ABSTRACT

Based on the rich extant research in the field of mental health in acculturation, it is calling to identify religion as one of the meditative variables of the relationship between acculturation and mental health. In addition, little knowledge exists about the detailed religious experience of Chinese migrants in Ireland. This research adopted classic grounded theory to guide data collection and analysis. The findings show that Christian faith plays a significant role as a mediator in the cross-cultural adaptation of the participants with two aspects of the mental impacts: helping to cope with mental stress and providing spiritual satisfaction. The results in this paper are part of the findings from an investigation of the religious experience of the participants during their cross-cultural adaptation in Ireland.

Introduction

Extant clinical research in areas of psychiatric and mental health provides evidence that religious practice can play a positive role on well-being (Ryan & Francis, Citation2010; Weber & Pargament, Citation2014), negative (Weber & Pargament, Citation2014), or no relationship (Wu et al., Citation2017). A meta-analysis of 34 studies (Hackney & Sanders, Citation2003) also showed a variety of results about the relationship between religious practice and mental health and ascribe it to the nature of religion from multiple perspectives, and hence leads to various relationships with mental health.

In this article, the concepts of mental and psychological are interchangeably used in their self-explanatory sense, and spiritual is an interchangeable term for mental and psychological, and in particular, refers to the inner action of a person who has a religion.

Mental health in acculturation

Acculturation is a dynamic and diversified process of adjustment and adaptation (Berry, Citation1997; Kim, Citation2001; Ward et al., Citation2001). A large body of empirical research is available about acculturation and mental health. In particular, a good body of research supports the view of Berry (Citation1997) that integration is the most successful acculturation strategy leading to positive acculturation outcome than three other strategies: assimilation, separation, and marginalisation (Eyou et al., Citation2000; Seo et al., Citation2013; Wu et al., Citation2018; Yoon et al., Citation2013). However, Koch et al. (Citation2003) found no connection between Berry’s (Citation1997) definition of acculturation and mental health among Greenlanders in Denmark but highlighted impacts of socio-demographic and socio-economic factors on mental health such as gender, age, marital position, occupation, and long-term illness. Similarly, cross sectional factors at both individual and context levels are examined such as gender, family, and community reception and their impacts on Asian immigrant mental health (Leu et al., Citation2011). Modern communication means are also assessed, such as social media sites and how they relate to the psychological well-being of Korean and Chinese international students (Park et al., Citation2014). Some research examines internalising factors on mental health in acculturation, for example, secure attachment that originated in the native cultural groups is positive for subjective well-being in cross-cultural adaptation (Hong et al., Citation2013). According to Seo et al. (Citation2013), social support and strong identity of both original and host culture are essential for the mental health of Korean–American registered nurses. The role of in-group values among a minority group, such as the ultra-Orthodox community, has a positive connection for coping with discrimination and well-being (Bergman et al., Citation2017). Strong in-group identity as experienced by the Sami people functioned as a very successful resilience factor to protect them from discrimination (Friborg et al., Citation2017).

Overall, the above literature review echoes a meta-analysis (Koneru et al. Citation2007) concerning acculturation and mental health, that complex relationship demonstrated between both aspects that is either beneficial as suggested in the mentioned Berry’s theory, or detrimental (Gfroerer & Tan, Citation2003). In summary, from the large body of research about mental health in acculturation, little knowledge is provided about the role of religious practice on mental health in the process of cross-cultural adaptation.

Mental health in acculturation of Chinese migrant community

Researchers have given great attention to the mental health of Chinese immigrants. Shen and Takeuchi (Citation2001) examine the role of acculturation on the mental health of Chinese Americans through correlates such as socio-economic status, social support, health perception, and personality negativity. Ying et al. (Citation2007) show that the sense of coherence developed from parent and peer attachment has mediated impacts on depressive symptoms among Chinese American college students. Ye and Ng (Citation2019) confirm that bicultural identity and subjective well-being are positively associated. They also highlight the importance of the person-environment fit to mental health. Xu et al. (Citation2020, p. 138) identify mental stress factors experienced by Chinese international students, such as “language, academics, cultural differences, pressure to adapt, distance from home, and difficulty with establishing new friendships and social support” and suggest a culturally sensitive intervention to manage stress. Mok et al. (Citation2014) found that Chinese people are concern about the stigma attached to exposing personal mental health illnesses. Thus, this inhibits them from seeking the relevant services.

