ABSTRACT

Flourishing is a growing topic in positive psychology, and the positive influences of flourishing have been well documented. Although recent literature has shown that religion has an impact on one’s physical and psychological well-being in positive ways, the relationship between religiosity and flourishing has surprisingly not been studied. The present study aimed to explore the relationship of religious faith with flourishing and psychological distress. An online survey has successfully recruited 267 participants from UK and Taiwan. The survey used standardised inventories including the PERMA Profiler, the Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire, and the Clinical Outcome in Routine Evaluation to measure flourishing, religious faith and psychological distress respectively. Results show that participants with strong religious faith do have higher levels of flourishing. Yet Path Analysis shows that participants who have stronger religious faith is indirectly related to lower psychological distress through the mediating effect of flourishing. Suggestions for future research and implications of the findings are discussed.

Introduction

The major focus of psychology has long been about understanding psychopathogenic issues and their treatment and relief. The paradigm changed some 25 years ago with the development of positive psychology, such as human well-being, human flourishing or virtues that had not been discussed before, when Martin Seligman promoted the new domain of positive psychology. In general, positive psychology emphasises both individual and social well-being and seeks to answer the question of “What makes one’s life most worth living?” (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2014) Human flourishing is one of the most important elements and a central concept in contemporary positive psychology. In the positive psychology world, flourishing is a multi-dimensional concept, meaning it is made up of a number of key aspects, and optimal flourishing only happens when one reaches a healthy level of each dimension. As the topic of human flourishing has been growing rapidly, many scales and tools have been developed in order to measure an individual’s level of flourishing. In the majority of studies, flourishing is explained by using the well-being theory PERMA model, created by Seligman (Citation2011), and this has become one of the most well-known theories. This well-being model has been widely used in many different research areas, and these five elements, according to Coffey et al. (Citation2016), are independently empirically supported predictors of flourishing. Apart from these five elements that measure people’s levels of flourishing, VanderWeele (Citation2017), has proposed that religious faith or spiritual health may play an important role when seeking flourishing. In psychological terms, religion can be defined as a set of spiritual beliefs or practices centred on the worship of an all-powerful deity and includes behaviours such as prayer, meditation, and involvement in group rituals. Religion may provide people with a feeling of purpose and meaning in their lives, as well as a sense of community and belonging. It can also bring consolation and support during stressful situations (Lun & Bond, Citation2013). This study seeks to explain flourishing using the PERMA theory and the relationship between religious faith and flourishing.

To begin with positive emotions, a study by Saroglou et al. (Citation2008) has found that religiosity was affected by positive emotions, and the study concluded that religiosity and spirituality fit the broaden-and-build-theory of positive emotions. Additionally, Van Cappellen et al. (Citation2016) indicate that positive emotions mediated the relationship between religion, spirituality and well-being. Secondly, engagement is the experience of completely employing one’s skills, strengths, and attention to life activities. Being engaged in life challenges can produce an experience known as “flow” according to Csikszentmihalyi (as cited in Shernoff et al., Citation2014). Flow is a gratifying experience that people are eager to do for itself, not for the benefits it would bring. Flow occurs when an individual’s skills are sufficient for challenges in pursuit of clear goals with feedback on progress towards the objective. People can experience flow in a variety of activities such as having a work task, having a good conversation, having sports training, reading a book, and writing. Being engaged usually increases people’s general life satisfaction (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2014). Positive relationships usually involve the feeling of being socially integrated. The experience or feeling that leads to well-being is frequently triggered by being supported or cared for by others (Seligman, Citation2011). Additionally, religiosity has benefits in creating and maintaining positive relationships among individuals. For example, Lakatos and Martos (Citation2019), revealed that religiosity plays a supportive role in relationships. The American Psychological Association (Citation2014) also pointed out that religious couples experience stronger relationship commitment. Next, living a meaningful life entails seeking and pursuing a purpose bigger in influence and importance than one's own happiness. Recent literature has found that religion has a considerable influence when individuals are seeking meaning in life. For instance, Krok’s (Citation2015) study, has shown that meaning in life is an essential element of religious coping and psychological well-being. He also proposed that religion promotes varied viewpoints of meaning in life by providing ultimate motivation for components of an individual's life, defining goals, and helping to instil a deeper sense of meaning in life. Finally, seeking achievement is one way to lead or cultivate one’s flourishing. Research by McCullough and Willoughby (Citation2009) discovered that religion influences individuals when they are pursuing their achievements, and selecting and managing their goals.

