?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

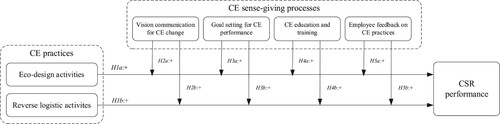

The circular economy (CE) has recently emerged as an innovative business model for firms to transform corporate social responsibility (CSR) into actions. Existing research tends to examine the CSR advantages of short-term CE practice adoptions, remaining silent on the benefits and drivers of their long-term implementation. This study fills the gaps by investigating the impact of the long-term adoption of eco-design (ECO) and reverse logistic (RL) practices on firm CSR performance and exploring the moderating roles of four sense-giving activities. Using a balanced panel dataset of 132 manufacturing public firms in China and a fixed-effects model, we find that: 1) the frequency of ECO and RL practice adoptions significantly improves firm CSR performance; 2) goal setting for CE performance, CE education and training, and employee feedback on CE practices positively moderate the RL-CSR relationship, while employee feedback on CE practices positively moderates the ECO-CSR relationship. This study has significant implications for both research and practice in the increasingly important domains of CE and CSR management.

1. Introduction

The circular economy (CE) and corporate social responsibility (CSR) have been two hot topics in the research on firms’ sustainable development (Mazzucchelli et al. Citation2022). CE advocates for a transformation from linear and open-ended production (input–output–waste) to a resource-conserving and efficient closed loop, which allows the reduction of resource usage and waste production (Ghisellini, Cialani, and Ulgiati Citation2016; Jia et al. Citation2020a). For example, BMW is committed to providing a future in which ‘vehicles are made entirely from secondary materials and are designed from the outset with disassembly and optimal recycling in mind’ on their international websiteFootnote1. In practice, the concept of CE has been widely integrated into firms’ CSR agenda, which is conducive to putting their responsibility into practice (Kumar et al. Citation2022).

A large body of literature has provided theoretical and empirical evidence that the CE model leads to better CSR performance (Korhonen, Honkasalo, and Seppala Citation2018). CSR performance is a concentration of firms’ sustainability in economic, environmental, and social aspects (Yang et al. Citation2019; Dey et al. Citation2020; Wei et al. Citation2023). Korhonen, Honkasalo, and Seppala (Citation2018) theoretically analyzed that a CE model may achieve multiple wins in terms of material and energy saving, pollution reduction, reputation enhancement, new employment opportunities, and sharing economy, etc. Based on these wins, many studies have empirically proved that the adoption of a CE principle by firms improved their economic, environmental, social, and overall CSR performance (Zhu, Geng, and Lai Citation2011; Yang et al. Citation2019; Jabbour et al. Citation2020; Khan et al. Citation2021a).

However, some mixed results have emerged, leaving the relationship between CE practices and firm performance unclear. Several studies claimed that many firms failed to obtain economic gains from CE in the short run (Antonioli et al. Citation2022; Aldrighetti et al. Citation2022). This may be due to the soaring cost caused by early investment in CE and the difficulties in improving firm performance only after a few years of CE implementation (Aldrighetti et al. Citation2022). There may also be a significant threshold investment for firms to benefit from investing in the CE (Demirel and Danisman Citation2019). Termeer and Metze (Citation2019) emphasised that substantial CE changes require the long-term accumulation of small-scale CE practices. Nevertheless, most empirical studies used cross-sectional survey data to examine the CE’s impact on firm performance, which may not help in observing the long-term CE practice adoptions’ impact on firm performance (Millar, McLaughlin, and Borger Citation2019; Karuppiah et al. Citation2021).

Despite the potential benefits of CE, many firms still find it difficult to translate CE into their strategies, structures, and operations to gain CSR advantages (Urbinati, Chiaroni, and Chiesa Citation2017; Khan, Daddi, and Iraldo Citation2020). Their business model is deeply rooted in the linear and economic return maximization approach, hindering seeking the CE and CSR advantage (Accenture Citation2014). A strand of literature has thus highlighted that firm members’ sufficient understanding and recognition towards CE and CSR are critical, especially in the long term (Ravi and Shankar Citation2005; González-Torre et al. Citation2010; Centobelli et al. Citation2021). These studies have theoretically and fragmentarily explored the role of top management commitment (Kirchherr et al. Citation2018; Zhou et al., Citation2022), shared narratives (Hussain and Malik Citation2020; Sendlhofer and Tolstoy Citation2022), and long-term orientation (Moktadir et al. Citation2020) in winning member’s spiritual support towards CE and CSR. Still missing is quantitative research that describes the cognitive mechanisms at play in integrating CE activities into firms to achieve CSR advantages (Khan, Daddi, and Iraldo Citation2020).

Eco-design (ECO) and reverse logistics (RL) practices are the two most important CE practices at the firm level (Urbinati, Chiaroni, and Chiesa Citation2017; Liu et al. Citation2023), because they represent the front and the back end of production, and are critical for shaping a closed-loop supply chain and fulfilling a CE (Yang et al. Citation2019). This study focuses on ECO and RL practices and examines whether their long-term implementation improves firm CSR performance to address the first gap. Following Bergh and Lim (Citation2008), the long-term implementation of ECO (RL) practices is measured as the frequency of adopting them in a past period. From an organizational learning view, long-run CE practice adoptions may bring an ‘experience cumulative’ effect (Demirel and Danisman Citation2019) and a ‘complementary’ effect between varying CE practices (Al-Sheyadi, Muyldermans, and Kauppi Citation2019), and thus extend CSR competitiveness.

To address the second gap, we employ the concept of sense-giving proposed by Gioia and Chittipeddi (Citation1991) to explore the role of the cognition of organizational members in enabling a CE shift. Sense-giving is defined as a process of sharing one’s interpretations with others to shape a mutual understanding of some reality (Gioia and Chittipeddi Citation1991). The concept has been employed in strategic change studies (Kraft, Sparr, and Peus Citation2018) and in corporate sustainability studies (Bhappu and Schultze Citation2019; Tisch and Galbreath Citation2019; Sendlhofer and Tolstoy Citation2022). The CE is often viewed as a strategic change for sustainability (Murray, Skene, and Haynes Citation2017). However, Lazarevic and Valve (Citation2017) noted that this concept is rarely explored in the context of CE. We thus conceptualize four sense-giving activities in the context of a CE: 1) vision communication for CE change; 2) goal setting for CE performance; 3) CE education and training; and 4) employee feedback on CE practices. Then, we empirically test their role in facilitating the ECO- and RL-CSR relationships.

In summary, this study bridges the research gaps above by answering the following two research questions (RQs):

RQ1: Is there a positive relationship between the long-term implementation of ECO (or RL) practices and firm CSR performance?

RQ2: Could vision communication for CE change, goal setting for CE performance, CE education and training, and employee feedback on CE practices enhance the above relationship?

To answer the RQs, using the Chinese Research Data Services Platform (CNRDS), China Stock Market & Accounting Research Database (CSMAR) and Ranking CSR rating (RKS) database, we collected information on 132 listed manufacturing firms in China from 2013 to 2018 and applied a fixed-effects model. We focus on Chinese manufacturing firms for two main reasons. First, China has accumulated more than a decade of CE implementation experience (Geng, Sarkis, and Ulgiati Citation2016), providing relatively rich data for this research. As early as 2008, China enacted the Circular Economy Promotion Law (Zhu, Geng, and Lai Citation2011), which is a pioneer in the adoption of CE-oriented legislation. Second, manufacturing firms are widely studied in the CE literature due to their higher impacts in terms of CSR, such as environmental pollution and employee unemployment (De los Rios and Charnley Citation2017; Chen et al. Citation2022).

This study makes the following three contributions. First, it contributes to a better understanding of the relationship between CE practices and CSR performance from a long-term perspective. In this regard, this study finds that a higher frequency of CE practice adoptions results in better CSR performance. Second, the research extends the application of sense-giving to a CE context and provides guidelines for firms to embed the CE in their CSR agenda. Drawing on sense-giving, we find that employee feedback on CE practices moderates the ECO-CSR relationship, while goal setting for CE performance, CE education and training, and employee feedback on CE practices moderate the RL-CSR relationship. Third, this study enriches the literature on the effect of CE practices on firm performance by analysing secondary and panel data retrieved from CSR reports rather than primary and cross-sectional data, representing a methodological contribution to the literature.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the theoretical background and hypotheses. The variables and methods are described in Section 3. Section 4 describes the empirical results and analysis. Section 5 discusses the research findings and concludes with practical implications.

