ABSTRACT

Although the outmigration choices of young adults from peripheral to urban regions to attend higher education have been researched extensively, young adults’ decisions to stay in, nearby, or return to, the peripheral home region have received less attention. This paper explores how young adults who are engaged in higher education re-imagine narratives related to notions of ‘leaving’ in their mobility biographies to justify their choice to stay in or return to their peripheral home region. We conducted in-depth interviews with postgraduate students in peripheral regions in Denmark and the Netherlands. Our findings confirm the existence of a mobility imperative for young adults in peripheral regions reproduced by both our participants and their social relations. However, we additionally find that young adults re-imagine narratives of ‘leaving’ which simultaneously correspond with contemporary discourses on place and residential mobility in the form of valuing (dis)connection to place, experiencing urban lifestyles, and life phase transitions, but which also open up possibilities for re-evaluating the attractiveness of often stigmatized peripheral regions. We suggest that narratives of ‘leaving’ during higher education help young adults to build what we call ‘symbolic mobility capital’ to mitigate the negative connotations related to living in a peripheral region.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, young adults’ residential mobility patterns have transformed in accordance with changes in the higher education system in Europe (Finn and Holton Citation2019b). Higher education institutions have changed from being exclusive places for a small and often elite part of the population in European countries (Massey Citation2005) to being characterized by massification and widened participation (Osborne Citation2003) of a larger percentage of the youth cohort (Altbach, Reisberg, and Rumbley Citation2009). In most European countries, one-third of the adolescent group will obtain higher education at the master’s level (Statistical Office of the European Communities Citation2018). Consequently, higher education culture and the location of higher education institutions shape and influence the lives, residential and everyday mobility, and identities, of an increasing number of young adult Europeans.

In the field of youth identity and student mobility research, the place of origin in the form of ‘rural’ or ‘urban’ has been acknowledged as a significant identity indicator for young adults. Pedersen and Gram (Citation2018) show how the ‘rural’ and the ‘peripheral’ are perceived as ‘uncool’ places that lack opportunities for young adults (Donnelly and Gamsu Citation2018; Haartsen and Strijker Citation2010; King and Church Citation2013) and are downgraded as places where young adult life can happen. At the same time, recent research shows that being a ‘mobile’ individual has become a resource for transitioning into adulthood (Cairns Citation2014; Thomson and Taylor Citation2005). Mobility experiences have thus become vital assets in the personal biography of individuals (Beck and Beck-Gernsheim Citation2001; Papatsiba Citation2005) because mobile behavior is assumed to be related to the obtainment of symbolic and cultural capital (Holdsworth Citation2009). Geographically mobile behavior in the form of ‘leaving’ is associated with ‘moving forward’, personal development and obtaining social capital (Nugin Citation2014), whereas geographically immobile behavior is perceived as ‘staying behind’, ‘failure to leave’ and low social capital (Carr and Kefalas Citation2009; Looker and Naylor Citation2009). This applies to young adults in general (Cook and Cuervo Citation2018; Forsberg Citation2017; Hjälm Citation2014) and to young adults in higher education in particular (Christie Citation2007; Finn Citation2017; Finn and Holton Citation2019b; Holdsworth Citation2009; Holton and Riley Citation2013). However, current student mobility research shows how young adults tend to relocate to a university in proximity to their ‘home’ region (Donnelly and Gamsu Citation2018) which calls for a more dynamic understanding of young adults’ staying or leaving behavior as part of a continuous process rather than a unique one-off event (Finn Citation2017; Stockdale, Theunissen, and Haartsen Citation2018; Stockdale and Haartsen Citation2018; Coulter, van Ham, and Findlay Citation2016), and where residential mobility might lead to return migration to the home area or the home region at a later stage in life (Haartsen and Thissen Citation2014).

We follow this line of reasoning and claim that the social stigma of rural or peripheral places can actually be diminished through experiences of residential mobility and ‘leaving’, imagined or actual. This article aims to investigate how young adults re-imagine their own mobility biographies in relation to contemporary discourses of the peripheral region as a place where successful adulthood (Haartsen and Thissen Citation2014, 99) is not obtainable with their personal choice of staying in or returning to said regions. We aim to answer the following question:

How do young adults who are engaged in higher education in peripheral regions re-imagine narratives of ‘leaving’ and transition into adulthood in relation to their choice to stay in or return to their peripheral home region?

To investigate this issue, we follow in the footsteps of Finn and Holton (Citation2019b), who find that young adults’ identity performance should be given specific attention when researching the mobility practices of young adults during higher education. They further argue that student mobility research should include attention to political and educational discourses and the specific geographical and social practices that they simultaneously value and exclude.

We conducted this research in two peripheral regions in southwestern Denmark and the northern Netherlands. Both regions have urban areas with higher education institutions, Esbjerg in Denmark and Groningen in the Netherlands. Similar to other peripheral regions, both the regions of southwestern Denmark and the northern Netherlands suffer from the outmigration of young adults to metropolitan and more centrally located urban regions (Sørensen and Holm Citation2019; Thissen et al. Citation2010).

