ABSTRACT

Across many advanced economies, changing housing dynamics have destabilized traditional adulthood transitions. This article examines how such transformations, especially in the aftermath of the economic crisis, affect fundamental societal expectations and aspirations surrounding tenure choices and home leaving. Through a series of discussion groups and interviews among young adults in Spain – a salient context of embedded homeownership culture – the study reveals how the crisis has undermined life-course transitions and upended discourses surrounding tenure norms. Homeownership has transformed from a dominant symbol of stability and security to one of dispossession and financial risk. Conversely, where pre-crisis discourses dismissed rental, the tenure is portrayed as providing more security in the face of necessary flexibility. Our research reveals that, although traditional ‘homeownership culture’ has not disappeared from the collective imaginary and appears nuanced by social class, it has become increasingly detached from leaving the parental home. The paper exposes the extent to which dominant housing discourses may be upended even within the context of a particularly embedded Southern European homeowner society. We contend that when housing dynamics are coupled with underlying transformations in aspirations and norms, there may be significant societal outcomes.

1. Introduction

Leaving the family home and establishing an independent household are intrinsically linked with housing options. Recent studies have shown fundamental shifts in tenure patterns across advanced economies which have in many ways destabilized traditional adulthood transitions. Spain provides a salient case where changing tenure dynamics have been experienced with particular intensity, especially in the housing outcomes of the recent Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Spain has had one of the highest homeownership rates of Western Europe, and until recently, a clear majority of young adults left the parental home directly for homeownership. This article reveals, however, how substantial changes related to the ongoing economic crisis and outcomes in the housing sector have undermined young Spanish life-course transitions and upended discourses surrounding tenure norms.

Statistical data on Spain reveal recent shifts in residential behaviour, especially in terms of young people's declining entry to homeownership (Módenes and López-Colas Citation2014) Added to this, a limited number of qualitative studies have uncovered important changes to social imaginaries surrounding young adult pathways (Alonso, Fernández, and Ibáñez Citation2011; Aramburu Citation2015; Valls-Fonayet Citation2015). However, research focused on the crucial role of housing within such imaginaries has been understudied. In this paper, we argue for a recognition of the centrality of housing through analyzing fundamental changes in social discourses on tenure and residential independence.

There is clear evidence that the economic crisis is transforming young adults’ life-courses. We contend it is essential to not simply look at whether decisions change for economic or material reasons; rather, it is crucial to understand how such economic transformations affect underlying societal expectations and aspirations, such as those surrounding tenure choices in home leaving. In this paper, beyond direct material and economic outcomes of the crisis, we investigate associated transformations in social imaginaries and further explore to what extent these changes may be engrained in ways that condition future decisions beyond the ongoing crisis.

We begin the paper by situating Spain within the European context. The varying meanings of housing tenures are explored across Europe, with a focus on both the development of a ‘culture of homeownership’ that dominates in Spain, other homeowner societies, as well as the housing impacts of the Global Financial Crisis. We subsequently outline the Spanish study and its data and methods. The results focus on two key aspects: the consequences of the crisis as reflected in discourses on housing tenure, as well as broader transformations in the social imaginaries surrounding life course expectations and the role of social class in nuancing these perspectives. The paper exposes the intensity of Spain’s shift from a homeowner society to life course expectations increasingly refocused on rental housing. These outcomes provide a crucial understanding of contemporary transformations in housing pathways and associated social imaginaries, processes reflected to varying extents across many advanced economies.

1.1. Housing tenure and the culture of homeownership

When young people leave their parental home and transition to an independent household, they must choose among different housing tenures. This choice is the result of a complex decision-making process that is subject to various constraints: derived from specificities of the housing market, such as housing availability and affordability (Lennartz, Arundel, and Ronald Citation2016), availability of individual resources (economic and otherwise), as well as influenced by cultural aspects relating to young people's preferences and expectations, in turn, embedded in the socially assigned value of each tenure.

Countries have been commonly grouped according to the type of welfare state they represent alongside the role of housing within them (Albertini and Kohli Citation2013; Arundel and Ronald Citation2016). Spain is conventionally classified as part of the Southern European welfare regime group, which also includes Italy, Portugal and Greece. These countries are characterized by a strong role of the family in the welfare mix and, regarding housing, high shares of homeownership and parental co-residence (Mulder et al. Citation2015). The higher rate of homeowners – a longstanding feature that has been associated with the Spanish ‘culture of homeownership’ – serves to explain many residential mobility-related phenomena. For example, homeownership norms are (partially) responsible for the late age of home-leaving (Gil Citation2002), the dispersion of populations towards cheaper suburban areas and lower general residential mobility when compared to other countries (Módenes and López-Colás Citation2004).

This preference for homeownership is not, however, a feature exclusive to Spain with an expansive international literature on the social value attributed to homeownership. In many contexts, homeownership is linked to a set of values and aspirations for those who can access it imbued with notions of being better citizens (Dipasqual and Glaeser Citation1999), ‘winners’ on the housing market (Vassenden Citation2014) and constituting a source of security and identity (Saunders Citation1990) – what Giddens conceives of as a form of ‘ontological security’ (Giddens Citation1991; Clapham Citation2011). Such values linked to homeownership have been associated with an embedded ideology of homeownership (Ronald Citation2008), promulgated across many countries, especially over the second half of the past century (Kemeny Citation1981; Citation1995). Spain was no exception, attaining very high homeownership rates and its own strong ‘culture of homeownership,’ alongside especially other Southern European countries such as Italy or Portugal (Azevedo, López-Colás, and Módenes Citation2016).

However, over the past decade, traditional homeownership norms in many contexts have increasingly been undermined. Many countries have seen a shift towards increasing shares of private rental among young people, while their housing trajectories have become increasingly unstable and chaotic (Hochstenbach and Boterman Citation2015; Lennartz, Arundel, and Ronald Citation2016). This recent rise in rent among young people has garnered much attention in both public discourse and in the literature, especially considering what had been a generalized trend in increasing homeownership across advanced economies in the previous decades (Schwartz and Seabrooke Citation2008; Arundel and Ronald Citation2016). As a result, concepts have been popularized in recent years such as ‘generation rent’ (Mckee Citation2012; Hoolachan, Mackee, and Mihaela Citation2016) – alluding to the spread of rental as a longer-term tenure among young people – alongside ‘failure to launch’ households (Mykyta Citation2012), ‘boomerang kids’ (Kaplan Citation2009), or ‘yo-yo transitions’ (Forrest and Yip Citation2012). These reflect significant changes in the residential trajectories of young people, marked by delayed home-leaving, re-entries to the parental home and increased housing precarity (Arundel and Ronald Citation2016; Arundel and Lennartz Citation2017).

