ABSTRACT

This article aims at deepening our understanding, through an ethnographical approach, of the processes at play in orientation choices within the field of vocational education; 21 working-class students nearing the end of compulsory schooling in French-speaking Switzerland were interviewed and their interactions with education professionals during guidance classes observed. Using data-source triangulation, the article shows that choices are often strongly shaped, within the highly selective and rigidly tracked Swiss educational system, by the systematic discourse of teachers during daily classroom interactions that instil a sense of limits in students over the course of the school year, thus consolidating the reproduction of social inequalities. Students’ choices also stem from pragmatically rational decisions, in which opportunity structures of the labour market, institutional influences, habitus, peer-group and the values of (fractions) of social classes each play a differentiated part in every individual situation. Finally, our ethnographic approach enables us to add complexity to recent studies based upon Bourdieu as well as upon Hodkinson and Sparkes’ theoretical models that tend to underestimate the structural influence of teachers’ discourse in shaping youngsters’ horizons for action.

Introduction

Although numerous educational reforms, as well as measures aimed at broadening entry criteria into post-compulsory education, have been implemented in Switzerland over the past decades (Falcon Citation2016), access to a range of upper secondary educational paths is still characterised by social inequalities. While students from upper classes are predominantly found in the academic tracks preparing them for university, vocational education remains ‘the likely destiny for children from the working classes’ (Lamamra and Moreau Citation2016, 9). This article seeks to explore this divide, in particular the determinants and the meanings given by youth from the working classes to the idealistic as well as the realistic educational choices they face within the realm of vocational education at upper secondary level, all of them being oriented towards pre-vocational tracks at the end of compulsory schooling.

The article uses theoretical approaches proposed by Bourdieu and Passeron (Citation1977), Bourdieu (Citation1986, Citation1990, Citation1993), by other researchers building upon the theory of habitus such as Hodkinson and Sparkes’ model of careership (Citation1997) as well as the work of more recent authors who have explicitly integrated this model into their analyses (Ball et al. Citation2002; Adshead and Jamieson Citation2008; Morrison Citation2009; Daoud and Puaca Citation2011; Hegna Citation2014; Rönnlund, Rosvall, and Johansson Citation2018). It is founded upon an ethnographical study conducted in a school in the city of Geneva. By focusing on observed interactions between teachers and youngsters in classrooms, the ethnographic approach enables us to integrate the key influence of teachers on young peoples’ choices.

State of research

Unequal class access to post-compulsory education has been at the heart of many sociological debates of the past decades; among them, the structuralist approach of Bourdieu (Citation1986, Citation1990) as well as Hodkinson and Sparkes’ model of careership, have attracted interest.

For Bourdieu and Passeron (Citation1977), school is not neutral: it embodies the ‘cultural arbitrary’: children of parents with higher cultural capital have much greater chances to succeed in school, since the culture of the school institution is similar to that of the dominant class. One of the fundamental effect of the educational system is the ‘manipulation of aspirations’; indeed, school awards qualifications and ‘confers aspirations’ (Bourdieu Citation1993, 97). Individuals are not consciously adjusting their aspirations to an exact evaluation of their chances of success (Bourdieu Citation1990); choices result from long-standing processes of internalisation of specific class conditions of existence. Through all the ‘judgments imposed by family or the educational system’ or ‘constantly arising from interactions of everyday life, the social order is progressively inscribed in people’s minds’. ‘Objective limits become a sense of limits, an anticipation of objective limits acquired by experience of objective limits, a sense of one’s place that leads one to exclude oneself from the goods from which one is excluded’ (Bourdieu Citation1986, 471).

Hodkinson and Sparkes (Citation1997) proposed a theory of career decision making based upon Bourdieu’s concepts of habitus and field. For them, educational policies are underpinned by assumptions of free will and Rational Action Theory (RAT). However, decisions made by youth are not taken in accordance with policy rhetoric; they are nevertheless rational, because they are based on personal or work experience, or on advice from friends and relatives. They are also pragmatic, based on ‘partial information located in the familiar’ rather than made on the basis of the full range of available information’ found in official documents, as expected by RAT. Decision-making cannot be ‘separated from the family background and culture of the pupils’ including ‘values for action that people grow into (33). Furthermore, people make career decisions within ‘horizons for action’ meaning ‘the arena within which actions can be taken and decisions made’ (34). Habitus, opportunity structures of the labour market and the educational system all influence horizons for action. Because schemata filter information, horizons for action are segmented; they both limit and enable youngsters’ view of the world and the choices they can make within it. Within their horizons, people make pragmatically rational decisions. The concept of field helps to understand choices within a segment of the educational system. Youth, employers, parents and teachers are all ‘players’ having different resources; other players often possess more capital than youngsters, such as employers who can hire and fire, and education providers who understand the system better. Decisions themselves are modified through such ongoing interactions within the field that, for Hodkinson and Sparkes, ‘helps to avoid determinism’(37–38) found in Bourdieu’s theory as well as in RAT’s vision of people being ‘completely free agents’.

