ABSTRACT

People with elevated materialistic values often report reduced life satisfaction. To understand this, our study investigated if gratitude and the spiritual jihad mindset, denoting the aspiration to bond with God through spiritual challenges, mediate this relationship. We surveyed 404 Muslim young adults (191 men; 213 women; aged 19–32) from Pakistan. Findings revealed a negative correlation between materialism and gratitude, spirituality, and life satisfaction. Conversely, gratitude, spirituality, and life satisfaction positively correlated with each other. Importantly, spiritual jihad was a negative mediator between materialism and life satisfaction, while gratitude was not significant in this role. Thus, for Muslim Pakistani university students, chasing materialistic ambitions may adversely impact well-being by neglecting spiritual closeness to Allah.

People who are more focused on material gains tend to be less satisfied with life (Belk, Citation1984; Dittmar et al., Citation2014; Richins, Citation1995; Roberts et al., Citation2015; Sirgy, Citation1998); however, little research has examined explanations for this relationship. Based on prior work conducted in Western cultures showing that materialism related negatively to gratitude and religiousness/spirituality (r/s) (e.g., Burroughs & Rindfleisch, Citation2002; Lambert et al., Citation2009; McCullough et al., Citation2002), a recent study involving Muslim, Pakistani university students tested whether the negative relationship between materialism and life satisfaction would be accounted for by lower levels of gratitude and r/s (Perveen et al., Citation2017). Surprisingly, results showed that life satisfaction related positively to materialism and that gratitude (but not r/s) partially mediated this association; that is, higher levels of gratitude partly accounted for the link between higher materialism and higher life satisfaction. Because these results were novel and unexpected, and because the findings were obtained using a measure of r/s that was not specific to Islam, we aimed to test the aforementioned mediation model using a measure designed to specifically tap into Islamic r/s, spiritual jihad, which reflects a mindset of growing closer to God through moral struggles (Saritoprak et al., Citation2018). In the literature review presented next, we highlight research supportive of the original expectation regarding a negative relationship between materialism and life satisfaction, as well as the expectations that this association would be mediated by lower levels of gratitude and spiritual jihad (Saritoprak et al., Citation2020).

Materialism and life satisfaction

Materialism involves people placing high importance and significance on “worldly possessions”, which hold “a central place in their lives and provide the greatest sources of satisfaction and dissatisfaction” (Belk, Citation1984, p. 291). Numerous studies show that people who put a higher value on worldly possessions are more dissatisfied with their lives in general (e.g., Belk, Citation1984; Richins, Citation1995, Citation2004, Citation2013; Roberts et al., Citation2015; Sirgy, Citation1998), with meta-analytic findings showing a small but consistent negative association (Dittmar et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, other findings are indirectly supportive of the idea that more materialistic individuals may experience lower levels of life satisfaction. For example, Kasser (Citation2002), and Kasser and Ryan (Citation1993, Citation1996, Citation2001) and Kasser et al. (Citation2004) conducted a series of studies showing that people scoring higher on materialism very rarely experience moments of positive emotions and are more prone to symptoms of depression, anxiety, and substance abuse. Similarly, other studies showed that materialism related negatively to self-esteem (Richins & Dawson, Citation1992) and positively to depression (Mueller et al., Citation2011) and loneliness (Pieters, Citation2013). Further, materialism is associated not only with lower individual well-being but lower societal well-being (Moldes & Ku, Citation2020).

Gratitude as a mediator of the association between materialism and life satisfaction

Definitions of gratitude emphasise its multidimensional nature. McCullough et al. (Citation2002) conceptualised gratitude as an emotional trait, mood, or emotion. Fitzgerald (Citation1998) delineated gratitude into three key components: (a) an ardent and deeper sense of gratefulness for something or someone, (b) benevolent behaviour and feelings towards a person or a thing, and (c) a subsequent affinity to act positively. Though Perveen et al. (Citation2017) found that higher levels of gratitude partially mediated a positive association between materialism and life satisfaction, there is a great deal of empirical and theoretical work suggesting that gratitude should negatively mediate the association between materialism and life satisfaction.

