ABSTRACT

The SchoolStrike4Climate protests have renewed interest in youth political participation, but there has been little scholarly explanation for how young people came to be involved in such actions. While most studies focus on the motivations of participants, this paper considers the role of youth-led organisations in fostering political interest and action for climate justice among young people. Through a case study of the Australian Youth Climate Coalition (AYCC), we argue that over 15 years this youth-led organisation has played a key role by building an enduring organisational base and using multiple strategies to foster understanding and commitment among young people in Australia towards issues of sustainability and action on climate change. Key to the AYCC approach is a climate justice narrative in which young people are legitimate political actors responding to the climate crisis. This narrative manifests in the organisational structure, youthful hybrid repertoires of action and peer-based, educative initiatives. From our analysis, we propose the concept of ‘educative movement-building’ to describe the unique way young people are making organisations and generating broad support for climate justice in Australia with implications for studies of environmental activism and democracy more broadly.

Introduction

The recent School Strike for Climate (SS4C) events around the world have highlighted young people's willingness to act for the environment and broader issues of climate justice. In Australia, student solidarity with Greta Thunberg's SS4C was swift. Between 2018 and 2020 an estimated 500,000 people – most of them school students – took part in SS4C actions both in physical rallies and online.Footnote1 Reports in legacy media suggested that organisers, politicians and public commentators were surprised at the rapid, mass mobilisation of school students (Collin and Matthews Citation2021). However, globally student activism and youth participation in social movements is not a new phenomenon (Earl, Maher, and Elliott Citation2017; Bessant Citation2021; Watts Citation2021). In Australia, students protested against the Vietnam War and South African apartheid (Murphy Citation2015) and have a long, if poorly recognised, history of environmental activism (Collin and Matthews Citation2021). Despite their marginal status in Australian institutional politics, university students and their young peers have led the establishment of national environment initiatives, networks and organisations such as Students of Sustainability in 1991, the Australian Student Environment Network in 1997 (www.asen.org.au), the Australian Youth Climate Coalition in 2006 (www.aycc.org.au) (AYCC) and the Indigenous youth climate network Seed Mob, in 2014 (www.seedmob.org.au) (Partridge Citation2008; Collin Citation2015). Since 2004, similar youth-led climate coalitions have been established in other countries, including the UK Youth Climate Coalition (UKYCC), the Canadian Youth Climate Coalition and the Indian Youth Climate Coalition. In Australia, the AYCC has 120,000 membersFootnote2 and a further 100,000 supporters (AYCC Citation2019). Yet, little scholarly attention has been given to the nature and role of such organisations for climate activism, including the SS4C.

The Australian – and global – youth climate justice movement has emerged in the broader context of shifts in civic and political norms, with forms of participation and digital organising and campaigning that are common, but not specific, to young people (Norris Citation2002; Bang Citation2005; Bennett Citation2008; Collin Citation2008; Loader, Vromen, and Xenos Citation2014; Amnå and Ekman Citation2014; Vromen Citation2017). While social movement participation is facilitated by digital media, organisations continue to play an important role in movement-building (Chadwick Citation2007; Bimber, Flanagan, and Stohl Citation2012; Collin Citation2015; Vromen Citation2017). In Australia, AYCC supported the first local SS4C in 2018 to move to a state and then national series of coordinated actions (Collin and Matthews Citation2021), suggesting its role in moving this ‘political generation’ (Andretta and della Porta Citation2020) to action deserves more attention. While the role of civic organisations for political socialisation has been established (Flanagan Citation2013), there is less understanding of the nature and significance of youthful peer-based (Gordon and Taft Citation2011) and ‘born digital’ organisations (Vromen Citation2017, 203) for fostering political interest and broader environmental and global politics.

In this paper, we use a single case study approach to examine Australia's largest youth-led activist organisation – the AYCC – and empirically investigate two interrelated questions: What role has AYCC played in the emergence of a generation of climate activists in Australia? How does AYCC reflect and shape the political subjectivities of young people who may go on to coordinate and participate in mass protests such as the SS4C? Deploying Vromen's concept of ‘hybrid online campaigning organisations’ (Citation2017) and Maria Bakardjieva's concept of ‘subactivism’ (Citation2009, 92), we use publicly available reports, social media content and interviews with AYCC members and participants to analyse the organisational form and tactics that AYCC has used since 2009 to engage young people and shape youth climate action. In doing so we identify education and training as specific tactics of AYCC – not for those already in the climate justice movement, but for growing awareness and readiness of students to participate over time. While political studies tend to look at the level of education as a determinant of political participation (Vromen Citation2003; Sander and Putnam Citation2010; Dalton Citation2017; Sloam and Henn Citation2019), or as a strategy for movement building (Hall and Ebrary, Inc. Citation2012; Hayward Citation2021) we focus on how AYCC uses ‘an educative approach’ to the organisational structure, communication and repertoires for engaging with Australian young people. Thus, through our analysis, we make an innovative contribution to the theory by demonstrating how youth-led ‘hybrid online campaigning organisations’ tap into ‘subactivism’ through educative movement building to foster individual and collective identity. Our aim is to explain the role of AYCC in the Australian context and, in doing so, consider the potential implications of youth-led organisations for youth environmental activism in other contexts, and globally. First, we summarise explanations for contemporary youth climate activism to highlight the need for scholarship on youth-led organisations.