This complex decision-making process has also been revisited in more recent research. Ball et al. (Citation2002) show, in their study of high-achieving students who want access to Higher Education (HE) in London, how their ‘horizons for action’ are social but also spatial and temporal, related to cost and tradition. Agents evaluate desired goals in relation to a framework of personal values. ‘Non-choice – with the strong influence of families – and aversion are also important here’ (69). Based upon qualitative life-history interviews with mature students registered at university, Adshead and Jamieson (Citation2008) show how, in early adulthood, non-decision and choice influencers’ did affect youth’ ‘restricted horizons for action’. Most of them ‘were constrained to see one pathway and never actively looked beyond it for alternatives’(150). Based upon questionnaires and interviews with 30 youngsters following either vocationally-oriented or academic programmes in Sweden, Daoud and Puaca (Citation2011) show a high degree of inconsistency between their wishes for an educational path; ‘a rational choice cannot be calculated because wishes are not articulated clearly enough’ in a hierarchical way (609). The interpretation of students’ wishes is based upon the concepts of pragmatic rationality, habitus and reflexivity. Memories, experiences and one’s own reflections define the students’ horizons of action. Based on a longitudinal study using quantitative data at three points in time (9th and 10th grade of compulsory schooling, and in the second year of post-compulsory programmes), Hegna (Citation2014) analyses changes in youth’ (decreased) educational aspirations for HE in Norway. Lack of information, in a country where career counsellors view their role as reinforcing individual motivation for personal development rather than informing students about the constraints of poor achievement, leads students to ‘rely on what they know (scant) and believe (habitus). Family and cultural values (…) give meaning to young students’ changing aspirations’ (607). After compulsory schooling, lowered aspirations result in changes in level of effort and achievement that might be interpreted, according to RAT, as a ‘consequence of rational experience-driven evaluations of their future possibilities’ ( 608).

While all these studies do validate Hodkinson and Sparkes’ (Citation1997) theory of careership, they neglect some important points that this contribution will highlight:

First, they underestimate the impact of teachers’ discourses in shaping youngsters’ choices. This might be partly due to the characteristics of national contexts, as in more universalistic educational regimes (United Kingdom or Scandinavian countries), teachers’ recommendations have less impact than in the highly segmented Swiss educational system. Yet, it is probably also related to the methodological design of these studies, that do not integrate ethnographic observation in classrooms, and therefore may not be able to identify themes (influence of teachers on students’ aspirations) that do not emerge from interviews alone (Lappalainen, Mietola, and Lahelma Citation2013). In these studies, the lowering of aspirations is analysed as being the result of individuals’ ‘decreased effort’ (Hegna Citation2014), as if ‘decision-making is taking place within institutions which are themselves culturally neutral in relation to their occupants’ (Hatcher Citation1998, 17).

Secondly, while teachers’ interactions in the school context are taken into account in Hodkinson and Sparkes’ (Citation1997) model, they are only seen as fortuitous; moreover, they are rarely documented in more recent studies (Ball et al. Citation2002; Daoud and Puaca Citation2011). When they are described in a more systematic way, teachers’ influence is seen as ‘positive’: by creating a supportive learning environment, they give working- class students a reason to want to remain at college in order to access HE (Morrison Citation2009); however, these influences are not described as being produced by the structure of the school system, leading the authors to see those interactions as ‘helping to avoid determinism’ (Hodkinson and Sparkes Citation1997, 37–38). In the Swiss education system, teachers’ influence may be much more systematic and, due to the placement in tracks, contribute to reproduction of inequalities.

Third, these studies tend to focus either on good students choosing academic educational paths (Ball et al. Citation2002; Adshead and Jamieson Citation2008) or on vocational education students, in the latter case with an emphasis on refusing to depict choices as being merely influenced by ‘external factors such as socialisation’ (Daoud and Puaca Citation2011, 618). As a result, these studies underemphasise the ways in which horizons for action can, for instance in the case of students aiming for apprenticeships, still stem from a persistent male counter-school culture that might be related to parental values (high value placed on empirical as opposed to theoretical knowledge: Palheta Citation2012) and working-class specific conditions of existence (persistent, although declining, fathers’ shop culture Delay Citation2018). Of course, anti-school attitudes should not be overemphasised, as in view of societal changes (declining industrial base, expansion of the service sector, democratisation of education) non-academically oriented working-class youngsters adopt much more instrumental perspectives towards education (MacDonald and Marsh Citation2004) than at the time of Willis’ (Citation1977) famous studies; in fact, these students, choosing vocational programmes, may now wish to acquire more theoretical knowledge, because they are aware of the changing image of traditional working-class jobs, and their attitude towards education wavers between hard work and soft resistance in classrooms (Niemi and Rosvall Citation2013).

Inequality in educational opportunities in Switzerland and in Geneva

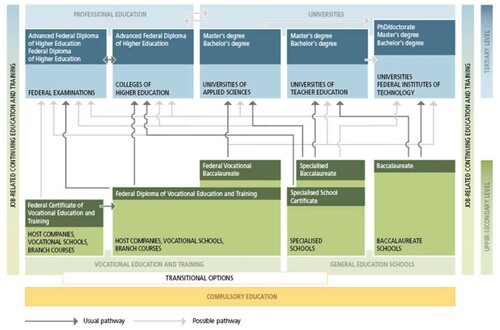

In Switzerland, post-compulsory secondary education is the backbone of the diploma system. At the end of compulsory school (11th grade: at second transition point), at age 15, pupils choose among a range of general education and vocational training. Company-based apprenticeship is the most frequently chosen option (60% in 2011 see Wolter Citation2018). Access to apprenticeships involves an application process, in which school grades and previous internships represent selection criteria for employers; successful candidates sign a contract, and are trained for the practical aspects of the work within the company (three to four days a week); they also follow theory classes at a vocational school (one to two days a week); they are paid a few hundred pounds a month. Successful apprentices receive a vocational diploma, after three or four years of training (see ). Vocational diploma holders are qualified as skilled workers for a specific trade; in most cases, they enter the job market directly after obtaining their qualification: indeed, vocational training does ensure good opportunities for integration into the job market in Switzerland (Falcon Citation2016).

Figure 1. The Swiss educational system. https://www.sbfi.admin.ch/sbfi/en/home/bildung/swiss-education-area/das-duale-system.htm.

For the minority of students opting for generalist studies, two avenues are open. Academic high school leads to the baccalaureate after a four-year curriculum and gives access to university (third transition point). Specialised high school (ECG), prepares students for occupations in the health and social field that necessitate general knowledge. After three years, the certificate gives access to some tertiary level educational institutions; a fourth year enables students to obtain a specialised baccalaureate, required to enter Universities of Applied Sciences.