Cultivating flourishing is not only important because it helps people feel good, but also as it is beneficial to everyday life and real-world consequences. Higher levels of flourishing are associated with numerous benefits and impacts, such as having better physical health, having better self-regulation and coping abilities, having more resilience, and so on. For example, a study by Makin et al. (Citation2021) found that people recovering from alcohol problems had higher levels of flourishing compared to people suffering from mental illness. The study also explained it might be because people experience the benefits of abstinence, and this gives them hope and motivation to remain sober and continue with recovery, and eventually increased their levels of flourishing. Hence, it is safe to say learning and fostering flourishing are needed. A study by Ekman and Simon-Thomas (Citation2021) established a framework that has three pillars, including connection, positivity, and resilience (CPR). This framework was distilled from empirical studies in psychology and neuroscience, as well as an applied pedagogy of flourishing. They offered this framework and were teaching it through an online course. The researchers concluded that building skills and knowledge related to the CPR framework naturally and demonstrably enhances the experiences and behaviours that foster flourishing. As such, it can be concluded that it is important to teach people or learn about well-being as it can strengthen one’s flourishing.

The world has become increasingly secular, but religion continues to play an important role in many people’s lives. The Pew Research Centre (Citation2010) has mentioned that around 84% of the world’s population identify themselves with a religious group, and only one-in-six people in the world have no affiliation to any religion. This means that many people still actively practice some form of religious belief. Recent literature reported that attending religious services, religious events, studying scriptures, devotion, and praying regularly can be beneficial for mental health and well-being. Braam and Koenig’s (Citation2019) meta-analysis study found that approximately 49% of current studies carried out on this subject concluded that religion caused a decreasing level of depression over time. They also highlighted that religiosity tends to protect persons suffering from mental illness more than those suffering from physical ailments. In addition, Plante et al. (Citation2000) have suggested that the strength of religious faith was substantially connected with optimism, a sense of meaning in life, coping with stress, viewing life as a positive challenge, self-acceptance and lower anxiety.

Furthermore, religious beliefs have been linked to better self-management of symptoms in persons with bipolar disorder (Mitchell & Romans, Citation2003). The results of the National Institute of Mental Health Epidemiologic Catchment Area survey, also supports the notion that attending weekly religious services more regularly is associated with relatively lower occurrences of most anxiety disorders, which include generalised anxiety disorder, social phobia, agoraphobia, and a comparatively higher incidence of obsessive-compulsive disorder in younger individuals with stronger religious beliefs (Koenig et al., Citation1993). What is more, religious or spiritually themed support groups were found to improve self-esteem, quality of life, and community participation in persons with schizophrenia (Sageman, Citation2004). Sullivan (Citation1993) explained that religious beliefs and practices provide encouragement, social support, and insights to people suffering from chronic severe mental diseases, including schizophrenia. While having a religious faith or doing religious practices do not cause either schizophrenia or any other mental illness, but Tateyama et al. (Citation1993), discovered that deeply held religious beliefs might potentially exacerbate delusions.

Another longitudinal study conducted by Sibley and Bulbulia (Citation2012) have proposed a novel finding, that is when individuals who lost their faith after natural disasters or tragic events, had significant mental health decline. Whereas those who did not experience any natural disasters or tragic events did not have mental health decline after they gave up their religion. This shows that religiosity helps increase one’s mental health. The study also found that mental health and subjective well-being are unlikely to improve if secular people become religious just after a natural crisis. But upholding faith, having regular religious practices like praying, or regularly participating in religious events, might be important steps in supporting individuals on the road to recovery from traumatic events.

Psychological distress can be termed an emotional suffering state linked to daily life demands and stressors. This makes individuals struggle to cope with their normal daily life. Different studies ascertain that a complex relationship between religious faith and psychological distress exists. This follows that religious faith serves a positive emotional function that constantly reduces peoples’ psychological distress symptoms such as depression and anxiety. Religiosity buffers the impact posed by psychological distress on an individual. Some researchers indicate that religious faith and beliefs tend to have a significant influence on one's mental health condition and level. According to Ismail and Desmukh (Citation2012), there exists a negative correlation between anxiety and religiosity, adding to the positive correlation between religiosity and life satisfaction. It can be concluded that people with intense religious faith show lower levels of psychological distress as they find happiness in their religions, leading to higher levels of life satisfaction. Besides, religion is a protective factor explaining why most religious people turn to prayers when faced with life challenges. It also fosters a positive coping mechanism as it offers them hope and meaning, which helps them cope with their problems. Despite the relationship existing between the religious faith and psychological distress, there is still a need for more robust research.