The rise of youth climate activism

Young people's interest in, and actions to address, environmental issues, sustainability and climate change is partly associated with changes in political practices and identities. The internet and new civic and political norms have increasingly underpinned a shift towards personalisable, individual actions that contribute to a sense of collective effort through networked, issue-based projects, campaigns and actions (Bang Citation2005; Bennett and Segerberg Citation2012; Loader, Vromen, and Xenos Citation2014). How young people conceptualise politics is also more issues-based and contextualised in place and time (Bang Citation2005; Marsh, O’Toole, and Jones Citation2007; Harris, Wyn, and Younes Citation2010; Collin Citation2015). Young people in 2021 have grown up during heightened public and policy debates over climate change, the creation of the 2015 Paris Agreement and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In a time of significant uncertainty and precarity, youthful politics is also driven by economic, political and social inequalities (della Porta Citation2015; Bessant, Farthing, and Watts Citation2017; Pickard and Bessant Citation2017; Pickard, Bowman, and Arya Citation2020) and there is evidence that material concerns feature strongly in the way some young people conceptualise and respond to environmental issues (Pickard, Bowman, and Arya Citation2020; Sloam Citation2020). Simultaneously, while post-materialist values are associated with a rise in contemporary social movements (Henn, Nunes, and Sloam Citation2021), many young people view lifestyle politics as insufficient for dealing with complex problems and call for broader structural and institutional change (Pickard and Bessant Citation2017; Pickard, Bowman, and Arya Citation2020, 262–263).

Increasingly evident in the literature are arguments that youth climate activism is a response to historical and structural inequalities, intersecting forms of disadvantage and multiple crises. For some, environmental activism has its roots in colonial history and Indigenous resistance to colonial violence to people and land – and through continuous care for the country despite ongoing environmental, social and cultural destruction (Watson Citation2017; Bowman Citation2020; Ritchie Citation2020; Collin and Matthews Citation2021). Bowman argues that since at least the 1990s, youth environmental activism has been explicitly concerned with reimagining social relations, solidarity and democracy through the lens of environmental justice (Bowman Citation2020, 3). Studying the youth climate action movement in New Zealand and the Pacific, Richie argues that Maori and Pacifica youth leadership is awakening the understanding of humanist, colonial and racist underpinnings of the current crisis among young people more broadly (Ritchie Citation2020). The student movement for climate action reflects young people's profound engagement with these existential dilemmas, entangled in new political subjectivities associated with social, economic, political and cultural issues (Bowman Citation2020; Pickard, Bowman, and Arya Citation2020). To make sense of this, youth climate activism research examines movement dynamics and effects (Nissen, Wong, and Carlton Citation2020; Bessant Citation2021), youth mobilisation (Wahlström et al. Citation2019; de Moor et al. Citation2020), and the subjective experiences of participants in order to retheorise citizenship, politics and political identity (Nairn Citation2019; Bowman Citation2020; Pickard, Bowman, and Arya Citation2020; Hayward Citation2021). By contrast, the organisations that serve young people, or are created by them to support climate activism, are relatively neglected.

Young people, organisations and political subjectivities

Young people have been at the forefront of developing new organisational forms that reflect their values and promote their interests. In the Australian context, Vromen (Citation2011) argues that while young people may reject ‘institutionalized politics’, they have turned their focus to ‘creating new spaces for everyday politics through local communities and the internet’ (959). These ‘spaces’ include youth-serving and youth-led initiatives or organisations that are often cultural (Harris Citation2003) and issues-based (Vromen Citation2011; Collin Citation2015). Such organisations prioritise youth participation in decision-making or what Pickard calls ‘Do-It-Ourselves’ (DIO) politics (Citation2019); they tend to reflect values that are held to be important by young people – inclusivity, hope, fun – as well as more horizontal and networked forms of governance (Bang Citation2005; Collin Citation2015; Pickard and Bessant Citation2018; Pickard Citation2019). They are also distinct from traditional civic or political organisations in that they have looser, flatter organisational structures, use digital media to mix and blend multiple communication practices and ‘switch’ campaigning repertoires: reflecting what Chadwick has theorised as ‘hybrid organisations’ (Chadwick Citation2007, 295). In her study of the Australian ‘hybrid online campaigning organisation’, GetUp!, Vromen argues that such organisations effectively engage citizens because of their focus on ‘storytelling-led communicative forms of political action, rapid response strategic repertoires and new approaches to fundraising and membership’ (Vromen Citation2017, 3). Story-telling strategies challenge established political organisations by using narrative as a tactic to explain politics and campaigns by creating a plot, identifiable characters, a sequence of events and their effects (Vromen Citation2017, 129). Hybrid organisations use storytelling to generate: a shared understanding of the problem; what is needed to effect change and when; and, who is involved including participants, the organisation and the ‘villains’ or opponents (Vromen Citation2017, 129). Vromen argues that overtime organisations strive to maintain a consistent overall narrative of ‘self/us/now that emphasises unity over adversarial politics’ (Vromen Citation2017, 153). As hybrid online campaigning organisations are now a core element of political engagement, research on their structure and activities is crucial for understanding the evolving political landscape (Vromen Citation2017). Sloam has demonstrated that how young people frame environmental issues both reflects and informs their everyday politics (Sloam Citation2020). As such, we posit that how youth-led organisations frame ‘youth’ and the issue of climate change is important for evolving youth political subjectivities, especially for young people who may not already see themselves as ‘political’ or ‘activist’. As an organisation with a large supporter base of which only a small fraction (approximately 2400) regularly ‘volunteers’ (AYCC Citation2019), we ask how has AYCC built and maintained an interested network ready to act when an opportunity arose? Given that AYCC is specifically interested in very young people who are just beginning to learn about both climate change and politics, our specific concern is not with how they mobilise concerned supporters, but with how they engage young people who may not already understand or identify with climate justice or their rights as citizens.