Access to these various educational opportunities is regulated by the structure of compulsory secondary education. Indeed, Swiss school systems are strongly selective: at the end of primary schooling (first transition point), i.e. at age 12, pupils in the majority of cantons are placed, mostly with regard to their grades, in unequally academically prestigious tracked groups.Footnote1 A-tracks – offering extended requirements classes – are comprised of a regular number of students per classroom, whereas B-tracks, – or basic requirement classes – have smaller classes, enabling teachers to spend more time with each pupil. Pedagogy in B-track classes is adapted to the supposed level of students and thus tends to propose more modest challenges to students. Placements in tracked groups are extremely difficult to reverse (Meyer Citation2009). The best pupils, who most often come from privileged backgrounds, are grouped together in A-tracks that prepare for academic high school and university studies, while pupils whose results are poorer and who more frequently come from working-class and migrant backgrounds, are placed into B-tracks, leading to vocational training and, more rarely, to tertiary-level education. The early selection, as well as the strongly tracked system, result in particularly high levels of intergenerational reproduction (Falcon Citation2016).

In Geneva, access to upper secondary-level education depends, in most schools, on track placement in junior high school (compulsory secondary levelFootnote2), but also on successfully completing 11th gradeFootnote3 and on the last school year’s grade-point average. The range of available educational options is hierarchically structured since, under the cultural influence of its neighbour France, academically-oriented education is given a ‘much higher preference’ by pupils in the French-speaking part of Switzerland; in the German-speaking part, vocational education has a ‘more equal place, in public opinion, within the hierarchy of the educational system’ (Meyer Citation2009, 32). Geneva is the one canton where the majority of students choose generalist education (Wolter Citation2018). This is related to the relatively limited selectivity of lower secondary schools. Vocational training is actually also often offered in full-time school institutions; only one in four students integrates a company-based apprenticeship, Geneva having the lowest rate of companies providing this educational path in Switzerland. Geneva is an urban and university canton with the highest unemployment rate in Switzerland; it is characterised by a large service-based economy in which the labour market is competitive and focused on administration, health and education, all of which require more initial education. In Geneva, available educational options are:

Academic high school, leading to the academic baccalaureate, is viewed as the most highly valued option. 12% of the students after having failed their 12th year do reorient themselves towards full-time vocational training (SRED Citation2011). Among the students in B-tracks, only the ones with the highest grades are admitted into it.Footnote4 They may also access any of the other educational options.

Commercial high school, as a vocational full-time educational institution, prepares students for a diploma in three years. This option, as well as that of the specialised high school (ECG), are academically less demanding but can be complemented by an extra year of school, leading to a baccalaureate. Students from B-tracks must have completed their final year with good gradesFootnote5 to be admitted to these schools. Commercial high school represents a more highly valued option from the standpoint of students, as it provides opportunities for later ‘downward’ re-orientation to specialised high school or to apprenticeships (Rastoldo and Mouad Citation2017).

The company-based apprenticeship system does not solely function according to school achievement criteria. In theory, any student who has completed compulsory education, regardless of school results, is eligible to apply. In reality, many occupations organise an aptitude test for applicants. Although some trades require a higher level of scholarly achievement, apprenticeships remain less well-regarded, as the employment prospects they provide are not as favourable (Hupka-Brunner, Sacchi, and Stalder Citation2011).

Finally, integration programmes are provided for students who cannot directly pursue a qualification and who have to improve their skills for another year. Preparatory classes, for students who have passing grades can lead, if successfully completed, to entering commercial high school or specialised high school. The Professional Transition Centre is attended by students who failed their final year; it prepares them to apply for the type of company-based apprenticeships that have the lowest requirements in terms of academic ability.

The impact of tracks attended in lower-secondary level on upper-secondary level education can be demonstrated by :

Table 1. Access to upper-secondary level education.

In 2012, among all 11th grade students in Geneva, the majority of A-track students opt for academic high-school, whilst only a tiny minority of B-track students do so. Almost a quarter of the latter go into full-time, school-based vocational programmes, a bit more than one in five entering specialised high school, and less than one in ten chooses a company-based apprenticeship, this rate of direct transition being the lowest in the whole of Switzerland. Four out of ten are unable to go (directly) into training for a qualification seen as a prerequisite for successfully entering the job market. The very low rate of direct transitions from compulsory school to apprenticeship is the main reason why the authorities of canton Geneva decided to strongly promote vocational training in its lower secondary school reform (2011–2013): A new unified and more highly segmented system of three tracks has replaced the previous two tracks. Selectivity has been reinforced and measures have been introduced (2015–2018) to promote direct paths to vocational training, including creating apprenticeship positions as well as promoting vocational training in guidance classes during 11th grade: as reported in the programme, youth ‘should be made more aware of all vocational options, in particular in B-tracks’(p. 14) .Footnote6 Those measures were effective. From 2014 to 2016, the proportion of students in Geneva entering full time school-based vocational training slightly increased (Rastoldo and Mouad Citation2017).

Methods

This article is based upon an ethnographical study conducted in 2012 in a lower-secondary school in a working-class neighbourhood of Geneva where students are allocated to separate ‘homogeneous’ tracks.

The study of 11th graders in this school seeks to explore determinants and meanings assigned to being oriented towards vocational training. Through contacts with a teacher related to one of our work colleagues, I gained access to 3 classes comprised of a broad range of students in terms of academic achievement. During quite a prolonged presence in the ‘field’ (7 months), I spent 24 days in school, conducting participant observations of specific moments of school life during which choices are collectively constructed in the course of interactions in the classroom, for a total of 40 h of presence in the ‘field’, including: observation of interactions between teachers and the 60 pupils during guidance classes (N = 13 mostly in B-tracks), most of them during the second term – a time at which ‘ideal’ choices are concretely discussed with regard to grades, as well as in French class in order to get a feel of the atmosphere in B-track classrooms (N = 7); observation took place during all intermediate and final class councils (N = 10), where teachers make collective decisions about students’ specific demands for derogations to enter programmes to which their grades would not normally give them access. The aim of observation here was ‘the investigation of patterns of social interactions’ (Hammersley and Atkinson Citation1983) in school.

