ABSTRACT

The association between religion or spirituality and psychological concepts (e.g., subjective well-being), have received frequent support, however, recent evidence has noted that cultural factors may affect this relationship. The consideration of these concepts for sexual orientation minorities has been neglected in previous years and now a body of evidence is beginning to develop around concerns for this population, with some speculation for the changes of ‘stressors' for future generations and the implication on mental health outcomes. Lesbian and Gay individuals of faith (or spirituality), are susceptible to unique ‘stressors’, whilst others suggest religion can provide a support network providing protective health benefits. This review explores the evidence for psychological measures associated with LGB people of faith. The evidence suggests following a religion or faith can provide good social support, reducing health risks, however, can have negative implications for mental and physical health such as, internalised homophobia, anxiety and rejection.

KEYWORDS:

LGB population and psychological health

Sexual Orientation Minority Groups (SOMG), and in particular gay men, have higher rates of mental health issues, likely mediated by victimisation experiences (Marwa & Davis, Citation2017). Other factors include demographic differences, intersections of identities, psychological health (mental health and well-being), and specific relational factors unique to SOMG (Foster et al., Citation2017; Herek et al., Citation2010; Meyer & Northridge, Citation2007; Zinnbauer et al., Citation1997). However, few studies capture the psychological consequences for SOMG of faith or religious affiliation. The psychological health for transgender individuals of religion or faith is even less known (Schrock et al., Citation2014; Sumerau et al., Citation2017; Sumerau et al., Citation2018).

Religion and spirituality

Definitions of religion, religiosity and spirituality as concepts and constructs have been widely debated (McAndrew & Voas, Citation2011) with implications for research (e.g., measuring participants religiosity and comparing factors across groups), especially when exploring SOMG psychological and mental health (Wilkinson & Johnson, Citation2020). Religion is highly complex and multidimensional in construct (McAndrew & Voas, Citation2011). Religion usually incorporates aspects of common and shared belief, practice, rituals amongst a community of individuals and is rooted in a tradition (Koenig, Citation2009; Pargament & Raiya, Citation2007). Therefore, it is cultural, organisational, personal, and behavioural (McAndrew & Voas, Citation2011). Spirituality is free of religiosity (de Jager Meezenbroek et al., Citation2012) and more challenging to define but usually involves discovering the meaning of life events (de Jager Meezenbroek et al., Citation2012; Sink, Citation2004).

In the west, religious affiliation in terms of identifying, affiliating, practicing and committing varies significantly (McAndrew & Voas, Citation2011). Consequently, research usually considers religion and spirituality side by side; therefore, this review will be inclusive of “measures” of both. That said, measuring poorly defined concepts with varied engagement, and crude responses, can lead to significant issues with the data (Cohen et al., Citation2017). There are no clear standards to guide the quantifiable measure of religiosity, however, aspects of belief, practice, formal membership, informal affiliation, ritual initiation, doctrinal knowledge, moral sense, and core values have previously been related to measures of religiosity (McAndrew & Voas, Citation2011).

Religion and psychological health (general population)

Some individuals turn to “religion” as a supportive coping tool when they are experiencing major social or life events (Koenig, Citation2009). Religion and religious beliefs are thought to provide a sense of meaning and purpose, fostering optimism and hope as well as supportive role models, aid individual’s conceptualisations of control and reduce their sense of isolation and loneliness (Koenig, Citation2009). Spirituality, on the other hand, has been tentatively associated with an individual’s sense of well-being (de Jager Meezenbroek et al., Citation2012). “Religious coping” has been observed across diverse religions (Abu-Raiya & Pargament, Citation2015) with commonality and divergences.

In heterosexual samples, religion has been consistently associated with mental and physical health benefits (Foster et al., Citation2017; Galen, Citation2009; Hackney & Sanders, Citation2003; Koenig et al., Citation2012; Lun & Bond, Citation2013). For Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual (LGB) individuals, there appear limited benefits (Cranney, Citation2017) and heightened risk of negative physical and mental health associated with religious coping (Brewster et al., Citation2016; Kim et al., Citation2015; Longo et al., Citation2013).

The associations between religion and challenging psychological constructs, such as suicidal ideation and behaviours, is mixed and complex due to the multifaceted nature of both religion and suicide (Lawrence et al., Citation2016). Religious beliefs and or spirituality potentially act as a “protective factor” providing psychological and social resources in the form of support communities (Weber & Pargament, Citation2014) when coping with stress and anxiety (Koenig, Citation2009) or depression (Koenig et al., Citation2001; Smith et al., Citation2003) or suicidal thoughts and behaviour (Wang et al., Citation2016). Religious beliefs and practices assist some individuals to cope with stressful life events and gain peace of mind and purpose in life (AbdAleati et al., Citation2016). Religious affiliation may not directly protect against suicidal ideation but may protect against suicide attempts, however, this is dependent on the culture-specific implications of affiliating with a particular religion (Lawrence et al., Citation2016).