In studying everyday politics, Bakardjieva (Citation2009) has distinguished political practice according to three levels: firstly, the level of formal institutional politics; and, secondly, what Beck (Citation1997) defined as ‘subpolitics’. For Beck, subpolitics ‘emphasizes forms and manifestations of politics located underneath the surface of formal institutions’, that is, practices that have a public and activist element. Bakardjieva adds a third level, which she names subactivism and defines it as:

a kind of politics that unfolds at the level of subjective experience and is submerged in the flow of everyday life. It is constituted by small-scale, often individual, decisions and actions that have either a political or ethical frame of reference (or both) … (Bakardjieva Citation2009, 92)

Thus, in this study, we examine how the form and repertoires of AYCC have connected with the everyday lives of young people in Australia since 2009 to show how the organisation reflects and fosters young people’s interest in climate change, and their emerging political identities.

Methodology

Among scholars of student climate activism there are calls to move beyond what young people do, to consider the meanings, motivations and politics that emerge through youth participation and organising. For example, Bowman (Citation2019) and Pickard (Citation2019) have argued for research to consider the ‘world making’ dimensions of youth climate activism. Similarly, we have adopted a youth-centred case-study approach to investigate how young people have created an organisation for driving action on climate justice. We acknowledge that as ‘adult’ researchers, allies and parents, we bring our own subjectivities and positionalities within the assemblage of climate activism to this work and that our account is only partial. Our use of a case study approach aims to acknowledge, understand and explain the important role of youth-led organisations; for climate activism, and influencing democratic cultures and institutions capable of dealing with the climate crisis. Our case study approach draws on a range of sources, diverse types of data and use different research methods as part of the investigation (Denscombe Citation2003) and centres youth experience by locating the research in actual sites of engagement, and by taking into account young people's everyday lives (Dunleavy Citation1996, 288; Vromen Citation2003, 82; Sloam Citation2020).

Data and analysis

We drew on three data sources to study the ‘narrative structures’ (Sloam Citation2020) through which AYCC frames the organisation, climate actions and participants: document and website content; semi-structured interviews with organisers and members; and social media posts from AYCC Facebook and Twitter feeds. Data was collected from 2013 to 2021 and provides insight into how the organisation has evolved over time, particularly in the decade preceding the emergence of SS4C. Because of our interest in the relationship between AYCC and the current student climate justice movement, we studied the activities and communications of AYCC in relation to SS4C in 2019. In detail:

Document and website content analysis was conducted on Annual Reports (2009–2015) and Impact Reports (2016–2019) published on the AYCC website and the 2013–2015 Strategic Plan. AYCC website material accessed in February 2021 was searched for events and activities conducted by AYCC from 2018 in reference to SS4C.

Interviews were conducted in 2013 and 2015 with 12 AYCC organisers and members aged 18–25. Participants were recruited directly (AYCC executives, staff and volunteers) and via the Western Sydney University AYCC Facebook page (‘members’). Interviewees were asked about the purpose and structure of AYCC, the mechanisms it uses to engage young people, the role of young people for achieving change and how and why interviewees become involved in AYCC.Footnote3

In February 2021, we studied AYCC social media content posted in 2018 and 2019 by AYCC official accounts on Facebook and Twitter. We searched for AYCC events and activities, particularly those showing connections with the SS4C activities in 2018 and 2019. This material was identified using content analysis of key terms including ‘School Strike 4 Climate’, ‘SS4C’, ‘school strike’ and ‘climate strike’. Facebook and Twitter posts from the same period were also collected as screenshots and identified using content analysis of posts containing the phrase ‘climate justice’.

Drawing on Vromen (Citation2017) we first examined the organisational arrangements and practices. From this, we analysed AYCC tactics which connect young people to the issue of climate justice and foster political interest through ‘frontier situations’ and action via ‘trigger events’ (Bakardjieva Citation2009).

The Australian Youth Climate Coalition (AYCC): fostering climate activism

Framing and organisational form

AYCC was co-founded in 2006 by 65 young people representing youth organisations from around Australia (Partridge Citation2008, 24; Collin Citation2015). Established as a non-partisan coalition with the intent to activate young people for ‘climate justice’, AYCC aimed to ‘educate, inspire and mobilise young people, influence government, and implement concrete solutions’ (Partridge Citation2008, 24). The AYCC has consistently, over time, articulated the mission ‘to build a movement of young people leading solutions to the climate crisis (AYCC Citation2021). In alignment with these values, AYCC has built a ‘purpose-driven’ organisation (Warren Citation1995) underpinned by a theory-of-change approach that is characteristic of many new online campaigning organisations (Karpf Citation2012; Vromen Citation2017). Since 2015, AYCC Impact Reports emphasise youth empowerment: of first nations people through Seed network; through impactful, youthful campaigns; in the settings of everyday life especially communities and schools; and through leadership training.

The structure and discursive presentation of young people who ‘make up’ the AYCC highlights how the organisation generates a ‘self/us/now’ narrative (Vromen Citation2017, 153). A small central team of paid staff and multiple types of volunteer engagement connects with horizontal networks of member-supporters. In contrast with hierarchical political institutions where people rise to be ‘office bearers’ with power and responsibility, the language of AYCC volunteer categories reflects personal and collective learning and learning and contribution ().

Table 1. Comparison framing of AYCC member roles in 2013 and 2019.