Materialism and gratitude

Multiple correlational and experimental studies have shown inverse associations between materialism and gratitude (Lambert et al., Citation2009; McCullough et al., Citation2002; Polak & McCullough, Citation2006; Tsang et al., Citation2014). There are several plausible explanations for these findings. First, materialism and gratitude may be in direct opposition to one another; that is, materialism is about wanting more, whereas gratitude is about being content and grateful for what one already has (McCullough et al., Citation2002). Similarly, Bauer et al. (Citation2012) argued that materialistic values instigate other self-centered values (such as social status and power). In contrast, gratitude connects people to self-transcendent values such as benevolence and a sense of universalism (Froh et al., Citation2011). Finally, Polak and McCullough (Citation2006) claimed that gratitude instills feelings of conjugation and connection with others; in turn, people with higher levels of gratitude may experience feelings of security and completeness that are inconsistent with materialistic drives.

Gratitude and life satisfaction

Research shows that gratitude positively relates to life satisfaction and other variables indicating higher levels of well-being, including vitality, happiness, hope, and optimism, while gratitude relates negatively to anxiety and depression (McCullough et al., Citation2002; Portocarrero et al., Citation2020). Indeed, gratitude is among the best predictors of life satisfaction out of 24 positive psychological indicators (Park et al., Citation2004). Gratitude is also robustly linked to mental and physical health in numerous experimental and longitudinal studies (Jans-Beken et al., Citation2020). Watkins (Citation2004) proposed that people who possess higher levels of gratitude have a more positive outlook on life and noted that gratitude related positively to considering negative experiences as less influential on the present. Hence, gratefulness may diminish the negative effect of bad memories and might help reframe them.

In sum, evidence from prior studies suggests there is good reason to believe that materialism should negatively predict gratitude and that gratitude positively predicts life satisfaction. Building on such findings, we hypothesised that lower levels of gratitude might partially explain the negative association between materialism and life satisfaction.

Spiritual jihad as a mediator of the association between materialism and life satisfaction

Spiritual jihad

Definitions and operationalizations of r/s vary widely in the psychology of religion literature (Dyson et al., Citation1997; Hall, Citation1998; Zullig, Ward, & Horn, Citation2006), which presents challenges for conceptualisation and measurement in any particular study. Yet there is growing consensus that spirituality reflects the search for the sacred, and religion refers to spirituality within the context of an identifiable group or institution (Harris et al., Citation2018) Saritoprak et al. (Citation2018) created a measure to assess a specific kind of spirituality within Muslim populations. The authors proposed the construct of spiritual jihad as an effortful striving against one’s lower impulses (ie, al-nafs) to live in closer alignment with Allah (Picken, Citation2011). Saritoprak et al.’s (Citation2018) measure includes items that assess the degree to which people endorse a spiritual jihad mindset in the face of moral struggles (e.g., strive against their al-nafs in order to grow spiritually, become closer to Allah, and receive benefits in the afterlife). Muslim adults in the United States who scored higher on spiritual jihad regarding a specific moral struggle also reported higher levels of spiritual growth and more daily spiritual experiences with God. They were more likely to use positive religious coping strategies (Saritoprak et al., Citation2018). We reasoned that this measure of spiritual jihad would be well-suited for use in the current sample of Muslims living in Pakistan.

Materialism and spiritual jihad

There are a few reasons that we expected materialism to relate negatively to spiritual jihad. One straightforward reason is that spiritual jihad involves a concern with spiritual – and therefore nonmaterial – issues. More specifically, spiritual jihad is about struggling against one’s lower impulses, which include those directed toward the pursuit of worldly gains. This is in direct contrast to a materialistic outlook on life. Thus, in the face of moral struggles, we would not expect people that have higher materialistic values would turn away from materialistic goals to focus on spiritual strivings. Although no research has directly investigated the link between materialism and spiritual jihad, there is some work in other cultural contexts suggesting that materialism and religiousness/spirituality are negatively related (Burroughs & Rindfleisch, Citation2002; Rakrachakarn et al., Citation2015). Moreover, a recent review work by Wood et al. (Citation2010) suggests that gratitude is positively associated with wellbeing, whereas a meta-analysis by Moldes and Ku (Citation2020) suggests that materialism has adverse effects of materialism on individual and societal well-being. This begs the question of how these concepts are associated with religious spirituality.

