ABSTRACT

Horizontal logistics collaboration (HLC) practices have gained much attention in recent years as innovative ways for companies to improve their performance. However, literature does not reveal which factors influence the success or failure of HLC, especially in agri-food supply chains (AFSCs) in developing countries. Therefore, this paper aims to investigate HLC in the context of AFSCs in Morocco as a case of a developing country. First, a literature review is performed to develop a conceptual model for HLC considering AFSCs characteristics. Then, in-depth case studies are conducted in Morocco to refine the conceptual model based on insights from real collaboration experiences. The results show that collaboration outcomes are influenced by operational collaborative activities through the mediation of relational elements. The operational collaborative activities are impacted by AFSCs’ characteristics, such as products specific handling conditions. Furthermore, the research shows that local cultural factors influence the development of trust in the relationship.

1. Introduction

Organisations continuously search for innovative ways to improve performance and gain a competitive advantage. In this regard, horizontal logistics collaboration (HLC) initiatives, such as collaborative transportation (Cruijssen Citation2006), collaborative procurement (Schotanus, Telgen, and de Boer Citation2010), and collaborative consolidation centres (Reaidy, Gunasekaran, and Spalanzani Citation2015), have gained much attention in the recent years. Nevertheless, despite the demonstrated benefits of collaborative practices, many firms struggle in their implementation and fail to reach the desired objectives (Nyaga, Whipple, and Lynch Citation2010). To date, collaboration has proven to be a difficult strategy to implement, mainly because key enabling and constraining factors are usually overlooked (Parsa et al. Citation2017).

Factors influencing collaboration are not only overlooked by collaborators but are also sensitive to the collaboration context (Zhang and Cao Citation2018). According to Saenz, Ubaghs, and Cuevas (Citation2015), adopting a ‘one-size fits all’ approach to collaboration may not lead to the best outcomes, as collaboration enabling and constraining factors have different influences in different contexts. Research conducted by Matopoulos et al. (Citation2007) and Rossi et al. (Citation2013) shows that context micro and macro factors can enable or hinder the development and implementation of collaboration, while Flynn, Huo, and Zhao (Citation2010) and Van der Vaart et al. (Citation2012) conclude that the performance of collaborative practices differs under various contexts. This raises the need for firms to better understand collaboration enabling and constraining factors in their own context to achieve the maximum benefits (Sousa and Voss Citation2008).

Literature offers several empirical studies, conducted in different industries, aiming at understanding which factors influence collaboration (Hudnurkar, Jakhar, and Rathod Citation2014). While the variety of considered industries provides ground for a generalisation of the results, AFSCs unique characteristics, such as specific transportation and storage requirements and limited shelf life (Van der Vorst, van Kooten, and Luning Citation2011), make it necessary to investigate collaboration enabling and constraining factors in this sector. AFSCs also differ from regular supply chains in the sense that, in addition to cost reduction, responsiveness, and sustainability, they also focus on food quality improvement and food waste reduction (Soysal et al. Citation2012). Also, existing empirical studies have only considered the case of developed countries (Hudnurkar, Jakhar, and Rathod Citation2014), raising questions regarding the applicability of the findings to developing countries which differ in terms of political, economic, socio-cultural, and demographic characteristics (Mersha Citation1997).

This paper has two main objectives. First, the research contributes to the body of knowledge on collaboration by identifying factors influencing HLC. This is done by adapting existing models for vertical collaboration to the case of horizontal collaboration and by taking into consideration the specific characteristics of AFSCs. Second, the research aims to explore, through in-depth case studies, the factors influencing HLC in AFSCs in Morocco. Morocco, as a study context, was chosen because of its political, economic, and socio-cultural similarities with its neighbouring countries, making the generalisation of the findings to at least the North African countries possible. The choice of Morocco is also motivated by the country’s commitment to improving the logistics sector by promoting flow massification through HLC (AMDL Citation2016). As such, the number of HLC experiences is expected to increase, which urges the identification of collaboration success factors in Morocco. In this regard, our research is relevant both from a theoretical and a practical perspective.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 discusses the theoretical foundations of this study, where scientific contributions relative to horizontal collaboration enablers and barriers are reviewed and propositions are formulated. In sections 3 and 4, the methodology and findings from the case studies are presented and discussed based on the formulated propositions. Finally, section 5 concludes the paper with a discussion of the research implications as well as its limitations.

2. Conceptual model and its propositions

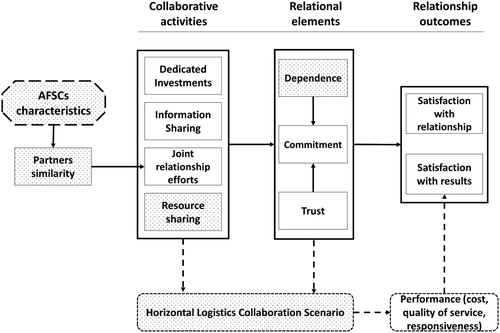

Although the literature on HLC enablers and barriers exists, the available contributions mostly focus on identifying which factors influence the collaboration success, without empirically investigating the relationship between them (Cruijssen Citation2006; Stephens Citation2006; Muhwezi Citation2010; Schotanus, Telgen, and de Boer Citation2010 and Walker et al. Citation2013). Investigating the relationship between collaboration enabling and constraining factors and their impact on collaboration outcomes is mainly found in the literature on vertical relationships. A first set of contributions investigates the link between collaborative activities (e.g. joint planning and information sharing) and relational enablers (e.g. trust and commitment) (Kwon and Suh Citation2004; Kwon and Suh Citation2005; Cai, Jun, and Yang Citation2010; Chen et al. Citation2011), while a second set links the collaboration activities to the collaboration outcomes through the mediation or moderation of relational enablers (Walter Citation2003; Vereecke and Muylle Citation2006; Nyaga et al., Citation2010; Cao and Zhang Citation2011). This paper builds on the accumulated knowledge of these vertical collaboration models in combination with the literature on horizontal collaboration to derive a conceptual model for HLC.

More specifically, this paper builds on the conceptual model developed by (Nyaga, Whipple, and Lynch Citation2010), which examines how collaboration outcomes are affected by (operational) collaboration activities through the mediation of relational elements. The choice of this model has been motivated by several elements. First, it combines both operational activities relative to the day-to-day execution of operations and relational mechanisms relative to the partners’ willingness to collaborate. Second, the model has been statistically validated which provides a strong basis for carrying further research. Third, their contribution has been widely cited and often used as a reference point to investigate supply chain collaboration. We first update the model with elements from HLC literature and specific AFSCs characteristics and then add the specific contextual factors of Morocco identified through the case studies.

illustrates our conceptual model where the full arrows represent the relationships we investigate through the case studies. On the operational level, partners’ similarity and sharing resources, have been identified as additional factors influencing the level of trust and commitment in the relationship. On the relational level, dependence originating from relationship-specific investments was depicted as having an influence on the members’ level of commitment. The combination of collaborative activities and the relational factors represents the HLC scenario, which similarly to the logistics scenario (Van der Vorst and Beulens Citation2002), can be defined as an internally consistent view of a possible instance of horizontal collaboration. The decisions made at the level of the HLC scenario result in the scenario’s operational performance, which impacts the partner’s satisfaction with the results. The dotted boxes represent additional constructs from the HLC and AFSC literature. We will now discuss each of the elements of the model in more detail.