In 2019 there were 34 Awesome Core, 78 Super Committed, 275 Active Crew and 1039 Contributing (AYCC Impact Report 2019). As shown in , the ‘Core’ plays a central role in designing campaigns, training and supporting volunteers and growing the network through alliance-building in their local regions. The ‘Super Committed’ volunteers lead local groups in schools, university campuses and their communities. The ‘Active Crew’ participates regularly in local groups and campaign activities and ‘Contributing’ members respond to calls for action and fundraising. The majority of AYCC members are in the wider supporter network: connected via social media, mailing lists and engaged in an ad hoc basis. also shows that since 2013 AYCC language for describing roles has reduced the emphasis on time requirements and focused on the learning opportunities and capabilities of youth as leaders. By 2019 the terminology shifted from what people do to why: ‘build alliances; support and mentor; show our power’. There is a reduced focus on growing awareness of AYCC and an increased focus on shared identity of an ‘Active Crew’ who quickly mobilise and deliver different campaign tactics. Similarly, a concern for connecting with the general public has been replaced by the concept of Contributing members.

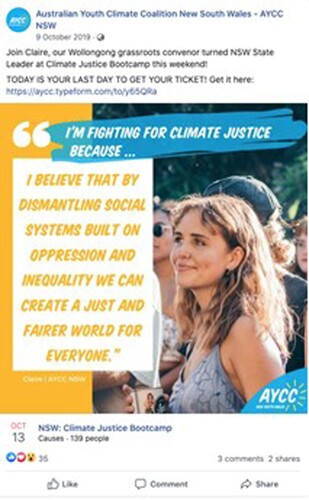

While in public communications AYCC encourages all forms of engagement, from loose, ad hoc or events-based, it also actively ‘narrates’ and valorises commitment and contribution to the ‘backbone’ of the movement, alongside the political values and vision of the organisation. demonstrates how Facebook posts showcase AYCC member progression through different layers of contribution alongside the political values and vision of the organisation (). This post announces that local organiser, ‘Claire’, has become a State Leader. Her quote highlights her own motivations (self) in a post that calls for other young people (us) to take part in a training bootcamp and join the effort to create change (now) to fight for ‘climate justice’.

The expanding ‘branch’ and membership structure, along with the values and aims of AYCC over time, reflect a concern to tackle inequality and intersectionality in order to achieve climate justice. In particular, Indigenous knowledge and leadership and the need to learn from and act in solidarity with First Nations people has become more central to the AYCC story.

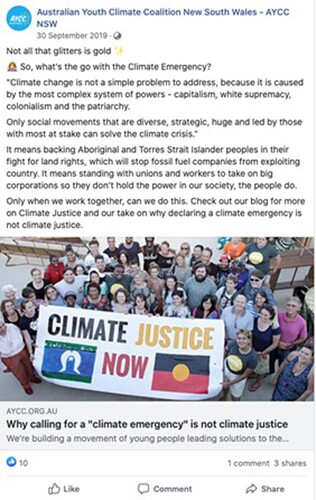

In 2014, AYCC launched the Seed Indigenous Youth Climate Network (‘Seed’). Seed has its own National Director, staff and volunteers who are Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander: ‘empowering Indigenous young people to lead climate justice campaigns and create change in their communities’ (AYCC Impact Report Citation2019, 3). Seed focuses on providing training to Indigenous young people through summits and camps, and reaching people through speeches, presentations and community engagement (AYCC Annual Report Citation2014, 14). In 2019 the Seed staff team consisted of seven Indigenous young people with a network of over 250 volunteers (AYCC Impact Report Citation2019, 13). As illustrated in below, AYCC communications have increasingly explained how racist, capitalist and sexist social structures are drivers of climate change which must be addressed in order to achieve climate justice.

AYCC publicly recognises the continuation of Indigenous knowledges and care for country, despite the sustained and systematic state violence experienced by First Nations people. Over time, the organisational form and ‘story’ of AYCC has evolved to reflect climate justice as racial, gender and economic justice. The strategic yet flexible, model of AYCC reflects participatory values and cultures, and a youthful politics of climate change as a ‘social’, rather than ‘environmental’ problem.

Youthful hybrid repertoires of action

Annual and Impact Reports, interviews and social media analysis reveal that AYCC and Seed incorporate a diverse range of participatory repertoires across a range of activities including centrally run campaigns, annual national and state conferences, training bootcamps and regional and national summits (AYCC Strategic Plan 2012–2015; Citation2019; AYCC website). Direct non-violent actions such as sit-ins and ‘people's parliaments’ have been held inside the foyer at Parliament House and other public places. AYCC uses the affordances of digital media to advocate for change, run campaigns and build the network. It also incorporates direct lobbying to members of parliament by AYCC executive and aligned organisations (AYCC Impact Report Citation2018, 14). In these activities AYCC communicates with diverse audiences simultaneously: members, the public, politicians and social media audiences. It is flexible, experimental and enables members to personalise actions, as well as organise collectively on climate issues of local, national and global concern. Repertoires for campaigning and advocacy include collective and individual actions, street and online events which often tactically disrupt the ordinary processes and protocols of advocacy and institutional policy processes. For example, AYCC has organised ‘road trips’ during which members travel as a group through towns and communities giving presentations to raise awareness of particular climate issues. They also run regular youth climate conferences and leadership training events. Their targeted political campaigns, such as ‘For the Love of the Reef’,Footnote4 ‘STOP ADANI’Footnote5 and ‘Repower our Schools’Footnote6 focus on raising awareness through distributed campaigning at a local level, fundraising, peaceful protest gatherings and accessible online information. The stories of these campaigns and actions are told through Impact reports () emphasising how youthful individual actions contribute to collective success and impact.

