ABSTRACT

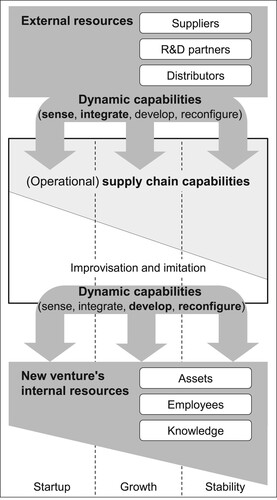

We build on dynamic capability (DC) theory and apply inductive case study research to shed light on how new venture manufacturing firms develop and nurture supply chain (SC) capabilities. Our findings discern SC capabilities related to dimensions of DCs (sense, integrate, develop, reconfigure) and show how these SC capabilities evolve throughout new venture life cycle stages. We find that SC capabilities steadily substitute improvisation and imitation. Our study also reveals that SC capabilities serve as dual-purpose capabilities with an operational as well as a dynamic role. On the one hand, they are needed to operate the supply chain and enable the development and reconfiguration of the internal resource base. On the other hand, they allow for the sensing and integration of external resources and create new or update and modify existing SC capabilities. New venture firms can benefit from our study by mimicking the development of the different SC capabilities.

1. Introduction

The goal of most (at least technology-based) new venturesFootnote1 is to grow a newly founded firm in terms of customers, employees, products, revenues, cash flows, profits and funding. Lately, the notion of ‘scaling’ was used, which practitioners describe as ‘the process of growing a venture after startup' (Shepherd and Gruber Citation2021, 968). Studies on new venture growth and scaling have primarily attempted to explain why new ventures grow and why some ventures grow faster and more successfully than others (Gilbert, McDougall, and Audretsch Citation2006; Shepherd and Patzelt Citation2022). In contrast, the understanding of how new ventures grow and scale is still limited (Gilbert, McDougall, and Audretsch Citation2006; Shepherd and Patzelt Citation2022). The ‘how’ concerns the strategies, processes and routines that new ventures apply in all functional areas of the organisation to enable the new venture’s organisation and operation to grow and expand in new markets. Shepherd and Patzelt (Citation2022), with an entrepreneurship lens on new venture growth, address the question of how knowledge management enables organisational scaling of new ventures. In our study, with an operations management (OM) lens, we aim to explore the question of how supply chain (SC) capabilities evolve and contribute to new venture growth.

It is well-established that supply chain management (SCM) is a strategic core competence creating competitive advantage and positive financial outcomes in established firms (e.g. Ellinger et al. Citation2011; Gligor et al. Citation2020; Wagner, Grosse-Ruyken, and Erhun Citation2012). Likewise, functioning supply chains and supply chain relationships are success factors and often critical bottlenecks for new venture growth (Hasan Citation2019; Song et al. Citation2008; Wagner Citation2021). The limited literature has shown, for example, that the growth of Indian high-tech manufacturing startups is inhibited by the lack of supply chain integration capabilities (upstream supply chain, production process, downstream) (Ghosh et al. Citation2018). According to Duchesneau and Gartner (Citation1990), suppliers are considered a critical success factor for new venture firms and thriving ventures rely more intensively on supplier information and assistance. Likewise, Amedofu, Asamoah, and Agyei-Owusu (Citation2019) found that four supply chain practices influence new venture firms’ ability to set up and retain relationships with satisfied customers and ensure new venture growth (customer relationship management, supplier relationship management, supply chain information quality, supply chain information sharing). While the literature underlines the criticality of supply chains and supply chain relationships, little is known about how successful entrepreneurs manage to start from a point without any operations, logistics or supply chain processes and routines and without reliable relationships with suppliers and service providers to deliver competitive products and services to customers in the years subsequent to founding (Ketchen and Craighead Citation2020; Kickul et al. Citation2011; Wagner Citation2021).

The initial work at the OM/SCM–entrepreneurship interface studying new venture firms points toward promising questions regarding OM/SCM strategies and practices (e.g. Tatikonda et al. Citation2013; Wagner Citation2021). Examples of suggested research questions are shown in .

Table 1. Exemplary research questions related to OM/SCM for new venture firms suggested in the literature.

New venture firms often operate in an emergent and rapidly changing environment. Furthermore, they might enter ambiguous markets with evolving technologies (Santos and Eisenhardt Citation2009). Similarly, the new venture’s organisational boundaries and operational SC capabilities might not yet be defined. Hence, Sebastiao and Golicic (Citation2008) recommend that new venture firms follow an ‘emergent supply chain strategy' which ‘focuses on achieving market legitimacy and becoming the cognitive referent (market claiming) while simultaneously engaging in continuous experimentation to maximise flexibility and facilitate an iterative process of value proposition refinement (market demarcating)' (81). Sebastiao and Golicic (Citation2008) suggest, in turn, that dynamic capability (DC) theory is suitable for theorising about emergent supply chain strategies. But the authors did not further expound on how operational SC capabilities or DCs develop throughout the growth of the new venture firm.

The rich stream of literature on DCs holds promising answers to how new ventures successfully expand, change, and reconfigure their initial resource base into an established firm (Zahra, Sapienza, and Davidsson Citation2006). DC theory is concerned with how existing (ordinary, operational) capabilities convert over time to accommodate the emergence and change in firms’ environment (Teece, Pisano, and Shuen Citation1997) because DCs ‘enable the firm to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external resources to maintain leadership in continually shifting business environments' (Teece Citation2014, 329).

Taken together, our study builds on (1) the literature on SCM at new venture firms, (2) prior studies on new venture life cycle stages, and (3) DC theory to explore how operational SC capabilities evolve and contribute to new venture growth by bridging external resources to supply chain partners in order to augment the new venture’s internal resource base. A better understanding of the evolution of operational and dynamic capabilities throughout the new venture life cycle will enable new venture firms to more purposefully and targeted nurture these capabilities and ultimately enhance the supply chain performance, growth and success of new venture firms.

To derive a novel conceptual SC capability development framework and a series of propositions, we conducted multiple case study research and approached the following research questions:

Which SC capabilities do new ventures nurture over time?

How do SC capabilities relate to the dimensions of DCs, i.e. help to expand, change or reconfigure the new venture’s resource base?

How does the development of DCs itself take place?

By answering these questions, several contributions arise from our study. We show how SC capabilities and DCs evolve along the new venture life cycle and detail which capabilities these are. We contribute to the literature on dual-purpose capabilities and underline that SC capabilities can serve both purposes. We show how critical SC capabilities are for new venture growth. More generally, we expand the limited body of knowledge at the OM/SCM–entrepreneurship interface.

The article is structured as follows. In Section 2, we review the literature on SCM at new venture firms, new venture life cycle stages and DCs. Section 3 explains our qualitative case study research. Section 4 presents the findings and derives a conceptual SC capability development framework. The article concludes with contributions to theory and practice, limitations and recommendations for future research in Section 5.

2. Background and prior literature

2.1. Supply chain management at new venture firms

Commonly, both upstream (supply) and downstream (demand) operations, which cross organisational boundaries, are fundamental for SCM (Mentzer, Stank, and Esper Citation2008). For the development and implementation of supply chain processes, routines and resources, firms work on the internal alignment between different functions within the firm (e.g. marketing, logistics, production) and the external alignment across organisational boundaries (e.g. with suppliers, customers, service providers) (Wagner and Eggert Citation2016). This includes on the upstream side purchasing, outsourcing, make-or-buy decisions, supplier selection, and R&D partner collaboration, and on the downstream side sales and distribution channels, transportation or physical delivery of products, and customer service related logistics. As such, new venture firms require SC capabilities to manage up- and downstream activities.

The supply chain and entrepreneurship literature has started to explore new ventures’ efforts to internally and externally integrate the supply chain (Wagner Citation2021). The few prior studies on internal and external alignment of new venture supply chains, however, are mostly concerned with structural characteristics of new venture firms and how these characteristics influence new venture growth, scaling or survival.

