?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The article investigates entry-stage employment trajectories of young people in Germany, asking whether transitions into continuous employment indicate successful labour market integration. Applying a novel multidimensional approach to precariousness to individuals’ employment and household trajectories, we understand entry-stage employment trajectories holistically. The balanced-panel sample is drawn from the German Socio-Economic Panel, with a focus on young men and women between 15 and 25 years of age in the first year of the sample period who had been employed at least once (n = 1360).

Dual-channel sequence-cluster analysis reveals considerable variation in the precariousness of young people’s entry-stage employment. While almost all young men and women experience periods of precariousness, the durations vary substantially. Precarious employment or precarious living conditions frequently occur during education. Our results confirm that individuals with disrupted employment trajectories are seldom successfully integrated into the labour market and frequently experience precarious employment. In previous research, transitions into continuous employment have been understood as the hallmark of successful labour market integration. This holds true for young women but not for young men, who experienced continuous and precarious entry-stage employment. To correctly identify young men’s successful labour market integration, additional information about their employment precariousness is required.

1. Introduction

Although young adults today are better qualified than ever, they also face more insecure employment situations than previous cohorts. Deregulated labour markets and increasing competitive pressure due to globalization have caused a substantial increase in precarious and non-standard employment among young people entering the labour market (e.g. Kurz, Steinhage, and Golsch Citation2005; Buchholz et al. Citation2008). Generally, entry into employment marks a crucial threshold because it affects employment careers in the long run: discontinuous transitions into the labour market increase the risk of later unemployment and give rise to disrupted career pathways in subsequent transitions (Luijkx and Wolbers Citation2009; Manzoni and Mooi-Reci Citation2011; Nordström Citation2011; Nilsen and Reiso Citation2014). A substantial literature thus deals with the quality of entry-stage employment, with the primary focus on standard vs. non-standard employment (e.g. Kurz, Steinhage, and Golsch Citation2005; Gash and McGinnity Citation2007; Bukodi et al. Citation2008; Gash Citation2008; Gebel Citation2010). However, a number of studies have questioned this assumption of a simple dichotomy of ‘good’ continuous standard employment and ‘bad’ discontinuous non-standard employment, for instance, because low-income standard employment might also be precarious (Strengmann-Kuhn Citation2001, 137; Frade, Darmon, and Laparra Citation2004, 41; Cranford and Vosko Citation2006, 45; Dörre Citation2006, 183). To overcome this shortcoming of the non-standard employment literature, this article tests the success of entry-stage employment trajectories using a newly developed multidimensional precariousness measure. It accumulates the precarious aspects of employment in order to provide an overall picture of employment quality regardless of whether an individual is in standard or non-standard employment. The analysis focuses on young people entering the labour market and their households. Young people’s first employment experiences are closely linked to their households, which provide them with certain resources. If adequate resources are present, young people may thrive; if absent, their labour market choices are constrained (Kraemer Citation2008; Clement et al. Citation2009). To take the household as a relevant variable for successful labour market integration into account, we also measure the precariousness of young people’s own households or parental households.Footnote1

By applying this new approach to young men and women in Germany, the article tests the assumption that continuous employment is the hallmark of successful labour market integration. Should differences in the quality of young people’s employment be included in analyses of successful entry-stage employment trajectories? The term quality refers to secure and non-precarious employment as opposed to precarious employment. Previous research does not provide consistent results: precariousness might be a general phenomenon that occurs in most entry-stage employment trajectories (Giddens Citation1990; Beck Citation1992) or a phenomenon specific to disadvantaged young adults’ career patterns (Kurz, Steinhage, and Golsch Citation2005; Buchholz et al. Citation2008; Schels Citation2013). Exacerbating this lack of clarity, articles that deal with young people’s transitions into the labour market usually rely on measures of success in early employment trajectories that regard more or less every transition into continuous employment as a success (Brzinsky-Fay Citation2007; Elzinga and Liefbroer Citation2007; Robette Citation2010; Bussi Citation2016; Pedersen et al. Citation2016). The present study aims to fill these deficits in understanding. Additionally, we will test whether young women are more vulnerable to precariousness in entry-stage employment and thereby less successfully integrated into the labour market. We assume precariousness to be a gendered phenomenon because of processes of family formation, gender segregation and wage discrimination.

The study uses data from the German Socio-Economic-Panel (GSOEP 1993–2012) to analyse young people’s entry-stage employment trajectories. The focus is on men and women in Germany who were between 15 and 25 years of age at the start of the two ten-year sample periods.Footnote2 We chose Germany for our analyses because its heavily regulated vocational education and training system (dual system) provides apprentices with vocation-specific and highly standardized skills, which strongly improve their chances of entering skilled positions (e.g. Müller and Shavit Citation1998). Precariousness in entry-stage employment thus stands out and is easily identifiable. This ensures reliable results. The data set provides the information necessary to measure precariousness at the entry stage of employment careers. A longitudinal sequence-analyses approach enables us to analyse entry-stage employment trajectories rather than treating labour market entry as a single event (Brzinsky-Fay Citation2014). This approach also allows for the identification of successful transitions into continuous employment and episodes of precarious employment. Dual-channel sequence-cluster analysis provides the statistical tools necessary to integrate individual employment trajectories and household trajectories. In the next section, we will define precariousness and present our theoretical considerations about successful labour market integration and precariousness during the entry stage of employment.

2. Theoretical considerations on precariousness and entry-stage employment and their empirical application

The integration into the labour market starts with a crucial phase in young people's lives: their entry-stage employment. The success of entry-stage employment determines young people’s subsequent transitions and hence their careers (Luijkx and Wolbers Citation2009, 655; Nilsen and Reiso Citation2014, 15). Owing to Germany’s strong vocational education and training system, international comparisons typically find remarkably linear transitions into employment (Müller and Shavit Citation1998; Konietzka Citation2002; Brzinsky-Fay Citation2007; De Lange, Gesthuizen, and Wolbers Citation2014). Nonetheless, as job uncertainty has increased and labour market structures have changed, entry-stage employment patterns in Germany have become more and more diversified (Brzinsky-Fay and Solga Citation2016) and risky in terms of unemployment (Schoon and Lyons-Amos Citation2016, 17).

The school-to-work transition literature usually differentiated between short and smooth transitions into employment and fragmentary and disruptive ones. While short and smooth transitions into continuous employment were regarded as the gold standard in Western industrialized economies, deviations were not necessarily problematic. Detours or delays might have represented a necessary moratorium, when young people obtained additional qualifications or productively filled their time with paid employment or volunteer work until they gained access to their preferred university course, apprenticeship or job (Brzinsky-Fay Citation2007, 417; Baas and Philipps, Citation2017: 10f.). Only if trajectories became aimless – i.e. when they never seem to lead into continuous employment – was the transition considered a failure because it increased the risk of repeated or long-term unemployment (Baas and Philipps Citation2017, 16).

Consequently, researchers have introduced measures to quantify and analyse the quality of entry-stage employment (Brzinsky-Fay Citation2007). Brzinsky-Fay examined status sequences at labour market entry for young people across Europe, introducing sequence cluster analysis and two novel indicators: volatility and integration. Integration indicates how quickly and to what extent young people enter employment (Brzinsky-Fay Citation2007, 411). Volatility captures any kind of work experience or qualification that was relevant for getting access to continuous employment. Therefore, volatility is a measure of young people’s labour market readiness. It also indicates the flexibility of the transition sequences because it includes various forms of work experience (Brzinsky-Fay Citation2007, 411, 414).