While much literature has focused on the UK, Spain provides an especially salient case where homeownership has been particularly entrenched and normalized but where the boom and bust cycle of the crisis has had some of the strongest impacts on housing pathways. In the following two sections, we focus on the Spanish case, paying particular attention to the evolution of the housing market and discourses surrounding tenure. We first trace the development of Spain’s culture of homeownership, followed by a look at how the crisis seems to have given birth to a new phase, marking a crucial break from previous housing norms.

1.2. The rise and decline of homeownership in Spain

The dominance of homeownership has not always been a characteristic of the Spanish housing market. Around the mid-Twentieth Century, private rental was still a normal option and was the clear majority tenure within Spanish cities (Módenes and López-Colas Citation2014). In fact, even until 1950, the rental share surpassed homeownership nationally (Echávez and Andújar Citation2014). In order to understand why Spain is today a country of homeowners, we must understand the evolution of the housing market and the specific social and political discourses surrounding this topic. According to Duque and Susino (Citation2016), this evolution can be divided into three stages, each characterized by a corresponding housing problem: (1) housing scarcity, (2) high prices, and (3) dispossession.

The first stage began in the mid-Twentieth Century and ended around the 1970s. After overcoming the years of downturn following the Civil War, the return to economic growth brought a rural exodus that caused a serious problem of housing scarcity, alongside overcrowding and substandard dwellings. In order to deal with these issues, the 1961 National Housing Plan was enacted with the focus on promoting the purchase of newly built housing (Duque and Susino Citation2016). This marked the starting point for an exceptional predominance of homeownership in Spain. From the 1960s onwards, the rate of homeowners rose steadily. Over these years, renting became relegated to those who couldn't afford to purchase a house, while only considered a voluntary option for very specific life-course moments or social groups, such as professionals requiring high labour mobility (Duque and Susino Citation2016). By the 1990s, homeownership was not only a symbolic marker of a ‘successful lifestyle package’ but rather a widespread reality across every social class (García Citation2010). So much so that a 1991 national survey showed that the rate of homeownership for working-class households was even higher than that of professionals (Susino Citation2003).

Homeownership’s dominance was further reinforced in the decade preceding the GFC which saw the housing market enter a period of peak expansion (Módenes and López-Colás Citation2004). Throughout these years, ownership was privileged by several factors: mortgage loans were easy and readily accessible with low interest rates and long repayment periods (García Citation2010), tax deduction policies were provided on first home purchases (Leal Citation2004), and a generalized perception of never-ending growth enabled and encouraged a large part of the population to get loans (Fernández and Aalbers Citation2016). As a result – and reflecting similar trends in several other countries (Aalbers Citation2008) – a seeming consumer credit euphoria took hold with steadily mounting debts fuelled by the belief that property assets would always be worth more than their liabilities (Castells, Caraca, and Cardoso Citation2013). The demand for housing and associated mortgages was further fuelled by a demographic bulge entering adulthood and increased immigration (Módenes and López-Colas Citation2014). As a result, the rise in prices was so meteoric that, while in 1998 a young person needed 32% of their salary for a house at market price, by 2006, this was up to 80% (Gentile Citation2013). Nonetheless, rental remained a minority tenure, the demand for which primarily came from immigrant populations (Bayona and López-Gay Citation2011).

During this cycle of expansion, the perceived housing dilemma shifted from being one of scarcity to one of restricted access owing to rising prices, particularly for young entrants (Duque and Susino Citation2016). By 2007, following more than half a century of continued growth, the share of homeownership had reached 80.1% (Survey of Family Budgets Citation2007). That same year, however, also marked the start of an unfolding economic crisis which saw the collapse of labour and housing markets, sending deep shockwaves through the very foundations of an entrenched culture – and ideology – of homeownership.

At the time of the bubble burst, the Spanish housing stock supply was vastly overbuilt, which led to a drastic and rapid fall in prices (Gentile Citation2013). Simultaneously, access to housing was complicated by tightened credit requirements and worsening employment conditions for many (Echávez and Andújar Citation2014; Salvà-Mut, Thomás-Vanrell, and Quintana-Murci Citation2016). In turn, the high level of debt in loans acquired before the crisis caused mortgage defaults and a rise in evictions (García-Lamarca and Kaika Citation2016). The crisis and the sharp fall in house purchasing and prices, suddenly dispelled the widespread notion that property assets would always be worth more than their incurred debts (Castells, Caraca, and Cardoso Citation2013). While only a minority of foreclosures involved homeowners in their primary residence and absolute numbers still remained relatively low (Foreclosure statistics Citation2014), the rise from previously negligible levels and the highly publicized nature of eviction stories brought a sense of serious crisis to the public imagination. Citizen concern about this issue is reflected in the famous civic movement known as ‘15M’ in 2011 that placed this problem at the centre of their activism along with the demands of the PAH lobby (Platform of Mortgage Affected). However the evictions did not become a fully dominating issue until the end of 2012, when the story of two suicides catapulted it as a major topic in the media and across the social and political agenda (see Chavero Citation2014).

These dynamics of declining property values gave rise to a new stage where the threat of dispossession characterized the dominant housing dilemma. This threat manifested itself in the fear of being unable meet mortgage payments, the risk of losing one’s investment and still being in debt, and underlying all of this, a fear of losing one's home with all its associated emotional weight (Duque and Susino Citation2016). Of course, such housing market changes were happening among the backdrop of labour market deterioration following the GFC which saw dramatic declines in employment especially among young adults and rising levels of job insecurity (OECD Citation2018). Together, the economic and social outcomes of the crisis in Spain provoked a historic tenure shift: a decline in homeownership and a concomitant increase in the rental share, most intensely among young people (Gentile Citation2013; Lennartz, Arundel, and Ronald Citation2016). While absolute tenure shares for the full population declined seemingly modestly by a few percentage points following the crisis (Housing Census Citation1950–2011), this represented nonetheless a dramatic reversal given what had been a long-term period of continued growth. When considering only young adults, declines were stark. Based on our own calculations from the microdata of the Survey of Family Budgets, we are able to calculate tenure shifts among young adults aged 18–29 who live independently. Looking at this group, we see dramatic decreases in homeownership from 52% in 2007 to 29% in 2016 with a concomitant increase in rental from 38% to 53%. Such results corroborate similar trends measured for a wider age group of young adults by Bosh and López-Oller (Citation2017). More recent statistics only point to a continuing shift towards rental (CBRE Citation2016).

Despite such great upheavals in the housing market, there are few empirical studies that deal with its effects on young adult’s discourses and imaginaries. While important shifts in social discourses have been identified, existing research has neglected housing – a fundamental dimension of life-course decisions and central to the economic crisis and its outcomes. In this paper, we propose to focus squarely on changing discourses among young adults surrounding housing. In the face of apparent historic tenure shifts, we tackle an essential question: to what extent are we seeing an abandonment of Spain’s entrenched ‘culture of homeownership’ and to what extent can such dynamics be seen as merely a temporary consequence of the economic crisis? Analyzing changing discourses of young adults themselves helps to understand not only contemporary housing pathways, but also provides a glimpse into future trends to the extent that their perspectives and expectations will guide behaviours in the mid and long-term. We contend that when housing dynamics are coupled with underlying transformations in aspirations and norms, there may be significant consequences on societal outcomes – from patterns of residential mobility, to shaping new socio-economic divisions in asset accumulation or across urban space.

2. Materials and methods

The research takes a qualitative approach in order to investigate how the economic crisis has affected discourses of young adults. Two data sets are compared: the first one gathered in the pre-crisis years of economic boom (2007), the second one collected in the aftermath of the GFC (2014/15). Making use of primary data from both before and after the crisis provides a valuable diachronic perspective, a rare feature when it comes to qualitative studies (Flick Citation2015).

Both studies were designed and interpreted in line with sociological discourse analysis, taking as a reference the Qualitative School of Madrid (see Martín-Criado Citation1997; Conde Citation2009). This framework understands social discourses as a reflection of the conditions in which they are produced, both on the micro level – group or interview dynamics – and on the macro level relating to their social and historical context (Conde Citation2009).Footnote1 The 2007 study involved discussion groups overseen by one of the authors. These focused on uncovering discourses surrounding housing among young adults living in urban areas across the Andalusia region. We have followed an intentional sampling strategy, reflecting the objectives of the research. The sampling was based on the following criteria: socio-economic status (SES), living arrangement (independent or living in the parental home), gender, and city of residence (see ). The SES was derived on the basis of parents’ educational level and employment category. Subsequently, within each group of different SES level, a variety of employment categories was chosen on the individual level. Thus, for example, Low SES groups include young people whose parents are Low SES but who are in different work situations.

Table 1. Discussion group sampling 2007.

The more recent study, over 2014/15, traced the residential discourses of young people in a period of economic crisis. The sampling made use of the same criteria as the 2007 study, though focusing on the metropolitan area of Granada. Although it was not meant as a systematic replication, it was designed to provide possibilities for comparison. The sampling for the discussion groups kept similar criteria of SES and living arrangement. Gender was omitted, since it had not been found to be of particular relevance (Hernández and Susino Citation2008), while variation on area of residence was added (see ). For the groups living independently, we ensured that the individuals had made that transition during the crisis era (after 2008). Added to this, eleven in-depth interviews were carried out (all in 2015) with people whose profiles were harder to access using discussion groups: particularly lower SES Spanish and immigrant young adults.

Table 2. Discussion group sampling 2014/15.

Discussion groups each consisted of 6-9 people. We decided for homogeneity within groups in terms of living arrangement, SES and parental background while selecting variation based on age, gender, occupational status and area of residence. Such an approach both reflects representativeness while favouring the exchange of ideas (Ibañez Citation1979). Participants had not previously met each other or the moderator, nor did they know the topic of discussion beforehand. The dynamics of the discussion groups and interviews were flexible. In all groups, a common prompt was used (Conde Citation2009) by posing a very similar initial question related to leaving the parental home and housing. Although there was a list of topics to be covered, spontaneity and flow were fostered without a strict set of a priori questions.

Discussion groups and interviews alike were recorded and transcribed. We followed the suggestions of Conde (Citation2009) who focuses on analysing narrative configurations. For this approach, one must take a global approach that can connect the meanings of discourses to the context in which they are produced and the goals of the research. The design of the pre- and post-crisis groups allowed for a diachronic comparison of discourses on housing tenures. This was facilitated by the more generalizable nature of the topic, with a common pattern of opinions across Spain (Aramburu Citation2015).

3. Results

3.1. The economic crisis and discourses on tenure and risk perception

The first critical results of our analyses were in the respondents’ treatment of tenure in home-leaving discourses. Both discussion group sessions and interviews tended to trigger similar responses. Following the general prompt on housing and leaving the parental home, comments quickly alluded to job insecurity and general difficulties for young people in home-leaving and accessing housing. However, a remarkable feature was noted in all groups: the casual omission of tenure itself in these discussions.

Respondents in 2007, speaking about difficulties in accessing housing, implicitly discussed homeownership. Revealingly, the group members didn't feel the need to specify tenure: home-leaving and residential independence, for them, automatically meant purchasing a house. A parallel practice of omitting any direct reference to tenure was found in the 2014 groups, however, in the new context, the assumption became that they were talking about renting. The two following quotes, one from 2007, the other from 2014, are illustrative of this drastic shift. They are both taken from the very first moments of the group discussions. While the first conversation goes straight into discussing house prices and mortgages, the second is tacitly about renting, without anyone in either cases mentioning other possibilities.

M. So, where would you start if you had to talk about housing?

4. We could start by discussing prices, ‘cause they're through the roof. You can't find a newly built flat for less than thirty million [pesetas: about €180,000].

[Several others agree]

4. Still, it's never going to be less than fifteen million [€90,000], and that means €500 a month in installments for thirty years. You spend almost your entire life … I'm thirty, so if I get into, say, a thirty-five-year mortgage, that's sixty-five years old, that's when I'd finish paying. And at sixty-five I don't know if I will …

9. You're leaving the mortgage for your grandchildren to pay!

(G02: Independent, lower SES, 2007).

