ABSTRACT

Existing research on youth political engagement indicates that adolescents have become dealigned from politics. However, according to cognitive mobilization theories, adolescents may not have turned away from politics per se, but found new avenues for political engagement. We involved adolescents in a citizen science project and investigated the roles of different societal actors in providing such new avenues. A total of 67 adolescents searched for political participation calls in their environment (N = 285). They documented and evaluated each observation via an online coding tool. As each observation is nested within individuals, we ran multilevel regressions. In line with the dealignment hypothesis, the participants rated participation offers from political candidates and parties as least interesting and least identified with such actors. By contrast, they highly identified with citizen movements and perceived their issues as most relevant. High identification with the actor and perceived issue relevance significantly increased the likelihood of participation. In line with cognitive mobilization, adolescents may thus not lack political motivation. However, traditional actors fail to respond to their identity needs and interests.

It is a well-documented phenomenon that the willingness to participate in conventional forms of political participation is very low, especially among the younger generation (Zukin et al. Citation2006; Doherty, Keeter, and Weisel Citation2014). This phenomenon is particularly evident in the low turnout among the young in most democratic countries (Bastedo Citation2015; Moeller, Kühne, and De Vreese Citation2018). According to the dealignment hypothesis, young people have become increasingly detached from traditional institutions and reluctant to participate through institutional channels. This process of dealignment has often been explained with a general political disengagement and increasing apathy among young people (e.g. Henn, Weinstein, and Forrest Citation2005; Loader, Vromen, and Xenos Citation2014). In recent years, however, new forms of participation have emerged, which have spurred hopes of re-connecting young people to the political sphere (Heiss and Matthes Citation2016; Raby et al. Citation2018). Youths are more likely to sign online petitions or share political posts on social media and perform these activities more frequently compared to older individuals (Painter-Main Citation2014). However, we know little about what kind of societal actors actually provide participation offers that speak to the interests and identities of young people. This is a critical question because recent research indicates that the provision of accessible and effective channels for participation are not only important as direct means for action but can also stimulate the development of political efficacy and trust (Gerodimos Citation2008; Heiss and Matthes Citation2016).

To study young people’s political participation, scholars have overly relied on self-reported data from surveys, including open- (Quintelier Citation2007; Harris, Wyn, and Younes Citation2010) and closed-ended questions (e.g. scales; Bakker and de Vreese Citation2011; Bode Citation2012). Using scales in such surveys, people are asked whether they have performed certain activities during a given time period. However, such self-reported closed questions have been criticized, most importantly, because individuals tend to overreport their behavior due to social desirability (Persson and Solevid Citation2014). Similarly, working with open-ended questions may lead to underreporting because it is very hard to remember single political activities that date back several months (Heiss and Matthes Citation2017). Moreover, people have become more and more reluctant to respond to traditional methods of social science in general (Groves and Peytcheva Citation2008). All this suggests that there is a need for alternative data collection approaches. One such approach is citizen science.

In citizen science, young people become active observers of their own environment and collect data based on a research question (Heiss and Matthes Citation2017). This is especially helpful in a new context in which political information and participation have become highly personalized and are hence no longer accessible without the help of engaged citizens. Citizen science might therefore shed light on how political participation offers are communicated to a specific group, in our case, adolescents and young adults. Thus, we are able to sample participation offers of different societal actors and evaluate whether these offers are successful in stimulating youth engagement. Compared to traditional in situ methods, a citizen science approach requires active citizens. This is especially important when it comes to political participation because exposure to participation offers in everyday life is expected to be rare. A sufficient number of observations can be achieved only if citizens actively search for participation offers and report as well as evaluate them in situ. Thus, this study can provide insights on how involved young citizens are searching for political participation opportunities. Additionally, we can see if involved adolescents find attractive ways to engage politically.

Over a period of one month, we asked young people to screen their environment for political participation offers, categorize them via a mobile project website, and evaluate the issues and initiators of the offers. Furthermore, respondents reported whether they participated or intended to do so in the offers they collected. Based on these data, we investigated which actors might be most successful in addressing youth issues and identities and may thus successfully engage young people into political action. Therefore, using a citizen science approach may contribute to answering a pressing question: What is the best approach to foster the political participation of young people?

Theoretical framework

Young people’s active participation is crucial in a democratic society. However, when comparing older and younger generations, studies show that younger people are less interested in, have less knowledge about, and are less likely to participate in traditional party politics (Furlong and Cartmel Citation2007; Bennett Citation2008). For example, in many European countries, young people are less likely to vote compared to the older generation, and young people’s membership in political parties has been rapidly decreasing and is now stuck at very low rates (Hooghe, Stolle, and Stouthuysen Citation2004; Furlong and Cartmel Citation2007). In Austria specifically, young people are allowed to vote at the age of 16. However, the turnout among young people remained comparably low (Wagner, Johann, and Kritzinger Citation2012). Thus, the opportunity to vote may not necessarily lead to youth mobilization. Moreover, studies show that young people have more negative attitudes toward politics and specifically less trust in the political system (Quintelier Citation2007; Henn and Foard Citation2012). These trends indicate some support for the pessimistic, disaffected citizen frame, which describes the young generation as politically detached and apathetic (Kimberlee Citation2002; Henn, Weinstein, and Forrest Citation2005; Wattenberg Citation2015).