AYCC has also consistently targeted politicians. For instance, in 2014, the AYCC Safe Climate Roadmap campaign culminated in a three-day youth summit, visual protest action on the lawns of Parliament House in Canberra and a ‘Youth Senate Hearing’ during which 22 Federal SenatorsFootnote7 listened to the perspectives of young people from around the country (AYCC Annual Report Citation2014, 11). In the lead up to the federal election in 2019, AYCC targeted politicians and the public in an effort to have coal mines and climate change on the election agenda. In addition to meetings with politicians, AYCC members undertook door-knocking in key seats to encourage young people to enrol to vote and raise awareness of candidate positions on new coal mines, such as the proposed Adani mine in the Australian state of Queensland – emulating political parties campaigning for votes (Chadwick Citation2007).

AYCC has also embraced and pioneered creative and fun forms of climate action, such as flash mobsFootnote8 and TikTok: blending music, dance, humour and narrative to share information, communicate demands and connect with new audiences (AYCC Impact Report Citation2019). However, social media and stunts are not the only – or even most significant – tactic for delivering engaging information about climate change issues and solutions, promoting training and actions or generating conversations online where young people ‘are’ (Chadwick Citation2007; Vromen Citation2017). Over time, AYCC has developed a focus on engaging with young people, especially students, who do not already see themselves as climate activists, in the spaces where they live, learn and hang out. In particular, running activities in schools, and social and public events are tactics used by AYCC to create frontier situations.

Fostering political interest through educative approaches and friendship networks

School-based engagement has been a key focus for AYCC and schools have become more important to the AYCC story and strategy over time. shows how AYCC public reports demonstrate a growing trend of referring to schools, particularly in 2017 and 2018, the years leading up to the SS4C.

Table 2. Mention of ‘school’ and ‘schools’ in AYCC Annual and Impact Reports 2009–2019.

AYCC has actively engaged students in school settings through programmes such as ‘Switched on Schools’ which aim to give students ‘the skills, tools and networks to lead long term change [and] provides the opportunity for building long term power, and a grassroots organising model that creates a variety of volunteer pathways to ensure sustainability and strength of the movement’ (AYCC Citation2017, 8). In 2018 alone, 500 Australian schools took part (AYCC Impact Report Citation2018). AYCC also developed a website and database to better engage with students, track their campaigning progress and support them to fundraise. As such, by the time of the first SS4C in 2018, AYCC had been actively supporting students to learn about climate change and civic and political action through training, events and digital media for almost 10 years. AYCC claimed in 2018 that SS4C was the culmination of many years preparing for such an event:

The success of the strike was a reminder of the unique power that young people have to change the world. And it was a celebration of the thousands of conversations, hundreds of trainings and years of energy that the AYCC and many others have put in, sowing the seeds for an unprecedented grassroots moment like this. To all the students who led this, thank you from the bottom of our hearts, and know that our community has got your back. (AYCC Impact Report Citation2018, 18)

Our schools program truly is one of a kind. We work with thousands of high school students through in-school workshops, huge training summits, and transformational leadership programs – educating students about climate justice, and ensuring they have the skills, tools and confidence to organise for change on both a community and national level. (27)

… the transformational element of being part of AYCC is feeling empowered and being part of something bigger. This comes from working together with your peers and community, so we facilitate that through local groups, we facilitate that through national and state-based events, training camps, specific programs for schools, with Indigenous young people … (Bridget, 25 years, AYCC Core)

My friend set up the [AYCC] group … She was really encouraging me to join and it was my first year at uni and I wanted to meet new people. Climate change especially is interesting to me because I was involved in an environment group back in high school. I thought it’d be a good follow-on … I would first only really go to stuff that [my friend] was going to but then as I started to make more friends in the group I started going to other things. (Georgie, 21 years, female, AYCC ‘Crowd’)

In September 2020, immediately prior to an Australian SS4C action, AYCC's Queensland Central Impact Team organised an Action Night for Regional and Remote volunteers in Queensland who were connected virtually via zoom (AYCC Citation2020). This evening aimed to target local Members of Parliament and the then Liberal Opposition Leader in the state of Queensland, Deb Frecklington ahead of the upcoming Queensland state government election. Tactics for the night included writing personal letters to incumbents and opposing candidates and sending them on September 25; calling and leaving voice messages on MP office phones and targeting MPs social media accounts. These actions were accompanied by fun activities, including dance parties, rounds of Scribblio (a multiplayer drawing and guessing game) and an in-house competition for who could do the most actions. Such instances show how AYCC creates openings, or ‘frontier situations’ (Bakardjieva Citation2009) by leveraging everyday interests and activities for climate activism. In developing this frontier situation (online) and encouraging young people to engage in individualised collective networked action, AYCC combined engagement in peer-based activities with activist tactics and direct action, enhancing participation and building engagement with the organisation. The timing of this event enabled AYCC to tap into the excitement and energy of the SS4C ‘trigger event’ planned for the following day and use it to encourage members’ involvement in SS4C rallies and inform them about the forthcoming state election.

Discussion

The structure, participatory repertoires and use of storytelling indicate that AYCC is a ‘hybrid online campaigning organisation’ (Vromen Citation2017). It acts as a social movement, advocacy organisation and sometimes deploys the tactics of lobby groups and political parties, all the while using storytelling to build a youth movement for climate change. Our analysis shows that for AYCC members and official communications, ‘youthfulness’ is not just a fact but is a core part of the AYCC story: ‘youth’ is discursively and practically framed as a strength of the organisation, the climate justice movement and is central to achieving climate justice. Through storytelling AYCC frames the role of young people, and of campaign issues, in ways that inform young people generally, and with which their members can connect and that are easily communicated through diverse media channels. Moreover, campaigns and organising activities leverage peer-to-peer strategies tap into friendship networks to connect with personal motivations and broader interests, a sense of shared purpose and immediate need for action that results in real outcomes and impact driven by young people. As a hybrid organisation, AYCC deploys storytelling as a central form of political action (Vromen Citation2017), that is deployed in frontier situations (schools, social media, local community and friendship groups) and which leverage trigger events such as elections and the SS4C.