2.1. Collaborative activities

Collaborative activities represent actions that are performed by the partners to prevent opportunism, encourage cooperative behaviour, and increase relational rents (Srinivasan and Brush Citation2006). They are considered as interweaving elements influencing the collaboration outcomes (Zhang and Cao Citation2018), which include relationship dedicated investments, sharing information, and joint relationship efforts (Nyaga, Whipple, and Lynch Citation2010).

2.1.1. Dedicated investments

Dedicated investments represent investments specifically made to reach the collaboration objectives (Cao and Zhang Citation2011), and are essential to capture collaborative benefits such as higher returns and competitive advantage (Whipple and Russell Citation2007). Investing in relationship-specific assets has been identified in vertical collaboration as having a positive impact on the trust partners exhibit towards each other, which leads to a greater commitment (Kwon and Suh Citation2004). Horizontal collaboration literature also highlights the importance of dedicated investments in promoting trust and commitment (Walker et al. Citation2013). They provide evidence of the partners’ engagement and create a dependence on the relationship to capture a return on the investments (Cruijssen Citation2006). Walker et al. (Citation2013) add that, besides investing in new assets, sharing existing complementary resources in HLC offers evidence that the partners care for the relationship and are willing to make sacrifices through sharing their own assets. Therefore, the following propositions are formulated:

P1. Investing in relationship-specific assets enhances trust and commitment in the relationship by providing evidence of the partner’s engagement and generating a dependence between the partners.

P2. Sharing complementary resources enhances trust and commitment by providing evidence of the partner’s engagement in the relationship.

2.1.2. Information sharing

Information sharing refers to the exchange of relevant information between the collaborating parties to plan and control supply chain operations (Simatupang and Sridharan Citation2005). It is defined by (Cao and Zhang Citation2011) as the act of timely sharing relevant, accurate, complete, and confidential information with the partners. Information exchange plays a key role in collaborative actions, contributing to the reduction of information asymmetries and transaction risks (Chen et al. Citation2011). The literature on information sharing emphasises its importance in achieving collaboration benefits. Kwon and Suh (Citation2005) state that information sharing improves the trust level between the partners by contributing to the reduction of behavioural uncertainty. Chen et al. (Citation2011) argue that information sharing is essential for trust-building, as it allows partners to understand each other’s processes, accurately plan collaborative activities, and develop conflict resolution mechanisms. Information sharing in HLC ensures synchronisation of collaborative activities and helps avoid opportunity costs relative to sub-optimization (Cruijssen Citation2006). It is important to note that efficient information sharing requires the implementation of e-collaboration tools, which success depends on technological, organisational and inter-organisational, and environmental contexts (Chan, Chong, and Zhou Citation2012). Based on the discussion above, the following proposition is formulated:

P3. Information sharing increases the trust and commitment in the relationship by allowing partners to better understand each other’s processes and jointly plan collaboration activities.

2.1.3. Joint relationship efforts

Research has also shown that the collaboration success relies on the partners’ joint efforts in planning and executing collaborative activities (Nyaga, Whipple, and Lynch Citation2010), including setting up common goals, decision synchronisation and joint planning, and joint performance measurement (Min et al. Citation2005). First, setting up common goals has been put forward by Cao and Zhang (Citation2011) as a performance improvement lever, consisting of switching from individual sub-optimizations to overall collaborative goals. Second, decision synchronisation and joint planning, which stand for developing mutual plans and synchronising operations, have also been identified as important parameters contributing to the collaboration success (Ramanathan and Gunasekaran Citation2014). Third, the joint measurement of performance has become a standard for collaboration, as it diminishes misunderstandings and helps to identify problems before they become constraining (Fawcett et al.,Citation2008). By allowing partners to co-align their operations and jointly plan the collaboration activities, joint relationship efforts are expected to enhance trust and commitment. Additionally, the literature on joint relationship efforts in HLC identifies incentives alignment as a key component improving trust and commitment (Walker et al. Citation2013; Schotanus, Telgen, and de Boer Citation2010). Given that a firm’s decision to enter a collaboration is always of a selfish nature, incentives should be aligned between the partners if they are to cooperate (Cruijssen Citation2006). It is important to note that companies only submit to joint relationship efforts as the power balance dictates (Benton and Maloni Citation2005). Firms with strong negotiation power have little or no reason to withhold exercising such power in seeking their own interest. As such, size similarity plays a key role in balancing the power in the relationship and ensuring all the partners are committed (Schotanus and Telgen Citation2007). This discussion leads to the following proposition:

P4. Joint relationship efforts improve the partners’ trust and commitment in the relationship through ensuring (i) the presence of common goals, (ii) the joint planning and execution of collaboration activities, (iii) the set-up of a performance measurement system, (iv) and the alignment of incentives.

2.1.4. Additional insights from the literature on horizontal collaboration

Horizontal logistics collaboration literature puts the light on additional operational enablers relative to partners’ processes and products similarity. Because HLC implies that partners complement each other through mutually undertaking logistics activities, process and product similarity become highly relevant (Cruijssen Citation2006). Process similarity is not only expected to improve joint planning and execution of activities by reducing the need to adapt, but it also reduces the risk that partners develop different perceptions about the value each one brings to the relationship, thus contributing in trust development (Schotanus, Telgen, and de Boer Citation2010). Product similarity, in terms of production, storage, and transportation requirements, also facilitates joint planning execution of logistics activities and reduces the need for companies to adjust to its partners’ products’ requirements (Pan Citation2010). The following proposition has been formulated regarding the partner’s similarity:

P5. Partners’ size, product and process similarity is expected to facilitate joint relationship efforts.

2.2. Relational elements

Discussing collaboration operational enablers has shed the light on several relational constructs originating from the Social Exchange Theory, which focuses on norms of reciprocity, i.e. what members receive versus what they give (Blau Citation1964). Given that moral hazards cannot be identified in advance, firms are unable to account for all the uncertainty in the relationship through a contractual agreement, which encourages the development of relational governance mechanisms (Bensaou and Anderson Citation1999) such as trust and commitment.

