ABSTRACT

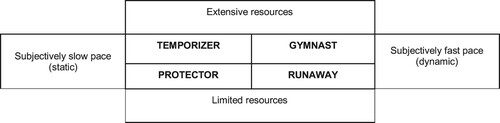

Changes in the intergenerational family relationships are typically seen through the prism of contemporary parents supporting their children long into adulthood, offering their households as ‘feathered nests’ during extended transitions to adulthood. However, the majority of research in this realm comes from established welfare states of Western Europe and the Commonwealth and less explicitly addresses inequalities that mark these processes. Drawing on qualitative longitudinal research on transitions to adulthood in Poland, we use a data set of 127 interviews with university students and graduates to illustrate the process of leaving home in the Central and Easter European context. The paper accounts for both the objective (extensive/limited economic capital or resources) and subjective (fast/slow pace) dimensions crucial for how young people move out from parental homes. Our main contribution is a typology of Temporizers, Gymnasts, Runaways and Protectors as ideal types of pathways to leaving home in Poland.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction: modern transitions and leaving home

Research into leaving home, which ‘represents a major life-course transition’ (Holdsworth and Morgan Citation2005, 2; Wyn Citation2011) and ‘should be regarded as a fluid process rather than a single event’ (Mulder Citation2009, 203), has flourished with both quantitative (e.g. Avery et al. Citation1992; Berngruber Citation2015; Goldscheider and Goldscheider Citation1996; Iacovou Citation2010; Sørensen and Nielsen Citation2020) and qualitative studies (e.g. Holdsworth and Morgan Citation2005; Cuervo and Wyn Citation2014). Moving out from a parental home has become difficult to pinpoint, mirroring the broader shifts in transitions to adulthood on the whole (Mary Citation2014; Wyn Citation2011). On the one hand, it has been argued that many young adults flying the nest represent a generation typically described through the notions of ‘emerging adulthood’, characterized by permissibility towards young people experiencing prolonged periods of exploration and experimentation (Arnett Citation2000; Swartz and O’Brien Citation2009). On the other hand, the changes allowing ‘cushioned’ landings are not universally applicable to all. Both structural and hidden inequalities at the micro level drive the dynamics of leaving home for young people from privileged versus defavorized households (Silva Citation2016; Sørensen and Nielsen Citation2020). In addition, the upended chronology of transitions is exacerbated by the intensity of tempos (Neale Citation2019) ranging from slow- to fast-paced of departures.

The goal of this article is to contribute a qualitative analysis of leaving home in Poland as an input to the existing comparative and quantitative research (e.g. Billari et al. Citation2001; Holdsworth and Morgan Citation2005; Sørensen and Nielsen Citation2020). Methodologically, we draw on two studies on Polish young adults with high educational aspirations, namely university graduates. Focusing on two dimensions (economic capital and the importance of time/pace) in the non-linear and intermittent transitions to adulthood, we offer an agile typology of leaving home. By revisiting the ‘feathered nest/gilded cage’ debate surrounding intergenerational co-residence (Avery et al. Citation1992), we highlight variability of transitional resources in post-1989 Poland.

The article begins with an overview of key literature on leaving home, then narrowed to the Polish context. After a section on data and methods, we proceed to the analysis and propose a typology of moving out from parental home in Poland, crisscrossing two dimensions of economic capital and tempo. Discussions and conclusions pertaining to similarities and differences between the types follow.

Time, space and resources in leaving home

As with other aspects of becoming an adult, leaving home is affected by social and structural changes in the realms of education, labour and alternative family arrangements. While modernity, individualization and risk society (Beck Citation1992; Furlong and Cartmel Citation1997) contribute to the sense of being ‘in a limbo’ or a state of liminality during young adulthood (Holdsworth and Morgan Citation2005; Mulder Citation2009; Swartz and O’Brien Citation2009; Wyn Citation2011), it has been widely noted that intergenerational support plays a crucial role in how the transitions unravel (e.g. Scabini Citation2006; Sørensen and Nielsen Citation2020). Moving towards (housing) autonomy happens against the backdrop of parent–child relationships shifting from structural hierarchies, to emotional ‘mutuality’, closeness and affection (Cuervo and Wyn Citation2014, 909; Iacovou Citation2010).

Three patterns of leaving home have been noted by Gierveld, Liefbroer, and Beekink (Citation1991) as transitions made (1) to live with a partner, (2) to pursue educational or employment opportunities or (3) to establish independence. Across these types, ‘familial influence is regarded as an extension of the economic basis for leaving home’ (Holdsworth and Morgan Citation2005, 31), indicating that social inequalities remain crucial for transitions. Berrington and Murphy (Citation1994) discuss a U-shaped relationship between social class and leaving home, with least and most-privileged youth having a propensity for earlier transitions due to educational pursuits and lack of resources in parental homes, respectively.

Scabini (Citation2006) depict the intricate involvement and intergenerational that make leaving home ‘a joint enterprise’, stating that the older generation may create a ‘scaffolding’ or weave a ‘safety net’ to ultimately facilitate the cessation of co-residence. Therefore, consistent with Arnett’s (Citation2000) ‘emerging adulthood’ as a prolonged period of experimentation and exploration, studies point out ‘gilded cage’ and ‘feathered nest’ in child-centric (middle-class) families that promote educational aspiration, prevent early parenthood/marriage, as well as create cushioned yet confined socialization environments (Avery et al. Citation1992). First, this means that having access to extensive resources comes with a price of young adults remaining under their parents’ control. Second, limitations of Arnett's ‘liberal approach’ pertain to ignoring structural factors that make extended youthfulness possible. Thus Silva (Citation2016) expressed scepticism towards ‘emerging adulthood’ as a concept applicable to working-class families. In a nuanced approach, Sørensen and Nielsen (Citation2020) recently highlighted how ‘soft’ and ‘hard’ individualism operate in leaving home against a backdrop of parenting styles, contrasting middle-class ideas of support with a working-class setting wherein children are expected to ‘take care of things themselves’. More broadly, socio-economic crises that worsen youth's social status increase preponderance for postponement of adulthood that stems from precarity rather than exploration (Cote and Bynner Citation2008).

