ABSTRACT

Existing research explores safety among young adults as a complex phenomenon in diverse social spaces. Nonetheless, it largely approaches perceptions of unsafety and safety strategies as discrete individual action. In this paper, we show how safety is created through the social interactions between young activist groups and their main target or audience, young adults. Our study aimed to explore how young adults created meanings and actions of safety within their activism. Grounded Theory method was use to collect and analyze qualitative interviews with young adults of ten social change groups located in two medium-size cities in Sweden. To interpret our findings, we drew upon interactionist concepts of shared definitions and joint action [Blumer, Herbert. 1966. “Sociological Implications of the thought of George Herbert Mead.” American Journal of Sociology 71 (5): 535–544]. Shared definitions challenged narrow notions of unsafety by identifying uniform categories and harmful stereotypes as the source of the problem, and thereby locating constraints upon the capacity of different groups of young adults to define situations as (un)safe. Joint action combined an immediate response of moving to where young adults were with an enduring response of being there for young adults. Combined, these constituted an overarching social process of collective caring, which we linked to Isabel Lorey’s [2015. State of Insecurity. London: Verso] concept of practices of caring.

Introduction

It is not difficult to find reasons to be concerned with the safety of young adults, who in Sweden range in age from early teens to late twenties. Most obvious is that physical and psychological safety enables young adults’ development as persons and as members of society (Lerner, Fisher, and Weinberg Citation2000; NRCIM Citation2002). Ensuring young adults’ safety is complicated given their ambiguous standing in between child and adult as well as the lengthy path to adulthood. Teenagers remain dependent upon adult members of society, who are accorded physical, emotional and legal independence (Moore Citation2017; Moore and McArthur Citation2017). Dependence upon adults continues after teen years, as the process of completing education, entering the labor force, and building a family has prolonged up to ten years for younger generations (Arnett Citation2000; Dennison Citation2016; Oinonen Citation2003). Then again, young adults are highly segregated from non-familial adults through socially separate institutions (Call et al. Citation2002). Even though young adulthood is considered a period of growing personal autonomy, it remains circumscribed by enduring adult authority. This tension makes ensuring the safety of young adults highly complex, and suggests the need for wide approaches in policy and research.

Yet, for several decades, approaches to safety in research and policy have focused narrowly on individual perceptions of imminent danger in public spaces, such as streets, squares and parks. With their inception in the 1980s, crime surveys found that while women and older people were more likely to report feeling afraid in public spaces, men and young adults were more likely to report experiencing victimization (Lee Citation2007). Researchers and policymakers dismissed women and older people’s fears as irrational because survey data showed that these did not correspond to actual experiences of victimization (Cops Citation2010). Initially, the main critique of this narrow approach came from feminist researchers who brought gender and other power relations into analyses (Pain Citation2000; Whitzman Citation2007). Women’s fear of violence in public spaces, studies showed, stemmed from exposure to subtler forms of routine victimization across various social spaces (Gilcrist et al. Citation1998; Kelly Citation1987; Stanko Citation1990). Feminist research further demonstrated how women’s fear and vulnerability and men’s fearlessness and chivalry in public spaces were tied to normative femininities and masculinities (Cops and Pleysier Citation2011; Sandberg and Tollefson Citation2010).

More recently, a critique of narrow approaches to fear and safety appears to come from research on young adults. Similar to feminist research, this field examines how young adults perceive unsafety and develop strategies of safety not limited to public spaces but across diverse social spaces. Social spaces can be understood as places where different social relations and interactions are considered suitable, such as home, school, nightlife and online (Lefebvre Citation2009; Simmel Citation1950). Nonetheless, existing research largely approaches young adults’ safety as discrete individual action. This is problematic for two reasons. One, it misses the implicit social interactions through which young adults’ create meanings and actions of safety. Two, it risks reinforcing broader tendencies towards individualization through which safety is being recast as private, personal responsibility rather than a public, social issue. Activism offers young adults the possibility to influence safety initiatives yet remains underexplored in the literature.

In this paper, we present a study that aimed to explore how young adults’ activist groups created meanings and actions of safety. We wanted to understand how civil society groups approached the issue of safety as part of a larger project that is examining the safety work of municipal governments in Sweden. We used Grounded Theory method to collect and analyze qualitative interviews with young adults from ten social change groups located in two medium-size cities in Sweden (approximately 100,000 inhabitants). Safety, we found, was created through implicit social interactions between the young activist groups and young adults who were the main target or audience of their explicit activist strategies. In the next section, we discuss previous research on young adults’ safety. Then, we present our theoretical framework based on interactionist concepts followed by the methods and materials used in our study. We subsequently present our empirical analysis, which we discuss in light of previous research and theory. In the final section of the paper, we discuss how our overarching concept of collective caring relates to Isabel Lorey’s (Citation2015) concept, practices of caring.