Religion or spirituality can be a protective resource for healthy people to reduce the risk of death; depression; issues associated with disability and general “well-being” (Powell et al., Citation2003; Ryff & Singer, Citation2008), however, the protective nature is debated (Meltzer et al., Citation2011).

Religion and psychological health (LGBT population)

Given the increased risk of psychological health concerns in LGB individuals, it is important to consider the role of religion and spirituality for this population. The social, emotional and psychological needs are of particular importance for LGB individuals of faith, given the unique stressors (e.g., “coming out” process) for this population (Page et al., Citation2013). Internalised homophobia is one example of a specific issue for LGB communities, which impinges on mental health and well-being (Berg et al., Citation2015; Igartua et al., Citation2009). Positive religious coping was found to moderate the relationship between internalised heterosexism and psychological well-being (Brewster et al., Citation2016).

Some religions appear to be associated with less desirable outcomes (Abu-Raiya & Pargament, Citation2015), for example, sexual orientation minority youth have reported feelings of rejection from religious groups as a consequence of their sexual orientation (Page et al., Citation2013; Hamblin & Gross, Citation2013). There are some generational differences evident in the Internet Generation (IGen) – also known as generation Z or the internet generation (Twenge, Citation2017), which include a greater acceptance of differences between individuals. For example, sexual orientation differences between peers are accepted in iGen and seemingly individuals are managing environmental stressors associated with LGB much better during their early years (Meyer, Citation2016). It is, however, hypothesised that they will be more susceptible to risk factors later in life (Meyer, Citation2016) as a consequence of reduced resilience development during adolescence (Twenge, Citation2017). IGen are also less interested in religion (Twenge, Citation2017). The emerging body of work exploring internal and external factors that support resilience development in young people (Longo et al., Citation2013), namely, supportive family members and a strong healthy friendship network (Doty et al., Citation2010), the presence of gay-straight alliances in schools, and the presence of safe, non-judgemental adults with whom they can talk about their sexuality orientation and gender identity (Walls et al., Citation2010).

For previous generations, individuals were at risk of “gay-related stress”, which includes stressors associated with negative family and friend reactions, alongside consequential victimisation experiences (Page et al., Citation2013). There is some evidence to suggest that LGB individuals, who mature in a religious context are at an increased risk of experiencing internalised homophobia and consequently increased suicidal thoughts and behaviours (Gibbs & Goldback, Citation2015). Lesbian and Gay Christians integration of sexuality and faith can lead to resilience-building in individuals, through transformation of theological meaning, when an individual finds a “safe” and “affirming” congregation (Foster et al., Citation2015).

Whilst the terms sexual orientation, sexual identity and sexuality are often used interchangeably, these terms can be used to refer to specific dimensions of an individual’s sexuality (Geary et al., Citation2018). The three-dimensional theory of sexuality proposes that sexuality is made up of sexual attraction (or interest), sexual behaviour and sexual identity. Sexual identity captures how the individual defines themselves; sexual interest/attraction captures what the individuals want to do regardless of whether they do it; and sexual behaviour as what individuals do regardless of their sexual interest or sexual identity (Moser, Citation2016). The term sexual orientation is therefore used to describes a distinct type of intense sexual interest (Moser, Citation2016).

This review focuses specifically on the studies that captured psychological health measures for individuals who identify as sexual orientation minorities and of faith/spirituality. It does not include research that has captured the process of, or theorised about, “identity” formation, as this literature base assumes a level of well-being and mental health. Also, the current climate around conversion therapy and religion contributes to the rationale that it is timely to review the current literature on this topic specifically focussing on well-being and mental health consequences of religion/religious belief in sexual minority groups. In addition, this review focusses on the quantitative studies of the given topic area; the qualitative studies have been reviewed separately in a related paper. This decision was based on the type of data collected from these differing methodological approaches. The quantitative studies have captured, mainly, self-reported but direct measures of psychological components and religious affiliation or spirituality. The qualitative studies have captured individual’s reflections and experience of negotiating their religious or spiritual identity as a sexual minority.

Research question:

What evidence is there for psychological health consequences for sexual orientation minorities of faith or religious affiliation?

Method

The research team agreed on a protocol informed and based on the updated PRISMA-P () checklist for the reporting of systematic reviews (Shamseer et al., Citation2015), following extensive discussion regarding appropriate search terms and relevant databases. Three databases were searched: PubMed, Scorpus and PsychINFO during November 2018 using a combination of search terms (). Research articles published in the peer-reviewed literature, as well as on-going and in press studies were included – theses, case studies and editorials were excluded, along with position articles and literature reviews. The intervention (or phenomena of interest) was all religions, religious beliefs and spiritualties specifically in relation to studies that captured sexuality or sexual orientation of their recruited population, alongside measures of psychological health. It was necessary for publications to be in English.

Table 1. Table of search terms.

