources in primary care and psychiatry so that there would be time to both inquire about a patient’s community resources and for clinics to build relationships with churches and mosques and temples. For religious leaders, to know the resources offered by their local clinics, would encourage increased resources for collaboration. This could become an alliance to increase and influence the distribution of public resources, which is an exemplary model to promote mental health via the WHO Sustainable Development Goals for mental health.

Limitations

Previous studies have found that focus group participants, to some degree, say what they think the researcher wants to hear (Randall, Prior, & Skarborn, Citation2006). Therefore, it is important to note the possibility that as the first author, who moderated the focus group, is coming from the psychological field it could have affected what the participants chose to tell, or at least the interpretations of what was told may have been affected by the authors’ backgrounds.

This was a pilot study. The small number of participants gave insight, which may not be generalisable to other clergy and clinicians. Furthermore, the participants were self-selected, indicating that they may have a greater interest in interactions between clergy and clinicians and that they may have thought more about the benefits and challenges of collaboration than other members of their profession.

Conclusions and future recommendations

The WHO has noted that mental health burdens are increasing in all countries (World Health Organization, Citation2018). Therefore, the United Nations has included mental health as a necessary Sustainable Development Goal, which is responsive to social determinants (Lund et al., Citation2018). There is a need to change from a model establishing illness to models encouraging wellness, and a need to engage both professional caregivers as well as non-specialists like clergy (Patel et al., Citation2018; VanderWeele, Citation2017).

Our informants described multiple scenarios wherein clergy could expand access to mental health care through collaboration with clinicians, who in turn could improve continuity and recovery through referral and collaboration with clergy. The COPE model could be one way to further such collaboration in Sweden.

Acknowledgement

We wish to offer our warmest thanks to the participants for sharing their thoughts and experiences in an open-minded way.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Abu-Raiya, H., Pargament, K. I., & Krause, N. (2016). Religion as problem, religion as solution: Religious buffers of the links between religious/spiritual struggles and well-being/mental health. Quality of Life Research, 25(5), 1265–1274. doi: 10.1007/s11136-015-1163-8

- Beit-Hallahmi, B. (2015). Psychological perspectives on religion and religiosity. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Bergstrand, G. (2005). Bikt, enskild själavård, tystnadsplikt-vad menar vi egentligen? [Confession, individual pastoral care, vow of silence. What do we really mean?]. Stockholm: Verbum.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Church of Sweden. (2010). Ett skyddat rum: Tystnadsplikt i Svenska kyrkan [A protected room: The vow of silence in the Church of Sweden.] (Vol. 3). Stockholm: Ineko.

- Corin, E., & Harnois, G. (1991). Problems of continuity and the link between cure, care, and social support of mental-patients. International Journal of Mental Health, 20(3), 13–22. doi: 10.1080/00207411.1991.11449202

- Davidson, L., Ridgway, P., Wieland, M., & O'Connell, M. (2009). A capabilities approach to mental health transformation: A conceptual framework for the recovery era. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 28(2), 35–46. doi: 10.7870/cjcmh-2009-0021

- Fowler, J. W. (1981). Stages of faith: The psychology of human development and the quest for meaning. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

- Geertz, C. (1973). Religion as a cultural system. In C. Geertz (Ed.), The interpretation of cultures: Selected essays (pp. 87–125). New York, NY: Basic Books.

- Gordon, R. (1987). An operational classification of disease prevention. In J. A. Steinberg & M. M. Silverman (Eds.), Preventing mental disorders: A research perspective (pp. 20–26). Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health.

- Govig, S. D. (1999). In the shadow of our steeples: Pastoral presence for families coping with mental illness. New York, NY: Haworth Pastoral Press.

- Hendron, J. A., Irving, P., & Taylor, B. (2012). The unseen cost: A discussion of the secondary traumatization experience of the clergy. Pastoral Psychology, 61(2), 221–231. doi: 10.1007/s11089-011-0378-z

- Kasselstrand, I. (2015). Nonbelievers in the Church: A study of cultural religion in Sweden. Sociology of Religion, 76(3), 275–294. doi: 10.1093/socrel/srv026

- Lund, C., Brooke-Sumner, C., Baingana, F., Baron, E. C., Breuer, E., Chandra, P., … Saxena, S. (2018). Social determinants of mental disorders and the sustainable development goals: A systematic review of reviews. Lancet Psychiatry, 5(4), 357–369. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30060-9

