ABSTRACT

International mobility has become a significant part of the life experiences of a growing number of Polish youths since the enlargement of the EU in 2004, influencing young people’s transitions from education to work or transitions across different labour markets. The key aim of this paper is to explore socio-occupational sequences of young people considering spatial and temporal dynamism of the process of mobility. Focusing on the intersection between youth and migration studies, we aim to answer the following research questions: (1) What are the socio-occupational sequences of young people ‘on the move’? (2) How mobility capacities and imperatives determine the flow of sequences and (3) How mobility patterns collocate with sequences’ shapes? Based on Social Sequence Analysis, we have distinguished four types of ‘mobile sequences’ of young adults: (1) the ‘upward sequence’ when spatial mobility accelerates social mobility; (2) the ‘yo-yo sequence’, where transnational mobility causes ‘return social mobility’; (3) the ‘zigzag sequence’, involving up-and-down patterns in social mobility; (4) the ‘flat sequence’, where spatial mobility has no impact on the objective dimension of socio-occupational sequences, but mobility strongly influences human capital.

Introduction

The enlargements of the European Union (EU) of 2004 and 2007 caused an acceleration in the mobility of young adults below age 35 from Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), the so-called ‘generation on the move’ (Szewczyk Citation2015; Robertson, Harris, and Baldassar Citation2017; Grabowska and Jastrzebowska Citation2019; Lulle, Janta, and Emilsson Citation2019) or ‘mobile generation of choice’ (Pustulka, Winogrodzka, and Buler Citation2019). Eurostat data for intra-EU mobility confirmed that in 2017, most CEE nationals leaving the country were below 35 years of age (Fries-Tersch et al. Citation2020). It means that geographical mobility has taken up a special position in the life pathways of young adults from CEE. Still, structural and individual, agentic factors remain key in young people’s mobility opportunities (Glick Schiller and Salazar Citation2013; Robertson, Harris, and Baldassar Citation2017; Cairns Citation2018).

In this article, we use the conceptual framework of mobile transitions defined as ‘transition pathways under the condition of mobility’ where one should take into account three intersecting ‘domains’ of life: economic opportunities, social relations and civic practices (Robertson, Harris, and Baldassar Citation2017). In this article we particularly focus on economic opportunities and capital accumulation, through the prism of which mobile transitions are understood not as a straightforward passage from education and dependency to work and autonomy but are much more complicated (cf. Punch Citation2015). We adopt the perspective of international migration and its various patterns as a context to observe a number of occupational sequences of young Polish adults embedded in the emerging interdisciplinary area of ‘youth mobility studies’ (Cairns Citation2018; King Citation2018). Scholars have argued that youth transitions are undergoing de-sequentialization and subject to increasing contingencies (Leccardi and Ruspini Citation2006). Robertson, Harris, and Baldassar (Citation2017) claim that traditional linear transition models have been rightly critiqued for flat sequential passaging into adulthood as a final point and ‘successful’ transitions from education to employment. The traditional and institutional indicators of transitions are no longer appropriate, as they do not capture the ongoing movements of young people in the course of their lives. Today, young people renegotiate their statuses in the context of education and the labour market while being mobile (Brannen and Nilsen Citation2002), which transforms the traditional transition pathways (Robertson, Harris, and Baldassar Citation2017).

The key aim of this article is to combine mobility with social sequences and transitions, because they determine the ‘contingent life course’ (Heinz Citation2003) of contemporary young adults. We define social sequences as flows of socio-occupational events and phenomena that may be ordered or disordered and hindered in space and time as well as hierarchically. By transition we mean the process or a period of change from one state or condition to another in light of an in-depth understanding of its contexts and opportunity structures. Therefore, we would like to explore the flow of social sequences of young adult movers in both objective terms – how they are (dis)ordered, and in subjective means – how they are narrated.

Conceptual and methodological frames

Methodologically, a mobile transitions framework calls for comparative analysis that looks at divaricated types of youth mobility within the same study (Robertson, Harris, and Baldassar Citation2017). Therefore, we used a qualitative adaptation of Social Sequence Analysis (cf. Cornwell Citation2015) enriched with subjective narratives of young people with divergent mobility experiences.

Social Sequence Analysis (SSA, Cornwell Citation2015) is a method applied in life-course research to study continuities and changes in individual pathways over time. In social sciences, this approach is most often used to analyse educational and occupational trajectories (e.g. Brzinsky-Fay and Solga Citation2016), but other dimensions such as mobility have been rarely applied as an integral part of this research. In this article we decided to use SSA as this approach is best suited to the analysis of (dis)ordered life paths and to observe not only spatial but also social mobility. We take up the aims and structure of SSA where we reconstruct every single job that the interviewees had at the time when they were interviewed at different points: before migration, during migration and after migration along with the narratives of young migrants regarding how they experienced these events. Using this method enabled us to isolate the work events, including geographical mobility, in their life pathways along with their experiences.