Christianity in China and overseas

In this article, Christianity is a generic term for Protestantism and Catholicism. Christianity does not enjoy the same long history as the three dominant religious and philosophical schools of Chinese culture, namely Confucianism, Buddhism, and Taoism. In China, there are signs of a resurgence in the practice of Christianity. Among young Chinese intellectuals, this revival is remarkable (Bays, Citation2003; Yang, Citation2004). Religion is neither a focus of overseas Chinese studies, even though there is some relevant literature, mainly focusing on socio-economic contextual factors or on the Christian practices of Chinese immigrants in areas where they have a long history of migration, such as the United States and France (Rao, Citation2017). For instance, Yu and Moskal (Citation2019) show that church attendance contributes to Chinese students’ intercultural engagements, a factor that highlights the external function of institutional mechanisms in mediating between Chinese sojourners and host societies, as well as providing migrants relief from discrimination, loneliness, and anxiety experienced in cross-cultural adaptation. There is limited research on Chinese Christians in the Irish context. O'Leary and Li (Citation2008) conducted a quantitative study of Chinese migrants’ engagement with Christianity in Ireland. One of the key findings was that Chinese from mainland China were generally indifferent to religion, and instead, the participants pursued the practical benefits of the church. The study speculates that this tendency is due to the deep-rooted Confucian pragmatism in traditional Chinese culture.

Koneru et al. (Citation2007) called research to identify religiosity as one of the meditative variables of the relationship between acculturation and mental health, and until the present, there is still a lack of empirical research in this area. Chance (Citation2015) suggested using qualitative methods for future research to capture detailed personal experiences about the cultural influence on the mental health of migrants. This paper presents the findings regarding the mental impacts of practicing Christianity on Chinese migrants in Ireland during their cross-cultural adaptation.

Methods

The research questions were: if any, what were the detailed religious experiences of the participants, and how did these experiences help them cope with cross-cultural adaptation. It is an exploratory study (Creswell, Citation2003) that examines social relations (Flick, Citation1998). The researcher applied for ethics clearance and had it approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the University.

Participants

The strategy used for data gathering was convenience design using snowball sampling (Holstein & Gubrium, Citation1995). Typical snowball sampling starts with an acquaintance and then moves on to strangers. Therefore, interviewees, no matter acquaintances or strangers, are those who can provide detailed descriptions of their thoughts, feelings, and activities (Warren, Citation2001). The participants in this research are long-term and short-term residents, with a random selection of genders and beliefs, namely, Catholics, Protestants, Buddhists, and Atheists. The background of religion and faith of the 22 (n = 22) participants include Protestants (n = 12), Catholics (n = 3), Buddhists (n = 2), and no specific religion attached (n = 5). For the exclusive purpose of this paper, it only presents the relevant findings concerning the 15 Christians shown in .

Table 1. Participants’ age, gender, and background. BA: before arrival; AA: after arrival. Years of stay in Ireland refers to the end time point being interviewed.

Method of data collection

I used semi-structured interviews at the beginning of data collection then turned to a non-structured format based on the guideline of interview questions. Participants received plain language statements and consent forms and could withdraw at any point in the research. Each participant received a pseudonym, and I changed some of their details in the interview transcripts to protect their identity. Finally, I returned interview transcripts to the participants for changes or additional comments.

Analysis

According to Creswell (Citation2007), I used the Classic grounded theory (Glaser, Citation1978) to guide the entire process of data collection and analysis. The main concern of grounded theory is with the basic social process of human interaction (Glaser, Citation1978; Heath & Cowley, Citation2004), which meets the concerns of Chirkov (Citation2009a, Citation2009b) that acculturation studies should aim to discover the processes underlying migrants’ experiences.