Spiritual jihad and life satisfaction

We also proposed that spiritual jihad would relate positively to life satisfaction. The idea of being closer to Allah and overcoming one’s lower impulses may be fulfilling and thus could create a greater sense of overall well-being and contentment. Surprisingly, Saritoprak et al. (Citation2018) found null associations between spiritual jihad and life satisfaction. However, the authors proposed that because the assessment of spiritual jihad focused on a particular moral struggle, the benefits from taking this mindset might not have pervaded a person’s broader sense of well-being. We planned to assess spiritual jihad in general and predicted that this overarching state of mind would relate positively to global life satisfaction. In sum, we hypothesised that spiritual jihad would relate negatively to materialism and positively to life satisfaction and further that spiritual jihad would partially mediate the negative association between materialism and life satisfaction.

Cultural considerations

A number of studies show that materialism is related more strongly to lower well-being in collectivistic cultures such as Singapore (Keng et al., Citation2000) and Malaysia (Baker et al., Citation2013), as compared to individualistic cultures. Valuing material possessions might be less likely to produce happiness in cultures where the majority of people do not share these values. Thus, materialism may be particularly important to study in collectivistic cultures. This research will explore the relationship between materialism and life satisfaction in a sample of young adults in the collectivistic culture of Pakistan.

Summary and overview of the current study

Positive associations between materialism and life satisfaction may be particularly unexpected in collectivistic societies such as Pakistan. Thus, in a conceptual replication of Perveen et al. (Citation2017), we tested whether lower levels of gratitude and r/s (using a measure of Muslim r/s, specifically, spiritual jihad) would partially mediate the expected negative association between materialism and life satisfaction. We based this model on the following hypotheses derived from the literature review:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): There will be negative zero-order correlations between materialism with gratitude, spiritual jihad, and life satisfaction.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): There will be positive correlations between gratitude, spiritual jihad, and life satisfaction.

Methods

Participants

The initial sample included 435 young adults. A total of 404 participants (191 men; 213 women; Age range = 19–32 years old; Mean age = 22, SD = 1.80) were included in the final study. This was decided to meet the inclusion criteria that we only included participants who completed at least 80% of the questionnaire and identified as Muslims. Only these participants’ data were included in our final analysis.

Procedure

This study was reviewed by the ethics committee members of Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto University of Science and Technology (SZABIST, September 2019). All participants volunteered for this participation, and hence they did not receive any financial incentives for participating in this study. We used two procedures to recruit participants: In-person recruitment (the majority of participants); and online recruitment (a small minority of participants). In the case of in-person recruitment, research assistants approached potential participants during university classes in the cities of Karachi, Lahore, and Islamabad. Research assistants confirmed via interview that participants spoke English, and were adult Muslims. However, due to Islam being the majority religion in Pakistan, we also added religious orientation as an additional item to the survey (1 = not at all religious; 7 = very religious; the average score on this item was M = 4.73; SD = 1.04; Less religious = 2.5%; slightly religious = 7.9%; Neutral = 29%; slightly religious = 38%; religious = 19.6; very religious = 3%).

Participants completed informed consent forms, and the majority filled out the questionnaire in paper-pencil format. After providing informed consent, participants completed paper-and-pencil surveys assessing demographics as well as the psychological variables of interest. In the online data collection format of the study, we recruited university student participants from the same geographic areas electronically using invitations via email lists, email, and Facebook. Those who were reached out via university lists and email announcements completed the questionnaire in an online format by filling out the same survey electronically using Google Docs. After completing data collection, all data was removed from google forms due to privacy concerns.

Measures

Scores for all measures described below were computed by averaging across items (after reverse scoring where applicable).