Besides the constant significance of capital, today's transitions out of the parental home can be seen through the lens of temporal fluidity (Mulder Citation2009; Neale Citation2019). Leaving home ideally relies on ‘the right time’ (Holdsworth and Morgan Citation2005, 22–23) when both parents and offspring see the value of moving out. There is a particular ambivalence in the prolonged co-residence and its resultant interdependencies. Parents may ponder cessation of support due to limited household budgets or because they worry about ‘spoiling’ their children. Furthermore, children residing at home on the cusp of adulthood may experience emotional costs, reporting decreased trust and conflicts (Swartz and O’Brien Citation2009, 222).

To address temporalities, we bring forward Neale's discussion of timescapes, specifically the intensive-extensive tempo. This is to say that pace illustrates a continuum from a turbulence when ‘multiple changes occur in quick succession’ to a much less hectic process wherein shifts happen gradually, without causing chaos or adverse effects (2019: 30). In addition, with prevalence of internal educational mobility in Poland, another vital element from Neale's temporal approaches concerns overlapping of space and time (2019: 34) This plane answers not only ‘when’ but also ‘where’ an event – in this case leaving home – takes place, directing attention to regional variability in how people move between rural/urban or peripheral/central locations (Jones Citation1999; Cuervo and Wyn Citation2014). Place is a signifier of both the distance young adults put between themselves and their parents, and their capacity to afford desirable housing.

Experiencing a different – faster or slower – pace of leaving one's family of origin intersects with individual goals, ranging from objective (e.g. completing education) to subjective (e.g. autonomy) signs of maturation (Gierveld, Liefbroer, and Beekink Citation1991; Holdsworth and Morgan Citation2005). These are further complicated by the temporally regressive or sinusoidal phenomenon of ‘yo-yo’ transitions wherein adult children tend to return home, intermittently or definitely, during the protracted youth or when later crises emerge (Goldscheider and Goldscheider Citation1996; Mulder Citation2009). In Western Europe countries, this produced the moniker of ‘boomerang kids’ (Berngruber Citation2015), fittingly pointing to the effects of resource-rich ‘gilded’ and ‘feathered’ home environments. Labour market conditions influence yo-yo patterns: financial independence decreases its likelihood, as opposite to unemployment making it more probable (Berngruber Citation2015; Cuervo and Wyn Citation2014).

The context of flying the nest in Poland

The studies discussed above originate mainly from the Western/Northern context, despite the importance of cultural variability in leaving home (Billari et al. Citation2001; Holdsworth and Morgan Citation2005). The transition economies of Southern and Eastern Europe are characterized by state retreats from social provision and housing management (Mandic Citation2008; Druta and Ronald Citation2016). Importantly, the EU accession did not rectify this, instead continuing to put the burden of social support on families. Comparing structural factors in leaving home in the enlarged EU, Mandic (Citation2008, 632) classified Poland as a ‘north-eastern’ regime with ‘outstandingly unfavourable opportunity structures in terms of all components of the welfare mix—market conditions (…), underdeveloped private rented sector, and seriously retrenched expenditure for social protection’. The availability and standard of housing (shortages, costly rents and mortgages) position Poland the bottom of the ranking for the European Union (Szafraniec Citation2017).

Therefore, transition remains a ‘family matter’, as also evidenced by the lack of coherent youth or housing policies. Simultaneously, since independent living is a criterion more important than income for quality of life, young adults are likely to rely on parental support (Szafraniec Citation2017). In comparison to other European countries, Polish youth today leave their family nest quite late, namely at the age of 27.6; men are, on average, 2.5 years older than women when they move out (Eurostat Citation2019). In 2018, 58% of Polish people aged 25–29 lived with their parents. Mirroring the intersection of social and structural factors, Krzaklewska (Citation2017) demonstrated intergenerational evaluations of protracted co-residence, contrasting parents who often reprimanded youth for being overly carefree or irresponsible with young adults who blamed staying at home on structural factors.

Research on Polish people moving out from the parental home is scarce and can be better contextualized through broader changes in transitions-to-adulthood. Following the end of communism (1989) and accession to the EU (2004), transitions became hectic and hybrid, with a mix of ‘old’ (sequential) and ‘new’ (prolonged/emerging) patterns (see Szafraniec Citation2017; Sarnowska, Winogrodzka, and Pustułka Citation2018). The tertiary scholar index among 19–24-year-olds is a telling sign of burgeoning aspirations, increasing from 10% in 1990 to 44% in 2018 (CSO Citation2019). Concurrently, age at first marriage has risen from 24 for men and 22 for women in 1989 to 30 and 28, respectively, in 2018 (CSO Citation2019). As many as 72% university students lived off financial support from their parents, indicating a preponderance for what Goldscheider and Goldscheider (Citation1996) call ‘semi-autonomy’, i.e. young people reaching residential but not financial independence. Leaving home does not symbolize cessation of intergenerational solidarity. As Grotowska-Leder and Roszak (Citation2016) indicate, family support spans financial and material remittances, services, information or emotional help. While it mostly flows from parents to children, some young adults declared that they needed to support their parents (4%), also by housing them in their own flats (2%, CBOS Citation2017).

Data and methods

The analysis conducted for this paper is based on data from two research projects. Both focus on transitions to adulthood in contemporary Poland and, as such, explicitly address the topic of leaving home. Methodological frame of Qualitative Longitudinal Research (QLR, Neale Citation2019) and usage of individual in-depth interviews (IDIs) link the studies as well. Projects were approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the implementing institution.