Coding began with a substantive coding process, which shaped the empirical content of the study through open coding line by line (Glaser, Citation1978). Then followed by selective coding and allows for coding to be restricted with core categories and variables, which are closely aligned to a core category (Glaser, Citation1978). The core categories should relate to the main concerns of the research area to understand what is happening in the area. Theoretical coding is the next stage in the process, as these codes conceptualise the relationships between substantive codes (Glaser, Citation1978).

Memos written has been throughout this process beginning with detailed description and moving to elaboration at a conceptual level. The importance of memo writing is highly emphasised in Glaser (Citation1978). Memos run through data collection, coding data, sorting data, and writing. It is where the potential grounded theory comes from, as “memos are the theorizing write-up of ideas about codes and their relationships as they strike the analyst while coding” (Glaser, Citation1978, p. 83). I used Nvivo for coding purposes to manage the data.

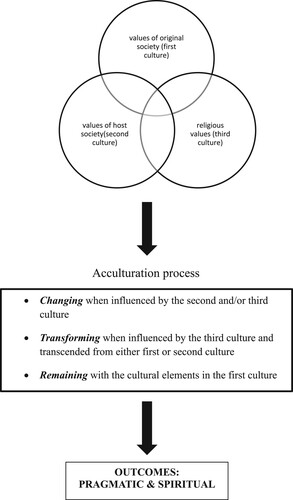

In the Appendix, shows the overall results of the research, that the changing process and retaining of the participants’ value and belief and outcome of their lives during their cross-cultural adaptation. The two resulting categories about outcome orientation of the value changing on the participants are spiritual dimension and pragmatic dimension. The paper is presenting mental impacts outcome from the spiritual dimension of the practice of Christianity amongst the participants in their cross-cultural adaptation. The details are to discuss in the next section.

Results

Two dimensions of impacts of Christianity practice emerged from the research are spiritual and pragmatic. These two dimensions are dependent on each other and non-separable, and the spiritual perspective is more prominent in this study. The following is the list of sustentative codes with emerged categories.

Along the process of selective coding, finding the most occurring codes in line with the main concern of impacts on a spiritual dimension, and remove the less occurred one such as “general impacts in acculturation” as shown in , then the resulting core categories as shown in are: to help cope with mental stress during cross-cultural adaptation, and to have spiritual satisfaction.

Table 2. Sustentative codes with emerged categories.

Table 3. Mental impacts of Christianity in acculturation.

The detailed lifeworld of the participants showed some psychological stress arose from their cross-cultural adaptation while experiencing discrimination, loneliness, homesickness, depression, and social anxiety. None of the participants experienced any mental illness during the period of this research. Some of the participants considered Christian practice provided release from these stresses. On the other hand, the participants also obtained spiritual satisfaction from their religious engagement. Thus, this research highlights some mental impacts of Christianity in the process of cross-cultural adaptation, and the details are as the following:

To help cope with mental stress in relation to cross-cultural adaptation

To help cope with discrimination

The participants reported their discrimination experience mainly are verbal attacks, ignorant attitudes, and unfair treatment in employment and workplace. Christian faith helped Ms. Zhang, Ms. Tai, and Mr. Ma to cope with discrimination experienced in their migration life. For example, Ms. Zhang dealt with her experienced indirect discrimination due to sweeping negative impressions of Chinese people and culture by relating to her faith:

I felt very pessimistic at the beginning. But after believing God, (I know) whatever you pursue in life, the ultimate purpose, also about interaction with others, all have in relation to do with God. So feel very harmonizing, know how to cope.

However, unlike Ms. Zhang, Ms. Tai, and Mr. Ma, who ambiguously experienced discrimination, Mrs. Zhao underwent serious and obvious discrimination in the workplace. Her first Irish employer, who paid her 30 Euros for working a full eight-hour day for over three months, exploited her. She found no support from outside but overcame the stress by reading the Bible and prayers to God:

When I was very upset and have no strength to deal with this matter, God's word encouraged me. Then I started to find a way out by His leading. ‘The conies are but a feeble folk, yet make their houses in the rocks’ (Proverb30:26). I understand from this Word that sometimes we seemed to be so weak, helpless, aimless, but we shall not look at ourselves but look upon our Lord. Our Lord now is living within us; we are not weak anymore.