2. Research on higher education student mobility

This research is framed into the two combined concepts of the ‘mobility imperative’ (Farrugia Citation2016) and the ‘student experience’ (Holdsworth Citation2009). Farrugia’s mobility imperative constitutes a spatial and social context in which young adults need to make mobility decisions. The student experience as discussed by Holdsworth contributes to an understanding of mobility/’leaving’ as a form of symbolic capital intertwined with identity development during the time of higher education.

2.1. Outmigration as an imperative in spaces of centralization and the knowledge economy

Outmigration from peripheral regions has previously been explained mostly by structural inequalities between peripheral and urban regions (Hansen and Niedomysl Citation2009); specifically, higher educational institutions are located in urban core regions, which draws away (soon-to-be) highly educated young adults (Drozdzewski Citation2008; Laoire Citation2000; Thissen et al. Citation2010). Research has confirmed these trends in the context of both the Netherlands (Thissen et al. Citation2010) and Denmark (Faber, Nielsen, and Bennike Citation2015), and researchers have begun to talk about a socio-spatial stigmatization of peripheral regions (Meyer, Miggelbrink, and Schwarzenberg Citation2016). For young adults, in particular, this stigmatization results in what Pedersen and Gram (Citation2018) refer to as a subtle ‘uncoolness of place’ that young adults can escape through migration (Faber, Nielsen, and Bennike Citation2015). Farrugia (Citation2016) captures this mix between the structural and social reasons that young adults leave rural and peripheral regions in what he calls a ‘mobility imperative’: young people are faced with an expectation of moving away because if ‘young people wish to take up the subjectivities offered by contemporary youth culture, they must become mobile, either imaginatively or through actual migration’ (Farrugia Citation2016, 843). Farrugia finds that young adults feel forced to respond to these imperatives in some way and that young adults will ‘construct subjectivities and biographies through the mobilization of material and symbolic resources distributed across urban and rural spaces, and form affective attachments to new and old spaces before and after mobility’ (Farrugia Citation2016, 848). Consequently, young adults who choose not to follow the directions of the mobility imperative still feel the need to construct their personal biographies in accordance with it.

2.2. The ‘student experience’ and transitioning to adulthood identity

Finn and Holton (Citation2019b) emphasize that student mobility needs to be understood at the regional and local level in a way that is sensitive to the contemporary experiences of university students. They build on earlier work from Holdsworth (Citation2006, Citation2009), who finds that student mobility is socially constructed through taken-for-granted assumptions about how mobility contributes to transitions to adulthood. She notes that ‘the expectation that going to university means moving away continues to shape students’ experiences of and attitudes to university life’ (Holdsworth Citation2006, 1849). The transition to adult identity occurs through the ‘student experience’, which is accessed by leaving the home locality and is associated with independence and autonomy (Holdsworth Citation2006, 1857). A growing number of researchers emphasize that the normativity of student mobility behavior is related to higher education as an opportunity for the accumulation of symbolic and cultural capital (Bourdieu Citation1986; Jamieson Citation2000; Rye Citation2006; Nugin Citation2019) in the form of either educational titles or self-development and identity transformation (Finn and Holton Citation2019b; Yoon Citation2014). The intertwining of the culture of higher education with mobility expectations for young adults has also been found in other European contexts (Farrugia, Smyth, and Harrison Citation2014; O’Shea et al. Citation2019), not least for young women, who have a higher tendency to leave the peripheral region to pursue higher education (Faber, Nielsen, and Bennike Citation2015; Wiborg Citation2003). Other researchers have drawn similar conclusions about residential mobility as part of ‘rites de passage’ for young adults; however, it seems that geographical location as well as social background nuance the effect of this predisposition for young people to move away (Mitchell, Citation2003). According to Finn (Citation2017), student mobility should not be reduced binary events because this tends to neglect the dynamic of significant ‘affective experiences’. Finn (Citation2017) builds on emotionally infused reflexivity from Holmes (Citation2010) as an analytical tool for ‘thinking about how decisions and orientations towards work, study and mobility involve emotional processes as well as inculcated social and cultural knowledge’ (Finn Citation2017, 745). Thus, the time of higher education simultaneously becomes an opportunity for educational progress and a specific life phase characterized by opportunities for identity transformation and self-realization related to the mobility experience (Papatsiba Citation2005). From this perspective, the identity dimension is central when making sense of young adults’ mobility behavior. In summary, following the theoretical framework of Farrugia (Citation2016) and Holdsworth (Citation2006), we assume that young adults who have chosen to stay in or return to their peripheral home region will construct narratives that link their geographical mobility experience with narratives of accumulating symbolic resources in the form of identity transformation, self-realization, independence and autonomy. We expect this emphasis to be related to their spatial context of the stigmatized peripheral region in which they have chosen to remain or to return.