The first study (S1), titled ‘Education-to-domestic and- foreign labour market transitions of youth: The role of local community, peer group and new media’, was conducted as a large-scale QLR over three waves of interviews between 2016 and 2020and concerned a multi-sited research starting in three medium-sized Polish towns (Pustulka, Juchniewicz, and Grabowska Citation2017). For this paper, a subsample of 99 respondents with university degrees (interviews from across three waves) was drawn. While the main themes of the project were mobility, education and work, dedicated modules (and question probes) pertinent to leaving home and broader transition-to-adulthood were present in the interview guides. The second dataset comes from the project called ‘Transition to motherhood across three generations of Poles. Intergenerational longitudinal study [GEMTRA] (S2)’, another QLR which has been underway since 2018 (see Buler and Pustulka Citation2020). The familial relations including leaving parental home were important parts of all IDIs. During biographical interviews with young women in various cities and towns in Poland, we directly probed about the moment of moving home. Data from 28 IDIs conducted in the first wave were selected for this analysis.

Both S1 and S2 used deliberate and snowballing strategies of recruitment. Prior to the interview, participants were provided with information about the study (anonymity, right to withdraw, data use, etc.) and asked to sign a consent form. Within question blocks on leaving home, interviewees were retrospectively reconstructing their personal and family paths, with the assistance of a life-trajectory drawing tool (Neale Citation2019). IDIs were conducted mainly face-to-face, with digital methods implemented sporadically for those who lived abroad in S1.

To summarize socio-demographic characteristics of the cumulative dataset, which consists of 127 interviews with 94 women and 33 men drawn from two studies,Footnote1 it should be stated that the interviewees were born between 1978and 1998either already had or were pursuing university degrees. Their backgrounds differ in terms of coming from villages, small and medium-sized towns (majority), as well as originating from larger cities in Poland (minority). Families of origin are also heterogeneous in that their parents had varied levels of education, financial resources and occupations.

Our work with data followed standards albeit rigorous steps of qualitative analysis under interpretivism (Miles and Huberman Citation1994, 8–12). After meticulous transcription of recordings (voice-to-text), a data reduction phase included developing and applying codes to all material, identifying themes, patterns, and relationships concerning the created codes, as well as summarizing the data with grids and vignettes (Neale Citation2019). At the stage of creating data displays (Miles and Huberman Citation1994), mostly thematic and conceptually ordered approaches focused on pace/tempo and capital in the narratives on leaving home, reconstructed in relation to individual, narrative evaluations of past events. While we checked for alternatives (e.g. parenting styles, historical events), capital and tempo emerged as typology-anchors. Cross-case comparisons were then performed and resulted in the verification of the typology through multi-level extraction and cross-checks. This way, the proposed four ideal-types emerged from abstracting a series of single cases (see Gierveld, Liefbroer, and Beekink Citation1991).

A typology of leaving home

The analysis directed us to two dimensions of the resources available during leaving home and the perceived pace of this exit, bringing together capital as a more ‘objective’ aspect of the economic capabilities and ‘tempo’ as a more subjective expression of the static or dynamic nature of the events related to flying the nest. Based on these two domains, we portray four ideal types () of Temporizers, Protectors, Gymnasts and Runways in the ensuing analysis.

Temporizers: staying close to parents

Young adults representing the Temporizer type are those who await favourable time to leave their parents’ homes at a slow pace. They come from wealthy homes marked by good housing conditions. For them, a departure from a family home is a natural, welcomed step which occurs statically, ‘at the right time’:

I was always growing up with the conviction that after taking A-levels one leaves (this town) (…) Together with everyone else in my family – I was prepared for moving out following high-school. (Alicja, 1984, MT)Footnote2

Pursuing higher education is a must for parents with high capital (see also Avery et al. Citation1992; Gierveld, Liefbroer, and Beekink Citation1991; Druta and Ronald Citation2016), but moving home unfolds differently with regard to where the family of origin happens to live. For young people who grew up outside of metropolitan areas, moving to a university town after completing high school was an internalized path:

I couldn't imagine not going to university. Everyone in my family did. In the back of my mind, I knew that my parents met at the dorm (…) so there was never a plan which did not include me studying. (Karol, 1989, MT)

Conversely, space has other implications for peripheral places of origin (Cuervo and Wyn Citation2014). Halina's parents had a house in a satellite town of a larger city and she followed her father's steady push towards the decision of moving to the closest city, thus staying locally for university:

As long as I can remember, every time we went to the city my dad would say ‘look, this is the university of technology where you will study’ (…) It was natural when it came down to choosing a university that I only looked at this school. (Halina, 1991, ST)

This does not mean that the Temporizers remove themselves from the family setting when educational aspirations take them elsewhere. They often speak of going home to ‘feathered nests’ on a regular basis during university years:

You know how it is during studies: one goes for 2 or 3 weeks and then comes back home, gets homemade food. (For me) it wasn’t far (…) only three hours by train and the ticket price was always the same (…) There was a chance to visit at any moment (Maks, 1987, MT)

Contrary to Temporizers who come from smaller towns, those from bigger cities can live in their parents’ places as long as they wish to. Interviewees from urban centres particularly moved out only when they felt ready, with a slow tempo and parental approval of the chosen timing (see Holdsworth and Morgan Citation2005):

It was at the beginning of university. I studied [in the city where we lived] and moved out somewhere mid-through, during 2nd or 3rd year. This was caused by increasing conflicts with my family but also, well, happened with their tremendous support. We were no longer able to coexist, so it was like “okay, you should move out”. I think it’s quite rare for a family to support a child in moving out because living together ceases to make sense (Barbara, 1979, C)