Materialism

We assessed materialism with the 15-item version of Richins and Dawson’s (Citation1992) Material Values Scale (MVS), with items rated on a Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The scale measures three dimensions of materialism with five items each: success (e.g., “I admire people who own expensive homes, cars, and clothes”), centrality (e.g., “Buying things gives me a lot of pleasure”), and happiness (e.g., “I’d be happier if I could afford to buy more things”). After factor analysis using principal component analysis (Eigenvalue for single factor = 5.97, which explains 29.78% of the variance). This was also in accordance with the better reliability of the scale based on all items (α = .80) Therefore, it was decided that aggregate scale scores would be used. Higher scores on MVS meant higher agreement with material values (Materialism).

Gratitude

We assessed gratitude with the six-item Gratitude Questionnaire as an effective trait (GQ-6; McCullough et al., Citation2002). The scale uses a Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), including items such as “I have so much in life to be thankful for” and “I am grateful for a wide variety of people”. Principal component analysis showed that all items loaded on a single factor (Eigenvalue for single factor = 4.15, which explains 38.86% of the variance). The scale reliability was also acceptable (α = .62). Higher scores on GQ-6 meant higher agreement with experiencing Gratitude.

Spiritual jihad

We assessed spiritual jihad with the 15-item Spiritual Jihad Scale developed by Saritoprak et al. (Citation2018). Participants are prompted as follows: “Think of a type of moral struggle you have experienced or are currently experiencing in life. How did/do you view the struggle you experienced/are experiencing?” Example items are: “I have been thinking of my struggle as a test that will make me closer to Allah” and “I do not see the struggle as part of my spiritual growth” (reversed). Five of the 15 items are reverse-scored. Items are rated on a seven-point Likert-type scale from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Principal component analysis showed that all items loaded on a single factor (Eigenvalue for single factor = 16.49, which explains 59.62% of the variance). The scale reliability was also acceptable (α = .95). Higher scores on Spiritual Jihad Scale meant higher levels of Spiritual Jihad.

Life satisfaction

We assessed life satisfaction with the five-item Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., Citation1985). The scale uses a seven-point Likert-type scale to rate the items from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Sample items include, “In most ways, my life is close to ideal”, and “If I could live my life over again, I would change nothing”. Principal component analysis showed that all items loaded on a single factor (Eigenvalue for single factor = 15.14, which explains 58.67% of the variance). The scale reliability was also acceptable (α = .95). Higher scores on Spiritual Jihad Scale meant higher levels of Spiritual Jihad.

Results

We used IBM SPSS-27 and base functions in R (R Development Core Team, Citation2020), including ggplot2. Before testing the main hypothesis of our study, we conducted descriptive statistical analysis, principal component analysis, alpha reliability, and correlational analyses. All results are presented below.

Descriptive statistics and correlations

shows descriptive statistics, reliability, and intercorrelations among scales. All scales showed substantial between-person variation and acceptable-to-good reliability. Correlational results supported all predictions encompassed by H1 (materialism related negatively to all other variables) and H2 (positive correlations among gratitude, spiritual jihad, and life satisfaction).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations.