In the literature on vertical collaboration, trust is the most cited collaboration enabler (Cruijssen Citation2006). It refers to the extent to which a firm believes that its partners have the intentions and motives to fulfil their obligations (Nyaga, Whipple, and Lynch Citation2010). It is considered as a relational governance mechanism that promotes non-enforced willingness to collaborate, meaning that the partners perceive the benefits of the relationship (Schotanus, Telgen, and de Boer Citation2010). Empirical studies have shown a strong relationship between trust and sustained vertical relationships (Kwon and Suh Citation2004; Nyaga et al., 2011; Fynes, Voss, and de Búrca Citation2005), which in principle reflects the partners’ satisfaction with the collaboration. Trusting partners are also expected to show more commitment to the relationship, as they feel more confident to make the necessary efforts for the collaboration to succeed. Commitment occurs when the group members believe that the relationship is so important that it is worth making sure it endures (Morgan and Hunt Citation1994). It is believed to have a direct influence on the collaboration results, as relationship improvements are reached when partners are committed to it (Krause, Handfield, and Tyler Citation2007). Finally, dependence, which occurs when an organisation finds itself obliged to maintain a relationship with another organisation to achieve the desired goals, increases the partners’ commitment to the relationship (Geyskens et al. Citation1996). As such, the following propositions are formulated:

P6. Dependence enhances the partners’ commitment to the relationship by creating relational rents;

P7. Trust enhances the partners’ commitment to the relationship through the belief that each member will fulfil their obligations;

P8. Trust improves the outcomes of collaboration through promoting non-enforced willingness to collaborate;

P9. Commitment improves the outcomes of collaboration through the belief that it is so important that it is worth making sure it endures;

2.3. Relationship outcomes

Collaboration must generate value to its members that is perceived as sufficient to remain engaged in a risky and time-consuming relationship (Johnston et al. Citation2004). In other words, not only should the obtained gains outweigh the costs (Esper and Williams Citation2003), the collaboration should also generate a feeling of satisfaction among its members (Field and Meile Citation2008). Satisfaction is defined as a positive evaluation of a firm’s experience in collaborating with another firm (Dwyer, Schurr, and Oh Citation1987), and can be measured in terms of the economic results and the relational aspects of the relationship (Geyskens, Steenkamp, and Kumar Citation1999). Satisfaction with economic results is based on the operational improvements resulting from taking part in the collaboration, which is critical as it influences the firm’s willingness to commit to the relationship (Prahinski and Benton Citation2004). Satisfaction with the relationship is related to psychosocial aspects relative to the quality of the interaction between the partners, such as respect and willingness to exchange ideas.

In contrast with the model presented by (Nyaga, Whipple, and Lynch Citation2010), we decided to leave performance out of the relationship outcomes while keeping its relationship with the satisfaction with the results. This decision is motivated by the fact that we consider satisfaction, both with the relationship and the results, as higher-level constructs reflecting the partners’ overall evaluation of their collaboration (Dwyer, Schurr, and Oh Citation1987). Performance remains an operational and directly measurable variable which interpretation differs from one firm to the other depending on their expectations (Geyskens, Steenkamp, and Kumar Citation1999). For example, a 5% decrease in cost may be appreciated by one partner while resulting in poor satisfaction for the other partner(s). Thus, evaluating collaboration based on a measure of appreciation provides more valuable insights than on its absolute outcomes.

2.4. Implications for agri-food supply chains

To understand HLC in the context of the agri-food sector, it is important to analyse AFSCs specific characteristics and identify how they influence collaboration driving forces. AFSCs represent a set of activities allowing the production and distribution of food products in a ‘farm-to-fork’ sequence (Tsolakis et al. Citation2014). According to Van der Vorst, van Kooten, and Luning (Citation2011), the unique aspects of food products give AFSCs specific characteristics differentiating them from other supply chains, such as:

Short life cycle products;

High volumes and high product variety;

Long production throughput times and seasonality in farm production;

Variability of quality and quantity of supplied products and processing yields;

Specific requirements in transportation and storage conditions;

Expensive technical equipment focusing on capacity utilisation;

Need to comply with national and international regulations relative to food safety and environmental issues;

Need for traceability due to product safety responsibility

The distinctive characteristics of AFSCs influence the way partners interact with each other, raising concerns regarding products compatibility. Different products require different conditions to deliver the right quality to the consumers (Van der Vorst, Da Silva, and Trienekens Citation2007), thus defining what products can be transported or stored together. Food products are also living organisms that constantly interact with the surrounding environment (Van der Vorst, Da Silva, and Trienekens Citation2007), which emphasise the importance of product compatibility. Partners’ process and product compatibility become even more important considering the rigorous food safety regulations. Legislation targeting all stages in AFSCs define under which conditions food product should be produced, processed, and distributed (Akkerman, Farahani, and Grunow Citation2010). These constraints add an additional level of complexity to HLC, as product compatibility is not only relative to the products characteristics and interference risks, but also to legal sanitary and traceability obligations.

AFSCs are also known to rely on expensive specialised technical equipment (e.g. refrigerated trucks), for which high capacity utilisation is necessary (Van der Vorst, van Kooten, and Luning Citation2011). This characteristic, combined with the seasonal pattern of food products, represents a major challenge for AFSCs. Through adequate resources sharing and specific investments, HLC is expected to improve the capacity utilisation of the specialised equipment (Vanovermeire et al. Citation2014), provided product and processes similarities are ensured. In light of the discussion above, the following proposition is formulated:

P10. AFSCs characteristics increase the importance of partners similarity in the relationship;

3. Case studies from the agri-food sector in Morocco

3.1. Methodology

To understand how the identified collaboration enablers influence the design and operationalisation of HLC in the context of AFSCs in Morocco, two exploratory case studies were conducted. Using case studies as a research method was preferred since it allows a more descriptive and exploratory approach that provides insights into the researched phenomenon (Voss, Tsikriktsis, and Frohlich Citation2002). It also provides richness and first-hand observations in a natural setting, thus providing a foundation for generating novel theory and conducting further review.

The research uses focused/in-depth case studies to explore collaboration enablers and the links between them, following the five-stage research process presented by Stuart et al. (Citation2002). The first stage consists of defining the research question with the objective of contributing to theory development. In this research, we use the case studies to investigate the relationship between HLC operational activities and the satisfaction with the collaboration through the mediation of relational factors.

The second stage consists of developing a measurement instrument to capture data for future analysis. In this paper, a research instrument was developed containing questions relative to the different propositions. It includes thirteen semi-close ended questions, aiming to investigate the collaboration context, objectives, partners and outcomes, as well as to understand which enablers and barriers had an influence on the collaboration, i.e. the formulated propositions. The study protocol was developed in such a way that validity requirements are insured, namely construct, internal and external validity. Construct validity means that the measurements reflect the phenomenon they are supposed to. Internal validity means that the proposed relationships exist and are not caused by elements external to the research context, while external validity refers to the possible generalisation of the studied causal relationships.

