ABSTRACT

The relationships between citizens and their states are undergoing significant stresses across advanced liberal democracies. In Britain, this disconnect is particularly evident amongst young citizens. This article considers whether different electoral engineering methods – designed either to cajole or compel youth to vote – might arrest the decline in their political engagement. Data collected in 2011 from a national survey of 1025 British 18-year-olds and from focus groups involving 86 young people reveal that many young people claim that they would be more likely to vote in future elections if such electoral reforms were implemented. However, it is questionable whether or not such increased electoral participation would mean that they would feel truly connected to the democratic process. In particular, forcing young people to vote through the introduction of compulsory voting may actually serve to reinforce deepening resentments, rather than engage them in a positive manner.

Introduction

In recent years, young people's futures have become increasingly susceptible to, and shaped by, the spread of neoliberalism and it's actualisation in the economic and social policies pursued by governments across many advanced liberal democracies (Furlong and Cartmel Citation2012). In particular, austerity programmes introduced as a response to the developing global economic crisis since 2008 have resulted in an intensification of the risks and uncertainties faced by the current youth generation (Sloam Citation2014). At the same time – and in part as a consequence of these developments – there has occurred a deepening disconnect between young citizens and formal politics in many advanced democratic states. While we have seen a rise in the level of their involvement in social activism (Pattie, Seyd, and Whiteley Citation2004), this has contrasted with a steady decline in youth electoral participation (Wattenberg Citation2008). In Britain, this divide between young people and mainstream democratic politics is particularly visible, and their lack of presence at elections often leads commentators and academics to disregard young people as apathetic and uninterested in democratic politics – or even as anti-political (see, for instance: Stoker Citation2006; Hay Citation2007; Farthing Citation2010; Phelps Citation2012).

This paper seeks to explore the factors underlying the ongoing rift between young citizens and the British state, and to investigate whether and how this generation might be re-connected to the democratic process. It begins by examining the debate concerning young people's disengagement from formal democratic politics; in particular, it considers whether or not this is symptomatic of entrenched apathy, or instead whether it is indicative of a youth generation that is re-directing its attention towards alternative forms of political practice. Secondly, the paper examines the consequences of young people's electoral abstention if left un-checked, especially in terms of its impact on the deepening of existing generational social and economic inequalities. The paper then considers the prospects open for governments to intervene in order to stimulate meaningful youth electoral participation, which fosters enhanced commitment to the democratic process. This assesses young people's views on a range of electoral administrative reforms, including extending the voting period and increasing the range of voting methods beyond physical attendance at the ballot booth. It has been contended that compulsory voting offers a practical way forward to reduce electoral inequalities, by mobilising increased turnout of perennial abstainers such as the young, the least politically interested and the socio-economically disadvantaged (Lijphart Citation1997; Singh Citation2014). The paper then analyses young people's views on proposals intended to compel them to vote.

Explaining youth (dis)engagement – apathy or alternative politics?

That the electoral turnout rate of young citizens in Britain is lower than for their older contemporaries is not in question. Estimates vary on the turnout rate for 18 to 24-year-olds at the 2015 General Election, ranging from 58% (Sky News Citation2015) to 43% (Ipsos MORI Citation2015). Nonetheless, youth electoral participation remained well below rates recorded during the 1980s and 1990s (Henn and Foard Citation2014); it was also significantly less than for their older contemporaries, with for instance 76% of those aged 65 and over voting at the 2015 contest – a generational electoral gap of 33% (Ipsos MORI Citation2015). However, it is not only their rate of electoral participation that distinguishes young people from other citizens. There is a significant body of evidence suggesting that young people in the UK and in other advanced liberal democracies are withdrawing from other formal and institutionalised methods of political participation, defined by Hooghe and Marien as referring to ‘all participation acts that are, directly, or indirectly, linked to the functioning of political institutions’ (Citation2014, 538). But what is behind this apparent young citizen–state disconnect? Phelps (Citation2012) has articulated two competing schools of thought which seek to explain young people's disengagement from formal institutionalised politics, and their turn toward alternative political repertoires. The first of these is a traditional political science understanding, which contends that the generational participatory divide is a consequence of life-cycle factors, in which young citizens are confronted with key start-up problems that inhibit their engagement with formal democratic politics (Nie, Verba, and Kim Citation1974; Parry, Moyser, and Day Citation1992). Thus, this approach suggests that various life-style and contextual factors including increasing levels of geographic mobility and a corresponding lack of connection and engagement within neighbourhoods, as well as extended and complex transitions into adulthood, combine to problematise their life-courses, leaving relatively little time and space to prioritise conventional politics including voting (Phelps Citation2012). However, as they enter later phases of adulthood, it is claimed that they acquire the resources and space to engage with the formal political process, including voting in elections (Norris Citation2003).

In contrast, an alternative position contends that this predominant political science thesis is too limiting in its methodology, relying on conventional (typically quantitative) indicators in order to define engagement with politics and political participation, such as electoral activity and support for, and membership of, mainstream political parties (Henn, Weinstein, and Wring Citation2002; Marsh, O'Toole, and Jones Citation2007). This ‘anti-apathy’ approach (Phelps Citation2012) claims that such traditional understandings fail to fully appreciate the diverse range of non-institutionalised political actions that young citizens engage in. These include demonstrations (Pattie, Seyd, and Whiteley Citation2004), political consumerism (Micheletti and Stolle Citation2008) and Internet activism (Oser, Hooghe, and Marien Citation2013). Unlike the life-cycle approach which contends that low rates of participation in formal politics will correct over time and follow a positive and upward trajectory, the anti-apathy approach considers that young people are actively by-passing such conventional modes and channels of participation. Instead, they are more inclined to embrace alternative forms of non-institutionalised and extra-parliamentary modes of political action which more closely accord with their individuated life-styles and aspirations and which are more self-actualising; these are considered to be less hierarchical, more expressive, more participative, more flexible, more meaningful and ultimately more effective (Giddens Citation1991; Beck Citation1992; Henn, Weinstein, and Wring Citation2002; Farthing Citation2010; Furlong and Cartmel Citation2012; Tormey Citation2015). Furthermore, the ‘anti-apathy’ approach challenges the notion that young citizens are inherently uninterested in politics. Instead, it is claimed that there is significant evidence to indicate that whilst British youth hold a deep aversion to the forms of politics as practised by professional politicians at Westminster, they are interested in ‘politics' in its broadest sense (Holmes and Manning Citation2013; Henn and Foard Citation2014).