As noted by Robertson, Harris, and Baldassar Citation2017 (7) ‘transition pathways may be transformed by mobility – resisted, disrupted or redirected through delays, accelerations or protractions’. We decided to explore what factors make the transitions for some people faster, and for others, delaying transitions from education to employment. For this purpose, we used a conceptual approach of mobility capacities and imperatives (Cairns Citation2018). This framework includes an interplay of two heuristic dimensions of qualities and factors. Mobility capacities are positive attributes associated with one’s personal situation: internationally transferable skills and credentials, foreign language fluency, financial and emotional support, presence of family and peers abroad, practical knowledge about other societies, societal validation of mobility life planning strategies or ability to practice ‘spatial reflexivity’ defined as a ‘recognition of the importance of geographical movement and acting upon this realization’ (Cairns Citation2014, 28). Mobility imperatives are negative aspects of one’s present place of residence. This concept takes into account a range of social factors which shape labour market position and welfare conditions. Examples are: constraining local opportunities, devaluation of educational credentials at home, better-paid work or security of a stable job abroad, loose family ties, low levels of social mobility at home or local cultural insularity (Cairns Citation2018). Mobility capacities (individual traits, networks and resources) and mobility imperatives (external, societal conditions and pressures) integrate a spectrum of subjective considerations and objective conditions, which are crucial for mobility decision-making in the youth phase of the life course. The approach of mobility capacities and imperatives helps to explain how young adults’ choices are mediated by structural and personal circumstances. Cairns (Citation2018) presented typology with four mobility scenarios based on combination these two variables. In only one of these scenarios is it anticipated high probability of mobility (combination of high mobility capacity with high mobility imperative). However, we don't use this typology per se. We focused on its components, assuming that mobility also occurs in other scenarios, although to a lesser extent. Thanks to such a procedure we can use this concept to study youth’s proceeding career paths abroad.

Mobility can mean different things for people with different levels of mobility capacities and imperatives. Migration can speed up youth transitions, opening new opportunities, or fragment their transitions. A person’s social background and economic/social capital can determine how young people experience mobility (cf. Sarnowska Citation2019; Grabowska Citation2020). Young adults faced with multiple mobility imperatives can be more likely to feel lost in the foreign labour markets, finding themselves forced to take low-skilled jobs (cf. Anderson Citation2000) and build their careers from the ground up (Parutis Citation2011; Moroşanu et al. Citation2019; Winogrodzka and Sarnowska Citation2019). They can struggle with temporary, flexible and underpaid forms of precarious employment (Trevena Citation2013; Winogrodzka and Mleczko Citation2019). People with a high level of mobility capacities can take advantage of going abroad, not only to value their economic but also social or cultural capitals (Grabowska and Jastrzebowska Citation2019).

Another important issue that can influence the shape of socio-occupational sequences is the pattern of geographical mobility. It includes various behaviours, actions, strategies and use of resources by migrants both conscious and unconscious, both purposeful and not. Engbersen et al. (Citation2013) offer a typology of migratory patterns where the main axis of differentiation is situated along attachments to sending and receiving countries which order clustering of main variables such as: duration of stay, form of employment or home visits. It brought scholars to distinguish some model-typical migratory patterns of: (1) circular migrants with weak attachments to the country of destination; (2) settlers with weak attachments to the home country; (3) bi-nationals with strong attachments to both the destination and the home country and (4) footloose migrants with weak attachments to both the home and the destination country. In this article we take a look at this typology to have an insight into the strategies of young migrants and to answer the question how mobility patterns collocate with socio-occupational sequences and transitions of young people.

Focusing on the intersection between youth and migration studies (Robertson, Harris, and Baldassar Citation2017; Cairns Citation2018; King Citation2018), we aim to answer the following research questions: (1) What are the socio-occupational sequences of young people ‘on the move’? (2) How mobility capacities and imperatives determine the flow of occupational sequences and (3) How mobility patterns collocate with sequences’ shapes?