In the current study, the aim is to investigate the relationships between religious faith, human flourishing, and psychological distress. Flourishing has been widely studied with many other factors like mental health or physical health. There are also studies that looked at the relationship between religious faith, happiness, well-being, and other factors. Even though VanderWeele (Citation2017) highlighted that religious or spiritual health should be one of the components when measuring human flourishing, the topics of religious faith and flourishing have hardly been studied together. Besides, most research was conducted in Western countries and selected particular groups of samples such as Christian religious communities or older age participants, instead of with the general population. Rather than the measurement on individuals’ overall religious faith, previous research mainly focused on factors like religious practice, religious engagement, or religious attendance. Therefore, this present study will examine the relationship between religious faith, flourishing and psychological distress in samples mainly from the UK and Taiwan populations, and includes samples with Eastern religions. This study is perhaps the first paper looking at the relationships between overall religious faith and flourishing by using the two specific assessment instruments, the PERMA profiler and the Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire (SCSRFQ). It is initially hypothesised that a) strong religious faith group have higher level of flourishing and lower level of psychological distress; b) in general, religious faith, flourishing, and psychological distress correlate significantly; c) religious faith and flourishing are equally good predictors for psychological distress.

Method

A cross-sectional quantitative method was conducted to achieve the aims of the study and answer the research questions. A questionnaire was delivered online on the Qualtrics platform, with both English and Traditional Chinese versions and non-probability convenience sampling was used. A total sample was made up of 267 participants, with 21.3% (n = 57) identifying as male, 75.7% (n = 202) identifying as female, and 3% (n = 8) identifying as “other” or “prefer not to say”. The age range of the subjects was between 18 and 71 years old, with a mean of 34 years old.

Measurements

The questionnaire started with ten demographic questions and then continued with three self-report assessment tools including the PERMA profiler, the SCSRFQ, and the Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation (CORE-10). All the demographic questions and assessment tools were in the same order in both English and Chinese versions of the survey. In particular, the assessment tools in the Chinese version of the survey used the official translation of the questionnaires with Chinese characters.

PERMA profiler

To measure participants’ levels of flourishing, the PERMA profiler created by Butler and Kern (Citation2016) was used in this study. The scale has 23 items with 11 points that measure one’s general well-being, which was developed to capture the five domains of flourishing-based on Seligman’s (Citation2011) PERMA theory. And the scale comprised the five PERMA subscales with 15 items including positive emotions (items 5, 10, 22), engagement (items 3, 11, 21), relationships (items 6, 15, 19), meaning (items 1, 9, 17), and accomplishments (items 2, 8, 16). The scale also measured physical health (items 4, 13, 18), negative emotions (items 7, 14, 20), loneliness with a single item (item 12) and the last item on the scale measured overall happiness (item 23). To get the overall flourishing score, add the PERMA score from 15 items to the overall happiness score. The PERMA profiler demonstrated strong internal consistency with Cronbach’s alpha .94 and test-retest reliability was found at .78 among eight studies (Butler & Kern, Citation2016). The scale also demonstrated acceptable validity. Overall PERMA scores specifically correlate .84 with the Flourishing Scale (Sun et al., Citation2018), and .80 with the Short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (Stewart-Brown et al., Citation2009).

Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire

Religious faith was measured using the SCSRFQ, which was developed by Plante and Boccaccini (Citation1997). This self-report questionnaire contains ten items and participants were asked to rate each statement on a four-point Likert type scale. The possible total score ranges from ten to 40, when all items are added up. Studies have suggested good internal consistency reliability of the SCRSFQ with Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients ranging from .94 to .97. and split-half reliability scores ranging between .90 and .96, which was regarded as a highly reliable instrument for measuring the strength of religious faith and engagement (Plante, Citation2010; Plante & Boccaccini, Citation1997).

Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation (CORE-10)

To measure psychological distress, the CORE-10 developed by Connell and Barkham (Citation2007) was utilised. The CORE-10 is a widely used short measure of psychological distress, and it was derived from the original 34 item Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation- Outcome Measures (CORE-OM). CORE-10 demonstrated good internal reliability with an alpha value of .90, and the score of the CORE-10 was highly correlated with the CORE-OM in both clinical and non-clinical samples, with .94 and .92 respectively (Barkham et al., Citation2013).

Ethical considerations

Before conducting the research, the ethics of this study were approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Education and Psychology in the University of Bolton in line with current British Psychological Society (BPS) ethical guidelines. Before starting to fill out the survey, full consent in electronic form at the beginning of the questionnaire was obtained from all participants. This research was accessible to anybody over the age of 18, and participation was completely voluntary. Participant anonymity was preserved, and all information gathered was kept confidential. For data storage, all responses obtained were gathered and stored on the online software system “Qualtrics,” with password protection. All the datasets downloaded from Qualtrics were kept in a password protected laptop and were only used for research purposes in this present study. All data were stored in line with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Procedure

After receiving ethical approval from the Research Ethics Committee of the University of Bolton, two versions of the online questionnaires, an English and Chinese version, were created and published through the online Qualtrics software. All the demographic questions and assessment tools were in the same order in both English and Chinese versions of the survey. In particular, three assessment tools in the Chinese version of the survey used the official translation in order to make sure the meaning of the contents matched well with the original English version.

Participants could access the questionnaire easily and were able to complete the questionnaire with any electronic device. The survey link was posted on social media platforms and was shared and emailed with friends, family, churches, and religious communities. The information sheet was included in the survey which explained the rationale of the research, a brief summary, participants’ rights, and mental health support helplines and websites in both the UK and Taiwan were provided. Following the information sheet, the electronic format of the consent form was shown which highlighted the ethical nature of the study. Participants were then asked to read and provide their consent. The study only continued when participants clicked the “Yes, I agree to take part” button which meant they agreed to give consent.

Statistical analysis

Incomplete data were cleaned, and missing values handled and were coded as “999” before data analysis. Data and variables were further checked for normality by comparing the mean with the 5% trimmed mean, skewness, kurtosis, one-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test, histogram, and normal Q-Q Plots. Descriptive statistics on variables were carried out and presented. Binary variables were created for weak or strong faith. Then, the more conservative Mann–Whitney U tests is used to test if there is real difference between groups. The statistical power was set to .05 and the effect size (r) was calculated utilising the formula, divided z scores by the square root of observation number (r = z/√n). Finally, linear regression tests were conducted to test research question, which was “Examine whether religious faith or flourishing is a better predictor of psychological distress.”

To test the mediating role of flourishing in the relationship between religious faith and psychological distress, a mediation analysis with a bootstrapping method was performed (Hayes, Citation2013). There are three criteria to determine whether the mediating pathway is significant or not. First, the relationship between the independent variable and the mediator should be significant (path a). Second, the relationship between the mediator and the dependent variable should be significant while controlling for the independent variable (path b). Third, the indirect effect, as calculated by the product of the regression coefficients for path a and path b (a x b), should be significant (Hayes, Citation2013). The analysis was conducted with 5000 bootstrapping replications, using PROCESS macro version 4.1. An alpha level of .05 was used to determine statistical significance for direct effects, and a 95% confidence interval was used to determine statistical significance for the indirect effect. Finally, Spearman’s correlation was tested to seek relationships between variables including the total score on flourishing, Santa Clara score, and CORE-10 score.

Results

Sample demographies

Our flourishing scores (n = 267, M = 106.88, SD = 28.30) are significantly higher than that of Carson et al.’s (Citation2020) (n = 1608, M = 101.47, SD = 27.73); t(1873) = -2.944, p = .003, Hedge’s g = .19. We also used a slightly higher clinical cut-off, though the mean score of CORE-10 of this study of (M = 13.12, SD = 7.56) is very close to the previous research (M = 12.82, SD = 7.61); t(1863) = -.587, p = .557, Hedge’s g = .03. Kolmogorov–Smirnov test on total score on Flourishing, total score on Santa Clara scale, and total score on CORE-10 showed that these variables were not normally distributed because the scores of these variables were all significantly different (p < .001) from the normal distribution. Therefore, non-parametric statistics were used to analyse the data ().