Generational electoral inequality and the deepening of socio-economic inequalities

According to Dalton (Citation2008), the very fact that young citizens are engaging in alternative styles of politics and civic action suggests that the continued decline witnessed in their rates of participation in formal institutionalised politics such as voting does not by itself present a problem for contemporary advanced liberal democracies. However, this is a contested view. Firstly, it is arguable that active participation of young people in political and social life is very important for this generation and for society more broadly, as effective governance requires a strong political culture in which people feel connected with, and supportive of, the state (Birch, Gottfried, and Lodge Citation2013). As Whiteley contends, ‘[i]f few people participate in elections, then the state will lose its legitimacy and it will not be able to persuade its citizens to cooperate in the tasks of governing' (Citation2012, 9).

A further challenge to Dalton's position is offered by Wattenberg (Citation2008) who claims that any generational disparity in electoral participation rates tends to result in the policy concerns of young people being given relatively little priority by the political classes. Thus, when elected to office, politicians in government will tend to pursue policies that favour older and other more voting-inclined groups at the expense of younger and more non-voting-inclined groups (Berry Citation2012). Evidence suggests that this process has recently been present in Britain, and has furthered the disconnect between young citizens and the state. For instance, Furlong and Cartmel (Citation2012) claim that at the 2010 UK General Election, the debate concerning university tuition fees tended to centre on the implications for older tax-paying parents and guardians rather than viewing the issue from the position of the (prospective) students themselves. The developing global economic crisis and associated Government austerity policies have also placed a disproportionate burden on the young (Sloam Citation2014). Reflecting this, a recent Institute for Public Policy Research report has highlighted the differential impact of the UK Government's 2010 Comprehensive Spending Review on different social groups. It concluded that the 16–24-year-old group has suffered more than any other group from the cuts (Birch, Gottfried, and Lodge Citation2013). This has serious implications for contributing to the deepening of existing generational social and economic inequalities.

These recent and perceived failings of professional politicians to champion the policy concerns of today's young people have left this generation feeling relatively ignored and marginalised (Mycock and Tonge Citation2012). This state of affairs helps to account for young people's continued withdrawal from the electoral process.

UK Government responses to the citizen–state divide

In the formal political realm, national politicians have observed this persisting youth electoral abstention with increasing concern. For instance, a recent UK House of Commons report has concluded that, ‘[D]emocracy is working less well than it used to and we need to move swiftly to pre-empt a crisis. The scale of the response must be equal to the task’ (House of Commons Political and Constitutional Reform Committee Citation2014, 6). This is despite the endeavours of recent governments who have sought to stem the tide of voter abstention and diminishing political engagement by the introduction of initiatives designed to increase political literacy and to make the process of voting more accessible.

Such programmes and schemes are broadly ‘procedural–technical' in nature, rather than involving the introduction of far-reaching political reforms designed to create routes for young people to more readily access the centres of power as advocated by Stoker (Citation2006) and Henn and Foard (Citation2012a). Thus, the introduction of statutory citizenship classes in schools in England in 2002 was in large part prompted by the concerns of the national Government at that time that young people lacked any inclination to participate in the political process – as well as the requisite political literacy skills to do so effectively (Tonge, Mycock, and Jeffery Citation2012). In addition, there have been a number of initiatives considered and others implemented which have been designed to modernise electoral administration. The Representation of the People Act 2000 approved the use of experiments in local elections to encourage people to register to vote, to remove perceived disincentives to vote and to make voting easier. As a consequence, pilot schemes of innovative electoral procedures were conducted across many local authorities between 2000 and 2007. These included remote electronic voting (for instance, by Internet and text messaging), voting during different hours, on different days or over a number of days, and all-postal voting. Evidence suggests that the impact and veracity of these initiatives have been mixed (Boon, Curtice, and Martin Citation2007), although there have recently been calls by the UK House of Commons Political and Constitutional Reform Committee (Citation2014) and the Electoral Commission (Mason Citation2014) to advance investigations into such electoral modernisation methods. Wattenberg contends that while not a cure-all, such reforms might contribute to lessening ongoing generational disparities in electoral participation (Citation2008).

In this paper, data will be analysed to examine the extent to which governmental interventions in the form of such administrative electoral reforms might persuade young people to engage more fully in the electoral process, and by doing so, serve to reduce the young citizen–state disconnect.

Might compulsory voting resolve the young citizen–state disconnect?

One method recently considered by which government might intervene to reduce young people's disengagement from electoral politics is to introduce a system of compulsory voting for first-time voters. In this scenario, young people who have only recently reached the minimum voting age and who have not formerly had the opportunity to vote would be obliged to turn out on their first occasion to do so – regardless of the electoral level (national, local, European or other). As a one-off compulsory system, it is considered that this would ‘kick-start a life-long habit of voting' (Birch, Gottfried, and Lodge Citation2013, 21). However, there are significant democratic values and civil rights dimensions to this issue, and it has been the subject of a recent ongoing and unresolved debate (see for instance Saunders Citation2010; Fischer Citation2011).

A key argument in support of compulsory voting for young people is that it will significantly increase this generation's attendance at the ballot booths by up to 30% (Hill Citation2011). Furthermore, if young people are compelled to vote, then this might facilitate access to their dormant democratic spirit, and stimulate a habit for positive democratic engagement in the future (Franklin Citation2004). Secondly, evidence suggests that compulsory voting may reduce generational disparities in electoral participation rates (Singh Citation2014); in particular, it helps to ensure that socio-economically disadvantaged groups are neither under-represented at the ballot booth nor under-estimated in the minds of politicians and policy-makers (Hooghe and Pelleriaux Citation1998). It is therefore reasoned that, in delivering higher youth turnout rates, compulsory voting might oblige professional politicians to treat young people and their policy concerns on a par with those of their older contemporaries (Lijphart Citation1997; Birch, Gottfried, and Lodge Citation2013). In essence, by helping to eliminate the generational electoral divide, it is argued that this would have the effect of reducing generational social and economic policy inequalities. This might contribute to the creation of a virtuous circle, in that young people begin to recognise the latent power of their vote and of their influence over the political class – and this might help to shape an enhanced positive predisposition to electoral participation. However, this is a contested position. According to Lever:

Compulsory voting is clearly no guarantee of egalitarian social policies, and the Australian case – where compulsory voting is extremely popular and is long established – shows that increasing turnout does not force parties to compete for the votes of the poor, the weak and the marginalised. (Citation2008, 63)

A major drawback of such a compulsory voting scheme for young people is that it singles them out as ‘different’ from the rest of the adult population, helping to reinforce the stereotype of this current youth generation as distinctly apathetic. The implication being that it is the behaviour of young people that needs changing, rather than a reform of the political process and of democratic institutions including political parties to make the latter more accessible and meaningful for today's youth generation.