Precariousness refers to a risky or hazardous lack of security or stability (Castel Citation2000; Kraemer Citation2008; Vosko, MacDonald, and Campbell Citation2009, 1; Standing Citation2011, 10). Precarious employment refers to various kinds of paid work that generates or reinforces social fractures and inequalities and challenges not only workers but also their households and communities.Footnote3 Precariousness has its roots in the deregulation of employment systems, the reform of the welfare state and the exclusion of whole population segments from secure employment and related social networks (Castel Citation2000). Young people are especially vulnerable to employment risks when they enter the labour market. They do not possess job experience, they are not yet entitled to social security protection and they lack the protection of an (internal) business network. Consequently, employers can take advantage of their limited negotiating powers and devolve risks to them (Buchholz et al. Citation2008, 57). However, successfully integrating young people into society requires securely integrating them into the labour market. Hence, labour market participation, security and integration do not necessarily occur at the same time.

Precariousness has never before been analysed in combination with labour market integration in the context of entry-stage employment trajectories. The following literature review will show the importance of precariousness and successful labour market integration for young people’s entry stage employment.

2.1. Integrational power and volatility

To date, precariousness and the quality of entry-stage employment have not been conceptually combined or used together. Despite this, we bring both together empirically. However, as the following literature review will show, there is little overlap in both research strands.

Studies on the success of labour market transitions show that the measures of volatility and integration can usefully be applied to a variety of transitions. Brzinsky-Fay (Citation2007) was the first researcher who quantified labour market integration using volatility and integration measures (see previous chapter). Since their introduction, these measures of volatility and integration have been used in various studies to assess the integrative capability of transition sequences (Simonson, Gordo, and Titova Citation2011; Bussi Citation2016; Pedersen et al. Citation2016). Simonson, Gordo, and Titova (Citation2011) revealed an increase in diversification for German female baby boomers’ employment careers (Simonson, Gordo, and Titova Citation2011, 73). Bussi (Citation2016) investigated whether activation policies reduce young people’s risk of unemployment or social assistance spells in their early employment trajectories but did not find compensation effects. Pedersen et al. (Citation2016, 3f.) examined the differences in the rates of the return to work between individuals on sick leave for mental health reasons versus other health reasons and found the following: individuals with mental health conditions showed significantly lower degrees of volatility and integration than individuals with other illnesses. This means that these individuals had fewer opportunities to gather the experiences or knowledge relevant for continuous future employment and often experienced interruptions in their employment (Pedersen et al. Citation2016, 5).

These two indicators capture people’s labour market readiness (volatility) and rootedness in the labour market (integration) (Brzinsky-Fay Citation2007; Bussi Citation2016; Pedersen et al. Citation2016). High degrees of volatility and Integration are linked, on the one hand, to advantages for employees; they allow them to avail of further education and training, to build professional networks, and to access firm-internal career ladders with improved job security and access to seniority entitlements. On the other hand, low degrees of volatility and integration are linked to disadvantages due to employment instability and a lack of legal protection. Young people in highly unstable employment relationships will often face repeated spells of unemployment. Employees who are not entitled to employment protection might also lose their jobs more often, too. However, other facets of precarious employment, like long-term health risks or low wages, might not be captured at all.

2.2. Precariousness

Precariousness is often defined as employment that fails to provide employees with a secure minimum standard of living (Vosko, MacDonald, and Campbell Citation2009; Olsthoorn Citation2014, 423). Especially in transition studies, the most common indicator for precarious employment has been non-standard employment (e.g. Büchtemann and Quack Citation1990; Kurz, Steinhage, and Golsch Citation2005; Kalleberg Citation2009; Baron Citation2015; Brzinsky-Fay, Ebner, and Seibert Citation2016). However, this definition is insufficient, because standard employment relationships can deviate from socially defined minimum standards in various ways and non-standard employment relationships may not always be precarious. Consequently, some authors have demanded a generalization of the concept of precariousness (Rodgers Citation1989; Vosko, MacDonald, and Campbell Citation2009; Olsthoorn Citation2014). Rodgers (Citation1989), Vosko, MacDonald, and Campbell (Citation2009) and Olsthoorn (Citation2014) agreed on defining precariousness as an accumulation of factors indicating precariousness. On this basis, Olsthoorn (Citation2014, 422 f.) defined employment precariousness as a state of threatened insecurity consisting of several factors on the employment level (low income), the individual level (having an insecure job) and the institutional level (lack of entitlements that provide income security) (cf. Vosko, MacDonald, and Campbell Citation2009). We explain these factors in detail below.

Low-wage employment jeopardizes people’s security because low wages were associated with inferior working conditions and an inability to maintain basic needs and a safe and decent standard of living; they were also a precursor to old-age poverty (e.g. Brinkmann et al. Citation2006; Vosko, MacDonald, and Campbell Citation2009; Weinkopf Citation2009; Standing Citation2011; Vono de Vilhena et al. Citation2016). Precariousness may also entail employment lacking legal protection. Some employees lacked legal protection because they were not entitled to social security protection (e.g. Brinkmann et al. Citation2006, 18; Cranford and Vosko Citation2006; Vosko and Clark Citation2009) or because they were exempted from employment protection legislation (e.g. Vosko, MacDonald, and Campbell Citation2009). Employees without social security were not entitled to access unemployment benefits and old-age pensions; if they were exempted from employment protection legislation, they faced increased unemployment risks. Finally, employment instability threatened employees’ societal integration, their status and their class. Individuals faced increased employment instability because they were working in the secondary labour market (high turnover). Individuals’ occupations also faced major challenges due to technological changes (automation or digitalization) that caused imbalances in the occupation-specific labour demand and supply (e.g. Sengenberger Citation1978; Stuth Citation2017). Precarious employment also jeopardized people’s security if it involves demanding physical working conditions, which prompted them to drop out of the labour force early due to ill-health (e.g. Tophoven and Tisch Citation2016). Physical work caused serious health risks for employees if it featured heavy work, repetitive activities or forced static postures. We follow these authors and develop a multidimensional approach to identify precarious employment, using indicators for low wages, lack of legal protection and employment instability.

We will also consider households when analyzing the quality of young people’s entry-stage employment trajectories, because precarious employment is closely linked to employees’ households (Kraemer Citation2008; Clement et al. Citation2009). Living conditions in young people’s parental or own households either mitigated young people’s precariousness or exacerbated it depending on the resources households provide: The question was whether the provided resources are (in-)sufficient to enter better jobs or further education (Bourdieu Citation1997; Piore Citation1975; Kraemer Citation2008, 82–83; Clement et al. Citation2009, 243–245; Vosko and Clark Citation2009). Poor household resources manifest through a critical housing or financial situation, special (care) burdens or lack of legal protection. A critical housing situation involved living in a substandard dwelling, which negatively affected young people’s everyday life, educational efforts and careers (Bourdieu Citation1997; Groh-Samberg Citation2004). The financial situation of a household added to young people’s precariousness, even if they were securely employed – for instance, if they lived in large households or had many children (e.g. Strengmann-Kuhn Citation2001; Groh-Samberg Citation2004). Consequently, they were unable to save money for unexpected and expensive events (e.g. dental implants or crowns, replacing broken appliances or moving house). Financial debt was a problem if mortgage and interest payments consumed a large proportion of household income, which was otherwise sufficient to cover living costs. Households were at risk of precariousness when their members faced extensive care responsibilities for disabled family members, because these responsibilities constrained individuals’ choices on the labour market (Clement et al. Citation2009; Vosko and Clark Citation2009). The German welfare state protects against various risks including ill health, unemployment, old age, divorce and the death of a partner. Support in the case of separation or a partner’s death is only available for married couples, whereas protection against unemployment and old age is available only for individuals in jobs with social security contributions. Households whose members were neither protected by social security nor by marital status were inadequately protected against risks and are thereby exposed to precariousness. Thus, the (lack of) household resources should be associated with the quality of entry-stage employment trajectories.