2. Theoretical background and hypothesis development

2.1 Long-term implementation of CE practices and CSR performance

The concept of CE is defined as a paradigm of production and consumption that aims to maximise resource value, cost reduction and environmental improvements by promoting the recycling of energy and material (Geng, Sarkis, and Ulgiati Citation2016; Jia et al. Citation2020a). It is a sustainable alternative to the traditional linear production of ‘resource–product–waste’ and achieves better harmony among the economy, environment and society (Ghisellini, Cialani, and Ulgiati Citation2016; De Jesus and Mendonça Citation2018). CSR is a multifaceted concept with a focus on profit enhancement, environmental protection, consumer and labour welfare, and a series of related areas (McGuinness, Vieito, and Wang Citation2017). The CE and CSR are increasingly interconnected and converging (Kuo, Yeh, and Yu Citation2011; Stewart and Niero Citation2018; Kumar et al. Citation2022).

At the firm level, the CE model mainly involves eco-design, green procurement, cleaner production, and waste management practices (Ghisellini, Cialani, and Ulgiati Citation2016). Among them, eco-design (ECO) and reverse logistics (RL) activities play the most crucial role because of their complementarity in forming a circular supply chain (Yang et al. Citation2019). This study focuses on ECO and RL practices.

ECO practices refer to the design of products (or processes) for the reduction, reuse, recovery, and recycling of material and energy (Zhu and Sarkis Citation2004). They require many innovations that minimise the negative environmental impacts while maintaining functional and safety requirements (Choi and Hwang Citation2015). RL practices include consolidating product returns from multiple locations, recovering valuable components from used materials, and making refurbished products for sale (Choi and Hwang Citation2015). They focus on waste recovery and aim to extract the remaining value from abandoned products (Fuente, Ros, and Cardós Citation2008).

CSR performance comprehensively reflects firm (1) economic performance (e.g. sales and profit), (2) environmental performance (e.g. pollution reduction and resource conservation), and (3) social performance (e.g. employment and human rights) (Firoozi and Keddie Citation2022; Liu et al. Citation2022). The literature relevant to CE practices emphasises their benefits in these three aspects. The economic benefits include a cost reduction caused by the consumption of energy and raw materials, waste recycling, control of emissions and payment of environmental taxes (Jabbour et al. Citation2020). Investing in CE could also enhance the brand reputation and market value of firms (Mazzucchelli et al. Citation2022). The environmental advantages of CE include reductions in material consumption, waste generation, and emissions (Khan et al. Citation2021a). The social benefits include new job opportunities within operations related to CE, an increased sense of community, and equitable access to goods and services (Korhonen, Honkasalo, and Seppala Citation2018).

Many empirical studies have revealed that ECO and RL practices can improve several aspects of CSR performance (Yang et al. Citation2019). Jabbour et al. (Citation2020) claimed that CE principles positively affect a firm economic, environmental, and social performance. Dey et al. (Citation2020) also revealed that two CE fields of action—‘make’ (including ECO practices) and ‘use’ (including RL practices)—are positively correlated with economic, environmental and social performance using survey data of 130 UK small and medium-sized enterprises. Zhu, Geng, and Lai (Citation2011) and Khan et al. (Citation2021a) found positive effects of ECO and RL practices on environmental and economic performance improvements using survey data of Chinese firms. Research on ECO (RL) practices’ impact on overall CSR performance is relatively scarce (Yang et al. Citation2019).

Notably, most CE scholars highlight that the CE change is not achieved overnight but is enabled through continuous investment in the long run (Teixeira and Canciglieri Citation2019; Takacs, Brunner, and Frankenberger Citation2022). Short-term CE practice adoptions would limit the amount of firm CE investment and experience (Karuppiah et al. Citation2021; Aldrighetti et al. Citation2022). This is echoed by Antonioli et al. (Citation2022) who empirically proved that many firms failed to obtain economic gains from CE because of the soaring costs from the CE investment CE in the short run using data from Italian manufacturing firms. Furthermore, Gholami et al. (Citation2013) found that only long-term adoption of green information systems was positively related to corporate environmental performance. Demirel and Danisman (Citation2019) found that a threshold investment (more than 10% of revenues) into CE is required for firms to benefit from the CE investment. Termeer and Metze (Citation2019) advocated that a series of small CE-related practices can accumulate into transformative change through mechanisms such as goals, learning by doing, and coupling.

However, most above studies use cross-sectional survey data to investigate the short-term impact of CE practices on firm performance because they merely considered performance improvement caused by CE practices implemented during or just before the reporting period (e.g. Yang et al. Citation2019). This results in little understanding of the impact of long-term CE practice adoptions on firm performance (Millar, McLaughlin, and Borger Citation2019).

The long-term implementation of ECO (RL) practices can be measured as the frequency of the firm adopting them over a past period (Bergh and Lim Citation2008). More frequent ECO (RL) practice adoptions mean a continuous investment in CE. The same measurement has been widely employed to represent the accumulation of experience in many organisational learning articles (e.g. Gao and Pan Citation2010; Ding Citation2014). Organisational learning is defined as a process where experience is obtained from performing a task, which consequently influences the firm behaviours and performance (Bergh and Lim Citation2008). Firms can acquire experience from different sources, including direct knowledge, previous activities and decisions, and other firms’ experience, in which learning-by-doing is one of the most important mechanisms (Gao and Pan Citation2010). Based on this, continuous CE practice adoptions allow firms to iterate and update the experience towards CE change and to achieve better CSR performance (Al-Sheyadi, Muyldermans, and Kauppi Citation2019; Termeer and Metze Citation2019).

The organisational learning view has been used to help explain firm CE change. For instance, Agyabeng-Mensah et al. (Citation2021) found that inter- and intra-organisational learning processes could support the adoption of zero waste practices and the achievement of CSR. Its orientation is also argued to lead to high-level eco-innovations (Ul-Durar et al. Citation2023). This study holds on that a higher frequency of firms adopting ECO (RL) practices contributes to gaining more CE experience, which is called an ‘experience cumulative’ effect (Demirel and Danisman Citation2019; Chen et al. Citation2023). In that case, firms have sufficient time to internalize CE knowledge and facilitate satisfactory CE practices. Besides, certain combinations of different ECO and RL practices are complementary, such as the design for easy disassembly and disassembly activities (Yang et al. Citation2019). A higher frequency of adopting ECO (RL) practices increases the likelihood of such combinations occurring, which is called a ‘complementary’ effect (Al-Sheyadi, Muyldermans, and Kauppi Citation2019). These two effects can promote a substantial transformation to a CE and thus help companies gain CSR advantages (Teixeira and Canciglieri Citation2019; Termeer and Metze Citation2019). In summary, we focus on the relationship between the long-term implementation of CE practices and overall CSR performance and put forward our first set of hypotheses.

H1a (H1b): There is a positive correlation between the long-term implementation of ECO (RL) practices and CSR performance.

2.2 Sense-giving

Sense-giving is defined as ‘the process of attempting to influence the sensemaking and meaning construction of others towards a preferred redefinition of organisational reality’ (Gioia and Chittipeddi Citation1991, 442). It is essentially an act of persuasion to win the understanding and support of multiple stakeholders for change. It helps to provide convincing interpretations of reality towards change while shutting down alternative interpretations, and finally normalising and legitimising these organisational realities (Fiss and Zajac Citation2006). It also plays a significant role in delivering values and norms (Balogun, Bartunek, and Do Citation2015), reshaping organisational members’ identities and images (Gioia and Thomas Citation1996), and stimulating their emotions and attitudes (Hill and Levenhagen Citation1995).

Sense-giving is primarily the task of leaders because of their promising insights, great discretion, and superior information (Balogun, Bartunek, and Do Citation2015). During a strategic change, leaders need to communicate downwards the demand for and the direction of that change and manage employees’ change-related uncertainty (Kraft, Sparr, and Peus Citation2018). In addition, sense-giving is not simply top-down, as employees may have their own interpretations and values and, thus, resist efforts from leaders to influence the change (Sonenshein Citation2010). Sense-giving should be conceptualised as ‘the contextualised outcome of interactive rather than unidirectional process’ between leaders and employees in firms (Foldy, Goldman, and Ospina Citation2008, 515).

