ABSTRACT

In this paper we discuss how art workshops can be used to examine dimensions of belonging. We draw on our findings of collaborative ethnographic fieldwork with unaccompanied refugee minors in Finland. The practical aim of the art project was to offer a platform for transcultural communication and interaction, and to support mutual understanding and solidarity among the refugee minors and Finnish pupils. The collaborative ethnographic approach gave us an opportunity to meet the young people through working together and be equally active members of the group sharing the same classroom. Theoretically we aim to enlarge the understanding of the sense of belonging and the role of the subjective agency of the unaccompanied minors, including everyday participation. We highlight the practices through which the minors can be supported in an embracing manner in their everyday lives in new host societies.

Introduction

The year 2015 brought a sudden increase in numbers of unaccompanied minors when more than 3 000 claimed asylum in Finland. Before 2015, roughly 150 to 200 unaccompanied refugee minors had arrived in Finland each year. The new social and political situation revealed that unaccompanied refugee minors are exposed to the fragility and limitations of nationally standardised solutions of institutional care, schooling and social services. Refugee minors are also often perceived as victims of their own past, which continues to define their care needs in many institutional settings. Unaccompanied minors end up living in a ‘limbo of waiting’ for several years, and this open-ended waiting may have long-standing effects on their later lives (Kohli and Kaukko Citation2017). Many of them experience loneliness and some suffer from post-traumatic stress or other psychological conditions. These young people have a limited possibility to live like other young people, since they are overwhelmed by the experiences of fleeing from home, journeying and the asylum process in the new host country. Their experiences of uncertainty are further amplified when they meet with institutional mistrust or there is a lack of trustworthy adults in their daily social environment (Kuusisto-Arponen Citation2015, Citation2016a; see also Björklund Citation2015; Herz and Lalander Citation2017; Kaukko and Wernesjö Citation2017; Kohli Citation2011). Whereas new psychosocial interventions are currently being developed to help children and young people with trauma memories (e.g. Peltonen and Punamäki Citation2010), novel ways to deal with the loss and alteration of important social and spatial relations are needed (see also Kuusisto-Arponen Citation2014, Citation2016b).

In the contemporary world, the struggles over inclusion and exclusion of groups of people have increased immensely. Therefore, in this paper, we ask how we could support transcultural subjectivities and solidarities in institutional settings such as school. Further, we illustrate practices through which the unaccompanied minors can be supported in an embracing manner in their new host societies. The embracing manner includes the distribution of hope for the future, which is one of the crucial mechanisms of societies, as the anthropologist Hage (Citation2003) argues. Moreover, he stresses that ‘the kind of affective attachment (worrying or caring) that a society creates among its citizens is intimately connected to its capacity to distribute hope’ (Hage Citation2003, 3). This capability and socio-political willingness of caring in societies has become segregative and conditioned to ‘right’ nationality during the recent years of high-level mobility, whether voluntary or forced. Thus, the affective attachments of many European societies have become dominated by increasing nationalistic rhetoric and strict governing of nationals versus newcomers. This has also rigorously promoted polarisation tendencies, such as segregated housing and education, within societies.

Several NGOs, ad hoc solidarity groups and individual citizens have acted in order to help the refugee and migrant populations in many European countries. Simultaneously, far right movements have gained political influence with their populistic demands for closing borders and deporting asylum-seekers back to their countries of origin. In the post-2015 Europe, these claims are harshly targeted at unaccompanied minors as well, affecting their future life perspectives and opportunities in the new host society (Kuusisto-Arponen and Gilmartin Citation2019). Wimelius et al. (Citation2017, 143–144) argue that for example in Sweden, which is one of the largest recipients of unaccompanied minors in Europe, reception faces challenges such as a lack of contacts between actors, an absence of shared political visions of integration, and a lack of follow-ups and evaluations. The same structural and governing challenges exist in Finland. However, we argue here that in order to promote social integration, it is important to recognise the lived experiences of these minors both at the micro and socio-political levels.

The theoretical aim of this paper is to contribute to the understanding of the centrality of social encounters engendering transcultural belonging. We focus particularly on the encounters that illustrate the negotiations of agency among unaccompanied minors. In this paper, we draw on our experiences and findings of the fieldwork with unaccompanied refugee minors in Finland. The ethnographic fieldwork was conducted in autumn 2016. Methodologically, we ask how art workshops as a data gathering method can be used to address the narrated and embodied dimensions of belonging (on embodied belonging, see also Korjonen-Kuusipuro and Kuusisto-Arponen Citation2012; Kuusisto-Arponen & Savolainen Citation2016). We stress the importance of the collaborative aspect in ethnographic fieldwork: for us, this ‘doing with’ meant that we worked together with the young people who were the subjects of our research. We found this method very fruitful, as it helped to build trust between the researchers and the participants and to open our minds to fresh and often unexpected ideas coming from the participants, and thus move towards more collaborative knowledge-making processes (See e.g. Beck and Maida Citation2013; Bergold and Thomas Citation2012).

Previous research on unaccompanied minors highlights the existential loneliness of unaccompanied minors. For example, the social network these young people have can be limited to the institution where they live (Herz and Lalander Citation2017, 1067). This means that their daily social ties are mainly based on relationships with co-travellers, adult caregivers and several state-related authorities, but not with the wider society. As Herz and Lalander (Citation2017) aptly criticise, even the term ‘unaccompanied minor’ is itself excluding and isolating. Protection that is based on categorising these minors as having no familial ties further reinforces the sense of loneliness (Kuusisto-Arponen and Gilmartin Citation2019). Thus, the resilience of the unaccompanied children needs to be supported via various protective factors (such as a safe environment, possibility to success in education), and with the help of individuals, families and communities. Simultaneously, it is vital to maintain stable and loving ties to home (Nardone and Correa-Velez Citation2016, 3). Therefore, our paper also makes a practical contribution to the field of institutional care: we present ideas to support social belonging facilitated through artistic methods in the school environment that is one of the key pro-social organisations in these minors’ lives.