3. Materials and methods

3.1. Research settings

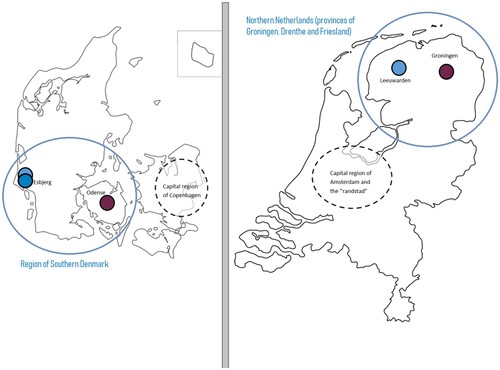

The settings for this paper are two peripheral regions: the region of southwest Denmark and the region of the northern Netherlands. In the Netherlands, most urbanized core areas are located in the west of the country surrounding the capital of Amsterdam and the polycentric ‘Randstad’ area. In a similar way, the region in southwest Denmark is in geographical opposition to the capital core area of Copenhagen and its surroundings on the island of Sealand to the east. Both regions have two main urban centers (Odense and Esbjerg, Groningen and Leeuwarden) where several higher education institutions are located (see ).

3.2. Recruiting participants

The 20 interviews for this paper were conducted with postgraduate students from comparable master’s programs at the University of Southern Denmark (SDU), University of Aalborg (AAU) and University of Groningen (UG). SDU and AAU share a campus-site in Esbjerg. The participants were all born in villages, towns, cities or rural areas in the region of the university where they pursued their postgraduate education. Participant recruitment ended when the point of saturation was achieved according to the researcher. The resulting sample included 10 male and 10 female respondents. Of these, 8 pursued a master’s degree at SDU, 3 pursued a master’s degree at AAU, and 9 pursued a master’s degree at UG. Most participants were between 23 and 26 years old, while two students were 37 and 43 years old at the time of the interview. These were included as it corresponds with earlier findings of peripheral stayers tending to be older than the average student (Mærsk et al. Citation2021).

3.3. Interviews and narrative approach

By exploring the narratives related to the mobility biography constructed by the respondents in this research, we identified the role of ‘leaving’ in the identity production (Riessman Citation2008) of young adults in higher education in the context of the peripheral region. We explore the ‘fusing’ of the mobility experience by looking at the role young adults give to this experience, how they frame it in relation to place and to their own identity development. We pay close attention to how the relational context (Mason Citation2004) of the young adults in the form of family, friends or other influencers (Thomassen Citation2021) in the narratives of the respondents. The interviews were transcribed and coded in NVivo in several rounds following the narrative thematic field analysis approach (Rosenthal Citation1993). The analysis consisted of reconstruction of the subject’s own interpretation of and reflections about experiences of mobility, place, relations and identity construction and the thematic classification of these experiences (Rosenthal Citation1993, 61). Additionally, by tracing the classification of the peripheral location by the respondents, we follow Hickman and Mai (Citation2015) and Eriksson (Citation2015), who emphasize that the notion of place is closely related to narratives of mobility and identity construction.

The 20 semistructured interviews took place during the period from March to July 2018. Of these, 18 interviews were conducted on or near university campuses, and two interviews were conducted online via Skype. The respondents were interviewed individually, and the interviews lasted between 45 and 120 min. The interviews started with the time when the participants entered higher education and ended with their graduation and dreams of the future.

4. Results

4.1. Local leaving and regional staying

At first glance, the mobility biographies varied greatly between the 20 interviewees (see ) in our analysis. However, regardless of their actual mobility experiences, the narratives they related to their mobility choices were strikingly similar, as will be further developed in the next two subsections.

Table 1. Mobility biographies and self-narratives.

Our data show a strong sense of multiscalarity of mobilities in our respondents’ narratives. Experiences of leaving, staying and returning to their local place of origin (the locality, village or city they grew up in) had very different connotations than experiences of leaving, staying or returning to the home region (the province in which their place of origin was located). Where staying in the local home place was related to fear of stagnation and stigmatization, staying in the home region was related to a sense of belonging and staying close to relatives, often parents, combined with new possibilities. Most of the participants identified with being stayers in the home region while simultaneously considering themselves leavers from their home village. On the local level, our respondents’ perceptions can be classified into three different mobility categories:

‘Local stayers’ (2/20), who stayed in their home locality/village/city where they grew up,

‘Local returners’ (5/20), who returned to the home locality/village/city where they grew up after having temporarily lived somewhere else, either in or outside the region, and

‘Local leavers’ (13/20), who left the home locality/village/city where they grew up and did not return.