- Milstein, G., & Ferrari, J. (2017). Religion, cultural competence, and community service: Promoting wellness – responding to stress – facilitating sustained recovery. In A. Hoffman (Ed.), Creating a transformational community: The fundamentals of stewardship activities (pp. 105–128). Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Milstein, G., Kennedy, G. J., Bruce, M. L., Flannelly, K., Chelchowski, N., & Bone, L. (2005). The clergy's role in reducing stigma: A bi-lingual study of elder patients’ views. World Psychiatry, 4(S1), 28–34. Retrieved from https://www.ccny.cuny.edu/sites/default/files/profiles/upload/Elder-Stigma-86-Moved.pdf

- Milstein, G., & Manierre, A. (2012). Culture ontogeny: Lifespan development of religion and the ethics of spiritual counselling. Counselling and Spirituality, 31(1), 9–30. Retrieved from https://academicworks.cuny.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1343&context=cc_pubs

- Milstein, G., Manierre, A., Susman, V., & Bruce, M. L. (2008). Implementation of a program to improve the continuity of mental health care through Clergy Outreach and Professional Engagement (COPE). Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 39(2), 218–228. doi: 10.1037/0735-7028.39.2.218

- Milstein, G., Manierre, A., & Yali, A. M. (2010). Psychological care for persons of diverse religions: A collaborative continuum. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 41(5), 371–381. doi: 10.1037/a0021074

- Milstein, G., Middel, D., & Espinosa, A. (2017). Consumers, clergy, and clinicians in collaboration: Ongoing implementation and evaluation of a mental wellness program. American Journal of Psychiatric Rehabilitation, 20(1), 34–61. doi: 10.1080/15487768.2016.1267052

- Mrazek, P. B., & Haggerty, R. J. (Eds.). (1994). Reducing risks for mental disorders: Frontiers for preventive intervention research. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- National Advisory Mental Health Council Workgroup on Mental Disorders Prevention Research. (2001). Priorities for prevention research at NIMH. Prevention & Treatment, 4(1), Article ID 19c. doi: 10.1037/1522-3736.4.1.419c

- Pargament, K. I., & Lomax, J. W. (2013). Understanding and addressing religion among people with mental illness. World Psychiatry, 12(1), 26–32. doi: 10.1002/wps.20005

- Patel, V., Saxena, S., Lund, C., Thornicroft, G., Baingana, F., Bolton, P., … UnÜtzer, J. (2018). The Lancet Commission on global mental health and sustainable development. The Lancet, 392(10157), 1553–1598. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31612-X

- Pearlman, L. A., & Saakvitne, K. W. (1995). Trauma and the therapist: Countertransference and vicarious traumatization in psychotherapy with incest survivors. New York, NY: WW Norton & Co.

- Randall, W. L., Prior, S. M., & Skarborn, M. (2006). How listeners shape what tellers tell: Patterns of interaction in lifestory interviews and their impact on reminiscence by elderly interviewees. Journal of Aging Studies, 20(4), 381–396. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2005.11.005

- Rudolfsson, L., & Tidefors, I. (2009). “Shepherd my sheep”: Clerical readiness to meet psychological and existential needs from victims of sexual abuse. Pastoral Psychology, 58(1), 79–92. doi: 10.1007/s11089-008-0173-7

- Rudolfsson, L., & Tidefors, I. (2013). I stay and I follow: Clerical reflections on pastoral care for victims of sexual abuse. Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling, 67(2), 1–14. doi: 10.1177/154230501306700205

- Rudolfsson, L., & Tidefors, I. (2015). The struggles of victims of sexual abuse who seek pastoral care. Pastoral Psychology, 64(4), 453–467. doi: 10.1007/s11089-014-0638-9

- Shafranske, E. P., & Cummings, J. P. (2013). Religious and spiritual beliefs, affiliations, and practices of psychologists. In K. I. Pargament, A. Mahoney, & E. P. Shafranske (Eds.), APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality: An applied psychology of religion and spirituality (Vol. 2, pp. 23–41). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Shifrin, J. (1998). The faith community as a support for people with mental illness. New Directions for Mental Health Services, 1998(80), 69–80. doi: 10.1002/yd.23319988009

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2004). Building bridges: Mental health consumers and members of faith-based and community organizations in dialogue. Rockville, MD: United States’ Department of Health and Human Services.

- VanderWeele, T. J. (2017). On the promotion of human flourishing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(31), 8148–8156. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1702996114

- Wang, P. S., Berglund, P. A., & Kessler, R. C. (2003). Patterns and correlates of contacting clergy for mental disorders in the United States. Health Services Research, 38(2), 647–673. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00138

- Ware, N. C., Tugenberg, T., Dickey, B., & McHorney, C. A. (1999). An ethnographic study of the meaning of continuity of care in mental health services. Psychiatric Services, 50(3), 395–400. doi: 10.1176/ps.50.3.395

- World Health Organization. (2001). The world health report 2001, mental mealth: New understanding, new hope. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. (2018). Mental health atlas 2017 (Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO). Geneva: World Health Organization.