ABSTRACT

Young women tell different stories about teenage pregnancies. Their stories are embedded in the storyscape of their environment, which offers a limited set of narratives. Normative discourses influence the stories young women tell about their pregnancies. Social norms and stigma play an important role in the construction of the meaning of teenage pregnancies. However, the embodiment of being pregnant constitutes meaning as well. This paper draws on findings from a qualitative study conducted in 2015 among 46 young Dutch women who got pregnant before their 20th birthday. Our study explores how young women navigate the moral arena when they are confronted with a teenage pregnancy and which role the embodiment of pregnancy plays in the construction of social meanings. The concept of storyscapes visualises how young women are constrained by their embeddedness in multiple storyscapes, defined by different and often contrasting audiences. Nevertheless, our study indicates that the momentum of pregnancy can offer agentic possibilities to take up another position towards their social environment and develop narrative agency.

Introduction

Researchers and public health agencies have predominantly defined teenage pregnancy as a potential risk of sexual activity for girls and as a social problem linked to poverty (Robson and Berthoud Citation2003). Public health policies in Europe, the US and Australia are strongly influenced by neoliberal ideology, which conceptualises individuals as rational, entrepreneurial actors whose moral authority is determined by their capacity for autonomy and self-care (Brown Citation2003). Sexual health policies aim to encourage young people to take responsibility and control their sexuality in order to prevent adverse outcomes such as unintended pregnancies (Bay-Cheng Citation2015). However, there is a contradiction between the individualistic concept of (reproductive) choice and the societal imperative to prevent pregnancy during adolescence (Mann, Cardona, and Gómez Citation2015). In the discourse of being in control, unintended pregnancies are seen as ‘natural, deserved consequences of careless behavior’ (Bay-Cheng Citation2015, 285). The neoliberal ideology of individuals being an agent of their own success reinforces the idea that teenage pregnancies are shameful (Baker Citation2009). By creating negative representations of teenage pregnancy, sexual health policies contribute to its stigmatisation (Arai Citation2009; Cherrington and Breheny Citation2005; Yardley Citation2008). Moreover, not all pregnant teenagers experience their situation only in negative terms. Therefore, many scholars advocate a re-examination of the discourses surrounding teenage pregnancies and early motherhood (Arai Citation2009). Furthermore, it is important to consider the stories young women tell themselves to understand the meaning of pregnancy in their lives (Barcelos and Gubrium Citation2014; Mann, Cardona, and Gómez Citation2015). Our study wants to contribute to this re-examination of discourses by exploring how young women in the Netherlands negotiate the meaning of teenage pregnancy, motherhood and abortion in the contemporary normative landscape.

The process through which young women understand, reproduce and rework existing narratives on teenage pregnancy can be understood as strategic negotiations: the processes through which young women situate themselves, their families and their reproductive choices in a larger social context (Barcelos and Gubrium Citation2014). These negotiations move beyond individual interpretations of social reality to a deeper recognition of how social norms, policies, and relationships shape what people think about their (sexual) selves (Schalet Citation2010). In this process of storytelling, young women develop and express narrative agency, which can be defined as the capacity to ‘weave out of those narratives and fragments of narratives a life story that makes sense for the individual selves’ (Benhabib Citation1999, 344).

Studies on teenage motherhood show that discourses on teenage motherhood run the gamut from describing the positive meanings motherhood may have to focusing solely on the social and personal problems of young mothers (McDermott, Graham, and Hamilton Citation2004). Motherhood can be an important part of young women’s construction of themselves as moral and responsible (Alldred and David Citation2010) and provide young women with a new identity and new directions in life (Coleman and Cater Citation2006). Scholars have pointed out that teenage mothers can overcome obstacles and derive psychological benefits from their pregnancy (Clarke Citation2015; Duncan, Alexander, and Edwards Citation2010). Teenage pregnancy can be a route to social inclusion, rather than exclusion (Graham and McDermott Citation2006). Their children stimulate young women to set new goals as they wish to be a role model for their children and because they have someone else for whom they are responsible (Clarke Citation2015). However, young mothers can also suffer from negative effects of stigmatisation (Yardley Citation2008), poverty and problems around education (Robson and Berthoud Citation2003) and teenage motherhood is not always experienced as wholly positive (Hoggart Citation2012). Moreover, a one-sided presentation of young motherhood in terms of personal choice and individualised resilience runs the risk of thwarting the analysis of social inequalities and inequitable circumstances. McDermott and Graham (Citation2005, 76) conclude:

despite the young mothers reflexively constructing their own life narratives, they do this within the confines of very real structural inequalities and discursive limitations. (..) In these resource-poor spaces, human action may result from a more embedded reflexivity; young women’s resilient mothering practices are the reflexive ‘choice of the necessary’.