Against these assumptions, another paradigm challenges the described development in the young generation. According to cognitive mobilization assumptions, young people have not become politically detached per se. In fact, they may only have become detached from traditional political institutions and actors, such as political parties and politicians who represent these institutions (Dalton Citation2007; Cammaerts et al. Citation2014). However, they may not have completely turned away from politics. There are different explanations for this phenomenon. One explanation is that this is because higher education among young people and increasing digital skills may lead to a better ability to access and process political information (Dalton Citation2007). Furthermore, the Internet provides a new low-threshold environment for political information and alternative forms of participation (Bennett and Segerberg Citation2011; Raby et al. Citation2018). Thus, the observed institutional detachment may be simply a symptom of a new lifestyle.

In line with the cognitive mobilization assumptions, qualitative research indicates that young people are still interested in social and political issues. However, the ‘location’ of political engagement changed (Farthing Citation2010; Raby et al. Citation2018). Most importantly, young people shifted from traditional ‘dutiful’ forms of political participation to more individualized and ‘self-actualizing’ forms of engagement (see Dalton Citation2009; Bennett and Segerberg Citation2011; Vromen, Xenos, and Loader Citation2015). This means young people do not use traditional collective channels for participation (e.g. work in political parties) simply because of their existence. Instead, they turn to ad-hoc, issue-based political activities that represent their individual identities and do not require long-term organizational commitment (Vromen, Xenos, and Loader Citation2015). This change has especially been pushed by the emergence of social media, which has become the most important source for young people’s political engagement (Heiss and Matthes Citation2016).

Traditional political actors have not kept up with other societal actors in adapting their political communication. For example, Gerodimos (Citation2008) analyzed government and non-governmental youth websites and concluded that ‘the majority of “youth” sites originating at the heart of the political system lack moral, ideological or political purpose and content, present navigational problems and host “ghost” communities’ (Gerodimos Citation2008, 983). Wells (Citation2014) found that independent online organizations were more likely to provide participatory opportunities than offline-oriented government youth organizations (see also Heiss, Schmuck, and Matthes Citation2018). This is problematic, because cognitive mobilization requires effective channels for political participation. For example, many young people feel that political decision-making should become more participatory, for instance, via means of direct democracy (e.g. referenda Cammaerts et al. Citation2014). In other words, young people wish for more opportunities to express their opinions and partake in political decisions.

In our study, we follow this second paradigm. We investigate whether traditional actors (parties and politicians) keep up with this new development and provide attractive participation channels to young people or leave the political engagement of young people in the hands of other societal actors, such as NGOs, the media or youth organizations. Based on the democratic paradox, young citizens most likely criticize traditional politics and the political system, but, however, still hold highly ambitious and idealist notions about democratic participation (Bruter and Harrison Citation2009).

Hypotheses

There is reason to believe that young people turn away from traditional political actors because they do not deal with issues they care about (Zukin et al. Citation2006; Farthing Citation2010; Atkinson Citation2012). However, one of the most important foundations for political participation is involvement with the issue at hand. Therefore, if traditional political actors fail to provide youth-relevant issues, adolescents may become less willing to engage. Henn, Weinstein, and Wring (Citation2002) argue that young people’s nonparticipation in traditional forms of politics is due to the failure of politicians to address youth issues, that is, issues relevant to their lives. Young people may only engage with political issues that they perceive as personally important. Quintelier (Citation2007) found that, overall, more than 75 percent of young people have the impression that politicians do not know about young people’s interests and concerns. Thus, they do not provide issues that are important for adolescents. Overall, young people are specifically interested in political issues that are often not addressed by institutional politics, such as equality, human rights, and consumer politics (Zukin et al. Citation2006; Farthing Citation2010; Atkinson Citation2012).

Hence, we argue that political participation offers from traditional political actors – which we define as political parties, politicians, and traditional interest groups (i.e. labor unions/economic chambers) – deal with political issues that hardly speak to the interests of young people.

H1: Adolescents perceive issues from traditional political actors (e.g. political parties and candidates) as less important compared to issues from other societal actors (e.g. NGOs).

First, young people tend to be highly critical about traditional representatives (Henn, Weinstein, and Forrest Citation2005; Henn and Foard Citation2012). Henn and Foard (Citation2014) show that adolescents describe traditional politics as ‘boring’ and ‘corrupt’. Additionally, they describe the system as remote and overly centralized. Second, young people avoid long-term organizational commitments and have become more pragmatic about the issues and causes they support. Thus, young people are often described as ‘self-actualizing citizens’ (Bennett Citation2003) or ‘everyday makers’ (Bang Citation2005). Third, Harris, Wyn, and Younes (Citation2010) found that young people avoid institutional channels and try to make a change by modifying their own behavior (e.g. recycling, donating, signing a petition). Overall, the disengagement from governments and political parties leads to a more self-expressive participatory practice (see Vromen, Xenos, and Loader Citation2015). Participation has become informal, individualized, and takes the form of everyday activities (Harris, Wyn, and Younes Citation2010). In such a context, traditional political parties, with their binding party manifestos and programs, no longer speak to the self-actualizing identity of young people.

Furthermore, the younger generation wishes for more opportunities to participate in decisions taken from traditional politics. Since the younger generation has the impression that political parties do not want to take their opinion into account via more direct forms of democracy (Cammaerts et al. Citation2014), we argue that young people may have learnt that traditional political organizations may provide little space for their political input. Hence, young people have become less likely to identify with a political party or its candidates (Henn, Weinstein, and Forrest Citation2005; Henn and Foard Citation2012). Instead, young people may rather identify with other societal actors, such as citizen-driven movements or NGOs, which do not require any long-term commitment, are more open for their political input, and thus speak more strongly to their identities.

H2: Adolescents identify less with traditional political actors (e.g. political parties and candidates) compared to other societal actors (e.g. NGOs).