M. Well, what I wanted to ask you is: could you tell me something about whether you've ever thought about leaving your parents’ home … ?

6. I think all of us have, but the thing is actual possibilities, and … no, it's not possible.

5. There's no way to find the means, job-wise, and I have a job, but it's not enough … it's not enough to live independently, because you have to pay your rent and pay for your own stuff. You can't do it all.

6. And that's the one with a job … [laughter].

2. Same for me …

(G08: Non-independent, lower SES, 2014).

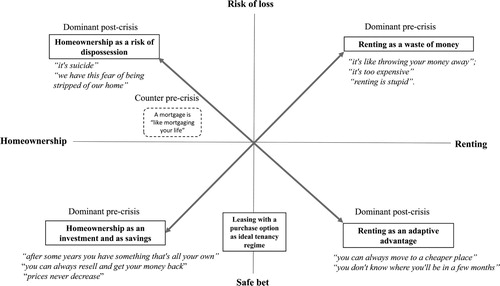

In examining such a dramatic change in implicit tenure expectations over the two periods, we must understand how their discourses are framed by the transformation of life prospects brought about by the crisis. In analyzing the discussions, it was possible to identify dominant, legitimized discourses and their supporting arguments in both the pre- and post-crisis contexts. These are summarized visually in . The horizontal axis displays the homeownership-rent dichotomy, whereas the vertical axis represents contrasting logics related to perceived notions of ‘risk of loss’ versus ideas of a ‘safe bet’ that appear to underpin the dramatic shift in dominant discourses.

The lower left quadrant shows the discourse that deems homeownership to be the safest bet. In this discourse, ownership via a mortgageFootnote2 is synonymous with ‘savings and investment.’ This would be the discourse most resembling the ideology of homeownership and its association with the pursuit of economic and ontological security. It was the dominant discourseFootnote3 in the 2007 discussion groups, in which homeownership was presented as the most sensible option. There were two related underlying premises which seemed indisputable: ‘you can always resell and get your money back’ and ‘the prices of real estate never decrease,’ both based on trust in the housing market. This is the same discourse that Jones et al. (Citation2007) found in their qualitative study of eight European countries. The associated discourse links renting to a risk of wasting money, characterized by quotes from the respondents, such as: ‘it's a waste of money,’ ‘it's too expensive,’ or even ‘renting is stupid,’ – illustrated in the following exchange:

M: [Interrupts and changes subject] What about renting? Because you just talk about buying …

4. I don't think about it.

I think renting, all in all, is a waste of money.

It's too expensive.

7. Renting costs the same as a mortgage nowadays.

It's a bottomless moneybox.”

(G03: Non independent, lower SES, 2007).

Such discourses don’t mean, however, that there was absolute agreement among pre-crisis groups about these points. To the contrary: in every group, there arose some extent of counter-arguments. In 2007, this was represented by a discourse that saw entering a mortgage as reckless (portrayed in with a dashed outline). We consider these positions to be counter-discourses for two reasons: on the one hand, these were the comments and arguments that created tension and division in the groups and, on the other, they tended to be limited to discursive positions among some respondents with a higher level of education – those feeling the most authorized to present divergent opinions (Bourdieu Citation1985). This counter discourse present in 2007 suggested that mortgaged homeownership is ‘like mortgaging your life,’ proposing that it can reduce quality of life (working long hours, sometimes moonlighting) and purchasing power (a large share going to pay the loan), alongside some risks related to variable interest rates. An additional point that was already discernible in some counter discourses in 2007 was that ‘we Spaniards were fooling ourselves’ because ‘the house wasn't yours, but the bank's,’ with a risk of losing it if you couldn't pay the installments. It must be stressed, however, that such arguments were swiftly and firmly rebuked in the 2007 groups: the risk was considered minimal because, again, the dominant discourse was that: ‘you can always sell’ and ‘prices never decease.’

The economic crisis, however, radically disrupted these lines of argument. The crisis saw plummeting prices and a near freezing of the housing market, together with a rise in the numbers and visibility of evictions. All discussion about homeownership as an inherently safe bet suddenly seemed meaningless and it became incoherent to defend such perspectives. Given such a reversal, post-crisis responses often sounded like an attempt to overcome a collective mistake made by Spanish society (‘we have learned’), with the previous discourse labelled irrational, childish, outdated, and discredited.

In many ways, the dominant discourse in 2014/15 is the opposite of 2007. Homeownership (via mortgage) is presented as dangerous, imbued with a risk of losing one’s house – a risk of dispossession in Duque and Susino's (Citation2016) words. The publicized experience of evictions makes such arguments virtually undisputed as a collective new reality and reproduced in young adults’ discourses. Indeed, such associations are so generalized in the post-crisis period that respondents don’t feel the need to explain the reasons for not wanting to purchase property. When pressed, they answer with a tone that indicates the obviousness of their position. Such discourses resemble closely the ‘fear of credit’ narrative that Alonso, Fernández, and Ibáñez (Citation2011) found in their qualitative study of consumption and the economic crisis in Spain. These arguments further echo Beck’s notion of a ‘risk society’ increasingly preoccupied with the risks of a world shifting towards greater insecurity in the face of economic restructuring (Beck Citation1992, Citation2000).

In the post-crisis discourses, the ‘safe bet’ option flipped to renting. Rental is presented as the cautious decision, mostly owing to the flexibility provided by the tenure, which is viewed as key in adapting to the unstable life prospects the young are facing: ‘you can move out if your salary gets cut,’ ‘it allows you to adapt to an unstable future.’ In other words, it is presented as a means of adapting to the broader labour insecurities of new dimensions of the risk society (see Beck Citation1992, Citation2000) where insecurity in labour markets reflect in both ability but also changing priorities across other dimensions such as housing. The following quote sums up such changing perceptions of security and risk, criticism towards previous homeownership rationales, and the assertion that renting is the safest in the face of instability:

6. What's clear is there's been a change in perception, the ease of it [entering homeownership] made it safe then, and now it makes it risky.

8. That's true, it's a risk now.

6. But there's no doubt that easy movement is what renting allows you, you can change plans at any point and just leave.

(G09: Independent, upper-middle SES, 2014)

3.2. Social class and discourses on tenure and life-course transitions

Since leaving the parental home is an integral part of becoming an adult, we must understand how residential discourses are linked to the aspirations and decisions that surround life-course transitions towards independence and new family formation. Here we further reveal that such discourses, especially in relation to housing tenure, are often nuanced in terms of socioeconomic status.