Prior studies on sense-giving primarily apply the case study approach and offer vivid descriptions of sense-giving tactics. Both narrative and substantive sense-giving tactics are often used to reduce environmental stress and clarify the necessity of change and its goals to employees (Kraft, Sparr, and Peus Citation2018). The former includes the use of symbolism (Gioia and Thomas Citation1996), metaphors (Hill and Levenhagen Citation1995), and adapting explanations (Rouleau Citation2005). In Weiser (Citation2020), the latter mainly refers to the modification of organisational structures, processes, and practices.

2.3 Sense-giving in a CE

According to Maitlis and Lawrence (Citation2007), sense-giving is triggered by ambiguity, uncertainty, and complexity. Sense-giving could happen in a CE when a new CE model is introduced into a firm as a strategy for the following three reasons (Murray, Skene, and Haynes Citation2017). First, the firm may become uncertain about the nature and consequences of a CE because they know too little about it or, conversely, be overloaded with information that creates a situation of ambiguity. Second, adopting CE needs to be supported by joint efforts from various departments and is complex (Ghisellini, Cialani, and Ulgiati Citation2016). Third, sense-giving also easily happens when a change is highly controversial (Fiss and Zajac Citation2006). Shifting to a CE could be at high risk and controversial in a firm because of its high upfront costs and the firm’s profit-oriented culture that does not encourage efficient resource use and pollution mitigation (González-Torre et al. Citation2010; De Jesus and Mendonça Citation2018). Hence, a sense-giving perspective provides a suitable theoretical lens to study CE.

The sense-giving process of a strategic change could be described as a range of activities (Maitlis and Lawrence Citation2007). In Gioia and Chittipeddi (Citation1991, 443), the sense-giving process ‘communicates the vision and the values underlying it’ through hypothetical scenario presentations. Carton (Citation2017) emphasised the role of concrete objectives in helping individuals perceive a connection between daily work and ultimate aspirations. To further connect employees’ everyday work to these goals, Inkpen (Citation2008) and Boscari, Danese, and Romano (Citation2016) focused on sense-giving elements in education and training activities, which were argued to provide employees with further interpretations and meaning of various policies proposed during the change. Finally, employee feedback is often considered an upwards sense-giving activity that the role of employees’ own interpretations (Beverland, Micheli, and Farrelly Citation2016; Kraft, Sparr, and Peus Citation2018; Robert and Ola Citation2020). Inspired by these, we summarize four sense-giving activities against the background of a CE change: (1) vision communication for CE change; (2) goal setting for CE performance; (3) CE education and training; and (4) employee feedback on CE practices.

2.3.1 Vision communication for CE change

Vision communication is defined as communicating inspiring images of an abstract future to organisational members, and it aims to convince them to pursue these futures (Stam, Lord, and Wisse Citation2014). An example is Unilever’s vision ‘to make sustainable living commonplace' (Gochmann, Stam, and Shemla Citation2022). It is often regarded as the initial sense-giving activity to organise multiple stakeholders for strategic change (Gioia and Chittipeddi Citation1991; Carton Citation2017). Leaders generally communicate the nature of the vision, its values, and the actual changes that they want to make (Gioia and Chittipeddi Citation1991). In this way, vision communication contributes to seeking consensus with and motivating employees by sharing the values of change with them (Carton Citation2017). Most importantly, it provides a structural blueprint and initial interpretation of the change for employees, which reduces their tension in the face of uncertainty regarding the change (Mumford et al. Citation2007).

We claim that vision communication for CE change is the starting activity of CE sense-giving when adopting CE within a firm. First, it may help to create richly mutual narratives related to CE and promote the formation of the values and initial interpretations of shifting to a CE (Mantere, Schildt, and Sillince Citation2012), which may foster a collectively positive attitude towards adopting CE practices (Hill and Levenhagen Citation1995; Jia et al. Citation2020b). Second, a sustainable image of a CE future and a collective direction for CE adoptions towards that future may be provided for employees as well, which plays a role in removing their uncertain and anxious emotions about what CE is and what the firm will be if it adopts CE (Kraft, Sparr, and Peus Citation2018). For instance, Dell delivered an ambitious claim to ‘take back as much as we produce’ on its websiteFootnote2, which promotes the understanding of ‘circular’ well. In this way, the CE practices of firms could be activated by vision communication for CE transformations to achieve better CSR performance. Therefore, we put forward our second set of hypotheses.

H2a (H2b): Vision communication for CE change enhances the correlation between ECO (RL) practices and CSR performance.

2.3.2 Goal setting for CE performance

Goal setting refers to setting short-term targets for specific organisational tasks and performance, usually ranging from several months to years (Gochmann, Stam, and Shemla Citation2022). It is similar to vision communication in pointing to the future but more specific, time-constrained, and reachable (Locke and Latham Citation2009). From the perspective of sense-giving, leaders give concrete meaning to employees’ everyday work by transferring the vision to many short-term goals (Fiss and Zajac Citation2006), avoiding the ‘vision trap’ that occurs when a vision lacks details (Langeler Citation1992). Moreover, short-term goals only highlight a select few critical junctures’ that stretch between daily work and the vision, thereby helping employees focus attention, track progress, and mentally save considerable time and tasks (Carton Citation2017).

We consider the goal setting for CE performance as the second activity of CE sense-giving. In practice, leaders often develop a system of CE target management that includes a series of related tasks and performance metrics. Many scholars have pointed out that the lack of effective metrics or indicators causes the failure of CE activities (Ghisellini, Cialani, and Ulgiati Citation2016; Veleva, Bodkin, and Todorova Citation2017). According to sense-giving, employees capture the narratives of these CE-related tasks and performance metrics and adopt them as their concrete interpretations of CE (Yamoah et al. Citation2022). Then, these tasks and performance metrics would be gradually distributed to employees so that everyone only needs to complete a small part among them on time without much stress and burden. When reaching corresponding performance metrics, employees might obtain some relatively concrete meanings from their own tasks. Therefore, goal setting for CE performance may promote firms’ CE practices, which helps firms achieve better CSR performance. We then put forward our third set of hypotheses.

H3a (H3b): Goal setting for CE performance enhances the correlation between ECO (RL) practices and CSR performance.

2.3.3 CE education and training

Many prior studies defined education and training as activities that provide employees with the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes (Jabbour, Santos, and Nagano Citation2010). Recently, much attention has been given to the sense-giving elements in these activities, in which leaders tend to further explain the meaning of change policies to employees (Boscari, Danese, and Romano Citation2016). Benbenisty and Luria (Citation2021) argued that helping employees comprehend the meaning of policies rather than simply conveying knowledge may be more significant because employees may resist knowledge transfer due to differences in values (Kostova and Roth Citation2002). According to sense-giving, education and training first provide further explanations for the meaning and importance of policies and, thus, foster employees’ active attitudes towards change (Inkpen Citation2008). Then, it plays a role in transferring necessary context and knowledge, which helps employees understand how to execute policies and reduce possible ambiguity.

We view CE education and training as the third sense-giving activity that provides meaning and further interpretations for CE practices. Unlike prior studies, we regard imparting the necessary knowledge and skills needed to carry out CE policies in education and training activities (Daily, Bishop, and Massoud Citation2012; Lara and Phillipa Citation2015; Jabbour et al. Citation2019) as a means of providing a deeper understanding of CE change to employees. Moreover, we emphasise that it helps enhance employees’ recognition of the meaning and the necessity of adopting CE practices (Mumford et al. Citation2007; Yamoah et al. Citation2022). Therefore, CE education and training can improve CE practices and help firms obtain better CSR performance. Here, we put forward our fourth set of hypotheses.

H4a (H4b): CE education and training enhance the correlation between ECO (RL) practices and CSR performance.

2.3.4 Employee feedback on CE practices

We define employee feedback as the information employees provide to leaders to improve practices. Such feedback may be about problems that arise in practices and suggestions (Marinova, Ye, and Singh Citation2008). Many recent studies regard it as a bottom-up sense-giving activity to reduce interpretation gaps about change between leaders and employees (Beverland, Micheli, and Farrelly Citation2016; Robert and Ola Citation2020) because employees have direct contact with daily production practices and may obtain more frontline information (Marinova, Ye, and Singh Citation2008). For instance, Beverland, Micheli, and Farrelly (Citation2016) regarded employee feedback as ‘resourceful sense-giving’, which helped to expand mutual horizons and create shared interpretations. It may not only urge leaders to reflect on and improve some policies (Kraft, Sparr, and Peus Citation2018) when employees report that leaders’ narrations fail to fit real reality (e.g. when performance is below goal levels) but also encourage employees to possess ‘authorship’ and create their own meaningful interpretations of their work (Gorli, Nicolini, and Scaratti Citation2015).

