ABSTRACT

Supply chain resilience and reconfiguration are emerging disciplines that allow supply chains to recover from events and quickly return to normal or equilibrium levels of operations. This paper aims to provide a systematic mapping review to classify studies on supply chain resilience and reconfiguration. In total, 286 studies published between January 2009 and May 2019 were identified, of which 94 were selected for review. The analysis provided a number of thematic areas: descriptive view of the selected articles; geographical areas; type of research; research methods; and supply chain resilience enablers and reconfiguration characteristics. The major significance of this study is to provide an assessment of the state of existing knowledge on supply chain resilience and reconfiguration and to suggest future research directions. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first systematic mapping study conducted on supply chain resilience and reconfiguration literature.

1. Introduction

Supply chain disruptions can result in lost productivity, rise in customer complaints, higher lead-time and loss of shareholder’s value (Bhatia et al., Citation2013; Alcantara and Riglietti, Citation2015). Such disruptions poses risk to the supply chains Kinra et al., Citation2020; Hosseini et al., Citation2019; Ivanov et al., Citation2018) and need to be addressed. Apart from conventional disruptions of capacity constraints, supply variability, quality problems (Saenz and Revilla, Citation2014), managers in the current scenarios; deal with unprecedented disruptions like pandemic, strikes, natural disasters, and accidents (Ivanov, Citation2018). Adapting to these challenges results in unstable, unpredictable and complex supply chains (Kamalahmahdi and Parast, Citation2016).

When problems occur within a supply chain, managers have to make difficult decisions about supply chain resilience and reconfiguration. Companies will usually have an agreed policy in place to recover from issues, either by mitigating risks or thorough supply chain resilience. It is usually considered pivotal to maintain normal supply chain operations, so that companies may decide to reconfigure supply chains. Resilience in supply chains can also be a way to address and cope with supply chain risks. This has, therefore, become an important area of research, as well as a practical issue in supply chain risk management (Ponomarov and Holcomb, Citation2009; Hohenstein et al., Citation2015; Datta, Citation2017). It has already been delineated by researchers that firms need to take steps that enable their supply chains to anticipate, adapt, respond, and recover quickly from disruptions (Ponomarov and Holcomb, Citation2009; Jüttner and Maklan, Citation2011).

It is assumed that supply chain resilience should help organisations to alleviate problems. These problems may include organisational risk, which sometimes causes a loss of labour through strikes and production uncertainties (e.g. process quality), IT system uncertainties (e.g. machine breakdown) (Jüttner et al., Citation2003), network risk, because of difficulties created by supply risk, demand risk, and information risk (Christopher and Peck, Citation2004; Wagner and Bode, Citation2008); and environmental risk, which may affect physical, social, political, legal, operational, economic, and cognitive environments (Bogataj and Bogataj, Citation2007). Generally, the environmental risk from unpredictable and rare events such as natural disasters, bankruptcy, fire accidents, transportation, and terrorism, arises from the supply chain environment interaction, and are often quite damaging (Chopra and Sodhi, Citation2004; Jüttner et al., Citation2003; Tang, Citation2006; Trkman and McCormack, Citation2009). Recent studies also discussed cyber supply chain risk management (CSCRM) which is emerging as a new construct (Colicchia et al., Citation2019). Dealing with the increased complexity of the supply chain is the main challenge in the process of CSCRM (Bode and Wagner, Citation2015). Such type of risky events has a knockdown impact on the entire supply chain (Williams, Citation2017). Hence, this type of risk needs to be addressed to face the challenges in order to develop an enhanced approach for cyber resilience in supply chains (Colicchia et al., Citation2019).

Resilience enablers are designed to alleviate some of these challenges. They, therefore, need to include features such as the ability to anticipate, monitor, respond, and learn (Blackhurst et al., Citation2011; Jüttner and Maklan, Citation2011; Ambulkar et al., Citation2015; Ali et al., 2017). However, there is insufficient information about which enablers have these functions or are suitable for use in an uncertain business environment. A few studies have examined some of the existing enablers, such as Soni et al. (Citation2014), who provided a set of supply chain resilience enablers, classified on the basis of resilience and scope of improvement.

Supply chain reconfiguration can also help organisations to return to equilibrium (Holmström et al., Citation2017; Wilhelm et al., Citation2013). However, it is unclear how firms reconfigure their supply chains in practice. The ability to manage and reconfigure the resources according to a volatile environment is critical to the survival of a firm (Davis et al., Citation2009). Disruptions in the supply chain are characterised by uncertainty where the whole supply chain gets effected (Bode et al., Citation2011). This in turn creates ambiguity in the system which requires proper attention in order to recover the supply chain. The extant literature suggests that there are factors which are responsible for reconfiguring the supply chain by new product development or entering into new markets with existing product or managing environmental shocks (Sirmon et al., Citation2007). Dynamic response to market changes has also been envisaged as one of the tools to adapt (Helfat et al., Citation2007; Marsh and Stock, Citation2006). Blackhurst et al. (Citation2011) stated that in dynamic environment, firms focusing on reconfiguration possess the key to develop capabilities against disruptions in the environment.

Ambulkar et al., (Citation2015) argued that to become resilient, a firm’s ability to reconfigure resources plays a major role in times of supply chain disruptions. Firms having experience dealing with disruptions take proactive decisions in reconfiguring their supply chains (Bode et al., Citation2011), which requires continuous scanning of the environment (Ramaswami et al., Citation2009). Reconfiguration also includes improving the coordination among supply chain actors (Chandra and Grabis, Citation2009). Cooperation, defined involvement, real-time information sharing and long-term planning also helps in building resilience in the supply chain. Such reconfigurations lead to efficient collaborations in the whole supply chain (Chandra and Grabis, Citation2009).

The importance of supply chain resilience is enormous, but to the best of the authors knowledge, the literature fails to connect the link between disruptions and the practices which helps improves the performance of the supply chain. Studies connecting supply chain resilience and reconfiguration are few (Ambulkar et al., Citation2015). Many authors have cited the importance of redesigning the supply chain network in order to attain resilient supply chains (Sheffi and Rice, Citation2005; Kleindorfer and Saad, Citation2005; Tang, Citation2006; Petit et al., Citation2010; Ponis and Koronis, Citation2012; Lee and Rha, Citation2016; Kunz et al., Citation2014).

The major aim of this paper is to synthesise the existing literature, focusing on reconfiguration as one of the key aspects of supply chain resilience. This has been done by analysing and systematically reviewing articles, which are published in journals in the last 10 years. According to Ali and Gölgeci (Citation2019), the majority of articles focusing on redesigning the resilient supply chain network are published in the last decade. In addition, one of the major disruptions can be cited in 2009, where the economic recession has affected business worldwide, lest supply chain networks. Recent pandemic has also increased the importance of supply chain resilience and reconfiguration (Ivanov, Citation2020). Pandemic is ambiguous with respect to geography and time, hence poses a greater threat for businesses. Therefore, the need to consolidate supply chain risk, resilience, and reconfiguration research and create a coherent knowledge framework is very important.

To date, the present study in itself is the first attempt to use a systematic review mapping methodology in supply chain resilience and reconfiguration. The study deals mainly with understanding the enablers of supply chain resilience and the characteristics of supply chain reconfiguration, linking them with other issues of supply chain resilience and reconfiguration such as research sources, research type, geographical area, and methodology. It aggregates the results of selected studies published between 2009 and 2019, using systematic mapping review procedures. Its primary goal was to investigate research on new or modified supply chain resilience and reconfiguration procedures. It aims to provide a classification of supply chain resilience and reconfiguration studies with respect to research source and type, geographical area, research methodologies, supply chain resilience enablers, and supply chain reconfiguration characteristics.

Section 2 of this paper outlines the systematic mapping review methodology. Section 3 reports and discusses the findings of the mapping. Section 4 provides the theoretical, managerial and social implications of this study along with unique contributions. Section 5 provides conclusions, future research avenues and discusses the limitations of this review.

2. Methodology

Systematic mapping reviews (also called scoping reviews) have their origins in the fields of health and engineering and have been developed through the Cochrane Collaboration (Sheldon and Chalmers, Citation1994; Hemsly-Brown and Oplatka, Citation2015; Petersen et al., Citation2015). Systematic mapping reviews aim to map the key concepts underpinning a research area by categorising existing literature on a particular topic then identifying future avenues for work (Arksey and O’Malley, Citation2005; Peters et al., Citation2015). They, therefore, focus on the structure of the research area rather than gathering and synthesising evidence like systematic literature reviews (Petersen et al., Citation2015). Some features of this approach have been implemented in the field of social sciences (Tranfield et al., Citation2003) and human resource management (Arias et al., Citation2018).

Any systematic review has several potential advantages in the literature. It can help academicians and practitioners to understand whether an effect is constant across studies or not while giving new motions for future research. It also helps to study sample characteristics and its implications on the phenomenon being studied (Davis et al., Citation2014). This phenomenon is gaining popularity in the field of operations research but still, a lot needs to be done in order to take advantage of this technique (Synder et al., Citation2016). Simply put, there is a dearth of studies having systematic mapping of studies on resilience and reconfiguration in supply chains.

2.1. Systematic mapping review process

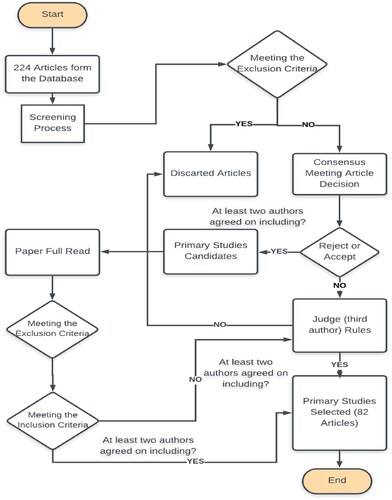

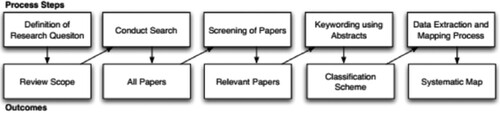

This study carried out a systematic mapping review using the process proposed by Petersen et al. (Citation2008) (see ).

Figure 1. Systematic mapping study process (adapted from Petersen et al., Citation2008).

The study aimed to explore the literature on supply chain resilience and reconfiguration. It, therefore, identified six mapping questions (MQs) and the main motivation behind each (see ). The MQs followed the procedure introduced by Kitchenham and Charters (Citation2007), using a structure of the population, intervention, comparison, outcome, and context (PICOC). shows this structure and the broad areas covered. This paper did not compare any interventions, because the studies follow different methodological approaches. Moreover, while performing systematic analysis, it is difficult to get insights in a comprehensive manner about studies having wide methodologies (Tranfield et al., Citation2003). Although the systematic review was majorly used in medical sciences, but the guidelines for social sciences have also been developed and recommended (Davis et al., Citation2014; Palmatier et al., Citation2018). In the areas, where methodological approaches are different, qualitative systematic reviews are analysed, and thus mapping relevant questions become relevant (Grant and Booth, Citation2009; Palmatier et al., Citation2018). The mapping questions were considered against the results of selected studies that aimed to address or examine supply chain resilience and reconfiguration.

Table 1. Systematic mapping review questions.

Table 2. Structure of questions for systemic mapping review.

Once the mapping questions are identified, it is important to define the review strategy. The review strategy should be designed in stages in order to provide systematic and explicit method, so that the coverage of the research area is comprehensive (Peterson et al., Citation2015). The next section discusses the steps undertaken in this study:

Search strategy

Screening

Extraction and Synthesis

Reporting

2.2. Search strategy

It is important to identify and search for all possible sources of information that is addressing the research question directly. For that, keywords play a major role and should be identified in a critical manner, because search strings are developed utilising them by applying them to academic databases. Other related literature reviews were also taken up for keywords and knowledge source (Kamalahmadi and Parast, Citation2016; Ponis and Koronis, Citation2012).

Based on prior articles and experts’ opinion, keywords on the subject were identified using a form of brainstorming. Boolean connectors (i.e. AND, OR, and NOT) were used in the search strings for the selected. The titles and abstracts containing these terms among peer reviewed, scholarly journals in the SCOPUS and Web of Science (WoS) databases were searched, which resulted in the identification of 286 titles. Although all the titles in WoS are invariably indexed in SCOPUS, WoS provided an added layer of quality criterion using impact factor of the journals.

Accurate selection of supply chain resilience and reconfiguration studies requires transparent search and analysis processes.

2.2.1. Search terms

The search terms were developed in three steps:

The main terms associated with the mapping questions were identified, including supply chain’, ‘supply chain resilience', ‘resilience', ‘enablers', ‘approaches', ‘capabilities', ‘supply chain reconfiguration', ‘reconfiguration', and ‘characteristics'.

Alternative spellings and synonyms of the main terms were identified, including ‘resilient', ‘resiliency', ‘enabler', ‘capability', ‘component', ‘SCRES', and ‘reconfigure'

The Boolean Operators ‘OR', ‘AND' and ‘NOT' were used to join synonymous terms and exclude any non-related terms to retrieve relevant records. Example searches included (‘supply chain' AND ‘resilience'), (‘supply chain resilience' OR ‘resilience'), (‘supply chain resilience' NOT ‘organisational resilience'), (‘supply chain' AND ‘resilience' OR ‘resilient' OR ‘resiliency’), (‘supply chain resilience' AND ‘enabler' OR ‘component' OR ‘capability'), and (‘supply chain' AND ‘resilience' OR ‘supply chain resilience' NOT ‘organisational resilience'), (‘supply chain' AND ‘reconfiguration'), (‘supply chain reconfiguration' OR ‘reconfigure'), (‘supply chain reconfiguration' NOT ‘redesign'), (‘supply chain' AND ‘reconfiguration' OR ‘reconfigure'), (‘supply chain reconfiguration' AND ‘characteristics' OR ‘attributes’ OR ‘component'), and (‘supply chain' AND ‘reconfiguration' OR ‘supply chain reconfiguration' NOT ‘organisational redesign’).

2.2.2. Resources

An automatic search was performed using the pre-constructed search terms in SCOPUS and WoS:

These databases were chosen because they contained a number of known papers on the supply chain resilience and supply chain reconfiguration (Ali et al., 2017; Datta, Citation2017; Hohenstein et al., Citation2015). Both SCOPUS and WoS are widely used in systematic analysis studies (Zhu and Liu, Citation2020). Google Scholar was excluded to avoid any irrelevant studies. The search was limited to articles published between 2009 and 2019. Each database was searched separately. The search was based on keywords, abstract and title. To ensure the search quality and avoid missing any relevant papers, a two-stage process was used.

Stage 1. Initial Search

A primary search was conducted in the two electronic databases using the identified search terms. The papers found were grouped together to form a set of candidate papers and any duplicate papers were removed.

Stage 2. Secondary Search

The candidate papers were checked against the inclusion and exclusion criteria and their references lists reviewed to identify any further papers relevant to supply chain resilience.

2.3. Screening

This step was designed to identify studies that matched the research questions, based on their title, abstract, and keywords. Candidate studies identified in the initial search step were evaluated by two researchers using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The third and fourth researchers were involved when required, for example, where there was no consensus on whether to include or exclude an article. The systematic mapping review process is shown in detail in . The inclusion and exclusion criteria are mentioned in .

Table 3. Inclusion and Exclusion criteria.

This stage provided a final set of 94 articles that met the study inclusion and exclusion criteria. The final stage was to read all the selected articles in full (see ).

Table 4. Search results.

2.4. Data Extraction

The primary studies were scanned to extract the information required for the systematic mapping review. This included author names, year, title, aim, type of study, methodology, resilience enablers, reconfiguration characteristics, and geographical region. Once the data had been extracted from the selected studies, they were synthesised and tabulated to aggregate the evidence to answer the mapping questions. The first author’s extraction was reviewed by the second author (Petersen et al., Citation2008), by retracting the information in the extraction form and checking its accuracy. The third and fourth authors also checked the accuracy of the extracted data ().

Table 5. Data Extraction.

3. Results

This section describes the results of the systematic mapping review of supply chain resilience and reconfiguration, based on 94 selected articles.

3.1. Descriptions of the selected articles (MQ1)

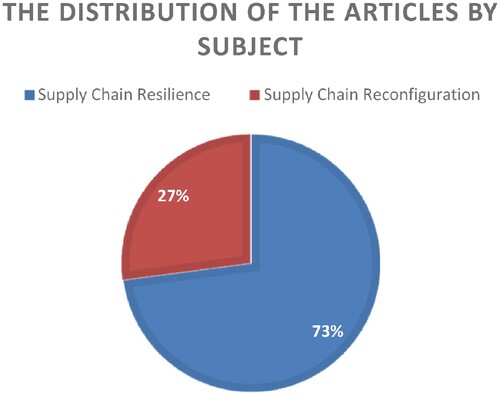

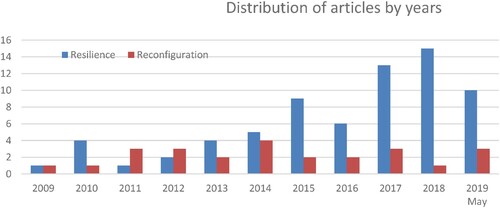

shows the distribution of the articles by subject. The largest number was on supply chain resilience (69 articles, 73%), followed by supply chain reconfiguration (25 articles, 27%). shows the trends in the publication of these articles over the 10 years from 2009 to 2019. The number of supply chain resilience and reconfiguration studies increased during these 10 years. Over the last few years, the rate of increase in supply chain resilience and reconfiguration studies has accelerated, as firms try to build reactive and proactive strategies to manage pressure from environmental uncertainty, and reduce the damage from supply chain disruptions.

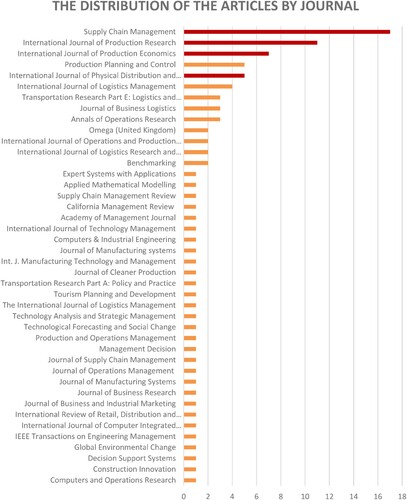

shows the distribution of articles by journal of publication. The most popular journals were Supply Chain Management: International Journal (17 articles), International Journal of Production Research (11 articles), International Journal of Production Economics (seven articles), and International Journal of Physical Distribution and Logistics Management (five articles). It is reasonable that Supply Chain Management: International Journal contained the most articles because this journal has a stated aim to push the boundaries of supply chain research and practices.