Previous studies of safety among young adults

In reviewing the literature, we found that previous studies had explored how young adults’ perceived unsafety and developed strategies of safety across diverse social spaces. We therefore organize our discussion here according to these spaces. As with the broader research on fear and violence, studies of youth safety are concerned with public spaces, in part because young adults are expected to exercise greater mobility and use of these spaces compared to children (Johansson, Laflamme, and Eliasson Citation2012; Söderström Citation2011). Cockburn (Citation2008) found that, in a low-income urban area in the United Kingdom, young adults made use of city streets and parks because they had no other place to go, yet they perceived these as unsafe. Young adults did not feel welcomed in public spaces, they felt they were seen as a threat or prey, and they faced harassment from adults (Cockburn Citation2008). Young women and men faced different gender-based forms of harassment but their strategies for safety contested gender norms by drawing upon everyday routines, social ties and a sense of neighborhood belonging (Cockburn Citation2008). In a low-income urban neighborhood in Cape Town, young teens sought to assert their independence in public spaces while simultaneously relying upon adults for protection (Parkes Citation2007). Their safety strategies consisted of avoidance, escape, risk-taking, and even helplessness. In contrast to the young adults in Cockburn’s (Citation2008) study, their strategies were gender normative: boys negotiated an authoritative or tough masculinity, and girls turned almost exclusively to a femininity of caring for others and domesticity (Parkes Citation2007). Such gender differences towards unsafety might be a means for young adults to distinguish themselves from children, Johansson, Laflamme, and Eliasson (Citation2012) argue. In their study among middle-class teens in Sweden, girls and boys enacted gender differences to categorize threats faced in public spaces as adolescents, but not as children. For example, adolescent boys were afraid of all-male gangs and girls were afraid of lone adult male rapists.

In contemporary narratives, young adults are themselves expected and encouraged to display dangerous behaviors, especially with regard to the social spaces of nightlife and partying, as Seamana and Ikegwuonu (Citation2011) argue. They found that young adults in Glasgow combined limit-pushing behavior, specifically excessive drinking, with creating attachments and deepening friendships. Fileborn (Citation2016a), in turn, captured how young adults in Melbourne handled other youths’ limit pushing behavior when attending pubs and clubs. Young adults attempted to control their external environment and maintain bodily autonomy, and they chose familiar venues where people were similar to themselves. Their strategies were gender normative in that these were designed to protect women who were seen as always vulnerable to danger and to assign men the role of women’s protector (Fileborn Citation2016a).

Institutions such as schools and after-school programs, are social spaces created purposively for young adults and therefore should ensure their safety. Yet, Moore (Citation2017) found in his study of Australian institutions that young adults and children perceived safety as constrained by their less powerful position relative to adults, who were able to decide over them. Young adults lacked knowledge and experience on sensitive topics but found adults unwilling to discuss such topics in ways that would enhance their safety. Safety, from young adults and children’s perspectives, was a set of feelings built upon trusting relationships and familiarity as well as order and orderliness (Moore and McArthur Citation2017). Similarly, Finnish students from seventh to ninth grades understood safety in school in terms of social ties, such as feeling welcomed and appreciated, able to make one’s own decisions, and feeling belonging among peers (Syrjäläinen et al. Citation2015). They felt unsafe when adults failed to react in the face of violence and bullying. Yet, the cause of unsafety in school was perceived as stemming from those who were ‘different’ and safety strategies emphasized ‘familiarity, ordinariness and homogeneity as well as supervision and security’ (Syrjäläinen et al. Citation2015, 69).

Digital platforms are social spaces where young adults appear to have greater autonomy in handling unsafety, as evidenced by the peer-centered approaches found in a study among high-school students in Catalonia. Students perceived unsafety as the protection of privacy and intimacy online whereas adults were concerned with young adults’ exposure to harmful and illegal content (Poblet et al. Citation2017). Their respective strategies for safety diverged as well: while adults wanted young adults to report and denounce harmful content to authorities, young adults fostered a self-reflexive relationship within the digital ecosystem by maintaining their connection to others and preserving their personal autonomy (Poblet et al. Citation2017).

Activism are final social spaces addressed by previous research on young adults’ safety. In Canada and the U.S., Fetner et al. (Citation2012) found that high school students created Gay and Straight Alliances as a safe space from violence, harassment, discomfort, and social exclusion resulting from heteronormativity and gender norms. Nonetheless, to create this safe space, Gay and Straight Alliances were more likely to include straight people while excluding Trans and people of color (Fetner et al. Citation2012). The authors concluded that students’ strategies of increasing awareness, educating others and raising funds were less effective than pursuing institutional or policy change.