Like Mrs. Zhao dealt with the unfair treatment in the workplace by seeking strength from her faith in Jesus Christ, Ms. Zhang, Ms. Tai, and Mr. Ma all managed to get through difficult experiences with the aid of their Christian faith.

To help deal with loneliness and homesickness

Originally, Ms. Zhang came to Ireland to study, but she had to work a lot to cover living costs as well as tuition fees. She recalled experiencing loneliness many times after hard work and living by herself:

Although I myself am able to be independent, when I am alone, mostly I felt down, also very lonely. Then wondering what this hard working may bring about.

As a way of comforting herself while confronting discrimination, Ms. Zhang also resorted to her Christian faith in loneliness during the migration journey. Similarly as recalled by Mrs. Lin in the early days of her migration:

I felt very lonely and even very depressed because there were no friends around. I did not know how to get on, and how to talk to Irish students, (unclear) friends. When I came to a Chinese church the first time, I found that I had a second home. I started to make friends there, and I met some friendly people.

For Mrs. Lin, church life at the beginning of her migration period was very helpful to drive off loneliness and felt at home in the church. Likewise, Ms. Hu, Mrs. Zhao, Mrs. Cheng, and Mrs. Hua all found church life helped them break away from loneliness. However, Ms. Liu enjoyed the socialising events and also identified church life as providing migrants with a family-like environment but she did not think she benefited from Bible teaching in Church:

Generally, on Sunday, we sing hymns, and study the Bible. Then, we often have some activities, for example go for an outing, barbecue, or climbing mountains. We have these activities regularly. So, many overseas Chinese feel it is like a family. Some Chinese I know regard Church as a club, because church provides much room for amusement, and may help me get to know some other friends.

As reflected by Ms. Liu, the friendly and family feeling in church functions as a platform for socialising for overseas Chinese like herself. What Ms. Liu sought was not the Christian teaching as believed by Mr. Wang, Mrs. Cheng, Mrs. Jiang, Mrs. Lin, Mrs. Hua, or Ms. Hu whose pursuit of religious life has an element of spiritual satisfaction. Therefore, once Ms. Liu did not feel God or church life satisfied her practical needs, she stopped her participation in church activities.

To help ease social anxiety due to intercultural difference

Ms. Zhang and Ms. Tai received supports from their faith to obtain harmonisation with Irish colleagues, as said by Ms. Zhang:

Although the intercultural difference is hard for us to see heart to heart. But, we may feel comfortable to be together … (I am) more tolerant than before to others …

Ms. Zhang understood cultural differences made it difficult for her and Irish colleagues to be close but her faith helped her from bottom of her heart to get on well with Irish people and felt very comfortable. Her faith provided her with more tolerance towards others and became concerned for others’ feelings and needs. As a result, her Irish colleagues regarded her as a sincere person. Likewise, in the case of Ms. Tai, her faith in Christianity helped her communicate with others because the Bible teaching helped her:

To build up more confidence to face people. … from Bible teaching I learned how does it like of people's hearts. As a Christian should be as salt and light in a society.

‘Salt’ here represents the meaning that prevents society from corruption, and ‘light’ means bringing the light of truth to society. Hence, for Ms. Tai, she coped with social anxiety experienced in cross-cultural adaptation, through the lens of Bible teachings and treated others with love. By doing this, she practiced faith in her daily life.

To have spiritual satisfaction

Spiritual satisfaction: to find meaning of life

Questing after the meaning of life may not have to relate to cross-cultural settings directly but it is part of the universal concern of humans regardless of whether they stay in their home country or immigrate to a foreign land. When Mr. Wang was young, he observed death happening around him then he had the fear of his own death, which must happen one day:

If I died, I will not be able to eat, nor drink, nor see anything, nor listen, nor think. Should I then become nothing? What a dreadful thing!