Multiple mediation model

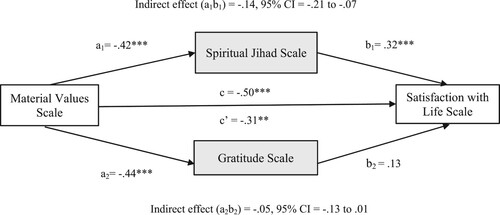

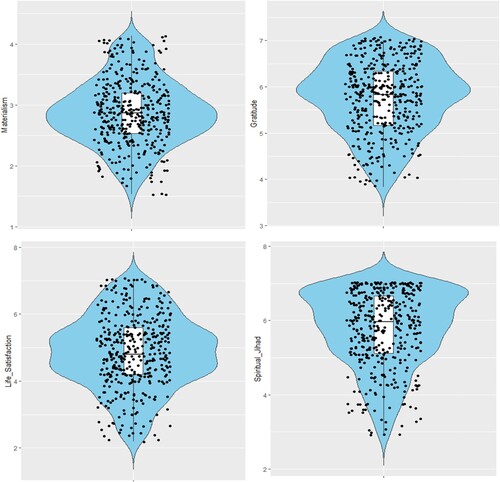

Prior to computing a multiple mediation model, all variables of interest were explored for their normal and acceptable distribution using violin graphs. Please see for the distribution of each variable. We used the Process package and the mediate function to test direct and indirect effects using the bootstrapping procedures that Preacher and Hayes (Citation2004) recommended. In this procedure. In this process, MVS was entered as a predictor, the Satisfaction with Life Scale was entered as an outcome variable, and Gratitude Scale and Spiritual Jihad scale were entered as mediators. Using 5000 bootstrap samples, the model estimated bias-corrected standard errors and 95% confidence intervals for the indirect effects of materialism on life satisfaction via gratitude and spiritual jihad. All estimates are unstandardised regression coefficients. As shown in , the spiritual jihad mindset was a significant negative mediator of the relationship between materialism and life satisfaction, as predicted. In other words, the negative association between materialism and life satisfaction partially accounted for by lower levels of spiritual jihad. Contrary to predictions, gratitude was not a significant mediator. The indirect effect of materialism on life satisfaction accounted for 28% of the total effect of materialism on life satisfaction. The direct effect of materialism on life satisfaction remained significant.

Figure 1. Response distributions for variables.

Note: The violin charts display response distributions, with box plots marking the 25th and 75th percentiles and a bolded line for the median. Vertical lines indicate values within 1.5 times the interquartile range. The data suggests a normal competence distribution in the control condition, as Skewness and Kurtosis range between –1 and +1. Metrics for select variables include Materialism (Median: 2.86, SD: .54), Gratitude (Median: 5.83, SD: .78), Life Satisfaction (Median: 4.80, SD: 1.10), and Spiritual Jihad (Median: 5.96, SD: 1.04).

Discussion

We aimed to examine the relationships among materialism, gratitude, spiritual jihad, and life satisfaction in a sample of Pakistani Muslim participants. Results from correlational analyses supported our bivariate hypotheses that materialism would relate negatively to gratitude, spiritual jihad, and life satisfaction and that the latter three variables would correlate positively with each other. Results from a multiple mediation model did not support the hypothesis that the negative relationship between materialism and life satisfaction would be mediated by lower levels of gratitude but did support the hypothesis that lower levels of spiritual jihad would mediate this relationship. These results were largely in line with previous work on the relationships among the variables of interest (e.g., McCullough et al., Citation2002; Roberts et al., Citation2015; Tsang et al., Citation2014) but contrasted with the results from Perveen et al. (Citation2017), which documented a positive association between materialism and life satisfaction and found this association to be mediated in part by higher levels of gratitude. The contrast between our findings and those from Perveen et al. (Citation2017) is notable, however, it is common for individual studies to obtain different associations between variables simply due to sampling error (Borenstein et al., Citation2011). One other potential reason for discrepant results was due to different measures of r/s being used across studies. Compared to the general r/s measure in Perveen et al., our measure of spiritual jihad is more closely aligned with specific aspects of Muslim spirituality, namely, striving to overcome al-nafs to grow spiritually, get closer to God, and attain the benefits of a positive afterlife. Believing that one is achieving these goals may associate more strongly with (low) materialism and (high) life satisfaction than r/s involvement in general. Ultimately, further research involving Pakistani Muslims will hone in on the strength of associations more precisely in this population. Overall, the results from our study may increase our understanding of why materialism predicts lower life satisfaction, particularly within a collectivistic society where materialism may be highly devalued (Baker et al., Citation2013; Keng et al., Citation2000).

Explaining the negative relationship between materialism and life satisfaction

Although gratitude related to materialism (negatively) and life satisfaction (positively) as expected given previous research (Portocarrero et al., Citation2020; Tsang et al., Citation2014) our hypothesis that gratitude would mediate materialism-life satisfaction was not supported. We note that the 95% CI of the indirect effect through gratitude was mostly positive; however, even if the effect is positive in actuality, it would still be a small effect. We speculate that gratitude likely accounts for some of the variance in the negative relationship between materialism and life satisfaction, yet some of the shared variance between gratitude and life satisfaction may have been accounted for by spiritual jihad in the multiple mediation model (which would result in diminished strength of the path from materialism to life-satisfaction through gratitude). It is possible that higher levels of gratitude are, in part, concerned specifically with gratitude to God (Rosmarin et al., Citation2011). The measure of spiritual jihad may have subsumed this variance because it taps into perceiving a close relationship with God.