To ensure construct validity, the triangulation method was used. Four interviews per case study were conducted for approximately 3 h each, which allowed the interviewees to freely speak about the development of the collaboration and the faced challenges while making sure the conversation uncovers all pertinent data. Internal validity was assessed by comparing patterns from both cases to check if the findings are similar in the context of Moroccan AFSCs. External validity was established through selecting cases in such a way that they differ as widely as possible, representing both competitive and non-competitive collaborative settings, cover different logistics activities, use different collaboration structures, present different collaboration intensities, and operate in different food supply chains.

The third stage of the process represents data gathering. As the interviewees were not comfortable recording the interviews, the interviewer took hand notes. To facilitate this process, the interviews were conducted in two phases. The objective of the first phase was to get an overview of the collaboration experience in terms of the involved firms and their objectives, the partner’s selection process, the concerned logistics activities, the structure the collaboration took, the various stages of the collaboration, and the collaboration outcomes. The second phase was directed towards identifying the factors that influenced the setup and operationalisation of the collaboration.

The fourth stage of the process is relative to data analysis. To extract patterns and simplify the descriptive information, the interviews were analysed using content analysis (Creswell Citation2014), following Schilling (Citation2006) five levels of qualitative content analysis. They consist of (i) transcribing tapes to raw data (not applicable to our case), (ii) condensing the data through paraphrasing original text, (iii) reducing the paraphrases into preliminary categories, (iv) refining the categories such that they reflect the research subjects, are exhaustive and mutually exclusive, (v) and finally analysing the results. The results’ analysis was conducted using concept mapping, i.e. a graphical representation of concepts and relationships (Schilling Citation2006). The research results were then reported in this research article, representing the fifth and final stage of the process.

3.2. Case #1 – a competitive collaboration in the mill industry

3.2.1. Collaboration context and objectives

The first case study covers the collaboration experience between two competitors operating in the mill industry in Morocco (called FIRM1 and FIRM2 to maintain anonymity). Products from the mill industry are considered as essential commodities ensuring food security in Morocco. As such, the state is highly present in the sector, ensuring an affordable flour price and protecting local production through customs fees. The first signs of the industry liberalisation by the state in the early 1990s motivated the birth of collaboration experiences, as companies were looking for ways to be more competitive in the upcoming open market and increase their profitability.

At that time, FIRM1 and FIRM2 were looking for a partner to better profit from the open market opportunities, through joint international procurement of wheat and storage. The two companies, who were present in limited regions of the country, also had the objective to extend the collaboration into the manufacturing activity to extend their presence to a larger geographical area and develop new products/technologies. Two parameters were taken into consideration during the identification of potential partners:

A high level of product and processes similarity to be able to collaborate on a wide range of activities (purchasing, storage, and manufacturing);

The existence of prior inter-personal relationships to mitigate the risk of opportunistic behaviour;

FIRM1 and FIRM2, which (i) shared comparable products and processes, (ii) were known for their work ethic, and (iii) maintained close personal and professional relationships, decided to start discussing the idea and eventually to collaborate.

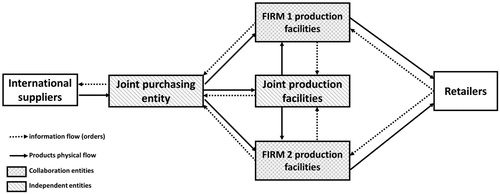

3.2.2. Collaboration structure

Because of the competitive nature of the collaboration, the partners were very concerned about the risk of information leakage, which motivated the adoption of a collaboration structure that guarantees information privacy. As such, they opted for the creation of separate entities that consolidate and synchronise the operations while keeping information safe.

Regarding the international purchasing activity, the partners decided to create a joint entity, which was legally registered as a wheat trading company belonging to both partners. The newly created entity, in which the partners have invested equal amounts of capital, sells the imported wheat to the two partners at a pre-determined price. This entity can also sell imported wheat to other industrials in the country to generate benefits which are then equally split between the collaboration parties. This configuration ensured that the information directly shared between FIRM1 and FIRM2 was limited to knowledge about their suppliers, the negotiated purchasing prices, and the suppliers’ performance in terms of quality and reliability. Information related to the quantities to purchase was shared depending on the inventory depletion rate. The jointly created entity provided weekly updates to the two partners about the inventory level.

A similar configuration was adopted for the manufacturing activity, where one joint production facility was created and a second one was purchased. To ensure information privacy, the production facilities acted as independent entities, processing orders for both partners at a pre-determined price. The facilities were also allowed to process orders for other clients to generate profit. Besides the planned production quantities, which were transmitted separately to the joint production facilities, partners freely exchanged information relative to the transformation processes, product quality insurance, and the maintenance of the manufacturing units. The information exchange frequency differed depending on the partner’s needs for production capacity. However, monthly meetings took place to evaluate the performance of the production units. is a representation of the physical and information flows in the collaboration configuration adopted by the partners.

3.2.3. Collaboration outcomes

The two partners started collaborating on procurement in 1994, and only evolved into manufacturing in 2005. The interviewees explain the 11 years difference by the need to (i) identify potential markets for the newly created entities, (ii) gather the necessary funds to finance the required investments, and (iii) evaluate the commitment of each other before investing in production facilities.

In terms of performance, collaborative procurement allowed both parties to make savings in purchasing and transportation costs. Given that the international prices of wheat are fixed by the stock exchange, the purchasing costs were reduced by 0.1 euro per quintal, which resulted in considerable aggregate yearly savings due to the high purchased quantities. In terms of transportation cost, the interviewees were not able to provide precise information because of the lack of records from the period before 1994. Nevertheless, the average quantity per shipment increased by 25,000 tons, which provided them with more negotiation power with transporters. Concerning the manufacturing activity, the newly created facilities allowed the partners to decrease production costs by 5%.

In 2010, both partners decided to end the collaboration for two reasons. First, the views of both companies regarding the way the collaboration diverged over time. The presence of several stakeholders at the level of FIRM1 with different visions regarding the firm’s future had an impact on the effectiveness of the decision-making process within the collaboration. Eventually, goal congruence and incentives alignment were lost, which precipitated the dissolution of the collaboration. Second, the partners were unable to reach the higher objectives they had set, which were the development of new products and technologies. The liberalisation of the sector did not fully occur, making the two partners realise that opportunities they initially targeted through the collaboration were not created. In this sense, FIRM1 and FIRM2 did not feel the added value of the collaboration anymore, which led to a feeling of dissatisfaction.

summarises the findings from the first case study for each factor presented in our model.

Table 1. Summary of the findings from the first case study.

3.3. Case # 2: international collaboration in food distribution

3.3.1. Collaboration context and objectives

The second case study covers the collaboration experience between the companies anonymously called FIRM3 and FIRM4, which are located respectively in Morocco and Turkey. FIRM3 is the market leader in fruit juice production and distribution in Morocco with a market share of 19%. FIRM4 is a large biscuits manufacturer and exporter located in Turkey which products are distributed in over 80 countries.

