ABSTRACT

In recent years, educational systems in Europe have experienced a rise in the number of immigrant youth. The experiences of immigrant youth facing the challenges of an unfamiliar educational system is of continuous relevance in youth studies. This article aims to explore the schooling experiences of 19 immigrant youth in Sweden, focusing on the institutional obstacles they encounter as students in the national educational system. It draws on semi-structured interviews with immigrant youth attending upper secondary school or preparing for it by taking transitional classes. Findings are that familiarity with the majority culture, how the educational system works and how to use the majority language for learning purposes in Sweden constitute crucial knowledge for progress in upper secondary education. However, immigrant students state they have not been adequately prepared for these demands in their transitional classes. The authors suggest acknowledging students’ cultural backgrounds and argue for allowing English parallel to Swedish as a transnational language of communication during a transition period, thereby improving students’ chances of having their embodied cultural capital validated in the upper secondary school system.

Introduction

During the 2010s, with a peak in 2015, many children and young people came to Europe, with Sweden receiving the most migrants per capita in Europe in 2015 (ESPON Citation2015). Among these, approximately 70,000 were children and young people arriving in Sweden seeking asylum (Swedish Migration Board Citation2015). These immigrant youth met a national school system with an institutional approach to newcoming students that was new to them. Against this backdrop, our interest in this article is the experiences of a group of immigrant youth when they entered the Swedish educational system after coming from various educational systems around the world; these students are attending a transitional class or an upper secondary programme.

Given the contemporary context, the aim of this article is to analyse the interplay between a group of immigrant youth and the Swedish educational system at the upper secondary level, from the perspective of immigrant youth. In particular, the article sets out to answer (1) what intentions do students have with their education and (2) what are their experiences of institutional obstacles that risk impeding their educational progress and success?

As research focusing on immigrant youths’ contact with formal schooling in a new society, this study contributes with knowledge on newly arrived immigrant youths’ own experiences of social inclusion and obstacles in the educational system, which is still largely omitted in youth studies (Devine Citation2009; Nilsson Folke Citation2017). Here follows an overview of previous research.

Research overview of immigrant students’ experiences in the educational system

Immigrant youth entering the school system carry with them high aspirations (Atanasoska et al. Citation2018; Jepson Wigg Citation2016; Kalalahti, Varjo, and Jahnukainen Citation2017; Turcatti Citation2018) in combination with an awareness of the importance of education to achieve social inclusion and respect among native inhabitants as well as migrants (Sharif Citation2017). Moreover, aspiring to make friends with native students and to manage the language for educational purposes, immigrant youth find it expedient to learn the majority language (Nilsson Folke Citation2017). Research has also pointed to the importance of creating possibilities for immigrant students to socialise with other students in school in order to facilitate social inclusion and intercultural understanding (De Heer et al. Citation2015; Nilsson and Axelsson Citation2013; Nilsson and Bunar Citation2016; Sharif Citation2017; Skowronski Citation2013; Walton, Priest, and Paradies Citation2013) and to acquire the new language (Allen Citation2006; Feinberg Citation2000).

However, immigrant youth express frustration over not understanding vital subject content communicated in the majority language during school lessons (Nilsson Folke Citation2015). Immigrant students’ inability to use the majority language in school on the same level as native students, leads to the undervaluing of their knowledge in many subjects (Sharif Citation2016). The new language runs the risk of becoming a ‘gatekeeper to the mainstream, rather than a tool for communication and learning’ (Allen Citation2006, 261). In order to counteract and to keep pace, many immigrant students describe themselves working harder than native students (Nilsson and Axelsson Citation2013), and they are aware that it will be difficult for them to succeed in school (Sharif Citation2016). Kalalahti, Varjo, and Jahnukainen (Citation2017) and Hilt (Citation2017) find that it is more common among students of immigrant background to drop out of upper secondary education than it is among the native peer group.

In addition, research from various countries points to teaching in transitional classes that is often rudimentary (Rutter Citation2006), not recognising pre-migratory knowledge and experiences (Hilt Citation2017; Sharif Citation2016) and not connecting between past and present instruction, described as a ‘discontinuous past’ by Nilsson Folke (Citation2017). The instruction in transitional classes seldom also agrees with what is brought up in mainstream courses (Axelsson Citation2015; Nilsson and Bunar Citation2016).