Guidance classes have the goal, from the beginning of the school year, of informing students of the various admission requirements for post-compulsory education, and of helping them formulate their future plans; the goal is to fill out a pre-registration form at the end of the second term.

I gathered various institutional documents: students’ school reports, guidance class materials (informational brochures about all educational opportunities available; advertisements for jobs that were distributed in class); placing my observations in the perspective of the political injunctions issued by Geneva canton’s executive government to ‘promote a positive view of apprenticeships’ also orients this study towards a policy ethnography approach, in which the goal is to ‘provide an analysis of how educational policy influences the everyday life of educational institutions’ (Lahelma et al. Citation2014, 53).

Having established an informal rapport through a twice-weekly presence in class, I asked for the participation of any students willing to be interviewed three months before making their final choices, i.e. at a time when their educational prospects are almost set. In order to reduce the asymmetry of positions between researcher and subject, I introduced myself to students in an antithetical position to that of teachers; I emphasised the fact that ‘I did not know’ and asked the youngsters to become my ‘teachers’ and help me understand what was going on. 25 pupils volunteered; they are ‘representative’ of students’ characteristics of the three main classes investigated in terms of gender, immigration and social class background. Individual, face-to-face biographical interviews took place in a classroom in which I attempted to create a convivial atmosphere by offering the students soft drinks and snacks. I tried to generate non-violent communication, promoting it through ‘active and methodical listening’ in the context of semi-structured interviews (Bourdieu Citation1996).

In order to see to what extent teachers did influence decision making processes, I carried out 7 comprehensive interviews with all head teachers and guidance class teachers of the 3 accessed classes, and the school’s orientation counsellor.

All 32 one-shot interviews were recorded and fully transcribed. Detailed notes were taken during classroom observations and less detailed notes were taken from memory after informal exchanges with teachers; 112 pages of notes were transcribed.

Ethnographical data analysis

Data analysis was conducted both during and after data collection. I used the five-stage critical ethnography approach (Carspecken Citation1996) in order to link micro- and macro-levels of analysis and to connect experiences with broader categories (social class, race, gender). Ethnographical observation in classrooms enabled me to identify themes that may not have emerged from interviews alone, such as that of the influence of teachers on students’ aspirations; this issue often goes unmentioned in interviews because youth grant it only ‘minor significance’, but I was able to integrate it: as Lappalainen et al. state (Citation2013, 197), ‘when asked about their choices, students mainly mentioned counselling only when explicitly asked’. Ethnographical work thus helped structure interviews and analyses. I analysed the discourse of teachers in guidance class as a system ‘which produces knowledge in certain gendered and class ways’ (191).

Interviews were coded by hand in order to identify core categories and integrating concepts. Four themes, using the same unit of analysis, i.e. student interviewees, were explored: (1) earlier school careers; (2) current relationship with school (subjects, teachers); (3) determinants and meaning of choices; (4) relationship with the future.

Analyses rely on Bourdieu’s (Citation1990) and Hodkinson and Sparkes’ (Citation1997) concepts: youth’ educational choices result from dispositions of habitus (towards education; specific tastes) that derive from multiple instances of socialisation (family, peers) and are located within social structures (class conditions of existence, but also gender and ethnicity). They also depend upon the opportunity structures of the labour market, as well as upon interactions with various ‘players’ in the education field (teachers, parents, employers).

Material presented below stems from joint analyses of distinct data-source which were triangulated in order to check inferences (Hammersley and Atkinson Citation1983): (1) selected excerpts from observation notes in which educational practices are described and choices discussed in B-track classrooms; (2) the 21 interviews conducted with working-class students from B-track classes, the majority of them came from migrant backgrounds. The three portraits selected below are those of students who belong to the majority group in our sample, experiencing ‘great academic difficulties’ (N = 19 cf. ).

Table 2. Number of students interviewed according to end-of-year grades required for admission to various upper-secondary educational programmes.

The first section of the article highlights the daily work carried out by teachers to ensure that ‘objective regularities’ (‘chances of access’ to a specific vocational education) coincide with ‘subjective expectations’ (Bourdieu and Passeron Citation1977). The next two sections present three sociological portraits; they are focused on students’ orientations within the types of vocational education seen as open to them, in order to understand whether, and to what extent, these were influenced by teachers’ discourses.

Results

Educating students for the prospect of a quick entry into the job market

Making sure likely outcomes are reinforced on a daily basis

In guidance classes for pre-academic A-track students, teachers explain that building up their curriculum vitae ‘is not the most important task for [them] right now’. They are familiarised with jobs as part of a rather distant future – at the end of their studies –, or informed about summer jobs to which they might apply. Teachers anticipate the type of jobs students might seek, pointing them towards socially valued occupations. The models of application letters students work on in class bear no relation to currently vacant jobs that would place them in a real-life situation. Pupils are not encouraged to look for practicums either, the idea being that they will have plenty of time later to think about such things.

In pre-vocational B-track guidance classes, the atmosphere is very different. The exercises carried out aim at reminding students that choices take place within a restricted field of opportunities, and teachers invite them to think of specific trades:

Teacher: ‘Are all doors open with regard to your choices?’

Female student (homemaker mother): ‘Well huh no, we’re in B-track’

Teacher: ‘Actual grades, that’s a factor that influences your choice of occupation.

Teachers come to class with real-life openings for company-based apprenticeships, in order to place students in concrete situations. During exercises in class, they contribute to reinforcing likely outcomes by promoting choices of gender-specific jobs (using for example the gender stereotype of hairdresser for a girl) and trades that are socially less valued. They also fail to discuss the ‘bridging’ programmes that are meant to enable students who successfully complete 11th grade, if they have not repeated school years before, to repeat their final year in A-track in order to have access to academic high school. The tracks do seem like ‘tunnels where young people must follow the road leading them through to the other side [to an expected post-compulsory continuation]’ and where emergency exits (that lead to another lower or higher track and then to another type of post-compulsory education) should only be taken on rare occasions’ (Gomensoro and Bolzman Citation2015, 93).

In the same way, other available options tend to go unmentioned; they concern opportunities to obtain higher qualifications (vocational baccalaureate, tertiary education) after some upper-secondary full-time vocational curricula that some of the students seek to enter through the ‘preparatory’ bridge option: in fact, teachers, underestimating their ability because of their foreign and disadvantaged backgrounds (Duru-Bellat Citation2002), anticipate that students will find apprenticeships along the way. One female teacher expressed her doubts about orienting a young woman student (factory-worker father, accounting assistant mother, Italian background), who was successfully completing her school year, towards the ECG preparatory track: ‘Yes. She has the grades for it, but will she make it there when she’s in a class with others students from the A-track next year? I don’t know. That’s what we worry about.’

Reorienting

B-track students are encouraged, in class, to look for practicums. Information transmitted by teachers has to do with looking for an apprenticeship. Teachers advise even the few ‘students with no academic difficulties’ from the B-track who wish to enter academic high school, to turn to company-based apprenticeships. Teachers then engage in a process of promoting the ‘conversion of professional aspirations’ (Zunigo Citation2008). Thus, Michel (clerical worker father), who is the best student in his class (he is one tenth of a grade point below requirements for academic high school), is putting a lot of effort into getting the grades needed for direct entry into this academic programme. Yet he is told: ‘There is an information meeting at the guidance office about finance jobs, that could be interesting for you.’ This type of remark likely played a role in his change of heart; a few months later he opted to go into commercial high school.

Other observations – providing examples of the ways in which 5 students ‘with no academic difficulties’ are discouraged from making the choice of academic high school by many teachers – confirm that ‘in every track, anyone who differs from the expected pathways tends to be reoriented towards it’ (Gomensoro and Bolzman Citation2015, 93). Thus, the prudent attitudes of working classes students about such choices cannot be merely analysed in terms of self-evaluations of students, with ‘lower self-esteem’ at play (Becker and Hecken Citation2009, 241). Rather, they should be viewed as gradual processes of adjustment of ‘subjective aspirations’ to ‘objective chances’ (Bourdieu Citation1990), influenced by the opinions expressed by teachers.

As we shall see, recurring comments by teachers during exercises in class represent as many socialising influences that either produce ‘transformed’ aspirations that contradict parental discourse, or reinforce the orientations already shaped by parental expectations.

Staying in full-time, school-based vocational programmes without aiming too high: youthful ambitions at the intersection of contradictory socialising influences

The following section presents the portraits of three youths making distinct educational choices within the field of vocational education. We explore their ‘horizons for action’: guided by their habitus and teachers’ discourse (see also ), they do not take into account the entire range of possible choices; based upon what is familiar to them, they make ‘pragmatically rational decisions’ (Hodkinson and Sparkes Citation1997).

Table 3. Young peoples’ ‘horizons for action’ shaping their educational choices.

The first two portraits illustrate youngsters’ majority choices (N = 16) to remain in full time education, while the third is an example of a minority choice (N = 9), i.e. that of youth wanting to leave full-time school.

The vocational baccalaureate as a measured ambition – trying to avoid discrimination in employment

Unsuccessfully completing her school year at the time of our interview, Lia (15, born in Switzerland, Somali background, parents married, museum guide father, homemaker mother) is one of the few students – only a handful of students are trying to get into academic high school – to display ambitious expectations: she sees herself, after three years of commercial high school, doing a fourth year to obtain a vocational baccalaureate.

Lia’s entire school career, in which she never had to repeat a year, has been characterised by high expectations, because her parents encouraged her to get into the A-track, though her grades at the end of primary school were not high enough. Her minimal school goodwill leads her to obtain from her parents the help of a private tutor to motivate her in her schoolwork. Like many immigrants who came to Switzerland, her parents expressed particularly high professional expectations for her (‘they wanted me to become a doctor’), especially as they hold rather high cultural capital – characteristic of students wishing to enter to commercial high school.Footnote7 However, Lia’s parents were not able to complete their tertiary-level education because the war in Somalia led them to seek asylum in Switzerland. These expectations are thus also linked to their frustration at having had to interrupt their own education, as well as to the socio-professional disqualification to which they have been subjected as immigrants: they had to start at the bottom of the occupational hierarchy in the Swiss job market, like other parents who wish that their children pursue full-time education. Lia’s mother uses her own example as a deterrent in order to motivate her daughter to continue her studies. As Lia states:

My mother was an office cleaner, she stopped because she had a bad back. She said: “Don’t do things the way I did, because cleaning is not a nice job. It’s better if you have a good job and a good salary.”

Table 4. Family and school characteristics of students by educational choice (company-based apprenticeship vs full-time post-compulsory schooling).

Lia is particularly anxious in guidance class, where students are invited to quickly pick an occupation: her educational choice is a good way to delay her entry into the work world. The fact that she does not mention academic high school as a goal is probably due to teachers, who openly discourage (even the best) students from this choice and often advise them (in 15 out of 17 cases, see ) to choose either specialised high school or apprenticeships. After her vocational baccalaureate, Lia does not envisage continuing her studies in a University of Applied Sciences, though the majority of students having obtained this qualification do enter such an institution (Rastoldo and Mouad Citation2017). Lia does not have a clearly articulated goal (Adshead and Jamieson Citation2008): ‘After the vocational baccalaureate, I’ll go to work in an office’. Like the vast majority of her schoolmates (19 of the 25 interviewed pupils: see ), she has adjusted her subjective expectations to her objective opportunities, having interiorised the institutional discourse that discourages B-track students from aiming for prolonged tertiary education. At the end of the school year, not having obtained passing grades but wanting to avoid going into the Professional Transition Centre, she puts in a request for repeating her final year and the school grants it.