Even when Temporizers notice something ‘limiting’ in their parents’ control, they rarely prioritize freedom over cultivating relations and resources. Those who come from small towns move to the nearest cities, while the soft-landing in the locality of origin might mean moving within a neighbourhood. Young adults stay in touch with parents, often meet at least once a week and – in case of any difficulties – mother and father are right there, ready to mobilize capital and offer support (see Scabini Citation2006). More often than not, moving out does not impede comforts offered by ‘feathered nests’ whilst benefiting bonds:

[Moving out] really improved our relations, I was at my parents’ place almost every day (…) There was also warm soup that, as a student, I liked to (take advantage of) (Barbara, 1979, C)

Delaying decisions to leave means that young people can steadily gather their own (financial and educational) capital over time, alongside the comfort of knowing that parental resources are there for the taking:

It was a decision taken together. I neither had a boyfriend nor family plans. I realized at some point, after graduating university and completing the first year of my legal career (…), that it is time. I did not want to live with my parents anymore, regardless of what my future held (…) We were talking about whether I should rent or perhaps buy, discussed mortgage and the entire family participated in this. Me moving out was a decision we made together (Aurelia, 1989, C)

Given the absence of turmoil, Temporizers generally do not see yo-yo behaviours (Kaplan Citation2009; Berngruber Citation2015) in housing interdependence as regressions. They rather view boomeranging as a family strategy, profitable for both generations:

I am laughing about moving out from home initially but then moving back again not once but twice in the meantime. First, [me and my partner] had to live somewhere during renovations (…) Second time was when my mother went abroad. I already had a fiancé but moved back because I didn’t want my dad to be alone (…) It also helped us save money for a car, benefitting all (Magda, 1989, C)

The moving out process is intentionally slowed down by both sides and the Temporizers accept both the advantages of the ‘feathered nest’ and potential drawbacks of the ‘gilded cage’. Going back is neither driven by a difficult economic situation, nor tainted by strained relationships between Temporizers and their parents, indicating a free-willed choice concurrent to collective kinship strategizing.

Gymnasts on the home-springboard

Young people fitting into the Gymnast type exercise their move away from a resources-rich parental home at a fast pace. The reasons for their speedy departures are typically relational: Gymnasts seem to contest or question their family milieus (see Swartz and O’Brien Citation2009). This might be driven by a sudden change in the family, as in the case of Marlena whose mother gave birth to twins when the interviewee was 15. She felt she needed to ‘get out of the way’ and trampolined into an alternative living arrangement:

I started high-school in Warsaw when I was 16 and (that meant) I had to start living on my own. (…) I lived with my older brother who was already at the university. I commuted to school, had to cook. I was with my brother but without my parents and that shapes a person, one grows up fast. (Marlena, 1988, ST)

A desire to be away is justified by educational ambitions that the parents equipped with high capital support (Avery et al. Citation1992; Silva Citation2016). Therefore, an escape from a ‘feathered nest’ can be softened by the existing resources, like a family-owned apartment or network. It may also happen laterally, as a means to offset the emotional damage:

Growing up I had a tumultuous relationship with my parents. It turned out easier for me to get along with my grandma than with my parents (…) She lived just 3 minutes away, so everyone was still close-by. When my parents finally divorced, I was long moved out from home. (Marianna, 1984, C)

Our temporal argument is not necessarily about Marianna leaving home as a teen but rather in emphasizing that she subjectively sees it as a decisive and quick response to a crisis. For Gymnasts, the parental home is like a springboard: it guarantees a jump into the world from a privileged position. Its success hinges on intergenerational support (see Berrington and Murphy Citation1994; Scabini Citation2006):

Parents convinced me to buy a flat. It was now or never: they wanted to buy something and I could either opt in or they’d buy it alone as an investment. I said yes and they have been (financing it). (Olga, 1989, MT)

Besides navigating relational tensions and leveraging capital, Gymnasts often disagree with the choices, norms or values imposed by their parents. In many ways, their fast moves show rebellion against the ‘gilded cage’, wherein overprotective parents dictate the rules. The rift might appear in adolescence and unfold throughout moving away:

There was a plan to move away during high-school to [a larger city]. An option to go to a private school. But my parents advised against it, perhaps correctly, to save that money for university (…). I stayed [at home] till A-levels. (Maria, 1987, ST).

Following high-school graduation, Maria was in turmoil, as she only managed to get into university last minute, after being placed on a waitlist:

I had to move out overnight (…) I got a call about getting in, had to pack my life overnight and take it all from my small town to Warsaw. It was the first time I ever went Warsaw, so this was a tremendous change. (Maria, 1987, ST)

From a broader narrative, it transpires that the parents had a rather controlling attitude and were not quite content about their daughter not studying locally. While they had financial means to back their child's choices, they continued to express disappointment in her life and residential choices (see also Krzaklewska Citation2017):

I lived together with my partner of seven years and they openly negated that. They said they were not happy (…) even though it was my apartment and I was graduating university, they said it was unacceptable (…) It was bizarre: we lived together and (…) we were hiding it: whenever (parents) were coming for a visit, he was ‘moving out’ (…) The parents knew and were appalled.

When the discrepancies in values arise, the parents of Gymnasts do not cease support but the relational strain results in the younger generation quickly distancing themselves from home. The ‘gilded cage’ Gymnasts are brought up in at some point suddenly ‘melts’. The tranquillity and vociferousness of intergenerational relations sets Temporizers and Gymnasts apart despite capital alignment, resulting in a subjectively fast-paced self-separation for the latter type.