When Mr. Wang asked his mother about origin of man, his mother answered:

Man is dug out from the earth like a peanut (laugh).

This answer reflects that Chinese parents traditionally avoid talking about sex to their children. Mr. Wang realised the answer of his mother was a lie when he grew up. He tried to find an answer from the study of a branch of Buddhism, namely Zen. He was released in a way but found that the more he studied Buddhism, the more pessimism he felt. As he said:

Because Buddhism teaches the doctrine that all the four elements of earth, water, fire and air of which the world is made are void. It will easily make people plunge into Nihilism. Afterwards I did not think it is truth.

It was not easy for Mr. Wang to convert to Christianity has been a Zen believer for years. It was the Bible teaching that answered his many questions about the meaning of life such as:

What is the meaning of life, where do we come from? Where we are going? Does man have a soul? If we die, do we have a future? Do we have a life after death? All these questions have perplexed us. Also, speaking at a more macro-level, the mystery of universe, and the end of everything. Why do we have morality but animals do not, how to get rid of the sins in our heart? If the theory of evolution is right, then why do human have such deep and essential differences in their minds from the animals around then? Why are all these thoughts in our heads, how did they come?

Mr. Wang trusted the Bible teaching and practiced the faith seriously in his life in Ireland. Like Mr. Wang, Mrs. Jiang also tried Buddhism before she became a Christian. She found for herself Buddhism was hard to practice, as:

Buddhism teaches giving up any feeling and desire, leaving family without holding any responsibility.

Not satisfied by answers from parents, Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism, the major schools of religion and thoughts in Chinese culture, or school education, a number of participants eventually found answers in the Bible:

The Bible gave me answers about some questions I was puzzled about for a long time: where does man come from? What is the relationship between women and men (Mrs. Jiang)

To seek for the true purpose of life … after some research then I believed (Ms. Zhang)

To find beginning and end of life (Ms. Shang)

Spiritual satisfaction: to have peace and hope in mind

Apart from finding the meaning of life, Mrs. Cheng found peace and love from the Bible. She said she came from very traditional family background, and from observing her mother worshipping her god, she saw no loving relationship between a worshipper and a god:

She worships because she is afraid … because she is afraid her god will do something bad to her, so she offered this, offered that, you know.

The mother of Mrs. Cheng worshipped idols, which is popular in Chinese traditional culture. It could be a statue of Buddha or other local gods. In contrast, Mrs. Cheng is not afraid of her God as revealed in the Bible and has a loving relationship with Him. Like Mrs. Cheng who found peace from God, Ms. Hu is also comforted by her faith in Christianity. The original motivation for Ms. Hu to come to Ireland was to have some different life experiences from her life in China. However, after two or three weeks stay in Ireland, she became deeply disappointed and perplexed by her migration plan to Ireland for two reasons:

First, I felt everywhere is the same. Secondly, I began to doubt whether I am able to survive by myself. I know nobody here. No friend, no classmate, no relative … I am a girl. How can I achieve my goal? I have given up the good job in China with a good salary.

Ms. Hu began to doubt her decision of left China. Her life had not been transformed merely via a physical relocation as she expected. She concluded that the internal world of human beings is all the same; people may think in different ways but the nature of the heart of human beings is the same. She became totally lost from her original plan. Feelings of doubt, hesitation, and loneliness arose in her heart. The loss of peace and hope served as a driver for Ms. Hu to believe in Jesus. As said by Ms. Hu:

Because I have believed coming to Ireland could give me a future and I have paid a lot of money. I knew little about this country. I arrived in Ireland due to this belief. If Jesus could transform my life, and bring me the peace and hope that I need, then why not believe in Him?

Although the original dream of Ms. Hu to come to Ireland had been broken, her faith in Jesus transformed her. She changed from disappointment to being overwhelmed by the love of the Lord Jesus, from her Christian faith she obtained peace and hope.

Therefore, both Mrs. Cheng and Ms. Hu benefit from Christianity by finding peace of mind and hope which they cannot find from traditional Chinese values or personal experience, such as travelling far away from home and residing in a foreign land.