However, even though single-issue evaluation may have become more important (Henn, Weinstein, and Wring Citation2002; Zukin et al. Citation2006; Atkinson Citation2012), some level of identification with an initiating actor may still remain a prerequisite for getting engaged (Henn, Weinstein, and Forrest Citation2005). In fact, there is a whole body of research which indicates that identification with a source is a key prerequisite for individuals’ susceptibility to political information (e.g. Henn and Foard Citation2014; Heiss and Matthes Citation2016). For example, Heiss and Matthes (Citation2016) provide empirical evidence that young people may only become mobilized by a politician’s participation offers when they identify with the specific politician. Thus, identification with the initiating actor may be an important prerequisite for young people to become engaged politically. Since self-actualization in a political context includes expressing one’s identity by means of political action, the issues at hand, as well as identification with the political actors, seem important for the process of self-actualization (Vromen, Xenos, and Loader Citation2015). Based on recent research, we argue that the importance of the issue, as well as identification with the sender of the political offer, might mobilize adolescents to engage politically. Using a citizen science approach, we aim to investigate both processes.

H3: Perceived issue importance (a) and identification with the actor (b) increase the likelihood of participation.

H4: The relationship between actor type and political participation is mediated by a) perceived issue importance and b) identification with the actor.

Method

A citizen science approach

In this paper, we present results from a citizen science youth project called ‘Political Participation Observer’. In citizen science, volunteers contribute to the scientific process, such as by collecting, analyzing, or interpreting data (Bonney et al. Citation2009). From an educational perspective, volunteering in such projects may contribute to active citizenry, for example, because volunteers observe their social environment by asking scientific questions and using scientific techniques. Because of this promising educational component, an increasing number of citizen science projects have been conducted lately with school students, though most of them in the natural sciences (Mueller and Tippins Citation2012; Ballard, Dixon, and Harris Citation2017; Heiss and Matthes Citation2017). However, such projects may also have great innovative potential in the field of the social sciences. The social sciences ask questions that are closely related to the everyday lives of people, and many social science methods can be easily adapted to citizen science (see Heiss and Matthes Citation2017).

Citizen science is a multifaceted concept, describing a method, a movement, or a social capacity (Eitzel et al. Citation2017). In our research, all three dimensions are relevant. Citizen science is, of course, a methodological tool to gain new insights that are unattainable with traditional methods. However, it also includes parts of a movement because it engages a community of students. This community gains new information on political participation offers in Austria and is likely to disseminate this new information to others. Finally, it produces social capacity because adolescents are searching for political offers online and offline. Therefore, citizen science also empowers a specific community.

The key element of citizen science is that the participating students are no longer passive objects, but active researchers. In fact, we identify two key criteria a citizen social science project needs to fulfill: First, participants need to be fully informed about the project’s research question and goals. Second, their activity in the project needs to be active rather than passive. Using a citizen science approach might lead to better insights into how adolescents engage politically because it involves their actual political environment.

Adolescents actively scan their environment. Thus, we do not have to ask if they would like to engage in hypothetical political offers. In this project, young people become active in sampling a large number of real participation offers, evaluate their sources and content and assess whether to participate in such offers. Therefore, as recommended in a literature review in the area of citizen science research (Eitzel et al. Citation2017), our project can be described as a participatory, active youth citizen science project. Such insight would not be possible when using surveys or even conventional experience sampling methods as a research method.

The project

In the project ‘Political Participation Observer’, adolescents in Austria actively screened their environment, collected political participation offers (both online and offline) and categorized and evaluated these offers via an online coding tool. To make sure all participants in the study had the same definition of political offers, we provided a description (i.e. ‘Political participation is simply the active engagement of citizens in political processes and includes all activities of citizens which may influence political decisions’) as well as examples of political participation opportunities (e.g. voting, taking part in a demonstration, signing a petition, etc.) on the website. The online coding tool was basically a subpage of the mobile website on which participants could categorize and upload pictures of their observed participation offers. Interested school classes (teachers or class representatives) could sign up for participation and received their account information through which each student could log into the website and participate. Besides the categorization of the collected data, we also provided an online discussion forum, in which the students provided feedback to the data collection process and discussed political issues that were provided by the research team. To stimulate project participation, we also announced awards for the most engaged three classes. We assessed the project engagement by counting the number of qualitative data contributions.

In this study, we are primarily interested in the role of different societal actors as initiators of the observed participation offers in Austria. First, we investigate the role of civil society actors, including individual citizens (e.g. on social media), citizen movements (NGOs or citizen associations), and the media. We define the media as civil society actors because it is not controlled by any political parties or state organization. Second, we investigate the role of traditional political actors, including politicians and political parties, government bodies and agencies, and traditional interest groups. We define traditional interest groups as the labor union and economic chamber organizations that are the most important interest groups in Austria. They are tightly tied to the major political parties and are thus not independent from state-led organizations. Finally, we also investigate student organizations, which may be treated as a special category, because some student organizations may be affiliated with a political party while others may not.