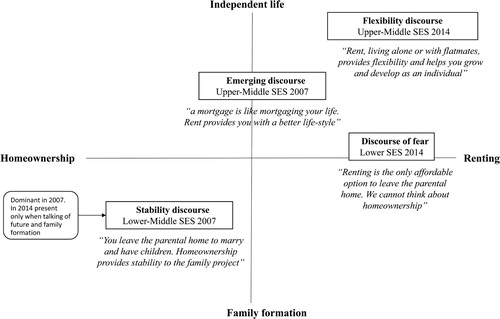

summarizes how different groups are positioned in the social imaginary around discussed life-course transitions following home-leaving. Adding to the previous analysis that focused on the pre- and post-crisis oppositions surrounding homeownership versus rent, we have included a vertical axis representing life-course decisions of new family formation versus independence. This second dimension, as we shall explain below, is more closely tied to class distinction.

Firstly, we find, in the lower left quadrant, what we have called the stability discourse, emphasizing a connection between homeownership and family formation. This appears dominant pre-crisis reflecting an ‘ideal discourse of homeownership culture.’ The stability discourse is found most prominently among the lower-middle SES groups of 2007, where homeownership is considered necessary as a way to bring stability towards family formation.

On the other hand, a counter discourse was also present in the 2007 sample reflecting a ‘new,’ or ‘emerging,’ discursive trend. The emerging discourse was brought forth by certain upper-middle SES members with a higher level of education. This emerging discourse presented renting as beneficial towards an independent life (as a step before family formation) with certain lifestyle advantages in ‘growing’ professionally or personally. Renting was thus seen as granting more mobility and individual freedom – in the Spanish context, allowing either lower monthly costs or being able to live in more prime locations for roughly similar costs of purchasing in the periphery. These discussions were often tied to a more general discourse of a quality of life pursuit. Here are some examples of this pre-crisis counter – or emerging – discourse:

4. To get into a mortgage for the rest of your life, not being able to do anything but pay for a house, I just think … it seems depressing! To me, anyway. I mean, the fact that …

It's just that the quality of life you're bound to have if you're going to be paying a mortgage …

4. You're reducing it.

… you won't be able to do anything else in your life other than paying a mortgage and it just seems sad to me.

No dinners, no travelling …

(G05: Non-independent, upper-middle SES, 2007).

While in 2007, such a discourse about the advantages of renting belonged only to certain sectors of the upper-middle SES, the discussions from the post-crisis respondents reveals a drastic shift towards being more widespread. Among the 2014/15 upper-middle SES groups, this discourse has clearly become dominant. Here, we call it the flexibility discourse, representing the primary justification offered in terms of the advantage of renting. Rental is seen as allowing flexible relocation if new job or study prospects arise or if the respondents simply want change.

M. Have you thought about owning a house?

Oh, no, sir, I haven't.

5. Renting.

I don't even know where I'm going to be next year.

I wouldn't get into buying a house, unless I could pay it all in once … but I don't want any trouble.

At most, I'd think about saving some money, you know, 7000 or 8000 euros, and buying a piece of land in Asturias, that's the most I'd do … […]

2. I don't want any ties, because my boyfriend is looking for a job and he'll probably have to leave, and me too, later, I'll leave, because I do want to see new things.

(G09: Independent, upper-middle SES, 2014)

Lastly, a fourth position was apparent in what we call the discourse of fear which appeared in 2014/15 particularly among lower-middle SES groups. While this discourse was also coupled with discussions about the advantages of rental and the flexibility that it provides, rental here was not portrayed as a genuinely ‘desirable’ option, but rather as ‘the only possible one.’ This group – most impacted by worsening employment prospects (Salvà-Mut, Thomás-Vanrell, and Quintana-Murci Citation2016) – emphasized that buying was not even a consideration as they both saw the market as too risky and could not afford homeownership. This fourth discourse truly reflected a ‘crisis of homeownership’ imaginary, where it no longer provided security. Instead, homeownership was viewed as an immense risk – even presented metaphorically as ‘suicide.’ Such discourses were most clearly influenced by the crisis and associated fears of dispossession:

M. There's one thing about what you're telling me that's caught my attention: whenever you talk about getting a flat, or going to a flat or whatever, you're always talking about renting …

Several: Yes, always.

3. I mean, buying isn't even an option.

4. It’s just that buying doesn't even enter your mind.

5. Buying is suicide (laughter).

You either win the lottery, and you don't need to get into a mortgage, or no way, man.

(G07. Non-independent, lower-middle SES, 2014).

Despite the ‘U-turn’ in the tenure focus of dominant discourses our findings, in keeping with the analysis by Aramburu (Citation2015), do not indicate the complete abandonment of the ‘culture of homeownership’. Interestingly, Young adults in the study often noted that homeownership continues to be the best option in the future – specifically for family formation. Indeed, when asked what their ‘ideal’ house would be like, they all opt for homeownership – albeit one that has already been paid for and is mortgage-free. Additionally, preferences for homeownership arise more easily in interviews than in the group discussions. When post-crisis groups were asked their opinion on entering homeownership, they often responded with collective laughter and were quick to offer broad dismissals characterizing the option as ‘insane’ and undesirable. On the other hand, during one-on-one interviews, lower SES respondents were likely to present a discourse of ‘I would like to but I can't afford it.’ This may reflect differences between the techniques: groups tend to bring out the shared social discourse and be more shaped by structural censorship (Bourdieu Citation1985, 110), while interviews are better suited to delve into individual values and strategies. While no longer ascribing to them, respondents nonetheless portray such homeownership norms as remaining prevalent among ‘others’ – often as discourses of their parents and older siblings. They thus propose counter-arguments to what they see as still ingrained in the public imagination. In this sense, it appears that in Spain, the influence of the SES of the parents on the tenure outcome is not as clear as has been observed in other countries due to the widespread propensity towards owner-occupation across all social classes in Spain (see Henretta Citation1984). The observable differences in the discourses between SES seem to be differentiated more in terms of other aspirations and expectations related to the formation of the family and professional career.