Table 1. Demographic features of the participants (N = 267).

Strong vs weak faith group difference

To test the hypothesis, the Mann–Whitney U test was conducted to compare weak faith versus strong faith with two dependent variables, the total scores of flourishing and the total score of CORE-10. As can be seen from below, only the total score of flourishing showed a statistically significant difference (p < .001) between weak and strong religious faith groups. Participants with strong religious faith scored significantly higher on flourishing, but they did not score lower on CORE-10. Therefore, the hypothesis is only partially confirmed.

Table 2. Mann–Whitney U Test results for participants with weak faith versus strong faith on flourishing and CORE-10.

Correlational analysis

Non-parametric Spearman’s rho correlation analysis was conducted because the variables were not normally distributed in this study. As can be seen from Table 5, there was a strong, negative, statistically significant relationship between flourishing and CORE-10 (rs = -.621, p < .001), which indicated participants with higher flourishing were more likely to have less psychological distress. Flourishing also weakly correlated with SCSRFQ (rs = .271, p < .001), which implied that participants who have higher flourishing tended to have stronger religious faith. As mentioned above, flourishing and SCSRFQ were correlated. However, when Spearman's rho correlation coefficient was conducted to assess the relationship between SCSRFQ and CORE-10, there was no correlation between these two variables ().

Table 3. Model summary of the regression analysis on predictors of CORE-10.

Regression analysis

To test the research question, multiple linear regression was conducted in order to find the best predictor of psychological distress in the study. The analysis showed a significant regression model (F(2, 254) = 93.41, p < .001) for predicting psychological distress. The adjusted R2 value of .424 suggested that the variances in the predictor variables account for 42.4% into psychological distress. The analysis revealed that the score on flourishing (β = -.662) was the most influential predictor. In , the collinearity statistics variance inflation factor (VIF) showed that no variables were highly correlated, therefore, it suggested there was no evidence shown for multicollinearity. Also, there was no evidence of homoscedasticity.

Table 4. Coefficients table looking at predictors of CORE-10.

Path analysis

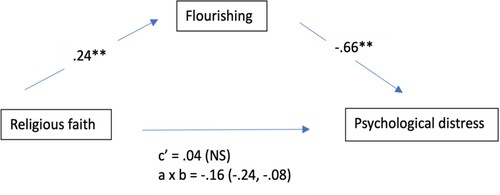

The results of the mediation analysis are presented in and . Although religious faith was not directly related to psychological distress (B = .03, SE = .04, p = .36), the indirect effect of religious faith on psychological distress, via the mediating effect of flourishing, was significant (a x b = -.12, 95% CI = -.19, -.06) ().

Table 5. Spearman’s rho correlations coefficient between flourishing score, Santa Clara score, and CORE-10 score.

Table 6. Results for mediation analyses (N = 257).

Discussion

The basic assumption behind the combined use of positive (SCSRFQ for religious faith and PERMA for flourishing) as well as conventionala negative scales (CORE-10 for psychological distress) is obviously the appreciation of complex relationship that may exist between these constructs. It is a further improvement over a simple zero-sum logic. The results of this study partially supported the first tested hypothesis. Those with strong religious faith would have significantly higher levels of flourishing but not significantly lower level of psychological distress. On one hand, the group with stronger religious do enjoy better flourishing status yet interestingly they do not have significantly lower psychological distress. This finding contradicts previous study findings which suggest that religious practice is related to lower levels of depression and anxiety (Boelens et al., Citation2012; Stroope et al., Citation2022). One plausible reason is that participants with severe psychological distress are less likely to join this study. Among those who have no, mild or moderate psychological distress, there are participants of varied religious faith, making linear association insignificant between religious faith and psychological distress, and consistently making no significant difference in psychological distress for groups with strong/weak religious faith. Another reason may be due to the difference of sample subjects. Previous studies recruited subjects with clinical or sub-clinical conditions while this study captured the general public.

For the research question as to whether the religious faith or flourishing is a better predictor for psychological distress, regression analysis was conducted and the results suggested that 42.4% of psychological distress could be predicted by religious faith and flourishing. The total score on flourishing was found to be a stronger predictor of psychological distress. In fact, the mediation analysis reveals that flourishing fully mediates the relationship between religious faith and psychological distress. In other words, higher religious faith is indirectly related to lower psychological distress, via the mediating effect of flourishing. Our study findings infer that the relationship between religious faith and psychological distress should be examined through its underlining mechanisms which are not fully understood at the moment.