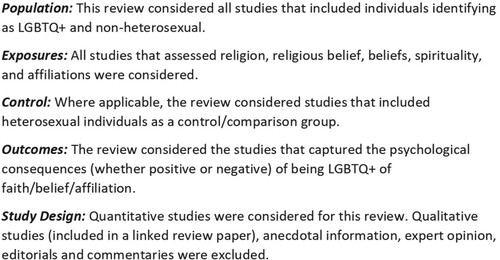

To attain specificity, the PECOS framework (NICE, Citation2014) as used by Marwa and Davis (Citation2017) was adopted as outlined in .

The research team discussed and agreed on the criteria by which papers were appraised for inclusion and exclusion. This criterion ensured that the review remained focussed on the research question and that the included studies had the required measures and focus.

Eligibility criteria and study selection

The remaining papers were considered against the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Exclude papers that capture/measure opinion of / attitudes towards sexual minorities of faith – as this review is only interested in sexual minorities’ personal experiences.

Exclude papers that focus on identity formation (the focus of this paper is on psychological health rather than identity formation and processes).

Exclude clergy / religious leader samples – as they are a different group of individuals with differing issues and experiences.

Exclude literature reviews.

Exclude opinion papers/ position papers.

Exclude qualitative studies (appears in separate review as they contribute to a different research question).

Exclude papers not in English.

Exclude papers that cover sexual orientation change efforts unless focus on religion and reports a direct measure of psychological health/well-being.

Include only papers with at least one measure of a psychological construct of well-being or psychological health AND religious/spirituality with LGBTQ+ populations.

Quality assessment and data extraction

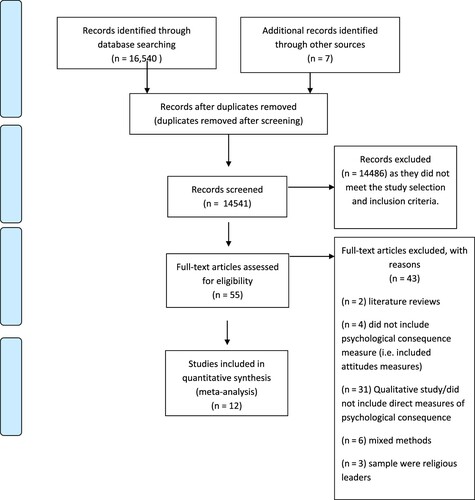

The appraisal of studies was organised in four distinct stages: (1) records identification; (2) records title screening; (3) records abstract screening; (4) full-text assessment and final decision for inclusion. Seven duplicate papers were automatically removed at the identification stage. Following title and abstract screening, 55 papers remained for full-text screening, of which, 12 were retained for the analysis of this review (see for full breakdown). A quality assessment tool AXIS (Downes et al., Citation2016) was used to screen papers for quality rating based on their methodological rigour and data relevance. The AXIS consists of 20 items and can be used to assess quantitative method research papers. The quality assessments were conducted by two reviewers and decisions made through discussion, involving a third reviewer as necessary.

Data analysis and synthesis

The papers were analysed and synthesised drawing on an approach in keeping with that proposed by Whittemore and Knafl (Citation2005) of data reduction, data display, data comparison, and verification of conclusions. This approach was deemed most appropriate given the ethos of a review method that is inclusive of combining diverse methodologies (e.g., experimental and survey research with quantitative data that was not deemed appropriate to statistically compare). The studies included in this full review utilised a range of differing tools or questions to capture individual’s “religion”, “religiosity”, or “spirituality”, along with a range of mental health measures, therefore, it was not possible to conduct a statistical meta-analysis of collective results as these would be non-comparable. The procedure that was adopted allowed for the process of identifying patterns, which were then grouped together to form the overarching categories.

Results

A total of 14,541 records were found after duplicates were removed. Of these, 14,486 were removed by title and abstract based on the exclusion and inclusion criteria. The main reason for exclusion at that point was due to the focus on identity formation without consideration for psychological health, mental health, and well-being. Fifty-five full-text papers were retained for consideration, after full-text screening, a further two were removed due to being literature reviews, four did not include psychological consequence measure (i.e., included attitudes measures), 31 were qualitative study designs, six were mixed methods and three recruited religious leaders as their participants. Therefore, a total of 12 studies were included in this analysis. gives a description of the citations, participants, method, measures, findings, and further notes.

Table 2. Details and descriptions of included studies.

displays the key characteristics of the included studies in this review by topics, themes, issues, characteristics, and sample. Only four of the papers in this review included a sample of transgender individuals, of these four papers, the transgender representation was small. Therefore, the findings of this review focus on the categories of Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual (see ).

Table 3. Key demographics and characteristics of the included papers in this review.

A total of nine out of 12 studies reported statistically significant results that support a negative psychological health association for non-heterosexual individuals who are of a belief / faith or affiliation. These ranged from general anxiety (generalised anxiety disorder (GAD)) to depression and increased suicidal ideation. In three of the studies, a positive or protective outcome was reported for non-heterosexual individuals of faith/belief or affiliation. These are related to level of well-being and protection that come from positive social support found in some affirming congregations. One study noted the risk and protective nature that religion played for non-heterosexual individuals in relation to self-harm.