The comforting discourse on the benefits of motherhood does not offer an alternative narrative for young women who have had an abortion. Although the Netherlands can be seen as a liberal country where abortion is legal, safe and easily available, there is a deep and manifest ambivalence about the morality of abortion in the media and in people’s attitudes (Vanwesenbeeck, Bakker, and Gessell Citation2010). A recent survey amongst Dutch youth showed that 47% of young women who had had an abortion felt ashamed about it and 59% never spoke about it (De Graaf et al. Citation2017). A review on abortion stigma indicates that women perceive stigma from friends, family, community and society as result of their decision to have an abortion (Hanschmidt et al. Citation2016). Abortion stigma can be defined as ‘a negative attribute ascribed to women who seek to terminate a pregnancy that marks them, internally or externally, as inferior to the ideals of womanhood’ (Kumar, Hessini, and Mitchell Citation2009, 628). According to this definition, women who have abortions challenge social norms regarding female sexuality and maternity, and their doing so elicits stigmatising responses from their community (Hanschmidt et al. Citation2016; Smith et al. Citation2016). As a consequence, women keep their abortion secret from friends and family, which causes psychological distress, loneliness and suppression of emotions (Hanschmidt et al. Citation2016).

Obviously, being pregnant is not just a narrative, but also a bodily experience. Often scholars do not talk explicitly about the body but about embodiment, which refers to the experience of living in, perceiving, and experiencing the world from the physical and material place of our bodies (Tolman, Bowman, and Fahs Citation2014). Bailey (Citation2001) studied the embodiment of pregnancies by interviewing middle-class pregnant women in England. Her study showed that pregnant women changed their perceptions of their sexuality and the femininity of their bodies, and gained more physical and social space in public. However, Neiterman (Citation2012) illuminated how the social position of teenage pregnant women restricts the agentic possibilities of the embodiment of their pregnancy. Being positioned at the bottom of the ‘social ladder of motherhood’ (Neiterman Citation2012), pregnant young women tried very hard to comply with prenatal regulations to perform pregnancy in a socially accepted way.

In conclusion, the strategic negotiations of young women to give meaning to their pregnancy, and subsequently to an abortion or to teenage motherhood, can be viewed as an ongoing process in interaction with social norms and discourses, opinions and moral judgements of family and friends, their sense of self and their ideas about their future, and the embodiment of being pregnant. In this article, we focus on the life stories of young women in the Netherlands who experienced unintended pregnancies. The Netherlands has a specific position when it comes to teenage pregnancies, as the teenage pregnancy rate in the Netherlands is one of the lowest in the world (Sedgh et al. Citation2015). Studies have suggested that this is related to comprehensive sexuality education at schools, availability of free birth control for young people, a supportive attitude among parents and a general liberal climate regarding sexually active youth (Brugman, Caron, and Rademakers Citation2010; Schalet Citation2010). As in other Western countries, Dutch sexual health policies reflect the neoliberal discourse, in which teenage pregnancies are presented as adverse outcomes and avoidable risks. Exploring the narrative and embodied agency of young women will contribute to the improvement of youth-friendly counselling practises and support, both during the decision-making process and afterwards. Moreover, the lived realities of young women dealing with teenage pregnancy should have implications for the revising of sexual health policies.

Method

This paper draws on findings from a qualitative study conducted in 2015 among young Dutch women who became pregnant before their 20th birthday. In this study, 46 open narrative interviews were conducted with participants aged 17 to 25 (). A criterion for inclusion was that their first pregnancy happened fewer than five years ago. The group of 46 participants included 16 young women who had had an abortion (). The participants were recruited through purposive sampling (for example at social work locations and support groups for young mothers, and through a post on a website for online counselling for young women who had an abortion), through widely distributed flyers and links at websites for young people and through snowballing. As the aim of the study was to explore how young women navigated different discourses on teenage pregnancies, we wanted to recruit both young mothers and young women who had had an abortion. The last group, however, was not easy to recruit. Although statistics show that almost two thirds (62.6%) of teenage pregnancies in the Netherlands are terminated (Hehenkamp and Wijsen Citation2016), we experienced major difficulties in finding women who were willing to talk about their experience of abortion. One reason for this was that health professionals did not stay in contact with women after their abortion, whereas they did stay in contact with women who continued the pregnancy and gave birth. But another important factor was the abortion stigma the participants revealed. During the interviews women felt reluctant to talk about their abortion and told us they were afraid of moral judgements. They often did not talk about their experiences with family and friends either, which resonates with the findings of Hanschmidt et al. (Citation2016).

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

Table 2. Decisions of participants regarding their first pregnancies.

