?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This study explores the interactional effects and fit of internal and external collaboration on supply chain performance based on the fit theory. Data collected from 205 firms located in China was used to test the hypotheses via partial least squares structural equation modelling, polynomial regression and response surface methodology. The results demonstrate that there is an interactive effect, i.e. fit between internal collaboration and external collaboration on supply chain performance – a phenomenon not previously well understood. The results indicate that not all firms implementing internal collaboration and external collaboration can attain the desired goals. Only when the strength and balance of the two are similar, and at a moderate to upper level, can the supply chain performance be achieved the best; and once a certain threshold value of internal collaboration and external collaboration is achieved, further enhancement in internal and external collaboration will cause the decline of supply chain performance. Our study emphasises the importance of balancing internal constraints and external requirements across the whole supply chain, and provides insights into supply chain collaboration by suggesting that internal collaboration and external collaboration must be fit in the pursuit of supply chain performance.

1. Introduction

Supply chain collaboration is one of the most debated topics in supply chain management (SCM) literature over three decades (Barratt Citation2004; Min et al. Citation2005; Walker et al. Citation2014; Soosay and Hyland Citation2015; Yildiz and Ahi Citation2020; Chowdhury et al. Citation2020; Zheng et al. Citation2021). It is defined as two or more companies (and/or departments within a company) coordinating and working with each other through sharing information (Anthony Citation2000). The objective is to jointly create competitive advantages and achieve better performance outcomes for both individual supply chain members and the whole supply chain (Pradabwong et al. Citation2017; Wu and Chiu Citation2018). Supply chain collaboration has been considered not only as the driving force behind effective SCM but also the possibly ultimate core capability of the supply chain (Sanders and Premus Citation2005; Chen and Ye Citation2020). Recent disruption events due to the COVID-19 make collaboration along the supply chain more important as it helps companies quickly respond to the changing market environment and more easily recover from disruptions through faster new product development, shorter lead times, and improved customer service (Gligor, Esmark, and Holcomb Citation2015; Nair et al. Citation2018; Wu and Chiu Citation2018; Duong and Chong Citation2020)

However, few companies have truly harnessed the potential of supply chain collaboration to achieve breakthrough performance (Min, Mentzer, and Ladd Citation2007; Fawcett et al. Citation2012; Duong and Chong Citation2020). A notable reason among others is that supply chain collaboration is never a simple concept but involves a series of complex practices that can be categorised into internal collaboration (collaboration with other functions/departments within the firm) and external collaboration (collaboration with other supply chain members) (Stank, Keller, and Daugherty Citation2001; Hillebrand and Biemans Citation2003; Barratt Citation2004; Duhamel, Carbone, and Moatti Citation2016; Wong, Wong, and Boon-Itt Citation2020; Feng, Jiang, and Xu Citation2020). The investigation of internal collaboration and external collaboration is important in the pursuit of supply chain performance as they are likely to influence performance differently (Flynn, Huo, and Zhao Citation2010; Schoenherr and Swink Citation2012; Yunus and Tadisina Citation2016). Some studies highlight the positive role of external collaboration (e.g. Frohlich and Westbrook Citation2001) while others emphasise that of internal collaboration (e.g. Flynn, Huo, and Zhao Citation2010). Recent studies suggest that internal and external collaboration do not exert influence separately but in an interactive or complementary way in improving supply chain performance (e.g. Duhamel, Carbone, and Moatti Citation2016; Murphy and Coughlan Citation2018; Liao and Li Citation2019).

Despite numerous studies have approached the performance implications of internal and external collaboration, it is still far from clear how internal collaboration and external collaboration interact to affect supply chain performance. Whether internal and external collaboration exerts influence on supply chain performance synchronously – a jointly positive or negative influence – (e.g. Gunasekaran, Subramanian, and Rahman Citation2015) or asynchronously – the existence of a mediator role (Sanders and Premus Citation2005; Zhao et al. Citation2011; Cheng, Chaudhuri, and Farooq Citation2016) or moderator role (Schoenherr and Swink Citation2012) of one on the other – remain an elusive concern. The relationship between two or more variables can be studied through the lens of the concept of fit (Venkatraman Citation1989), which expresses the adjustment of one or more variables in relation to another. Fit refers to compatibility among organisations and complementarity of their resources (Moshtari Citation2016). Venkatraman (Citation1989) presents six types of fit: fit as moderation, fit as mediation, fit as matching, fit as gestalts, fit as profile deviation and fit as covariation. More recently, the importance of integrating internal and external characteristics of companies and supply chain features gave rise to the concept of fit (Wagner, Grosse-Ruyken, and Erhun Citation2012; Gligor Citation2017). In particular, a most recent study offers a fit perspective while investigating the relationship among the context, supply chain collaboration, and performance outcomes, suggesting that the most used forms of fit are mediation and moderation (Danese, Molinaro, and Romano Citation2020). Taken in all, there may be a non-linear relationship between internal and external collaboration and performance outcomes, and previous studies have not provided a consistent answer.

Therefore, given the importance of internal and external collaboration on supply chain performance and the gap in the literature, this study aims to empirically explore the relationships among internal collaboration, external collaboration, and supply chain performance from a fit perspective. Based on the idea of ‘fit as matching' (Venkatraman Citation1989), fit in this study is a theoretically defined match between internal collaboration and external collaboration. The research question of this study is:

RQ. How does the fit of internal collaboration and external collaboration achieve better supply chain performance?

To answer this question, we collect data from 205 firms located in China and perform multiple tests including partial least squares structural equation modelling (PLS-SEM), polynomial regression, and response surface methodology. Our study contributes to SCM literature in three ways. First, it emphasises the importance of balancing internal constraints and external requirements across the whole supply chain. Second, the combined utilisation of polynomial regression and response surfaces clearly reveals the interaction of internal collaboration and external collaboration on supply chain performance. Third, this study provides insights into supply chain collaboration by suggesting that internal collaboration and external collaboration must be fit in the pursuit of supply chain performance. Once a certain threshold value of internal collaboration and external collaboration is achieved, further enhancement in internal collaboration and external collaboration will cause the decline of supply chain performance.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. The theoretical background and the conceptual model are provided in Section 2. This is followed by the hypotheses development in Section 3. The methodology used in this study is described in Section 4. The empirical analysis is illustrated in Section 5, which is further discussed for theoretical and managerial implications in Section 6. Finally, the study is concluded in Section 7.

2. Theoretical backgrounds

The concept of fit has gained attraction in the literature over the last few years (Zimmermann et al. Citation2021). Fit indicates consistency and harmony between two or more variables (Venkatraman Citation1989). From a supply chain perspective, fit implies that at least one of the supply chain members can provide what the other member needs, or that compatibility exists among supply chain members – in other words, they have common or similar characteristics (Sáenz, Revilla, and Knoppen Citation2014; Wang et al. Citation2015). A good fit is believed to have a positive impact on performance (Zhu et al. Citation2022; Wu et al. Citation2014). Zimmermann et al. (Citation2021) examine how the fit between innovation capabilities and supply chain strategies affects business performance. Amhalhal et al. (Citation2021) provided a better understanding of the usefulness of the fit/match between contingencies and measurement diversity in improving organisational performance. Companies have to match their internal characteristics with their environment in order to obtain superior performance (Venkatraman Citation1989; Grotsch, Blome, and Schleper Citation2013; Flynn, Koufteros, and Lu Citation2016). These results can also be examined through the lens of the resource-based view, to which different resources generate different results. According to the resource-based view, companies should seek to develop a set of characteristics including collaborating with external resources that are difficult to imitate and not easily substitutable (Hong et al. Citation2011; Laosirihongthong, Prajogo, and Adebanjo Citation2014). Fit in supply chain context is related to the best deployment, development and management of a company’s resources and to specific supply chain practices that enable the company to face specific challenges presented by its environment.