Protectors in the family puzzle

Next type introduces Protectors who had limited financial resources growing up (see Mandic Citation2008; Druta and Ronald Citation2016) but are nevertheless reluctant or otherwise unable to leave home. The self-perceived slow tempo of departure is rooted in the Protectors safeguarding family survival or well-being. This situation occurred particularly in one-parent families, for interviewees brought up by solo-mothers. Wiktor, for example, moved away from a parental home in a medium-sized town to study in a larger city. Despite being an independent adult by all accounts, he declares he has never truly left:

I still don’t feel completely moved out from home. I am there every 2-to-3-weeks on average, spend weekends there, most of my things are still there. My room, my bed (…) When I say “I go back home”, I mean that place. (Wiktor, 1992, MT)

Wiktor describes his university lodging as temporary and does not associate spatial distance with the process of leaving home (see Goldscheider and Goldscheider Citation1996). Explaining this, Wiktor became protective when the family was abandoned by his father. He started earning quite early, working during high school and doing seasonal work abroad. After becoming financially independent, he started to remit money to his family of origin:

I brought so much money from (working in the UK). Enough to live calmly and not having to count every penny. Bought lots of Christmas presents and even gave my mum extra money. (…) I would always lend mum some money, especially when she needed something urgently.

It is worth emphasizing lasting intergenerational solidarity (Scabini Citation2006), strong bonds and strategizing financial decision together in the face of adversity.

Beyond providing financial support, Protectors also offer emotional assistance to their parents. One of the reasons for slowing down the transition's tempo can be connected with the dissolution/crisis in the parental dyad, leading young people to staying home or going back (see also Goldscheider and Goldscheider Citation1996; Mulder Citation2009). Protector is a pillar of mental support during recovery:

My mum and I moved in with the grandparents (…) after my parents’ divorce (…) Only at the age of 25 I moved out. It was mainly due to going abroad as I got some distance (…) and realized that my mum really does not need me for her entire life, right? However, it caused an empty nest syndrome for her, she is still going through the motions about it (Emma, 1984, ST)

Educational migration enables cutting of the umbilical cord and transition to adulthood in this case:

(Being abroad) made me realize a lot of things, like no longer wanting to stay in my family home. I felt suffocated by Catholic grandparents and my mum who accepts their traditions, even though she has other (beliefs).

Even if more than two generations are entangled in the process of leaving home, capital shortages and tensions preclude family members from operating as ‘joint enterprise’ (Scabini Citation2006), especially when resources are scarce (Silva Citation2016; Cote and Bynner Citation2008) and family bonds are strong. Having parents with substance abuse problem limited Emma's options, so she experienced a yo-yo transition to a parental home during a crisis in adulthood.

Also caught in the web of family support needs, Maciek initially left his parental home to study and likewise spent one year working abroad. He nevertheless returned to the place of origin and continued his tertiary studies through an extramural program, living with a senile grandmother. Despite being nearly 30-years-old, Maciek feels unable to start an independent life:

To put it simply, I am sort of chained to this town (through) my father and now also my grandma. Alcohol made it hard for (my father …) If I had gone further away, perhaps I would have stayed there and would not have all of this on me: a father after a stroke, 94-year-old grandma [who broke her hip] and mum [abroad]. But I am alone and someone has to help (…) I very often have this ugly thought that when people die, then it gets easier. My dad had tried to kill himself (…) my mum cut down the rope when we entered the flat but, I don’t know, 2 minutes and it would have been over, no more trouble. This is in the back of my head and I am not particularly ashamed of this (Maciek, 1991, MT)

The Protectors face a dilemma of being caught in family demands, showing how overwhelming it is to feel responsible for the living conditions of older generations unable to cope on their own. With Protectors, we illustrate a reversed-direction intergenerational solidarity (Grotowska-Leder and Roszak Citation2016) and young adults being ‘left behind’ in the transition process.

Detaching runaways

Various types of inequalities come to the fore for the final type of Runaways, who move out of homes with limited capitals at a fast-pace. While relational problems are not by default present in their parents’ households, the conditions found in their families of origin are conducive to thriving towards a move (see Berrington and Murphy Citation1994). For instance, Ania has started work at the age of 20, right after graduation:

(Leaving home) was affected by the fact that we lived (…) in a 2-bedroom flat and there were 7 of us. I lived with my parents, brother, his wife, young daughter and (…) my nephew, my god-child who was born disabled. (…) Housing conditions were harsh (… .) it was clear that because I started work, I’d be able to support myself (…) and live somewhere separately. (Ania, 1981, ST)

Ania's case of linear trajectory to financial independence (Mary Citation2014) shows fleeing the nest because of structural factors (see also Mandic Citation2008; Krzaklewska Citation2017), namely poor housing conditions she wished to rectify. In addition, a traditional collective of intergenerational family (e.g. Grotowska-Leder and Roszak Citation2016) might be difficult to accept for young people with alternative aspirations:

My older sisters left for university but my brother was 21 when he got married and his wife moved in with us when I was in 5th grade (…) Quickly they had a baby, and I also have a younger sister (…) so one of my chores was to take care of the (young ones). I hated it all these years (…) and could not wait to move out (…). My brother had another child, then a third and we all lived under one roof (…) It was expected of me to help and this caused strain (Ela, 1990, V)

Runaways may see leaving home at a fast speed (see Neale Citation2019) as a ‘one-way ticket’ to a new life, a way to overcome unfavourable social settings. In fact, Ela has left her village of origin and moved to America directly after finishing high-school:

I left a tiny village where I grew up and jumped across the ocean - first time on a plane - to a different continent. At not even 19, I was (…) gone for an entire year(…) Going to the US actually signified moving out. I came back (to Poland) but went straight to the university which was 100 kilometres away. I’ve never gone back.

