ABSTRACT

Youth political disengagement continues to be a major issue facing contemporary democracies that needs to be better understood. There is an existing literature on what determines youth participation in terms of socio-demographic factors, however, scholars have not given much consideration to the macro-level determinants. In this paper, I outline an empirical analysis of what determines political participation among young people using the Eurobarometer 375 survey data from 28 European Union countries. I argue that while socio-demographic factors are crucial for youth political participation, context matters in shaping levels of political participation among young people. The results from the logistic regression analyses indicate that democratic maturity influences patterns of political participation among young people in the EU. The results show that youth engagement in different modes of political participation varies significantly across distinctive democracies, where individuals situated in established EU democracies are more likely to be politically active. The findings raise fresh concerns about existing levels of young people’s engagement in politics in advanced and new democracies. This paper also contributes to the comparative research on young people’s participation in politics.

Introduction

Participation in political activities is in crisis, especially when it comes to young people, and this is a major issue facing contemporary democracies (Norris Citation2003; Hay Citation2007; Farthing Citation2010; Furlong and Cartmel Citation2012; Henn and Foard Citation2012). This is a vital challenge that is re-shaping electoral politics and the relationship between citizens and political parties. Generation Y seems to have lower levels of political engagement when it comes to participating in traditional forms of politics such as voting and being a member of a political party, compared to older generations (Mycock and Tonge Citation2012). Youth are perceived as increasingly disengaged and disconnected from traditional political processes in Europe, especially when it comes to voting (European Commission Citation2001). Moreover, young people are not only disengaged but they might be apathetic and/or alienated from the traditional forms of politics (Stoker Citation2006; Hay Citation2007). It is expected that there are variations in levels of political engagement across Europe (Ministry of Justice Citation2007), which is tested in this paper, when it comes to young people. The paper contributes to youth engagement literature by conducting empirical research investigating determinants of young people’s political participation by conceptualising age of democracy.

In recent decades, there has been a decline in levels of political engagement in most European Union countries (Pharr and Putnam Citation2000; Torcal and Montero Citation2006; Norris Citation2011; Papadopoulos Citation2013; Allen and Birch Citation2015). Youth are regarded as one of the most disengaged groups in politics, with the lowest levels of turnout compared to any other age group in elections. The 2017 Bulgarian Parliamentary Election is an exact example, with young people’s turnout being only 14.9% (Gallup International Citation2017). On the contrary, in the Scottish Independence Referendum in 2014 when 16 and 17-year-olds were given the right to vote, 89% of all citizens aged 16–17 in Scotland registered to vote, which indicates an exceptional case. Results from an EU funded MYPLACE survey in 14 European countries revealed that 42% of respondents aged 16–24 reported to have interest in politics (Tatalovic Citation2015). Young people have interest in politics and are often influenced by single-issued politics (Mort Citation1990; Wilkinson and Mulgan Citation1995; Henn and Foard Citation2012). However, having interest in politics would not necessarily translates into votes.

A research area that requires better theorising and empirical research is what are the explanatory factors of youth political engagement in Europe, especially differentiating between a diverse range of political activities. Therefore, the research question addressed in this paper is: What determines political participation among young people in the EU? My conceptualisation of political participation defines the term as any lawful activities undertaken by citizens that will or aim at influencing, changing or affecting the government, public policies, or how institutions are run (adopted from Verba and Ni Citation1972; Van Deth Citation2001).

I address the variations of levels of youth political participation across Europe by analysing the Eurobarometer survey dataset (No. 375 Citation2013) on young people aged 15–30 from 28 EU countries. I apply logistic regression analyses of socio-demographic and contextual factors to a range of political activities controlling for countries to establish relationships and differences between age groups. I argue that the age of democracy fundamentally conditions the way young people participate in politics. The analyses reveal that while social and educational factors (at individual-level) matter, democratic maturity accounts for patterns of political participation among young people in the EU. I close by discussing the variations within EU countries and the most distinctive differences in levels of youth participation in formal political participation versus organisational membership.

Young people’s participation in politics

A great deal of previous research into political participation has focused mainly on voting as a political activity exercised by the citizens (Lazarsfeld, Berelson, and Gaudet Citation1948; Campbell et al. Citation1960). Consequently, political participation became more than just the traditional political activities such as voting. It adopted a diverse range of activities such as people being members of different organisations, participating in cultural organisations or activities, signing petitions, contacting politicians, protesting, etc (Verba, Nie, and Kim Citation1978; Barnes and Kaase Citation1979; Van Deth Citation2001; Bourne Citation2010). A refined definition of the term was developed in later years and included actions or activities that are directed towards influencing political outcomes (Teorell, Torcal, and Montero Citation2007).

With the changing nature of political actions, new forms of political participation started emerging and it is claimed that youth engage more in politics through new types of political activities, as young people nowadays are very different from their parents’ generation (Norris Citation2003; Spannring, Ogris, and Gaiser Citation2008; Kestilä-Kekkonen Citation2009; Sloam Citation2016). However, Grasso (Citation2014) analyses that today’s youth is the least politically engaged generation when it comes to formal and informal political participation. In addition, ‘Millennials’ seem to be a ‘unique’ generation, disengaged from any form of political participation (Fox Citation2015).

There is a debate about youth political participation falling in crisis (Putnam Citation2000; Stoker Citation2006; Fieldhouse, Tranmer, and Russell Citation2007). Many studies reveal that there is a tremendous and worrying decline in levels of youth participation in politics, especially when it comes to voting. Yet, some of the recent studies argue that young people are not apathetic and disengaged, but they have instead turned to alternative forms of political engagement such as protesting, demonstrating, being part of organisations, signing petitions, volunteering, and engaging online (Norris Citation2003; Spannring, Ogris, and Gaiser Citation2008; Sloam Citation2016). Others found that young people are equally disengaged from formal and informal political participation (Grasso Citation2014; Fox Citation2015).

Young people are often seen as disengaged, alienated, and/or apathetic when it comes to political engagement. There is tremendous value in repeated studies on youth disengagement in single countries. The British Social Attitudes report (Ormston and Curtice Citation2015) revealed an important finding related to declining youth turnout: in 2013 only 57% of the respondents felt that they have the duty to vote, compared to 76% in 1987. It is clear that there is a long-term decline in young people’s involvement in elections in most of the European Union countries (O'Toole, Marsh, and Jones Citation2003). These results are in sync with the conventional wisdom that youth are disengaged from the political system (Wring, Henn and Weinsten Citation1999).

Norris (Citation2002; Citation2003) highlights active youth engagement with respect to alternative forms of political participation and supports the recent theoretical claim that young people are not ebbed away in apathy, however they are choosing other forms of politics that are not traditional and seem more meaningful to them (Spannring, Ogris, and Gaiser Citation2008; Sloam Citation2013). One organising idea is that young people feel excluded from the traditional political system (O'Toole, Marsh, and Jones Citation2003) resulting in recent changes in the way they engage in politics (Harris, Wyn, and Younes Citation2010; Henn and Foard Citation2012; Sloam Citation2013). It is the conventional wisdom that young people are less likely to vote than adults, and young people are less engaged with political parties and organisations (Tilley Citation2003; Mycock and Tonge Citation2012).

Despite the growing interest in youth political participation, relatively little scholarly attention has been paid to existing differences in the levels of youth participation across countries (Norris Citation2003; Spannring, Ogris, and Gaiser Citation2008; Dalton Citation2009; Sloam Citation2013; Citation2016). This paper addresses such gaps in the literature and analyses the effect of age of democracy on youth participation. When studying determinants of political participation, research should take into account not only individual-level characteristics, but also contextual ones as distinctions in contextual settings can have a direct and diverse impact on political participation, especially when it comes to comparative research.

Formal political participation is defined as activities related to traditional forms of participation such as voting, being a member of a party, and campaigning (Verba and Ni Citation1972; Inglehart Citation1990; Mair Citation2006). This represents the older studies’ perspectives on political participation and thus assumes that there should be no inclusion of the newly established concepts of participation. Political participation became more than just the traditional political activities such as voting (Ekman and Amnå Citation2012). In the past, the ‘traditional’ form of political participation was seen as the superior one consisting of voting and being a member of a political party. Whereas, recently, it consists of diverse activities such as people being members of political parties or different organisations, participating in a cultural organisation or activities (Bourne Citation2010).Footnote1 This paper is about organisational membership as a subset of non-traditional participation. For the purpose of this paper and due to data availability, in terms of ‘formal’ political activity, I analyse voting and being a member of a political party; and I also analyse ‘organisational membership’, which refers to being a member of different organisations.Footnote2

The role of socio-demographic characteristic is widely acknowledged (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Citation1995; Stolle and Hooghe Citation2009; Vecchione and Caprara Citation2009; Cainzos and Voces Citation2010). The predominant view in the literature is that social class and educational history appear to be crucial predictors of political engagement (Tenn Citation2007; Sloam Citation2012; Holmes and Manning Citation2013). Especially when it comes to youth participation in politics, education and social class have most bearing on levels of youth political engagement (Henn and Foard Citation2014), where the length of time a person has been in full-time education has a crucial impact on their political participation (Flanagan et al. Citation2012).

Conceptualising age of democracy

The idea that contextual factors can cause differences in youth participation has been studied in recent years (Fieldhouse, Tranmer, and Russell Citation2007; Grimm and Pilkington Citation2015; Soler-i-Marti and Ferrer-Fons Citation2015; Sloam Citation2016). Political context matters when it comes to engagement in politics (Grasso Citation2016) and it is plausible to suggest that growing up in a certain context and environment would shape young people’s political engagement depending on their cultural settings (Snell Citation2010). Therefore, it is important to contextualise young people’s politics (Torney-Purta Citation2009) and the main expectation of this paper is that there are potential differences in terms of levels of youth political participation when it comes to age of democracy. Conceptualising age of democracy contributes to the existing literature on determinants of political participation, and provides a new theoretical and empirical contribution to the influencers of youth political engagement.

All countries analysed in this paper are EU democracies, however, I expect there to be differences in levels of youth political participation across countries. There is a conventional wisdom that long-established democracies have relatively stable levels of political participation, with individual turnout being quite high. On the other hand, there are countries that have gone through the transition to democracies not that long ago. Such countries would have different political characteristics and historical trajectories to advanced democracies. The seminal study of Almond and Verba (Citation1963) report that a set of political orientations foster democratic stability. Their study also concluded that a large number of citizens in the U.K. and the U.S. believe that they have high levels of obligation to participation. Whereas, Germans, Italians and Mexicans do not necessarily have the same extent of obligation to participation. It is evident from their study that the norm of being an active citizen in a society is prevalent among advanced democratic countries such as the U.K. and the U.S. These norms together with existing opportunities to participate in a country could underline and account for high levels of political participation in one country and the low levels of participation in another. For instance, in countries such as ItalyFootnote3 or any newly developed democracy, there is a lack of opportunity to participate and there is a lack of existing norms in that society. Similar to the U.K. and the U.S., citizens in advanced democracies are motivated by the norms and political opportunities in their country to participate in politics. I argue therefore that citizens in advanced democracies have a sense of obligation to be active in the political life of their country, and the opportunities to participate in politics are higher in advanced democracies.

Almond and Verba (Citation1963) report that there are existing differences across contrasting educational groups in the same countries, and across similar educational groups in distinctive countries. Therefore, I expect that youth political participation varies across countries, thus a person from country A with socio-demographic characteristics A1 A2 and A3 might actively participate in formal politics, however, a person from country B with the same socio-demographic characteristics might be actively engaged in alternative activities and totally disengaged from the traditional forms of political participation.

The literature offers a mixed set of explanations about youth engagement in politics. On one hand, one would expect young people to be disengaged and alienated from traditional forms of politics. On the other hand, existing arguments present that not only are young people disengaged from traditional forms of politics but from politics in general. My expectation is summarised in the following hypothesis:

H1: Younger citizens engage more with organisational membership than with formal politics.

Age of democracy has been discussed for a long time (Lipset Citation1959; Almond and Verba Citation1963; Citation1989; Converse Citation1969; Inglehart Citation1988). A recent study by Nový and Katrnak (Citation2015) analyses the influence of democratic maturity on the propensity of citizens to vote by exploring 27 countries, finding that individuals in long-established democracies are more likely to vote. The conventional wisdom is that advanced democracies have greater levels of political participation (Barnes Citation2004; Bernhagen and Marsh Citation2007; Karp and Milazzo Citation2015), and this is tested in this paper. Lack of political activity is more likely to be apparent in countries that are newly democratised. Democratic maturity presents the individuals with conditions that shape their choice to participate or not participate in politics, and how to participate. I argue that age of democracy has a direct impact on the propensity of young individuals to engage in politics but it also acts as an amplifier. The historical context of newly established post-Communist countries and advanced democracies has a potential influence on the political behaviour of individuals situated in these countries.

The long-term functioning of democratic institutions gradually creates a democratic political culture (Mishler and Rose Citation2001). Through the democratic experience in a country, individuals develop loyalty and certain habits (Jackman and Miller Citation2004). Countries with similar historical trajectories will have similarities to the process of how a young person goes through life and develops their political beliefs and behaviour. In post-communist countries, the democratic experience is new, therefore, there would not be necessary developed habits of voting. In new democracies, historically there is high level of state centralisation, low levels of freedom, and not automatically examples in the family how to engage in political participation. Therefore, I hypothesise that:

H2: Young people are more engaged in politics in advanced democracies compared to new democracies.

On the expectation that people are more engaged in traditional forms of politics in advanced democracies than in newly established democracies, here I test if this expectation still holds when analysing organisational membership. The expectation is that due to numerous institutional differences between advanced and new democracies, young people are more inclined to participate in politics if they are situated in an advanced democracy. Therefore, I expect that in advanced democracies, young people are more active in alternative forms of political participation compared to newly established democracies. I, therefore, propose the following hypothesis:

H3: Young people are more engaged with organisational membership in advanced democracies compared to new democracies.

Researchers have typically analysed youth participation on a national level. There are expectations that participation varies between individual countries and between a diverse range of political activities. However, prior studies of youth participation say little about the potential differences across countries. Therefore, my novel theoretical and empirical contribution is that while social and educational factors (at individual-level) matter, age of democracy influences patterns of political participation among young people in the EU.

Data and methods

This paper draws on data from the Eurobarometer (No. 375 Citation2013) comparative survey on youth engagement: a dataset consisting of 13,427 respondents across 27 members of the European Union (EU) countries and Croatia,Footnote4 allowing for a cross-national comparison of young people’s contextual predictors of political engagement. The survey aims to analyse young EU citizens’ participation in society, organisations, political parties, and participation in elections at local, regional and national level. The Eurobarometer 375 dataset contains only young respondents, which is the targeted age group for my paper, consisting only of participants aged 15–30. It is crucial to acknowledge that some of these respondents are not eligible to engage in formal participation; therefore, the observations for 15–17-year-olds Footnote5 were dropped from the dataset, making the sample 11,213 respondents. It is important to note that a limitation of the data is that it does not represent the full population. However, the data allows comparing how people differ in terms of diverse age groups and compare and contrast, for instance, 18-year-olds with 30-year-olds.

Dependent and independent variables

The existing secondary data from the Eurobarometer 375 survey is used as diverse questions were asked related to young people’s individual characteristics and their participation in politics, allowing me to grasp whether or not their contextual characteristics are potential determinants of political engagement.

Dependent variables

The Eurobarometer survey asked about young people’s participation in a range of political activities. The dependent variables used in my analysis derive from several questions as presented in . To assess and test my hypotheses, I constructed two dependent variables accounting for the two modes of political participation that the data allows me to analyse in this paper: formal participation and organisational membership. Here, I analyse membership of a range of social and civic organisations, where I treat ‘organisational membership’ as another dependent variable. I constructed an additional variable that accounts for youth political participation in general, which allows testing the overall patterns of youth political participation. All dependent variables were derived using a binary measure of whether or not someone had participated in a particular activity from the Eurobarometer 375 questionnaire (see ). The dependent variable formal political participation reflects whether a person has participated in traditional political activities, meaning if they have voted or are a member of a political party. Respectively, the dependent variable organisational membership refers to engagement with different organisations as presented in . The additional dependent variable general political participation accounts for whether or not overall participation varies across countries and it is derived using the two initial dependent variables.

Table 1. Coding for dependent variables (Eurobarometer 375 Citation2013).

Independent variables

Socio-demographic characteristics are considered as important explanatory variables for political engagement (Tenn Citation2007; Flanagan et al. Citation2012; Furlong and Cartmel Citation2012; Holmes and Manning Citation2013; Henn and Foard Citation2014). I contribute to the literature by offering conclusions on the role of socio-demographic factors in structuring youth political participation when it comes to a range of political engagement.

The Eurobarometer (375 Citation2013) provides demographic measures for the respondents through a set of socio-demographic questions including age, gender, education, and current occupational status of the respondents. Age is coded as a categorical variable to differentiate between respondents aged 18–24 and respondents aged 25–30. Gender is coded as a dichotomous variable where 1 is a male respondent, and the reference category is a female respondent. Education is a categorical variable with categories reflecting the individuals’ education status. Social class is a categorical variable and includes values for lower class, middle class, higher class, respondents who are not working, and respondents who are still in education.Footnote6 The data for this variable was mapped with the National Statistics Socio-economic Classification Analytic classes and the ABC1 demographic classifications in the U.K. It is important to acknowledge that there is no income question, which prohibits the use of an income measure in the analysis. However, with age, education and social class included in the analysis, the lack of income measure does not constitute a significant issue for the purpose of this paper.

In order to test for the effect of age of democracy on the propensity of young individuals to participate in politics, I include a variable that distinguishes between countries that are newly established and advanced democracies. This allows testing whether age of democracy is influential when it comes to the propensity of young individuals to participate in politics in EU countries. Following Huntington (Citation1991), Muhlberger and Paine (Citation1993) and Dunn (Citation2005), new democracies were identified as countries that became democratic post-1988, which includes 11 countries.Footnote7 Advanced democracies are considered EU countries that became democracies post-1945 and pre-1988, which includes 17 countries. In the literature, countries classified as emerging democracies in Europe in 1970 (Portugal and Spain) are classified as established ones for the purpose of this paper. Here, I test the assumption that youth political participation varies within different ages of democracies and across individual countries.

Results

To determine what shapes youth political engagement, and to identify the crucial explanatory factors associated with it, a logistic regression is applied. I argue that both micro- and macro-level factors matter and influence levels of political participation among young people. The existing literature suggests that socio-demographic factors such as gender, age, education and social class have an impact on individuals’ political participation (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Citation1995; Stolle and Hooghe Citation2009; Cainzos and Voces Citation2010; Henn and Foard Citation2014). The logistic regression analyses applied here to test whether or not these theoretical claims hold in regard to the Eurobarometer 375 survey data. This paper suggests that there is a significant positive relationship between contextual factors and young people’s political participation. I also assess whether or not there are differences in the explanatory factors of young people’s participation in politics when it comes to a range of political activities (Lieberman Citation2005).

Young people’s engagement in politics in the EU

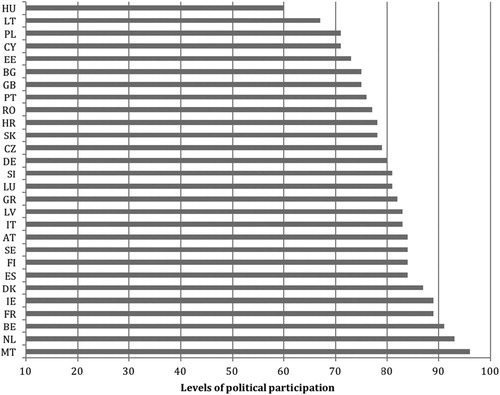

illustrates levels of youth political participation across countries (Eurobarometer 375 Citation2013) and reveals that overall youth political participation varies across countries (see ).

Figure 1. Levels of youth political participation across EU countries (Eurobarometer 375 Citation2013).

Although the descriptive analysis shows that levels of youth participation varies across countries, it is important to analyse if this pertains to engagement in traditional modes of politics only, as numerous authors have claimed that Generation Y are not apathetic but have orientated towards new forms of political engagement (Norris Citation2003; Spannring, Ogris, and Gaiser Citation2008; Sloam Citation2013). In this paper, logistic regression is applied to investigate the differences between the two modes of political engagement and explains why some individuals are more politically engaged than others by looking at micro- and macro-level factors as determinants of political engagement.

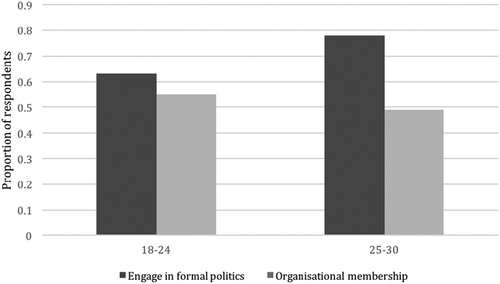

Firstly, I analyse political participation as a function of age only. There are variations in young people’s political engagement depending on their age and as seen in , the results indicate that individuals aged 18–24 are more likely to be a member of an organisation than individuals aged 25–30 (58% compared to 49%). Not surprisingly, the respondents aged 25–30 engage more in formal politics than respondents aged 18–24 (78% compared to 63%).

Figure 2. Proportion of respondents from different age group participating in formal politics compared to being members of organisations (Eurobarometer 375 Citation2013).

Socio-demographic factors determining youth political engagement

In line with earlier studies (Verba, Schlozman, and Brady Citation1995; Stolle and Hooghe Citation2009; Vecchione and Caprara Citation2009; Cainzos and Voces Citation2010), a common trend that emerges from the analysis is that socio-demographic factors are important predictors of political engagement with important differences between and within age groups when it comes to diverse forms of political engagement. Therefore, I first fit a regression model only with age as a predictor.

As shows, the results from the regression model with ‘age’ as a predictor of youth political engagement are statistically significant and suggest that respondents aged 25–30 are two times as likely to participate in formal political activities than people aged 18–24. On the other hand, the odds of being a member of an organisation for respondents aged 25–30 are 20% lower than the odds for respondents aged 18–24. Age significantly associates with higher levels of participation in traditional political activities. suggests that there is an inverse relationship between age and organisational membership and indicates that as a respondent gets older, the odds of them being members of organisations decreases. In other words, the younger a person is, the more likely they are to be members of organisations, which confirms H1. Even if I expand the analysis of organisational membership to include respondents aged 15–17, the pattern remains the same (see supplemental material Appendix CFootnote8).

Table 2. Results from the logistic regression models of the propensity of young individuals to engage in politics with age a control variable: Formal political participation and organisational membership.

presents the logistic regression model with socio-demographic characteristics as predictors. The results for general political participation, formal political participation, and organisational membership are presented in Model 1, Model 2 and Model 3 respectively. In all of the regression models, I control for country-fixed effects. The results for each country are presented in the supplemental material (see supplemental material Appendix A).

Table 3. Results from the logistic regression models of the propensity of young individuals to engage in politics with socio-demographic characteristics only: Model 1 (general political participation), Model 2 (formal political participation), and Model 3 (organisational membership).

The results from the regression analyses show that both education and social class have a positive and significant effect on the propensity of young individuals to participate in politics, as seen in . These results are consistent with previous studies (Tenn Citation2007; Sloam Citation2012; Holmes and Manning Citation2013; Henn and Foard Citation2014). Education as a predictor is statistically significant (p < 0.01) for youth political participation. The results show that having left education at 19 or above lead to an increase of two times in the odds of participating in formal political activities, compared to respondents who left school at 18 or younger. When comparing these findings with the results for organisational membership, Model 3 suggests that the odds for respondents who have left education at 19 or above to be a member of organisation are 45% higher than the odds for respondents who left education at 18 or below. Moreover, the odds for a person who is still in education to be involved with an organisation are 50% higher than the odds of a respondent who left school at 18 or above. The analysis of the Eurobarometer data using logistic regression, as reported in , reveals that there are statistically significant variations in the effects of social class at the 1% level (p < 0.01). Respondents from higher social class are about half as likely to engage in any form of participation than their counterparts from a lower social class. Gender is also a positive significant predictor of political participation.

Young people’s contextual predictor of political engagement in EU democracies

For the purpose of this paper, each of the 28 EU countries from the dataset was classified as either newly established or advanced democracy, where democracies established before 1988 were classified as ‘advanced’ and the post-communist countries were coded as ‘new’. To test whether democratic maturity is a significant influencer of youth participation in politics, a new variable age of democracy accounting for countries’ democratic age was included in the regression model. The model suggests that participation is defined as a function of age and other socio-demographic predictors plus age of democracy, controlling for countries.Footnote9 The effect of age of democracy on youth engagement is presented in . Full regression analysis is available in the supplemental material (supplemental material Appendix B).

Table 4. Results from the logistic regression models of the propensity of young individuals to engage in politics controlling for age of democracy: Model 4 (general political participation), Model 5 (formal political participation), and Model 6 (organisational membership).

The results from indicate that age of democracy is a crucial predictor of youth participation across EU countries. In line with current existing literature on democratic maturity as a predictor of political participation (Nový and Katrnak Citation2015), the results of the regression models featuring age of democracy, suggest that political engagement among young people varies within different age of democracy. The odds for young Europeans who live in a newly established democracy to be politically engaged are 27% lower than the odds for young citizens in established democracies and this is statistically significant. Tellingly, this characterisation supports the findings from earlier studies that participation is lower in post-communist countries compared to established democracies (Barnes Citation2004; Bernhagen and Marsh Citation2007). This confirms H2, which predicts that youth are more politically engaged in established democracies. The results from the regression models controlling for countries reveal that there are some statistically significant variations in levels of youth engagement across different established democracies (see supplemental material Appendix B). For instance, the results indicate that political engagement is low in the U.K., which is also evident in previous studies reporting that the Generation Y in Britain is very disengaged from politics (Wring, Henn and Weinsten Citation1999; Grasso Citation2014; Fox Citation2015). Young people in Britain are less likely to vote or be a member of a political party compared to respondents from the reference category (France). Respondents from the U.K. have the lowest levels of participation in politics across the EU countries together with Cyprus, Estonia, Hungary, Lithuania, and Poland; young people in these countries are less likely to participate in politics than respondents in France. The odds of respondents from newly established democracies to be a member of an organisation are 59% lower than the odds for respondents from advanced democracies. This result is statistically significant (p < 0.01), which confirms H3, which suggest that young people in advanced democracies are more likely to be members of organisations than young individuals in new democracies.

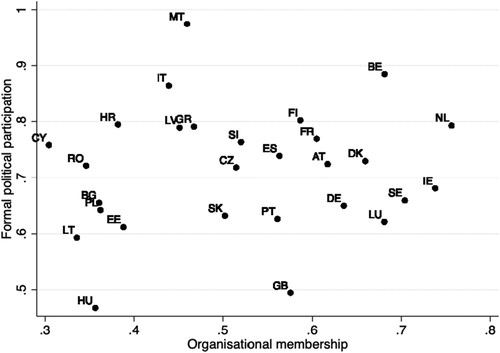

illustrates as well that levels of political participation in some countries differ significantly from those in another set of countries. This could be explained by the unique experiences of these countries. shows the average young citizens’ involvement in formal politics and organisations. The scatterplot indicates that there is a general pattern that advanced democracies have higher levels of youth political participation in formal politics as well as in organisational membership. If we consider the political history of post-Communist countries, these tendencies are not surprising. In the process of democratisation, these countries had a single-party rule, state ownership, highly centralised economy, and institutions were under transformation. Post-communist countries experienced nation-building and industrialisation in later years, and the occurrence of civil society was delayed. In addition, in post-communist countries, the levels of socio-economic development and levels of confidence in the institutions are slightly different than in advanced democracies across the EU.

Figure 3. Average levels of political engagement in formal participation and organisational membership (Eurobarometer 375 Citation2013).

As evident in , in countries that are advanced democracies, participation in formal politics is higher, with the exception of the U.K. and Italy.Footnote10 Of course, there are exceptions, such as Latvia and Slovenia, which both have relatively higher political engagement in comparison to other newly democratised countries. It cannot be expected every country to fit perfectly into this pattern of course.

As the results from the regression analyses reveal, youth engagement in politics varies across distinctive age of democracies across European countries and across different forms of participation. It is interesting to note that some countries (Germany, Luxemburg, Ireland, Latvia, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia) with lower levels of engagement in formal politics than France, have higher levels of engagement with organisationsFootnote11 (see supplemental material Appendix B). Countries with extremely high levels of youth participation in formal activities (Belgium, Netherland) also have high levels of participation in organisational membership. The results from the regression analyses indicate that a young person in Latvia is more likely to participate in politics than a young person in France. However, as this is a single case from a survey that does not provide longitudinal data, this finding is not enough to reject H3.

Conclusion

Youth participation matters and the issue of youth disengagement continues to be a major one facing contemporary democracies. There is a need to understand what determines young people’s engagement in politics better. Most scholars have analysed the issue of political (dis)engagement among young people in a single country only; this paper adds contribution to comparative research on young people’s engagement in politics.

The overarching aim of this paper was to investigate the determinants of political participation among young people, and to explore the relationship between socio-demographic factors, contextual factors and a diverse range of political activities. The results of the logistic regression represented a sample of 11,213 young respondents from 28 different European countries. The findings from the regression analyses suggest that the socio-demographic factors that predict political participation among young people are age, education and social class, which is consistent with previous studies (Stolle and Hooghe Citation2009; Vecchione and Caprara Citation2009; Henn and Foard Citation2014). In terms of the contextual predictors of political participation among young people, there are differences between countries, especially between new and old democracies. The logistic regression results suggest that political participation among young people is determined by the democratic maturity of the country they live in. The logistic regression models suggest that political participation among young people is not universal in any democracy but varies with the age of democracy.

Overall, the analyses reveal that respondents aged 18–24 are more likely to be members of organisations. Some of the main findings suggest that after controlling for socio-demographic characteristics, a respondent who is aged 25–30 is more likely to participate in formal politics than a respondent aged 18–24, which indicates that the older the person is, the more likely they are to vote and participate in any kind of formal politics.

Age of democracy has a crucial impact on young people’s engagement in politics in different European Union countries as the levels of political participation are significantly lower in newly established democracies compared to advanced democracies. In advanced democracies, voting might be perceived as a habit and people living in established democracies might experience more social pressure to participate in politics. This paper shows evidence that youth political participation is hindered by the context within each individual engages and suggests that further research on youth political participation should incorporate macro-level factors as well.

A limitation in this study is that organisational membership does not fully account for alternative forms of political participation due to data limitation. However, organisational membership is a subset of informal participation and allows for a meaningful comparison between different modes of political participation. In future research, more variables that account for informal political participation should be analysed. This paper leads to questions for future research on the topic of contextual predictors of youth political participation, where macro-level factors should be explored. In addition, for future research, it would be interesting to explore whether the pattern of age of democracy being a significant determinant of political participation is universal to young people only or it applies to all ages.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (36.1 KB)Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Will Jennings, Adriana Bunea, and Viktor Valgardsson for their excellent comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Political activities such as boycotting, demonstrating, protesting, etc. are not analysed in this paper as the Eurobarometer 375 (Citation2013) survey does not address such questions.

2 See Data and methods for details.

3 Which during the time of the seminal study of Almond and Verba (Citation1963) was a newly established democracy in comparison to the UK and the US.

4 When the survey was carried out, Croatia was not a member of the European Union; it became a member on July 1, 2013.

5 I am excluding these participants from the analysis because they cannot engage in formal participation, therefore, it is not possible to make inferences about them.

6 There is no cross-national standard question about social class, which is a limitation. Clearly, a limitation is, as the data are youth focused, the ‘occupation’ question is not necessarily most accurate for determining social class patterns of a respondent, as the majority of answers to this question are ‘still in education’, but all of the answers to the ‘What is your occupation?’ question were grouped in different categories, creating the social class independent variable.

7 Post-communist countries and countries that used to belong to the Soviet Union.

8 Additional analysis for the purpose of robustness check of the results.

9 Malta was excluded from the regression analysis due to lack of data and has extremely low values, therefore might skew the results and make them less reliable for inference. The results are consistent when it is included.

10 This is descriptive statistics, please refer to the regression analyses for statistically significant results.

11 In relation to the reference category: France.

References

- Allen, N., and S. Birch. 2015. “Process Preferences and British Public Opinion: Citizens’ Judgements About Government in an Era of Anti-Politics.” Political Studies 63 (2): 390–411.

- Almond, G., and S. Verba. 1963. The Civic Culture. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Almond, G., and S. Verba. 1989. The Civic Culture: Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations. London: SAGE.

- Barnes, S. H. 2004. “Political Participation in Post-Communist Central and Eastern Europe.” Center for the study of democracy, Paper 04'10.

- Barnes, S., and M. Kaase. 1979. Political Activity: Mass Participation in Five Western Democracies. London: Sage.

- Bernhagen, P., and M. Marsh. 2007. “Voting and Protesting: Explaining Citizen Participation in Old and New European Democracies.” Democratization 14 (1): 44.

- Bourne, P. A. 2010. “Unconventional Political Participation in a Middle-Income Developing Country.” Current Research Journal of Social Sciences 2 (2): 196–2003.

- Cainzos, M., and C. Voces. 2010. “Class Inequalities in Political Participation and the ‘Death of Class’ Debate.” International Sociology 25 (3): 383–418.

- Campbell, A., P. Converse, W. Miller, and D. Stokes. 1960. The American Voter. New York: John Wiley and Sons Inc.

- Converse, P. 1969. “Of Time and Partisan Stability.” Comparative Political Studies 2: 139–171.

- Dalton, R. 2009. The Good Citizen: How a Younger Generation Is Reshaping American Politics. Revised ed. Washington, DC: CQ Press.

- Dunn, J. 2005. Democracy: A History. New York: Atlantic Monthly.

- Ekman, J., and E. Amnå. 2012. “Political Participation and Civic Engagement: Towards a New Typology.” Human Affairs 22: 283–300.

- Eurobarometer. 2013. “ European Youth: Participation in Democratic Life. No. 375.”

- European Commission. 2001. European White Paper on Youth. Brussels: EU.

- Farthing, R. 2010. “The Politics of Youthful Antipolitics: Representing the ‘Issue’ of Youth Participation in Politics.” Journal of Youth Studies 13 (2): 181–195.

- Fieldhouse, E., M. Tranmer, and A. Russell. 2007. “Something About Young People or Something About Elections? Electoral Participation of Young People in Europe: Evidence from a Multilevel Analysis of the European Social Survey.” European Journal of Political Research 46: 797–822.

- Flanagan, C., A. Finlay, L. Gallay, and T. Kim. 2012. “Political Incorporation and the Protracted Transition to Adulthood: The Need for New Institutional Inventions.” Parliamentary Affairs 65 (1): 29–46.

- Fox, S. 2015. “ Apathy, Alienation and Young People: The Political Engagement of British Millennials.” PhD thesis. University of Nottingham. P. 4.

- Furlong, A., and F. Cartmel. 2012. “Social Change and Political Engagement Among Young People: Generation and the 2009/2010 British Election Survey.” Parliamentary Affairs 65 (1): 13–28.

- Gallup International. 2017. “ Галъп представя профилите на гласоподавателите.” Nova TV Election. Accessed 3 June 2017. https://nova.bg/news/view/2017/03/27/177690/галъп-представя-профилите-на-гласоподавателите/.

- Grasso, M. T. 2014. “Age, Period and Cohort Analysis in a Comparative Context: Political Generations and Political Participation Repertoires in Western Europe.” Electoral Studies 33: 63–76.

- Grasso, M. T. 2016. Generations, Political Participation and Social Change in Western Europe. London: Routledge.

- Grimm, R., and H. Pilkington. 2015. “‘Loud and Proud’: Youth and the Politics of Silencing’.” The Sociological Review 63 (S2): 206–230.

- Harris, A., J. Wyn, and S. Younes. 2010. “Beyond Apathetic or Activist Youth.” Young 18 (1): 9–32.

- Hay, C. 2007. Why We Hate Politics. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Henn, M., and N. Foard. 2012. “Young People, Political Participation and Trust in Britain.” Parliamentary Affairs 65 (1): 47–67.

- Henn, M., and N. Foard. 2014. “Social Differentiation in Young People's Political Participation: The Impact of Social and Educational Factors on Youth Political Engagement in Britain.” Journal of Youth Studies 17 (3): 360–380.

- Holmes, M., and N. Manning. 2013. “He’s Snooty ‘Im’: Exploring ‘White Working Class’ Political Disengagement.” Citizenship Studies 17 (3–4): 479–490.

- Huntington, S. P. 1991. The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press.

- Inglehart, R. 1988. “The Renaissance of Political Culture.” The American Political Science Review 82 (4): 1203–1230.

- Inglehart, R. 1990. Culture Shift in Advanced Industrial Societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Jackman, R. W., and R. A. Miller. 2004. Before Norms: Institutions and Civic Culture. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Karp, J. A., and C. Milazzo. 2015. “Democratic Scepticism and Political Participation in Europe.” Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties 25 (1): 97–110.

- Kestilä-Kekkonen, E. 2009. “Anti-party Sentiment Among Young Adults.” Young 17 (2): 145–165.

- Lazarsfeld, P., B. Berelson, and H. Gaudet. 1948. The People's Choice: How the Voter Makes Up His Mind in a Presidential Campaign. 2nd ed. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Lieberman, E. S. 2005. “Nested Analysis as a Mixed-Method Strategy for Comparative Research.” The American Political Science Review 99 (3): 435–452.

- Lipset, S. M. 1959, Mar. “Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy.” The American Political Science Review 53 (1): 69–105.

- Mair, P. 2006. “Ruling the Void? The Hollowing of Western Democracy.” New Left Review 42: 25–51.

- Ministry Of Justice. 2007. “ The Governance of Britain.” http://www.official-documents.gov.uk/document/cm71/7170/7170.pdf.

- Mishler, W., and R. Rose. 2001. “What Are the Origins of Political Trust? Testing Institutional and Cultural Theories in Post-communist Societies.” Comparative Political Studies 34: 30–62.

- Mort, F. 1990. “‘The Politics of Consumption’.” In New Times: The Changing Face of Politics in the 1990s, edited by S. Hall and M. Jacques, 160–172. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

- Muhlberger, S., and P. Paine. 1993, Spring. “Democracy's Place in World History.” Journal of World History 4 (1): 23–45.

- Mycock, A., and J. Tonge. 2012. “The Party Politics of Youth Citizenship and Democratic Engagement.” Parliamentary Affairs 65 (1): 138–161.

- Norris, P. 2002. Democratic Phoenix: Reinventing Political Activism. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Norris, P. 2003. “ Young People and Political Activism: From the Politics of Loyalties to the Politics of Choice?”. Paper presented to the council of Europe Symposium, ‘Young people and democratic institutions: From disillusionment to participation’, Strasbourg, November 27–28.

- Norris, P. 2011. Democratic Deficit: Critical Citizens Revisited. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Nový, M., and T. Katrnak. 2015. “Democratic Maturity, External Efficacy, and Participation in Elections: Towards Macro-Micro Interaction.” Austrian Journal of Political Science 44 (3): 1–20.

- Ormston, R., and J. Curtice. 2015. British Social Attitudes: The 32nd Report. London: NatCen Social Research.

- O'Toole, T., D. Marsh, and S. Jones. 2003. “Political Literacy Cuts Both Ways: The Politics of Non-Participation among Young People.” The Political Quarterly 74 (3): 349–360.

- Papadopoulos, Y. 2013. Democracy in Crisis? Politics, Governance and Policy. London: Palgrave.

- Pharr, S. J., and R. D. Putnam. 2000. Disaffected Democracies: What's Troubling the Trilateral Countries?. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Putnam, R. D. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Sloam, J. 2012. “Rejuvenating Democracy?’ Young People and the ‘Big Society’ Project.” Parliamentary Affairs 65 (1): 90–114.

- Sloam, J. 2013. “‘Voice and Equality': Young People's Politics in the European Union.” West European Politics 36 (3): 1–23.

- Sloam, J. 2016. “Diversity and Voice: The Political Participation of Young People in the European Union.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 18 (3): 521–537.

- Snell, P. 2010. “Emerging Adult Civic and Political Disengagement: A Longitudinal Analysis of Lack of Involvement with Politics.” Journal of Adolescent Research 25 (2): 258–287.

- Soler-i-Marti, R., and M. Ferrer-Fons. 2015. “Youth Participation in Context: The Impact of Youth Transition Regimes on Political Action Strategies in Europe.” The Sociological Review 63 (S2): 1–260. p. vii–viii.

- Spannring, R., G. Ogris, and W. Gaiser. 2008. Youth and Political Participation in Europe: Results of the Comparative Study of EUYOUPART. Opladen: Barbara Budrich.

- Stoker, G. 2006. “Explaining Political Disenchantment: Finding Pathways to Democratic Renewal.” The Political Quarterly 77 (2): 184–194.

- Stolle, D., and M. Hooghe. 2009. “Shifting Inequalities? Patterns of Exclusion and Inclusion in Emerging Forms of Participation.” European Societies 2011: 1–24. iFirst.

- Tatalovic, M. 2015. “ Think Young People Aren’t Interested in Politics? You’ll be Surprised.” http://horizon-magazine.eu/article/think-young-people-aren-t-interested-politics-you-ll-be-surprised_en.html.

- Tenn, S. 2007. “The Effect of Education on Voter Turnout.” Political Analysis 15 (4): 446–464.

- Teorell, J., M. Torcal, and J. R. Montero. 2007. “Political Participation: Mapping the Terrain.” In Citizenship and Involvement in European Democracies: A Comparative Analysis, edited by J. W. van Deth, J. R. Montero, and A. Westholm, 334–357. New York: Routledge.

- Tilley, J. R. 2003. “Party Identification in Britain: Does Length of Time in the Electorate Affect Strength of Partisanship?” British Journal of Political Science 33 (2): 332–344.

- Torcal, M., and J. R. Montero. 2006. Political Disaffection in Contemporary Democracies: Social Capital, Institutions and Politics. London: Routledge.

- Torney-Purta, J. 2009. “International Psychological Research That Matters for Policy and Practice.” American Psychologist 64 (8): 825–837.

- Van Deth, J. W. 2001. “ Studying Political Participation: Towards a Theory of Everything?” Paper presented at the Joint Sessions of Workshops of the European Consortium for Political Research, Grenoble, April 6–11.

- Vecchione, M., and G. V. Caprara. 2009. “Personality Determinants of Political Participation: The Contribution of Traits and Self-Efficacy Beliefs.” Personality and Individual Differences 46 (4): 487–492.

- Verba, S., and H. N. Ni. 1972. Participation in America. New York: Harper and Row.

- Verba, S., N. Nie, and J. Kim. 1978. Participation and Political Equality: A Seven-Nation Comparison. London: Cambridge University Press.

- Verba, S., K. Schlozman, and H. Brady. 1995. Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. London: Harvard University Press.

- Wilkinson, H., and G. Mulgan. 1995. Freedom’s Children: Work, Relationships and Politics for 18–34-Year Olds in Britain Today. London: Demos.

- Wring, D., M. Henn, and M. Weinstein. 1999. “Young People and Contemporary Politics: Committed Scepticism or Engaged Cynicism?” British Elections & Parties Review 9 (1): 200–216.