Here, the idea of fit focuses on the fit of the internal organisational structures and processes and the external context, i.e. suppliers and customers (Miller Citation1992). Regarding how internal collaboration and external collaboration should work together, some suggest a relatively balanced implementation of internal collaboration and external collaboration, while others argue for complementary implementation of internal collaboration and external collaboration for exploiting and exploring resources (Wong, Wong, and Boon-itt Citation2013). Internal collaboration refers to the degree to which internal cross-functional strategic actions and procedures form a coherent process within a firm (Wong, Wong, and Boon-Itt Citation2020). External collaboration refers to the extent to which a company builds partnerships with its suppliers and customers to transform strategic actions and procedures between organisations into a collaborative and consistent process (Stank, Keller, and Daugherty Citation2001; Feng, Jiang, and Xu Citation2020). Sabri (Citation2019) identifies internal collaboration mechanisms as the internal factors that are the most relevant to supply chain fit research.

In fact, the development of firms requires their adaptation to their major supply chain members and cultivates matches among the departments within a firm (Kim Citation2009). Based on absorption capacity, it will be ineffective to dominate excessively internal or external knowledge processes (Zahra and George Citation2002). Hence, the question becomes one of how the internal collaboration within a firm ‘fits’ the external collaboration of its supply chain members into a cohesive whole and identifying the potential performance implications. Therefore, we apply ‘fit’ as a mode of matching to delve more deeply into how internal collaboration and external collaboration work together. Models of Fisher (Citation1997a) and Lee (Citation2002) signify ‘fit’ as a mode of matching, i.e. the strength of internal collaboration matches the strength of external collaboration given that a firm pays equal attention to internal and external collaboration. At last, an important assumption of the matching research is that variables must be closely related and mutually reinforced (Dess, Newport, and Rasheed Citation1993). This lays the foundation for our research on the fit of internal collaboration and external collaboration as follows.

3. Research hypotheses

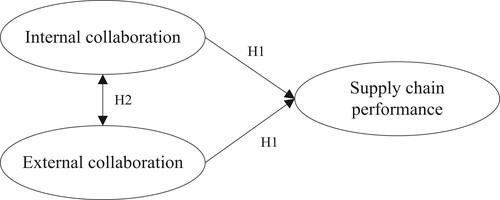

Fit in internal collaboration and external collaboration can be understood as the balance between the level of internal collaboration and external collaboration. represents the conceptual framework of the paper. The following discusses the development of the hypotheses.

3.1. The level of internal and external collaboration and supply chain performance

The empirical results of the effects of internal and external collaboration on supply chain performance are mixed. For example, some researchers have found negative effects of supplier integration on performance (Narasimhan, Swink, and Viswanathan Citation2010), while others have been unable to confirm significant relationships between them (Flynn, Huo, and Zhao Citation2010). Nevertheless, some scholars have emphasised the positive role of supply chain collaboration in firm performance (Cao and Zhang Citation2011; Wu and Chiu Citation2018; Ahmed et al. Citation2019). For example, Mishra and Shah (Citation2009) found that external and internal collaboration (i.e. supplier engagement, customer engagement and cross-functional engagement) can directly improve project performance and indirectly improve market performance. Sudusinghe and Seuring (Citation2022) performed a systematic literature review to examine how internal and external collaboration may improve sustainability performance in supply chains. Internal collaboration capacitates cross-functional knowledge sharing (Caridi, Pero, and Sianesi Citation2012), and helps to smooth the supply chain process by the way of eliminating wasteful procedures and avoiding delays and blockages (Turkulainen and Ketokivi Citation2012). Shukor et al. (Citation2020) suggested that strong relationships exist between customer, supplier (external collaboration), internal integration (internal collaboration), and supply chain performance according to agility and flexibility. Wong, Wong, and Boon-Itt (Citation2020) also verified different effects of internal and external collaboration on improving performance. Efficient internal collaboration improves the ability to respond to information produced beyond the firm. External collaboration helps coordinate tasks and solve problems (Ragatz, Handfield, and Peterson Citation2002), improve product quality (Rosenzweig, Roth, and Dean Citation2003), reduce the lead time (Sherman, Souder, and Jenssen Citation2000), enhance flexibility and ensure delivery (Schoenherr and Swink Citation2012). Through internal and external collaboration, supply chain members are more capable of understanding each other, realising customer value (Zhong, Ma, and Tu Citation2016), reducing uncertainties, and achieving collaborative satisfaction and performance among better-performing firms (Nyaga, Whipple, and Lynch Citation2010). On these grounds, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H1: The level of internal collaboration and external collaboration positively affect supply chain performance.

3.2. The relationship between internal and external collaboration

Based on an extensive view on the literature, we find that there has been no consensus on the relationship between internal collaboration and external collaboration to date. The relevant viewpoints are as follows:

Internal collaboration has an impact on external collaboration. Koufteros, Rawski, and Rupak (Citation2010) validated that internal integration affects external integration. Wang et al. (Citation2015) believed that information and relational capabilities within a firm positively affect the effectiveness of external collaboration. External collaboration also has an impact on internal collaboration. Sanders and Premus (Citation2005) confirmed that external collaboration has a directly positive effect on internal collaboration through the development and adoption of information technology. Forgionne and Guo (Citation2009) proposed that the coordination of the various decisions within firms along the supply chain can facilitate system planning, management and control. Stank, Keller, and Daugherty (Citation2001) validated that there is a significant correlation between internal collaboration and external collaboration. Vickery et al. (Citation2003) assumed that intra-firm and inter-firm collaboration are equally emphasised under an integrated supply chain strategy.

Firms are likely to achieve external collaboration on the basis of the achievement of internal collaboration (Flynn, Huo, and Zhao Citation2010). Gimenez (Citation2006) argued that external collaboration is a state emerged as an outcome of internal collaboration. For that matter, firms are supposed to achieve internal collaboration firstly in order to enhance external collaboration. On the other hand, by communicating with customers and suppliers, firms learn collaborative skills by which they are able to further promote internal collaboration (Sanders and Premus Citation2005). Stank, Keller, and Daugherty (Citation2001) affirmed that external information beyond the company is the generative force of effective internal systems.