However, it also became evident that the multiscalarity of their place of origin played a vital part in the narratives of our respondents. We discovered that the ‘Local stayers’, ‘Local leavers’, and ‘Local returners’ re-imagined their mobility narratives by clearly distinguishing between the leaving the local and leaving, returning or staying in the region. In the context of the region our participants identified as:

‘Regional stayers’ (13/20), which is ‘Local stayers’, ‘Local leavers’ or ‘Local returners’ who stayed in the nearby peripheral region after having left their local place of origin (either the northern Netherlands or the southwestern region of Denmark),

‘Regional returners’ (6/18), which is ‘Local leavers’ or ‘Local returners’ who returned to the peripheral region or their home locality/village/city after having temporarily lived somewhere else, either in another region in the country or abroad, and

‘Regional leavers’ (1/18), which is ‘Local leavers’ or ‘Local returners’ who left the peripheral region and did not return.

4.2. Balancing the mobility imperative

Even though all participants related their personal narratives to elements of the mobility imperative as described by Farrugia (Citation2016), the analysis of the interviews revealed how the imperative was contested, ‘balanced’ and re-imagined by the young adults. The participants – as well as their social relations – perceived ‘staying’/being immobile as something undesirable and linked it to negative connotations. However, they simultaneously expressed relational narratives of staying attached to friends or family and returning to the peripheral region in the future. This balancing act was clearly apparent in Maria, a 23-year-old woman in Esbjerg, who expressed in detail how much she struggled with making the decision to stay in Esbjerg. She described her awareness that residential mobility in the form of ‘having been somewhere else’ would have looked good on her CV. Her reason for considering transferring for education in another city was

… in order not to be that person that has just done everything in Esbjerg, born and raised, with all my education done here (Maria, age 23, Esbjerg)

This was a typical framing of ‘staying’ as an identification the participants attempted to avoid. They referred to themselves as ‘leavers’ in contrast, for instance, to their high school peers who had remained in the home village. Eight of the participants additionally mentioned how they were influenced by their social relations’ perceptions on ‘staying behavior’, as positioned in opposition to ‘leaving’ behavior, which was identified as essential for ‘becoming’ (Worth Citation2009) an adult. For Maria her supervisor had persistently tried to convince her to leave Esbjerg:

The reason why I wanted to go to Odense was I that I wanted to challenge myself, and the other thing was that I wanted to look better on my, what is it called, CV? … To just have tried something different. I talked to my supervisor in my bachelor’s XX from here […] he tried to convince me to go to Aarhus […] He was like, ‘You are not doing it here!’ (Maria, age 23, Esbjerg)

This in an example of how of residential mobility was highly encouraged by the respondents’ social network. Several of the participants additionally related their motivation to leave to the desire to develop their career, experiencing youth culture in an urban city and a desire for having more opportunities in terms of jobs and cultural experiences, than the area in which they grew up in offered them. This was also reflected in the story of Jonne, a 24-year-old woman in Groningen. Like other participants, she described how the cosmopolitan lifestyle was idealized among herself and her peers:

Like seeing friends living in all these amazing places and just seeing the good parts of living in a big city, that really appealed to me. ‘Oh, you’re just living in this center of Amsterdam, that’s so cool!’ […] You also see media, like social media too, that you just see (…) and it all sounds so perfect. Like, the ideal, like they have accomplished the ideal (Jonne, age 24, Groningen)

Jonne explained that she needed to find a way to justify her choice of remaining in the peripheral region near the village she grew up in. She explained how she used her social relations to help her re-imagine the choice of returning to the region while also escaping the social stigma of being ‘a loser’ by choosing the peripheral region.

Yeah, I really had to take my time to really realize what I wanted and not the general idea about, ‘Yeah, you move to the big city and then that’s where are you going to make it’ […] but then I thought ‘Yeah, of course it’s a legitimate reason just to stay here, and you are not a loser if you do so’. So, it took me some processes of understanding or just realizing that it isn’t … its legitimate to stay here if you like it. (Jonne, age 24, Groningen)

The respondents expressed a high amount of ambivalence in relation to negotiating with the expectations of the mobility imperative. They expressed feelings of needing to balance between wanting to be mobile and thereby making the transition into adulthood but still remaining in the nearby region during their higher education. Most of them wanted to both experience the urban life while still maintaining a relationship with the people and the place in their home locality through everyday mobility (c.f. Finn and Holton Citation2019b). It was evident in the interviews that the peripheral region ranked low in student life parameters and that the peripheral places did not match their image of ‘student life’ and the possibilities for ‘self-fulfillment’ and ‘development’ that they desired from their higher education. However, it this balancing act with the mobility imperative seemed to offer a new perspective to the young adults’ relationship with the peripheral place without social stigma.