Implementation

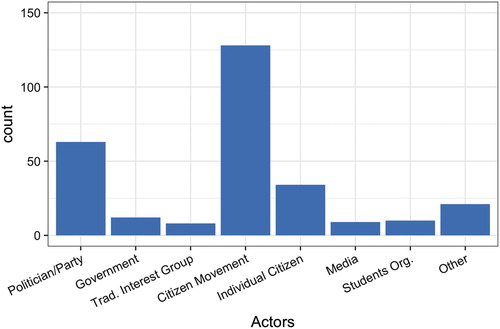

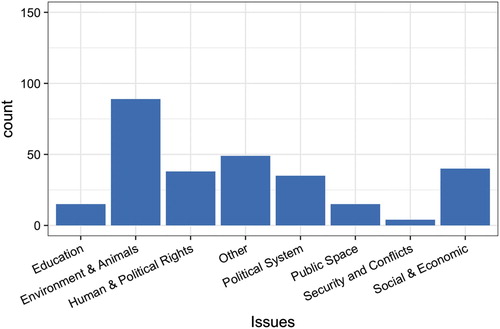

We contacted history and political education teachers in Austria and asked them to enroll their classes in our citizen science project. Overall, students from seven schools and seven classes in urban and rural areas of Austria were willing to participate in the project. However, this sample is not fully representative of Austrian youth because participation was voluntary, and the participating schools did not represent the full diversity of the Austrian school system. The main task for the students was to collect offers for political participation and report their observations via an online tracking tool. First, they could describe the offer in their own words. In a second step, they had to upload a picture of the offer (e.g. screenshot or photo). Then they had to categorize the offer in terms of the issue (see ), the actor (see ), and personally evaluate the actor (identification) and the issue (perceived importance). Furthermore, they stated whether they do or do not want to participate in the offer or if they have already participated or will do so for certain. In 28.42 percent of the reported observations, students reported that they have participated or will do so for sure.

Participants

Overall, 67 adolescents from Austria from different kinds of high schools and between the ages of 16–18 years engaged in this participatory study. This age group is important since adolescents are allowed to vote at the age of 16 in Austria. Students collected a total of 285 political participation offers and categorized them as described above. In addition to the citizen science component, we distributed voluntary online questionnaires to students interested in participating. However, as collecting personal data was not our primary goal in this study, completion of the questionnaire was voluntary, and some students who were engaged in the data collection opted out from the survey part. 72 percent completed the questionnaire. According to these data, we may infer that the citizen scientists were primarily female (11.34 percent of survey respondents were male). Additionally, four out of the seven classes participating in the study came from urban areas in Austria. However, most data were collected from the adolescents from rural areas (91.23 percent).

Measurements

We recoded the issue and actor variables based on the uploaded pictures and students’ descriptions of the offer. We conducted reliability tests among three independent coders on a subsample of 30 posts, yielding sufficient reliability scores for issues (Krippendorff’s alpha = 0.71) and actor (Krippendorff’s alpha = 0.73). We also slightly adapted and refined the initial categories used so the new categories would better match the actual data collected.

To measure participants’ assessment of the issue of the participation offer, we asked, ‘How important is the political theme of the political offer for you personally?’. The adolescents rated their answers on a five-point scale (‘not important at all’ = 1; ‘very important’ = 5). To assess how strongly the adolescents identified with the actor of the participation offer, the participants were asked, ‘How strongly do you identify with the initiator of the participation offer?’. The adolescents rated their answers on a five-point scale (‘not at all’ = 1; ‘very much’ = 5).

Political participation was measured with the question, ‘Will you participate in the offer?’. Adolescents could either chose ‘I have participated already’, ‘Yes, I’m going to participate for sure’, ‘I don’t know if I want to participate’, or ‘No, I don’t want to participate’. We later dummy-coded the answers (‘I don’t know if I want to participate in the study’, ‘No, I don’t want to participate’ = 0; ‘I have participated already’, ‘Yes, I would like to participate for sure’ = 1).

Results

Descriptive findings

indicates that the students in this sample collected participation offers primarily from citizen movements (NGOs or citizen associations). In fact, 44.44 percent of all collected participation offers were provided by citizen movements; 21.88 percent of all offers came from traditional party organization or party candidates, and 11.93 percent of all offers were initiated by individual citizens (see ). Other actors played a comparably minor role. Most of the offers were related to issues such as the environment and animal protection (31.23 percent); 14.04 percent were related to social and economic policies, 13.33 percent were related to human and political rights, and 12.28 percent to questions of the political system.

Hypotheses testing

In the next step, we ran a series of multilevel regression analyses. We ran random-intercept regression models to deal with the nested data structure (i.e. one student may have collected several observations; see Gelman and Hill Citation2007). The results are shown in . We only present the fixed effects because the random effects may be biased since some individuals in our sample collected only one observation (Gelman and Hill Citation2007, 275–76).

Table 1. Multilevel logistic regression predicting participation from Initiator (reference group = Politician/Party) in Model 1 and additionally from perceived issue importance and identification with the initiator in Model 2.

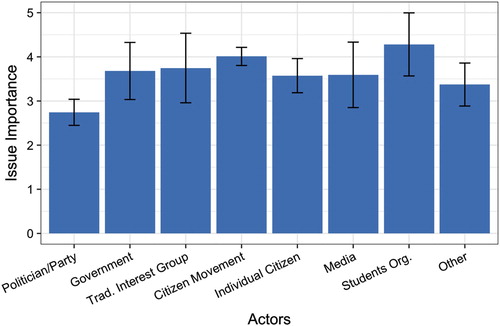

Model 1 in shows the results of the regression analyses. Note that the actor variables represent a categorical variable, and we used ‘political party or candidate’ as the reference category. In H1, we assumed that political offers provided from traditional actors (i.e. parties and candidates, government bodies and agencies, traditional interest groups) would score worse in issue importance compared to civil society actors (i.e. individual citizens, citizen movements, the media). Model 1 in shows the results for issue importance. Results indicate that offers from political parties or political candidates score the worst in terms of perceived issue importance. They score significantly lower compared to all other actors, including other traditional political actors. It should be noted that the differences range from 0.63 points (other actors) to 1.27 (citizen movements). From a substantial perspective, a one-point increase equalizes a 20 percent increase on the five-point scale we used. However, as we are relying on a relatively small sample size, these values come with some uncertainty, which is why we also present the 95 percent confidence intervals in . In addition, we found that offers from government actors or traditional interest groups did not score significantly lower on issue importance than offers from civil society actors, as the overlapping confidence intervals in indicate. Therefore, we found partial support for H1. Finally, it is also noteworthy that citizen movements and student organizations scored comparably high on perceived issue importance. Citizen movements scored significantly higher compared to political actors, individual citizens and ‘other actors’. Offers from student organizations scored significantly higher compared to political actors and ‘other actors’.