In contrast to the predominant research on fear and safety, research on young adults’ safety is not limited to individual perceptions of imminent danger in public spaces. Instead, it demonstrates how young adults’ perceive unsafety and develop safety strategies as inextricably linked to social ties and the quality of relationships within various social spaces. While at times, young adults reproduce normative prescriptions of safety according to gender, age and class, at other times they resist prescribed norms, including by developing their own definitions. Nonetheless, despite attention to relational accounts of safety (e.g. Fileborn Citation2016b), current scholarship largely approaches perceptions of unsafety and safety strategies as discrete individual action. As such, knowledge of the implicit social interactions through which young adults’ construct meanings and actions of safety is limited. Of the various social spaces, activism likely offers young adults the greatest possibilities to forge new meanings and actions of safety, yet it remains underexplored.

Conceptualizing safety as a social process

We drew upon an interactionist perspective to interpret our findings because, in contrast to both individual actor and social structure perspectives, it offers concepts for exploring the social interactions through which meanings and actions of safety are constructed (Blumer Citation1966). Moreover, an interactionist perspective permitted interpreting implicit meanings and actions in contrast to collective action/social movement theories that focus on explicit ones.

According to this perspective, human action develops through social interactions whereby people interpret the meaning of one another’s actions and define how each is to act (Mead Citation1934). Human action is understood as joint action or ‘the articulation of the acts of participants’ where people do things together without each person taking the same line of action (Blumer Citation1966, 540). Joint action even occurs among collectivities, such as the young adults’ social change groups in our study and those through which they interact with other young adults, such as schools and after-school centers. Common or shared definition form the basis of joint action: participants ‘build up their lines of action and fit them together through the dual process of designation and interpretation’ (Blumer Citation1966, 18). A shared definition is created continuously through participants conveying interpretations to themselves and one another (Blumer Citation1966). Joint action gains consistency as participants act according to its shared definition, thus taking the form of a trajectory or process.

Contrary to common assumptions that interactionism is unable to account for power and inequality, this perspectives offers an alternative approach for doing so. Blumer writes (Citation1969, 19) ‘It is the social process in group life that creates and upholds the rules, not the rules that create and uphold group life.’ Power is generated and maintained through an on-going social process of collective negotiation within face-to-face encounters and interpersonal relationships (Hall Citation1985; Ridgeway and Kricheli-Katz Citation2013; Thye and Kalkhoff Citation2014). Power is understood as the capacity ‘to define the situation and establish shared definitions of reality’ (Thye and Kalkhoff Citation2014, 33). The creation and reproduction of inequalities, such as those based on age and gender, occurs through joint action whereby people construct shared definitions that legitimate, accommodate and contest how power is used, by whom and for who. People are empowered and restricted in defining a given situation not only by immediate face-to-face interactions but also by the actions or potential actions of others outside the situation (Schwalbe et al. Citation2000).

Shared definitions pertain to all aspects of social life, including emotions. They function as feeling rules to direct when, where and how actors feel and display emotions in a given situation (Hochschild Citation1979). Safety is often understood as an emotion. For example, in secondary schools, students are expected to feel and display feeling safe. Yet, acts of harassment, threats or violence occur among schoolmates and adults. In this situation, students face a contradiction between feeling and displaying safety according to shared definitions, and feeling endangered in response to potential victimization. To deal with this contradiction, students might manage their emotions by covering up their fear of or exposure to victimization to avoid shame for not being able to feel safe in this situation. This is referred to as emotion management, which goes hand and hand with conditioning emotional subjectivities to constitute central processes for reproducing inequality (Schwalbe et al. Citation2000). How emotions are managed helps to sustain, acquiesce or destabilize meanings of power and inequality (Fields, Copp, and Kleinman Citation2006; Schwalbe et al. Citation2000).

While much of joint action is consistent, uniform and routine, it is always open to the possibility of ambiguity, creativity and change (Blumer Citation1969). This is because the trajectory of joint action and share definitions are always contingent upon performance (Blumer Citation1969). Activists groups in particular are in a favorably position to forge new joint action and shared definitions through their collective action strategies; they might even challenge feeling rules and the processes reproducing inequality (Hochschild Citation1979). Coe and Schnabel (Citation2011, 668) propose the term ‘orquestrating emotions’ to refer to ‘activists’ ability to balance even contradictory expectations [regarding feeling and displaying emotions] and to actively transform these into a greater whole that works in their favor.’

The framework outlined here provides key concepts for analyzing the social interactions through which young adults’ construct meanings and actions of safety within activism. First, it turns attention to the joint action into which the discrete lines of action among young adults’ activist groups ‘fit and merge’ (Blumer Citation1966, 541). Second, it focuses on the shared definitions created to guide their joint action as well as the constraints faced in doing so. Third, it sheds light on how young adults’ activist groups negotiate their capacity to define what safety is, including in relation to feeling rules and emotion management. Finally, it locates how young adults’ activist groups reproduce established definitions of safety but also potentially disrupt these by putting forth alternative definitions and asserting new emotional subjectivities (Schwalbe et al. Citation2000).