Extra effort was also put into recruiting participants with diverse ethnic backgrounds, as the study wanted to be illustrative of women from a variety of backgrounds. Ethnic background influences the sexual discourses that women are exposed to (Cense Citation2014) and could affect the meaning of teenage pregnancy. Twelve out of 46 girls were from Suriname or the Dutch Caribbean originally; six girls had another non-Western background. The majority of participants (40 out of 46) came from economically and educationally disadvantaged backgrounds, which reflects higher rates of teenage pregnancies among groups with a low level of education in the Netherlands (De Graaf, Vanwesenbeeck, and Meijer Citation2015). Their life stories revealed that two thirds of the participants had experienced unsettling and unhappy family experiences, which in some cases had led them to leave their family homes as teenagers.

Life history approach and the concept of storyscape

This study uses a life history approach to investigate the construction of the meaning of teenage pregnancy in the context of young women’s lives. Life histories are an effective method for eliciting details about subjective experience (Plummer Citation2001). Young women construct their own life story, grounded in ‘historically evolving communities of memory, structured through class, age, race, gender and sexual preference’ (Plummer Citation1995, p 23). The concept of ‘storyscape’ offers a lens to analyse the stories young women can draw on. A ‘storyscape’ can be seen as the surrounding landscape of interconnected stories with which we inevitably interact (Ganzevoort Citation2017). The term ‘storyscaping’ has been used in fields like marketing, transmedial communication, and social change advocacy to describe the purposeful activity of creating a meaningful and multidimensional ‘landscape’ of meanings that invite the audience to envision themselves as inhabiting that landscape. It is connected to the notion of worldmaking in Paul Ricoeur’s theory of narrative (Citation1984) which has been applied to both cinema and religion (Lyytikäinen Citation2012; Plate Citation2008). The concept of storyscape thus refers to the combination of the narrative repertoires and normativity provided by the social and cultural context and the narrative audience to which the narrator responds. It is not limited to specific contents within a person’s narratives but asks which narrative world is presented to an individual and how she or he constructs a life narrative to respond to that world. In that sense, the narrator is always negotiating possible meanings with her or his narrative context. This negotiation is the necessary corollary of the storyscape. Two stages can be distinguished in the negotiation (Ganzevoort Citation2017).

First, against the backdrop of the storyscape, individuals develop a life story by reflecting on their embodied experiences and the perceived ‘reality’ around them (‘emplotment’). In this ‘referential negotiation’ people turn material reality into narrative. The next negotiation is the ‘performative negotiation’, in which people turn narrative into material and behavioural reality and facilitate new experiences and changes in reality, interacting with their narrative audience (‘enactment’). Both negotiations are relevant when studying the agentic manoeuvres of young pregnant women. Referential negotiation is present in how they tell the story of their pregnancy within their life story and in the normative discourses that mark their stories. Performative negotiations show how young women navigate the interaction with their social environment. The women are embedded in multiple storyscapes defined by different and often contrasting audiences. They use their narratives to shape, maintain or change their relationships with different audiences (parents, boyfriends, and friends).

Interviews and drawing of lifelines

An interview can be seen as an occasion of more systematic reflection and storytelling about the world (Plummer Citation1995). Our interviews were a meeting between a female interviewer who was present as a professional, and a young woman who was talking about her personal life. These different positions affected the content of the story she told, as some stories can be told in a specific context while others cannot. As the participant was selected for the interview because she had experienced an unintended pregnancy, she might feel judged or held responsible for the course her life has taken. Both interviewer and participant were aware of the social framing of teenage pregnancies as an adverse outcome. The interviewer introduced herself as working for the Dutch nongovernmental organisation Rutgers. This positioned the interviewer as taking a liberal stance towards sexually active young people and towards sexual and reproductive rights, including abortion.

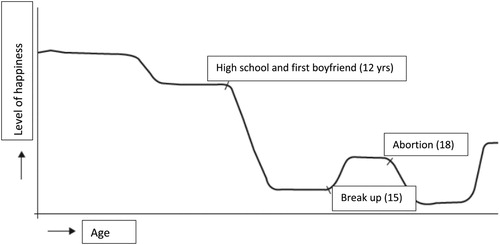

During the interviews participants were invited to draw their ‘lifeline’, with their age on the horizontal axis and the ‘level of happiness’ on the vertical one (see ). The lifeline is a narrative technique for marking and validating life events as a starting point for exploring the meaning of experiences. Drawing a visual, chronological representation of their life helps the participant to recall events from the past and helps the interviewer to ask the appropriate questions. Sensitive topics can be discussed as part of the broader story of the respondents, which prevents their entire life from being interpreted according to one particular theme or problem (Wilson et al. Citation2007). Interviews lasted around one and a half hour. All names in this article are pseudonyms.