We regard employee feedback on CE practices as a fourth sense-giving activity in which employees’ creativity plays a leading role. In practice, leaders may promote employee feedback on CE practices in a variety of ways within a firm. For instance, leaders may hold regular staff seminars and employee meetings to communicate with management, R&D, marketing, and production staff and collect problems arising in the process of CE practices. Leadership mailboxes are also often used to encourage employees to submit their suggestions for improving CE practices. These feedback activities not only stimulate employees to create and share their own interpretations of CE but also urge leaders to improve their interpretations and narratives when making CE policies. Hence, employee feedback on CE practices may also help firms facilitate CE practices to obtain better CSR performance. We then put forward our fifth set of hypotheses.

H5a (H5b): Employee feedback on CE practices enhances the correlation between ECO (RL) practices and CSR performance.

3. Data and methodology

3.1 Identification strategy

Examining the effect of long-term implementation of ECO (RL) practices on CSR performance may be difficult due to endogeneity concerns, including the omitted variable bias, sample selection bias, and two-way causality. For omitted variable bias, We use a balanced panel dataset and a fixed-effects model to capture any unobserved heterogeneity and unobserved time effects. We then control as many variables as possible, including firm-level and industry-level variables. In the sample screening process, we eliminate a large number of firms due to missing data on CSR scores, causing a sample selection bias concern. We thus use a standard Heckman (Citation1979) two-step procedure which allows us to control for the unobservable factors that make sample inclusion more likely. The two-way causality is likely to occur because firms with higher CSR performance may obtain more financing to invest in CE (Cheng, Loannou, and Serafeim Citation2014). The instrumental variable (IV) method is used to further address this endogeneity concern. In addition, the panel Tobit model is adopted to reduce estimation inconsistency caused by the limited dependent variable with a value between 0 and 100 (Yi et al. Citation2020). Several alternative measurements of independent variables are also employed to perform further robustness tests.

3.2 Sample and data collection

We base our sample selection on all manufacturing firms listed on the Shanghai and Shenzhen Stock Exchanges. Our data is collected from multiple sources: 1) the Research Data Services Platform (CNRDSFootnote3); 2) the China Stock Market & Accounting Research Database (CSMARFootnote4); and 3) the Rankins CSR rating (RKSFootnote5) database. The CNRDS is an open platform for high-standard Chinese business research data. We utilize it to obtain data on ECO and RL practices, as well as on employee feedback channels. The CSMAR provides much corporate financial and governance information for this study. It also features a firm-level environmental management dataset that offers data on environmental protection since 2013. The RKS database provides annual CSR rating scores from 2009 to 2018 and has been widely applied in CSR literature (e.g. McGuinness, Vieito, and Wang Citation2017; Yang et al. Citation2019). We collect the data on CSR performance from RKS. We set sample period between 2013 and 2018 to ensure the availability of all data.

When screening sample firms, we initially selected 2709 manufacturing listed firms. Then, among them, we eliminated sample firms without CSR score data for 2013–2018 and obtained 269 sample firms. Next, we omitted all sample companies that did not consistently report their ECO and RL practice adoptions from 2008 to 2018. Ultimately, we got the final sample consisting of 792 firm-year observations of 132 companies during 2013–2018. The sample screening process and industry distribution of companies (two-digit industry codes) are reported in .

Table 1. Sample screening and distribution.

3.2.1 Dependent variable

CSR performance is the dependent variable in this study (denoted as CSR). We use the CSR rating score from RKS, the leading independent CSR-rating entity in China. The CSR score consists of over 70 indicators, which are mainly derived from Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) standards but adapted for the Chinese context (McGuinness, Vieito, and Wang Citation2017). These indicators can be divided into three groups—macrocosm, content and technical—all of which are separate from our independent variables (Yang et al. Citation2019). The macrocosm group includes firm strategy, governance and stakeholder participation in CSR activities. The content focuses on economic performance, labour and human rights, the environment, fair operation, customers and community participation. The technical component concerns the reliability, normalisation and availability of CSR reports. It ranges from 0 to 100 points, reflecting a firm’s performance on CSR. We choose this score to reflect firms’ CSR performance following prior studies (Yang et al. Citation2019).

3.2.2 Independent variables

Data regarding ECO and RL practices are taken from CNRDS. ECO practice data in this database is defined as whether a firm claims that they develop or apply innovative environmentally friendly products, equipment or technologies, while RL practice data is defined as whether firms claim that they implement RL policies or measures in their CSR report. To establish the timeline for corporate adoption of CE practices, we consider the enactment of the Chinese Circular Economy Promotion Law in 2008 as the starting point. Following Bergh and Lim (Citation2008), the long-term implementation of ECO (RL) practices (defined as ECOi[08,t] and RLi[08,t]) is measured as the frequency of a firm adopting them from 2008 to year t. The specific calculations are as follows:

Where ECOi[08,t] (RLi[08,t]) represents the number of times the company i has conducted ECO (RL) practices from 2008 to year t. ECOik (RLik) indicates whether the firm i adopted ECO (RL) practices in year k.

3.2.3 Moderating variables

Vision communication for CE change (denoted as Vision). We measure Vision as a dummy variable that equals 1 if the firm develops a vision for environmental protection and 0 otherwise, which is obtained from CSMAR.

Goal setting for CE performance (denoted as Goal). Goal is also measured as a dummy variable that takes the value 1 if the firm sets some future goals for protecting the environment and 0 otherwise, which is also obtained from CSMAR.

CE education and training (denoted as Education). Education is measured as a dummy variable that equals 1 if the firm organises some educational activities about environmental protection and 0 otherwise, which is obtained from CSMAR.

Employee feedback on CE practices (denoted as Feedback). Feedback is measured as a dummy variable that equals 1 if the firm provides employees with feedback channels related to CSR problems, which is collected from CNRDS.

It should be noted that our proxy variables connect directly with environmental protection or CSR rather than CE, which would cause some doubts about their validity. In fact, the ‘Circular Economy Promotion Law’ enacted in 2008 in China regarded the purpose of CE as ‘protecting the natural environment and realizing sustainable development’ (Geng et al. Citation2011, 216). Moreover, the concept of CE is often investigated given the context of academic debates about CSR (Murray, Skene, and Haynes Citation2017). In practice, most Chinese companies disclose their CE practices in the environmental information disclosure section of their CSR reports (Kuo, Yeh, and Yu Citation2011). Hence, we claim that the above measurements of variables are suitable.

To facilitate understanding of these four moderators from a sense-giving perspective, some relevant narratives from the CSR reports of 5 automobile companies in our sample are collected in . It is easy to see that these narratives support our theoretical analyses of four CE sense-giving activities to a certain extent.

Table 2. Examples of relevant sense-giving narratives of four moderators.

3.2.4 Control variables

We then control for the variables that might affect CSR performance. We first control the following firm financial variables according to Firoozi and Keddie (Citation2022). Firm Size (defined as Size) is the logarithm of the total number of employees plus 1. Firm Age (defined as Age) is the number of years since the stock became public. Return on equity (denoted as Roe) is net income divided by net assets. Asset-liability ratio (denoted as Leverage) is the percentage of total end liabilities divided by total assets.

Following McGuinness, Vieito, and Wang (Citation2017), we use corporate governance variables, including the number of female directors (denoted as Female), the number of independent directors (denoted as Independent), and the executive shareholding ratio (denoted as Executive). In general, female directors tend to be more compassionate and less materialistic, and care more about social and community needs (Rao and Tilt Citation2016). Glass, Cook, and Ingersoll (Citation2016) found that corporates with more female directors obtain better CSR performance. The presence of independent directors helps to reduce agency conflicts and ensure effective monitoring, and they usually have more information and knowledge of CSR management (Beji et al. Citation2021). Executive shareholding contributes to binds the Executives’ interests to those of the corporate, and makes them focus on corporate long-term performance (Jiang et al. Citation2021). Johnson and Greening (Citation1999) found a positive relationship between managerial ownership and corporate social performance in terms of environmental and product quality.

Moreover, we consider the intensity of industry competition using the Herfindahl–Hirschman Index (denoted as HHI), which refers to the quadratic sum of a firm’s assets divided by its competitors’ total assets in the same industrial sector (Li, Li, and Sethi Citation2021). Harjoto, Laksmana, and Lee (Citation2015) found that firms operating in a more competitive market with a low HHI tend to conduct higher CSR activities as product differentiation strategies.

3.3 Descriptive statistics

The descriptive statistics for all variables and their correlations are presented in . CSR has a mean value of 40.949 and a standard deviation of 12.166. The mean value of ECOi[08,t] (RLi[08,t]) is 4.203 (3.509). Moreover, we note that ECO, RA, Size, Age, Leverage and BoardIn are positively and significantly correlated with CSR, while BoardFe has a significant and negative correlation with CSR. Roe, Executive and HHI are not significantly correlated with CSR. The post-regression tests show that multicollinearity is not an issue in this study, as all the variance inflation factors are below 2 (the highest is 1.47), which is smaller than the value of 10 (Li, Li, and Sethi Citation2021).

Table 3. Descriptive statistics and correlations of the variables.

3.4 Model specification

We develop two fixed-effects models as follows using balanced panel data to determine whether CSR performance is positively correlated with the long-term implementation of ECO (RL) practices:

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2) where subscripts i and t represent firm and year, respectively. α1 gives the estimation of the impact of long-term ECO (RL) practice adoptions on CSR performance. Xit denotes a set of control variables, including Size, Age, Roe, Leverage, Female, Independent, Executive and HHI. γi and μt represent the firm- and year-fixed effects, respectively, which we include to control for unobserved heterogeneity across different firms and years. α0 is the intercept. ϵit is the random error term.

We further add an interaction term of ECOi[08,t] (RLi[08,t]) and SGit to test the potential moderating effects:

(3)

(3)

(4)

(4) where SGit stands for Visionit, Goalit, Educationit, and Feedbackit. Other variables are defined above. Here, we focus on the coefficient α3.

4. Empirical results

4.1 Hypothesis testing

summarises the regression results of the impact of long-term ECO (RL) practice adoptions on CSR performance and the moderating effects of the four sense-giving processes. Panel A (B) presents the results on the frequency of ECO (RL) practice adoptions. The estimated coefficient of ECOi[08,t] in Column (1) is positive and significant (α1 = 0.937 with p < 0.05). Similarly, the coefficient of RLi[08,t] in Column (6) is also positive and significant (α1 = 1.175 with p < 0.01). These results show the positive impacts of ECO and RL practices on CSR performance, verifying H1a and H1b.

Table 4. Basic regression results.

Columns 2–5 provide the estimation results of the moderating effects of four CE-related sense-giving processes on the ECO-CSR relationship. Surprisingly, only the coefficient of Feedback × ECOi[08,t] (α3 = 0.412 with p < 0.05) is positive and significant, failing to verify H2a, H3a, and H4a, although confirming H5a. One probable reason is that the CE-related vision still lacks credible potential benefits and technical details to convincingly present how CE can disruptively improve specific activities and motivate managers towards ECO practices. This is echoed by Klos and Spieth (Citation2021) who noted that the workshop participants’ enthusiasm for the vision diminished shortly after technology foresight workshops. Furthermore, since ECO practices are primarily conducted by R&D staff with specialized knowledge and their own interpretations of CE, their participation in educational activities may be unnecessary or ineffective. The goals are likely to fail to improve their interpretations of CE because of their already understanding of related tasks and performance metrics. They may even be involved in the process of goal setting. However, employee feedback about ECO practices can bring valuable information to R&D staff and thus enhance ECO practices, which is consistent with Beverland, Micheli, and Farrelly (Citation2016), who argued that feedback practices can improve the work of designers.

Columns 7–10 present the estimation results of the moderating effects of four CE-related sense-giving processes on the RL-CSR relationship. The coefficients of Goal × RLi[08,t] (α3 = 0.365 with p < 0.1), Education × RLi[08,t] (α3 = 0.405 with p < 0.05) and Feedback × RLi[08,t] (α3 = 0.324 with p < 0.1) are significantly positive, verifying H3b, H4b, and H5b, respectively. However, the coefficient of the interaction of Vision × RLi[08,t] is significantly negative, failing to support H2b. One possible explanation is that the vision for CE change is too abstract and symbolic to provide sufficient interpretations for employees, failing to facilitate RL practice most of the time, which is consistent with the argument of Langeler (Citation1992). What is worse, managers’ vision and commitment to CE transition may be a form of greenwashing (Yamoah et al. Citation2022). If managers indulge in such greenwashing activities, they may diversion of funds for CE practices to other areas and thus undermine firms’ CE change (Zerbino Citation2022). collects the hypothesis results.

Table 5. Result collections of moderator analyses for sense-giving activities.

4.2 Robustness checking

4.2.1 Heckman two-step method

We use a standard Heckman (Citation1979) two-step procedure (Lim and Nguyen Citation2021) to account for a potential sample selection bias arising in the sample screening process. The RKS assesses CSR scores for about 800 companies out of over 4000 Chinese listed companies, which may lead to a sample selection bias. In the first step, the dependent variable is a dummy that equals 0 if a firm missed the final sample because of missing data on CSR scores and 1 otherwise (defined as CSR_dummy). The regression specification includes industry- and year-fixed effects and a full set of control variables: Size, Age, Roe, Leverage, Female, Independent, Executive, and HHI. The second step of the Heckman procedure includes the inverse Mills ratio (defined as IMR), which contains information from the first step to control for the unobservable factors that make sample inclusion more likely. presents the robust results (the second step only). The result of the first step can be found in Appendix 1. The coefficient of IMR is insignificant, indicating the absence of the sample selection bias.

Table 6. Heckman two-step method (the second step only).

4.2.2 Instrumental variable method

The major concern for endogeneity may arise from the two-way causality in the ECO- and RL-CSR relationships. Firms with higher CSR performance may obtain more financing to invest more in CE (Cheng, Loannou, and Serafeim Citation2014). We adopt the IVs and the two-stage least square method, which is commonly used (e.g. Li, Li, and Sethi Citation2021) to address the endogeneity concern. Following Nakamura and Steinsson (Citation2014), we initially calculate the average ratio of a firm’s adoption frequency of ECO (RL) practices to its industry’s average adoption frequency of ECO (RL) practices during the sample period. Next, the instrumental variable is measured as the product of this average ratio (a firm-specific weight) and the industry’s average adoption frequency of ECO (RL) practices. The specific calculations are as follows:

Where IV_ECOijt (IV_RLijt) represents the IV of ECOi[08,t] (RLi[08,t]). The right side of the multiplication sign stands for the average frequency of the industry j adopting ECO (RL) practices in t year. nj is the number of firms in the industry j.

We utilize the above IVs for two primary reasons: 1) the calculations demonstrate a strong correlation between the adoption frequency of ECO (RL) practices by companies and IVs, meeting the relevance requirement (Borusyak, Hull, and Jaravel Citation2022); 2) our IVs are defined as the interaction between a firm-level constant weight and an industry-level CE adoption frequency, in which unobservable omitted variables at the firm level can hardly affect the constant value nor determine the overall level of the corporate’s industry, satisfying the exogenous requirement (Nakamura and Steinsson Citation2014).

In the first stage of the IV regression, we employ IV_ECO (IV_RL), along with the same set of control variables, firm- and time-fixed effects to estimate the frequency of ECO (RL) practice adoptions. We then use the fitted value of ECOi[08,t] (RLi[08,t]) to explain firm CSR performance in the second-stage regression. The IV regression results, presented in , consistently align with the baseline results. The Kleibergen-Paap rk LM statistics is 161.991 (159.771), indicating that the equation is identified. Moreover, the Cragg-Donald-Wald F statistics is 723.795 (886.758), greater than the critical value of 10, thus rejecting the weak instrument hypothesis (Stock and Yogo Citation2005).

Table 7. Instrumental variable method.

4.2.3 Tobit model method

Given that CSR scores accessed by the RKS fall within a limited range of 0–100, conducting analysis solely with the ordinary least square (OLS) method may cause biased results (Yi et al. Citation2020). To address this concern, the panel Tobit model is adopted to reduce estimation inconsistency caused by the limited dependent variable. reports the results, showing evidence consistent with that presented in the basic regression models. This reaffirms that the basic models are robust and their regression results are reliable.

Table 8. Tobit model method.

4.2.4 Alternative measurements of the independent variables

Following Ding (Citation2014), we recount the frequency of CE practice adoptions from 2008 to t-1 year to build alternative dependent variables (defined as ECOi[08,t-1] and RLi[08,t-1]). This measurement exclusively considers the past and excludes current information, thereby minimizing the two-way causality concerns as the current CSR performance is almost impossible to influence past CE-related decisions. reports the results, showing consistent findings with the results of the basic regression models.

Table 9. Results regressed onto the remeasurements of dependent variables during 2008 to t-1 year.

Following Bergh and Lim (Citation2008), we use another different measurement of independent variables, namely the frequency of ECO and RL practice adoptions over four years prior (defined as ECOi[t-3,t] and RLi[t-3,t]). This measurement captures the impact of recent CE practice adoptions on firm performance.

reports consistent evidence with the baseline results except Columns (2) and (5). The coefficient of Feedback × ECOi[t-3,t] becomes statistically insignificant. One possible explanation is that the latest ECO practices become more complex. There is less room for employees to make new interpretations. The coefficient of Vision × ECOi[t-3,t] is significantly positive. As previously mentioned, the original CE-related vision may make little sense because of the lack of credible profits and technical details. However, its value and viability are recognised as the CE business model develops. The CE vision, therefore, begins to play its role in motivating ECO practices, although the empirical evidence remains inconsistent.

Table 10. Results regressed onto the remeasurements of dependent variables during t-3 to t year.

5. Discussion and conclusion

5.1 Findings and discussions

This study aims to explore the impact of long-term implementation of CE practices on firm CSR performance, as well as the role of sense-giving in the long-run CE change. Using a balanced panel dataset of 132 Chinese manufacturing listed firms during 2013–2018 and a fixed-effect model, the empirical results show that there is a significantly positive relationship between the frequency of adopting ECO (RL) practices and firm CSR performance. Drawing on a sense-giving perspective, the results indicate that three sense-giving activities 0(i.e. goal setting for CE performance, CE education and training, and employee feedback on CE practices) positively moderate the relationship between long-term adoption of RL practices and firm CSR performance, while employee feedback on CE practices positively moderates the ECO-CSR relationship. This research deepens insights into the CSR benefits of long-term adherence to CE and the role of company member cognitions in a shift to CE. Our results emphasise that the transition to a CE is not an overnight process in which companies should pay attention to developing members’ long-term orientation and knowledge of the CE.

Our empirical analysis did not support the assumption that vision communication for CE change can enhance the ECO- and RL-CSR relationships (H2a and H2b). Possible explanations are that the vision might be too grand in scale and become a useless slogan (Carton Citation2017), and it would even be used as an instrument of greenwashing (Zerbino Citation2022). In , 72.3 per cent of firm-year observations communicate their vision, while only 44.9 per cent of the observations set their goals, implying that many firms may still decide not to put CE into action. The results reveal the urgency of translating the vision into practices during a CE change.

There are also no observations of the role of the CE-related goal and education in moderating the ECO-CSR relationship (H3a and H4a). This may be because those ECO practices are mainly carried out by the R&D staff, who often possess more professional knowledge and skills about the CE (Beverland, Micheli, and Farrelly Citation2016). Maitlis and Lawrence (Citation2007) pointed out that sense-giving is triggered by a perception gap and is mainly conducted by expertise to someone with lower knowledge. The findings suggest the heterogeneous effects of sense-giving among different employee groups and advocate to raise awareness of the CE at a firm level.

Employee feedback on CE practices moderates the ECO- and RL-CSR relationships (H5a and H5b), which is consistent with Marinova, Ye, and Singh (Citation2008) who argued that feedback could improve performance because it identified performance gaps and the motivations for employees to regulate their efforts to reduce the gaps. Unlike this, we emphasise its role in identifying interpretation gaps and encouraging both leaders and employees to revise their understanding (Beverland, Micheli, and Farrelly Citation2016).

5.2 Theoretical contributions

This study contributes to the literature in three ways. First, this study moves a step forward in understanding the role of two CE practices in enhancing firm performance, both from a long-term perspective and in terms of CSR performance. This paper measures the long-term implementation of ECO (RL) practices as their adoption frequency over a past period and argues that a higher frequency of ECO (RL) practice adoptions helps to accumulate experience and achieve possible complementarity between different practices, by which firms can achieve a substantial CE change and thus better CSR performance. The empirical evidence shows that the frequency of ECO (RL) practice adoptions significantly improves firm CSR performance, in line with Termeer and Metze (Citation2019), who advocated transiting to a CE through accumulating a series of small CE practices. In addition, existing studies of CE practices have paid less attention to the benefits of CE practices in social and CSR aspects compared to economic and environmental aspects (Zhu, Geng, and Lai Citation2011; Korhonen, Honkasalo, and Seppala Citation2018; Jabbour et al. Citation2020; Khan et al. Citation2021b). In this regard, this study builds a link between CE practices and CSR performance by summarizing the possible benefits of CE practices on its economic, environmental and social aspects.

Second, this research answers the call to develop more studies on the CE drivers by identifying four CE-related sense-giving activities which may moderate CE-CSR relationships. In addition to allocating necessary resources to the CE change, organisational members’ awareness and interest are considered to be crucial to implementing CE in the long run (Ravi and Shankar Citation2005; González-Torre et al. Citation2010); however, few studies have given detailed descriptions and empirical evidence (Khan, Daddi, and Iraldo Citation2020). Drawing on sense-giving, this study proposes that vision communication for the CE change, goal setting for CE performance, CE education and training, and employee feedback on CE practices can strengthen the understanding of and identification with CE among organisational members and thus promote CE practice adoptions. The CE-related goal, education, and feedback positively moderate the RL-CSR relationship while CE-related feedback moderates the ECO-CSR relationship, which echoes the fragmented highlights of the importance of members’ CE-related awareness and interest by Lara and Phillipa (Citation2015), Moktadir et al. (Citation2020), Veleva, Bodkin, and Todorova (Citation2017), Yamoah et al. (Citation2022), etc.

Third, this study adds to the sense-giving literature by re-examining theoretically and empirically the role of sense-giving under the CE background. Recent research calls for more studies on the importance of sense-giving in corporate sustainable strategic change (Bhappu and Schultze Citation2019; Tisch and Galbreath Citation2019), particularly in the CE change (Lazarevic and Valve Citation2017; Murray, Skene, and Haynes Citation2017; Hussain and Malik Citation2020). We respond to the call by detailing sense-giving elements in the above four sense-giving activities. In addition, empirical evidence is also provided, representing a methodological contribution to the sense-giving literature, the majority of which applied a case-study method.

5.3 Managerial implications

Implementing CE practices is crucial for firms to improve CSR performance and achieve sustainable development in today’s increasingly competitive environment. This research offers two main managerial insights into insisting on a CE change. First, we suggest that continuous investments in ECO and RL practices are essential for the successful transition to a CE in manufacturing companies. From an organisational learning view, more frequent adoption of ECO and RL practices helps firms to accumulate experience of CE and to achieve ‘complementary’ effects between varying practices. Managers should maintain a long-term orientation and invest continuously in these two practices. In this process, there is a need to focus on both further improvements to ECO (RL) instruments already in use and the adoption of new instruments that are complementary to those already in use.

Second, our study proposes that CE vision, goal, education and training, and feedback can promote the managers’ and employees’ interpretations of CE and facilitate the CE-CSR relationship. Therefore, we recommend that firms should announce a clear and specific vision regarding a CE strategy to foster employees’ active attitudes towards CE practices by creating relevant values and atmosphere. They should also develop a system of CE target management including some concrete CE tasks and performance metrics, which helps employees understand what they need to do and to what extent they need to implement CE. Moreover, educational and training activities, such as CE expert sharing sessions, volunteer activities, and distribution of handbooks, are suggested to be provided by firms to improve employees’ knowledge of and skills related to CE. Ultimately, we suggest that firms should build feedback channels to involve employees more in jointly interpreting CE practices.

5.4 Limitations and future research

This study has four main limitations that provide directions for future research. First, it is important to acknowledge that this study exclusively examines a sample of 132 Chinese manufacturing listed firms, which may restrict the generalizability of the findings. Therefore, future research could investigate the relationship between CE and CSR in a broader range of companies and industries. Second, the concept of a circular economy encompasses various practices within a firm, such as green procurement, cleaner production, eco-design, waste management, and asset recovery. (Zhu, Geng, and Lai Citation2011; Ghisellini, Cialani, and Ulgiati Citation2016). However, we only pay attention to ECO and RL practices due to data availability. Future research could extend the effects of more CE practices on CSR performance. Third, the four sense-giving activities used in the empirical analysis are directly related to the context of environmental protection and CSR due to data availability, instead of the CE, which may cause some estimation errors. Future research could adopt indicators that are more directly related to the measurement of CE sense-giving activities. Fourth, we focus on four collective sense-giving activities at the firm level. Most scholars have highlighted the importance of leaders as ‘sense-givers’ at an individual level (Foldy, Goldman, and Ospina Citation2008). In this way, this study does not deeply investigate sense-giving tactics by collecting and analysing leaders’ and employees’ narratives related to CE. Future research could use a qualitative design and collect interview data to develop a deeper understanding of sense-giving processes in the context of CE.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their valuable and constructive comments. We are also grateful to Prof. Shujie Yao for his excellent polishing work for the manuscript, and to Dr. Lei An, Bo Wang, and Maochuan Wang for their valuable suggestions in the empirical analysis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

2 Accelerating the Circular Economy | Dell Technologies Anguilla

References

- Accenture. 2014. Circular Advantage: Innovative Business Models and Technologies to Create Value in a Word Without Limits to Growth. Dublin: Accenture-circular-advantage-innovative-business-models-technologies-value-growth.pdf.

- Agyabeng-Mensah, Y., L. Tang, E. Afum, C. Baah, and E. Dacosta. 2021. “Organisational Identity and Circular Economy: Are Inter and Intra Organisational Learning, Lean Management and Zero Waste Practices Worth Pursuing?” Sustainable Production and Consumption 28: 648–662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.06.018.

- Al-Sheyadi, A., L. Muyldermans, and K. Kauppi. 2019. “The Complementarity of Green Supply Chain Management Practices and the Impact on Environmental Performance.” Journal of Environmental Management 242: 186–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.04.078.

- Aldrighetti, R., D. Battini, A. Das, and M. Simonetto. 2022. “The Performance Impact of Industry 4.0 Technologies on Closed-Loop Supply Chains: Insights from An Italy Based Survey.” International Journal of Production Research, ahead of print, https://doi.org/10.1080/00207543.2022.2075291.

- Antonioli, D., C. Ghisetti, M. Mazzanti, and F. Nicolli. 2022. “Sustainable Production: The Economic Returns of Circular Economy Practices.” Business Strategy and the Environment 31 (5): 2603–2617. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3046.

- Balogun, J., J. Bartunek, and B. Do. 2015. “Senior Managers’ Sensemaking and Responses to Strategic Change.” Organization Science 26 (4): 960–979. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2015.0985.

- Beji, R., O. Yousfi, N. Loukil, and A. Omri. 2021. “Board Diversity and Corporate Social Responsibility: Empirical Evidence from France.” Journal of Business Ethics 173 (1): 133–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04522-4.

- Benbenisty, Y., and G. Luria. 2021. “A Time to Act and A Time for Restraint: Everyday Sensegiving in the Context of Paradox’.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 42 (2): 1005–1022. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2537.

- Bergh, D. D., and E. N. K. Lim. 2008. “Learning How to Restructure: Absorptive Capacity and Improvisational Views of Restructuring Actions and Performance.” Strategic Management Journal 29 (6): 593–616. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.676.

- Beverland, M. B., P. Micheli, and F. J. Farrelly. 2016. “Resourceful Sensemaking: Overcoming Barriers Between Marketing and Design in NPD.” Journal of Product Innovation Management 33 (5): 628–648. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMBPP.2015.16308.

- Bhappu, A. D., and U. Schultze. 2019. “The Sharing Economy Ideal Implementing an Organisation-sponsored Sharing Platform as A CSR program.” Internet Research 29 (5): 1109–1123. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-02-2018-0078.

- Borusyak, K., P. Hull, and X. Jaravel. 2022. “Quasi-Experimental Shift-Share Research Designs.” The Review of Economic Studies 89 (1): 181–213. https://doi.org/10.1093/restud/rdab030.

- Boscari, S., P. Danese, and P. Romano. 2016. “Implementation of Lean Production in Multinational Corporations: A Case Study of the Transfer Process from Headquarters to Subsidiaries.” International Journal of Production Economics 176: 53–68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2016.03.013.

- Carton, A. M. 2017. ““I’m Not Mopping the Floors, I’m Putting a Man on the Moon”: How NASA Leaders Enhanced the Meaningfulness of Work by Changing the Meaning of Work.” Administrative Science Quarterly 63 (2): 323–369. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839217713748.

- Centobelli, P., R. Cerchione, E. Esposito, R. Passaro, and K. Shashi. 2021. “Determinants of the Transition Towards Circular Economy in SMEs: A Sustainable Supply Chain Management Perspective.” International Journal of Production Economics 242 (1-2): 108297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2021.108297.

- Chen, L. J., M. Q. Jiang, T. Y. Li, F. Jia, and M. K. Lim. 2023. “Supply Chain Learning And Performance: A Meta-Analysis.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management, ahead of print, https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-05-2022-0289.

- Chen, L. J., T. Y. Li, F. Jia, and T. Schoenherr. 2022. “The Impact of Governmental COVID-19 Measures on Manufacturers’ Stock Market Valuations: The Role of Labour Intensity and Operational Slack.” Journal of Operations Management, ahead of print, https://doi.org/10.1002/joom.1207.

- Cheng, B. T., I. Loannou, and G. Serafeim. 2014. “Corporate Social Responsibility and Access to Finance.” Strategic Management Journal 35 (1): 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2131.

- Choi, D., and T. Hwang. 2015. “The Impact of Green Supply Chain Management Practices on Firm Performance: The Role of Collaborative Capability’.” Operations Management Research 8 (3-4): 69–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12063-015-0100-x.

- Daily, B. F., J. W. Bishop, and J. A. Massoud. 2012. “The Role of Training and Empowerment in Environmental Performance: A Study of the Mexican Maquiladora Industry.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 32 (5): 631–647. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443571211226524.

- De Jesus, A., and S. Mendonça. 2018. “Lost in Transition? Drivers and Barriers in the Eco-Innovation Road to the Circular Economy.” Ecological Economics 145: 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.08.001.

- De los Rios, I. C., and F. J. S. Charnley. 2017. “Skills and Capabilities for A Sustainable and Circular Economy: The Changing Role of Design.” Journal of Cleaner Production 160: 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.10.130.

- Demirel, P., and G. O. Danisman. 2019. “Eco-Innovation and Firm Growth in the Circular Economy: Evidence from European Small- and Medium-Sized Enterprises.” Business Strategy and the Environment 28 (8): 1608–1618. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2336.

- Dey, P. K., C. Malesios, D. De, P. Budhwar, S. Chowdhury, and W. Cheffi. 2020. “Circular Economy to Enhance Sustainability of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises.” Business Strategy and the Environment 29 (6): 2145–2169. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2492.

- Ding, D. X. 2014. “The Effect of Experience, Ownership and Focus on Productive Efficiency: A Longitudinal Study of U.S. Hospitals.” Journal of Operations Management 32 (1-2): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jom.2013.10.002.

- Firoozi, M., and L. Keddie. 2022. “Geographical Diversity Among Directors and Corporate Social Responsibility.” British Journal of Management 33 (2): 828–863. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12481.

- Fiss, P. C., and E. J. Zajac. 2006. “The Symbolic Management of Strategic Change: Sensegiving via Framing and Decoupling’.” Academy of Management Journal 49 (6): 1173–1193. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.23478255.

- Foldy, E. G., L. Goldman, and S. Ospina. 2008. “Sensegiving and the Role of Cognitive Shifts in the Work of Leadership.” The Leadership Quarterly 19 (5): 514–529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2008.07.004.

- Fuente, M., L. Ros, and M. Cardós. 2008. “Integrating Forward and Reverse Supply Chains: Application to A Metal-Mechanic Company.” International Journal of Production Economics 111 (2): 782–792. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpe.2007.03.019.

- Gao, G. Y., and Y. G. Pan. 2010. “The Pace of MNEs’ Sequential Entries: Cumulative Entry Experience and the Dynamic Process.” Journal of International Business Studies 41 (9): 1572–1580. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2010.15.

- Geng, Y., F. Jia, J. Sarkis, and B. Xue. 2011. “Towards A National Circular Economy Indicator System in China: An Evaluation and Critical Analysis.” Journal of Cleaner Production 23 (1): 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2011.07.005.

- Geng, Y., J. Sarkis, and S. Ulgiati. 2016. “Sustainability, Well-Being, and the Circular Economy in China and Worldwide.” Science 6278 (Supplement): 73–76.

- Ghisellini, P., C. Cialani, and S. Ulgiati. 2016. “A Review on Circular Economy: The Expected Transition to A Balanced Interplay of Environmental and Economic Systems’.” Journal of Cleaner Production 114: 11–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.09.007.

- Gholami, R., A. B. Sulaiman, T. Ramayah, and A. Molla. 2013. “Senior Managers’ Perception on Green Information Systems (IS) Adoption and Environmental Performance: Results from A Field Survey.” Information & Management 50 (7): 431–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2013.01.004.

- Gioia, D. A., and K. Chittipeddi. 1991. “Sensemaking and Sensegiving in Strategic Change Initiation.” Strategic Management Journal 12 (6): 433–448. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250120604.

- Gioia, D. A., and J. B. Thomas. 1996. “Identity, Image, and Issue Interpretation: Sensemaking During Strategic Change in Academia.” Administrative Science Quarterly 41 (3): 370–403. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393936.

- Glass, C., A. Cook, and A. R. Ingersoll. 2016. “Do Women Leaders Promote Sustainability? Analyzing the Effect of Corporate Governance Composition on Environmental Performance.” Business Strategy and the Environment 25 (7): 495–511. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.1879.

- Gochmann, V., D. Stam, and M. Shemla. 2022. “The Boundaries of Vision Communication—The Effects of Vision-Task Goal-Alignment on Leaders' Effectiveness.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 52 (5): 263–276. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12855.

- González-Torre, P., M. Álvarez, J. Sarkis, and B. Adenso-Díaz. 2010. “Barriers to the Implementation of Environmentally Oriented Reverse Logistics: Evidence from the Automotive Industry Sector.” British Journal of Management 21 (4): 889–904. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8551.2009.00655.x.

- Gorli, M., D. Nicolini, and G. Scaratti. 2015. “Reflexivity in Practice: Tools and Conditions for Developing Organizational Authorship.” Human Relations 68 (8): 1347–1375. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726714556156.

- Harjoto, M., I. Laksmana, and R. Lee. 2015. “Board Diversity and Corporate Social Responsibility.” Journal of Business Ethics 132 (4): 641–660. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2343-0.

- Heckman, J. J. 1979. “Sample Selection Bias as a Specification Error.” Econometrica 47 (1): 153–161. https://doi.org/10.2307/1912352.

- Hill, R. C., and M. Levenhagen. 1995. “Metaphors and Mental Models: Sensemaking and Sensegiving in Innovative and Entrepreneurial Activities.” Journal of Management 21 (6): 1057–1074. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639502100603.

- Hussain, M., and M. Malik. 2020. “Organizational Enablers For Circular Economy in the Context of Sustainable Supply Chain Management.” Journal of Cleaner Production 256: 120375. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120375.

- Inkpen, A. C. 2008. “Knowledge Transfer and International Joint Ventures: The Case of NUMMI and General Motors.” Strategic Management Journal 29 (4): 447–453. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.663.

- Jabbour, C. J. C., F. C. A. Santos, and M. S. Nagano. 2010. “Contributions of HRM Throughout the Stages of Environmental Management: Methodological Triangulation Applied to Companies in Brazil.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 21 (7): 1049–1089. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585191003783512.

- Jabbour, C. J. C., J. Sarkis, A. B. L. de Sousa Jabbour, D. W. S. Renwick, S. K. Singh, O. Grebinevych, I. Kruglianskas, and M. G. Filho. 2019. “Who is in Charge? A Review and A Research Agenda on the ‘Human Side’ of the Circular Economy.” Journal of Cleaner Production 222: 793–801. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.03.038.

- Jabbour, C. J. C., S. Seuring, A. B. L. de Sousa Jabbour, D. Jugend, P. D. C. Fiorini, H. Latan, and W. C. Izappi. 2020. “Stakeholders, Innovative Business Models for the Circular Economy and Sustainable Performance of Firms in an Emerging Economy Facing Institutional Voids.” Journal of Environmental Management 264: 110416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2020.110416.

- Jia, F., D. Li, G. Q. Liu, H. Sun, and J. E. Hernandez. 2020a. “Achieving Loyalty for Sharing Economy Platforms: An Expectation–Confirmation Perspective.” International Journal of Operations & Production Management 40 (7-8): 1067–1094. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-06-2019-0450.

- Jia, F., S. Y. Yin, L. J. Chen, and X. W. Chen. 2020b. “The Circular Economy in the Textile and Apparel Industry: A Systematic Literature Review.” Journal of Cleaner Production 259: 120728. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120728.

- Jiang, H. Y., Y. Y. Hu, K. Su, and Y. H. Zhu. 2021. “Do Government say-on-pay Policies Distort Managers’ Engagement in Corporate Social Responsibility? Quasi-Experimental Evidence from China.” Journal of Contemporary Accounting & Economics 17 (2): 100259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcae.2021.100259.

- Johnson, R. A., and D. W. Greening. 1999. “The Effects of Corporate Governance and Institutional Ownership Types on Corporate Social Performance.” Academy of Management Journal 42 (5): 564–576. https://doi.org/10.2307/256977.

- Karuppiah, K., B. Sankaranarayanan, S. M. Ali, C. J. C. Jabbour, and R. K. A. Bhalaji. 2021. “Inhibitors to Circular Economy Practices in the Leather Industry Using An Integrated Approach: Implications for Sustainable Development Goals in Emerging Economies.” Sustainable Production and Consumption 27: 1554–1568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.03.015.

- Khan, O., T. Daddi, and F. Iraldo. 2020. “Microfoundations of Dynamic Capabilities: Insights from Circular Economy Business Cases.” Business Strategy and the Environment 29 (3): 1479–1493. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2447.

- Khan, S. A. R., A. Razzaq, Z. Yu, and S. Miller. 2021a. “Industry 4.0 and Circular Economy Practices: A New Era Business Strategies for Environmental Sustainability.” Business Strategy and the Environment 30 (8): 4001–4014. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2853.

- Khan, S. A. R., Z. Yu, S. Sarwat, D. I. Godil, S. Amin, and S. Shujaat. 2021b. “The Role of Block Chain Technology in Circular Economy Practices to Improve Organisational Performance.” International Journal of Logistics Research and Applications 25 (4-5): 605–622. https://doi.org/10.1080/13675567.2021.1872512.

- Kirchherr, J., L. Piscicelli, R. Bour, E. Kostense-Smit, J. Muller, A. Huibrechtse-Truijens, and M. P. Hekkert. 2018. “Barriers to the Circular Economy: Evidence from the European Union (EU).” Ecological Economics 150: 264–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2018.04.028.

- Klos, C., and P. Spieth. 2021. “Ready, Steady, Digital?! How Foresight Activities Do (Not) Affect Individual Technological Frames for Managerial Sensemaking.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 163: 120428. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120428.

- Korhonen, J., A. Honkasalo, and J. Seppala. 2018. “Circular Economy: The Concept and Its Limitations.” Ecological Economics 143: 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2017.06.041.

- Kostova, T., and K. Roth. 2002. “Adoption of An Organizational Practice by Subsidiaries of Multinational Corporations: Institutional and Relational Effects.” Academy of Management Journal 45 (1): 215–233. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069293.

- Kraft, A., J. L. Sparr, and C. Peus. 2018. “Giving and Making Sense About Change: The Back and Forth Between Leaders and Employees’.” Journal of Business and Psychology 33 (1): 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-016-9474-5.

- Kumar, M., R. D. Raut, S. Jagtap, and V. K. Choubey. 2022. “Circular Economy Adoption Challenges in the Food Supply Chain for Sustainable Development.” Business Strategy and the Environment. ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.3191

- Kuo, L. P., C. C. Yeh, and H. C. Yu. 2011. “Disclosure of Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management: Evidence from China.” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 19 (5): 273–287. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.274.

- Langeler, G. E. 1992. “The Vision Trap.” Harvard Business Review 70 (2): 46–54.