Some studies ascertained the positive interactive effect between internal and external collaboration on supply chain performance (Droge, Jayaram, and Vickery Citation2004; Boon-itt and Wong Citation2011). Others verified the positive influence of interaction between external collaboration on performance (Flynn, Huo, and Zhao Citation2010; Danese and Romano Citation2011). In summary, most of the studies argue that internal collaboration leads to external collaboration; however, only few studies argue the vice versa. We believe that internal collaboration and external collaboration are likely to co-influence each other. If internal collaboration is not conducted properly, firms are not able to effectively turn external collaboration into performance improvement; and without the collaboration of customers and suppliers (external collaboration), the efficiency of product creation and design (internal collaboration) may decrease. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

H2: Internal collaboration and external collaboration co-influence each other.

3.3. The fit of internal and external collaboration and supply chain performance

When the levels of internal collaboration and external collaboration are high, optimal performance can be achieved (Hillebrand and Biemans Citation2003; Flynn, Huo, and Zhao Citation2010). Frohlich and Westbrook (Citation2001) indicated that the width of the customer and supplier integration is positively correlated to operational performance according to the concept of the ‘arc of integration’. However, their study focused only on supplier integration and customer integration (external collaboration), excluding internal collaboration. The interaction between internal and external collaboration enables the firm to efficiently internalise external information and effectively respond to customer requirements by utilising internal information and absorbing external information. Flynn, Huo, and Zhao (Citation2010) developed taxonomy of internal and external collaboration in terms of their integration strength and balance. Wong, Wong, and Boon-itt (Citation2013) investigated whether complementary internal collaboration and external collaboration are positively correlated with product innovation. Internal and external integration should be jointly used to achieve collaborative effects to improve performance (Droge, Jayaram, and Vickery Citation2004). Shou et al. (Citation2018) observed that the overall inter-organisational fit is positively related to firms’ environmental innovation outcomes.

In summary, firms with a higher level of external collaboration and internal collaboration are likely to achieve better performance, but the fit between them should also be considered. A firm is considered to have a high–high fit when it presents high levels of both internal collaboration and external collaboration, while firms with low levels of both internal and external collaboration are considered to have a low–low fit (Luo and Yu Citation2016; Zimmermann et al. Citation2021). On the basis of fit theory, we believe that although internal collaboration and external collaboration are both important in the pursuit of supply chain performance, what matters more is they should fit each other. This is because the fit or alliance between internal and external collaboration can generate lasting competitive advantages on supply chain (Clinton and Morash Citation2015), which are particularly difficult to duplicate as competitors need to both obtain the complementary resources and replicate their disposition (Holcomb, Holmes, and Hitt Citation2006). Therefore, the high–high fit in internal and external collaboration is likely to lead to the higher level of performance along supply chain. On these grounds, we propose the following hypothesis:

H3: The fit between internal and external collaboration is positively related to supply chain performance.

4. Research methodology

4.1. Measures

The questionnaire was adapted from the literature. A 7-point Likert scale was used with 1 denoting strong disagreement and 7 denoting strong agreement. After completing the questionnaire design, we invited 20 senior supply chain managers, professors specialising in SCM and MBA students to participate in the pilot study to test the validity of the questionnaire. The scale is revised based on the interview feedback and pilot study results to render the questionnaire more suitable for Chinese companies. The final measurement items are shown in Appendix A.

Internal and external collaboration defines all cross-functional departments and all partners actively working together towards common objectives. Internal collaboration allows these functions/departments to work together effectively (Lai et al. Citation2012) for combined decision-making (Stank, Keller, and Daugherty Citation2001) and joint knowledge creation (Cao and Zhang Citation2011). External collaboration involves the process of joint decision-making among interdependent supply chain partners (Stank, Keller, and Daugherty Citation2001). The measurement items are adapted from the instrument developed by Tan, Lyman, and Wisner (Citation2002) and Wu and Chiu (Citation2018), including five items for internal collaboration, and five items for external collaboration.

Supply chain performance is the performance output of node enterprises along the supply chain according to reliability, response speed, customer service level, and accessibility (Vachon and Klassen Citation2008). Beamon (Citation1999) presents an overview of the measures of supply chain performance, identifying three necessary components: resources, output and flexibility. In addition, the environmental performance has also become an important indicator of supply chain performance in more recent studies (Zhu, Sarkis, and Lai Citation2008; Backstrand and Fredriksson Citation2020; Jia et al. Citation2020; Chen et al. Citation2021). This paper refers to Beamon (Citation1999) and Zhu, Sarkis, and Lai (Citation2008) in its selection of resources, output, flexibility and environmental performance to evaluate supply chain performance.

Three types of control variables are considered in this study, i.e. firm size, ownership, and industry. First, large companies have more resources than small companies to invest in supply chain collaboration and thereby obtain better supply chain performance. According to Flynn, Huo, and Zhao (Citation2010), the total number of employees is often used as the proxy of firm size. Second, different forms of ownership should generate different supply chain networks, which have an impact on supply chain performance. Forms of ownership include state-owned enterprises, private enterprises, collectively owned enterprises, Sino-foreign joint ventures, and foreigner-owned enterprises (Flynn, Huo, and Zhao Citation2010). Third, different industries have different priorities when solving problems; for example, industrial enterprises may focus on raw material supplies, while service enterprises are more focused on customer needs. The industries that we surveyed include food and beverages, textiles and apparel, chemical and petroleum production, machinery, plastics and rubber, and tourism.

4.2. Sampling and data collection

Enterprises with upstream and downstream business relationships were selected from the provinces of Guangdong, Guangxi, Fujian, Zhejiang and Jiangsu in Southeast China. These enterprises cover a wide variety of industries. The questionnaire was mainly distributed for on-site completion and via e-mail. The respondents were familiar with the management of internal processes and of their external suppliers and customers. The supply chain managers, CEOs and senior managers were randomly selected for sampling, with professional duties including procurement, sales and supplier and customer management.

Our team members spent four months (i.e. from March to June 2020) in collecting data and processing the survey results. The team members included senior undergraduates and graduate students majoring in business management, who were trained by the lead academic of the project. The questionnaire began with a cover letter that explained the purpose of the investigation and guaranteed the confidentiality of respondents’ responses and their anonymity.

A total of 403 questionnaires from 1009 respondents were received. Among these questionnaires, 205 were valid, implying a valid response rate of 20.3%. The profiles of the respondents’ enterprises are shown in .

Table 1. Main demographics of the samples.

4.3. Nonresponse bias, common method bias

Nonresponse bias was estimated by comparing early responses with later responses in terms of the length of time that it took to complete and return a questionnaire (Mentzer and Lambert Citation2015). The two-sample t-test indicates no significant differences between the two groups. The chi-square test was used to examine the demographics of the enterprises in terms of size and ownership. The results also indicate no significant differences between the two groups, indicating that nonresponse bias does not seem to be a main problem in this study.

Further, we conducted surveys via on-site and e-mail questionnaires. A comparative analysis of the two questionnaires through correlation analysis was conducted, with the results indicating no significant difference between the two.

Harman’s single-factor test was utilised to test common method variance (CMV) (Podsakoff and MacKenzie Citation2003). Principal component analysis was performed on all of the factors. All of the constructs were extracted as different factors, with 90.91% of the total variance explained by the factor solution, and 33.4% of the variance explained by the first factor. The results of the study were not significantly affected by homologous data; hence, there is no evidence of common method bias. Furthermore, referred to Lindell and Whitney (Citation2001), firm size as a marker variable is used in this study, which is one that is theoretically unrelated to the dependent variables. And it is embraced in the questionnaire to test for potential CMV. The results indicate that the firm size is not significantly correlated to any of the variables, which further proves that CMV had little effect on our research.