Spiritual satisfaction: to have feeling of godly love in Church

Both Mr. Li and Mr. Wang have been impressed by their experience with church members and their loving intentions and relationships. The continuous contact with a group of Christians in Ireland made Mr. Wang think about the source of loving and caring relationships among these Christians. He said:

The love is impossible in a purely human context. It can only come about because God created love within man first, and man can then love Christian brothers and sisters with this love … closer and intimate than between relatives. I have never experienced this before in my life … As the simplified Chinese character of love that has taken the part of ‘heart’ away from the traditional Chinese … Today many Chinese lack true love

Mr. Wang used a metaphor associated with the different writing of a Chinese character, to love, 爱 is the simplified format from the traditional Chinese word of 愛. The part meaning heart, 心 is missing in the simplified Chinese. Therefore, Mr. Wang referred to this change to imply people’s relationship lacks loving and caring from the heart but material interests are to maintain social networks in contemporary society in China.

Likewise, Mr. Li felt touching by the loving and caring experience that he witnessed during his stay in a Chinese church in Dublin. Consequently, he started to believe in God. Whereas, he did not come to faith before coming to Ireland even though both his mother and wife are Christians and they evangelised him when he was in China. Both Mr. Li and Mr. Wang experienced godly love in church during their migration life in Ireland.

Spiritual satisfaction: to have a sense of attachment

Mr. Ma obtained abundant experience via church life. He has a strong attachment to the church he is attending and leading:

I feel this fellowship is a very precious place to me, like my home. You ask what influence being brought from church and faith, I feel just a home, a satisfaction, find an attachment. Just because of a faith … . We do not have to remain in Ireland, but we stay because of the church, we have this church, so we have a higher level of satisfaction in it.

The main reason for Mr. Ma and his wife, Mrs. Cheng, to stay in Ireland is their church ministry. Mr. Ma sees this church as his home. Church life has given him a higher level of life in Ireland, and his attachment to his church is more important than choosing a country to live in.

Discussion

The study presents a snapshot of the life of a small group of Chinese migrants in Ireland. In particular, it probes personal religious life in terms of the mediator role of Christianity on individual well-being. As using qualitative research, it does not represent the whole group of the Chinese community in Ireland. To discuss as below:

Firstly, the nature of the qualitative approach allows the researcher to illustrate the details of the immigrants’ lived experiences. The paper presents the influence of Christianity, which is crucial to the participants’ intrinsic interaction with the host society. However, it does not deny the impacts of various other possible factors in their cross-cultural adaptation, such as their original cultural values, identity, social support, and intercultural influences from the host society.

Secondly, Christian practices helped the migrants in this study go through difficult times in their cross-cultural adaptation and provided them with spiritual fulfilment. It founds that Christian practices help the participants to have a healthy and balanced psychological state in their daily life as a migrant. Although their Christian life may have led to the isolation of some participants from their Irish host society and Chinese ethnic group in their religious life, it reported no negative impact on the personal well-being of the participants. However, as this is a qualitative study, it only reflects the acculturation strategies of a small group of immigrants. In other words, it is not sufficient to refute the argument that integration is the most successful acculturation strategy (Berry, Citation1997).

Thirdly, it is necessary to distinguish a nominal believer from a true believer about the spiritual effects of Christian practice. A nominal believer attends a church but does not have any faith in Jesus Christ, the core of the Christian faith. According to the question and answer 36 of shorter Westminster Catechism, a set of the doctrine of Christianity (Meade, Citation2000), only a true believer with indwelling Holy Spirit can enjoy these benefits flowing out from the Spirit, such as the “assurance of God’s love, peace of conscience, joy in the Holy Spirit” (Meade, Citation2000, p. 120). This study presents the impacts of Christian practice on the participants regarding their mental/spiritual perspective rather than the practical dimension highlighted in O'Leary and Li (Citation2008). Nonetheless, it does not mean the participants do not have pragmatic concerns.

Fourthly, the second point also emphasises the internal function of practicing the Christian faith. It helps the participants cope with mental stress and have spiritual satisfaction. Instead, Yu and Moskal (Citation2019) mainly shed light on the external function of attending church regarding relevant intercultural engagement.

Fifthly, the research shares similarity regarding the meditative role of in-group values of the ultra-Orthodox community, the in-group identity of the Sami people, both in-group values and identity have positive impacts on dealing with discrimination and improve well-being (Bergman et al., Citation2017; Friborg et al., Citation2017).

Conclusion

Religion is one of the main perspectives of human culture. People may pursue religion and faith no matter where they live. Similarly, wherever one lives and works, one may encounter psychological problems, and the scenario in a cross-cultural context is different from one's place of origin or birth. In particular, this study describes the role of the Christian faith in the cross-cultural adaptation of individuals. Future research may adopt a mixed approach to explore and measure to what extent Christian beliefs can influence psychological well-being in cultural adjustment.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bays, D. H. (2003). Chinese Protestant Christianity today. The China Quarterly, 174(3), 488–504. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0009443903000299

- Bergman, Y. S., Horenczyk, G., & Abramovsky-Zitter, R. (2017). Perceived discrimination and well-being among the ultra-Orthodox in Israel: The mediating role of group identity. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48(9), 1320–1327. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022117722859

- Berry, W. J. (1997). Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology, 46(1), 5–34.

- Chance, L. J. (2015). Beyond somatization: Values acculturation and the conceptualization of mental health among immigrant Chinese Canadian families [unpublished thesis], University of Victoria.

- Chirkov, V. (2009a). Critical psychology of acculturation: What do we study and how do we study it, when we investigate acculturation? International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 33(2), 94–105. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2008.12.004

- Chirkov, V. (2009b). Summary of the criticism and of the potential ways to improve acculturation psychology. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 33(2), 177–180. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2009.03.005

- Creswell, J. W. (2003). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. Sage.

- Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design—choosing among five approaches. Sage.

- Eyou, M. L., Adair, V., & Dixon, R. (2000). Cultural identity and psychological adjustment of adolescent Chinese immigrants in New Zealand. Journal of Adolescence, 23(5), 531–543. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.2000.0341

- Flick, U. (1998). Introduction to qualitative research. Sage Publications.

- Friborg, O., Sørlie, T., & Hansen, K. L. (2017). Resilience to discrimination among indigenous Sami and non-Sami populations in Norway: The SAMINOR2 study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48(7), 1009–1027. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022117719159

- Gfroerer, J. C., & Tan, L. L. (2003). Substance use among foreign-born youths in the United States: Does the length of residence matter? American Journal of Public Health, 93(11), 1892–1895. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.93.11.1892

- Glaser, B. G. (1978). Theoretical sensitivity: Advances in the methodology of grounded theory. The Sociology Press.

- Hackney, C. H., & Sanders, G. S. (2003). Religiosity and mental health: A meta-analysis of recent studies. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 42(1), 43–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5906.t01-1-00160

- Heath, H., & Cowley, S. (2004). Developing a grounded theory approach: A comparison of Glaser and Strauss. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 41(2), 141–150. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7489(03)00113-5

- Holstein, J. A., & Gubrium, J. F. (1995). The active interview. SAGE Publications.

- Hong, Y.-Y., Fang, Y., Yang, Y., & Phua, D. Y. (2013). Cultural attachment: A new theory and method to understand cross-cultural competence. Journal of Intercultural Studies, 44(6), 1024–1044. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022113480039

- Kim, Y. Y. (2001). Becoming intercultural: An integrative theory of communication and cross-cultural adaptation. Sage Publications.

- Koch, M., Bjerregaard, P., & Curtis, C. (2003). Acculturation and mental health – empirical verification of J.W. Berry’s model of acculturative stress. International Journal of Circumpolar Health, 63(suppl. 2), 371–376.