Methods and materials

Grounded theory method was selected because it permitted openness to explore how young adults’ created meanings and actions of safety within their activism as well as abstraction to formulate concepts based on the data (Charmaz Citation2014). These aspects align with Blumer’s (Citation1969) methodological approach for the empirical study of human interaction. Indeed, Charmaz (Citation2014) proposes Symbolic Interactionism and Grounded Theory method as a suitable theory-method package. Following Charmaz (Citation2014), we understand the materials as co-constructed between participants and ourselves, while acknowledging our role in analyzing these materials on a more abstract level.

The study was conducted in two cities located away from the metropoles of southern Sweden, and therefore less visible in debates about safety. We purposively sought activist groups that identified as young adults and were oriented towards social change issues, such as young women’s empowerment, children’s welfare, alcohol and drug-free lifestyles, integration of newly arrived immigrants and LGBTQ identities. In Sweden, these groups pertain to a well-established, mainstream voluntary sector. Contact information was identified initially through Internet searches and personal networks. Chain referral sampling was then used to obtain subsequent contact information, whereby each group contacted was asked to help us contact other groups. Our final sample included five groups in each city, or ten groups in total, across four types: formal youth civic associations linked to national organizations, informal grassroots associations, high school-based groups, and municipal initiatives (i.e. youth councils).

With each group, a single in-depth interview was conducted with one to three key activists/group leaders, for a total of twenty-four participants, twelve per city. Participants were between eighteen and thirty years old. Interviews began with asking participants to describe in their own words their group’s social change efforts, including explicit objectives, strategies and activities. Thereafter, they were asked to discuss how they understood safety according to their own interpretations of this term. Finally, participants were asked to reflect upon how they saw their group’s social change efforts as contributing to safety according to their own interpretations, if at all. Our sample and data collection procedure followed Blumer’s (Citation1969, 41) methodological approach for the empirical study of human interaction by consisting of well-informed observers in the sphere of young adults’ activism and qualitative (group) interviewing respectively.

Before each interview, participants were informed about the research project, the main purpose and content of the interview, and the intended use the information generated from it. These same topics were covered in a letter given to each participant. Participants gave oral consent to participate in the interview. In order to maintain participants’ identity confidential, we refer to the settings as City A and City B and we use generic pseudonyms for activist group names in the presentation of the results.

The interviews were transcribed verbatim and imported into MAXQDA software program for analysis. Beginning with open coding, we studied every line of written data comparatively and labeled each line/segment with a word(s) that reflected ideas identified in the data (Charmaz Citation2014). The gerund (‘-ing’) form was used to code for action. Open codes were sorted into clusters by grouping together those that related to one another, and each group was studied and named. In focused coding, these preliminary categories were used to re-examine all open codes, compare them with one another, and discard irrelevant codes. In theoretical coding, the connections between categories were examined and synthesized into a whole. As emerging theoretical categories clarified what was going on, data collection and analysis was ended. The step of re-constructing theory is presented in the next section.

Meanings and actions of safety within young adults’ activist strategies in Sweden

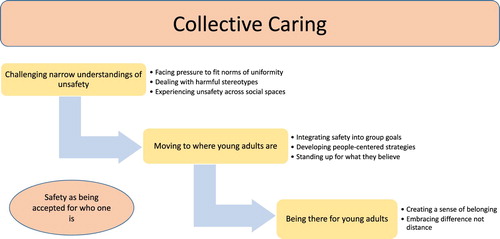

Through our analysis, we constructed three categories: challenging narrow understandings of unsafety, moving to where young adults are, and being there for young adults. See .

We interpreted the first category as shared definitions of unsafety, and the second and third categories as joint action to address unsafety guided by shared definitions (Blumer Citation1966, Citation1969). Both shared definitions and joint action of unsafety were created through the implicit social interactions between the young activists groups and the young adults toward whom their explicit activist strategies were directed. Together, these categories interlinked to form the overarching social process of collective caring, which we found aligned most closely with Isabel Lorey’s (Citation2015) concept, practices of caring.

Challenging narrow understandings of unsafety

The shared definitions entailed a critique of narrow understandings of unsafety as imminent danger or threat, which our informants argued, focused on symptoms rather than the source of the problem. As an alternative, the shared definitions provided a complex interpretation of unsafety as comprised of three features: facing pressure to fit norms of uniformity, dealing with harmful stereotypes, and experiencing unsafety across social spaces.

According to the young activists, young adults experienced unsafety through facing pressure to fit norms of uniformity or sameness. Current norms they spoke about included having to be online, meeting an appearance standard, performing well academically and/or in sports, and going out at night and using alcohol. The young activists described differences in the norms youth should fit based on core social categories, with gender being a main one. A member of the girl-only Pixie Center in City A explained the pressures girls faced in school from both teachers and classmates:

Demands involve how you have to look, how you have to behave – you are not supposed to be too quiet but not too rowdy, and not bad academically, and if you wear the wrong clothes, then you are bullied because of that.