The educational system neglects immigrant youths’ individual resources when viewing them in terms of various deficits (Nilsson and Bunar Citation2016; Rodríguez-Izquierdo and Darmody Citation2017). This has been characterised as a ‘deficit model’, leading above all to a focus on immigrant students’ acquisition of the dominant language of education (Hilt Citation2017; Nilsson and Bunar Citation2016; Nilsson Folke Citation2017; Taylor Citation2008; Torpsten Citation2013). Hilt (Citation2017) adds that Norwegian teachers of immigrant youth consider students lacking both in cultural references needed in formal instruction and in ability to self-manage their learning processes (Hilt Citation2016), which is ascribed to insufficient learning in their home or transit countries. Moreover, Sharif (Citation2017) indicates that lack of knowledge about the national educational system is what defines immigrant youth. However, even though immigrant students have attended mainstream instruction in lower secondary education and aspire to enter mainstream upper secondary classrooms, they are often not accepted and end up in Language introduction, a situation conceptualised by Nilsson Folke (Citation2017) as a ‘postponed future’. Because of prioritising second language learning, students’ development of their knowledge base in mainstream courses is endangered and time for educational careers is lost (Atanasoska et al. Citation2018; Nilsson and Axelsson Citation2013; Skowronski Citation2013).

Nonetheless, curricula worldwide place a demand on schools, such as in Sweden (Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2011), to prepare students for living in and contributing to society, in order to pave the way for immigrant youths’ opportunities in the wider community.

Theoretical approach

In the analysis of immigrant youths’ statements, we draw on Bourdieu’s theory of practice (Citation1974) and its focus on analysis of institutional structures and processes of social reproduction in education (Bourdieu and de Saint Martin Citation1982). This theory is relevant in this study, informing us if and how the Swedish educational system shows indications of posing institutional obstacles to immigrant youth. In other words, whether educational demands experienced by these immigrant youth indicate that immigrant youths’ knowledge, experiences and skills are not fully valued, compared to those possessed by native peers who are fluent in the majority language and brought up in the dominant culture.

Bourdieu (Citation1986) makes a distinction among three forms of capital: economic, social and cultural. Cultural capital can be further divided into embodied, institutionalised and objectified cultural capital (Bourdieu Citation1986). In our analysis, we will make use of social and cultural capital, as well as embodied and institutional cultural capital. Social capital refers to the inclusion of individuals in social networks of connections. Inspired by Bourdieu (Citation1986), we define cultural capital in relation to the educational system as familiarity with the knowledge, experiences and skills that are demanded and valued in upper secondary school.

Bourdieu’s concept of embodied cultural capital refers to cultural resources of an individual that are personally acquired knowledge and skills, accumulated to a large extent in their lives outside school. A student’s embodied cultural capital is crucial for the individual’s academic achievements since it refers to a personal ability to use language forms that are institutionalised and valued in upper secondary education, as well as the personal knowledge demanded in school about the national societal system and history.

Finally, institutionalised cultural capital refers to educational qualifications symbolising competence, such as, a vocational exam or an academic qualification.

In all, Bourdieu’s theory and concepts allow us to discern qualities in demands on knowledge and skills in upper secondary school that risk impeding immigrant youths’ educational progress and excluding their resources.

The Swedish upper secondary educational system

In accordance with national regulations (Secondary School Regulation SFS Citation2010:Citation2039), all young people living in Sweden, who have finished nine years of compulsory school, are entitled to apply to a three-year upper secondary education, if they will begin this education at least six months prior to turning 20. However, immigrant youth must apply before they turn 18. Young immigrants under the age of 18, who do not meet the requirements for acceptance to upper secondary school, attend the Language introduction programme (hereafter referred to as Language introduction). In Language introduction, they are to prepare for the transition to mainstream upper secondary school or other forms of post-compulsory education. This is a heterogenous group of students that includes both asylum-seeking youth and youth with a residence permit, ranging from those with no school experience to those with extensive schooling, but with no or little knowledge of the Swedish language (Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2016b). In Language introduction there are no national diploma goals or any mandatory organisational demands. Language introduction is to offer subjects and courses, both on the primary as well as the lower and upper secondary levels, deemed necessary for the individual (SFS Citation2010:Citation2039). The main purpose is to teach these students Swedish (Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2016a). Other subject courses offered in Language introduction are mathematics, English, natural science, social science, physical education and health. However, a report (Swedish National Agency for Education Citation2016a) states that in more than eight out of 10 schools, very few or no immigrant youth attend mainstream upper secondary courses. In addition, students are entitled to mother tongue education (Secondary School Regulation SFS Citation2010:Citation2039); however, mother tongue education and bilingual scaffolding, even though stipulated in Swedish educational legislation, are under-utilised resources in pedagogical practise, and instead there is a sole focus on learning Swedish (Nilsson and Bunar Citation2016).