2.3. Assumptions for the empirical analysis

Based on these theoretical considerations and the literature review, we dispute the assumption that any transition into continuous employment is a success. Our first two hypotheses test these integration assumptions.

H1: The more fragmented young people’s entry-stage employment trajectories the higher their risk of being precariously employed.

H2: Even if young people have continuous rather than fragmented entry-stage employment trajectories they are nevertheless at risk of being precariously employed.

We question the assumption that any kind of employment or education increases young people’s chances of obtaining secure employment because it increases their labour market readiness (volatility). Instead, we assume that employers perceive young people’s precarious employment episodes as non-relevant or even as a stigma (Solga Citation2002; Manzoni and Mooi-Reci Citation2011, 345).

H3: Young people’s precarious employment experiences do not increase their labour market readiness.

We also argued that households provide or lack the resources necessary for young people to engage in education that would improve their labour market readiness.

H4: Young people who continuously experience precariousness in their households have lower levels of labour market readiness.

We also expect to find gender differences. While men and women exhibit similar transitions into employment, they soon face gender-segregated labour markets and wage discrimination, especially when family formation starts. The terms motherhood wage penalty and fatherhood wage premium are common in the literature and emphasize these differences. Women who became mothers usually interrupted their employment and if they returned to their old jobs at all, they often only returned to working reduced hours (Grunow, Schulz, and Blossfeld Citation2007, 176). They thus faced significant wage losses when they re-entered the labour market (Gangl and Ziefle Citation2009, 356). These effects were stronger for low-wage women (Budig and Hodges Citation2014, 362). In contrast, young fathers faced no labour market interruptions and even experienced positive labour market consequences like higher wages (Boeckmann and Budig Citation2013, 13 ff.).

H5: Young women are less integrated and experience precarious entry-stage employment trajectories more often than young men.

3. Methods

Entry-stage employment trajectories do not consist of single events but sequences of events. Broad time frames and longitudinal methods of analysis are thus required to cover all varieties of entry-stage employment trajectories (e.g. Brzinsky-Fay Citation2014).

3.1. Data

The longitudinal data from the German Socio-Economic-Panel (GSOEP) provided us with information about individuals and households on a yearly basis. We analysed a period of ten years, which was long enough to identify distinctive employment trajectories but was still short enough to guarantee a sufficient number of observations (panel mortality). To check for period effects, we analysed two ten-year periods (1993–2002, 2003–2012) with fairly comparable economic conditions.Footnote4 The balanced panel included young men and women who were over the age of 15 but under 25 in the first year of the sample period. They had to be employed at least once during the observation period, had to participate in at least 9 out of ten survey years (unit non-response) and were allowed only one missing value in the variables necessary to measure precariousness (item non-response).Footnote5 This gave us a total sample size of 1,360 entry-stage employment trajectories of young men (N = 633) and women (N = 727).

3.2. Operationalization

Young people’s entry stage employment trajectories were differentiated according to the succession of states they entail regarding their (labour market) activity. Inactivity refers to episodes in which individuals were not in employment, education or training, and were not seeking employment. Episodes of childcare or vocational education and training, tertiary education or further education are classified as education or parental leave. Unemployment describes episodes in which individuals without employment were seeking work and were available for work. Employment refers to activities that are regulated by contracts, which usually involve wages (internships or work in family businesses are exceptions). We also included an unknown status, which refers to missing data.

To identify successful entry-stage employment trajectories, we followed two different strategies. First, we relied on Brzinsky-Fay’s (Citation2007) measures for integration and volatility. The integration measure is the ratio between the count of all episodes where a person is in employment and the maximum number of episodes in employment that are theoretically possible. Later employment episodes are given more weight than earlier employment episodes.E = In employment (1 = yes, 0 = no); Emax = constantly employed (1 = yes); t = Year of observation (year 1 to year 10)

By applying the square root, we convert the linear integration assumption into a saturated growth curve. The volatility measure is the ratio of episodes with employment experience, qualification or education and the overall number of years observed.

Second, we assessed the quality of entry-stage employment trajectories by measuring whether young people experienced precariousness.Footnote6 Precarious employment was characterized by low wages, lack of legal protection and employment instability was operationalized using seven indicators. Low wages were measured through low-wage employment and the living wage. Low-wage employment was identified in the data as employment with an hourly wage below two-thirds of the median threshold in Germany.Footnote7 Given that low wages have been offset by a high number of working hours, the living wage was also taken into account. The living wage was legally defined by the amount of yearly income that was necessary to maintain basic needs and a safe and decent standard of living. This indicator identifies individuals whose annual income has been below this legally defined threshold.Footnote8 A lack of legal protection was defined as an absence of social security protection, which was the case for specific jobs (unpaid work in family businesses), specific employment contracts (those held by individuals who are solely marginally employed or doing compulsory military service or compulsory community service) and (solo-)self-employment. Employees in very small businesses with less than five to ten employees also lacked legal protection because these businesses were exempted from employment protection legislation.Footnote9 Employment instability was measured using three indicators: unskilled work, unemployment risk and physical strain at work. Jobs were defined as unskilled if they did not require vocational qualifications or tertiary degrees. Young people’s unemployment risk was high in occupations with an above-average unemployment rate. The above-average unemployment rates of the occupations were based on our own calculations with the German microcensus (1993–2011, N = 4,445,545). Unhealthy physical working conditions were operationalized as those involving occupational physical strain measured through the Physical Exposure Index provided by Kroll (Citation2015). The index measured ergonomic strain like lifting heavy loads (construction or care sector) and potential hazards in the working environment like toxins.Footnote10 Employees were defined as working under unhealthy conditions if their occupations are in the ninth or tenth decile of the physical exposure index. The information about occupations with above-average unemployment rates or unhealthy working conditions were matched to the GSOEP using the 3-digit code of the German classification of occupations (KldB92).

Households sometimes threatened the security of its members through a critical housing or financial situation, special burdens or lack of legal protection, which were operationalized using seven indicators. Those included an absence of household amenities like running hot water, central heating or a bath and shower, which indicated low housing standards. Additionally, we regarded housing situations as critically if they provided insufficient space for all household members (less than one room per person). The households’ financial situation was measured using three indicators: poverty, no savings, and excessive debts. Households were poor if their equivalised disposable income was below 60 per cent of national median equivalised income. Households were without savings if they did not save at least 50 euros per month. Excessive debts were defined by households that spend more than 50 per cent of the equivalised monthly income on interest and mortgage payments. Households were regarded as having extensive care burdens if at least one member of the household was severely disabled. In terms of legal protection, a lack of social security protection was assumed when adult household members were not married and not in employment relationships that were subject to social security contributions.