Analysis

The interviews were recorded and transcribed. All interviews were coded using a thematic narrative technique that focuses on the kinds of stories produced in the data (Riessman Citation1993). Narratives of personal experience are stories that people tell that allow them to make sense of events, create order, contain emotions and establish connections with others, particularly when narrating difficult times in their lives (Mann, Cardona, and Gómez Citation2015). We looked for normative discourses that were present in the stories, how participants navigated these discourses, and the meaning they gave to their pregnancy and the choice they made. The lifelines illuminated which events were seen as meaningful by the participants, and what emotional value was attached to them. Secondly, we analysed the overarching storyscapes that enable the stories of the participants. In our analysis we focussed on how young women negotiated discourses on getting pregnant and on making the ‘right’ choice, how the embodiment of the pregnancy played a role in their negotiation and how they developed narrative agency by stepping out of the storyscapes of their parents and boyfriends, to ground their choices in their own morality.

Negotiating the meaning of getting pregnant

It was a bad period, I felt so embarrassed, such a fool, getting pregnant as young as this … But when she was born it was all right, I could proudly walk through the town and did not feel I had to hide anymore. (Chantal, 20, White Dutch, non-religious, first pregnant at 17, gave birth twice)

We were both young and each other’s first love, so it just happened. Of course we were both responsible, not thinking about the consequences. Which is a pity, but I am over that. I am 27 now, my daughter is 11. It just made me who I am now. (Soerin, 25, Surinamese, Hindu, first pregnant at 15, gave birth to three children)

You can never control your own life. You can put some effort into making it the way you want it, but you can’t determine it. I don’t feel that would be right either. Everything happens for a reason. Like the twins: I first had an abortion and then I become pregnant again and get twins. That is just … not a coincidence … (Felicity, 21, Surinamese, non-religious, first pregnant at 14, abortion and gave birth twice)

Negotiating the right choice

Reflecting on their choice to terminate or continue their pregnancy, the narratives of the young women again expressed different normative discourses. The first moral discourse is about viewing pregnancy and having children as a gift. For some participants terminating the pregnancy was not an option, as they considered abortion immoral. For some but not all of them this was connected to cultural or religious beliefs (Christian, Muslim or Hindu). Like the Christian young woman Jasmin:

I have always said, ‘I will never have an abortion.’ I just couldn’t. I think it is murder. I would not want to do that. (Jasmin, 20, White Dutch, Christian, first pregnant at 17, gave birth)

For half a year, I kept thinking, ‘what did I do?’ I was thinking about how old the child would have been, if I had kept it. But now I think, well, I finished my exams. And our relationship broke up. It would not have worked. I can see that now. And I am glad to know now, looking back, that it was the right thing to do. (Robijn, 19, White Dutch, non-religious, first pregnant at 17, abortion)

I found out I was eight weeks pregnant. I said: I am not going to keep it. No way. I can hardly look after myself. I never felt guilty about it. Because it was the best choice. The alternative was that I had a baby that would be raised somewhere else. I could not cope with that idea. Because they would have taken it away, I am sure. (Berber, 24, White Dutch, non-religious, first pregnant at 18, abortion and gave birth)

The three moral discourses discussed here together build a storyscape of responsibility in which the key question is how one can responsibly cope with the situation. The examples show how the balance may shift towards accepting the gift of life or towards the decision that one is not able to care for the child (or oneself), but in all cases responsibility is stressed.

The impact of the embodiment of being pregnant on making the right choice

The feeling you get, it’s just … abnormal. It really made me have second thoughts. I felt it, I reconsidered, turning things over and over … that it felt so good and how beautiful it could be. I just felt so happy! That made it very difficult to decide. But well, that’s how you feel, and I knew it would not work. I knew I had to have an abortion. So I blocked my feelings. (Robijn, 19, White Dutch, non-religious, first pregnant at 17, abortion)

I did not want it [the baby] at first. I said to my boyfriend, ‘I won’t have it.’ I’d just started my life. But when I felt it growing and kicking, well, then I could not even think about getting rid of her. (Olga, 19, White Dutch, non-religious, first pregnant at 16, gave birth)

For some women the bodily experience of being pregnant, having an abortion or giving birth was connected to earlier intrusive bodily experiences like sexual assault. Quite a lot of participants had been subjected to sexual violence at some point in their lives. Although the pregnancies they talked about were not caused by rape, their earlier experiences interfered with the embodiment of being pregnant or having an abortion. As in the story of Monique about her abortion.