It is conceptually fallable to see religious faith entirely through a psychological lense, nor at a moment sensible enough to propose that flourishing can replace religious faith in promoting resilience and meaningful life. A co-existence model between the two may reflect better realities. Yet theologians and psychologists may have to prepare for the encounter and exchange, and be prepared to work for the common good.

While the current study clearly demonstrates the associations between religious faith, flourishing and psychological distress, it is important to note that it is much easier to measure one’s flourishing but more difficult to predict levels of psychological distress which may be transient and contingent in nature. To overcome this issue, future study may be conducted among subjects with depression (relatively stable but distressed) to observe the augment effect of either flourishing or religious faith. The current cross-sectional study does not allow us to determine the direction or causality of the associations between variables. For instance, whether persons under constant distress will have diminishing faith in religion, and whether religious faith under certain circumstances will “tense up” the person. Therefore, the results must be interpreted carefully, and probably longitudinal research is needed to ascertain the direction of the associations between variables.

Since religious faith often involves personal beliefs and commitment, its mitigating effect on the person’s psychological health is always difficult to be operationalised and measured, not to mention the exceptions and complicated situation of strong religious faith claimed by those who did not attend any religious activities. On the other hand, flourishing has a broader concept and application irrespective of one’s religion. More flourishing-based treatment could have been developed with efficacy carefully monitored for people with and without religious faith. Having said that, religious faith remains one of the most fundamental resources for people in distress. There is no point of replacing religious faith with flourishing. Instead, the indirect pathway of religious faith should be further researched.

Limitations of the study

There are limitations in this study, both general and specific ones. Firstly, the study has a large gender imbalance, with 75.7% of the participants being female and only 21.3% male (see ). However, previous research (Slauson-Blevins & Johnson, Citation2016) did confirm this problem and found that women are more likely to complete online surveys. Secondly, the sample size was relatively small in this study, with only 267 participants. Even though the study has found some novel results, a larger sample size is needed as it would produce more generalisable results. Furthermore, despite the fact that the survey was published and promoted in both UK and Taiwan, the sample was a little culturally homogenous and not exceptionally diverse as there were more participants from Taiwan than from the UK. Thirdly, like other research involving the use of online surveys, the conditions under which the participants completed the survey were unknown and uncontrolled, unlike in a classroom setting. In addition, for the convenience of collecting data, the responses from participants in most online survey research are self-reported. Self-report has been shown to have limitations due to self-report bias and social desirability bias (Paulhus & Vazire, Citation2007). Another specific limitation inherent to the use of SCSRFQ to measure religious faith is that it has been more able to discriminate mild to moderate religious levels rather than higher levels (Cummings et al., Citation2015), and therefore cautions have to be taken in interpreting the results of the high faith group. It remains to be debated much in the future as in the past whether complex religious faith can be measured in simple ways like the 10-item SCSRFQ. Finally, if specific insights are to be drawn, it can hardly go without data from carefully planned qualitative methods. Indepth interviews would have gained more richer insight as to how their religious experiences augment/decline and how their religious faith helps them cope with the challenges in life. The cross-sectional design self-report online survey did not allow us to fully understand the direction or causality of the associations between variables. While this study carried out comfortably the regression analysis on the three main constructs, a bigger sample size is needed if it is to test a more complicated model. The limitation of small sample size from different countries has been well noted.

Implications and suggestions

Following on from the previous discussion, it is evident that there is a need for more research on flourishing, religious faith, and psychological distress. Firstly, as mentioned in the section on the limitations of the study, longitudinal is necessary as all these three constructs can change over time and often are contingent upon different life experiences. Qualitative research is needed in order to generate more insights and understanding on the subject matter. Secondly, to better validate the findings of this study, similar studies need to be conducted with a larger and more diverse sample. Future research should try to access groups with better gender representation, because the current study largely represents the female gender. Future studies should also attempt to collect more data through religious organisations.

The main findings of this research are that people who have strong religious faith also have higher levels of flourishing. In line with previous studies that found being religious is linked to many well-being outcomes and then leads to higher flourishing (Koenig et al., Citation2012; VanderWeele, Citation2017), the current study, has identified that religious faith may have an important role to play in enhancing flourishing. Yet how to enhance flourishing remains a challenge for practitioners and researchers. For faith communities, religious practice that enhances flourishing should be promoted. While we witness the proliferation of “secular” practices such as mindfulness and meditation, empirical studies about religious practice such as hymn singing, worship and prayer should also be encouraged and funded particularly by faith communities.