Results provided support for the hypotheses that spiritual jihad would relate to materialism negatively and life satisfaction positively, as well as for the hypothesis that lower levels of spiritual jihad would mediate the negative relationship between materialism and life satisfaction. People who value materialism are concerned with worldly gains, whereas spiritual jihad encompasses strivings that are transcendental or “out of this world” to some degree. And not only do the pursuits of wealth, status, and power associate negatively with attempts to get closer to God through moral struggles, but foregoing spiritual attainment partially explains why materialism is negatively associated with life satisfaction. Notably, these findings are in contrast to one previous study on spiritual jihad and life satisfaction, which observed a null association (Saritoprak et al., Citation2018). However, the authors of that study measured spiritual jihad regarding a specific moral struggle and suggested that a broader measure of spiritual jihad like the one used in the current study would relate to satisfaction with life. These findings should be considered within the context of the limitations presented next.

Limitations

First, though we tested a mediational model, we cannot make causal claims due to reliance on a correlational, cross-sectional design. Experimental research would be required to evaluate the causal relationships between materialism, life satisfaction, and gratitude and to establish the directionality implied by our model.

Our sample characteristics present some limitations to generalizability. Specifically, participants were university students from universities in three large Pakistani cities. Geographic regions and educational settings may be relevant to one’s value system. The sample was also homogenous in terms of religious affiliation and socioeconomic status. These characteristics may lead to more similar values and norms among participants. For instance, Muslim individuals, in particular, may have relatively more negative views toward materialism (Edis & BouJaoude, Citation2014). Because the study was limited to people having access to education in English and the internet, participants belonged mostly to the middle or upper middle socio-economic class. Excluding people with lower socioeconomic status may limit results; for instance, materialism may be more adaptive to psychological health for such individuals if it motivates the attainment of goods that lead to a higher quality of life and, thus, greater life satisfaction.

Since this is a correlational study, we cannot draw a causational explanation of these findings. Moreover, other alternative explanations to the mediation model are possible. For example, it is possible that people who score high on the spiritual jihad scale are more prone to confirm to social norms. This is particularly relevant since the data was collected in a religious, collectivistic, and confirmative culture (Anjum, Citation2020; Anjum et al., Citation2019). It is plausible that overall need to conform with conventions and collectivistic values could also be related to life-satisfaction in a collectivist culture of Pakistan.

Finally, the survey involved self-reports of life satisfaction, spirituality, materialism, and gratitude. Although self-reports of values and well-being may be preferred because the self is uniquely positioned to report accurately on internal states and motivations, responses may be subject to social desirability biases. Participants may be especially likely to exaggerate socially desirable characteristics such as values, spirituality, and well-being. However, having participants fill out the survey anonymously may mitigate this concern.

Conclusion

In summary, the current study investigated the relationships among materialism, gratitude, spiritual jihad, and life satisfaction in a sample of Pakistani Muslim participants. Results indicated that materialism had negative associations with gratitude, spiritual jihad, and life satisfaction, and that the latter three variables had positive associations with each other. The study also found that lower levels of spiritual jihad, but not gratitude, mediated the negative relationship between materialism and life satisfaction. These findings contribute to our understanding of why materialism predicts lower life satisfaction, particularly within a collectivistic society where materialism may be highly devalued. However, the study has some limitations, such as its correlational design, limited generalizability due to the homogeneity of the sample, and potential social desirability biases in self-reported measures. Future research using experimental designs and more diverse samples would be necessary to establish causality and increase the generalizability of these findings. Overall, the results from this study may have practical implications for promoting well-being and reducing the negative impact of materialism in collectivistic societies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anjum, G. (2020). Women’s activism in Pakistan: Role of religious nationalism and feminist ideology among self-identified conservatives and liberals. Open Cultural Studies, 4(1), 36–49. https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2020-0004

- Anjum, G., Kessler, T., & Aziz M. (2019). Cross-cultural exploration of honor: Perception of honor in Germany, Pakistan, and South Korea. Psychological Studies, 64(2), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-019-00484-4