4.3. Obtaining symbolic mobility capital and re-imagination of the peripheral region

Mobility, as an opportunity for self-development, self-growth (Cuzzocrea Citation2018) and developing personal qualities (Holdsworth Citation2006), played a major role in how the participants in our study chose to narrate their residential mobility choices. Even though the residential mobility biographies of our participants varied in distance, frequency and duration, the narratives of ‘leaving’ were constructed in similar ways. The participants perceived their place of origin as a place that did not offer them possibilities for identity transformation; instead, they emphasized and re-imagined experienced of having traveled the world (with or without family), living or studying abroad or having done minors or internships in other countries as ways of transforming themselves or transforming their view of the peripheral location and their social relations there. The analysis showed that the distance, frequency or duration of the stay received less attention than the narratives of change and self-development. This was expressed in many of the interviews in this study and was particularly exemplified in the interviews with Rune, a 30-year old male from Esbjerg, and Joost, a 25-year-old male from Groningen. Both participants had chosen to return to their home town in the peripheral region after spending time in the metropolitan regions of their countries. Both participants felt like they had made an untraditional choice by moving back to the peripheral location. When asked why he had chosen to return to Esbjerg, Rune answered,

Well, essentially I just felt that I’ve had a lot of experiences that really kind of made me look at my home city in a different way […]. I’ve lived in Japan for about 11 months, and I’ve lived in Beijing […] I’m not, like, I don’t hate Copenhagen, but I thought … We kind of weighed everything together, and I thought about how my life would be here as opposed to going to Copenhagen. (Rune, age 30, Esbjerg)

This is a good example of how the participants in the study re-imagine their relationship to their peripheral home region through their narrative of ‘leaving’ and having lived somewhere else. Rune framed his experience abroad as something transformative, and ‘leaving’ became a way for Rune to reevaluate his home region. For Rune, the choice of returning was justified through the experience of being away and experiencing other places to be able to appreciate his hometown. This type of re-evaluation was evident in most of the interviews. Many of the interviewees narrated their residential mobility experience in such a way which made room for changes in the relationship between their own identity and preferences and what they perceived that their home region offered. This was similarly visible in the story from Joost in the Dutch context. When asked why he returned to the region for his postgraduate program, he answered,

We went to Amsterdam as the only two from our class […] So, we wanted to get out of our own bubble. […] You really want to integrate into the big town, because you’re not that former boy anymore […] and that also gets you a sense of who yourself are, because at a certain moment, I felt, now I’m not who I want to be. So, I started to get back to those Friesian roots, in a sense. And I think that gives you more insight in who you are. (Joost, age 25, Groningen)

Both participants imagine their residential mobility as a way of obtaining a new perspective on what the peripheral locality might offer them. It was evident in the interviews that the mobility experience had symbolic value in itself and was used by the participants as a tool for obtaining the qualities necessary for successful adulthood (Haartsen and Thissen Citation2014) and to renegotiate the relation to place. For our participants, residential mobility offered an opportunity for narrating elements of transitioning to adulthood, such as detachment from the home locality and identity development. An important finding was that the positive qualities obtained through residential mobility were part of a more or less deliberate strategy of returning to the home region – not necessarily the specific village, but at least the nearby region. Niels, a 25-year-old male from Esbjerg, explained this as follows:

It was always meant to be a temporary thing […] I never planned to live there [i.e. Odense]. Not saying that it wasn’t nice. It was really nice, but I always knew that I would at least try to live around this area […] (Niels, age 25, Esbjerg)

Thus, tracing the narratives of the mobility experiences showed that notions of ‘leaving’ were often intertwined with narratives of returning. Furthermore, the specific mobility experience, for instance, of moving back to the home region after having lived somewhere else was repeatedly connected to the participants’ previous residential mobility biography. Whereas the mobility biographies varied across a continuum, with short-distance mobility experiences at one end and long-distance mobility experiences at the other, the narratives remained similar. In other words, young adults narrate their mobility experience in a way which makes it possible for them to re-imagine their relationship with the peripheral home region. Moving away from the local village while staying in the peripheral region at a nearby university can be instrumental in the process of avoiding association with the negative connotation of being a stayer in a peripheral region. In the words of Jan, a 25-year-old man in Groningen, who reflected on his ambivalence in relation to being a local leaver while simultaneously feeling a strong sense of belonging to the region in general:

It just feels good being here, but like, I didn’t consider myself a stayer [long pause, thinking]; also not a go-er (Jan, age 25, Groningen)

5. Conclusion

In this paper, we aimed to understand how young adults who are engaged in higher education in their peripheral home region re-imagine ‘leaving’ in relation to their choice of staying in or returning to their peripheral home region. We analyzed in-depth interviews with 20 master’s students with a wide range of mobility backgrounds who had all chosen to pursue their master’s degree in the region where they grew up. Similar to other studies, we found that being a geographically mobile individual has become an increasingly important identity trait for young adults, especially for those engaged in higher education (Finn and Holton Citation2019c; Grabowski et al. Citation2017; Holdsworth Citation2009; Holton Citation2015). We contribute to the literature by showing how young adults re-imagine narratives of ‘leaving’ to build what we call symbolic mobility capital: narratives of being mobile persons to showcase their transition into what they perceive as successful adults. This symbolic mobility capital enables them to return to or stay in a peripheral region without the social stigma of staying. While symbolic capital seems to be highly relevant when our respondents interact with their close social relations in the form of friends and family, future research might explore if having symbolic mobility capital relates to other forms of economic or social capital.