Looking at discourses on tenure and life-course transitions, it appears change has come at different speeds. The drastic shift in the dominant legitimized discourses with regards to housing tenures may not always align with the speed of transformations in conceiving young people's pathways to adulthood. The former seems to have been brought on swiftly as a result of the traumatic effects of the crisis. The latter, on the other hand, seems rooted in an already ongoing but gradual change in ideas surrounding home-leaving, independence and family formation. Discourses on flexible pathways to leaving the parental home were spearheaded before the crisis by the upper-middle class and subsequently, at least partly, appropriated by those of lower SES. However, one needs to be cautious on whether such changing discourses represent a real embracing of new flexible life-courses – and a distancing from the link between home-leaving and family formation typical of Spain and other Southern European countries – or whether such narratives of ‘flexibility’ represent more a strategy to legitimise growing precarity in the face of rising job insecurity, family and relationship instability and difficulties in access to housing. In other words, in the face of constrained homeownership, such associations between renting and flexibility can also be a useful discourse wherein undervalued options are transformed in the social imaginary to being the most rational.

4. Discussion

Through a series of discussion groups and in-depth interviews, the article examined changing discourses on tenure and life-course transitions among young adults in Spain. The results, first and foremost, indicate a fundamental shift in discourses over the years following the financial crisis. Homeownership has seemingly transformed from a dominant symbol of stability and security to one of danger associated with dispossession and financial risk. Conversely, where traditional pre-crisis discourses dismissed rental, in recent years, the tenure is instead portrayed as a symbol for security in the face of necessary flexibility. This change is a way to avoid, minimize or channel contemporary risks. In this sense, the economic crisis could have functioned as a trigger for a reflective and adaptive process manifested in housing choices in the face of an increasingly precarious labour market (Beck Citation1992, Citation2000).

We argue that this drastic shift in discourses on housing is likely the result of two primary factors: on the one hand, it is difficult to maintain a discourse in favour of ownership after the traumatic outcomes of the crisis and, on the other hand, such changed discourses help legitimize new situations of precariousness facing young people. Particularly among lower SES respondents, these discourses appear as a way of ‘desiring’ the inevitable, legitimizing less traditional and more precarious pathways. Here, we agree with Mckee et al. (Citation2017) who speaks of a ‘fallacy of choice’ regarding tenure, because, if this were a simple choice, all tenures would have to be equally affordable and accessible.

A superficial analysis may conclude only that ‘homeownership culture’ is in crisis and young people now prefer renting. However, our nuanced analysis shows that the discourses on the advantages and disadvantages of ownership versus rent did not appear out of thin air. Both discourses are present before and after the economic crisis whether as dominant discourses, counter discourses, or as atrributed to others not present in the groups (e.g. parent’s discourse). In our study, traditional ‘homeownership culture’ has not disappeared from the collective imaginary, but it has become detached from leaving the parental home. While property continues to be linked to family life, it ceases to be an indispensable requirement but is reserved for a future – postponed – life-course transition. Homeownership ideals still manifested themselves in references to broader societal norms and in the discourses of lower-middle SES groups. Conversely, discourses linking property with risk and support for rental flexibility were already present in the pre-crisis period (Hernández and Susino Citation2008), however as a counter discourse among certain high-middle SES sectors. What is remarkable, nonetheless, is how the latter supplanted entrenched homeownership culture as the dominant discourse.

Nonetheless, while nuanced through evolving societal norms, the significance of the change cannot be ignored. The crisis and its effects on the housing market have led to a transformation in the dynamics of legitimacy regarding tenure. Flexibility has become a legitimate reason to opt for rental when leaving the parental home. This in the pre-crisis context was unthinkable. These arguments are part of what Mills (Citation1963) called ‘vocabularies of motives,’ that is, a series of legitimate and socially shared arguments that are used to explain and make sense of our actions. Crucially, Mills (Citation1963) emphasizes that the fact a practice becomes legitimate makes its appearance more likely. In our study we find discourse adapted to the prescriptions of a neoliberal form of governance, which prioritizes flexibility, delaying the dream of ownership (Aramburu Citation2015). In other words, such changing tenure discourses have a multitude of real consequences. Changing attitudes towards tenure impact housing markets and social dynamics. These may manifest themselves in many ways across both ‘social space,’ as well as the configuration of cities themselves. For example, the intrinsic temporality of rental may increase aggregate levels of residential mobility. New housing market dynamics and tenure preferences could promote stronger orientation towards urban centres. More broadly, a discursive and practiced shift away from (or delay of) homeownership among certain groups has potentially important implications towards unequal patterns of wealth accumulation in the long-run (Arundel Citation2017). Lastly, the analysis also emphasizes the importance of how specific cultural, economic and housing contexts frame discourses surrounding tenure and life-course transitions.

Nonetheless, limitations of this study need to be taken into account. First, our results are limited to the evolution of dominant social discourses between two pre- and post-crisis periods. The main data production technique, the discussion group, and the design of the sample does not allow for interpretations regarding individual strategies, nor how personal characteristics such as employment status or differences in household composition and couple formation influence emancipatory decisions. The limitations of the data do not allow us to deal with certain further topics that are very present in the discourses of young people, such as the formation of preferences based on parental background and the role that family support can play in residential decisions. Second, it is important to highlight the geographical and temporal limitations. While the subject of tenure is a generalizable topic, with a common pattern of opinions across Spain and especially among Andalusian cities, it is possible that the results would vary in the largest cities. On the other hand, the discourses that we find in our 2014–15 groups could be expected to shift in situations where rental affordability worsens dramatically in contrast to mortgage purchasing costs thereby encouraging some return to property orientation. While there is evidence recently of more sharply rising rental costs in the major cities of Madrid and Barcelona, this is indeed still associated with a continued demand for rental among young people (CBRE Report Citation2016). Additional research is needed across further individual dimensions of labour market and parental resources as well as within the specific markets where rental has become costlier, to contrast the strength and permanence of these developing housing discourses.