Approaches to identity, agency and belonging

In this article, we discuss the everyday lives of the unaccompanied minors and the practices of belonging. Basically, human life can be understood as consisting of complex, interconnected spheres, and a self is always culturally and socially embedded and connected to other people (Smart Citation2007 > cited in May Citation2011, 364). Furthermore, for instance Nsamenang (Citation2008, 17–18) describes self-identity as an agentic core of personality, which gives meaning to life and perspective to human efforts. Through identity, individuals see themselves belonging to a distinct culture, place, ethnicity, nationality, gender, or culture. In the case of displacement like forced migration, these socio-spatial connections to culture, people and places alter, meaning that for example refugee minors must form new ties and sites of belonging. One of the biggest hopes of an unaccompanied minor is to create friendships among the peers in their new society. This goal, however, is sometimes very hard to achieve. The difficulty arises from several issues such as a lack of knowledge about and social trust towards foreign-looking young people. Sometimes even adults in the new host society might be suspicious about the motives of these young people (Gustafsson, Fioretosand, and Norström Citation2012; Kaukko and Wernesjö Citation2017). Ni Raghallaigh (Citation2014, 91–92) describes this ‘climate of mistrust’ as one of the key factors hindering the minors from gaining trust in social relations and in society at large. This atmosphere prevails not only in institutional settings such as migration governance but also in daily relationships.

Current research on identities and identifications stresses the need to recognise and accept the existence of multidirectional identities. Critical identity theories have highlighted identification as an ongoing process rather than something stable or fixed (Lähdesmäki et al. Citation2016). Fortier (Citation2000, 2) sees ‘identity as threshold … a location that by definition frames the passage from one space to another’. In the lives of migrant youth, this constant shifting and ambiguity of the identity-making becomes very obvious. Some scholars have discussed ‘migrant identities’ through (trans)formation, (re)construction and negotiation during migration processes (see for example Jackson Citation2014; La Barbera Citation2015; McAreavay Citation2017). Migrants are constantly producing themselves ‘through the combined process of being and becoming’ (Fortier Citation2000, 2), or being in liminal spaces, somewhere ‘in between’ (Huot, Dodson, and Rudman Citation2014; Kaukko and Wernesjö Citation2017). Here in-betweenness refers to the socio-spatial contexts where young migrants have to operate, adjust and re-role themselves on a daily basis, and thus, in-betweenness should not be seen as referring to the existential subjectivity of a human being. Moreover, the belonging of unaccompanied minors is based on translocal realities and transcultural ties of existence where different languages, physical and virtual places, and social contexts all play significant roles (see also Kaukko and Wernesjö Citation2017; Yuval-Davis Citation2006).

The (re-)birth of active agency is crucial for young people to be able to gain an experience of belonging to new societies. Agency refers here to young people’s evolving capacity to act and influence their own life and to be active and participate (Nsamenang Citation2008, 211; Lau Clayton Citation2013). Guo and Dalli (Citation2016, 255) define agency as ‘a discourse which contributes to the processes of construction and constitution of children as social beings’. For them, agency clarifies the dynamics of the various connections between children, their self and others, and the socio-cultural practices around them. This means that actions that aim to support agency are always embedded in situations where desires and needs of children are influenced by their learning resource, which also includes the spaces and people around them. Based on this view, the ‘self’ dimension of agency can be seen closely connected to the socio-cultural environment. In our fieldwork, this meant for example young people’s attempts to adjust to different gender roles in their new host society or aims to understand the roles, rights and responsibilities of children, which all affect the self-dimension of agency. Furthermore, analysing these kinds of factors may require that we look beyond the aspects of identities and focus more on the degree of control young people’s actions can have over their life (See also Ensor and Goździak Citation2010; Rollason Citation2017; Valentine, Sporton, and Nielsen Citation2009).

Earlier research has shown that the unaccompanied minors lack power in the decision-making that concerns them. They are perceived as a group of young people who are constantly seen as victims or passive beneficiaries, even though seeing them as active agents with multiple capabilities and resources would advance their sense of social belonging and integration (Kaukko and Wernesjö Citation2017; Kohli Citation2006). Studies concentrating on belonging quite often study people who are considered vulnerable in terms of distribution of power in society (Lähdesmäki et al. Citation2016, 240). In addition, vulnerability may also be determined from the viewpoint of care. Kuusisto-Arponen and Gilmartin (Citation2019) have defined ‘geographies of care’ as practices and actions of institutional and individual actors who aim to provide protection, support and well-being. This caring may be based on compassionate engagements, but simultaneously it may posit the recipients of care as passive victims (see also Conradson Citation2003; Kuusisto-Arponen and Gilmartin Citation2019). Criticising the ethos of vulnerability and victimising does not mean that these young people would not need care and support.

Even though we speak for active participation and agency of refugee minors, our focus here is not on ‘formal’ participatory practices, such as local youth parliaments or other such organisatory models (on these see e.g. Percy-Smith Citation2010). However, we argue, as Kaukko and Wernesjö (Citation2017) point out, it is also important to understand that formal participation in society may be a challenging practice itself. For refugee minors, too much independence and high expectations at an early age may restrict the willingness to take responsibility later in life (Kaukko and Wernesjö Citation2017; Kuusisto-Arponen and Gilmartin Citation2019). These young people may benefit more from such support mechanisms and practices that recognise the multiple agencies in social encounters. As Kuusisto-Arponen (Citation2016c), Kaukko and Wernesjö (Citation2017) and Valentine, Sporton, and Nielsen (Citation2009) have identified, there is a gap of knowledge on how to support the subjective sense of everyday participation and the belonging of unaccompanied minors in the realm of institutional care, such as school, residential units and youth work.

The meanings of the concept of belonging vary from public-oriented official membership in a community (e.g. citizenship) to an informal subjective feeling of belonging (e.g. a sense of being socially accepted), being ‘in place’ or ‘out of place’. Belonging consists of social locations, subjective identification and emotional attachments to various groups. It also relates to ethical and political value systems through which societies construct ‘us’ and ‘them’ (Cresswell Citation1996; Fortier Citation2000; Valentine, Sporton, and Nielsen Citation2009; Yuval-Davis Citation2006, 199–204). Lähdesmäki et al. (Citation2016, 241) have described the concept as being ‘best understood as an entanglement of multiple and intersecting, affective and material, spatially experienced and socio-politically conditioned relations’. It is notable, that the concept of belonging always requires contextualised definitions because of its situational and cultural relations. According to May (Citation2011, 367), concentrating on belonging allows us to examine the reciprocal influence between self and society. This concept offers a dynamic approach on people as active participants in society. It stresses the enabling role of everyday practices as creative and innovative, but also points to encounters that are controlled and enforce more controlling. Thus, we understand belonging as emotional attachment, which becomes visible in various embodied practices, language and material encounters like works of art (See also Gilmartin and Kuusisto-Arponen Citation2019; Jackson Citation2014; Korjonen-Kuusipuro and Kuusisto-Arponen Citation2012; Korjonen-Kuusipuro and Meriläinen-Hyvärinen Citation2016).

Making Mexican masks together

In autumn 2016, we conducted ethnographic fieldwork in Finland with 14–16-year-old unaccompanied refugee minors and Finnish secondary school pupils. The unaccompanied minors were all young males from Afghanistan and Iraq. Two thirds of the Finnish art class students were females. The number of pupils in the workshops varied from 11 to 23. We participated in five art workshops organised by two experienced visual artists, Finnish Anne Lihavainen and Mexican Rosamaria Bolom, to create traditional Mexican paper masks. All workshops included four phases: a short introductory game, designing, making and painting of a Mexican mask. Participants could design their own mask or work in pairs or small groups. Four workshops were carried out in the secondary school’s art class and one workshop was organised in a family group home, the institution where the unaccompanied minors are housed during the asylum process. Each workshop lasted for four to six hours. The data from the workshops consist of 94 pages of ethnographic field notes, 73 min of videos and approximately 600 photographs.

Utilising a ‘third culture approach’ by introducing traditional Mexican mask making for all pupils was a way to learn about different cultural traditions without connecting it to Finland or the home countries of the migrant youth. The art project offered a platform for transcultural communication and interaction, and for supporting mutual understanding and solidarity among the young people. The unaccompanied minors formed a coherent and solid group right from the beginning of the workshop, because in addition to going to school together, they lived in the same housing unit. The art workshops also aimed at facilitating contacts between the Finnish pupils and the unaccompanied refugee minors who were studying in a preparatory class. These two groups have normally little interaction with each other in classroom situations due to separated teaching arrangements (see also Ramirez and Matthews Citation2008, 86).

For us, the collaborative method meant that we were making masks together with the pupils. Besides that, we worked as helping hands for artists and teachers. This allowed us to be fully present in art making, and not act only as observers. Our disciplinary background as research team was in cultural anthropology, political geography and regional studies, and this naturally guided our gazes in the field. We all had previous experience in ethnographic fieldwork and facilitating workshops, and we also have pedagogical training. In the workshops, the artists were responsible for the artistic visions and group facilitation. All participants were fully aware of our research and had filled in a written consent form before attending the workshop.

Our methodological approach, which we named ‘doing with’, is based on ethnography. Ethnography is understood as a way of knowing and a knowledge-making process in which the personalities of participants and researchers, as well as the choices made during fieldwork and later during analysis and writing, play an important role (Korjonen-Kuusipuro and Meriläinen-Hyvärinen Citation2016, 28). Thus, we wrote down in our field notes both the oral dialogues and detailed reflections of emotions and embodied presences of the young people and ourselves. Both of these descriptions have been used as the empirical data of this paper. For analytical purposes, we used a ‘two-column-tactics’ in our fieldwork diaries and separated general description and reflection. This was useful for two reasons. First, this was done to analytically separate the practice description (observations of what we did) from emotional reflections (personal experiences and reactions). Second, this was done to direct enough focus on the non-verbal, kinaesthetic and embodied knowledge-making of the youth (Emerson, Fretz, and Shaw Citation2001; Kuusisto-Arponen Citation2016c). In addition, our research material includes photographs and videos. One of the greatest benefits of the ‘doing with’ method was that we could overcome many of the language barriers, because artistic methods were based on non-verbal communication and embodiment. In our fieldwork, the relationship between the researchers and the researched was blurred, and we encountered our research partners as knowing subjects. In practice, this meant that we could adopt ideas, topics and views that our research participants presented to us and could modify the course of our research according to these, if necessary (see also Bergold and Thomas Citation2012).

The collaborative approach gave us an opportunity to meet young people through making art together and be equally active members of the group sharing the same classroom. In a way, we became insiders and this ‘seeing from the inside’ considerably strengthened our understanding of young people’s encounters. The fact that we researchers were of different age and sex had a clear effect on the interaction with the youth, also further affecting the knowledge we gained from the field. The advantage of the collaborative methodology was that we had very few expectations beforehand of where the art workshop would lead us, what kind of knowledge we could achieve, and what kinds of results we would harvest. Our aim was also to make the multiple voices of our participants more visible and build on the reciprocity of the knowledge production (Gatt and Ingold Citation2013; Marcus Citation1995). In the collaborative way of doing ethnography, it is necessary that researchers are aware of themselves as instruments of research. During our research, we wrote our reflections down in our field diaries and discussed afterwards for example how gender roles or age affected the way the youth regarded us and also the way we saw various situations and contexts (see also Bergold and Thomas Citation2012).

Our active role in the art process enabled us to build a high level of trust and establish rapport with the youth, in a relatively short time. For the collaborative ethnography to be an analytical method, it is also crucial that the researcher is present, available and interested in young people’s lives and the issues they wish to discuss. This compassionate method also helped the participants to recognise issues they themselves considered important to share with the researchers (see also Herz and Lalander Citation2017, 1063).