4.4. Reliability and validity

Partial least squares (PLS) have obvious advantages in handling small samples, analysing complex models and guaranteeing the predictive ability of the model (Chin Citation1998). Our sample size of 205 is insufficient if a covariance-based structural equation modelling method is used, but is sufficient if PLS is used (Peng and Lai Citation2012; Benitez et al. Citation2020). In order to evaluate the significance of the factor loading of each scale in the measurement model and the significance of the path coefficients in the structural model, a bootstrapping estimation procedure is used. The procedure produces 1000 random samples, each sample with a size of 205 (the same size as the original sample) (Peng and Lai Citation2012).

The measurement scales used in this empirical study were adapted from the maturity scale in the corresponding literature to ensure content validity. Cronbach’s alpha was adopted to assess construct reliability. All of the values in are greater than the generally agreed-on lower limit of 0.70, showing that all of the constructs are reliable.

Table 2. Cronbach’s alpha, AVE, CR and collinearity statistics.

Confirmatory factor analysis was conducted via PLS to evaluate the reliability and validity of the measurement scale (Fornell and Larcker Citation1981). The factor loadings and t-values are shown in Appendix A; all of the factor loadings exceed 0.5. As shown in , the average variance extracted (AVE) values exceed 0.50, and the composite reliability values are greater than 0.80. All of the above outcomes confirm the unidimensionality of the measurement scale. Next, as shown in Appendix A, all of the t-values are larger than 2.58 at p < 0.01, indicating that convergent validity is obtained. Further, the square root of the AVE for each construct (as presented in , in bold) is larger than its corresponding correlations with all of the other constructs, indicating that discriminant validity is satisfactory.

Table 3. Correlations, and the square roots of AVEs.

In addition, the variance inflation factor (VIF) was used to examine all of the constructs in our model for multicollinearity. As shown in , the VIFs are all less than the threshold value of 10 (Hair et al. Citation2011).

5. Results and analysis

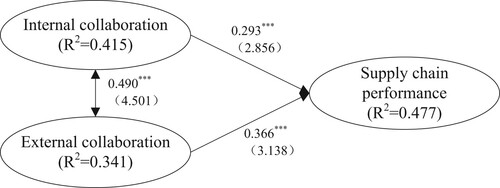

We used PLS to estimate the relationships among different constructs with the R package [plspm]. In conducting the model estimation, the procedure advocated by Peng and Lai (Citation2012) was followed. The global goodness of fit (GoF) index is an important indicator to measure the goodness of fit of PLS-SEM models. Based on , the GoF value of our model was 0.495 – greater than the marginal value of 0.36. This result indicates that our model is acceptable for further discussion.

Moreover, the explained variance (R2) values, representing the predictive power of the structural models, were computed for all of our constructs. These values also signify the amount of variance explained by the independent variances under the condition of multiple regression results. As shown in , the R2 values of internal collaboration, external collaboration and supply chain performance are 0.415, 0.341 and 0.447, respectively, which are classified as moderately strong (Chin Citation1998).

The results of the PLS analysis are illustrated in . All of the standardised coefficients are shown to be significant at the 0.001 level, thus supporting Hypotheses 1 and 2.

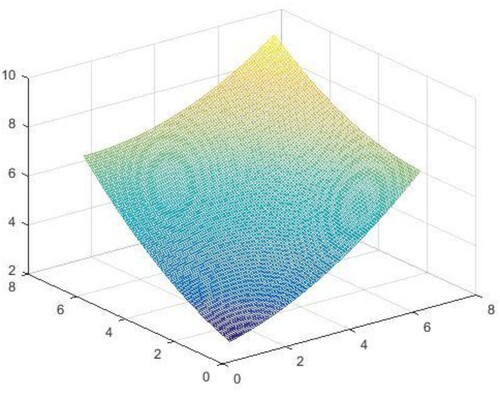

In order to test hypothesis 3, polynomial regression and response surface methodology are used. Polynomial regression can effectively overcome the shortcomings of the difference score method, and can better characterise the interaction (Edwards and Parry Citation1993). Intuitive and clear 3D response surface maps and important feature data estimates of the response surfaces and response surface methodology allowed us to mine deeper and more complex 3D relationships. The control variables are recoded to generate dummy variables and then are incorporated into the model. For example, ownership is coded as a variable O with values 1, 2, 3, 4, respectively. Here, Model 1 contains only the control variables, while Model 2 adds the independent variables of internal collaboration and external collaboration, and the quadratic terms (i.e.,

and

interaction in ) are added to Model 3. For the full data, the polynomial regression results are shown in . From the regression results of Model 3, we can conclude that Model 3 is significant at

(

). Internal collaboration and its quadratic term, external collaboration and its quadratic term, and the interaction term have a strong effect on supply chain performance. The coefficients are 0.225 (

), 0.080 (

), 0.307 (

), 0.069 (

) and −0.056 (

), respectively. Additionally, the high-order terms are not significant. Thus, internal collaboration and external collaboration should fit each other. This finding is consistent with the views of Griffith and Myer (Citation2005).

Table 4. Results of polynomial regression.

Response surface methodology was used to explain and clarify the results of the polynomial regression (see ). In line with Edwards and Parry (Citation1993), the stationary point of the response surface is which is immediately beyond the back edge of the X, Y plane. The curvature along this line is calculated as 0.103. The slight upward curvature along the

line indicates that as internal collaboration and external collaboration both increase, supply chain performance will increase.

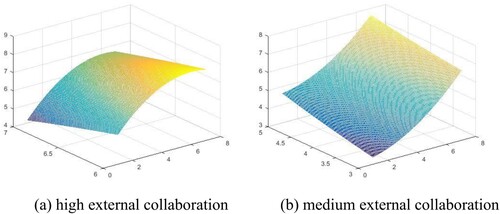

However, surprisingly, supply chain managers often believe that their firms are more experienced in external collaboration efforts than they are in internal collaboration efforts (Poirier, Swink, and Quinn Citation2008). However, internal collaboration is as important as external collaboration (Wong, Wong, and Boon-itt Citation2013). And by gradually strengthening supplier integration, the law of diminishing marginal returns begins to take effect, and the difficulty of exploring high-performance activities increases (Das, Narasimhan, and Talluri Citation2006). Therefore, to validate this conclusion, we divided the sample into three sub-samples based on their factor scores for external collaboration via cluster analysis – high external collaboration for interval [5–8), medium external collaboration for interval [3–5) and low external collaboration for interval [1–3); the sample sizes were 43, 115 and 47, respectively. Similarly, polynomial regression and response surface methodology were used. The results of the polynomial regression are shown in .

Table 5. Results of polynomial regression in the case of different levels of external collaboration.

