ABSTRACT

This article contributes to an understanding of diversity in beliefs and practices among young religious ‘nones’ who report the absence of a specific religious faith. It focuses on those describing themselves as atheist, agnostic or otherwise of ‘no religion’ within (a) a large-scale survey of over ten thousand 13–17-year-olds, and (b) interviews, discussion groups and eJournal entries involving one hundred and fifty-seven 17–18-year-olds, in three British multi-faith locations. Compared to the study population as a whole, the young religious ‘nones’ were particularly likely to be white and born in Britain. There was, nonetheless, considerable diversity among this group in beliefs and practices: almost half the survey members mentioned some level of belief in God and most of the interview participants pointed to some presence of religion in their lives. Being a religious ‘none’ is, furthermore, not necessarily a stable identity and some young people had already shown considerable fluidity over their life cycles. Around half the survey members said they had maintained similar religious views to their mothers, but participants in both quantitative and qualitative studies pointed to the impact of their experiences and interactions, as well as the role of science, as factors affecting their beliefs and practices.

Introduction

Britain, in common with many other European countries, has seen a decline in organised religion among the long-settled indigenous population over recent years. This is reflected in the growing proportion of the population who report they have no religion. Those who identify themselves in this way are, however, a heterogeneous group and may describe themselves as atheist, agnostic, humanist or one of a range of other labels. In addition, they are likely to vary considerably in their religiosity. The focus of the present article is on understanding the essence and varieties of non-religion. Specifically, how do young people who say they are not religious identify and describe themselves, how far and in what ways does religion play a role in their lives, and how are non-religious identities developed and maintained.

This article draws on data from the Youth On Religion study (Madge, Hemming, and Stenson Citation2014), conducted in three multi-faith locations in England, and examines these questions from the perspectives of young people attending secondary schools. It is set within the context of contemporary scholarship on young people and identity that has often drawn on the concepts of individualisation and liberal individualism. The former contends that as a result of social change and the decline of traditional authorities such as the family and the Church, individuals now have more opportunity to construct their own identities and biographies from a myriad of different options and influences (Beck and Beck-Gernsheim Citation2001; Giddens Citation1991). The latter is a broader notion that conveys how everyone should make their own decisions in life but that they should also allow others to do the same: this concept posits limits to egoistical individuation. In line with broader findings reported elsewhere (Madge, Hemming, and Stenson Citation2014), the article takes a symbolic interactionist approach (Berger and Luckmann Citation1966; Goffman Citation1959; Lindesmith, Strauss, and Denzin Citation1999) in examining how young people construct, negotiate and sustain their identities through their interactional settings within this broader framework.

These new findings contribute to the sparse, albeit growing, literature on the religious ‘nones’, particularly so far as younger members of the community are concerned. They therefore make an important contribution to the wider discipline of youth studies which has not yet engaged extensively with this important topic (see Hemming Citation2017). Bainbridge (Citation2005), Bullivant (Citation2008) and Tomlins and Beaman (Citation2015) all point to the lack of sociological research on atheism and non-belief. Bainbridge (Citation2005) argues that the dearth of research in this area is a problem because (a) it can limit our understanding of religion itself by failing to investigate its absence, (b) it misses an important social phenomenon that we need to attend to in its own right and (c) there has been a recent increase in popular and media interest in atheism (often characterised as the ‘New atheism’) that has made addressing this omission even more urgent.

Growth and characteristics of the religious ‘nones’

The recent rise in the numbers of people identifying as non-religious, or the religious ‘nones’, in Europe, North America and other Western contexts over the last few decades has been well documented (e.g. Hassell and Bushfield Citation2014; Tomlins and Beaman Citation2015; Wallis Citation2014; Zimmerman et al. Citation2015). Tomlins and Beaman (Citation2015) report a range of estimates of the non-religious, from around 1 in 10 to 1 in 4 of the world’s population.

Zuckerman (Citation2007) lists Britain as fifteenth among nations with the largest proportion of non-believers. This estimate of 31–44% of people as atheist, agnostic or non-believers is higher than the 25% who ticked ‘no religion’ in the 2011 Census, but lower than suggested by the British Social Attitudes survey: just over half of all adults polled in 2013 reported no religion (Woodhead Citation2016), representing a rise of two-thirds in the 30 years since the first poll of this kind. The increase in the no religion group tends to run in parallel with a decrease in those identifying with Christianity. As the greatest prevalence of non-religion is found among younger people, it is likely that numbers overall will continue to rise over time for this reason alone.

Certain demographic factors tend to typify atheists and the religious ‘nones’. British Census data suggest that non-religious people are more likely to be male, white, better educated than average, and live in particular geographical locations (Brown and Lynch Citation2012; Voas and McAndrew Citation2012). Additional evidence from the 2011 Census suggests that members of the ‘no religion’ group are predominantly drawn from the white British-born population. Two UK surveys carried out by YouGov for the Westminster Faith Debates (Woodhead Citation2016) generally confirmed these patterns, finding that younger adults (those under 30 years) and the more ethically liberal are most likely to identify themselves as having ‘no religion’. Comparable findings have emerged internationally in relation to those labelling themselves as atheist (Beit-Hallahmi Citation2007).