3.2. Geographical areas (MQ2)

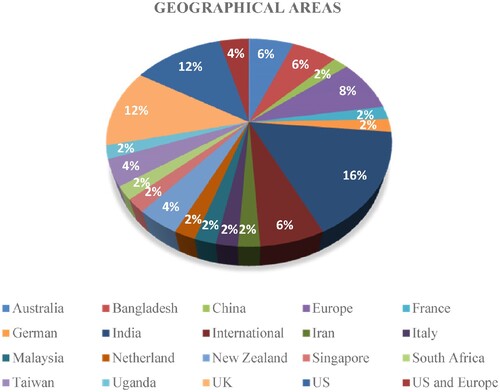

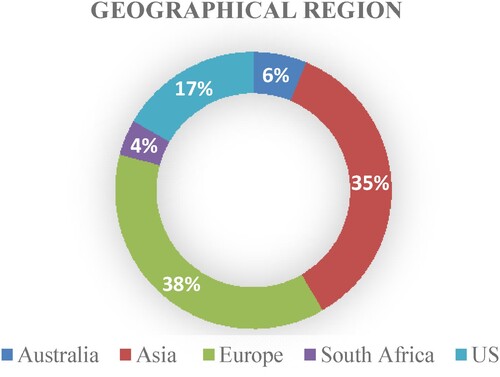

Studies on supply chain resilience and reconfiguration had been carried out in 19 countries (see ) across 5 main geographical areas (). The majority of studies took place in either Europe (38%) or Asia (36%). The US, Australia, and South Africa had seen 17%, 6%, and 4% of studies. However, 32 of the reviewed articles did not specify the location.

3.3. Type of research (MQ3)

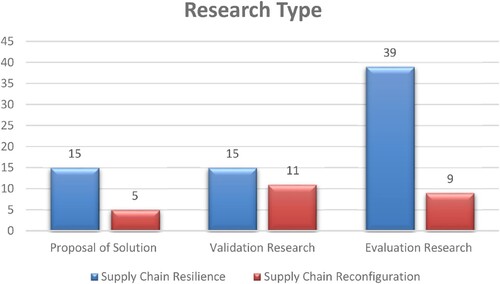

Petersen et al. (Citation2015) classified papers into three types: proposal of solution, validation research, and evaluation research. outlines the three types of research and provides a description of each.

Table 6. Classification of research type (Petersen et al., Citation2015).

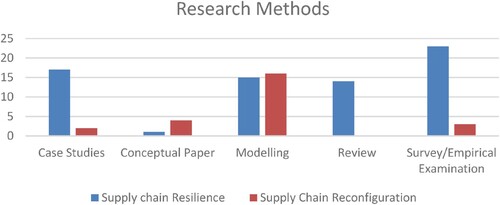

shows the main categories of research method in the selected papers, divided into case study, literature review, conceptual paper, modelling, and research paper. Studies pertaining to supply chain resilience mostly focused on survey or empirical examination (23, 33%) followed by case studies (17, 25%), literature reviews and modelling share equal weightage in these 10 years (14, 20% each). Conceptual papers were least published (1, 1%), it may be because the concept of resilience is already studied well in the past. As far as supply chain reconfiguration studies are concerned, papers on model development are developed mostly in the past decade (16, 64%) but there seems to have a dearth of studies on developing conceptual (4, 16%), Survey (3, 12%), case studies (2, 8%), and literature review (0, 0%). In total, 32% used a mathematical modelling approach and is the predominant research method, and 28% used survey methodology. Almost 64% of supply chain reconfiguration studies, however, used mathematical models, including graph-based cost models, two-stage stochastic models, and agent-based simulation and decision tree learning. This compared to just 32% of the supply chain resilience studies. A total of 19 studies (20%) used case studies, of which 17 examined supply chain resilience enablers and 2 used the characteristics of supply chain reconfiguration. Only 15% of studies were review papers and none of these covers supply chain reconfiguration. It is perhaps not surprising, because this is a very new area of research. Future review papers are needed on supply chain reconfiguration to provide insights into the current state of knowledge on supply chain reconfiguration processes and characteristics.

More than half of the selected papers were considered evaluation research (Petersen et al., Citation2015) (see ). This suggests that researchers were trying to validate supply chain resilience and reconfiguration approaches by using case studies and quantitative approaches in different geographical areas. The other 49% were divided into 28% validation research and 21% proposals of solutions.

Figure 9. Research type (Petersen et al., Citation2008).

3.5. Definitions

3.5.1. Supply chain resilience

Supply chain resilience is a relatively new phenomenon in the supply chain management domain, designed to help organisations to move away from traditional approaches to mitigating risk and managing production strategies (Ali et al., 2017). The main application of supply chain resilience is to deal with the complexities of global supply chains (Pettit et al., Citation2013). There are several definitions of supply chain resilience. The most cited definition was set out by Christopher and Peck (Citation2004) as ‘the ability of a system to return to its original state, within an acceptable period of time, after being disturbed' (Brandon-Jones et al., Citation2014; Cardoso et al., Citation2015; Chowdhury and Quaddus, Citation2016; Cheng and Lu, Citation2017). There are a number of significant similarities and differences to supply chain resilience definitions (see ). The majority of studies commented only on supply chain resilience as a way to recover from unexpected disruptions (Ponomarov and Holcomb, Citation2009; Blackhurst et al., Citation2011; Ambulkar et al., Citation2015; Hohenstein et al., Citation2015; Tukamuhabwa et al., Citation2015; Kamalahmadi and Parast, Citation2016; Datta, Citation2017; Dubey et al., 2019). However, there are contradictory views about the time, cost and speed of recovery (Hohenstein et al., Citation2015; Datta, Citation2017). Each of these dimensions has been measured in different ways.

Table 7. Definitions of supply chain resilience set out in the studies.

Other researchers have defined supply chain resilience in terms of proactive strategies. For example, Ponomarov and Holcomb (Citation2009) and Hohenstein et al., (Citation2015) defined supply chain resilience as the ability to prepare for unexpected risk events, respond to disruptions and recover from them. These definitions revolve around four main dimensions of supply chain resilience capabilities: re-engineering, collaboration, agility, and risk management culture. Overall, the definitions generally split into two groups: proactive definitions rely on building resilience capabilities, and reactive ones respond and recover after disruption.

3.5.2. Supply chain reconfiguration as an enabler for supply chain resilience

None of the reviewed studies clearly defined supply chain reconfiguration, except the empirical paper by Ambulkar et al. (Citation2015). They proposed a definition for resources reconfiguration of ‘the ability of a firm to reconfigure, realign, and reorganise their resources in respond to changes in the firm’s external environment'. A clear definition of supply chain reconfiguration is therefore needed to ensure greater consistency among future studies.

3.6. Supply chain resilience enablers (MQ5)

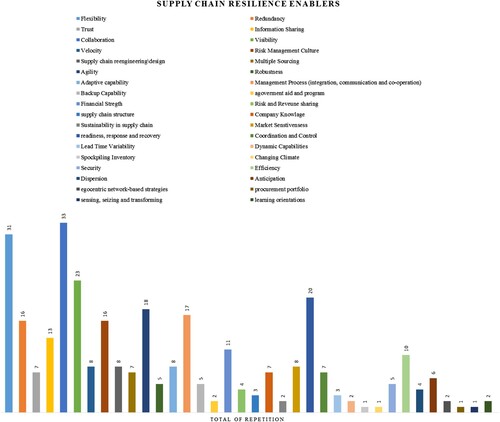

It has been posited that the three main components, that help organisations to build resilience are enablers, practices, and resources (Ponomarov and Holcomb, Citation2009). These not only help strategic decision-making processes post disruptions, as well as providing a competitive advantage to the firm (Ponomarov and Holcomb, Citation2009). The articles reviewed provided 36 supply chain resilience enablers (see ). Collaboration and flexibility have been widely discussed in supply chain resilience articles, but are controversial. When stakeholders of the supply chain collaborate among themselves, there is not much space for flexibility to change/choose stakeholders. ‘Visibility and readiness’ and ‘response and recovery’ were the third and fourth most discussed enablers. However, very few studies have examined supply chain reengineering, velocity, adaptive capability, market sensitiveness, trust, multiple sourcing, company knowledge, coordination and control, anticipation, robustness, backup capability, and security. More recently, researchers have explored the importance of government aid and programmes, risk and revenue sharing, supply chain structure, sustainability in the supply chain, lead time variability, dynamic capabilities, stockpiling inventory, changing climate, dispersion, egocentric network-based strategies, procurement portfolio, sensing, seizing and transforming, and learning orientations.

For the sake of comprehensiveness, this study, therefore, focusses on the top 15 enablers, which, are discussed in the literature, and their impact on supply chain risk that may lead to supply chain reconfiguration ().