From the regression results of Model 3 in Column 4, , we can conclude that Model 3 is significant at p < 0.001(F = 25.266) under high external collaboration. We can also conclude that significant terms exist (internal and external collaboration and their squared terms are significant at the 0.05 level) and that higher-order terms are not significant. As shows, in the case of high external collaboration, when both internal collaboration and external collaboration increase to a large degree, supply chain performance reaches a maximum. However, as the level of collaboration increases further, supply chain performance tends to decline slowly. This finding validates Das, Narasimhan, and Talluri’s (Citation2006) perspective. In addition, firms can explore and exploit external resources, but if internal collaboration is relatively low, and then such resources cannot be effectively internalised transformed into performance (see ).

Figure 4. Performance implications of the fit of internal and external collaboration. (a) High external collaboration. (b) Medium external collaboration.

In the case of medium external collaboration, internal collaboration and external collaboration fit each other and have a positive correlation with supply chain performance. Nevertheless, in the case of low external collaboration, there is no significant relationship between external collaboration and supply chain performance, and the quadratic terms are not significant, as shown in Columns 8 and 9, . This shows that even though internal collaboration is high, lower external collaboration will not result in better supply chain performance. This may be because information produced beyond the firm is the reason grounds of efficient and effective system (Stank, Keller, and Daugherty Citation2001). Although internal collaboration may function as a prerequisite for external collaboration (Zhao et al. Citation2011), without effective external collaboration, effort to improve supply chain performance may be of limited value.

6. Discussion and implications

6.1. Discussion

The results show that all of the hypotheses are supported. First, our findings indicate that internal collaboration and external collaboration have a direct impact on supply chain performance. This is in line with the existing research on supply chain collaboration that internal and external collaboration is significantly related to supply chain performance (e.g. Droge, Jayaram, and Vickery Citation2004; Flynn, Huo, and Zhao Citation2010). By empirically verifying this, our study highlights the significance of internal and external collaboration in improving supply chain performance.

Second, our results reveal that internal collaboration and external collaboration can influence each other. This echoes the study of Hillebrand and Biemans (Citation2003) that internal collaboration is the requirement for effective learning and cooperation from external collaboration. According to constructive learning theory (Hein Citation1991), learning is a process of knowledge internalisation (i.e. the internally collaborative diffusion of knowledge across departments within a firm), which is realised through external collaboration (i.e. acquiring knowledge from external partners); it is also a process of externalisation (i.e. the diffusion of knowledge to supply chain members through external collaboration), which is enabled by internal collaboration (i.e. training is provided by internal cross-functional teams). Also, there is an interactive effect between internal collaboration and external collaboration on supply chain performance. This further verifies Droge, Jayaram, and Vickery’s (Citation2004), in which the interaction of internal and external integration is significantly correlated to performance.

Third, the fit approach reveals that the effect of supply chain collaboration is cumulative, and supply chain performance can be maximised when supply chain member companies achieve a high degree of internal and external collaboration synchronously. This finding is consistent with the conceptual proposition in Hillebrand and Biemans (Citation2003); here we further provide the empirical evidence. Moreover, we found that improvement in internal and external collaboration does not always lead to improved supply chain performance. Once a certain threshold value of internal and external collaboration is achieved, further enhancement in internal and external collaboration will cause the decline of supply chain performance. This stands in contrast to the findings in Flynn, Huo, and Zhao (Citation2010) that the higher uniformed internal and external collaboration, the better supply chain performance. Instead, our findings suggest the existence of an optimal fit level of internal and external collaboration in the pursuit of supply chain performance.

Specifically, in the case of the low range (1–3, ) of external collaboration, the impact of external collaboration is less than that of internal collaboration on supply chain performance, and the interactional effect of internal and external collaboration on supply chain performance is not significant. This finding indicates that when the development of SCM is at a relatively early stage, external collaboration does not have a strong role to play. This may be due to the low level of professionalism in SCM and insufficient support of the overall supply chain function. Saeed, Malhotra, and Grover (Citation2005) also pointed out that only a higher level of external collaboration beyond a simple procurement system could help companies to improve efficiency. When the level of external collaboration is low, suppliers cannot obtain customer demand information in a timely manner and therefore, are unable to provide satisfactory services to customers, which leads to poor supply chain performance.

In the case of the medium range (3–5 in (b)) of external collaboration, with a higher fit level of internal collaboration and external collaboration (i.e. the closeness of the two numbers), better supply chain performance can be reached. In the case of the high range (5–8 in (a)) of external collaboration, as the fit level (i.e. the closeness of the two numbers) increases, supply chain performance improves. However, after the performance reaches a high point (e.g. 7), it tends to slowly decline. With the gradual strengthening of internal and external collaboration, the law of diminishing marginal returns comes into play, and the difficulty of exploring activities that improve supply chain performance increases, the transaction costs that come with it also increase, hence, there is a turning point that performance begins to change. This outcome indicates that not all firms implementing supply chain collaboration can attain their desired goals. In order to get higher performance, firms along the supply chain need to balance their levels of internal and external collaboration.

In addition, the development of the hypotheses and the analyses of the results are supported by contingency theory and the resource-based view, which have been applied in the study of different kinds of strategic fit in recent years. The two theories were used in a complementary way, as contingency theory suggests that the internal and the external of companies must be harmonised in order to favour performance, while the resource-based view supports the concept that the internal and external resources of companies are the key sources for them to obtain sustained competitive advantage.

6.2. Managerial implications

This study also suggests the following implications for managers. First, firms along supply chain should attach importance to internal and external collaboration to improve efficiency and performance. When selecting supply chain partners, firms should evaluate potential partners in terms of strategic goal congruence, resource complementarity, and cultural compatibility. Firms can achieve efficiency if they can design efficient internal processes and alight their own processes with those of partners. In our survey, we found that supply chain collaboration consumes a large amount of resources in the optimisation of production operations, and this process will inevitably result in costs. Therefore, firms should analyse the market environment and their own development needs, and communicate with suppliers when collaborating.

Second, managers are encouraged to pay attention to the fit between internal and external collaboration since this is crucial to supply chain performance. From the strategic viewpoint, the decision on the fit level of internal and external collaboration is directly associated with performance outcomes. Companies need to understand their own situation and adopt the appropriate internal and external collaboration to achieve superior performance. The results can be used to help managers select different scenarios of fit. Firms should also contingently select an appropriate level of internal and external collaboration given resource constraints, bearing in mind that too much is as bad as too little when implementing supply chain collaboration. If the supply chain members are blindly involved in collaboration activities and adopt an integration approach without considering the fit between internal and external collaboration, it is likely to weakened firm’s and supply chain performance. Only if the levels of internal and external collaboration are balanced, and are at a moderate to upper level, can the supply chain performance is best promoted.

7. Conclusion

This study demonstrates the role of internal and external collaboration in improving supply chain performance. More importantly, our study highlights that the fit of internal and external collaboration is crucial to supply chain performance. Our study makes the following contributions to the supply chain collaboration literature. First, we investigated the fit of internal and external collaboration on supply chain performance under different levels of external collaboration and proposed that improvements in internal and external collaboration will not lead to improved supply chain performance when the level of external collaboration is low. Improvements in internal and external collaboration will lead to improved supply chain performance when the level of external collaboration is high; however, after performance reaches a certain point, it tends to slowly decline as the fit level continues to increase.

Second, applying the fit theory in the supply chain collaboration literature, this study provides empirical evidence for Hillebrand and Biemans (Citation2003) proposition that supply chain performance reaches its maximum level when supply chain companies maintain a high degree of both internal and external collaboration. However, this study goes beyond Hillebrand and Biemans (Citation2003) and Flynn, Huo, and Zhao’s (Citation2010) findings and finds that the fit between internal and external collaboration will not necessarily lead to improved supply chain performance in the scenarios of the low range (i.e. 1–3) and the high range (i.e. 5–8) of external collaboration.

This study has limitations. First, cross-sectional data are used in this study, limiting the predictability of results over time. Future studies could use panel data to explore the antecedents and consequences of supply chain collaboration if available. Second, this study uses data obtained from individual firms to examine the relationships pertaining to supply chain coordination. Further research could take a supplementary dyadic approach involving both suppliers and customers. Finally, the context for the study is China, and datasets from different countries may produce different results.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (15.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahmed, M. U., M. M. Kristal, M. Pagell, and T. F. Gattiker. 2019. “Building High Performance Supply-Chain Relationships for Dynamic Environments.” Business Process Management Journal 26 (1): 80–101.

- Amhalhal, A., J. Anchor, N. S. Tipi, and S. Elgazzar. 2021. “The Impact of Contingency Fit on Organisational Performance: An Empirical Study.” International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management. doi:10.1108/IJPPM-01-2021-0016.

- Anthony, T. 2000. “Supply Chain Collaboration: Success in the new Internet Economy.” Achieving Supply Chain Excellence Through Technology 2: 41–44.

- Backstrand, J., and A. Fredriksson. 2020. “The Role of Supplier Information Availability for Construction Supply Chain Performance.” Production Planning and Control. doi:10.1080/09537287.2020.1837933.

- Barratt, M. 2004. “Understanding the Meaning of Collaboration in the Supply Chain.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 9 (1): 30–42.

- Beamon, B. M. 1999. “Measuring Supply Chain Performance.” International Journal of Operation & Production Management 19 (3): 275–292.

- Benitez, J., J. Henseler, A. Castillo, and F. Schuberth. 2020. “How to Perform and Report an Impactful Analysis Using Partial Least Squares: Guidelines for Confirmatory and Explanatory IS Research.” Information & Management 57 (2): 103–168.

- Boon-itt, S., and C. Y. Wong. 2011. The Interactions Between Internal and External Integration and Their Combined Effects on Operational Performance. POMS 22nd Conference Reno, USA. Paper No. 020-0296.1-20.

- Cao, M., and Q. Zhang. 2011. “Supply Chain Collaboration: Impact on Collaborative Advantage and Firm Performance.” Journal of Operations Management 29 (3): 163–180.

- Caridi, M., M. Pero, and A. Sianesi. 2012. “Linking Product Modularity and Innovativeness to Supply Chain Management in Italian Furniture Industry.” International Journal of Production Economics 136 (1): 207–217.

- Chen, L., F. Jia, T. Li, and T. Zhang. 2021. “Supply Chain Leadership and Firm Performance: A Meta-Analysis.” International Journal of Production Economics 235: 108082.

- Chen, P. K., and Y. Ye. 2020. “Implementation Strategy of Environmental Management Systems in Supply Chains.” Production Planning and Control 3: 1–12.

- Cheng, Y., A. Chaudhuri, and S. Farooq. 2016. “Interplant Coordination, Supply Chain Integration, and Operational Performance of a Plant in a Manufacturing Network: A Mediation Analysis.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 21 (5): 550–568.

- Chin, W. W. 1998. “The Partial Least Squares Approach for Structural Equation Modelling.” In Modern Methods for Business Research, edited by G. A. Marcoulides, 295–336. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Chowdhury, N. A., S. M. Ali, S. K. Paul, Z. Mahtab, and G. Kabir. 2020. “A Hierarchical Model for Critical Success Factors in Apparel Supply Chain.” Business Process Management Journal 26 (7): 1761–1788.

- Clinton, S. R., and E. A. Morash. 2015. Relationship Marketing: International Comparisons of Channel and Logistical Integration Interfaces. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Danese, P., M. Molinaro, and P. Romano. 2020. “Investigating Fit in Supply Chain Integration: A Systematic Literature Review on Context, Practices, Performance Links.” Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 26 (5): 100634.

- Danese, P., and P. Romano. 2011. “Supply Chain Integration and Efficiency Performance: A Study on the Interactions Between Customer and Supplier Integration.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 16 (4): 220–230.

- Das, A., R. Narasimhan, and S. Talluri. 2006. “Supplier Integration – Finding an Optimal Configuration.” Journal of Operations Management 24 (5): 563–582.

- Dess, G. C., S. Newport, and A. M. Rasheed. 1993. “Configuration Research in Strategic Management: Key Issues and Suggestions.” Journal of Management 19 (4): 775–795.

- Droge, C., J. Jayaram, and S. K. Vickery. 2004. “The Effects of Internal Versus External Integration Practices on Time-Based Performance and Overall Firm Performance.” Journal of Operations Management 22 (6): 557–573.

- Duhamel, F., V. Carbone, and V. Moatti. 2016. “The Impact of Internal and External Collaboration on the Performance of Supply Chain Risk Management.” International Journal of Logistics Systems and Management 23 (4): 534–557.

- Duong, L. N. K., and J. Chong. 2020. “Supply Chain Collaboration in the Presence of Disruptions: A Literature Review.” International Journal of Production Research 58 (11): 3488–3507.

- Edwards, J. R., and M. E. Parry. 1993. “On the Use of Polynomial Regression Equations as an Alternative to Difference Scores in Organizational Research.” Academy of Management Journal 36 (6): 1577–1613.

- Fawcett, S. E., A. M. Fawcett, B. J. Watson, and G. M. Magnan. 2012. “Peeking Inside the Black Box: Toward an Understanding of Supply Chain Collaboration Dynamics.” Journal of Supply Chain Management 48 (1): 44–72.

- Feng, T., Y. Jiang, and D. Xu. 2020. “The Dual-Process Between Green Supplier Collaboration and Firm Performance: A Behavioural Perspective.” Journal of Cleaner Production 260: 121073.

- Fisher, C. D. C. 1997a. “Comparing the Fit of Stratigraphic and Morphologic Data in Phylogenetic Analysis.” Paleobiology 23 (1): 1–19.

- Flynn, B. B., B. Huo, and X. Zhao. 2010. “The Impact of Supply Chain Integration on Performance: A Contingency and Configuration.” Journal of Operations Management 28 (1): 58–71.

- Flynn, B., X. Koufteros, and G. Lu. 2016. “On Theory in Supply Chain Uncertainty and its Implications for Supply Chain Integration.” Journal of Supply Chain Management 52 (3): 1–46.

- Forgionne, G., and Z. Guo. 2009. “Internal Supply Chain Coordination in the Electric Utility Industry.” European Journal of Operational Research 196 (2): 619–627.

- Fornell, C., and D. F. Larcker. 1981. “Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error.” Journal of Marketing Research 24 (2): 337–346.

- Frohlich, M., and R. Westbrook. 2001. “Arcs of Integration: An International Study of Supply Chain Strategies.” Journal of Operations Management 19 (2): 185–200.

- Gimenez, C. 2006. “Logistics Integration Processes in the Food Industry.” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 36 (3): 231–249.

- Gligor, D. M. 2017. “Re-examining Supply Chain Fit: An Assessment of Moderating Factors.” Journal of Business Logistics 38 (4): 253–265.

- Gligor, D. M., C. L. Esmark, and M. C. Holcomb. 2015. “Performance Outcomes of Supply Chain Agility: When Should You Be Agile?” Journal of Operations Management 33–34: 71–82.

- Griffith, A. D., and M. B. Myer. 2005. “The Performance Implications of Strategic Fit of Relational Norm Governance Strategies in Global Supply Chain Relationships.” Journal of International Business Studies 36 (3): 254–269.

- Grotsch, V. M., C. Blome, and M. C. Schleper. 2013. “Antecedents of Proactive Supply Chain Risk Management a Contingency Theory Perspective.” International Journal of Production Research 51 (10): 2842–2867.

- Gunasekaran, A., N. Subramanian, and S. Rahman. 2015. “Green Supply Chain Collaboration and Incentives: Current Trends and Future Directions.” Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review 74: 1–10.

- Hair, J. F., B. Black, J. B. Babin, and R. E. Anderson. 2011. Multivariate Data Analysis. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Hein, G. E. 1991. Constructivist Learning Theory. New York, NY: Springer US.

- Hillebrand, B., and W. G. Biemans. 2003. “The Relationship Between Internal and External Cooperation: Literature Review and Propositions.” Journal of Business Research 56 (9): 735–743.

- Holcomb, T. R., R. M. Holmes, and M. A. Hitt. 2006. “Diversification to Achieve Scale and Scope: The Strategic Implications of Resource Management for Value Creation.” In Ecology and Strategy, edited by J. A. C. Baum, S. D. Dobrev, and A. Van Witteloostuijn, 549–587, Vol. 23. Advances in Strategic Management. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Hong, P., W. J. Doll, E. Revilla, and A. Y. Nahm. 2011. “Knowledge Sharing and Strategic Fit in Integrated Product Development Projects: An Empirical Study.” International Journal of Production Economics 132: 186–196.

- Jia, F., S. Yin, L. Chen, and X. Chen. 2020. “The Circular Economy in the Textile and Apparel Industry: A Systematic Literature Review”.” Journal of Cleaner Production 259: 1–17.

- Kim, W. S. 2009. “An Investigation on the Direct Effect of Supply Chain Integration of Firm Performance.” International Journal of Production Economics 119: 328–346.

- Koufteros, X. A., G. E. Rawski, and R. Rupak. 2010. “Organizational Integration for Product Development: The Effects on Glitches, on-Time Execution of Engineering Change Orders, and Market Success.” Decision Sciences 41 (1): 49–80.

- Lai, F., M. Zhang, D. Lee, and X. Zhao. 2012. “The Impact of Supply Chain Integration on Mass Customization Capability: An Extended Resource-Based View.” IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 59 (3): 443–456.

- Laosirihongthong, T., D. Prajogo, and I. D. Adebanjo. 2014. “The Relationships Between Firm’s Strategy, Resources and Innovation Performance: Resources-Based View Perspective.” Production Planning and Control 25 (15): 1231–1246.

- Lee, H. L. 2002. “Aligning Supply Chain Strategies with Product Uncertainties.” California Management Review 44 (3): 105–119.

- Liao, Y., and Y. Li. 2019. “Complementarity Effect of Supply Chain Competencies on Innovation Capability.” Business Process Management Journal 25 (6): 1251–1272.

- Lindell, M. K., and D. J. Whitney. 2001. “Accounting for Common Method Variance in Crosssectional Designs.” Journal of Applied Psychology 86 (1): 114–121.

- Luo, B. N., and K. Yu. 2016. “Fits and Misfits of Supply Chain Flexibility to Environmental Uncertainty: Two Types of Asymmetric Effects on Performance.” The International Journal of Logistics Management 27 (3): 862–885.

- Mentzer, J. T., and D. M. Lambert. 2015. “Estimating Nonresponse Bias in Mail Surveys: A Replication Study.” In Marketing Horizons: A 1980's Perspective. Developments in Marketing Science: Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Science, edited by V. Bellur. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Miller, D. 1992. “Environmental Fit Versus Internal Fit.” Organization Science 3 (2): 159–178.

- Min, S., J. T. Mentzer, and R. T. Ladd. 2007. “A Market Orientation in Supply Chain Management.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 35 (4): 507–522.

- Min, S., A. S. Roath, P. J. Daugherty, S. E. Genchev, H. Chen, A. D. Arndt, and R. G. Richey. 2005. “Supply Chain Collaboration: What's Happening?” The International Journal of Logistics Management 16 (2): 237–256.

- Mishra, A. A., and R. Shah. 2009. “In Union Lies Strength: Collaborative Competence in New Product Development and its Performance Effects.” Journal of Operations Management 27 (4): 324–338.

- Moshtari, M. 2016. “Inter-organizational Fit, Relationship Management Capability, and Collaborative Performance Within a Humanitarian Setting.” Production and Operations Management 25 (9): 1542–1557.

- Murphy, L. E., and J. P. Coughlan. 2018. “Does It Pay to Be Proactive? Testing Proactiveness and the Joint Effect of Internal and External Collaboration on Key Account Manager Performance.” Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management 38 (2): 205–219.

- Nair, A., C. Blome, T. Y. Choi, and G. Lee. 2018. “Re-visiting Collaborative Behavior in Supply Networks–Structural Embeddedness and the Influence of Contextual Changes and Sanctions.” Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 24 (2): 135–150.

- Narasimhan, R., M. Swink, and S. Viswanathan. 2010. “On Decisions for Integration Implementation: An Examination of Complementarities Between Product-Process Technology Integration and Supply Chain Integration.” Decision Science 41 (2): 355–372.

- Nyaga, G. N., J. M. Whipple, and D. F. Lynch. 2010. “Examining Supply Chain Relationships: Do Buyer and Supplier Perspectives on Collaborative Relationships Differ?” Journal of Operations Management 28 (2): 101–114.

- Peng, D. X., and F. Lai. 2012. “Using Partial Least Squares in Operations Management Research: A Practical Guideline and Summary of Past Research.” Journal of Operations and Production Management 30 (6): 467–480.

- Podsakoff, P. M., and S. B. MacKenzie. 2003. “Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies.” Journal of Applied Psychology 88 (5): 879–903.

- Poirier, C. C., M. L. Swink, and F. J. Quinn. 2008. “Sixth Annual Global Survey of Supply Chain Progress: Still Chasing the Leaders.” Supply Chain Management Review 12 (7): 26–32.

- Pradabwong, J., B. Christos, T. James, and S. P. Kulwant. 2017. “Business Process Management and Supply Chain Collaboration: Effects on Performance and Competitiveness.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 22 (2): 107–121.

- Ragatz, G. L., R. B. Handfield, and K. J. Peterson. 2002. “Benefits Associated with Supplier Integration Into new Product Development Under Conditions of Technology Uncertainty.” Journal of Business Research 55: 389–400.