Internal. New ventures have to build up their internal resources, and hence their internal operations and supply chain activities, from scratch. Prior studies have investigated how new ventures’ limited resources, investment into resources or resource slack influence new venture performance. Tanrisever, Erzurumlu, and Joglekar (Citation2012) study trade-offs between investments in process improvements vs. holding cash reserves. The former would improve new ventures’ efficiency and reduce cost, and the latter would curb the chance of getting bankrupt. They show that such decisions are dependent on technology uncertainty, demand, and competition. Azadegan, Patel, and Parida (Citation2013) examine the nuanced effect of slack in new ventures’ production operation on new venture survival under various levels of environmental uncertainty. Operational slack reduces failure rates with increasing environmental uncertainty. Tatikonda et al. (Citation2013) derive recommendations on which operational metrics new venture firms should foster in different life cycle phases, namely on inventory turns in early phases and gross margins in later phases. Joglekar, Lévesque, and Erzurumlu (Citation2017) discuss the alignment between new venture firms’ business model innovations and operational innovations, where examples of the latter are yield management practices (at Uber) or quality management practices (at Airbnb).

External. On the upstream side, Salimath, Cullen, and Umesh (Citation2008) investigate how a new venture’s age, size, innovation, and governance structure moderate the relationship between outsourcing and financial performance of the new venture firm and find that larger and more innovative startups benefit most from outsourcing. Bustamante (Citation2019) finds that domestic new ventures outsource more likely than international new ventures, and that the new ventures’ contracting capabilities influence the degree of outsourcing. Bhalla and Terjesen (Citation2013) investigate sourcing activities of new venture firms and show differences in new venture performance contingent on how strongly the supplier is embedded in the supplier network. Furthermore, they argue that new venture firms can enhance their outsourcing capabilities if they possess ‘technical, evaluation, relational, entrepreneurial, and integration competencies' (Bhalla and Terjesen Citation2013, 175). Bjørgum, Aaboen, and Fredriksson (Citation2021) recommend that new venture firms should source directly from suppliers (not through intermediaries) and engage in pre-sales activities.

On the downstream side, Baum, Calabrese, and Silverman (Citation2000) and Hora and Dutta (Citation2013) study downstream alliances in the pharmaceutical/biotech industry and how the depth and scope of the new venture firms’ alliances with pharmaceutical companies influence the success of the alliance. For example, the success can be enhanced if the cooperative activities are broader in scope (i.e. encompass more varied aspects of the value chain, such as marketing, distribution, R&D, and production) (Hora and Dutta Citation2013). Brettel et al. (Citation2011) study the factors that determine if new venture firms choose direct vs. indirect channels of distribution. These factors are transaction cost-related, product-related, strategy-related and competition-related. And a fit between the factors and the chosen distribution channel positively influences new venture market performance and profitability.

In sum, these initial studies on supply chain processes, routines and resources of new venture firms are insightful and often help to predict why some ventures perform better than others (survive, grow faster), but are limited in terms of explaining how new ventures grow.

2.2. New venture growth

Prior studies have investigated the growth of technology-based or manufacturing-based new ventures (e.g. Greiner Citation1998; Kazanjian and Drazin Citation1989; McKelvie and Wiklund Citation2010), in particular how new ventures best allocate resources over time (e.g. Lévesque, Joglekar, and Davies Citation2012; Tatikonda et al. Citation2013) and which factors determine new venture success in different life cycle stages (e.g. Duchesneau and Gartner Citation1990; Song et al. Citation2008).

Growth of new ventures is not happening evenly during the first years subsequent to inception but in distinct life cycle phases. The terminology is sometimes different and the delimitation of the life cycle phases is fuzzy. The life cycle of new ventures is frequently broken down into three to five phases. For example, conception & development, commercialisation, growth, stability (Kazanjian and Drazin Citation1989), creativity, direction, delegation, coordination, collaboration (Greiner Citation1998), or startup, growth, and stability (Tatikonda et al. Citation2013) phases have been distinguished.

Principally, new venture firms face unique challenges in dealing with their liability of smallness and newness, operational challenges, organisational structures, degree of formalisation, and their approaches concerning market and customer access (Gilbert, McDougall, and Audretsch Citation2006; Tatikonda et al. Citation2013; Wagner Citation2021). Likewise, capabilities evolve throughout the life cycle phases. Tatikonda et al. (Citation2013), for example, suggest and empirically validate ‘specific operational capabilities that are especially impactful in respective phases' (1402).

2.3. Dynamic capabilities

The DC perspective builds on the evolutionary theory of the firm (Nelson and Winter Citation1982) and assumes, amongst others, path-dependent organisational learning of routines (Joglekar and Lévesque Citation2013; Zahra, Sapienza, and Davidsson Citation2006). Further, it extends the resource-based view (RBV), which primarily focuses on existing resources of the firm, by addressing the extension and change of these resources (Helfat and Peteraf Citation2003; Schilke Citation2014). DCs received not much attention before the seminal work by Teece, Pisano, and Shuen (Citation1997), which generated a plethora of strategic management literature. In this initial paper, DCs are defined as ‘the firm’s ability to integrate, build, and reconfigure internal and external competencies to address rapidly changing environments' (Teece, Pisano, and Shuen Citation1997, 516). Barreto (Citation2010, 271) aimed at bringing together numerous definitions by suggesting DCs as ‘the firm’s potential to systematically solve problems, formed by its propensity to sense opportunities and threats, to make timely and market-oriented decisions, and to change its resource base'. More broadly, Helfat and Winter (Citation2011, 1244) see a DC as ‘one that enables a firm to alter how it currently makes its living', and assign each DC a very specific purpose addressing specific activities.

There is a wide agreement on the distinction between dynamic and operational capabilities. Firms find standardised solutions and routines to solve their recurring problems. The pattern of routines represents the operational capabilities of a firm. These routines evolve over time and require updates when the environment of the firm changes or growth takes place (Wiengarten et al. Citation2023). Changing existing routines is done by higher-order routines, so-called dynamic capabilities (Zahra, Sapienza, and Davidsson Citation2006). Contributions by Helfat and Winter (Citation2011) and Stadler, Helfat, and Verona (Citation2013) stress that there is no bright line between these two forms of capabilities, but the significant systematic change of existing resources and routines can be understood as the result of DCs.

One aspect of interest is dimensions of DCs. The literature introduced a variety of synonymously used notations, which can be summarised into four distinct dimensions: Sense covers all DCs aiming at the exploration of external resources, including their identification and assessment. The firm analyzes external resource bases to find potential complements to the own existing resource base. Integrate includes all activities that bring external resources – including knowledge – into the boundaries of the firm. This could be from the resource bases of external partners like suppliers, R&D institutions, or distributors. The third dimension, develop, can be seen as the hearth of DCs since it contains the internal creation and expansion of the firm’s resource base. In other words, it comprises the setup of new routines, knowledge and also products by own capabilities. Reconfigure covers all transformations of existing resources for a better match with the environment, which include updates of existing routines and assets. links these four dimensions to their alternative notations and selected references.

Table 2. Main dimensions of dynamic capabilities.

The majority of DC research focuses on established firms ignoring the stark differences of new ventures regarding survival, legitimacy, and capitalisation of innovations (Sapienza et al. Citation2006; Zahra, Sapienza, and Davidsson Citation2006).

Noteworthy exceptions include Arthurs and Busenitz (Citation2006) who distinguish entrepreneurial capabilities from DCs of new venture firms. While the former involve ‘the identification of a new opportunity and the subsequent investments to the resource base', the latter support ‘the adjustment and reconfiguration of the resource base in conjunction with an extant opportunity' (Arthurs and Busenitz Citation2006, 199). Feng et al. (Citation2019) develop a conceptual framework that shows how ‘dynamic capabilities about market' and ‘dynamic capabilities about technology' help to renew resources of startup firms and the startups’ innovation ecosystem. Wu (Citation2007) shows that in changing environments, startups’ DCs are necessary for startup internal and external partner resources to result in higher startup performance. Concerning the types of external partners, Wu (Citation2007, 550) mentions

start-ups relying on upstream suppliers to supply raw materials, downstream channels to deliver goods, and research institutions to provide new technologies. These support firms or organizations provide resources that are necessary to the start-up and moreover that complement its existing resources.

3. Methodology

For this study, we applied an inductive case study approach with multiple cases to create a conceptual framework and propositions (Barratt, Choi, and Li Citation2011; Yin Citation2018). The choice and implementation of the chosen methodology have been done in light of several considerations. First, the research is descriptive and exploratory, and mainly asks ‘how’ questions (Barratt, Choi, and Li Citation2011), in particular, it aims to explore how new ventures grow and scale, and how new venture firms develop and nurture SC capabilities. Second, with our research, we attempt to introduce an existing theory to a new context and derive novel juxtapositions between DC theory and new ventures’ SCM. Our research aims at building new models (i.e. frameworks and propositions) as opposed to testing theories or models (Eisenhardt Citation1989). Third, on the one hand, SCM at new venture firms has received less attention from other stakeholders (e.g. investors, accelerators), so that information concerning new ventures’ SCM practices is not collected as systematically as technology, founding team, customer or funding information. For studying the latter, commercial data sources such as Crunchbase or PitchBook, consortia databases such as the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM), or proprietary startup resources collected at universities or research institutes (e.g. Babson College, UC Berkeley) are readily available. This is not the case for SCM-related information. On the other hand, SCM strategies and practices are less ‘structured’ (particularly in new venture firms) to be accessible through standardised data collection methods. Therefore, primary data collection via case studies is the method of choice. Fourth, prior empirical studies on DCs (Di Stefano, Peteraf, and Verona Citation2010) or capabilities in a logistics or supply chain context (e.g. Marsillac and Roh Citation2014; Sandberg and Abrahamsson Citation2011) showed that rich and real-world capability phenomena can be well captured with multiple case study research. Fifth, as shown in Section 2.1, studying supply chain management strategies and practices at new venture firms is still at its infancy. In sum, inductive, exploratory case study research involving multiple cases and semi-structured interviews seemed to be an appropriate method (Barratt, Choi, and Li Citation2011; Yin Citation2018).

3.1. Sampling and data collection

In line with common practice (Barratt, Choi, and Li Citation2011), our inductive case study approach used ‘theoretical sampling of multiple cases' (338). Given the variety of new venture firms that might offer various products, be in different life cycles stages, or rely more or less on supply chains and supply chain practices, we choose our case study firms for theoretical reasons (e.g. Barratt, Choi, and Li Citation2011; Yin Citation2018). First, we focused on new ventures with a manufacturing background. We sampled firms engaging in production of physical products from different industry sectors, such as consumer devices, machinery, electronics, materials, and medical, since different supply chain strategies and developments in different industries were expected. Second, new ventures had to be independently held and not part of a larger group. Third, we choose firms with varied age in order to be able to shed light on the development of SC capabilities over different life cycle stages. All firms were younger than eight years, a typical cut-off for startup firms (Fauchart and Gruber Citation2011; Song et al. Citation2008). Fourth, we used leading and successful entrepreneurial ventures for benchmarking purposes, where ‘superior performance relative to […] (competitors) provides an empirical indicator of competitive advantage' (Schilke Citation2014, 180). Firm age and success are two interrelated variables due to the extraordinarily high probability of failure (Tatikonda et al. Citation2013). While data about age was simple to collect and verify, ‘success' meant for this study in general that the new venture firms reached serial production and faced high (double-digit) revenue growth over several years. Fifth, we included cases from a developed (Switzerland) and an emerging (China) economy to explore if the institutional and economic environment for new venture firms leads to similar or contrary patterns of SC capabilities and DCs during new venture growth (Yin Citation2018).

We identified the potential new venture firms and assessed the initial suitability with the sampling criteria via internet research. In Switzerland, there are several startup competitions to initialise and support entrepreneurial culture. They publish yearly summaries of top startups, which served as a starting point for our sampling. If the necessary information was not available on the internet, phone calls helped to obtain an initial assessment of the new venture’s success. In China, we found firms mostly through internet research. The participant lists of various industry fairs were scanned for firms which suited our age and manufacturing criteria.

depicts the aggregated statistics of the 15 new venture firms finally included in our study (11 from Switzerland and 4 from China), and more detailed firm level demographics are included in Appendix 1. The diverse nature of these new venture firms underlines that external validity of the data and robustness of the subsequent findings and frameworks are likely.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of case study firms.

In every case, one or more interviews were conducted (face-to-face, only for one firm by video call). The unit of analysis was the specific new venture (Yin Citation2018). We interviewed founders (serving as CEOs, COOs, etc.) or managers responsible for building up SC capabilities during the inception and scaling of the new ventures. We guaranteed confidentiality to reduce socially desirable responses and other biases. All interviews were conducted by two investigators (Dubé and Paré Citation2003). Interviews lasted from 45 min to 1.5 h (on average 60 min) and were conducted both in English and German (translated into English later).

For the purpose of triangulation, we validated wherever possible information obtained from the interviews and added additional information from other sources, such as direct observations (site visits, inspection of prototypes or product samples), firm archives (correspondence, manuals, new venture-internal analyses) as well as public internet resources. Observations were possible in all cases, except for the firm interviewed remotely.

In all interviews, we sequentially asked open-ended questions with follow-up questions to investigate interesting answers more deeply. The interview protocol (Appendix 2) ensured consistency across the cases and covered four aspects: (A) profile and background information related to the interviewee and the new venture itself; (B) all major operational topics addressing the upstream SC, including supplier selection, procurement routines, outsourcing decisions, R&D alliances, and partnerships; (C) topics addressing the downstream SC, including distribution channels, distributors, the usage of logistics service providers (LSP), and customer service; (D) operational orientation of the founders. After the first three interviews, we added the often-mentioned topic of research partnerships to the interview protocol. For topics (B) to (D), we tried to capture time variance by asking for initial conditions and changes over certain years after incorporation. To avoid response bias, we did not ask for DCs or any of the four defined DC dimensions (sense, integrate, develop, reconfigure) directly. Finally, the interviewees could add relevant ideas and topics which were not addressed before.

provides a distribution of the new ventures’ SCM when the case study data was collected. The majority of firms had own operations, and relevant R&D partnerships besides suppliers, and make use of distributors for their products. About half of the new ventures had developed truly new products or product lines.

Table 4. Aggregated characteristics of new ventures’ SCM.

3.2. Data analysis

Data analysis took place simultaneously and incrementally during data collection (Barratt, Choi, and Li Citation2011; Gioia, Corley, and Hamilton Citation2013) and followed generally accepted coding procedures (Miles and Huberman Citation1994). Prior literature and a priori conceptualisations discussed in Section 2 were used as starting points for analysis (Eisenhardt Citation1989). The new venture growth literature indicated the existence of time phases in the evolution of new firms into established ones. Hence, we read through all interview transcripts to identify more or less distinct life cycle phases, which were independently achieved (startup, growth, and stability phase) and discussed later. Afterwards, we included upstream and downstream SCM topics to derive matrix-displays (SC capabilities along the DC dimensions and the life cycle phases).

Two researchers independently coded the final categories. After coding the interviews related to the 15 new ventures, theoretical saturation (Denzin and Lincoln Citation1994) was reached – a point where no new insights on SCM of new ventures and time variances appeared. This coding was then used as the main data to derive the findings. To interpret and find common patterns, we first analyzed within cases and then across cases. Then we identified the SC capabilities in these derived matrices, which match the four dimensions of DCs found in the literature (sense, integrate, develop, reconfigure). Any discrepancy between the two coders were reconciled to strengthen the internal validity of the findings.

4. Findings

As outcomes of this inductive case study research, we are able to discuss the life cycles of the new venture firms we studied, most notably the SC capabilities of the new venture firms and their evolution over time, and the SC capabilities’ dual purpose as DCs, and how they relate to the DC dimensions.

4.1. New venture life cycle phases

Without pointing to the new venture life cycle phases discussed in Section 2.3, the interviews revealed that the respondents also distinguish between these phases. At the beginning of our analysis, we identified three phases that the interviewed founders, CEOs, and managers used to structure the early life of their firms. The identified phases closely matched the phases suggested by Tatikonda et al. (Citation2013).

Startup phase. All interviewees referred to an initial, early or ramp-up time of their firm. After receiving some funding, the manufacturing new ventures had to build or improve prototypes, hire key employees, and manage to get first customer orders. A new venture goes through all these steps until it has a product ready for market release at a large scale. We labelled this time span ‘startup phase' and collected statistics from the 15 new ventures (durations in years: mean 3.1, median 3.0, stdev 0.7).

Growth phase. Since our sample consisted of highly successful new ventures, they survived early years to then face strong growth of revenue or at least employment for industries where sales take a long time to kick in, e.g. biotech and medical technology. Interviewees described how production output could hardly satisfy demand growing double-digit percentage per month. Demand growth was fuelled by parallel market entries in new countries. The case study firms were approximately from the fourth to fifth year after foundation in this turbulent phase (mean 2.3, median 2.0, stdev 0.6).

Stability phase. After years of quick growth, new ventures went to their last stage before becoming an established organisation – the stability phase. In this phase, ventures already have a large customer base, and high growth rates become difficult to maintain and will eventually lower to normal market growth rates. Corporate structures become more formal. Ventures often start the development of new product lines or product derivatives, exploit further countries to maintain growth and deal with intensified competition from copycats or larger firms. In most cases, we observed the beginning and middle of this stability phase (mean 2.0, median 2.0, stdev 0.9).

4.2. Evolution of SC capabilities during new venture growth

Initially, new ventures face resource scarcity. The founding team itself represents most of the human resources, and few assets (such as equipment and machinery) are owned, but plenty of knowledge of the founders, including intellectual property (IP) was front-loaded before incorporation in years of work and scientific experience of the founders. On this resource base, new ventures intuitively solve problems to a large part through improvisation (i.e. trial and error and experimentation) as well as imitation (Zahra, Sapienza, and Davidsson Citation2006).

As a startup you never have enough money to do what you want. So you have to start playing and it is a daily juggling with your resources. It is not a big company, there are no rules. You take things the way they are. And search for better ideas. And try to impact the market with half the money your competitors have. That is the startup life. (Medical devices 2, S.V.)

Capabilities, on the other hand, are learned processes and routines that are either resource base utilising (operational) or altering (dynamic). The interviews revealed that new ventures possess specific SC capabilities that serve a dual purpose. First, they are needed to operate the new venture’s supply chain and enable the development and reconfiguration of the new venture’s resource base. Second, they allow for the sensing and integration of external resources and serve as means to create new or update and modify existing SC capabilities. Hence, SC capabilities can be ‘dual-purpose' capabilities which serve ‘both dynamic and operational purposes' (Helfat and Winter Citation2011, 1248). We observed a transition from improvised and imitated problem solving to standardised or professional routines and SC capabilities that determined to a large part the internal resource base and possibilities to grow in consecutive life cycle phases. As a consequence, resource bases get less variable and SC capabilities become more stable through learning effects: supplier selection and procurement rules get introduced, best-practices for distribution, customs, and transportation are applied to newly entered markets. So we could observe a stabilisation of the new venture’s resources but also the way it utilises and alters them.

In the following, we discuss the different relevant (operational) SC capabilities in each of the three life cycle phases and relate them to the four dimensions of DCs ().

Table 5. Identified SC capabilities.

Upstream operations. Manufacturing-based new ventures face resource scarcity compared to established firms, which forces them to leverage external partners for their production and R&D. The following four aspects (outsourcing, supplier selection, procurement routines, and research partnerships) cover the routines described by the informants to set up and manage their upstream operations.

Outsourcing. Production and assembly were sourced out by the new ventures to the highest possible degree. Four firms did not even add any value by themselves due to outsourcing the entire production. The central argument was production costs, since the interviewees stated they cannot produce larger quantities at competitive prices on their own. When the firms industrialised their prototype production, they had to develop an entire operational resource base. Additionally, one could identify an outsourcing decision capability responsible for determining make-or-buy for all processes and components. The share of outsourced operations stayed stable across the life cycle phases without major fluctuations implying that make-or-buy decisions in the startup phase determine the path for the growth and stability phase.

Everything was extremely lean, but not as a decision, there is just no possibility to make it different. You cannot afford to pay people. There is no choice. (Consumer devices 1, W.K.)

We own the patents and made the detailed construction plans. We do not produce by ourselves. We only do customer service and sales. (Security equipment 1, K.O.)

We still do much more in-house than we intend to. The modification of the products is highly specialised work, we cannot write that in a manual. You have to teach someone for over a month, which is the reason we do it in-house. (Medical devices 1, U.S.)

Cost is a topic of the future. Flexibility is more important. A supplier needs to be willing to try new things and to reserve us some machine time to do tests. (Materials 1, H.M.)

Know-how defines a supplier and is critical for his selection. Cost are not a focal point with small production numbers. (Measurement and testing technology 1, F.H.)

We are constantly looking for alternatives. There is a company in Switzerland producing [device], I think XYZ. They approached us if we wanted to produce at their place. Switzerland is better quality, but it was too expensive. The guys in Poland are our best option right now. (Consumer devices 1, W.K.)

Our suppliers do have the construction plan with all details. We give them everything, since they need the information anyways. It’s a trustful relationship. We do not mind, since the important part is the software. The physical product might be copied but the cost/complexity is at some other place. (Measurement and testing technology 2, A.K.)

In case of problems with components and commodities you can always change. But in case of important components or key suppliers changing the supplier is not that easy. There, you try to solve the problem together. Of course you always search for alternatives, but normally you use the new alternative when you develop a new product. (Measurement and testing technology 3, U.E.)

[…] Another example: front panels. The white shiny things. Often there are scratches. The painter says: ‘It wasn’t me, they left my workshop in perfect condition'. The printer says: It wasn’t me, they arrived already damaged. In the end we had to pay everything, throw them away and order new ones. Today the process is different. The printer buys the panels and sells them to the painter, who sells them to the convector. All control their incoming products and reject the damaged ones. Since everyone buys the product for themselves none of our money is involved. In the end, the panels come to us. We control them and only then we pay. Basta! Awesome! Nevertheless, it was a lot of work to set up this simple three step process. 3 weeks full time. We needed 2–3 years until it was established. (Measurement and testing technology 2, A.K.)

In the first two years we could use the equipment of our old research institution to fulfil the first customer orders. (Measurement and testing technology 4, S.T.)

For one product we build prototypes with a Swiss partner. From the beginning it was clear: only prototypes no serial production, the cost didn’t give us another option. There we did everything right. It was a knowledge transfer from one partner to the next. We used the finished prototype to go to potential suppliers to ask: ‘This is how it works. Would you produce it and what would it cost?' (Materials 1, H.M.)

We did several Suisse Innovation Agency projects. Mainly with technical colleges. We profited from these projects. We supervised several study projects. There we profited, too. We could leverage their resources. We were missing the knowledge and later we hired two students. So we accomplished a knowledge transfer from the university to us. (Measurement and testing technology 3, U.E.)

Downstream operations. To bridge the gap between production and customers, various elements are required, like distribution channels, transportation, and customer service. Similar to the upstream operations, a number of SC capabilities help to identify distribution partners and integrate external resources like experienced sales staff, means of transportation, and other sales knowledge into the new venture. Later, these and other capabilities are developed and reconfigured as described in the following.

Channel expansion. In the startup phase, one half of the interviewed firms entered into an existing product market without an own track record, and the other half tried to create a market for a completely new product, which resulted in try-outs of different distribution channels and target customers. Later these first customers and distribution channels were exploited to gain more insights and feedback about the product and customer experience. In the growth phase, new ventures transferred themselves from R&D-driven firms to sales-oriented ones. This began by developing capabilities of an own marketing/sales department. On product and country level, experiences from one were transferred to future ones. In the stability phase, firms kept expanding their customer base, but also shifted their sales channels away from direct sales to distributor-based sales (DC reconfiguration dimension).

Switzerland was our test market. We tested a broad variety of sales channels e.g. pharmacies, hospitals, internet and direct sales. (Consumer devices 2, D.K.)

It makes sense to sell the first products close by. However, often that comes naturally since innovation is often triggered by your customers. That can be research institutions as well, since they are relatively flexible. (Measurement and testing technology 3, U.E.)

First the US market, then the rest of the world. American researchers see the possibility to be the first and to exploit a new technology. He himself has the authority to buy and just buys. (Measurement and testing technology 2, A.K.)

At one point we shifted our focus on sales. After the first years with a team of 5 or 6 members we built up a sales department. For us it was more difficult than the setup of the development department, since we had no experience or contacts in that area. (Medical devices 1, U.S.)