Table 8. Supply chain resilience enablers.

3.6.1. Risk management culture

Risk management culture is an important enabler to building supply chain resilience in the organisation (Kamalahmadi and Parast, Citation2016; Jain et al., Citation2017; Liu et al., Citation2018). It is defined as ‘infusing a culture of resilience and risk awareness to make it the concern of everyone' (Lima et al., Citation2018; Liu et al., Citation2018). Risk management culture is highly desirable for improved resilience in any organisation (Jain et al., Citation2017). It has been argued by many researchers that the culture of managing the risk in the supply chain should not be limited to business continuity and corporate risk (Scholten et al., Citation2014; Liu et al., Citation2018).

Risk management culture also helps the organisation to identify the possibility of risks, and upsurge the capability of the supply chain to alleviate risks and reduce its vulnerability (Jüttner and Maklan, Citation2011; Wieland and Wallenburg, Citation2013; Chowdhury and Quaddous, Citation2016). The supply chain can, therefore, only act to mitigate the risk and reduce vulnerability when organisations develop a risk management culture, for example, through the implementation of a total quality management approach (Jüttner and Maklan, Citation2011; Wieland and Wallenburg, Citation2013; Chowdhury and Quaddous, Citation2016). However, organisations must also enhance the continuity of the supply chain to create a risk management culture. Organisations can effectively integrate risk management procedures into operating structures, management policies, or response to uncertainty (Liu et al., Citation2018).

3.6.2. Coordination and control

Organisations need a strong control system for their supply chains, to detect disruptions quickly and provide speedy corrective action (Stone and Rahimifard, Citation2018; Dubey et al., 2019). Coordination and control are types of formative resilience capabilities that help organisations to manage their resources, especially those that span functional areas to maintain the supply chain process (Jüttner and Maklan, Citation2011; Ponomarov and Holcomb, Citation2009; Sharma and George, Citation2018). Coordination, information-sharing, and pre-existing knowledge among supply chain partners also improve the level of situational awareness (Ali et al., 2017; Sharma and George, Citation2018). Cooperation, as a relational competence, positively influences supply chain resilience (Wieland and Wallenburg, Citation2013).

3.6.3. Risk and revenue sharing

Sharing the risk and revenue across supply chains is highly desirable. Previous studies have found that it is essential for both long-term focus and collaboration among supply chain partners (Pettit et al., Citation2013; Jain et al., Citation2017). Partners should collaborate to identify direct supply chain risks and their possible causes or source. Sharing revenue is a key factor in increasing competitive advantage for all the supply chain partners (Jain et al., Citation2017).

3.6.4. Financial strength

Financial strength enables organisations to absorb cash flow fluctuations (Pettit et al., Citation2013; Pettit et al., Citation2010). Supply chains must interpret the market position to recover from the disruptions of supply chain through financial strength (Ali et al., 2017) and organisational efficiency (Ponomarov and Holcomb, Citation2009). Some studies on supply chain resilience have shed light on the important of financial strength in building supply chain resilience (Gunasekaran et al., Citation2015; Chowdhury and Quaddus, Citation2016). Specific capabilities of organisations with financial strength include insurance, portfolio diversification, financial reserves and liquidity, price margin, profitability, and availability of funds (Pettit et al., Citation2010; Pettit et al., Citation2013; Chowdhury and Quaddus, Citation2015). Financial strength is also an important part of supply chain readiness to build resilience (Kochan and Nowicki, Citation2018).

3.6.5. Robustness

Robustness is defined as ‘the ability of a supply chain to resist change without adapting its initial stable configuration' (Wieland and Wallenburg, Citation2012). Ongoing operation during a disturbance is therefore an important indicator of robustness (Purvis et al., Citation2016; Behzadi et al., Citation2017). Supply chain robustness can mitigate the threat of poor organisational performance and maintain long-term economic stability in the face of supply chain disruptions (Brandon-Jones et al., Citation2014). Some authors have suggested that robustness is a subset of resilience (Brandon-Jones et al., Citation2014; Behzadi et al., Citation2017), with a slight difference in the process. However, others have argued that there is a trade-off between robustness and flexibility (Jüttner and Maklan, Citation2011; Johnson et al., Citation2013): flexibility enables supply chains to take more possible forms, and robustness increases the number of changes that the supply chain can manage.

3.6.6. Collaboration

Some studies have suggested that collaboration is vital in overcoming risk (Ponomarov and Holcomb, Citation2009). Collaboration is defined as the ability of organisations or supply chains to work effectively and respond quickly to supply chain disruptions with partners and other supply chain entities (Tukamuhabwa et al., Citation2015). Good relationships will ensure the exchange of information and knowledge, visibility, flexibility, operational effectiveness and efficiency, and customer service (Jüttner and Maklan, Citation2011; Pettit et al., Citation2013; Scholten et al., Citation2014; Gunasekaran et al., Citation2015; Scholten and Schilder, Citation2015). Most importantly, collaboration is a formative element of a resilient supply chain (Scholten and Schilder, Citation2015), which reduces uncertainty by distributing risk (Kamalahmadi and Parast, Citation2016). Several previous studies have examined the relationship between collaboration and supply chain resilience and found that collaboration had a positive relationship with supply chain resilience (Scholten and Schilder, Citation2015; Chowdhury and Quaddus, Citation2016; Jüttner and Maklan, Citation2011).

3.6.7. Agility

Agility is the ability to respond to changes and positional or actual unpredictable events (Scholten et al., Citation2014; Tukamuhabwa et al., Citation2015). It is associated with responsiveness to supply chain disruption and emergencies, to reduce the impact of disturbances (Ponomarov and Holcomb, Citation2009; Ali et al., 2017). Visibility and velocity are two dimensions of agility (Scholten et al., Citation2014). They both reduce the intensity of resources required and increase the speed of recovery (Brandon-Jones et al., Citation2014). Creating supply chain visibility that embraces confidence and encourages product tracking helps firms to understand that visibility is important (Brandon-Jones et al., Citation2014; Jüttner and Maklan, Citation2011). On the other hand, velocity may affect three different areas of risk: the rate at which events happen, the rate at which they fade, and the time of discovery (Jüttner and Maklan, Citation2011). It is, therefore, considered an important part of agility. Collaboration and flexibility can also improve agility by allowing the companies to act faster and select an appropriate plan and strategy to lessen the effects of disruptions (Gunasekaran et al., Citation2015).

3.6.8. Supply chain re-engineering/design

Supply chain re-engineering is mainly concerned to achieve the two objectives of cost optimisation and customer satisfaction (Kamalahmadi and Parast, Citation2016). The complexity of the business environment means that traditional supply chain designs are no longer valid. They need to be redesigned to integrate resilience into their design because it is difficult to develop a prevention strategy after the disruption has happened (Scholten et al, Citation2014). Instead, supply chains must be flexible and contain redundancy to manage disruptions. Flexibility is the capability of the supply chains to respond quickly to positive and negative environmental influences and select the most suitable options (Gunasekaran et al., Citation2015). Researchers studying supply chain flexibility (Scholten and Schilder, Citation2015; Scholten et al., Citation2014; López and Ishizaka, 2017; Rajesh Citation2017; Liu et al., 2018) have argued that flexibility increases the responses to disruption (Brusset and Teller, Citation2017). Redundancy is having organisational resources that can be used during disturbances to replace lost resources or capital (Lima et al., 2018). Both are therefore core elements for supply chain resilience (Hohenstein et al., Citation2015).

3.6.9. Backup capacity

Backup capacity is an important resilience strategy (Behzadi et al., Citation2017; Datta, Citation2017) and has been widely highlighted in previous studies (Pettit et al., Citation2013). It provides flexibility by obtaining supplies from backup sources in the event of a disruption to production time or yield (Behzadi et al., Citation2017). Backup suppliers, locations, and facilities can all help to maintain production processes (Namdar et al., Citation2018). Some authors have noted that having backup suppliers could create redundancy in the supply chain (Chowdhury and Quaddus, Citation2016; Kamalahmadi and Parast, Citation2016; Chowdhury and Quaddus, Citation2017).

3.6.10. Multiple sourcing

Multiple souring is another resilience strategy designed to enhance general supply chain resilience by providing contingency and mitigation strategies to reduce the impact of disruption (Yang and Xu, Citation2015). Multiple or dual sourcing mitigates the risk of disruption by having multiple suppliers or enlarging the supply base to include new suppliers (Behzadi et al., Citation2017). Organisations need to invest in preventive measures, such as multiple suppliers, to ensure resilience and have strong readiness and growth phases (Hohenstein et al., Citation2015). Like a backup capability, multiple sourcing is a redundancy component used to prevent stockouts (Hohenstein et al., Citation2015; Kamalahmadi and Parast, Citation2016; Ali et al., 2017).

3.6.11. Adaptive capability

Adaptive capability is a common factor in supply chain resilience definitions. Most researchers have described it as the ability to prepare for unexpected events, and respond to and recover from disruption (Jüttner and Maklan, Citation2011; Ponomarov and Holcomb, Citation2009). Adaptive capability deals with temporary disruptive events and is realissed through three distinct phases: supply chain readiness, responsiveness, and recovery (Jain et al., Citation2017).

3.6.12. Trust

The concept of trust can be described as the facilities, cooperation, and collaboration within and across the boundary of supply chains (Adobor, Citation2019). Trust is an important enabler of supply chain resilience (Jain et al., Citation2017). Lack of trust and collaboration can limit flexibility in the supply chain (Jüttner and Maklan, Citation2011). The interrelationship between trust, cooperation and commitment therefore helps the supply chain partners to reduce network uncertainty (Chowdhury and Quaddus, Citation2016). Therefore, there is a positive relationship between supply chain orientation and integration (or trust), and supply chain resilience (Chowdhury and Quaddus, Citation2016; Liu et al., Citation2018).

3.6.13. Information sharing

Information sharing is important between supply chain partners (Lima et al., Citation2018). Relevant information shared effectively and efficiently between supply chain partners can enhance collaboration by maintaining transparency and building trust (Mandal, Citation2017). Collaboration activities, collaborative communication, information sharing, joint relationship efforts, and mutually created knowledge all improve supply chain resilience through flexibility, velocity, and visibility (Brandon-Jones et al., Citation2014; Scholten and Schider, Citation2015). Information sharing alone also positively influences supply chain resilience (Chowdhury and Quaddus, Citation2016).

3.6.14. Integration

Integration capability is a proactive aspect of supply chain resilience (Chowdhury and Quaddus, Citation2017; Jüttner and Maklan, Citation2011) and helps to mitigate supply chain disruption (Pettit et al., Citation2010, Citation2013). It is also one of the relational capabilities (i.e. communication, co-operation, and integration) that affect supply chain resilience (Wieland and Wallenburg, Citation2013). Supply chain integration is defined as

the degree to which a manufacturer strategically collaborates with its supply chain partners and collaboratively manages intra- and inter- organization processes. The goal is to achieve effective and efficient flows of products and services, information, money and decisions, to provide maximum value to the customer at low cost and high speed. (Naylor et al., Citation1999; Frohlich and Westbrook, Citation2001; Flynn et al., Citation2010, Brusset and Teller, Citation2017)

3.6.15. Readiness, recovery, and response

The concepts of readiness, response, and recovery are fundamental to an understanding of supply chain resilience capability (Ponomarov and Holcomb, Citation2009; Hohenstein et al., Citation2015; Chowdhury and Quaddus, Citation2016; Kochan and Nowicki, Citation2018; Scholten et al., Citation2019). ‘Readiness' is a measurement of the extent to which a supply chain can overcome disruptive events (Chowdhury and Quaddus, Citation2016). Disruption detection, readiness training, readiness resources, early warning systems, forecasting, and security are all sources of supply chain readiness mentioned in previous studies (Pettit et al., Citation2013; Chowdhury and Quaddus, Citation2017). Each of these plays an important role in reducing the impact of disruptions. The higher level of supply chain readiness decreases the impact of disruption.

‘Response' is the ability to manage disruptions in a short time with low impact (Wieland and Wallenburg, Citation2013; Pettit et al., Citation2013). The speed of response plays a major role in reducing the cost of disruption (Wieland and Wallenburg, Citation2013; Pettit et al., Citation2013; Rajesh, Citation2017; Singh et al., Citation2018; Ivanov et al., Citation2018). Agility, velocity, visibility, flexibility, and redundancy all place a strong emphasis on the efficiency of the supply chain responses and recovery (Jüttner and Maklan, Citation2011; Scholten and Schilder, Citation2015; Kochan and Nowicki, Citation2018).

The ability to recover from disruptions and return to a normal state is a unique ability of organisations and supply chains (Pettit et al., Citation2013; Ambulkar et al., Citation2015; Chowdhury and Quaddus, Citation2016). Two factors are particularly important in recovery: time and cost (Tukamuhabwa et al., Citation2015; Scholten and Schilder, Citation2015; Singh et al., Citation2019). They depend on the ability of the supply chain to respond to disruptions.

3.7. Supply chain reconfiguration characteristics (MQ6)

A number of studies have found that many organisations choose to make decisions about allocation and reallocation of activities (Hammami and Frein, Citation2014), facilities (Wilhelm et al., Citation2013), inventory (Kristianto et al., Citation2012), suppliers and plants (Guo, et al., Citation2018), production (Kinkel, Citation2012), and capabilities (Osman and Demirli, Citation2010) to manage supply chain risks. Allocation and reallocation characteristics have become increasingly ubiquitous in supply chain reconfiguration studies, the challenge for allocation and reallocation is to protect supply chain uniqueness, while also expanding reach to enable the supply chain to stand out, across a multi-period planning horizon (Hammami and Frein, Citation2014). Differentiation can occur at any point in the reconfiguration process, including supplier selection, physical flow, transfer pricing, information sharing, distribution of materials, supply chain design and structure, and change items, such as change path, start point, style, target, roles, and levels (Van Hoek et al., Citation2010; Osman and Demirli, Citation2010; Hammami and Frein, Citation2014; Dev et al., Citation2016). shows studies on supply chain reconfiguration published over the last 10 years for various characteristics.

Table 9. Supply chain reconfiguration characteristics.

Redesigning supply chains usually leads to closing of existing facilities and opening new ones. Many researchers have argued that the capacity of facilities usually remains stable over time (Wilhelm et al., Citation2013). This means that facilities tend to remain in the same state (i.e. open or closed) until the end of the planning horizon (Wilhelm et al., Citation2013). The capacity of a particular facility therefore cannot be changed during the planning period (Wilhelm et al., Citation2013), though the cost of closing and open facilities is still rarely considered. Hammami and Frein (Citation2014) found that if the cost of closing a facility was more than 30,000 or 20,000 Euros, organisations tended to keep the original site. However, the nature of the function is even more important in supply chain reconfiguration.

The main objective of supply chain reconfiguration is therefore to establish a balance between the cost of supply chain reconfiguration (i.e. cost of replacing suppliers, or changing the transportation network) and supply chain operation (i.e. the cost of transportation, procurement, and manufacturing) (Guo et al., Citation2018). Organisations can also use echelons inventory, which involves finding new ways to do things such as introducing or removing echelons. Different suppliers and production and distribution options for raw materials, finished goods, and final products are involved in each reconfiguration alternative (Dev et al., Citation2014). The performance of each echelon is therefore unique. Each echelon serves a particular product and is linked with a viable transportation system that allows shipment from a facility in one echelon to another (Wilhelm et al., Citation2013). Lee et al., (Citation2015) studied agile and non-agile supply chain before and after reconfiguration and found that skewed order allocation strategy is more vulnerable by external unexpected disruption hence calling for reconfiguration.

As stated earlier, the ability of a firm to deal with supply chain disruptions and to be resilient, needs reconfiguration in its resources. Firms, which are ready to handle disruptions, are proactively engaged in configuring and manoeuvring resources in their supply chains (Bode et al., Citation2011, Ambulkar et al., Citation2015). In addition, those organisations which spend time learning and scanning the environment develops capabilities that improve responsiveness (Ramaswami et al., Citation2009). Reconfiguration is an important mechanism to deal with disruptions and build a resilient supply chain (Ambulkar et al., Citation2015; Blackhurst et al., Citation2011; Datta et al., Citation2017) and its role in times of disruption cannot be ignored. The role of reconfiguration as a mediator between supply chain resilience and supply chain disruption has been investigated by authors in the past (Bode et al., Citation2011; Ambulkar et al., Citation2015). In case of the high level of disruptions, the ability to restructure and reconfigure existing resources and acquire new resources re-strengthens the supply chain (Blackhurst et al., Citation2011; Jafarian and Bashiri, Citation2014). For instance, the aftermath of the massive earthquake in Japan in the year 2011 can be taken as an example where, the ability to reconfigure and leverage resources became the key aspect of recovery from the disruption (Olcott and Oliver, Citation2014). Although, for low impact disruptions, reconfiguration may not be necessary to establish resilience (Ambulkar et al., Citation2015), but prior experience to deal with disruptions using reconfiguration and resilience, is useful to absorb the unexpected shocks (Melnyk et al., Citation2014).

4. Implications of the study

4.1. Theoretical implications

No modern supply chain can survive without some form of resilience, and investment in resilience can also enhance a supply chain in previously unimagined ways (Chowdhury and Quaddus, Citation2016; Dubey et al., 2019). Supply chain resilience can be used to improve productivity or reliability or to decrease the risk in the supply chain. Previous researchers have called for new research on building supply chain resilience (e.g. Jüttner and Maklan, Citation2011; Johnson et al., Citation2013; Scholten and Schneider, Citation2015; Mandal et al., Citation2016; Chowdhury and Quaddus, Citation2016). None of the existing papers on supply chain resilience has attempted an empirical examination for an integrated framework of supply chain resilience, with supply chain reconfiguration, except for Ambulkar et al. (Citation2015), who proposed an integrated framework for firm resilience and supply chain disruptions on the basis of resource reconfiguration and risk management resources infrastructure. They also developed a measurement scale to examine the impact of supply chain disruption orientation, resources reconfiguration, and risk management infrastructure on firm resilience. Researchers in the past have empirically tested and proposed few supply chain resilience frameworks and hence, suggesting strategies to effectively reduce and recover from the impact of disruptions (Jüttner and Maklan, Citation2011; Wieland and Wallenburg, Citation2013; Ambulkar et al., Citation2015; Scholten and Schneider, Citation2015; Chowdhury and Quaddus, Citation2016; Liu et al., Citation2018). However, there is a dearth of literature, when it comes to search for correlations between supply chain resilience and supply chain reconfiguration.

Moreover, there is a lacuna regarding studies focusing on various interventions, mechanisms and outcomes explored in the current literature; with Jüttner and Maklan (Citation2011) being an exception. They build up the longitudinal case with resilience and risk management concepts vis-à-vis the global financial crisis. Time-based empirical studies will build more reliable outcomes to the dynamics of supply chain reconfiguration and its effect on resilience. This shall help in purging the current lacunae in the field of supply chain re-configuration.

Examining the different dimensions of supply chain resilience can give a reasonably complete picture, but is not considered sufficient (Ambulkar et al., Citation2015). There are multiple levels involved across the four dimensions of supply chain resilience (i.e. re-engineering, collaboration, agility, and risk management culture) (Chowdhury and Quaddus, Citation2016). Supply chain resilience can be considered at various levels including national (Khan et al., Citation2012), industry (Lim-Camacho et al, Citation2017; Rajesh, Citation2017), supply chain (Johnson et al., Citation2013; Urciuoli et al., Citation2014; Behzadi et al., Citation2017), and organisational levels (Jüttner and Maklan, Citation2011; Scholten and Schider, Citation2015; Tukamuhabwa et al., Citation2017). However, the majority of supply chain reconfiguration studies have considered the industry level of analysis (Godsell et al., Citation2010; Kinkel, Citation2012; Dev, et al., Citation2016). There is, therefore, a shortage of multilevel studies on supply chain resilience and reconfiguration. Most of the previous studies have also been in developed countries, and their results varied by industry and setting, making it difficult to develop effective theories and practices. Research in other contexts, such as Arab Middle East countries, can therefore provide useful insights for both researchers and practitioners. This approach will also add to supply chain management literature about supply chain resilience and reconfiguration processes in these countries.

Many previous studies used a case study approach (Khan et al., Citation2012; Cardoso et al., Citation2015; Scholten and Schider, Citation2015; Behzadi et al., Citation2017; López and Ishizaka, Citation2019; Tukamuhabwa et al., Citation2017). Others have used surveys across different sectors and organisations (Pettit et al., Citation2013; Chowdhury and Quaddus, Citation2016; Brusset and Teller, Citation2017). None of the previous studies used mixed methods to address the limitation of response bias and improve generalizability. A mixed method study could provide a deeper understanding of the phenomenon and enhance internal and external validity. ‘Built to last' may sound essential in any form of production, but there is no clear model or process of supply chain reconfiguration.

4.2. Managerial implications

In this study, we focussed on the need to consolidate the risk, resilience, and reconfiguration in a supply chain thus promoting a coherent knowledge framework. It is evident from this study that there is a need to create an advanced understanding on resilience with reconfiguration as one of the important consequences. By understanding, the impact of reconfiguration while designing a resilient supply chain, managers and practitioners can achieve more clarity under complex supply chain situations and disruptions. Investing in resilience will have an impact on reconfiguration costs. The importance of reconfiguration and resilience can be well understood in supplier selection, launching a new product etc., so managers need to be on vigil in such critical decision-making situations requiring triggering policy improvements (Alexandre et al., Citation2017). In case of any disruption or risk, reconfiguration is critical, complicated and becomes time consuming (Aghapour et al., Citation2019; Ivanov and Dolgui, Citation2020). Early adoption of reconfiguration to build supply chain resilience will help in timely interventions to mitigate risks.

4.3. Social implications

Resilience in supply chains is also useful in building sustainability. Supply chains are becoming global and are building network structures of the modern economy. It directly affects the rates of employment, consumption of resources, etc. Therefore, an efficient supply chain structure can have a major social impact during times of disruptions (Alexandre et al., Citation2017). Disruptions bring along industrial disruptions and human catastrophe at the same time. In such times, supply chain resilience and reconfiguration become critically important for the recovery of the industry and stabilisation of everyday life. A recent outbreak of coronavirus (COVID-19) shows that in case of extraordinary events, supply chain resistance to disruptions needs to be considered to avoid industrial and social challenges (Ivanov and Dolgui, Citation2020).

4.4. Unique contribution

The study can be considered as the first attempt to use a systematic review mapping methodology in supply chain resilience and reconfiguration. In response to a particular disruption, managers are perplexed in choosing the appropriate practices. The contribution of this research is twofold. First, it identifies the most important enablers for supply chain resilience and secondly it provides an understanding of the characteristics of supply chain reconfiguration. This is one of the few studies, which focus on the need to consolidate supply chain risk, resilience, and reconfiguration research and create a coherent knowledge framework. The current critical review could help in providing momentum to future studies regarding supply chain reconfiguration and its association with supply chain resilience. This also echoes with the suggestions of Ambulkar et al. (Citation2015). Although the articles published on supply chain resilience are many, only few discuss the need for coherence between resilience and reconfiguration (Bode et al., Citation2011; Blackhurst et al., Citation2011; Ambulkar et al., Citation2015; Datta et al., Citation2017). The consolidation among the said constructs may not only shed initial light on supply chain resilience and reconfiguration theme, but also help in adding to the worth of literature.

5. Conclusions and future research directions

The review is carried out using a PICOC (Kitchenham and Charters, Citation2007) framework. A set of prepositions is developed linking the concept of resilience with reconfiguration. They are present in the literature but studied separately without a coherent framework. This systematic review reveals future prospects in the field of resilience and reconfiguration of a supply chain. Most studies are skewed towards supply chain resilience, but the importance of reconfiguration as an enabler to resilience is yet to be explored across various economies. To minimise the amount of time needed to recover from supply chain disruption, supply chains and organisations frequently build resilience. One of the advantages of supply chain resilience is that it improves management of the complexities of global supply chains (Pettit et al., Citation2013), because there is no need to replicate expensive mistakes. Supply chain issues can arise quickly, and supply chain resilience enablers build effective practices to reduce and mitigate these risks. Uncontrolled risks may lead to reconfiguration of the supply chain to return to the normal or equilibrium level, requiring immediate action and major change.

As explained earlier, reconfiguration is studied with different names like restructuring, configuration, dynamic networking, etc. But empirical investigations explaining the supply chain resilience-reconfiguration dyad, are minimal. Thus, future studies using focal firms should create an advanced understanding of resilience with reconfiguration as one of the enablers. Also, the impact of reconfiguration on resilience with multiple interventions can lead to a better understanding of the phenomenon and can give more clarity to supply chain managers and practitioners. Different research methodologies may be followed in order to gain insights. The literature fails to connect the link between disruptions and the practices followed in the industry, no integrated framework has been developed for supply chain resilience with reconfiguration, therefore, there is an urgent need to create a link between the two. High-level disruptions (for example Pandemic – Covid 19) require an urgent attention to the ever-growing field of supply chain resilience with focus on enablers. Further ‘proposal of solution'-type research is also required to provide a broader picture of problems and solutions, and benefit both academics and organisations. Further research is needed on how supply chains are reconfigured following issues or to address risks. Linking supply chain resilience to reconfiguration may also add to the supply chain risk management literature. First, it will advance our knowledge of the role of resilience in reconfiguring supply chains. Second, it will help managers to understand whether investing in resilience will reduce reconfiguration costs. Third, it will provide a clear view of supply chain reconfiguration process. Finally, it will enhance knowledge on which resilience enablers help in reconfiguring the supply chain before and after disturbances.

This review paper has tried to provide insights on supply chain resilience and reconfiguration research and how it can be improved further to enrich our understanding in this area. A systematic mapping review of supply chain resilience and reconfiguration has shown the interconnectedness from building resilience enablers into supply chains. The review has also shown the main characteristics used to reconfigure supply chains. Future studies can build on this review to examine the role of supply chain resilience in reconfiguring the supply chain. It should be noted, that systematic mapping review method is the fallible nature of judgement and rating process in interpreting information, including articles for the review, and synthesising evidence are as per the queries the way researcher wants to address. This study is qualitative in nature and the theory developed can be validated using empirical/mathematical prepositions. We have used the top 15 most discussed enablers in this study. Future studies may include more enablers as over a period, some enablers may emerge as more important in the literature on supply chain resilience and reconfiguration. This study calls for studying the impact of reconfiguration on supply chain resilience at times of disruptions. Future studies can focus on strategic aspects of supply chain reconfiguration and resilience with top enablers and mechanisms to help to build a competitive advantage in times of disruptions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adobor, H. 2019. “Supply Chain Resilience: A Multi-level Framework.” International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications 22 (6): 533–556.

- Aghapour, A. H., M. Yazdani, F. Jolai, and M. Mojtahedi. 2019. “Capacity Planning and Reconfiguration for Disaster-resilient Health Infrastructure.” Journal of Building Engineering 26: 100853.

- Alcantara, P., and G. Riglietti. 2015. Supply Chain Resilience Report 2015. London: Business Continuity Zurich.

- Alexandre, D., I. Dmitry, and S. Boris. 2017. “Ripple Effect in the Supply Chain: An Analysis and Recent Literature.” International Journal of Production Research 56 (1-2): 414–430.

- Ali, I., and I. Gölgeci. 2019. “Where is Supply Chain Resilience Research Heading? A Systematic and Co-occurrence Analysis.” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 49 (8): 793–815.

- Ambulkar, S., J. Blackhurst, and S. Grawe. 2015. “Firm's Resilience to Supply Chain Disruptions: Scale Development and Empirical Examination.” Journal of Operations Management 33-34: 111–122.

- Arias, M., R. Saavedra, M. R. Marques, J. Munoz-Gama, and M. Sepúlveda. 2018. “Human Resource Allocation in Business Process Management and Process Mining.” Management Decision 56 (2): 376–405.

- Arksey, H., and L. O'Malley. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1): 19–32.

- Behzadi, G., M. J. O'Sullivan, T. L. Olsen, F. Scrimgeour, and A. Zhang. 2017. “Robust and Resilient Strategies for Managing Supply Disruptions in an Agribusiness Supply Chain.” International Journal of Production Economics 191: 207–220.

- Bhatia, G., C. Lane, and A. Wain. (2013) ‘Building Resilience in Supply Chains. An Initiative of the Risk Response Network in Collaboration with accenture’. In World Economic Forum. Geneva, 1–40.

- Blackhurst, J., K. S. Dunn, and C. W. Craighead. 2011. “An Empirically Derived Framework of Global Supply Resiliency.” Journal of Business Logistics 32 (4): 374–391.

- Bode, C., and S. M. Wagner. 2015. “Structural Drivers of Upstream Supply Chain Complexity and the Frequency of Supply Chain Disruptions.” Journal of Operations Management 36 (5): 215–228.

- Bode, C., S. M. Wagner, K. J. Petersen, and L. M. Ellram. 2011. “Understanding Responses to Supply Chain Disruptions: Insights from Information Processing and Resource Dependence Perspectives.” Academy of Management Journal 54 (4): 833–856.

- Bogataj, D., and M. Bogataj. 2007. “Measuring the Supply Chain Risk and Vulnerability in Frequency Space.” International Journal of Production Economics 108 (1-2): 291–301.

- Brandon-Jones, E., B. Squire, C. W. Autry, and K. J. Petersen. 2014. “A Contingent Resource-based Perspective of Supply Chain Resilience and Robustness.” Journal of Supply Chain Management 50 (3): 55–73.

- Brusset, X., and C. Teller. 2017. “Supply Chain Capabilities, Risks, and Resilience.” International Journal of Production Economics 184: 59–68.

- Cardoso, S. R., A. P. Barbosa-Póvoa, S. Relvas, and A. Q. Novais. 2015. “Resilience Metrics in the Assessment of Complex Supply-chains Performance Operating Under Demand Uncertainty.” Omega 56: 53–73.

- Chandra, C., and J. Grabis. 2009. “Configurable Supply Chain: Framework, Methodology and Application.” International Journal of Manufacturing Technology and Management 17 (1-2): 5–22.

- Cheng, J., and K. Lu. 2017. “Enhancing Effects of Supply Chain Resilience: Insights from Trajectory and Resource-Based Perspectives.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 22 (4): 329–340.

- Chopra, S., and M. S. Sodhi. 2004. “Managing Risk to Avoid Supply-chain Breakdown.” MIT Sloan Management Review 46 (1): 53–61.

- Chowdhury, M. M. H., and M. A. Quaddus. 2015. “A Multiple Objective Optimization Based QFD Approach for Efficient Resilient Strategies to Mitigate Supply Chain Vulnerabilities: The Case of Garment Industry of Bangladesh.” Omega 57: 5–21.

- Chowdhury, M. M. H., and M. A. Quaddus. 2016. “Supply Chain Readiness, Response and Recovery for Resilience.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 21 (6): 709–731.

- Chowdhury, M. M. H., and M. A. Quaddus. 2017. “Supply Chain Resilience: Conceptualization and Scale Development Using Dynamic Capability Theory.” International Journal of Production Economics 188: 185–204.

- Christopher, M., and H. Peck. 2004. “Building the Resilient Supply Chain.” The International Journal of Logistics Management 15 (2): 1–14.

- Colicchia, C., A. Creazza, and D. A. Menachof. 2019. “Managing Cyber and Information Risks in Supply Chains: Insights from an Exploratory Analysis.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 24 (2): 215–240.

- Datta, P. 2017. “Supply Network Resilience: A Systematic Literature Review and Future Research.” The International Journal of Logistics Management 28 (4): 1387–1424.

- Davis, J. P., K. M. Eisenhardt, and C. B. Bingham. 2009. “Optimal Structure, Market Dynamism, and the Strategy of Simple Rules.” Administrative Science Quarterly 54 (3): 413–452.

- Davis, J., K. Mengersen, S. Bennett, and L. Mazerolle. 2014. “Viewing Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis in Social Research Through Different Lenses.” SpringerPlus 3 (1): 511–519.

- Dev, N. K., R. Shankar, A. Gunasekaran, and L. S. Thakur. 2016. “A Hybrid Adaptive Decision System for Supply Chain Reconfiguration.” International Journal of Production Research 54 (23): 7100–7114.

- Dev, N. K., R. Shankar, and P. Kumar Dey. 2014. “Reconfiguration of Supply Chain Network: An ISM-based Roadmap to Performance.” Benchmarking: An International Journal 21 (3): 386–411.

- Dubey, R., A. Gunasekaran, S. J. Childe, T. Papadopoulos, C. Blome, and Z. Luo. 2019a. “Antecedents of Resilient Supply Chains: An Empirical Study.” IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 66 (1): 8–19.

- Dubey, R., A. Gunasekaran, S. J. Childe, S. F. Wamba, D. Roubaud, and C. Foropon. 2019b. “Empirical Investigation of Data Analytics Capability and Organizational Flexibility as Complements to Supply Chain Resilience.” International Journal of Production Research, 59(1): 110–128.

- Flynn, B. B., B. Huo, and X. Zhao. 2010. “The Impact of Supply Chain Integration on Performance: A Contingency and Configuration Approach.” Journal of Operations Management 28 (1): 58–71.

- Frohlich, M. T., and R. Westbrook. 2001. “Arcs of Integration: an International Study of Supply Chain Strategies.” Journal of Operations Management 19 (2): 185–200.

- Godsell, J., A. Birtwistle, and van Hoek R. 2010. “Building the Supply Chain to Enable Business Alignment: Lessons from British American Tobacco (BAT).” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 15 (1): 10–15.

- Grant, M. J., and A. Booth. 2009. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal 26 (2): 91–108.

- Gunasekaran, A., H. Subramanian, H. and S, and S. Rahman. 2015. “Supply Chain Resilience: Role of Complexities and Strategies.” International Journal of Production Research 53 (22): 6809–6819.

- Guo, W., Q. Tian, Z. Jiang, and H. Wang. 2018. “A Graph-based Cost Model for Supply Chain Reconfiguration.” Journal of Manufacturing Systems 48: 55–63.

- Hammami, R., and Y. Frein. 2014. “Redesign of Global Supply Chains with Integration of Transfer Pricing: Mathematical Modeling and Managerial Insights.” International Journal of Production Economics 158: 267–277.

- Helfat, C. E., S. Finkelstein, W. Mitchell, M. A. Peteraf, H. Singh, D. J. Teece, and S. J. Winter. 2007. ‘Dynamic Capabilities: Understanding Strategic Chance in Organizations’. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Hemsley-Brown, J., and I. Oplatka. 2015. “University Choice: What Do We Know, What Don't We Know and What Do We Still Need to Find Out?” International Journal of Educational Management 29 (3): 254–274.

- Hohenstein, N. O., E. Feisel, E. Hartmann, and L. Giunipero. 2015. “Research on the Phenomenon of Supply Chain Resilience: A Systematic Review and Paths for Further Investigation.” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 45 (1-2): 90–117.

- Holmström, J., G. Liotta, and A. Chaudhuri. 2017. “Sustainability Outcomes Through Direct Digital Manufacturing-based Operational Practices: A Design Theory Approach.” Journal of Cleaner Production 167: 951–961.

- Hosseini, S., D. Ivanov, and A. Dolgui. 2019. “Review of Quantitative Methods for Supply Chain Resilience Analysis.” Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 125: 285–307.

- Ishfaq, R. 2012. “Resilience Through Flexibility in Transportation Operations.” International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications 15 (4): 215–229.

- Ivanov, D. 2018. “Supply Chain Management and Structural Dynamics Control.” In Structural Dynamics and Resilience in Supply Chain Risk Management Vol. 265. Springer, Cham.

- Ivanov, D. 2020. “Viable Supply Chain Model: Integrating Agility, Resilience and Sustainability Perspectives-lessons from and Thinking Beyond the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Annals of Operations Research, 1–21.

- Ivanov, D., and A. Dolgui. 2020. “Viability of Intertwined Supply Networks: Extending the Supply Chain Resilience Angles Towards Survivability. A Position Paper Motivated by COVID-19 Outbreak.” International Journal of Production Research 58 (10): 2904–2915.