- Baker, A. M., Moscis, G. P., Ong, F. S., & Pattanapanyasat, R.-P. (2013). Materialism and life satisfaction: The role of stress and religiosity. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 47(3), 548–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12013

- Bauer, M. A., Wilkie, J. E. B., Kim, J. K., & Bodenhausen, G. V. (2012). Cuing consumerism: Situational materialism undermines personal and social well-being. Psychological Science, 23(5), 517–523. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611429579

- Belk, R. W. (1984). Three scales to measure constructs related to materialism: Reliability, validity, and relationships to measures of happiness. In T. Kinnear (Ed.), Advances in consumer research, 11 (pp. 291–297). Association for Consumer Research.

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P., & Rothstein, H. R. (2011). Introduction to meta-analysis. John Wiley & Sons.

- Burroughs, J. E., & Rindfleisch, A. (2002). Materialism and well-being: A conflicting values perspective. Journal of Consumer Research, 29(3), 348–370. https://doi.org/10.1086/344429

- Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

- Dittmar, H., Bond, R., Hurst, M., & Kasser, T. (2014). The relationship between materialism and personal well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(5), 879–924. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037409

- Dyson, J., Cobb, M., & Forman, D. (1997). The meaning of spirituality: A literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 26(6), 1183–1188. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.1997.tb00811.x

- Edis, T., & BouJaoude, S. (2014). Rejecting materialism: Responses to modern science in the Muslim Middle East. In M. R. Matthews (Ed.), International handbook of research in history, philosophy and science teaching (pp. 1663–1690). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7654-8_52

- Fitzgerald, P. (1998). Gratitude and justice. Ethics, 109(1), 119–153. https://doi.org/10.1086/233876

- Froh, J. J., Emmons, R. A., Card, N. A., Bono, G., & Wilson, J. A. (2011). Gratitude and the reduced costs of materialism in adolescents. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12(2), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-010-9195-9

- Hall, B. A. (1998). Patterns of spirituality in persons with advanced HIV disease. Research in Nursing & Health, 21(2), 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X(199804)21:2<143::AID-NUR5>3.0.CO;2-J

- Harris, K. A., Howell, D. S., & Spurgeon, D. W. (2018). Faith concepts in psychology: Three 30-year definitional content analyses. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 10(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000134

- Jans-Beken, L., Jacobs, N., Janssens, M., Peeters, S., Reijnders, J., Lechner, L., & Lataster, J. (2020). Gratitude and health: An updated review. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(6), 743–782. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2019.1651888

- Kasser, T. (2002). The high price of materialism. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/3501.001.0001

- Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1993). A dark side of the American dream: Correlates of financial success as a central life aspiration. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65(2), 410–422. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.2.410

- Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1996). Further examining the American dream: Differential correlates of intrinsic and extrinsic goals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(3), 280–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167296223006

- Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (2001). Be careful what you wish for: Optimal functioning and the relative attainment of intrinsic and extrinsic goals. In P. Schmuck & K. Sheldon (Eds.), Life goals and well-being: Towards a positive psychology of human striving (pp. 116–131). Hogrefe & Huber Publishers.

- Kasser, T., Ryan, R. M., Couchman, C. E., & Sheldon, K. M. (2004). Materialistic values: Their causes and consequences. In Psychology and consumer culture: The struggle for a good life in a materialistic world (pp. 11–28). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10658-002

- Keng, K. A., Jung, K., Jiuan, T. S., & Wirtz, J. (2000). The influence of materialistic inclination on values, life satisfaction and aspirations: An empirical analysis. Social Indicators Research, 49(3), 317–333. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006956602509

- Lambert, N. M., Fincham, F. D., Stillman, T. F., & Dean, L. R. (2009). More gratitude, less materialism: The mediating role of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4(1), 32–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760802216311

- McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J-A. (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(1), 112–127. https://doi.org/10.1037/3514.82.1.112

- Moldes, O., & Ku, L. (2020). Materialistic cues make us miserable: A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence for the effects of materialism on individual and societal well-being. Psychology & Marketing, 37(10), 1396–1419. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21387