Context and data

Poland was the largest CEE country to join the EU in May 2004. According to the Central Statistical Office of Poland, more than 2.5 million people left Poland for more than three months (CSO Citation2017) between 2004 and 2015. One in three Polish nationals who migrated after May 2004 had a higher level of education. The period following Poland’s accession in 2004 was characterised by outflows of young Polish movers (with an average age below 30) (Kindler Citation2018). In 2007, nearly 70 per cent of the post-accession stream of migrants from Poland was young, below 35 years of age: 27 per cent in the age cohort of 20-24; 26 per cent in the 25–29 cohort; and 13 per cent in the 30–34 cohort (cf. Grabowska-Lusińska and Okólski Citation2009). The outflows were also accompanied by return mobility, which was dominated by 20- to 29-year-olds in 2009 (60%); however, the age of returnees has increased since then. In 2017, the segment of 20- to 29-year-olds dropped to 10%, while the segment of 30- to 39-year-old returnees increased to 30% (Fries-Tersch et al. Citation2020).

This article draws on empirical material collected for the research project Education-to–domestic and- foreign labour market transitions of youth: The role of locality, peer group and new media based on the Qualitative Longitudinal Study methods (Neale Citation2019). Within this project together with our colleagues between 2016 and 2020 we collected an extensive qualitative dataset that gave us an opportunity to observe life-courses and behaviours of both internationally mobile and non-mobile young adults. We conducted the multi-sited study in three medium-sized Polish towns. Our target age group in the project was focused on young adults between 19 and 34. In the first wave (n IDI = 111), we reconstructed their educational and labour market sequences, with a special focus on education-to-work transitions. In the second (n IDI = 56) and the third wave (n IDI = 44), we focused their narratives on their understanding of work stability, transfer of skills between various domains of life and also whether they saw themselves as adults and how they personally defined what it means to be an adult. With every wave, we updated their educational and labour market sequences, which subsequently was informed by an SSA structure. All ethical best practices with regard to data handling, internal confidentiality and preservation of anonymity were observed throughout every stage of the project (see Neale Citation2019). All interviews were conducted in Polish, then transcribed, then entered and coded in Atlas.ti software.

While selecting the data for this analysis we narrow down our analysis to 20 personalised sequences and their narratives, constituting a total of 60 in-depth interviews conducted longitudinally in three waves over the course of 42 months. We focused on university-educated migrants who were abroad at least three months and who took part in all waves of the project – which was the most important reason for our selection of sequences. We took on board only these cases, in which we were able to reconstruct the whole sequence (situation before, during and also after migration experience).

Findings: a typology of mobile sequence

The objective Social Sequence Analysis (Cornwell Citation2015) along with subjective narratives led us to reconstruct four typical shapes of mobile sequences: (1) the upward sequence; (2) the yo-yo sequence; (3) the zigzag sequence; and (4) the flat sequence.

In the following sections each shape is presented as a reconstruction of a sequence of socio-occupational categories, marked by a country where it was performed, supported by an interpretation and a narrated experience. Each sequence has been reconstructed based on The International Standard Classification of Occupations (ISCO-08) which is the tool organising jobs into a clearly defined groups according to the tasks and duties undertaken in the job as follows: 1: Managers, 2: Professionals, 3: Technician and associate professionals, 4: Clerical support workers, 5: Service and sales workers, 6: Skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers, 7: Craft and related trades workers, 8: Plant and machine operators, and assemblers, 9: Elementary occupations, 10: Armed forces occupations.

We are well aware that shaping social sequences of young adults is a dynamic process depending on both personal experience and structural conditions. However, we believe that these four representations presented below are ideal shapes and therefore types of social sequences reflecting different ways in which mobility experiences can impact on the socio-occupational paths of young people.

Type 1. Upward sequence

The upward sequence is an example of an ordered, linear sequence with fluent transitions from education to the labour market. In this case, spatial mobility accelerated social mobility. Representatives of this type had also earlier continuous, institutionally predictable transitions from education to employment. They did not fail to complete university programmes and did not hop between temporary jobs and unemployment spells. When they graduated from university, they had a fairly clear idea of what they wanted to do in the future, and where.

M: male, F: female, 1: Managers, 2: Professionals, 3: Technician and associate professionals, 4: Clerical support workers, 5: Service and sales workers, 6: Skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers, 7: Craft and related trades workers, 8: Plant and machine operators, and assemblers, 9: Elementary occupations, 10: Armed forces occupations, V: voluntary service, EG: Egypt, ES: Spain, DE: Germany, FR: France, HN: Honduras, PL: Poland, UK: United Kingdom.The upward sequence characterises persons with high mobile capacities and low mobile imperatives (Cairns Citation2018). Therefore, looking at representations of this sequence, we mainly observe mobility by choice including both ‘diploma’ and ‘post-diploma’ international movements (Cairns Citation2014) with non-economic motivations for mobility.

I left the day after the final exams, so I didn’t have this experience of, ‘God, it’s so hard in Poland, you can't find a job, you have to look for a better life.’ I just went to college [abroad], and then I liked it so much [that] I settled (Daria, Wave 1).