Students leave Language introduction when teachers deem them ready. While attending Language introduction, the participating students in this study are not sorted into classes by achievement level, such as, basic and advanced.

The organisational model of language introduction described hitherto, frequently referred to as transitional classes (Nilsson and Bunar Citation2016; Taylor Citation2008), is the most common one in Sweden. These classes can either take place in separate classrooms in a school shared with mainstream classes, as is the case in this study, or on a site physically separated from regular classes. Another model is direct integration in mainstream classes, mostly used for younger children, aged seven to nine (Nilsson and Bunar Citation2016). Though there are other models, having a plethora of models has been discussed among practitioners and researchers as something that might lead to uneven quality in the education of immigrant youth with regard to these youths’ academic and social development (Allen Citation2006; Feinberg Citation2000; Nilsson and Bunar Citation2016).

Finally, to register for a mainstream upper secondary programme, youth are to choose from the 18 national mainstream programmes available, which are divided into 12 vocational programmes and six higher education preparatory programmes. Our study participants were students in two vocational programmes: Child and Recreation, and Health and Social Care, and two higher education preparatory programmes: Natural Science, and Technology.

Methods

Interview context

We conducted semi-structured interviews (Denscombe Citation2016) with 19 immigrant youth. The openness and adaptability of the semi-structured interview allows respondents to share their experiences as a narrative of their education and provides the process of analysis with meaningful data to interpret the youth’s experiences (Kvale and Brinkmann Citation2014). Our interpretations rest on the understanding that the narratives are the youths’ constructions of their everyday life through language, and although being their construction, it is influenced by interactional and institutional elements in their lives outside their control (Holstein and Gubrium Citation2011). Therefore, interpreting the meaning of the youth’s experiences contributes with knowledge about the interplay between the institutional school system and the individual.

The interviews lasted approximately one hour each and took place in two upper secondary schools within the same municipality. Only one student, Sara, chose to be interviewed in English, instead of Swedish. The Swedish transcripts were translated into English as accurately as possible by the researchers.

Participants

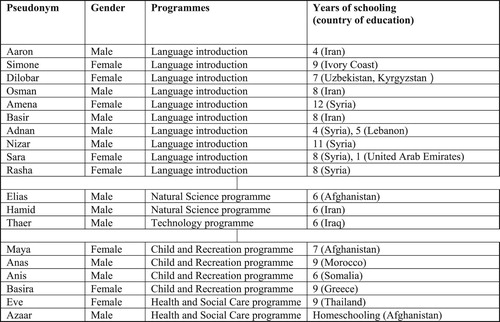

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Vetting Board (Regional Ethical Vetting Board in Linköping, Dnr 2016/285-31), Sweden. The only criteria for inclusion was that half of the students attended Language introduction and the other half attended a national programme of any kind to provide a spectrum of experiences from the entire school system at the upper secondary level. Participants were recruited by the researchers from language introduction classes and national programmes. All students in Language introduction classes were informed about the study, and a letter of information both in English and Swedish with contact information was handed out in their classes. Students in national programmes were recruited with the help of their teachers, who could give their recently immigrated students the information letter, enabling them to familiarise themselves with the project prior to deciding on participation in interviews. Participation was thus voluntary and based on student initiative, and all who contacted us for an interview participated. Participants in the study included a total of 19 students, eleven male and eight female ().

Ten of the interviewed students were attending Language introduction, and these students had studied Swedish for one to two years, except Aaron and Dilobar, who had studied Swedish in lower secondary school for approximately one and a half years. The remaining nine students following a mainstream programme had studied Swedish for four to five years.

Data and analysis

The participants were asked about what situations outside school they expect their education to prepare them for, now and in the future. Other topical areas were the students’ experiences of instruction and their understanding of what knowledge and skills they had learned in school before entering the educational system in Sweden, as well as the students’ experiences of and responses to demands on what to learn in Language introduction and mainstream programmes. Finally, participants were asked about what they see as vital for them to learn in Language introduction and mainstream programmes, including not only important knowledge and skills but also such aspects as individual needs and school friendships.