We found that young adults balance the mobility imperative by simultaneously identifying as stayers in the home region while identifying as local leavers from their home village. This distinction between the local and the regional proves to be instrumental in the process of staying attached to the home region while fulfilling the mobility imperative and thereby escaping the stigma of being a local stayer. In this process, the mobility experiences during higher education proved to be of high importance because of what we call ‘symbolic mobility capital’. By obtaining this form of capital through mobility experiences (regardless of the destination or duration) while ‘going to university’ (Finn and Holton Citation2019b; Holdsworth Citation2009) in higher education institutions located in peripheral regions (Thuesen, Mærsk, and Randløv Citation2020), young adults seem to be able to renegotiate their relationship with the peripheral region. Thus, while staying in a peripheral region is perceived as unfavorable and a socially unacceptable choice for young adults who wants to progress in life, research needs to move beyond this staying/leaving binary (Haartsen and Thissen Citation2014; Hjälm Citation2014). Young adults renegotiate their relationship to the peripheral region by obtaining symbolic mobility capital through ‘leaving’, for instance, in the form of moving away from their home village to the nearest university town in the region. In this way, the social stigma of being a local stayer can be prevented while remaining ‘nearby’ in the often stigmatized peripheral region. We suggest that obtaining symbolic mobility capital related to residential mobility during higher education mediates the negative connotations of staying in or returning to peripheral regions for young adults.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Altbach, P. G., L. Reisberg, and L. E. Rumbley. 2009. Trends in Global Higher Education: Tracking an Academic Revolution. Paris: United States Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation.

- Beck, U., and E. Beck-Gernsheim. 2001. Individualization – Institutionalized Individualism and Its Social and Political Consequences. London: Sage Publications.

- Bourdieu, P. 1986. “The Forms of Capital.” In Handboook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Education, edited by J. Richardson, 241–258. Westport: Greenwood.

- Cairns, D. 2014. Youth Transitions, International Student Mobility and Spatial Reflexivity. Being Mobile? New York: Palgrave McMillan.

- Carr, P. J., and M. J. Kefalas. 2009. Hollowing Out the Middle: The Rural Brain Drain and What It Means for America. Boston: Beacon Press.

- Christie, H. 2007. “Higher Education and Spatial (Im)Mobility: Nontraditional Students and Living at Home.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 39 (10): 2445–2463. doi:10.1068/a38361.

- Cook, J., and H. Cuervo. 2018. “Staying, Leaving and Returning: Rurality and the Development of Reflexivity and Motility.” Current Sociology 68 (1): 60–76. doi:10.1177/0011392118756473.

- Coulter, R., M. van Ham, and A. M. Findlay. 2016. “Re-Thinking Residential Mobility: Linking Lives Through Time and Space.” Progress in Human Geography 40 (3): 352–374. doi:10.1177/0309132515575417.

- Cuzzocrea, V. 2018. “‘Rooted Mobilities’ in Young People’s Narratives of the Future: A Peripheral Case.” Current Sociology 66 (7): 1106–1123.

- Donnelly, M., and S. Gamsu. 2018. “Regional Structures of Feeling? A Spatially and Socially Differentiated Analysis of UK Student Im/Mobility.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 39 (7): 961–981. doi:10.1080/01425692.2018.1426442.

- Drozdzewski, D. 2008. “‘We’re Moving Out’: Youth Out-Migration Intentions in Coastal Non-Metropolitan New South Wales.” Geographical Research 46 (2): 153–161. doi:10.1111/j.1745-5871.2008.00506.x.

- Eriksson, M. 2015. “Narratives of Mobility and Modernity: Representations of Places and People among Young Adults in Sweden.” Population, Space and Place 23 (2): 1–13. doi:10.1002/psp.2002.

- Faber, S. T., H. P. Nielsen, and K. B. Bennike. 2015. Place, (In)Equality and Gender: A Mapping of Challenges and Best Practices in Relation to Gender, Education and Population Flows in Nordic Peripheral Areas. Copenhagen: Nordic Council of Ministers.

- Farrugia, D. 2016. “The Mobility Imperative for Rural Youth: The Structural, Symbolic and Non-representational Dimensions Rural Youth Mobilities.” Journal of Youth Studies 19 (6): 836–851. doi:10.1080/13676261.2015.1112886.

- Farrugia, D., J. Smyth, and T. Harrison. 2014. “Rural Young People in Late Modernity: Place, Globalisation and the Spatial Contours of Identity.” Current Sociology 62 (7): 1036–1054. doi:10.1177/0011392114538959.