Few studies have captured relevant and specific data to inform our understanding about the LGB population’s abandonment of childhood religions or faiths. This is important as the data capturing individuals who remain religious or spiritual may not be representative of the LGB population and consequently the positive or negative role that may play might not generalise to the entire LGB population. Gibbs and Goldback’s (Citation2015) study, included in this review, captured relevant data to inform part of this issue. From a survey sample of 5281 U.S. residents, they analysed and report on a subsample of 2,949 (individuals aged between 18 and 24 years), of which 347 identified as heterosexual, questioning or other and 2602 identified as gay/lesbian or bisexual. Forty percent reported religious upbringing with no conflict, 31% reported resolving the conflict and 12% reported unresolved conflict. Of those that reported a conflict between religion and sexuality, 42% left their religious affiliation.

Religious affiliation and psychological health

All of the studies included in this review supported that an affiliation with a religious group had a significant impact on non-heterosexual’s psychological health. More specifically, who or where an individual had a religious affiliation, related to levels of well-being or happiness (Barringer & Gay, Citation2017). For example, Catholics, Agnostic and Atheists had lower levels of happiness compared to Protestants (Barringer & Gay, Citation2017). Surprisingly, Barringer and Gay (Citation2017) found no difference between mainline Protestants (whose church doctrine often accept same-sex relations) and evangelical Protestants (whose church doctrine often condemns same-sex relations). Mormon LGB reported better mental health than non-Mormon LGB’s; however, they also reported lower physical health (Cranney, Citation2017). Foster et al. (Citation2017) was the first study to compare experiences of LGB individuals by their systems of belief or non-belief. Despite perceived importance of personal system of belief for heterosexuals, according to Foster et al. (Citation2017), Religious/ Spiritual /Agnostic LGB do not differ dramatically in levels of mental health or how they navigate personal relationships suggesting belief/non-belief functions differently for LGB individuals. The individual methodologies used in the included papers prevented direct comparisons of the data.

Frequency of contact with religious group

Five studies reported data supporting that frequent attendance to meetings or services of a religious group significantly related to increased happiness in heterosexuals, however, the same was not found for non-heterosexuals (Barringer & Gay, Citation2017) suggesting that frequency of attendance for non-heterosexuals does not increase happiness. Specifically, church attendance has been associated with “psychological adjustment”, with multiple contextual factors playing a role in the direction of the relationship (Hamblin & Gross, Citation2013). In some cases, religious communities can serve as a source of support, engaging in religious practices may provide comfort and peace, especially in times of stress (Koenig, Citation2009). In contrast, based on the theological underpinning that homosexuality is “sinful” or “immoral”, gay and lesbian individuals can experience exclusion and therefore, equally, attending church can promote stress and tension for Gay and Lesbian (as well other non-heterosexual) individuals (Hamblin & Gross, Citation2013).

Religion and internalised homophobia

Four out of 12 of the studies suggested that LGBTQ+ individual’s experience of heterosexism, discrimination and internalised heterosexism correlated positively with psychological distress and negatively with well-being (Brewster et al., Citation2016). Some studies have reported that a great proportion of sexual minority youth perceived experiencing interpersonal discrimination (Gattis et al., Citation2014), while heterosexual youth reported being affiliated with a denomination that either endorsed same-sex marriage or oppose same-sex marriage, whereas sexual minorities identified as secular (Gattis et al., Citation2014). Gibbs and Goldback (Citation2015) found that internalised homophobia fully mediated one conflict indicator, “report of conflict”, and partially mediates the other two indicators (“anti-homosexual parental religious beliefs” and “left religion of origin due to conflict”) relationship with the outcome of suicidal thoughts. Internalised homophobia also fully mediates the relationship of one conflict indicator, “Anti-homosexual parental religious belief”, with the outcome of chronic suicidal thoughts (Gibbs & Goldback, Citation2015).

Religion and coping

Individuals appear to use negative and positive religious coping strategies to overcome the stress experienced by conflict between religious and sexual identities (Kralovec et al., Citation2014; Shilo et al., Citation2016). Negative religious coping has been strongly, positively, related to psychological distress (Brewster et al., Citation2016; Kralovec et al., Citation2014; Shilo et al., Citation2016) and negatively with well-being, but positive religious coping was unrelated to the indicators of mental health (Brewster et al., Citation2016).

Positive religious coping moderated the internal relation of heterosexism and psychological well-being (Brewster et al., Citation2016), in the presence of social resources (social connections with the LGBT community and the acceptance of sexual orientation by friends), positive religious coping result in better mental health outcomes (Shilo et al., Citation2016), highlighting the importance of resilience in the lives of religious gay and bisexuals (Shilo et al., Citation2016).