We wanted to transfer our experience to other countries. So we wrote manuals and adapted them locally. (Consumer devices 2, D.K.)

(In the stability phase) The expensive sales channels cannot be utilized anymore. You cannot fly to Hamburg for a presentation. We want to introduce a web shop. That comes at the same time as our ERP. (Measurement and testing technology 2, A.K.)

Considering it from the retro perspective, it was a three step process. In the beginning we contacted the brands via cold calls. Since they do not produce by themselves anymore they lead us to their industrial partners. So we contact the industrial partners directly. Those industrial partners produce for several brands. Then we went to them and tried to convince them to use our materials in the other brands as well. These are always direct contacts. (Materials 1, H.M.)

With company XYZ we worked together when they asked us to join them to attend a trade fair together. Then we got attention, applied for public research funds. But always we actively approach customers. (Security equipment 1, K.O.)

With direct selling you get more margins, but the money comes much, much later. (Consumer devices 1, W.K.)

Distributors aren’t all so good. It is their potential and you have to work with them, so that they can perform. They have many products and you have to fight, so that they are selling your product and not others. It is a lot of work on your side but in the end they are showing your product to the clients and that is the only thing on earth you want. (Medical devices 2, S.V.)

Distributors they pay upfront, but they get 10% to 15% on top of the production price. So you get the money immediately but have less margin. (Consumer devices 1, W.K.)

We try to negotiate a minimum purchasing quantity to secure a certain amount of revenues. (Medical devices 3, P.N.)

We did a project to professionalise our transportation processes. But it was vain. Our quantities are so small that transportation companies do not read an RFQ. […] in case of a delivery we are supposed to give the transportation companies a call and they say us the price. (Materials 1, H.M.)

One problem was that we never thought about the transportation of our product to the customer. Our first tries were not successful. We had to develop a special packaging. One customer demanded these special packages and so one additional product was developed. (Medical devices 3, P.N.)

Improvement via feedback from failures. (Measurement and testing technology 1, F.H.)

Marketing/sales manages the support, the user manual, the website and the blogs. We outsourced nothing. From the beginning we offered this level of support. Standard and premium. In the beginning it does not matter, since we sell every year more products than currently on the market. Of course you have to support the old products but the needed resources are insignificant. (Measurement and testing technology 2, A.K.)

Of course, the transformation from a research oriented firm to a sales driven one has to be done systematically and deliberately. Previously there were ad hoc solutions. Depending on the problem the expert was asked. Now we hired someone whose full job is customer service. He just was in China and now goes to India to give instruction courses. (Security equipment 1, K.O.)

4.3. Swiss vs. Chinese new venture firms

Switzerland is a highly developed country with traditionally strong entrepreneurial activities. China, as an emerging economy, has experienced or is undergoing substantial changes when it comes to entrepreneurial activities. China started only about 20 years ago and rapidly developed when the country released a strategy for a startup ecosystem in 2015 (Hyun et al. Citation2020). The goal was to create qualitative growth of entrepreneurial activities, particularly in the high-tech sector. When it comes to innovation and entrepreneurial activities, the Global Innovation Index (GII) is of interest. Both countries have increased their rank in the GII from 2010 to 2020: Switzerland has moved from rank 4 to 1, and China made an even bigger step forward from rank 43 to 14 (Dutta Citation2010; Dutta, Lanvin, and Wunsch-Vincent Citation2020).

Given the historically different institutional and economic environments for entrepreneurial activities in Switzerland and China, we expected that new venture firms, their growth and the build-up of SC capabilities and DCs might also diverge. Our cases show, however, that the creation and advancement of SC capabilities in Switzerland and China are quite akin.

The foremost and meaningful difference new venture firms face is on the supply side.

When you order a small sample, it looks like the quality is ok. But when you place a large order, we often have quality problems. This is one of the major problems we are facing. (Medical devices 3, A.S.)

[When quality drops] often the suppliers simply don’t care. There are too many other customers. […] We had quite tight specifications […], therefore the machine has to be calibrated by an expert before our batch. […] They told me that unlike from us, from other customers, no one is coming to test the pieces. When we complained, they said take it or leave it […] (Machine tools 2, P.S.)

How to approach the suppliers is a very complex network. That’s where the Chinese word ‘Guanxi' starts to weigh in. If you have Guanxi, you find certain suppliers, if you don’t have it, you simply don’t […] (Machine tools 2, P.S.)

Chinese new ventures will more likely refrain from outsourcing. For them, finding suppliers that meet quality criteria is much more difficult, and the supply quality is less consistent than what Swiss new venture firms reported. Overall, the identified SC capabilities are fairly similar, and only the upstream operations require some adaptations in the Chinese context.

4.4. Dynamic capability dimensions of SC capabilities during new venture growth

We analyzed the capability and resource base development of new ventures across the initial six to eight years after incorporation. The identified SC capabilities can be assigned to the four DC dimensions sense, integrate, develop, and reconfigure, as shown in . In the following, we expand on these DC dimensions and propose how SC capabilities evolve within each DC dimension.

Sense. In the startup phase, new ventures have to identify relevant external resources that could complement their own and often scarce resource bases. Focusing on operations-related topics, components, technological knowledge, and customer feedback is highly required. An assessment of suppliers completes the initial set of DCs to sense resources. In later stages, partnering capabilities become relevant to manage the relationships with existing and new suppliers, R&D partners, and distributors.

Proposition 1a: New ventures’ sensing DCs focus on identification and assessment of potential external supply chain partners in the startup phase, and shift toward identifying opportunities for collaboration with external supply chain partners in the stability phase.

Integrate. DCs are the main set of routines to integrate external resources into the new venture. In the beginning, these are primarily key personnel, technological knowledge and public R&D funds, whereas later sales power of distributors and resources of stronger R&D partners become important.

Proposition 1b: New ventures’ integrating DCs focus on obtaining missing intangible resources from supply chain partners in the startup phase, and shift toward exerting power in the stability phase.

Develop. Firms internally grow their existing resource base by developing DCs. Knowledge and routines have to be build-up in the beginning. Later, for example, entire departments have to be formed out of loose organisational structures and various IT systems. Similarly, the development of new product derivatives is the result of DC development.

Proposition 1c: New ventures’ development DCs focus on initial and elementary processes and routines in the startup phase, and shift towards integrated and aligned structures in the stability phase.

Reconfigure. In the stability phase, strong growth of new ventures requires especially major rescaling, adjustments, and implementation of first customer learnings on the resource base.

Proposition 1d: New ventures’ reconfiguration DCs are absent in the startup phase, and emerge in the stability phase to encompass the modification of various processes, routines and resources.

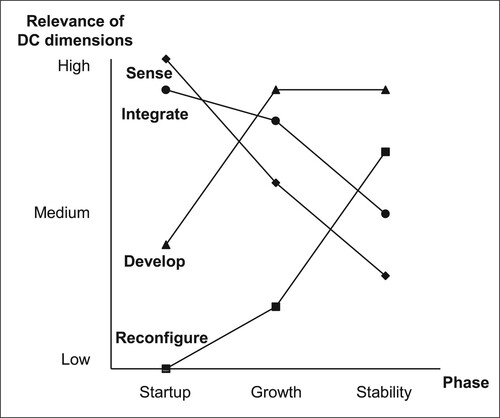

Our analysis shows that the new venture case study firms’ SC capabilities evolve over time. New capabilities are added in later life cycle phases and are contingent on capabilities exerted in earlier life cycle phases. For example, in the development dimension, it is vital that elementary processes and routines are in place first (e.g. an ISO certification or functioning distribution channels) before new products can be developed or new markets accessed. However, not only do the SC capabilities develop over time, the DC dimensions they are assigned to also vary over time. We observed how relevant different DCs are in order to allow new ventures to build up their resource base and facilitate growth. provides a stylised overview of new venture growth and varying relevance of the four identified DC dimensions over time.

One can see a shift from the dimensions of sense and integrate dominating the startup phase toward develop and reconfigure dominating in the stability phase. Hence, at the onset, new venture firms begin identifying which potential supply chain partners they could benefit from and integrate lacking intangible resources from them (e.g. R&D). Furthermore, they establish some basic processes and routines (e.g. establish distribution channels) that allow them to approach the market. Reconfiguration of resources is absent. As the new venture grows, the internal resource base has grown as well (with the ‘help’ of the supply chain partners). Now, resource development emphasises novelty and differentiation to be able to create broader product and service offerings. Furthermore, after several years in business, reconfiguring the resource base (e.g. reconsidering earlier outsourcing or make-or-buy decisions) offers opportunities to increase efficiency and the competitive position in the market. Propositions 2a and 2b suggest how the SC capabilities evolve across the DC dimensions throughout the life of new ventures.

Proposition 2a: In the startup phase, sensing and integrating SC capabilities are most relevant.

Proposition 2b: In the stability phase, development and reconfiguration SC capabilities are most relevant, while sensing and integrating SC capabilities loose in magnitude.

4.5. Conceptual framework

Based on the discussion of the SC capabilities along the DC dimensions and the new venture life cycle phases in the previous sections, we summarise the findings in a conceptual framework for capability development (). Fundamentally, SC capabilities of new venture firms can take the role of DCs by sensing and integrating external resources and developing and reconfiguring a new venture’s internal resources. They enable the new venture firm to tap external resources from external supply chain partners, such as suppliers, R&D partners or distributors. These resources, in turn, will augment the new venture’s internal resources, that is, grow its assets, add needed employees, and build up critical knowledge (Teece, Pisano, and Shuen Citation1997).

Growth of the new venture’s internal resources is only possible if external resources are sensed and integrated, and if resources are developed and reconfigured over time. Since ‘supply chain resources and capabilities are fundamental for startup growth and survival' (Wagner Citation2021, 1130), the more or the faster new venture firms are able to build up SC capabilities over time (from the startup via the growth to the stability phase), the more and the faster they will be able to enhance their internal resources.

Proposition 3a: SC capabilities allow new venture firms to sense and integrate external resources.

Proposition 3b: SC capabilities allow new venture firms to develop and reconfigure internal resources.

Over time, new venture firms augment their (operational) SC capabilities, and learn and build on existing SC capabilities. Hence, they replace supply chain activities that are based on improvisation, imitation or trial-and-error with planned and structured supply chain activities (Zahra, Sapienza, and Davidsson Citation2006). Operational SC capabilities replace improvisation and imitation. And with maturing and more professional SC capabilities, a new venture’s internal resources will grow.

Proposition 4: Throughout new venture life cycle stages, improvisation and imitation of activities are replaced with SC capabilities.

5. Discussion and conclusions

Taking the criticality of operations and supply chain management for new ventures, our desire to add to the body of knowledge on how new ventures grow, and the limited understanding of SC capabilities at new venture firms as starting points, our study contributes to the scholarly literature in several ways and provides a number of recommendations for practitioners, such as founders.

5.1. Scholarly contributions

The positioning of our study at the OM/SCM–entrepreneurship interface (Joglekar and Lévesque Citation2013; Kickul et al. Citation2011) enabled us to create novel insights into how new ventures grow through the development of SC capabilities and how SC capabilities evolve over time. More specifically, the scholarly contributions of our study are the following:

First, we bring together literature from two fields, namely OM/SCM and entrepreneurship, that have not yet integrated their knowledge bases very well (Ketchen and Craighead Citation2020). New ventures and their growth is ‘on the agenda of both ‘camps’ ‘ (Kickul et al. Citation2011, 78) and our study provides some common ground for both. The hope is that this instills more research on new venture supply chains at the OM/SCM–entrepreneurship interface.

Second, we augment prior studies on new venture growth and scaling by taking an operations management as opposed to entrepreneurship lens on growth and scaling (Shepherd and Patzelt Citation2022). Based on this, we contribute to the very limited ‘inquiry [that] has occurred at the intersection of entrepreneurship and supply chain management' (Ketchen and Craighead Citation2020, 1330). We show how new ventures nurture various operations and supply chain strategies, processes and routines to increase revenues, expand into new markets, or grow their product and service portfolio. Furthermore, we shed light on how new ventures develop SC capabilities that help them to tap external resources upstream and downstream in the supply chain (e.g. from suppliers and distributors) (Mentzer, Stank, and Esper Citation2008).

Third, our study explores operational SC capabilities of new ventures along new venture life cycle phases. The initial startup phase includes capabilities such as prototype development, first sales, and hiring of key employees. Important decisions are realised, such as the selection of first suppliers or the testing of distribution channels. In the subsequent growth phase, numerous routines are implemented to professionalise operations and allow scalability for entering additional markets or distribution channels, and more generally, growing in headcount and assets. Thereafter, the stability phase covers how new ventures mature and grow profitable with product derivatives in additional countries, and often under increased competition. Prior research on the strategies, processes and routines of new ventures along the life cycle did either not discuss operations and supply chain management at all (e.g. Gilbert, McDougall, and Audretsch Citation2006; Greiner Citation1998), or was primarily interested in the relationship between operational metrics – such as inventory turns, gross margins and productivity – on new venture survival (Tatikonda et al. Citation2013). Owed to the qualitative case study methodology utilised, we were able to provide a richer and more faceted discussion of new ventures’ SC capabilities throughout the life cycle phases.

Fourth, we followed Sandberg and Abrahamsson (Citation2011) who utilise DC theory to explain how logistics and SC capabilities can contribute to firm competitive advantage, and took up Sebastiao and Golicic’s (Citation2008) suggestion to further our understanding of emergent supply chain strategies (i.e. supply chains of emergent firms) by drawing on DC theory. Hence, we can showcase a novel application of DCs in a supply chain context, i.e. new venture supply chains and expand the literature that has used DCs for other applications in logistics and supply chain management, such as supply chain integration (Song and Song Citation2021) or supply chain resilience (Manikas, Sundarakani, and Shehabeldin Citation2022; Sabahi and Parast Citation2020). Furthermore, our study links SC capabilities and DCs in the context of new venture firms and hence adds to be body of knowledge on DCs.

Fifth, we have taken up the concept of dual-purpose capabilities (Helfat and Winter Citation2011) and show that SC capabilities ‘can be used simultaneously for operational and dynamic purposes’ (Kahl Citation2014, 381). Kahl (Citation2014) discusses production planning as a dual-purpose capability of established firms and exemplifies how production planning was used ‘for dynamic purposes' (Kahl Citation2014, 385):

The first is supplier access and management. These capabilities often fall under the purview of purchasing and promoted activities such as negotiating with suppliers, building long-term contracts, and working with suppliers to order and receive inventory. Such capabilities can be used for operational purposes to meet existing production demands, or they can be used for dynamic purposes to reconfigure vendor relations and leverage contracts to the firm’s advantage. This dynamic capability is the supply-side corollary to Helfat and Winter’s (Citation2011) example of Microsoft altering its distribution ecosystem to its advantage.

For new venture firms who have limited resources, and who face emergent environments and ambiguous markets and industry structures (Santos and Eisenhardt Citation2009), the need to leverage capabilities for dual purposes is even more critical. We argue that SC capabilities are particularly destined to serve as dual-purpose capabilities because of their internal and external boundary spanning capacity (Morash, Dröge, and Vickery Citation1996; Wagner and Eggert Citation2016). Supply chain management strategies, processes and routines link firm internal (e.g. production–sales) but mostly external (e.g. suppliers, R&D partners, distributors) elements that help to sense and integrate external and develop and reconfigure internal resources of the new venture.

Sixth, we identified four distinct dimensions of DCs in the literature, namely sense, integrate, develop, and reconfigure () and linked them to the dual-purpose SC capabilities (). We found that sensing and integration DCs dominate in the startup phase, and development and reconfiguration DCs in later life cycle phases of new ventures. This indicates a utilisation of external resources in early stages and an upgrading of internal resources in later stages.

Finally, besides contributing to a more tangible understanding of DC theory, our study is another empirical exploration of DC theory (Barreto Citation2010; Stadler, Helfat, and Verona Citation2013) in the context of new venture firms (Arthurs and Busenitz Citation2006; Feng et al. Citation2019; Wu Citation2007).