- Finn, K. 2017. “Multiple, Relational and Emotional Mobilities: Understanding Student Mobilities in Higher Education as More Than ‘Staying Local’ and ‘Going Away’.” British Educational Research Journal 43 (4): 743–758. doi:10.1002/berj.3287.

- Finn, K., and M. Holton. 2019b. Everyday Mobile Belonging: Theorising Higher Education Student Mobilities. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Finn, K., and M. Holton. 2019c. “Missing Out, Standing Out or Under Threat? Current Conceptualisations of Student (Im)Mobility and Belonging.” Everyday Mobile Belonging: Theorising Higher Education Student Mobilities, 41–62. London: Bloomsbury Academic. doi:10.5040/9781350041103.ch-002.

- Forsberg, S. 2017. “‘The Right to Immobility’ and the Uneven Distribution of Spatial Capital: Negotiating Youth Transitions in Northern Sweden.” Social & Cultural Geography 20 (3): 323–343. doi:10.1080/14649365.2017.1358392.

- Grabowski, S., S. Wearing, K. Lyons, M. Tarrant, and A. Landon. 2017. “A Rite of Passage? Exploring Youth Transformation and Global Citizenry in the Study Abroad Experience.” Tourism Recreation Research 42 (2): 139–149. doi:10.1080/02508281.2017.1292177.

- Haartsen, T., and D. Strijker. 2010. “Rural Youth Culture: Keten in the Netherlands.” Journal of Rural Studies 26 (2): 163–172. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2009.11.001.

- Haartsen, T., and F. Thissen. 2014. “The Success–Failure Dichotomy Revisited: Young Adults’ Motives to Return to Their Rural Home Region.” Children’s Geographies 12 (1): 87–101. doi:10.1080/14733285.2013.850848.

- Hansen, H. K., and T. Niedomysl. 2009. “Migration of the Creative Class: Evidence from Sweden.” Journal of Economic Geography 9 (2): 191–206.

- Hickman, M. J., and N. Mai. 2015. “Migration and Social Cohesion: Appraising the Resilience of Place in London.” Population, Space and Place 21 (5): 421–432. doi:10.1002/psp.1921.

- Hjälm, A. 2014. “The ‘Stayers’: Dynamics of Lifelong Sedentary Behaviour in an Urban Context.” Population, Space and Place 20 (6): 569–580. doi:10.1002/psp.1796.

- Holdsworth, C. 2006. “‘Don’t you Think You’re Missing Out, Living at Home?’Student Experiences and Residential Transitions.” The Sociological Review 54 (3): 495–519.

- Holdsworth, C. 2009. “‘Going Away to Uni’: Mobility, Modernity, and Independence of English Higher Education Students.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 41 (8): 1849–1864. doi:10.1068/a41177.

- Holmes, M. 2010. “The Emotionalization of Reflexivity.” Sociology 44 (1): 139–154. doi:10.1177/0038038509351616.

- Holton, M. 2015. “Learning the Rules of the ‘Student Game’: Transforming the ‘Student Habitus’ Through [Im]Mobility.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 47 (11): 2373–2388. doi:10.1177/0308518X15599293.

- Holton, M., and M. Riley. 2013. “Student Geographies: Exploring the Diverse Geographies of Students and Higher Education.” Geography Compass 7 (1): 61–74. doi:10.1111/gec3.12013.

- Jamieson, L. 2000. “Migration, Place and Class: Youth in a Rural Area.” The Sociological Review 48 (2): 203–223. doi:10.1111/1467-954x.00212.

- King, K., and A. Church. 2013. “‘We Don’t Enjoy Nature Like That’: Youth Identity and Lifestyle in the Countryside.” Journal of Rural Studies 31: 67–76. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2013.02.004.

- Laoire, C. N. 2000. “Conceptualising Irish Rural Youth Migration: A Biographical Approach.” International Journal of Population Geography 6 (3): 229–243. doi:10.1002/1099-1220(200005/06)6:3<229::AID-IJPG185>3.0.CO;2-R.

- Looker, E. D., and T. D. Naylor. 2009. ““At Risk” of Being Rural? The Experience of Rural Youth in a Risk Society.” Journal of Rural and Community Development 4 (2): 39–64.

- Mason, J. 2004. “Personal Narratives, Relational Selves: Residential Histories in the Living and Telling.” Sociological Review 52 (2): 162–179. Doi:10.1111/j.1467-954x.2004.00463.x.

- Massey, D. 2005. For Space. London: Sage.

- Meyer, F., J. Miggelbrink, and T. Schwarzenberg. 2016. “Reflecting on the Margins: Socio-Spatial Stigmatisation among Adolescents in a Peripheralised Region.” Comparative Population Studies 41 (3–4): 285–320.