Furthermore, it might be argued that compelling any young person to vote who has only limited interest in mainstream electoral politics or who feels no affinity with the parties on offer has serious negative implications for the health of our democratic system; by forcing them to vote, they may develop an attitude of entrenched disdain for the parties, or indeed become particularly susceptible to parties with antidemocratic tendencies – especially those of the far-right (Jensen and Spoon Citation2011). However, offering the option to vote for ‘None of the above’ on the ballot paper may help mitigate against this latter point (House of Commons Political and Constitutional Reform Committee Citation2014).

Despite such conjecture, there remain unanswered the questions, (i) would compulsory voting resolve the young citizen–state disconnect, and (ii) would it result in enhanced high-quality political engagement? This conundrum is captured in the recent deliberations of the UK Electoral Commission (Citation2006, 6), which concluded that:

It is clear from the available evidence that compulsory voting both increases aggregate turnout and reduces the variation in turnout rates among different groups. Less clear is the effect compulsory voting has on political engagement more generally.

Research design

In this paper, we investigate why it is that so many eligible young people abstain from voting in elections. Is this a consequence of various life-cycle start-up factors which inhibit their participation and which induce political apathy, but which might be over-come with time as they enter a later life phase? Or is it instead, because they feel alienated from the political process, which carries the possibility that their disconnection from electoral politics might endure into advanced life stages? To address these matters, we consider the following issues from the perspectives of British youth, based on analyses of a qualitative data set:

levels of interest in, and understanding of, politics and elections;

attitudes towards the political process and democratic institutions in Britain;

degree of faith in political parties and politicians.

We then use a related quantitative data set to consider what scope there might be for government to re-engage young citizens with the formal democratic process in Britain, and to encourage their turnout at elections. We do this by assessing their responses to a range of electoral administration measures intended to persuade them to vote. In particular, we aim to examine how young people's responses to such proposals are linked with, and shaped by, their past and likely future voting intentions. Firstly, we consider a range of six measures designed to make voting more accessible to young people. These include whether they would be more likely or less likely to vote in the future if they were able to vote:

in a public place such as a supermarket;

over more than one day (including weekends);

by post;

by phone (including by text message or smart phone App);

via the Internet or digital television;

or if polling stations were open for 24 hours.

In formal terms, our hypotheses are:

H1: The introduction of new electoral methods designed to make voting more accessible will be received more positively by young people who voted at the previous General Election than by their contemporaries who did not vote;

H2: The introduction of new electoral methods designed to make voting more accessible will be received more positively by young people who intend to vote in a future General Election than by their contemporaries who expect to abstain from voting.

It has been contended that young people's lives, perspectives and behaviour are increasingly complex and individualised (Giddens Citation1991). Research suggests that they are nonetheless also susceptible to, and their perspectives and behaviour shaped by, a complex array of factors. In particular, there is a significant body of research indicating that key social predictors have an enduring and critical bearing on political participation and engagement in Britain, and across the age ranges. Thus, age-completed education (Whiteley Citation2012) and educational qualifications (Tenn Citation2007), gender (Furlong and Cartmel Citation2012), social class (Pattie, Seyd, and Whiteley Citation2004; Holmes and Manning Citation2013) and ethnicity (Heath et al. Citation2011) are all considered to impact on voting. However, there is relatively little large-scale empirical research focusing on the diversity of young people's political perspectives and behaviour (for exceptions, see Tonge, Mycock, and Jeffery Citation2012; Henn and Foard Citation2014). Furthermore, there is a noticeable absence of research into the effect of these socio-demographic variables on young people's attitudes to such government-initiated electoral reforms as outlined above. In this paper we intend to explore these relationships which, in formal terms, are expressed in the hypothesis below:

H3: Young people's views concerning the introduction of new electoral methods designed to persuade people to vote will vary according to their socio-demographic backgrounds.

We also consider young people's reaction to a proposal for the introduction of mandatory voting intended to compel them to participate in the electoral process. Our hypotheses are:

H4: The introduction of compulsory voting will be received more positively by young people who voted at the previous General Election than by their contemporaries who did not vote;

H5: The introduction of compulsory voting will be received more positively by young people who intend to vote in a future General Election than by their contemporaries who expect to abstain from voting;

H6: Young people's views concerning the introduction of compulsory voting will vary according to their socio-demographic backgrounds.

In order to examine these questions and hypotheses, we used qualitative and quantitative data from a study conducted by one of the authors in 2011 (Henn and Foard Citation2012b). Two unique data sets were created, the first of these was derived from a national, representative online survey of 1025 young people aged 18 at the time of the 2010 UK General Election. The survey was conducted during April and May 2011, one year after the election; this was important because we wanted to assess the views and reactions of this particular age group after they had been granted their first opportunity as newly enfranchised citizens to gain experience of life under a new government – regardless of whether or not they had opted to vote in the election.

We also convened 14 online focus groups with a total of 86 participants in November 2011, with participants deliberately selected as young people who had not voted at the 2010 General Election. The intention was to explore the ways in which non-voters, so often characterised as politically apathetic, conceptualise politics. The focus groups provided the opportunity to examine the ways in which discourses of politics are constructed when young people express and shape their views among peers. The focus groups were subdivided by ‘type’ and separate groups were held for young white people and those from Black and Minority Ethnic (BME) groups, and likewise, separate male and female groups, and also groups comprising either those who had progressed to higher education or those who had opted not to do so. Distinct focus groups were also held with young people from predominantly professional and middle class (ABC1) households, and those from more broadly working class (C2DE) households. It is important to note that in the results section that follows, focus group quotes used are from the original text responses typed by participants during the online focus groups, and have not been altered to improve spelling or grammar. The exception to this is where we use [ ] as insertions which are designed to help clarify the context in which the response was given. Additionally (and unless otherwise indicated), when reviewing verbatim observations from the focus groups, only typical quotes are used to provide a broadly valid illustrative overview of the opinions of the young people participating.

Results

The data from the online survey and online focus groups present important insights into why young people tend to avoid formal democratic politics and why so many continue to abstain from voting in elections. Equally, the data reveal possibilities and options for government to facilitate the process of re-connecting today's youth generation with the formal democratic politics and institutions.

Youth engagement with ‘politics'

In the focus groups, participants (all of whom had opted not to vote at the previous year's general election) were asked, ‘If I say politics, what do you say?'. Responses indicate that they tend to define ‘politics' in its most formal sense – as the politics of Westminster, centred on elections and the main political parties – and they find this form of politics considerably remote, deeply unappealing and resting on deception. A small selection of typical responses offered by participants includes:

i feel its boring as it doesnt feel like it relates to me in any way shape or form

a way of makeing you feel you have a say when you don't

I always try and avoid politics because they all get me angry

they break promises, they want our votes then cast us off like we didnt care in the first place. i think if i ever voted i would feel used for the vote

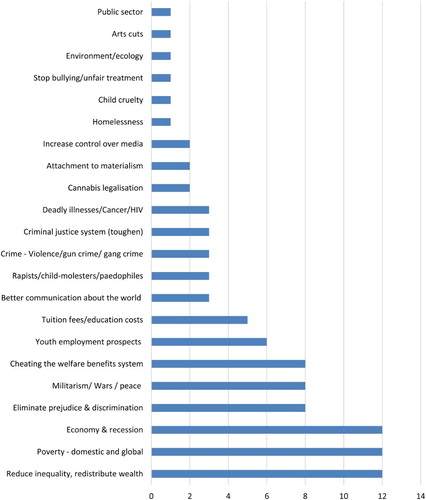

Despite this characterisation of politics, the data reveal that young people do study the world around them – and they often feel strongly about contemporary issues, even if they do not necessarily consider those issues to be overtly ‘political' in nature. This fits with the anti-apathy approach outlined by Phelps (Citation2012) suggesting that young people are interested in matters that are of civic and political consequence. Focus group participants were asked, ‘If you could change one thing about the world, what would it be, and why?'. This question was designed to enable us to gain a sense of which issues and matters were of primary concern to them, as well as their reasons for emphasising such concerns. categorises these open responses.Footnote1 As expected, the reactions to the question were varied, although participants demonstrated a particularly solidaristic outlook and a broad commitment to social justice. Thus, a significant number of respondents prioritised the tackling of domestic and global inequalities and support for a generalised redistribution of wealth. They also advocated the introduction of measures designed to reduce poverty (‘lessen the gap between the richest and poorest people'; ‘I would like equality throughout the world and would like to end poverty'). Furthermore, the emphasis on collective social justice was also revealed through the desire to eliminate all forms of prejudice and discrimination: stop descrimination and rascism as everyone is the same; put a stop to bullying and unfair treatment.

The focus groups also revealed clear signs of an underlying youth anxiety about their immediate educational and employment prospects:

Higher education and in particular, employment prospects at the end of it

the cost of education , i think education should be free for everyone no matter were you frm

employmnt for the youths really s an issue for me

Prospects for achieving political influence

Although they appear to be interested in politics, young people seem to lack confidence in the political system, or what others have referred to as ‘external efficacy' (Westholme and Niemi Citation1986). Data from the focus groups reveal that they feel unable to translate this interest into participation in the formal political system – which they consider to be unresponsive to the actions of individual and collective groups of citizens. They also feel that there are relatively few meaningful opportunities available for themselves or other young people to access the centres and levers of political power. The data indicate that young people feel a sense of fatalism and inevitability with respect to this lack of perceived external efficacy, especially in relation to individual political action and participation:

the indivdual cant change it

plenty of people have voiced thier opinion about all the different cuts some through protests … it still hasnt changed circumstances so little old me would be useless

[ … ] one cannot do it themselves, we need thousands upon thousands to make the slightest difference

Of course, we recognise that since the focus group participants were intentionally selected as non-voters, we might expect them to hold such pessimistic views on this matter; however, given that a considerable majority of young people abstained at the 2010 General Election, these results provide important insights into why they feel demotivated to vote. Interestingly, there was a mixed response when they were asked to comment on collective political action, including protests. On the one hand, a considerable minority of young people highlighted the potential efficacy of such methods for advancing causes and facilitating positive political change – especially in contrast to the perceived value of individual political action:

i think there is strength in numbers not individuals acting alone

i believe if large enough numbers it could [be effective]

if a big enough group of people stand up they might listen!

However, the predominant view emerging from the focus groups was that even such collective actions had only limited potential for effecting political change. Their response to events such as the student demonstrations in 2011 and the Occupy movement was relatively resigned and stoical:

protest all you want it wont change anything

it doesnt work, 100′s of protests can happen but nt one will work it takes more then people sitting protesting for anything to b done

take a look at the education protests [ … ] we tried SO HARD [ … ] we lost

In many respects, these pessimistic views seem to be underpinned by a strong sense across the focus groups that the political class is an unresponsive elite with little regard for the views of young people, and not easily influenced by the actions of, and challenges posed by, citizens – especially young citizens:

i dont feel we have a chance of making a difference to things we care about as the desisions have already been made for us

it feels like the public have no say. the governemt already have everything planned out

the only way the government will actually take notice of us will be if we acted in the same way the people in the arab uprisings did but what could be a good enough reason to act like that ?

Confidence in the democratic process and the political class

Whilst this youth group appears to be relatively fatalistic with respect to the scope and prospects for achieving political influence and effecting meaningful political change, they are broadly supportive of democratic ideals and processes. For instance, results from the online survey suggest a majority of young people in Britain are committed to the principle of voting (57%), with a sizeable group expressing support for competitive elections (48%).

However, the current youth generation is deeply averse to professional politicians and those who have been elevated to positions of formal political power through these elections. The survey indicates that 81% of young people disapprove of the political class. The data from the focus groups reveal the source and extent of this ambivalence – and in some cases hostility – towards the political class. On the one hand, professional politicians are seen as remote and incapable of governing in an empathetic manner or with due regard for the interests and aspirations of young citizens:

they seem to live in a totally different world to everyone else

they dont think like the majority of the ‘common person'

i dont think they can really relate to students or youths … clearly theres a problem when students are protesting and youths are rioting

On the other hand, this political class is considered to be cynical and self-serving, and lacking any serious commitment towards championing the concerns of young people. These views are typified by the following statements:

i think the politicians have lost the trust of our generation

… the goverment just dose what it wants to do and dosent listen to what the public want they say they will make changes so you will vote for them and then dont back up there promises

… once a aprty is voted into power their views often change, as seen this year when two largely apposing parties joined in a coalition

Young people's reactions to hypothetical electoral administrative reforms

Rather than entrenched political apathy, the analyses presented above reveal that young people's persisting disengagement from formal democratic politics is symptomatic of their alienation from this politics and of their scepticism of the motives and behaviours of the political classes. Although they are concerned observers of local, national and global affairs, they find formal politics remote and unappealing. Given this context, how might government intervene to reduce the ongoing young citizen–state disconnect? In the online survey, young people were asked to indicate their responses to different proposed measures that government might introduce for the purposes of stimulating increased electoral turnout. These included hypothetical proposals to encourage increased electoral turnout as well as a system to make voting compulsory.

– summarise young people's reactions to several different hypothetical electoral reforms designed to make voluntary voting more accessible to citizens. The findings suggest that voting via the Internet or digital TV would be particularly effective in terms of encouraging them to vote at the next general election (57%). For the remaining five proposals considered, the largest groups reported that such changes would make no difference to their likelihood to vote in the future.

Table 1. Proposals to increase voting by whether voted at the 2010 general election.

Table 2. Proposals to increase voting by likelihood to vote at the next general election.

Table 3. Proposals to increase voting by socio-demographic factors.

The chi-square analyses (X2) in indicate that whether or not survey respondents voted at the previous 2010 General Election had no statistically significant influence on their reactions to these six electoral reform scenarios. However, reveals considerable variation in the views of those intending to vote in the future and those intending to abstain. This suggests that the main target group of such electoral reforms – those who report that they are least likely to vote in the future – are significantly less positive about each of these reform ideas than are those who claim that they are already intending to vote. This is the case for each of the proposals except the item, ‘ … able to vote over more than one day', where the variation is considerable but not statistically significant. This is an important finding, suggesting intending abstainers are least convinced by the proposals. However, also reveals that even in this particular sub-group, there exists a sizeable minority that might be cajoled into voting in the future should such initiatives be implemented. Thus, if voting were to be available by the Internet or by digital TV, nearly half of intending abstainers (45%) report that they might be persuaded to vote; furthermore, nearly a third of this sub-group (32%) were open to the idea of voting by phone. These findings suggest that introducing increased flexibility into the electoral provisions might help to encourage some to reconsider their stated intention to abstain from participating in future elections.

There is some evidence that young people's reactions to the proposed electoral initiatives are linked to their socio-demographic backgrounds. As indicates, there are statistically significant ethnicity and gender gaps. Young females (X2 = 10.01, p < .01) and those from BME backgrounds (X2 = 7.04, p < .05) are more positively predisposed to postal voting than are other young people. A similar pattern was also revealed for voting by the Internet or digital television, with significantly greater support from young females (X2 = 12.14, p < .01) and those from BME backgrounds (X2 = 6.80, p < .05) than from their respective counterparts. Young women are also considerably more persuaded by the value of telephone voting than are young males (X2 = 16.82, p < .001). There are no significant variations between different socio-demographic groups for the remaining three items. Furthermore, the data also suggest that neither social class, level of formal educational qualifications nor whether or not they have chosen to remain in full-time education performs a statistically significant role in shaping young people's perspectives (p > .05) with regard to any of the electoral initiatives considered.

The results of linear regression analyses indicate that whether or not young people had voted in the previous 2010 General Election had no significant bearing on their attitudes towards these electoral reforms (p > .05). However, future turnout intention is a statistically significant predictor of their reaction to two of the electoral items. Those claiming an existing intention to vote in a future general election were even more likely to do so if polling stations were open for 24 hours (Beta = −.097, p = .008) or vote by post (Beta = −.072, p = .047). All other variables were not significant predictors of any of the initiatives (p > .05).

Interestingly, the only evidence of young people's socio-demographic background displaying any impact on their views of these electoral reform ideas was in terms of their gender. Females were more likely than males to express an interest in voting by post (Beta = .082, p = .012), or by phone (Beta = .123, p < .001), or by Internet or digital television (Beta = .108, p = .001). None of the other socio-demographic variables entered into the regression were significant predictors (p > .05) of respondents’ reactions to the proposed electoral initiatives.

Young people's reactions to the prospect of compulsory voting

The young survey participants were also asked how the introduction of a system of compulsory voting might impact on their future voting intentions. Perhaps not surprisingly, the largest group reported that such a shift in electoral law would increase their likelihood to vote in any forthcoming contest (47%). Nonetheless, there remained a significant minority (39%) who stated that such a system would make no difference with respect to their decision on whether or not to vote.

Of particular note, considers variations in young people's reactions to the idea of compulsory voting by comparing the views of those who claimed to have voted at the 2010 General Election with those who declared that they had not voted. The chi-square analyses indicate the presence of statistically significant differences in the views of these two groups. In particular, past abstainers were considerably more likely than their voting counterparts to express an intention to vote in the future should such a system of compulsory voting be introduced (56% and 48%, respectively). However, a substantial minority of the ‘non-voters' (31%) claimed that such a system would have no impact at all, and that they would continue to abstain from voting. Furthermore, a significant group of ‘non-voters' (13%) also reported that they would actually be less inclined to vote should they be compelled to do so in law. This suggests that such a reform would actually harden abstainers’ resolve to boycott future elections.

Table 4. Proposals to introduce compulsory voting by whether voted at the 2010 General Election.

Interestingly, when projecting forward, the chi-square analyses reported in reveal statistically significant differences between those who claim an intention to vote in the future and those who plan to abstain from doing so. For instance, nearly two-thirds of those who state that they are already ‘very unlikely' to vote at the next general election claim that any introduction of compulsory voting would either not change their intentions to abstain (43%) or would be further even further disinclined to vote (22%). These findings suggest that changing electoral law so that young people are compelled to vote might be counter-productive, and serve to reinforce existing feelings of resentment.

Table 5. Proposals to introduce compulsory voting by likelihood to vote at the next general election.

The data in also indicate important and statistically significant socio-demographic differences in terms of young people's reactions to the prospect of making voting compulsory. Men are more resistant to this idea than are women, while white youth are less likely to support such plans than are those from BME groups. As might be expected, education is a key variable; those who had attained higher level qualifications and those who had opted to remain in full-time education were considerably more dubious about compulsory voting than other young people, perhaps reflecting a critical and questioning outlook shaped by exposure to prolonged education. However, there is no discernible evidence of any social class gap, and those young people from lower social class backgrounds and those from managerial/professional backgrounds are evenly divided in terms of their views on the merits of compulsory voting.

Table 6. Proposals to introduce compulsory voting by socio-demographic factors.

The results from the linear regression analyses suggest that neither past voting turnout nor future intention to vote are significant predictors of young people's reception to the idea of compulsory voting. Young people's socio-demographic backgrounds were significant predictors only in respect of the educational trajectory independent variable (Beta = −.106, p = .002). Those in full-time education were more likely to vote in the future if voting was compulsory. None of the other socio-demographic variables (gender, ethnicity, social class nor educational qualifications gained) were found to be significant predictors (p > .05).

Conclusion

The evidence presented in this study suggests that contrary to much traditional political science understanding, the decision of many of the 18-year-old attainers in our study to abstain from full participation in the democratic process is not borne of apathy or of self-exclusion. Instead, the data reveal that British young people are interested in political matters. However, today's youth are anxious that there exist only relatively few available opportunities for them to meaningfully participate in formal politics; moreover, they consider that those who have been elected to public office on their behalf have failed to champion their issue interests. The weight of evidence from our study therefore seems to support the anti-apathy thesis – that young people's disengagement from formal politics and democratic institutions is in part because of their interest in new styles and forms of politics, as well as political alienation (Henn, Weinstein, and Wring Citation2002; Marsh, O'Toole, and Jones Citation2007).

They are of the opinion that the burden of responsibility therefore rests with the political class to initiate resolution of the ongoing young citizen–state disconnect. However, what are the prospects of stimulating increased electoral participation and of progressing towards such ends? Can young people be persuaded to vote by reforming electoral arrangements so that voting is made more accessible and young person-friendly? The data from our study indicate that such methods as those listed in – would have an impact across the full youth cohort. However, the effects are not uniform, and the data reveal some import differences across particular sub-groups of young people. Firstly, those who might be considered as the key focus of the proposed measures – young people who did not vote at their first General Election and also those who intend to abstain in the future – claim that such reforms would have little impact on their determination to avoid the polls in future elections. Interestingly, and contrary to Hypothesis 1, there are no discernible differences here in terms of the attitudes of past voters and non-voters. However, the data lend support to Hypothesis 2, with those intending to abstain in future elections found to be significantly less persuaded of the merits of these electoral proposals than are those already considering engaging in the electoral process. The impact of socio-demographic background on young people's reception to these electoral measures is mixed, suggesting that Hypothesis 3 is only partially supported by the data. There are indications of both gender and ethnicity gaps with respect to some of the electoral items, but there is no evidence that age-completed education, educational qualifications or social class structure young people's attitudes to these electoral reform scenarios.

Would a more coercive approach represent a viable solution? Our data suggest that more young people would vote if compelled to do so in electoral law. However, the key question is whether such a compulsory system of voting would truly strengthen young people's connection with formal democratic politics and institutions, given that they feel such a deep aversion towards the political parties and those professional politicians listed on ballot papers. The data reveal that previous non-voters as well as likely future abstainers would be particularly resistant to compulsory voting, confirming Hypotheses 4 and 5. Indeed, such compulsion may actually serve to reinforce a deepening resentment, rather than to engage young people in a positive manner. Interestingly, young people's socio-demographic backgrounds have particular impact on this. The results from the chi-square analyses suggest support for Hypothesis 6 that, with the exception of social class, socio-demographic background variables significantly structure young people's reaction to compulsory voting. This is the case for gender, ethnicity, level of educational qualifications, as well as whether or not in full-time education. Furthermore, the linear regression analyses offer partial support for this hypothesis, indicating that those who have left full-time education are significantly less predisposed to compulsory voting than are those who have opted to remain in the study.

If young people are to be motivated to engage with formal politics and the electoral process, then the political class needs to look beyond merely ‘procedural–technical' programmes and innovations. For instance, the introduction of initiatives that encourage young people to register to vote is positive in intention, but not always successful. Thus, the new system for individual electoral registration (IER) that was introduced in Britain in 2014 raises several implementation challenges. In particular, it is estimated that 800,000 people had been lost from the electoral register by January 2016 (Mason Citation2016). Furthermore, evidence suggests that those least likely to register to vote under IER include younger people, students, those on lower incomes and society's most vulnerable groups (Fisher and Hillman Citation2014).