- Rosenzweig, E. D., A. V. Roth, and J. W. Dean. 2003. “The Influence of an Integration Strategy on Competitive Capabilities and Business Performance: An Exploratory Study of Consumer Products Manufacturers.” Journal of Operations Management 21: 437–456.

- Sabri, Y. 2019. “In Pursuit of Supply Chain Fit.” The International Journal of Logistics Management 30 (3): 821–844.

- Saeed, K. A., M. K. Malhotra, and V. Grover. 2005. “Examining the Impact of Inter-Organizational Systems on Process Efficiency and Sourcing Leverage in Buyer-Supplier Dyads.” Decision Science 36 (3): 365–396.

- Sanders, N. R., and R. Premus. 2005. “Modeling the Relationship Between Firms IT Capability, Collaboration, and Performance.” Journal of Business Logistics 26 (1): 1–23.

- Sáenz, M. J., E. Revilla, and D. Knoppen. 2014. “Absorptive Capacity in Buyer-Supplier Relationships: Empirical Evidence of its Mediating Role.” Journal of Supply Chain Management 50 (2): 18–40.

- Schoenherr, T., and M. Swink. 2012. “Revisiting the Arcs of Integration: Cross-Validations and Extensions.” Journal of Operations Management 30 (1-2): 99–115.

- Sherman, J. D., W. E. Souder, and S. A. Jenssen. 2000. “Differential Effects of the Primary Forms of Cross Functional Integration on Product Development Cycle Time.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 17: 257–267.

- Shou, Y. Y., W. Che, J. Dai, and F. Jia. 2018. “Inter-organizational Fit and Environmental Innovation in Supply Chains: A Configuration Approach.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 38 (8): 1683–1704.

- Shukor, A. A. A., M. S. Newaz, M. K. Rahman, and A. Z. Taha. 2020. “Supply Chain Integration and its Impact on Supply Chain Agility and Organizational Flexibility in Manufacturing Firms.” International Journal of Emerging Markets 16 (8): 1721–1744.

- Soosay, C. A., and P. Hyland. 2015. “A Decade of Supply Chain Collaboration and Directions for Future Research.” Supply Chain Management: An International Journal 20 (6): 613–630.

- Stank, T. P., S. B. Keller, and P. J. Daugherty. 2001. “Supply Chain Collaboration and Logistical Service Performance.” Journal of Business Logistics 22 (1): 29–48.

- Sudusinghe, J. I., and S. Seuring. 2022. “Supply Chain Collaboration and Sustainability Performance in Circular Economy: A Systematic Literature Review.” International of Journal of Production Economics 245: 10842.

- Tan, K. C., S. B. Lyman, and J. D. Wisner. 2002. “Supply Chain Management: A Strategic Perspective.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 22 (6): 614–631.

- Turkulainen, V., and M. Ketokivi. 2012. “Cross-functional Integration and Performance: What are the Real Benefits?” International Journal of Operations and Production Management 32 (4): 447–467.

- Vachon, S., and R. D. Klassen. 2008. “Environmental Management and Manufacturing Performance: The Role of Collaboration in the Supply Chain.” International Journal of Production Economics 111 (2): 299–315.

- Venkatraman, N. 1989. “The Concept of Fit in Strategy Research – Toward Verbal and Statistical Correspondence.” Academy of Management Review 14 (3): 423–444.

- Vickery, S. K., J. Jayaram, C. Droge, and R. Calantone. 2003. “The Effect of an Integrative Supply Chain Strategy on Customer Service and Financial Performance: An Analysis of Direct Versus Indirect Relationship.” Journal of Operations Management 21 (5): 523–539.

- Wagner, S. M., P. Grosse-Ruyken, and T. F. Erhun. 2012. “The Link Between Supply Chain Fit and Financial Performance of the Firm.” Journal of Operations Management 30 (4): 340–353.

- Walker, H., S. Seuring, J. Sarkis, R. Klassen, C. Blome, A. Paulraj, and K. Schuetz. 2014. “Supply Chain Collaboration and Sustainability: A Profile Deviation Analysis.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 34 (5): 639–663.

- Wang, G., W. Dou, W. Zhu, and N. Zhou. 2015. “The Effects of Firm Capabilities on External Collaboration and Performance: The Moderating Role of Market Turbulence.” Journal of Business Research 68 (9): 1928–1936.

- Wong, C. W. Y., C. Y. Wong, and S. Boon-itt. 2013. “The Combined Effects of Internal and External Supply Chain Integration on Product Innovation.” International Journal of Production Economics 146 (2): 566–574.

- Wong, C., C. Y. Wong, and S. Boon-Itt. 2020. “Environmental Management Systems, Practices and Outcomes: Differences in Resource Allocation Between Small and Large Firms.” International Journal of Production Economics 228: 107734.

- Wu, I. L., and M. L. Chiu. 2018. “Examining Supply Chain Collaboration with Determinants and Performance Impact: Social Capital, Justice, and Technology use Perspectives.” International Journal of Information Management 39: 5–19.

- Wu, T., Y.-C. J. Wu, Y. J. Chen and M. Goh. 2014. “Aligning Supply Chain Strategy with Corporate Environmental Strategy: A Contingency Approach." International Journal of Production Economics 147: 220–229.

- Yildiz, K., and M. T. Ahi. 2020. “Innovative Decision Support Model for Construction Supply Chain Performance Management.” Production Planning and Control. doi:10.1080/09537287.2020.1837936.

- Yunus, E. N., and S. K. Tadisina. 2016. “Drivers of Supply Chain Integration and the Role of Organizational Culture: Empirical Evidence from Indonesia.” Business Process Management Journal 22 (1): 89–115.

- Zahra, S. A., and G. George. 2002. “Absorptive Capacity: A Review, Reconceptualization, and Extension.” Academy of Management Review 27: 185–203.

- Zhao, X. D., B. F. Huo, W. Selen, and J. Yeung. 2011. “The Impact of Internal Integration and Relationship Commitment on External Integration.” Journal of Operations Management 29: 17–32.

- Zheng, X., D. Li, Z. Liu, F. Jia, and B. Lev. 2021. “Willingness-to-Cede Behaviour in Sustainable Supply Chain Coordination.” International Journal of Production Economics 240: 108207.

- Zhong, J. L., Y. Z. Ma, and Y. L. Tu. 2016. “Supply Chain Quality Management: An Empirical Study.” International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 28 (11): 2446–2472.

- Zhu, Q., J. Sarkis, and K. H. Lai. 2008. “Confirmation of a Measurement Model for Green Supply Chain Management Practices Implementation.” International Journal of Production Economics 111 (2): 261–273.

- Zhu, X., Z. Zhang, X. Chen, F. Jia, and Y. Chai. 2022. “Nexus of Mixed-use Vitality, Carbon Emissions and Sustainability of Mixed-use Rural Communities: The Case of Zhejiang." Journal of Cleaner Production 330: 129766.

- Zimmermann, R., L. M. D. F. Ferreira, A. C. Moreira, A. C. Barros, and H. L. Correa. 2021. “The Impact of Supply Chain Fit on Business and Innovation Performance in Brazilian Companies.” The International Journal of Logistics Management 32 (1): 141–167.