- Mitchell, K. 2003. “Educating the National Citizen in Neoliberal Times: From the Multicultural Self to the Strategic Cosmopolitan.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 28 (4): 387–403. doi:10.1111/j.0020-2754.2003.00100.x.

- Mærsk, E., J. F. L. Sørensen, A. A. Thuesen, and T. Haartsen. 2021. “Staying for the Benefits: Location-Specific Insider Advantages for Geographically Immobile Students in Higher Education.” Population, Space and Place 2021: e2442: 1–14.

- Nugin, R. 2014. “‘I Think That They Should go. Let Them See Something’. The Context of Rural Youth’s Out-Migration in Post-Socialist Estonia.” Journal of Rural Studies 34: 51–64. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.01.003.

- Nugin, R. 2019. “Space, Place and Capitals in Rural Youth Mobility: Broadening the Focus of Rural Studies.” Sociologia Ruralis 60 (2): 306–328. doi:10.1111/soru.12276.

- Osborne, M. 2003. “Increasing or Widening Participation in Higher Education? – A European Overview.” European Journal of Education 38 (1): 5–24. doi:10.1111/1467-3435.00125.

- O’Shea, S., E. Southgate, A. Jardine, and J. Delahunty. 2019. “‘Learning to Leave’ or ‘Striving to Stay’: Considering the Desires and Decisions of Rural Young People in Relation to Post-Schooling Futures.” Emotion, Space and Society 32: 100587: 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.emospa.2019.100587.

- Papatsiba, V. 2005. “Student Mobility in Europe: An Academic, Cultural and Mental Journey? Some Conceptual Reflections and Empirical Findings.” International Perspectives on Higher Education Research 3 (5): 29–65. doi:10.1016/S1479-3628(05)03003-0.

- Pedersen, H. D., and M. Gram. 2018. “‘The Brainy Ones are Leaving’: The Subtlety of (Un)Cool Places Through the Eyes of Rural Youth.” Journal of Youth Studies 21 (5): 620–635. doi:10.1080/13676261.2017.1406071.

- Riessman, C. K. 2008. Narrative Methods for the Human Sciences. Thousand Oakes, CA. Sage.

- Rosenthal, G. 1993. “Reconstruction of Life Stories: Principles of Selection in Generating Stories for Narrative Biographical Interviews.” In The Narrative Study Of Lives, edited by R. Josselson and A. Lieblich, 1–20. Newbury Park: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Rye, J. F. 2006. “Leaving the Countryside.” Acta Sociologica 49 (1): 47–65. doi:10.1177/0001699306061899.

- Sørensen, E. S., and A. Holm. 2019. Unge Flytter Vaek fra Danmarks Mindste Byer – har Uddannelse Betydning? Kraks Fond: Byforskning.

- Statistical Office of the European Communities. 2018. Eurostat Regional Yearbook 2018. Brussels: Statistical Office of the European Communities.

- Stockdale, A., and T. Haartsen. 2018. “Editorial Introduction: Putting Rural Stayers in the Spotlight.” Population, Space and Place 24 (4): 1–8. doi:10.1002/psp.2124.

- Stockdale, A., N. Theunissen, and T. Haartsen. 2018. “Staying in a State of Flux: A Life Course Perspective on the Diverse Staying Processes of Rural Young Adults.” Population, Space and Place 24 (8): e2139: 1–10. doi:10.1002/psp.2139.

- Thissen, F., J. D. Fortuijn, D. Strijker, and T. Haartsen. 2010. “Migration Intentions of Rural Youth in the Westhoek, Flanders, Belgium and the Veenkoloniën, the Netherlands.” Journal of Rural Studies 26 (4): 428–436. doi:10.1016/j.jrurstud.2010.05.001.

- Thomassen, J. A. K. 2021. “The Roles of Family and Friends in the Immobility Decisions of University Graduates Staying in a Peripheral Urban Area in the Netherlands.” Population, Space and Place 27: e2392: 1–14.

- Thomson, R., and R. Taylor. 2005. “Between Cosmopolitanism and the Locals.” Young 13 (4): 327–342. doi:10.1177/1103308805057051.

- Thuesen, A. A., E. Mærsk, and H. R. Randløv. 2020. “Moving to the ‘Wild West’ – Clarifying the First-Hand Experiences and Second-Hand Perceptions of a Danish University Town on the Periphery.” European Planning Studies 28: 2134–2152.

- Wiborg, A. 2003. “Between Mobility and Belonging: Out-Migrated Young Students’ Perspectives on Rural Areas in North Norway.” Acta Borealia 20 (2): 147–168. doi:10.1080/08003830310003155.

- Worth, N. 2009. “Understanding Youth Transition as ‘Becoming’: Identity, Time and Futurity.” Geoforum 40 (6): 1050–1060.

- Yoon, K. 2014. “Transnational Youth Mobility in the Neoliberal Economy of Experience.” Journal of Youth Studies 17 (8): 1014–1028. doi:10.1080/13676261.2013.878791.