I will never forget how it felt to be pregnant. The people in the clinic did not respond to that. They just checked if I wanted the abortion. But who really wants an abortion? I knew it had to happen, but somewhere, deep down, I felt I had to protect something. That it did not make sense to get rid of it. It was in a way like the experience of unwanted sex with my first boyfriend. It was both intrusive and not my initiative. It was the same feeling that I had no choice. It just had to happen. I was not in control. But I blamed myself for that, for not being in control. I thought it was entirely my fault. But now I feel I couldn’t have acted differently, not then, not in that context. (Monique, 24, White Dutch, non-religious, first pregnant at 18, abortion)

Developing narrative agency

Unintended pregnancy is a turning point in the life stories of young women. Adolescent girls are instantly confronted with major ‘adult’ responsibilities. Most participants were confronted with strong judgments of their parents and boyfriends regarding the right choice. Sometimes participants felt this was indeed the right path to take. Their life stories corresponded with the storyscapes of their parents or other significant others, which corresponds with Hoggart (Citation2012), who found that decision-making is relatively straightforward and non-ambivalent in the absence of conflicting values. However, many participants described conflicts. Sometimes girls consciously conformed to the expectations of their environment, as they felt they could not raise a child without their support or did not want to cope with the consequences of choosing a divergent path. Others described their pregnancy as a breakthrough, a turning point that made it possible to adopt a different position in relation to their parents and boyfriends. In this section we will illustrate the agentic possibilities of the momentum of pregnancy with two life stories. Although each individual life story is unique, the two life stories we describe in this section reveal patterns of negotiations and struggles that were present in the stories of many participants. The storyscapes that were present in different episodes in their lives form the background against which they can play their part and negotiate their path.

Stepping out of the storyscape of female vulnerability and dependency

Michelle is 25 at the time of the interview. She grew up as the youngest daughter in a family in which several members had mental health problems. Her mother, who had experienced child abuse, was often depressed. She was demanding and overprotective towards Michelle during her youth. During puberty Michelle tried to free herself from her mother’s constant claims. When she had her first experiences of love and sex at the age of twelve, she was sexually abused by a sixteen-year-old boy, which was the first of more negative encounters.

I did not really feel self-confident when I was a teenager. I had a very negative self-image. When I turned eighteen I wanted to be an adult very badly. So I wanted to be with a real man, the tallest, most rugged, toughest man I could find. That was my boss at work. We fell in love immediately. He was nine years older. Sexually he was dominant too. Because of my bad first sexual experience I did not want to have sex, it was very painful. But he pushed me. I felt very small in this relationship. A lot of fears all the time.

When I found out that I was pregnant I freaked out. I remember thinking ‘why does all this have to happen to me?’. I was totally lost in life and then this happened and I thought ‘my life is ruined’. I had all these fears, I had therapy and then all of a sudden I was pregnant. It was way too much. I felt I would never get a normal life. I would always be dependent on others.

My boyfriend and my parents pushed me to terminate the pregnancy, so I did. Although I do agree that I would have made a terrible mum in that period, I disagree with the way they put pressure on me. They were so angry at me, they shouted that I had to have an abortion. I blame them for that. Of course I know now that I could have prevented it [her pregnancy]. But at that time, I just didn’t think about anything. So I felt, I didn’t do it on purpose, you know what I mean? They blamed me for it.

When, at the age of twenty-one, I unexpectedly became pregnant by the same boyfriend, they told me again I should have an abortion. But this time I opposed them. I suddenly thought, ‘I can be a good mother!’ But everybody told me that I couldn’t. My boyfriend left me. Even my best friend told me that I couldn’t be a good mother. It really was hell. They all told me that you have to raise a child with two parents, so if he refused, I had no other option. And if you have had an abortion already, you can have another one. Then I thought, ‘this is not who I want to be’. Somehow I collected the willpower to stand up against them. I just wanted to prove to them that I could be a good mother. (Michelle, 22, White Dutch, non-religious, first pregnant at 18, abortion and gave birth)

Creating a moral storyscape of one’s own

Deborah was 25 at the time of the interview. She was raised in a Christian family and became pregnant at 18.

Sex before marriage is not done. So you don’t talk about sex at home, because if you’re not married it doesn’t exist. When I was eighteen I fell in love. Of course I always dreamt of having my first sex after marriage, but when somebody persuades you … I didn’t know any better and I didn’t want to disappoint him. I really regret that now. But well, I still feel I couldn’t have said no. Because he was my first love and you do everything for that person. He didn’t want to use condoms. When I think about that now, I feel embarrassed that I went along with that. He used drugs and I was totally impressed by him. I never had a boyfriend before that, nothing. Just one kiss. So I was ignorant. Everything was new. My parents always have had a huge influence on me and my choices. Whenever I wanted to do something, I was wondering if they would agree or not. So there were a lot of things I wanted but didn’t do, because of these considerations. It made me lonely and sad sometimes.

Well, when I discovered that I was pregnant, I realised that I had to look beyond his wishes. I had to think about what I wanted. He couldn’t cope with that and left me. Never heard of him again. So that was a hard period, being pregnant and alone all of a sudden. Although my parents were there. They were upset at first but after a while they accepted it. But I was very angry and not pleased to be pregnant at all. I wanted to finish school and just get on with my life. At some point my mother said, ‘Well, it is just as it is, you can’t change it. We will go on.’ But I couldn’t accept it. My mother said, ‘If you feel negative and down like this, the baby will feel it, it will feel it is unwanted.’ So I tried to change, but I kept my pregnancy hidden from everybody.