Mental health measures

Several mental health concerns have been highlighted, with empirical supporting evidence, for individuals of LGBTQ+ and of faith / religion or belief across all papers included in this review. For example, in one study depression was statistically significantly greater in sexual minorities compared to heterosexuals (Gattis et al., Citation2014) particularly for young people. Sexual minority youth reported perceiving interpersonal discrimination, which was significantly and positively associated with depression scores. Religious affiliation, belonging to a religious group that opposing same-sex marriage vs. endorsing same-sex marriage, was positively associated with depression scores. Religiosity was significantly and negatively associated with depression scores (Gattis et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, LGBT young adults who mature in religious contexts have a greater chance of experiencing suicidal thoughts and more specifically chronic suicidal thoughts, as well as suicide attempts when compared to other LGBT young adults (Gibbs & Goldback, Citation2015) suggesting that religious affiliation mediates. Also, there appears to be an increased risk of self-harming behaviours among sexual minority youth (Longo et al., Citation2013) which increases in youth who follow a faith with high levels of religious guidance. Interestingly, in an Austrian study, religion was associated with higher scores of internalised homophobia, but fewer suicide attempts in the LGB population (Kralovec et al., Citation2014).

Alongside the heightened risk of suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts, participants who identified with “rejecting” faith communities showed greater GAD symptoms with more frequent attendance (Hamblin & Gross, Citation2013) and no relationship was found between attendance and GAD among those of accepting communities (Hamblin & Gross, Citation2013). There was no relationship between frequency of attendance and levels of depression (Hamblin & Gross, Citation2013).

Heterosexual, Orthodox Jews experience increased life satisfaction with religiosity and lower negative affect. Whereas Gay Orthodox Jews spirituality was positive related with well-being and specifically increased life satisfaction and positive affect. Intrinsic religiosity, representing engagement with religion not for personal motivation, was associated with some positive mental health outcomes. Extrinsic personal religiosity was associated with negative mental health outcomes, including somatisation, psychoticism and phobic anxiety (Harari et al., Citation2014).

Discussion

The papers included in this review highlight the issues relating to psychological health, mental health and well-being for LGBT+ of faith or religion. Some of these concerns are more serious and pose greater risk for individual’s overall health and development, particularly “acceptance” of their sexual orientation by their peers along with altered self-concept and internalised homophobia. For some, religious groups social support network appears to protective for secondary psychological health concerns (e.g., depression, anxiety and suicidal ideation). Where peers are accepting of sexual orientation, individuals may experience less isolation. The findings outlined in the results section represent the complexities of concerns and issues, including religious affiliation, frequency of contact with religious groups, internalised homophobia, coping and mental health measures. The findings captured some of the differing layers of issues for individuals, ranging from external pressures of acceptance by peers and social groups who could provide important psychosocial support (Shilo et al., Citation2016), which potentially leads to better mental health outcomes (Shilo et al., Citation2016), to internal factors such as internalised homophobia and associated beliefs about “the self” (Brewster et al., Citation2016). Each relate, and contribute to, psychological and mental health outcomes (Hamblin & Gross, Citation2013; Harari et al., Citation2014).

Limitations

The evidence included in this review suffer from a number of limitations that consequently create barriers for interpretation and comparison of data across research populations, including religious affiliation and sexual orientation or identity. There are many inconsistencies in terms of approaches, measures or psychometric tool usage and definitions of religious affiliation, sexual orientation, and mental health.

The size and scope of the existing studies, as well as the target and approach to recruitment, including US-centric representation, limit the opportunities for comparing the results across data sets. Regardless, these studies have provided the crucial initial steps of exploring the scope and prevalence of issues in specific populations and have highlighted the need to understand more about the experiences of non-US-based LGBTQ+ populations of faith or religious belief.

With the exception of a few publications, many of the published studies have been conducted in the USA. These often included the recruitment of target samples that represented either one single religion /religious belief or the target sample happened to be composed of majority one religion or religious belief. For example, studies that recruited university student populations, in some cases were recruited at “religious” universities. In some cases, the studies employed methodologies that were based on huge assumptions about the demographics of the participants, for example, the individual’s religious status being based on the university that they were undergoing their studied. Those studies that did not include a measure of religious affiliation or status and made assumptions based on the university being “religious”, could have included individuals who might associate themselves with a different religion or as “practising” or “non-practising” but affiliated, or non-religious. Either of these scenarios lead to potential differences in the data that were not recorded or accounted for and were assumed. Similarly, individual’s geographical area was used as an indicator of their religious preference leading to similar assumptions and biases in the recruited sample. Where samples were collected from a single university, school or neighbourhood, it is difficult to consider the broader representativeness and generalisability of the sample. In some cases, the necessary data was not available to the researchers, for example, in one study, the university database did not capture the sexual orientation/religious belief of their student population and therefore, it was impossible for the research to comment on the representativeness of the findings to the wider university.

The issue of representation should also be considered when accounting for the majority of studies being US based, and the representativeness and potential differences that religion may represent. The majority of the studies' samples included a good representation of Christian religions with very limited representation from other religions such as Hindu, Islam, Sikh. Therefore, comparing and understanding any similar or differentiated psychological experiences for differing religions and faiths is challenging. This leaves many questions unanswered including the complexities and psychological consequences for individuals who are LGB of religious faith and yet included in an arrange marriage. This appears to be an under-researched area, possibly due to the challenge of recruitment. Relatedly, the research area would benefit from studies with non-western samples and religions in order to make better comparisons of culture and religion.