With an overlap of structural and relational factors, Runaways reflected how limited resources, parents’ lower capital and traditional norms resulted in broken bonds, exacerbated also by experiencing and escaping domestic violence:

I was 16 when I moved out, this was really very quick. Between my parents and me there was never any stability. There were ‘army methods’ (…). I had responsibility over my brothers: I was eight and my brother was five when we were being left at home alone (…) I had absolutely no private life as a teenager (…) even when I was going to meet a friend, I had to take a baby in a stroller with me (Kasia, 1997, MT)

For Kasia, the conflict escalated but coincided with an educational opportunity (Gierveld, Liefbroer, and Beekink Citation1991): she moved in with her grandmother to go to a better school in a different city. The interviewee resents her parents and – in times of crisis in her adult relationship – moved back in with her grandmother, in a peculiar type of a yo-yo move (e.g. Berngruber Citation2015). Similarly, the story of Nadia directly refers to what she calls a ‘cage’, showing an interplay of parental control with morality:

A turning point in my life was when my sister moved out. She met her now-husband at 17 and moved out at 18-years-old. She quickly left [our hometown. My mother had those … ideas about locking us in a golden cage (…) A golden cage of a family home where one should ideally stay (…) My sister’s move (caused) a lot of anger and resentment. My mum, from what I gathered, was against my sister leaving, becoming independent, she saw it as abandonment. I remember she wanted me to promise that I would never leave. (Nadia, 1992, ST)

Nadia's ‘cage’ represents control driven by the traditional and rural habitus, as well as the norm of utmost respect that should be shown to parents/elders (Krzaklewska Citation2017). To protect their children in the conditions of limited (educational and cultural) capital, the parents of Runaways might resort to emotional pressures (Grotowska-Leder and Roszak Citation2016). At certain point, this just becomes too much:

Now I know that (me moving out) was complete madness. A total madness because I knew I was starting to suffocate (…) My mum moved her entire frustration and anger at my sister onto me (…) There was not a single day with fewer than three rows: flying clothes, slamming doors, vexing. It was a terrible time but it was needed for me to start to create boundaries. (My) move was crazy because I moved to the countryside to live with a boyfriend that my parents didn't approve (…) This was an escape, a desperate decision (…) but I would still do it all over again.

For Runaways, the departure means distancing from their parents’ way of life and decamping localities of origin (Jones Citation1999), with a lot of emotional upheaval surrounding the event. This seems more typical for women who experience mother-daughter tensions and are prone to stricter parental control on the basis of morality. Contrary to Protectors who embrace the importance of bonds and intergenerational solidarity, Runaways reject it and seek independence. It should be clarified, however, that the Runaways do not always perceive their speedy and unsupported departure as completely negative, but rather may refer to it as a formative experience or a life-lesson (Sørensen and Nielsen Citation2020):

(After) moving out (…) I had to take out student loans, (money) only lasted from 1st to 15th each month. It was (about) distancing, a necessity to organize everything on my own, getting my life together. While it was really difficult then, today I think it had a positive effect. I would not call it a success but some sort of inner-drive, I understood I’d either do it myself or it will not happen (Kama, 1986, MT)

Due to both parental and state support being unavailable (see Mandic Citation2008; Szafraniec Citation2017), Runaways often allude to being a ‘self-made (wo)man’, speaking about individualism, agency and accountability for one's path, which is indicative of characteristics typifying modern transitions (e.g. Mary Citation2014; Cote and Bynner Citation2008). Their independence devolves on accumulating financial capital which reduces the likelihood of returning to the parental home (Berngruber Citation2015; Iacovou Citation2010).

Discussion

In our typology, we compliment the discrepancies related to economic capital with a subjective understanding of the pace/tempo (Neale Citation2019) as pivotal for a more nuanced depiction of pathways to leaving home today, be it for education or autonomy (Gierveld, Liefbroer, and Beekink Citation1991). First up, young adults in the Temporizer type represent fully fledged ‘emerging adults’, reminiscent of what is observed elsewhere (Arnett Citation2000; Swartz and O’Brien Citation2009). Polish Temporizers benefit from parental support during a prolonged maturation phase initiated by the ‘naturality’ of higher education aspirations (CSO Citation2019). Slow tempo and extensive resources also mean that parents invest into the young adults’ wellbeing and self-development over time (see Cuervo and Wyn Citation2014). Temporizers economically and emotionally enjoy the proximities and affinities in the ‘feathered nests’ (Avery et al. Citation1992; Berrington and Murphy Citation1994; Goldscheider and Goldscheider Citation1996; Iacovou Citation2010), so they are eager to agree with their parents on the ‘right time to move’ (Holdsworth and Morgan Citation2005). Durable bonds make them reluctant to move far, concurrently rendering them willing to embrace engagement in yo-yo moves and offer intergenerational support to their parents in the long-term (see also Scabini Citation2006).

The relational plane differentiates Temporizers from Gymnasts who, all in all, were most represented among our respondents. In the parental households of the latter, moving is a revolution created by a rebellious daughter or son. Gymnasts dynamically abandon what researchers deem ‘gilded cages’ (Avery et al. Citation1992), most notably due to intergenerational rifts in the worldviews of young adults and their parents in Poland (see also Krzaklewska Citation2017). However, we argue that Gymnasts may relatively easily execute their escapes because the family capital facilitates landing on two feet in the new housing scenario. At the same time, Gymnasts are also experiencing profound challenges of emotional and economic entanglements upended by headlong transitions. Therefore, we forecast that reciprocity from children to parents within the kinship structure may not be particularly strong in the Gymnasts’ families over time.

Starting from a non-privileged position, Runaways are just slightly less frequently represented that Gymnasts in our research and share with them a similarity of relationships with parents being marked by strain. However, lack of resources in their homes means that they need to jump head first and forge their own paths (Silva Citation2016; Sørensen and Nielsen Citation2020). In that sense, they often feel like they have nothing to lose (see also Berrington and Murphy Citation1994; Iacovou Citation2010) and choose to go as far as possible in terms of spatial distancing from the place and family of origin. This is conceived of as executing their agency over cutting off ties that represent emotional burdens and bring little value. Autonomy is at the core of the narratives for Gymnasts and Runaways who see the event of moving away as a rapid decision they owned up to. Quite clearly, it is rather unlikely that we will see yo-yo transitions among the young adults representing these two types.