After my daughter was born, I felt happy. It was easy, my mother looked after her when I went to school. After a year I had another boyfriend. I became pregnant again. I was shocked, as the relationship had not been going on for a long time and I immediately felt, ‘how am I going to confront my parents with this? I do not want to experience all this again.’ I was busy with my education and I really felt, ‘I can’t handle this.’ My boyfriend said, ‘why not? It happened so we will have to.’ … But I was fed up with this whole period. I really could not go on with it. Although I love my [first] child, I am happy I have her, but no, not again this whole situation. I went through a very difficult period. So although my boyfriend did not agree, I had an abortion. My parents still do not know. They would find it horrible if they ever found out. My boyfriend and I had a lot of conflicts over it, but well, in the end it was me who had to choose as it was in my body. It was a hard decision to make, as I am a Christian myself. To tell you the truth I felt I did not have the right … And I was afraid I would regret it later. But when I look back now, I feel sorry but I also feel it was the right thing to do for me then. (Deborah, 25, White Dutch, Christian, first pregnant at 18, gave birth and abortion)

Discussion

Young women tell different stories about teenage pregnancies. Their stories are embedded in the storyscape of their environment, which offers a limited set of narratives. Social norms and stigma play an important role in the construction of the meaning of teenage pregnancies. In the strategic negotiation of the meaning of their pregnancy and the decision-making process, young women have to navigate the strong opinions of their family and (boy)friends and social discourses that problematise teenage pregnancy, abortion, and teenage motherhood. The narratives of young women on becoming pregnant unintendedly reflect not only the discourse of responsibility, risk, and control that is dominant in neoliberal policies, but also discourses on youth and ignorance and on destiny. Young women draw on different concepts of responsibility in their narratives about their decision, both when they choose to continue and when they choose to terminate their pregnancy. In their reflections on making the right choice, three moral discourses can be distinguished: the conviction that children are a gift (and therefore abortion is immoral), the conviction that children have the right to grow up in good conditions (and therefore parenthood is in some cases immoral), and the conviction that one must be able to look after oneself before becoming a parent. When their moral compass points towards abortion, the embodiment of being pregnant sometimes complicates this path and interferes with their moral convictions about making the right choice.

The concept of storyscapes shows how young women are constrained by their embeddedness in multiple storyscapes, defined by different and often contrasting audiences. The storyscapes that are present set the stage within which they negotiate their path. The two extensive life stories in this article illuminate how young women wrestle with the limitations of the storyscapes of their parents and boyfriends to develop their own narrative agency. One of the tasks for young women is to negotiate storyscapes of subordination of women, female vulnerability, and dependency as well as storyscapes of responsibility and individual agency. Another constraining storyscape is the taboo, the silencing of sexuality that disempowers young women in their relationships. The momentum of teenage pregnancy can offer agentic possibilities to young women as this time it is up to them to decide. Women who choose to give birth have more possibilities to frame their pregnancy as a breakthrough, as motherhood delivers social status and a new beginning. But for women who choose to have an abortion, the sole fact that this is their personal choice can also be a turning point in their lives. By resisting dominant people and storyscapes around them, some young women manage to adopt a different position in life. Although the narrative emphasis placed by young women on resilience and individual growth can be seen as manifestations of neoliberal regulation (Baker Citation2009; McDermott and Graham Citation2005), their stories can also be interpreted as resisting discourses of female vulnerability and social stigma on abortion and teenage motherhood.

This study yields novel, contextualised insights into the strategic negotiations of young women confronted with an unintended pregnancy. However, some limitations of our study are worth noting. The recruitment of women who experienced abortion was more difficult than we expected beforehand. Our announcement on websites did not yield enough participants, so we turned to professionals who might know people who wanted to participate. Because we worked with these intermediaries, most of the women with experience of abortion who were included experienced mental health problems and received professional support for them. Among these participants, we encountered no stories of young women who had an abortion and just went on with their lives without any problems. However, some of the participants who had given birth had also undergone an abortion at some point in their lives and had experienced no inner struggle after it. As for ethnic and religious diversity, we succeeded in including participants with different ethnic backgrounds but not many with strong religious affiliations.