I wanted to speak as many languages as possible. I wanted to focus on languages because this was - for me - a stepping stone for leaping out into the world. Language education - learning English, French, Spanish - completely dominated my degree choices and then contributed - or perhaps could have been the main factor - of my going abroad, migrating [currently learning Portuguese as well] (Kamil, Wave 2).

[My parents] had no problem [with migration]. (…) They supported me in this and really always helped. When my financial situation got difficult, I could always count on them (Marek, Wave 1); I had a very nice French language mentor who motivated us from the first year about [Erasmus] being the best experience we can have. She believed in us and she said that I would manage (Natalia, Wave 2).

Everyone’s jaws just dropped when I managed to get [this offer]. They were all so happy (…) because this was the best thing, best contract, that you could get as a young person who wants to go abroad and get international experience (Kamil, Wave 2).

We live in a very globalised world today. Social media (…), everything shows us that some people go abroad and try something. (…) I don’t want to say that they achieve something but they are experiencing something (…), so I think that Poles (from) my generation (…) think ‘I don’t want to be worse, I also want to have such an experience. Why can’t I live in Paris for a while and eat breakfast overlooking the Eiffel Tower every morning? Why not?’ (Kamil, Wave 1)

I would like to live in Berlin because I feel good there. And this is basically by choice. I came here because I wanted to live here. (…) I think it was a conscious choice. (…) It comes with many things. (…) I can't imagine living as a homosexual in the city X [in Poland], (…) Berlin is a window to normalcy for me (Marek, Wave 3).

People in the ‘upward’ sequence were strongly attached to the current place of residence abroad which shows a sedentary pattern of mobility (Engbersen et al. Citation2013). At the same time, they seemed to be highly mobile, ready to move from one country to another depending on life opportunities. Longitudinal data showed that success related to mobility proved the decision to be mobile and encouraged further potential mobilities. Young people who shaped the ‘upward’ sequence also developed ‘spatial reflexivity’: the ability to think geographically about life choices (Cairns Citation2018, cf. Pustulka and Winogrodzka, Citation2021).

I don’t have idée fixe that I will live in Poland. It will probably depend on this labour market, here, for both of us, and I don’t know, from atmosphere or some, I don’t know, possibly, opportunities that will open … (Natalia, Wave 2).

Type 2. Yo-yo sequence

Unlike the upward type, the yo-yo sequence is an example of a discontinuous sequence characterised by the reversibility of transitions (cf. yo-yo transition by Hörschelmann Citation2011; Borlagdan Citation2015). The ‘yo-yo’ metaphor indicates the fragmentation of contemporary transitions (Du Bois-Reymond and López Blasco Citation2003; Leccardi and Ruspini Citation2006). A transitional yo-yo effect brought by mobility experience causes metaphorical ‘return social mobility’ to the labour market positions from the past (Winogrodzka and Sarnowska Citation2019).

AE: United Arab Emirates, CH: Switzerland, NL: Netherlands; cf. the same occupational legend as in type 1.This kind of sequence was typical for people subject to high mobility capacities and imperatives. People who represented the yo-yo sequence had great propensity to move. They had internationally transferable skills and credentials, financial and emotional support from parents, support from educators or societal endorsement of mobility (Cairns Citation2018). In the mobility narratives there was a lot of non-material reasoning behind undertaking mobility:

I was hungry, wanted more, had a desire to travel. I generally knew there’s more to life than just Poland, Warsaw. (…) It was such a strong conviction inside me. (…) And I think I have been bitten by the travel bug, as I was at this Erasmus in Budapest and I wanted more. (…) Absolutely it was not caused by any financial motivations (Ada, Wave 1).

The amount of work was really overwhelming, sometimes I did 160 extra hours per month, we basically slept almost at work, so it also affected my private life because I didn't see my boyfriend at all, I worked 6/7 days a week sometimes. (…) The distribution of private and professional life was very unequal (Jola, Wave 2).

The idea of leaving didn’t arise, it only imposed itself because I fell in love. We were in a relationship for two years and after two years it had to be decided that … someone just had to come to someone, right? And it fell on me, we thought it would be easier for me. What is quite controversial now. (…) I don't have a permanent job here (Alicja, Wave 2).

Moving abroad was a distinct turning point in the career paths of young persons. International mobility brings sudden, unexpected, often radical changes enhancing the yo-yo sequence (cf. Thomson et al. Citation2002):

Later there is a move to Switzerland and a great professional collapse, unsuccessful attempts to change the sector. (…) Suddenly, from a professional pedestal, I fell into the role of a housewife. I sit at home, I have no work, I don’ know what to do with myself, I don’t earn money, I’m not independent (Alicja, Wave 2).

Due to many difficulties that young migrants faced despite many anchors in the host country and intentions to settle longer-term, many of them existed in a state of limbo - ‘neither here nor there’:

For some time when I say that “I'm going home”, I mean this house, here, in Switzerland because here is my husband, here is my dog, here are my books, (…) but on the other hand, well, my family is in Poland, my friends and relatives are also in Poland. (…) This is probably the stage of emigration, (…) we feel like this, neither here nor there. (…) This is the stage of being in between (Alicja, Wave 2).

I don't know yet (where my home is). On the one hand, I don't feel at home here yet, and on the other hand, when we were in Poland recently, I also didn't feel at home there (Jola, Wave 2).

It is worth emphasising that people experiencing the yo-yo sequence search for a stability. They aspired to and, in the long run, achieved upward socio-economic mobility abroad. They transitioned from an initial acceptance of ‘any’ job (which was dictated by the need to find any employment very quickly to satisfaction of primary need) to a ‘better’ job (feasible thanks to improved language skills and better knowledge of the whole ‘new system’) and, for some, to a ‘dream’ job that reflects their aspirations and qualifications (Parutis Citation2014). In contrast to the upward sequence, the yo-yo sequence was marked by a clear discontinuity. ‘Everyone is new to me and it is really starting everything, all my life - not only social but also professional - from scratch’ (Jola, Wave 2). As the above quote showed, ‘starting from a scratch’ was not only about re-entering the labour market, but also re-building social relations, a significant element of mobile transitions (Robertson, Harris, and Baldassar Citation2017).

Type 3. Zigzag sequence

The zigzag sequence is disordered by U-turns. The transition process of young people experiencing the zig-zag path did not follow predictable patterns. Typical for the zigzag sequence were sinusoidal and fragmented transitions which cause ups and downs (cf. Grabowska Citation2016). Here, mobility led to high changeability in a person’s occupational path. The zigzag sequence fitted into the pattern of the de-standardization of youth transitions (Walther et al. Citation2002; Leccardi and Ruspini Citation2006). In contradiction to representatives of the upward sequence, people undergoing zigzag sequences very often did not know which paths they want to take, which tended to result in job-hopping. As a result, their sequences contained more positions which last longer and more complicated than in the yo-yo sequence.

IT: Italy, NO: Norway, MX: Mexico; cf. the same occupational legend as in type 1.

The zigzag sequence was typical for people with low mobility capacities and high mobility imperatives. In this case, we can observe limited local opportunities and insufficient life chances in the place of origin as the key mobile imperatives (Cairns Citation2018). The constrained labour market entry leading to ‘dead-end’ jobs but also local cultural insularity was visible in the narratives of mobile young adults:

Looking for a job abroad presented a massive number of different possibilities (…) and my city (in Poland) is a total wall, and limitations everywhere and no openings (Kora, Wave 1); I had a feeling that I was simply choking there, I didn't want to be there, needed something else (Iga, Wave 2).

First, I went to France. (…) Not to stay there, just to earn some extra money. (…) And I didn't even think about going abroad, I even told myself that I wouldn't learn languages, because I would be in PL all my life. But later life verified this a little. The earnings that were offered [in PL] were inadequate (…) and I left and started earning money (Maks, Wave 1).

If you want to earn money, you just need to go for it but you don't know if they pay you. So, it's life from day to day, on the edge, in that you don't have a contract, you don't have insurance, you don't know if a brick will fall on your head, you don't have a clue. And hard physical work, not 8 h, just … just more. In different places, with different people, and illegally (Maks, Wave 1).

When it comes to professional experience, they (jobs abroad) are altogether useless to me, but they were very much needed financially. (…) From a professional perspective, these jobs don’t matter anymore. (…) I don't even have them in my CV (Eliza, Wave 1).

I don't have my home at the moment, I don't feel like I belong anywhere (Kornel, Wave 3);

Many options are open, I don’t lock myself down to a place (Iga, Wave 2).

Type 4. Flat sequence

The fourth type of sequence is ‘flat’, with no relevant impact of mobility on the objective dimension of occupational sequence and transitions. Representatives of this sequence remained in the same occupational category before, during and after mobility experience. However, this did not mean that their mobility did not affect their social and occupational mobilities per se.

BE: Belgium, IE: Ireland, US: United States of America, cf. the same occupational legend as in type 1.Most of young movers conforming to the flat sequence already reached relatively high positions in Poland, and they continued their well-developed careers abroad, although they might experience some small downward swings upon moving:

I changed two countries, and in these two countries, (instead of senior) I started from the position of junior, because I had no other option, because it was my first job (in this country) (Brygida, Wave 2).