Finally, the fourth and least common type encompasses Protectors who, like Runways, come from families with scarce resources. As a result of the overlapping personal (e.g. a breakdown of a parental dyad, health issues), structural (e.g. unaffordable housing, Mandic Citation2008) and cultural (e.g. morality, Grotowska-Leder and Roszak Citation2016) factors, Protectors cannot offload their duties and continue co-residence with their parents. Even though Protectors we interviewed left their parental homes physically to pursue higher education, they had not left ‘mentally’. Episodes of international mobility may signify distancing that is needed for moving out, though Protectors never feel fully free. On the way to becoming a so-called ‘sandwich generation’ (Grotowska-Leder and Roszak Citation2016), they are likely to boomerang back when a particular need arises in their parents’ home. Besides limited capital, Protectors are peculiarly carrying the ‘family baggage’ created by their parents, which means that they concurrently delay flying the nest and become independent in other (e.g. financial) aspects of adulthood much quicker.

Conclusion

Qualitative research explicitly focused on the narratives of leaving home in Poland remains scarce and this article fills a knowledge gap in terms of the existing studies on leaving home carried out in Western Europe and the Commonwealth (e.g. Holdsworth and Morgan Citation2005; Swartz and O’Brien Citation2009; Cuervo and Wyn Citation2014). By relying on a large qualitative dataset of interviews with university graduates, we contribute a typology of leaving home in Poland, typifying Central and Eastern European region/ ‘north-eastern’ regime (Mandic Citation2008; Billari et al. Citation2001).

Our work hinges upon the continuing importance of capital and the prescient understandings of temporalities (Neale Citation2019). Through the typology, we show that capital allows some well-off Polish parents to create transitional scaffoldings and safety nets conducive to autonomy and maturation (Scabini Citation2006). Conversely, absence of resources forges exclusionary inequalities for those with limited parental support (see Silva Citation2016; Sørensen and Nielsen Citation2020; Cote and Bynner Citation2008), especially in the face of Polish welfare regime failing young people from a structural standpoint (Mandic Citation2008; see also Druta and Ronald Citation2016). The narratives confirm that the state's disengagement solidly places transitional burden on families (see also Scabini Citation2006).

As all qualitative research, the studies have certain limitations, mostly here related to the fact that the interviewees had high educational aspirations that often necessitate particular pathways of leaving home. Furthermore, data collection happened at a particular moment when Poland had relatively good prospects – both in terms of the economic prosperity and certain normalization of the country's European membership. This is perhaps why the data indicates that historical changes – such as 1989 transition or the 2004 EU accession – were not retrospectively seen as markedly impactful for the interviewees’ biographies (see also Sarnowska, Winogrodzka, and Pustułka Citation2018). This is also concurrent with transitions being a ‘family matter’ in Poland (Szafraniec Citation2017), thus making the interviewees less attuned to linking their biographies to history (see also Neale Citation2019). Notably, the stories shared by international migrants were exceptional in this regard as going abroad was a notable catalyst of moving out, often offsetting capital and relational shortages (see Jones Citation1999). Bringing in wider societal context, a clear recommendation for further research would be to investigate how the so-called unsettling events – such as Brexit or the COVID-19 pandemic – might transform the leaving home processes of the subsequent Polish cohorts (see also Settersten Citation2020).

For the interviewed who mostly left home in Poland in the first two decades of the twenty-first century, it has been observed that Polish parents internalized the need to help their children well into adulthood nearly unconditionally (Avery et al. Citation1992; Goldscheider and Goldscheider Citation1996; Mulder Citation2009). However, we also note the processual interlacing of flying the nest with intergenerational tensions and claims around morality and solidarity (Grotowska-Leder and Roszak Citation2016; Krzaklewska Citation2017). Thus moving out in Poland is not a clear-cut departure from a ‘gilded cage’ or a ‘feathered nest’ (Avery et al. Citation1992) but remains interspersed by differently reasoned extended co-residence, yo-yo or boomeranging behaviours of young adults (Berngruber Citation2015). Furthermore, ‘emerging adulthood’ (Arnett Citation2000) is exclusively available to those with extended resources, while many working-class interviewees had to manage alone, under the harsh conditions of ‘hard’ individualism (Sørensen and Nielsen Citation2020; Silva Citation2016).

Polish parents may aspire to the established welfare states’ models of prolonged youthfulness (Arnett Citation2000) through unconditional support offered in ‘feathered nests’ (Avery et al. Citation1992), acceptance of prolonged fluidity (Mulder Citation2009) and yo-yo behaviours in leaving and returning home (Kaplan Citation2009). However, relational tensions around morality and capital/financial shortages may equally prevent realization of such models, resulting in more hybrid transition types in the proposed typology and warranting granular approaches to leaving home in future research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 It should be mentioned that research into leaving home is inconclusive about the impact of gender on the process. We are aware of our sample being biased towards women and while we noted certain gender differences, the data have not been saturated enough to be juxtaposed with our typology. The topic will be kept in mind in our future analyses of broader transitions in Poland.

2 For each respondent, we supply a pseudonym, year of birth and the type of place of origin abbreviated as C – City, MT – Medium-sized Town, ST – Small Town and V – Village, relevant for the discussion of rural/urban spatial distancing.

References

- Arnett, J. J. 2000. “Emerging Adulthood: A Theory of Development from the Late Teens Through the Twenties.” American Psychologist 55: 469–480.

- Avery, R., et al. 1992. “Feathered Nest/Gilded Cage: Parental Income and Leaving Home in the Transition to Adulthood.” Demography 29: 375–388.

- Beck, U. 1992. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. London: Sage.