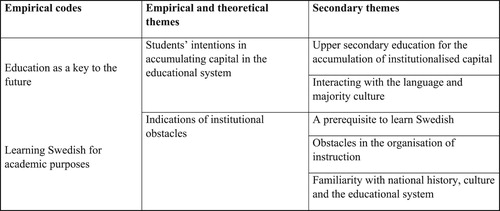

All authors have taken part in a dialectical process going between empirical data and theory, generating themes by abductive reasoning (Alvesson and Sköldberg Citation2017). The abductive process started with all authors reading the interviews individually to gain an overview and find meaningful codes in the data (see ). Next, the authors underwent theoretical considerations of the data, making use of Bourdieu’s concept of capital (Citation1986) to reach an understanding of the codes. Then the empirical data was read again to aggregate overarching themes based on theoretical understanding. Looking for connections and inconsistencies between codes as well as emerging themes, while remaining focused on the study aim, two primary themes were established by all authors: Students’ intentions in accumulating capital in the educational system and Indications of institutional obstacles. The researchers also agreed upon secondary themes within these primary themes.

The selected student quotes referred to in this article indicate qualities in each theme, paving the way for disclosing and analysing the various standpoints among students.

Results

Findings from the interviews will be presented according to the two primary themes: Students’ intentions in accumulating capital in the educational system and Indications of institutional obstacles.

Students’ intentions in accumulating capital in the educational system

Upper secondary education for the accumulation of institutionalised cultural capital

A frequent comment among students in Language introduction and mainstream programmes is that they and their parents argue for upper secondary education as a resource offering access to a prioritised institutionalised cultural capital; for example, many students tell about plans for gaining university degrees by going to upper secondary education. Simone, from Language introduction, describes her mother’s attitude towards her education:

She thinks it is something good, but she tells me to study hard, so that I may get into upper secondary school. She gets really stressed out about this.

Apart from offering possibilities to progress within the national educational system, upper secondary education is described as being of great importance to young people for allowing them institutionalised cultural capital that is not confined to national borders. Thaer, a technology student of Palestinian origin, explains:

They [Thaer’s parents] think that education is the most important thing, because a good, quality education, they say, allows you to live anywhere. It doesn’t matter what happens, but if you do not have that education then you won’t stand a chance, because they experienced war and they had to escape, because [pause] We, Palestinians, are considered stateless people and regardless of where we live, we are always counted as not belonging anywhere sort of [pause] And education is my passport, my father always says.

Finally, an educational diploma is important when considered as a requisite for earning one’s living. Osman, attending Language introduction, thinks upper secondary education will earn him a position in society and, as he expresses it, ‘a good job’. Also Eve, enrolled in the Health and Social Care programme, sees a connection between vocational education and employment, knowing from her mother that she must have a good education, so that she can find a job and support herself one day.

Immigrant youth in this study recognise a long-term value of education in accessing institutionalised cultural capital. This is in keeping with previous research (Atanasoska et al. Citation2018; Devine Citation2009; Nilsson Folke Citation2015; Sharif Citation2016). This study also shows that students aspire to accumulate institutionalised cultural capital, endowing them with resources convertible into economic capital, within or outside country borders.

Interacting with the language and dominant culture

The interviewed students do not limit themselves to arguing for upper secondary education as a resource for the accumulation of institutionalised cultural capital only. Sara, who attends Language introduction, underscores the importance of being in a class with native speakers:

If you are in a class with Swedish people, you will make friends. And when you make friends and you go out of the class, they will talk with each other in Swedish, because they are Swedish. So you would, you would take some words, you can talk with them in Swedish. You can practice your Swedish with them. And they will teach you new words, and you can learn and guess how you can spell them and how can [pause] how they spell, how they speak and things like that.

Basir, Aaron, Nizar and Osman from Language introduction, as well as Azaar from the Health and Social Care programme and Elias from the Natural Science programme, add yet another purpose to communicating in Swedish with native speakers. Basir expresses this intention:

They have been here before us; they know how it all works. How to [pause] the behaviour in society. How to behave in society.

It is to get a better picture of what upper secondary school [pause] is like. If we are to call it ‘the real school’. And to know more about going there, in upper secondary school.

Indications of institutional obstacles

A prerequisite to learn Swedish

Sara expresses succinctly her critique against immigrant youth being excluded from connection with native speakers:

If we had one class with people who speak Swedish, or if you had friends who speak Swedish, you would learn faster and you would learn more than the classes you take. Because you are communicating more.

Parallel to this, all students bring with them previous schooling, including Azaar with home schooling where he learned reading and writing from his parents. Most of them have studied mathematics, language (their mother tongue), history, biology and many times English or French, for at least six years in school. Osman, Nizar, Adnan and Sara reflect upon their studies in Language introduction. Osman concludes that:

I have taken these [courses] before, so it is not hard. So I just try to learn the language. Yes, the language in math, and such.