Because of the imbalance between volume and weight when it comes to liquids, FIRM3 faced low trucks capacity utilisation. In fact, while the truck utilisation in terms of weight reached 80%, less than 40% of its volume was used. The trucks utilisation was also impacted by the seasonality of demand for juice, which drops by 50% during winter. In this regard, the company was looking to improve its trucks capacity utilisation through collaborative transportation.

Five parameters were taken into consideration during the identification of potential partners, namely the potential partners should:

be companies in the agri-food sector to comply with food safety regulations;

offer products with a high volume to weight ratio;

offer products with an inverse seasonality in demand;

offer products with similar transportation and storage conditions to juice;

offer products with similar customers and distribution channels.

FIRM3 evaluated several potential products within the food industry, out of which 4 product families that verify at least one of the five conditions were shortlisted. These product families are bottled olive oil, canned products, cheese, and biscuits. Among these possibilities, FIRM3 opted for biscuits since it represented the most compatible products with juice. Biscuits/cakes are food products with a high volume to weight ratio. Their demand shows an inverse seasonal pattern to juice (high during the school year and low during summer). In addition, the two products required relatively similar temperature and humidity levels and could be handled using the existing logistics equipment. Finally, juice and biscuits are sold through the same distribution networks and are perceived by customers as complementary products in purchasing (e.g. parents buying both juice and biscuits for their kids in school).

After screening companies in the national biscuits’ industry, FIRM3 was not able to identify potential partners since the local biscuit industry is composed of large multinational corporations (e.g. Kraft Foods and Mondelez), which FIRM3 wanted to avoid because of power imbalances, and local manufacturers which were already running in full capacity. Therefore, FIRM3 shifted its attention to the international market for potential companies that would want their products to be distributed in Morocco. Keeping in mind that large multinational corporations should be avoided, the company was looking for partners of comparable size, which are preferably located in countries with whom Morocco has signed trade agreements. In this regard, Turkey appeared as an interesting country to look for partners.

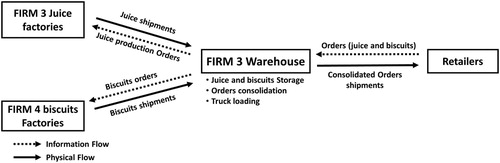

3.3.2. Collaboration structure

The legal framework regulating the distribution of foreign products on the national market requires international companies to have a representing entity in the country, which would import and distribute their products. Because FIRM4 does not have any local company importing its products, FIRM3 had to take over the role of the importer. In this configuration, FIRM3 would bear all the risks relative to marketing and selling the product on the local market. To compensate for the risk, both parties agreed that FIRM3 would be the exclusive representative of FIRM4 in Morocco and that 60% of the marketing costs would be covered by the Turkish company. The contract signed between the two partners stipulated the sales objectives, the participation of FIRM4 in the marketing costs, the payment conditions, and terms relative to the brand protection. Concerning the financial flows, FIRM3 pays FIRM4 for the shipped merchandise upon its receipt. It then proceeds to market the products and keeps all the profit that is made. The marketing costs are then communicated to FIRM4, which reimburses 60% to FIRM3. Through this participation in marketing costs, FIRM4 hopes to increase the demand for its products on the Moroccan market, which would make FIRM3 order more quantity. shows the configuration adopted by FIRM3 and FIRM4.

3.3.3. Collaboration outcomes

The fact that both partners did not maintain prior personal and professional relationships and were uncertain about the collaboration outcomes resulted at first in a low-intensity collaboration, characterised by a low volume of transactions (4 containers a month on average). Based on the experience from the first year, both parties developed more trust and commitment in the relationship, which resulted in a 100% increase in the volume of operations in the second year. Regular information exchange meetings regarding sales, projected demand, inventory levels, shelf life, and promotional activities were taking place. During the third year, FIRM3 reached its objective to increase its trucks utilisation to 100% in terms of allowed weight and 80% in terms of volume, which resulted in 15% decrease in the transportation cost. This situation was also beneficial for FIRM4, with approximately 5% increase in yearly revenues.

The rapid growth from a low to a high-intensity collaboration created several challenges for both parties. The variety of products imported by FIRM3 (66 different products), which differ in terms of demand pattern and variability, shelf life, and order lead time made the operational planning difficult for both parties. Therefore, the partners decided to scale down the number of imported references, focusing on products with interesting margin and high shelf life.

summarises the results from the second case study for each factor presented in our model.

Table 2. Summary of the findings from the second case study.

4. Findings and discussion of the results

The conducted case studies allow us to address the formulated propositions and complement them with further elements from the Moroccan context.

Proposition 1: The first case study provides indications supporting the influence of relationship-specific investments on the partners’ trust and commitment. The joint manufacturing entities required considerable investments in land, buildings, equipment, and human resources. These investments not only provided each party of the collaboration with more confidence regarding the positive intentions of the other party, which increased their trust, but also created a dependence in the relationship, as the investments could only become profitable in the case of joint usage of the production capacity. These two elements led to a larger commitment from the partners.

Proposition 2: Sharing complementary resources was identified as an enabling factor in both case studies. FIRM1 and FIRM2 mainly shared human capital in running the collaborative entities. According to the interviewees, this dedication created a positive atmosphere in the relationship, promoting trust and commitment. The second case study does not provide insights into the relationship between resource sharing and trust. Sharing resources resulted in positive performance (improving truck capacity utilisation), which was identified as having a positive influence on commitment in the relationship.

Proposition 3: Indications supporting the positive influence of information sharing on trust and commitment was identified in both case studies. Despite the competitive nature of the first case study, both parties freely exchanged information regarding their suppliers and their expertise in manufacturing processes. Exchanging expertise and know-how for the benefit of the group was considered by both partners as a trust development lever. In the second case study, the partners exchanged timely information regarding sales, projected demand, inventory levels and shelf life, and promotional activities. According to the interviewees, information sharing is believed to have positively influenced their trust levels, which resulted in more commitment. The case studies also highlight the positive influence of trust on information sharing. The increasing trust level in both cases resulted in a more frequent and exhaustive exchange of information.

Proposition 4: The case studies revealed that joint relationship efforts have improved the trust and commitment in the relationship. The interviewees from the first case study have considered setting up common goals as a pre-requisite to making any relationship-specific investments. According to them, defining a common ground increased their confidence that both partners are working towards the mutual benefit of the group, which increased their trust and commitment in the relationship. Similarly, the interviewees from the second case study also stressed the fact that agreeing on mutually beneficial common goals increased their commitment towards the relationship.