- Ivanov, D., A. Dolgui, and B. Sokolov. 2018. “Scheduling of Recovery Actions in the Supply Chain with Resilience Analysis Considerations.” International Journal of Production Research 56 (19): 6473–6490.

- Jafarian, M., and M. Bashiri. 2014. “Supply Chain Dynamic Configuration as a Result of New Product Development.” Applied Mathematical Modelling 38 (3): 1133–1146.

- Jain, V., S. Kumar, U. Soni, and C. Chandra. 2017. “Supply Chain Resilience: Model Development and Empirical Analysis.” International Journal of Production Research 55 (22): 6779–6800.

- Johnson, N., D. Elliott, and P. Drake. 2013. “Exploring the Role of Social Capital in Facilitating Supply Chain Resilience.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 18 (3): 324–336.

- Jüttner, U., and S. Maklan. 2011. “Supply Chain Resilience in the Global Financial Crisis: an Empirical Study.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 16 (4): 246–259.

- Jüttner, U., H. Peck, and M. Christopher. 2003. “Supply Chain Risk Management: Outlining an Agenda for Future Research.” International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications 6 (4): 197–210.

- Kamalahmadi, M., and M. M. Parast. 2016. “A Review of the Literature on the Principles of Enterprise and Supply Chain Resilience: Major Findings and Directions for Future Research.” International Journal of Production Economics 171: 116–133.

- Khan, O., C. Martin, and A. Creazza. 2012. “Aligning Product Design with the Supply Chain: A Case Study.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 17 (3): 323–336.

- Kinkel, S. 2012. “Trends in Production Relocation and Backshoring Activities. Changing Patterns in the Course of the Global Economic Crisis.” International Journal of Operations and Production Management 32 (6): 696–720.

- Kinra, A., D. Ivanov, A. Das, and A. Dolgui. 2020. “Ripple Effect Quantification by Supplier Risk Exposure Assessment.” International Journal of Production Research 58 (18): 5559–5578.

- Kitchenham, B., and S. Charters. 2007. "Guidelines for Performing Systematic Literature Reviews in Software Engineering." Technical Report, Ver. 2.3 EBSE Technical Report, EBSE, SN.

- Kleindorfer, P. R., and G. H. Saad. 2005. “Managing Disruption Risks in Supply Chains.” Production and Operations Management 14 (1): 53–68.

- Kochan, C. G., and D. R. Nowicki. 2018. “Supply Chain Resilience: A Systematic Literature Review and Typological Framework.” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 48 (8): 842–865.

- Kristianto, Y., A. Gunasekaran, P. Helo, and M. Sandhu. 2012. “A Decision Support System for Integrating Manufacturing and Product Design Into the Reconfiguration of the Supply Chain Networks.” Decision Support Systems 52 (4): 790–801.

- Kunz, N., G. Reiner, and S. Gold. 2014. “Investing in Disaster Management Capabilities Versus Pre-positioning Inventory: A new Approach to Disaster Preparedness.” International Journal of Production Economics 157: 261–272.

- Lee, J., H. Cho, and Y. S. Kim. 2015. “Assessing Business Impacts of Agility Criterion and Order Allocation Strategy in Multi-criteria Supplier Selection.” Expert Systems with Applications 42 (3): 1136–1148.

- Lee, S. M., and J. S. Rha. 2016. “Ambidextrous Supply Chain as a Dynamic Capability: Building a Resilient Supply Chain.” Management Decision 54 (1): 2–23.

- Lim-Camacho, L., ÉE Plagányi, S. Crimp, J. H. Hodgkinson, A. J. Hobday, S. M. Howden, and B. Loechel. 2017. “Complex Resource Supply Chains Display Higher Resilience to Simulated Climate Shocks.” Global Environmental Change 46: 126–138.

- Lima Flávia Renata, P. D., A. L. Da Silva, F. M. Godinho, and E. M. Dias. 2018. “Systematic Review: Resilience Enablers to Combat Counterfeit Medicines.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 12 (2): 117–135.

- Liu, C. L., and M. Y. Lee. 2018. “Integration, Supply Chain Resilience, and Service Performance in Third-party Logistics Providers.” The International Journal of Logistics Management 29 (1): 5–21.

- López, C., and A. Ishizaka. 2019. “A Hybrid FCM-AHP Approach to Predict Impacts of Offshore Outsourcing Location Decisions on Supply Chain Resilience.” Journal of Business Research 103: 495–507.

- Mandal, S. 2017. “The Influence of Organizational Culture on Healthcare Supply Chain Resilience: Moderating Role of Technology Orientation.” The Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing 32 (8): 1021–1037.

- Mandal, S., R. Sarathy, V. R. Korasiga, S. Bhattacharya, and S. G. Dastidar. 2016. “Achieving Supply Chain Resilience: The Contribution of Logistics and Supply Chain Capabilities.” International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment 7 (5): 544–562.

- Marsh, S. J., and G. N. Stock. 2006. “Creating Dynamic Capability: The Role of Intertemporal Integration, Knowledge Retention, and Interpretation.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 23 (5): 422–436.

- Melnyk, S. A., D. J. Closs, S. E. Griffis, C. W. Zobel, and J. R. Macdonald. 2014. “Understanding Supply Chain Resilience.” Supply Chain Management Review 18 (1): 34–41.

- Namdar, J., X. Li, R. Sawhney, and N. Pradhan. 2018. “Supply Chain Resilience for Single and Multiple Sourcing in the Presence of Disruption Risks.” International Journal of Production Research 56 (6): 2339–2360.

- Naylor, J. B., M. M. Naim, and D. Berry. 1999. “Leagility: Integrating the Lean and Agile Manufacturing Paradigms in the Total Supply Chain.” International Journal of Production Economics 62 (1-2): 107–118.

- Olcott, G., and N. Oliver. 2014. “Social Capital, Sensemaking, and Recovery: Japanese Companies and the 2011 Earthquake.” California Management Review 56 (2): 5–22.

- Osman, H., and K. Demirli. 2010. “A Bilinear Goal Programming Model and a Modified Benders Decomposition Algorithm for Supply Chain Reconfiguration and Supplier Selection.” International Journal of Production Economics 124 (1): 97–105.

- Palmatier, R. W., M. B. Houston, and J. Hulland. 2018. “Review Articles: Purpose, Process, and Structure.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 46: 1–5.

- Petersen, K., R. Feldt, S. Mujtaba, and M. Mattsson. 2008. “Systematic Mapping Studies in Software Engineering.” In Ease 8: 68–77.

- Petersen, K., S. Vakkalanka, and L. Kuzniarz. 2015. “Guidelines for Conducting Systematic Mapping Studies in Software Engineering: An Update.” Information and Software Technology 64: 1–18.

- Pettit, T. J., K. L. Croxton, and J. Fiksel. 2013. “Ensuring Supply Chain Resilience: Development and Implementation of an Assessment Tool.” Journal of Business Logistics 34 (1): 46–76.

- Pettit, T. J., J. Fiksel, and K. L. Croxton. 2010. “Ensuring Supply Chain Resilience: Development of a Conceptual Framework.” Journal of Business Logistics 31 (1): 1–21.

- Ponis, S. T., and E. Koronis. 2012. “Supply Chain Resilience: Definition of Concept and its Formative Elements.” Journal of Applied Business Research (JABR) 28 (5): 921–930.

- Ponomarov, S. Y., and M. C. Holcomb. 2009. “Understanding the Concept of Supply Chain Resilience.” The International Journal of Logistics Management 20 (1): 124–143.

- Purvis, L., S. Spall, M. Naim, and V. Spiegler. 2016. “‘Developing a Resilient Supply Chain Strategy During ‘Boom’ and ‘Bust'’.” Production Planning & Control 27 (7-8): 579–590.

- Rajesh, R. 2017. “Technological Capabilities and Supply Chain Resilience of Firms: A Relational Analysis Using Total Interpretive Structural Modeling (TISM).” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 118: 161–169.

- Ramaswami, S. N., R. K. Srivastava, and M. Bhargava. 2009. “Market-based Capabilities and Financial Performance of Firms: Insights Into Marketing’s Contribution to Firm Value.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 37 (2): 97–116.

- Saenz, M. J., and E. Revilla. 2014. “Creating More Resilient Supply Chains.” MIT Sloan Management Review 55 (4): 22–24.

- Scholten, K., and S. Schilder. 2015. “The Role of Collaboration in Supply Chain Resilience.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 20 (4): 471–484.

- Scholten, K., P. S. Scott, and B. Fynes. 2014. “Mitigation Processes – Antecedents for Building Supply Chain Resilience.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 19 (2): 211–228.

- Scholten, K., P. S. Scott, and B. Fynes. 2019. “Building Routines for non-Routine Events: Supply Chain Resilience Learning Mechanisms and Their Antecedents.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 24 (3): 430–442.

- Sharma, S. K., and S. A. George. 2018. “Modelling Resilience of Truckload Transportation Industry.” Benchmarking: An International Journal 25 (7): 2531–2545.

- Sheffi, Y., and J. B. Rice Jr. 2005. “A Supply Chain View of the Resilient Enterprise.” MIT Sloan Management Review 47 (1): 41–48.