3.3. Dual channel sequence cluster analysis

We used dual channel sequence cluster analysis to compare and group the young people’s entry-stage employment trajectories with regard to their successful labour market integration and the precariousness of their employment. The method of sequence cluster analysis originates in biology and was adopted in the social sciences in the 1980s. There it is commonly used to analyse categorical time series data such as transitions from school to work (Scherer Citation2001; Brzinsky-Fay Citation2007), life course research (Martin, Schoon, and Ross Citation2008) or family-life trajectories (Elzinga and Liefbroer Citation2007). The mechanism of optimal matching compares the order of states of each sequence with the others by generating a similarity measure used by the Ward algorithm to create groups. The algorithm thereby aims to minimize within-group difference, whereas between-group difference is maximized. The default cost structure was applied (insertions and deletions cost 1 and substitutions costs 2) and was cross checked with a cost structure determined by empirical transition rates. Both cluster solutions were comparable, with only marginal differences in the number of individuals per cluster. The optimal number of clusters was chosen regarding content and quality measures of different partitions.Footnote11

This method does not work with continuous measures but requires a limited number of states (for example inactivity, unemployment or employment). Therefore, we summarized the information on precariousness into a dichotomous variable. As argued above (section 2.1) precariousness consists of an accumulation of precarious factors. Therefore, we classified employment episodes as secure if zero or one of our seven indicators were true. Employment episodes were coded as precarious if two or more variables indicated precariousness. The same coding applied to the young people’s households (parental or own). We integrated employment and household information into one model using dual channel analysis. In this method, sequences are also clustered according to similarity on a second level of sequences, the household context in this case (e.g. Schels Citation2013). Because we expected to find gender differences, we stratified our analyses by gender to identify entry-stage employment trajectories that were specific for men or women only.Footnote12

4. Results

The sequence cluster analysis of young people’s entry-stage employment trajectories and their corresponding household trajectories produced six distinct clusters each for the men and women. The clusters represent different entry-stage employment trajectories, including successful transitions into permanent secure employment, long-term entrapment in precariousness, a return to education and other trajectories.

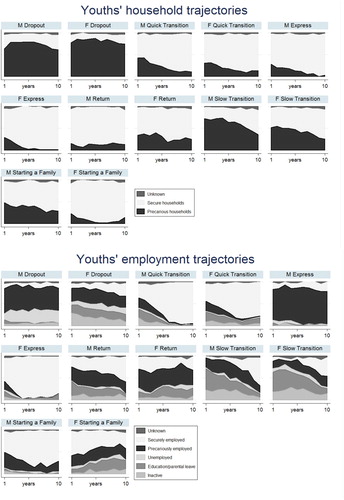

and show that these entry-stage employment trajectories are comparable between men and women. Hence, we present the trajectories of young men and women in gender pairings. Despite the similarity of the employment trajectories, one cluster pair is distinctly different between the sexes with regard to the employment precariousness – the express cluster.

Figure 1. Status proportion plots of young people’s employment trajectories and household trajectories. Source: SOEPlong 1993–2012; own calculations.

Note: (M) represents male clusters and (F) female clusters.

Table 1. Cluster descriptions of the individual and household trajectories.

4.1. Entry-stage employment and household trajectories

The following sections briefly describe young people’s entry-stage employment and household trajectories with regard to their success using the measures of integration and volatility, young people’s education and qualifications, the extent and forms of precariousness experienced at the individual and household level, and household composition.Footnote13 Our cluster names resemble those given by Sackmann and Wingen’s (Citation2003) and Brzinsky-Fay’s (Citation2007). However, similar cluster names do not imply similar content, because of differences in the research design (e.g. we do not choose school as a starting point for our analyses and consider far longer periods of time). The reported values in the following paragraphs represent averages for the men or women in these clusters.

The first cluster – dropout – has the lowest values on the integration and volatility measure () and has a large share of individuals who remained without any vocational qualifications throughout the observation period.Footnote14 44 per cent of men and 44 per cent of women had no vocational qualification at the outset, while 40 per cent of men and 28 per cent of women remained without one at the close. Individuals in this cluster typically experienced long stretches of precarious employment (five years for men, three years for women) and had numerous employment interruptions (men were unemployed for 3.6 years and women for 1.2 years). Unskilled work and yearly incomes below the living wage threshold were the main indicators for precarious employment found among men and women in these clusters. Further indicators for precarious employment included physical strain for men and low wage employment for women. The predominant indicators for precariousness at the household level included no savings, no social security protection and poverty. Overall, individuals lived in highly precarious households for long stretches of time (6.4 years men, 7.5 years women). The young men and women on average lived approximately 4.5 years with a partner, although these partners were often also precariously employed or unemployed.

The quick transition cluster has high values on integration and volatility (). The young people in this cluster rapidly succeeded in obtaining secure employment after completing their education. Individuals in this cluster did not experience a large degree of precariousness. Many already worked in secure jobs at the start of the observation period or entered into secure jobs after a brief period of precarious employment (0.9 years men, 1.1 years women). The most prevalent forms of precariousness in this group were combinations of yearly income below the living wage threshold, unskilled work, lack of social security protection and lack of household savings. The households provided security for a long duration of nearly seven years (men) or nearly eight years (women). Households included a partner who was securely employed (men lived with a partner for 3.6 years, while women lived with a partner for 5.4 years). When we look at previous research, this cluster resembles the smooth, standard transition into employment described therein, a feature usually related to Germany’s apprenticeship system (Brzinsky-Fay Citation2007).

The express cluster describes a rapid entry-stage employment trajectory, where statuses other than employment are rare. This trajectory has the highest values on integration and volatility for both men and women (). Two thirds of the men and half of the women entered the observation period with a vocational qualification. Two thirds of the women even had an A-level-type qualification (Abitur). However, the quality of employment differs strongly between the sexes. Young men experienced long periods of precariousness (7.8 years) due to a high occupation-specific unemployment risk and high levels of physical strain. The women enjoyed continuously secure employment (8.5 years) and lived, like their male counterparts, in secure households for nearly nine years. The young people shared their homes with a partner for a moderate amount of time (men: 3.8 years, women: 4.5 years). The partners were mainly securely employed.

The return cluster describes entry-stage employment trajectories that include detours back into education to escape precarious employment by attaining qualifications. These trajectories had a moderate value on integration and a high value on volatility. Nearly half of the men in these clusters and a tenth of the women in this cluster entered the observation period without any vocational qualifications or university degrees, but most re-entered education. At the end of the observation period 37 per cent of women and 18 per cent of the men remained in education. Both men and women experienced a moderate level of precariousness, with men spending 3.4 years and women 3.2 years on average in precarious employment. Men and women spent an equal amount of time in secure employment (3.8 years for men, 4 years for women). Precarious employment mainly took the form of unskilled work and physical strain for men and yearly income below the living wage threshold and unskilled work for women. The households were able to compensate for precarious employment, with men living in secure households for 8.6 years and women living in security for 6.8 years. Household precariousness consisted of a lack of household savings and social security protection. Women cohabited for nearly half of the observation period (4.8 years), sometimes with precariously employed partners, whereas men only spent one third of the observation period with a partner, who was often unemployed.

The slow transition cluster represents men and women who remained in education for a long time and thereby experienced a relatively late transition into secure employment. The young men and women entered the observation period during their academic education or vocational training and had low values on integration and volatility. By the end, one third of the men and nearly one third of the women had yet to complete their education and training. On average, men and women spent roughly equal amounts of time in secure and precarious employment (about 2.8 years for men, 2 years for women). Transitions into secure employment increased strongly in the last quarter of the observation period, when young people started to finish their vocational training or academic education. The predominant forms of precariousness included unskilled work and a yearly income below the living wage threshold. Households were able to compensate for individual insecurity to some extent, with men living in security for more than four years and women for more than six years. Precariousness at the household level varied across gender. While both men and women lacked social security protection and were unable to save money, men often lived with a disabled household member. The large majority of men lived alone throughout most of the observation period, whereas women lived nearly 5 years with a securely employed partner.

The starting a family cluster comprises individuals whose personal and familial circumstances affected their exposure to precariousness in a significant way. Women paused work or education to have a child. Men in this cluster cohabited longest compared to those in other clusters and also started to have families. Even though 43 per cent of men in this cluster remained childless until the end of the observation period, the rate of married men raises from eight to 64 percent, indicating the start of a family. The values on the integration and volatility measures are generally very high, yet women had a very low value on the integration measure because of their parental leave (). The educational trajectories of men and women in these clusters also differ. Only one third of men, compared to two thirds of women, entered the observation period with a vocational qualification. At the end, 81 per cent of men and 88 per cent of women had acquired such a qualification. While exposure to precarious conditions was low for both men and women in these clusters, women experienced precariousness more often. Men worked in secure employment for seven years and when they experienced precarious working conditions, it was usually physical strain or unskilled work. Women worked in secure employment for 3.8 years, in precarious employment for 2.6 years and were on parental leave for 2.1 years. The predominant forms of precariousness experienced by these women included a yearly income below the living wage threshold and unskilled work. Women’s households provided secure conditions for almost nine years. Men lived in secure households for six years. In no other cluster was the share of married men and women so high: two thirds of the men and three quarters of the women were married. Young women lived with securely employed partners for eight years. Men cohabited for more than five years with a partner, who was often unemployed or precariously employed.

These employment trajectories also differ in how they relate to career success. Looking at the magnitude prestige score of the young men’s and women’s occupations in the last year of the observation period we found the highest prestige scores in in entry-stage employment trajectories that were part of the quick transition cluster, the slow transition cluster or the female express cluster. Footnote15 The lowest prestige scores were found for young men who were part of the dropout cluster or the express cluster. Young people in the dropout cluster, the return cluster to education and starting a family cluster had significantly lower prestige scores than their peers in the quick transition or slow transition cluster.Footnote16

4.2. Testing the hypotheses

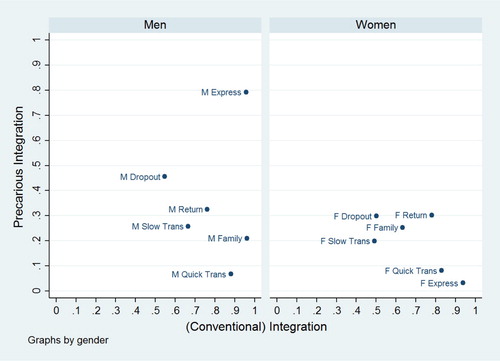

We expected young people with fragmented or even disrupted trajectories to be at a high risk of precarious employment (H1). We also expected to observe continuous entry-stage trajectories that were also precarious (H2). To test these hypotheses, we used a scatter plot with the conventional integration measure, as described above, on the x-axis and an alternate version of the integration measure on the y-axis. The alternate integration measure reflects only ‘integration’ into precarious employment and is thereby described as precarious integration.

shows that the H1 assumption seemed to be correct for young women. Fragmented and disrupted entry-stage employment trajectories were captured by the conventional integration measure whereas precarious employment was captured by the precarious integration measure. We found the expected association between low values on precarious integration and high values on conventional integration for young women (r=-0.67). For young men, this relationship was nearly zero (r=-0.05). However, both correlation coefficients remained below the five percent statistical significance threshold (young men p = 0.9, young women p = 0.1). Hence, we had to reject H1: Even though we found the expected pattern for the young women in our sample, the association between fragmented career trajectories and precarious employment is not as clear cut as we had expected. We found one male entry-stage employment trajectory (Express) that consisted solely of continuous employment that was permanently precarious. Hence, H2 is correct for some young men.

Figure 2. The association between young people’s integration and precarious employment. Source: SOEPlong 1993-2012; own calculations.

Note: (M) stands for male clusters and (F) for female clusters.

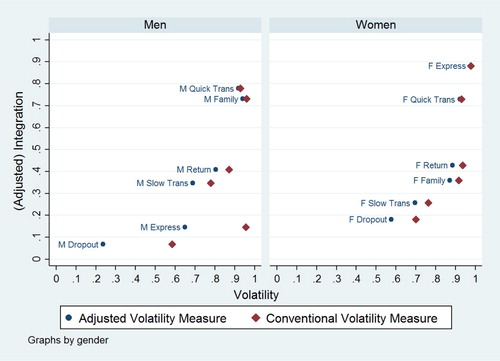

To test whether precarious employment experiences increase young people’s labour market readiness or not (H3), we adjusted the integration measure, accounting only for non-precarious employment episodes. This allowed us to observe whether labour market readiness translates into continuous and non-precarious employment. shows a scatter plot with volatility on the x-axis and the adjusted integration measure on the y-axis. Using the conventional volatility measure, we found that more employment experience and more time in education and training were associated with non-precarious labour market integration (young men r = 0.61 and young women r = 0.81). However, the association was only statistically significant for the young women (p = 0.05) but not for young men (p = 0.2). This association remained remarkably unchanged for women (r = 0.85) when we deducted precarious employment experience from the measure for labour market readiness (adjusted volatility). However, the association between employment experience, education and training, and young men’s non-precarious labour market integration increased substantially when we used the adjusted volatility measure without precarious employment experiences (r = 0.87). By doing so, the association became statistically significant for the young men (p = 0.02) and remained significant for the young women (p = 0.03). Young men’s precarious employment experiences did not significantly increase their chances of becoming continuously and non-precariously employed, even though we observed a long period of ten years.

Figure 3. The association between young people’s integration and volatility. Source: SOEPlong 1993-2012; own calculations.

Note: (M) stands for male clusters and (F) for female clusters.

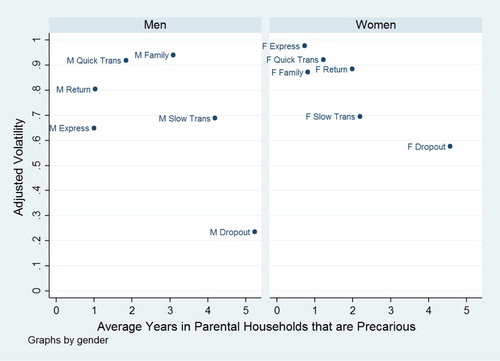

We expected young people who continuously experienced precariousness in their households to show lower levels of labour market readiness (H4). When testing this hypothesis, we only considered young people as long as they lived in their parental households. This allowed us to avoid confusion about the direction of the assumed association between labour market readiness and precarious households, which might be distorted when young people set up their own households. shows the adjusted volatility measure on the y-axis and the average number of years that young people spent living with their parents in precarious households. We found an expected but statistically non-significant association between precarious households and volatility for young women (r = -0.7, p = 0.1): more years in precarious parental households coincide with lower degrees of labour market readiness. Young men, by contrast, showed an inverted u-shaped association rather than a linear one (r = −0.2, p = 0.7). Both the experience of very short and very long spells in precarious households led to lower degrees oflabour market readiness.

Figure 4. The association between young people's volatility and average years in precarious parental householdsSource: SOEPlong 1993-2012; own calculations.

Note: (M) stands for male clusters and (F) for female clusters.

In H5, we expected to find gender differences: We assumed that young women’s need to reconcile work and family life, gender segregated labour markets and wage discrimination might render their employment trajectories more vulnerable to precarious employment. Yet even though we found gender differences, it is the young men who are more vulnerable to precarious employment. The male express cluster was continuously employed but this employment was precarious. Young men’s employment experiences especially in in the express and in the dropout cluster were not associated with successful and non-precarious labour market integration. For young women on the other hand the difference between precarious and non-precarious employment experiences is negligible with regard to successful and non-precarious labour market integration. Hence, H5 has to be rejected.