To this, we add that AYCC also acts like a training and capacity-building organisation through its increasing focus on delivery of bootcamps, summits and school programmes over 15 years. Hall and Ebrary, Inc. (Citation2012) note that learning in and from social movements has a rich history and remains an important aspect of social change praxis. The focus of AYCC on informing through its communications and actions, as well as delivering programmes with and in traditional education settings such as schools, suggests that a key strategy of youth-led organisations is peer-based education. Moreover, this ‘educative’ approach is woven through the structure, communication and action repertoires, the sites and tactics for informing and raising awareness and fostering individual and collective identity. AYCC explicitly calls itself a ‘movement-building’ organisation – to which we would add ‘educative’. Through ‘educative movement-building’, AYCC has performed an important role in fostering political interest and civic skills at the sub-activist level among young people in Australia for 15 years. In doing so, AYCC has challenged the way institutional political organisations alienate young people and contributed to the emergence of individual and collective youthful political identities at a critical time in history and in the lead up to the recent global climate strikes in which students have been so central.

AYCC reflects a youth-led alternative to the existing political structures and organisations that young people feel are failing at the job. Our analysis of the way AYCC frames the issue of climate justice, the role of young people and the kind of democratic processes required to address the problem of climate justice – as social, economic, First Nations and planetary justice – also suggests that AYCC, is not merely a manifestation of ‘oppositional’ or ‘networked’ governance values and norms (Collin Citation2015). Rather, the ‘hybrid, online campaigning’ (Vromen Citation2017) and ‘educative movement-building’ of AYCC is underpinned by a ‘DIO’ politics (Pickard Citation2019) based on values such as inclusivity, fun and care. The case study of AYCC suggests that youth-led activist organisations have a unique form and reflect a youthful politics of climate justice that moves beyond ‘issues-based politics’. This warrants more research on the significance of these organisations for environmental activism, for youth political subjectivies and for theorising the political through the actions and perspectives of young people (Watts Citation2021) – and the organisations they create.

Conclusion

In her recent book, Making-Up People: Youth, Truth and Politics, Bessant notes that, in contrast with declining trust and satisfaction with democracies around the world, since 2008 youth activism has been on the increase, culminating in the third Global Climate Strike in September 2019 – ‘the largest climate protest ever staged’ (Bessant Citation2021, 212). Our case study of the AYCC suggests that the mass mobilisation of young people in Australia should not be seen as either sudden or surprising. To answer our first research question, we find that, over 15 years, AYCC has played a significant role in creating the conditions for youth climate justice activism by cultivating young peoples’ political interests, actions and organising. While utilising a diverse range of repertoires including campaigns, events and stunts, AYCC's increased delivery of school-based programmes has significantly contributed to establishing a broad base of young people with interest in and capacities to organise and act for climate justice. Thus, we argue that contemporary youth-led organisations are not only hybrid online campaigning organisations (Vromen Citation2017), but are ‘educative movement-building organisations’. Moreover, they leverage the importance of everyday interactions – such as friendships – in the places where young people live their lives – such as schools and online. International comparative study of countries would illuminate whether other youth climate coalitions (e.g. in U.K., Canada and India) are also ‘educative movement-building organisations’. More empirical and theoretical work would assist in determining how this form of youthful hybrid organisation is significant for environmental activism and contemporary democracies in specific national contexts and globally.

In response to our second research question on the relationship between AYCC and evolving political subjectivities, as well as fostering political interest, we find that AYCC has been significant in fostering a youthful politics of climate justice. Researchers have observed the increasing complexity and growing range of issues young people are concerned with when participating in climate-related actions (Pickard Citation2019; Bowman Citation2020; Sloam Citation2020). These young people are ‘being politically socialised at a specific time in history’ and ‘during a time of successive and overlapping crises’ (Pickard, Bowman, and Arya Citation2020, 255) as well as holding – or becoming more aware of – non-western/colonial knowledges and viewpoints (Hayward Citation2021; Ritchie Citation2020; Collin and Matthews Citation2021). Based on our analysis of AYCC, we also suggest that through educative movement building youth-led organisations are directly implicated in these processes. They are shaping a new politics of climate justice; not merely reflecting shifts in political norms, values and actions but enacting them. This is most evident in the way AYCC frames climate justice and young people as legitimate political actors, in the framing of climate justice as a question of broader social justice, and in the tactics to foster political interest in everyday settings and relationships that constitute young lives. While some hold concerns that the ‘spectacle’ of youth could undermine the movement in the longer term (Buettner Citation2020), we argue that, at least in the context of Australia, the educative movement-building of AYCC and associated autonomous organisations such as SS4C means that the youth climate justice movement will likely not only endure, but grow.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the dedicated young environmental activists and the leaders of AYCC who contributed to the content and interviews this research is based on.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Author estimates based on numbers reported by School Strike for Climate of people participating in rallies and online events between October 2018 and December 2020.

3 Ethics approval was received from the Western Sydney University H10304 and H10708. Interviewees were given pseudonyms and all identifying information has been removed.

4 To protect the Australian Great Barrier Reef which is endangered due to increasing sea temperatures and pollution from the proposed Adani coal mine.

5 Campaign to prevent the funding, approval and construction of the proposed Adani coal mine in north Queensland.

6 Schools program, training students on how to take action on climate change – starting in their own school communities.

7 This represents approximately one-third of the Australian Senate.

8 Flash mobs are a tactic of political activists where individuals are contacted through online platforms to gather at a specific location to raise awareness on an issue. Flash mobs first emerged in major cities in 2003 as individual groups responded to emails to appear at specific sites.