Figure 3. Perceived issue importance of participation offers from different types of actors. Error bars indicate 95 percent confidence interval.

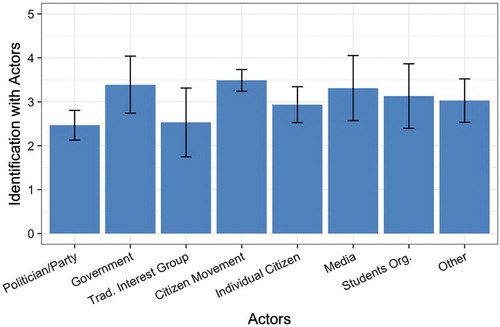

In hypothesis 2, we assumed that adolescents in this sample identify more strongly with civil society actors compared to traditional political actors. We found similar results for identification with the actors as we found for issue importance. Model 2 in shows the results, which are also depicted in . The error bars in indicate the 95 percent confidence intervals. Again, we observed the largest difference compared to citizen movements (1.02 points on the five-point scale). Furthermore, political parties/candidates scored substantially lower on identification than individual citizens and student organizations, but these differences only yielded a marginal level of significance (p < .10). Finally, traditional interest groups scored significantly lower on identification compared to citizen movements (b = 0.96, p < .05). Government actors did not significantly differ from civil society actors, although they did score significantly better than party/candidate actors.

Figure 4. Reported level of identification with different types of actors. Error bars indicate 95 percent confidence interval.

One could also argue that identification with an actor and perceived issue importance are correlated. Thus, in an additional analysis, we tested whether the coefficients change when controlling for actor identification in model 1 and for issue importance in model 2. In both models, actor identification and issue importance are highly significant predictors of each other. Inclusion of the variables also reduces the size and significance of the coefficients. For example, in model 1, citizen movements, individual citizen, and student organization (all vs. political party/candidate) remain significant predictors, but the coefficients of government, media and other actors no longer yield significance. In model 2, when controlling for issue importance, only the coefficient of citizen movements remains significant.

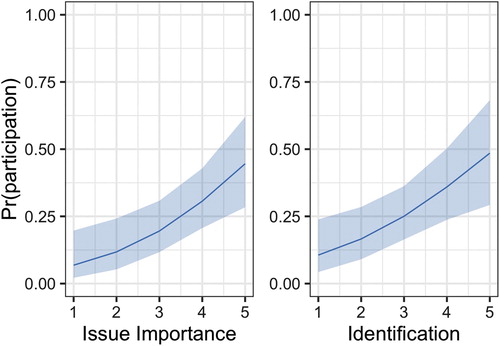

The third model in represents a logistic binary regression with random intercepts. We test whether perceived issue importance (H3a) and identification with the actor (H3b) increase the likelihood of participation. Results show that both perceived issue importance (H3a) and identification with the actor (H3b) increased the likelihood of political participation. shows the predicted probabilities of participation for different levels of perceived issue importance and identification with the actor. For example, an increase of one standard deviation from the mean increases the likelihood of participation from 25.76 percent (lower CI = 17.00, upper CI = 37.05) to 42.04 percent (lower CI = 27.20, upper CI = 58.47). A decrease of 1 standard deviation from the mean decreases the likelihood of participation to 14.25 percent (lower CI = 7.19, upper CI = 26.26). For identification with the actor, an increase of 1 standard deviation from the mean boosts the likelihood of participation from 25.77 (lower CI = 17.00, upper CI = 37.05) percent to 39.88 percent. (lower CI = 25.67, upper CI = 56.03). A decrease of 1 standard deviation from the mean decreases the likelihood of participation to 15.37 percent (lower CI = 7.99, upper CI = 27.54).

Figure 5. Predicted probabilities calculated based on . All covariates in the model are set to their mean values (i.e. proportional values for the dummy variables).

Next, we assumed that the degree to which different actors stimulate participation was mediated by perceived issue importance (H4a) and actor identification (H4b). To test this notion, we calculated the indirect effects based on the regressions in . We used the mediation package in R to calculate Quasi-Bayesian confidence intervals for indirect effects based on 5,000 Monte Carlo simulations (see Imai, Keele, and Tingley Citation2010; Tingley et al. Citation2014). As participation is a binary variable, the coefficients represent the increase in probability of participation (Tingley et al. Citation2014). Again, we use political party/candidate as the reference category for our analysis. Findings of the mediation analysis are shown in . The results indicate that the effects of the initiators (i.e. all other actors vs. political party/candidate as the reference category) are all significantly mediated via perceived issue importance.

Table 2. Indirect effects of actor via issue importance and identification with actor on political participation.

We also calculated the proportion of the total effect mediated (= mediation effect divided by the total effect, see Mascha et al. Citation2013). It should be noted that we find somewhat inconsistent effects for government actors. While individuals found their issues more appealing and identified more strongly with such actors, the total and direct effects on participation were negative (though not significantly). One explanation could be that government actors provide attractive participation offers to young people. However, these offers may be very specific (such as political education programs), and the process of participation may be comparably complicated (e.g. schools have to sign up).