Our research engagement was emotionally and ethically demanding. We encountered several situations that showed how burdensome the daily lives of the unaccompanied minors can be and how hard these young try to cope with a new culture. They seemed to need a great deal of care and support, especially when memories from the ceded home surfaced. We also had constant negotiations with ethical issues concerning our research, for example in which social situations we could photograph and how we should use the photos later in research publications. During our fieldwork, there were several moments when we needed to evaluate very quickly how our research might affect young people’s life. The following reflections from the field notes are examples of how we pondered those moments afterwards in our field diaries.

I realise that I am very careful in many situations. For example: I am at ease with the Afghan boys, but I have great difficulties talking to the Finnish girls. I don’t seem to find any common interests to share with them. I would not like to talk only to the Afghan boys, but to all the pupils. (Field diary, reflection 24 October 2016)

I ask Kristiina to take a picture when the boys are painting this text. R is first a little bit aware of the camera, but relaxes again when he notices that Kristiina is photographing only the mask he is making. He does not ask her to stop [photographing]. (Field diary, reflection 24 October 2016)Footnote1

After each workshop day, we tried not to talk to one another about the events and our emotions before all of us had written in our field diaries. When compiling these to a shared document, we often started to speak about our experiences and reflected on how we should adjust our fieldwork for the next workshop meeting. This way we reacted to the knowledge we gained from the field and could focus better on the themes that seemed important to our participants. In the next chapter, we will discuss in more detail how lingual, embodied and material dimensions of belonging appeared in our fieldwork.

Encountering belonging

Language

Language is still often considered a core factor of our identity (Valentine, Sporton, and Nielsen Citation2009), but some researchers, especially in non-western cultures, have shown that developments such as transnational communication, migration and digital communication have created multilingual interactions that may challenge our paradigm of language learning and the importance of languages in communication (e.g. Canagarajah and Wurr Citation2011). In everyday life, language skills are seen as one of the most important factors in social interaction and upholding agency. In the context of contemporary migration governance, this means an emphasis on learning the language of the new host society as part of the integration schemes, whereas the recognition of multilingual encounters is not often supported in institutional settings such as schools.

The unaccompanied minors attending the art workshops had started studying in a preparatory class some six months before our fieldwork. We were told that their Finnish language skills had improved rapidly, and some spoke Finnish rather well during the time of our fieldwork. Learning the basic skills in Finnish did not resolve the problems of social loneliness and isolation, which surfaced several times during the workshops. In our interviews with the principal of the school and the teacher of the preparatory class, they explained that at first the unaccompanied youth were rather isolated in the school, too: they studied in their own classroom and were taken back to their home by bus immediately after school. Gradually, the communication between the Finnish pupils and the unaccompanied minors grew, as some of them had an opportunity to attend integrated classes in some subjects. Informal chatting and conversations were very much encouraged by their own teacher:

The [classroom] door is open and if anyone shows interest, I will ask them to come in and talk to us. […] I told them [the Finnish pupils] to talk to the boy next to them and ask about all the basic stuff, hobbies, birthdays, etc.

During our fieldwork, we observed how interactions between the two groups slowly started to emerge in the art class. The mask project connected the two youth groups, which were usually separated and only knew each other by sight. Therefore, it was especially interesting to follow how and in which situations the communication between these two groups evolved and slowly strengthened. Each workshop meeting began with diverse introductory games based on non-verbal communication so that everyone had a fair opportunity to participate. This made the atmosphere socially acceptable for all pupils.

We noticed, however, that the misinterpretation about a lack of common language also seemed an obstacle for starting the conversation. In the first workshop meeting, one of us researchers asked the Finnish girls whether they had already made friends with these boys. The girls said ‘not really’ because the boys do not yet speak fluent Finnish. They, however, considered talking to them after their Finnish had become more fluent: ‘Maybe in a couple of years’ time the boys of the preparatory class will have learnt Finnish, so that we can more easily chat with them’, they said. Our researcher wrote in her field diary that: ‘I was left with the feeling that the language was the only barrier of communication’ (Field diary, reflection 10 October 2016). This notion is interesting in two ways. First, the Finnish pupils had a very strong assumption about the level of the Finnish language that needs to be there before joint conversation is possible. Second, the girls, however, had no other reason not to communicate with the newcomers. This example clearly indicates why social encounters need to be actively facilitated and encouraged especially in the formal school setting and rather fixed syllabus structure. Studying in the same building is not a guarantee of coming together socially.

In general, the Finnish pupils were quieter than the talkative boys from the preparatory class. In Finland, silence and being all by oneself is considered a typical and normal way of social interaction. Carbaugh and Berry (Citation2006) have even suggested that quietude and silence should in fact be seen as a ‘natural way of being’ and as part of ‘cultural richness’ in Finland. Berry (Citation2011, 400) explains how culture is embedded in something shared for cohering diversity. For him, culture seems to be the taken-for-granted relationship between language, values and social practices. He defines cultural richness as a ‘cultural presence that works in a positive social way’. Therefore, it is important to notice that quietude, in the Finnish context, should not be interpreted as impoliteness, unpredictability or shyness. People unfamiliar with the Finnish culture rarely understand this viewpoint. Especially in Finnish schools, such culture of silence is tied with the idea of discipline and thus promoted as ‘good behaviour’. The Finnish pupils evidently demonstrated this kind of behaviour.

We also observed the multilingual environment these youth lived in: the ways they communicated with each other and with other members of the group, including us. During the fieldwork, we noticed that the unaccompanied minors were taking several language roles in the multilingual environment. Farsi, Arabic, Finnish, Spanish, and English were all spoken during the workshops. Different languages complemented each other in communication and made the social situations easier especially for the refugee participants (see also Canagarajah and Wurr Citation2011, 6). Some of the youth used language in a playful and humorous manner, some of them stayed in the background as others acted as ‘peer translators’. These peer translators played a significant role in the group dynamics enabling more social contacts. Translating was also done through phone applications.

Embodied communication

In our fieldwork, we observed multiple bodily expressions and performative ways of communication. This occurred because Finnish was not yet a very strong language for the unaccompanied minors. In the workshop, unaccompanied minors were often adopting stronger non-verbal and bodily communication, whereas Finnish pupils were more withdrawn, quiet and mostly staying in their places. Unaccompanied minors expressed multiple ways of physical closeness: they used touch, massaged each other, gave hugs to greet each other, and, in general, were physically close to each other. For Finnish youth, this kind of body culture and closeness in the context of school is still less familiar. The next quote from our fieldwork diary clarifies the differences in communication cultures. It also shows how embodied the communication in the workshop was:

At some point, the boys in the back row start to move. One of them already has a mask, which reminds me of a king. ‘Yes, the king’, he says in English, when I am asking ‘Is that a king or what?’ He puts his mask on his face and makes a couple of dance moves towards the table where two Finnish girls are sitting. Both girls flinch when they see him. They reject him by looking at the table and looking past him. One girl is turning her back on him. The boy does not try this anymore and goes back to his friend. He tries to appear as impassive, but he seems confused. He does not see my glance. (Research diary, general description 10 October 2016)

We witnessed a very different situation as well when one of the workshops was held in the boys’ home. A boy, who already spoke some Finnish, was welcoming us loudly in front of the house: ‘Welcome, nice to see you!’ in Finnish. He said this in a very formal, yet slightly humorous way, with a twinkle in his eye. The scene was repeated when a Finnish boy arrived at the house; he approached the Finnish boy and repeated his greeting with a shining smile. We noticed that this smile and act of kindness made an impression on the Finnish boy, who was seemingly pleased about the welcome he received. These kinds of micro-moments in social encounters created trust and crossed many social and cultural boundaries when young people of different backgrounds tried to reach out to one another. For adults to facilitate the communication of young people, it is crucial to recognise such moments and then actively support them. Therefore, every time we noticed these actions, we tried to give feedback to all young people. This was done for example by saying: ‘That was very nicely said’, or ‘That is a good idea, why don’t you do it together?’ These small interventions supported not just talking, but also doing things together.

Both of the examples above show the differences in bodily communication between Finnish pupils and unaccompanied minors. May (Citation2011, 368) and Fortier (Citation2000, 14) stress the sociological notion that a sense of belonging is partly achieved on the basis of knowing unwritten rules and being able to conduct oneself in an ‘acceptable’ manner before others. The first example discussed above clearly shows how the boy with the mask did not know what kind of collective rules there are in a Finnish classroom and how to approach Finnish girls to get feedback on his finished art work. In order to feel belonging, one needs to be accepted within a group (See also Lähdesmäki et al. Citation2016, 240). Both of our examples illustrate how eagerly the boys were looking for friends among their peers. Probyn (Citation1996, 19) suggests that belonging actually captures ‘the desire for some sort of attachment, be it to other people, places, or modes of being’. The micro-moment described above poignantly illustrates how an individual showed a need to belong and to become a member of a group, but was silently rejected.

Based on the examples above, we argue that the moments that open up space for transcultural interactions are extremely important. These moments, supported by adequate guidance and facilitation, enable encounters where social belonging of unaccompanied minors, and other youth as well, can be strengthened in institutional settings.

Material dimensions of belonging

Studies dealing with materiality examine the ways in which human beings are entangled in and dependent on the materiality of the physical world (e.g. Kuusisto-Arponen & Savolainen Citation2016). Lähdesmäki et al. (Citation2016) call these ‘materialised micro-levels of belonging’, which may be food, work or clothing, for example. In our research material, we found several examples of how materiality is connected to the sense of belonging. In the next empirical example, a moment of painting a mask clearly shows the fractures in the sense of belonging and the way in which longing is materialised.

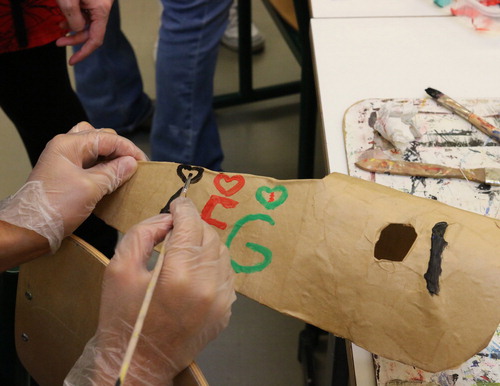

I sit down next to R (…), I ask him, how are you doing? He says that he is tired; he would not like to paint anything. I try to suggest that we could pick some colours together. (…) It is hard for him to start doing something. After a while, his friend A crabs the mask and paints eyebrows. Then R says: ‘Afghanistan. I will write Afghanistan!’ First, he draws on air with a brush. Then he outlines a letter A. He changes colours after every letter. ‘How do I write an F? Is this a G? I will draw a heart as well!’ A (his friend next to him) responds: ‘No, the heart is broken. I will do … blood drops here.’ He crabs a red brush and he crosses out the heart. I ask: ‘Why is the heart broken?’ R says that the heart of A is broken. ‘But I will draw two new ones!’ A does not respond to my question. He looks at me in the eyes, turns away and goes back to his seat. (Research diary, general description 24 October 2016)

Picture 1. Remembering home by drawing the colours of the Afghan flag. (Photo: Kristiina Korjonen-Kuusipuro 2016).

These kinds of sudden appearances of difficult and emotional memories among the unaccompanied minors were common in our fieldwork. Methodologically ‘doing with’ was the key factor here: these moments became possible through allowing space for self-expression, providing safe social space for remembering and by recognising the moments where the mental support of adult facilitators was needed. The episode above was one of the most emotionally thick moments during the entire fieldwork day. Even though the narrative expressions of the boys were rather scarce, the embodiment between them expressed through the memories of home, the boys’ silent invitation for adults to witness this deep longing, and the materiality of remembering, all describe how the sense of belonging is built in social encounters.

Further, we argue that art workshops can be excellent places to observe various social-spatial engagements. Following Goffman’s (Citation1959) idea, we stress that the school class was a kind of social arena (a setting), where pupils took different kinds of roles to step in (into the front stage) or stay at the background (at the backstage). The classroom forms the stage with its desks in clear rows stressing the idea that pupils are supposed to work individually. Even though the workshops were held in the art classroom where communication between the pupils was allowed and even encouraged, the classrooms still created some physical boundaries that partly hindered spontaneous and multilingual working.

When entering the classroom, unaccompanied minors seemed uncertain as to where to sit, what to do or when to do it, despite the fact that there were several adults instructing and guiding them what to do. During the art workshops, they often tried to withdraw from the actual doing. Because there were few opportunities to hide in the classroom, they had to invent other ways to escape from the social setting. Sometimes they escaped into a virtual world, started playing mobile games or listening to music. Helping hands were needed to guide them from this social backstage back to schoolwork, and even then the adult facilitation was not always enough as the next citation shows:

There was this one Afghan boy who spent almost the whole class chopping paper into very small pieces with scissors. He was also playing the Clash of Clans mobile game. He took part in discussions, but did not really do anything else. After a while his teacher said to him: ‘Come on, you have to do at least something!’ The boy did not react in any way, just continued to play his game. The teacher was trying to get him to work, but he just said, ‘this is very important.’ I tried to talk to the boy about the game and told him that it was a Finnish game. By saying this I got a contact with him. After a while, I said more loudly, ‘now we will do eyebrows for your friend’s mask together’. The boy replied reluctantly, ‘ok’. (Field diary, general description 10 October 2016)

School classrooms in Finland are spaces designed for individual learning, which also makes them physically specific kinds of structures that support this pedagogical goal. Even though the culture of learning has changed from individual to more collective, learning spaces have often remained the same. This was also very evident in our workshops. Finnish pupils were used to working in this type of classroom setting: almost all of them took their roles unquestionably, working hard and following the guidelines of the instructing artists and teachers. We argue that in creating a supportive atmosphere for social interaction, the spaces of coming together really matter, in institutional settings in particular. School in itself is a huge front stage with very controlled, and thus very few, opportunities for backstage sociality. This might be a real challenge or at least a restrictive factor in supporting transcultural exchange in schools.

In comparison, when one of the workshops was organised in the group home of the unaccompanied minors, the whole social setting and the idea of backstage/ front stage changed. The Finnish youth were the invited guests, and the unaccompanied minors were the hosts. In this environment, the communication between the two groups started to evolve. Various activities encouraged the young to be truly together: for example they played volleyball, ate together and played introductory games or presented their mask in the front of entire group at the end of the workshop.

I feel that this workshop was the most important of all art workshops. We got to see the boys’ world: how they live and spend their time. Furthermore, we got a chance to bring something new and exciting into their normal everyday lives. In this workshop their characters became more visible than in the normal classroom. For the first time I identified big differences in their personalities, habitus, and behaviour. (Field diary, reflection 6 November 2016)

Conclusions

In this article we have focused on negotiations of belonging among the unaccompanied refugee minors and discussed how they can be supported and facilitated in social encounters with the Finnish youth. Drawing on the fieldwork in five art workshops, we have pinpointed practices through which the minors can be supported in an embracing manner in their everyday lives in their new host society. Furthermore, we have emphasised the ambivalence and ambiguity of the identity work of the unaccompanied minors. Whereas these minors are actively engaged in their identity work, this process occurs in an environment where cultural norms, aspirations and contexts are new and confusing.

We found out that even though language is still seen as an important marker of identities (e.g. Valentine, Sporton, and Nielsen Citation2009), in the multilingual environment the unaccompanied minors took different language roles and tended to use non-verbal and embodied communication more intensively. We argue that their ability to use multiple languages should be recognised, acknowledged and encouraged also in the school environment in order to support a sense of belonging and integration. We also conclude that the unaccompanied minors manage their social involvement as a way to develop a sense of self-determination and re-gain subjective agency. Presence in supportive and socially accepting daily environments and regular social encounters with peers are crucial for unaccompanied minors and their self-determination. In addition, various kinds of materialities support belonging. The unaccompanied minors live in parallel worlds – in the memories of the old home country and in the new host society – at the same time. Also, the virtual world seemed to be a third reality, which sometimes even connected these two concrete worlds. These spheres of belonging need to be recognised and valued also in institutional care environments.

The collaborative mask workshops were a success in many ways. We heard and saw many voices, languages and opinions woven together. While at first these voices were rather weak, they were nevertheless seeds of some kind of deeper understanding of similarity between young people from different backgrounds i.e. the core of transcultural being. It must be remembered that this kind of collaboration demands time to develop. In order to support lasting communication and strengthen the experience of belonging, we need practices that develop relationships between young people and trustworthy adults, such as the artists in these workshops. Working together in an open atmosphere of art teaching is one of the potential ways to create these valuable relationships.

Hage (Citation2003) stresses the value of hope and the importance of citizens’ rights. Although these minors were not yet citizens of Finland, they were already living among us and for that reason should be guaranteed a part of the society’s distribution of care and hopeFootnote3. In our workshops, we saw plenty of glimpses of hope. These moments were sometimes very brief: bright eyes and happy faces that could sometimes be identified only afterwards from photographs taken in workshops. Sometimes finding courage to meet a new person created overwhelming happiness. Thus, we argue that it is extremely important to analyse these multilevel capacities of society to produce hope not only for its citizens, but to all people. This is the key to developing social practices that recognise and support the transcultural belonging of unaccompanied minors in everyday life contexts.

Acknowledgements

Ethics Committee of the Tampere region has approved the research plan, statement 49/2016.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The quotations are translated by authors. The names in the quotes have been changed.

2 Percy-Smith (Citation2010, 119–120) has criticised the narrow focus of participation. He has argued that we should focus more on the multiplicity of ways which especially young people act, contribute to and realise their own sense of agency in everyday life contexts instead of having an emphasis on formal participation, such as institutionalised public decision-making processes.

3 In a conversation with Dimitris Papadopoulos (Hage and Papadoupoulos Citation2004), Ghassan Hage stresses inclusion and exclusion in a nation state context: ‘Thus there will always be a question of who is included in the distributional network: i.e. who perceive themselves as receiving some kind of hope from it: who is in and who is out.’ In our view this is also true within everyday life contexts.

References

- Beck, Sam, and Carl A. Maida. 2013. “Introduction: Towards Engaged Anthropology.” In Toward Engaged Anthropology, edited by Sam Beck, and Carl A. Maida, 1–14. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Bergold, Jarg, and Stefan Thomas. 2012. “Participatory Research Methods: A Methodological Approach in Motion.” FORUM Qualitative Social Research 13 (1): 1–21.

- Berry, Michael. 2011. “Communicating the Cultural Richness of Finnish Hiljaisuus (Silence).” CercleS 1 (2): 399–422.

- Björklund, Krister. 2015. Unaccompanied Refugee Minors in Finland: Challenges and Good Practices in a Nordic context. Turku: Institute of Migration C26.

- Canagarajah, A. Suresh, and Adrian J. Wurr. 2011. “Multilingual Communication and Language Acquisition: New Research Directions.” The Reading Matrix 11 (1): 1–15.

- Carbaugh, Donal, and Michael Berry. 2006. “Coding Personhood through Cultural Terms and Practices - Silence and Quietude as a Finnish “Natural Way of Being”.” Journal of Language and Social Psychology 25 (3): 1–18.

- Conradson, David. 2003. “Geographies of Care: Spaces, Practices, Experiences.” Social and Cultural Geography 4 (4): 451–454.

- Cresswell, Tim. 1996. In Place/Out of Place: Geography, Ideology and Transgression. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Emerson, Robert M., Rachel I. Fretz, and Linda L. Shaw. 2001. “Participant Observation and Fieldnotes.” In Handbook of Ethnography, edited by Paul Atkinson, Amanda Coffey, Sara Delamont, John Lofland, and Lyn Lofland, 352–368. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Ennis, Gretchen Marie, and Jane Tonkin. 2017. “‘It’s Like Exercise for Your Soul’: How Participation in Youth Arts Activities Contributes to Young People’s Wellbeing.” Journal of Youth Studies, doi:10.1080/13676261.2017.1380302.

- Ensor, Marisa O., and Elźbieta M. Goździak. 2010. “Introduction: Migrant Children at the Crossroads.” In Children and Migration: At the Crossroads of Resilience and Vulnerability, edited by Marisa O. Ensor, and Elźbieta M. Goździak, 1–13. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave & Macmillan.

- Fortier, Anne-Marie. 2000. Migrant Belongings: Memory, Space, Identity. Oxford: Berg.

- Gatt, Caroline, and Tim Ingold. 2013. “From Description to Correspondence: Anthropology in Real Time.” In Design Anthropology: Theory and Practice, edited by Wendy Gunn, Ton Ton Otto, and Rachel Charlotte Smith, 139–158. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Gilmartin, Mary, and Anna-Kaisa Kuusisto-Arponen. 2019. Borders and Bodies: Siting Critical Geographies of Migration. Handbook of Critical Geographies of Migration. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Goffman, Erwin. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York: Anchor Books.

- Guo, Karen, and Carmen Dalli. 2016. “Belonging as a Force of Agency: An Exploration Of Immigrant Children’s Everyday Life In Early Childhood Settings.” Global Studies of Childhood 6 (3): 254–267.

- Gustafsson, Kristina, Ingrid Fioretosand and Eva Norström. 2012. Between Empowerment and Powerlessness: Separated minors in Sweden. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development 136: 65–77.

- Hage, Ghassan. 2003. Against Paranoid Nationalism: Searching for Hope in a Shrinking Society. Annandale, NSW: Pluto Press.

- Hage, Ghassan, and Dimitris Papadopoulos. 2004. “Ghassan Hage in Conversation with Dimitris Papadopoulos: Migration, Hope and the Making of Subjectivity in Transnational Capitalism.” International Journal for Critical Psychology 12: 95–117.

- Herz, Marcus, and Philip Lalander. 2017. “Being alone or Becoming Lonely? The Complexity of Portraying ‘Unaccompanied Children’ as being alone in Sweden.” Journal of Youth Studies 20 (8): 1062–1076.

- Huot, S., B. Dodson, and D. L. Rudman. 2014. “Negotiating Belonging Following Migration: Exploring The Relationship Between Place and Identity in Francophone Minority Communities.” The Canadian Geographer / Le Géographe canadien 58 (3): 329–340.

- Jackson, Lucy. 2014. “The Multiple Voices of Belonging: Migrant Identities and Community Practice in South Wales.” Environment and Planning A 46: 1666–1681.

- Kaukko, Mervi, and Ulrika Wernesjö. 2017. “Belonging and Participation in Liminality: Unaccompanied Children in Finland and Sweden.” Childhood 24 (1): 7–20.

- Kohli, S. Ravi. 2006. “The Sound of Silence: Listening to What Unaccompanied Asylum-seeking Children Say and Do Not Say.” British Journal of Social Work 36: 707–721.

- Kohli, S. Ravi. 2011. “Working to Ensure Safety, Belonging and Success for Unaccompanied Asylum-seeking Children.” Child Abuse Review 20: 311–323.

- Kohli, S. Ravi, and Mervi Kaukko. 2017. “The Management of Time and Waiting by Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Girls in Finland.” Journal of Refugee Studies. doi:10.1093/jrs/fex040.