- Koneru, V. K., Weisman de Mamani, A. G., Flynn, P. M., & Betancourt, H. (2007) Acculturation and mental health: Current findings and recommendations for future research. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 12(2), 76–96. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appsy.2007.07.016

- Leu, J., Walton, E., & Takeuchi, D. (2011). Contextualizing acculturation: Gender, family, and community reception influences on Asian immigrant mental health. American Journal of Community Psychology, 48(3–4), 168–180. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-010-9360-7

- Meade, S. (2000). Training hearts, teaching minds: Family devotions Based on the shorter catechism. P and R Publishing.

- Mok, H., Miao, S., Au, R., Ganesan, S., & McKenna, M. (2014). Regional differences among ethnic Chinese on level of acculturation to Canadian culture and perceived barriers to mental health help seeking. World Cultural Psychiatry Research Review, 9(3), 81–88.

- O'Leary, R., & Li, L. (2008). Mainland Chinese students and immigrants in Ireland: Their engagement with christianity, churches and Irish society. Agraphon Press.

- Park, N., Song, H., & Lee, K. M. (2014). Social networking sites and other media use, acculturation stress, and psychological well-being among east Asian college students in the United States. Computers in Human Behavior, 36, 138–146. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.037

- Rao, X. (2017). Revisiting Chinese-ness: A transcultural exploration of Chinese Christians in Germany. Studies in World Christianity, 23(2), 122–140. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3366/swc.2017.0180

- Ryan, M. E., & Francis, A. J. P. (2010). Locus of control beliefs mediate the relationship between religious functioning and psychological health. Journal of Religion and Health, 51(3), 774–785. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-010-9386-z

- Seo, K., Kim, M., Lee, G., Park, J., & Yoon, J. (2013). The impact of acculturation and social support on mental health among Korean-American registered nurses. Korean Journal of Adult Nursing, 25(2), 157–169. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7475/kjan.2013.25.2.157

- Shen, B. J., & Takeuchi, D. T. (2001). A structural model of acculturation and mental health status among Chinese Americans. American Journal of Community Psychology, 29(3), 387–418. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010338413293

- Ward, C., Bochner, S., & Furnham, A. (2001). The psychology of cultural shock. Routledge.

- Warren, A. B. C. (2001). Qualitative interviewing. In J. F. Gubrium & J. A. Holstein (Eds.), Handbook of interview research (pp. 83–101). Sage.

- Weber, S. R., & Pargament, K. I. (2014). The role of religion and spirituality in mental health. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 27(5), 358–363. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000080

- Wu, F., Gong, Q., & Dai, Y. (2017). Study on a Christian Chinese sample: Sense of self-worth, well-being and locus of control. Mental Health, Religion & Culture, 20(3), 239–245. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13674676.2017.1338680

- Wu, Q., Ge, T., Emond, A., Foster, K., Gatt, J. M., Hadfield, K., Mason-Jones, A. J., Reid, S., Theron, L., Ungar, M., & Wouldes, T. A. (2018). Acculturation, resilience, and the mental health of migrant youth: A cross-country comparative study. Public Health, 162, 63–70. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2018.05.006

- Xu, H., O'Brien, W. H., & Chen, Y. (2020). Chinese international student stress and coping: A pilot study of acceptance and commitment therapy. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 15, 135–141. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.12.010

- Yang, F. (2004). Between secularist ideology and desecularizing reality: The birth and growth of religious research in communist China. Sociology of Religion, 65(2), 101–119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/3712401

- Ye, S., & Ng, T. K. (2019). Value change in response to cultural priming: The role of cultural identity and the impact on subjective well-being. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 70, 89–103. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2019.03.003

- Ying, Y.-W., Lee, P. A., & Tsai, J. L. (2007). Attachment, sense of coherence, and mental health among Chinese American college students: Variation by migration status. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 31(5), 531–544. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2007.01.001

- Yoon, E., Chang, C.-T., Kim, S., Clawson, A., Cleary, S. E., Hansen, M., Bruner, J. P., Chan, T. K., & Gomes, A. M. (2013). A meta-analysis of acculturation/enculturation and mental health. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(1), 15–30. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030652

- Yu, Y., & Moskal, M. (2019). Why do christian churches, and not universities, facilitate intercultural engagement for Chinese international students? International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 68, 1–12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2018.10.006