- Mueller, A., Mitchell, J. E., Peterson, L. A., Faber, R. J., Steffen, K. J., Crosby, R. D., & Claes, L. (2011). Depression, materialism, and excessive internet use in relation to compulsive buying. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 52(4), 420–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.09.001

- Park, N., Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Strengths of character and well-being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23(5), 603–619. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.23.5.603.50748

- Perveen, A., Mehmood, B., & Yasin, M. G. (2017). Materialism and life satisfaction in Muslim youth: Role of gratitude and religiosity. Pakistan Journal of Psychological Research, 32(1), 231–245. https://pjpr.scione.com/cms/abstract.php?id=234

- Picken, G. (2011). Spiritual purification in Islam: The life and works of al-Muhasibi. Routledge.

- Pieters, R. (2013). Bidirectional dynamics of materialism and loneliness: Not just a vicious cycle. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(4), 615–631. https://doi.org/10.1086/671564

- Polak, E. L., & McCullough, M. E. (2006). Is gratitude an alternative to materialism? Journal of Happiness Studies, 7(3), 343–360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-005-3649-5

- Portocarrero, F. F., Gonzalez, K., & Ekema-Agbaw, M. (2020). A meta-analytic review of the relationship between dispositional gratitude and well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 164, 110101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110101

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36(4), 717–731. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03206553

- R Development Core Team. (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing. https://www.r-project.org/

- Rakrachakarn, V., Moschis, G. P., Ong, F. S., & Shannon, R. (2015). Materialism and life satisfaction: The role of religion. Journal of Religion and Health, 54(2), 413–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-013-9794-y

- Richins, M. L. (1995). Social comparison, advertising, and consumer discontent. American Behavioral Scientist, 38(4), 593–607. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764295038004009

- Richins, M. L. (2004). The Material Values Scale: Measurement properties and development of a short form. Journal of Consumer Research, 31(1), 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1086/383436

- Richins, M. L. (2013). When wanting is better than having: Materialism, transformation expectations, and product-evoked emotions in the purchase process. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1086/669256

- Richins, M. L., & Dawson, S. (1992). A consumer values orientation for materialism and its measurement: Scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Research, 19(3), 303–316. https://doi.org/10.1086/209304

- Roberts, J. A., Tsang, J. A., & Manolis, C. (2015). Looking for happiness in all the wrong places: The moderating role of gratitude and affect in the materialism–life satisfaction relationship. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(6), 489–498. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1004553

- Rosmarin, D. H., Pirutinsky, S., Cohen, A. B., Galler, Y., & Krumrei, E. J. (2011). Grateful to God or just plain grateful? A comparison of religious and general gratitude. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(5), 389–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2011.596557

- Saritoprak, S. N., Exline, J. J., & Abu-Raiya, H. (2020). Spiritual jihad as an emerging psychological concept: Connections with religious/spiritual struggles, virtues, and perceived growth. Journal of Muslim Mental Health, 14(2). https://doi.org/10.3998/jmmh.10381607.0014.205

- Saritoprak, S. N., Exline, J. J., & Stauner, N. (2018). Spiritual jihad among U.S. Muslims: Preliminary measurement and associations with well-being and growth. Religions, 9(5), 158.

- Sirgy, M. J. (1998). Materialism and quality of life. Social Indicators Research, 43(3), 227–260. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006820429653

- Tsang, J.-A., Carpenter, T. P., Roberts, J. A., Frisch, M. B., & Carlisle, R. D. (2014). Why are materialists less happy? The role of gratitude and need satisfaction in the relationship between materialism and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 64, 62–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.02.009

- Watkins, P. C. (2004). The psychology of gratitude. In M. E. M. R. A. Emmons (Ed.), Gratitude and subjective well-being (pp. 123–141). Oxford University Press.

- Wood, A. M., Froh, J. J., & Geraghty, A. W. (2010). Gratitude and well-being: A review and theoretical integration. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(7), 890–905. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.005

- Zullig, K. J., Ward, R. M., & Horn, T. (2006). The association between perceived spirituality, religiosity, and life satisfaction: The mediating role of self-rated health. Social Indicators Research, 79(2), 255–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-005-4127-5