A bigger issue exists around the development of appropriate tools to measure concepts such as religiosity and spirituality, which need to go beyond a simple capture of religious affiliation or faith in order to capture the level at which an individual is engaged in a religion or spirituality. This would allow for more appropriate comparisons to be made.

A large proportion of studies excluded from this review, captured mechanisms for integrating identities (e.g., integrating theologies) but they did not capture the psychological consequences or outcomes of the negotiation. Whilst these mechanisms are important, this review addressed the research question by focussing specifically on the “psychological consequences” of integrating sexuality and religion. That said, there are important aspects to identity formation and integration that are important for this population.

It seems timely and necessary to devise a project of work, comprising of a British / UK participant sample, capturing the diversity of the population that includes different faiths, beliefs or religions and sexual orientations. Whilst studies from American samples help our understanding of the contribution that aspects of our identity and belief have on our psychological health, there are no clear ways to compare whether cultural differences occur - which are likely given the differing levels and expressions of religious integration into our cultures. However, the existing evidence would support that a series of studies exploring the differing groups and factors in UK society should include measures of certain psychological consequences, particularly with regards to mental health; however, some careful consideration and preparation should be given when compiling appropriate measures for capturing the data.

Responding more specifically to the existing evidence, it seems necessary to develop appropriate and sensitive tools that capture a more holistic measure of “religiosity” or “spirituality”, with consideration for the differing dimensions of religion, faith or spirituality. This might include the capture of dimensions such as preoccupation, associations and commitments, integration into a community, acceptance by peers of the community, citizenship (Hemming, Citation2015; McAndrew & Voas, Citation2011) amongst other emerging factors from the emerging evidence that define religiosity, faith and spirituality. It also seems necessary to capture sexual identity beyond the standard measure of categorial Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Heterosexuality. In keeping with Geary et al. (Citation2018), measures of sexuality should be more sensitive to the dimensions which form an orientation. Therefore, considering capturing or measuring levels of sexual attraction (or interest), sexual behaviour and sexual identity are vital. Existing evidence suggests sexual identity to be how the individual defines themselves; sexual interest/attraction as what individuals want to do regardless of whether they do it; and sexual behaviour as what individuals do regardless of their sexual interest or sexual identity (Moser, Citation2016). There might be other psychological factors, which might be covariances of any associations, such as levels of resilience and personality factors that could contribute to the experience of negotiating elements of sexual orientation and religion, faith or spirituality.

This review integrated the findings from existing studies that included measures of psychological health experiences, such as individual’s well-being, happiness, suicide ideation as well as, items specific to individuals who identify as non-heterosexual, such as internalised homophobia. Whilst having measures and self-reports of important characteristics is informative in terms of making attempts to consider the consequences, it would be beneficial to consider the individuals accounts of their experiences in future research projects. A potential limitation of this review is that it was not pre-registered with the Cochrane Library of systematic reviews.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- AbdAleati, N. S., Mohd Zaharim, N., & Mydin, Y. O. (2016). Religiousness and mental health: Systematic review study. Journal of Religion and Health, 55(6), 1929–1937. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-014-9896-1

- Abu-Raiya, H., & Pargament, K. I. (2015). Religious coping among diverse religions: Commonalities and divergences. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 7(1), 24–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037652

- Barringer, M. N., & Gay, D. A. (2017). Happily religious: The surprising sources of happiness among lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender adults. Sociological Inquiry, 87(1), 75–96. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/soin.12154

- Berg, R. C., Weatherburn, P., Ross, M. W., & Schmidt, A. J. (2015). The relationship of internalized homonegativity to sexual health and well-being among men in 38 European countries who have sex with men. Journal of gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 19(3), 285–302. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2015.1024375

- Brewster, M. E., Velez, B. L., Foster, A., Esposito, J., & Robinson, M. A. (2016). Minority stress and the moderating role of religious coping among religious and spiritual sexual minority individuals. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 63(1), 119–126. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000121

- Cohen, A. B., Mazza, G. L., Johnson, K. A., Enders, C. K., Warner, C. M., Pasek, M. H., & Cook, J. E. (2017). Theorizing and measuring religiosity across cultures. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(12), 1724–1736. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167217727732

- Cranney, S. (2017). The LGB mormon paradox: Mental, physical, and self-rated health among mormon and non-mormon LGB individuals in the Utah behavioural risk factor surveillance system. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(6), 731–744. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2016.1236570

- de Jager Meezenbroek, E., Garssen, B., & van den Berg, M. (2012). Measuring spirituality as a universal human experience: A review of spirituality questionnaires. Journal of Religion and Health, 51(2), 336–354. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-010-9376-1

- Derogatis, L. R. (1993). BSI Brief Symptom Inventory. Administration, scoring, and procedures manual. (4th ed.). National Computer Systems.

- Doty, N. D., Willoughby, B. L., Lindahl, K. M., & Malik, N. M. (2010). Sexuality related social support among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(10), 1134–1147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9566-x

- Downes, M. J., Brennan, M. L., Williams, H. C., & Dean, R. S. (2016). Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open, 6(12), e011458. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011458

- Foster, A. B., Brewster, M. E., Velez, B. L., Eklund, A., & Keum, B. T. (2017). Footprints in the sand: Personal, psychological, and relational profiles of religious, spiritual, and atheist LGB individuals. Journal of Homosexuality, 64(4), 466–487. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2016.1191237

- Foster, K., Bowland, S., & Vosler, A. (2015). All the pain along with all the joy: Spiritual resilience in lesbian and gay Christians. American Journal of Community Psychology, 55(1-2), 1573–2770. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-015-9704-4

- Galen, L. (2009). Profiles of the godless. Free Inquiry, 29, 41–45. http://www.centerforinquiry.net/uploads/attachments/Profiles_of_the_Godless_FI_AugSept_Vol_29_No_5_pps_41-45.pdf

- Gattis, M. N., Woodford, M. R., & Han, Y. (2014). Discrimination and depressive symptoms among sexual minority youth: Is gay-affirming religious affiliation a protective factor? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(8), 1589–1599. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0342-y

- Geary, R. S., Tanton, C., Erens, B., Clifton, S., Prah P., Wellings K., Mitchell, K. R., Datta, J., Gravningen, K., Fuller, E., Johnson, A. M., Sonnenberg, P., & Mercer, C. H. (2018). Sexual identity, attraction and behaviour in britain: The implications of using different dimensions of sexual orientation to estimate the size of sexual minority populations and inform public health interventions. PloS one, 13(1), e0189607. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0189607

- Gibbs, J., & Goldback, J. (2015). Religious conflict, sexual identity, and suicidal behaviours among LGBT young adults. Archives of Suicide Research, 19(4), 472–488. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2015.1004476

- Green, D. E., Walkey, F. H., McCormick, I. A., & Taylor, A. J. (1988). Development and evaluation of a 21-Item version of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist with New Zealand and United States respondents. Australian Journal of Psychology, 40, 61–70. https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.1080/00049538808259070

- Hackney, C. H., & Sanders, G. S. (2003). Religiosity and mental health: A meta–analysis of recent studies. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 42(1), 43–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5906.t01-1-00160

- Hamblin, R., & Gross, A. M. (2013). Role of religious attendance and identity conflict in psychological well-being. Journal of Religion and Health, 52(3), 817–827. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-011-9514-4

- Harari, E., Glenwick, D. S., & Cecero, J. J. (2014). The relationship between religiosity/spirituality and well-being in gay and heterosexual orthodox Jews. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 17(9), 886–897. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2014.942840

- Hemming, P. J. (2015). Religion in the primary school: Ethos, diversity and citizenship. Routledge.

- Herek, G. M., Norton, A. T., Allen, T. J., & Sims, C. L. (2010). Demographic, psychological, and social characteristics of self-identified lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in a probability sample. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 7(3), 176–200. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-010-0017-y

- Igartua, K. J., Gill, K., & Montoro, R. (2009). Internalized homophobia: A factor in depression, anxiety, and suicide in the gay and lesbian population. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health, 22(2), 15–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7870/cjcmh-2003-0011

- Kim, P. Y., Kendall, D. L., & Webb, M. (2015). Religious coping moderates the relation between racism and psychological well-being among Christian Asian American college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(1), 87–94. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000055

- Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., & Martin, C. E. (1948). Sexual behavior in the human male. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Company.

- Koenig, H. G. (2009). Research on religion, spirituality and mental health: A review. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 54(5), 283. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/070674370905400502

- Koenig, H. G., McCullough, M. E., & Larson, D. B. (2001). Handbook of religion and health. Oxford University Press.

- Koenig, H., King, D., & Carson, V. B. (2012). Handbook of religion and health. Oxford University Press.

- Kralovec, K., Fartacek, C., Fartacek, R., & Plöderl, M. (2014). Religion and suicide risk in lesbian, gay and bisexual Austrians. Journal of Religion and Health, 53(2), 413–423. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-012-9645-2

- Kryzan, C., & Walsh, J. (2000). Outproud/Oasis internet survey of queer and questioning youth. from http://www.cyberspaces.com/qys2000/

- Lawrence, R. E., Oquendo, M. A., & Stanley, B. (2016). Religion and suicide risk: A systematic review. Archives of Suicide Research, 20(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2015.1004494

- Lease, S. H., Horne, S. G., & Noffsinger-Frazier, N. (2005). Affirming faith experiences and psychological health for caucasion lesbian, gay and bisexual individuals. Journal of Counselling Psychology, 52(3), 378–388. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.52.3.378

- Longo, J., Walls, N. E., & Wisneski, H. (2013). Religion and religiosity: Protective or harmful factors for sexual minority youth? Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 16(3), 273–290. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2012.659240

- Lun, V. M., & Bond, M. H. (2013). Examining the relationship of religion and spirituality to subjective wellbeing across national cultures. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 5(4), 304–315. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033641

- Marwa, W. L., & Davis, S. (2017). Is being gay in the UK seriously bad for your health? A review of evidence. Journal of Global Epidemiology and Environmental Health, 2017(1), 16–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.29199/GEEH.101019

- McAndrew, S., & Voas, D. (2011). Measuring religiosity using surveys. Survey Question Bank: Topic Overview 4, UK Data Service.