When it comes to such experience of scientific work abroad, first of all, it gave such a perspective that I saw that different things can be done in a different way (…), it broadened my perspective (…). [Earlier] I had such a conviction that [I can live] only in Poland, (…) and now I think that interesting things are also in others places and that it won't be a big tragedy for me if I had to move (Oliwia, Wave 3).

I never thought (…) that one day I will leave (Poland), I don't think that this thought ever occurred to me. (…) .These trips surely increased my self-confidence and self-esteem, although I don't feel that they have guided me very much (Dagmara, Wave 2).

In the company where I was employed in Ireland, I was a member of the CSR department. (…) Many of the events that we organised (…) were related to environmental protection and ecology. At that time, my ecological awareness has increased a lot. Certainly, it was also influenced by people that I’ve met (…), who inspired me to further action and to develop these interests (Irena, Wave 3).

Summary and conclusions

Through the analysis of qualitative longitudinal data we managed to reconstruct four typical shapes of mobile sequences of young adult migrants: (1) the upward sequence; (2) the yo-yo sequence; (3) the zigzag sequence and (4) the flat sequence. The analysis proved hierarchies and inequalities in youth mobility that can be both integral to and disruptive of life transitions. Mobile transitions are not exclusively linear and in a one progressive direction. There are also discontinuities, ruptures, yo-yo transitions. Their shapes were conditioned on both individual and structural dimensions including differentiated access to resources but also related to the mobility patterns. below presents the overview summarising the types of mobile sequences, transitions within sequences, mobile capacities and imperatives and types/patterns of mobility.

Table 1. An overview of findings: Types of sequence, transitions within sequences, mobile capacities and imperatives, types of mobility

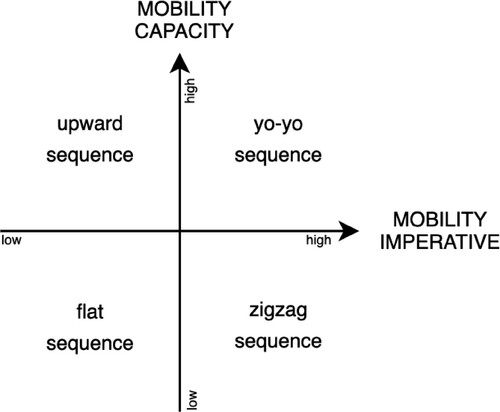

Our analysis also proved that people who experienced high level of mobility imperatives tended to follow yo-yo and zigzag sequences while people who did not experience imperatives followed a sequence of flat or upward shape, as presented in .

Figure 1. Types of social sequences depending on the level of mobility capacity and imperative. Source: Own elaboration based on mobility capacity and mobility imperative (Cairns Citation2018).

Because our analysis was conducted mostly on university graduates we can state that this group contained many inequalities, particularly with regard to the mobility capacities they obtained before international mobility. To a certain degree, the analysis confirmed the Mathew effect (Merton Citation1968), where the rich are capable of ordering their sequences more agentically than people who do not have resources (i.e. ‘the rich get richer’). Young people with high mobility capacities but also those with low level of mobility imperatives while learning to work and live in a different environment and improving language skills, develop and enhance their human capacities for self-development like self-efficacy, self-determination, self-articulation, self-reliance and self-confidence (Grabowska and Jastrzebowska Citation2019). They capitalise their movements, tend to maximise their competences and transform them into resources. The cases of our interviewees show not only the link between spatial and social mobility (Kaufmann, Bergman, and Joye Citation2004) and the strong impact of mobility on young people’s soft skills (Grabowska Citation2019) but also changing, growing aspirations of young people in a temporal perspective influenced by mobility experience (cf. Brannen and Nilsen Citation2002; Robertson, Harris, and Baldassar Citation2017) and mediated by foreign language fluency (Cairns Citation2018).

In turn, in the case of representatives of the yo-yo and zigzag sequences – both with high level of mobility imperatives – the international mobility experience serves to fill in certain competence gaps, rather than to develop them and to convert competences into other resources. These young people are engaged during international migration in acquiring core skills which they missed to acquire at home and at school.

Typologies based on social sequences’ shapes complemented with mobility capacities and imperatives and mobility patterns thus offer new opportunities for methodological and theoretical explorations. As researchers we should bear in mind that the impact of mobility on a sequence is not necessarily immediately visible, and may only be identifiable after some time. For this reason, it is necessary to conduct Qualitative Longitudinal Research (Neale Citation2019) embedded in the spatial and temporal complexity and in the processes of both youth transition and migrancy (Robertson, Harris, and Baldassar Citation2017).

Therefore the main contribution of our article is the conceptual development of typical shapes of social sequences of young adult migrants with the clear reference to the patterns of geographical mobility (Engbersen et al. Citation2013) and mobility capacities and imperatives (Cairns Citation2014, Citation2018). It gave us opportunities for applying and testing the approach of ‘mobile transitions’ offered by Robertson, Harris, and Baldassar Citation2017 on the pages of this journal. We also showed that an alert on youth transitions undergoing de-sequentialization and being subjects to growing contingencies (Leccardi and Ruspini Citation2006) is partly valid as we still observe many ordered sequences with classical upward and flat social mobility. It is also important to highlight that young adult migrants ‘normalise’ experiences of international migration as being ‘natural’ part of their life-course sequences. It is not the unusual event anymore as for older generations but normal dynamics of life.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, B. 2000. Doing the Dirty Work? The Global Politics of Domestic Labour. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Borlagdan, J. 2015. “Inequality and 21-Year-Olds’ Negotiation of Uncertain Transitions to Employment: A Bourdieusian Approach.” Journal of Youth Studies 18 (7): 839–854.

- Brannen, J., and A. Nilsen. 2002. “Young People’s Time Perspectives. From Youth to Adulthood.” Sociology 36 (3): 513–537.

- Brzinsky-Fay, C., and H. Solga. 2016. “Compressed, Postponed, or Disadvantaged? School-to-Work Transition Patterns and Early Occupational Attainment in West Germany.” Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 46: 21–36.

- Cairns, D. 2014. Youth Transitions, International Student Mobility and Spatial Reflexivity: Being Mobile? Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cairns, D. 2018. “Mapping the Youth Mobility Field. Youth Sociology and Student Mobility and Migration in a European Context.” In Handbuch Kindheits- und Jugendsoziologie, Springer Reference Sozialwissenschaften, edited by A. Lange, H. Reiter, S. Schutter, and Ch. Steiner, 463–478. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

- Cornwell, B. 2015. Social Sequence Analysis: Methods and Applications. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- CSO. 2017. Informacja o rozmiarach i kierunkach czasowej emigracji z Polski w latach 2004–2016. Warszawa: Glowny Urzad Statystyczny.

- Du Bois-Reymond, M., and A. López Blasco. 2003. “Yo-yo Transitions and Misleading Trajectories: Towards Integrated Transition Policies for Young Adults in Europe.” In Young People and Contradictions of Inclusion: Towards Integrated Transition Policies in Europe, edited by A. López Blasco, W. McNeish, and A. Walther, 19–42. Oxford: Policy Press.

- Engbersen, G. 2018. “Liquid Migration and Its Consequences for Local Integration Policies.” In Between Mobility and Migration The Multi-Level Governance of Intra- European Movement, edited by P. Scholten and M. van Ostaijen. IMISCOE Research Series. Springer Open.

- Engbersen, G., A. Leerkes, I. Grabowska-Lusinska, E. Snel, and J. Burgers. 2013. “On the Differential Attachments of Migrants from Central and Eastern Europe: A Typology of Labour Migration.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 39 (6): 959–981.

- Fries-Tersch, E., M. Jones, B. Böök, L. de Keyser, and T. Tugran. 2020. 2019 Annual Report on Intra- EU Labour Mobility. Brussels: European Commission Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion Directorate D – Labour Mobility.

- Glick Schiller, N., and N. B. Salazar. 2013. “Regimes of Mobility Across the Globe.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 39 (2): 183–200.

- Grabowska-Lusinska, I., and M. Okolski. 2009. Emigracja Ostatnia? Warszawa: Scholar.

- Grabowska, I. 2016. Movers and Stayers: Social Mobility, Migration and Skills. Frankfurt Am Main: New York: Peter Lang.

- Grabowska, I. 2019. Otwierając Głowy. Warszawa: Scholar.

- Grabowska, I. 2020. “The Transition from Education to Employment Abroad: The Experiences of Young People from Poland.” Europe-Asia Studies 68 (8): 1421–1440.

- Grabowska, I., and A. Jastrzebowska. 2019. “The Impact of Migration on Human Capacities of Two Generations of Poles: The Interplay of the Individual and the Social in Human Capital Approaches.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1679414.

- Heinz, W. R. 2003. “From Work Trajectories to Negotiated Careers: the Contingent Work Life Course.” In Handbook of the Life Course, edited by J. T. Mortimer, and M. J. Shanahan, 185–204. New York: Kluwer/Plenum.

- Hörschelmann, K. 2011. “Theorising Life Transitions: Geographical Perspectives.” Area 43 (4): 378–383.