A generalist education before entering the work world: a prudent disposition

Unlike Lia, Elena (16, born in Switzerland, Italian background, married parents, caretaker father, hairdresser mother) displays a prudent disposition typical of working-class families: she does not have strong views about the future, though her school year is going better than Lia’s, as she has narrowly obtained passing grades at the time of the interview. Elena is choosing to enter the preparatory track (for specialised high school) to which many young women are assigned.

Elena has also had a difficult school career from primary school onwards, though she has never repeated a year. Unlike Lia, she expresses no regrets about the three years she spent in B-track. In fact, she was nervous about entering junior high school and teachers advised her to enter the less demanding B-Track; her parents agreed and felt this was a prudent course of action, perhaps due to the fact they were rather less well-endowed in terms of cultural capital (her father briefly studied English after compulsory school; her mother followed an apprenticeshipFootnote8). Elena endorses this choice. Yet at no time did Elena seek to enter a company-based apprenticeship: indeed, her mother firmly rejects the idea that her daughter might enter the type of shorter vocational training she herself experienced in her youth in Switzerland and that she views as a dead end, as she explains:

My mom told me: “don’t go into an apprenticeship, because it’s hard.” She doesn’t want me to do hairdressing because she’s a hairdresser. You don’t make much money. She’d rather I went on to study’.

Elena’s choice of specialised high school (ECG) also stems from interactions with the guidance counsellor who, on the basis of various tests, brought out Elena’s ‘taste’ for the realm of social occupations (like 2 others of her schoolmates) ‘a safe choice that does not question the traditional gender division’ (Lappalainen, Mietola, and Lahelma Citation2013, 202): ‘she said commercial school is all about numbers. You’ll feel more at home at ECG’; this choice also reflects a disposition towards care work (‘I have a good feel for dealing with little kids’) that is part and parcel of gender-based socialisation. As is common in many working-class families, in which domestic tasks are unequally attributed to daughters and sons (Bates Citation1993), Elena (like two other girls in the sample see ) regularly took care of her little brother when her parents were working.

Despite parental wishes to see her practicing a prestigious profession – also mentioned by migrants parents in the UK as a way to protect children from the sorts of job that they themselves have been forced to endure (Francis and Archer Citation2005) – her ‘prudent’ career in the B-Track has, in her case, shaped ‘a sense of one’s place’ ‘guiding the occupants of a given place in social space towards the social positions adjusted to their properties’ (Bourdieu Citation1986, 466). Elena explains: ‘I told myself: “I couldn’t become a lawyer, it’s impossible.” You have to do a whole lot of studying.’ The Swiss track structure has the impact of strongly embedding school hierarchies in the students’ own sense of self: ‘I never imagined going to academic high school’ says Elena. Daily discourse by teachers reinforce the impact of the structure of the educational system; for Elena they produce – strong self-censorship; commercial school is not part of her ‘horizon for action’:

‘Our teacher, she’s also at commercial school. She compares us to them. Because her big 19 year-olds, they take notes (and we don’t). She said we were rowdy, that her class at the ‘comm’ school was so much better … And then somebody [from the class] answered: “go there then, don’t come here.”’

Leaving full-time school: counter-school culture and the appropriation of working-class heritage

A ‘taste’ for manual labour and a rejection of full-time study

Like many of his friends, Marc (16, Swiss, divorced parents, step-father unemployed car mechanic, mother on welfare), is failing his school year at the time of the interview; he is opting for a company-based apprenticeship, a male-gendered choice, as a car mechanic. In his case, this pragmatically rational decision stems from a class habitus produced by gendered working-class family socialisation.

Like Lia’s and Elena’s, Marc’s primary schooling has not been a smooth ride. However, unlike them, he narrowly makes it into the A-track in junior high school. At the same time, Marc’s interest in auto mechanics is growing, fostered by his stepfather who holds a vocational diploma in this field and initiates him to the trade in the garage where he is working, gradually taking on the role of an ‘apprenticeship supervisor’:

The bit that really got me into this project, my stepfather was getting me to help at the garage and in the beginning it took time for me to understand everything, and then, after I understood, I loved it and I kept going.

I never did any homework … So I never got to go to art class because I always had to catch up on homework. […] There is a way they talk that I don’t like. If teachers scream “sit down!”, I tell them to sit, they really don’t like that. […] I don’t go to detention and I do whatever I like. Last year, I broke the school record for detention hours. [Laughs]

Marc: ‘– My mother said I can do what I want as long as I have a job that brings in money. Some parents really like to control their children’s future. She isn’t like that at all.

– And your stepfather?

– He is proud, he says being a mechanic is a good trade.’

The choice of apprenticeship, for Marc like for most of the other interviewed students, is valued because it resonates with a family heritage that is transmitted to them (as in 6 out of 9 cases, see ) in the form of dispositions – practical culture, resistance to theory, value placed on short training programmes – that they themselves adopt. For them, teachers’ actions to prepare students for vocational integration merely ‘reinforces their aspirations’ (Zunigo Citation2008) to enter an apprenticeship.

Unlike Lia, Marc has developed a negative rapport to academic subjects: ‘History I don’t like. Talking about dead people, that won’t be of any use to us. So I go to sleep’. Aware that the B-track does not open all educational doors, Marc rules out the possibility of generalist full-time studies: ‘School, I’ve been there for too long. I need a job. I won’t go back to studying’.

Yet, he is not totally averse to school. Indeed, some students from the working classes describe a process of instrumental accommodation in the later years of compulsory schooling, following earlier disengagement (MacDonald and Marsh Citation2004); Marc is occasionally ambivalent during the interview: he is conscious that, today more than ever, school results do count in securing access to the type of work he wants in a Swiss apprenticeship market characterised by fast technological change, increased competition and a dearth of apprenticeship places (Meyer Citation2009):

I am lucky to have repeated the year, it gave me an extra year to understand how important school is. If I don’t do any work during the 3rd period I can forget finding an apprenticeship.

Conclusion

To conclude, we will highlight two main points:

First, our ethnographic study, by focusing on ‘the everyday interaction between the pupil and the institution’ (Hatcher Citation1998, 21), shows that students allocated to B-tracks in a context of policy reforms aimed at promoting apprenticeships, are most likely to be discouraged or provided with misleading or partial information by teachers when they express a wish to attempt entering academic high school. The prudent stances that lead to choosing vocational education result, in part, from the systematic discourse of teaching staff who contribute, day after day, to the consolidation of the reproduction of social inequalities by shaping students ‘horizons of action’ and by getting them to adjust their subjective aspirations to their objective chances, thus reinforcing their ‘sense of limits’ (Bourdieu Citation1986).Footnote12 This finding is of particular interest because researchers building upon Bourdieu’s theory have tended to underestimate teachers’ influences, mentioning them in passing and without illustrations (Ball et al. Citation2002; Daoud and Puaca Citation2011; Hegna Citation2014), considering them as fortuitous (Hodkinson and Sparkes Citation1997) or viewing them as positive interactions that can help to avoid social determinism (Morrison Citation2009).

Second, our study suggests that differentiated choices within the field of vocational education also appear to result from values associated with distinct fractions of the working classes. Thus, whilst parents of students opting for full-time vocational schooling, who are often first-generation immigrants and find themselves at the bottom of the Swiss social structure, place a high value on generalist diplomas, parents of youth opting for apprenticeships – more often skilled workers, ‘native-born’ or with migrant background but born in Switzerland – are more sceptical about the value of such diplomas (see also Palheta Citation2012) and place a higher value on the acquisition of empirical knowledge they experienced during their own apprenticeship. Working-class students tending to turn away from upper secondary academic education can therefore still be understood in terms of a youthful and predominantly male, persistent working-class counter-school culture, though it may have become more ambivalent and soft (Niemi and Rosvall Citation2013) since the days of Willis’ study (Citation1977); it includes traits not only of a father-focused ‘workshop culture’ that continues, although it has declined, to foster a wish to challenge the school’s authority, but also of cultural elements (manual dispositions) transmitted by families (Delay Citation2018); these factors also explain some girls’ dispositions to care work and their choices to remain in full-time school programmes. These results, in contrast with Daoud and Puaca’s (Citation2011, 619) perspective that downplays explaining all choices ‘by external factors such as socialisation’, give further evidence of a decision making process that cannot be separated from ‘family background, values and norms for action that people grow into’ (Hodkinson and Sparkes Citation1997, 33).

Our study does have its limits: it focuses on youth from working classes who have been oriented to the ‘minority’ B-track. It might also have been of interest to place a specific focus on the minority of those students who were oriented towards tracks leading to academic high school. Such an analysis might have allowed us to put into perspective the relative influences of habitus in these choices, the latter being a concept, as Hatcher noted (Citation1998, 21) that ‘addresses not the exceptional but the routine’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In a few cantons however, students are not assigned to distinct tracks. Classrooms are heterogeneous with a mix of high and low ability students.

2 Since the lower secondary school reform in Geneva (2011–2013), heterogeneous classrooms have been discontinued.

3 In order to be admitted, students must have an overall grade-point average of at least 4,0 out of 6.

4 For details, see .

5 For details, see .

6 See Plan d’action du Conseil d’Etat (2015–2018). Soutenir et valoriser l’apprentissage dans le canton de Genève, Genève : DIP.

7 Fathers, holding tertiary education diplomas, hold middle-class jobs (two couples out of three).

8 No parent of students intending to enter the ECG belongs to the middle classes; all are unskilled industrial workers or employees. Their level of qualification (vocational diploma, commercial school diploma) is lower.

9 While it is rare among students aspiring to full-time education, it is almost universal in those choosing apprenticeships (see ).

10 The parents of students choosing apprenticeships are most often skilled workers, unemployed or divorced; Their own educational careers are shorter (compulsory school, apprenticeship) than those of the parents of youth choosing the ECG (or other full-time schools), who are more stable (employed, married), are better trained but more frequently working in unskilled jobs. See .

11 In our sample, 8 out of 25 students exhibit a strong counter-school culture that can be related to low parental aspirations for their children (see ).

12 A majority (10 out of 17) of the pupils who explicitly reported a teachers’ influence (most of the time concerning less valued educational options) on their choice, considered it when making their decisions (see ).

References

- Adshead, L., and A. Jamieson. 2008. “Educational Decision-Making: Rationality and the Impact of Time.” Studies in the Education of Adults 40 (2): 143–159.

- Rastoldo, F., and R. Mouad. 2017. L’enseignement à Genève. Repères et indicateurs statistiques [Education in Geneva: Guides and Statistical Indicators]. Genève: DIP.

- Ball, S., J. Davies, M. David, and D. Reay. 2002. “Classification and Judgement: Social Class and the Cognitive Structures of Choice of Higher Education.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 23 (1): 51–72.

- Bates, I. 1993. “‘A Job Which is Right for Me?’ Social Class, Gender and Individualisation.” In Youth and Inequality, edited by I. Bates and G. Riseborough, 14–31. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Becker, R., and A. Hecken. 2009. “Why are Working-Class Children Diverted from Universities? An Empirical Assessment of the Diversion Thesis.” European Sociological Review 25 (2): 233–250.