4.3. Changes between periods

In order to identify period effects, we divided the data set into two balanced panels from 1993 to 2002 and from 2003 to 2012. This design was intended as a robustness check against changes in the patterns of precarious employment and precarious living conditions between the two ten-year periods due to institutional changes, globalization and technological developments. The number of observations was too small to provide reliable comparisons between clusters and periods. However, it was possible to analyse general changes for young men and women. We did find an increase in precarious employment for young men (the share of precarious employment episodes increased by 10 percentage points) between the periods and a small decrease for young women (the share of precarious employment episodes decreased by 3 percentage points). Precarious household episodes increased by 6 percentage points for the men and remained unchanged for women.

5. Summary and Conclusions

This article provided a comprehensive analysis of the success of young people’s entry-stage employment trajectories in Germany by developing and applying a new multidimensional measure for precarious employment and precarious households. Dual-channel sequence-cluster analysis showed that young people’s first employment experiences varied considerably, from smooth, standard transitions to transitions with detours and disruptions. This is in line with previous research. Extending the previous research, we asked whether the transition into continuous employment is the hallmark of a successful entry-stage employment trajectory. To answer the question, we included the concept of precariousness in our analyses. Our results show that some employment trajectories, like the male express cluster, entail continuous precariousness, while others show continuous employment with almost no precariousness at all (e.g. the quick transition or the female express cluster). The slow transition and return cluster show that educational activities by young men and women are often accompanied by precarious employment. However, the quick transition and the female express cluster suggest that after acquiring qualifications or degrees, employment becomes secure.

The dual-channel perspective allowed us to include the household situation for the observed period of time. The young people in the quick transition, express and return clusters lived in secure households. Individuals in the slow transition cluster lived in precarious households for many years. We only find one cluster where young adults simultaneously lived in precarious households and experienced precarious employment for many years (dropout). Additional analyses revealed that starting a family increases the risk of precariousness at both the employment and household level for many years (Allmendinger et al. Citation2018; Stuth et al. Citation2018).

The majority of the employment trajectories show no gender differences. However, allowing for precariousness in entry-stage employment trajectories reveals big gender differences. Contrary to our expectation that women would be more vulnerable to precariousness because of processes of family formation, gender segregation and wage discrimination, it is the young men who suffered most from precarious employment. This becomes manifest in the gender-specific versions of the express cluster. For young males, the cluster describes an employment trajectory that consists of continuous but precarious employment, whereas the same cluster for young women entailed continuous and secure employment. We also find that not every kind of employment experience increases labour market readiness. In two clusters in particular (express and dropout) young men experienced extended periods of precarious employment that did not translate into successful (non-precarious and continuous) employment trajectories. This finding was only true for men. The women in our sample generally experienced less extended periods of precarious employment. For those who did experience longer periods, (precarious) employment nevertheless increased labour market readiness. We also found gender differences in the association between labour market readiness and the precariousness of young people’s parental households. We found a linear but statistically nonsignificant negative association between the duration young women lived in precarious parental households and their labour market readiness. For young men, the association was curvilinear: both short spells of household precariousness and long spells of household precariousness are negatively associated with their labour market readiness. Precariousness also changes in its incidence over time: we observe that men experienced more precariousness in the second than in the first period, whereas the situation remained unchanged or slightly improved for young women.

We aimed at measuring the success of young people’s entry-stage employment trajectories. We compared the level of integration and volatility with the degree of precariousness experienced by young people between the different employment trajectories. This allowed us to assess the general association between integration/volatility and precariousness. Our results show that the association between fragmented career trajectories and precarious employment is not as clear cut as we had expected. However, even though the conventional measures were not perfect, they were fairly robust in capturing women’s entry-stage employment trajectories. But we have shown that these measures do not work well with regard to young men’s entry-stage employment. This is specifically the case for the integration measure and young men who are continuously but precariously employed (express). Labour market readiness should also focus on secure employment episodes and exclude precarious employment experiences because the latter do not positively helped young men to find continuous and non-precarious jobs in the long run. To avoid misclassifying precarious entry-stage employment trajectories as success, we recommend that researchers adjust how they calculate success measures like the integration and volatility measures by accounting only for non-precarious employment episodes.

The young men and women in the dropout cluster and their precarious household situation give cause for concern, because they were continuously trapped in precarious employment and precarious households. On one hand, it is unlikely that their household situation will improve because of the precarious nature of their employment. On the other hand, their chances of improving their labour market readiness through vocational education and training are low, because of their precarious living conditions. Additional education and training programmes provided by the German employment agency might help to improve their position in the labour market, but they will only be fruitful if precarious living conditions are also addressed. Only if young persons’ basic needs are met and the various deprivations and resource deficits are addressed might these individuals have a realistic chance of finally finishing an education or training program and acquiring qualifications, which help them to advance to secure jobs. As for the young men in the express cluster, even though they have mostly acquired vocational qualifications and enjoyed secure living conditions, they were nevertheless trapped in precarious employment. Sooner or later, they will have to change their occupation, because their precariousness mainly stemmed from risks of occupation-specific unemployment and occupation-specific physical strain that are high. Labour market policy should thus aim at creating institutionalized bridges to enable these people to move into jobs that are not precarious. Such a bridge could, for example, consist in establishing virtual education accounts that provide the necessary funds to learn a new occupation in prime working age. Such institutionalized bridges are important in an occupational labour market, because most occupations require an occupation specific credential as a primary entry prerequisite and without it the risk of precarious employment is very high (Stuth et al. Citation2018, 45).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jutta Allmendinger, Markus Promberger and Brigitte Schels for detailed and insightful comments, which were invaluable in the development of this article. We also thank the Hans Böckler Foundation for funding our research on the important topic of precarious employment and precarious living conditions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 We consider parental households as long as young people live with their parents and we switch to young people’s own households once they move.

2 We configure two sample periods: 1993–2002 and 2003–2012 in order to control for period effects (see ‘Methods’)

3 For a comprehensive review on the use of the term precariousness and its various definitions see Vosko, MacDonald, and Campbell (Citation2009).

4 The small sample size does not allow us to include this feature in our analyses. Instead we had to pool the data of both periods. However, robustness checks revealed no substantial differences in the young people’s entry-stage employment trajectories between the periods.

5 Employment includes situations like internships, working students, (compulsory) community service etc.

6 A detailed description of all indicators used to identify precariousness can be found in Stuth et al. (Citation2018).

7 We calculated the two-thirds threshold on a yearly basis in order to account for time-sensitive effects. The median threshold was also measured separately for the old and new German Länder because the wage level differs between both parts of Germany for historical reasons. For example, the two-thirds threshold in 1993 amounted to 7.24 euros for people in West Germany and 4.16 euros in East Germany.

8 A reference for the yearly thresholds can be found in Allmendinger et al. (Citation2018) or Stuth et al. (Citation2018).

9 The law concerning the Kleinbetriebsklausel changed in 2004. Before 2004 organizations were defined as small if they had less than five full-time equivalent employees. For 2004 and onwards organizations were defined as small if they had less than ten full-time equivalent employees.

10 Kroll’s physical exposure index integrates two dimensions of work strain into one measure: ergonomic strain and potential hazards like toxins or climatic stresses (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.67). The index is standardized from 0 to 100 and summarizes the occurrence of physical exposure. The largest burdens are on males in the construction industry and on females in the catering and hotel industry (Kroll Citation2011, 66ff.).

11 ASW, HGSD and PBC were used as quality measures (Studer Citation2013).

12 A table with the description of the distribution of young men and women across the different states within the ten-year periods is provided in the online appendix.

13 The descriptions of the clusters include a number of additional indicators and variables that are operationalized as follows: partners are only considered if they live in the same household. Individuals are counted as married if they were married at least once in the ten-year observation period. Childlessness is measured at the end of the observation period. Age is measured at the beginning of the observation period. The cluster size is gender specific. A value of 15 per cent means that this cluster includes 15 per cent of the male/female population. All statistics we used to describe the clusters and the ANOVA were weighted using panel weights.

14 Tables with descriptive statistics on the clusters are provided in the online appendix. This includes information about the indicators of precariousness, the young people’s educational background, sociodemographics and type and composition of the households.

15 The magnitude prestige score is based on occupational reputation.

16 Oneway ANOVAs with Bonferroni correction show statistically significant differences between the clustered employment trajectories and the magnitude prestige score. Tables with detailed ANOVA results and multiple-group comparisons are provided in the online appendix.

References

- Allmendinger, J., K. Jahn, M. Promberger, B. Schels, and S. Stuth. 2018. “Prekäre Beschäftigung und Unsichere Haushaltslagen im Lebensverlauf: Gibt es in Deutschland ein Verfestigtes Prekariat?” WSI Mitteilungen 71 (4): 259–269.

- Baas, M., and V. Philipps. 2017. “Über Ausbildung in Arbeit? Verläufe gering gebildeter Jugendlicher.” In Berichterstattung zursozioökonomischen Entwicklung in Deutschland: Exklusive Teilhabe – ungenutzte Chancen, edited by Sozialwissenschaftliche Berichterstattung Forschungsverbund, 1–36. Bielefeld: Bertelsmann.

- Baron, D. 2015. “Objective vs. Subjective Precarity and the Problem of Family Institutionalization. Theoretical Approaches and Empirical Insights.” AGIPEB Working Paper 4: 1–47.

- Beck, U. 1992. Risk Society. London: Sage.

- Boeckmann, I., and M. Budig. 2013. Fatherhood, intra-household employment dynamics, and men's earnings in a cross-national perspective. LIS Working Paper Series No. 592: 1–26.

- Bourdieu, P. 1997. Das Elend der Welt. Zeugnisse und Diagnosen alltäglichen Leidens an der Gesellschaft. Konstanz: Universitätsverlag Konstanz.

- Brinkmann, U., K. Dörre, S. Röbenack, K. Kraemer, and F. Speidel. 2006. Prekäre Arbeit: Ursachen, Ausmaß, soziale Folgen und subjektive Verarbeitungsformen unsicherer Beschäftigungsverhältnisse. Bonn: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung.

- Brzinsky-Fay, C. 2007. “Lost in Transition? Labour Market Entry Sequences of School Leavers in Europe.” European Sociological Review 23 (4): 409–422.

- Brzinsky-Fay, C. 2014. “The Measurement of School-to-Work Transitions as Processes.” European Societies 16 (2): 213–232.

- Brzinsky-Fay, C., C. Ebner, and H. Seibert. 2016. “Veränderte Kontinuität: Berufseinstiegsverläufe von Ausbildungsabsolventen in Westdeutschland seit den 1980er Jahren.” Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 68 (2): 229–258.

- Brzinsky-Fay, C., and H. Solga. 2016. “Compressed, Postponed, or Disadvantaged? School-to-Work-Transition Patterns and Early Occupational Attainment in West Germany.” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 46 (2016): 21–36.

- Buchholz, S., D. Hofäcker, M. Mills, H. P. Blossfeld, K. Kurz, and H. Hofmeister. 2008. “Life Courses in the Globalization Process: The Development of Social Inequalities in Modern Societies.” European Sociological Review 25 (1): 53–71.

- Büchtemann, C. F., and S. Quack. 1990. “How Precarious is ‘non-Standard’ Employment? Evidence for West Germany.” Cambridge Journal of Economics 14 (3): 315–329.

- Budig, M. J., and M. J. Hodges. 2014. “Statistical Models and Empirical Evidence for Differences in the Motherhood Penalty Across the Earnings Distribution.” American Sociological Review 79 (2): 358–364.

- Bukodi, E., E. Ebralidze, P. Schmelzer, and H. P. Blossfeld. 2008. “Struggling to Become an Insider: Does Increasing Flexibility at Labor Market Entry Affect Early Careers? A Theoretical Framework.” In Young Workers, Globalization and the Labor Market: Comparing Early Working Life in Eleven Countries, edited by H. P. Blossfeld, S. Buchholz, E. Bukodi, and K. Kurz, 3–27. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Bussi, M. 2016. “Transitions, Trajectories and the Role of Activation Policies for Young People.” In Proceedings of the International Conference on Sequence Analysis and Related Methods (LaCOSA II), edited by G. Ritschard and M. Studer, 129–141. Lausanne.

- Castel, R. 2000. Die Metamorphosen der sozialen Frage. Eine Chronik der Lohnarbeit. Konstanz: Univ. Verl.

- Clement, W., S. Mathieu, S. Prus, and E. Uckardesler. 2009. “Precarious Lives in the New Economy: Comparative Intersectional Analysis.” In Gender and the Contours of Precarious Employment, edited by L. F. Vosko, M. MacDonald, and I. Campbell, 240–255. New York: Routledge.

- Cranford, C. J., and L. F. Vosko. 2006. “Conceptualizing Precarious Employment: Mapping Wage Work Across Social Location and Occupational Context.” In Precarious Employment: Understanding Labour Market Insecurity in Canada, edited by L. F. Vosko, 43–66. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press.

- De Lange, M., M. Gesthuizen, and M. H. Wolbers. 2014. “Youth Labour Market Integration Across Europe.” European Societies 16 (2): 194–212.

- Dörre, K. 2006. “Prekäre Arbeit - Unsichere Beschäftigungsverhältnisse und ihre sozialen Folgen.” Arbeit 15 (3): 181–193.

- Elzinga, C. H., and A. C. Liefbroer. 2007. “De-standardization of Family-Life Trajectories of Young Adults: A Cross-National Comparison Using Sequence Analysis.” European Journal of Population / Revue Européenne de Démographie 23 (3): 225–250.

- Frade, C., I. Darmon, and M. Laparra. 2004. Precarious Employment in Europe: A Comparative Study of Labour Market Related Risk in Flexible Economies. Final Report. ESOPE Project. Brussels: European Commission.

- Gangl, M., and A. Ziefle. 2009. “Motherhood, Labor Force Behavior, and Women’s Careers: An Empirical Assessment of the Wage Penalty for Motherhood in Britain, Germany, and the United States.” Demography 46 (2): 341–369.

- Gash, V. 2008. “Bridge or Trap? Temporary Workers’ Transitions to Unemployment and to the Standard Employment Contract.” European Sociological Review 24 (5): 651–668.

- Gash, V., and F. McGinnity. 2007. “Fixed-term Contracts - the New European Inequality? Comparing Men and Women in West Germany and France.” Socio-Economic Review 5 (3): 467–496.

- Gebel, M. 2010. “Early Career Consequences of Temporary Employment in Germany and the UK.” Work, Employment and Society 24 (4): 641–660.

- Giddens, A. 1990. The Consequences of Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Groh-Samberg, O. 2004. “Armut und Klassenstruktur. Zur Kritik der Entgrenzungsthese aus einer multidimensionalen Perspektive.” Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 56 (4): 653–682.

- Grunow, D., F. Schulz, and H.-P. Blossfeld. 2007. “Was erklärt die Traditionalisierungsprozesse häuslicher Arbeitsteilung im Eheverlauf: soziale Normen oder ökonomische Ressourcen? / What Explains the Process of Traditionalization in the Division of Household Labor: Social Norms or Economic Resources?” Zeitschrift fur Soziologie 36 (3): 162–181.

- Kalleberg, A. L. 2009. “Precarious Work, Insecure Workers: Employment Relations in Transition.” American Sociological Review 74 (1): 1–22.

- Konietzka, D. 2002. “Die soziale Differenzierung der Übergangsmuster in den Beruf.” Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 54 (4): 645–673.

- Kraemer, K. 2008. “Prekarität - was ist das?” Arbeit 17 (2): 77–90.

- Kroll, L. E. 2011. “Konstruktion und Validierung eines allgemeinen Index für die Arbeitsbelastung in beruflichen Tätigkeiten anhand von ISCO-88 und KldB-92.” Methoden - Daten - Analysen 5 (1): S. 63–S. 90.

- Kroll, L. E. 2015. Job Exposure Matrices (JEM) for ISCO and KldB (Version 2.0). Gesis Datenarchiv. [online]. Accessed 14 February 2017. http://doi.org/10.7802/1102.

- Kurz, K., N. Steinhage, and K. Golsch. 2005. “Case Study Germany. Global Competition, Uncertainty and the Transition to Adulthood.” In Globalization, Uncertainty and Youth in Society, edited by H. P. Blossfeld, E. Klijzing, M. Mills, and K. Kurz, 51–82. London: Routledge.

- Luijkx, R., and M. H. J. Wolbers. 2009. “The Effects of non-Employment in Early Work-Life on Subsequent Employment Chances of Individuals in the Netherlands.” European Sociological Review 25 (6): 647–660.

- Manzoni, A., and I. Mooi-Reci. 2011. “Early Unemployment and Subsequent Career Complexity: A Sequence-Based Perspective.” Schmollers Jahrbuch 131 (2): 339–348.

- Martin, P., I. Schoon, and A. Ross. 2008. “Beyond Transitions: Applying Optimal Matching Analysis to Life Course Research.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 11 (3): 179–199.

- Müller, W., and Y. Shavit. 1998. “The Institutional Embeddedness of the Stratification Process: A Comparative Study of Qualifications and Occupations in Thirteen Countries.” In From School to Work: A Comparative Study of Educational Qualifications and Occupational Destinations, edited by Y. Shavit, and W. Müller, 1–48. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Nilsen, Ø, and K. Reiso. 2014. “Scarring Effects of Early-Career Unemployment.” Nordic Economic Policy Review 1: 13–46.

- Nordström, O. S. 2011. Scarring Effects of the First Labor Market Experience. IZA Discussion Paper 5565. Bonn: Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit (IZA).

- Olsthoorn, M. 2014. “Measuring Precarious Employment: A Proposal for Two Indicators of Precarious Employment Based on Set-Theory and Tested with Dutch Labor Market Data.” Social Indicators Research 119 (1): 421–441.

- Pedersen, P., T. Lund, L. Lindholdt, E. A. Nohr, C. Jensen, H. J. Sørgaard, and M. Labriola. 2016. “Labour Market Trajectories Following Sickness Absence Due to Self-Reported all Cause Morbidity—a Longitudinal Study.” BMC Public Health 16 (1): 337–347.

- Piore, M. J. 1975. “Notes for a Theory of Labor Market Stratification.” In Labor Market Segmentation. A Research Report to the U. S. Department of Labor, edited by R. C. Edwards, M. Reich, and D. M. Gordon, 125–150. Lexington: DC Heath.

- Robette, N. 2010. “The Diversity of Pathways to Adulthood in France: Evidence From a Holistic Approach.” Advances in Life Course Research 15 (2-3): 89–96.

- Rodgers, G. 1989. “Precarious Work in Western Europe: The State of the Debate.” In Precarious Jobs in Labour Market Regulation: The Growth of Atypical Employment in Western Europe, edited by G. Rodgers, and G. Rodgers, 1–16. Geneva: International Labour Organization.

- Sackmann, R., and M. Wingens. 2003. “From Transitions to Trajectories Sequence Types.” In Social Dynamics of the Life Course: Transitions, Institutions, and Interrelations, edited by W. R. Heinz, 93–115. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

- Schels, B. 2013. “Zwischen Überbrückung und Verstetigung: Leistungsbezugs- und Erwerbssequenzen junger Arbeitslosengeld-II-Empfänger.” WSI-Mitteilungen 66 (8): 562–571.

- Scherer, S. 2001. “Early Career Patterns: A Comparison of Great Britain and West Germany.” European Sociological Review 17 (2): 119–144.

- Schoon, I., and M. Lyons-Amos. 2016. “Diverse Pathways in Becoming an Adult: The Role of Structure, Agency and Context.” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 46 (A): 11–20.

- Sengenberger, W. 1978. Der gespaltene Arbeitsmarkt: Probleme der Arbeitsmarktsegmentation. Frankfurt/Main: Campus-Verlag.

- Simonson, J., L. R. Gordo, and N. Titova. 2011. “Changing Employment Patterns of Women in Germany: How Do Baby Boomers Differ from Older Cohorts? A Comparison Using Sequence Analysis.” Advances in Life Course Research 16 (2): 65–82.

- Solga, H. 2002. “Ausbildungslosigkeit“ als soziales Stigma in Bildungsgesellschaften.” Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie 54 (3): 476–505.

- Standing, G. 2011. The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Strengmann-Kuhn, W. 2001. “Armut trotz Erwerbstätigkeit in Deutschland - Folge der ‘Erosion des Normalarbeitsverhältnisses‘?” In Die Armut der Gesellschaft, edited by E. Barlösius, and W. Ludwig-Mayerhofer, 131–150. Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

- Studer, M. 2013. “WeightedCluster Library Manual: A Practical Guide to Creating Typologies of Trajectories in the Social Sciences with R.” LIVES Working Papers 24: 1–32.

- Stuth, S. 2017. Closing in on Clousure - Occupational Closure and Temporary Employment in Germany. Baden-Baden: Nomos.

- Stuth, S., B. Schels, M. Promberger, K. Jahn, and J. Allmendinger. 2018. Prekarität in Deutschland?!, WZB Discussion Paper. P 2018-004: 1–49.

- Tophoven, S., and A. Tisch. 2016. “Dimensionen prekärer Beschäftigung und Gesundheit im mittleren Lebensalter.” WSI Mitteilungen 69 (2): 105–112.

- Vono de Vilhena, D., Y. Kosyakova, E. Kilpi-Jakonen, and P. McMullin. 2016. “ Does Adult Education Contribute to Securing Non-Precarious Employment? A Cross-National Comparison.” Work, Employment and Society 30 (1): 97–117.

- Vosko, L. F., and L. F. Clark. 2009. “Canada: Gendered Precariousness and Social Reproduction.” In Gender and the Contours of Precarious Employment, edited by L. F. Vosko, M. MacDonald, and I. Campbell, 26–42. New York: Routledge.

- Vosko, L. F., M. MacDonald, and I. Campbell. 2009. “Introduction: Gender and the Concept of Precarious Employment.” In Gender and the Contours of Precarious Employment, edited by L. F. Vosko, M. MacDonald, and I. Campbell, 1–25. New York: Routledge.

- Weinkopf, C. 2009. “Germany: Precarious Employment and the Rise of Mini-Jobs.” In Gender and the Contours of Precarious Employment, edited by L. F. Vosko, M. MacDonald, and I. Campbell, 177–193. New York: Routledge.