5.2. Practical implications

The insights of our study are also beneficial for founders of new ventures and practitioners involved in incubator, accelerator, venture builder, venture capital or corporate venture capital activities. First, the SC capabilities and the dual-purpose as DCs we observed at the successful manufacturing-based ventures from Switzerland and China supported their scaling efforts. This shows that SC capabilities are critical for new venture growth and survival. As a consequence, our findings should instill entrepreneurs to invest in SC capabilities early on. Second, the SC capabilities and their development over time can be seen as good practices for growing a new venture’s initial resource base. Hence, entrepreneurs at new venture firms can use the SC capabilities discussed in this study as benchmark or at least checklist for their own firms’ efforts to professionalise their supply chain strategies, processes and routines. For example, the life cycle-specific supply chain approaches help to structure the rapid expansion and spotlight the most likely upcoming operational issues like product derivatives, supplier contract renegotiation, or ERP preparation in the stability phase. Third, since firm environments and starting positions might vary and new venture firms are frequently resource-constrained, the SC capabilities and DCs discussed in our study can help the new ventures to prioritise their supply chain efforts. Fourth, our conceptual frameworks and tables support entrepreneurs in explaining and communicating the build-up of operations and supply chain activities to other stakeholders, such as investors or employees.

5.3. Limitations and opportunities for future research

The setting and the methodology applied in this study comes with limitations which need to be considered when interpreting the results. First, a country-bias (Switzerland, China) and a survivorship-bias (resulting from selecting only highly successful ventures about eight years after foundation) might have inflated or deflated the observed effects. Second, we took DCs, and more broadly, the RBV as a theoretical lens to understand resource base development of new ventures. However, also other factors or mechanisms might cause the observed resource changes. One could think of investors and other stakeholders influencing decisions to expand resources or join R&D-, supplier-, or distributor partnerships. Third, we limited our study to SC capabilities and to selected upstream and downstream SCM topics (see Appendix 2). These SC capabilities and topics, however, will likely interact with other functional capabilities (such as marketing and sales) and impact new venture growth. While we mention such interactions and the need for alignment between different functions, this perspective is not comprehensively explored in our study. Finally, the methodology has some weaknesses. Although we achieved a theoretical saturation in the findings and formalise our findings in propositions, aspects like external validity or idiosyncratic conclusions and internal validity (causal relationships) (Fauchart and Gruber Citation2011) are frequent shortcomings of case study research and typical issues to rectify with future large scale empirical studies. More rigorous surveys or archival resources should build on this foundation and validate the identified dual-purpose capabilities, DC dimensions and life cycle phases.

Additional alleys for future research could include the following. Besides characterising the nature of SC capabilities as dual-purpose capabilities, more insights are required on how to improve and actively manage them in practice. Especially, since antecedents and factors influencing the development of DCs are hardly known yet. Although our research hints at the location of such factors at the founders, future studies could explicitly target the origin of SC capabilities and DCs. Finally, service-based new ventures and their operations seem to be a promising field of research from a DC perspective (Tatikonda et al. Citation2013).

5.4. Conclusions

DCs became a key concept for explaining performance differences among firms, particularly firms facing emergent and dynamic environments. However, both, the state of knowledge about how they evolve (Barreto Citation2010; Stadler, Helfat, and Verona Citation2013), as well as DCs in the context of new venture firms (Arthurs and Busenitz Citation2006; Feng et al. Citation2019) are still nascent. Our study contributed to the body of knowledge at the entrepreneurship–OM/SCM interface by exploring dual-purpose supply chain-related capabilities across the life cycle phases of new ventures.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement:

Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.

Notes

1 In this article, we recurrently refer to ‘new ventures’ and subsume terms such as ‘new venture firms’, ‘entrepreneurial firms’, ‘new entrepreneurial firms’, ‘nascent firms’ or ‘startups’ as synonyms. A new venture is a firm that typically suffers from a liability of smallness and newness, and that was either founded by an individual or by a company as long as it did not receive key resources by a parent company (e.g. Wagner and Kurpujweit Citation2022; Zahra, Ireland, and Hitt Citation2000).

References

- Amedofu, M., D. Asamoah, and B. Agyei-Owusu. 2019. “Effect of Supply Chain Management Practices on Customer Development and Start-Up Performance.” Benchmarking: An International Journal 26 (7): 2267–2285. doi:10.1108/BIJ-08-2018-0230.

- Arthurs, J. D., and L. W. Busenitz. 2006. “Dynamic Capabilities and Venture Performance: The Effects of Venture Capitalists.” Journal of Business Venturing 21 (2): 195–215. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.04.004.

- Azadegan, A., P. C. Patel, and V. Parida. 2013. “Operational Slack and Venture Survival.” Production and Operations Management 22 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1111/j.1937-5956.2012.01361.x.

- Barratt, M., T. Y. Choi, and M. Li. 2011. “Qualitative Case Studies in Operations Management: Trends, Research Outcomes, and Future Research Implications.” Journal of Operations Management 29 (4): 329–342. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2010.06.002.

- Barreto, I. 2010. “Dynamic Capabilities: A Review of Past Research and an Agenda for the Future.” Journal of Management 36 (1): 256–280. doi:10.1177/0149206309350776.

- Baum, J. A. C., T. Calabrese, and B. S. Silverman. 2000. “Don’t Go it Alone: Alliance Network Composition and Startups’ Performance in Canadian Biotechnology.” Strategic Management Journal 21 (3): 267–294. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(200003)21:3<267::AID-SMJ89>3.0.CO;2-8.

- Bhalla, A., and S. Terjesen. 2013. “Cannot Make do Without You: Outsourcing by Knowledge-Intensive new Firms in Supplier Networks.” Industrial Marketing Management 42 (2): 166–179. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2012.12.005.

- Bjørgum, Ø, L. Aaboen, and A. Fredriksson. 2021. “Low Power, High Ambitions: New Ventures Developing Their First Supply Chains.” Journal of Purchasing & Supply Management 27 (1): 100670. doi:10.1016/j.pursup.2020.100670.

- Brettel, M., A. Engelen, T. Müller, and O. Schilke. 2011. “Distribution Channel Choice of New Entrepreneurial Ventures.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 35 (4): 683–708. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00387.x.

- Bustamante, C. V. 2019. “Strategic Choices: Accelerated Startups’ Outsourcing Decisions.” Journal of Business Research 105: 359–369. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.06.009.

- Denzin, K., and Y. S. Lincoln. 1994. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Di Stefano, G., M. A. Peteraf, and G. Verona. 2010. “Dynamic Capabilities Deconstructed: A Bibliographic Investigation Into the Origins, Development, and Future Directions of the Research Domain.” Industrial and Corporate Change 19 (4): 1187–1204. doi:10.1093/icc/dtq027.

- Dubé, L., and G. Paré. 2003. “Rigor in Information Systems Positivist Case Research: Current Practices, Trends, and Recommendations.” MIS Quarterly 27 (4): 597–635. doi:10.2307/30036550.

- Duchesneau, D. A., and W. B. Gartner. 1990. “A Profile of New Venture Success and Failure in an Emerging Industry.” Journal of Business Venturing 5 (5): 297–312. doi:10.1016/0883-9026(90)90007-G.

- Dutta, S. 2010. The Global Innovation Index 200–2010. Fontainebleau: INSEAD.

- Dutta, S., B. Lanvin, and S. Wunsch-Vincent, eds. 2020. The Global Innovation Index 2020: Who Will Finance Innovation? Fontainebleau: INSEAD.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. 1989. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” Academy of Management Review 14 (4): 532–550. doi:10.2307/258557.

- Ellinger, A. E., M. Natarajarathinam, F. G. Adams, J. B. Gray, D. Hofman, and K. O’Marah. 2011. “Supply Chain Management Competency and Firm Financial Success.” Journal of Business Logistics 32 (3): 214–226. doi:10.1111/j.2158-1592.2011.01018.x.

- Fauchart, E., and M. Gruber. 2011. “Darwinians, Communitarians, and Missionaries: The Role of Founder Identity in Entrepreneurship.” Academy of Management Journal 54 (5): 935–957. doi:10.5465/amj.2009.0211.