References

- Amnå, E., and J. Ekman. 2014. “Standby Citizens: Diverse Faces of Political Passivity.” European Political Science Review 6 (2): 261–281. doi:10.1017/S175577391300009X.

- Andretta, M., and D. della Porta. 2020. “When Millennials Protest. Youth Activism in Italy.” In Italian Youth in International Context. Belonging, Constraints and Opportunities, edited by Valentina Cuzzocrea, Barbara Giovanna Bello, and Yuri Kazepov, 41–57. Oxon: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781351039949.

- AYCC (Australian Youth Climate Coalition). 2009. Annual Report. Melbourne: AYCC.

- AYCC (Australian Youth Climate Coalition). 2014. Annual Report. Melbourne: AYCC.

- AYCC (Australian Youth Climate Coalition). 2017. Annual Report. Melbourne: AYCC.

- AYCC (Australian Youth Climate Coalition). 2018. Annual Report. Melbourne: AYCC.

- AYCC (Australian Youth Climate Coalition). 2019. Annual Report. Melbourne: AYCC.

- AYCC (Australian Youth Climate Coalition). 2020. Queensland Central Impact Team Launch. AYCC Queensland Central Impact Team Launch. https://www.aycc.org.au/qld_central_impact_team_launch.

- AYCC (Australian Youth Climate Coalition). 2021. About the AYCC. https://www.aycc.org.au/about.

- Bakardjieva, M. 2009. “Subactivism: Lifeworld and Politics in the Age of the Internet.” The Information Society 25 (2): 91–104. doi:10.1080/01972240802701627.

- Bang, H. 2005. “Among Everyday Makers and Expert Citizens.” In Remaking Governance: Peoples, Politics and the Public Sphere, edited by Janet Newman, 159–178. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Beck, U. 1997. The Reinvention of Politics: Rethinking Modernity in the Global Social Order. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bennett, L. 2003. “Communicating Global Activism.” Information, Communication & Society 6 (2): 143–168. doi:10.1080/1369118032000093860a.

- Bennett, L. 2008. “Changing Citizenship in the Digital Age.” In Civic Life Online: Learning How Digital Media Can Engage Youth, edited by Lance Bennett, 1–24. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Bennett, L., and A. Segerberg. 2012. “The Logic of Connective Action: Digital Media and the Personalization of Contentious Politics.” Information, Communication & Society 15 (5): 739–768.

- Bessant, J. 2021. Making-Up People: Youth, Truth and Politics. New York: Routledge.

- Bessant, J., R. Farthing, and R. Watts. 2017. The Precarious Generation: A Political Economy of Young People. London: Routledge.

- Bimber, B., A. Flanagan, and C. Stohl. 2012. Collective Action in Organizations: Interaction and Engagement in an Era of Technological Change. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511978777

- Bowman, B. 2019. “Imagining Future Worlds Alongside Young Climate Activists: A new Framework for Research.” Fennia 197 (2): 295–305. doi:10.11143/fennia.85151.

- Bowman, B. 2020. “‘They Don’t Quite Understand the Importance of What We’re Doing Today’: The Young People’s Climate Strikes as Subaltern Activism.” Sustain Earth 3 (16). doi:10.1186/s42055-020-00038-x.

- Buettner, A. 2020. “‘Imagine What We Could do’— The School Strikes for Climate and Reclaiming Citizen Empowerment.” Continuum 34 (6): 828–839. doi:10.1080/10304312.2020.1842123.

- Chadwick, A. 2007. “Digital Network Repertoires and Organizational Hybridity.” Political Communication 24 (3): 283–301. doi:10.1080/10584600701471666.

- Collin, P. 2008. “The Internet, Youth Participation Policies, and the Development of Young People’s Political Identities in Australia.” Journal of Youth Studies 11 (5): 527–542. doi:10.1080/13676260802282992.

- Collin, P. 2015. Young Citizens and Political Participation in a Digital Society. Addressing the Democratic Disconnect. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Collin, P., and I. Matthews. 2021. “School Strike For Climate: Australian Students Renegotiating Citizenship.” In When Students Protest. Secondary and High Schools, 125–144. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Dalton, R. J. 2017. The Participation Gap: Social Status and Political Inequality. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- de Moor, J., M. De Vydt, K. Uba, and M. Wahlström. 2020. “New Kids on the Block: Taking Stock of the Recent Cycle of Climate Activism.” Social Movement Studies. doi:10.1080/14742837.2020.1836617.

- della Porta, D. 2015. Social Movements in Times of Austerity: Bringing Capitalism Back Into Protest Analysis. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Denscombe, M. 2003. The Good Research Guide for Small-Scale Research Projects. Maidenhead: OUP.

- Dunleavy, P. 1996. “Political Behaviour: Institutional and Experiential Approaches.” In A New Handbook of Political Science, edited by R. Goodin and H. Klingemann, 276–293. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Earl, J., T. V. Maher, and T. Elliott. 2017. “Youth, Activism, and Social Movements.” Sociology Compass 11: e12465. doi:10.1111/soc4.12465.

- Flanagan, C. A. 2013. Teenage Citizens: The Political Theories of the Young. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Gordon, H. R., and J. K. Taft. 2011. “Rethinking Youth Political Socialization: Teenage Activists Talk Back.” Youth & Society 43 (4): 1499–1527.

- Hall, Budd L., and Ebrary, Inc. 2012. Learning and Education for a Better World the Role of Social Movements. Rotterdam: SensePublishers. International Issues in Adult Education; V.10. Web.