There are many students who know a lot, but in their own languages.

The knowledge I brought with me could not be used, since it was not in Swedish.

Swedish is [pause] we need to concentrate on the [pause] on the language that we don’t know, so we can move to another stage, so we can learn more.

At the same time, the emphasis on mastering Swedish is at odds with two students’ descriptions of their life prospects. Thaer is going to leave Sweden after upper secondary school to study at an English university. Rasha also has other plans:

I don’t need Swedish; they use English in university, you know, and [pause] I’ll go to Japan then. I’ll learn manga.

Obstacles in the organisation of instruction

At a closer look, when taking different subjects, such as, mathematics, English and biology in Language introduction, all students are aware that they have to learn subject-specific concepts in Swedish. For example, Elias and Anas, the latter attending the Child and Recreation programme, mention that in physics, chemistry and social studies, there are demands on them to learn concepts in Swedish, such as, ‘nucleus’ and ‘bacteria’. This requirement continues in mainstream programmes where there are even more concepts to learn.

However, at the same time, immigrant students have to develop their reading, writing and speaking skills to the level demanded in upper secondary education. Their native peers have already been introduced to these skills in previous education. In line with this, Eve points out that before entering upper secondary mainstream courses, students should practise formal writing:

I think you should learn more, that you should prepare to write a lot [pause]learn how to write reports, and argumentative essays, because it’s also important. But now I [pause] we have to write memos and it’s really hard.

And then it sometimes happened when discussing, that you were told to read and discuss a text, but the teacher didn’t count on anyone having a problem reading, sort of. Five minutes are five minutes, independent of if you are ready or not and then the discussion starts and maybe you don’t want to participate because you haven’t been able to prepare enough. So, you cannot do it.

It is mostly in Swedish class maybe [pause] Swedish and biology, history and geography, that you must be given the opportunity to practise oral presentations. So that you dare to speak in front of people or in front of students.

The organisation of instruction in Language introduction adds further obstacles for these students. Sara states:

So, we need to go fast, we need to learn the language first, so we can go to the, to the final three years of upper secondary school. The problem is that we, we don’t have similar people in one class, like we are [pause] we are different. You see in one class someone who can speak well and someone who doesn’t.

Everyone is not equally good; for example, in math I and a few others know more than those who have never studied math. So, they need to be in another group.

In all, these students express that Language introduction poses institutional obstacles by not offering individualised instruction and not fostering the writing, reading and speaking skills necessary for mainstream courses. As a consequence, immigrant students, who attend a mainstream programme, conclude that they do not possess the embodied cultural capital of language skills expected and valid in the regular courses.

Familiarity with national history, culture and the educational system

Another demand for embodied cultural capital in upper secondary school is for students to be familiar with national history and the societal system, for example, when they perform a careful analysis of Swedish society in social studies. Thaer compares writing essays in Language introduction with more analytical essays in mainstream subject courses:

Yes, we wrote essays in both Swedish and English, but not [pause] essays in social studies are not the same. You are supposed to do other things, making use of many concepts in your text, looking at it from different perspectives.

But history I’m not good at, because this is Swedish history about kings and such.

I try to manage my studies and to get my grades, but when I began last year on my programme I didn’t know [before I applied] that you need some kind of points to be accepted. But when I understood that, I tried to work and get points and grades in my courses.

Conclusions

Summarising the main findings, immigrant youths’ aspirations underscore the value of education for their future lives. They emphasise the importance of institutional capital, such as, qualifications for inclusion in working life and continuing education. However, our results suggest there are institutional obstacles in Language introduction and mainstream programmes. Most importantly, these immigrant students’ previously accumulated embodied cultural capital, namely, their cultural experiences and their existing knowledge, is not sufficiently recognised in subject matter instruction, which keeps their learning on an unqualified level; this supports Rutter’s findings (Citation2006) of school practices in England. Students’ criticism can be conceptualised as a reaction to a discontinuous past (Nilsson Folke Citation2017). Consistent with earlier findings (Sharif Citation2016; Skowronski Citation2013) students are not satisfied being held back by waiting for their Swedish skills to be approved for mainstream instruction, especially not students who envision a future outside Sweden, a global citizenship, in which Swedish is not embodied cultural capital of value. They protest being marginalised by the educational system, in a position outside mainstream education. In fact, the organisation of Language introduction outside mainstream education also excludes immigrant youths’ access to social capital in hindering direct communication with native speakers.

Furthermore, mainstream classes do not draw on the embodied cultural capital they do possess, implying disregard for the resources immigrant youth bring to the classroom, such as, experiences of other societal systems and national history outside Sweden and Europe.

In conclusion, there are processes of marginalisation wherein the educational system makes clear that these students do not possess a fully valid embodied cultural capital. A consequence for immigrant youth, if they lack an upper secondary diploma, will be their exclusion from many possibilities for continuing education and institutionalised cultural capital. These are processes of social reproduction that educational systems are often criticised for. Hence, their schooling impacts their chances of holding other positions in society, such as, employment, and thus accumulating economic capital (Bourdieu Citation1986). At stake are the educational careers of immigrant youth and their social inclusion in society at large.

In regard to future research, an area of exploration is the inner workings of upper secondary education as an institution by using neo-institutional theory, analysing why institutional obstacles, such as those suggested in this analysis, arise. There is also continued need for research on immigrant youths’ experiences of national school systems.

Didactic implications

To improve immigrant youths’ conditions for scholastic achievement and counteract inequalities in access to education, students need adequate pedagogical support, and teachers must make explicit their expectations on students (Nilsson and Axelsson Citation2013) and facilitate students’ familiarity with the majority language and culture (Hilt Citation2016). More importantly, this study and previous research (Cummins Citation2000; De Heer et al. Citation2015; Moskal Citation2014; Nilsson Folke Citation2017) point out the importance of allowing immigrant youth to find strength in and continue building on their existing embodied cultural capital.

However, current and previous findings (Atanasoska et al. Citation2018; Nilsson and Axelsson Citation2013; Nilsson Folke Citation2015; Skowronski Citation2013; Torpsten Citation2013) demonstrate that mastery of the majority language before entering mainstream programmes is prioritised over mobilising and acknowledging immigrant youths’ multicultural and multilingual backgrounds. This monolingual focus makes it urgent for us to emphasise the relevance of cooperation between students’ mother tongue education and formal instruction in mainstream courses, in order to help students bridge the gap between their past and present learning. Participating students, as well as research (Allen Citation2006; Axelsson Citation2015; Shaeffer Citation2019; Torpsten Citation2013), give strength to our conclusion that schools need to ensure an inclusive pedagogical practise, where immigrant students’ pre-existing embodied cultural capital is recognised and the majority language can be acquired in interaction with native speakers in mainstream classes.

Another way to recognise pre-existing embodied cultural capital would be to allow communication in English, between teacher and student, for immigrant youth attending mainstream courses, as an alternative during a transition period. All students and teachers have received some English education, and many immigrant youth might prefer it, as in this study. Students would then be introduced progressively to Swedish as the language for teaching content. Concurrently, many immigrants would gain increased access to mainstream courses developing their pre-existing embodied cultural capital.

Finally, immigrant youths’ upper secondary education is more than a matter of accumulating embodied cultural capital, learning Swedish for academic purposes, and becoming familiar with the national history, majority culture and the educational system. It is also an opportunity for the upper secondary educational system to acknowledge immigrant youths’ multicultural and multilingual backgrounds (Cummins Citation2000; Elmeroth Citation2014; Torpsten Citation2018; Turcatti Citation2018) and to give every student access to a transnational cultural and social capital in upper secondary classrooms.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Allen, D. 2006. “Who’s in and Who’s Out? Language and the Integration of New Immigrant Youth in Quebec.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 10 (2–3): 251–263. doi: 10.1080/13603110500256103

- Alvesson, M., and K. Sköldberg. 2017. Tolkning och reflektion: Vetenskapsfilosofi och kvalitativ metod [Interpretation and Reflection: Philosophy of Science and Qualitative Research Methods]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Atanasoska, T., M. Proyer, L. De Haene, E. Neumann, and G. Pataki. 2018. “On the Brink of Education: Experiences of Refugees Beyond the Age of Compulsory Education in Austria.” European Educational Research Journal 17 (2): 271–289. doi: 10.1177/1474904118760922

- Axelsson, M. 2015. “Nyanländas möte med skolans ämnen i ett språkdidaktiskt perspektiv [Newly Arrived Students Attending Mainstream Teaching, Focusing on Language Didactics].” In Nyanlända och lärande – mottagande och inkludering [Newly Arrived and Learning: Reception and Inclusion], edited by N. Bunar, 81–138. Stockholm: Natur & Kultur.

- Berggren, J. 2013. “Engelskundervisning i gymnasieskolan för mobilisering av ungdomars livschanser [English Teaching in Upper Secondary School Mobilising Young People’s Life Chances].” Dissertation, Linnaeus University Dissertations, Växjö.

- Bourdieu, P. 1974. “The School as a Conservative Force.” In Contemporary Research in the Sociology of Education, edited by J. Eggleston, 32–46. London: Methuen.

- Bourdieu, P. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” In Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by J. G. Richardson, 46–58. New York: Greenwood Press.

- Bourdieu, P., and M. de Saint Martin. 1982. “La sainte famille. L’episcopat francais dans le champ du pouvoir.” Actes Rech. Sci. Soc 44 (1): 2–53.

- Cummins, J. 2000. Language, Power and Pedagogy Bilingual Children in the Crossfire. Bilingual education and bilingualism; 23. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

- De Heer, N., C. Due, D. Riggs, and M. Augoustinos. 2015. “‘It Will Be Hard Because I Will Have to Learn Lots of English’: Experiences of Education for Children Newly Arrived in Australia.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 29 (3): 1–23.

- Denscombe, M. 2016. Forskningshandboken: För småskaliga forskningsprojekt inom samhällsvetenskaperna [The Good Research Guide: For Small-scale Social Research Projects]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Devine, D. 2009. “Mobilising Capitals? Migrant Children’s Negotiation of their Everyday Lives in School.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 30 (5): 521–535. doi: 10.1080/01425690903101023

- Elmeroth, E. 2014. “Interkulturell pedagogik [Intercultural Pedagogy].” In En bra början: mottagande och introduktion av nyanlända elever [A Good Start: Reception and Introduction of Immigrant Youth], edited by G. Kästen Ebeling and T. Otterup, 49–56. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- ESPON. 2015. “Territorial and Urban Aspects of Migration and Refugee Inflow.” ESPON Policy Brief 2015:11. file:///C:/Users/Acer/Downloads/Policy_brief_migration_FINAL_151215_1.pdf.

- Feinberg, R. C. 2000. “Newcomer Schools: Salvation or Segregated Oblivion for Immigrant Students?” Theory into Practice 39 (4): 220–227. doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip3904_5

- Hilt, L. T. 2016. “‘They Don’t Know What it Means to be a Student’: Inclusion and Exclusion in the Nexus Between ‘Global’ and ‘Local’.” Policy Futures in Education 14 (6): 666–686. doi: 10.1177/1478210316645015

- Hilt, L. 2017. “Education without a Shared Language: Dynamics of Inclusion and Exclusion in Norwegian Introductory Classes for Newly Arrived Minority Language Students.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 21 (6): 585–601. doi: 10.1080/13603116.2016.1223179

- Holstein, J., and J. Gubrium. 2011. “The Constructionist Analytics of Interpretive Practice.” In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research, edited by K. Denzin and Y. Lincoln, 341–358. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Jepson Wigg, U. 2016. “Betydelsefulla skeden – från introducerande till ordinarie undervisning [Crucial Phases – from Introduction to Mainstream Teaching].” In Skolans möte med nyanlända [School Approaches to Immigrant Youth], edited by P. Lahdenperä and E. Sundgren, 65–91. Malmö: Liber.

- Kalalahti, M., J. Varjo, and M. Jahnukainen. 2017. “Immigrant-origin Youth and the Indecisiveness of Choice for Upper Secondary Education in Finland.” Journal of Youth Studies 20 (9): 1242–1262. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2017.1321108

- Kvale, S., and S. Brinkmann. 2014. Den kvalitativa forskningsintervjun [An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing]. 3rd ed. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Migrationsverket [Swedish Migration board]. 2015. “Applications for Asylum Received, 2015.” https://www.migrationsverket.se/download/18.7c00d8e6143101d166d1aab/1485556214938/Inkomna%20ans%C3%B6kningar%20om%20asyl%202015%20-%20Applications%20for%20asylum%20received%202015.pdf.

- Moskal, M. 2014. “Polish Migrant Youth in Scottish Schools: Conflicted Identity and Family Capital.” Journal of Youth Studies 17 (2): 279–291. doi: 10.1080/13676261.2013.815705

- Nilsson, J., and M. Axelsson. 2013. “‘Welcome to Sweden’: Newly Arrived Students’ Experiences of Pedagogical and Social Provision in Introductory and Regular Classes.” International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education 6 (1): 137–164.

- Nilsson, Jenny, and Nihad Bunar. 2016. “Educational Responses to Newly Arrived Students in Sweden: Understanding the Structure and Influence of Post-Migration Ecology.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 60 (4): 399–416. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2015.1024160

- Nilsson Folke, J. 2015. “Från inkluderande exkludering till exkluderande inkludering - elevröster om övergång från förberedelseklass till ordinarie klasser [From Including Exclusion to Excluding Inclusion – Student Voices on Transitions from Introduction Class to Mainstream Teaching].” In Nyanlända och lärande – mottagande och inkludering [Newly Arrived and Learning: Reception and Inclusion], edited by N. Bunar, 37–80. Stockholm: Natur & Kultur.

- Nilsson Folke, J. 2017. “Lived Transitions: Experiences of Learning and Inclusion Among Newly Arrived Students.” Dissertation, Stockholm University, Stockholm.

- Rodríguez-Izquierdo, R., and M. Darmody. 2017. “Policy and Practice in Language Support for Newly Arrived Migrant Children in Ireland and Spain.” British Journal of Educational Studies 67 (1): 1–17.

- Rutter, J. 2006. Refugee Children in the UK. Maidenhead: McGraw-Hill Education.

- Shaeffer, S. 2019. “Inclusive Education: A Prerequisite for Equity and Social Justice.” Asia Pacific Education Review 20 (2): 181–192. doi: 10.1007/s12564-019-09598-w

- Sharif, H. 2016. “Ungdomars beskrivningar av mötet med introduktionsutbildningen för nyanlända. – Inte på riktigt, men jätteviktigt för oss [Young People and the Introductory Programme for Newly Arrived – Not for Real, but Important to Us] (pp. 65–91).” In Skolans möte med nyanlända [School Approaches to Immigrant Youth], edited by P. Lahdenperä and E. Sundgren, 92–110. Malmö: Liber.

- Sharif, H. 2017. “‘Här i Sverige måste man gå i skolan för att få respekt’: Nyanlända ungdomar i den svenska gymnasieskolans introduktionsutbildning [‘Here in Sweden You Have to Go to School to Get Respect’: Newly Arrived Students in the Swedish Upper Secondary Introductory Education].” Dissertation, Uppsala universitet, Uppsala.

- Skowronski, E. 2013. “Skola med fördröjning: nyanlända ungdomars sociala spelrum i ‘en skola för alla’ [School with a Delay: Newly Arrived Youths’ Social Play Area in ‘a School for All’].” Centrum för teologi och religions-vetenskap, Lunds universitet.

- Swedish National Agency for Education [Skolverket]. 2011. Läroplan för grundskolan, förskoleklassen och fritidshemmet 2011 [Curriculum for the Compulsory School, Preschool Class and the Recreation Centre, 2011]. Stockholm: Skolverket.

- Swedish National Agency for Education [Skolverket]. 2016a. Uppföljning av gymnasieskolan [Monitoring Upper Secondary School]. Stockholm: Skolverket.

- Swedish National Agency for Education [Skolverket]. 2016b. Språkintroduktion [Language Introduction]. Rapport 436. Stockholm: Skolverket.

- Taylor, S. 2008. “Schooling and the Settlement of Refugee Young People in Queensland: ‘ … The Challenges are Massive’.” Social Alternatives 27 (3): 58–65.

- Torpsten, A.-C. 2013. “Second-language Pupils Talk about School Life in Sweden: How Pupils Relate to Instruction in a Multilingual School.” Citizenship, Social and Economics Education 12 (1): 37–47. doi: 10.2304/csee.2013.12.1.37

- Torpsten, A. 2018. “Translanguaging in a Swedish Multilingual Classroom.” Multicultural Perspectives 20 (2): 104–110. doi: 10.1080/15210960.2018.1447100

- Turcatti, Domiziana. 2018. “The Educational Experiences of Moroccan Dutch Youth in the Netherlands: Place-Making Against a Backdrop of Racism, Discrimination and Inequality.” Intercultural Education 29 (4): 532–547. doi: 10.1080/14675986.2018.1483796

- Utbildningsdepartementet (SFS 2010:2039). Gymnasieförordning [Secondary School Regulation]. Stockholm: Regeringskansliet.

- Walton, J., N. Priest, and Y. Paradies. 2013. “Identifying and Developing Effective Approaches to Foster Intercultural Understanding in Schools.” Intercultural Education 24 (3): 181–194. doi: 10.1080/14675986.2013.793036