From the young activists’ perspectives, risk of, or exposure to, danger occurred in relation to the pressure to fit norms of uniformity. Even if verbal and physical threats and abuse from other youth or adults were experienced individually, these originated from inequalities based on social categories. Gender norms denoted that young men feel and act brave in the face of physical violence and young women feel and act so afraid of sexual violence that it had become an everyday routine, as the following dialogue between two members of the Young Women’s Empowerment Center in City B exemplifies:

Respondent A: It is a given that we have to be afraid in public, that we cannot even think in the form of “What? I don’t need to be afraid when I am in public” or “Could I deserve this because I think I am a good person?” (…) For so long, we have negotiated away our own limits of what we deserve …

Respondent B: Exactly … it is impossible to disconnect unsafety from the built-in fear, everyday fear that we talk with young women about: yes, threats and violence … it is so deeply built-in that one does not even think about it. When I bicycle home from here in daylight, I always go through the woods, but when it is dark outside, I do not. It is not a choice I take but rather natural, and I do not even think about it, I just do it.

Many have this image of people who come to Sweden. Then, a distinction emerges where people who have grown up here do not talk with unaccompanied migrant youth. When they grow up, they see migrants as scary and do not dare go to certain places. But, it has to do with getting to know one another, and then one realizes that it is all right with those persons. Member of the Youth Council’s Tolerance Committee in City A.

Young adults can feel unsafe everywhere. School is not the best right now in Sweden, there is a lot of unsafety, and then the internet is another place where one can feel unsafe, because there [aggression] can be more anonymous. Youth also have other traditions or customs that are not accepted by their family. Member of the Red Cross Youth Association in City B.

Especially in the different refugee settlements, people do not know whether they are going to be sent home or when an interview is going to be or not, what is going to happen, yes, it is not easy. Member of the Friends of Migrants Youth Group Network in City B.

Respondent: Safety is central to work with, that one is able to be oneself in a place where one feels safe and accepted. Where it is an open environment and open climate, and no one is excluded in the ways one otherwise is.

Interview: How can one be excluded otherwise?

Respondent: It can be different sexual preferences, gender identities, and so forth, generally speaking, society is not very accepting.

Joint action in response to unsafety

Joint action, guided by the shared definitions above, addressed unsafety in both immediate and enduring ways.

Moving to where young adults are

To address young adults’ unsafety in an immediate way, young activist groups described moving themselves and their activities to the different social spaces where young adults were, including schools, after-school centers, nightlife, public spaces and even online. This joint action consisted of integrating safety into group goals, developing people-centered activities, and standing up for what they believed.

Informants described integrating the goal of safety into their respective group goals. ‘We work so that youth can feel safer; we do our best for that’ member of Youth for Safety; and ‘Safety is extremely important for us; it is something we work for; it is one of our hallmark issues’ member of the Red Cross Youth Association, both in City A. While the young activist groups were working on different social change issues, they were part of a longstanding voluntary sector in Sweden aimed at improving social conditions among the disadvantaged or marginalized. Surprisingly, the young activists had infused into these longstanding volunteer groups their own new goals of questioning social norms that privileged homogenous social categories according to gender, ethnicity, and sexual identity. The young activists directly related these group goals to what they understood as needed to address unsafety: those who did not fit into to normative groups and faced harmful stereotypes were unsafe, as described by the following dialogue with two members of the Young Women’s Empowerment Center in City A.

Respondent 1: We primarily provide support to people who define themselves as young women by giving them information on gender equality and issues that we think are important.

Interviewer: And what types of issues are important for you?

Respondent 2: For example, that young women feel safe, that they know that they can contact some place if needed, if they need someone to talk to about gender questions, LGBTQ issues.

Many young adults wanted to participate so there was a need to share responsibility in order for everyone to do the activities of their interests. I began with outdoor activities but then found that we could have a baking group and then a study circle … the only thing needed for an activity is initiative, engagement, there is no demand.

A final feature of young activists’ immediate response to unsafety was standing up for what they believed. Activities were oriented not only to help specific categories of young adults but also to raise awareness among young adults overall. They did this by speaking out about topics and developing public debates, for instance, on migration policy or LGTBQ issues. As the following dialogue with a high school LGBTQ group in City A described:

Respondent: I feel respected by a lot of classmate who are like, “Wow, he dares to stand up for who he is”. It is encouraging. Otherwise, one does not know how to act and stays quiet.

Interviewer: But the first time you all spoke out, were you scared?

Respondent: No, we felt that we were well prepared about what we wanted to say. We knew what we wanted to say and what we wanted to get out of it.

I want to have a world without borders rather than challenge migration policies – that is a good goal, but I want to go the whole way. I feel that when I am engaged with other people who also dare to dream about that world, there is so much energy in that vision.