Conclusion

Although the Netherlands established a high level of reproductive and sexual health and rights, including access to abortion, beneath the surface these rights are not yet accompanied by accommodating storyscapes. Instead, young women’s life stories testify to the trouble of gaining narrative agency over their lives, within storyscapes of female dependency, individual responsibility and blame, and moral judgments. Therefore, as many scholars in the UK and abroad have concluded, future public health policies should avoid stigmatising teenage pregnancies by associating it with social exclusion and limited aspirations (Arai Citation2009). Instead, as Barcelos and Gubrium (Citation2014, 479) argue, ‘a discursive shift is needed, to understand pregnant and parenting young women as agentic social and sexual subjects embedded in a system of stratified reproduction’. Sex educators should provide young people with multiple stories on teenage pregnancy, abortion and parenthood, that open up new storyscapes and facilitate the negotiation of narrative agency.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants in this study for their trust and for telling us their life stories, which gave us insight into their lived realities. We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Alldred, P., and M. David. 2010. “What’s Important at the End of the Day? Young Mothers’ Values and Policy Presumptions.” In Teenage Parenthood: What’s the Problem?, edited by S. Duncan, R. Edwards, and C. Alexander, 24–46. London: the Tufnell Press.

- Arai, L. 2009. “What a Difference a Decade Makes: Rethinking Teenage Pregnancy as a Problem.” Social Policy and Society 8 (2): 171–183. doi:10.1017/S1474746408004703.

- Bailey, L. 2001. “Gender Shows: First-Time Mothers and Embodied Selves.” Gender & Society 15 (1): 110–129.

- Baker, J. 2009. “Young Mothers in Late Modernity: Sacrifice, Respectability and the Transformative Neo-Liberal Subject.” Journal of Youth Studies 12 (3): 275–288. doi:10.1080/13676260902773809.

- Barcelos, C. A., and A. C. Gubrium. 2014. “Reproducing Stories: Strategic Narratives of Teen Pregnancy and Motherhood.” Social Problems 61 (3): 466–481. doi:10.1525/sp.2014.12241.

- Bay-Cheng, L. Y. 2015. “The Agency Line: A Neoliberal Metric for Appraising Young Women’s Sexuality.” Sex Roles 73: 279–291. doi:10.1007/s11199-015-0452-6.

- Benhabib, S. 1999. “Sexual Difference and Collective Identities: The New Global Constellation.” Signs 24 (2): 335–361.

- Brown, W. 2003. “Neo-liberalism and the End of Liberal Democracy.” Theory and Event 7: 1–19.

- Brugman, M., S. Caron, and J. Rademakers. 2010. “Emerging Adolescent Sexuality: A Comparison of American and Dutch College Women's Experiences.” International Journal of Sexual Health 22 (1): 32–46. doi:10.1080/19317610903403974.

- Cense, M. 2014. “Sexual Discourses and Strategies among Minority Ethnic Youth in the Netherlands.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 16 (7): 835–849. doi:10.1080/13691058.2014.918655.

- Cherrington, J., and M. Breheny. 2005. “Politicizing Dominant Discursive Constructions About Teenage Pregnancy: Re-locating the Subject as Social.” Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine 9: 89–111. doi:10.1177/1363459305048100.

- Clarke, J. 2015. “It's Not All Doom and Gloom for Teenage Mothers – Exploring the Factors That Contribute to Positive Outcomes.” International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 20 (4): 470–484. doi:10.1080/02673843.2013.804424.

- Coleman, L., and S. Cater. 2006. “‘Planned’ Teenage Pregnancy: Perspectives of Young Women from Disadvantaged Backgrounds in England.” Journal of Youth Studies 9 (5): 593–614. doi:10.1080/13676260600805721.

- De Graaf, H., S. Nikkelen, M. van den Borne, D. Twisk, and S. Meijer. 2017. Seks onder je 25e. Seksuele gezondheid van jongeren in Nederland anno 2017. [Sex Under 25. Sexual Health of Youth in the Netherlands in 2017]. Delft: Eburon.

- De Graaf, H., I. Vanwesenbeeck, and S. Meijer. 2015. “Educational Differences in Adolescents’ Sexual Health: A Pervasive Phenomenon in a National Dutch Sample.” The Journal of Sex Research 52 (7): 747–757. doi:10.1080/00224499.2014.945111.

- Duncan, S., C. Alexander, and R. Edwards. 2010. “What’s the Problem with Teenage Parents?” In Teenage Parenthood: What is the Problem?, edited by S. Duncan, R. Edwards, and C. Alexander, 1–23. London: The Tufnell Press.

- Ganzevoort, R. R. 2017. “Naviguer dans les récits. Négociation des histoires canoniques dans la construction de l'identité religieuse.” In Récit de soi et narrativité dans la construction de l’identité religieuse, edited by P.-Y. Brandt, P. Jesus, and P. Roman, 45–62. Paris: Éditions des archives contemporaines.

- Graham, H., and E. McDermott. 2006. “Qualitative Research and the Evidence Base of Policy: Insights from Studies of Teenage Mothers in the UK.” Journal of Social Policy 35 (1): 21–37. doi:10.1017/S0047279405009360.