Regarding joint planning and execution of collaborative activities, the first case did not provide many insights, as the day to day planning of activities was performed by the jointly created entities. The interviewees from the second case identified joint planning as a factor that influenced their trust level and commitment in the relationship. Through mutual planning of biscuits manufacturing, importation, distribution, and promotional activities, the partners developed a clear idea about their engagement in the collaboration, making sure that all planned operations lead to the mutually agreed goals.

Finally, all interviewees have argued that the presence of a fair cost and benefits allocations mechanism enhanced trust and commitment between the partners. FIRM1 and FIRM2 agreed to invest equally in the collaboration and collect equal amounts from the benefits generated by the collaborative entities. Concerning the second case, the risks taken by FIRM3 was compensated by FIRM4 participation in the marketing costs.

Proposition 5: Size similarity was identified as a key factor influencing joint relationship efforts in both case studies. In the first case study, the partners claim that size similarity provided them with equal influence levels in the relationship, which meant that every decision regarding planning and executing the operational activities required both parties input. Similarly, FIRM3 and FIRM4 reported an increase in their commitment to joint relationship efforts when they perceived they had a fair share of input in deciding about the number of products to import to Morocco and what the financial contribution of each party would be. Partners in both cases agree that size similarity had ultimately a positive impact on their commitment.

Product and process similarity was also identified as a key facilitator of joint relationship efforts. Partners in the first case were both operating in the mill industry with equivalent products and processes, which facilitated the understanding of each other’s business, thus diminishing the need for adaptation. According to them, similarities in business and manufacturing processes made joint planning and execution more efficient. In the second case, product similarity was one of the main parameters considered by FIRM3 in choosing the collaboration partner. The fact that the partners’ products shared similar storage and transportation conditions and were sold through the same distribution network allowed for easier planning and execution of distribution.

Proposition 6: The dependence generated through investing in relationship-specific assets in the first case study contributed to the commitment of the partners to the relationship. According to the interviewees, the joint manufacturing facilities required considerable investments, and their production capacity was calculated based on the needs of both firms. As such, the partners were aware that they could only recoup their money via the joint usage of the facilities, which influenced their level of commitment.

Proposition 7: The conducted case studies show indications of the influence of trust on the commitment of the partners. Both case studies started as a low-intensity collaboration, due to the uncertainty regarding the partners’ behaviour and the profitability of the partnership. Based on the performance results from the first year, and the observed engagement of both partners in the relationship, the partners developed more trust towards each other. This situation had led to an increase in the collaboration intensity in both cases. The interviewees recognise the increase in the intensity as a proof of commitment from both parties.

Proposition 8 and 9: The case studies also show that building trust and commitment improves the outcomes of the collaboration. Both case studies started as low-intensity collaborations, which developed over time as the trust and commitment of the collaboration members increased. In the second case study, the trust and commitment developed during the first year led to a 100% increase in the volume of operations in the second year, which resulted in higher operational performances. Additionally, the interviewees stressed the fact that besides the operational improvement, the trust and commitment building process gradually resulted in a feeling of satisfaction with the relationship.

Proposition 10: Through the second case study, we could identify the effect of AFSCs characteristics on the collaborative activities. First, strict food safety regulations limited the choice of possible partners to companies operating in the agri-food sector. Second, the seasonality in juice consumption motivated the decision to choose a partner making products that have an inverse seasonality pattern to ensure high utilisation of the assets during different periods of the year. Finally, the specific handling conditions of food product motivated the choice of a partner making products that require similar transportation and storage conditions. These observations strengthen the position of the partner’s similarity as a key factor for HLC in AFSCs.

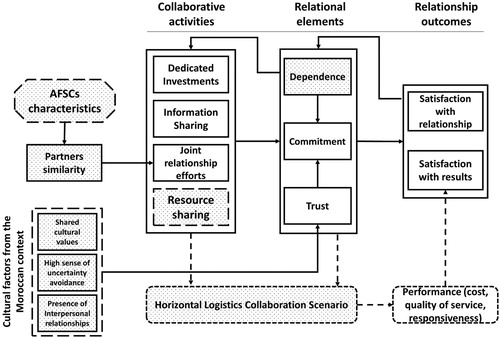

summarises the findings from the case studies. All the formulated propositions were supported in the first case. In the second case study, two propositions originating from vertical collaboration literature were not supported. Because the second case study was primarily based on resource sharing, neither the influence of dedicated investments on trust and commitment, nor the impact of dependence on commitment was identified.

Table 3. Propositions results.

The conducted cases have also revealed some country cultural factors which had an influence on the trust level in the relationship. First, sharing similar cultural values and the presence of interpersonal relationships were considered as relational control mechanisms that contributed to developing trust. Their presence provided a trust base to start the collaboration in case #1, while their absence in case #2 had a negative effect on trust, materialised by a low initial intensity of the collaboration. The influence of these two factors on trust has previously been discussed by Cai, Jun, and Yang (Citation2010) and Chen et al. (Citation2010) in the Chinese context, where Guanxi (i.e. a type of informal personal relationship) provides a powerful relational governance structure and plays an important role in building trust. Second, both cases reveal that the high sense of uncertainty avoidance, i.e. the extent to which firms try to avoid ambiguous situations (Zhang and Cao Citation2018), which prevailed between the partners also had a limiting effect on the collaboration intensity by means of low trust levels. This observation is in line with the work of Hwang and Lee (Citation2012), who highlight the moderating effect of uncertainty avoidance on trust development, specifically the trust in the partner’s ability and integrity. In strong uncertainty avoidance countries such as Morocco (Hofstede Citation2019), individuals feel threatened by uncertain situations, which negatively impacts trust.

Finally, it is important to note that HLC remains a dynamic system, in which collaborative activities affect the collaboration outcomes through the mediation of relational constructs and vice versa. The two cases start with a low-intensity collaboration, characterised by low levels of trust and commitment from the partners. However, given the satisfying results from the first-year experience, from both operational and relational perspectives, the partners developed more trust and commitment toward each other, leading to more intensive operational activities in terms of information sharing and joint relationship efforts. illustrates our conceptual model for HLC based on the results supporting the formulated propositions as well as the additional insights from the case studies. The dashed boxes represent additional elements to the initial model based on HLC and AFSCs characteristics, as well as the findings from the case studies. The arrows going back from collaboration outcomes to the relational elements, and then to the collaborative activities represent the feedback effect that the results have on the members’ willingness to collaborate.

5. Conclusion

In this paper, we develop a conceptual model for HLC considering the specific characteristics of AFSCs. The model links collaboration activities to collaboration outcomes, with the mediation of relational constructs. The contribution of our paper is threefold. First, we update the existing literature on vertical collaboration with specific operational enablers relative to horizontal collaboration (e.g. partners’ similarity, resource sharing). Second, we investigate the influence of AFSCs specific characteristics on the collaboration operational enablers. Finally, we explore the model in the context of AFSCs in Morocco through case studies to identify country-specific factors that influence HLC enablers.

On the operational side, the case studies revealed that AFSCs characteristics have a limiting effect on the collaboration. The strict food safety regulations and the products specific requirement limit the choice of possible partners to companies from the agri-food sector, whose products require similar handling conditions and present low interaction risks. The seasonality in food products demand and production also limits the potential partners to those offering products with inverse seasonality, which allows increasing the utilisation of the assets. Regarding assets utilisation, the required expensive technical equipment in AFSCs is considered as a factor increasing firms’ willingness to collaborate though mutually investing in or sharing technical resources.

On the relational level, the case studies show that trust is the main element limiting the collaboration intensity. Both cases started with a low-intensity collaboration, as companies were yet to develop trust towards each other. The encouraging initial results, in terms of operational performance and the absence of behavioural hazards, motivated the increase in intensity. The cases have also revealed three factors from the study context influencing trust, namely uncertainty avoidance, interpersonal relationships, and shared values.

As the research draws from only two in-depth cases from the same context, further research can apply the framework in other developing countries to test its replication. Also, a comparison between findings from developed and developing countries can be conducted to test the moderating role context characteristics have on collaboration enabling factors. Finally, survey-based empirical testing is required to quantify the relationships presented in the conceptual model.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Ismail Badraoui http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6332-8383

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Akkerman, R., P. Farahani, and M. Grunow. 2010. “Quality, Safety and Sustainability in Food Distribution: A Review of Quantitative Operations Management Approaches and Challenges.” Or Spectrum 32 (4): 863–904.

- AMDL. 2016. “Moroccan Green Logistics.” Agence Marocaine de Développement de la Logistique. Accessed 1 July 2017. http://www.amdl.gov.ma/amdl/publication/moroccan-green-logistics-ouvrage-de-reference/

- Bensaou, M., and E. Anderson. 1999. “Buyer-supplier Relations in Industrial Markets: When do Buyers Risk Making Idiosyncratic Investments?” Organization Science 10 (4): 460–481.

- Benton, W. C., and M. Maloni. 2005. “The Influence of Power Driven Buyer/Seller Relationships on Supply Chain Satisfaction.” Journal of Operations Management 23 (1): 1–22.

- Blau, P. M. 1964. Exchange and Power in Social Life. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Cai, S., M. Jun, and Z. Yang. 2010. “Implementing Supply Chain Information Integration in China: The Role of Institutional Forces and Trust.” Journal of Operations Management 28 (3): 257–268.

- Cao, M., and Q. Zhang. 2011. “Supply Chain Collaboration: Impact on Collaborative Advantage and Firm Performance.” Journal of Operations Management 29 (3): 163–180.

- Chan, F. T., A. Y. L. Chong, and L. Zhou. 2012. “An Empirical Investigation of Factors Affecting e-Collaboration Diffusion in SMEs.” International Journal of Production Economics 138 (2): 329–344.

- Chen, H., Y. Tian, A. E. Ellinger, and P. J. Daugherty. 2010. “Managing Logistics Outsourcing Relationships: An Empirical Investigation in China.” Journal of Business Logistics 31 (2): 279–299.

- Chen, J. V., D. C. Yen, T. M. Rajkumar, and N. A. Tomochko. 2011. “The Antecedent Factors on Trust and Commitment in Supply Chain Relationships.” Computer Standards & Interfaces 33 (3): 262–270.

- Creswell, J. 2014. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. Thousand Oaks, California. SAGE Publications.

- Cruijssen, F. C. A. M. 2006. “Horizontal cooperation in transport and logistics.” PhD diss., CentER, Tilburg University, 2006.

- Dwyer, F. R., P. H. Schurr, and S. Oh. 1987. “Developing Buyer-Seller Relationships.” Journal of Marketing 51 (2): 11–27.

- Esper, T. L., and L. R. Williams. 2003. “The Value of Collaborative Transportation Management (CTM): Its Relationship to CPFR and Information Technology.” Transportation Journal 42 (4): 55–65.

- Fawcett, S. E., G. M. Magnan, and M. W. McCarter. 2008. “A Three-Stage Implementation Model for Supply Chain Collaboration.” Journal of Business Logistics 29 (1): 93–112.

- Field, J. M., and L. C. Meile. 2008. “Supplier Relations and Supply Chain Performance in Financial Services Processes.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 28 (2): 185–206.

- Flynn, B. B., B. Huo, and X. Zhao. 2010. “The Impact of Supply Chain Integration on Performance: A Contingency and Configuration Approach.” Journal of Operations Management 28 (1): 58–71.

- Fynes, B., C. Voss, and S. de Búrca. 2005. “The Impact of Supply Chain Relationship Quality on Quality Performance.” International Journal of Production Economics 96 (3): 339–354.

- Geyskens, I., J. B. E. Steenkamp, and N. Kumar. 1999. “A Meta-Analysis of Satisfaction in Marketing Channel Relationships.” Journal of Marketing Research 36 (2): 223–238.

- Geyskens, I., J. B. E. Steenkamp, L. K. Scheer, and N. Kumar. 1996. “The Effects of Trust and Interdependence on Relationship Commitment: A Trans-Atlantic Study.” International Journal of Research in Marketing 13 (4): 303–317.

- Hofstede, Gert. 2019. “Morocco.” Hofstede Insights. Accessed 12 January 2019. https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country/morocco/

- Hudnurkar, M., S. Jakhar, and U. Rathod. 2014. “Factors Affecting Collaboration in Supply Chain: A Literature Review.” Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences 133: 189–202.

- Hwang, Y., and K. C. Lee. 2012. “Investigating the Moderating Role of Uncertainty Avoidance Cultural Values on Multidimensional Online Trust.” Information & Management 49 (3/4): 171–176.

- Johnston, D. A., D. M. McCutcheon, F. I. Stuart, and H. Kerwood. 2004. “Effects of Supplier Trust on Performance of Cooperative Supplier Relationships.” Journal of Operations Management 22 (1): 23–38.

- Krause, D. R., R. B. Handfield, and B. B. Tyler. 2007. “The Relationships Between Supplier Development, Commitment, Social Capital Accumulation and Performance Improvement.” Journal of Operations Management 25 (2): 528–545.

- Kwon, I. W. G., and T. Suh. 2004. “Factors Affecting the Level of Trust and Commitment in Supply Chain Relationships.” The Journal of Supply Chain Management 40 (1): 4–14.

- Kwon, I. W. G., and T. Suh. 2005. “Trust, Commitment and Relationships in Supply Chain Management: A Path Analysis.” Supply Chain Management: an International Journal 10 (1): 26–33.

- Matopoulos, A., M. Vlachopoulou, V. Manthou, and B. Manos. 2007. “A Conceptual Framework for Supply Chain Collaboration: Empirical Evidence From the Agri-Food Industry.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 12 (3): 177–186.

- Mersha, T. 1997. “TQM Implementation in LDCs: Driving and Restraining Forces.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 17 (2): 164–183.

- Min, S., A. S. Roath, P. J. Daugherty, S. E. Genchev, H. Chen, A. D. Arndt, and R. Glenn Richey. 2005. “Supply Chain Collaboration: What's Happening?” The International Journal of Logistics Management 16 (2): 237–256.

- Morgan, R. M., and S. D. Hunt. 1994. “The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing.” Journal of Marketing 58 (3): 20–38.

- Muhwezi, M. “Horizontal Purchasing Collaboration in Developing Countries: Behavioral Issues in Public United in Uganda.” PhD diss, University of Twente, 2010.

- Nyaga, G. N., J. M. Whipple, and D. F. Lynch. 2010. “Examining Supply Chain Relationships: Do Buyer and Supplier Perspectives on Collaborative Relationships Differ?” Journal of Operations Management 28 (2): 101–114.

- Pan, S. “Contribution à la définition et à l'évaluation de la mutualisation de chaînes logistiques pour réduire les émissions de CO2 du transport: application au cas de la grande distribution.” PhD diss, École Nationale Supérieure des Mines de Paris, 2010.

- Parsa, P., M. D. Rossetti, S. Zhang, and E. A. Pohl. 2017. “Quantifying the Benefits of Continuous Replenishment Program for Partner Evaluation.” International Journal of Production Economics 187: 229–245.

- Prahinski, C., and W. C. Benton. 2004. “Supplier Evaluations: Communication Strategies to Improve Supplier Performance.” Journal of Operations Management 22 (1): 39–62.

- Ramanathan, U., and A. Gunasekaran. 2014. “Supply Chain Collaboration: Impact of Success in Long-Term Partnerships.” International Journal of Production Economics 147: 252–259.

- Reaidy, P. J., A. Gunasekaran, and A. Spalanzani. 2015. “Bottom-up Approach Based on Internet of Things for Order Fulfillment in a Collaborative Warehousing Environment.” International Journal of Production Economics 159: 29–40.

- Rossi, S., C. Colicchia, A. Cozzolino, and M. Christopher. 2013. “The Logistics Service Providers in eco-Efficiency Innovation: An Empirical Study.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 18 (6): 583–603.

- Saenz, M. J., E. Ubaghs, and A. I. Cuevas. 2015. Enabling Horizontal Collaboration Through Continuous Relational Learning. New York: Springer International Publishing.

- Schilling, J. 2006. “On the Pragmatics of Qualitative Assessment: Designing the Process for Content Analysis.” European Journal of Psychological Assessment 22 (1): 28–37.

- Schotanus, F., and J. Telgen. 2007. “Developing a Typology of Organizational Forms of Cooperative Purchasing.” Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 13 (1): 53–68.

- Schotanus, F., J. Telgen, and L. de Boer. 2010. “Critical Success Factors for Managing Purchasing Groups.” Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 16 (1): 51–60.

- Simatupang, T. M., and R. Sridharan. 2005. “The Collaboration Index: A Measure for Supply Chain Collaboration.” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 35 (1): 44–62.

- Sousa, R., and C. A. Voss. 2008. “Contingency Research in Operations Management Practices.” Journal of Operations Management 26 (6): 697–713.

- Soysal, M., J. M. Bloemhof-Ruwaard, M. P. Meuwissen, and J. G. van der Vorst. 2012. “A Review on Quantitative Models for Sustainable Food Logistics Management.” International Journal on Food System Dynamics 3 (2): 136–155.

- Srinivasan, R., and T. H. Brush. 2006. “Supplier Performance in Vertical Alliances: The Effects of Self-Enforcing Agreements and Enforceable Contracts.” Organization Science 17 (4): 436–452.

- Stephens, C. 2006. “Enablers and Inhibitors to Horizontal Collaboration between Competitors: An Investigation in UK Retail Supply Chains.” PhD diss, Cranfield University, 2006.

- Stuart, I., D. McCutcheon, R. Handfield, R. McLachlin, and D. Samson. 2002. “Effective Case Research in Operations Management: A Process Perspective.” Journal of Operations Management 20 (5): 419–433.

- Tsolakis, N. K., C. A. Keramydas, A. K. Toka, D. A. Aidonis, and E. T. Iakovou. 2014. “Agrifood Supply Chain Management: A Comprehensive Hierarchical Decision-Making Framework and a Critical Taxonomy.” Biosystems Engineering 120: 47–64.

- Van der Vaart, T., D. Pieter van Donk, C. Gimenez, and V. Sierra. 2012. “Modelling the Integration-Performance Relationship: Collaborative Practices, Enablers and Contextual Factors.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 32 (9): 1043–1074.

- Van der Vorst, J. G., and A. J. Beulens. 2002. “Identifying Sources of Uncertainty to Generate Supply Chain Redesign Strategies.” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 32 (6): 409–430.

- Van der Vorst, J. G., C. A. Da Silva, and J. H. Trienekens. 2007. “Agro-Industrial Supply Chain Management: Concepts and Applications.” Food and Agriculture Organization. Accessed 22 July 2017. http://www.fao.org/3/a-a1369e.pdf

- Van der Vorst, J. G., O. van Kooten, and P. A. Luning. 2011. “Towards a Diagnostic Instrument to Identify Improvement Opportunities for Quality Controlled Logistics in Agrifood Supply Chain Networks.” International Journal on Food System Dynamics 2 (1): 94–105.

- Vanovermeire, C., K. Sörensen, A. Van Breedam, B. Vannieuwenhuyse, and S. Verstrepen. 2014. “Horizontal Logistics Collaboration: Decreasing Costs Through Flexibility and an Adequate Cost Allocation Strategy.” International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications 17 (4): 339–355.

- Vereecke, A., and S. Muylle. 2006. “Performance Improvement Through Supply Chain Collaboration in Europe.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 26 (11): 1176–1198.

- Voss, C., N. Tsikriktsis, and M. Frohlich. 2002. “Case Research in Operations Management.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 22 (2): 195–219.

- Walker, H., F. Schotanus, E. Bakker, and C. Harland. 2013. “Collaborative Procurement: A Relational View of Buyer–Buyer Relationships.” Public Administration Review 73 (4): 588–598.

- Walter, A. 2003. “Relationship-specific Factors Influencing Supplier Involvement in Customer new Product Development.” Journal of Business Research 56 (9): 721–733.

- Whipple, J. M., and D. Russell. 2007. “Building Supply Chain Collaboration: A Typology of Collaborative Approaches.” The International Journal of Logistics Management 18 (2): 174–196.

- Zhang, Q., and M. Cao. 2018. “Exploring Antecedents of Supply Chain Collaboration: Effects of Culture and Interorganizational System Appropriation.” International Journal of Production Economics 195: 146–157.