Even with these limitations, the Spanish case provides valuable considerations for other contexts, especially as many European countries have faced similar declining entry to homeownership in the post-crisis era (Lennartz, Arundel, and Ronald Citation2016). Above all, the paper exposes the extent to which dominant housing discourses may be upended even within the context of a particularly embedded homeownership culture. We contend that uncovering changing discourses surrounding housing tenure gives an important understanding of both current transformations among young people’s housing pathways as well as a potential glimpse into future motivations and aspirations.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Nayla Fuster http://orcid.org/0000-0002-5874-2467

Rowan Arundel http://orcid.org/0000-0003-2518-2923

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Qualitative School of Madrid is a methodological approach that analyzes language as a social discourse. That is, rather than seeing discourse as information where words trace phenomena, it tries to understand how discourses shape social reality. Following this approach the technique used is discussion groups rather than focus groups (Ruiz Citation2017).

2 It is important to note that, unless explicitly stated otherwise, both the authors of this paper and the young people in their discourses always refer to acquiring a mortgage when discussing homeownership (as opposed to paying the entire price upfront).

3 When we say ‘dominant discourses’ we mean those that are widely accepted in a group. A dominant discourse does not imply that all individuals share the same opinions, but rather that there is a set of arguments that are more socially acceptable than most others (Martín-Criado Citation1997).

4 The strategy of distancing involves attributing one's own arguments to someone or something else, on the assumption that the group would deem these arguments unworthy and insufficient – for example, ‘the TV says … ’, ‘some people believe that … ,’ and so forth (Martín-Criado Citation2014).

5 Discourse productions refers not just to social, economic or historic context, but all factors that may mark discourses, including research design and prioritizing certain groups over others.

References

- Aalbers, M. 2008. “The Financialization of Home and the Mortgage Market Crisis.” Competition & Change 12 (2): 148–166.

- Albertini, M., and M. Kohli. 2013. “The Generational Contract in the Family: An Analysis of Transfer Regimes in Europe.” European Sociological Review 29 (4): 828–840. doi: 10.1093/esr/jcs061

- Alonso, L. E., C. Fernández, and R. Ibáñez. 2011. “Del consumismo a la culpabilidad: en torno a los efectos disciplinarios de la crisis económica.” Política y Sociedad 48 (2): 353–379.

- Aramburu, M. 2015. “Rental as a Taste of Freedom: The Decline of Home Ownership Amongst Working-Class Youth in Spain During Times of Crisis.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 39 (6): 1172–1190. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12218

- Arundel, R. 2017. “Equity Inequity: Housing Wealth Inequality, Inter and Intra-Generational Divergences, and the Rise of Private Landlordism.” Housing, Theory and Society 34 (2): 176–200. doi: 10.1080/14036096.2017.1284154

- Arundel, R., and C. Lennartz. 2017. “Returning to the Parental Home: Boomerang Moves of Younger Adults and the Welfare Regime Context.” Journal of European Social Policy 27 (3): 276–294. doi: 10.1177/0958928716684315

- Arundel, R., and R. Ronald. 2016. “Parental co-Residence, Shared Living and Emerging Adulthood in Europe: Semi-Dependent Housing Across Welfare Regime and Housing System Contexts.” Journal of Youth Studies 19 (7): 885–905. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2015.1112884

- Azevedo, A., J. López-Colás and J.A. Módenes. 2016. “Home Ownership in Southern European Countries: Similarities and Differences." Portuguese Journal of Social Science 15(2): 275-298. doi: 10.1386/pjss.15.2.275_1

- Bayona, J., and A. López-Gay. 2011. “Concentración, segregación y movilidad residencial de los extranjeros en Barcelona.” Documents d'Anàlisi Geogràfica 57 (3): 381–412. doi: 10.5565/rev/dag.234

- Beck, U. 1992. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. New Delhi: Sage.

- Beck, U. 2000. What is Globalization. Cambridge: PolityPress.

- Bosh, J., and J. López-Oller. 2017. El impacto de la crisis en los patrones de movilidad residencial de las personas jóvenes en España. Madrid: Centro Reina Sofía sobre Adolescencia y Juventud.

- Bourdieu, P. 1985. ¿Qué significa hablar? Economía de los intercambios lingüísticos. Madrid: Akal.

- Castells, M., J. Caraca, and G. Cardoso. 2013. Después de la crisis. Translated by D. Fernández Bobrovski. Madrid: Alianza.

- CBRE (Commercial Real Estate Services). 2016. “Claves del mercado y el sector residencial en España”. Accesed September 5, 2017 http://www.cbre.es/es_es/research/informes_especificos/Opinion_content/Opinion_leftcol/residencial.pdf.

- Chavero, P. 2014. “Los desahucios en la prensa española: distintos relatos sobre los asuntos públicos.” Cuadernos de Información y Comunicación 19: 271–284.

- Clapham, D. 2011. “I Wouldn’t Start From Here: Some Reflections on the Analysis of Housing Markets.” Housing, Theory and Society 28 (3): 288–291. doi: 10.1080/14036096.2011.599181

- Conde, F. 2009. Análisis sociológico del sistema de discursos. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.

- Dipasqual, D., and E. Glaeser. 1999. “Incentives and Social Capital: are Home Owners Better Citizens?” Journal of Urban Economics 45 (2): 354–384. doi: 10.1006/juec.1998.2098

- Duque, R., and J. Susino. 2016. “La ciudad como problema, los problemas de la ciudad.” In Marcos de análisis de los problemas sociales. Una mirada desde la Sociología, edited by A. Trinidad, and M. Sánchez-Martínez, 107–124. Madrid: Catarata.

- Echávez, A., and A. Andújar. 2014. “Acceso a la vivienda y emancipación residencial de los jóvenes españoles en un contexto de crisis.” Paper presented at XIV Congreso Nacional de Población, Sevilla, September10-12.

- Fernández, R., and M. B. Aalbers. 2016. “Financialization and Housing: Between Globalization and Varieties of Capitalism.” Competition and Change 20 (2): 71–88. doi: 10.1177/1024529415623916

- Flick, U. 2015. El diseño de Investigación Cualitativa. Madrid: Morata.

- Foreclosure Statistics. 2014. INE Digital Repository. Accessed October 10, 2017). http://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736176993&menu=ultiDatos&idp=1254735576757.

- Forrest, R., and N. Yip. 2012. Housing Young People. London: Routledge.