Conclusions

Religious faith continues to be a very important resource for people of different religions or dominions. How it happened and what effect it has on the person’s psychology and well-being are considered important research questions. Psychological study like this one, provided a good example of how other knowledge fields may help to understand religious faith better. This study never means to provide any definitive clue, but serves as a starting point to understand religious faith and its relationship with both positive (flourishing) and negative (psychological distress) aspects of psychology.

References

- American Psychological Association. (2014). Religion or spirituality has a positive impact on romantic/marital relationships, child development, research shows. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2014/12/religion-relationships.

- Barkham, M., Bewick, B., Mullin, T., Gilbody, S., Connell, J., Cahill, J., Mellor-Clark, J., Richards, D., Unsworth, G., & Evans, C. (2013). The CORE-10: A short measure of psychological distress for routine use in the psychological therapies. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 13(1), 3–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733145.2012.729069

- Boelens, P. A., Reeves, R. R., Replogle, W. H., & Koenig, H. G. (2012). The effect of prayer on depression and anxiety: Maintenance of positive influence one year after prayer intervention. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 43(1), 85–98. https://doi.org/10.2190/PM.43.1.f

- Braam, A. W., & Koenig, H. G. (2019). Religion, spirituality and depression in prospective studies: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 257, 428–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.06.063

- Butler, J., & Kern, M. L. (2016). The PERMA-profiler: A brief multidimensional measure of flourishing. International Journal of Wellbeing, 6(3), 1–48. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v6i3.526

- Carson, J., Prescott, J., Allen, R., & McHugh, S. (2020). Winter is coming: Age and early psychological concomitants of the Covid-19 pandemic in England. Journal of Public Mental Health, 24(3), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1108/JPMH-06-2020-0062

- Coffey, J. K., Wray-Lake, L., Mashek, D., & Branand, B. (2016). A multi-study examination of well-being theory in college and community samples. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(1), 187–211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9590-8

- Connell, J., & Barkham, M. (2007). CORE-10 user manual, version 1.1. CORE System Trust & CORE Information Management Systems Ltd.

- Cummings, J. P., Carson, C. S., Shrestha, S., Kunik, M. E., Armento, M. E., Stanley, M. A., & Amspoker, A. B. (2015). Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire: Psychometric analysis in older adults. Aging & Mental Health, 19(1), 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2014.917606

- Ekman, E., & Simon-Thomas, E. (2021). Teaching the science of human flourishing, unlocking connection, positivity, and resilience for the greater good. Global Advances in Health and Medicine, 10. https://doi.org/10.1177/21649561211023097

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

- Ismail, Z., & Desmukh, S. (2012). Religiosity and psychological well-being. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3(11), 20–28.

- Koenig, H. G., Ford, S. M., George, L. K., Blazer, D. G., & Meador, K. G. (1993). Religion and anxiety disorder: An examination and comparison of associations in young, middle-aged, and elderly adults. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 7(4), 321–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/0887-6185(93)90028-J

- Koenig, H. G., King, D., & Carson, V. B. (Eds.). (2012). Religion: Good or bad? In H. G. Koenig, D. E. King, & V. B. Carson (Eds.), Handbook of religion and health (2nd ed., pp. 53–73). Oxford University Press.

- Krok, D. (2015). The role of meaning in life within the relations of religious coping and psychological well-being. Journal of Religion and Health, 54(6), 2292–2308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-014-9983-3

- Lakatos, C., & Martos, T. (2019). The role of religiosity in intimate relationships. European Journal of Mental Health, 14(2), 260–279. https://doi.org/10.5708/EJMH.14.2019.2.3

- Lun, V. M. C., & Bond, M. H. (2013). Examining the relation of religion and spirituality to subjective well-being across national cultures. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 5(4), 304–315. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033641

- Makin, P., Allen, R., Carson, J., Bush, S., & Merrifield, B. (2021). Light at the end of the bottle: Flourishing in people recovering from alcohol problems. Journal of Substance Use, 27(1), 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659891.2021.1905092

- McCullough, M. E., & Willoughby, B. L. (2009). Religion, self-regulation, and self-control: Associations, explanations, and implications. Psychological Bulletin, 135(1), 69–93. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014213

- Mitchell, L., & Romans, S. (2003). Spiritual beliefs in bipolar affective disorder: Their relevance for illness management. Journal of Affective Disorders, 75(3), 247–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00055-1

- Paulhus, D. L., & Vazire, S. (2007). The self-report method. In R. W. Robins, R. C. Fraley, & R. F. Krueger (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in personality psychology (pp. 224–239). The Guilford Press.