- Berngruber, A. 2015. “‘Generation Boomerang’ in Germany? Returning to the Parental Home in Young Adulthood’.” Journal of Youth Studies 18: 1274–1290.

- Berrington, A., and M. Murphy. 1994. “Changes in the Living Arrangements of Young Adults in Britain During the 1980s.” European Sociological Review 10 (3): 235–257.

- Billari, F. C., et al. 2001. “Leaving Home in Europe: The Experience of Cohorts Born Around 1960.” International Journal of Population Geography 7: 339–356.

- Buler M., and P. Pustulka. 2020. “Dwa pokolenia Polek o praktykach rodzinnych. Między ciągłością a zmianą.” Przegląd Socjologiczny 69 (2): 33–53.

- CBOS. 2017. ‘Pełnoletnie dzieci mieszkające z rodzicami’, Komunikat z badań 98/2017.

- Cote, J., and J. Bynner. 2008. “Changes in the Transition to Adulthood in the UK and Canada: the Role of Structure and Agency in Emerging Adulthood.” Journal of Youth Studies 11 (3): 251–268.

- CSO/Central Statistical Office. 2019. Higher Education Institutions and their Finances in 2018. Retrieved from: https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/edukacja/edukacja/szkoly-wyzsze-i-ich-finanse-w-2019-r-.html.

- Cuervo, H., and J. Wyn. 2014. “Reflections on the use of Spatial and Relational Metaphors in Youth Studies.” Journal of Youth Studies 17: 901–915.

- Druta, O., and R. Ronald. 2016. “Intergenerational Support for Autonomous Living in a Post-Socialist Housing Market: Homes, Meanings and Practices.” Housing Studies 33 (2): 299–316.

- Eurostat. 2019. When Are They Ready to Leave the Nest? Retrieved from: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/EDN-20190514-1.

- Furlong, A., and F. Cartmel. 1997. Young People and Social Change. Buckinghamshire: Open University Press.

- Gierveld, J. D. J., A. C. Liefbroer, and E. Beekink. 1991. “The Effect of Parental Resources on Patterns of Leaving Home among Young Adults in the Netherlands.” European Sociological Review 7: 55–71.

- Goldscheider, F. K., and C. Goldscheider. 1996. Leaving Home Before Marriage: Ethnicity, Familism, and Generational Relationships. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Grotowska-Leder, J., and K. Roszak. 2016. Sandwich Generation? Wzory Wsparcia w Rodzinach Trzypokoleniowych. Łódź: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego.

- Holdsworth, C., and D. H. J. Morgan. 2005. Transitions in Context: Leaving Home, Independence and Adulthood. Maidenhead: Open University Press at McGraw Hill.

- Iacovou, M. 2010. “Leaving Home: Independence, Togetherness and Income.” Advances in Life Course Research 15: 147–160.

- Jones, G. 1999. “The Same People in the Same Places? Socio-Spatial Identities and Migration in Youth.” Sociology 33: 1–22.

- Kaplan, G. 2009. Boomerang Kids: Labor Market Dynamics and Moving Back Home. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Working Paper, 675.

- Krzaklewska, E. 2017. “W Stronę Międzypokoleniowej Współpracy? Wyprowadzenie się z Domu Rodzinnego z Perspektywy Dorosłych Dzieci i ich Rodziców.” Societas/Communitas 24: 159–176.

- Mandic, S. 2008. “Home-Leaving and Its Structural Determinants in Western and Eastern Europe: An Exploratory Study.” Housing Studies 23 (4): 615–637.

- Mary, A. A. 2014. “Re-evaluating the Concept of Adulthood and the Framework of Transition.” Journal of Youth Studies 17: 415–429.

- Miles, M. B., and A. M. Huberman. 1994. Qualitative Data Analysis: An Expanded Sourcebook. London: Sage.

- Mulder, C. H. 2009. “Leaving the Parental Home in Young Adulthood.” In Routledge Handbook of Youth and Young Adulthood, edited by A. Furlong, 203–210. London: Routledge.

- Neale, B. 2019. What is Qualitative Longitudinal Research? London: Bloomsbury.

- Pustulka, P., N. Juchniewicz, and I. Grabowska. 2017. “Researching Peer Groups with a Temporal Lens. Participant Recruitment Challenges.” Qualitative Sociological Review 13 (4): 48–69.

- Sarnowska, J., D. Winogrodzka, and P. Pustułka. 2018. “The Changing Meanings of Work Among University-Educated Young Adults from a Temporal Perspective.” Przegląd Socjologiczny 67 (3): 111–134.

- Scabini, E., et al. 2006. The Transition to Adulthood and Family Relations: An Intergenerational Approach. Hove and New York: Psychology Press.

- Settersten, R. A., et al. 2020. “Understanding the Effects of Covid-19 Through a Life Course Lens.” Advances in Life-Course Research, doi: 10.1016/j.alcr.2020.100360.

- Silva, J. M. 2016. “High Hopes and Hidden Inequalities: How Social Class Shapes Pathways to Adulthood.” Emerging Adulthood 4: 239–241.

- Sørensen, N. M., and M. L. Nielsen. 2020. “‘In a Way, You’d Like to Move with Them’: Young People, Moving Away from Home, and the Roles of Parents’.” Journal of Youth Studies, doi: 10.1080/13676261.2020.1747603.

- Swartz, T. T., and K. B. O’Brien. 2009. “‘Intergenerational Support During the Transition to Adulthood’.” In Routledge Handbook of Youth and Young Adulthood, edited by A. Furlong, 221–228. London: Routledge.

- Szafraniec, K., et al. 2017. Zmiana Warty. Młode Pokolenia a Transformacje we Wschodniej Europie i Azji. Warsaw: Scholar.

- Wyn, J., et al. 2011. “Beyond the ‘Transitions’ Metaphor: Family Relations and Young People in Late Modernity.” Journal of Sociology 48: 3–22.