Finally, we also performed mediation analyses to investigate whether government actors or traditional interest groups were less likely to stimulate participation via identification and issue importance compared to civil society actors. We only found significant differences between traditional interest group actors and citizen movements. To be precise, citizen movements were more likely than traditional interest groups to stimulate participation via identification (lower CI = 0.006, upper CI = 0.17) and issue importance (lower CI = 0.009, upper CI = 0,17).

Additional findings

We also looked at whether there were differences between online and offline participation offers (Krippendorff’s alpha = 0.72). We found that our results do not change when controlling for whether the participation offers relate to online or offline activities. We also found that the provision of online participation offers did not affect students’ perceived issue importance. However, the provision of offline offers was highly significantly negatively related to actor identification (b = −50, p < .001). Furthermore, students were less likely to participate in offline offers (b = −1.54, p < .01).

Discussion

Our findings provide support for an increasing political detachment from traditional political institutions on the one hand, and cognitive mobilization and the increasing importance of non-institutional political participation (Bennett and Segerberg Citation2011) on the other. This indicates that these two views may not be mutually exclusive; that is, detachment from traditional institutions may not necessarily and directly be related to general political apathy. Thus, our findings support the notion that young people are not detached from politics per se, but from the political representatives, who do not provide relevant issues for them (Quintelier Citation2007). Young people have to redefine the ‘political’ by turning to alternative sources and spaces for political engagement. However, as the young generation will be the future leaders of our democratic countries, political representatives are well-advised to react to their needs and provide more tangible channels for political participation that speak to the issues, interests and identities of adolescents (Henn, Weinstein, and Forrest Citation2005; Harris, Wyn, and Younes Citation2010).

We have argued that young people need to develop a certain level of identification with an actor and appraise their issues as relevant in order to actively engage with their participation offers. In line with this theorizing, we found that public actors need to provide appealing political issues and speak to young people’s identities in order to stimulate youth political engagement. The most critical finding of this study is that traditional political actors, political candidates, and parties specifically, lag behind in providing meaningful political participation channels for young people in our sample of Austria. In fact, adolescents in our sample perceived the issues from candidates and parties as the least important and identified least (with the exception of traditional interest groups, which also scored poorly) with such actors. Instead, young people identify more strongly with other civil society actors, most importantly, citizen movements that perceived their issues as more important, and hence were more likely to participate in their offers.

The mediation analysis indicated that both perceived issue importance and identification with the actors can explain why young people may have become reluctant to engage with political parties and candidates. Perceived issue importance exerted the most impactful mediating role and explained lower rates of political participation in offers from party and candidate actors compared to all other actors. For example, 61 percent of the total difference in participating in offers from citizen movements (vs. party/candidates) was mediated via issue importance, and 64 percent of the effect of student organizations (vs. party/candidates) was mediated via issue importance. In fact, one could argue that this is an optimistic finding, because the provision of youth-oriented issues is a comparably easy task, but, of course, requires political will. By contrast, building identification is a long-term goal and certainly also related to the frequent provision of appealing issues. Overall, the results strongly suggest that political parties and candidates need to adapt the way they speak to young people in Austria. Most importantly, institutional actors have to relate their work more strongly to the lives of adolescents, provide appealing issues and create images and organizations young people can identify with.

An additional analysis also revealed that the low issues importance and identification scores of political candidates and parties remained robust even when controlling for online/ offline participation. Interestingly, whether an offer related to an offline (rather than an online) activity did not affect young people’s perceived issue importance. However, the provision of offline activities was negatively related to the perceived identification with the actor. This may indicate that actors who provide offline participation offers only can hardly speak to young people’s identities anymore. Overall, it has to be mentioned that the results described here are both time- and context-specific. However, they are still in line with findings from other democratic countries.

Limitations and further research

The sample is not fully representative. Furthermore, additional data would be helpful to get a better understanding of the effect sizes. Additionally, we did not ask if the adolescents knew the initiator of the political participation offer, which could have been interesting for the individual citizen category. Perhaps adolescents identify more with initiators because the adolescents know them personally or because they are public figures, such as influencers or bloggers. Overall, the extent of identification with such initiators would be an interesting avenue for further research.

Conclusion

This study is one of the first to investigate adolescents’ political engagement using a citizen science approach. Since many authors criticized the survey approach to study young people’s political participation (e.g. Heiss and Matthes Citation2017), citizen science studies reveal important new insights into adolescents’ political environments. Our findings suggest that political parties were least successful in addressing youth issues and identities. Thus, political parties need to change their ways of speaking to young people and provide more efficient channels for youth engagement. Only then may parties increase the overall political participation of young people – which is a key prerequisite for the success of our future democracies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Atkinson, Lucy. 2012. “Buying in to Social Change: How Private Consumption Choices Engender Concern for the Collective.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 644 (1): 191–206. doi:10.1177/0002716212448366.

- Bakker, Tom P., and Claes H. de Vreese. 2011. “Good News for the Future? Young People, Internet Use, and Political Participation.” Communication Research 38 (4): 451–470. doi:10.1177/0093650210381738.

- Ballard, Heidi L., Colin G. H. Dixon, and Emily M. Harris. 2017. “Youth-focused Citizen Science: Examining the Role of Environmental Science Learning and Agency for Conservation.” Biological Conservation 208: 65–75. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2016.05.024.