Being there for young adults

To address young adults’ unsafety in an enduring way, young activist groups described being there for young adults. According to informants, changing safety in society involved not only helping young adults immediately but also transforming the relationships among them: ‘Safety can be about leaving me in peace but it can also be about hang on to me tight when I need it. We create safety through relationships,’ explained a member of the Young Women’s Empowerment Center in City B. Relationships that foster safety have to be created, as the following quote from No One is Illegal in City B illustrates, ‘One cannot just say to people to trust one another and be kind to each other, rather it is necessary to create the contact between them.’

This entailed creating a sense of belonging among young adults by providing them with companionship, listening to their concerns, and putting oneself in their shoes:

With groups of unaccompanied refugee children, we get together and get to know them, with the goal that they feel welcome, learn the language and help them to feel that this is their home. Member of the Tolerance Committee, Youth Council in City A.

It is not necessary for an incident to happen for us to help. It may be enough that we walk around the school corridor and listen to someone who wants to talk, and say, “go ahead, you can do that, I will listen.” Member of Youth for Safety in City A.

Being there for young adults further entailed embracing difference in order to close the distance between people, as the following quote from Friends of Migrants Youth Group in City B clarified:

Respect is very important, to respect that we are different and not try to say that we are all alike or that we all have to do as the Swedes do, no. Just understand why other people do something in a certain way and not in another way, and accept that, that we do things differently and have different backgrounds and opinions, but we can also be friends.

It is a safe and open space where everyone is welcome and there is no demand anywhere upon people, except that you decline drugs, no other demand for you. I feel very welcome to be here. Member of the Youth Sobriety Association in City B

The joint action here challenged power and inequality by enhancing the ability of certain categories of young adults to define situations as unsafe or safe (Schwalbe et al. Citation2000; Thye and Kalkhoff Citation2014). It further resisted the emotion management expected of young adults in relation to feeling rules, including gendered ones (Hochschild Citation1979; Schwalbe et al. Citation2000). For example, joint action affirmed that boys could feel vulnerable and girls did not have to be, and that both girls and boys could take care of others, even strangers, without being devalued (Hochschild Citation1979). The focus on transforming relationships contested established shared definitions of young adulthood as characterized by a dichotomous tension between personal autonomy and adult authority. In this sense, joint action re-shaped the conditioning emotional subjectivities not only for participants in young activist groups but also for other young adults, that is, their broader constituency (Coe and Schnabel Citation2011; Schwalbe et al. Citation2000).

While the young activist groups in our study were part of longstanding volunteer sector in the Swedish context, the joint action suggested a more radical response to safety by contesting the shortcomings of social welfare policies as well as the equality and diversity policies in Sweden. This especially in the context of the scaling back of state interventions and increased emphasis on individual self-responsibility. The young activist groups interpreted this situation as a gap that both joint action and activist strategies helped fill:

It feels as though this network is needed, like there is a gap somewhere else, I do not know whether something is not working in the municipality or somewhere else, but that voluntary engagement is needed indicates that something higher up is missing. Member of Friends of Migrants Youth Group in City B.

Conclusions: collective caring

Our analysis above shows how safety was created through implicit social interactions between the young activist groups and the young adults who made up their main audience, that is, embedded within explicit activist strategies. Meanings and actions of safety differed markedly from those established by adult researchers and policymakers, including out own. Unsafety was understood as a social issue that required coordinated actions in the form of both an immediate and enduring response. This social process of collective caring not only fills a gap in the individual approaches to studying young adults’ safety but also offers an alternative perspective to the individualization of safety more broadly in society and politics. Most notably missing among our informants’ accounts as well as previous studies is attention to safety among racialized and disabled young adults, which suggests crucial lines for future research.

In the final step of Grounded Theory method, we linked our concept of collective caring to existing theory and found that it best fit with Lorey’s (Citation2015) concept practices of caring. In her analysis of contemporary practices of governing the precarious, presented in State of Insecurity (Citation2015), Lorey argues that precariousness is an existential state that designates what constitutes life in general for all humans. Despite efforts to create safety, it is impossible for anyone to be protected from precariousness; there is no life where we are not in a precarious state. In Lorey’s words: ‘All security retains the precarious; all protection and all care maintain vulnerability; nothing guarantees invulnerability’ (Citation2015, 20). Lorey further argues that precarity can be understood as an effect of the political and legal regulations that are specifically directed towards protecting us against this same precarity. In other words, the practices of promoting safety are also producing the problem of safety that these measures address.

Following the ontological logic of precariousness as well as the analytical logic of practices, the practices of safety that the young activist groups in this study perform can be interpreted as practices of caring, and these practices address (or produce) unsafety as a problem of lack of collective care. Especially the joint action of moving to where young adults are and being there for young adults are practices that illustrate how working for safety becomes a practice of caring. In her study, Lorey (Citation2015, 91) illustrates this with a group of feminist activists in Madrid, Precaritas al la deriva; ‘Their central political and social strategy consists in enhancing the status of care’. The Precaritas focuses on the practice of being among women, meeting women and developing their practices with the women they meet, but with no search for a common identity. Rather, there is an ambition of finding common notions among the women they meet, focusing on the common boundaries and possibilities that different bodies have.