- Hanschmidt, F., K. Linde, A. Hilbert, S. G. Riedel-Heller, and A. Kersting. 2016. “Abortion Stigma: A Systematic Review.” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 48 (4): 169–177. doi:10.1363/48e8516.

- Hehenkamp, L., and C. Wijsen. 2016. Landelijke abortusregistratie [National Abortion Registration]. Utrecht: Rutgers.

- Hoggart, L. 2012. “‘I’m Pregnant … What am I Going to do?’ An Examination of Value Judgements and Moral Frameworks in Teenage Pregnancy Decision Making.” Health, Risk & Society 14 (6): 533–549. doi:10.1080/13698575.2012.706263.

- Kumar, A., L. Hessini, and E. M. H. Mitchell. 2009. “Conceptualising Abortion Stigma.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 11 (6): 625–639. doi:10.1080/13691050902842741.

- Lyytikäinen, P. 2012. “Paul Ricoeur and the Role of Plot in Narrative Worldmaking.” In Rethinking Mimesis. Concepts and Practices of Literary Representation, edited by S. Isomaa, S. Kivistö, P. Lyytikäinen, S. Nyqvist, M. Polvinen, and R. Rossi, 47–72. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Mann, E. S., V. Cardona, and C. A. Gómez. 2015. “Beyond the Discourse of Reproductive Choice: Narratives of Pregnancy Resolution among Latina/o Teenage Parents.” Culture, Health & Sexuality 17 (9): 1090–1104. doi:10.1080/13691058.2015.1038853.

- McDermott, E., and H. Graham. 2005. “Resilient Young Mothering: Social Inequalities, Late Modernity and the ‘Problem’ of ‘Teenage’ Motherhood.” Journal of Youth Studies 8 (1): 59–79. doi:10.1080/13676260500063702.

- McDermott, E., H. Graham, and V. Hamilton. 2004. Experiences of Being a Teenage Mother in the UK: A Report of a Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies. ESRC Centre for Evidence-Based Public Policy, Lancaster University.

- Neiterman, E. 2012. “Doing Pregnancy: Pregnant Embodiment as Performance.” Women's Studies International Forum 35 (5): 372–383. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2012.07.004.

- Plate, S. B. 2008. Religion and Film: Cinema and the Re-Creation of the World. New York: Wallflower.

- Plummer, K. 1995. Telling Sexual Stories. London: Routledge.

- Plummer, K. 2001. Documents of Life 2: An Invitation to Critical Humanism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Ricoeur, P. 1984. Time and Narrative. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Riessman, C. 1993. Narrative Analysis. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

- Robson, K., and R. Berthoud. 2003. “Teenage Motherhood in Europe: A Multi-Country Analysis of Socioeconomic Outcomes.” European Sociological Review 19: 451–466. doi:10.1093/esr/19.5.451.

- Schalet, A. 2010. “Sexual Subjectivity Revisited: The Significance of Relationships in Dutch and American Girls’ Experiences of Sexuality.” Gender and Society 24 (3): 304–329. doi:10.1177/0891243210368400.

- Sedgh, G., L. B. Finer, A. Bankole, M. A. Eilers, and S. Singh. 2015. “Adolescent Pregnancy, Birth, and Abortion Rates Across Countries: Levels and Recent Trends.” Journal of Adolescent Health 56 (2): 223–230. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.09.007.

- Smith, W., J. M. Turan, K. White, K. L. Stringer, A. Helova, T. Simpson, and K. Cockrill. 2016. “Social Norms and Stigma Regarding Unintended Pregnancy and Pregnancy Decisions: A Qualitative Study of Young Women in Alabama.” Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 48 (2): 73–81. doi:10.1363/48e9016.

- Tolman, D. L., C. P. Bowman, and B. Fahs. 2014. “Sexuality and Embodiment.” In Handbook of Sexuality and Psychology, edited by D. L. Tolman, L. M. Diamond, J. Bauermeister, W. H. George, J. Pfaus, and M. Ward, 759–804. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Books. doi:10.1037/14193-025.

- Vanwesenbeeck, I., F. Bakker, and S. Gessell. 2010. “Sexual Health in the Netherlands: Main Results of a Population Survey Among Dutch Adults.” International Journal of Sexual Health 22 (2): 55–71. doi:10.1080/19317610903425571.

- Wilson, S., S. Cunningham-Burley, A. Bancroft, K. Backett-Milburn, and H. Masters. 2007. “Young People, Biographical Narratives and the Life Grid: Young People’s Accounts of Parental Substance Use.” Qualitative Research 7 (1): 135–151. doi:10.1177/1468794107071427.

- Yardley, E. 2008. “Teenage Mothers’ Experiences of Stigma.” Journal of Youth Studies 11 (6): 671–684. doi:10.1080/13676260802392940.