- Meltzer, H. I., Dogra, N., Vostanis, P., & Ford, T. (2011). Religiosity and the mental health of adolescents in Great Britain. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 14(7), 703–713. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2010.515567

- Meyer, I. H. (2016). Does an improved social environment for sexual and gender minorities have implications for a new minority stress research agenda? Psychology of Sexualities Review, 7(1), 81–90.

- Meyer, I. H., & Northridge, M. E. (2007). The health of sexual minorities: Public health perspectives on lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender populations. Springer.

- Moser, C. (2016). Defining sexual orientation. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(3), 505–508. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0625-y

- NICE (2014). Process and methods guide. Developing NICE guidelines: The manual. National Institute for Health and Care and Excellence, UK.

- Page, M. J., Lindahl, K. M., & Malik, N. M. (2013). The role of religion and stress in sexual identity and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual youth. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 23(4), 665–677.

- Pargament, K. I., & Raiya, H. A. (2007). A decade of research on the psychology of religion and coping: Things we assumed and lessons we learned. Psyke & Logos, 28(2), 25–25.

- Pargament, K. I., Feuille, M., & Burdzy, D. (2011). The Brief RCOPE: Current psychometric status of a short measure of religious coping. Religions, 2, 51–76. https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.3390/rel2010051

- Pargament, K. I., Smith, B. W., Koenig, H. G., & Perez, L. (1998). Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 37, 710–724. https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.2307/1388152

- Powell, L. H., Shahabi, L., & Thorensen, C. E. (2003). Religion and spirituality: Linkages to physical health. American Psychologist, 58(1), 36–52. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.58.1.36

- Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. H. (2008). Know yourself and become what you are. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 13–39. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9019-0

- Schrock, D., Sumerau, J. E., & Ueno, K. (2014). “Sexualities.”. In J. D. McLeod, E. J. Lawler, & M. Schwalbe (Eds.), Handbook of the social psychology of inequality (pp. 627–656). Springer.

- Shamseer, L., Moher, D., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., & Stewart, L. A. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (prisma-p): elaboration and explanation . BMJ, 349. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.g7647

- Shilo, G., Yossef, I., & Savaya, R. (2016). Religious coping strategies and mental health among religious Jewish gay and bisexual men. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(6), 1551–1561. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-015-0567-4

- Sink, C. A. (2004). Spirituality and comprehensive school counselling programs. Professional School Counselling, 7(5), 309–317.

- Smith, T. B., McCullouch, M. E., & Poll, J. (2003). Religiousness and depression: Evidence for a main effect and the moderating influence of stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin, 129(4), 614–636. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.4.614

- Sumerau, J. E., Mathers, L. A. B., & Cragun, R. T. (2018). Incorporating transgender experience toward a more inclusive gender lens in the sociology of religion. Sociology of Religion, 79(4), 425–448. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/socrel/sry001

- Sumerau, J. E., Nowakowski, X., Mathers, L. A. B., & Cragun, R. T. (2017). Helping quantitative sociology come Out of the closet. Sexualities, 20(5–6), 644–656. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460716666755

- Szymanski, D. M. (2006). Does internalized heterosexism moderate the link between heterosexist events and lesbians’ psychological distress? Sex Roles, 54, 227–234. https://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9340-4

- Twenge, J. M. (2017). IGen: Why today's super-connected kids are growing up less rebellious, more tolerant, less happy–and completely unprepared for adulthood–and what that means for the rest of us. Simon and Schuster.

- Walls, N. E., Kane, S. B., & Wisneski, H. (2010). Gay – straight alliances and school experiences of sexual minority youth. Youth & Society, 41(3), 307–332. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X09334957

- Wang, M. C., Wong, J. Y., Nyutu, P. N., Spears, A., & Nichols, W. (2016). Suicide protective factors in outpatient substance abuse patients: Religious faith and family support. The International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 26(4), 370–381. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10508619.2016.1174568

- Weber, S. R., & Pargament, K. I. (2014). The role of religion and spirituality in mental health. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 27(5), 358–363. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000080

- Whittemore, R., & Knafl, K. (2005). The integrative review: Updated methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 52(5), 546–553. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03621.x

- Wilkinson, D. J., & Johnson, A. (2020). A systematic review of qualitative studies capturing the subjective experiences of gay and lesbian individuals of faith or religious affiliation. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 23, 80–95, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2020.1724919

- Zinnbauer, B. J., Pargament, K. I., Cole, B., Rye, M. S., Butter, E. M., Belavich, T. G., & Kadar, J. L. (1997). Religion and spirituality: Unfuzzying the fuzzy. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 36(4), 549–564. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/1387689