- Janta, H., C. Jephcote, A. M. Williams, and G. Li. 2019. “Returned Migrants Acquisition of Competences: the Contingencies of Space and Time.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1679408.

- Kaufmann, V., M. M. Bergman, and D. Joye. 2004. “Motility: Mobility as Capital.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 28 (4): 745–756.

- Kindler, M. 2018. “Poland’s Perspective on the Intra-European Movement of Poles.” Implications and Governance Responses, in Between Mobility and Migration: The MultiLevel Governance of Intra-European Movement, IMISCOE Research Series, Springer.

- King, R. 2018. “Theorising New European Youth Mobilities.” Population, Space and Place 24 (1): e2117.

- Krings, T., A. Bobek, E. Moriaty, J. Salamónska, and J. Wickham. 2013. “Polish Migration to Ireland: ‘Free Movers’ in the New European Mobility Space.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 39 (1): 87–103.

- Leccardi, C., and E. Ruspini. 2006. A New Youth? Young People, Generations and Family Life. Hampshire: Ashgate.

- Lulle, A., H. Janta, and H. Emilsson. 2019. “Introduction to the Special Issue: European Youth Migration: Human Capital Outcomes, Skills and Competences.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183X.2019.1679407.

- Merton, R. K. 1968. “The Matthew Effect in Science: The Reward and Communication Systems of Science are Considered.” Science 159 (3810): 56–63.

- Morosanu, L., A. Bulat, C. Mazzilli, and R. King. 2019. “Growing up Abroad: Italian and Romanian Migrants' Partial Transitions to Adulthood.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 45 (9): 1554–1573.

- Neale, B. 2019. What is Qualitative Longitudinal Research? London: Bloomsbury.

- Parutis, V. 2011. “White, European, and Hardworking: East European Migrants' Relationships with Other Communities in London.” Journal of Baltic Studies 42 (2): 263–288.

- Parutis, V. 2014. “Economic Migrants’ or ‘Middling Transnationals’? East European Migrants’ Experiences of Work in the UK.” International Migration 52 (1): 36–55.

- Punch, S. 2015. “Youth Transitions and Migration: Negotiated and Constrained Interdependencies within and Across Generations.” Journal of Youth Studies 18 (2): 262–276.

- Pustulka, P., D. Winogrodzka, and M. Buler. 2019. “Mobilne pokolenie wyboru? Migracje międzynarodowe a płeć i role rodzinne wśród Milenialsek.” Studia Migracyjne-Przegląd Polonijny 4 (174): 139–164.

- Pustulka, P., and D. Winogrodzka. 2021. “Unpacking the mobility capacities and imperatives of the ‘global generation’.” In Handbook of Youth Mobility and Educational Migration, edited by D. Cairns. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Robertson, S., A. Harris, and L. Baldassar. 2017. “Mobile Transitions: A Conceptual Framework for Researching a Generation on the Move.” Journal of Youth Studies 21 (2): 203–217.

- Sarnowska, J. 2019. “Efekty waskiej i szerokiej socjalizacji dla trajektorii migracyjnych mlodych doroslych.” Studia Migracyjne - Przegląd Polonijny 1 (171): 61–83.

- Szewczyk, A. 2015. “European Generation of Migration: Change and Agency in the Post-2004 Polish Graduates Migratory Experience.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 60: 153–162.

- Thomson, R., R. Bell, J. Holland, S. Henderson, S. McGrellis, and S. Sharpe. 2002. “Critical Moments: Choice, Chance and Opportunity in Young People’s Narratives of Transition.” Sociology 36 (2): 335–354.

- Trevena, P. 2013. “Why do Highly Educated Migrants Go for Low-Skilled Jobs? A Case Study of Polish Graduates Working in London.” In Mobility in Transition: Migration Patterns After EU Enlargement, edited by B. Glorious, and I. Grabowska-Lusińska, and A. Kuvik, 169–190. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Walther, A., B. Stauber, A. Biggart, M. du Bois-Reymond, A. Furlong, A. López Blasco, S. Mørch, and J. M. Pais. 2002. Misleading Trajectories. Integration Policies for Young Adults in Europe? Opladen: Leske and Budrich.

- Winogrodzka, D., and I. Mleczko. 2019. “Migracja płynna a prekaryzacja pracy. Przykłady doświadczeń zawodowych młodych migrantów z wybranych miast średniej wielkości w Polsce.” Studia Migracyjne-Przegląd Polonijny 1 (71): 85–106.

- Winogrodzka, D., and J. Sarnowska. 2019. “Tranzycyjny efekt jojo w sekwencjach społecznych młodych migrantów.” Przegląd Socjologii Jakościowej 15 (4): 130–153.