- Korjonen-Kuusipuro, Kristiina, and Anna-Kaisa Kuusisto-Arponen. 2012. Emotional Silences: The Rituals of Remembering the Finnish Karelia. In Painful Pasts and Useful Memories. Remembering and Forgetting in Europe. Conference Paper Series No. 5, edited by B. Törnquist-Plewa and N. Bernsand, 109–126. Lund: Lund University.

- Korjonen-Kuusipuro, Kristiina, and Anneli Meriläinen-Hyvärinen. 2016. Living with the Loss: Emotional Ties to Place in the Vuoksi and Talvivaara regions in Finland. Emotion, Space and Society 20: 27–34.

- Kuusisto-Arponen, Anna-Kaisa. 2014. “Silence, Childhood Displacement, and Spatial Belonging.” An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies 13 (3): 434–441.

- Kuusisto-Arponen, Anna-Kaisa. 2015. Ajatuksia myötätunnosta ja kivusta. Terra 127 (2): 83–89.

- Kuusisto-Arponen, Anna-Kaisa. 2016a. “Perheettömiksi suojellut: yksin tulleiden alaikäisten oikeus perheeseen.” In Perheenyhdistäminen, edited by Fingerroos, et al., 89–109. Tampere: Vastapaino.

- Kuusisto-Arponen, Anna-Kaisa. 2016b. “Relating Self, Place and Memory: Spatial Trauma among the British and Finnish War Children.” In Geographies of Children and Young People: Conflict, Violence and Peace, edited by Harker, et al., 307–325. Singapore: Springer.

- Kuusisto-Arponen, Anna-Kaisa. 2016c. “Myötätunnon politiikka ja tutkimusetiikka Suomeen yksin tulleiden maahanmuuttajanuorten arjen tutkimisessa.” Sosiologia 53 (4): 396–415.

- Kuusisto-Arponen, Anna-Kaisa, and Mary Gilmartin. 2019. Embodied Migration and the Geographies of Care: the Worlds of Unaccompanied Refugee Minors. Handbook on Critical Geographies of Migration. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Kuusisto-Arponen, Anna-Kaisa, and Ulla Savolainen. 2016. “The Interplay of Memory and Matter: Narratives of Former Finnish Karelian Child Evacuees.” Oral History 44 (2): 59–68.

- La Barbera, MariaCaterina. 2015. “Identity and Migration: An Introduction.” In Identity and Migration in Europe: Multidisciplinary Perspectives. International Perspectives on Migration. Vol. 13., edited by MariaCaterina La Barbera, 1–13. Cham: Springer.

- Lähdesmäki, Tuuli, Tuija Saresma, Kaisa Hiltunen, Saara Jäntti, Nina Sääskilahti, Antti Vallius, and Kaisa Ahvenjärvi. 2016. “Fluidity and Flexibility of ‘‘Belonging’’: Uses of the Concept in Contemporary Research.” Acta Sociologica 59 (3): 233–247.

- Lau Clayton, Carmen. 2013. “British Chinese Children: Agency and Action.” The Journal of Early Adolescence 33 (2): 161–183.

- Marcus, George. 1995. “Ethnography in/of the World System: The Emergence of Multi-Sited Ethnography.” Annual Review of Anthropology 24: 95–117.

- May, Vanessa. 2011. Self, Belonging and Social Change. Sociology 45 (3): 363–378.

- McAreavay, Ruth. 2017. “Migrant Identities in a New Immigration Destination: Revealing the Limitations of the ‘Hard working’ Migrant Identity.” Population, Space and Place 24 (6). doi:10.1002/psp.2044.

- Nardone, Marianna, and Ignacio Correa-Velez. 2016. “Unpredictability, Invisibility, and Vulnerability: Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Minors’ Journeys to Australia.” Journal of Refugee Studies 29 (3): 295–314.

- Ni Raghallaigh, Muireann. 2014. “The Causes of Mistrust among Asylum Seekers and Refugees: Insights From Research With Unaccompanied Asylum-Seeking Minors Living in the Republic of Ireland.” Journal of Refugee Studies 27 (1): 82–100.

- Nsamenang, A. Bame. 2008. Constructing Cultural Identity in Families. In Developing Positive Identities: Diversity and Young Children, edited by L. Brooker and M. Woodhead, 17–32. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Peltonen, Kirsi, and Raija-Leena Punamäki. 2010. “Preventive Interventions among Children Exposed to Trauma of Armed Conflict: A Literature Review.” Aggressive Behavior 36: 95–116.

- Percy-Smith, Barry. 2010. “ Councils, Consultations and Community: Rethinking the Spaces for Children and Young People’s Participation.” Children’s Geographies 8 (2): 107–122.

- Probyn, Elspeth. 1996. Outside Belongings. London: Routledge.

- Ramirez, Marcela, and Julie Matthews. 2008. “Living in the Now: Young People from Refugee Backgrounds Pursuing Respect, Risk And Fun.” Journal of Youth Studies 11 (1): 83–92.

- Rollason, Will. 2017. “Youth, Presence and Agency: The Case of Kigali’s Motari.” Journal of Youth Studies 20 (10): 1277–1294.

- Smart, Carol. 2007. Personal Life: New Directions in Sociological Thinking. Cambridge: Polity.

- Valentine, Gill, Deborah Sporton, and Katrine Bang Nielsen. 2009. “Identities and Belonging: A Study of Somali Refugee and Asylum Seekers Living in the UK and Denmark.” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 27: 234–250.

- Wimelius, Malin, Malin Erikson, Joakim Isaksson, and Mehdi Ghazinour. 2017. “Swedish Reception of Unaccompanied Refugee Children – Promoting Integration?” Journal of International Migration and Integration 18: 143–157.

- Yuval-Davis, Nira. 2006. “Belonging and the Politics of Belonging.” Patterns of Prejudice 40 (3): 197–214.