Although the young activist groups in our study did not depict departing only from their own experiences of precariousness to the same extent as the Precaritas, their practices are similar, as is their ambition to embrace differences between the young adults they meet. Indeed, the young activist groups in our study gained a broader understanding of experiences f precariousness through interactions with diverse young adults who they targeted. Thus, our results shed light on a mentality of striving for safety, i.e. safety becomes a form of lived practice that could be described as ‘a logic of care’ in the words of Lorey (Citation2015, 94). Accordingly, we believe that there is a fundamental potential in the practices of safety captured by our empirical analysis for transforming safety initiatives into democratic initiatives. If the main problem of safety work is to practice care, this could be regarded as both a critique of society as ‘careless’ as well as a potential practice of how care could be included in future democratic practices.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Marianne and Marcus Wallenberg Foundation under Grant 2012.0211 for the project ‘Fear and Safety in Policy and Practice: Overcoming Paradoxes in Local Planning’ managed by the Umeå Center for Gender Studies. We are grateful to our collaborators Linda Sandberg, Chris Hudson and Jennie Brandén as well as three anonymous reviewers from CJYS for their comments on an earlier version.

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, AC. The data are not publicly available due to restrictions e.g. their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Anna-Britt Coe http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1975-9060

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arnett, Jeffrey J. 2000. “Emerging Adulthood: A Theory of Development from the Late Teens through the Twenties.” American Psychologist 55 (5): 469–480.

- Blumer, Herbert. 1966. “Sociological Implications of the thought of George Herbert Mead.” American Journal of Sociology 71 (5): 535–544.

- Blumer, Herbert. 1969. Symbolic Interactionism: Perspective and Method. Berkeley: University of California.

- Call, Kathleen T., Aylin Altan Riedel, Karen Hein, Vonnie McLoyd, Anne Petersen, and Michele Kipke. 2002. “Adolescent Health and Well-being in the Twenty-first Century: A Global Perspective.” Journal of Research on Adolescence 12 (1): 69–98.

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Cockburn, Tom. 2008. “Fears of Violence among English Young People: Disintegration Theory and British Social Policy.” New Directions for Youth Development 2008: 75–91.

- Coe, Anna-Britt, and Annette Schnabel. 2011. “Emotions Matter After All: How Reproductive Rights Advocates Orchestrate Emotions to Influence Policies in Peru.” Sociological Perspectives 54 (4): 665–688.

- Cops, Diederik. 2010. “Socializing Into Fear: The Impact of Socializing Institutions on Adolescents’ Fear of Crime.” Young: Nordic Journal of Youth Research 18 (4): 385–402.

- Cops, Diederik, and Stefaan Pleysier. 2011. “‘Doing Gender’ in Fear of Crime: The Impact of Gender Identity on Reported Levels of Fear and Crime in Adolescents and Young Adults.” British Journal of Criminology 51 (1): 58–74.

- Dennison, Renée Peltz. 2016. “Transition to Adulthood.” In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Family Studies. 1st ed. edited by Constance L. Shehan, 1–4. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons.

- Fetner, Tina, Athena Elafros, Sandra Bortolin, and Coralee Drechsler. 2012. “Safe Spaces: Gay-straight Alliances in High Schools.” Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue Canadienne de Sociologie 49 (2): 188–207.

- Fields, Jessica, Martha Copp, and Sherryl Kleinman. 2006. “Symbolic Interactionism, Inequality and Emotions.” In The Handbook of the Sociology of Emotions, edited by Jan E. Stets, and Jonathan H. Turner, 155–178. Boston: Springer.

- Fileborn, Bianca. 2016a. “Doing Gender, Doing Safety? Young Adults’ Production of Safety on a Night Out.” Gender, Place & Culture 23 (8): 1107–1120.

- Fileborn, Bianca. 2016b. Reclaiming the Night-time Economy: Unwanted Sexual Attention in Pubs and Clubs. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Gilcrist, Elizabeth, Jon Bannister, Jason Dilton, and Stephan Farrall. 1998. “Women and the Fear of Crime: Challenging the Accepted Stereotype.” British Journal of Criminology 38 (2): 283–298.

- Hall, Peter. 1985. “Asymmetric Relationships and Processes of Power.” Studies in Symbolic Interaction Supplement 1: 309–344.

- Hochschild, Arlie. 1979. “Emotion Work, Feeling Rules, and Social Structure.” American Journal of Sociology 85 (3): 551–575.