Most of the available British data on the characteristics of the religious ‘nones’ relate to adults. Smith and Denton (Citation2005), however, report that the non-religious in their large American study of young people were more likely to have divorced parents, poorer relationships with their parents, and be older rather than younger teens. Young males were more likely than their female counterparts to self-identify as non-religious in a large Australian study (Mason, Singleton, and Webber Citation2007). In Europe, research with young people has focused less on the religious ‘nones’ as a distinct group, but Ziebertz and Kay (Citation2006) found that young males were less likely than young females to identify as a religious ‘believer’ or participate in prayer in many national contexts, including the UK and the Netherlands.

Varieties of religious ‘nones’

Lee (Citation2015, 203) has suggested that non-religion can be seen as ‘a phenomenon primarily identified in contrast to religion; a stance towards religion identified as other than religious, including but not limited to a rejection of religion’. Existing research, mainly with adult populations, clearly demonstrates how such non-religion can be expressed in many different ways. Tomlins and Beaman (Citation2015), for instance, illustrate how religious ‘nones’ may self-identify as ‘agnostic, atheist, agnostic-atheist, apathetic, anti-theist, bright, freethinker, humanist, irreligious, materialist, naturalist, rationalist, sceptic, secularist, a mix of these descriptors, or something else altogether’. Other authors point to a range of additional sub-divisions among young people. An interview study of 16–26-year-old British University students distinguished between atheists who believe in the non-existence of God and those who do not believe in God (Catto and Eccles Citation2013), while Mason, Singleton, and Webber (Citation2007) have described those following ‘the secular path’ as the non-religious, the ex-religious and the undecided.

Cotter’s (Citation2015) work adds further to the complexity of the non-religious label through his work with undergraduate students at the University of Edinburgh. He found that respondents presented with a list of 33 possible religious and non-religious labels were often happy to select multiple labels, some of which seemed in conflict (e.g. an atheist, agnostic, Buddhist). Students explained these choices as pragmatic self-representation in different situations or self-perceived changes over time. Cotter argues that this shows that ‘(non)religious identification can be fluid and dynamic’ (180). The mixture of religious and non-religious labels for some students also supports Day’s (Citation2011) arguments about ‘nominal Christians’, where some of the religious labels are used to denote identity-culture rather than actual religious belief or practice.

Distinguishing between self-reported identities is important, particularly between atheists and the broader group of religious ‘nones’. The former generally do not believe in God, while the latter may say they do. Indeed, Cragun et al. (Citation2012) found that only 56% of survey participants who identified as ‘no religion’ believed ‘there is no such thing as God’, and Bullivant (Citation2008) similarly found the adults may say they had ‘no religion’ but still believe in God. Comparable findings have emerged from two recent British YouGov surveys of 8455 adults where fewer than half of the no religion group say they are atheist, and only 13% indicate that they are strongly anti-religious. Around half appear to be what Woodhead (Citation2016) has referred to as ‘doubters and believers’: 5.5% and 11%, respectively, thought that there is definitely, or probably, a God or some ‘higher power’, compared with 39% and 29% of those with a religious identity. One in four of these ‘nones’ further say they have taken part in some form of spiritual practice during the previous month even if none had taken part in communal religious practices such as worship. Both Smith and Denton (Citation2005) and Mason, Singleton, and Webber (Citation2007) have also confirmed the very wide diversity of beliefs and practices among the young non-religious community.

As suggested by these findings, self-identification reflects the choice to use a certain label regardless of beliefs, behaviours and experiences. Wallis (Citation2014) set out to investigate the reasons why young people aged 14 and 15 from 2 English secondary schools chose to identify as ‘no religion’, finding that there seemed to be an assumption that in order to identify as a religious person, you had to accept every belief attaining to the faith in question. Thus young people might believe in certain parts of a religion, or believe in God and pray sometimes, but still tick ‘no religion’. Self-identification may also be dependent on context. Both Cotter (Citation2015) and Mumford (Citation2015) argue that religion comes more to the fore when there is a clash between personal ‘sacred’ values, such as human rights, equality and freedom and religious practices or ideologies, such as homosexuality or contraception. Lynch (Citation2012) and Knott (Citation2013) have posited the notion of ‘secular sacreds’ that refer to the values and principles of modern secular life that are considered fundamental and non-negotiable.

Pathways to non-religion

Just as there is diversity in the beliefs and behaviours of those self-identifying as non-religious, so too is there great variety in the routes taken to achieve these positions. For instance, while some people grow up without religion and remain that way across the life-span, others demonstrate considerable ‘switching, matching and mixing’ over the course of their lives (Putnam and Campbell Citation2010). Moreover, the change may sometimes be more in terms of how they choose to identify themselves, rather than in their beliefs and outlook.

There is a considerable literature on the intergenerational transmission of religious belief and expression. The family is traditionally the initial influence on a child’s religiosity (Berger and Luckmann Citation1966; Madge, Hemming, and Stenson Citation2014), playing a key role before friends and wider community influences come to the fore (Kay and Francis Citation1966; Mason, Singleton, and Webber Citation2007; Smith and Denton Citation2005). Brown (Citation2009) and others have further attributed secularisation and the rise of the ‘nones’ to the failure of religious parents to pass on their beliefs and practices to their children. The significance of the family appears to apply in the case of those who are religious as well as those who are not, although there is some suggestion that the links may be stronger for the former. Woodhead (Citation2016) reports British Social Attitudes survey figures showing that 95% of those brought up with no religion retain their identities, whereas 40% of those brought up Christian move from a religious to a non-religious identity. It seems that such patterns may become more marked over time. Merino (Citation2012) found that recent cohorts of children raised as non-religious in the USA are less likely to revert to a religious tradition in adulthood than was previously the case.

Families, however, are not the only significant influence on religiosity, and wider interactions and experiences can be critical. Mumford (Citation2015) argues that although non-religious stances are often presented as reasoned and rational viewpoints, or disagreements with theological positions, these stances are very often initially informed through ‘emotional knowledge’. Although participants in her London study (from three different non-religious groups) often cited intellectual reasons for moving to a non-religious stance, it seemed there was usually an emotional event or experience at the root of these decisions. Examples included sudden and instant insights about the ‘silliness’ of a religious doctrine, death of a loved one, or an emotional response to reading Richard Dawkins. The evidence thus suggests that belief has emotional as well as intellectual origins.

Catto and Eccles (Citation2013) build on these findings through 24 qualitative interviews with young British atheists, aged 16–26, accessed via advertisements on social network sites. Almost all respondents described themselves as atheist or humanist and talked positively about their beliefs (rather than merely a disbelief of God), espousing values of freedom and equality, and stressing a strong affinity with science, evidence and proof. Upbringing was significant as non-religious identity was bound up with patterns of ‘correspondence’, ‘compliance’, ‘challenge’ and ‘conflict’ within family relationships (see Hopkins et al. Citation2010) and the emotion they generated, but social and cultural structures were also important. Participants were critical of religion, particularly its role in the public sphere such as faith schools and creationism teaching, but were more tolerant of personal religion so long as individuals are not hypocritical or evangelistic. Encounters with explicitly religious people had also often reinforced their atheist positions. Other research, too, highlights how experiences over the life course can turn young people away from religion (Mason, Singleton, and Webber Citation2007). Glaser and Strauss (Citation1971) have written about ‘significant turning points’ in this context, while Lindesmith, Strauss, and Denzin (Citation1999) have referred to the identity transformations that can occur.

Research questions

This article draws on findings from the Youth On Religion study to address the following questions

What are the demographics of the members of the study sample identifying as ‘no religion’?

Does religion have a place in the lives of these religious ‘nones’?

What are the pathways to self-reported ‘no religion’?

Is there a distinct non-religious identity?

Methods

The sample

The Youth On Religion study was a large-scale project, funded by the British AHRC/ESRC Religion & Society programme, looking at the meaning of religion in the lives of young people growing up in the three multi-faith locations of the London Boroughs of Hillingdon and Newham, and Bradford in Yorkshire (Madge, Hemming, and Stenson Citation2014). The study comprised an online survey with over ten thousand 11–17-year-olds attending schools or colleges, face-to-face discussion groups and interviews with one hundred and fifty-seven 17 and 18-year-olds, and eJournal entries from a smaller number. Young participants came from a range of faith positions including, most numerously, Muslims, Christians, religious ‘nones’, Sikhs, Hindus and those of mixed faith. While the survey participants are not necessarily fully representative of young people in the study areas, and are unlikely to be representative of those in more religiously homogeneous locations, the numbers are sufficiently large to make valid comparisons. This article draws crucially on those young people within the Youth On Religion study sample who described themselves, in one way or another, as being non-religious. Some reference is made to those identifying with a religious faith for comparative purposes.

In the study survey, participants were given the option of ticking a ‘no religion’ box or a range of religions (to mirror the Census), but were also given the opportunity to provide further descriptions as appropriate in a text box. An insufficient number of the group provided additional string data to make analysis of these data viable. We therefore cannot distinguish between the no religion survey group in terms of the label they gave themselves, although we can make many other distinctions between them. Almost one in five survey participants (N = 1940) self-reported a no religion identity.

Prior to discussion groups and interviews, participants were asked to write down their religious status in their own words. Overall, 3 in 20 (N = 24) fell within the broad no religion group.

Data collection and analysis

The Youth On Religion study employed mixed methods whereby a large-scale online survey preceded discussion groups and paired face-to-face interviews. Some pupils also kept eJournals. The survey questionnaire was designed to be undertaken during a single school or college lesson period, and all pupils in participating schools/colleges were eligible, subject to feasibility. The questionnaire covered topics including the participant’s background, attitudes towards religion, beliefs and practices in relation to religion, the impact of family, friends and other factors on religiosity, and the significance of religion within the community. A smaller sample of 17 and 18-year-old pupils, attending the schools in which the survey had been conducted, took part in the discussion groups and interviews on a fully voluntary basis. Discussion groups focused on religion in the local area/community, positive and negative aspects of religion, and the role of religion in education and society. The interviews sought to explore the survey findings in more detail. All data collected through these face-to-face methods were digitally recorded with consent and professionally transcribed.

The quantitative and qualitative data sets, derived from the online survey and face-to-face data collection, respectively, were collated and analysed with the assistance of statistical and qualitative analysis software. Further information on data analysis is provided by Madge, Hemming, and Stenson (Citation2014).

Findings

The demographics of the ‘No religion’ members of the youth on religion study sample

The gender, ethnicity, place of birth of respondent and place of birth of respondent’s mother, are shown in for both those who said they were religious ‘nones’ and those who identified with a specific religion. As can be seen, there was no significant gender difference between those who did and did not give themselves a religious label, but there were marked contrasts between them in terms of ethnicity, place of birth and place of mother’s birth. Those who fell within our no religion group were strikingly more likely than the rest to be white, and to have mothers born in the UK. They were also overwhelmingly likely to have been born in the UK themselves.

Table 1. Gender, ethnicity, place of birth and place of mother’s birth for those with and without a self-reported religious identity: survey data.

shows the descriptions participants in the qualitative part of the study gave themselves, pointing to the diversity of non-religious labels. The most popular response was to say simply ‘none’ or ‘no religion’ although six opted for ‘atheist’ and two for ‘agnostic’. Four gave other answers suggesting less certainty, wrote N/A or left the item blank: it was clear from the other information provided that they legitimately fell within the no religion group.

Table 2. Self-reported descriptions of no religion status provided by participants: discussion group and interview data.

All but 2 of the 24 in this group said they had been born in England; the other 2 were born in Russia and Brazil. All but three (one Asian, two mixed ethnicity) said their ethnicity was white; one of the others wrote Asian for their ethnicity and two indicated mixed ethnicity. Although these data are based on a relatively small number from a volunteer sample, it is noteworthy that members of the no religion group are not representative of the qualitative sample as a whole and are dramatically skewed towards white English/British ethnicity.

Previous research and UK Census data have indicated, for largely adult samples, that those who identify themselves as not religious are overwhelmingly of white ethnicity. This study has confirmed this pattern within a younger sample through both quantitative and qualitative data collection. It has, further, demonstrated how being born in the UK, and having a mother born in the UK, are also strong predictive factors of self-identification as non-religious. The Youth On Religion study was conducted in three multi-faith locations in Britain and clearly shows the intersections between background, culture and ethnicity (Madge, Hemming, and Stenson Citation2014). Contrary to many other reports (Cragun et al. Citation2012; Voas and McAndrew Citation2012) but in line with others (Australian Bureau of Statistics Citation2013), it was not able to show a gender difference in relation to religious affiliation.

It is important to note, nonetheless, that religious labels are not always fixed. was clearly illustrated in the qualitative study by two young people who changed from a religious to a non-religious identity once the interviews were underway. It was also shown by two young people who became unsure whether they were atheist or agnostic as their interviews progressed. As Wallis (Citation2014) has pointed out, ascribing labels depends critically on what those labels are seen as meaning. The following two quotes demonstrate how young people may opt for a no religious label because they do not feel they satisfy the criteria for a religious one.

I haven’t gone through a ceremony or process to enter a religion to be identified by one. So therefore I don’t think I have got a label for my religion. That’s why I put not applicable because I don’t feel I have one. (ALANFootnote1: male, no religion, religion not very important)

No, I don’t believe in God or religion, I just haven’t been brought up to. I think I am Christened so technically I probably am religious. But I don’t see myself as having a religion because I don’t follow it and I haven’t followed it, neither have my parents. (ANNA: female, no religion, religion not at all important)

The meaning of no religion for young people

Information gathered from both the survey and the interviews highlighted the diversity of the non-religious sub-sample. In particular it demonstrated that while many members of this group regarded religion as unimportant or irrelevant in their lives, there were others for whom religion maintained a role. For example, while 86% said religion was not at all important or not very important in their lives, a not insignificant minority were less certain: religion was regarded as important in some ways but not others for 11% and quite or very important for 3%.

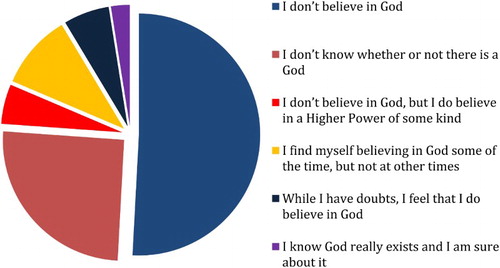

Perhaps more strikingly, and as illustrated by , only just over half (N = 976, 50.9%) of the survey sample identifying themselves as non-religious categorically stated that they did not believe in God. The largest group among the remainder (N = 485, 25.3%) were unsure about the existence of God, while 5.3% (N = 101)said they did not believe in God but did believe in a Higher Power of some kind, and 10% (N = 192) said they believed in God at least some of the time. Of the remainder, 6.1% (N = 116) said that they had doubts but did believe in God, and 2.5% (N = 47) were sure that God really exists. The following quotations from the qualitative data illustrate this diversity in beliefs about God.

I’m probably atheist out of everything. I just don’t believe in anything. (RICK: male, no religion, religion not very important)

I’m a bit sceptical when it comes to God and stuff. … I wouldn’t say I definitely don’t believe there is a God, but I wouldn’t say I wholly agree there is a God – I’m sort of in the middle. What’s that? Agnostic? Like some things happen and you think, oh actually you know, could it have been God? And you think, oh no, that could have been science. (ALAN: male, no religion, religion not very important)

Like I’m not saying that I don’t believe in God, I just don’t know what to think. I don’t know, I’m not fully decided yet. I don’t know. (ANNETTE: female, no religion, religion not very important)

I think there probably could be something there but I’m not sure what it is at the moment. (BOBBIE: female, no religion, religion not very important)

I don’t have to literally see it to believe it, but it’s not something I’ve ever really looked into properly. (LOUISE: female, no religion, religion not very important)

Table 3. Frequency (per cent) of attending religious services, praying and Reading scriptures, at least once a month over the past year, by level of belief in god among the self-identified no religion group: survey data.

In addition, a small number of the no religion group said they probably or definitely belonged to a religious group in their area (N = 76, 4.4%) or a worldwide religious community (N = 69, 4%). These rates compare with those of 48.7% (N = 3595) and 40.3% (N = 2935), respectively, for those with self-identified religious identities. It is possible that this may reflect ethno-cultural affiliations, rather than religious ones, but this theory would require further investigation.

The presence of religion in the lives of the self-identified no religion group was further demonstrated by comments made by members of the qualitative sample. For many, this was reflected in attending a place of worship, or Sunday School, or some other religious service such as a wedding or a funeral, to accompany or please friends and family. Some had been baptised or christened into the Christian faith, but at a time when they had been too young to have fully developed their own religious views. Many participants said that they enjoyed learning about different religions and several were particularly interested in visiting different places of worship. These instances tended to be seen as social, or intellectual, rather than religious events. One female participant said that she had always wanted to get married in church rather than a Register Office because of the ‘wow factor’.

There were, however, other instances where some semblance of religious meaning had been imbued into beliefs or practices, even by those who might have professed themselves to be atheist or at least non-religious. These begin to illustrate the possible meaning behind the findings presented in . Several young people, for example, pointed out how they might turn to prayer if somebody is ill or if they particularly want something to happen, or they might take meaning from religious readings or symbols. The following quotes are illustrative:

There have been a couple of times in my personal life in which I have prayed for some reason or another – mainly for others … And I’ve thought that getting it off your chest by praying, saying something, might help. But it doesn’t if you know what I mean. I have prayed, I have tried. I’ve done what … well not like the Bible has told me to, but what I’ve come to believe that others say that the Bible says to do. And it has had no effect on me, if you know what I mean. (JACOB BLACK: male, atheist, religion not very important)

I think that even if you’re the most non religious person in the world, when somebody passed away you’d like to think that [that they’ve gone to a better place]. So it’s like more of a source of comfort I find. And that’s probably the time in my life when I’ve most thought about religion in like a believing way. (KYLIE: female, no religion, religion not at all important)

[Talking about a quote from Corinthians 1 that is significant for him]: ‘When I was a child I spake as a child and I played with my childish things. But when I was a man I grew up and I put away childish things’. I’m not saying like religion’s helped me or anything, but I’m saying that through that one quote of Corinthians I that I’ve found some meaning for me behind it. (JACOB BLACK: male, atheist, religion not very important)

I have a religious tattoo on my leg. [Mentioned how it represents a metaphor about finding the right pieces in life.] (JIMMY RAMONE: male, atheist, religion important in some ways but not in others)

Even without faith you can take lessons from Christianity and its moral lessons. (SYDNEY: male, no religion, religion not at all important)

This diversity and widespread fluidity suggests that being non-religious does not, in and of itself, convey an automatic and specific identity. The non-religious fit into the typology of religiosity developed by the Youth On Religion project (Madge, Hemming, and Stenson Citation2014) much as do the religious. This divides young people into four categories: strict adherents, flexible adherents, pragmatists and bystanders. As their names suggest, adherents have a strong religious stance upheld either rigidly or more flexibly, pragmatists are open to influence and experience and may accordingly demonstrate change in their religious identity, and bystanders have been and are relatively unaffected by religion. Relating these categories to the non-religious group in our study, and drawing on both quantitative and qualitative findings, we might say that the ‘nones’ who were unable or unwilling to accept any religious perspective fit within the strict adherent category. Those uncertain about their beliefs, who might be influenced one way or the other through their experiences and interactions, could be termed pragmatists, and those growing up without giving much thought to religion would be bystanders. Members of the study sample did not obviously fit within the flexible adherent category.

The development of non-religious identities

According to the young people in our survey, the majority were quite or very similar to their mothers in religious views, whether they identified themselves as religious or non-religious. The effect was stronger for those who gave themselves a religious label, but still 45.9% of the no religion group said their views were very similar and 15.6% said they were quite similar. Only 12.0% and 9.4% said they were very different or quite different, respectively (see ).

Table 4. Similarity to mother in religious views by religious identity: survey data.

Young people within the qualitative sample reinforced the importance of the family as an agent of socialisation in the sphere of religiosity. Almost without exception, they said that their childhood views and experiences of religion and non-religion were derived directly from their families, whether or not they changed their perspectives as they grew older. Most commonly, however, they had not.

Interestingly, and in contrast to other reports (Woodhead Citation2016), the Youth On Religion study found very little difference in the strength of intergenerational continuities for young people with and without a religious identity. Although the study methodology did not allow a distinction to be drawn between atheists and the rest, it would be instructive to be able to test this possibility and evaluate both Woodhead’s (Citation2016) claim that ‘no religion just happens’ as well as Catto and Eccles (Citation2013) suggestion that ‘to become an atheist in Britain today requires a conscious effort’.

Families are of course not the only influence on religious identity and survey participants were asked to indicate all important influences from a given list of family, teachers, friends, religious leaders, scripture, the Internet, TV and radio and science. Respondents could tick all relevant options, and it was notable that those identifying themselves as religious reported a far greater number of different influences than did those in the no religion group. presents the rank order of the possible influences for the two groups separately.

Table 5. Rank order of factors influencing religious views quite a bit or a lot by religious or non-religious identity: survey data.

What stands out from these responses is that although the family is clearly important for the religious ‘nones’, and retains second place, science achieves the top ranked position. The following quotes from the qualitative data provide some explanation.

I’m very passionate about not being a religious believer and very much passionate about a lot of the scientific side. So, for me, being an atheist is a very big thing. (BONO: female, atheist, religion not at all important)

And I believe there is scientific proof for everything … If there was some sort of tiny smidgen of proof that he was real, then I think I would believe in Jesus and religion. (BOBBIE: female, no religion, religion not very important)

And I’ve just always asked questions and nobody’s ever been able to give me an answer. Because I just don’t believe that there could be somebody who’s always been there. I don’t think I can get my head round that. I need answers for everything and I just don’t think religion gives me those answers. (JOANNA: female, no religion, religion not very important)

Religiosity over the life-cycle

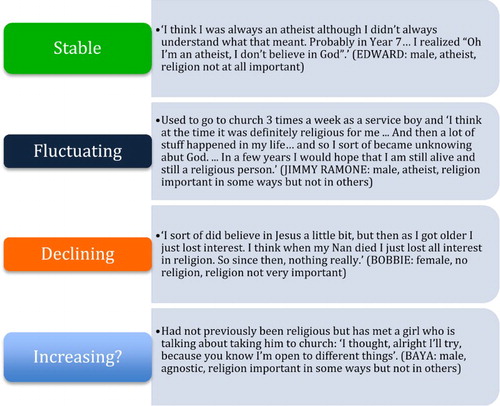

Although research data were collected at a single point in time, interview participants reported on the trajectories of their lives and gave clear indications of both continuity and change. The religious ‘nones’ provided examples of stable and fluctuating non-religious identities as well as instances of change in the direction of both declining and possibly increasing religiosity. presents four cases to demonstrate this diversity.

Figure 2. Stable, fluctuating, declining and increasing religiosity among the religious ‘nones’: discussion group and interview data.

Similarly to the religious members of the Youth On Religion sample, several of the religious ‘nones’ commented on the future and how they would not automatically expect their own children to share their own religiosity. Just as they had chosen their own pathway, so they wished the next generation to be able to do so too.

Despite respecting the fact my parents have given me and my brother total freedom to believe, I think if I had kids I would try to argue more for the scientific reasoning because I don’t agree with religion as it could cause conflict. But, ultimately, if they felt so strongly for a religion I would allow them to explore it. (ROSE: female, no religion, religion not at all important)

With my children I think I would not pressure them into anything. I would like to teach them about the different religions. … I don’t want to choose for my children. ..It is up to them. Whatever makes them happy I guess. (BONO: female, atheist, religion not at all important)

The different life-cycle patterns shown by young people further highlight the inappropriateness of assigning fixed religious (or non-religious) identities. Individual experiences and interactions influence continuities and discontinuities in identity and confirm the conclusion that religious identity is frequently fluid. These findings are more in tune with LeDrew’s (Citation2013) identification of diverse trajectories than Smith’s (Citation2011) concept of a linear trajectory to non-religion.

Conclusions

The findings from this study strongly endorse and elaborate upon the conclusions from other research (Smith and Denton Citation2005; Mason, Singleton, and Webber Citation2007) and contribute to a largely neglected area in youth studies. Crucially, they highlight how young people giving themselves a non-religious label are a very diverse group. They demonstrate how the non-religious are dissimilar in the way they choose to label themselves, in the reasons they give for these labels, their beliefs and religious activities, the factors influencing their religiosity, and the continuities and discontinuities in their religious expression. Fervent atheists are different from those who have largely drifted away from religion but may still have some beliefs. In this sense they mirror the variety of beliefs and practices displayed by those who profess a religious affiliation. This has not previously been empirically demonstrated within a large British sample of young people.

In some sense there is a continuum between the religious and the non-religious with perhaps, as suggested by Cotter (Citation2015), some degree of fluidity as to the labels young people adopt. This is illustrated by the two young people who changed their mind about their identity during interviews. Young people also demonstrate fluidity in their religious identities over the life-cycle, reflecting experiences, relationships and context, again suggesting that a non-religious identity may not be stable and of fixed meaning. It would be interesting to explore these forms of fluidity further. For instance, how many young (and older) people polled days or weeks apart would describe their religious identity in exactly the same way each time?

These findings are also important for the study of youth in illustrating the role of agency, individualisation and liberal individualism in young people’s conscious decisions about personal religiosity. Young religious ‘nones’ have substantive but diverse identities in their own right (Lee Citation2015) and are not simply definable in terms of what they lack compared to those with religious faith (Zuckerman Citation2009). We elaborate further on this point in a separate article exploring non-religious young people’s approach to morality, inter-religious relations and non-religion in wider society (Hemming and Madge in review).

The growth and meaning of a no religion identity is best understood in relation to change at societal, community and individual levels and in the interplay between these levels. The increasing out datedness and irrelevance of the church (Woodhead Citation2016), the decreasing importance of public religion for the religious (Glendinning and Bruce Citation2011), increased secularisation even within traditional Christian families (Brown Citation2009), the growth of science (Dawkins Citation2006), the prevailing emphasis on individual rights and personal agency (James and James Citation2008), and a move from religious ‘obligation’ to chosen patterns of religious ‘consumption’ (Davie Citation2005), are among the factors that seem important. At an individual level, these factors are reflected in an ethos of liberal individualism, the notion that it is up to each person to make their own decisions in life and at the same time to respect the decisions that others make for themselves (Madge, Hemming, and Stenson Citation2014). The changing acceptability of an atheist or secular identity means a greater willingness to tick the ‘no religion’ box in the case of doubts as to whether personal religiosity meets the standards for affiliation to a particular religious group.

Finally, context is a key factor for the development and expression of religiosity. Beyond place in time, and cohort effects (Voas Citation2010), young people in the Youth On Religion study reported fluidity in religious practices that depended on where they were and who they were with (Madge, Hemming, and Stenson Citation2014). For instance, some participants described how they would present themselves differently when with friends or with families and members of their nominal faith (Goffman Citation1959). This is an important finding in relation to the understanding of youth behaviour. It also points to the significance of spatial context. This research was carried out with young people growing up in three very different multi-faith areas. Would comparable investigation in the more ethnically homogeneous locations of Britain lead to similar findings?

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contribution of our research colleagues to the collection of the data referred to in this article. In particular we thank Melania Calestani, Anthony Goodman, Katherine King, Sarah Kingston, Kevin Stenson and Colin Webster.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. All names are anonymised

References

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. 2013. “Losing my religion?” Australian Social Trends, November.

- Bainbridge, W. S. 2005. “Atheism.” Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion 1: 1–24.

- Beck, U., and E. Beck-Gernsheim. 2001. Individualization: Institutionalized Individualism and its Social and Political Consequences. London: Sage.

- Beit-Hallahmi, B. 2007. “Atheists: A Psychological Profile.” In The Cambridge Companion to Atheism, edited by M. Martin, 300–318. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Berger, P. L., and T. Luckmann. 1966. The Social Construction of Reality. Garden City, NY: Doubleday.

- Brown, C. G. 2009. The Death of Christian Britain: Understanding Secularisation 1800–2000. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- Brown, C., and G. Lynch. 2012. “Cultural Perspectives.” In Religion and Change in Modern Britain, edited by L. Woodhead and R. Catto, 10–20. London: Routledge.

- Bullivant, S. 2008. “Research Note: Sociology and the Study of Atheism.” Journal of Contemporary Religion 23 (3): 363–368. doi: 10.1080/13537900802373114

- Catto, R., and J. Eccles. 2013. “(Dis)Believing and Belonging’: Investigating the Narratives of Young British Atheists.” Temenos 49 (1): 37–63.

- Cotter, C. R. 2015. “Without God Yet not Without Nuance; a Qualitative Study of Atheism and Non-religion among Scottish University Students.” In Atheist Identities: Spaces and Social Contexts, edited by L. G. Beaman and S. Tomlins, 171–194. New York: Springer.

- Cragun, R. T., B. Kosmin, A. Keysar, J. H. Hammer, and M. Nielsen. 2012. ‘On the Receiving End: Discrimination toward the Non-religious in the United States’, Journal of Contemporary Religion 27 (1): 105–127. doi: 10.1080/13537903.2012.642741

- Davie, G. 2005. “From Obligation to Consumption: A Framework for Reflection in Northern Europe”. Political Theology 6 (3): 281–301. doi: 10.1558/poth.6.3.281.66128

- Dawkins, R. 2006. The God Delusion. London: Bantam Books.

- Day, A. 2011. Believing in Belonging: Belief and Social Identity in the Modern World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Day, A., G. Vincent, and C. R. Cotter, eds. 2013. Social Identities Between the Sacred and the Secular. Ashgate AHRC/ESRC Religion and Society Series.

- Giddens, A. 1991. Modernity and Self Identity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Glaser, B. G., and A. L. Strauss. 1971. Status Passage: a formal story. Chicago: Aldine-Atherton.

- Glendinning, T., and S. Bruce. 2011. “Privatization or Deprivatization: British Attitudes about the Public Presence of Religion.” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 50 (3): 503–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5906.2011.01582.x

- Goffman, A. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. University of Edinburgh Social Sciences Research Centre. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books edition.

- Hassell, C., and I. Bushfield. 2014. “Increasing Diversity in Emerging non-Religious Communities.” Secularism and Nonreligion 3 (7): 1–9.

- Hemming, P. J. 2017. Childhood, Youth and Non-religion: Towards a Social Research Agenda. Social Compass 34 (1).

- Hemming, P. J., and Madge, N. in review. Young People, Non-religion and the Wider Community: Insights from the Youth on Religion (YOR) Study.

- Hopkins, P., E. Olson, R. Pain, and G. Vincett. 2010. “Mapping Intergenerationalities: The Formation of Youthful Religiosities.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 36 (2): 314–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-5661.2010.00419.x

- James, A., and A. L. James. 2008. Key Concepts in Childhood Studies. London: Sage.

- Kay, W. K., and L. J. Francis. 1996. Drift From the Churches: Attitudes Toward Christianity During Childhood and Adolescence. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- Knott, K. 2013. “The Secular Sacred: In-between or Both/and?” In Social Identities between the Sacred and the Secular, edited by A. Day, G. Vincett, and C. R. Cotter, 145–160. Surrey: Ashgate.

- LeDrew S. 2013. “Discovering Atheism: Heterogeneity in Trajectories to Atheist Identity and Activism.” Sociology of Religion 74 (4): 431–453. doi: 10.1093/socrel/srt014

- Lee, L. 2015. Recognising the Non-Religious: Reimagining the Secular. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lindesmith, A. R., A. L. Strauss, and N. K. Denzin. 1999. Social Psychology. 8th ed. London: Sage.

- Lynch, G. 2012. The Sacred in the Modern World. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Madge, N., Hemming, P. J., and Stenson, K. (2014) Youth on Religion. The Development, Negotiation and Impact of Faith and non-Faith Identity. London: Routledge.

- Mason, M., A. Singleton, and R. Webber. 2007. The Spirit of Generation Y: Young People's Spirituality in a Changing Australia. Mulgrave: John Garratt.

- Merino, S. M. 2012. “Irreligious Socialization? The Adult Preferences of Individuals Raised with no Religion.” Secularism and Nonreligion 1: 1–16. doi: 10.5334/snr.aa

- Mumford, L. 2015. “Living Non-religious Identity in London.” In Atheist Identities: Spaces and Social Contexts, edited by L. G. Beaman and S. Tomlins, 153–170. New York: Springer.

- Putnam, R. D., and D. E. Campbell. 2010. American Grace: How Religion Divides and Unites us. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Smith, J. M. 2011. “Becoming an Atheist in America: Constructing Identity and Meaning From the Rejection of Theism.” Sociology of Religion 72 (2): 215–237. doi: 10.1093/socrel/srq082

- Smith, C., and M. L. Denton. 2005. Soul Searching: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tomlins, S., and L. G. Beaman. 2015. “Introduction.” In Atheist Identities: Spaces and Social Contexts, edited by L. G. Beaman and S. Tomlins, 1–18. New York: Springer.

- Voas, D. 2010. “Explaining Change Over Time in Religious Involvement”. In Religion and Youth, edited by S. Collins-Mayo and P. Dandelion, 25–32. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Voas, D., and S. McAndrew. 2012. “Three Puzzles of non-religion in Britain.” Journal of Contemporary Religion 27 (1): 29–48. doi: 10.1080/13537903.2012.642725

- Wallis, S. 2014. “Ticking ‘no Religion’: A Case Study Amongst ‘Young Nones’.” Diskus 16 (2): 70–87. doi: 10.18792/diskus.v16i2.42

- Woodhead, L. 2016. “Why ‘No Religion’ is the New Religion.” Presentation to British Academy, January 16.

- Ziebertz, H. -G., and W. K. Kay, eds. 2006. Youth in Europe. Vol. 2: an international empirical study about religiosity. Munster: LIT.

- Zimmerman, K. J., J. M. Smith, K. Simonson, and B. W. Myers. 2015. “Familial Relationship Outcomes of Coming Out as an Atheist.” Secularism and Nonreligion 4 (4): 1–16.

- Zuckerman, P. 2007. “Atheism: Contemporary Numbers and Patterns.” In The Cambridge Companion to Atheism, edited by M. Martin, 47–68. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Zuckerman, P. 2009. “Atheism, Secularity, and Well-being: How the Findings of Social Science Counter Negative Stereotypes and Assumptions.” Sociology Compass 3 (6): 949–971. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-9020.2009.00247.x