- Pew Research Centre. (2010). The global religious landscape. https://www.pewforum.org/2012/12/18/global-religious-landscape-exec/.

- Plante, T. G. (2010). The Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire: Assessing faith engagement in a brief and nondenominational manner. Religions, 1(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel1010003

- Plante, T. G., & Boccaccini, M. (1997). Reliability and validity of the Santa Clara Strength of Religious Faith Questionnaire. Pastoral Psychology, 45(6), 429–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310643

- Plante, T. G., Yancey, S., Sherman, A., & Guertin, M. (2000). The association between strength of religious faith and psychological functioning. Pastoral Psychology, 48(5), 405–412. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022040605141

- Sageman, S. (2004). Breaking through the despair: Spiritually oriented group therapy as a means of healing women with severe mental illness. Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis and Dynamic Psychiatry, 32(1), 125–141. https://doi.org/10.1521/jaap.32.1.125.28329

- Saroglou, V., Buxant, C., & Tilquin, J. (2008). Positive emotions as leading to religion and spirituality. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3(3), 165–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760801998737

- Seligman, M. E. (2011). Flourish: A visionary new understanding of happiness and well-being. Simon and Schuster.

- Seligman, M. E. P., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (Eds.) (2014). Positive psychology: An introduction. In M. E. P. Seligman & M. Csikszentmihalyi (Eds.), Flow and the foundations of positive psychology (pp. 279–298). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9088-8_18

- Shernoff, D. J., Csikszentmihalyi, M., Schneider, B., & Shernoff, E. S. (2014). Student engagement in high school classrooms from the perspective of flow theory. In D. J. Shernoff, M. Csikszentmihalyi, B. Schneider, & E. S. Shernoff (Eds.), Applications of flow in human development and education (pp. 475–494). Springer.

- Sibley, C. G., & Bulbulia, J. (2012). Faith after an earthquake: A longitudinal study of religion and perceived health before and after the 2011 Christchurch New Zealand earthquake. PLoS One, 7(12), e49648. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0049648

- Slauson-Blevins, K., & Johnson, K. M. (2016). Doing gender, doing surveys? Women's gatekeeping and men's non-participation in multi-actor reproductive surveys. Sociological Inquiry, 86(3), 427–449. https://doi.org/10.1111/soin.12122

- Stewart-Brown, S., Tennant, A., Tennant, R., Platt, S., Parkinson, J., & Weich, S. (2009). Internal construct validity of the Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS): A Rasch analysis using data from the Scottish health education population survey. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 7(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7525-7-15

- Stroope, S., Kent, B. V., Zhang, Y., Spiegelman, D., Kandula, N. R., Schachter, A. B., Kanaya, A., & Shields, A. E. (2022). Mental health and self-rated health among U.S. South Asians: The role of religious group involvement. Ethnicity & Health, 27(2), 388–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2019.1661358

- Sullivan, W. P. (1993). “It helps me to be a whole person”: The role of spirituality among the mentally challenged. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 16(3), 125–134. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0095669

- Sun, J., Kaufman, S. B., & Smillie, L. D. (2018). Unique associations between big five personality aspects and multiple dimensions of well-being. Journal of Personality, 86(2), 158–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12301

- Tateyama, M., Asai, M., Kamisada, M., Hashimoto, M., Bartels, M., & Heimann, H. (1993). Comparison of schizophrenic delusions between Japan and Germany. Psychopathology, 26(3-4), 151–158. https://doi.org/10.1159/000284815

- Van Cappellen, P., Toth-Gauthier, M., Saroglou, V., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2016). Religion and well-being: The mediating role of positive emotions. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(2), 485–505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9605-5

- VanderWeele, T. J. (2017). On the promotion of human flourishing. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(31), 8148–8156. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1702996114