Instead of an over-reliance on such purely administrative reforms to resolve the young citizen–state disconnect, what is needed is a thoroughgoing review of the way in which formal politics reaches out to young people, and prepares them for political participation. As Stoker reports, young people are open-minded about electoral politics and do not have a hardened disaffection; they are more likely than not to express faith in voting and the democratic process although not with the politicians that inhabit that world (Stoker Citation2014). It may be that young people might opt to engage in elections if they can be convinced that as an age cohort they themselves and their issue priorities are treated seriously by politicians. Reducing the voting age to 16 might assist this process by persuading young people that they are valued (rather than maligned) by the political class. In doing so, it may contribute to the conversion of their democratic commitment into democratic participation. There is no consensus on whether extending the vote to 16-year-olds should be considered a basic right. Detractors question both the maturity of adolescents aged 16 and 17 who have not yet had the opportunity to develop advanced autonomous knowledge and understanding of politics (Chan and Clayton Citation2006), and also their lack of motivation which it is argued might reduce the overall levels of electoral participation (Electoral Commission Citation2004). Advocates argue that extending the vote to young people while they are ‘members of settled communities' – living at home and attending school – might increase their turnout in elections (Berry and Kippin Citation2014, 7), and evidence from Austria suggests that 16- and 17-year-olds are more likely to vote than 18–25-year-olds (Zeglovits and Aichholzer Citation2014). Furthermore, it follows that if socialised into voting within these contexts, they are more likely to continue to do so in the future as voting becomes habit-forming (Franklin Citation2004). Finally, supporters argue that enfranchising 16- and 17-year-olds would ensure that their concerns are brought to the attention of the political class (Wagner, Johann, and Kritzinger Citation2012). Whether the political class chooses to act on those concerns, however, is a different matter. Although the UK Government recently ruled against votes for 16-year-olds at the forthcoming EU Referendum, there is a momentum developing for such a reform to British electoral law that is supported by several opposition parties. When these younger groups were granted the right to vote at the Scottish Independence Referendum in 2014, 80% of them cast a ballot. This suggests that young people are not innately averse to voting on matters that are of critical consequence for them. And neither do they find the current voting arrangements a barrier to participation.

The conclusion that we must draw from this research is that there is no single solution to the ongoing young citizen–state disconnect in Britain. By themselves, the introduction of electoral administrative arrangements intended to make voting more accessible would likely have some impact; critically, however, those youth determined to abstain at the next election appear not to be convinced by the prospect of such new electoral methods. Similarly, compulsory voting might result in a quantitative increase in the numbers of young voters, but the evidence presented here suggests that it would not necessarily improve the quality of broader political engagement – and may serve to reinforce young people's resentment of the operation of democratic politics in Britain. If young people are to be persuaded to vote and to participate more broadly in formal democratic politics, the onus is on the political class to think creatively about how to make such democratic participation more meaningful and attractive to Britain's youth generation.

Acknowledgements

The project that informs this article was conducted with Nick Foard at Nottingham Trent University. The authors would like to thank Paul Carroll and Sarah Pope at Ipsos MORI, both for their preparation of the data and for their general contribution to the project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Matt Henn http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1063-3544

Ben Oldfield http://orcid.org/0000-0001-6229-5439

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. In , each bar represents the number of respondents who mentioned the item.

References

- Beck, U. 1992. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. London: Sage.

- Berry, C. 2012. The Rise of Gerontocracy? Addressing the Intergenerational Democratic Deficit. London: Intergenerational Foundation.

- Berry, R., and S. Kippin. 2014. “Introduction. It Is Time to Decide Whether to Enfranchise 16 and 17 Year Olds.” In Should The UK Lower The Voting Age to 16? edited by R. Berry, and S. Kippin, 7–8. London: Political Studies Association.

- Birch, S., G. Gottfried, and G. Lodge. 2013. Divided Democracy: Political Inequality in the UK and Why It Matters. London: Institute of Public Policy Research.

- Boon, M., J. Curtice, and S. Martin. 2007. Local Elections Pilot Schemes 2007: Main Research Report. London: The Electoral Commission.

- Chan, T. W., and M. Clayton. 2006. “Should the Voting Age Be Lowered to Sixteen? Normative and Empirical Considerations.” Political Studies 54 (3): 533–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2006.00620.x

- Dalton, R. J. 2008. The Good Citizen: How a Younger Generation Is Reshaping American Politics. Revised ed. Washington: CQ Press.

- Electoral Commission. 2004. Age of Electoral Majority: Report and Recommendations. London: Electoral Commission.

- Electoral Commission. 2006. Compulsory Voting Around the World. Accessed February 8, 2016. http://www.electoralcommission.org.uk/__data/assets/electoral_commission_pdf_file/0020/16157/ECCompVotingfinal_22225-16484__E__N__S__W__.pdf

- Farthing, R. 2010. “The Politics of Youthful Antipolitics: Representing the ‘Issue’ of Youth Participation in Politics.” Journal of Youth Studies 13 (2): 181–195. doi: 10.1080/13676260903233696

- Fischer, C. 2011. “Compulsory Voting and Inclusion: A Response to Saunders.” Politics 31 (1): 37–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9256.2010.01400.x

- Fisher, S. D., and N. Hillman. 2014. Do Students Swing Elections? Registration, Turnout and Voting Behaviour Among Full-Time Students. Oxford: Higher Education Policy Institute.

- Franklin, M. N. 2004. Voter Turnout and the Dynamics of Electoral Competition in Established Democracies since 1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Furlong, A., and F. Cartmel. 2012. “Social Change and Political Engagement among Young People: Generation and the 2009/2010 British Election Survey.” Parliamentary Affairs 65 (1): 13–28. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsr045

- Giddens, A. 1991. Modernity and Self Identity: Self and Society in the Late Modern Age. Cambridge: Polity.

- Hay, C. 2007. Why We Hate Politics. Cambridge: Polity.

- Heath, A., S. Fisher, D. Sanders, and M. Sobolewska. 2011. “Ethnic Heterogeneity in the Social Bases of Voting at the 2010 British General Election.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion & Parties 21 (2): 255–277. doi: 10.1080/17457289.2011.562611

- Henn, M., and N. Foard. 2012a. “Young People, Political Participation and Trust in Britain.” Parliamentary Affairs 65 (1): 47–67. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsr046

- Henn, M., and N. Foard. 2012b. “Young People and Politics in Britain: How Do Young People Participate in Politics and What Can Be Done To Strengthen Their Political Connection?.” Accessed February 8, 2016. http://gtr.rcuk.ac.uk/project/FFD37080-0E24-473F-A3EA-0BA4CBF480C5

- Henn, M., and N. Foard. 2014. “Social Differentiation in Young People's Political Participation: The Impact of Social and Educational Factors on Youth Political Engagement in Britain.” Journal of Youth Studies 17 (3): 360–380. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2013.830704

- Henn, M., M. Weinstein, and D. Wring. 2002. “A Generation Apart? Youth and Political Participation in Britain.” British Journal of Politics and International Relations 4 (2): 167–192. doi: 10.1111/1467-856X.t01-1-00001

- Hill, L. 2011. “Increasing Turnout Using Compulsory Voting.” Politics 31 (1): 27–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9256.2010.01399.x

- Holmes, M., and N. Manning. 2013. “He's Snooty ‘im’: Exploring ‘White Working Class’ Political Disengagement.” Citizenship Studies 17 (3–4): 479–490. doi: 10.1080/13621025.2013.793082

- Hooghe, M., and K. Pelleriaux. 1998. “Compulsory Voting in Belgium: An Application of the Lijphart Thesis.” Electoral Studies 17 (4): 419–424. doi: 10.1016/S0261-3794(98)00021-3

- Hooghe, M., and S. Marien. 2014. “How to Reach Members of Parliament? Citizens and Members of Parliament on the Effectiveness of Political Participation Repertoires.” Parliamentary Affairs 67 (3): 536–560. doi: 10.1093/pa/gss057

- House of Commons Political and Constitutional Reform Committee. 2014. Voter Engagement in the UK, Fourth Report of Session 2014–15. London: The Stationery Office Limited.

- Ipsos MORI. 2015. “ How Britain Voted in 2015: the 2015 Election – Who Voted for Whom?” Ipsos MORI. Accessed February 8, 2016. https://www.ipsos-mori.com/researchpublications/researcharchive/3575/How-Britain-voted-in-2015.aspx?view=wide

- Jensen, C. B., and J.-J. Spoon. 2011. “Compelled without Direction: Compulsory Voting and Party System Spreading.” Electoral Studies 30 (4): 700–711. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2011.06.014

- Lever, A. 2008. “‘A Liberal Defence of Compulsory Voting’: Some Reasons for Scepticism.” Politics 28 (1): 61–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9256.2007.00312.x

- Lijphart, A. 1997. “Unequal Participation: Democracy's Unresolved Dilemma.” American Political Science Review 91 (1): 1–14. doi: 10.2307/2952255

- Marsh, D., T. O'Toole, and S. Jones. 2007. Young People and Politics in the UK. Apathy or Alienation? Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mason, R. 2014. “UK Should Consider E-Voting, Elections Watchdog Urges.” The Guardian Online, March 26. Accessed February 8, 2016. http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2014/mar/26/uk-e-voting-elections-electoral-commission-voters

- Mason, R. 2016. “Electoral Register Loses Estimated 800,000 People.” The Guardian Online, January 31. Accessed February 8, 2016. http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/jan/31/electoral-register-loses-estimated-800000-people-since-changes-to-system?CMP=Share_iOSApp_Other

- Micheletti, M., and D. Stolle. 2008. “Fashioning Social Justice through Political Consumerism, Capitalism, and the Internet.” Cultural Studies 22 (5): 749–769. doi: 10.1080/09502380802246009

- Mycock, A., and J. Tonge. 2012. “The Party Politics of Youth Citizenship and Democratic Engagement.” Parliamentary Affairs 65 (1): 138–161. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsr053

- Nie, N., S. Verba, and J. Kim. 1974. “Political Participation and the Life-Cycle.” Comparative Politics 6 (3): 319–340. doi: 10.2307/421518

- Norris, P. 2003. “Young People and Political Activism: From the Politics of Loyalties to the Politics of Choice?” Accessed February 8, 2016. http://www.hks.harvard.edu/fs/pnorris/Acrobat/COE.pdf

- Oser, J., M. Hooghe, and S. Marien. 2013. “Is Online Participation Distinct from Offline Participation? A Latent Class Analysis of Participation Types and Their Stratification.” Political Research Quarterly 66 (1): 91–101. doi: 10.1177/1065912912436695

- Parry, G., G. Moyser, and N. Day. 1992. Political Participation and Democracy in Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Pattie, C., P. Seyd, and P. Whiteley. 2004. Citizenship in Britain: Values, Participation and Democracy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Phelps, E. 2012. “Understanding Electoral Turnout among British Young People: A Review of the Literature.” Parliamentary Affairs 65 (1): 281–299. doi: 10.1093/pa/gsr056

- Saunders, B. 2010. “Increasing Turnout: A Compelling Case?” Politics 31 (1): 70–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9256.2009.01368.x

- Singh, S. P. 2014. “Compulsory Voting and the Turnout Decision Calculus.” Political Studies 63 (3): 548–568. doi: 10.1111/1467-9248.12117

- Sky News. 2015. “Six Out Of 10 Young Voters Turn Out For Election.” Sky News, May 9. Accessed February 8, 2016. http://news.sky.com/story/1479819/six-out-of-10-young-voters-turn-out-for-election

- Sloam, J. 2014. “New Voice, Less Equal: The Civic and Political Engagement of Young People in the United States and Europe.” Comparative Political Studies 47 (5): 663–688. doi: 10.1177/0010414012453441

- Stoker, G. 2006. Why Politics Matters: Making Democracy Work. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Stoker, G. 2014. “Political Citizenship and the Innocence of Youth.” In Beyond the Youth Citizenship Commission: Young People and Politics, edited by A. Mycock and J. Tonge, 23–26. London: Political Studies Association.

- Tenn, S. 2007. “The Effect of Education on Voter Turnout.” Political Analysis 15 (4): 446–464. doi: 10.1093/pan/mpm012

- Tonge, J., A. Mycock, and B. Jeffery. 2012. “Does Citizenship Education Make Young People Better-engaged Citizens?” Political Studies 60 (3): 578–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2011.00931.x

- Tormey, S. 2015. The End of Representative Politics. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Wagner, M., D. Johann, and S. Kritzinger. 2012. “Voting at 16: Turnout and the Quality of Vote Choice.” Electoral Studies 31 (2): 372–383. doi: 10.1016/j.electstud.2012.01.007

- Wattenberg, M. 2008. Is Voting for Young People? New York: Pearson Longman.

- Westholme, A., and R. G. Niemi. 1986. “Youth Unemployment and Political Alienation.” Youth and Society 18 (1): 55–80.

- Whiteley, P. 2012. Political Participation in Britain. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Zeglovits, E., and J. Aichholzer 2014. “Are People More Inclined to Vote at 16 than at 18? Evidence for the First-time Voting Boost among 16- to 25-Year-Olds in Austria.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 24 (3): 351–361. doi: 10.1080/17457289.2013.872652