- Bang, Henrik P. 2005. “Everyday Makers and Expert Citizens. Building Political not Social Capital.” In Remaking Governance: Peoples, Politics and the Public Sphere, edited by Janet Newman, 159–179. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Bastedo, Heather. 2015. “Not ‘One of Us’: Understanding How Non-engaged Youth Feel About Politics and Political Leadership.” Journal of Youth Studies 18 (5): 649–665. doi:10.1080/13676261.2014.992309.

- Bennett, W. Lance. 2003. “Civic Learning in Changing Democracies.” In Young Citizens and New Media: Learning for Democratic Participation, edited by Peter Dahlgren, 59–78. New York: Routledge.

- Bennett, W. Lance. 2008. “Changing Citizenship in the Digital Age.” In Civic Life Online: Learning how Digital Media Can Engage Youth, edited by W. Lance Bennett, 1–24. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Bennett, W. Lance, and Alexandra Segerberg. 2011. “Digital Media and the Personalization of Collective Action.” Information, Communication and Society 14 (6): 770–799. doi:10.1080/ 1369118X.2011.579141 doi: 10.1080/1369118X.2011.579141

- Bode, Leticia. 2012. “Facebooking It to the Polls: A Study in Online Social Networking and Political Behavior.” Journal of Information Technology & Politics 9 (4): 352–369. doi:10.1080/19331681.2012.709045.

- Bonney, Rick, Caren B. Cooper, Janis Dickinson, Steve Kelling, Tina Phillips, Kenneth V. Rosenberg, and Jennifer Shirk. 2009. “Citizen Science: A Developing Tool for Expanding Science Knowledge and Scientific Literacy.” BioScience 59 (11): 977–984. doi:10.1525/bio.2009.59.11.9.

- Bruter, Michael, and Sarah Harrison. 2009. “The Future of Our Democracies?” In The Future of our Democracies: Young Party Members in Europe, edited by Michael Bruter and Sarah Harrison, 223–239. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cammaerts, Bart, Michael Bruter, Shakuntala Banaji, Sarah Harrison, and Nick Anstead. 2014. “‘The Myth of Youth Apathy: Young Europeans’ Critical Attitudes toward Democratic Life.” American Behavioral Scientist 58 (5): 645–664. doi:10.1177/0002764213515992.

- Dalton, Russell J. 2007. “Partisan Mobilization, Cognitive Mobilization and the Changing American Electorate.” Electoral Studies 26 (2): 274–286. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2006.04.009.

- Dalton, Russell J. 2009. The Good Citizen: How a Younger Generation Is Reshaping American Politics. Washington, DC: CQ Press.

- Doherty, Colleen, Scott Keeter, and Ren-Ke Li Weisel. 2014. The Party of Nonvoters: Younger, More Racially Diverse, More Financially Strapped. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

- Eitzel, M., J. Cappadonna, C. Santos-Lang, R. Duerr, A. Virapongse, S. E. West, C. C. M. Kyba, et al. 2017. “Citizen Science Terminology Matters: Exploring Key Terms.” Citizen Science: Theory and Practice 2 (1): 1–20. doi:10.5334/cstp.96.

- Farthing, Rys. 2010. “The Politics of Youthful Antipolitics: Representing the ‘Issue’ of Youth Participation in Politics.” Journal of Youth Studies 13 (2): 181–195. doi:10.1080/13676260903233696.

- Furlong, Andy, and Fred Cartmel. 2007. Young People and Social Change: Individualisation and Risk in Late Modernity. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Gelman, Andrew, and Jennifer Hill. 2007. Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models. Cambridge, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Gerodimos, Roman. 2008. “Mobilising Young Citizens in the UK: A Content Analysis of Youth and Issue Websites.” Information Communication & Society 11 (7): 964–988. doi:10.1080/13691180802109014.

- Greene, Steven. 2004. “Social Identity Theory and Party Identification.” Social Science Quarterly 85 (1): 136–153. doi:10.1111/j.0038-4941.2004.08501010.x.

- Groves, Robert M., and Emilia Peytcheva. 2008. “The Impact of Nonresponse Rates on Nonresponse Bias a Meta-analysis.” Public Opinion Quarterly 72 (2): 167–189. doi:10.1093/poq/nfn011.

- Harris, Anita, Johanna Wyn, and Salem Younes. 2010. “Beyond Apathetic or Activist Youth: ‘Ordinary’ Young People and Contemporary Forms of Participation.” Young 18 (1): 9–32. doi:10.1177/110330880901800103.

- Heiss, Raffael, and Jörg Matthes. 2016. “Mobilizing for Some: The Effects of Politicians’ Participatory Facebook Posts on Young People’s Political Efficacy.” Journal of Media Psychology 28 (3): 123–135. doi:10.1027/1864-1105/a000199.

- Heiss, Raffael, and Jörg Matthes. 2017. “Citizen Science in the Social Sciences: a Call for More Evidence.” GAIA-Ecological Perspectives for Science and Society 26 (1): 22–26. doi:10.14512/gaia.26.1.7.

- Heiss, Raffael, Desiree Schmuck, and Jörg Matthes. 2018. “What Drives Interaction in Political Actors’ Facebook Posts? Profile and Content Predictors of User Engagement and Political Actors’ Reactions.” Information, Communication & Society Advanced Online Publication, 1–17. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2018.1445273.

- Henn, Matt, and Nick Foard. 2012. “Young People, Political Participation and Trust in Britain.” Parliamentary Affairs 65 (1): 47–67. doi:10.1093/pa/gsr046.

- Henn, Matt, and Nick Foard. 2014. “Social Differentiation in Young People’s Political Participation: The Impact of Social and Educational Factors on Youth Political Engagement in Britain.” Journal of Youth Studies 17 (3): 360–380. doi:10.1080/13676261.2013.830704.