- Bolzman, C., R. Fibbi, and M. Vial. 2003. Secondas, secondos : le processus d’intégration des jeunes adultes issus de la migration espagnole et italienne en Suisse [Second Generation Immigrants Integration Processes of Young Adults in Switzerland with Family Backgrounds from Spain and Italy]. Zurich: Seismo.

- Bourdieu, P. 1986. Distinction. London: Routledge.

- Bourdieu, P. 1990. The Logic of Practice. California: Stanford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1993. Sociology in Question. London: Sage publications.

- Bourdieu, P. 1996. “Understanding.” 132: 17–37.

- Bourdieu, P., and J.-C. Passeron. 1977. Reproduction: in Education, Society and Culture. London: Sage.

- Carspecken, P. 1996. Critical Ethnography in Educational Research. New-York: Routledge.

- Daoud, A., and G. Puaca. 2011. “An Organic View of Students’ Want Formation: Pragmatic Rationality, Habitus and Reflexivity.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 32 (4): 603–622.

- Delay, C. 2018. “En sortir ou s’en sortir par l’école. Choix d’orientations juvéniles, classes populaires et enseignement professionnel en Suisse Romande.” [“Getting Out or Getting on, the Role of School. Youth’s Educational Choices, Working Classes and Vocational Education in Switzerland”]. Sociétés Contemporaines 109: 117–147.

- Duru-Bellat, M. 2002. Les inégalités sociales à l’école [Social Inequalities in School]. Paris: PUF.

- Falcon, J. 2016. “Les limites du culte de la formation professionnelle : comment le système éducatif suisse reproduit les inégalités sociales.” [The Limits of the Cult of Vocational Training: How the Swiss Educational System Reproduces Social Inequality]. Formation Emploi 133: 35–53.

- Fibbi, R. 2006. “Discrimination dans l’accès à l’emploi des jeunes d’origine immigrée en Suisse.” [“Discrimination in Access to Employment for Youth from Immigrant Backgrounds in Switzerland”]. Formation Emploi 94: 45–58.

- Francis, B., and L. Archer. 2005. “British-Chinese Pupils’ and Parents’ Constructions of the Value of Education.” British Educational Research Journal 31 (1): 89–108.

- Gomensoro, A., and C. Bolzman. 2015. “The Effect of Socioeconomic Status of Ethnic Groups on Educational Inequalities in Switzerland: Which Hidden Mechanisms?” Italian Journal of Sociology of Education 7 (2): 70–98.

- Hammersley, M., and P. Atkinson. 1983. Ethnography. Principles in Practice. London: Tavistock.

- Hatcher, R. 1998. “Class Differentiation in Education: Rational Choices?” British Journal of Sociology of Education 19 (1): 5–24.

- Hegna, K. 2014. “Changing Educational Aspirations in the Choice of and Transition to Post-Compulsory Schooling – a Three-Wave Longitudinal Study of Oslo Youth.” Journal of Youth Studies 17 (5): 592–613.

- Hodkinson, P., and A. Sparkes. 1997. “Careership: A Sociological Theory of Career Decision Making.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 18 (1): 29–44.

- Hupka-Brunner, S., S. Sacchi, and B. Stalder. 2011. “Social Origin and Access to Upper Secondary Education in Switzerland: a Comparison of Company-Based Apprenticeship and Exclusively School-Based Programmes.” In Youth Transitions in Switzerland, edited by M. Bergman et al., 157–182. Zurich: Seismo.

- Lahelma, E., S. Lappalainen, R. Mietola, and T. Palmu. 2014. “Discussions That Tickle our Brains: Constructing Interpretations Through Multiple Ethnographic Data-Sets.” Ethnography and Education 9 (1): 51–65.

- Lamamra, N., and G. Moreau. 2016. “Les faux semblants de l’apprentissage en Suisse.” [“The Illusions of the Apprenticeship System in Switzerland”]. Formation Emploi 133: 7–16.

- Lappalainen, S., R. Mietola, and E. Lahelma. 2013. “Gendered Divisions on Classed Routes to Vocational Education.” Gender and Education 25 (2): 189–205.

- MacDonald, R., and J. Marsh. 2004. “Missing School: Educational Engagement, Youth Transitions and Social Exclusion.” Youth & Society 36 (2): 143–162.

- Meyer, T. 2009. “Can Vocationalisation of Education go Too far? The Case of Switzerland.” European Journal of Vocational Training 46 (1): 28–40.

- Morrison, A. 2009. “Too Comfortable? Young People, Social Capital Development and the FHE Institutional Habitus.” Journal of Vocational Eduation and Training 61 (3): 217–230.

- Niemi, A.-M., and P.-A. Rosvall. 2013. “Framing and Classifying the Theoretical and Practical Divide: How Young Men’s Positions in Vocational Education are Produced and Reproduced.” Journal of Vocational Education and Training 65 (4): 445–460.

- Palheta, U. 2012. La domination scolaire [School Domination]. Paris: PUF.

- Rastoldo, F., A. Evrard, and J. Amos. 2007. Les jeunes en formation professionnelle [Youth in Vocational Training]. Genève: SRED.

- Rönnlund, M., P.-A. Rosvall, and M. Johansson. 2018. “Vocational or Academic Track? Study and Career Plans among Swedish Students Living in Rural Areas.” Journal of Youth Studies 21 (3): 360–375.

- SRED. 2011, 2009. Indicateurs clés du système genevois de formation [Key Indicators of the Geneva System of Education]. Genève: DIP.

- Willis, P. 1977. Learning to Labour: How Working Class Kids Get Working Class Jobs. Farnborough: Saxon House.

- Wolter, S. 2018, 2014. Swiss Education Report. Aarau: Swiss coordination centre for Research in Education.

- Zunigo, X. 2008. “L’apprentissage des possibles professionnels.” [“Learning What is Possible as a Future Occupation”]. Sociétés Contemporaines 70 (2): 115–131.