- García, M. 2010. “The Breakdown of the Spanish Urban Growth Model: Social and Territorial Effects of the Global Crisis.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 34 (4): 967–980. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.01015.x

- García-Lamarca, M., and M. Kaika. 2016. “Mortgaged Lives: the Biopolitics of Debt and Housing Financialisation.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 41 (3): 313–327. doi: 10.1111/tran.12126

- Gentile, A. 2013. Emancipación juvenil en tiempos de crisis. Un diagnóstico para impulsar la inserción laboral y la transición residencial. Madrid: Fundación Alternativas.

- Giddens, A. 1991. The Consequences of Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Gil, E. 2002. “Emancipación tardía y estrategia familiar: el caso de los hijos que ni se casan ni se van de casa.” Revista de Estudios de Juventud 58 (2): 1–9.

- Henretta, J. 1984. “Parental Status and Child’s Home Ownership.” American Sociological Review 49 (1): 131–140. doi: 10.2307/2095562

- Hernández, H., and J. Susino. 2008. Juventud y vivienda. Un análisis cualitativo de las percepciones de los jóvenes andaluces frente a la emancipación. Sevilla: Comisiones Obreras de Andalucía.

- Hochstenbach, C., and W. Boterman. 2015. “Navigating the Field of Housing: Housing Pathways of Young People in Amsterdam.” Journal of Housing and the Built Environment 30 (2): 257–274. doi: 10.1007/s10901-014-9405-6

- Hoolachan, J. K., T. Mackee, and Moore S. Mihaela. 2016. “‘Generation Rent’ and the Ability to ‘Settle Down’: Economic and Geographical Variation in Young People’s Housing Transitions.” Journal of Youth Studies 20 (1): 63–78. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2016.1184241

- Housing Census. 1950–2011. INE Digital Repository. Accessed October 3, 2017. http://www.ine.es/censos2011_datos/cen11_datos_inicio.htm.

- Ibañez, J. 1979. Más allá de la sociología. El grupo de discusión: teoría y práctica. Madrid: Siglo XXI.

- Jones, A., M. Elsinga, D. Quilgars, and J. Toussaint. 2007. “Home Owners’ Perceptions of and Responses to Risk.” European Journal of Housing Policy 7 (2): 129–150. doi: 10.1080/14616710701308539

- Kaplan, G. 2009. “Boomerang Kids: Labor Market Dynamics and Moving Back Home. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis.” Working Paper 675.

- Kemeny, J. 1981. The Myth of Home Ownership: Public Versus Private Choices in Housing Tenure. London: Routledge.

- Kemeny, J. 1995. From Public Housing to the Social Market. London: Routledge.

- Leal, J. 2004. “La política de vivienda en España.” Documentación Social 138: 63–80.

- Lennartz, C., R. Arundel, and R. Ronald. 2016. “Younger Adults and Homeownership in Europe Through the Global Financial Crisis.” Population, Space and Place 22 (8): 823–835. doi: 10.1002/psp.1961

- Martín-Criado, E. 1997. “El grupo de discusión como situación social.” Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas 79: 81–112. doi: 10.2307/40184009

- Martín-Criado, E. 2014. “Inconsistencias y ambivalencias. Teoría de la acción y análisis de discurso.” Revista Internacional de Sociología 72 (1): 115–138. doi: 10.3989/ris.2012.07.24

- Mckee, K. 2012. “Young People, Homeownership and Future Welfare.” Housing Studies 27 (6): 853–862. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2012.714463

- Mckee, K. T., Mooore, A., Soaita, and J. Crawford. 2017. “‘Generation Rent’ and the Fallacy of Choice.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 41 (2): 318–333. doi: 10.1111/1468-2427.12445

- Mills, C. W. 1963. ”Power, Politics and People: the Collected Essays of Charles Wright Mills” edited by L. Horowitz. London: Oxford University Press.

- Módenes, J. A., and J. López-Colás. 2004. “Movilidad residencial, trabajo y vivienda en Europa.” Scripta Nova: revista electrónica de geografía y ciencias sociales 8 (159): 157–180.

- Módenes, J. A., and J. López-Colas. 2014. “Cambio demográfico reciente y vivienda en España: ¿Hacia un nuevo sistema residencial?” Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas 148: 103–134.

- Mulder, C., C. Dewilde, M. van Duijn, and A. Smits 2015. “The Association Between Parents’ and Adult Children's Home Ownership: A Comparative Analysis.” European Journal of Population 31: 495–527. doi: 10.1007/s10680-015-9351-3

- Mykyta, L. 2012. “Economic Downturns and the Failure to Launch: The Living Arrangements of Young Adults in the US 1995–2011.” US Census Bureau Social, Economic, and Housing Statistics Division. Working Paper 24.

- OECD (Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development). 2018. “Employment Rate by Age Group.” Accessed June 20, 2018. https://data.oecd.org/emp/employment-rate-by-age-group.htm.

- Ronald, R. 2008. The Ideology of Home Ownership: Homeowner Societies and the Role of Housing. Basington: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ruiz, J. 2017. “Collective Production of Discourse: an Approach Based on the Qualitative School of Madrid.” In A New Era in Focus Group Research. Challenges, Innovation and Practice, edited by R. Barbour, D. Morgan, and J. Smith, 277–302. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Salvà-Mut, F., C. Thomás-Vanrell, and E. Quintana-Murci. 2016. “School-to-work Transitions in Times of Crisis: the Case of Spanish Youth Without Qualifications.” Journal of Youth Studies 19 (5): 593–611. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2015.1098768

- Saunders, P. 1990. A Nation of Homeowners. London: Routledge.

- Schwartz, H., and L. Seabrooke. 2008. “Varieties of Residential Capitalism in the International Political Economy: Old Welfare States and the New Politics of Housing.” Comparative European Politics 6 (3): 237–261. doi: 10.1057/cep.2008.10

- Survey of Family Budgets. 2007. “INE Digital Repository.” Accessed September 8, 2017. http://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C&cid=1254736176806&menu=ultiDatos&idp=1254735976608.

- Susino, J. 2003. “Movilidad residencial: procesos demográficos, estrategias familiares y estructura social.”PhD diss. Universityof Granada.

- Valls-Fonayet, F. 2015. “El impacto de la crisis entre los jóvenes en España.” Revista de estudiossociales 54: 134–149.

- Vassenden, A. 2014. “Homeownership and Symbolic Boundaries: Exclusion of Disadvantaged Non-Homeowners in the Homeowner Nation of Norway.” Housing Studies 29 (6): 760–780. doi: 10.1080/02673037.2014.898249