- Henn, Matt, Marc Weinstein, and Sarah Forrest. 2005. “Uninterested Youth? Young People’s Attitudes towards Party Politics in Britain.” Political Studies 53 (3): 556–578. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9248.2005.00544.x.

- Henn, Matt, Marc Weinstein, and Dominic Wring. 2002. “A Generation Apart? Youth and Political Participation in Britain.” British Journal of Politics and International Relations 4 (2): 167–192. doi:10.1111/1467-856X.t01-1-00001.

- Hooghe, Marc, Dietlind Stolle, and Patrick Stouthuysen. 2004. “Head Start in Politics: The Recruitment Function of Youth Organizations of Political Parties in Belgium (Flanders).” Party Politics 10 (2): 193–212. doi:10.1177/1354068804040503.

- Imai, Kosuke, Luke Keele, and Dustin Tingley. 2010. “A General Approach to Causal Mediation Analysis.” Psychological Methods 15 (4): 309–334. doi:10.1037/a0020761.

- Kimberlee, Richard H. 2002. “Why Don’t British Young People Vote at General Elections?” Journal of Youth Studies 5 (1): 85–98. doi:10.1080/13676260120111788.

- Loader, Brian D., Ariadne Vromen, and Michael A. Xenos. 2014. “The Networked Young Citizen: Social Media, Political Participation and Civic Engagement.” Information, Communication & Society 17 (2): 143–150. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2013.871571.

- Manning, Nathan. 2013. “‘I Mainly Look at Things on an Issue by Issue Basis’: Reflexivity and Phronêsis in Young People’s Political Engagements.” Journal of Youth Studies 16 (1): 17–33. doi:10.1080/13676261.2012.693586.

- Mascha, Edward J., Jarrod E. Dalton, Andread Kurz, and Leeif Saager. 2013. “Understanding the Mechanism: Mediation Analysis in Randomized and Nonrandomized Studies.” Anesthesia & Analgesia 117 (4): 980–994. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182a44cb9.

- Moeller, Judith, Rinaldo Kühne, and Claes De Vreese. 2018. “Mobilizing Youth in the 21st Century: How Digital Media Use Fosters Civic Duty, Information Efficacy, and Political Participation.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 62 (3): 445–460. doi:10.1080/08838151.2018.1451866.

- Mueller, Michael P., and Deborah Tippins. 2012. “The Future of Citizen Science.” Democracy and Education 20 (1): 1–12.

- Painter-Main, Michael. 2014. “Repertoire-building or Elite-challenging Participation? Understanding Political Engagement in Canada.” In Canadian Democracy from the Ground Up: Perspective and Performance, edited by Elisabeth Gidengil and Heather Bastedo, 62–82. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Persson, Mikael, and Maria Solevid. 2014. “Measuring Political Participation—Testing Social Desirability Bias in a Web-survey Experiment.” International Journal of Public Opinion Research 26 (1): 98–112. doi:10.1093/ijpor/edt002.

- Pirie, Madsen, and Robert M. Worcester. 1998. The Millennial Generation. London: Adam Smith Institute.

- Putnam, Robert D. 2000. “Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital.” In Culture and Politics, edited by Lane Crothers and Charles Lockhart, 223–234. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Quintelier, Ellen. 2007. “Differences in Political Participation between Young and Old People.” Contemporary Politics 13 (2): 165–180. doi:10.1080/13569770701562658.

- Raby, Rebecca, Caroline Caron, Sophie Théwissen-LeBlanc, Jessica Prioletta, and Claudia Mitchell. 2018. “Vlogging on YouTube: The Online, Political Engagement of Young Canadians Advocating for Social Change.” Journal of Youth Studies 21 (4): 495–512. doi:10.1080/13676261.2017.1394995.

- Tajfel, Henri. 1978. “Social Categorization, Social Identity, and Social Comparisons.” In Differentiation between Social Groups, edited by Henri Tajfel, 61–76. London: Academic Press.

- Tingley, Dustin, Yamamoto Teppei, Kentaro Hirose, Luke Keele, and Kosuke Imai. 2014. “Mediation: R Cackage for Causal Mediation Analysis.” Journal of Statistical Software 59 (5): 1–38. ISSN:1548-7660. doi: 10.18637/jss.v059.i05

- Vromen, Ariadne, Michael A. Xenos, and Brian Loader. 2015. “Young People, Social Media and Connective Action: From Organisational Maintenance to Everyday Political Talk.” Journal of Youth Studies 18 (1): 80–100. doi:10.1080/13676261.2014.933198.

- Wagner, Markus, David Johann, and Sylvia Kritzinger. 2012. “Voting at 16: Turnout and the Quality of Vote Choice.” Electoral Studies 31 (2): 372–383. doi:10.1016/j.electstud.2012.01.007.

- Wattenberg, Martin P. 2000. “The Decline of Party Mobilization.” In Parties Without Partisans: Political Change in Advanced Industrial Democracies, edited by Russell J. Dalton and Martin J. Wattenberg, 64–78. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Wattenberg, Martin P. 2015. Is Voting for Young People? New York: Routledge.

- Wells, Chris. 2014. “Two Eras of Civic Information and the Evolving Relationship between Civil Society Organizations and Young Citizens.” New Media & Society 16 (4): 615–636. doi:10.1177/1461444813487962.

- Zukin, Cliff, Scott Keeter, Molly Andolina, Krista Jenkins, and Michael X. Delli Carpini. 2006. A New Engagement? Political Participation, Civic Life, and the Changing American Citizen. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.