- Johansson, Klara, Lucie Laflamme, and Miriam Eliasson. 2012. “Adolescents’ Perceived Safety and Security in Public Space: A Swedish Focus Group Study with a Gender Perspective.” Young: Nordic Journal of Youth Studies 20 (1): 69–88.

- Kelly, Liz. 1987. “The Continuum of Sexual Violence.” In Women, Violence, and Social Control, edited by Jalna Hamner, and Mary Maynard, 44–60. Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press International.

- Lee, Murray. 2007. Inventing Fear of Crime: Criminology and the Politics of Anxiety. Collumpton: Willlan Publishing.

- Lefebvre, Henri. 2009. State, Space, World: Selected Essays. Edited by Neil Brenner, and Stuart Eldon. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Lerner, Richard M., Celia B. Fisher, and Richard A. Weinberg. 2000. “Toward a Science for and of the People: Promoting Civil Society through the Application of Developmental Science.” Child Development 71: 11–20.

- Lorey, Isabel. 2015. State of Insecurity. London: Verso.

- Mead, George Herbert. 1934. Mind, Self and Society. Edited by C. W. Morris. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Moore, Tim P. 2017. “Children and Young People’s Views on Institutional Safety: It’s Not Just Because We’re Little.” Child Abuse & Neglect 74: 73–85.

- Moore, Tim, and Morag McArthur. 2017. “‘You Feel It in Your Body’: How Australian Children and Young People Think About and Experience Feeling and Being Safe.” Children & Society 31 (3): 206–218.

- National Research Council and Institute of Medicine. 2002. Community Programs to Promote Youth Development. Washington: National Academy Press.

- Oinonen, Eiikka. 2003. “Extended Present, Faltering Future. Family Formation in the Process of Attaining Adult Status in Finland and Spain.” Young: Nordic Journal of Youth Research 11 (2): 121–140.

- Pain, Rachel. 2000. “Place, Social Relations and the Fear of Crime: A Review.” Progress in Human Geography 24 (3): 365–387.

- Parkes, Jenny. 2007. “Tensions and Troubles in Young People’s Talk about Safety and Danger in a Violent Neighbourhood.” Journal of Youth Studies 10 (1): 117–137.

- Poblet, Marta, Emma Teodoro, Jorge González-Conejero, Rebeca Varela, and Pompeu Casanovas. 2017. “A Co-regulatory Approach to Stay Safe Online: Reporting Inappropriate Content with the MediaKids Mobile App.” Journal of Family Studies 23 (2): 180–197.

- Ridgeway, Cecilia, and Tamar Kricheli-Katz. 2013. “Intersecting Cultural Beliefs in Social Relations: Gender, Race, and Class Binds and Freedoms.” Gender & Society 27: 294–318.

- Sandberg, Linda, and Aina Tollefson. 2010. “Talking about Fear of Violence in Public Space: Female and Male Narratives about Threatening Situations in Umeå, Sweden.” Social & Cultural Geography 11 (1): 1–15.

- Schwalbe, Michael, Daphne Holden, Douglas Schrock, Sandra Godwin, Shealy Thompson, and Michele Wolkomir. 2000. “Generic Processes in the Reproduction of Inequality: An Interactionist Analysis.” Social Forces 79 (2): 419–452.

- Seamana, Peter, and Theresa Ikegwuonu. 2011. “‘I Don’t Think Old People Should Go to Clubs’: How Universal is the Alcohol Transition amongst Young Adults in the United Kingdom?” Journal of Youth Studies 14 (7): 745–759.

- Simmel, George. 1950. The Sociology of George Simmel. Translated by Kurt H. Wolf. London: Collier-MacMillan Publishers

- Söderström, Sylvia. 2011. “Staying Safe While on the Move: Exploring Differences in Disabled and Non-disabled Young People’s Perceptions of the Mobile Phone’s Significance in Daily Life.” Young: Nordic Journal of Youth Research 19 (1): 91–109.

- Stanko, Elizabeth A. 1990. “When Precaution is Normal: A Feminist Critique of Crime Prevention.” In Feminist Perspectives in Criminology, edited by Loraine Gelsthorpe, and Allison Morris, 171–183. Milton Keys: Open University Press.

- Syrjäläinen, Eija, Pirjo Jukarainen, Veli-Matti Värri, and Simo Kaupinmäki. 2015. “Safe School Day According to the Young.” Young: Nordic Journal of Youth Research 23 (1): 59–75.

- Thye, Shane, and Will Kalkhoff. 2014. “Theoretical Perspectives on Power and Resource Inequality.” In Handbook of Social Psychology of Inequality, edited by Jane D. McLeod, Edward Lawler, and Michael Schwalbe, 27–47. Dordrecht: Springer Sciences and Business Media.

- Whitzman, Carolyn. 2007. “Stuck at the Front Door: Gender, Fear of Crime and the Challenge of Creating Safer Space.” Environment and Planning A 39 (11): 2715–2732.