- Feng, N., C. Fu, F. Wei, Z. Peng, Q. Zhang, and K. H. Zhang. 2019. “The Key Role of Dynamic Capabilities in the Evolutionary Process for a Startup to Develop Into an Innovation Ecosystem Leader: An Indepth Case Study.” Journal of Engineering and Technology Management 54: 81–96. doi:10.1016/j.jengtecman.2019.11.002.

- Ghosh, D., P. Mehta, B. Avittathur, and U. Sarkar. 2018. “Unlocking the Potential of India’s High-Tech Start-Ups.” Supply Chain Management Review 22 (2): 8–10.

- Gilbert, B. A., P. P. McDougall, and D. B. Audretsch. 2006. “New Venture Growth: A Review and Extension.” Journal of Management 32 (6): 926–950. doi:10.1177/0149206306293860.

- Gioia, D. A., K. G. Corley, and A. L. Hamilton. 2013. “Seeking Qualitative Rigor in Inductive Research: Notes on the Gioia Methodology.” Organizational Research Methods 16 (1): 15–31. doi:10.1177/1094428112452151.

- Gligor, D., J. Feizabadi, I. Russo, M. J. Maloni, and T. J. Goldsby. 2020. “The Triple-a Supply Chain and Strategic Resources: Developing Competitive Advantage.” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 50 (2): 159–190. doi:10.1108/IJPDLM-08-2019-0258.

- Greiner, L. E. 1998. “Evolution and Revolution as Organizations Grow.” Harvard Business Review 76 (3): 55–68.

- Hasan, A. 2019. “The 5 Biggest Bottlenecks That Will Keep Your Startup From Growing.” Entrepreneur, June 6, 2019. https://www.entrepreneur.com/article/334833.

- Helfat, C. E., and M. A. Peteraf. 2003. “The Dynamic Resource-Based View: Capability Lifecycles.” Strategic Management Journal 24 (10): 997–1010. doi:10.1002/smj.332.

- Helfat, C. E., and S. G. Winter. 2011. “Untangling Dynamic and Operational Capabilities: Strategy for the (N)Ever-Changing World.” Strategic Management Journal 32 (11): 1243–1250. doi:10.1002/smj.955.

- Hora, M., and D. K. Dutta. 2013. “Entrepreneurial Firms and Downstream Alliance Partnerships: Impact of Portfolio Depth and Scope on Technology Innovation and Commercialization Success.” Production and Operations Management 22 (6): 1389–1400. doi:10.1111/j.1937-5956.2012.01410.x.

- Hyun, S., H. Lee, Y. Oh, and K. Cho. 2020. China’s Startup Ecosystem: Policy and Implications. Sejong: Korea Institute for International Economic Policy.

- Joglekar, N., and M. Lévesque. 2013. “The Role of Operations Management Across the Entrepreneurial Value Chain.” Production and Operations Management 22 (6): 1321–1335. doi:10.1111/j.1937-5956.2012.01416.x.

- Joglekar, N., M. Lévesque, and S. Erzurumlu. 2017. “Business Startup Operations.” In The Routledge Companion to Production and Operations Management, edited by M. K. Starr, and S. K. Gupta, 255–275. New York: Routledge.

- Kahl, S. J. 2014. “Associations, Jurisdictional Battles, and the Development of Dual-Purpose Capabilities.” Academy of Management Perspectives 28 (4): 381–394. doi:10.5465/amp.2013.0097.

- Kazanjian, R. K., and R. Drazin. 1989. “An Empirical Test of a Stage of Growth Progression Model.” Management Science 35 (12): 1489–1503. doi:10.1287/mnsc.35.12.1489.

- Ketchen, D. J., and C. W. Craighead. 2020. “Research at the Intersection of Entrepreneurship, Supply Chain Management, and Strategic Management: Opportunities Highlighted by COVID-19.” Journal of Management 46 (8): 1330–1341. doi:10.1177/0149206320945028.

- Kickul, J. R., M. D. Griffiths, J. Jayaram, and S. M. Wagner. 2011. “Operations Management, Entrepreneurship, and Value Creation: Emerging Opportunities in a Cross-Disciplinary Context.” Journal of Operations Management 29 (1): 78–85. doi:10.1016/j.jom.2010.12.004.

- Lévesque, M., N. Joglekar, and J. Davies. 2012. “A Comparison of Revenue Growth at Recent-IPO and Established Firms: The Influence of SG&A, R&D and COGS.” Journal of Business Venturing 27 (1): 47–61. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2010.08.001.

- Makkonen, H., M. Pohjola, R. Olkkonen, and A. Koponen. 2014. “Dynamic Capabilities and Firm Performance in a Financial Crisis.” Journal of Business Research 67 (1): 2707–2719. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.03.020.

- Manikas, I., B. Sundarakani, and M. Shehabeldin. 2022. “Big Data Utilisation and its Effect on Supply Chain Resilience in Emirati Companies.” International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications, doi:10.1080/13675567.2022.2052825.

- Marsillac, E., and J. J. Roh. 2014. “Connecting Product Design, Process and Supply Chain Decisions to Strengthen Global Supply Chain Capabilities.” International Journal of Production Economics 147 (Part B): 317–329. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2013.04.011.

- McKelvie, A., and J. Wiklund. 2010. “Advancing Firm Growth Research: A Focus on Growth Mode Instead of Growth Rate.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 34 (2): 261–288. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00375.x.

- Mentzer, J. T., T. P. Stank, and T. L. Esper. 2008. “Supply Chain Management and its Relationship to Logistics, Marketing, Production, and Operations Management.” Journal of Business Logistics 29 (1): 31–46. doi:10.1002/j.2158-1592.2008.tb00067.x.

- Miles, M. B., and A. M. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Morash, E. A., C. Dröge, and S. Vickery. 1996. “Boundary Spanning Interfaces Between Logistics, Production, Marketing and New Product Development.” International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management 26 (8): 43–62. doi:10.1108/09600039610128267.

- Nelson, R. R., and S. G. Winter. 1982. An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Sabahi, S., and M. M. Parast. 2020. “Firm Innovation and Supply Chain Resilience: A Dynamic Capability Perspective.” International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications 23 (3): 254–269. doi:10.1080/13675567.2019.1683522.

- Salimath, M. S., J. B. Cullen, and U. N. Umesh. 2008. “Outsourcing and Performance in Entrepreneurial Firms: Contingent Relationships with Entrepreneurial Configurations.” Decision Sciences 39 (3): 359–381. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5915.2008.00196.x.

- Sandberg, E., and M. Abrahamsson. 2011. “Logistics Capabilities for Sustainable Competitive Advantage.” International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications 14 (1): 61–75. doi:10.1080/13675567.2010.551110.

- Santos, F. M., and K. M. Eisenhardt. 2009. “Constructing Markets and Shaping Boundaries: Entrepreneurial Power in Nascent Fields.” Academy of Management Journal 52 (4): 643–671. doi:10.5465/amj.2009.43669892.

- Sapienza, H. J., E. Autio, G. George, and S. A. Zahra. 2006. “A Capabilities Perspective on the Effects of Early Internationalization on Firm Survival and Growth.” Academy of Management Review 31 (4): 914–933. doi:10.5465/amr.2006.22527465.

- Schilke, O. 2014. “On the Contingent Value of Dynamic Capabilities for Competitive Advantage: The Nonlinear Moderating Effect of Environmental Dynamism.” Strategic Management Journal 35 (2): 179–203. doi:10.1002/smj.2099.

- Sebastiao, H. J., and S. L. Golicic. 2008. “Supply Chain Strategy for Nascent Firms in Emerging Technology Markets.” Journal of Business Logistics 29 (1): 75–91. doi:10.1002/j.2158-1592.2008.tb00069.x.

- Shepherd, D. A., and M. Gruber. 2021. “The Lean Startup Framework: Closing the Academic–Practitioner Divide.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 45 (5): 967–998. doi:10.1177/1042258719899415.

- Shepherd, D. A., and H. Patzelt. 2022. “A Call for Research on the Scaling of Organizations and the Scaling of Social Impact.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 46 (2): 255–268. doi:10.1177/1042258720950599.

- Song, M., K. Podoynitsyna, H. Van Der Bij, and J. I. Halman. 2008. “Success Factors in New Ventures: A Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 25 (1): 7–27. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5885.2007.00280.x.