- Harris, A. 2003. “gURL Scenes and Grrrl Zines: The Regulation and Resistance of Girls in Late Modernity.” Feminist Review 72 (1): 38–56.

- Harris, A., J. Wyn, and S. Younes. 2010. “Beyond Apathetic or Activist Youth ‘Ordinary’ Young People and Contemporary Forms of Participation.” Young 18 (1): 9–32.

- Hayward, B. 2021. Children, Citizenship and Environment #SchoolStrike Edition. 2nd ed. London: Routledge.

- Henn, M., A. Nunes, and J. Sloam. 2021. “Young Cosmopolitans and Environmental Politics: How Postmaterialist Values Inform and Shape Youth Engagement in Environmental Politics.” Journal of Youth Studies, DOI: 10.1080/13676261.2021.1994131.

- Hilder, C. E. 2018. “Australian Youth-Led Activist Organisations and the Everyday Shaping of Political Subjectivities in the Digital Age.” PhD Thesis. Western Sydney University.

- Karpf, D. 2012. The MoveOn Effect: The Unexpected Transformation of American Political Advocacy. New York: OUP.

- Loader, B. D., A. Vromen, and M. A. Xenos. 2014. “The Networked Young Citizen: Social Media, Political Participation and Civic Engagement.” Information, Communication & Society 17 (2): 143–150. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2013.871571.

- Marsh, D., T. O’Toole, and S. Jones. 2007. Young People and Politics in the United Kingdom: Apathy or Alienation? Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Munson, Z. 2010. “Mobilizing on Campus: Conservative Movements and Today's College Students.” Sociological Forum 25 (4): 769–786.

- Murphy, K. 2015. “‘In the Backblocks of Capitalism’: Australian Student Activism in the Global 1960s.” Australian Historical Studies 46 (2): 252–268. doi:10.1080/1031461X.2015.1039554.

- Nairn, K. 2019. “Learning from Young People Engaged in Climate Activism: The Potential of Collectivizing Despair and Hope.” Young 27 (5): 435–450. doi:10.1177/1103308818817603.

- Nissen, S., J. H. Wong, and S. Carlton. 2020. “Children and Young People’s Climate Crisis Activism – A Perspective on Long-Term Effects.” Children’s Geographies, doi:10.1080/14733285.2020.1812535.

- Norris, P. 2002. Democratic Phoenix: Reinventing Political Activism . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Partridge, E. 2008. “From Ambivalence to Activism Young People’s Environmental Views and Actions.” Youth Studies Australia 27 (2): 18–25. https://research.fit.edu/media/site-specific/researchfitedu/coast-climate-adaptation-library/climate-communications/youth-climate-amp-social-media/Partridge.-2008.-Youth-Environmental-Views–Actions.pdf.

- Pickard, S. 2019. Politics, Protest and Young People Political Participation and Dissent in 21st Century Britain. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Pickard, S., and J. Bessant, eds. 2017. Young People Re-Generating Politics in Times of Crises. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pickard, S., and J. Bessant. 2018. “France’s # Nuit Debout Social Movement: Young People Rising Up and Moral Emotions.” Societies 8 (4): 100. doi:10.3390/soc8040100.

- Pickard, S., B. Bowman, and D. Arya. 2020. ““We Are Radical In Our Kindness”: The Political Socialisation, Motivations, Demands and Protest Actions of Young Environmental Activists in Britain.” Youth and Globalization 2 (2): 251–280. doi:10.1163/25895745-02020007.

- Ritchie, J. 2020. “Movement from the Margins to Global Recognition: Climate Change Activism by Young People and in Particular Indigenous Youth.” International Studies in Sociology of Education 30 (1-2): 53–72. doi:10.1080/09620214.2020.1854830.

- Sander, T. H., and R. D. Putnam. 2010. “Democracy’s Past and Future: Still Bowling Alone? The Post-9/11 Split.” Journal of Democracy 21 (1): 9–16.

- Sloam, J. 2020. “Young Londoners, Sustainability and Everyday Politics: The Framing of Environmental Issues in a Global City.” Sustainable Earth 3 (14): 2–7. doi:10.1186/s42055-020-00036-z.

- Sloam, J., and M. Henn. 2019. Youthquake 2017: The Rise of Young Cosmopolitans in Britain. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Vromen, A. 2003. “‘People Try to Put us Down.’ Participatory Citizenship of ‘Generation X’.” Australian Journal of Political Science 38 (1): 79–99.

- Vromen, A. 2011. “Constructing Australian Youth Online Empowered but Dutiful Citizens?.” Information, Communication and Society 14 (7): 959–980. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2010.549236

- Vromen, A. 2017. Digital Citizenship and Political Engagement: The Challenge from Online Campaigning and Advocacy Organisations. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wahlström, M., P. Kocyba, M. De Vydt, and J. de Moor. 2019. Protest for a Future: Composition, Mobilization and Motives of the Participants in Fridays for Future Climate Protests on 15 March, 2019 in 13 European cities. https://eprints.keele.ac.uk/6571/7/20190709_Protest%20for%20a%20future_GCS%20Descriptive%20Report.pdf.

- Warren, R. 1995. The Purpose Driven Church. Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

- Watson, I. 2017. “Aboriginal Relationships to the Natural World: Colonial ‘Protection’ of Human Rights and the Environment.” Journal of Human Rights and the Environment 9 (2): September 2018, 119–140.

- Watts, R. 2021. “Theorizing Student Protest.” In When Students Protest. (Vol 1): Secondary and High School Students, edited by J. Bessant, A. Mejia Mesinas, and S. Pickard, 13–24. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield.